The Alan Balch Column - Future?

According to etymologists, the word “future” only dates to the 1300s.

Human life up to then, I guess, must have been so “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (to copy the philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ description of life outside society), that humanity could scarcely conceive of the very idea of a “future.”

If we could envision the concept of a future, I reason, we would have had a word for it.

This surprises me, since like so many other things it invented, horse racing may itself have started the first intense debates about what “the future” holds: according to the latest Artificial Intelligence, there was gaming on the races as far back as ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Way, way before the 14th century.

You have to understand the concept of “future” if you’re betting on an outcome that hasn’t yet occurred. Our entire sport, one might say, is “future-oriented.” If we knew with certainty what a result would be, we would have no game. And far, far less fun.

Just ask everyone who went against the bridge jumpers who bet the ranch on that 1-9 shot to show . . . which then didn’t.

Or, ask the breeders. They “breed the best to the best and hope for the best,” the aphorism often attributed to John E. Madden. Yes, that family . . . of Hamburg Place in Kentucky.

So, “future-orientation” is the foundation of horse racing in many respects, beginning with breeding. It’s also something I deeply considered in my last school days, and again in my early days of race track marketing at Santa Anita, more than half a century ago.

One of my teachers, Edward Banfield, wrote a controversial book, The Unheavenly City, in which he argued that social class distinctions in human society are not determined by heritable biological traits such as race, or similarities among income, occupations, schooling, or status. Those had been almost universally understood to cause classes among people, and it’s probably still a consensus. Instead, he held, a person’s class is determined by a “psychological orientation toward the future,” that is to say, whether a person is more or less oriented toward the future or the present. The more future-oriented, in his view, the “higher class.”

Gamblers, I found out through research, tend to be “present-oriented.” Tend to live “moment to moment.” And I saw this constantly throughout the race track, whether in the exclusive areas with dress codes for the ultra-wealthy, or on the grandstand main floor at the wire, where the blue-collar crowd congregated. Occupation, race, appearance, and income varied absurdly – the present-oriented bettors want action, now! Immediate gratification.

Banfield believed instead that a person’s relation to time gave them their “class culture,” which in turn then influenced their tastes and behavior.

Thoroughbred breeders are required by laws of nature to be future-oriented (mares requiring almost a year for gestation, added to the time necessary for planning matings); yet breeding is also, by definition, high-risk. Risk abounds everywhere else in racing, too. Isn’t this among the seductive allures and fascinations and contradictions racing provides, like no other sport?

In my track-management decades, the public companies I worked for always confronted the tension between earnings-per-share-this-quarter vs. investing for future growth. We couldn’t escape public disclosure of our audited financials, whether for shareholders or regulators. The discipline this required of California track management, unfortunately, seems to be a thing of the past, over more than the last two decades.

And the result looks increasingly catastrophic.

Every decision that any track management makes has to account for the size of the horse population available to race. This should go without saying -- but in California, it doesn’t! Management can announce the end of racing at a track which undergirds most of a state’s breeding, apparently without understanding or considering the consequences, not only for every other connected enterprise in the state, but also for itself. And without any objective evidence of the basis for its financial decision-making.

And, if it did understand or consider those consequences of its decisions, ponder the implications of having made them anyway.

In the 2025 Santa Anita meet which ended in June, California-breds accounted for just under half of all starts, an all-time high. As of May this year, not coincidentally, horses bred in California were over 51% of the total population stabled in the south, including 60% of the population at Los Alamitos. Every one of those was bred while year-around racing was conducted at Golden Gate Fields and the fairs in Northern California – where over 70% of starters were bred in the state.

As the North American foal crop has steadily declined, according to The Jockey Club Fact Book, the Kentucky share has been rising, to nearly 50% now. The California, Florida, and other shares, for the most part, have been declining precipitously. The implications of this are ominous for the geography of American racing as it has existed for nearly a century.

What the future holds will always be as mysterious as peering out into the vast universe with stark wonder. And all of us in racing know better than the rest of the world, and every investor, that “past performance is not indicative of future results.”

In our own California case, however, past performance has brought us to an exceptionally precarious position.

#Soundbites - How much do the opinions of others affect your yearling evaluations?

Bob Baffert

Bob Baffert

The opinions of others cloud my decisions sometimes. I like to go in it myself, my initial reaction when I look at the horse myself. I base it on what I see in the horse. I try to keep the outside noise out. I’ve made some mistakes by listening to other people sometimes. At the end of the day, I go with what people call is a gut feeling. I call it experience of what worked for me and what didn’t work for me.

Bruce Levine

Everybody’s got an opinion on a yearling. One guy will look at a horse and like him. The next guy - he just doesn’t like him. I do a physical. If the vet doesn’t like him, it’s very rare I’ll go against the vet. If he says it’s a 10 percent risk, that’s something different. Then I’ll let the price determine it. But if he’s telling me, “Stay away,” I’m staying away.

Mike Trombetta

When I’m making yearling selections, truthfully, everybody looks for different things. For me, personally, I like to tune out background noise and try to make my own decisions. Because, at the end of the day, I want to be happy with what I’ve selected and not so much based on what other people have to say.

Al Stall

A lot of people have teams, including myself. If it’s a team member, I’m all ears. Otherwise, I don’t really pay too much attention. We’ve been doing it a long time. We end up agreeing most of the time, and if we don’t agree we just throw it out and move on to the next. It’s us three, me and Frank and Daphne Wooten from Camden, South Carolina. They break our yearlings. We’ve been doing it together for quite a while. We’ve gotten lucky. Lucky is a very important word with yearlings.

Kathleen O’Connell

Everything is useful information. That’s the way I look at it. If you get to the point where you’re considering buying a yearling and a vet is telling you it’s got a problem, you’d want to steer away from it. As far as anything else, you can look it up. I have a high regard for the people that handle the hose, that are around the horse. So they know if it’s a nervous horse or a horse that’s a little more mentally mature. To be honest with you, I value everybody’s opinion, and then you just have to draw your own conclusion.

Brendan Walsh

I think you’ve got to have your opinion on them. I have people I work with, obviously, or if you’re looking for a client, you have to take their opinions on board, too. I mean they do influence you depending on the circumstances, but at the end of the day you have to have your own opinion.

Al Stall

A lot of people have teams, including myself. If it’s a team member, I’m all ears. Otherwise, I don’t really pay too much attention. We’ve been doing it a long time. We end up agreeing most of the time, and if we don’t agree we just throw it out and move on to the next. It’s us three, me and Frank and Daphne Wooten from Camden, South Carolina. They break our yearlings. We’ve been doing it together for quite a while. We’ve gotten lucky. Lucky is a very important word with yearlings.

Mike Stidham

We have certain people we work with, a team of about five of us. We’ve been going to Keeneland for 30 years or more and we’ve had some success there with the budget we have to spend. We’re pretty pleased with what we’ve accomplished over the years, so the opinion of others really doesn’t come into play.

Mark Hennig

If I don’t like the yearling, I don’t buy it. But there’s been times where I like the yearling and someone might point something out to me that makes me take a closer look and veer away from it. We’re always capable of having a second set of eyes or a third set of eyes. I rarely look at a horse by myself. We usually have a team, an agent, my wife and I. In some cases an owner wants to look at them, too. We do miss things.

A Look at Learning Theory for Reducing Stress and Developing Top Performers

Who doesn’t want to produce a performance athlete who is less stressed, experiences fewer setbacks and enjoys improved welfare? It has been shown that correct application of learning theory principles, starting from a young age, can clear the track.

Learning theory explains how each horse acquires, processes, and remembers the knowledge they need to perform as a racehorse. For handlers this means developing a deep understanding of how a horse learns. Naturally gifted horsepersons are already employing some of the principles, often without even knowing it, with their impeccable timing of cues.

In the past two decades, both social licence to operate and equine welfare have come to the forefront. Failing to grasp how the horse’s brain works (both their capabilities and limitations) can lead to confusion, unnecessary stress, and dangerous behaviors. Conversely, understanding equine learning theory can streamline training, lessen the chances of injury to both horse and handler and improve efficiency in training.

How Foal NZ is Using Learning Theory for the Win

Globally recognized for their success training thoroughbred foals, Foal NZ has been achieving remarkable results in New Zealand. Through utilizing learning theory they have completed over 35,000 training sessions without injury for the past two decades. Yearlings fetching million-dollar price tags and Group One race champions such as So You Think, Military Move and Jimmy Choux emerged from the program, earning acclaim in Thoroughbred racing circles.

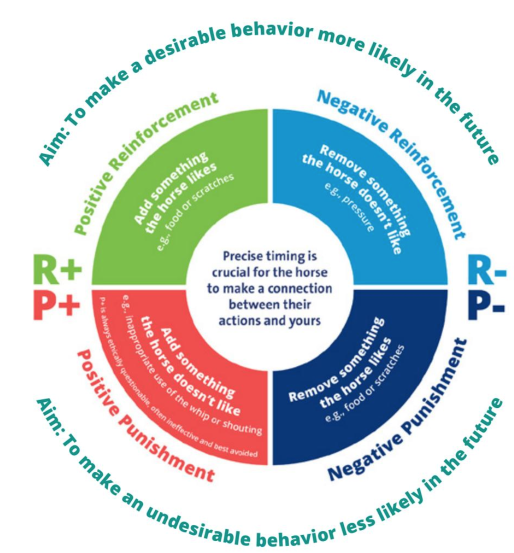

Learning theory is a way of explaining the different types of training typically used with horses and contains four main quadrants that explain how consequence is used to shape behavior. Sally King of Foal NZ explains how they use learning theory to create confident, capable young athletes.

The Foal NZ team use primarily positive and negative reinforcement to encourage the foals to learn the desired behavior while becoming confident in both their ability to learn and their relationships with people. Using negative reinforcement (removing a cue the horse doesn’t enjoy as soon as the horse responds), the handler will ask the foal to move forward using pressure from a rope around the foal’s rump, releasing the pressure as the foal moves the first foot off the ground.

Once the foal is confident about being touched by people, then they will start to include positive reinforcement (doing something the horse likes) by offering the foal neck scratches once a desired behavior is performed. “This encourages the foal to try to find the solution to what we are asking as they feel relaxed and confident in their abilities – the perfect mental state for accelerated learning,” says King.

Positive punishment (adding something the horse does not like such as vocal or physical reprimand) is less effective than other methods. An example of positive punishment is when a horse rears and ‘shanking’ the horse’s face is employed to punish them. While this may work temporarily as the horse attempts to avoid pain, numerous studies in children have shown that using positive punishment creates anxiety and fear and reduces brain function. Likewise, if the horse is afraid, they are hindered from using their brain to find solutions. Handlers that can recognise stress from facial expressions, muscle tension, and behaviours can pre-empt the rear by changing the situation to reduce tension.

Negative punishment (taking something away that the horse enjoys or values) is generally not recommended as this may cause stress and increase anxiety.

Desensitizing and flooding are two learning concepts that have also been used in training. Desensitizing involves gradually getting the horse accustomed to something, while flooding entails exposing the horse to a frightening stimulus in an intense and unavoidable manner. For instance, a young horse may spook or hesitate at a particular part of the track during their morning workout due to something new or unusual appearing in that area.

If a colt spooks and stops, and the handler was to tie them or hold them so they were forced to stay near what was frightening them, this would be called flooding. Eventually the horse would stop showing the fear behaviours but only because they have learned that nothing they do will make the scary object go away. It is not because the horse now feels comfortable in that area. Flooding can have a compounding effect called ‘trigger stacking’. Initially, the horse may suppress signs of fear, but as stress accumulates and the threshold is crossed, it can lead to sudden, intense reactions or behavioral outbursts.

In contrast, desensitization could involve putting more distance between the horse and the ‘scary’ area at first. They may pass that area alongside another horse to gradually increase comfort with that part of the track, enabling pace to be maintained in future laps. A jockey that can sense his mount starting to hesitate or veer away can use their powers of prediction to desensitize and foster confidence rather than risk escalating stress.

Another well-applied example of learning theory is how trainers typically ‘shape’ responses when introducing horses to the starting gates. Trainers typically break down the elements of being able to use starting gates successfully into multiple parts, gradually going from walking past the gates to walking through open gates following a lead horse, to being beside the lead horse, to stopping inside the open gates, to stopping with one gate closed, then two, then waiting inside, then breaking at a walk and subsequently faster gaits. This way of training called ‘shaping’ also considers the horses ethology in understanding that they are social, prey animals and can feel uncomfortable being restricted in small spaces.

Timing and consistency are arguably the most important tenets of effective training; if the horse can predict what the handler or rider wants and knows they will consistently ask for the behavior in the same way each time, they are much more likely to perform successfully and confidently.

Effective training relies on the simple relationship between the cue, the response and the reinforcement and being able to read stress levels. “In the bloodstock industry, young horses are more likely to be exposed to a wider range of handlers and environments than sport horses but will typically have to perform a smaller range of behaviors than a sport horse,” says King. Thorough training of cues and responses will set the horse up for future success when a wide range of handlers, with varying experience ask the horses to perform behaviours during varying states of arousal.

Using a training system that uses clear principles of learning and lessens the occurrence of conflict behavior, avoidance and escape behaviors has positive outcomes for both horse and human safety and welfare. A young horse that has been trained this way will be more compliant, better able to cope with environmental and social changes and consequently safer. Not only that, but they will feel like they can predict their world, succeed at their job and have some sense of control over what happens to them – all things that increase self-confidence and thus optimize performance.

Within a busy yard, there are time pressures often resulting in limited time to achieve results. Using clear and consistent approaches based on learning theory results in quicker and more robust training, more efficient use of staff time and therefore increased productivity; and for most organizations, improved commercial viability.

Study on Humans Reading Equine Behaviour

This brings us to the next question – How well can you tell? Can a wide range of horse handlers accurately gauge a horse’s behavior as positive, neutral or negative? Dr. Katrina Merkies, a professor in the Department of Animal Biosciences at the Ontario Agricultural College has collaborated on numerous horse behaviour studies and recently published a paper on this very topic.

As it turns out, most of us might not be as perceptive as we think. Merkies’ recent study explored how accurately people can interpret horse-human interactions by looking at photos and watching videos. On average, participants correctly identified whether a situation was positive, negative or neutral only about 52% of the time, which is barely better than chance.

To establish a benchmark, the researchers first had equine behavior specialists evaluate the same media. Their assessments were treated as the gold standard. When the study participants viewed these clips, their interpretations often missed the mark—unless the emotional cues were especially obvious. For instance, people were more likely to recognize a negative scenario when a horse clearly refused to walk across a tarp, or a positive one when a foal willingly approached a person for attention.

These results raise important questions about how well we understand the emotional lives of animals, and how that understanding—or lack thereof—can impact their welfare and how we approach training.

Subtle Signs

While people were somewhat successful at identifying obvious emotional cues in horses, the study revealed a significant gap in recognizing more subtle indicators. According to Dr. Merkies, many of these nuanced signals are found in the horse’s facial expressions. Participants often reported focusing on the horse’s face to gauge their emotional state but frequently overlooked finer details.

Some of the key subtle cues included the direction of the horse’s ears, tension lines around the eyes, and the flaring of nostrils. These small but telling signs can reveal a lot about how a horse is feeling—whether they are anxious, curious, or relaxed. Unfortunately, these indicators are not always easy to spot, especially for those without specialized training in equine behavior.

Improving our ability to recognize these subtle cues could raise the bar for increasing positive human-animal interactions and improving the chances of early intervention at the first sign of physical issues.

Does Self-Awareness Help Us Understand Horses?

One of the central questions of the study was whether people who are more in tune with their own bodily sensations—such as heartbeat, breathing, or muscle tension—are also better at interpreting the emotional states of horses. This idea stems from human psychology research, which shows that individuals with greater internal awareness, or interoception, tend to be more empathetic toward others.

To explore this in the context of human-horse interactions, the researchers used a validated tool called the Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA-2). This questionnaire measures how aware people are of their internal bodily states across eight dimensions, including emotional awareness, attention regulation, and body listening. Participants rated themselves on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much) for each item.

Participants were asked to evaluate the various horse-human interaction clips before the MAIA-2 results were recorded to avoid skewing the results. Surprisingly, the results showed no significant correlation between a person’s interoceptive awareness and their ability to accurately assess the horse’s emotional state.

This unexpected outcome raises several possibilities. It could mean that interoceptive awareness simply doesn’t translate across species, or that the MAIA-2 isn’t the right tool for this kind of cross-species empathy. Another possibility is that the participants—many of whom were highly experienced with horses—relied more on their practical knowledge than on emotional intuition when evaluating the clips.

Learning to See What Horses Are Telling Us

The study highlights a clear need for improvement in how people perceive and interpret subtle equine behaviors. So how can we get better at this? According to Dr. Merkies, education is the obvious starting point—but it’s not the whole solution. “We can learn about these cues,” Merkies explains, “but being able to apply that knowledge in real-life situations is a different challenge.”

One promising approach is the use of tools like the Horse Grimace Scale which can help observers assess facial expressions and other subtle signs of discomfort. These tools are gaining traction in professional settings; for example, the Hamilton Mounted Police unit uses facial grimace scoring as part of their daily horse care routine. Incorporating such practices into everyday horse management can train people to notice and interpret the finer details of equine behavior.

Dr. Merkies emphasizes the importance of shifting our perspective: “We need to stop, listen, and pay attention—not from an anthropomorphic viewpoint, but by trying to understand how the horse is experiencing the situation.” This means resisting the urge to project human emotions onto horses and instead learning to see the world through their eyes.

Challenging Industry Norms

Another barrier to better understanding horses is the normalization of certain behaviors within the equine industry. “There are a lot of myths that get passed down and accepted as just the way things are,” says Dr. Merkies. Take, for example, a horse pinning their ears when the girth is tightened. This is often dismissed as the horse being a grouch or even 'normal' behaviour for that horse, but this mindset can prevent us from asking deeper questions: Why is the horse reacting this way? What are they trying to communicate? Is there a physical reason for this reaction.

Another great example of negative feedback, often ignored or normalized, is a horse that displays discomfort while being groomed by constant fidgeting, head tossing or grimacing. Again, the discomfort should be acknowledged and addressed, perhaps with softer brushes or counter-condition using positive reinforcement. Is there a physical issue that requires veterinary intervention?

By challenging long-held assumptions and encouraging critical thinking, the equine community can move toward more benevolent and informed interactions with horses.

Positive Reinforcement - Building Better Bonds

One of the most promising ways to improve horse training and welfare is through the use of positive reinforcement—a method that rewards desired behaviors to encourage their repetition. Dr. Merkies emphasizes that this approach not only works but often leads to better outcomes than traditional methods that rely on punishment or pressure.

Despite its effectiveness, positive reinforcement is sometimes misunderstood. Common myths suggest it might make horses ‘mouthy’ or lead to weight gain from treat overuse. Others argue it’s unnecessary because a horse should obey out of affection or loyalty. These misconceptions can discourage people from adopting more compassionate and effective training techniques.

Positive reinforcement doesn’t have to be complicated—or even food-based. While treats are a common and convenient reward, other reinforcers can include scratches, companionship, or access to a favorite location. The key is understanding what motivates your individual horse.

Dr. Merkies offers a simple but powerful example: “When you go to halter your horse, do they come to you, ignore you, or turn away?” These responses are forms of feedback. Even subtle behaviors—like a horse turning its head slightly away when approached—can signal discomfort or reluctance.

Recognizing and responding to these cues can transform training into a more cooperative and enjoyable experience for both horse and handler.

Ultimately, positive reinforcement fosters a relationship built on trust and mutual respect. “It’s super satisfying,” says Dr. Merkies, “when they come running up to the gate or whinny from the field. Then I know they’re looking forward to the training session.”

The benefits of a horse experiencing more positive interactions with humans than negative ones are obvious from a welfare and safety standpoint. When a horse is repeatedly exposed to negative interactions with humans, they may develop fear or resistance, which can make handling more challenging and increase the risk of injury for both the horse and the handler. If you are looking for ways to use more carrot and less stick to reduce stress and setbacks, consider applying the principles of learning theory to your horse training program.

2025 Gerald Leigh Memorial lectures where we learn about the latest research in laryngeal surgeries and tendon rehabilitation

The seventh renewal of the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, in association with Beaufort Cottage Educational Trust took place at Tattersalls in Newmarket, England on June 4th.

The Gerald Leigh Charitable Trust was established in 1974, set up in memory of Gerald Leigh, a prominent owner breeder and best known for breeding the highly successful Barathea and Markofdistinction.

His legacy lives on through the trust, which not only reflects his remarkable achievements and lasting influence in the world of Thoroughbred breeding and racing, but also continues his deep passion for scientific advancement and the welfare of horses—both within the racing industry and the wider equine community. The trust stands as a testament to Gerald Leigh’s enduring commitment to excellence, care, and innovation in all aspects of equine life.

Wind ops- the decision making and diagnostics

Tim Barnett MRCVS of Rossdales Veterinary Surgeons, delivered two informative and interesting lectures on wind ops and the decision making and diagnostics relating to them. As we all know, wind surgery addresses upper airway conditions in horses that impair breathing and performance. Key anatomical structures involved include the arytenoid cartilage, vocal folds, epiglottis, and soft palate. Common issues include vocal fold collapse, often causing a whistling noise and linked to progressive recurrent laryngeal neuropathy “roaring”, which severely obstructs airflow. Another frequent problem is dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP), where the soft palate flips over the epiglottis, blocking airflow and causing sudden loss of performance.

Palatal instability often precedes DDSP. Other conditions include medial deviation of the aryepiglottic folds, nasopharyngeal collapse, epiglottic entrapment, and ventral luxation of the arytenoid apex (VLAC). These disorders vary in severity and may be progressive or multifactorial. Barnett clarifies that although surgical interventions target these conditions, outcomes depend on the specific disorder and severity.

Upper airway conditions remain a major cause of poor performance in racehorses, with many requiring multiple surgical interventions. Accurate diagnosis, particularly via exercising endoscopy, is key, as many disorders only become apparent during physical exercise.

Tieback (prosthetic laryngoplasty) is the most common wind surgery but carries risks such as aspiration, pneumonia and swallowing dysfunction, despite efforts to improve surgical techniques. Newer techniques, like standing tiebacks and improved implants (e.g., titanium buttons, reinforced screws), aim to reduce complications and enhance results.

Other surgeries like Hobday (vocal fold removal via laser) were also discussed, emphasizing the delicate nature of airway surgeries and the ongoing challenge to balance treatment effectiveness against risks and complications in our racehorses.

For DDSP, tie-forward surgery, which mimics natural muscle action to restore laryngeal position, has shown positive results, while thermocautery remains controversial. Epiglottic entrapment can now be safely corrected in standing horses using lasers or scissors. Emerging therapies include laryngeal reinnervation and dynamic neuroprosthesis to restore muscle function, as well as vocal fold filling to reduce aspiration pressure.

Collagen cross-linking is also under investigation as a less invasive method for soft palate stiffening. Barnett concludes, precise diagnosis and tailored interventions are crucial for optimal results in treating upper airway disorders in racehorses. These advances reflect a growing push for safer, more effective airway interventions in the racehorse.

Barnett then moved onto discussing the critical role of exercise endoscopy in diagnosing upper airway dysfunction in Thoroughbreds, highlighting the limitations of resting endoscopy. While useful for detecting conditions like total RLN, epiglottic entrapment, or arytenoid chondritis, resting scopes often miss dynamic issues such as soft palate disorders and vocal fold collapse.

Recent developments in overground endoscopy which are battery-powered and rider-compatible, allow evaluation during real time exercise, providing accurate and practical diagnosis. This method has become the preferred standard, especially for assessing palatal instability and early RLN.

Clinical signs such as respiratory noise, poor performance, or sudden stops may indicate airway dysfunction, but accurate diagnosis requires proper exercise testing with horses cantering or galloping while synchronizing breaths per stride. Additional tools like laryngeal ultrasonography aid diagnosis and planning of treatment.

Barnett cautioned against performing airway surgery without thorough diagnostics, as multiple simultaneous conditions can exist, and treatments must be carefully targeted to improve outcomes. Around 25% of Thoroughbreds show clinical RLN, reinforcing the need for tailored, evidence-based treatment plans to support both welfare and performance.

Laryngeal surgeries - the evolution of research and engineering of the tie back and nerve graft

Dr Fabrice Rossignol, of Grosbois/Chantilly Equine Clinic discussed laryngeal surgeries, focussing on the evolution of research and engineering of the tie back and nerve graft. Rossignol’s specialist clinic is at the forefront of treating recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN).

The condition is often linked to degeneration of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, affecting the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis (CAD) muscle, which is critical for opening the airway during exercise. Rossignol explains that this muscle contains few fatigue-resistant fibers, making it vulnerable to atrophy. Even minor narrowing of the airway significantly increases resistance, due to the exponential pressure effects described by Poiseuille’s law.

Diagnosis involves treadmill endoscopy and ultrasonography (caudal view of swallowing can be particularly useful) to assess dynamic airway collapse and muscle atrophy. Treatment is tailored to severity; advanced cases may require a tieback (laryngoplasty) using synthetic prostheses to partially open the arytenoid cartilage, though this risks complications like coughing. Newer techniques aim to restore function rather than replace it. One such innovation combines traditional tieback surgery with nerve grafting from the spinal accessory nerve, which activates during inspiration and contains fatigue-resistant fibers.

This hybrid approach improves airway opening and reduces side effects. Standing surgery under sedation allows more precise suture placement, minimizing anesthetic risk. Emerging technologies like 3D-printed implants and titanium screw anchors further enhance outcomes. Rossignol echoes Barnett’s earlier advice, that early intervention and careful case selection remain key to success.

Dr Rossignol continued on to discuss what and how we, as a racing industry, can learn from other disciplines.

Recent research in trotters and sport horses highlights how neck flexion contributes to dorsal and lateral pharyngeal collapse, likely due to nerve inflammation affecting muscles such as the stylopharyngeus. Nasal obstruction, including alar fold collapse and nasal muscle paralysis, also play a role in compromised airflow. Treatment options now include alar fold resection, nasal fenestration (widening), and innovative approaches like titanium mesh implants to replace lost muscular function.

Dr Rossignol explains that high-speed treadmill testing has proven critical in diagnosing dynamic airway conditions, while a multidisciplinary approach involving vets, trainers and farriers enhances management strategies. Use of nasal dilation devices, such as nasal strips, remains restricted under many jurisdictions' rules of racing.

It is clear that Rossignol champions cross-disciplinary learning, working with trotter trainers over decades has yielded practical insights, such as shoe removal to enhance performance. The methodical, detail-driven tack and equipment adjustments made in trotting disciplines provide valuable lessons in optimizing performance.

Dr Rossignol also shares advances in surgical techniques, including refined approaches to epiglottic entrapment, emphasizing the importance of collaborative care. Cross-disciplinary exchange continues to inform diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation, enriching equine sports medicine and improving outcomes across disciplines.

An update on wind surgeries: what's new?

To conclude the lectures on wind ops, Mark Johnston, Dr Rossignol and Tim Barnett took to the floor to field audience questions. The discussion focused on recurrent laryngeal hemiplegia (RLN) in horses, highlighting its probable hereditary component but unclear linking between particular genes. Experts note the complexity of breeding influences and caution against oversimplifying genetic causes, as RLN will most likely be linked with other traits.

Surgery helps individual horses but may skew breeding populations, as generally only the more expensive stallions receive treatment. Disclosure of surgeries before breeding is debated but difficult to enforce. Non-surgical solutions like resistance masks are emerging but their impact on reducing surgery isn’t yet clear. Overall, understanding and managing RLN’s genetics and treatment remain challenging and unresolved.

Early diagnosis of recurrent RLN relies on ultrasonography to detect early muscle atrophy; surgery is recommended promptly to prevent irreversible damage. In contrast, dorsal displacement of the soft palate (DDSP) often stems from muscle fatigue, immaturity, or inflammation and is best treated medically with training and reinforcement until at least three years old. Surgery is a last resort if medical management fails.

Multiple surgeries can be ethical if done safely and explained clearly. Yearling wind testing is variable and challenging to interpret, complicating sales disclosures. The increase in buyers scoping foals’ pre-sale is seen as an invaluable and unpleasant practice due to solid evidence that a foal’s laryngeal physiology will and can change tremendously as they mature. Ongoing research explores novel therapies such as pacemakers and magnetic stimulation.

The practical management of tendon rehabilitation

There is no introduction needed for Mark Johnston, who kindly provided us with his insight on the practical management of tendon rehabilitation. A renowned trainer with decades of experience offered a pragmatic view on tendon injury rehabilitation in racehorses, challenging long-held optimism around recovery. Despite advancements in ultrasound imaging and a range of therapies, from anti-inflammatories to experimental interventions like carbon fiber implants, he is yet to witness a truly successful long-term return to peak performance in top-level racing following a diagnosed tendon injury.

While ultrasound provides valuable detail, he still relies most on visual and tactile assessment, particularly tendon profile and signs of ‘bowing,’ which he considers a critical turning point. In his experience, few flat horses make a full comeback; many may race again, but recurrent issues and shortened careers are the norm. Mark’s approach is rooted in realism: throw everything anti-inflammatory at the injury early, manage workload carefully, and temper expectations.

Long rest alone is rarely effective and controlled rehab and early, aggressive treatment are key. He notes that previous use of prophylactic anti-inflammatories post-race helped reduce injuries, and questions whether restrictions on racecourse treatments may hinder progress. Prevention, early detection, and practical management remain the trainer’s most reliable tools.

Tendon injuries in racehorses

Professor Roger K.W. Smith FRCVS presented a detailed lecture on tendon injuries in racehorses, focusing on the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and the role of science in improving prevention and rehabilitation strategies. As a key structure for locomotion, the SDFT functions as an energy-storing spring but operates near its mechanical limits, especially in Thoroughbreds, making it prone to injury from accumulated loading rather than acute trauma.

Research shows that degeneration often precedes clinical injury, particularly within the interfascicular matrix (IFM), which loses elasticity with age and training. Tendon cells also become less responsive with age, impairing repair. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are implicated in post-exercise matrix degradation, further weakening the tendon.

Professor Smith emphasized prevention through training adjustments: avoiding hard ground, spacing out intense work, and ensuring sufficient recovery of, ideally 72 hours. Early detection is critical. Diagnostic tools such as ultrasound, Doppler, and Ultrasound Tissue Characterization (UTC) can identify structural changes before injury becomes apparent.

When injury occurs, a prolonged, structured rehabilitation program guided by regular imaging is essential. Biologic therapies like mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are showing encouraging results, improving tendon structure and reducing re-injury rates. A personalized, biologically informed approach remains key to safeguarding tendon health in racehorses.

Tendinopathy - its causes, treatments and parallels between equine and human medicine

Lt. Col. Dr Tom Clack delivered a comprehensive lecture on tendinopathy, highlighting its causes, treatments, and parallels between equine and human medicine. Tendinopathy, a chronic overuse injury, follows a three-stage progression: reactive tendinopathy (early inflammation), tendon disrepair (structural change and neovascularization), and degenerative tendinopathy (reduced symptoms but increased rupture risk).

Historically, eccentric loading exercises, which came about via human Achilles research, became the core treatment. Today, management is more tailored, focusing on biomechanics, load control, and personalized rehabilitation.

Diagnosis includes clinical evaluation and ultrasound, with advanced modalities like Shearwave elastography and UTC offering deeper insights into tendon integrity and healing.

Dr Clack advocated a multimodal treatment strategy: progressive loading, extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT), and injectables such as corticosteroids (for short-term relief) and PRP, which supports healing through growth factors.

Crucially, he emphasised the value of Thoroughbred racehorses as models for human tendon injury. Their tendons endure similar high loads, and developments in imaging, PRP, and regenerative therapies in equine medicine are increasingly influencing human sports injury treatment.

Dr Clack echoed the importance of early detection, strategic recovery protocols, and ongoing collaboration between human and veterinary medicine to improve long-term outcomes in equine athletes.

Rehabilitating the equine athlete

We were then treated to a lecture by Veterinary surgeon Amelia MacArthur, who provided a grounded and insightful view on equine rehabilitation, shaped by her hands-on experience running a specialist rehabilitation yard in North Yorkshire, England. Based at the former training yard of the Cheltenham Gold Cup winning trainer, Peter Beaumont, her facility includes a water treadmill, deep sand gallop, extensive hacking, and a quiet stable environment, all tailored to support recovery and performance conditioning.

It is clear that MacArthur advocates for a genuinely holistic approach, not rooted in fads, but in understanding the whole horse: injury history, temperament, conformation, previous management, and future athletic goals. Rehabilitation begins with controlled exercise, which is often hand-walking, though she acknowledges the safety challenges of managing fresh horses, advising use of protective gear and sedation when necessary. In-stable physiotherapy, such as weight-shifts and limb lifts, can supplement or replace walking early on.

She stresses that rehabilitation literature often lacks clarity, so individualized programs with regular reassessment, particularly ultrasound checks, are essential. Progressive loading, surface variation, and adapting treadmill use depending on injury type all help prevent reinjury. For tendon cases, treadmill work is delayed to avoid strain from reduced slip.

Crucially, MacArthur highlighted the impact of rider weight and balance, particularly for ex-racehorses, and the importance of body condition in supporting soundness. A striking case study showed how fat loss transformed a Highland pony’s tendon recovery and competitive ability.

Tendon injury; therapy and management

The final open floor discussion of the day took place between Mark Johnston, Professor Roger Smith, Dr Tom Clack and Amelia MacArthur. The topic of military-style training programs running parallel with equine management were discussed, particularly in managing overuse injuries like stress fractures. Key strategies include load management and gradual conditioning over 4–8 week cycles. It was noted that today’s horses, like modern human recruits, can often lack natural conditioning, especially in the feet, increasing injury risk.

Prevention is focused on structured training that supports both tendon and bone development, particularly in young horses (yearlings), where tendons must adapt before bones are heavily loaded. Ground conditions and surface variation also play a complex role in musculoskeletal health.

Rehabilitation and pre-training approaches remain debated, but there's agreement that progressive, controlled exercise is essential. Tendon injuries, especially in flat racehorses, are notoriously hard to overcome. Advances in ultrasound and imaging, such as UTC and shockwave elastography offer new promise, though they come with high costs and technical demands.

Steeplechase horses often return to competition successfully after injury, offering hope, but managing owner expectations remains key. Medication use, such as dexamethasone, is tightly regulated on racecourses to uphold integrity. Like elite human athletes, horses need carefully balanced workloads and rest to prevent chronic damage. While rehabilitation methods are improving, prevention remains the best strategy.

This year’s renewal of the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures was once again full to the brim with exciting new research and innovative thoughts from world leading experts. Attendees, all involved within various areas of the horseracing industry made for diverse and thought-provoking discussions.

The commonality amongst the lecturers and attendees alike was the undeniable commitment to ensuring the betterment of equine welfare in all avenues of bloodstock, racing and life after. Safe to say, all who attended are already looking forward to the 2026 lectures.

Tangible improvements to equine safety and welfare to reduce the prevalence of both EASD incidents and severe musculoskeletal conditions

In racehorses, exercise-associated sudden death – or EASD – is a very rare event but it can happen and this article is written to highlight a need for better understanding of why it happens as well as motivating vets, researchers and horsemen to do more to prevent it.

In June 2024, Woodbine Racecourse, Toronto hosted the International Horseracing Federation’s (IFHA) Global Summit on Equine Safety and Technology where EASD was one of two major workshop topics. This international event was sponsored by Cornell University’s Harry M. Zweig Memorial Fund for Equine Research, The Hong Kong Jockey Club Equine Welfare Research Foundation, and Woodbine Entertainment Group and specialist veterinary clinicians, pathologists and researchers spent two days sharing knowledge and ideas and debating how tangible improvements to equine safety and welfare in racing could be made towards reducing the prevalence of both EASD incidents and severe musculoskeletal conditions.

What is EASD?

The term EASD is used to describe a fatal collapse in a previously healthy horse, either during or shortly after exercise. Currently, across the world, different time-windows are used by regulators which makes quantification of the problem challenging. A benchmark definition is needed so that the occurrence rates can be audited and the EASD workshop team advised that an international definition be adopted to define EASD as within approximately one hour after exercise. Figures from the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) show that in Great Britain , the 2024 EASD incident rate was 0.04% or 4 horses per 10,000 starts. The British rate is comparable with other nations such as Australia and a little lower than the USA although the different definitions used in different racing jurisdictions make direct comparisons challenging.

Four broad EASD categories

The most authoritative international study looking at causes of EASD was performed with the British Horserace Betting Levy Board supported by a group in the University of Edinburgh’s Royal Dick School of Veterinary Studies. This report showed that determination of cause of death is significantly impacted by individual pathologist’s interpretation of findings, however, in broad terms about a quarter of cases EASD have a clear and definitive diagnosis of cardiopulmonary failure and a further 10-15% have necropsy findings which are strongly suspicious of cardiac or pulmonary failure; around 10% of EASD cases are due hemorrhagic shock brought on by rupture of a major blood vessel which is most commonly within the abdomen, while unfortunately around 20% of cases are unexplained despite detailed examination. A range of other rare conditions including brain and spinal problems, often relating to trauma, account for the remainder.

Within the cardiopulmonary failure category, it is generally accepted that the majority relate to cardiac arrest. This means that the cardiac rhythm is disrupted but, in fact it is actually very difficult to prove that a cardiac rhythm disturbance has been the trigger mechanism of death during a post-mortem examination. In the June 2024 IFHA summit, a significant amount of the workshop was dedicated to discussing current knowledge of cardiac rhythm disturbances, why they occur and how they might be detected in the future.

Cardiac arrest: a “perfect storm”

Cardiac arrest can be likened to a perfect storm where multiple adverse factors combine with devastating impact. Unlike catastrophic bone fractures or tendon injuries, cardiac arrest does not necessarily relate to an accumulating pathway of built-up microdamage and because of this, it is very difficult to predict cardiac arrest might occur. For a cardiac rhythm disturbance (aka an arrhythmia) to develop three elements are required: a substrate, triggers and, in some cases, one or more modulators. A substrate refers to the structure of the heart, this can be an area of scar tissue but the heart structure does not necessarily need to be pathological and the changes in muscle content which arise as a result of athletic training may also be a substrate.

A trigger reflects a change in the cellular and tissue environment such as alteration in concentrations of different electrolytes or development of low oxygen concentrations in the tissues yet changes in electrolytes and lowering oxygen concentrations occur every time a horse gallops. Modulators are an electrophysiological characteristic of the heart which might be a permanent feature of an individual’s cell make-up or more often might be a transient state such as a variation in the nervous system brought on by excitement, stress or perhaps pain.

The key point is all these independent factors have to combine to precipitate a cardiac arrest – indeed a horse might go through its life uneventfully despite the presence of a particular substrate or it may experience these triggers on a daily basis and come to no harm. It is the coalescing of multiple factors at a given moment that precipitates the rhythm disturbance that leads to cardiac arrest.

EASD at the molecular level

Arguably the biggest challenge we currently face in this arena is lack of knowledge of what is normal in the exercising horse. There is very little understanding of structural and electrical remodelling of the equine heart in response to exercise. We do know that the heart, just like any other muscle, will increase in size in response to training and we also know that in horses competing over longer distances such as steeplechasers, a big heart confers an athletic advantage. Exercise training can also lead to scar-tissue formation but in both human and equine athletes the importance of this pathology is uncertain. There is some evidence that fit horses also have altered cardiac electrical characteristics but again, knowledge in this field is very sparse.

Electrical activity in the heart muscle cells is controlled by ion channels – these are proteins that are sited within the cell membranes which effectively act as gates opening and closing to allow electrolytes such as sodium, potassium and calcium to move in and out of the cell and in doing so the electrolytes carry the electrical current.

Channelopathies – or abnormalities in these ion channels - have an important role in the development of rhythm disturbances but right now, research on equine ion channels has been limited…but that is changing rapidly. Researchers in Great Britain, Copenhagen and various US universities are working to understand equine channels and the genetic and acquired factors that determine how they function. As knowledge accumulates it may be possible to include tests for the molecular make -up of an affected individual in post-mortem exams – the so-called “molecular autopsy” which is improving diagnosis rates in human cardiac arrest suffers.

So far equine studies have not found conclusive evidence of genetic mutations associated with EASD. But there is evidence for heritability in the Thoroughbred: observations from Australia which have shown some stallions’ and at least one mare’s progeny have higher rates of EASD associations suggesting that it is likely that there are genetic elements at play in EASD. One of the key recommendations of the IFHA’s EASD workshop was that tissues from both horses impacted by EASD and those dying of other causes should be banked and shared amongst researchers to underpin and promote research studies in this area.

ECG is the cornerstone of arrhythmia diagnosis

Currently vets rely on resting and exercising electrocardiograms (ECG’s) to identify horses with arrhythmias. However, there are a number of limitations to using ECG as a screening and diagnostic tool:

ECGs can be technically difficult to perform during exercise as they are affected by motion artefact; leading to reduced quality of the trace.

ECGs currently must be manually interpreted, which is time consuming and leads to significant intra- and inter-observer variability.

There are no universal guidelines on how to perform the ECG; i.e. exactly where to place the electrodes, which affects the trace produced.

There is no consensus on interpretation of the results of an ECG examination in terms of the clinical significance of any abnormalities detected and whether the clinical presentation impacts criteria for interpretation. Indeed, we need to understand more about what is ‘normal’, before we can identify horses with an ‘abnormal’ trace.

Will wearables change the diagnostic landscape?

Over recent years, increasingly racehorse trainers have been using wearable devices during routine training. Generally, the trainer’s motivation is to collect data on speed and fitness variables in their horses to refine their training programs but several of these devices also have the capacity to include an ECG trace. The ECG can then be accessed if the horse has a problem during a training session and, usefully, the horse’s past record can also often be interrogated. The large numbers of recordings that are currently being made represents an untapped resource for collecting ECG information from large numbers of horses to better understand cardiac responses during exercise in both healthy and unhealthy individuals.

It has been known for some time that healthy horses frequently have mild rhythm irregularities – generally described as premature complexes or premature depolarizations – these minor fluctuations in rhythm occur at all phases of exercise and particularly as their heart rate is slowing rapidly at the end of a gallop. But the dividing line between what is normal variation and what is clinically concerning is not clear-cut. We do not know exactly how much beat-to-beat variation can be classed as normal versus a sign of significant arrhythmia and we have little understanding of the relationship between premature depolarizations and other factors such as stress, exercise intensity, medical interventions and adverse clinical events.

As a result, veterinary clinicians are looking forward to the ongoing expansion of wearables as an exciting new window into equine cardiac function. Yet, the scale of the unexplored data collection currently going on in training brings with it a challenge – with so many ECG traces being rapidly collected, how can we address the mammoth task of actually looking at them? Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing many aspects of modern life, including medical diagnosis. There is an urgent need to develop AI systems which can screen training ECGs to identify those that warrant further attention. And, although a large number of wearable devices are available on the commercial market, these products often lack validation which is needed before we can use the data they collect to make clinical decisions on individual animals and use the data as a research resource.

Could we deal with EASD cases better when they do occur?

Racetrack arrhythmia/collapse are, in reality, low probability but high impact events which can be difficult to manage due to their traumatic nature and the fact that they are often played out in the public eye. This is compounded by the availability of medical equipment and limited treatment options that may be futile.

However, when these events do unfortunately occur, they represent a golden opportunity to collect diagnostic information and biological samples which could be used to prevent future EASD events in other horses in the future. The combination of an ECG history, a video of the horse as it suffers the event, information from necropsy if the horse dies, and tissue banking offers valuable research insights.

The nearest parallel event from human sport is the cardiac arrests which are occasionally seen in footballers. Through the effort of football’s regulators, today pitch-side emergency medical facilities are excellent and large numbers of trained staff are in attendance, all leading to the best possible outcomes for sportsmen when medical problems arise. When looking to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation and treatment attempts in the collapsed horse, the animals’ size is a major challenge; human defibrillators simply do not work in large animals.

We need more information on emergency medications that can be used in the presence of arrhythmias of unknown origin. These drugs need to be quick to administer, available and suitable to be carried by a racecourse vet, safe, effective and affordable. The IFHA’s EASD group identified that in pressurized situations, pre-determined protocol approaches to both emergency treatment and necropsy procedures are invaluable and the group is working to develop these protocols for dissemination across racing jurisdictions.

Will EASD risk always be present?

As EASD is such a rare event, it is impossible to believe that the risk of EASD can ever be removed entirely, but given the recent technological development in both veterinary science and wearables for training, there is reason to be optimistic that in the coming years, we will at last be able to improve diagnosis rates, identify some of the contributing risk factors and even potentially provide more effective emergency treatment options for these unusual but tragic episodes in our horses.

Gabriel “Spider” and Aisling Duignan with Echo Sound

An owner’s thrill winning a graded stakes is even greater when that horse is a home-bred. And if there’s a special bond between horse and owner, so much the better.

Gabriel “Spider” Duignan, who usually doesn’t keep the fillies and colts he breeds, knows that feeling. When Echo Sound, a daughter by Echo Town out of Eagle Sound by Fusaichi Pegasus, who was co-bred by Vision TBs and Bruce and Patricia Pieratt, captured the Gr.3 Miss Preakness Stakes at Pimlico May 16th, Duignan and his wife Aisling had completed a personal vow.

“What makes her special was her mother was very special to us and very good to us and a great producer,” Duignan said. “I think she was the first mare we bought together. She was getting older, and she hemorrhaged and died shortly after birth, a couple hours after giving birth. That’s never nice to watch, but it happens. That was her first filly. She’s a home-bred. From that standpoint, it makes her a little special. We vowed that we’d keep Echo Sound.”

They’ve never regretted that decision.

Echo Sound was born on the Duignan’s 300-acre Springhouse Farm near Lexington, not far from Ashford Stud, where Aisling works as the Director of Bloodstock. They own half of the 100 Thoroughbreds living there. The other half belongs to their clients.

The Duignans purchased Eagle Sound for $70,000. Before Echo Sound, she had produced eight winners. She was 19 when she foaled Echo Sound.

Echo Sound has won five of her six starts and made over $450,000 under the care of trainer Rusty Arnold. Her last race was a 4 ¼ length romp at Saratoga in the G. 3 Victory Ride Stakes at Saratoga July 3rd. That was sweet for Arnold, who trained Victory Ride: “It’s a really good thing to run in a race named after one of your horses. Not many people get to do that. So it’s fun.” Duignan said simply, “Today was her best race.”

Echo Sound is the first horse Arnold has trained for Duignan: “I have known Spider for a long time through the sales and being around Keeneland. I hadn’t trained for Spider. About a year ago, when the filly went to Florida to be broken, he approached me and said, `Hey, I’ve got a filly we’re going to put in training and I’d like to give you this filly.’ I said, `I’d love to have her.’”

He’s been smiling ever since: “As owners, they’re the greatest. He said, `My deal is I send you the horse and you drive the car and just tell us how she’s doing and where we want to go and what you want to, and we’re on board.’ He said this was his mare’s last foal and he wanted to replace the mare with her.

“They’re horse people, he and his wife. They’re wonderful people.”

They have made a substantial impact in Thoroughbred racing ever since Duignan emigrated from Ireland to America with a plan he never followed four decades ago.

“I’ve been lucky. I’ve definitely been lucky,” Duignan said. “I was just one of those kids born with a love of horses. I started out with ponies. I realized I couldn’t make it as a rider.”

He took a job at Airlie Stud, succeeding a worker nicknamed Spider. When his boss at Airlie struggled to pronounce Duignan’s name, he gave him the same nickname. It’s stuck for the rest of his life.

At Airlie, Duignan met the veterinarian, John Hughes, who took a personal interest in him and arranged a job for him across the Atlantic: “John Hughes sent me to America to Bill O’Neill at Circle O Farm. I’ll be forever indebted to John Hughes. That was my first trip to America. At 21, you have a different view. You’re looking to explore. My plan was to do a year here in America and a year in Australia and then back home. But I loved Kentucky. I never went to Australia.”

In America, Duignan hooked up with another Irishman, Pat Costello, who had preceded him to America by six months. Costello also worked at Circle O and they became close friends and partners, originally participating in a partnership called The Lads. In 2001, they co-founded Paramount Sales. “Pat and I started Paramount Sales and that was great,” Duignan said. “We’ve never had any differences. I’ve always been lucky to have great partners.”

Duignan, who also hooked up with David Garvin at Ironwood Farm and Dr. Tony Lyons of Castleton Farm, credits both of them for his success.

In the spring of 2022, the Duignans were honored to return to Ireland to accept the Wild Geese Award from the Irish Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association, made to “compatriots who fly the tricolour in exemplary fashion on foreign fields.” Duignan said, “That was a nice award from my peers. It meant a lot to me.”

Horses still do: “I enjoy getting a good horse and selling a good horse. I still love the whole process.”

Lael Stables with She Feels Pretty

Nineteen years removed from the triumph and tragedy of their Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro, Roy and Gretchen Jackson are still winning major stakes on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Their outstanding turf filly She Feels Pretty won her fourth consecutive graded stakes, taking the G.1 New York Stakes at Saratoga June 6th. “We’re still kicking,” Jackson laughed. “At our age, 88, we’re sure enjoying it. We’re just lucky to have this horse.”

Their horses have been lucky to be owned by the Jacksons.

“I was a big fan of theirs since Barbaro,” She Feels Pretty’s trainer Cherie DeVaux said. “You see them go through the highs and lows and they handled that with such grace. It’s really special to have a relationship with them.”

There are few breeders and owners who have raced so many top horses in North America and Europe, including the unbelievable feat of Barbaro winning the Gr.1 Kentucky Derby and George Washington winning the Gp.1 2000 Guineas on the same afternoon, May 6th, 2006. “They’ve both been wonderful experiences,” Jackson said. “We’ve been pretty lucky in the whole situation. You don’t know if they’re going to stay healthy. It’s such a gamble. We just sort of plodded along through the years just trying to have some fun.”

They sure know how to plod along. She Feels Pretty has already given the Jacksons their 14th season with more than one million dollars in earnings and their 18th over $900,000. Their horses have won 495 races from 2,511 starts with earnings topping $32.4 million. And, of course, they were the Eclipse Award Outstanding Owners of 2006.

Being able to share this success together cannot be underemphasized. “It’s been great,” Jackson said. “She’s the one. She was involved at a young age riding.”

They grew up just 10 miles apart in Pennsylvania. Gretchen was a foxhunter, a pastime of Roy’s mother, who also dabbled in racehorses.

Roy spent six years as a stockbroker before following his passion for baseball, owning a couple minor league teams and co-founding Convest, a management firm for professional athletes. He sold his share in the company to concentrate on horse racing.

By then, Lael Farm was up and running successfully. The Jacksons purchased the 190-acre property in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in 1978 and named it Lael, the Gaelic word for loyalty.

They backed up their loyalty by taking care of all their horses when they were done racing. For years, Barbaro’s dam, 25-year-old La Ville Rouge, who earned more than $250,000 with six victories from 25 starts for Hall of Fame trainer Phil Johnson, shared her paddock with Superstar Leo, the first horse the Jacksons purchased in Europe, and $400,000-plus graded stakes winner Belle Cherie, also trained by Johnson.

In five consecutive starts, Superstar Leo won the Gp.3 Norfolk Stakes at Royal Ascot, a restricted race for sales graduates, finished second in the Gp.1 Phoenix, won the Gp.2 Flying Childers and finished second in the Gp.1 Prix de ’Abbaye de Longchamp. She finished her career with five victories and four seconds from 13 starts, earning $284,001.

From 15 foals, she produced 11 winners, including Enticing, a dual Gp.3 winner and the dam of three-time Gp.1 Prix de la Forest winner and $1.2 million earner One Master, who had seven victories from 23 starts.

After Superstar Leo died on Lael Farm at the age of 26 on June 26th, 2024, Jackson said, “We were very lucky to purchase her after my wife Gretchen happened to see her run. We brought her over from England after she was through having foals to live out her life at our place.”

That’s a destination Barbaro never reached.

Barbaro was brilliantly trained and managed by legendary equestrian Michael Matz, a six-time U.S. national champion who was given the honor of carrying the U.S. flag at the 1996 Olympics Closing Ceremony. Seven years earlier, on United Airlines Flight 232, he saved three siblings traveling alone and went back to rescue an 11-month-old girl after the plane crashed. One-hundred eighty four people survived the crash; 112 did not. The three siblings remained in touch with Matz and hooked up with him before he saddled undefeated Barbaro in the 2006 Kentucky Derby. In a domination seldom seen in the Run for the Roses, Barbaro won effortlessly by 6 ½ lengths under perfect handling by Edgar Prado. That made Barbaro six-for-six, three-for-three on both turf and dirt, with earnings topping $2.3 million.

He didn’t survive the Preakness. After breaking open the starting gate and being reloaded, Barbaro suffered a catastrophic fractured right leg in the first eighth of a mile.

Over the next eight months, fans and non-fans followed his battle to survive under the care of Dr. Dean Richardson at the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center. After finally getting well enough to graze outside his barn, he suffered the crippling, painful hoof disease laminitis, the same disease that killed Secretariat in 1989. Barbaro was humanely euthanized. Gretchen said at a press conference. “Grief is the price we all pay for love.”

It’s nearly 20 years later. “Isn’t that unbelievable?” Roy Jackson said. “It was like a real roller coaster. Dean Richardson would call every morning. So many people followed the whole situation. We couldn’t believe the bins of cards we got from kids.”

Now, the Jacksons have another popular horse, She Feels Pretty, who has already won four Gr.1 stakes, missing two more by a half-length and three-quarters of a length. Overall, she’s seven-for-10 with one second and two thirds. “She’s amazing,” DeVaux said.

And she has a pal, a black and white goat that dutifully follows her around, even loading into a trailer. His name is Mickey. “Mickey has been to Woodbine, California, Keeneland and Saratoga,” Jackson said. “Mickey has done the job. Mickey’s really got to get some of the credit for the whole thing.”

Pin Oak Stud with Parchment Party

The late Ms. Josephine Abercrombie, a consummate horsewoman who founded Pin Oak Stud in 1952, left a tough act to follow when she passed peacefully in her home January 5th, 2022, just 10 days before her 96th birthday.

“Mrs. Abercrombie was an amazing lady and a great steward of the land, and most importantly, it was always the horse comes first,” said Clifford Barry, who’s been working at Pin Oak Stud for 35 years.

She would have smiled knowing that Dana and Jim Bernhard, who purchased Pin Oak Stud in November, 2022, and their son Ben, a rocket scientist turned horseman, have continued her good work, complementing their considerable success on the track with cutting-edge technology to prevent equine injuries, like the one that killed their first and best horse, Geaux Rocket Ride, as he was preparing for the 2023 Breeders’ Cup Classic. He was their first Thoroughbred, a birthday gift from Jim to Dana.

Simply put, the Bernhards, like Abercrombie, do the right thing. “That’s where it all starts,” Ben said. “Everything we do, we put the horse first, and my parents have driven that point home.” His mother said, “We are passionate about doing a good job for the horses. They can’t speak for themselves.”

Barry has witnessed the Bernhards’ ongoing commitment: “It’s been amazing to watch Jim and Dana be like-minded as Mrs. Abercrombie. I mean it really has been heartwarming to watch. Anytime you go through a major transition like this, you worry what the next entity will involve. But they’ve come in, and we got a facelift to the farm and added new property and new buildings and really have got the horses’ health and welfare at heart for sure.”

Abercrombie was an incredible owner and breeder. Among her nearly 100 stakes winners were her home-bred Eclipse Champions Laugh as well as Confessional, Peaks and Valleys and Broken Vow. She was The National Breeder of the Year, in 1995 and the winner of the Hardboot Award from the Kentucky Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association and the William T. Young Humanitarian Award. In 2018, Abercrombie was the Honor Guest of the Thoroughbred Club of America in appreciation for her “enduring sportsmanship, acumen and vision, and her devotion to the loftiest principles established by earlier leaders on the Turf.”

Like Abercrombie, Dana grew up with horses: “I grew up in Louisiana. I was given my first horse, a Tennessee Walker, when I was eight years old, and I’ve owned a horse ever since. I began riding that day. She was a trail horse for me. I was given my next horse for my 10th birthday, Dixie. I had her until I was 29. My love was horses, not just racehorses.”

Dana worked as a corporate attorney and marketing director. She met Jim, the founder and partner of Bernhard Capital Partners, through work. Jim’s company, based in Baton Rouge, now manages about seven billion dollars buying and investing in companies, and has some 30,000 employees.

“I was a lawyer and our law firm handled Jim’s corporate law,” Dana said. “He was a client. When we decided to start dating, we had an office rule against dating co-workers. I said, `How about clients?’ The senior partner offered me a list. We got married some six months later.”

They married in 1993 and Jim became an avid horseman. Asked why he loved it, he said, “Because Dana loves it.” They have purchased and maintained a dozen Friesians, a breed originated in the north Netherlands which nearly went extinct more than once. They ride their horses at Pin Oak Stud in Kentucky and Pin Oak Stud South in Baton Rouge. “When we got our first Friesians some 13 years ago, there were less than 75 in the United States,” Dana said. “Their personality reminds me of our two labrapoodles. They are just big puppy dogs.”

In June, 2021, Jim gave Dana a birthday gift, a trip to Lexington to buy a Thoroughbred yearling at the Fasig-Tipton July Sale. They wound up with three yearlings. The first one was Geaux Rocket Ride, a son of Candy Ride out of the Uncle Mo mare Beyond Grace. He cost $350,000 and was given to Hall of Fame trainer Richard Mandella.

Geaux Rocket Ride won a maiden race by 5 ¾ lengths, then finished second by 2 ½ lengths to Practical Move in the G.2 San Felipe Stakes. Another victory by a length and three-quarters in the $100,000 Affirmed Stakes convinced his connections to up the ante. Sent off at 12-1 in the Grade 1 Haskell at Monmouth Park, Geaux Rocket Ride went head-to-head with the even-money favorite, Arabian Knight, put him away, then turned back a rally by Kentucky Derby winner Mage, winning by a length and three-quarters. In his final start before the Breeders’ Cup Classic at Santa Anita, Geaux Rocket Ride was second by a neck to Arabian Knight in the G.1 Pacific Classic. His three victories and two seconds in five starts had produced $980,200 in earnings. He was a legitimate contender for the Classic.

“In the Haskell, we were thrilled,” Dana said. “Rocket was such a feisty horse on one hand, feisty with his feed bucket, but in the barn and the paddock, he was so kind and loving. He loved his bath. He played with the water hose. He was quite a character. We just loved him. He was our first racehorse. We still love him to death.”

One week before the Breeders’ Cup, with Dana and Jim watching his workout live on TV, Geaux Rocket Ride suffered a horrific injury in his front leg, which was described by Breeders’ Cup officials as “an open condylar fracture with intersesamoid ligament damage.”

Dana said, “We were at our home in Pebble Beach and about to fly down to LA. We watched him live.” Jim said, “We saw it live. We didn’t know the extent of it until we drove down there. We couldn’t save him. His leg was too far gone.”

He was euthanized the following Wednesday. “It was a typical roller coaster ride,” Mandella said. “We had the greatest time with him, but also had one of the worst days of my life.”

His respect for the Bernhards is immense: “It’s a wonderful family, I can’t say enough good things about them. They want to do everything right by the horse.”

Ben, who had spent a lot of time hanging out with Mandella at his barn, was deeply affected, so much that he decided to leave Space X in Los Angeles and become a vice president of Pin Oak Stud and start his new company of developing equine sensors, Stable Analytics, with technology similar to the ones he had used at Space X: “Geaux Rocket Ride was training at Santa Anita, and I used to hang out with Richard Mandella, probably the biggest reason I’m into horse racing. Learn from him. Watch Geaux Rocket Ride train. I just got so into it. I decided to make the move.”

Dana said, “It was a wonderful thing. He is very passionate about preventing this type of accident in the future.”

Jim said simply: “He’s smart.”

Ben said of his career change: “It’s a lot of things that are different obviously, but there are surprising similarities. I talked to my friends back at Space X. They said, `There’s nothing like the rush you get watching a rocket launch.’ I said, `There’s something similar, watching your horse win a race.

“I came into this trying to make it as much of a math problem as I can. I know math and engineering. I think there’s an opportunity to look at it from that perspective. Geaux Rocket Ride had the best horseman, the best jockey, the Breeders’ Cup veterinary staff and somehow he still gets injured. There’s got to be a way to detect things.”

Ben developed equine sensors, which all the 150 to 170 Thoroughbreds wear at Pin Oak Stud: “They’re practically air-space sensors which began in the aerospace industry. We see gait changes and data. I’ve never really been a horse person. Richard Mandella changed that.”

Mandella said of Ben, “I’m sure he makes his parents proud. He’s just a class person, a gentleman, and maybe genius-smart. Yet he’s just the most normal young guy you could ever meet, just a pleasure to be around.”

At the Keeneland 2022 September Yearling Sale, the Bernhards bought Parchment Party, a son of Constitution out of Life Well Lived by Tiznow bred by Bobby Flay for $450,000. Ben’s sensors caught a potential problem. “We found a small abscess that was growing,” Jim said. “We were able to take care of that long before it became a major problem.”

Parchment Party, who is trained by Hall of Famer Bill Mott, won his first two starts. On June 6th, 2025, at Saratoga, he captured the Belmont Gold Cup when it was switched from turf to dirt, by 8 ½ lengths. In doing so, he clinched a berth in the starting gate for the Melbourne Cup, the race that stops a nation. “He’s the first Kentucky-bred to make the Melbourne Cup,” Jim said. “Australia? It’s just a little island down south from here. It’ll be fun.”

Market Boom Record-breaking demand fuels new benchmarks in 2-year-olds in training sale season

Article by Michael Compton

Despite an uncertain economy, the 2025 2-year-olds in training sale season wrapped up in June with an undeniable display of market power. Far from simply holding steady, Ocala Breeders’ Sales (OBS) and Fasig-Tipton broke numerous records across their major auctions. The market saw unprecedented top prices, and auction results demonstrated impressive leaps in gross revenue, average sale price, and median figures. The resilience in the marketplace sends a clear message: the demand for promising young talent is incredibly strong.

Buyer confidence drove significant year-over-year growth for both OBS and Fasig-Tipton. The 2-year-old sales, which ran from March through June, saw robust market activity. Out of 2,407 horses offered during the season, an impressive 1,955 (81 percent) changed hands, generating a total of $226,124,100 in gross sales. This performance marks a jump in gross receipts from 2024, when 2,137 out of 2,691 horses offered (79 percent) sold for $208,181,400.

New Benchmarks