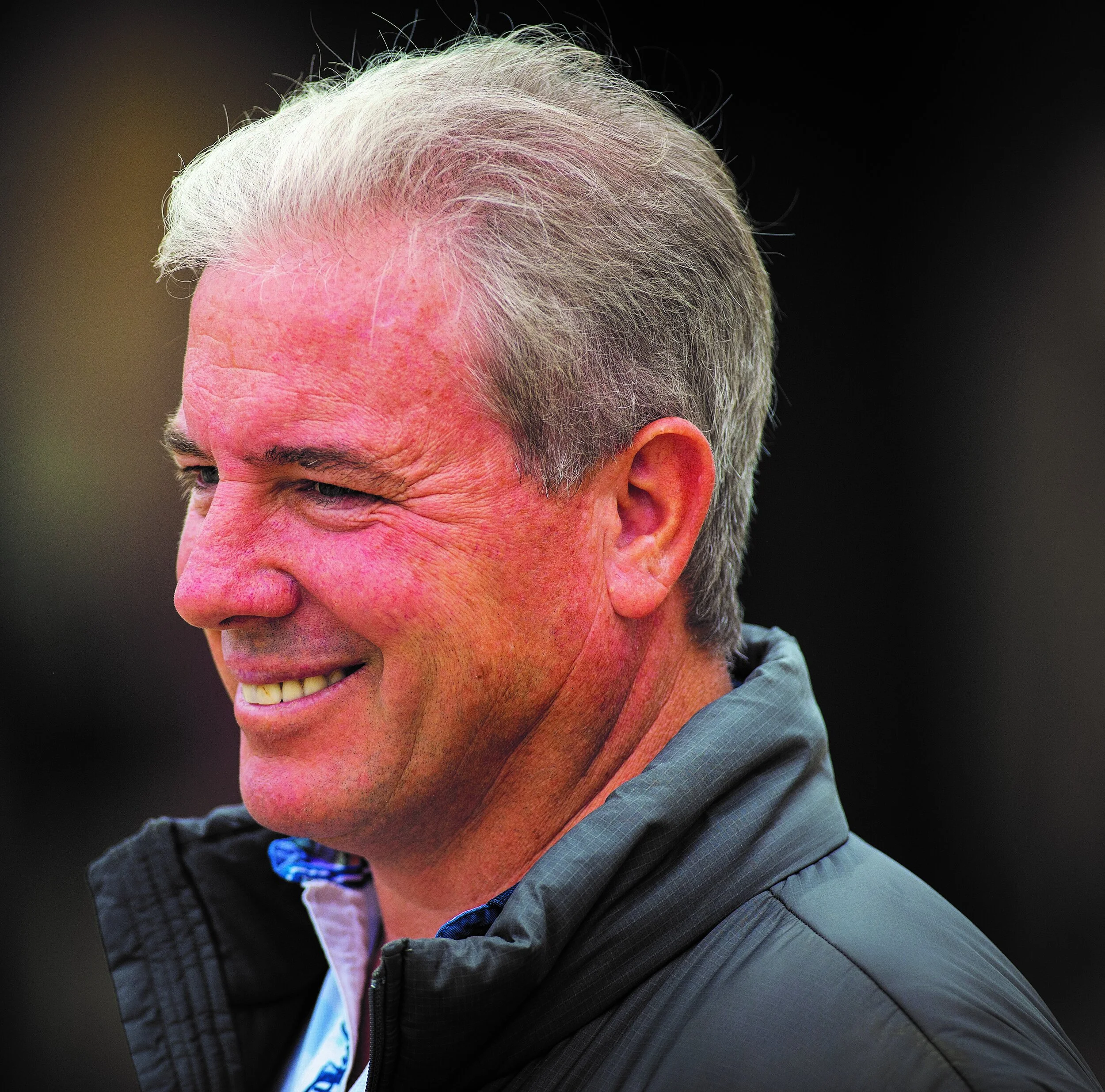

Fausto Gutierrez - The story behind the trainer of Letruska

By Frances J. Karon

“Now I need to start again,” Fausto Gutiérrez says.

Reinventing yourself 35 years into your career is no easy proposition, and not even the man whose name was firmly at the top of the trainers’ standings in Mexico for a decade gets a free pass when he sets up shop on the U.S. side of the border.

Over breakfast at the Keeneland track kitchen in Lexington, Kentucky, one morning in late July, Gutiérrez describes himself as “homeless.” Not, of course, in the literal sense, although these days he’s not been spending much time at home in Florida, where he lives with his wife María and their children Ana, 15, and Andrés, 13.

Instead, he’s traveling with his stable of 11, pointing his compass in whatever direction his star mare Letruska dictates.

This is a drastic change from his previous life in Mexico City, where he’d once maintained a stable of as many as 200 horses at the Hipodromo de las Americas, on a resume highlighted by two Triple Crown winners, both in 2018—Kukulkan and Kutzamala, who won the fillies’ version—and countless champions among countless Graded stakes wins. (To understand more about racing in the country, see sidebar, “A Brief Intro to Racing in Mexico.”)

There’s no publicly available database in Mexico for accessing information or charts more than a month old, but Mexican racing authorities provided a complete record of 20 years’ worth of starts, from 1999 to 2018—which covers only part of Gutiérrez’s career—and in that timeframe, the trainer is credited with 2,261 wins. Add to that figure a cool 100 wins from the 2019 season, which Gutiérrez corroborated with the final standings that were printed in the racing program, and it takes him to 2,361 wins in Mexico. He won, if not all the Graded stakes races in the country, most of them, and he trained at least 19 champions.

Gutiérrez laughs at the suggestion that he’s the Mexican version of Aidan O’Brien. “Mas o menos,” he concedes. More or less. (It should be noted here that although he speaks English, most of the quotations attributed to him have been translated from Spanish.)

“In Mexico, I ran 12, 13, 15 horses in one day, or if there were stakes, 20,” he says. If that sounds exhausting, he agrees with the assessment. “And you know, you get to the day when it’s not about what you win anymore. It’s what you lose. If you win, it’s normal. If you lose, it’s ‘¡Perdió este!’” It’s, This one lost!

Gutiérrez didn’t deliberately leave his life in Mexico City permanently behind when he shipped some of his stable to Florida in late fall of 2019 for the Caribbean Series that December. This annual trek—most recently to Gulfstream Park, but previously to racetracks in Puerto Rico, Panama, and Venezuela—was the norm for Gutiérrez, who always sent a team to run in the black-type stakes restricted to horses trained in member Caribbean regions.

It was his adventurous spirit that took him out of Mexico to begin with, but as the pandemic began to spread and Las Americas shut down for all of 2020, it turned out that there was no racing to go back to.

This wasn’t the first time that racing in the U.S. had provided a safety net for Gutiérrez.

Back in August of 1996, the Mexican government closed Las Americas, the only racetrack in the country, due to a permit dispute. “They kept saying, ‘It’ll open next week,’” he says, but “next week” turned into more than three years. It was a grim situation for the entire racing and breeding industry.

Gutiérrez’s horses were out of action for the second half of 1996 through almost the entirety of 1997 before he had an idea: he’d move his stable to Texas. A couple of other trainers, he says, did the same, but none with as many horses. He loaded up about two dozen, all of them Mexican-breds, and sent them to Laredo. Two didn’t pass quarantine requirements and were denied entry into the U.S., and the rest had to spend an extra three weeks in the middle of nowhere.

Once the horses allowed to cross the border arrived at Sam Houston Race Park, Gutiérrez saddled his first runner. That was in February 1998, when Cuadra Vivian’s Tere Mi Amor ran second in an allowance race off a 21-month layoff. She went on to earn black-type when third in the Tomball Stakes and set a five-furlong track record at Retama Park.

Gutiérrez stayed on the Texas circuit—Lone Star, Retama, and Sam Houston—for nearly two years, having his final runners there in October 1999. He ended the chapter with a win on his last day, when Boldini got to the winner’s circle for the fifth time in the U.S.

But a new-and-improved Las Americas was on the verge of reopening, so Gutiérrez returned home with his claim-depleted stable and prepped for Mexican racing to resume. There was a soft opening in November before a full resumption in March.

Gutiérrez says of his spell in Texas, during which he sent out 11 Mexican-bred winners of 20 races: “It was very important for me because I learned many different things there. There’s no school for trainers. There aren’t written guidelines like with other professions. It’s day to day: what you can see, what you can learn, or what you can invent. It’s all about what you see and what you apply from the people you can watch, so we each have our own system. But in the end, the most important thing is that no two horses are the same. Each horse is different.”

Gutiérrez, 54, didn’t grow up working with horses. He was born in Madrid, where his father was a lawyer with business ties in Spain and Mexico. The family moved back and forth between the two countries several times until Gutiérrez was 13 or 14, when they settled in Mexico City. Although they weren’t involved in horse racing, they did attend the races, where Gutiérrez developed a taste for the sport at Hipodromo de la Zarzuela in Spain and Las Americas in Mexico.

“There’s something about horses that grabs your attention. You know what I’m talking about…the sights, the sounds, the colors, the smell. It calls you, and that’s what I liked most about the racetrack,” he says. When he was about 15, he started studying the form in the newspapers and programs, then he’d go to the track by himself in the afternoons.

One of the opportunities that set Gutiérrez’s career in motion from an early age came when he was in college at the Universidad Anahuac Mexico. He remembers bringing a Thoroughbred auction catalogue with him and placing it beneath his desk on his first day of classes. A professor who happened to have a horse in the sale spotted the catalogue and invited him to come along.

It was a foot in the door, an entrance to a world he’d already started to love. Of course, he went to the sale.

“From there I began to know more people from the horse industry,” Gutiérrez says. Soon afterwards, at 18, he claimed an inexpensive gelding in partnership.

“He was called George Henry. There was a famous John Henry, no?” He laughs. “Well, this was George Henry. So I was very excited. I was a horse owner now. I had a horse! But we ran him 15 days later and he was claimed. He didn’t win and we lost him.”

Nonetheless, Gutiérrez’s enthusiasm only grew from there.

He claimed another horse and, while continuing to attend university, took out his trainer’s license and began to spend more time on the backside of Las Americas. In 1993, a “very special horse arrived in my life,” Gutiérrez says of his acquisition of a four-year-old Bates Motel filly, Mactuta, with some friends. He trained her to win 19 races, 12 of them stakes—all with international black type—and she was his first champion.

It was during this period when, now a college graduate with a degree in communications, Gutiérrez was approached about becoming the racing correspondent for Reforma, a major new daily paper. He felt unqualified to be a writer, but he went ahead and took the job. “It was good money compared to other things, and I could do it from home,” he says. “I had one or two horses and I wrote, and you know what happens when you write for an important newspaper? You have power. It was important, and it helped me. I had a lot of clout at the racetrack.”

Fausto Gutiérrez, Germán Larrea (second from right), Jockey Jose Luis Campos and connections celebrate Igor winning the 2018 Longines Handicap de las Americas

Reforma gave Gutiérrez the best of everything. “It permitted me to continue to go on in racing because otherwise, I would have had to look for a job in communications or at an advertising agency. When you’re young and you have to decide what to do with your life, I could dedicate myself to my hobby, my passion. It was the perfect scenario for me because I wrote for a paper, I got money, and I had a superior horse. Sometimes I even got to write about my horse.”

This idyllic setup was ended by the extended shutdown of Las Americas, when there was no racing to write about and Gutiérrez left Mexico for Texas. While he was in the States, though, he went to Kentucky and attended his first September yearling sale at Keeneland, where he bought a cheap yearling right before he was supposed to catch a flight from Blue Grass Airport across the street. But first he stopped off at the consignor’s barn to see his new purchase. “There was a horse with a lot of blood on his knees and they were hosing him down. I thought, ‘What’s going on here?’ I saw the hip number, and it was mine.”

W.B. Rogers Beasley, then the director of sales at Keeneland, told him in no uncertain terms that even though the horse had been injured while in the care of the consignor, he belonged to Gutiérrez. Beasley, however, offered to try to work something out if the injuries were severe enough. He told Gutiérrez, “All I want is for you to come back and buy another horse next year.”

Gutiérrez kept that promise to Beasley many times over, and then other Mexican connections began to attend the Kentucky sales, too, to bolster the small annual foal crops born in their country.

It was Gutiérrez’s custom of shopping for yearlings in the States that laid the groundwork for his next big break, albeit, as he acknowledges, one that originated in tragic circumstances after the 9/11 terrorist attacks 20 years ago.

“I got a phone call from Germán Larrea. ‘Can you go to Keeneland?’ he asked me. When the airports re-opened, I went on one of the first planes that left.”

Johnny Ortiz ponying Letruska on the Keeneland training track

Thus began Gutiérrez’s association with Larrea, the billionaire who, racing in Mexico under the stable names of both Cuadra San Jorge and Cuadra G L, is the country’s dominant owner. Their affiliation began small, with Gutiérrez getting the lesser horses, until Larrea’s main trainer retired and Gutiérrez took over the primary role, which set him firmly on the path to becoming the country’s preeminent trainer.

But Las Americas was too small to contain his big dreams.

On April 28, 2017—his 50th birthday—Gutiérrez fulfilled one of those dreams: saddling a runner at Keeneland.

He’d looked through the spring meet condition book as soon as it came out to see what races were scheduled on his birthday, found one to target with Grosco, and called Keeneland-based trainer Ignacio Correas IV—who’d had a lot of success training in Argentina before moving to the U.S.—and asked for his help.

Grosco was a Mexican-bred who had been claimed cheaply at Las Americas. The cost of travel, as Gutiérrez remembers it, was around $2,500 to get him to Kentucky, involving a 20-hour van ride from Mexico City to the border, three days of quarantine, and a 24-hour haul from Laredo to Lexington just to run in a $10,000 claiming race.

Why Grosco? It wasn’t so much that he was a particularly good horse but that the dark bay gelding held special meaning for his family. He’d been born at the farm where María Gutiérrez worked, and their son Andrés had helped foal Grosco. As far as Gutiérrez was concerned, it had to be that horse. “I wanted to see him in the Keeneland paddock,” he says.

Grosco ran fifth of six. “¡No importa!” Gutiérrez says. It doesn’t matter! “When you get to Keeneland and you stand in the paddock beneath the trees, you can say, ‘Here I am. I made it.’ It’s important.”

A second dream was fulfilled that same year when the Caribbean Series— alternatively known as the Serie Hipica del Caribe—was contested at Gulfstream instead of at one of the member jurisdiction racetracks where he’d already trained winners, including a Copa Velocidad in 2012 with Epifanio at Camarero in Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory. But Gutiérrez wanted to win on continental U.S. soil. In 2017 and 2018, the series’ first and second years at Gulfstream, he trained Jala Jala and Kukulkan, both Mexican-bred Horses of the Year, to win back-to-back Caribbean Classics for Larrea’s St. George Stable LLC (which is the English translation of Cuadra San Jorge). The same horses followed up with consecutive wins in the Copa Confraternidad del Caribe (recognized by The Jockey Club as the Confraternity Caribbean Cup the year Kukulkan won) for older horses in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Until Letruska, Kukulkan, who in addition to being Horse of the Year was the divisional champion at two and three, was Gutiérrez’s best horse, and the trainer’s ambitious handling of that colt gives good insight into how he would go on to plan Letruska’s 2020 and 2021 campaigns.

After winning the Caribbean Classic, which was Kukulkan’s first-ever line of internationally recognized black-type, by 10¼ lengths three years ago this December to remain undefeated, connections opted to keep the dark bay in Florida, targeting the Gr. 1 Pegasus World Cup Invitational the following January.

“Kukulkan had done everything he needed to do in Mexico,” says Gutiérrez. “Then I had to face reality [in the U.S.], and reality is another thing. That’s why I felt that the Pegasus would be perfect for losing. I didn’t want to lose in a lesser race. I wanted to lose against the best.”

The son of Point Determined was 11th in the Pegasus but stayed in the States afterwards, eventually winning an allowance at Churchill, placing second in a Gr. 3 at Mountaineer, and third in a Listed race at Indiana Downs for Gutiérrez. Kukulkan closed out 2019 with the win in the Confraternity.

More importantly, the U.S. unveiling of St. George’s homebred Letruska, a winner of all six of her starts in Mexico, came in the Copa Invitacional del Caribe, a 10-furlong race for three-year-olds and up, two races after Kukulkan’s Confraternity. The only female entered, Letruska got out in front and never looked back, beating opponents, including older males, by 4¼ lengths.

Gutiérrez was in the process of establishing a small experimental U.S. division, anchored by Kukulkan, who’d already been in the country to begin with, and the up-and-comer Letruska at Palm Meadows Training Center. But as had happened with Kukulkan after the Pegasus 11 months earlier, some of the shine wore off the previously undefeated Letruska when she ran last of 13 in Gulfstream’s Tropical Park Oaks, her only try on grass, at the end of December in her next outing.

Soon thereafter, in February 2020, the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Mexico. The emerging pandemic made a return home difficult when Las Americas stayed closed, and Gutiérrez was lucky to have the small stable he’d brought to Palm Meadows, although he hadn’t yet had a winner on the year. The trainer himself continued to travel between Florida and Mexico until March, when he brought Andrés with him on what was supposed to be a five-day trip. They never went back to Mexico again.

By summer, with racing at Las Americas at a standstill—the racetrack never did open at all that year—and Gutiérrez beginning to fear that the pandemic would close the border between the countries, his wife and daughter followed him and Andrés to the States. María and Ana arrived in time to go from the airport to Gulfstream to see Letruska win the Added Elegance Stakes on June 27th, the trainer’s eighth win of 2020 and the mare’s first stakes win since December.

It was only just beginning to sink in that perhaps his life as a trainer in Mexico was behind him. The coronavirus changed the trajectory of Gutiérrez’s life, and he hates to consider how different things would be for him today if the “reality” that had shown him that Kukulkan wasn’t good enough to compete at the top level in the U.S. applied to Letruska, too. Or had it applied to Gutiérrez himself.

Reflecting on his career at Las Americas, he says, “When you’re leading trainer and you win between 100 and 200 races per year, you’re in a comfort zone, but at the end, I think my cycle there was over because nobody wants to see you there. They want you to go, especially in a country where there’s not much money to go around. It was like that: the giant against everybody else.”

It was markedly different for Gutiérrez in the States. He’d gone from being a giant in one country to almost unrecognizable in the other. The exploits of Letruska, though, have returned him to “giant” status.

After the Added Elegance, the Kentucky-bred daughter of Super Saver whom Larrea had bought in utero for $100,000, went on to win a pair of Gr. 3s: the Shuvee at Belmont in August and the Rampart at Gulfstream in December.

Going into her five-year-old season this past January, Letruska shipped to Sam Houston for the Gr. 3 Houston Ladies Classic. It was a homecoming of sorts for her trainer, who was disappointed to learn that only the bookkeeper remained from his first time there in the late 1990s. Still, it felt good to be back, especially with a high-caliber horse like Letruska, who won the race.

Her trainer, however, had his eye on a bigger prize.

“When you come from the minor leagues and reach the major league, you want an autograph. I wanted a photo with Monomoy Girl,” he says, speaking of the 2018 champion three-year-old filly and 2020 champion older dirt female trained by Brad Cox.

With a matchup in the Gr. 1 Apple Blossom Handicap in his sights, Gutiérrez sent Letruska to Oaklawn, where she’d won an allowance optional claimer in April the previous year, to use the Gr. 2 Azeri Stakes as a prep for the Apple Blossom. In the Azeri, Letruska met with her only loss of 2021, finishing second, a head behind last year’s Kentucky Oaks winner Shedaresthedevil, Monomoy Girl’s stablemate.

Then it was on for his Mexican champion to face two reigning Eclipse Award winners, Monomoy Girl and Preakness winner Swiss Skydiver, trained by Kenny McPeek, in the Apple Blossom. Monomoy Girl was favored by the betting public, followed by Swiss Skydiver and Letruska. At the half-mile pole, announcer Vic Stauffer’s race call described the trio, led by Letruska, as “the interloper and two champions” as Gutiérrez’s dream major league matchup unfolded.

“For me, it was perfect,” Gutiérrez says of the stretch run battle, where Monomoy Girl put her head in front of his mare—the “interloper,” despite being a champion herself—and he thought Letruska would be second. “I knew that I was not going to lose absolutely anything. Second was a great result, and when I saw that we were going to get second, few times in my life have I enjoyed so much a race I was losing. When I saw Monomoy Girl winning, I said, ‘It’s okay. It’s a very good result. We’re not coming second or third by 20, and we’re up against the best mares.’ So I sat like this, watching.” He leans back in his chair and stretches his arms out, the posture of a relaxed man savoring his achievement.

“My whole history in Mexico ran through my mind, everything I had done to get there to that race,” he continues. “And that was when the announcer said, ‘And Letruska…!’”

Gutiérrez waves his hand dismissively as he recreates the scene. He was fully not expecting to get the win and refused to get his hopes up...second to Monomoy Girl? He’d take it. But Stauffer’s call was right. The margin in the Apple Blossom was a nose, with another 6½ lengths back to Swiss Skydiver in third.

“It was incredible. I had dreamed of winning, but not like this. That race is going to be one of the moments of the year, because both of them ran strong. It wasn’t that Monomoy Girl stopped and Letruska came along and won.”

In the aftermath of the Apple Blossom, Gutiérrez sensed a change in his mare. “From then on, she understood that she was big. The horse that won the Shuvee, it is not this horse.”

By the time he arrived at Keeneland in early May with his small stable, Gutiérrez was as recognizable there as he had been at Las Americas, with strangers walking up to talk to him about Letruska. “I just love your mare,” they’d say. Or, “When is she coming out to train?” It’s almost always “la yegua,” “she,” or “her”; very rarely do they use her name, which is superfluous by now.

Gutiérrez, a quiet man, doesn’t often say much, but he smiles, nods, and thanks them all.

Before long, every time she’d come out to train, the bay mare with three white legs, a small star, and a regal bearing was being pointed out and discussed by other trainers, owners, grooms, EMTs, bloodstock agents, and random folks standing on the rail. At first, riders would turn their heads as they jogged past on their mounts to ask her rider, “¿Esa es la yegua?” Is that the mare?

It’s not just that she’s the best older filly or mare in the country; there’s more to it than that. Backstretches across the country are heavily fueled by a Hispanic workforce, including many from Mexico, so there’s an added element of pride in seeing one of their own, even though she’s not a Mexican-bred, emerge as a championship contender, with the architect and owner two more of their own. Gutiérrez feels that pride, too.

It’s fair to say that regardless of the future, the Apple Blossom was a defining moment—or perhaps the defining moment—for Gutiérrez. But Letruska has taken him from defining moment to defining moment, and she may not be done yet. With the top race mare in the country in his care, Gutiérrez feels the gravity of his responsibility.

“When you have a horse like this, you can’t make any mistakes. I have to be very careful and give her special care, while knowing at the same time that she’s a horse,” he says. “I can’t do more than I can do, and it can make your head spin. I don’t think about how much she’s worth. I just try to keep her well and get her to the next race.”

Letruska’s campaign has been a fearless one. After the Apple Blossom, she trained at Keeneland and shipped to New York to win the Gr. 1 Ogden Phipps Stakes at Belmont. Brad Cox, the trainer who had defeated Letruska once with Shedaresthedevil, tried to beat her again, but his pair of Bonny South and Shedaresthedevil were second and third in the Phipps. Then, in a move that surprised many, Gutiérrez wheeled Letruska back in the Gr. 2 Fleur de Lis at Churchill, 21 days after the Phipps.

Letruska is a keg of dynamite on four legs. She can detonate one minute and docilely allow a toddler to pet her nose the next. When Gutiérrez noticed that the Phipps hadn’t taken much out of her, he felt it would be better to run than leave her in the stall with no outlet for her explosive energy. In what was essentially a paid workout, she won the Fleur de Lis by 5¾ lengths on his daughter Ana’s 15th birthday.

Groom José Díaz Jiménez has a special bond with stable star Letruska

Gutiérrez credits groom José Díaz Jiménez for his bond with Letruska. “José is very important. He has a lot of passion for what he does, and he knows her. This mare is very difficult. And we know each other very well, the three of us. When she feels better, she’s more aggressive. José tells me to be careful because she’s no longer playing, and she’ll get you. She’ll put her ears back, and she’ll turn around and fire. That’s why I don’t put her on Regumate, because she’d get even more aggressive.”

His target for Letruska after the Fleur de Lis was the Gr. 1 Personal Ensign Stakes at Saratoga. “It’s a Grade 1 race. We can’t leave it. Don’t you agree? Do I sit here and keep fighting her, or not? If you’re number one, you have to defend that and you have to keep winning. You take the risk. You can’t defend it at home. That’s my opinion. After 30 years of doing this, you need to know how to lose. If you know how to lose, one day you’re going to win. And she wants to run. She’s more of a problem for me if she doesn’t run. Like I said about Kukulkan, we’ll lose a Grade 1. I don’t want to lose in a Grade 3.”

You already know that she won the Personal Ensign, despite pressure on the front end and talented fillies and mares coming at her in waves. Old foes Bonny South and Swiss Skydiver were second and fifth, respectively, split by Chad Brown’s two: Royal Flag and Dunbar Road.

After returning to Keeneland, her adopted home track, in September, Letruska trained up to the Gr. 1 Spinster Stakes on Fall Stars Weekend in October with two bullet works. Cox and Brown tried again to beat her, but Letruska was in front at every call, with Dunbar Road and Bonny South again filling the minor places. It was her fourth Breeders’ Cup Challenge automatic berth “Win & You’re In” victory.

Only one more start, the November 6th Breeders’ Cup Distaff at Del Mar, remains to close out the five-year-old mare’s season. Rogers Beasley, who is now executive vice president and chief strategy officer of Breeders’ Cup Limited, is happy to see his old friend coming in with the favorite for the Distaff, saying, “It’s fantastic. He’s just a genuine, unassuming person. Fausto feels very honored and very blessed to have a wonderful mare like Letruska, and I think he’s doing an excellent job managing her.”

It’s true; it’s a heckuva campaign Gutiérrez laid out for Letruska, an Eclipse-worthy campaign—not only for his mare, but as the architect behind her every move, potentially for him as well. In seven 2021 starts, Letruska has a record of six wins and one narrow second, all in Graded stakes races, including four Grade 1s, with one more Grade 1 on the schedule. It speaks to Gutiérrez’s appreciation for racing as it should be as well as his confidence in Letruska, who is better than she’s ever been.

“I don’t know how high she can go. She’s more horse than before.”

She’s won seven of eight races since Gutiérrez removed her blinkers after a fourth-place effort of four runners in last year’s Beldame at Belmont.

“Before, with the blinkers, she ran with the clock, not against the other horses. Now, she sees them.” Is that partially responsible for a big change in her? “Oh, absolutely,” says Gutiérrez. “She has more control of the situation now.”

His handling of this special but not easy mare is perhaps the biggest reminder that Gutiérrez is already a champion trainer. He’s always watching and reading Letruska, adapting to her changing moods, and he likes to shake up her routine occasionally.

“I try to keep her distracted,” Gutiérrez says.

One morning, he stopped her rider as they were coming off at the gap. “Take her around one more time,” he told him. “She needs to do more.” Another time, he handed her off to trainer John Ortiz, in whose barn she’d been at Oaklawn, to pony without a rider on the training track at Keeneland.

Gutiérrez doesn’t adhere to a strict breeze schedule with Letruska, who comes out of her races looking as though she’s ready to go right back into the starting gate. “Sometimes I think she’s going to come up short on training, but no,” Gutiérrez laughs. “All she needs to do is conserve herself. She doesn’t need to work every six or seven days.”

When she does breeze, she goes alone, and she’s gotten the bullet 18 times in 36 works in the U.S., at Saratoga, Keeneland, Oaklawn, Belmont, and Palm Meadows—everywhere she’s ever worked bar Gulfstream, where she had just one breeze before her first start in the country.

Letruska broke well from the gate before she made the early lead in the Personal Ensign

She has her quirks. “She was very nervous, so we taught her to stand on the track,” Gutiérrez says. Before training, she relaxes and watches everything around her, which she enjoys doing so much that doesn’t always want to move when it’s time to get going. Díaz has been known to slide underneath the rail to grab her reins or wave his arms to coax her into motion, or an outrider or one of the pony riders will try to get her to budge. It’s not unusual for it to take five minutes or more to get her going. “It’s just part of her personality now.” The longer she’s been at Keeneland, though, the more cooperative she seems to have gotten.

Larrea designates a different first letter of the alphabet for each of his foal crops. All of his 2016s have L-names, the 2017s are “M”s, the 2018s “N”s, and the 2019s “O”s. So when it came time to name Letruska, who has a stakes-placed older half-sister named American Doll, he wanted to name her for the Russian matryoshka doll—a wooden doll that opens and contains a series of smaller dolls, each of which opens to reveal more dolls, in decreasing size increments, until the innermost doll is revealed. “Letruska” is a play on the Spanish word for the matryoshka, and in the mare’s case, no one has gotten down to the bottom of her to know how deep the layers go.

It’s similar with her trainer, who’s shown with each adversity that he has more layers beneath the surface. And while the success of this—the reincarnation of Gutiérrez’s training career—is largely down to one horse, he’s no one-trick pony, having won three races this year with Vegas Weekend and two with Dramatic Kitten to contribute to his 15-win total so far in 2021. From three starters at Saratoga over the summer, he had three winners.

“I don’t have the horses of Brad Cox, Steve Asmussen, Todd Pletcher, Tom Amoss,” he says. But he has a Letruska, and he’s placing his other horses well and grinding out wins. Vegas Weekend was claimed from him for $50,000 at Saratoga, but he quickly filled her stall with a horse he claimed for $25,000. That gelding, Quick Return, proved to be well-named: a month after the claim, he won an allowance at Belmont for Gutiérrez and owner St. George, earning $44,000.

Still, Gutiérrez knows that his will be a very different story when the big mare eventually retires, which he hopes won’t be for a while, as he’s got designs on taking on the boys in the Saudi Cup or the Dubai World Cup in 2022. But looking ahead to a future without Letruska, he bought close to 20 yearlings on behalf of Larrea at the recent Keeneland September sale. Among his purchases was one that seemed meant to be as soon as the catalogue came out: a Super Saver filly, like Letruska, out of Mexican champion Pachangera.

As we wait to see if any of next year’s two-year-olds will be as good as Letruska, Gutiérrez is prepared to weather whatever fate throws his way. When his rider comes back from galloping a three-year-old More Than Ready colt carrying a broken stirrup strap in his hand, the trainer just shakes his head and laughs. “Sometimes I want to sit and cry, really. But I get back up and I say, ‘Let’s see what happens next.’”

It’s the getting up to see what happens next that’s gotten him this far, and he doesn’t let the thought of himself ‘starting over’ faze him.

“Sometimes in life, you have to let things be,” he says. All the obstacles Fausto Gutiérrez has had to overcome in his career show him to be a master of converting ‘let’s see what happens next’ into a big leap forward.

“Pero bueno,” he says optimistically. “This is my first crop!”

In the span of less than five years, the man who once said to himself, “Here I am. I made it,” as he stood in the enclosure at Keeneland to tighten the girth on a horse who ran unplaced in a $10,000 claiming race, saddled the favorite for a $500,000 Grade 1 in the very same paddock—and he won.

#Soundbites - What do you think racing will be like five years from now?

By Bill Heller

Todd Pletcher, Hall of Fame trainer

It’s difficult to project, but I think we’re going to continue to see what we’ve seen the past five years: a reduction in the tracks that are open. I think we’ll see continued growth in gambling, period. I think racing is benefitting from that—an open mindedness to gambling. Everyone now is gambling on football—pretty much on everything. One thing that grew during the pandemic was gambling. There will be fewer tracks but more of them operating successfully.

One thing we need to do is continue to make improvements on safety.

Assuming it (the HISA) goes through, it’s a good thing for the sport. We need some uniformity. It’s very difficult as a trainer to keep track of all the different rules in every jurisdiction. It should level the playing field.

Graham Motion, trainer

I hope, once we have the Horse Racing Integrity (and safety) Act in place, we’ll be in a better place five years from now. There will be smaller foal crops and less racetracks but a better product—one with more integrity. The status quo is unacceptable. It’s almost impossible to keep up with the different rules. We need uniformity and integrity, and right now we have neither.

Kelly Breen, trainer

I think what we saw in the pandemic was that people are betting—maybe more online. So many people learned how to bet on their phones and iPads during the pandemic that we’re setting record handles.

On track, you go to Saratoga, and it was mobbed. On the blue ribbon days, everybody is going to show up. I’m at the Keeneland Sales, and you can’t raise your hand. Racing is good. If you can get a good legislative body, and get everybody together for where we need to be in the next five years so you don’t have different rules on medication, the good horseman will be around.

Cliff Sise, Jr., trainer

Will we be here in five years? They are just tearing it apart. In New York, they have great purses now, but the new governor wants to take all that money and spend it otherwise. If that happens, purses will go so low. In California, Del Mar does well, but we don’t have the contract to get the purses up to where they should be. Owners are getting disgusted. We’re all shaking our heads wondering if we’ll be here in five years. It depends a lot on governors. If they look down on us, they can just say no more horse racing. PETA is watching us. We’re under the microscope so much. It’s a tough game to enjoy anymore.

Eric Jackson, Oaklawn Park Senior Vice President

Five years is a pretty short time from now. There will be fewer tracks than today, but those that survive the withering will be better than before. Sports are popular. I think it will be quality over quantity. In any sport, there’s demand to see it at a better level.

Chris Merz, Director of Racing, Santa Anita

I’m going to shed a positive light. I’m hoping this new bill puts everybody on the same page with the same rules. Then we can coordinate post times so they don’t conflict. It will be an industry working together to help the industry. We need to make this work. I think we’ve seen what happens when we don’t.

Michael Dubb, owner

There will be more consolidation, and we’ll be probably at the infancy of a marriage to legalized sports betting providers. I think that’s the future of racing. Anything that grows handle is probably good. You get a sports provider and a content provider, and the future will be TVG horse shows—you get on somebody’s platform. Do I want to bet if it’s sunny or cloudy? Do I want to bet football? Here’s horse racing. Do I want to bet that? think that’s the future of racing. Twenty years ago, we didn’t know the future of racing would be iPads. That’s how it turned out.

Barry Schwartz, owner and former CEO of the New York Racing Association

A lot has changed because of the pandemic. I think it exposed people to gambling on the Internet. Handle is everything. To me, right now, racing looks very alive and well. You see what’s going on at Keeneland. They’re already way past last year. Critical to racing is HISTA. They’ve got to get that up and running so the public has more confidence in racing, and that racing is legitimate. I think if we have a real strong organization in place, it will make people a lot more confident about racing—about racing being legitimate. The bottom line is I see a lot of things to be happy about with racing going forward. I didn’t feel that way five years ago.

Nick Cosato, owner

I would like to think we’re headed in the right direction with the Integrity Act. I’m optimistic.

Jack Knowlton, owner

I’m optimistic that racing will be in a better place in five years than it is today. In part, I do believe that the federal legislation will allow more resources to do the kind of testing we need to stay one step ahead of the cheaters. One of the big things is we never had enough resources to do the research. They’re coming up with new stuff to cheat. In my mind, that’s the biggest issue racing is facing. I think you’re going to have owners feeling better about participating.

And we’ll have one set of rules. The other thing, and we’ve made strides, is the issue of safety. We look at the data, and we’re getting a lot better, but there’s more work to be done. We have to continue to improve it. That’s definitely going in the right direction. The other issue is after-care, making sure we find a place for these athletes when they’re done with their careers.

When Payday turns to 'Someday' - Getting paid for your work as a trainer

By Peter J. Sacopulos

Recent lawsuits are shining a light on one of Thoroughbred racing’s ongoing problems: owners who do not pay their bills. Trainers often top the list of those who get stiffed. What can you do to protect your business and help ensure you are paid for your services? And what are your options when a client does not pay?

A trainer’s dream

Growing up on a farm in Indiana, Frank seemed to have been born with a knack for horses. By his mid-twenties, he had begun training Thoroughbreds and was looking for clients he could build a business on. Walter, an investment banker from Indianapolis who loves racing, purchased a promising Thoroughbred named Rocketastic and needed a trainer. Walter had heard good things about Frank, and after watching “the kid” work with a horse at the track, a deal was struck.

Frank agreed to train Rocketastic for $100 a day, or $3,000 a month. This amount included the cost of feeding and stabling the horse in Frank’s small barn. The men shook hands, and Frank trailered the horse home. Rocketastic chalked up impressive fractions and earned his gate card. Official works were logged and approved. The owner and trainer agreed that three or four starts during the two-year-old season seemed reasonable. Walter mailed Frank a check at the end of every month to pay for training and expenses during the previous 30 days.

Rocketastic had the makings of a real contender. But early in the season, the horse suffered disappointing starts. Adding to Frank and Walter’s frustrations, the local racing secretary repeatedly wrote races that kept Rocketastic off the track on race day

The money stops

Frank was confident it would all work out. But by late August, he had not received payment for his work in July. Frank felt certain this was an oversight on Walter’s part. After all, he and Walter shared a good working relationship and a common goal. Frank understood that Rocketastic was not earning his keep, but Walter appeared to have plenty of money to cover costs. The owner was well dressed, sported a Rolex watch and drove a Porsche. He lived in a beautiful home in a gated community, and his children attended expensive private schools.

When Frank called Walter about the lack of payment, the owner assured him that a check was already on the way. Frank continued to train Rocketastic, but by mid-September, neither the July nor the August payments had arrived. Frank again called Walter, who insisted there must be a problem with the mail. Frank grew skeptical after his local postmaster told him there had been no complaints of lost or stolen mail. Soon Frank’s calls to his client went unanswered and unreturned. Voicemails, emails and texts were ignored as well.

Still, Frank was reluctant to give up on a promising horse, or the promises of its owner. By early November, Walter owed him over $13,000 in back pay and expenses. The lack of cashflow put tremendous stress on Frank’s business and his marriage. He did not know what to do or where to turn.

A recurring problem

The situation I have described is hypothetical, but it is based on numerous real-life complaints that I have heard from clients and potential clients. The fact that some owners do not pay their bills is a serious industry issue. It is known all too well by many who work in the industry. Anyone who thinks this is simply the result of trainers who lack business sense working with owners who lack horse sense should think again. Recently, the racing press has been filled with articles covering cases currently winding their way through the courts. Details vary, but the bottom line is the same: Trainers are not getting paid for their work.

In this article, I will review high-profile cases and offer some pointers to help you avoid payment problems. I will also explore the options available when a client is unwilling to pay.

The Ramsey lawsuits

In March of this year, owner/breeders Ken and Sarah Ramsey were hit with back-to-back lawsuits. Each was filed on behalf of a trainer who claimed to be owed nearly $1 million in unpaid bills. The Ramseys are well-known Thoroughbred breeders and owners, with an impressive string of victories and a shelf full of Eclipse Awards to show for their efforts.

Yet trainer Mike Maker’s suit alleged that the Ramseys had been behind on their training bills for years and owed him over $900,000. Another trainer, Wesley Ward, claimed the Ramseys owed him over $970,000 in unpaid bills, percentages of winnings and accumulated interest. Like Maker, Ward acknowledged that the Ramseys had paid some of their tab but alleged that the balance due had been in the high six figures for months and continued to grow.

Initially, it appeared these matters would be resolved out of court. Ken Ramsey told reporters that he had some cash flow problems but intended to pay both trainers. Unfortunately, Mike Maker’s legal team was back in court in July, claiming that the Ramseys failed to meet the agreed-upon payment schedule. In early August, Wesley Ward’s attorneys filed for summary judgement, stating that all payments from the Ramseys had ceased.

Wesley Ward is another trainer to sue the Ramseys this year for allegedly failing to pay board and training bills

The Ramseys’ response revealed a major change in strategy. BloodHorse.com reported that the Ramseys’ new filing stated that there was no written agreement between Ward and the Ramseys on a day rate, what horses a rate should be applied to, or terms of payment. The filing also claimed that Ward had refused the Ramseys’ request to return 30 of their horses, and argued a potential lien on the animals would conflict with other statutes governing lawsuits in Kentucky. The filing also requested time to prepare a countersuit against Ward. As of this writing, it appears that all parties involved in both suits could be facing long, complicated legal battles.

Zayat’s legal woes

Meanwhile, a painful example of a long, complicated Thoroughbred legal battle continues to play out in the courts. At its center is Egyptian-born, Triple-Crown-winning owner Ahmed Zayat. Zayat, who founded and operated Zayat Stables, is the kind of larger-than-life character that racing enthusiasts love. Or love to hate. In 2015, the year American Pharaoh delivered Zayat Stables’ Triple Crown and Breeders’ Cup triumphs, Joe Drape of The New York Times described Ahmed Zayat as “flamboyant” and “controversial.”

Zayat made his fortune when his investment group bought, modernized and sold an Egyptian beverage company. He then set out to build a world-class Thoroughbred operation. Zayat spent big and enjoyed major successes, but he was sued by Fifth Third Bank in 2009 over an alleged $34 million in unpaid loans. He filed a countersuit, claiming the bank had engaged in predatory lending practices. Zayat Stables filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, allowing the company to continue doing business while attempting to deal with its debts. Legal proceedings soon revealed that Zayat owed significant sums to a number of creditors, including a total of $148,798 to trainers.

Ahmed Zayat and Mr Z at Churchill Downs 2015

Zayat Stables eventually came to terms with its creditors, including Fifth Third Bank. It emerged from bankruptcy and rode to glory with American Pharoah, among others. Then, in January 2020, history repeated. MGG Investments filed a lawsuit against Zayat Stables and Zayat family members, alleging the Thoroughbred operation had failed to pay back $23 million of a $30-million loan. Zayat filed a countersuit, alleging he was the victim of a predatory lender acting in bad faith, as he had done in 2015.

Accusations and allegations fly

Zayat’s ongoing legal struggles have taken many twists and turns, but I will do my best to summarize. MGG expanded its lawsuit, alleging that Zayat had conspired with family members and others to hide money and distort the value of assets, including horses and breeding rights. MGG also claimed that Zayat had sold assets that were to serve as collateral for its loan. A judge appointed a receiver to take control of Zayat Stables’ finances. Court proceedings again revealed a long list of unpaid bills, and some of Zayat’s many creditors filed legal actions of their own.

In June 2020, a Kentucky judge ruled that Zayat owed MGG some $24.5 million in loan payments and interest, and dismissed many elements of Zayat’s countersuit. The judge also dismissed MGG’s claims against industry professionals who had done deals with Zayat Stables, but ruled that MGG could move forward with a fraud claim against Zayat. Ahmed Zayat filed Chapter 7 bankruptcy in September 2020. Most of his company’s assets, including Thoroughbreds, were auctioned off by the end of the year. This summer, Zayat’s bankruptcy attorney asked to be allowed to withdraw from the proceedings, claiming his client had racked up nearly $370,000 in unpaid legal bills.

Zayat Stables’ legal problems also revealed that the operation had run up a total of over $1.5 million in debts to a who’s who of Thoroughbred trainers, including Bob Baffert, Brad Cox, Mike Maker, Richard Baltas, Steve Asmussen, Todd Pletcher and Rudy Rodriquez.

An ounce of prevention?

As these events attest, there is no foolproof way to determine whether a client will pay a trainer. But there are some things you can do to protect yourself. Ideally, a trainer and an owner would sign a written contract detailing their arrangement, including the number of horses to be trained, the trainer’s day rate, terms of payment, etc. Written contracts benefit and protect both service providers and their clients, and are accepted as routine in most industries. Horse racing, however, is a notable exception.

Andrew Mollica has worked as racing official, broadcaster and an agent for top jockeys, among other things. In his forties, Mollica returned to college to earn a law degree. Based in New York, he currently practices law, with an emphasis on equine law. Mentioning contracts to Mollica draws a quick response. “I’ve worked in racing for nearly 45 years,” Mollica says, “and I’ve never seen one—not any kind of written agreement between an owner and a trainer. They don’t seem to exist!”

Mollica’s not sure what an owner would do if a trainer asked for a written contract, or vice versa. Not that he thinks many would. “American Thoroughbred racing is a 21st-century industry run like an 18th-century enterprise. So much is done on handshake deals. Good or bad, that’s the way it is,” he says.

As an equine attorney and Thoroughbred owner myself, I know that suggesting you create a simple contract for your services and ask your clients to sign it may cause you to roll your eyes in disbelief. But it is still a good idea. Contracts can be awkward to ask for upfront, but they make all the difference when things go wrong. That is why the phrase “get it in writing” remains a business staple.

If you do not have a contract, consider sending a follow-up letter or email to your client that outlines your understanding of the terms of your verbal agreement. If the owner thinks you have misunderstood the deal, he or she will likely respond regarding the areas in question. If there are differences, once those differences are resolved, I suggest sending an additional letter or email that documents exactly the agreed upon terms.

The upfront approach

Of course, you should always keep accurate records of your working hours and expenses. You should also consider requesting to be paid upfront. In the event you are training horses on a monthly payment schedule, request payment. If payment problems arise, you will know from the get-go. If you are not comfortable requesting the full amount in advance, consider requesting expenses for care and feeding. That can go a long way towards a solid cash flow.

If you are concerned about entering a business relationship with an individual, you may conduct an online background check. Many reliable companies provide this service at a reasonable price, including Intelius, TruthFinder, BeenVerified, and others. A standard “people search” will typically review public records from the last seven years, should report any bankruptcies or criminal convictions, and does not require you to obtain permission of the person in question under current U.S. law.

You may also consider conducting a credit check online. But be aware that credit checks are governed by strict federal regulations, as well as applicable state laws. In the United States, you must obtain written permission from the individual whose credit report you are requesting, among other requirements. You cannot legally conduct a “secret” credit check.

Remedies for unpaid bills

In the event the client/owner refuses to pay, what are your options? When this happens, act sooner rather than later, and document your communications with the client regarding the matter. Keep a written phone log listing calls and texts, save all emails, and keep copies of anything sent by mail. Once you have made a reasonable effort to get paid, contact an attorney, preferably one with equine experience.

Every case is different, but here are some likely scenarios. Your attorney will contact the client, requesting the debt be paid to avoid legal proceedings. This alone may result in payment. Or it may result in acknowledgment of the monies owed and a negotiated payment schedule. If you are in possession of the horse (or horses), you will have to continue caring for and feeding the animal(s). Though this will increase the amount of expenses you are owed, you cannot simply neglect the horse. However, whether or not you continue to train the horse is your decision, and I suggest you make that decision with the help of your attorney.

Lawyers, liens and money

If the owner refuses to make a good-faith effort to resolve the matter, and the horse is in your possession, your attorney will likely file for a lien. This powerful legal tool allows you to retain the horse as collateral until the debt is paid and retain or sell the horse if it is not. The specific term for this type of lien varies from state to state. It is commonly known as an agister’s lien, a stableman’s lien or a liveryman’s lien. The rules and regulations governing these liens vary by state, and it is important that you work with an experienced attorney when attempting to attain such a lien.

Obtaining an agister’s lien is a multi-step process. “If the horse is in your possession, and it’s worth more than the debt, you will get paid,” Andrew Mollica says. “But you have to follow the process.”

American Revolutionary War hero James Lawrence shouted, “Don’t give up the ship!” when the British attempted to board his vessel. “Don’t give up the horse!” is Andrew Mollica’s remarkably similar battle cry for trainers dealing with unpaid bills. Good advice, because in most states, if you return the animal to the owner or turn it over to officials, you may surrender your right to obtain or enforce an agister’s lien. If you are pressured to return the animal by anyone, inform them that you are in the process of obtaining a legal lien and have the right to retain the animal until the lien is issued.

Many owners pay up when they learn of lien or possible auction. “They suddenly realize you’re serious and act accordingly,” Mollica notes. What if they still refuse to pay? If you auction the horse, in most states, you are entitled to what you are owed, plus legal expenses, including the cost of obtaining the lien, as well as the auction costs incurred. If the horse sells for more than what you are owed plus expenses, you are not entitled to keep the difference. You must send that money to the owner who hired you—no matter how much you resent them. If the horse sells for less than you are owed, you may pursue the remaining debt in court.

The bankrupt owner

Finally, if an owner who owes you money declares bankruptcy, hire an experienced attorney to file an official claim on your behalf with the bankruptcy court. The court will ultimately decide which creditors get paid how much and when. Filing a claim will not guarantee that you get paid the full amount you are owed. In fact, it will not guarantee that you get paid at all. However, failing to file a claim pretty much guarantees that you end up with nothing.

No trainer, no matter how skilled or successful, is infallible when it comes to sizing up which clients will pay their bills. Hopefully, these examples and recommendations will assist you in avoiding unpaid invoices, and help you obtain the money you are owed if payday ever turns to “someday.’

Q&A with Terry Finley of West Point Thoroughbreds - thoughts on racing

By Bill Heller

While adept at deflecting credit for his successes, 57-year-old Terry Finley —a 1986 graduate of West Point—has emerged as an industry leader, currently serving as the chairman of the New York Thoroughbred Chaplaincy and on the board of the Belmont Child Care Association, the Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association and Thoroughbred Charities of America. He was on the board of the Breeders’ Cup from 2004 through 2011, the New York Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association, and the Jockey Club. He was elected a member of the Jockey Club in 2019.

Terry Finley’s West Point Thoroughbreds enjoyed a stellar 2021, highlighted by Flighline’s impressive win in the Malibu Stakes (Gr. 1) on December 26.

To date, West Point Thoroughbreds has won over 950 races, including 56 graded stakes with earnings of more than $60 million. Four years removed from its Kentucky Derby victory with Always Dreaming, West Point has brought in more than 2,000 new owners to the industry. Terry’s wife Debbie and daughter Erin are key members of the company.

Has the Breeders’ Cup accurately carried out founder John Gaines’ vision?

Yes. Mr. Gaines, who I didn’t get to know unfortunately, wanted the Breeders’ Cup to be in essence our Super Bowl—to bring everybody together to promote Thoroughbred racing and spotlight horses, owners, breeders and trainers. It’s a much more focused operation with the allocation of stakes money, the “Win and You’re in” program, the shipping bonus, the international participation, the event itself. The ongoing success of the Breeders’ Cup is a grand slam for our industry.

Is there room for future growth?

I’d like to think there is. There are really sharp people of the younger generation in our business. There’s always room to get better. I do know that Drew Fleming and his staff have not sat back on their heels so far, and I certainly don’t see them doing so in the future.

Are there new markets for the Breeders’ Cup?

Yes. Would it be good to have it in New York? Yes. But they don’t just decide that in a day. I trust the people who are working on this—the people on the board. I trust the process.

What can be done to prevent further shutdowns on major tracks such as Arlington and Calder—both shut down by Churchill Downs, Inc.?

The industry can attract more breeders, owners and bettors. That’s really the one thing that we, inside the business, need to do to have any semblance of an impact: to grow our sport. I venture to say that if we were still at 36,000 foals—we’re at 19,000 now—Churchill Downs would have been less apt to sell Arlington Park. A public company’s first priority is to their shareholders. It’s disheartening to so many of us to lose racetracks. If our business continues to contract, we’ll have additional race tracks close. It’s inevitable. That’s just market equilibrium.

Should we limit stallion book sizes?

I don’t breed a lot of horses. It’s a complex issue. But if anybody thinks that the current direction of our breeding pool and breeding industry are going to put us in a better spot in 10 or 15 years, I haven’t heard any cogent explanation of why they think that would be true. You either sit on your hands as an industry, or you work for the betterment of the industry by taking action; and the Jockey Club has done exactly that.

Debbie and Terry Finley with daughter Erin

Does the industry have to rewrite what ADW pays into purse accounts?

There are irregularities in revenue sharing created by the changing landscape in our industry, each seemingly to the detriment of the purse account. It's good for every part of the industry to have equitable sharing of the revenue for each dollar bet. There’s a lot of upside if we don’t dig in our heels, on either side. Owners and trainers who lead the various local horsemen’s groups need to ensure these inequities are addressed in a fair and equitable way.

It’s a complex situation. The market and the industry have changed. Good leaders from every facet of our industry step up when things change and make adjustments. We know it’s important for long-term viability of owning and operating racing stables. That’s at the core of the Thoroughbred industry, of owning horses, breeding horses, training horses and selling horses. It’s not just the owners that are impacted. It’s the jockeys, it’s the trainers, it’s the breeders, it’s the sales company. All are impacted by that revenue pie. Overall, I have faith that we’re all going to be able, through work and compromise, to adjust things to take into account the market decisions we face right now.

With the growth in partnerships and shared owners, would it be good for the industry to introduce a formal code of conduct for those who syndicate horses to give greater transparency for those who wish to join?

Absolutely. One was recently initiated in Europe. As long as everything’s transparent, when you buy horses at auction, people know what they’re paying for. I would be in favor. The more we discuss the areas of our industry that have gone untouched for so long, the better for all of us.

Were you in favor of the Horse Racing Integrity and Safety Act (HISA)?

When I started out, when I first learned of it, I wasn’t in favor of federal involvement in our game for any number of reasons. The more I learned and the more I got into it, I realized that for decades now, there have been a strong group of people who benefit from the ill-conceived and a patchwork of different regulations in the 38 states that are running racing in the United States. I looked and saw the same people say “Trust us, give us a little more time, I’ve got this. I’m the smartest person in the world. All you have to do is ask me.” I realized that in so many years, back in the ‘80s and the ‘90s, they’re saying the same thing they’re saying now.

I started to see more smoke and mirrors. It just hit me one day that we need a new system. It was probably around the time the Jockey Club took up the pursuit of federal legislation. It started with Arthur and Stacy Hancock saying we’re dealing with the Wild West when it comes to medication. You basically just stand there. I am not unique. There are a lot of people for a lot of years who are all in, putting everything they have into the racing business. We’re so far in; we’re not going to do anything else.

There had to be a better way.

That view came from my association with the horsemen groups. There are people who weren’t elected, who were making a lot of money and had not or were not involved in owning or breeding horses, and really had commandeered the voice of people who had true skin in the game.

As I went along, it became more and more clear to me that the progress was only going to happen if that message became accepted by a wider faction. I have a national organization (West Point). Our business would be on a better road with a national authority to address the integrity and the safety side of things.

Very few of the trainers that I’ve talked to were totally against it.

How bad has it been with different rules, involving, medication, use of the whip, rules for disqualifications?

Let me say this. The other thing that gave me confidence in HISA was I learned about the United States Anti-doping Agency (USADA). Just to have a federal law passed to create a new authority from scratch would be uber, uber concerning. Then you realize we’re not the first industry or sport to have undergone this process. One, in particular, was cycling. There are parallels there. The USADA has a model that’s tried and been tested. That’s what allayed the fears that I had initially with the federal government coming in. It’s not the federal government—it’s federal oversight. Cycling, martial arts, the Olympics—we’re not the only ones who had this done. They’re not creating the structure from scratch. They have learned from the other programs, especially cycling.

There is a level of independence we haven’t had before. It’s like we hit a Triple Crown. We got the law passed—that was the Derby. The Preakness was putting in the structure and the rules of the authority. The Belmont will be the execution and the refinement, putting it out and hitting the go button.

Can the Horse Racing Integrity and Safety Act improve public perception?

It will improve. Undoubtedly. I think people—and we talk to a lot of people who want to get in the game just in the past two months—are very clear that our industry wants to change, and we’ve taken action to change our sport. I would hope that I’m not the only one who’s seen a benefit from people knowing the jig is up with the people who blatantly cheat in our industry. When they see you’re trying and you’re taking bold, definitive steps, they’ll give you the benefit of doubt. They don’t want to hear people saying the same thing for decades, and it hasn’t worked. They know it. Sophisticated investors—the people we want to attract as owners and breeders—know it. Those types of things that would be good to promote: wealthy people who have been successful in their business. They know. People knew we weren’t authentic before. That changed very quickly with HISA.

What was the impact of having high-profile trainers who have had medication violations in our biggest races?

As an owner, I get sick to my stomach thinking of how long “those guys” on the backside have been peddling their latest “hop.” I simply can’t fathom how tough it’s been to have trained horses the right way over many years and know that races and money have been stolen from us.

Are you optimistic about racing’s future?

Yes, I’m very bullish on racing’s future. We all love the industry. It’s our time. Most states have stated publicly that they want to cooperate and want to participate. That’s a good sign. I know it’s not going to be easy. Some aren’t on board, but the train is rolling. Work is being done on this.

There are people who aren't in favor of this. Once it passed, they rallied behind it. That’s a good thing. It’s very gratifying to see the depth and the breadth of the support of this. Hopefully, that support is authentic. It’s just not words, but it’s deeds to support this. It’s easier to say you support it, but we need it to be true and authentic. I look at the HBPA. I don’t understand their position. They haven’t supported the initiative. If you can get through the criticism, ask them what their plan is. How would they attack the integrity problem in racing? I haven’t seen anything that could be called a program. It’s important for you to say not what you’re against, but what you’re for. I’m a member of the HPBA in many states. I’m disappointed with how they dealt with this.

Realistically, five years from now, where is racing headed?

I truly believe we’re in a much better place because we will have the entrenchment of HISA in our business and our backstretches and our sales. They’ll be independent, [have] oversight, much more and safer racing. The big events in our business will be bigger and more exciting to people. That’s my true belief. In five years, 10 years, we’ll look back at July 1, 2022—people will look back and say that’s when we turned the corner. Very similar to cycling, pre-Lance and post-Lance (Armstrong). I think we’ll have the same thing, pre-HISA and post-HISA. We can make it better.

From Sales Ring to Racetrack - Different opinions on bringing on the young racehorse

By Ken Snyder

The story is both funny and telling, especially as it comes from a legendary Hall of Fame trainer, courtesy of a newly minted Hall of Famer, trainer Mark Casse. Working for the late Allen Jerkens in his late teens and early 20s, Casse remembers the venerable “Giant Killer” of upset fame saying he wasn’t going to do anything with his two-year-olds because he wouldn’t have to worry about shins, sickness and all the rest. “I’m not going to train them at all at two,” Jerkens told Casse. A year later, commenting on the now three-year-olds, Jerkens said, “They did all the things they would have done at two.”

Not even a trainer as great as Jerkens can predict (or postpone) what will happen with two-year-olds, either in health or performance.

They all begin, for the most part, with fall yearling sales, most notably the August Fasig-Tipton sale in Saratoga and the Keeneland and Fasig-Tipton sales in Lexington in September and October.

Casse compares it to the NFL draft with one enormous difference: football players have a body of work—college football—to scrutinize. With horses, it’s pedigree, eye and instinct. A seven-figure Book One yearling might make the proverbial “cut list,” never even reaching the racetrack. A sale might also yield a Seattle Slew who sold for a relative pittance—$17,500 in 1975—and who etched himself into racing history as both a Triple Crown winner and legendary sire.

The “pre-season” for yearlings, to borrow again from football, is sales prep. Ninety days before a sale is the ideal time to begin prepping yearlings, according to a 10-year veteran of Thoroughbred consigning, Sarah Thompson, now an equine analyst for Eclipse Bloodstock. The minimum can be as little as 30 days.

Good looks can mean gold, and that is a variable with young horses that can be controlled somewhat. For a dark, rich coat, most yearlings (except for a few not keen on being outdoors all night) stay in the barn through summer months till seven in the evening when they are turned out into paddocks for the night. Sun can bleach coats, especially tails. (The few horses kept inside do get turn-out in the mornings but are brought in before the afternoon sun.)

Baths and grooming are daily, and as sales dates near, it ramps up with curry-combing to remove dead hair and application of hoof conditioner to improve appearance and strengthen hooves.

Conditioning is literally conditional as yearlings are not broken at this point. “There’s a lot of hand-walking. We also have automatic walkers,” said Thompson. Swimming is part of the regimen as well. “The idea there is you get the condition without the impact on the joints and bones,” she added.

Diet is generally the same for all yearlings. How a horse puts on muscle and weight (or doesn’t) and the horse’s body type can mean a tweak either to more nutrition or less.

There is little to prepare yearlings for a sales environment except for schooling on how to stand to show off conformation. The pose is standard for all horses but must be taught: left front leg forward, right slightly behind; left hind leg back, right hind slightly in front.

One surprising factor to horse sales has nothing to do with the horse, according to Thompson: “Having some of the best showmen on the grounds show [that] your horse can make you or break you. A good showman can move with that horse. Quiet hands are always a good thing, and honestly, it’s sort of the rapport between a showman and a horse.”

Once sold, it’s off to training centers and farms to determine if the yearling is worth what it cost.

Mark Casse

Casse operates his own training facility in Ocala, Florida—something he considers a huge advantage to his racing stable. Because of his success on the racetrack (career earnings are over $192 million and over $8 million in 2021 alone at the time of writing), he attracts a variety of owners, some of whom don’t have the goal you would expect: a Kentucky Derby winner. “I find out what people’s goals are. If your goals are to just have fun and win some races, then you go out and buy a speedier kind of horse that you can get ready earlier,” he said. “They’re not as expensive.” Others like John Oxley spend more, hoping for a Derby or Kentucky Oaks horse.

For a trainer of Casse’s stature, it is surprising that he also trains for one-horse owners who have paid as little as $5,000 for a horse. “I seldom turn somebody down as long as they have a passion for racing.”

Wesley Ward has built a Hall of Fame-worthy reputation with yearlings. His career win rate with two-year-olds is 24%, and at the time of writing, it was 33% for 75 starters this year. His success at Royal Ascot with “babies” has made him literally world famous. “I’ve won 12 races over there, and I think eight are two-year-old races,” he said.

He confirms what Casse says about owners’ goals. “Most of our horses are sprinters. The owners and stable managers tend to be giving me them,” he said. Ward might be minimizing accomplishments, however, as his overall win rate for horses of all ages is near the top for all trainers, a more-than- respectable 22%.

Wesley Ward

Ward isn’t protective of any “trade secrets” to account for two-year-old success. Winning is largely a matter of getting out of the gate well, for races run over distances as short as four-and-half-furlongs. “Most of my [exercise] riders that go to the gate are ex-jockeys,” he said. Again, he might be exercising excessive modesty when he said, “It’s not the trainer, but the person on their back.”

He does say he spends a lot of time “just getting the horses not scared” in gate training.

Ah, the gate—what Ward called the “big scary monster—this apparatus that we’re locking them up in.”

Everyone has their methods for gate training and, as any racing fan knows who has watched a horse balk or worse at either entering the gate or staying calm till it opens, nothing is foolproof. At his training center, Casse positions his gate where every horse every day must walk through it going and coming to the track. “That way it’s not something new to them,” he said. “After we do that for a couple of months where they’re used to it, then we move it over and change positions with it.” At that point, they go through a typical progression of having back doors closed and then front doors before breaking from the gate.

Travis Durr, owner of Webb Carroll training center in St. Matthews, South Carolina, employs a “monkey see, monkey do” principle in teaching gate work for yearlings as well as training in general. Like most every trainer of yearlings, he introduces gate work early but only a “few times a week,” unlike at Casse’s training center. Yearlings will follow a pony through initially.

An alpha male or female who will lead the pack takes it from there, showing the way for others. “If you’ve got 10 out there, you see which ones kind of want to be the boss, and which ones kind of want to lay back.”

Webb Carroll is known for exercising large sets with as many as 16 riders at work, depending on the time of year. “They’re used to being out all together. If you have a problem horse, it just makes it easier. They see all the other horses doing something, so they kind of fall right in. It’s a lot easier than if you’re getting just one to go out there.”

It is out of the gate, of course, where Thoroughbreds can earn fame and fortunes for owners. Methods in getting yearlings up to a three-eighths breeze vary between training centers and trainers. For Casse, the goal for a horse's first breeze will be 45 seconds or 15 seconds per eighth for a fall, two-year-old starter.

“A lot of times, they’ll all go in 45, but you can tell which ones it takes more of an effort to do that. That’s how they first start separating themselves.”

For Richard Budge, general manager of Margaux Farm in Midway Kentucky and former farm trainer for Winstar Farm, the first breeze will be a short sprint over a single eighth of a mile. “Then we take them up to a quarter [mile] and then three-eighths.”

Budge also separates the yearlings into early, middle and late groups. “The late group may be horses that may need a little more time or have a physical issue, so therefore you push them to a later group to break. I say the early group would obviously be the horses with a January, February, March birth date—that look physically ready to go right on with.”

Like Casse, the stopwatch is not as important to Budge as the way the horse goes about it. “If they’re doing it easily as opposed to flat out, that would be more important,” he said.

Margaux is a European-style farm, featuring a slightly uphill one-sixteenth mile straight with a Tru-Stride synthetic surface. Budge, an Englishman who has trained there, France, Brazil and the U.S., believes the combination of surface and straight track keeps yearlings more sound. A turn at the top of the straight does teach young horses to change leads.

Considering that two-year-olds are the human equivalent of 13-year-olds—arguably the toughest age for parents and teachers—trainers like Casse and Ward embrace the task of getting yearlings to the race track. Ward, in fact, expresses a preference for them. “This is what I love to do, especially the younger horses. This is what really excites me.”

And that’s a good thing—something with which Allen Jerkens might not agree…

When is a win not a win? Trainer Mark Casse has a surprising perspective on this.

First of all, his proficiency with two-year-olds is easily overlooked. His 2021 win rate with two-year-olds is 21%, and his career earnings with them are over $52 million compared to Wesley’s Ward’s career earnings of $28.3 million for the first-year starters. Most interesting, perhaps, is career earnings per start for Casse (at time of writing): $11,596 compared to Ward’s $11,065.

Success with two-year-olds is largely ignored but also improbable, considering his approach to “baby races.” “Never is it my goal to win first time out,” he said. “For the most part, it can be one of the worst things that can happen to a horse.

“A lot of times, what happens is we have a horse break his maiden first time out; and next thing you know, he’s running in stakes. At some point, no matter how fast you are, there’s going to be somebody faster than you. If you have a horse that knows nothing but to be on the lead, what if he breaks a little slow? What if something happens? I tell all my riders, the first time they ride a two-year-old for me, I’d rather be a closing fourth than a dying third. I like my horses to learn to run-by horses.

“Now, that being said, if a horse breaks running, and breaks one or two on top, they’re going to go with it.”

Horses with attitude - The concept of behavioural conditioning in racehorses

By Ken Synder

“One refuses to run. One can’t run. One gets hurt. One’s a nice horse you have a little bit of fun with. And one’s a really nice horse that helps you forget the first four,” said trainer Kenny McPeek with a laugh, as he categorized new Thoroughbreds coming into his barn annually.

In some cases, that first one—the horse that refuses to run—really is forgotten, falling through the proverbial cracks of large stables with plenty of “really nice horses.”

“There’s very few of them we can’t figure out,” he said, “but sometimes we can’t.”

That’s where people like 71-year-old horseman Frank Barnett of Fieldstone Farm in Williston, Florida, (near Ocala) get involved. “I wish you could get to it by skirting the ‘issues,’ but you can’t,” he said. “That’s how they got to me.” Those issues are not loading into a trailer or starting gate, balking at workouts, throwing riders and—bottom line—acting as if they don’t want to become racehorses.

The principal issue underlying all the others, according to Barnett and Dr. Stephen Peters, co-author with Martin Black of the book Evidence-Based Horsemanship, is forgetting that horses are prey and not predatory animals. “Your horse is constantly asking, ‘Am I safe?’” said Peters.

The question supersedes everything else in a horse’s brain and, unfortunately, isn’t part of most Thoroughbred trainers’ knowledge of how psychologically a horse functions, according to Peters—a neuroscientist and horse-brain researcher. “One of our big problems is the only brain that we have to compare to the horse’s brain is our own, so we develop ideas like respect and disrespect.

“Horses don’t have a big frontal lobe. They can’t abstract things.

“Would you beat a child who couldn’t figure out a math problem? Of course, you wouldn’t. Punishment in a horse’s environment is a predatory threat,” Peters added.