Trust your gut - the importance of feeding the gut microbiome for health, performance & longevity

Article by Dr. Richard McCormick, M.V.B., Dip. Eq.Sc., M.R.C.V.S.

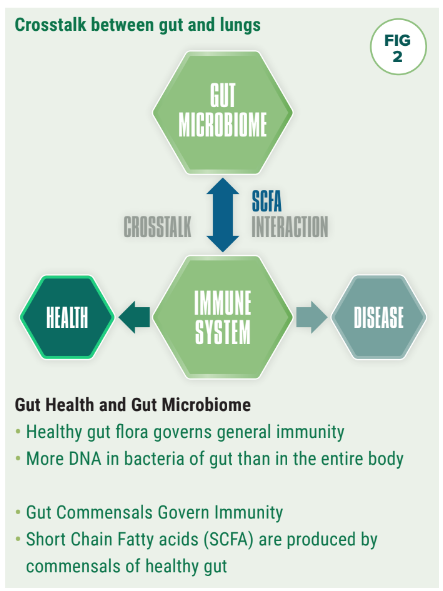

The science of equine nutrition is really quite simple – The horse is a flight animal and in the wild, needs to be able to escape from predators using a short burst of energy. Nutrition and subsequent ‘energy’ for survival is all provided by grass which has the required balance of vitamins, minerals, immune supportive nutrients and fibre to maintain a healthy gut microbiota and keep the horse in adequate health for reproduction. Proper functioning of the gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) in horses is dependent on a broad range of micro-organisms and more than half of the energy requirement for their survival comes from the microbial fermentation occurring in their enlarged caecum and colon (Chaucheyras-Durand et al 2022). The bacterial populations resident in the various compartments of the horses intestinal tract vary greatly (Costa et al 2015) and there is more DNA in the bacteria located in the gastro-intestinal tract than there is in the entire body. Because of this, having a healthy gut flora is critical to having a healthy immune system.

In modern times, our demands of horses for performance for our pleasure rather than their survival has led to their need for increased energy that cannot be provided from grass alone. Because of this, the intricacies of diet (in particular the consumption of starch, fibre and fat) has come under scrutiny. Equine feed manufacturers have looked for additional sources of starch, a carbohydrate and a natural component of grass that is ‘essential to provide energy, fibre and a sense of fullness’ (Seitz 2022). Today, most horses and rapidly growing foals are commonly fed diets with >50% of total ration by weight in the form of grain ‘concentrates’ and carbohydrates from oats, maize, soya, barley and wheat. These grain based feeds contain high concentrations of soluble, easily fermentable starches but can be deficient in certain minerals and vitamins so getting an optimally balanced feed ‘right’ is difficult.

Too much of a good thing

With advances in scientific knowledge, we now know that when a horse is exposed to surplus starch, the hydrogen ion concentration of their gut increases promoting the production and absorption of lactic acid, acetate and propionate through the activity of fermentation (Ralston 1994). The process is quick, with lactic acid entering the bloodstream within 3 hours of feeding and calcium subsequently being excreted in the urine. In order to combat this nutrient loss, the horses’ hormone system triggers the release of parathyroid hormone into the bloodstream, activating the release of stored calcium (to maintain optimal blood levels) but unfortunately causing bone demineralisation. Clinically, the horse experiences health consequences of varying degrees including digestive diseases (eg: gastric ulcers, diarrhoea, colic or colitis), muscle dysfunction (eg: rhabdomyolysis (known as ‘tying up’), defective bone mineralization (expressed as increased incidence of stress fractures and developmental orthopaedic diseases), systemic diseases (such as laminitis, equine metabolic syndrome and obesity (Chaucheyras-Durand et al 2022) as well as potential causes of fatigue.

The ideal equine diet

There is little equine focused research available on the benefits of individual nutrients (due to limited numbers in trials and their subsequent evaluation) of grain ‘concentrates’. But we do know that ingredient availability and quality is regularly influenced by market pressures.

The table (fig 1) below outlines the sugar, starch and fibre components of the various ingredients commonly found in horse feeds. The optimal grain for equine nutrition with its efficient energy source through lower starch content (relative to other grains) and its high level of soluble fibre (relative to other grains) are oats.

Oats are highly digestible and do not require heat treatment or processing prior to feeding (unlike all other grains). They are the only grain that is easily digested raw and the least likely to cause insulin spikes and blood sugar fluctuations. Unfortunately, oats are not a ‘complete’ nutrient source as they are high in phosphorous and low in calcium. For adequate bone and muscle development as well as proper blood formation, oats must be balanced with additional vitamins and minerals.

The healing power of omegas and short chain fatty acids

While grass provides optimal equine nutrition in its own right, the ‘curing process’ when making hay depletes the valuable omegas 3 and 6 intrinsic in grass. These ‘healing’ nutrients naturally protect the lining of the gastro-intestinal tract by increasing mucous production and alleviating ‘auto digestion’ (via hydrochloric acid). For horses, bacterial fermentation in the hind gut also results in the production of Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs), namely acetic, proprionic and butyric acids. These SCFAs ‘cross talk’ with the gut immune system providing local immunity in the gut as well as protection of the respiratory system, the brain and other tissues against disease. In human medicine, it has been repeatedly established that a dysfunctional gut microbiome is associated with respiratory problems. This is evidenced by the fact that when gut disorders such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBD) or Coeliac disease exist in humans, they are commonly associated with a higher incidence of respiratory infections and related asthmatic like conditions. Barragry (2024) explores the relationship (Fig 2) between gut microbiome and the immune system's ability to support health and combat disease in cattle. A scenario mirrored in the equine.

The stabled horse should be provided with SCFAs daily to support proper functioning gut microbiome. This critical dietary consideration should ideally be provided in the form of flaxseed which has the highest ratio of omegas 3 and 6 (in the ideal ratio 4:1) in the plant world and is most suitable for the equine herbivore.

The health benefits of flaxseed for both humans and equines has been recognised as early as 3,000 BC. Flaxseed was used for various medicinal purposes such as the treatment of gastric disorders, as a soothing balm for inflammation and as a laxative (Judd, 1995). Horsemen (who relied heavily on their equines) and trainers (who sought optimal performance from their charges through natural means) also used flaxseed as a way to supplement the diet with omega-3’s and fibre to produce high quality proteins. Now, thirteen centuries later, we have research to substantiate the knowledge of our ancestors. The renowned German researcher of ‘fats’ and pioneer in human nutrition, Dr. Joanna Budwig, as early as the 1950’s reported that “the absence of highly unsaturated fatty acids causes many vital functions to weaken". Dr. Budwig’s life’s work focused on the dietary ‘imbalance’ between omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in humans has been a cornerstone to the exploration of the role of inflammation and the development of many diseases of the coronary, respiratory, metabolic and immune system.

The small seed of the flax plant is also an excellent source of high-quality protein (exceeding that of soybeans and fish oils) and potassium (a mineral that’s important for cell and muscle function). But, the true power of flaxseed lies in three key components:

Omega-3 essential fatty acids – Also known as "good" fats, omegas enhance the oxygen usage of cells and in combination with alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) are anti-inflammatory in their effect within the body.

Lignans – Flaxseed contains 750 - 800 times more lignans than other plant foods (McCann 2007, Yan 2014). Lignans are a group of compounds with antioxidant properties which also contain plant oestrogen. Lignans are linked to a reduced risk of developing osteoporosis, heart disease and cancer.

Fibre - Flaxseed contains both the soluble and insoluble types of fibre essential for maintaining ‘gut’ health.

In equines, adding flaxseed to the diet has the immediate benefits of a shiny, healthy coat and fewer skin allergies. Consistent use of flaxseed has multiple long term benefits including strong hoof quality, improved joint health, reduced muscle soreness, faster healing of ulcers (Sonali et al 2008) and significantly impacts inflammation associated with chronic skin conditions (commonly known as ‘sweet itch’). In breeding stock, increased Omega-3 levels in mares’ milk leads to boosted immunity in foals with higher stallion fertility and improved conception rates in broodmares documented (Holmes, 2015).

How diet can influence performance

It is easy to think that ‘providing more is better’ when it comes to using nutrition to support performance. But having excess levels of essential vitamins and minerals being processed by the horses’ sensitive gut has a direct impact on their behaviour and willingness to perform. Today, we have greater ‘choice’ at the feed store with a broad range of commercial feeding offerings available including mixes, mashes and supplements but the discerning horse owner can be forgiven for being overwhelmed by the range of diet options for every ailment and stage of life.

In modern times, despite advances in nutrition offerings, we have seen a falloff in performance (Fig 3). During the late 1960s, the U.S. Jockey Club stats noted that racehorses averaged 12 starts per year – a far cry from today's horses racing in the U.S. where the average of 3 ‘starts’ was highlighted by leading US Trainers in 2020 (www.ownerview.com). Unfortunately, this is not just a U.S. based problem, but a phenomenon noted worldwide.

The first equine pelleted feed was formulated in the US by the Cistercian monks in Gethsemani, Kentucky in 1957. Prior to this, all horses were fed ‘straights’ (primarily oats as their energy source and flaxseed as their protein source). My own understanding of the link between modern feeding practices and compromised performance since the 1960s has been curated off an understanding of “what was different” then, as well as a career of observations, clinical practice and scientific review. Fact is, the equine diet of the 1960s was lower in starch and high in fibre. It consisted of oats, minerals, and flaxseed as the “norm”. Hay was the preferred forage (Fig 4).

Today, soya (with one fifth of the omega 3 content of flaxseed) has practically replaced flaxseed as the protein source in equine nutrition. This small change has seen a significant drop in omega-3 and 6 (needed for prostaglandins) in the diet with consequential gastro-intestinal and joint issues. Other dietary changes include those recommended by the National Research Council (NRC) in 1978, who suggested doubling the recommended calcium levels for horses with a subsequent increase in levels of Osteochondrosis (OCD) and Osteopetrosis in the equine population (Krook and Maylin, 1989). Additional moisture in the diet too has led to excess mould formation in convenience feeds and with severe exposure causes liver damage (Buckley et al 2007). Stabled racehorses today mostly lack the nutritional protection afforded a previous generation of horses. The impact has been noted clinically in the widespread increase in equine gastric issues and as stated by J.E. Anthony “Racing fans are missing about half of what they once enjoyed in racing.”

The role of the gut bacteria in the prevention of disease

The gut microbiome begins populating and diversifying from the moment of birth. Though ‘sterile’ in utero, gut derived DNA immediately drives immune health with exposure to nutrition. Recent research suggests that the gut microbiome can be stimulated by using proven probiotics with a track record in enhancing gut health (Barragry 2024). But it is the protective power of SCFAs to allow ‘cross talk’ between the lungs and the gut microbiome that is critical to supporting horses through their lifespan.

Nutrition using grain ‘concentrates’ is currently at approximately 99% saturation in today’s equine population so a return to feeding ‘straights’ is a swim against the tide of modernity. But, knowing the influence of nutrition on health, performance and longevity it falls on horse owners to be mindful of the consequential impacts such convenience feeds have on the gut microbiome and immune system. Random supplementation and high starch feeds are leading to dietary health issues such as gastric ulcers, hyperinsulinemia and hyperlipaemia (obesity) as well as increased risk of laminitis . So trust your gut and keep it simple – a diet of oats, flaxseed, a multi-vitamin balancer and ad lib hay will not only meet your horses’ energy needs but will keep them happy and healthy too.

REFERENCES

Barragry. TB (2024) WEB https://www.veterinaryirelandjournal.com/focus/254-alternatives-to-antibiotics-probiotics-the-gut-microbiome-and-immunity

Buckley T, Creighton A, Fogarty (2007) U. Analysis of Canadian and Irish forage, oats and commercially available equine concentrate feed for pathogenic fungi and mycotoxins. Ir Vet J. 2007 Apr 1;60(4):231-6. doi: 10.1186/2046-0481-60-4-231. PMID: 21851693; PMCID: PMC3113828.

Budwig, Dr. J (1903-2008) WEB https://www.budwig-stiftung.de/en/dr-johanna-budwig/her-research.html

Chaucheyras-Durand F, Sacy A, Karges K, Apper E (2022). Gastro-Intestinal Microbiota in Equines and Its Role in Health and Disease: The Black Box Opens. Microorganisms. 2022 Dec 19;10(12):2517. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10122517. PMID: 36557769; PMCID: PMC9783266. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9783266/

Holmes, R (2015) Feeding for stallion fertility. WEB

https://www.theirishfield.ie/feeding-for-stallion-fertility-172113/

Judd A (1995) Flax - Some historical considerations. Flaxseed and Human Nutrition, S C Cunnane, L U Thompson. AOCS Press, Champaign, IL 1995; 1–10 [Google Scholar]

Martinac, P (2018) What are the benefits of flaxseed lignans? WEB https://healthyeating.sfgate.com/benefits-flaxseed-lignans-8277.html

National Research Council. 1989. Nutrient Requirements of Horses. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

Ralston, S VMD, PhD, ACVN (1994) The effect of diet on acid-base status and mineral excretion in horses in the Journal of Equine Practice. Vol 16 No. 7. Dept of Animal Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08903

Seitz, A (2022) What to know about starch_Medically reviewed by Seitz, A - MS, RD, LDN, Nutrition — WEB https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-is-starch#benefits

Sonali Joshi, Sagar Mandawgade, Vinam Mehta and Sadhana Sathaye (2008) Antiulcer Effect of Mammalian Lignan Precursors from Flaxseed, Pharmaceutical Biology, 46:5, 329-332, DOI: 10.1080/13880200801887732

Train, Race, Recover and Repeat – How targeted nutrition can support the recovery process to optimise performance

Article by Dr Andy Richardson BVSc CertAVP(ESM) MRCVS

Introduction

Horses evolved as herd-living herbivores with a digestive tract designed to cope with a near continuous dietary input of forage in the form of a wide range of plant species. A large hindgut acts as a fermentation vessel where gut microbiota (predominantly a mix of bacteria, protozoa and fungi) exist in harmony with the horse in order to digest the fibre rich plant material.

Fibre is important to the horse for several reasons. The digestion of fibre releases energy and other key nutrients to the horse. Fibre also acts to provide bulk in the digestive tract, thus helping maintain the passage of faecal material through the system. Fibre also acts like a sponge to absorb water in the gut for release when required.

As horses became domesticated and used for work or sporting purposes, more energy-dense feeds in the form of cereal grains were introduced to their diet, as simple forage did not provide for all the caloric requirements. Cereal grains are rich in starch, which is an energy-dense form of nutrition. However, too much starch can cause problems to a digestive tract that remains designed for a pasture-based diet. The issues that can be caused by the trend away from a solely pasture-based diet can be digestive, behavioural or clinical.

Nonetheless, the combination of forage and cereal-based concentrates remains the mainstay approach for the majority of horses in training today, in order to maximise performance. A great deal of research and expertise are utilised by the major feed companies to ensure that modern racehorse concentrate feeds provide adequate provision of the major nutrients required and minimise unwanted effects of starch in the diet.

This article aims to discuss some scenarios where targeted or supplemented nutrition can act to help overcome some of the nutritional challenges faced by the modern horse in training, as they “Train, Race, Recover and Repeat.”

Equine Gastric Ulceration Syndrome (EGUS)

EGUS occurrence in racehorses is well documented, with prevalence shown to be over 80% in horses in training (Vatistas 1999). With a volume of approximately 2–4 gallons (7.53–15 litres), the stomach in horses is relatively small compared to their overall size due to its functional role in accommodating trickle feeding that occurs during their natural grazing behaviour.

As a horse chews, it produces saliva, which is a natural buffer for stomach acid. When the horse goes for a period of time without chewing, the production of saliva ceases, and stomach acid is not as effectively neutralised. The lower half of the stomach is better protected from acid due to its more resistant glandular surface. The upper, or squamous, region does not have such good protection, however, and this can be a problem during exercise when acid will physically splash upwards, potentially leading to gastric ulceration.

In practice, this can presentrepresent a challenge for horses in training. Typically, they will be fed a concentrate-based feed in the early morning that stimulates a large influx of acid in order to help digest the starch. This may be followed by a period without ad-lib access to hay, thus reducing the amount of saliva subsequently produced to act as a buffer. When the horse is subsequently worked, there is a risk of acid damaging the upper squamous region of the stomach. There is some evidence to suggest that the provision of hay in advance of exercise may act like a sponge for the acid, as well as helping form a fibrous matt to minimise upward splash.

Gastric ulceration can go undetected in horses in training and may not lead to any obvious clinical signs. In other horses, it can lead to colic, poor appetite, dull coat and behavioural changes. In both scenarios, it is likely that the ulceration will have an impact on their performance, with decreased stride length, reduced stamina and inability to relax at speed all being possible consequences (Nieto 2009). Gastric ulceration can therefore have a significant impact on the ability of a horse to perform optimally day in day out in a training environment. This is exacerbated when ulceration leads to a reduction in appetite, with the obvious downside of a reduction in calorie intake leading to condition loss and further drop in performance.

This is an area where targeted nutrition has been clinically proven to play an important role. Ingredients such as pectin, lecithin, magnesium hydroxide, live yeast, calcium carbonate, zinc and liquorice have all been studied as having beneficial effects on gastric ulceration (Berger 2002, Loftin 2012, Sykes 2013). It is likely that a combination of the active ingredients will be most efficacious, with benefits noted when the supplement is added to the feed ration to help neutralise acid and form a gel-like protective coating on the stomach surface.

The daily administration of a targeted gastric supplement can be an important part of daily nutrition of the horse in training, alongside the use of pharmaceuticals such as omeprazole or esomeprazole when required.

Sweat loss

Horses have one of the highest rates of sweat loss of any animal, with sweat being comprised of both water and electrolyte ions such as sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium and calcium. Therefore, it is not surprising that horses in training are at risk of unwanted issues should sweat loss not be replaced.

It is also worth noting that transportation can also lead to excessive sweat loss, with studies showing sweat rates of 5 litres per hour of travel on a warm day (van den berg 1998).

If the electrolytes lost in sweat are not adequately replaced, a drop in performance can result, as well as clinical issues such as thumps, dehydration and colic.

Electrolytes play key roles in the contraction of muscle fibres and transmission of nerve impulses. Horses without adequate electrolyte levels are at risk of early onset fatigue that may result in reduced stamina. It is also worth noting that horses that train on furosemide will have higher levels of key electrolyte losses, so will require targeted support to help maintain performance levels (Pagan 2014).

There is also evidence to suggest that pre-loading of electrolytes may be beneficial (Waller 2022). For horses in daily work, the addition of electrolytes to the evening feed will not only replace losses but also help optimise levels for the following day’s travel or race. The benefit of providing electrolytes with feed is that it will minimise the risk of the electrolyte salts irritating the stomach lining, which can occur if given immediately after exercise on an empty stomach. Feeding electrolytes when the horse is relaxed back in the stable will also allow them to drink freely, with the added benefit that electrolytes will stimulate the thirst reflex when they are relaxed, ensuring they are adequately hydrated for the following day.

Products should be chosen on the basis of adequate key electrolyte provision as not all products will provide meaningful levels of all the key electrolyte ions.

Muscle soreness

The process of muscle breakdown and repair is a normal adaptive response to training. This process can lead to inflammation and soreness or stiffness after exercise. In humans, there is a well-recognised condition called Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS).

Further research is required to fully understand the impact of DOMS in horses. DOMS is the muscular pain that develops 24–72 hours after a period of intense exercise. There is no pain felt by the muscles at the time of exercise, in contrast to a ‘torn muscle’ or ‘tying-up’ for example.

In humans, DOMS is thought to be the result of tiny microscopic fractures in muscle cells. This happens when doing an activity that the muscles are not used to doing or have done it in a more strenuous way than they are used to.

The muscles quickly adapt to being able to handle new activities, thus avoiding further damage in the future; this is known as the “repeated-bout effect”. When this happens, the micro-fractures will not typically develop unless the activity has changed in some substantial way. As a general rule, as long as the change to the exercise is under what is normally done, DOMS are not experienced as a result of the activity.

In practice, avoiding any post-exercise muscle soreness in a training programme may be unavoidable, as exercise intensity and duration increases. Horses are far from being machines, so there is a fine balance between a programme that gets a horse fit for purpose without some post-exercise muscle discomfort. Physiotherapy, swimming and turnout will all likely benefit horses experiencing muscle discomfort. Whilst non-steroidal anti-inflammatories will always have their place for horses in training, one area of advancement is the use of plant-based phytochemicals to support the anti-inflammatory response (Pekacar 2021). These may have the benefit of not leading to unwanted gastrointestinal side effects and not having prolonged withdrawal times, although this should always be checked with any supplement particularly with the recent update regarding MSM on the BHA prohibited substance list.

Exercise will also lead to a process of muscle cell damage caused by oxidative stress. This is an inflammatory process and recovery from oxidative stress is key to allow for muscle cell repair and growth. Antioxidants are compounds that help recovery and repair of muscle cells following periods of intense exercise. The process of oxidative stress in muscle cells can lead to muscle fatigue and inflammation if left unsupported. Antioxidant supplementation in the form of Vitamin E or plant-based compounds can help protect against excessive oxidative stress and support muscle repair after exercise (Siciliano 1997).

Conclusion

Nutritional management of horses in training is a complex topic, not least as every horse is an individual and so often needs feeding accordingly. Whilst there is a lot of science available on the subject, the ‘art of feeding’ a racehorse—something that trainers and their staff often have in-depth knowledge of— remains an incredibly important aspect. Targeted nutritional supplements undoubtedly have their place, as discussed in, but not limited to, the scenarios above.

Veterinarians, physiotherapists, other paraprofessionals and nutritionists all play a role in minimising health issues and maximising performance. In the quest for optimal performance on the track, nutritional support is one of the cornerstones of the ‘marginal gains’ theory that has long been adopted in elite human athletes. There is no doubt that racehorses themselves are supreme athletes that live by the mantra of Train, Race, Recover, and Repeat.

References

Berger, S. et al (2002). The effect of acid protection in therapy of peptic ulcer in trotting horses in active training. Pferdeheilkunde 27 (1), 26-30,

Loftin, P. et al (2012). Evaluating replacement of supplemental inorganic minerals with Zinpro Performance Minerals on prevention of gastric ulcers in horses. J.Vet. Int. Med. 26, 737-738

McCutcheon, L.J. and geor R.J. (1996). Sweat fluid and ion losses in horses during training and competition in cool vs. hot ambient conditions: implications for ion supplementation. Equine Veterinary Journal 28, Issue S22.

Nieto, J.E. et al (2009). Effect of gastric ulceration on physiologic responses to exercise in horses. Am. J. Vet. Res.70, 787-795.

Pagan, J.D. et al (2014). Furosemide administration affects mineral excretion in exercised Thoroughbreds. In: Proc. International Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology S46:4.

Pekacar, S. et al (2021). Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects of Rosehip in Inflammatory Musculoskeletal Disorders and Its Active Molecules. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 14(5), 731-745.

Rivero, J.-L.L. et al (2007). ‘Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses’. Journal of Applied Physiology 102(5), 1871–1882.

Siciliano, P.D. et al (1997). Effect of dietary vitamin E supplementation on the integrity of skeletal muscle in exercised horses. J Anim Sci.75(6), 1553-60.

Sykes, B. et al (2013). Efficacy of a combination of a unique, pectin-lecithin complex, live yeast, and magnesium hydroxide in the prevention of EGUS and faecal acidosis in thoroughbred racehorses: A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Equine Veterinary Journal, 45, 16.

van den Berg, J. et al (1998). Water and electrolyte intake and output in conditioned Thoroughbred horses transported by road. Equine Vet J. 30(4), 316-23.

Vatistas, N.J. et al (1999) Cross-sectional study of gastric ulcers of the squamous mucosa in thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet J Suppl. 29, 34–39.

Waller, A.P., and M.I. Lindinger. (2022). Tracing acid-base variables in exercising horses: Effects of pre-loading oral electrolytes. Animals (Basel) 13(1), 73.