Dr. Robert and Laura Vukovich

/Article by Bill Heller

Going to the track with your father is a powerful experience for a little boy—a treasured memory. “I grew up on the Jersey shore, and my dad used to take me out to Monmouth Park,” Dr. Robert Vukovich of WellSpring Stables said. “I was probably nine or 10. He taught me how to read the Racing Form, and sometimes he would place a bet for me. I’ve always loved horses and horse people. I decided if I ever had the chance, I would try to get involved somehow.”

Seven decades later, he is involved up to his gills and wouldn’t want it any other way. The fact that he can share it with his wife Laura makes it even more special. “She’s been there every step of the way,” he said.

Why did he wait until the 1990s to get involved in Thoroughbred racing? “College and my pharmaceutical career got in the way,” he joked. “I started in pharmaceutical research.”

He eventually developed his own company, Robert’s Pharmaceutical, and sold it to a large United Kingdom company in the late 1990s. That allowed him to return to horses.

Asked if he ever misses his pharmaceutical career, Robert said, “No. I don’t miss all the pressures. I don’t miss all the deadlines and the regulatory commissions.”

That didn’t prevent him from being successful in his industry. “He came from nothing and has worked very hard,” Laura, a native of Brooklyn with no prior history with horses, said. “We both did. He’s just a warm, caring person even to his horses. He says, `You only go around once—no rehearsal.’”

He’s never been happier than he is now with horses. “I wake up in the morning, and I think of horses,” he said. “I talk to people all day about horses, and sometimes I even dream about them—horses like Leave No Trace. Could this be really happening? Did we win the Spinaway?” They did.

In 1999, the Vokoviches bought a horse farm in Colts Neck, New Jersey, where they now also live. “We started with 100 acres and added pieces,” Robert said. “We currently have 168 acres. Laura names most of our horses.”

She named their two-year-old filly star Leave No Trace after a movie she watched some time ago. “I didn’t see the whole movie,” she said. “It was about a father and a daughter and some tragedy.”

Their horse operation has been the complete opposite. They began breeding horses and then started buying them at auctions and racing them. “Over time, I got to appreciate that I could do better than breeding by carefully selecting horses at auctions,” Robert said. “We now buy most of our bloodstock.”

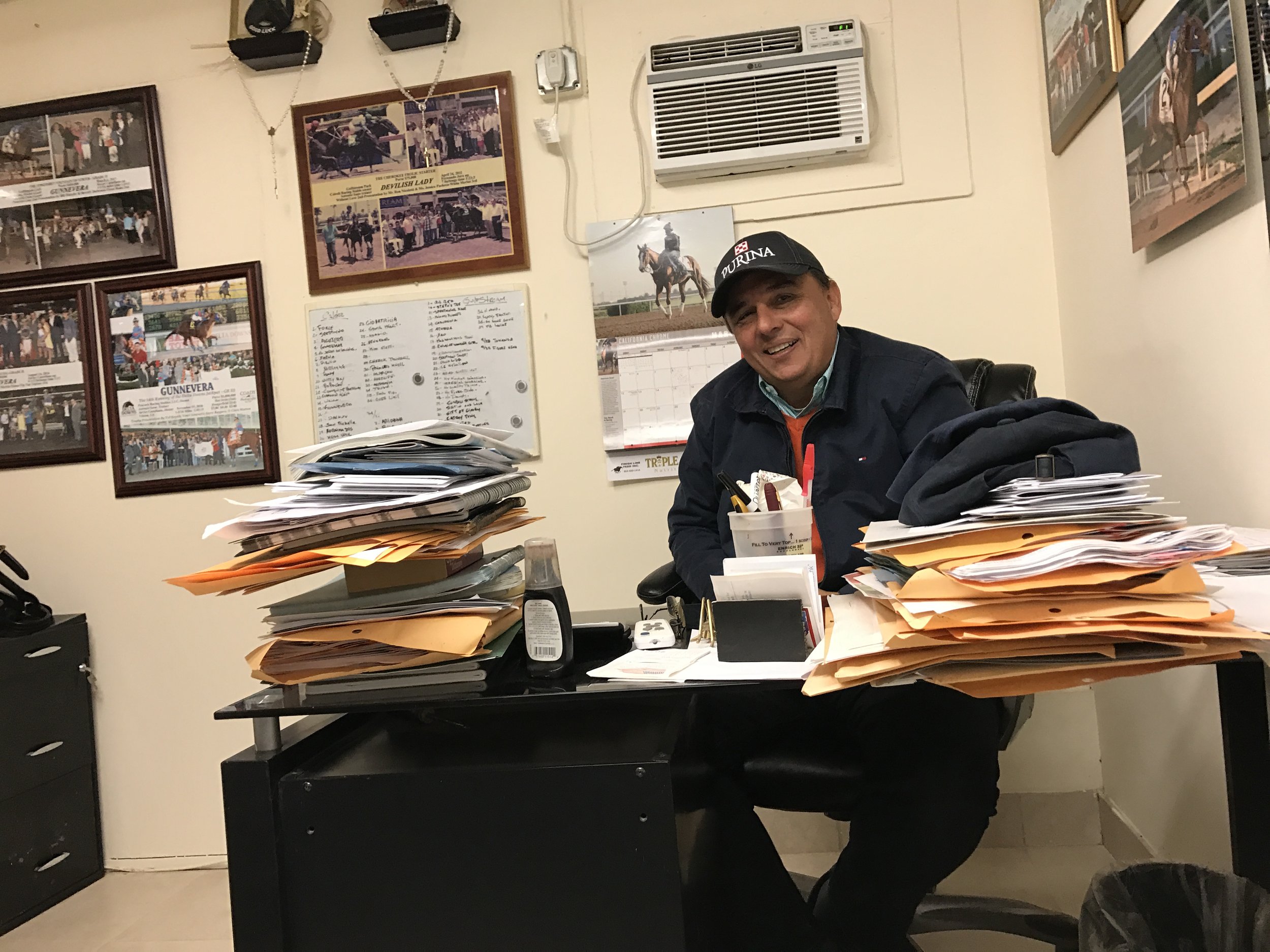

His initial success came with the help of late trainer Dominick Galluscio, who saddled Organizer and Dr. Vee’s Magic to consecutive victories in the rich Empire Classic for New York-breds in 2006 and 2007. “He was a great trainer and a friend,” Robert said.

Now he uses Phil Serpe and Jim Ryerson as his trainers. “After Dominick passed, I asked Jim Ryerson if he’d take a few horses,” Robert said. “He did. I asked him who would be useful to me as a trainer who races in New York and Florida, and he nominated Phil Serpe. Phil and I have been doing business for seven years. We train our horses in the winter down in Florida and bring them up in the springtime and decide whether to send them to Jim or Phil.”

Robert and Laura now have 15 horses in training, including eight yearlings and five weanlings. They have never done better than the last two years. In 2021, Safe Conduct won the Queen’s Plate. Unfortunately, Peter and Laura weren’t there at Woodbine. “We couldn’t get up there to watch in because of Covid,” Robert said. “We had a bunch of people here. When he crossed the finish line, I was stunned. I couldn’t believe it. It was remarkable.” More recently he finished second in the Gr. 3 Monmouth Stakes. “He’s still a special horse,” Robert said.

So is Leave No Trace, who followed a 2 ¼ length debut in a restricted maiden debut at Saratoga by capturing the Gr. 1 Spinaway there at 14-1. Serpe trains both Safe Conduct and Leave No Trace. Robert and Laura purchased Safe Conduct for $45,000 as a yearling at the Keeneland November Sale and Leave No Trace for $40,000 as a yearling at the Fasig-Tipton Mid-Atlantic Fall Sale. Combined, they have earned more than $900,000 with a lot of racing still ahead of them.

But, again, Robert and Laura weren’t at the track when Leave No Trace won the Spinaway. “We were in Switzerland when she won the Spinaway,” Laura said. “We watched it on the telephone. It was around midnight. My husband went bananas. We were very proud. Now Phil is asking us not to be there in her future races. He said he’d buy us cruise tickets.”

Regardless, Robert and Laura are embracing the ride. “To see a little baby grow up and become a rockstar in horse racing, it’s very fulfilling.” Robert said.

Actually, they enjoy every horse they have, regardless of their performances. “Horses are very honest,” Robert said. “They’re the best employees you can have. They just give you all they have, and they never question it. Mother Nature created these animals so beautiful, so powerful and, for most cases, very gentle around you. You sit and watch them in awe. They always give you their best. They give you everything they’ve got. You can’t ask for more. I’m going to be 80. The horses keep me young.”