Alan Balch - Remembering where we come from

Victor Espinoza photo

Like so many of us in racing, I’ve been horse crazy my entire life.

Some of my earliest memories are being on my dad’s shoulders, going through the livestock barns at the San Diego County Fair, and then lighting up when we got to the horse show . . . which, back then, was located just outside the turn at Del Mar into the backstretch, at the old 6-furlong start, long before the chute was extended to 7/8. All their horse barns back then were the original adobe, open to the public during the fair, and we could walk down the shed rows talking to the horses, petting those noses and loving the stable smells.

At least I did. My mom was appalled, of course.

She assumed, I’m certain, that I would grow out of my weird fixation. But the way those things go at certain ages, the more I was discouraged, the more obsessed I became. The fact that our family was decidedly not elite in any respect, certainly not educationally or financially, became a great opportunity for me to work at what I loved the most: taking care of the horses, to begin with, and camping at the barn whenever possible. At first, I wasn’t getting paid at all—except in getting to learn to ride by watching and listening and then riding my favorite horses without having to rent them. Lessons were out of the question.

I gradually learned that the people who owned and showed and raced horses had to have the money to do it, and being able to do that myself was beyond my imagination. I don’t remember ever caring. Nor do I remember ever being mistreated because of my lowly station. In fact, it was a great bonus for me to get out of school at times to travel to shows and live in a tack room in the stables. And, as I grew older, to start getting paid actual wages for my work.

Making it through college and graduate school without having to wash dishes in the dining hall led to my loving equestrian sport in a different way and at a much different level—especially when I met Robert Strub at the Forum International Horse Show in Los Angeles (which I was managing while attending school). He offered me a position at Santa Anita.

Elite equestrian sport, racing and non-racing alike, became the rest of my distinctly non-elite life. And, I venture to say, my fellow non-elites in these sports vastly outnumber the elites.

Almost all trainers, jockeys and racing labor on the backstretch, who make the game go from hour to hour, day to day, month to month, and year to year, weren’t elite when they started out, at least by any definition except the one that counts: their merit, their specialized skills, and their commitment to horses and the sport. I remember how moved I was a decade ago when one of international racing’s most elite trainers got choked up when describing how it felt to be appointed a director of an esteemed racing association. “I’m just a trainer,” he said, as though his accomplishments and expertise didn’t qualify him to rub shoulders and contribute to deliberations alongside wealthy and powerful elite decision-makers. They did. And they do.

In this greatest of all sports . . . where the interdependence of all its critical components is its essence . . . elites of accomplishment and merit, like him, comfortably perform alongside all the other elites, including those of birth, inherited or self-made wealth and royalty.

Horses have brought us all together, and many of us have been lucky enough to know—and be appreciated by—some of the world’s most famous personages.

So it was when Victor Espinoza, the self-proclaimed “luckiest Mexican on Earth,” won the Triple Crown, and later had occasion to meet and joke with Queen Elizabeth II at Royal Ascot. Doesn’t his story sum it up? And remind most of us where we came from?

The eleventh of twelve children, born on a dairy farm in Tulancingo, Hidalgo, growing up to work in a manufacturing plant and the stables, Victor drove a bus to pay for jockey school. Anyone who has endured Mexico City traffic knows the elite skills that must have been required! He aspired to more; his skill and determination resulted in successes reserved for the very fewest of the world’s top athletes. As the famed Dr. Robert Kerlan – who treated athletes at the highest levels of every major sport – once observed, “pound for pound, jockeys are the greatest.”

When honored by the Edwin J. Gregson Foundation, which has raised over $6 million from the racing community in 20 years—of which 98% is dedicated to backstretch programs including scholarships for its children—Victor again cited his luck in achieving what he has without much school, as well as his amazement at the Gregson’s success in its scholarship program. Hundreds of backstretch community children have gone to college because of it—in fields ranging from mechanical engineering to biology, nursing, graphic design, criminal justice, life sciences, sociology and everything else.

A few are now even among the world’s elites in architecture and medicine. The backstretch teaches tenacity.

And isn’t that just one reason why her late Majesty the Queen loved horses, racing, and its community, above all her other pursuits?

John Sadler - Trainer of superstar racehorse Flightline

Article by Annie Lambert

Trainer John Sadler has aimed at a career in the equine industry since he was a small child. His resolve landed him exactly where he needed to be.

Who knew that a little boy’s encounter with horses in a field adjacent to a family’s summer vacation home would set a course toward a lifelong career with horses? That young boy was California-based trainer John Sadler.

It was Sadler’s connection to horses that kept him on course to become a successful horseman. “I always wanted to work with horses,” he recalled.

The trainer’s equine experiences evolved from simple riding lessons to appease his mother, to showing hunters and jumpers and then, on to a natural progression within the Thoroughbred racing industry. Each chapter of Sadler’s equine journey has been fruitful.

He was an outstanding rider in the show ring and now sits among the best trainers in the racing industry. As of October 11, 2022, Sadler has amassed earnings of $141,058,895. Horses like Accelerate, Stellar Wind, Switch, Higher Power and current superstar Flightline have greatly enhanced his coffers.

While Sadler seems a humble guy, his accumulating milestones are worth boasting about. The kid attracted to horses at first glance is definitely making the most of his passion.

Lessons Learned

John Sadler - jumping - mr cove

Sadler was born in Long Beach, California, but was raised in nearby Pasadena. His family was summering at a house near the beach in Palos Verdes when his equine passion bloomed.

“We spent one summer at the beach, and some people had horses in their backyard,” Sadler recalled. ”I told my mother I’d like to ride the horses, but she told me I had to take lessons if I wanted to ride. So, when I was very young, I took riding lessons in Palos Verdes.”

When summer ended, the new equestrian wanted to keep up with his lessons and found himself riding at Flintridge Riding Club in La Canada, in the shadow of the Rose Bowl, all through high school. Riding with Jimmy A. Williams, a renowned horseman, helped Sadler excel at riding show horses.

Dianne Grod, a respected trainer and rider of Gran Prix jumpers now retired and living in Ocala, Florida, remembered Sadler’s ability. “He rode hunters well, he rode the jumpers well and he equitated well,” Grod said. “And back then, everybody did all three divisions on the same horse.”

During his high school years, Sadler competed for a position on the United States Equestrian Team during their West coast screening trials held at Foxfield Riding School at Lake Sherwood, outside of Los Angeles.

During Sadler’s show jumping era, his parents became involved in Thoroughbred racing on a small scale.

“My parents had a fractional interest in a couple of racehorses with a group from Pasadena and San Marino,” Sadler explained. “Impossible Stables, Inc., was a fun group of people who were social friends. I would go out to the track with my parents and watch the horses run, so I got involved with the track early.”

Sadler admits the years have somewhat run together, making exact dates hard to recall, but during a couple of high school summers he found himself walking hots at Del Mar.

His racetrack career had begun.

Racetrack Basics

With his family spending a couple summers near Oceanside, Sadler headed to the track and a job walking hots for now retired trainer Tom Pratt, (Chiapas, Mexico). Pratt was a stepping stone on Sadler’s career path.

“He was a good and talented employee,” Pratt offered. That was high praise for a teenaged hotwalker learning the ropes.

Once he graduated high school, Sadler headed to the University of Oregon in Eugene. The Liberal Arts/English major self-admittedly that he “was not really a focused student.” He did, however, confess to taking half of the fraternity house to Portland Meadows racetrack one day, which was “a good trip.”

It was not hard to believe that the young horseman made a beeline back to the track following college. His learning was more focused around the horses, and he began studying the industry from within.

Sadler went to work as an assistant to veterinarian Dr. Jack Robbins during the 1970s. Robbins, who passed away in 2014, remains an iconic figure in the history of racing.

“I was his assistant for a couple of years,” Sadler said. “I always credit him a lot; I learned a lot from him. He was a great guy…a successful owner, a very successful veterinarian and he was one of the founders of the Oak Tree Racing Association. Not only did he have the veterinary knowledge, he had a good overview of the whole game.”

Sadler did not give serious consideration to becoming a veterinarian, but he did learn a lot from Robbins and the doctor’s top tier clientele.

“It was just fun to go into all these barns, every single day,” Sadler reminisced. “You’re talking about names like Noble Threewitt, Lester Holt, Joe Manzi, Ron McAnally, Gary Jones, Warren Stute, John Sullivan, Buster Millerick…I mean, all the guys that were kind of the backbone of California. I always tried to take something from all of them—all of those great trainers.”

The Conditioner

After working for Robbins, Sadler went to work for David Hofmans as an assistant trainer for a year or more. “There is no nicer person than Dave,” Sadler recalled. The boss also appreciated his assistant.

“He was great—a real help to me,” Hofmans said of Sadler. “Working with Jack Robbins gave him an overall picture of what was going on [with veterinary issues]. Dr. Robbins worked for many people, so John got to learn and understand medications and stuff. John was a very smart guy, very astute, and he paid attention to detail. He was great, and I was sad to see him leave.”

In about 1978, Sadler had the opportunity to oversee the late Eddie Gregson’s Northern California string—his first job training on his own.

“Eddie had a lot of horses at that time and was looking to have a trainer up north,” Sadler explained. “He proposed the idea of me going up there on his behest; I trained up there for a year or a year and a half.”

Tom Pratt decided to retire about that time and kindly offered Sadler an option of taking over a few of his horses.

“Pratt said he had four or five horses that I could train,” Sadler said. “I came back to Southern California and of the 30 horses I had up north, about four or five were good enough to come down here, so that’s how I got started here. These guys were all so good to me.”

Pratt’s trust in Sadler was evident.

“When I quit training, I turned over most of my clients to him,” he recalled. “I also bought a few horses with partners and gave him those to train. I had confidence in him and was happy to give him a big leg up to what has become a very successful career.”

Keeping Course

His first year as a licensed trainer Sadler ran Gregson’s horses as well as a few starters of his own. His 1978 Equibase records showed four starters with one running third and earnings of $2,700. But, that was just the beginning. He currently has 2713 wins, and counting.

Sadler’s first winner was Top Taker (Top Conference). His record has grown exponentially over the past 44 years as a trainer. As he put it: “As the years progressed, I got better stock, obviously. It’s been kind of a natural progression.”

That progression included a slew of graded stakes winners. Accelerate (Lookin At Lucky)—the top earner to date with $6,692,480—was the Eclipse Award 2018 Champion Older Dirt Male. His accolades include winning five Gr. 1 races and the 2018 Breeders’ Cup Classic. The stallion now stands at Lane’s End Farm in Kentucky. Sadler has several of his first crop two-year-olds in training.

“I’ve got four or five nice ones,” he revealed. “One ran third the other day; they are good looking prospects.”

Stellar Wind (Curlin) was a star for Sadler—being his second highest earner to date with $2,903,200. Owner Hronis Racing sold her through the 2017 Keeneland November Mixed Sale for $6 million, going to M.V. Magnier/Coolmore. Trainer Chad Brown ran her in the Pegasus World Cup Invitational Stakes (G1) the following January. The mare finished out of the money after a bobbled start in her final race.

Switch (Quiet American) earned $1,479,562 for owner CRK Stable. She was twice second and once third in the Breeders’ Cup Filly & Mare Sprint between 2010 and 2012. She was sold at the 2012 Fasig-Tipton Kentucky Fall Mixed sale for $4.3 million to Moyglare Stud Farm.

“She almost beat Zenyatta one day at Hollywood Park,” Sadler recalled. “She lost narrowly, by a head or something. One of the times she ran second at the Breeders' Cup, she was beaten by Musical Romance, who was ridden by my assistant trainer, Juan Leyva.”

Higher Power (Medaglia D’Oro) added $1,594,648 to the Hronis Racing coffers. He won five of his 20 lifetime starts, including the 2019 Pacific Classic (G1) as well as running third in the 2019 Breeders’ Cup Classic. The bay now stands at Darby Dan Farm in Kentucky.

Sadler currently has Flightline (Tapit), arguably the best dirt horse in the world, and ranked globally a close second to champion British turf star Baaeed (Sea The Stars (IRE). Flightline is (at the time of writing) five-for-five and a likely starter in the Breeders’ Cup Classic. The colt, owned by Hronis Racing, Siena Farm, Summer Wind Equine, West Point Thoroughbreds and Woodford Racing was a $1 million yearling purchase. And, he was more than worth the price.

Flightline has proven his prowess with amazing ease so far; competitors are not able to touch him. With Flavien Prat, his only jockey to date, the four-year-old won his first three starts, last year, by a total of 37 lengths.

In June this year, he won his fourth start in the Metropolitan Mile at Belmont by six lengths. His most mind-boggling win came when he dominated his rivals with a nearly 20-length victory in the Pacific Classic (G1) at Del Mar, effectively extinguishing doubts that he could go the mile and a quarter. Prat looked over his shoulder when he couldn’t hear hoof beats behind him and eased his colt to the wire.

Admirers calculate he has won his five races by a total of more than 62 lengths. Let that sink in.

Flightline may have dominated the 2021 Triple Crown series had he not been injured while being started as a two-year-old. The colt was in Ocala when the latch on a stall door compromised his hind leg.

“I wasn’t there, but it was at least six to eight inches,” Sadler said of the wound. “It was pretty deep, pretty ugly. That was one of the reasons he didn’t get to me until later.”

Flightline’s effective stride probably has a lot to do with his effortless proficiency over the racetrack. But with all his talent, the colt is not a piece of cake to train. His personality could be called cheeky, exuberant or brazen on any given day.

“He’s a very tough horse to gallop,” Sadler said. “In the barn he’s not a pussycat—he’s all horse. He’s all man, that’s for sure.”

“He really does have a big stride,” Sadler added. “He’s just one of those exceptional horses that comes along very rarely in the Thoroughbred world. I’m just trying to enjoy him every single day, because he’s that special. It’s really exciting; I feel very blessed to have him.”

Flightline’s future will be determined following his run in the Breeders’ Cup Classic. According to Sadler, the ownership group is an agreeable lot. Upon retirement, he will stand at Lane’s End Farm.

“The decision will be made after the Breeders' Cup,” Sadler confirmed. “You want to see where the horse is after that race. And it’s not like anybody has a closed mind, one way or the other. We’ll wait and see what happens.”

It seems obvious that Sadler truly enjoys horses and particularly training racehorses. His barn is a well-oiled machine, with some employees that have been with him 20 and even 30 years. His barn is a team, a group effort.

“You want to like your employees because you spend so much time with them out here at the track,” he said. “I’m really pleased—I’ve got a really good crew; I’m blessed that way. Horses are hard; there are no cutting corners—no way to take two days off. It doesn’t work that way. I think a lot of guys like the routine. They know what’s expected of them; and if they like to work, it’s a great job.”

Sadler is not a man who toots his own horn. Hofmans remembers him as “a quiet guy” who always paid attention. John Sadler’s modesty seems refreshing in such a competitive industry.

A Fast Match

California-based trainer John Sadler has many accolades to his credit. One event that has gone fairly unnoticed through the years is a match race that took place in 1991.

The race was an idea that spun out of the racing office at the time. They wanted to match the three-time Quarter Horse 870-yard champion Griswold with a Thoroughbred sprinter.

“They proposed matching a really good half-mile horse from Los Alamitos, which really dominated over there,” Sadler said. “At that time, I had three or four really good sprinters. I thought I had the right horse for it—a horse called Valiant Pete.”

The race, boasting a $100,000 winner-take-all purse, was held April 20 at Santa Anita. The race was run at a distance of four furlongs (880 yards) and is remembered as “thrilling” to the few who remember it.

An obituary for Griswold (Merridoc), who died at the age of 25 in 2011, described the action:

“…the pair raced neck and neck throughout, with the Thoroughbred leading all the way to a world record-tying clocking of 44 1/5 seconds.”

Griswold later found revenge by beating Valiant Pete in the Marathon Handicap at Los Alamitos.

Probiotics – The key to a well-balanced equine gut

Article by Kerrie Kavanagh

It is no surprise that the health maintenance of the racehorse is a top priority for trainers. And probiotics can be used as a treatment modality to manipulate the gut microbiome to improve or maintain health. Equine studies to date have shown that probiotic strains can offer an advantageous approach to minimising disturbances in the gut microbial populations, repair these deficiencies—should they occur—and re-establish the protective role of the healthy gut microbiome. Other probiotic-associated health benefits include reducing diet-related diseases such as colic and laminitis, preventing diarrhoea, conferring host resistance to helminth infection, improving stress-related behavioural traits (e.g., locomotion) and even promote the development of an effective gut-brain communication pathway.

Probiotics have been used by humans for more than 5,000 years with their development closely linked to that of dairy products and fermented foods. Today, probiotics are seen as an excellent non-pharmaceutical way to improve the health of both humans and animals, and there are a plethora of products to choose from. But what exactly is a probiotic, and how do they work? Why would your horse need one? What types of probiotics are available for horses? These are all questions that horse trainers ask frequently, which we will attempt to answer here.

The Equine Gut Microbiome

Probiotics and the equine microbiome can benefit from a valuable symbiotic relationship; probiotics are seen as a restorative treatment modality for the gut, to re-establish the bacterial populations there and also to re-establish the protective role that the health gut microbiome confers to the host. But when we discuss the equine microbiome, what are we really talking about?

The gut microbiota/microbiome can be categorised by anatomical location such as the oral microbiota/microbiome in the mouth and the intestinal microbiota/microbiome in the intestines, etc. Therefore, the gut microbiome pertains to the microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract. This population of microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa) is referred to as the ‘microbiota’ of the gut, while the term ‘gut microbiome’ refers to the genetic material associated with these microorganisms. The microbiome can be defined as the sum of the microbes and their genomic elements in a particular environment. If we look at the definition of the microbiome having the propensity to an equation, then any equation must be balanced; to maintain that balance is key. If the microbial community exists in an environment in a balanced state, then any upset or disturbance to the microbial populations will cause the balance to shift (known as dysbiosis). To maintain the balance, we need to firstly understand the way the microorganisms exist within their community (i.e. their microorganism-to-microorganism interactions and also microorganism-to-environment interactions) and secondly, their functioning role. If we can understand their (microorganism) position and role, then we can maintain the balance or re-establish the balance if a shift occurs.

The human intestinal microbiome is now recognised as an organ and likewise, the equine intestinal microbiome is deemed an ‘organ’ of the body and is vital for the breakdown of complex food and subsequent release of energy, protection against the pathogenic bacterial colonisation and in regulating the immune system and metabolic functions. There has been much debate regarding the content of the healthy equine microbiome, and even to deduce what ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’ is requires a level of understanding of the microbiota associated with healthy horses. This question has been posed by many researchers and frankly has yet to be answered with certainty. There are many reasons why the ‘normal’ microbiota keeps eluding us; and this can be attributed to the many reasons as to why the gut microbiota (of a healthy horse) can be affected (see Figure 1). It is thought that the diversity of the human gut microbiota and the general assembly of microbial communities within the gut (with the dominant phyla being classed as belonging to Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes) is a shared hypothesis across most species (i.e., humans and animals share a similar gut microbiome structure). Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes have been shown to constitute the main dominant phyla in equine, bovine, canine and feline gut microbiome studies indicating the cruciality of the role they play in the maintenance of a healthy microbial ecology in the gastrointestinal tract. Several studies do agree that dominant phyla of the equine gut microbiota are obligate anaerobes: the gram-positive Firmicutes and the gram-negative Bacteroidetes; other phyla are identified as Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, Actinobacteria, Euryarchaeota, Fibrobacteres and Spirochaetes. Ninety-five percent of the Firmicutes phyla contains the Clostridia genus in addition to genera related to gut health such as Lachnospiraceae, Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcaceae. The other main dominant phyla, Bacteroidetes, on the other hand contains a large variety of the genus.

Role of the Equine Gut Microbiota

The role of the gut intestinal microbiota serves to protect and prevent disease. The gut microbiota has several purposes: prevention of pathogen colonisation by competing for nutrients, enrichment and maintenance of the intestinal barrier—their ability to renew gut epithelial cells and repair damage to the mucosal barrier, the breakdown of food and releasing energy and nutrients, such as synthesising vitamins D and K and also conserving and restoration of the immune system by the formation of antimicrobial metabolites and blocking access to the binding sites of the mucosal wall. The gut microbiota is also thought to play some role of influencing the neuro-active pathways that affect behaviour. It is not surprising to see that gut disorders and gastrointestinal diseases can arise when gut dysbiosis occurs. The role of the gut microbiota may have even more importance than is realised and may have a role to play with developing illness or disease later in life.

The microbial colonisation of the intestinal tract begins at birth. The foal begins its colonisation through contact with the microbiota of the mare’s vaginal and skin surfaces plus the surrounding environments to which the foal is exposed and reaches a relatively stable population by approximately 60 days in age. It is perhaps a fight for dominance to achieve establishment in the gut among the bacterial populations that sees the foal’s microbiota as being more diverse and quick to change when compared to that of the older horse. The subsequent colonisation of the intestinal tract will reflect the foal’s diet, changing environment, introduction to other animals, ageing and health.

Figure 1: Factors that can lead to gut dysbiosis

What exactly is a probiotic?

The word ‘probiotic’ is of Greek origin meaning ‘for life’ and the WHO/FAO have defined probiotics as ‘live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host’. People have long believed that exposure to non-pathogenic microorganisms can benefit the health of humans and animals. The thinking behind this is that daily consumption of sufficient numbers of ‘good’ microorganisms (either bacteria or fungi) can maintain a healthy population of microorganisms in the gut and benefit overall health.

Probiotics are used to manipulate the bacterial populations of the gut in order to re-establish the delicate microbial balance there which, in turn, confers health benefits on the host. As the benefits associated with some of the ‘good’ bacteria within the gut became known, these were referred to as probiotic bacteria.

How do probiotics work?

There are 4 main mechanisms by which probiotics are thought to exert their effects.

By inhibiting pathogen colonisation in the gut through the production of antimicrobial metabolites or by competitive exclusion; in other words, they prevent the ‘bad’ bacteria from growing in the gut.

By protecting or re-stabilising the commensal gut microbiota, probiotics can be a means to re-establish the balance of the gut microbial populations.

By protecting the intestinal epithelial barrier, they maintain the health of the intestinal wall.

By inducing an immune response, probiotics can boost the immune response and help prevent disease.

If we consider the definition of a probiotic as ‘live non-pathogenic microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host’, then this reference to ‘adequate amounts’ must be emphasised, and the dose administered is critical to ensure that the probiotic has the desired effect. For horses, we must consider the route through the digestive tract that the probiotic strains must travel to arrive at their destination is a distance over 15 metres long. It is a race for survival! The gastrointestinal system has many obstacles along the passage such as the acidic stomach environment and the dangers of exposure to bile and digestive enzymes, in which they must survive. The initial dose of ‘live’ probiotic strains is therefore crucial to ensure survival in the gut. Prebiotics are ingredients such as carbohydrates and fibre, which promote the growth of these probiotic bacterial/yeast strains in the gut. Prebiotics are essentially the food for the probiotic strains and can help form a symbiotic relationship with the probiotic to improve the overall health status of the horse.

Why would you need to give your horse a probiotic?

Gut dysbiosis is a fluctuation or disturbance in the population of microorganisms of the gut, which may be linked to a wide range of diseases in horses. Gut dysbiosis can be caused by many factors ranging from dietary changes, antibiotics, disease, intense exercise and training, age, worms, environment, travel, or even minor stress events—resulting in major consequences such as colic. Dysbiosis is generally associated with a reduction in microbial species diversity.

Diet is one of the major factors contributing to gut dysbiosis. Unlike the ruminant cattle and sheep that use foregut fermentation, horses are hindgut fermenters. The large intestine is the main area where fermentation occurs. The horse utilises the microbial enzymes of the hindgut microbial population in the colon and caecum to break down the plant fibres (cellulose fermentation) sourced mainly from grasses and hay. The horse itself does not possess the hydrolytic enzymes that are required to break the bonds of the complex structures of the plant carbohydrates (in the form of celluloses, hemicelluloses, pectins) and starch; so therefore, it strongly relies on the microbiota present to provide those critical enzymes required for digestion. The main phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes possess enzymes capable of breaking down the complex carbohydrates (such as starch and cellulose).

Research has shown that forage-based diets (grasses and hay) promote the most stable gut microbiomes, but ultimately the equine athlete requires far more energy than a forage-based diet can supply. Supplementing the diet with concentrates containing starch such as grain, corn, barley and oats can affect the number and type of bacteria in the gut. Optimising diet composition is so important as carbohydrate overload—as seen with high-starch diets (>1g/kg body weight per meal)—can change the populations of bacteria in the gut, alter pH, upset digestion and the gut environment, and ultimately result in diseases such as colitis, colic and laminitis. The correct diet is essential for maintaining the delicate balance of bacterial populations. Probiotics can be used to either replace the bacteria missing in the gut and/or can help maintain the delicate microbial balance even in the face of adversity such as abrupt dietary changes, antibiotic treatment and stress.

What types of probiotics are available for horses?

There are several probiotic products on the market, and most are in powder or liquid form. There are two main categories of probiotics: generic and autogenous. Generic probiotics are off-the-shelf products that contain specific strains of bacterial or yeast, singularly or in combination. The Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium families, Enterococci and yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisae and boulardii are the most common equine probiotic strains. Advantages of generic probiotics are that they are widely available, easy to administer, and they may be beneficial to horse health (if the strains are alive in sufficient numbers). Autogenous probiotics are specifically formulated using bacteria obtained from the horse’s own faecal sample and, as such, are uniquely adapted to that individual animal. These host-adapted bacteria are more likely to survive in the gut than non-adapted generic strains and can quickly replenish absent or low levels of bacteria unique to the individual horse, thus maintaining health.

EIPH - could there be links to sudden death and pulmonary haemorrhage?

Dr Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS, explores preliminary research and hypotheses, being conducted by the University of Guelph, to see if there is a possibility that these conditions are linked and what this could mean for future management and training of thoroughbreds.

"World's Your Oyster,” a three-year-old thoroughbred mare, presented at the veterinary hospital for clinical examination. She won her maiden start as a two-year-old and placed once in two subsequent starts. After training well as a three-year-old, she failed to finish her first start, easing at the top of the stretch, and was observed to fade abruptly during training. Some irregularity was suspected in heart rhythm after exercise. Thorough clinical examination, blood work, ultrasound of the heart and an ECG during rest and workout revealed nothing unusual.

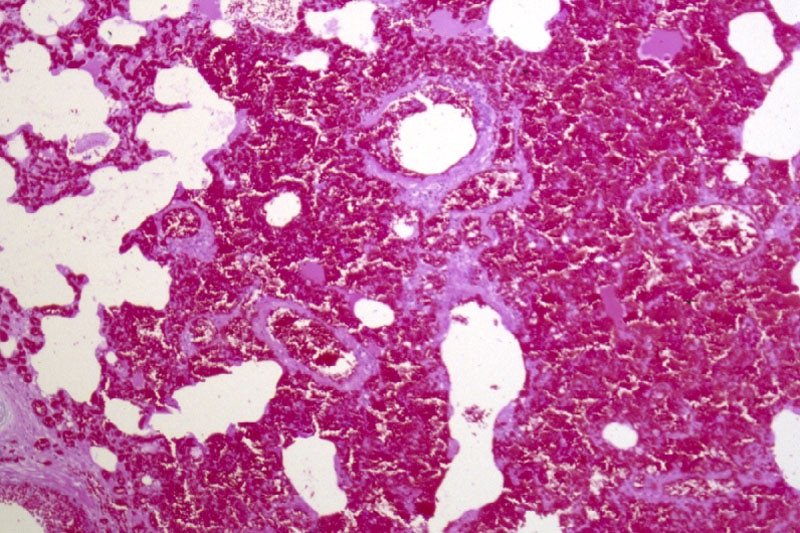

Returning to training, Oyster placed in six of her subsequent eight starts, winning the last two. She subsequently died suddenly during early training as a four-year-old. At post-mortem, diagnoses of pulmonary haemorrhage and exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage were established—a very frustrating and unfortunate outcome.

Across the racing world, a case like this probably occurs daily. Anything that can limit a horse's ability to express its genetic potential is a major source of anxiety when training. The possibility of injury and lameness is the greatest concern, but a close second is respiratory disease, with bleeding from the lungs (most often referred to as exercise induced pulmonary [lung] haemorrhage or EIPH) being high on the list.

EIPH is thought to occur in as many as 85 percent of racehorses, and may initially be very mild without obvious clinical consequences. In some cases it can be associated with haemorrhage of sufficient severity for blood to appear at the nostrils, even at first occurrence. In many racing jurisdictions this is a potentially career-ending problem. In these horses, an impact on performance is unquestionable. Bleeding from the lungs is the reason for the existence of ‘Lasix programs,’ involving pre-race administration of a medication considered to reduce haemorrhage. Such programs are controversial—the justifications for their existence ranging from addressing welfare concerns for the horse to dealing with the performance impacts.

Much less frequently encountered is heavy exercise-associated bleeding from the nostrils (referred to as epistaxis), which can sometimes be accompanied by sudden death, during or shortly after exercise. Some horses bleed heavily internally and die without blood appearing at the nostrils. Haemorrhage may only become obvious when the horse is lying on its side, or not until post-mortem. Affected animals do not necessarily have any history of EIPH, either clinically or sub-clinically. There is an additional group of rare cases in which a horse simply dies suddenly, most often very soon after work and even after a winning performance, and in which little to nothing clearly explains the cause on post-mortem. This is despite the fact most racing jurisdictions study sudden death cases very closely.

EIPH is diagnosed most often by bronchoscopy—passing an endoscope into the lung after work and taking a look. In suspected but mild cases, there may not be sufficient haemorrhage to be visible, and a procedure called a bronchoalveolar lavage is performed. The airways are rinsed and fluid is collected and examined microscopically to identify signs of bleeding. Scoping to confirm diagnosis is usually a minimum requirement before a horse can be placed on a Lasix program.

Are EIPH, severe pulmonary haemorrhage and sudden death related? Are they the same or different conditions?

At the University of Guelph, we are working on the hypothesis that most often they are not different—that it’s degrees of the same condition, or closely related conditions perhaps with a common underlying cause. We see varying clinical signs as being essentially a reflection of severity and speed of onset of underlying problems.

Causes in individual cases may reflect multiple factors, so coming at the issues from several different directions, as is the case with the range of ongoing studies, is a good way to go so long as study subjects and cases are comparable and thoroughly documented. However, starting from the hypothesis that these may all represent basically the same clinical condition, we are approaching the problem from a clinical perspective, which is that cardiac dysfunction is the common cause.

Numerous cardiac disorders and cellular mechanisms have the potential to contribute to transient or complete pump (heart) failure. However, identifying them as potential disease candidates does not specifically identify the role they may have played, if any, in a case of heart failure and in lung haemorrhage; it only means that they are potential primary underlying triggers. It isn't possible for us to be right there when a haemorrhage event occurs, so almost invariably we are left looking at the outcome—the event of interest has passed. These concerns influence the approach we are taking.

Background

The superlative performance ability of a horse depends on many physical factors:

Huge ventilatory (ability to move air) and gas exchange capacity

Body structure including limb length and design - allows it to cover ground rapidly with a long stride

Metabolic adaptations - supports a high rate of energy production by burning oxygen, tolerance of severe metabolic disruptions toward the end of race-intensity effort

High cardiovascular capacity - allows the average horse to pump roughly a brimming bathtub of blood every minute

At race intensity effort, these mechanisms, and more, have to work in coordination to support performance. There is likely not much reserve left—two furlongs (400m) from the winning post—even in the best of horses. There are many wild cards, from how the horse is feeling on race day to how the race plays out; and in all horses there will be a ceiling to performance. That ceiling—the factor limiting performance—may differ from horse to horse and even from day to day. There’s no guarantee that in any particular competition circumstances will allow the horse to perform within its own limitations. One of these factors involves the left side of the heart, from which blood is driven around the body to the muscles.

A weak link - filling the left ventricle

The cardiovascular system of the horse exhibits features that help sustain a high cardiac output at peak effort. The feature of concern here is the high exercise pressure in the circulation from the right ventricle, through the lungs to the left ventricle. At intense effort and high heart rates, there is very little time available to fill the left ventricle—sometimes as little as 1/10 of a second; and if the chamber cannot fill properly, it cannot empty properly and cardiac output will fall. The circumstances required to achieve adequate filling include the readiness of the chamber to relax to accept blood—its ‘stiffness.’ Chamber stiffness increases greatly at exercise, and this stiffened chamber must relax rapidly in order to fill. That relaxation seems not to be sufficient on its own in the horse at high heart rates. Increased filling pressure from the circulation draining the lungs is also required. But there is a weak point: the pulmonary capillaries.

These are tiny vessels conducting blood across the lungs from the pulmonary artery to the pulmonary veins. During this transit, all the gas exchange needed to support exercise takes place. The physiology of other species tells us that the trained lung circulation achieves maximum flow (equivalent to cardiac output) by reducing resistance in those small vessels. This process effectively increases lung blood flow reserve by, among other things, dilating small vessels. Effectively, resistance to the flow of blood through the lungs is minimised. We know this occurs in horses as it does in other species; yet in the horse, blood pressure in the lungs still increases dramatically at exercise.

If this increase is not the result of resistance in the small vessels, it must reflect something else, and that appears to be resistance to flow into the left chamber. This means the entire lung circulation is exposed to the same pressures, including the thin-walled capillaries. Capillaries normally work at quite low pressure, but in the exercising horse, they must tolerate very high pressures. They have thin walls and little between them, and the air exchange sacs in the lung. This makes them vulnerable. It's not surprising they sometimes rupture, resulting in lung haemorrhage.

Recent studies identified changes in the structure of small veins through which the blood flows from the capillaries and on toward the left chamber. This was suspected to be a pathology and part of the long-term consequences of EIPH, or perhaps even part of the cause as the changes were first identified in EIPH cases. It could be, however, that remodelling is a normal response to the very high blood flow through the lungs—a way of increasing lung flow reserve, which is an important determinant of maximum rate of aerobic working.

The more lung flow reserve, the more cardiac output and the more aerobic work an animal can perform. The same vein changes have been observed in non-racing horses and horses without any history or signs of bleeding. They may even be an indication that everything is proceeding as required and a predictable consequence of intense aerobic training. On the other hand, they may be an indication in some horses that the rate of exercise blood flow through their lungs is a little more than they can tolerate, necessitating some restructuring. We have lots to learn on this point.

If the capacity to accommodate blood flow through the lungs is critical, and limiting, then anything that further compromises this process is likely to be of major importance. It starts to sound very much as though the horse has a design problem, but we shouldn't rush to judgement. Horses were probably not designed for the very intense and sustained effort we ask of them in a race. Real-world situations that would have driven their evolution would have required a sprint performance (to avoid ambush predators such as lions) or a prolonged slower-paced performance to evade predators such as wolves, with only the unlucky victim being pushed to the limit and not the entire herd.

Lung blood flow and pulmonary oedema

There is another important element to this story. High pressures in the capillaries in the lung will be associated with significant movement of fluid from the capillaries into lung tissue spaces. This movement in fact happens continuously at all levels of effort and throughout the body—it's a normal process. It's the reason the skin on your ankles ‘sticks’ to the underlying structures when you are standing for a long time. So long as you keep moving a little, the lymphatic system will draw away the fluid.

In a diseased lung, tissue fluid accumulation is referred to as pulmonary oedema, and its presence or absence has often been used to help characterise lung pathologies. The lung lymphatic system can be overwhelmed when tissue fluid is produced very rapidly. When a horse experiences sudden heart failure, such as when the supporting structures of a critical valve fail, one result is massive overproduction of lung tissue fluid and appearance of copious amounts of bloody fluid from the nostrils.

The increase in capillary pressure under these conditions is as great as at exercise, but the horse is at rest. So why is there no bloody fluid in the average, normal horse after a race? It’s because this system operates very efficiently at the high respiratory rates found during work: tissue fluid is pumped back into the circulation, and fluid does not accumulate. The fluid is pumped out as quickly as it is formed. An animal’s level of physical activity at the time problems develop can therefore make a profound difference to the clinical signs seen and to the pathology.

Usual events with unusual consequences

If filling the left ventricle and the ability of the lungs to accommodate high flow at exercise are limiting factors, surely this affects all horses. So why do we see such a wide range of clinical pictures, from normal to subclinical haemorrhage to sudden death?

Variation in contributing factors such as type of horse, type and intensity of work, sudden and unanticipated changes in work intensity, level of training in relation to work and the presence of disease states are all variables that could influence when and how clinical signs are seen, but there are other considerations.

Although we talk about heart rate as a fairly stable event, there is in fact quite a lot of variation from beat to beat. This is often referred to as heart rate variability. There has been a lot of work performed on the magnitude of this variability at rest and in response to various short-term disturbances and at light exercise in the horse, but not a lot at maximal exercise. Sustained heart rate can be very high in a strenuously working horse, with beats seeming to follow each other in a very consistent manner, but there is in fact still variation.

Some of this variation is normal and reflects the influence of factors such as respiration. However, other variations in rate can reflect changes in heart rhythm. Still other variations may not seem to change rhythm at all but may instead reflect the way electrical signals are being conducted through the heart.

These may be evident from the ECG but would not appear abnormal on a heart rate monitor or when listening. These variations, whether physiologic (normal) or a reflection of abnormal function, will have a presently, poorly understood influence on blood flow through the lungs and heart—and on cardiac filling. Influences may be minimal at low rates, but what happens at a heart rate over 200 and in an animal working at the limits of its capacity?

Normal electrical activation of the heart follows a pattern that results in an orderly sequence of heart muscle contraction, and that provides optimal emptying of the ventricles. Chamber relaxation complements this process.

An abnormal beat or abnormal interval can compromise filling and/or emptying of the left ventricle, leaving more blood to be discharged in the next cycle and back up through the lungs, raising pulmonary venous pressure. A sequence of abnormal beats can lead to a progressive backup of blood, and there may not be the capacity to hold it—even for one quarter of a second, a whole cardiac cycle at 240 beats per minute.

For a horse that has a history of bleeding and happens to be already functioning at a very marginal level, even minor disturbances in heart rhythm might therefore have an impact. Horses with airway disease or upper airway obstructions, such as roarers, might find themselves in a similar position. An animal that has not bled previously might bleed a little, one that has a history of bleeding may start again, or a chronic bleeder may worsen.

Relatively minor disturbances in cardiac function, therefore, might contribute to or even cause EIPH. If a horse is in relatively tough company or runs a hard race, this may also contribute to the onset or worsening of problems. Simply put, it's never a level playing field if you are running on the edge.

Severe bleeding

It has been suspected for many years that cases of horses dying suddenly at exercise represent sudden-onset cardiac dysfunction—most likely a rhythm disturbance. If the rhythm is disturbed, the closely linked and carefully orchestrated sequence of events that leads to filling of the left ventricle is also disturbed. A disturbance in cardiac electrical conduction would have a similar effect, such as one causing the two sides of the heart to fall out of step, even though the rhythm of the heart may seem normal.

The cases of horses that bleed profusely at exercise and even those that die suddenly without any post-mortem findings can be seen to follow naturally from this chain of events. If the changes in heart rhythm or conduction are sufficient, in some cases to cause massive pulmonary haemorrhage, they may be sufficient in other cases to cause collapse and death even before the horse has time to exhibit epistaxis or even clear evidence of bleeding into the lungs.

EIPH and dying suddenly

If these events are (sometimes) related, why is it that some horses that die of pulmonary haemorrhage with epistaxis do not show evidence of chronic EIPH? This is one of those $40,000 questions. It could be that young horses have had limited opportunity to develop chronic EIPH; it may be that we are wrong and the conditions are entirely unrelated. But it seems more likely that in these cases, the rhythm or conduction disturbance was sufficiently severe and/or rapid in onset to cause a precipitous fall in blood pressure with the animal passing out and dying rapidly.

In this interpretation of events, the missing link is the heart. There is no finite cutoff at which a case ceases to be EIPH and becomes pulmonary haemorrhage. Similarly, there is no distinct point at which any case ceases to be severe EIPH and becomes EAFPH (exercise-associated fatal pulmonary haemorrhage). In truth, there may simply be gradation obscured somewhat by variable definitions and examination protocols and interpretations.

The timing of death

It seems from the above that death should most likely take place during work, and it often does, but not always. It may occur at rest, after exercise. Death ought to occur more often in racing, but it doesn't.

The intensity of effort is only one factor in this hypothesis of acute cardiac or pump failure. We also have to consider factors such as when rhythm disturbances are most likely to occur (during recovery is a favourite time) and death during training is more often a problem than during a race.

A somewhat hidden ingredient in this equation is possibly the animal's level of emotional arousal, which is known to be a risk factor in humans for similar disturbances. There is evidence that emotions/psychological factors might be much more important in horses than previously considered. Going out for a workout might be more stimulating for a racehorse than a race because before a race, there is much more buildup and the horse has more time to adequately warm up psychologically. And then, of course, temperament also needs to be considered. These are yet further reasons that we have a great deal to learn.

Our strategy at the University of Guelph

These problems are something we cannot afford to tolerate, for numerous reasons—from perspectives of welfare and public perception to rider safety and economics. Our aim is to increase our understanding of cardiac contributions by identifying sensitive markers that will enable us to say with confidence whether cardiac dysfunction—basically transient or complete heart failure—has played a role in acute events.

We are also looking for evidence of compromised cardiac function in all horses, from those that appear normal and perform well, through those that experience haemorrhage, to those that die suddenly without apparent cause. Our hope is that we can not only identify horses at risk, but also focus further work on the role of the heart as well as the significance of specific mechanisms. And we hope to better understand possible cardiac contributions to EIPH in the process. This will involve digging deeply into some aspects of cellular function in the heart muscle, the myocardium of the horse, as well as studying ECG features that may provide insight and direction.

Fundraising is underway to generate seed money for matching fund proposals, and grant applications are in preparation for specific, targeted investigations. Our studies complement those being carried out in numerous, different centres around the world and hopefully will fill in further pieces of the puzzle. This is, indeed, a huge jigsaw, but we are proceeding on the basis that you can eat an elephant if you're prepared to process one bite at a time.

How can you help? Funding is an eternal issue. For all the money that is invested in horses there is a surprisingly limited contribution made to research and development—something that is a mainstay of virtually every other industry; and this is an industry.

Look carefully at the opportunities for you to make a contribution to research in your area. Consider supporting studies by making your experience, expertise and horses available for data collection and minimally invasive procedures such as blood sampling.

Connect with the researchers in your area and find out how you can help. Watch your horses closely and contemplate what they might be telling you—it's easy to start believing in ourselves and to stop asking questions. Keep meticulous records of events involving horses in your care— you never know when you may come across something highly significant. And work with researchers (which often includes track practitioners) to make your data available for study.

Remember that veterinarians and university faculty are bound by rules of confidentiality, which means what you tell them should never be ascribed to you or your horses and will only be used without any attribution, anonymously. And when researchers reach out to you to tell you what they have found and to get your reactions, consider actually attending the sessions and participating in the discussion; we can all benefit—especially the ultimate beneficiary which should be the horse. We all have lots to learn from each other, and finding answers to our many challenges is going to have to be a joint venture.

Finally, this article has been written for anybody involved in racing to understand, but covering material such as this for a broad audience is challenging. So, if there are still pieces that you find obscure, reach out for help in interpretation. The answers may be closer than you think!

Oyster

And what about Oyster? Her career was short. Perhaps, had we known precisely what was going on, we might have been able to treat her, or at least withdraw her from racing and avoid a death during work with all the associated dangers—especially to the rider and the associated welfare concerns.

Had we had the tools, we might have been able to confirm that whatever the underlying cause, she had cardiac problems and was perhaps predisposed to an early death during work. With all the other studies going on, and knowing the issue was cardiac, we might have been able to target her assessment to identify specific issues known to predispose.

In the future, greater insight and understanding might allow us to breed away from these issues and to better understand how we might accommodate individual variation among horses in our approaches to selection, preparation and competition. There might be a lot of Oysters out there!

For further information about the work being undertaken by the University of Guelph

Contact - Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS.

Professor Emeritus, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph - pphysick@uoguelph.ca

Research collaborators - Dr Glen Pyle, Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph - gpyle@uoguelph.ca

Dr Amanda Avison, PhD Candidate, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph. ajowett@uoguelph.ca

References

Caswell, J.I. and Williams K.J. (2015), Respiratory System, In ed. Maxie, M. Grant, 3 vols., 6th edn., Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 2; London: Elsevier Health Sciences, 490-91.

Hinchcliff, KW, et al. (2015), Exercise induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses: American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement, J Vet Intern Med, 29 (3), 743-58.

Rocchigiani, G, et al. (2022), Pulmonary bleeding in racehorses: A gross, histologic, and ultrastructural comparison of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage and exercise-associated fatal pulmonary hemorrhage, Vet Pathol, 16:3009858221117859. doi: 10.1177/03009858221117859. Online ahead of print.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.

Vitalie, Faoro (2019), Pulmonary Vascular Reserve and Aerobic Exercise Capacity, in Interventional Pulmonology and Pulmonary Hypertension, Kevin, Forton (ed.), (Rijeka: IntechOpen), Ch. 5, 59-69.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.

Celebrating breeders - Tom Egan - the owner breeder of NY bred superstar - Red Knight

Words by Bill Heller

Winning a stakes race, let alone a graded stakes, is a thrill for any Thoroughbred owner. But what if you also bred that horse? That’s special—literally choosing the mating, then deciding to keep him rather than sell him at auction, and waiting a year or two to race him.

Now imagine—with just 151 career starts as an owner of 14 Thoroughbreds—that horse was the last one you own after 50 years of loving, working with and racing horses.

Like every other owner, 75-year-old Tom Egan was told never to fall in love with his horses. He couldn’t help himself with Red Knight, a remarkable eight-year-old gelding who returned from an 11-month layoff to capture the $156,000 Colonial Cup at Colonial Downs and the $694,180 Gr. 2 Kentucky Turf Cup Stakes at Kentucky Downs by a nose.

“Red is my last horse,” Egan said. “I’m very close to him.”

He just wishes his wife Jaye, who died December 30, 2016, at the age of 53 after a brave, 17-year battle with breast cancer, was with him to enjoy Red Knight’s success. “Racing isn’t the same without her. Marriage isn’t the same. We accomplished so much more than we could have hoped. My wife was such a beautiful person. Shared joy is better than joy.”

They met in July 1990. “I took her, with much trepidation, to Saratoga,” he said. “I thought, `Is she going to like it? What if she thinks it’s silly?’”

She thought it was wonderful. “Man, she loved it, she wanted to get there before the first race and stay until after the ninth.”

Egan’s interest in Thoroughbreds traces back to his father, Lester, an attorney in Hartford, Connecticut, who loved gambling and horse racing. “My dad was primarily a tax attorney; to me, it was too boring.”

Egan, who now lives in Ocala, also became an attorney after attending the University of Hartford and Quinnipiac Law School. “I did personal injury, criminal law and eminent domain.”

Asked if he enjoyed it, Egan said, “There were only two things wrong with the practice of law: judges and clients.”

Mostly retired now, he said he’s a “recovering attorney.” A couple of long-time clients still use his services.

Egan’s first visit to a racetrack came in 1971 at Rockingham. He then attended Suffolk Downs before visiting Saratoga and Belmont Park. In 1976, he took a job working as a hot-walker and groom at a farm in Massachusetts, then with John Russell, who was training for the powerful Phipps Stable.

But he didn’t stick to racing, attending law school and beginning a career.

His first horse was a pleasure horse, Rebel, in 1970. “I rode him on weekends. He did what I wanted him to do: run fast and true.”

Egan’s first Thoroughbred was Shadow, a grandson of Forward Pass. Egan began riding jumpers with him. “I got up to 3-foot-3. Shadow could jump 4-9.”

More than 30 years later, with the love of his life in hand, he plunged into Thoroughbred ownership—modestly. He decided to race and breed under the name of Trinity Stable, even though there is no stable nor farm. The 250-year-old Trinity Church behind his house was his inspiration.

In 2003, the Egans purchased the dam Isabel Away, a daughter of Horse of the Year Skip Away, at the Keeneland Sale, for $60,000. “My wife saw the mare and said that we just had to have her. I think the first thing she liked was her color, but upon closer examination, she really liked her an awful lot. When I saw her in the back walking ring before she went out to the sales ring, she was just very classy and composed. At that point, I said, `Yeah, sounds good.’”

Though she won just one of 11 lifetime starts, she would produce two New York-bred geldings who have combined to win more than $1.8 million. And Red Knight isn’t done racing.

The following April, the Egans were at Keeneland for the spring meet. “We met a trainer, and he said, `Ninety-five percent of owners get involved because of status.’ My wife calmly looked at him and said, `We’ve been here three days. We had no seats; we don’t know anybody, and we’ve had a lovely time.’”

Ten years later, the older of the two brothers, Macagone (pronounced Ma-ka-gon), a speedy son of Artie Schiller, took the Egans on quite a run. After being claimed away from the Egans for $40,000 on June 27, 2018, Macagone continued racing until the age of nine, finishing with 11 victories, six seconds and eight thirds from 47 starts with earnings of $654,981.

Identifying Macagone was easier than pronouncing his name correctly. “Tom Durkin, the greatest race caller ever, even got it wrong. I had a couple of friends talk to him about the pronunciation. He couldn’t get it. I was in downtown Saratoga at an Italian designer’s shop one morning and I was admiring one sports jacket. The owner of the store said he had made it for Tom Durkin, and he was picking it up the next morning. I put a note in his jacket with the horse’s name. Tom pronounced it correctly every time after that.”

Egan called Macagone “...a cool horse; he reminded me of Sonny Liston in the paddock—a bay with no white markings. He had that look about him: `I’m here, I know what I’m doing, and I’m going to kick your ass.’ He beat some very good horses.”

For the Egans, Macagone captured the stakes named for his sire, the Artie Schiller at Aqueduct, by three-quarters of a length at 34-1. Announcer John Imbriale made the call, “A son of Artie Schiller wins the Artie Schiller at 34-1!” Macagone also won consecutive runnings of the Danger’s Hour Stakes at Aqueduct before finishing third in it. After he was claimed, Macagone set a then track record at Saratoga, winning a one-mile New York-bred allowance in 1:33.13 on the Inner Turf Course.

Red Knight, a son of Pure Prize trained originally by Hall of Famer Bill Mott, put together a successful career in his first four years of racing, taking the 2020 Gr. 3 Sycamore at Keeneland and finishing second by a half-length a month later in the Gr. 3 Red Smith Handicap at Aqueduct.

Egan, acting on a tip from a friend, found out Red Knight loved raw, sliced sweet potatoes. “They’re palatable to the stomach of a horse,” Tom said. “A friend of mine suggested it.”

At the age of seven last year, Red Knight finished second in the Gr. 3 Louisville at Churchill Downs but didn’t hit the board in five other starts.

Egan decided to give him a long break and switch trainers. “It took him 11 months to get healthy,” Tom said. “I called Mike Maker. I said, `You don’t know me, but you might know my horse, Red Knight.’ He said, `Oh, yes I do.”

Maker has obviously done a splendid job with Red Knight, who in two starts has made 2022 Tom’s highest single-season in earnings. Red Knight’s success gave Egan a problem, a good problem to have: should he supplement Red Knight to the Gr. 1 $4 million Breeders’ Cup Turf for $100,000?

“I’m never going to have that problem again,” Egan said.

Either way, Egan has already been working with his good friend, Laura Fonde, a hunter-jumper rider, to transition Red Knight to a successful and meaningful second career. “He’s never going to be happy just standing out there in a field.”

He knows his horse, who has 10 victories, eight seconds and one third from 29 starts with earnings of more than $1.2 million. Earlier this year, he knew his horse wasn’t done racing at its highest level. If not, he would have retired him. “I could tell that he still had it in him.”

Tom Egan knew. Maybe Jaye Egan did too.

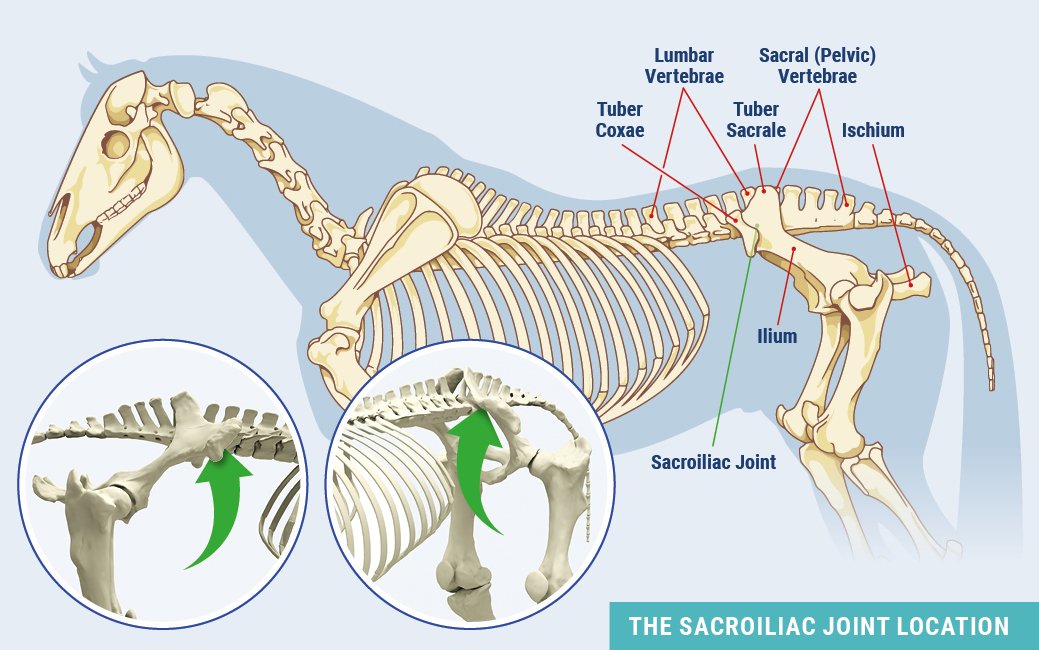

The Often Overlooked Equine Sacroiliac Joint

Horses that present as sore in the hindquarters can be perplexing to diagnose. Sometimes the problem is found in the last place you look – the sacroiliac joint.

Article by Annie Lambert

Even though the sacroiliac joint (SI) was on veterinary radars long ago, due to its location buried under layers of muscle in the equine pelvic region, the joint and surrounding ligaments were tough to diagnose and treat.

The sacroiliac joint is often a source of lower back discomfort in race and performance horses. Trainers may notice several clinical signs of a problem. These hints include sensitivity to grooming, objections to riders getting legged up, stiffness of motion, pain to manual palpation of the rump or back, resistance to being shod behind and poor performance.

Of course, those symptoms could describe other hind limb soundness issues, making the origin of the problem arduous to ascertain. A thorough physical examination with complete therapeutic options can relieve sacroiliac pain. The treatments are complicated, however, by the anatomy of the SI area.

The equine pelvis is composed of three fused bones: ilium, ischium and pubis. The sacrum, the lower part of the equine back, is composed of five fused vertebrae. The sacroiliac joint is located where the sacrum passes under the top of the pelvis (tubera sacrale). The dorsal, ventral and interosseous sacroiliac ligaments help strengthen the SI joint.

The SI and surrounding ligaments provide support during weight bearing, helping to transfer propulsive forces of the hind limbs to the vertebral column—creating motion much like the thrust needed to break from the starting gate.

Sound complicated? It certainly can be.

Diagnosing Dilemmas

It wasn’t until modern medical technology advanced that the SI could be explored seriously as a cause of hind lameness.

“The sacroiliac is one of the areas that’s very hard to diagnose or image,” explained Dr. Michael Manno, a senior partner of San Dieguito Equine Group in San Marcos, California. “[Diagnostics] of the area probably correlated with bone scans or nuclear scintigraphy. You can’t really use radiographs because the horse is so massive and there is so much muscle, you can’t get a good image.

“About the only time you can focus on the pelvis and get a decent radiograph is if the horse is anesthetized—you have a big [x-ray] machine and could lay the horse down. But, it’s hard because with anything close to a pelvic injury, the last thing you want to do is lay them down and have them have to get back up.”

The nuclear scintigraphs give a good image of hip, pelvis and other anatomical structures buried deep in the equine body, according to Manno, a racetrack practitioner. “Those images can show areas of inflammation that could pretty much be linked right to the SI joint.”

The other modern technological workhorse in the veterinary toolbox is the digital ultrasound machine. Manno pointed out that veterinarians improved diagnostics as they improved their ultrasounding skills and used those skills to ultrasound areas of the body they never thought about before. Using different techniques, frequencies and various heads on the machine’s probe, the results can be fairly remarkable.

“The ultrasound showed you could really image deeper areas of the body, including an image of the sacroiliac joint,” Manno said. “It can also show some ligament issues.”

Where the SI is buried under the highest point of a horse’s rump, and under heavy gluteal muscles, there are two sets of ligaments that may sustain damage and cause pain. The dorsal sacroiliac ligaments do not affect the sacroiliac joint directly, but help secure the ilium to the sacral spine. The ventral sacroiliac ligaments lie deeper, in the sacroiliac joint area, which they help stabilize. These hold the pelvis tight against its spine. The joint itself, being well secured by these ligaments, has little independent movement and therefore contains only minimal joint fluid.

Diagnosing the SI can be complex because horses often travel their normal gait with no change from normal motion—no signs of soreness. Other horses, however, are sore on one leg or another to varying degrees, sometimes with a perceptible limp.

“I don’t know that there is a specific motion,” Manno explained. “You just know that you have a hind end lameness, and I think a lot of performance horses have mildly affected SI joints.

“The horses that are really severe become acutely lame behind, very distinct. You go through the basic diagnostics, and I think most of these horses will show you similar signs as other issues behind. We palpate along the muscles on either side of their spine and they are sore, or you palpate over their croup and you can get them to drop down—that kind of thing. Other times you do an upper limb flexion on them and they might travel weird on the opposite leg. So, it can be a little confusing.”

In the years prior to the early 2000s, the anatomical location of the SI hindered a definite diagnosis; decisions on hind soreness were more of a shrug, “time and rest” treatment evaluation. As one old-time practitioner called it, a SWAG – “Scientific Wild Ass Guess.”

Even with modern tools, making a conclusive diagnosis can be opaque.

“The less affected horses, through exercise and with medications like Robaxin [muscle relaxer] or mild anti-inflammatories, seem to be able to continue to perform,” Manno said. “I don’t know how you can be perfectly sure of an inside joint unless you try to treat it and get results.”

“That’s why bone scans came into play and are really helpful,” Manno added. “You can image that [SI] area from different angles with the machine right over the path of the pelvis, looking down on it or an angle view into it, and then you see it from the side and the back very often. We can get an idea from the different views and angles of where the inflammation is and pinpoint the problem from that.”

Once Manno has a generalized idea of where the problem is, he fine-tunes his hypothesis using more diagnostics with a digital ultrasound machine.

“You can ultrasound from up above and see the joint that way,” he said. “As ultrasound has progressed, we’ve found that the rectal probes the breeding vets have used can also be tuned in to start looking for other things. If you turn them upwards, you can look at the bottom of the pelvis and the SI joint. You can see things through the rectum by just looking straight up. That is a whole new thing that we probably never thought about doing. I don’t profess to be very great at it; it’s not something I do a lot, but there are people that are just wonderful at it.”

Treating a Theorem

But, if the diagnosis is incorrect, the prescribed treatment may be anything but helpful.

“In many cases, if a horse is really sore, you need to be very careful,” cautioned Manno. “What you don’t want to do is go from a strain or some sort of soft tissue injury into a pelvic fracture by trying to keep them going. In many cases you are back in the old rest and time type of treatment.”

Manno pointed out one treatment that has advanced over many years is injecting the SI joint directly. There are a couple of techniques used when injecting the SI. With a blind injection the practitioner directs a long, straight needle into the joint by relying solely on equine anatomy. The other technique employs an ultrasound machine to guide the placement of the needle into the joint.

“Normally we are just injecting cortisone in those cases,” Manno noted. “We are trying to get the inflammatory response to settle down. Hopefully that gives the horse some relief so that they’re a bit more relaxed in their musculature. You know how it is when you get a sore back; it’s hard to keep yourself from cramping, which makes everything worse.”

A slight tweak of that technique is to use a curved needle. When you are positioning the curved needle, it follows the curve of the horse’s anatomy and helps the practitioner direct the injection into the joint.

“It curves right into position for you; it gives you a little help,” Manno confirmed of the curved needle. “Some people are really good with that technique; others still like to go to the straight needle. [The curved needle] helps you approach the site without interference from the bones in that area.”

SI joint injuries affect most performance horses, including Standardbred trotters and pacers, Western performance athletes as well as hunters, jumpers and dressage horses.

The older show horses are often diagnosed with chronic SI pain, sometimes complicated by arthritis. These chronic cases—and admittedly some racehorses—are treated with different therapies. These conservative, nonsurgical treatments have been proven effective.

In addition to stall rest and anti-inflammatories, physical training programs can be useful in tightening the equine patient’s core and developing the topline muscles toward warding off SI pain. Manno, a polo player who also treats polo ponies, believes the hard-working ponies avoid having many SI injuries due to their fitness levels.

“I think these polo horses are similar to a cross between a racehorse and a cutting horse,” Manno opined. “They are running distances and slide stopping and turning.”

Other treatments utilized include shockwave, chiropractic, acupuncture, therapeutic laser and pulsed electromagnetic therapy.

Superior Science

With the new diagnostic tools and advanced protocols in their use, veterinarians can pinpoint the SI joint and surrounding areas much closer. This gives them an improved indication that there definitely is an issue with the sacroiliac.

When there is a question about what is causing hind end lameness, most practitioners begin with blocking from the ground up.

“In many cases with hind end lameness that we can’t figure out, we block the lower leg; if it doesn’t block out down low, we conclude the problem is up high,” Manno said. “Once you get up to the hock you’re out of options of what you can figure out. You start shooting some x-rays, but by the time you get to the stifle, you’re limited. Bone scans and ultrasounds have certainly helped us with diagnosing.”

Manno doesn’t see a lot of SI joint injuries in his practice, but he noted there were cases every now and again. He also opined that there were probably other cases that come up in racehorses on a short-term basis. He also noted that, although it may not be a real prominent injury, that’s not to say it has not gone undiagnosed.

“I think we realize, in many of the horses we treat, that the SI joint is something that may have been overlooked in the past,” Manno concluded. “We just didn’t have the ability to get any firm diagnosis in that area.”

Patrick O’Keefe - Kentucky West Racing

Article by Bill Heller

Growing up in Ogden, Utah, Patrick O’Keefe never saw a racetrack. But it didn’t prevent him from falling in love with a horse.

Patrick did bond with his father through railroads. “I’m a two-generation railroad worker,” he said. “My dad worked for the Union Pacific Railroad. I worked there while I was going to college at the University of Utah. Just before I graduated, he had a heart attack and died. My railroad career ended at that point. So I hooked up with a good friend, Dennis Bullock. I loved golf. We went looking for a property to build a golf course. We looked all over the country. We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a lot of energy.”

Their search took them to Bear Lake, Idaho, near the southeast border of Idaho and Utah, and Patrick liked what he saw. They found the property owner and made a deal. “I gave him $10 down,” Patrick said. “I had to come up with $2,000.”

He did. They built a golf and country club, and then sold some 1,000 lots on the property. “I was pretty good at sales,” Patrick said.

On a fateful day, one of Patrick’s buddies from home, Wayne Call, paid a visit. He’d moved to the east and was back visiting family. “He lived right next to me in Ogden,” Patrick said. “His dad worked for Union Pacific.” Wayne, who had worked in bloodstock and trained a few horses, told Patrick he thought Bear Lake would be a great place to raise Thoroughbreds. Patrick told Wayne he thought it was too cold to raise horses but Wayne told him the cold kills parasites and limits disease. In Ray Paulick’s February 2022, story in the Paulick Report, Patrick said, “We have good water and several hundred acres, so I said I’d give it a try. I was dumb as a post. I had no background in racing whatever.”

So he leaned on Wayne and they took off for a nearby off-track betting facility in Evanston, Wyoming. “Wayne told me to look for a mare that’s won a lot of races that had good breeding,” Patrick said. He settled on Rita Rucker, a granddaughter of Danzig who’d won 21 races, including four stakes and earned $249,767. Her last start was in a $16,500 claimer, and Patrick got her for $7,500.

Patrick chose Kentucky West Racing—a courtesy to Wayne who once owned a hotel named Frontier West—as a stable name and bred Rita Rucker to Thunder Gulch. Patrick decided to raise the foal on his farm in Bear Lake. “My ranch is 200 acres,” he said. “We fenced a paddock. We had a little manger—a lean-to. When they unloaded Rita Rucker, she was absolutely gorgeous. I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

Rita Rucker foaled a filly. Patrick named her Private World, fitting his farm’s secluded area. “I’d drive up to the ranch two or three times a day,” Patrick said. “She’d see me coming and start to run along the fence line. That was her. She just loved to run.”

One snowy evening, she ran away. “Lots of snow, and I came to watch her one night,” Patrick said. “The fence was broken, and she was gone. My ranch adjoins the National Forest. What happened was an elk got through the fence to go after my feed. I saddled another horse and got a lariat. She was at the top of the mountain. I worked my way up to the top of the mountain. It was snowing. It was amazing. It took me hours to get her.”

But he did. “She was just a yearling,” Patrick said. “I built a barn for her.”