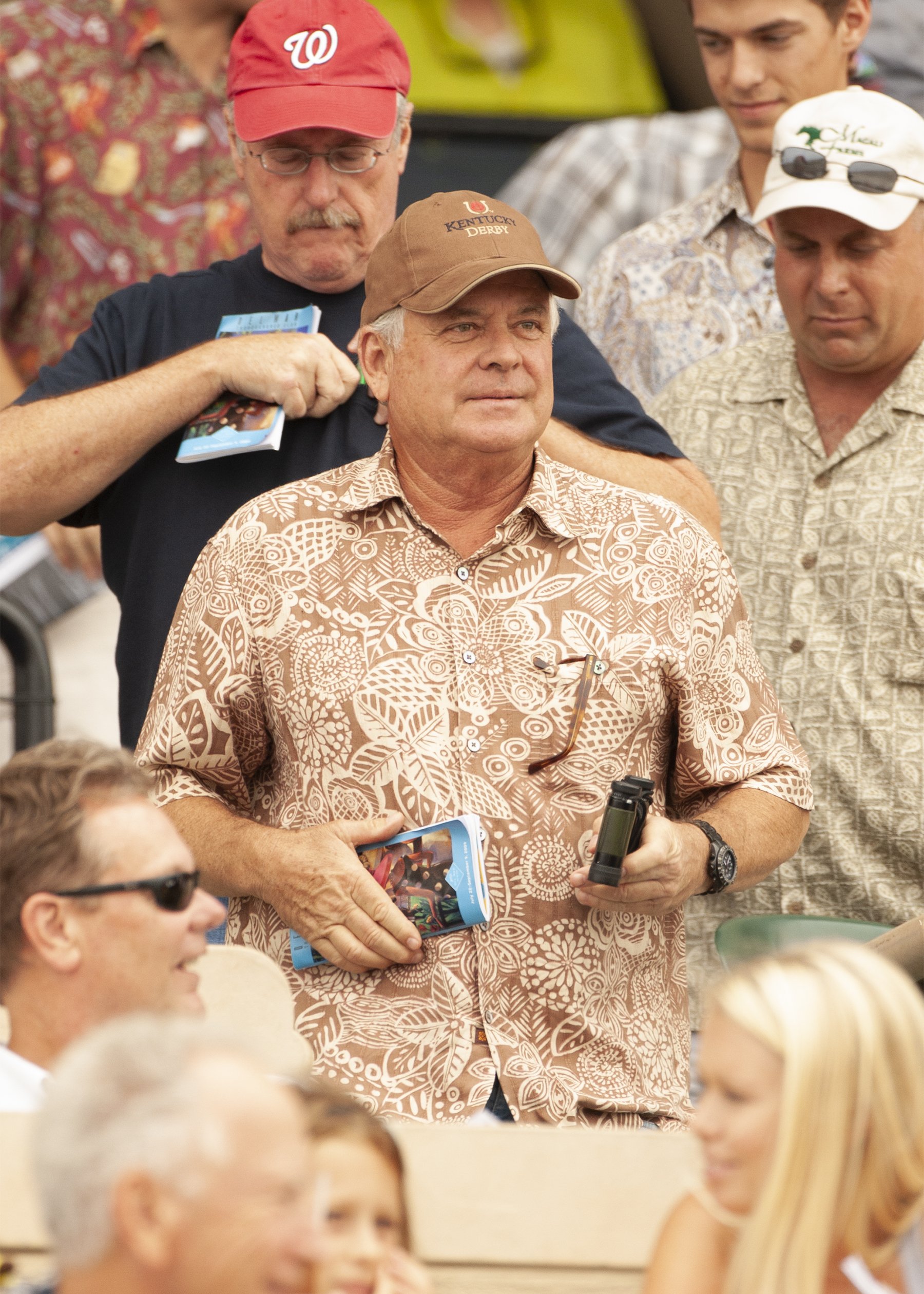

Earle Mack - The Eclipse Award winning humanitarian philanthropist

/By Bill Heller

Many people wonder what they can do to help people in need. Other people just do it. That’s how Earle Mack, who received an Eclipse Award of Merit earlier this year for his contributions to Thoroughbred racing, has fashioned his life. So, at the age of 83, he flew from his home in Palm Beach, Florida, to the Hungary/Ukraine border to deliver food and clothing to desperate Ukrainian refugees who fled their homes to escape the carnage of Vladmir Putin’s Russian thugs.

“I’m going to the front,” he declared in early March. “I woke up and said, `I have to do my part.’”

He’s always done more than his part. Besides being an extremely successful businessman, he was the United States Ambassador to Finland. An Army veteran, he is helping veterans with PTSD through a unique equine program. He supports the arts. He is an active political advocate. And he has enjoyed international success with his Thoroughbreds—breeding and/or racing 25 stakes winners, including 1993 Canadian Triple Crown Winner and Canadian Horse of the Year Peteski, a horse he purchased from Barry Schwartz; $3.6 million winner Manighar, the first horse to win the Australian Cup, Ranvet Stakes and BMW Cup; and 2002 Brazilian Triple Crown winner Roxinho. Two of his major winners in the U.S. were November Snow and Mr. Light. And he founded the Man o’ War Project, which helps veterans with PTSD via equine-assisted therapy.

“I love my country,” he said. “I love the arts. And horse racing is in my blood.”

Literally, Ukraine is in his blood. He discovered through Ancestry.com that he is two-thirds Ukrainian. “My great grandfather fled Ukraine to go to Poland,” he said.

So he had to go to Ukraine.

“He’s an extraordinary man,” owner-breeder Barry Schwartz, the former CEO of the New York Racing Association and the co-founder and CEO of Calvin Klein, Inc., said. “I’ve known [Earle] a very, very long time. He loves the horse business. He’s extremely philanthropic. I’ve been on the board with him for the Cardozo Law School at Yeshiva University [where Earle served as chairman for 14 years]. I get to see a different side of him. He’s smart. He’s articulate. He’s a class act.”

In early March, Mack, a trustee of the Appeal Conscience Foundation, called owner/breeder Peter Brant (a fellow member of that foundation) and former New York State Governor George Pataki (whose parents are Hungarian) to head to one of the most dangerous locations on the planet. Brant supplied the plane. His wife, Stephanie (Seymour), brought 40 big duffle bags of clothing, “She spent over $30,000 buying the clothes,” Mack said. “I took clothes off my racks. I brought all the fruit that we could find and a couple boxes of chocolate.”

The delegation landed on March 10th, two weeks after Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, and began an unforgettable experience. Displaying yet another talent, he wrote about his trip in an op-ed published by The Hill, an American newspaper and top political website, on March 16th:

“How would you feel, in this day and age, if you were fleeing your home with only the few things you could carry in freezing winds and winter temperatures? How would you feel sitting in your car for 17 hours, waiting to cross a border, all the while worried that the sound in the sky above might be a missile or bomb bringing certain death? How would you feel trapped in your basement or a public bomb shelter, food and water running out, afraid to leave and face death? How would you feel if your city was under attack and you watched as civilians were shot up close by Russian soldiers and neighborhoods were rubbled from faraway artillery? How would you feel leaving your fathers, husbands and brothers behind to fight against impossible odds?

“This is what I have wondered, listening to heartbreaking stories that have brought me to tears, told by Ukrainian refugees on my recent trip to the Hungarian border and into the Ukrainian city of Mukachevo, where hundreds of thousands have fled the war with Vladmir Putin’s Russia.”

Mack went on to share his experience of Ukraine, “Ukraine has cold winds. Thirty-five feels like 15. Lots of hills and farmland. Peter and his 17-year-old daughter stayed at the border. We went into Mukachevo, a city of about 20,000 to 25,000 people. At that point—two weeks into the war—there were more than 500,000 people in that area, hoping that there’s something to go back to.

“We went into a children’s hospital ward filled with children. We looked at a COVID ward with kids lying down. We went into a school converted into a dormitory. We saw all these kids, ages two to eight with their mothers. Men, 16 to 65, weren’t allowed to cross the border. The kids were crying. Not much to eat. We brought in the fruit. We brought in the chocolate.

“I started handing out the chocolates. These kids ate all the chocolate. I have the empty box. I put it on one of the six-year-old kid’s head and started singing, `No more chocolates; no more chocolates.’ That kid takes the empty box and puts it on another kid’s head. They’re all singing, ‘No more chocolates; no more chocolates.’ When I was leaving, the director of the center came running after me and said this is the first time they laughed in two weeks.”

Mack wrote of this bittersweet moment in his story in The Hill: “As we prepared to leave, there was a 12-year-old girl who literally begged me to take her with us. I can’t describe how hard it was to walk away from this young girl whose life is forever changed.”

This from a man whose life is forever changing.

Terry Finley, the CEO of West Point Thoroughbreds, said, “Although we’ve never owned a horse together, we try to make a point to spend a couple of races at Saratoga, just the two of us in the box. I pick his brain. He’s such a good person. He’s got a world of knowledge. He’s a fun guy. He’s a caring guy—as cool a guy as there is in the industry.”

Peter Brant, Earle Mack, Lily Brant, Christopher Brant & Karen Dresbach (executive vice president of the appeal of Conscience Foundation) before boarding a plane loaded with medical supplies, food, clothing and other essentials for Ukrainian refugees arriving in Hungary

One of four boys born in New York City, Earle’s father, H. Bert Mack, founded The Mack Company, a real estate development company. Earle was a senior partner of The Mack Company and a founding board member of the merged Mack-Cali Realty Corporation. He has served as the chairman and CEO of the New York State Council on the Arts for three years and produced a number of plays and movies. His political action included an unsuccessful attempt to draft Paul Ryan as the 2016 GOP presidential candidate.

His entry into horse racing was rather circuitous. He learned to ride at the Sleepy Hollow Country Club in North Tarrytown, N.Y. “All the juniors and seniors were allowed to use the trails at Sleepy Hollow County Club,” he said. “I was 16, 17. I got to ride on the course. That’s how I learned to ride.”

Just after graduating college, he returned to Sleepy Hollow. “One day, I was dismounting; the riding master who taught me how to ride came over to me and said, `I’m very sorry to tell you this, but my wife has cancer and needs surgery. I need $2,500 to pay for surgery.’ He owned a horse who won a race up in Canada.”

Mack went inside with him to examine the horse’s papers. “I said, ‘I’m buying a $5,000 horse for $2,500’; I bought it on the spot. I thought this sounds like a good deal. The horse’s name was Secret Star. He stayed in Canada and raced at Bluebonnets and Greenwood. The horse won about $20,000.”

Flush with excitement, Mack bought four horses from George Kellow. “They did well. I said, ‘This game is easy.’”

He laughs now—well aware how difficult racing can be. That point was driven home in the late 1960s after Mack had graduated from Drexel University with a Bachelor’s Degree in Science and Fordham School of Law. He served in the U.S. Army Infantry as a second lieutenant in active duty in 1959 and as a first lieutenant of the Infantry and Military Police on reserve duty from 1960–1968.

In the late 1960s, he was struggling with his Thoroughbreds. “My horses weren’t doing that well,” he said. “I bought two seasons to Northern Dancer. His stud fee was $10,000 Canadian. When the stud fee came due, I didn’t have the money to pay for it. I walked over to my dad’s office. I said, ‘I need a loan.’ He said, `No, you’re in the wrong business. Get out of that business.’”

Mack walked back to his office. “I started to think, ‘How am I going to get this money?’ Twenty minutes later, my father threw a check on my desk. Then he got down on his knees, and he said, ‘Son, sell your horses. Get out of this business. You’re not going to make money in this business.’”

He might have had a good thought. “The two Northern Dancers never amounted to anything,” Mack said.

That seemed like the perfect time to follow his father’s advice and give up on racing. But Mack stayed. “I just loved the business; I loved being there. I loved the horse. I loved the people. I just loved it—that’s why. I still love the sport. I love to go to the track. I love to support the sport. I love to help any way I can. I’ve given my time and my efforts to our industry.”

That list is long: Board of Trustees member of the New York Racing Association 1990-2004; chairman of the New York State Racing Commission (1983–89); member of the New York State Thoroughbred Racing Commission (1983–1989); member of the Board of Directors of the New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Corp (1983–89); and senior advisor on racing and breeding to Governor Mario Cuomo and Pataki.

The Earle Mack Thoroughbred Champion Award has been presented annually since 2011 to an individual for outstanding efforts and influence on Thoroughbred racehorse welfare, safety and retirement.

He has been a long-time backer of The Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation and the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation.

In 2011, he established the Earle Mack Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation Award. The first three winners were Frank Stronach, Dinny Phipps and famed chef Bobby Flay.

His brother Bill, the past chairman of the Guggenheim Museum and Guggenheim Foundation, also owned horses, including $900,000 earner Grand Slam and $500,000 earner Strong Mandate. But he did better with investments in art. “He bought art; I bought horses,” Earle said. “Guess who did better? Much better.”

But who’s had more fun? Mack bought Peteski, a son of 1978 Triple Crown Champion Affirmed out of the Nureyev mare Vive for $150,000 from Barry Schwartz after the horse made his lone start as a two-year-old, finishing fifth in an Ontario-bred maiden race on November 14, 1992.

Earle Mack, Barry Irwin, jockey Jamie Soencer and Team Valor connections celebrate Spanish Mission winning the $1 million Jockey Club Derby Invitational Stakes at Belmont Park in 2019

After buying Peteski, Mack sent the horse to American and Canadian Hall of Famer Roger Attfield. Peteski and Attfield put together an unbelievable run: seven victories, two seconds and one third in 10 starts, finishing with career earnings of more than $1.2 million.

Mack told the Thoroughbred Times in October 1993, “Bloodstock agent Patrick Lawley-Wakelin originally called the horse to my attention. I’d always liked Affirmed as a stallion and together with my connections, we thoroughly checked the horse out before I bought him. I was lucky to get him. There were other people trying, too, but I had long standing Canadian relations and was able to move fast. They knew I was a serious player.”

All Peteski did was win the Canadian Triple Crown, taking the Queen’s Plate by six lengths; the Prince of Wales by four lengths and the Breeders by six. He followed that with a 4 ½ length victory in the Gr. 2 Molson Million. In his final start, Peteski finished third by a head as the 7-10 favorite in the Gr. 1 Super Derby at Louisiana Downs.

“The thrills he’s given me are something money can’t buy,” Mack told Thoroughbred Times. “One of the reasons for staying in Canada for the Triple Crown was because of the wonderful and nostalgic feelings of my youthful days spent racing there. This is the greatest horse I’ve ever owned.”

Earle with jockey Gerald Mosse at Newbury Racecourse in 2019

Mack would race many other good horses, but the ones who may have had the greatest impact are the anonymous ones he helped locate who participated in the Man o’ War Project—perhaps Mack’s greatest gift. In 2015, out of his concern about the mental health crisis facing veterans, he created and sponsored the Man o’ War Project at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center to explore the use of and scientifically evaluate equine-assisted therapy to help veterans suffering from PTSD or other mental health problems. Long-term goals are to test that treatment with other populations. Immediate results have been very promising.

There is a sad reality about veterans: more die from suicide than enemy fire. The project was the first university-led research study to examine the effectiveness of equine-assisted therapy in treating veterans with PTSD.

“My love for the horse and my great respect and empathy for our soldiers bravely fighting every day for our country and not getting the proper treatment led me to do this,” Mack said. “Soldiers come home with the strain of their service on the battlefield. The suicides are facts. There was no science or methodology proving that equine-assisted therapy (EAT) could actually and effectively treat veterans with PTSD. All reports were anecdotal.”

The project was led by co-directors Dr. Prudence Fisher, an associate professor of clinical psychiatric social work at Columbia University and an expert in PTSD in youth; and Dr. Yuval Veria, a veteran of the Israeli Armed Forces who is a professor of medical psychology at Columbia and director of trauma and PTSD at New York State Psychiatric Institute.

After a pilot study of eight veterans lasting eight weeks in 2016, 40 veterans participated in a 2017 study also lasting eight weeks. Each participant underwent interviews before, during and after the treatment period and received follow-up evaluations for three months post-treatment to determine if any structural changes were occurring in the brain. Each weekly session lasted 90 minutes with five horses, using the same two horses per each treatment group. The veterans started by observing the horses and slowly building on their interactions from hand-walking the horses, grooming them and doing group exercises.

“We take a team approach to the treatment,” Fisher said. “We have trained mental health professionals, social workers, equine specialists and a horse wrangler for an extra set of eyes to ensure safety during each session.”

Marine Sergeant Mathew Ryba at the Bergen Equestrian Center

The results have been highly encouraging. A 2021 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry concluded “EAT-PTSD shows promise as a potential new intervention for veterans with PTSD. It appears safe, feasible and clinically viable. These preliminary results encourage examination of EAT-PTSD in larger, randomized controlled trials.”

Mack was ecstatic: “This is a scientific breakthrough. You could see the changes. It’s drug free. Before, you had to take more and more and more drugs. Before you know it, you’re hitting your family.”

The Man o’ War project works. It helps. It could possibly help a lot of people besides veterans. That would be the biggest victory of Mack’s remarkable life.

“That would be my Triple Crown,” he said.

Mack was asked how he does what he does in so many varied arenas. “Pure tenacity, drive and 24/7 devotion to the things that were important to me and public service,” he replied. “I’ve devoted my life to public service, my business, horses and the arts.”

And now, to Ukraine. Lord bless him for that.

![Mike TrombettaBy Bill Heller For the first 15 years of his 31-year training career, 55-year-old Mike Trombetta split every day between the racetrack and his brother Dino’s demolition company in White Marsh, Maryland. “He would train horses in the morning and knock down buildings in the afternoon,” his long-time friend and client R. Larry Johnson laughed. Dino added, “Then he’d go back to the track in the evenings just to check on things.” Of course he did. That’s what he, Dino and their sister Laura learned from their parents. “Our dad worked extremely hard,” Dino said. “Both him and my mom were hard workers. That’s how we grew up. We worked hard in everything we did. That’s what it took to have success.” Mike could still be working two jobs had he not had the good fortune to take over the training of a horse who had previously made just one start, finishing 12th by 24 lengths as a two-year-old in 2005. That horse, Sweetnorthernsaint, would go off the favorite in the 2006 Kentucky Derby, making a strong middle move under Ken Desormeaux before tiring to finish seventh. Sweetnorthernsaint then finished second in the Preakness Stakes. “That gave us national exposure,” Trombetta said. “That gave us a big push for sure.” The following year, Trombetta’s starts increased from 312 to 422, his victories from 78 to 106 and his earnings from $2.7 million to $3.5 million. Trombetta abandoned his demolition career and began upward trending with his training. In 2019, he posted a career high in earnings—$4,614,509—helped by his three-year-old Win Win Win, who was ninth in the Kentucky Derby, and his two-year-old Independence Hall, who became a legitimate contender for the 2020 Kentucky Derby. Independence Hall ran into problems in 2020, but Trombetta still finished 24th in earnings with more than $4.1 million and a win percentage of 16.0. Trombetta has posted a win percentage of 20 or higher for an entire year 11 times. But the past several months have been a bit rough. Through early June, he ranked 36th in the country in earnings with nearly $1.6 million. Yet he still is winning at a 16.4 percent rate. “We’re not doing that well,” he said on June 14. “This year, it’s been an adjustment year coming off the COVID. We were hoping at the beginning of this year things would go back to normal. Then Woodbine got delayed. It got a little weird here. We had a herpes situation in Maryland. For several months, they wouldn’t let horses come in or leave. That was a bizarre situation. Then, at Laurel, they had to redo the track. We’re still not back to normal. It seems like something has been going on—something new to deal with. It’s hard for all of us.” He feels the same way on the thorny issues of medication and whips. “I’m probably like a lot of other trainers,” he said. “What we’d like to have more than anything is a clear understanding of the dos and don’ts, especially in the Mid-Atlantic states. We just want to know what the rules are and how to play the game. When you turn on a football game, they all have fields of 100 yards and 15 minutes in a quarter. Horse racing is anything but that. It’s different in every state.” That is about to change next summer when the Horse Racing Integrity Act comes to life. Will uniform rules become the norm? “We can hope,” Trombetta said. “Time will tell. It would be great just to get everybody knowing what the game looks like. Now, in every jurisdiction, there’s something different. We want to stay out of harm’s way. This Lasix thing is a great example. Two-year-olds can use it in one state, but not in another. I just hope the powers [that] be get something that works for the whole industry so that we can follow and understand. It’s the same thing with this whip rule. It’s different in other states. One state allows four times, one state says six; and in one state, they can’t use them at all. We’re getting further away from uniformity. Guys like us that are in this region race throughout the country for the most part. When you go through the stable gate somewhere else, it’s a different rule.” Can the Horse Racing Integrity Act end that problem permanently? “In a perfect world, yes,” Trombetta said. “I don’t know if they’re capable of doing it.” This summer, Trombetta’s horses—now between 80 to 90—are stabled at Far Hill, Timonium temporarily until Laurel’s renovations are complete and in Delaware. His horses also race in Florida in the winter and in New York in the summer when they belong. His winter stable usually numbers 60 to 70 horses. “We try to take the right horses to the right place,” Trombetta said. “We work off the condition books. There are little differences in each track. Obviously, when you go to New York, you have to know your horse is capable of competing in New York. We don’t get it right all the time, but we try. Surfaces come into play: dirt, synthetic, turf. You have to figure in all of the factors. I carry six, seven condition books with me.” Is it like being back in school? “It can be at times, because it’s constantly changing,” Trombetta said. “I’m checking those things at 6 or 7 at night to make sure I can stay on top of it—make sure I’m not missing anything.” His ongoing success suggests he usually doesn’t miss many things. He’s proficient at preparing his young horses and knowing when to back off. “I try to give them the benefit of the doubt,” he said. “We identify the ones that need their first race. I try to get them prepared for the first race so they don’t get exhausted. I want to see them prepared.” He also wants to give his horses time when they need it. “We try to, as long as owners are patient enough,” Trombetta said. “Our numbers off the layoff have been pretty good over the years. There’s no quick way to do it. It takes time. Some individuals require more time than others.” Experience has helped him shape his program. “You learn it over time,” he said. “It’s still frustrating to this day. Sometimes you ask for one more race of a horse, and it’s one race too many. Six to eight weeks off give these guys a good break. We race year-round somewhere, so you have to know when it’s not too late to take them out of service for a while. By giving them time, we seem to have one ready to take his place.” His owners have provided considerable help. “A lot of the folks I work for, Live Oak, Country Life and Larry Johnson, they all have complete facilities with training tracks, all three of those. Breeding, resting and training, they have complete facilities to get all the work that’s needed. That’s a luxury for me—to be associated with these people that have those facilities.” Trombetta’s stable includes horses he co-owns with his brother and dad, as he races up and down the East Coast. He, his wife, Marie, and their two of three children still in school live on their small farm in Baldwin, Maryland. “Maria and I met in high school, and we’ve been together ever since,” Trombetta said. Their oldest child, 27-year-old Nicole, is out on her own. Their two sons, 16-year-old Michael and 14-year-old Dominic, are experiencing racing in a way their parents couldn’t have imagined when they were growing up—on the internet. “Michael follows it very easily,” Trombetta said. “Sometimes he finds out stuff before I do. They have the whole world at their fingertips.” Trombetta’s introduction to racing was more hands-on. “My dad, Rudy, worked construction his whole life,” Trombetta said. “He had a small construction business on his own. He was always a fan of the horses. He had a friend, and they got a few horses together.” Trombetta began working at nearby Timonium as a teenager. “It was 20 minutes from our house in Perry Mall,” he said. “I was 14...15 years old. It seemed to be a comfortable place for me. I loved the horses, and I loved racing.” He began training in 1986 before his 20th birthday. His first winner came at Atlantic City with Amant De Cour. Trombetta struggled early, Four years into his career, he won just 10 races in 1989. “Obviously, it wasn’t enough to derive an income, so I had to do other things on the way,” he said. “It takes a long churn to build a stable. I did everything I could. When you’re young, it’s pretty challenging.” Which is why he worked two careers—one at the track and one with his brother’s company, “My brother worked with me a long time, up until he got Sweetnorthernsaint,” Dino said. “He would go to the track in the morning, then work with us all day long, 8 to 10 hours with me, and go back to the track in the evening.” When Sweetnorthernsaint redirected Trombetta’s training career, he pondered giving up his life in demolition. “I told him to take some time,” Dino said. “Enjoy this opportunity. I told him to do it and then decide. He just stayed with the horses. I was tickled to death for him because I knew that was his true passion. I lost a good employee, but I was very happy for him.” Sweetnorthernsaint was sent to Trombetta by his former trainer, Leo Azpurua Sr., in Florida after his nightmare of a debut in his first start as a two-year-old in a maiden turf race at Colonial Downs, August 1, finishing 12th in a field of 14. “He was sent to me, and I was told point blank: `He’s very difficult to handle, but he’s a good horse.’” Trombetta said. “He told me he had to be gelded. He said forget that first race. I remember the conversation. He said, “`Trust me—he’s a good horse.’” Sweetnorthernsaint lived up to his reputation when he arrived at Trombetta’s barn. “He was very difficult to handle,” Trombetta said. “He had a mean streak. He would kick you. He was more worried about being ornery than doing what he was supposed to do.” Sweetnorthernsaint calmed down a bit after he was gelded and won his debut in a maiden $40,000 dirt claimer at Laurel, only to be disqualified and placed fourth. “He bumped another horse leaving the gate,” Trombetta said. “If it happened today, I don’t think they would have taken him down. They did me a favor. We went to New York in his second start, and he broke his maiden for twice the purse.” Sweetnorthernsaint won that maiden race at Aqueduct by 7 ¾ lengths on and followed that with a 10-length victory in the Miracle Wood Stakes a month later, giving Trombetta his first Kentucky Derby contender. Sweetnorthernsaint then finished third by three-quarters of a length in the Gr3 Gotham Stakes, March 18. Still needing more graded stakes entries to get into the Derby—before the current point system was in place—he sent Sweetnorthernsaint to the Gr2 Illinois Derby. He won by 9 ¼ lengths as the 6-5 favorite on April 8. One month later, he went off as the 5-1 favorite in the 2006 Kentucky Derby, captured by the unbeaten Barbaro. Sweetnorthernsaint normally raced on or near the lead, but he got away 12th in the 20-horse Derby. “He didn’t get away good, and he had to fight to move up,” Trombetta said. “He used a lot of energy to get back into the race.” He had indeed, rallying to get into third at one point, before fading to seventh. He bounced back to finish second by 5 ¼ lengths to Bernardini in the Preakness and went on to earn just under $850,000 in his career. “Sweetnorthernsaint was a disaster at two, and he was a good horse at three,” Trombetta said. “He just needed some time.” Trombetta is great at that, and he enjoyed the challenge. “My enjoyment is watching a young horse mold himself to be good for everybody,” he said. “Sometimes it works out, sometimes it doesn’t. They’re all individuals. If you treat every horse individually, they’ll be better off. Some take longer than others. I’ve been fortunate. I get to work for some really good owners. It takes a lot of time to get where you want to be. They want what’s best for the horses. I’m blessed.” Actually, Johnson, who has an accounting firm in the Washington, D.C., area and Legacy Farm in Bluemont, Va., feels blessed to have his horses—many of them home-breds—trained by Trombetta. “He’s a remarkable worker, a terrific horseman, completely honest and candid,” Johnson said. “He does a marvelous job of developing young horses. Consistently. He’s been able to get and maintain terrific help. There’s no slippage; nothing gets lost between the cracks because of the people he has.” Johnson, who’s been with Trombetta for 21 years, met him by selling him a filly for $900 in a 1989 sale at Timonium. “Wiith crooked legs,” Johnson said. They didn’t seem to matter. That filly, Overdue Ghost, posted eight victories and two seconds in 12 starts, earning $96,510.Johnson was duly impressed with the 23-year-old trainer. “He was just a kid, but he knew what he was doing,” Johnson said. “Training horses is 24/7. It’s tough to do that job and construction, which is also 24/7.”After she was done racing, Overdue Ghost’s foal, Ghostly Numbers, won 10 of 34 starts and made more than $280,000. Another Johnson horse, Partners Due, won six of 21 starts and earned $239,345. “Then we sold her at Keeneland for $320,000,” Johnson said. A pair of 2004 foals, Street Magician and Strike the Moon, were two more success stories. Street Magician won five of 10 starts and made $254,440. Strike the Moon posted five wins, nine seconds and five thirds in 24 starts, earning $680,170. In 2019, Live Oak Plantation’s home-bred three-year-old Win Win Win captured the Pasco Stakes at Tampa Bay Downs by 7 ¼ lengths, finished second in the Blue Grass Stakes, third in the Tampa Bay Derby, ninth in the Kentucky Derby and seventh in the Preakness Stakes. He then won his turf debut in the Manila Stakes at Belmont Park in July—his final start in his three-year-old season. Trombetta had hoped Independence Hall would take him back to the Kentucky Derby in 2020 after he finished fifth by one length in the Gr1 Florida Derby.Instead, he was sidelined with injuries and then his owners, Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners, Twin Creek Racing and Kathleen and Robert Verratti, decided to switch trainers, hiring Mike McCarthy. Independence Hall returned to win an allowance race/optional $100,000 claimer last November 9. In four subsequent starts in graded stakes, he’s finished fifth, third, fourth and third.Losing talented horses is part of horse racing. Trombetta moved on. His top horses this year include Larry Johnson’s five-year-old mare Never Enough Time, who’s earned more than $275,000 off five victories in 13 starts, and Three Diamond Farm’s four-year-old filly Kiss the Girl, whose four victories in 13 starts have led to more than $220,000 in earnings. Forever uncomfortable talking about himself, Trombetta said his success has happened “because we had very good horses. We had the right horses. Things fell into place.” They have for quite a long time in his care. “Mike takes it real serious,” his brother said. “He puts his heart and soul into it. But he’s very low-key talking about himself. He’s pure class.” Asked if he was surprised by Trombetta’s continuing success, Johnson said, “Not at all. It was inevitable. Graham Motion is a good friend of mine. I put him in the same category.” ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1627049051412-KRCRWBOM2I1M1Y1AYZMV/z210628_eclipsesportswire__00727.jpg)

![Claude 'Shug' McGaughey IIIBy Bill Heller Sustained excellence is a rare commodity in any endeavor, even more so in Thoroughbred racing when success is tied to 1,000-pound horses traveling 35 miles per hour, guided by jockeys making rapid strategic decisions one after another. “For every good thing that happens, 20 bad things happen,” Hall of Fame trainer Frank Whiteley advised his young assistant, Shug McGaughey, decades ago. McGaughey didn’t listen, made it into the Hall of Fame, and continues to succeed. He recently turned 70, and his horses have earned more than $2 million for 37 straight years, thanks to a win percentage of 21 at the highest level of racing. GREATEST HONOURHe won one Kentucky Derby with Orb in 2013—the best victory of all for a Lexington native. And he hoped to do it again this year with Courtlandt Farm’s Greatest Honour, who fired off consecutive victories in the Holy Bull Stakes and the Fountain of Youth Stakes before finishing third in the Florida Derby as the 4-5 favorite. Doing the right thing for your horse is easier when he’s doing well but much more difficult when he isn’t. McGaughey noticed something wrong with Greatest Honour and acted accordingly. “I wasn’t pleased with the way he galloped Saturday and Sunday,” Reported Shug on Thursday, April 8. “I said on Monday, `We have to get to the bottom of this.’” That meant X-rays, a bone scan and consulting with Dr. Larry Bramlage, who has always been close to Shug’s heart. Bramlage’s successful surgery on Personal Ensign when she suffered a broken pastern as a two-year-old allowed her to come back at three to resume her historic, unblemished career, culminating with her victory in the 1988 Breeders’ Cup Distaff.McGaughey said Greatest Honour had a minor problem in his ankle which wouldn’t require surgery. On Wednesday, April 7, just 24 days before the Kentucky Derby, McGaughey announced that Greatest Honour would get 30 days off at Courtlandt Farms and then be re-evaluated, hopefully in time for him to race in the midsummer Derby— the Travers at Saratoga. “We just need to give him a little time. I feel bad for Don Adam [the owner of Courtlandt Farms] and for the horse.”McGaughey had to make that difficult phone call to Adam to tell him the bad news. “It’s not easy, but I’ve made that call a lot of times,” As Shug put it. “It’s part of the game.”Greatest Honour would have been one of the top contenders in the Triple Crown series. By doing the right thing, McGaughey is allowing Greatest Honour to reach his potential, no matter how much McGaughey wanted to win another 3yo classic race. The challenge of getting Greatest Honour back to the winner’s circle is one McGaughey has enjoyed his whole career. “I enjoy the horses, the competition, the clients; I don’t enjoy the politics in racing today. It makes it hard to keep focused on training: the visas, the cost of workman’s comp, knowing how far out you can give horses medication. Certain states have certain rules. Other states are different. I will be happy when we get some kind of uniformity.” Thanks to the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act, that is about to happen. “I think the Horseracing Integrity Act is a good thing; it’s definitely a good thing. We weren’t going to do it ourselves. We tried policing ourselves, and it didn’t work.” What has worked for McGaughey is letting his horses earn their way into major stakes by their performances. Greatest Honour would have been only McGaughey’s ninth starter in the Kentucky Derby. “He doesn’t put a horse in a race just to have a horse in a race,” his 34-year-old son Chip, an administrator at Keeneland, said. “He wakes up every morning and goes to sleep every night thinking about his horses. He wakes up in the middle of the night thinking about his horses. He has dedication to getting everything he can out of his horses by developing them. His training philosophy has always been doing what’s best for his horses. He’s always had that. He is a very patient trainer, allowing a horse to tell him what the next step is.” LET THE HORSES TALKMcGaughey said, “I think the biggest thing is you have to watch them and let them tell you what’s going on. I try not to wake them up too soon. I like to see them go well within themselves. I tell the exercise riders not to get them tired when they work them. I don’t want to overdo it. I want to teach them how to run, breeze them up in company, breeze them behind horses, a half in :50 or :51. They get enough out of the workout.”Reeve, Chip’s 31-year-old brother, who is off to a promising start on his own training career, saw Shug’s approach first-hand, working for his dad after stints with Eion Harty and Reeve’s uncle, Charlie LoPresti: “There are only a handful of guys who have sustained excellence for the duration of his career, he works hard. He’s a very good trainer. Obviously, what’s worked for him has worked for him for a very long time. It helps to get good horses.”It helps even more to get good horses with patient owners. Asked if he enjoys the process of understanding horses as individuals, McGaughey said, “Very much so. That’s the way I sort of centered my career around: try to develop good horses. One of my big breaks was working for Loblolly, and that’s what they wanted. Then I stepped into the Phipps job, and also Stuart Janney. That’s what they were interested in, trying to develop a nice horse that can compete in big races. All the people I train for—that’s what they want: getting a horse to stakes quality.”And winning with them. That’s what great trainers do. Their work ethic is a given. Long hours. An open mind is a decided asset. “I think that you’re still learning; you see something new almost every day. I don’t know if I’m a better trainer, but I understand it more. I think you understand the game better placing horses. I know when I was young, I thought they should win every race. If they didn’t, I thought it was my fault. Now I understand the circumstances of the race. You can get in trouble. You might not be in the right place. You can get stopped.”McGaughey hasn’t stopped attacking his profession. “That son of a gun is like the Energizer bunny,” Shug’s wife Allison said. “He works his butt off. He lives, eats and sleeps those horses. I’m younger than him, and I don’t know how he does it. He gets up at 4:30ish, leaves the house around 5, 5:15. Works at the barn til 11. Maybe plays a little golf, showers and goes back to the barn. He wants to be at the barn all day, run them and go back to the barn. It’s like a constant, non-stop. Won’t go out to dinner if there’s a horse to cool out or he’s waiting for a shipper to arrive. I say, `Why don’t you take it easy?’ ‘No.’ Why don’t you take a nap?’ ‘No.’ Why don’t you take a vacation?’ ‘No.’ But we enjoy it.”She enjoys the races a bit differently than Shug. “I get very excited; I like to yell. And his thing is, he takes them over there. He wants them to run well. If they don’t, he wants to work it out. If he runs well, he’s already thinking what the next start is. I’m more in the moment.” LOOKING BACKMcGaughey’s happiest moments include Personal Ensign’s last-gasp nose victory under Hall of Famer Randy Romero in the 1988 Breeders’ Cup Distaff at Churchill Downs to retire undefeated—a race chosen by fans in 2009 as the most exciting Breeders’ Cup race in its first 25 years. “I thought she was hopelessly beaten,” said McGaughey. Instead, she won, retiring as the first major undefeated horse with at least 10 starts since Colin, who retired with a 15-for-15 mark in 1908. No horse has done it since Personal Ensign, so it’s now 113 years. McGaughey’s saddest moment came 18 years later, in the same race—the 2006 Breeders’ Cup Distaff, at the same track—Churchill Downs. McGaughey’s three-year-old filly Pine Island, who had won the Gr1 Alabama and Gazelle Stakes, suffered a fatal injury early in the race. “This was the worst; it’s bad when it happens at Aqueduct. It’s not that easy to say, but I’ve always tried not to let myself get too close to them because I know this is something that can happen. They can be here today and gone tomorrow. When the newspaper arrived, I told them to put it in the trash. I didn’t want to see the pictures.”There were many more happy pictures than sad as McGaughey churned out one talented Thoroughbred after another. Shug’s nine victories in the Breeders’ Cup are topped only by D. Wayne Lukas and Bob Baffert. Fourteen of McGaughey’s horses earned more than $1.5 million. Eight of those topped $2 million. Their common denominator was treating out-of-money finishes as if they were the plague. Personal Ensign’s 13-for-13 set the bar impossibly high, but McGaughey’s Easy Goer, Inside Information, and Heavenly Prize, never finished worse than third. Inside Information was 14-for-17 with one second and a pair of thirds. Heavenly Prize, whose losses included a lopsided one to Inside Information in the Breeders’ Cup Distaff, was nine-for-18 with six seconds and three thirds. Easy Goer was 14-for-20 with five seconds and one third, and earnings of $4,873,770, over $2 million more than any of McGaughey’s horses.THE EARLY YEARSBut McGaughey’s life could have been much different. His family was in the laundry and dry cleaning business in Lexington. McGaughey was 12 or 13 when his dad took him to Keeneland. Soon, McGaughey and his buddies were sneaking into Keeneland. “I’d pick up the Daily Racing Form from the people who had taken out just the Keeneland PPs and bring the rest of it home. I’d read the articles and maybe look at the horses that were running at Arlington.”McGaughey got a job with trainer David Carr, a brother-in-law of one of his friends. “I became enthralled with the whole atmosphere. I mean I really enjoyed it. I enjoyed being around the barn. I enjoyed the after hours. When the work was done in the morning, I’d like to hang around. They were teaching me, and I was intrigued. If anything had to be done, I always wanted to be there to watch. I was always looking over the veterinarian’s shoulder. I felt that if I ever had to do it by myself, I wouldn’t want anyone standing over my shoulder and telling me what to do. I wanted to be able to make those decisions by myself.”When he decided to move on, he landed a job with Frank Whiteley in South Carolina. Ignoring Whiteley’s career advice, McGaughey went into training. Judging by his $154 million in career earnings—10th highest of all time and his 20 horses who have won at least one Gr1 stakes—he’s done all right.Catching on with John Ed Anthony’s Loblolly Stable was a huge break for McGaughey, and he made the most of it, guiding Vanlandingham to an Eclipse Award as the 1985 Champion Handicap Horse. He also guaranteed a painful decision by McGaughey: to leave Loblolly and accept an offer to train for the Phipps family. “John Ed Anthony was very, very good to me; I think he was stunned. It was a very, very difficult thing for me to tell him.” THE PHIPPS YEARSHere’s how it happened on October 5, 1985: McGaughey journeyed to Dinny Phipps’ home in Old Westbury, Long Island, to interview that morning to take over as the Phipps family’s trainer. “I was scared to death, but he immediately put me at ease.” The interview went well. “I felt like I was going to get the job,” said McGaughey.That afternoon at Belmont Park, Vanlandingham won the Gr1 Jockey Club Gold Cup by 2 ½ lengths under Pat Day. Dinny, the chairman of the Jockey Club, presented the winning trophy to McGaughey. How’s that for a deal closer? Shug was hired four days later and has been training for the Phipps ever since. “We had a wonderful relationship for years; they not only made my career, they made my life, too.”Dinny passed April 6, 2016, at the age of 75. “I still have eight or nine of their horses in training and some two-year-olds and foals; they’re trying to keep it going.”DEVELOPING A DYNASTYAfter hiring McGaughey, Dinny Phipps explained to his new trainer that the foundation of the racing stable is based around broodmares. And to be good broodmares, they had to perform on the racetrack. Some trainers are better training fillies. In the Phipps operation, you had to be able to train fillies.McGaughey didn’t wait long to address that concern. Twelve days short of a year after he was hired, McGaughey unveiled Personal Ensign, who won her debut by 12 ¾ lengths, then the Gr1 Frizette by a head. She was the personification of McGaughey’s career, coming back from ankle surgery after the Frizette was thought to be career-ending. Instead, she returned, was managed brilliantly by McGaughey and resumed her unforgettable career. She eased back into Gr1 competition and punctuated her perfect career by running down loose-on-the-lead Kentucky Derby winner Winning Colors at Churchill Downs—a track Personal Ensign had never raced on—to finish 13-for-13. “That was going to be her last race,” McGaughey said.But she wasn’t done, producing Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Filly winner My Flag, a daughter of Easy Goer, who got up in the final strides to win the 1995 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Filly. It had to feel like déjà vu—a horrible version of one—for Winning Song’s trainer D. Wayne Lukas, who also trained the two fillies that My Flag ran down seven years later: Cara Rafaela and Golden Attraction. As a three-year-old, My Flag finished third in the Belmont Stakes. She then produced Storm Flag Flying—the 2002 Champion Two-Year-Old Filly whose four-for-four season culminated with a half-length score in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Filly. Three generations of Breeders’ Cup winners over a 14-year period. Patience can pay off. Personal Ensign’s brother Personal Flag won the 1988 Gr1 Suburban and earned more than $1.2 million in his career. McGaughey’s Seeking the Gold posted eight victories, including the 1988 Gr1 Super Derby, and six seconds in 15 career starts, earning more than $2.3 million. In 1989, Easy Goer, the 1988 Two-Year-Old Champion Colt, avenged his losses to his nemesis Sunday Silence in the Kentucky Derby and Preakness by denying him the Triple Crown, winning the Belmont Stakes by eight lengths. Easy Goer added the Whitney Handicap, Travers, Woodward and Jockey Club Gold Cup before losing to Sunday Silence again—this time by a neck in the Breeders’ Cup Classic—a result that cost Easy Goer the Three-Year-Old Colt Championship and Horse of the Year honors. Even with three losses to Sunday Silence, Easy Goer finished his career 14 of 20 with five seconds, one third and earnings of $4,873,770—McGaughey’s top money maker by more than $2 million.Rhythm, the 1989 Two-Year-Old Champion Colt, gave McGaughey consecutive victories in the Travers, winning the 1990 Mid-Summer Derby by 3 ½ lengths before losing his final seven races.McGaughey celebrated another Travers victory in 1998 with Coronado’s Quest, a head case who had tested even McGaughey’s patience, occasionally freezing on the way to the track. Following up on his victory over Belmont Stakes winner Victory Gallop in the Gr1 Haskell at Monmouth, Coronado’s Quest defeated him again in the Travers. Asked if Coronado’s Quest was his most difficult horse to train, McGaughey answered, “For a star horse, yes. It just took us a while to understand him. The Travers was really special—to win a race like that at Saratoga stretching out to a mile and a quarter. I give Mike Smith a lot of credit for that.” Coronado’s Quest finished 10-for-17 with earnings topping $2 million.On September 15, 1993, at Belmont Park, McGaughey unveiled two incredible two-year-old filly Phipps’ home-breds an hour apart. Inside Information won her debut by 7 ½ lengths in 1:11 3/5 under Mike Smith in the third race. In the fifth race, also under Mike Smith, Heavenly Prize won by nine lengths in 1:10 4/5.The two fillies’ careers then diverged. Inside Information finished third in an allowance race and didn’t start again as a two-year-old. Heavenly Prize won the Gr1 Frizette by seven lengths but lost the Two-Year-Old Filly Championship when she finished third by three lengths to Phone Chatter in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Filly. As a three-year-old, Heavenly Prize won the Gr1 Alabama by seven lengths, the Gr1 Gazelle by 6 ½ and the Gr1 Beldame by six lengths. Though she lost the Breeders’ Cup Distaff by a neck to One Dreamer, Heavenly Prize won the Three-Year-Old Filly Eclipse. At four, Heavenly Prize won four consecutive Gr1 stakes: the Apple Blossom at Oaklawn Park, the Hempstead at Belmont Park, and the Go for Wand and John A. Morris at Saratoga. In the Breeders’ Cup Distaff, she finished second by 13 ½ lengths to her incredible stable mate Inside Information.Inside Information won 13 of her 15 starts as a three- and four-year-old, the lone misses a distant third to Lakeway in the Gr1 Mother Goose and a non-threatening second to Classy Mirage in the Gr1 Ballerina. Inside Information won the Gr1 Ashland and Acorn Stakes as a three-year-old. At four, she captured the Gr1 Shuvee, the Ruffian by 11 lengths, the Spinster by a head and, in as dominant fashion as a race can be, the final start of her career: the Breeders’ Cup Distaff by 13 ½ lengths. Mike Smith rode Inside Information in 16 of her 17 starts. José Santos was aboard when she won the Shuvee by 5 ½ lengths.Lest McGaughey be classified as a top dirt trainer, two horses 20 years apart proved McGaughey’s prowess with grass horses. The speedy Lure posted 11 victories, including back-to-back victories in the Gr1 Breeders’ Cup Mile in 1992 and 1993. In 18 grass starts, Lure posted 11 victories and six seconds, earning $2,515,289.Twenty years later, the powerful closer Point of Entry—who rallied from 26 lengths behind to win an allowance race by a length and a quarter—captured five Gr1 stakes: the Man o’ War, Sword Dancer, Turf Classic Invitational, the Gulfstream Park Turf Handicap and the Manhattan. In two starts in the Breeders’ Cup Turf, Point of Entry finished second by a half-length to Little Mike in 2012 and fourth by 1 ¾ lengths to Magician in 2013. He made $2,494,490. Then came Orb, who made $2,612,516. “Orb was just a special, special thing—me being from Kentucky—to win the Kentucky Derby for the Phipps[es] and Stuart Janney was special. Going there to Louisville with the favorite for the Derby was a very special week for Allison and myself. We did enjoy it very much.” He expected to enjoy the Preakness, too. “He came out of the Derby very well; he had a good work before we went to Pimlico. But he drew inside when he wanted to be outside. He finished fourth. He was a victim of circumstances. I was disappointed. I would have loved to bring him to Belmont—a special place for me—to have a chance to win the Triple Crown at Belmont. That’s my favorite place to train. I’m comfortable there. There’s nobody else in my barn. It makes it easier. It’s not real busy. And I love a big racetrack.”Honor Code—a gorgeous black closer who was from the last crop of A.P. Indy out of Serena’s Cat by Storm Cat—was McGaughey’s next star. He only raced 11 times but made the most of it with six victories, including two emphatic 2015 Gr1 scores in the Met Mile, when he made an astounding rally to win going away, and the Gr1 Whitney. He finished his career by running third to American Pharoah in the Breeders’ Cup Classic, earning just over $2.5 million. Will Farish’s home-bred Code of Honor stamped himself as a top Kentucky Derby contender by winning the 2019 Gr2 Fountain of Youth. He finished third to Maximum Security in the Gr1 Florida Derby then gave McGaughey quite a thrill in the Kentucky Derby, making a bold move on the inside of Maximum Security as if he’d spurt by him coming out of the far turn. “There was a second and a half it looked like he was going to win,” Shug’s son Reeve said. “Then he lost his momentum.” Still, Code of Honor finished third and was moved up to second when Maximum Security became the first horse ever disqualified from a Kentucky Derby victory.Code of Honor came right back to win the Gr3 Dwyer, the Gr1 Travers and the Gr1 Jockey Club Gold Cup. He then finished seventh to Vino Rosso in the Breeders’ Cup Classic. After a seven-month vacation, Code of Honor returned to win the Gr3 Westchester. It was his last victory to date. He finished third in the Gr1 Met Mile, fourth in the Gr1 Whitney, second in the Gr2 Kelso, second in the Gr1 Clark and, in his last start on January 23, 2021, fifth in the 2021 Pegasus World Cup. LOOKING FORWARDGreatest Honour is poised to join McGaughey’s most accomplished horses when he returns. The son of Tapit is out of Better Than Honour, who has produced two Belmont Stakes winners: Jazil and Rags to Riches. “With his pedigree, the further he goes, the better for him.”Earlier on the Florida Derby card, Allen Stable’s three-year-old filly No Ordinary Time won a maiden race by a neck under Julien Leparoux for Shug. She was shipped to New York to make her next start. Shug might have another top three-year-old. Will Farish’s Bears Watching was mighty impressive, winning a seven-furlong maiden race by 7 ¾ lengths March 13, but he too is being freshened. “I had to stop on him too; he had a little chip in his ankle. He’ll be out for 30 days.”Shug will develop his horses the way he always has—prudently. It’s what made Shug a Hall of Famer. “Of course I’m proud of him, but not all of his accomplishments are in racing,” Allison said. “He’s a great guy—very kind, very understanding. He’s fun. We have a great relationship. We go fishing together. We golf together.” And now, Shug and Allison have a new member in their family. Chip and his wife Jenny have a baby daughter, Lily, who was born on February 2. She is Shug’s first grandchild. “She lives in Lexington, and we’re looking forward to meeting her.” Is Shug ready to be a granddad? “He’s mellowed a little bit,” Reeve said. “He’s still working every day, but he might take off a day or two. He needs to ease back and try to enjoy life a little bit more.” Lily may just make that happen for Shug. She may require patience, but her accomplished grandpa knows all about that.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1619185270908-34LKUMNTZJULHFJ5T31Q/_Z9A6617.jpg)

![Barbara Bankeby Denise SteffanusStonestreet Farm's mission is to produce winning racehorses with "strength, stamina, and class"—three attributes that also describe Barbara Banke, Stonestreet’s vibrant owner.In 2011, Banke took over Stonestreet's reins when her husband, Jess Stonestreet Jackson, died at age 81 from cancer. A worthy successor, Banke had worked shoulder to shoulder with Jackson as the two built their empire of fine wines and fast horses, including Horses of the Year Curlin (twice) and Rachel Alexandra, who together earned a combined six Eclipse Awards.Under her leadership, Stonestreet has won 35 graded stakes as Stonestreet Stables and has shared 15 graded stakes wins with 45 partnerships through the end of September. Stonestreet has been the leading breeder of yearlings at auction for the past five years.Banke also became chairman and proprietor of Kendall-Jackson Wines (now Jackson Family Wines)—an international domain of wineries based largely in California and extending to Oregon, Chile, Australia, France, Italy, and South Africa. Jackson wines graced tables in the White House during the Reagan administration when Nancy Reagan offered her favorite wine, Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay, to distinguished guests from around the world.Banke wasn't the typical horse-crazy girl while growing up. She remembers going on a few trail rides, but her involvement with horses began in 2005 when she suggested Jackson find something to absorb his boundless energy."I just felt that he needed some hobby because he was sort of driving us all crazy around the winery from being a micromanager. (Banke laughs.) He had been in the horse business with his uncle a while before that. He really wanted to get back into it," she said.The two founded Stonestreet and purchased an Unbridled's Song filly, Forest Music, in the summer of 2005 and turned her over to trainer Steve Asmussen. In her first start for Stonestreet, she went gate to wire in the Gr2 Honorable Miss Handicap at Saratoga, giving Stonestreet its first graded stakes winner. After the race, Asmussen prophetically told the media that it was "a sign of things to come."Asmussen certainly was right about that.Plunging head first into the racing industry, Stonestreet purchased Buckram Oaks Farm—450 acres of prime bluegrass land outside of Lexington—for $17.5 million that same year and renamed it Stonestreet Farm. Months later, Stonestreet purchased 650 acres in Versailles, Ky., and established a yearling division there.When asked why the Buckram Oaks parcel appealed to her, Banke, who litigated land-use cases before the United States Supreme Court and Court of Appeals in her former profession, did not give the expected answer citing investment strategies, the spring-fed limestone ponds coveted for raising horses with good bone, and other legal points."It’s a beautiful, beautiful place," she said. "And it’s really convenient because it’s close to Keeneland (Racecourse and Sales) and close to town; and it’s very scenic. The barns were beautiful. The ponds were beautiful. So it had a lot of improvements, and it was something that we thought would be a good home in Kentucky. I’m really glad now that we went there."Broodmare BandStonestreet started to populate its broodmare band, with an eye to transition its fine racemares into outstanding breeding stock of future Stonestreet runners and sale prospects. Banke called her strategy "mare-centric" and said, "That’s our focus, and that’s really fun. It’s fun to raise fillies for me because I know that they have a great career when they’re finished. It’s a nice thing to do."Retired from racing at the end of 2005, Forest Music became the cornerstone of Stonestreet's breeding operation, producing graded stakes winners Kentuckian, Electric Forest, and Uncle Chuck, plus winner MacLean's Music—who sired 2017 Gr1 Preakness Stakes winner Cloud Computing in his first crop—plus three other graded stakes winners.Banke called Stonestreet's broodmare band "unparalleled," and the names on the roster are a stellar list: homebreds My Miss Aurelia, 2011 champion two-year-old filly; Lady Aurelia, 2016 Cartier Two-Year-Old Filly of the Year in Europe; and Gr1 winners Dreaming of Julia, Tara's Tango, and Rachel's Valentina (daughter of now-pensioned Rachel Alexandra).Among the other broodmares: Bounding (Aus), New Zealand’s champion sprinter and champion three-year-old filly in 2013; D' Wildcat Speed, Puerto Rican Horse of the Year and champion imported three-year-old filly in 2003 and the dam of Lady Aurelia; Dayatthespa, 2014 champion female turf horse; Hillaby, 2014 Canadian champion female sprinter; and eight other Gr1 or Gp1 winners.Seventeen of Stonestreet's broodmares have produced graded-stakes winners. The latest starlet is Gamine, the three-year-old Into Mischief filly out of Banke's mare Peggy Jane. Conditioned by two-time Triple Crown-winning trainer Bob Baffert, Gamine won the Gr1 Acorn Stakes by an incredible 18-3/4 lengths in 1:32.55, slashing the stakes record time of 1:33.58 and just a fifth of a second slower than the track record of 1:32.24 for the mile. Next she took the Gr1 Test Stakes by seven lengths, installing her as the 7-to-10 favorite going into the Gr1 Kentucky Oaks, where she finished third after a tough stretch duel with winner Shedaresthedevil. The Oaks was Gamine's first two-turn race.Ready to Repeat, a More Than Ready gelding produced by Stonestreet's Christine Daae, placed in the Gr1 Summer Stakes over the turf at Woodbine in Canada on September 20. After maintaining a comfortable lead all the way to the stretch, eventual winner Gretsky the Great cut in front of Ready to Repeat, causing the gelding to change course. Stewards disallowed a claim of foul. Banke sold Ready to Repeat for $60,000 at the 2019 Keeneland September Yearling sale.Banke is excited about Stonestreet's Irish filly, Campanelle, who is expected to join the band at the end of her racing career. Banke gave $243,773 for the Kodiac (GB) filly at the 2019 Tattersalls October Yearling Sale."[Barbara Banke] loves coming to Royal Ascot every year, and she wanted to buy two or three fillies who could run there," said Stonestreet's agent Ben McElroy. "Campanelle looked like she'd fit the bill, and she did."Undefeated in three starts, Campanelle earned a Breeders' Cup "Win and You're In" berth when in August she won the Gr1 Darley Prix Morny—Finale des Darley Series in France. She is expected to start in the Gr1 Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf on November 6 at Keeneland, her home track."We bought her as a yearling, and she’s now a Gp1 winner in Europe," Banke said. "And she’s going to be a great broodmare in her future, hopefully a long way from now."Banke's philosophy is simple: "We try to get the best mares, or if we don’t buy the best mares, we try to buy the best fillies and race them and go from there. And, of course, then we breed them to great stallions," Banke said.Although Stonestreet does not maintain a stallion division, it holds interests in eight stallions: leading sire Curlin and his sons Jess's Dream, out of Rachel Alexandra, Union Jackson, out of Hot Dixie Chic, and 2017 champion two-year-old Good Magic, out of Glinda the Good; Racing Hall of Fame member Ghostzapper, 2004's Horse of the Year and champion older horse; Gr1 winners Carpe Diem (2015 Blue Grass Stakes) and The Factor (2011 Malibu Stakes); and multiple-graded stakes winner Kantharos.Banke said that, at present, she has no interest in standing stallions. But she added, "Maybe. Never say never."The stallions in which she owns an interest are spread among several well-respected farms that specialize in standing stallions. Each of those farms, in turn, has developed its own client base over the years to which they promote the stallions, in addition to running ads designed to attract newcomers into the Thoroughbred industry."A lot of these places have great clientele. It’s a whole focus area," said Banke. "Not that we couldn’t do it, but it would require a different orientation on our part."We have a very good relationship with the stallion farms that stand our horses. It’s a different type of business; you have to have a different level of staffing. …We compensate the stallion barns for standing the horse, and usually it works out better if the stallion barn has an interest in the horse. So that’s worked for us with all of them," she said.In the 10 years since Banke took over Stonestreet, she has sold 470 yearlings at auction for gross receipts of $108,828,200. Stonestreet has dominated the market as leading breeder of yearlings for six of the last seven years, and second-leading breeder in 2015. Stonestreet has topped the overall breeders list for the past three years. Its gray Tapit colt out of Tara's Tango was the sale topper at this year's Keeneland September Yearling Sale when the hammer fell for $2 million.Testing for SaleBanke was perplexed by reports that bisphosphonate—a drug to combat fractures in humans with osteoporosis—was being administered to young racing prospects destined for sale. When she learned that testing could only detect the drug if it had been administered within 30 days, Banke sought a way to assure buyers that Stonestreet’s sale horses were raised free of bisphosphonate and other hidden drugs."We’re trying to raise racehorses," Banke said. "We don’t want to raise them for looks necessarily, although obviously that’s desirable. We want to raise them for durability, for speed, for the ability to go out and compete. So we don’t want to give them anything that would jeopardize that. Our reputation is very important to us."Banke worked with Dr. Scott Stanley, former director of the University of California's Kenneth L. Maddy Laboratory—which studies the effects of drugs on equine athletes—to design a testing program that would follow Banke’s young horses from February of their yearling year to the sale ring."If we test from the beginning with the horse, and we keep testing until we get to the sale, the buyers could have confidence that these horses had not received anything like that," Banke said.Equine Biological PassportDuring her discussions with Stanley, Banke also learned of his pet project, adapting the principles of the Athlete Biological Passport in human sports to equine sports. The goal of the project is to monitor changes in a horse's biomarkers to detect effects that indicate doping, even if the methods and substances used by a cheater—including so-called designer drugs—are not otherwise detectable.In layman’s terms, testing via a blood sample would establish a baseline level of certain natural peptides and proteins (biomarkers) in the blood. If these levels change in some abnormal fashion in a particular horse, it’s an indication of something going on inside that horse. Stanley said a good analogy is the CBC (complete blood count), where changes in certain factors in the blood indicate conditions or diseases."So instead of developing new tests for every new drug that comes along, which is what we’ve always done, this is a process where we would develop a test for these biomarkers that would be indicative of drugs in those classes," Stanley explained. "So we could look for designer drugs; we could look for new FDA-approved drugs; we could look for old drugs that have been off the market but brought back."In late 2018, Stanley accepted a professorship at the University of Kentucky’s Maxwell Gluck Equine Research Center and brought his project, renamed the Equine Biological Passport, with him. In July 2020, Stonestreet donated $100,000 to further that research.Banke said the project will benefit horses not only in detecting drug use but also in tracking their health over time."Knowing how horses have been treated in the past will inform people at the track as to whether that horse might be at risk, or whether the horse has had different treatments given to it," Banke said. "And then it would be important to facilitate accurate testing for the horses to see if they’ve been given something that is illicit or they may have, on the other hand, [been exposed to] environmental contamination."The rumor of designer drugs overshadows success in the industry. Throughout the history of horseracing, trainers with an exceptional win record have been rumored to have "special juice" that makes their horses run faster and farther. The ability to prove or disprove such rumors would be a giant step to regain the public’s confidence in the sport."That’s important because it gives us an advantage so we can be on the alert for something new because the bad guys seem to be one step ahead of the current testing regimes. So we want to get out in front of it if we can," Banke said. "If you can distinguish between illegal substances and treatment protocols, it will help to preserve the reputation of the good trainers—and most of our trainers are good. I think we need something that will bolster the reputation of horseracing and make everyone aware that we’re trying as best we can to keep it clean."Stanley predicted that it will take about two years to implement the Equine Biological Passport in race testing, during which time regulators will have to adopt rule changes to allow its use to disqualify horses from competition. In the meantime, regulators could implement the program in out-of-competition testing to detect trainers who might be cheating."It could be an application to determine that someone was using something systemically that they shouldn’t," Stanley said. "Then the regulatory body would have the right to go back and test all their horses and find out if they could determine what was being used."Stonestreet Training CenterBanke wants her horses to be raised and developed as naturally as possible, from foal to retiree. On Stonestreet's website, she states:"Our program values minimal human intervention and a good balance of proper nutrition, handling, exercise and rest. We enhance the development of youngstock and strive to exemplify excellence in every action."Until December 2012, the only hole in that lifelong program for her horses was yearling training, and Banke felt that starting her racing prospects properly and bringing them along safely was an important phase over which she wanted more control. Establishing her own training and rehabilitation center in Florida was the answer. So Banke purchased the 230-acre vinery in Summerville, Florida, near Ocala, then added another 120 acres to form Stonestreet Training and Rehabilitation Center. The center also is open to outside horses.The training center has a seven-furlong dirt track, a three-quarter mile turf course, and a European-style turf gallop. Three covered European freestyle walkers, a vibration platform, and an underwater treadmill help young horses to develop their muscles, older horses to freshen up, and layup horses to gently return to normal activities through enhanced rehabilitation techniques.Most of Stonestreet's horses start preparing for their careers at its training center with a staff that specializes in breaking and training youngsters while employing Banke's preferred methods. She emphasizes the advantage of nurturing a competitive spirit in her youngsters by placing them in similarly talented peer groups. A few of Stonestreet's yearlings go elsewhere."Last year we felt we had too many, we kept too many, and we were going to put a few through the two-year-old sale," she said. "We sent one homebred to Eddie Wood; actually, we sent a couple to him to put in the two-year-old sale. And one of them was Cazadero."Wood owns and operates Eddie Wood Training Center in Florida, as well as acts as an agent for two-year-old sales. At the time, he told Banke, "You don’t want to sell this horse." She took his advice.Banke kept the Street Sense colt with Wood for the remainder of his prep work, then sent him off to Asmussen at Churchill Downs in Kentucky. In Cazadero's debut maiden special weight there, he broke on top and obliterated his opponents with a front-running 8-3/4-length win, followed by a win in the Gr3 Bashford Manor Stakes one month later. Banke thanked Wood for his good advice."[Eddie] is fabulous, she said. "It was nice of him to tell us not to sell the horse because the horse would have done very well at that two-year-old sale. Unfortunately, [Cazadero] came up with a little hairline [crack] in his last start (the Gr2 Saratoga Special Stakes on August 7), so he’s off for a little bit, but he’ll be back."As disappointing as that piece of racing luck was, other graduates of Stonestreet Training Center won five graded stakes and four listed stakes in August: Campanelle, Rushing Fall, Red King, Chaos Theory, Joy’s Rocket, Wink, Hendy Woods, Domestic Spending, and Halladay—the War Front colt owned by Harrell Ventures who wired the $400,000 Gr1 Fourstardave Stakes on the turf at Saratoga.About 75 elite runners have come out of the Stonestreet Training Center. The list includes 2019 Horse of the Year Bricks and Mortar—winner of the inaugural Pegasus World Cup Turf and four other grade-one stakes for career earnings of $7,085,650; 2017 champion juvenile Good Magic; dual Eclipse winning female Unique Bella; Preakness Stakes winners Oxbow and Cloud Computing; 2011 Gr1 Breeders' Cup Turf Sprint winner Regally Ready; 2019 Breeders' Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf winners Rushing Fall (2017) and Sharing (2019); plus a roster of Stonestreet's solid runners.Giving BackA large part of Banke's busy schedule is devoted to serving on committees and boards in her two signature industries, plus participation and philanthropic support of a long list of charities and educational initiatives in the community. Banke also is a global ambassador for the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation.She is a member of the Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association, which appointed her to the American Graded Stakes Committee in 2016, a position she continues to serve.In 2013, Banke joined the Board of Trustees of the National Racing Museum and Hall of Fame. Three years later, she accepted her champion filly Rachel Alexandra's induction into the Hall of Fame. Her trainer Steve Asmussen, who campaigned Rachel Alexandra and Curlin, was inducted during the same ceremony.Under her trusteeship, the National Racing Museum and Hall of Fame in 2018 launched a $20-million project to revamp the Saratoga Springs, New York, site with state-of-the-art interactive exhibits, a 360-degree theater screen, and a redesigned website packed with historical information. Banke served on the redesign committee for the project, which was concluded in 2020, with the reopening on September 5.Banke also is a member of the board of directors for the Keeneland Association and the Breeders' Cup Ltd.She served on the Jockey Club Board of Stewards from 2016-2020, during which time she was a featured speaker at its Round Table Conference on Matters Pertaining to Racing on August 13, 2017, in Saratoga Springs. She talked about unifying factions within the sport and the need for standardized rules, medication and testing."To win in the long term, we must demonstrate to both new and future racing fans that our industry acts with integrity and elevated standards of care to protect the health of our athletes," she said. "The morass of conflicting state medication thresholds and rules is too confusing and slow to change."But the challenges and changes coming at us in the racing industry are fast and furious. I admit that I'm not a patient person, but I know that our industry does not have the luxury of time to waste. A robust future is available to us in an increasingly global business environment. We must foster consumer confidence and make the world stand up and take notice of our American horses."We have a great deal to celebrate about the sport of racing, but we must build a strong, unified voice to bolster the global reputation of our American-bred horses. We must craft our narrative and rebuild the foundation of integrity to establish trust with audiences old and new."War on RacingSince 2013, when People for Ethical Treatment of Animals invaded Asmussen's stable with an undercover operative, who manufactured trumped-up lies and fake videos to discredit racing, the industry has been under attack from animal rights activists who want it permanently shuttered. The mainstream media latches onto each reported death on the racetrack, and conspiracy theorists within the industry spin a web around each high-profile medication violation.While the war on racing rages on, the only point that factions within the industry seem to be able to agree on is that racing needs to change if it hopes to survive. Without the public's trust and confidence, horse racing's future will be a short one.Banke's advice is that everyone involved needs to hear out others' views and then compromise on the most workable solution. She said that if we work together, we can get a lot done to improve and preserve racing."I think the federal legislation will pass, and I think it’s a good thing," she said. "I think banning race-day medications would be a good thing, and we’ve taken steps toward that. So I think we need to fit in with the rest of the world. And the rest of the world loves to say that we use race-day medications, and our breed is not quite as strong. But they’re very interested in our broodmares and breeding stock. I think by enhancing our reputation, we can again take the lead in the world because we do so many things very well."She said the key to success is to treat all the athletes who are the backbone of the sport—horses, jockeys, and the people who work with the horses—well. She emphasized sharing viewpoints and actually listening to what others have to say."I think the jockeys have a lot to say, and we need to listen," Banke said. "And we need to make sure everyone is well treated and an advocate for the sport."She also expects transparency from regulators, track management and other entities."I do think people need to listen and hear whatever issues there are, and there are quite a few issues," she said. "And as you go forward, if you have a new track surface or a new maintenance regime or new rules or whatever, they need to listen to the people who are actually in the trenches and try to make the rules work. All of that needs to happen. I think if we can do that more, it will be beneficial for everybody."The Stonestreet LegacyLooking over all the horses that have borne the Stonestreet mantle of excellence, Banke did not hesitate to name her favorite, Curlin. Rachel Alexandra gave her unprecedented thrills when she toyed with the country's best three-year-old colts in the Gr1 Woodward Stakes at Saratoga in 2009; but Curlin impressed her the most.Stonestreet bought a partnership interest in the Smart Strike colt after watching him destroy rivals by 12-3/4 lengths in his debut maiden special weight at Gulfstream Park in 2007."The first one that really, really, really impressed me was Curlin," she said. "And how could you not be impressed? He was just fantastic, and it was fantastic to be a part of his racing career. Trouble free, and he never missed a day of training. He never had a bandage."He was so funny because he would fall asleep in the saddling paddock and take a little nap. He did that in Dubai as there were fireworks going off all around him. Then he woke up and went out and won the race."That race was the world's richest—the $6-million Gr1 Emirates Airline Dubai World Cup in 2008—when he dominated the world's fastest horses in a 7-3/4-length win."We spent a lot of days watching him train over there, and it was just a really magnificent experience," Banke said. "I’d do it again in a hot second if I could get someone to go over there. We’re working on it."Thousands of feature articles and news stories have been written about Banke, who is considered among the world's most prominent and successful women. But she said there is one thing journalists haven't written about her."I’m a good grandma," she said. "I have seven grandchildren and three children. My son and his wife are very prolific. They keep going for a girl, and it hasn’t worked. They have four boys. And my daughter has three. She has twins, and one of the twins is a girl. I love them all, and I say, 'I’m a good grandma.'"A toast is in order. Hoist your Vintner's Reserve Chardonnay to Barbara Banke. Kudos!](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/517636f8e4b0cb4f8c8697ba/1603541759741-HSJ1ZLBPTSUUIQ4PV5RK/20_0917_Barbara+Banke_mw-5712.jpg)