The art and science of feeding horses prone to gastric ulcers

Words - Sarah Nelson

Risk factors for squamous or ‘non-glandular’ ulcers are well documented and include low forage diets and long periods without eating, diets high in non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) or ‘starch and sugar’, intensive exercise and stress, as well as prolonged periods of stabling and travelling. While some risks may be unavoidable for racehorses in training, diet is one that can be influenced relatively easily.

In this article, Nutritionist, Sarah Nelson, discusses some of the science and provides practical advice on the nutritional management of horses prone to non-glandular ulcers. While glandular ulcers may be less responsive to changes in diet, the same nutritional management is generally recommended for both glandular and non-glandular ulcers.

Evidence that diet makes a difference

Research published by Luthersson et al (2019) was the first to show that changes in diet can reduce the recurrence of non-glandular ulcers following veterinary treatment. In this 10-week trial, fifty-eight race/ competition horses were paired according to their workload, management and gastric ulcer score (non-glandular ulcers graded 0-4). One horse from each pair continued with their normal diet while the other had their normal ‘hard feed’ replaced with the trial diet which was divided into three equal meals. Horses with grade 3 and grade 4 ulcers were also treated with the recommended dose of omeprazole for four weeks. All horses were scoped at the start of the trial, immediately after omeprazole treatment had finished and 6 weeks after treatment had stopped.

The majority of horses improved as a result of omeprazole treatment regardless of diet. Diet had no effect on grade 2 ulcers. At the end of the study, gastric ulcer scores in the horses that were fed the trial diet were not significantly better or worse than in horses that were not fed the trial diet. Overall, gastric ulcer scores in horses that were fed the trial diet remained improved 6 weeks after treatment had stopped. Six weeks after treatment had stopped, gastric ulcers scores had worsened in the majority of horses that remained on their normal feed so that overall, there was no difference between pre and post treatment scores.

Importantly, this research shows that changes in diet can help to reduce the risk of gastric ulcers recurring after treatment, even if other changes in management are not possible. There was also no apparent long-term benefit of omeprazole treatment alone, highlighting the importance of other strategies in the long-term management of horses prone to gastric ulcers. As this study only evaluated changes in ‘hard feed’, it is possible that greater improvements could have been achieved if changes to forage were also made.

Recent research reveals unexpected results

Regular turnout often isn’t possible for horses in training and while the risk of gastric ulcers generally seems lower in horses at pasture, recent research carried out in Iceland by Luthersson et al (2022) has highlighted this may not always be the case.

In Iceland, horses typically live out at pasture, often in large herds and if stabled, they are generally fed a high forage, low starch and low sugar diet. While Icelandic horses do get gastric ulcers, it’s been suggested that the over-all incidence is low.

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of gastric ulcers in Icelandic horses moving from pasture into light work. Prior to the study, all horses had lived out in large herds for their entire adult lives (age range 3-7 years), had never been in work and were fed supplementary forage in winter months only. All horses were scoped within two weeks of being removed from pasture (prior to starting ‘training’) and were scoped again approximately after 8 weeks of being stabled and doing light work. Most horses were fed forage only during the training period, but 11 were given very small amounts of soaked sugar beet and 3 were given a small amount of commercially produced feed. However, in all cases, starch and sugar intake from ‘hard feed’ was equivalent to less 250g per meal for a 500kg horse which is well within the current recommendations for horses prone to gastric ulcers.

Approximately 72% of horses had non-glandular ulcers (grade 2 or above) at scope 1. The prevalence and severity of gastric ulcers improved after eight weeks of stabling and light work - approximately 25% of horses had non-glandular ulcers (grade 2 or above) at scope 2. Horses given forage three times per day as opposed to twice per day were almost 18 times more likely to improve! Over-all, the incidence of glandular ulcers decreased from 47% to approximately 41%

The high prevalence and severity of non-glandular ulcers at the start of the study, and the subsequent improvement following the training period was unexpected. Not only is this research an important reminder that horses at pasture are still at risk of gastric ulcers, it highlights the importance of regular forage provision.

Forage focus

Forage is critical for mental wellbeing and digestive health in all horses but sometimes receives less attention than ‘hard/ concentrate’ feed, particularly for performance horses. When it comes to reducing the risk of gastric ulcers, one of the main benefits is promoting chewing.

Saliva provides a natural buffer to stomach acid but unlike people, horses only produce saliva when they chew, which is why long periods without eating increase stomach acidity. In one study, the risk of non-glandular ulcers was found to be approximately 4 times higher in horses left for more than 6 hours without forage, although the risk may be greater during the day.

Research by Husted et al (2009) found gastric pH drops in the early hours of the morning, even in horses with free access to forage. Not only do horses generally stop eating/ grazing for a period of time during the early hours of the morning, they are normally less active at night, reducing the risk of gastric splashing.

It should also be remembered that forage is a source of fuel – even average hay fed at the minimum recommended amount may provide close to 45% of the published energy requirement for a horse in heavy exercise. Forage analysis can be a useful tool, especially if you can source a consistent supply.

Routine analysis normally includes measuring / calculating the water, energy and protein content, as well as providing an indication of how digestible the fibre is - more digestible forages yield greater amounts of energy and can help to reduce the reliance on feed.

Minimum forage intake

Ideally all horses, including racehorses in training should be provided with as much forage as they will eat. However large amounts of bucket feed, intense training and stress can affect appetite so voluntary intake (how much is eaten) should be monitored wherever possible.

In practice, this means weighing the amount of forage that’s provided, as well as any that is left in a 24-hour period. Ideally, total daily forage intake should not be restricted to less than 1.5% bodyweight per day on a dry matter basis, although an absolute minimum of 1.25% bodyweight (dry matter) is considered acceptable for performance horses, including racehorses in heavy training.

On an ‘as fed basis’ (the amount of forage you need to weigh out), this typically equates to (for a 500kg horse without grazing):

9kg of hay if it is to be fed dry or steamed (or an absolute minimum of 7.5kg)

11-12kg* of haylage (or an absolute minimum of 9-11kg*)

The difference in feeding rates can cause confusion but essentially, even unsoaked hay contains some water and the water doesn’t count towards the horse’s forage intake.

*based on a dry matter of 65-70%

How much starch and sugar is ‘too much’?

The fermentation of starch by bacteria in the stomach results in the production of volatile fatty acids which in conjunction with a low pH (acidic environment), increases the risk of ulcers forming. Current advice, which is based on published research, is to restrict non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) or ‘starch and sugar’ intake from ‘bucket feed’ to less than 1g per kilogram of bodyweight per meal and ideally less than 2g per kilogram of bodyweight per day. For a 500kg horse, this is equivalent to:

Less than 500g per meal

Ideally less than 1kg per day

Traditional racing feeds are based on whole cereal grains and as a result, are high in starch. By utilising oil and sources of highly digestible fibre such as sugar beet and soya hulls, feed manufacturers can reduce the reliance on cereal starch without compromising energy delivery.

Meal size matters

There are several reasons why horses should be fed small meals but one that’s of particular importance to managing the risk of gastric ulcers is reducing the amount of starch and sugar consumed in each meal.

Large meals may also delay gastric emptying and in turn, lead to increased fermentation of starch in the stomach, especially if cereal based. Restrict total feed intake to a maximum of 2kg per meal which is equivalent to approximately 1 Stubbs scoop of cubes.

Feeding ‘chaff’ to prevent gastric splashing

The horse’s stomach produces acid continuously (although at variable rate). Exercise increases abdominal pressure, causing acid to ‘splash’ onto the stomach lining in the non-glandular region where it increases the risk of ulcers forming. Exercise may also increase acid production.

Feeding short chopped fibre helps to prevent ‘gastric splashing’ by forming a protective ‘fibre mat’ on top of the contents of the stomach and may be of increased benefit to horses on restricted forage diets. Current advice is to feed 2 litres of short chopped fibre volume – equivalent to 1 Stubbs scoop – within the 30 minutes prior to exercise. Ideally choose a fibre containing alfalfa as the high protein and calcium content is thought to help buffer acid.

Supplements safety & efficacy

Supplements are often an attractive option, with owners and trainers from various disciplines reporting benefits. Unfortunately, scientific evidence is currently limited with some studies producing conflicting results which means specific recommendations regarding the optimum blend of ingredients and recommended daily intakes have not been established.

However, ‘ingredients’ that may help to support gastric health include pectin and lecithin, omega 3 fatty acids, fenugreek, threonine, liquorice and maerl, a marine derived source of bioavailable calcium. But don’t forget, there are some important safety considerations, both for horse health and mitigating the risk of prohibited substances.

Supplements should never be used as an alternative to veterinary treatment or an appropriate diet.

Beware of bold claims – if it sounds too good to be true it probably is!

It is illegal for manufacturers to claim products can cure, prevent or treat gastric ulcers. Words like ‘soothe’ and ‘improve’ are also prohibited. While bold or illegal claims do not automatically mean a supplement presents are unsafe, it does raise questions over the company’s ethics.

Speak to a nutrition advisor before feeding supplements containing added vitamins and minerals as some can be harmful (or even toxic) if oversupplied.

Avoid supplements (and feeds) containing added iron.

Be cautious of supplements containing iodine, including naturally occurring sources such as seaweed.

Ensure the total diet provides no more than 1mg selenium per 100kg bodyweight (5mg per day for a 500kg horse).

Natural does not always equal safe – avoid herbs of unknown origin.

In the UK, use only BETA® NOPS (British Equestrian Trade Association, Naturally Occurring Prohibited Substances) approved feeds and supplements.

Only use supplements produced by an authorised feed manufacturer (supplements are classified as feeds in the UK and the EU and regulated by the same legislation). Approval numbers must be included on the label but knowing what to look out for can be tricky. That said, any supplement carrying the BETA® EGUS approval mark will have been produced by an authorised manufacturer.

The BETA EGUS approval mark

Although they are by no means the only suitable option, you can be assured that feeds carrying the BETA® EGUS approval mark have been through a rigorous independent review process to ensure:

The combined starch and sugar content is less than 25% for high energy feeds and less than 20% for low-medium energy feeds

They provide less than 1g of starch and sugar (combined) per kilogram bodyweight per meal when fed as recommended

No inaccurate or medicinal claims are made on the packaging or in marketing materials

The feed is correctly labelled

It fulfils the nutrient specification – this includes independent laboratory analysis

Full references for scientific research available on request.

Trust your gut - the importance of feeding the gut microbiome for health, performance & longevity

Article by Dr. Richard McCormick, M.V.B., Dip. Eq.Sc., M.R.C.V.S.

The science of equine nutrition is really quite simple – The horse is a flight animal and in the wild, needs to be able to escape from predators using a short burst of energy. Nutrition and subsequent ‘energy’ for survival is all provided by grass which has the required balance of vitamins, minerals, immune supportive nutrients and fibre to maintain a healthy gut microbiota and keep the horse in adequate health for reproduction. Proper functioning of the gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) in horses is dependent on a broad range of micro-organisms and more than half of the energy requirement for their survival comes from the microbial fermentation occurring in their enlarged caecum and colon (Chaucheyras-Durand et al 2022). The bacterial populations resident in the various compartments of the horses intestinal tract vary greatly (Costa et al 2015) and there is more DNA in the bacteria located in the gastro-intestinal tract than there is in the entire body. Because of this, having a healthy gut flora is critical to having a healthy immune system.

In modern times, our demands of horses for performance for our pleasure rather than their survival has led to their need for increased energy that cannot be provided from grass alone. Because of this, the intricacies of diet (in particular the consumption of starch, fibre and fat) has come under scrutiny. Equine feed manufacturers have looked for additional sources of starch, a carbohydrate and a natural component of grass that is ‘essential to provide energy, fibre and a sense of fullness’ (Seitz 2022). Today, most horses and rapidly growing foals are commonly fed diets with >50% of total ration by weight in the form of grain ‘concentrates’ and carbohydrates from oats, maize, soya, barley and wheat. These grain based feeds contain high concentrations of soluble, easily fermentable starches but can be deficient in certain minerals and vitamins so getting an optimally balanced feed ‘right’ is difficult.

Too much of a good thing

With advances in scientific knowledge, we now know that when a horse is exposed to surplus starch, the hydrogen ion concentration of their gut increases promoting the production and absorption of lactic acid, acetate and propionate through the activity of fermentation (Ralston 1994). The process is quick, with lactic acid entering the bloodstream within 3 hours of feeding and calcium subsequently being excreted in the urine. In order to combat this nutrient loss, the horses’ hormone system triggers the release of parathyroid hormone into the bloodstream, activating the release of stored calcium (to maintain optimal blood levels) but unfortunately causing bone demineralisation. Clinically, the horse experiences health consequences of varying degrees including digestive diseases (eg: gastric ulcers, diarrhoea, colic or colitis), muscle dysfunction (eg: rhabdomyolysis (known as ‘tying up’), defective bone mineralization (expressed as increased incidence of stress fractures and developmental orthopaedic diseases), systemic diseases (such as laminitis, equine metabolic syndrome and obesity (Chaucheyras-Durand et al 2022) as well as potential causes of fatigue.

The ideal equine diet

There is little equine focused research available on the benefits of individual nutrients (due to limited numbers in trials and their subsequent evaluation) of grain ‘concentrates’. But we do know that ingredient availability and quality is regularly influenced by market pressures.

The table (fig 1) below outlines the sugar, starch and fibre components of the various ingredients commonly found in horse feeds. The optimal grain for equine nutrition with its efficient energy source through lower starch content (relative to other grains) and its high level of soluble fibre (relative to other grains) are oats.

Oats are highly digestible and do not require heat treatment or processing prior to feeding (unlike all other grains). They are the only grain that is easily digested raw and the least likely to cause insulin spikes and blood sugar fluctuations. Unfortunately, oats are not a ‘complete’ nutrient source as they are high in phosphorous and low in calcium. For adequate bone and muscle development as well as proper blood formation, oats must be balanced with additional vitamins and minerals.

The healing power of omegas and short chain fatty acids

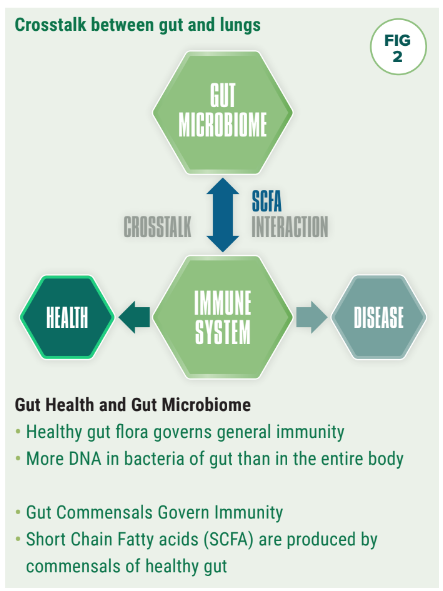

While grass provides optimal equine nutrition in its own right, the ‘curing process’ when making hay depletes the valuable omegas 3 and 6 intrinsic in grass. These ‘healing’ nutrients naturally protect the lining of the gastro-intestinal tract by increasing mucous production and alleviating ‘auto digestion’ (via hydrochloric acid). For horses, bacterial fermentation in the hind gut also results in the production of Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), namely acetic, proprionic and butyric acids. These SCFAs ‘cross talk’ with the gut immune system providing local immunity in the gut as well as protection of the respiratory system, the brain and other tissues against disease. In human medicine, it has been repeatedly established that a dysfunctional gut microbiome is associated with respiratory problems. This is evidenced by the fact that when gut disorders such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBD) or Coeliac disease exist in humans, they are commonly associated with a higher incidence of respiratory infections and related asthmatic like conditions. Barragry (2024) explores the relationship (Fig 2) between gut microbiome and the immune system's ability to support health and combat disease in cattle. A scenario mirrored in the equine.

The stabled horse should be provided with SCFAs daily to support proper functioning gut microbiome. This critical dietary consideration should ideally be provided in the form of flaxseed which has the highest ratio of omegas 3 and 6 (in the ideal ratio 4:1) in the plant world and is most suitable for the equine herbivore.

The health benefits of flaxseed for both humans and equines has been recognised as early as 3,000 BC. Flaxseed was used for various medicinal purposes such as the treatment of gastric disorders, as a soothing balm for inflammation and as a laxative (Judd, 1995). Horsemen (who relied heavily on their equines) and trainers (who sought optimal performance from their charges through natural means) also used flaxseed as a way to supplement the diet with omega-3’s and fibre to produce high quality proteins. Now, thirteen centuries later, we have research to substantiate the knowledge of our ancestors. The renowned German researcher of ‘fats’ and pioneer in human nutrition, Dr. Joanna Budwig, as early as the 1950’s reported that “the absence of highly unsaturated fatty acids causes many vital functions to weaken". Dr. Budwig’s life’s work focused on the dietary ‘imbalance’ between omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in humans has been a cornerstone to the exploration of the role of inflammation and the development of many diseases of the coronary, respiratory, metabolic and immune system.

The small seed of the flax plant is also an excellent source of high-quality protein (exceeding that of soybeans and fish oils) and potassium (a mineral that’s important for cell and muscle function). But, the true power of flaxseed lies in three key components:

Omega-3 essential fatty acids – Also known as "good" fats, omegas enhance the oxygen usage of cells and in combination with alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) are anti-inflammatory in their effect within the body.

Lignans – Flaxseed contains 750 - 800 times more lignans than other plant foods (McCann 2007, Yan 2014). Lignans are a group of compounds with antioxidant properties which also contain plant oestrogen. Lignans are linked to a reduced risk of developing osteoporosis, heart disease and cancer.

Fibre - Flaxseed contains both the soluble and insoluble types of fibre essential for maintaining ‘gut’ health.

In equines, adding flaxseed to the diet has the immediate benefits of a shiny, healthy coat and fewer skin allergies. Consistent use of flaxseed has multiple long term benefits including strong hoof quality, improved joint health, reduced muscle soreness, faster healing of ulcers (Sonali et al 2008) and significantly impacts inflammation associated with chronic skin conditions (commonly known as ‘sweet itch’). In breeding stock, increased Omega-3 levels in mares’ milk leads to boosted immunity in foals with higher stallion fertility and improved conception rates in broodmares documented (Holmes, 2015).

How diet can influence performance

It is easy to think that ‘providing more is better’ when it comes to using nutrition to support performance. But having excess levels of essential vitamins and minerals being processed by the horses’ sensitive gut has a direct impact on their behaviour and willingness to perform. Today, we have greater ‘choice’ at the feed store with a broad range of commercial feeding offerings available including mixes, mashes and supplements but the discerning horse owner can be forgiven for being overwhelmed by the range of diet options for every ailment and stage of life.

In modern times, despite advances in nutrition offerings, we have seen a falloff in performance (Fig 3). During the late 1960s, the U.S. Jockey Club stats noted that racehorses averaged 12 starts per year – a far cry from today's horses racing in the U.S. where the average of 3 ‘starts’ was highlighted by leading US Trainers in 2020 (www.ownerview.com). Unfortunately, this is not just a U.S. based problem, but a phenomenon noted worldwide.

The first equine pelleted feed was formulated in the US by the Cistercian monks in Gethsemani, Kentucky in 1957. Prior to this, all horses were fed ‘straights’ (primarily oats as their energy source and flaxseed as their protein source). My own understanding of the link between modern feeding practices and compromised performance since the 1960s has been curated off an understanding of “what was different” then, as well as a career of observations, clinical practice and scientific review. Fact is, the equine diet of the 1960s was lower in starch and high in fibre. It consisted of oats, minerals, and flaxseed as the “norm”. Hay was the preferred forage (Fig 4).

Today, soya (with one fifth of the omega 3 content of flaxseed) has practically replaced flaxseed as the protein source in equine nutrition. This small change has seen a significant drop in omega-3 and 6 (needed for prostaglandins) in the diet with consequential gastro-intestinal and joint issues. Other dietary changes include those recommended by the National Research Council (NRC) in 1978, who suggested doubling the recommended calcium levels for horses with a subsequent increase in levels of Osteochondrosis (OCD) and Osteopetrosis in the equine population (Krook and Maylin, 1989). Additional moisture in the diet too has led to excess mould formation in convenience feeds and with severe exposure causes liver damage (Buckley et al 2007). Stabled racehorses today mostly lack the nutritional protection afforded a previous generation of horses. The impact has been noted clinically in the widespread increase in equine gastric issues and as stated by J.E. Anthony “Racing fans are missing about half of what they once enjoyed in racing.”

The role of the gut bacteria in the prevention of disease

The gut microbiome begins populating and diversifying from the moment of birth. Though ‘sterile’ in utero, gut derived DNA immediately drives immune health with exposure to nutrition. Recent research suggests that the gut microbiome can be stimulated by using proven probiotics with a track record in enhancing gut health (Barragry 2024). But it is the protective power of SCFAs to allow ‘cross talk’ between the lungs and the gut microbiome that is critical to supporting horses through their lifespan.

Nutrition using grain ‘concentrates’ is currently at approximately 99% saturation in today’s equine population so a return to feeding ‘straights’ is a swim against the tide of modernity. But, knowing the influence of nutrition on health, performance and longevity it falls on horse owners to be mindful of the consequential impacts such convenience feeds have on the gut microbiome and immune system. Random supplementation and high starch feeds are leading to dietary health issues such as gastric ulcers, hyperinsulinemia and hyperlipaemia (obesity) as well as increased risk of laminitis . So trust your gut and keep it simple – a diet of oats, flaxseed, a multi-vitamin balancer and ad lib hay will not only meet your horses’ energy needs but will keep them happy and healthy too.

REFERENCES

Barragry. TB (2024) WEB https://www.veterinaryirelandjournal.com/focus/254-alternatives-to-antibiotics-probiotics-the-gut-microbiome-and-immunity

Buckley T, Creighton A, Fogarty (2007) U. Analysis of Canadian and Irish forage, oats and commercially available equine concentrate feed for pathogenic fungi and mycotoxins. Ir Vet J. 2007 Apr 1;60(4):231-6. doi: 10.1186/2046-0481-60-4-231. PMID: 21851693; PMCID: PMC3113828.

Budwig, Dr. J (1903-2008) WEB https://www.budwig-stiftung.de/en/dr-johanna-budwig/her-research.html

Chaucheyras-Durand F, Sacy A, Karges K, Apper E (2022). Gastro-Intestinal Microbiota in Equines and Its Role in Health and Disease: The Black Box Opens. Microorganisms. 2022 Dec 19;10(12):2517. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10122517. PMID: 36557769; PMCID: PMC9783266. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9783266/

Holmes, R (2015) Feeding for stallion fertility. WEB

https://www.theirishfield.ie/feeding-for-stallion-fertility-172113/

Judd A (1995) Flax - Some historical considerations. Flaxseed and Human Nutrition, S C Cunnane, L U Thompson. AOCS Press, Champaign, IL 1995; 1–10 [Google Scholar]

Martinac, P (2018) What are the benefits of flaxseed lignans? WEB https://healthyeating.sfgate.com/benefits-flaxseed-lignans-8277.html

National Research Council. 1989. Nutrient Requirements of Horses. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

Ralston, S VMD, PhD, ACVN (1994) The effect of diet on acid-base status and mineral excretion in horses in the Journal of Equine Practice. Vol 16 No. 7. Dept of Animal Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08903

Seitz, A (2022) What to know about starch_Medically reviewed by Seitz, A - MS, RD, LDN, Nutrition — WEB https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-is-starch#benefits

Sonali Joshi, Sagar Mandawgade, Vinam Mehta and Sadhana Sathaye (2008) Antiulcer Effect of Mammalian Lignan Precursors from Flaxseed, Pharmaceutical Biology, 46:5, 329-332, DOI: 10.1080/13880200801887732

Equine Nutrition - be wary of false feeding economies

Article by Louise Jones

Many horses, especially performance horses, breeding stallions, and broodmares at certain stages of production, require additional calories in the form of hard feed. Whilst in the current economic climate, with rising costs and inflation, it might be tempting to look at lower cost feeding options; in reality, this could be a false economy. When choosing a feed, in order to ensure that you are getting the best value for money and are providing your horses with the essential nutrients they require, there are a number of factors to consider.

Quality

The ingredients included in feed are referred to as the raw materials. These are usually listed on the feed bag or label in descending order by weight. Usually they are listed by name (e.g., oats, barley wheat) but in some cases are listed by category (e.g., cereals). Each raw material will be included for a specific nutritional purpose. For example, full-fat soya is a high-quality source of protein, whilst cereals such as oats are mainly included for their energy content, also contributing towards protein, fibre and to a lesser degree, fat intake.

Waste by-products from human food processing are sometimes used in the manufacture of horse feed. Whilst it is true that they do still hold a nutritional value, in most cases they are predominantly providing fibre but contain poor levels of other essential nutrients. Two of the most commonly used by-products are oatfeed and distillers grains. Oatfeed is the fibrous husks and outer layer of the oat and it mainly provides fibre. Distillers grains are what is left over after yeast fermentation of cereal grains used to produce alcohol. The leftover grain is dried and used in the feed industry as a protein source. Distillers grains can be high in mycotoxins, which are toxic chemicals produced by fungi in certain crops, including maize. Furthermore, despite being used as a protein source, distillers grains are typically low in lysine. As one of the first limiting amino acids, lysine is a very important part of the horse’s diet; horses in work, pregnant mares and youngstock all have increased lysine requirements.

Another ingredient to look out for on the back of your bag of feed is nutritionally improved straw, often referred to as “NIS”. This is straw that has been treated with chemicals such as sodium hydroxide (caustic soda) to break down the structural fibre (lignins) and increase its digestibility. Straw is a good example of a forage which contains filler fibre; in fact, you can think of it as the horse’s equivalent of humans eating celery. Traditionally, oat straw was used to make NIS, however many manufacturers now use cheaper wheat or barley straw due to the rising cost of good quality oat straw. Not all companies state what straw is used and instead use generic terms such as cereal straw, which again, allows them to vary the ingredients used depending on cost and availability.

By law, feed manufacturers must declare certain nutrients on the feed bag, one of which is the percentage crude protein. This tells you how much protein the feed contains. However, not all protein is created equal; some protein is of very high quality, whilst other proteins can be so low in quality that they will limit a horse’s ability to grow, reproduce, perform or build muscle. Protein ‘quality’ is often measured by the levels of essential amino acids (e.g., lysine, methionine) it contains. In most cases feed manufacturers do not have to list the amount of these essential amino acids; but looking at the ingredient list will give you a clue as to how good the protein quality is. Good sources of high-quality protein include legumes and soybean meal, whereas by-products often contain moderate- or low-quality protein, even though they may be relatively high in crude protein.

Understanding more about the ingredients in your bag of horse feed will help you to assess whether they are providing good, quality nutrition. Feeds containing large proportions of lower quality ingredients will obviously be cheaper, but this could compromise quality of the products. The goal therefore is to ensure that the nutritional makeup of the products remains high quality and consistent.

Cooking for digestibility

Digestibility is a term used to describe the amount of nutrients that are actually absorbed by a horse and are therefore available for growth, reproduction, and performance. Understanding digestibility of energy sources—such as fibre, fat, starch, and sugar as well as protein, vitamin and mineral digestibility—is important when devising optimal diets for horses.

Most of the energy in grains is contained in the starch; however, horses cannot fully digest starch from uncooked (raw) grains in the small intestine, which results in this undigested starch traveling into the hindgut where it will ferment and potentially cause hindgut acidosis. Therefore, in order to maximise pre-caecal digestibility, feed manufacturers cook the grain. Similarly, soya beans must be carefully processed prior to feeding them to horses. This is because raw soybeans contain a specific enzyme that blocks the action of trypsin, an enzyme needed for protein absorption.

There are various methods of cooking including pelleting, micronizing, extrusion, and steam-flaking. This is a fine art as, for example, undercooking soya beans will not deactivate the enzymes correctly, thus resulting in reduced protein absorption. On the other hand, overcooking will destroy essential amino acids such as lysine, methionine, threonine, and possibly others.

Variation in cooking methods, and hence digestibility, can have a direct impact on how the finished product performs. Your individual feed manufacturer should be able to tell you more about the cooking processes they use to maximise digestibility.

Micronutrient and functional ingredients specification

The back of your bag of feed should list the inclusion of vitamins, such as vitamin E, and minerals including copper and zinc. A lower vitamin and mineral specification is one way feed companies can keep the cost of their products down. For example, the vitamin E level in one unbranded Stud Cube is just 200 iu/kg—50% lower than in a branded alternative.

For most vitamins and minerals, the levels declared on the back of the bag/label only tell the amount actually added and do not include any background levels provided by the raw materials. In other marketing materials, such as brochures, some companies will combine the added figure with the amount provided by other raw materials in order to elevate the overall figure. For example, a feed with 50 mg/kg of added copper may list the total copper as 60 mg/kg on their website or brochure. Whilst it is perfectly acceptable to do this, it is equally important to recognise that background levels in different raw materials can vary and hence should not be relied upon to meet requirements. To complicate this slightly further, chelated minerals (e.g., cupric chelate of amino acids hydrate, a copper chelate) may be included. Chelated minerals have a higher bioavailability, and so a feed with a high inclusion of chelated copper may perform as well as one that has an even higher overall copper level but does not include any chelates.

Equally important is the need to verify that any specific functional ingredients such as prebiotics or yeast are included at levels that are likely to be efficacious.

Feeding rates

Whilst the cost of a bag of feed is undeniably important, another aspect that should be considered is the amount of feed required to achieve the desired body condition and provide a balanced diet. Feeding higher volumes of hard feed not only presents a challenge from a gastrointestinal health point of view but also increases the cost per day of feeding an individual. For example, the daily cost of feeding 8kg of a feed costing £400/€460 per tonne vs 5¼ kg of a feed costing £600/€680 per tonne are exactly the same. Plus, the lower feeding rate of the more expensive product will be a better option in terms of the horse’s digestive health, which is linked to overall health and performance. To keep feeding costs in perspective, look at the cost of feeding a horse per day rather than relying on individual product prices.

Consistency

When a nutritionist creates a recipe for a horse feed, they can either create a ‘set recipe’ for the feed or a ‘least cost formulation’. A set recipe is one that doesn’t change and will use exactly the same ingredients in the same quantities. The benefit of this is that you can rest assured that each bag will deliver the same nutritional profile as the next. However, the downside is that if the price of a specific ingredient increases, unfortunately, so will the cost of the product.

On the other hand, least-cost formulations use software to make short-term recipes based on the cost of available ingredients. It will use the cheapest ingredient available. When done correctly, they will provide the amount of calories (energy), crude protein, vitamins and minerals as specified on the label. However, the ingredients will change, and protein quality can be compromised. Often feed companies using least-cost formulations will print their ingredients on a label, rather than the bag itself, as the label can be amended quickly and cheaply, should they alter the recipe.

Checking the list of ingredients in your feed regularly should alert you to any formulation changes. Equally look out for feeds that include vague ingredient listings such as ‘cereal grains and grain by-products, vegetable protein meals and vegetable oil’; these terms are often used to give the flexibility to change the ingredients depending on how costly they are.

Peace of mind

Another important issue is that some companies producing lower-cost feeds may not have invested in the resources required to carry out testing for naturally occurring prohibited substances (NOPS) such as theophylline, banned substances (e.g., zilpaterol - an anabolic steroid) or mycotoxins (e.g., zearalenone). It is true that, even with the most stringent testing regime, identifying potential contamination is difficult; and over recent years, a number of feed companies have had issues. However, by choosing a feed manufacturer who is at the top of their game in terms of testing and monitoring for the presence of such substances will give you peace of mind that they are aware of the threat these substances pose, and they are taking significant precautions to prevent their presence in their products. It is important to source horse feed from a BETA NOPS registered feed manufacturer at a minimum. It may also be prudent to ask questions about the feed manufacturer’s testing regime and frequency of testing.

Supplements – to use or not to use?

A good nutritionist will be able to assess any supplements that are fed, making note of why each is added to the diet and the key nutrients they provide. It is easy to get stuck into the trap of feeding multiple supplements that contain the same nutrients, effectively doubling up on intake. Whilst in many cases this isn’t nutritionally an issue, it is an ineffective financial spend. For example, B vitamins can be a very useful addition to the diet, but if provided in levels much higher than the horse needs, they will simply be excreted in the urine. Reviewing the supplements you are feeding with your nutritionist to ensure they are essential and eliminating nutritional double-ups is one of the simplest ways to shave off some expense.

Review and revise

A periodic review of your horse’s diet ensures that you’re providing the best nutrition in the most cost-effective way. This will require the expertise of a nutritionist. Seeking advice on online forums and social media is not recommended as this can lead to misinformed, biased advice or frankly, dangerous recommendations. On the other hand, a properly qualified and experienced nutritionist will be able to undertake a thorough diet evaluation, carefully collecting information about forages, concentrates, and supplements.

Working with a nutritionist has many advantages; they will be able to work with you to ensure optimal nutrition, whilst also helping to limit needless expenses. Some nutritionists are better than others, so choose wisely. (Does the person in question have the level of qualifications?) Bear in mind that while qualifications can assure you that the nutritionist has rigorous science-based training, experience is also exceptionally important. Ask them about their industry experience and what other clients they work with to ensure they have the right skill set for your needs. In addition, a competent nutritionist will be willing and able to interact with your vet where and when required to ensure that the health, well-being, and nutrition of your horses is as good as it can be.

There are independent nutritionists available, but you will likely incur a charge—often quite a significant one. On the other hand, the majority of feed companies employ qualified, experienced nutritionists and offer their advice, free of charge.

Nutrition and the new science of the "Gut-Brain connection"

Article by Scott Anderson

Trainers are always looking to gain an edge in performance. But what about their mental state? Are they jittery, distracted or disinterested? No matter how strong the horses, their heads must be in the game to succeed.

Surprisingly, much of that mental attitude is driven by gut health, which in turn depends on the collection of microbes that live there: the microbiota. In a horse, the microbiota is a tightly packed community of about 100 trillion microbes, composed of bacteria, archaea, fungi and protozoa. It colonises the entire GI tract but is largely concentrated in the hindgut, where it works to ferment the prebiotic fibre in forage. The microbial fermentation of fibre into fatty acids produces 70% of the animal’s energy requirements and without it, the horse couldn’t get sufficient energy from simple forage. Intriguingly, byproducts of that fermentation can affect the brain.

It is easy to be sceptical about this gut-brain connection, but over the last decade, research has made it clear that gut microbes have an outsized influence on mood and behaviour. Microbes that improve mental state are called psychobiotics, and they may completely change the way you train and manage your horses. A horse’s health – and consequently its performance – starts in the gut.

Inflammation

When the microbiota is unbalanced by stress, diet or sickness, it is said to be dysbiotic. It loses diversity, and a handful of bacterial species compete for domination. Without the pushback of a diverse population, even beneficial bacteria can become pathogenic. Surprisingly, that can affect the brain. Multiple studies in various animal models have shown that transmitting faecal matter from one animal to another also transmits their mood. This demonstrates that a dysbiotic microbiota can reliably cause mental issues including anxiety and depression, thereby affecting performance.

An important function of the microbiota is to fight off pathogens by outcompeting, starving or killing them. However, a dysbiotic microbiota is less diligent and may permit pathogens to damage the gut lining. A degraded gut lining can leak, allowing bacteria and toxins into the bloodstream. The heart then unwittingly pumps them to every organ in the body, including the brain. This makes the gut the primary source of infection in the body, which explains why 80% of the immune system is located around the intestines. Over time, a leaky gut can lead to chronic systemic inflammation, which weakens the blood-brain barrier and interferes with memory, cognition and mood.

Inflammation is a major component of the gut-brain connection, but not the only one.

Neurotransmitters and hormones

Horses and humans use neurotransmitters to communicate between nerve cells. Brains and their attendant nerve bundles constitute a sophisticated network, which makes it somewhat alarming that microbes also produce neurotransmitters. Microbes use neurotransmitters to converse with each other, but also to converse with their host. The entire gut is enmeshed in nerve cells that are gathered up into the vagus nerve that travels to the brain. Microbial neurotransmitters including serotonin and dopamine thus allow certain microbes to communicate directly with the brain via the vagus nerve. We know this happens with specific bacteria, including Lactobacillus species, because when the vagus is severed, their psychobiotic effects disappear.

As well as neurotransmitters, hormones are involved in gut-brain communications. The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis controls the stress response in animals. The hypothalamus is located low in the brain and responds to stressors – such as a lurking predator – by producing hormones that stimulate the neighbouring pituitary, which then triggers the adrenal gland to produce cortisol, the stress hormone. Cortisol acts as a threat warning and causes the horse to ramp up glucose production, supplying the energy needed to escape a predator. This is the same hormonal circuit that trainers exploit for racing.

The HPA axis produces cortisol in response to stress. Cortisol inhibits the immune system, which in combination with a leaky gut allows pathogens to enter the bloodstream. Susequent systemic inflammation and vagal feedback lead to stereotypies.

The production of these hormones redirects energy to the heart, lungs and muscles at the expense of the immune system. From an evolutionary point of view, the tradeoff makes sense: first escape the predator and deal with infections later. After the danger has passed, cortisol causes the HPA to return to normal – the calm after the storm.

However, continued stress disrupts that cycle, causing anxiety and diminishing the brain’s ability to store memories. This can dramatically interfere with training. Stress can also induce the release of norepinephrine, which promotes the growth of pathogenic bacteria including Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria, Helicobacter pylori, and Salmonella. Prolonged high cortisol levels can increase gut leakiness, potentially leading to infection and further compounding the situation. In the long term, continued stress leads to systemic inflammation, which is a precursor to problematic behaviours.

Short-chain fatty acids

When microbes consume proteins and fibre, they break them down into their constituent molecules, such as amino acids, fatty acids and sugars. These are the metabolites of the microbes. As well as neurotransmitters and hormones, the gut-brain conversation is mediated by metabolites like butyrate, an important short-chain fatty acid which plays multiple roles in the body.

In the gut, butyrate serves as a preferred nutrient for the cell lining. It encourages the differentiation of stem cells to replenish gut cells that are routinely sloughed off or damaged. It plays an important role in the production of mucus – an essential part of gut protection – which coats the gut from mouth to anus. In the muscles, butyrate boosts the growth of skeletal muscle, crucial to athletic performance, as well as inducing the production of glucose, the primary muscle fuel. One-quarter of systemic glucose is driven by butyrate. In its gut-brain role, butyrate passes through the blood-brain barrier, where it nourishes and enhances the growth of new brain cells.

These factors make butyrate a star player in the gut-brain connection. They also highlight the benefits of prebiotic fibre, especially when high-energy, low-fibre feeds are provided.

Starting a microbiota

We’ve explored the major pathways of the gut-brain connection: inflammation, neurotransmitters, hormones and fatty acids. Some of these pathways are at odds with each other. How does such a complicated system come together?

As mentioned, the microbiota is an animal’s first line of defence against pathogens, attacking and killing them often before the immune system is even aware of them. That means a healthy microbiota is an essential part of the immune system. However, the immune system is designed to attack foreign cells, which includes bacteria. For the microbiota to survive, the immune system must therefore learn to accept beneficial microbes. This lesson in tolerance needs to take place early in the foal’s development, or its immune system may forever fight its microbiota.

There are multiple ways nature ensures that foals get a good start on a microbiota that can peacefully coexist with the immune system. The first contribution to a protective microbiota comes from vaginal secretions that coat the foal during birth. After birth, microbes are included in the mare’s milk. These microbes are specially curated from the mare’s gut and transported to the milk glands by the lymphatic system. Mare’s milk also includes immune factors including immunoglobulins that help the foal to distinguish between microbial friends and foes. An additional way to enhance the microbiota is through coprophagia, the consumption of manure. Far from an aberration, foals eat their mother’s manure to buttress their microbiota.

Microbes affect the growth and shape of neurons in various brain sites as the foal develops – a remarkable illustration of the importance of a healthy early gut microbiota.

The cooperation between the immune system and the microbiota is inevitably complex. Certain commensal bacteria, including Clostridiales and Verrucomicrobia, may be able to pacify the immune system, thus inhibiting inflammation. This is a case where microbes manage the immune system, not the other way around. These convoluted immune-microbial interactions affect the mental state – and consequently the behaviour – of the horse, starting at birth.

Stereotypies

A 2020 study of 185 performance horses conducted by French researchers Léa Lansade and Núria Mach found that the microbiota, via the gut-brain connection, is more important to performance than genetics. They found that microbial differences contributed significantly to behavioural traits, both good and bad. A diversified and resilient microbiota can help horses better handle stressors including stalling, training, and trailering. A weakened or dysbiotic microbiota contributes to bad behaviours (stereotypies) and poor performance.

The horses in this study were all carefully managed performance horses, yet the rates of stereotypies were surprisingly high. A kind of anxiety called hypervigilance was observed in three-quarters of the horses, and almost half displayed aggressive behaviour like kicking or biting.

The study found that oral stereotypies like biting and cribbing were positively correlated with Acinetobacter and Solibacillus bacteria and negatively correlated with Cellulosilyticum and Terrisporobacter. Aggressive behaviour was positively correlated with Pseudomonas and negatively correlated with Anaeroplasma.

Some of these behaviours can be corrected by certain Lactobacillus and Bacteroides species, making them psychobiotics. That these personality traits are correlated to gut microbes is truly remarkable.

Intriguingly, the breed of a horse has very little impact on the makeup of its microbiota. Instead, the main contributor to the composition of the microbiota is diet. Feeding and supplements are thus key drivers of the horse’s mental state and performance.

The gut-brain connection and training

How might the gut-brain connection affect your training practices? Here are some of the unexpected areas where the gut affects the brain and vice-versa:

High-energy feed. Horses evolved to subsist on low-energy, high-fibre forage and thus have the appropriate gut microbes to deal with it. A high-energy diet is absorbed quickly in the gut and can lead to a bloom in lactic acid-producing bacteria, which can negatively impact the colonic microbiota. High-energy feeds are designed to improve athletic output, but over time, too much grain can make a horse antisocial, anxious and easily spooked. This can damage performance—the very thing it is trying to enhance. Supplementary prebiotics may help to rebalance the microbiota on a high-starch regimen.

Changing feed regimens quickly. When you change feed, certain microbes will benefit, and others will suffer. If you do this too quickly, the microbiota can become unbalanced or dysbiotic. Slowly introducing new feeds helps to prevent overgrowth and allows a balanced collection of microbes to acclimate to a new regimen.

Stress. Training, travelling and racing all contribute to stress in the horse. A balanced microbiota is resilient and can tolerate moderate amounts of stress. However, excessive stress can lead, via the HPA axis, to a leaky gut. Over time, it can result in systemic inflammation, stereotypies and poor performance.

Overuse of antibiotics. Antibiotics are lifesavers but are not without side effects. Oral antibiotics can kill beneficial gut microbes. This can lead to diarrhoea, adversely affecting performance. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiota can last for weeks and may contribute to depression and anxiety.

Exercise and training. Exercise has a beneficial effect on the gut microbiota, up to a point. But too much exercise can promote gut permeability and inflammation, partly due to a lack of blood flow to the gut and consequent leakiness of the intestinal lining. Thus, overtraining can lead to depression and reduced performance.

Knowing how training affects the gut and how the gut affects the brain can improve outcomes. With a proper diet including sufficient prebiotic fibre to optimise microbiota health, a poor doer can be turned into a model athlete.

References

Mach, Núria, Alice Ruet, Allison Clark, David Bars-Cortina, Yuliaxis Ramayo-Caldas, Elisa Crisci, Samuel Pennarun, et al. “Priming for Welfare: Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Equitation Conditions and Behavior in Horse Athletes.” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (May 20, 2020): 8311.

Bulmer, Louise S., Jo-Anne Murray, Neil M. Burns, Anna Garber, Francoise Wemelsfelder, Neil R. McEwan, and Peter M. Hastie. “High-Starch Diets Alter Equine Faecal Microbiota and Increase Behavioural Reactivity.” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1 (December 9, 2019): 18621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54039-8.

Lindenberg, F., L. Krych, W. Kot, J. Fielden, H. Frøkiær, G. van Galen, D. S. Nielsen, and A. K. Hansen. “Development of the Equine Gut Microbiota.” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1 (October 8, 2019): 14427.

Lindenberg, F., L. Krych, J. Fielden, W. Kot, H. Frøkiær, G. van Galen, D. S. Nielsen, and A. K. Hansen. “Expression of Immune Regulatory Genes Correlate with the Abundance of Specific Clostridiales and Verrucomicrobia Species in the Equine Ileum and Cecum.” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1 (September 3, 2019): 12674.

Daniels, S. P., J. Leng, J. R. Swann, and C. J. Proudman. “Bugs and Drugs: A Systems Biology Approach to Characterising the Effect of Moxidectin on the Horse’s Faecal Microbiome.” Animal Microbiome 2, no. 1 (October 14, 2020): 38.

Why a lack of fibre can compromise horse health and performance

Why a lack of fibre can compromise horse health and performance

Gastric ulcers can affect any horse or pony regardless of age, breed, sex and discipline. In fact, it has been estimated that up to 90% of racehorses have ulcers. Clare Barfoot RNutr, Marketing and Research and Development Director at SPILLERSTM explains why……

The problem with stomach acid

The horse has evolved to eat for up to 18 hours a day, with 65% of the gut devoted to digesting fibre. The horse’s stomach produces acid continuously, but they can only produce acid-neutralising saliva when they chew. This means horses on a restricted fibre diet such as racehorses that limited access to forage are more susceptible to gastric ulcers. Feeding meals high in cereals can also increase the risk of gastric ulcers due to excess fermentation in the stomach. Exercise itself may increase gastric acid production and it also increases pressure in the abdomen, which can result in gastric acid ‘splashing’ onto the upper region of the stomach.

The benefits of forage

The key to reducing the risk of ulcers is to provide as much of the diet as possible as forage (no less than 15g/kg bodyweight dry weight per day) this means 9kg of hay for the average racehorse, whilst restricting starch intake to less than 2g/kg bodyweight per day (1g/kg bodyweight per meal). Feeding plenty of forage and/or chopped fibre forms a protective mat on top of the stomach contents, thus helping to prevent ‘gastric splashing’. It also helps to add chopped fibre to help extend eating time and increase saliva production. Alfalfa is particularly useful as the high protein and calcium content may help to buffer stomach acid.

How SPILLERSTM Ulca Fibre can help

SPILLERS Ulca Fibre contains short-chopped alfalfa to extend eating and chewing time, encouraging saliva production and increasing the horse’s ability to buffer damaging stomach acid. The high oil content gives slow release energy for optimum condition and a full range of vitamins and minerals includes vitamin E for immune support and muscle health. High-quality protein includes lysine to support muscle development and performance. SPILLERS Ulca Fibre can be fed on its own or in addition to a suitable low starch compound feed such as SPILLERS Ulca Power Cubes.

SPILLERS Ulca Fibre was used alongside SPILLERS HDF Power Cubes in a recent scientific study that was the first to prove that diet can have a beneficial effect on gastric health. Horses that were clinically treated for grade three and four ulcers were split into two groups; one group had their diet changed at the start of omeprazole treatment, while the other remained on the pre-treatment diet.

The dietary change group maintained their improved ulcer score post treatment, whereas overall the horses in the group remaining on the pre-treatment diet regressed back to their pre-treatment ulcer scores, proving the value of dietary management in reducing the risk of ulcers.

SPILLERSTM Ulca Power Cubes

SPILLERS has also launched SPILLERS Ulca Power Cubes, a high energy, low starch cube for racing and performance horses prone to gastric ulcers. Based on SPILLERS HDF Power Cubes which are a favourite in the racing industry, SPILLERS Ulca Power Cubes are just 12% starch and have added functional ingredients to support gastric health. They are ideal to feed alongside a chopped fibre containing alfalfa to help extend eating time and buffer stomach acid.

Both products carry the BETA EGUS Approval Mark demonstrating they have been independently assessed as suitable for horses prone to gastric ulcers.

* Luthersson N, Bolger C, Fores P , Barfoot C, Nelson S, Parkin TDH & Harris P (2019) Effect of changing diet on gastric ulceration in exercising horses and ponies following cessation of omeprazole treatment JEVS 83 article 102742

To find out more about our feeds and how we can help to support your racing yard, please visit our website www.spillers-feeds.com or call/email one of our dedicated Thoroughbred Specialists.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Why the fibre you feed matters

It’s not only what’s in a feed that’s important, where it comes from matters too.

A great source of calcium

Alfalfa is an effective buffer to acidity in the gut due to its abundance in calcium and studies have shown it buffers acidity more effectively than grass-based forages. Just half a scoop of pure alfalfa chopped fibre in each feed will help counteract the acidity produced by feeding cereals.

A study has shown that omeprazole can negatively impact calcium absorption – this has already been shown in humans. Whether this is contributing to an increased risk of bone fractures is yet to be confirmed but it is certainly worth providing additional calcium in the ration as a risk reduction strategy. The calcium in alfalfa is highly bioavailable and so easier for the horse to absorb. Just 1 scoop of Dengie Alfa-A Original provides a 500kgs exercising horse with 1/5th of their daily calcium requirement*.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) such as omeprazole have also been shown to significantly impact the bacterial populations in the digestive tract of humans making them more prone to digestive upsets and infections. This hasn’t been explored in the horse to date but if the same effect is seen it reiterates the importance of doing everything else possible to promote good gut health.

Consistently Clean

When the difference between winning and losing is marginal, doing everything you can to maximise respiratory health and function makes sense. Precision drying is a way of conserving forages that ensures they are as clean as possible and helps to lock-in nutrients as well. Every bag of Dengie fibre is dried by us and we can trace each one back to the field it was grown in.

Many people don’t realise that some so-called performance feeds contain straw. At Dengie we believe straw is a useful ingredient but not for the performance horse! It’s simply a case of using the right fibre for the right horse. Our feeds are regularly tested for mould with levels routinely below 100 CFUs and often below 10CFUS. To put that in context, sun-dried forages such as hay and straw often contain 1000CFUS or more.

Tempting the fussy racehorse

Findings from our Senior Nutritionist’s PhD research suggests that hospitalised Thoroughbreds are more likely to go off their feed than other breeds even when gastric ulcers have been ruled out. Interestingly, previous studies have also found that Thoroughbreds experience a higher rate of post-anaesthetic gastrointestinal complications such as colic, reduced faecal output and colitis compared to non-Thoroughbred horses. Dengie Performance Fibre has been developed to try to tempt even the fussiest horse and has proven to be particularly successful.

*Based on NRC guidance for a 500kgs horse in exercise and a calcium level of 1.5% in alfalfa

For further information please visit www.dengie.com or call +44 (0)1621 841188

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.