Equine Neck CT: Advancing diagnostic precision in racehorses

Article by Rachel Tucker MRCVS

Introduction

When considering neck disorders in the racehorse, we most commonly think of severe conditions such as acute neck trauma and cervical vertebral myelopathy (Wobbler Syndrome). These represent the most severe end of the scale of orthopaedic and neurologic injury to the neck; and a diagnosis, or at least prognosis, is usually clear. However, neck conditions encompass a far wider range of clinical presentations.

Horse positioned in ct scanner

At the milder end of the scale, signs may be subtle and easily missed, whilst still being responsible for discomfort and reduced performance. The recent ability to perform a computed tomography (CT) scan of a horse’s neck represents a major advancement in our ability to diagnose neck conditions. Timely and accurate diagnosis allows efficient and targeted treatment, the ability to plan schedules and improvement in welfare through the provision of appropriate treatment and earlier return to function.

In neurologic cases, an accurate diagnosis facilitates risk management for both the horse, their handlers and riders, while improving safety for all. As conditions and injuries of the neck are being better characterised using CT, new medical and surgical treatment options are being developed, giving the potential for improved outcomes and fewer losses from the racing industry.

This article summarises how CT is being increasingly used by vets to diagnose conditions of the neck and how it is revealing previously unknown information and providing exciting new treatment opportunities.

Presentation

Conditions of the neck can cause a range of signs in the horse, which are wide-ranging in their presentation and variable in their severity. The manner in which these conditions present depends on which anatomical structures are affected. Issues affecting the bones, joints and/or soft tissues of the neck can all cause neck pain, which can manifest in a number of ways. Cases of neck pain can be severe, resulting in a horse with a rigid, fixed neck carriage, an unwillingness to walk and struggling to eat, perhaps due to a traumatic event. Neck fractures are thankfully uncommon but can be catastrophic.

More moderate signs might be displayed as a stiff neck, with reduced range of movement and resentment of ridden work. There may be pain on palpation of the neck and changes in the neck musculature. Increasingly, we are seeing horses with far more subtle signs, which are ultimately revealed to be due to neck pain and neck pathology. Typically, these horses might have an acceptable range of motion of their neck under most circumstances, but they suffer pain or restriction in certain scenarios, resulting in poor performance. This may be seen as tension through the neck, resisting rein contact, a reluctance to extend the neck over fences, or they may struggle on landing.

Riders might report a feeling of restriction or asymmetry in the mobility of the neck. In addition, these horses may be prone to forelimb tripping or show subtle forelimb lameness.

Any condition, which causes injury or disease to the spinal cord or nerves within the neck, also causes a specific range of neurologic signs. Compression of the spinal cord is most commonly caused by malformations or fractures of the cervical vertebrae, or enlargement of the adjacent articular process (facet) joints. This results in classic ‘Wobbler’ symptoms, which can range from subtle weakness and gait abnormalities, through to horses that are profoundly weak, ataxic and uncoordinated. This makes them prone to tripping, falling, or they may even become recumbent.

Peripheral nerve deficits are uncommon but become most relevant if they affect the nerves supplying the forelimbs, which can result in tripping, forelimb lameness, or local sensory deficits. This lameness might be evident only in certain circumstances, such as when ridden in a rein contact. This lameness is difficult to pinpoint as there will be no abnormality to find in the lame limb, indeed a negative response to nerve and joint blocks (diagnostic analgesia) will usually be part of the diagnostic process.

Horses can present with varying combinations and severities of neck pain, neurologic signs and peripheral nerve deficits, creating a wide range of manifestations of neck related disease.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of neck pain is based on careful static and dynamic clinical examination and may be supported by seeing a positive response to treatment. Neurologic deficits are noted during a specific neurologic assessment, which includes a series of provocation tests such as asking a horse to walk over obstacles, back up, turn circles and walk up and down a hill. Confirming neck pathology as the cause of signs can be difficult. Until recently, radiography has been the mainstay imaging modality. Radiographs are useful for assessment of the cervical vertebrae and continue to play an important role in diagnosis; however the complex 3-dimensional shape of these bones, the large size of the neck and an inability to take orthogonal (right-angled) x-ray views means that this 2-dimensional imaging modality has significant limitations. High quality, well-positioned images are essential to maximise the diagnostic potential of radiographs.

A turning point in our diagnostic ability and understanding of neck dysfunction has been the recent adaptation of human CT scanners to allow imaging of the horse’s neck. A number of equine hospitals across the United Kingdom and Northern Europe now offer this imaging modality. We have been providing this service at Liphook Equine Hospital since 2017, with over 150 neck scans performed to date.

The CT procedure

A computed tomography (CT) scan combines a series of x-ray images taken from different angles around the area of interest to create a 3-dimensional volume of imaging data. This data is presented as a grayscale image which can be viewed in any plane and orientation. It provides excellent bone detail, and post processing techniques can provide information on soft tissue structures too. Additional techniques can be employed such as positive contrast myelography to provide greater detail about soft tissue structures. Myelography delineates the spinal cord using contrast medium injected into the subarachnoid space and is indicated in any case showing neurologic signs suggestive of spinal cord compression.

Neck CT is performed under a short general anaesthetic. Scans without myelography typically take less than 20 minutes to complete. The entire neck is imaged, from the poll to the first thoracic vertebra. The procedure is non-invasive and low risk, with anaesthetic-related complication presenting the main risk factor to the procedure. We have not encountered any significant complications in our plain CT scan caseload to date. Horses showing ataxia, weakness and incoordination (Wobbler’s), undergo CT myelography which adds around 20 minutes to the procedure. These horses are exposed to a greater level of risk due to their neurologic condition, the injection of a contrast agent and the increased chance of destabilising a more severe lesion during the procedure.

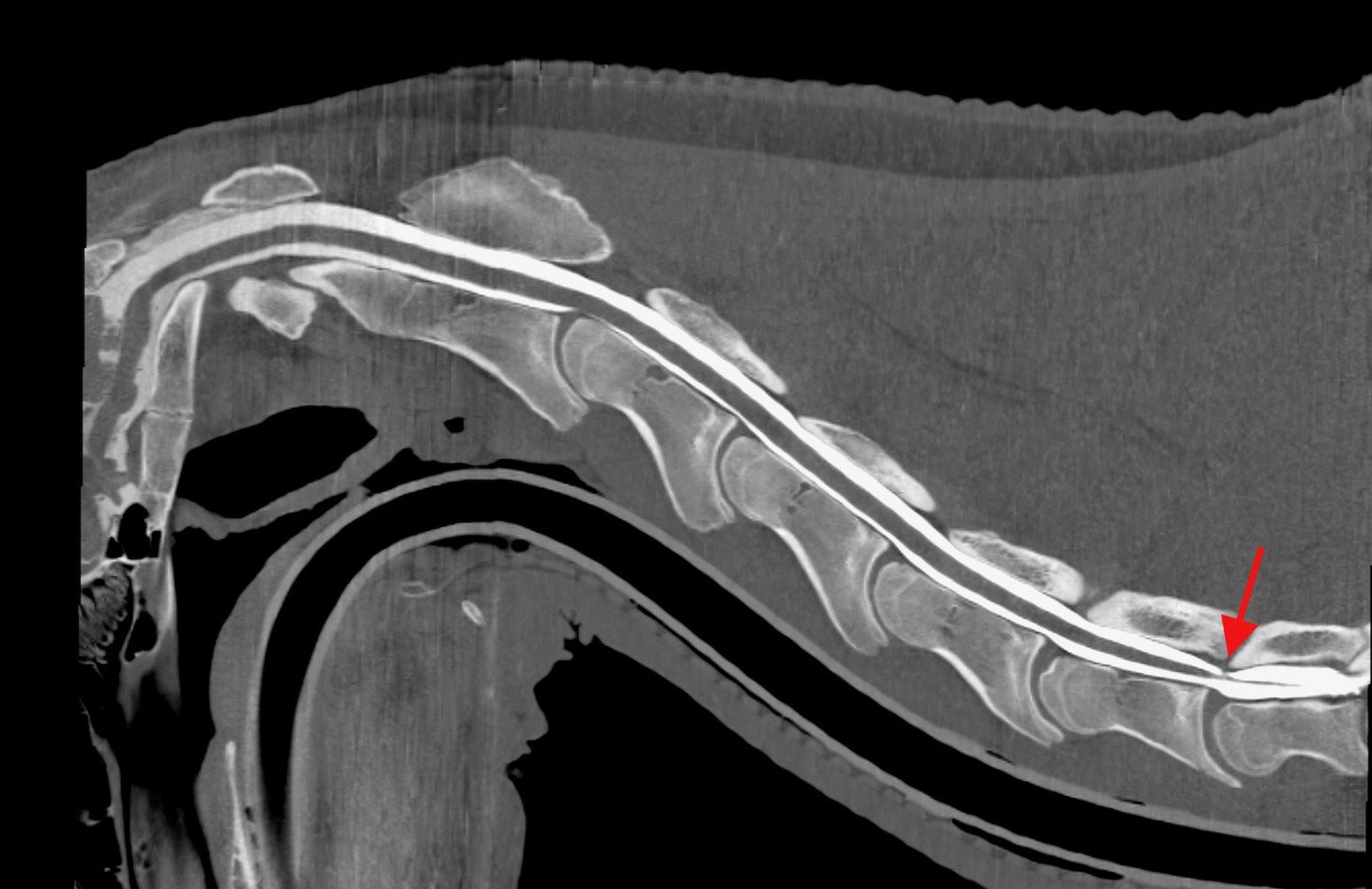

Sagittal and transverse CT myelogram images of a young racing thoroughbred showing neurologic (Wobbler) signs. shows narrowing of the spinal canal at the base of the neck (arrow)

CT is revealing more detailed information about ways that spinal cord compression can occur in Wobbler cases, about compression of spinal nerves resulting in forelimb gait deficits and precise detail about fracture configurations. It gives us detailed images of articular process joint disease, intervertebral disc disease, developmental conditions and anatomic variations. It is also revealing information about rare diseases such as vertebral abscesses or spinal neoplasia. As our caseload and confidence in the imaging modality grows, we are learning more about the value of CT in examining more subtle neck conditions. We are also bringing the benefit of a more accurate diagnosis, allowing precise targeted treatment and a better ability to provide a prognosis about outcomes—likely progression or safety factors. CT myelography allows circumferential imaging of the spinal canal and yields significantly more information than traditional x-ray myelography. As a result, we hope to enable better case selection of horses that may benefit from Wobbler surgery, with the goal of resulting in improved success rates of the surgery.

Innovations in treatment

image shows a fracture of the articular process of the 3rd cervical vertebrae in the mid neck, which was not visible on x-ray.

New treatment options are emerging as a result of our more accurate diagnoses of neck pathology. Of the first 55 horses which underwent neck CT at our hospital, we were surprised to discover that 13 (24%) had some form of osteochondral fragmentation within the articular process joints of their neck. Some of these horses were young Thoroughbreds, bred to race but showing Wobbler signs. These tended to have convincing CT evidence of type 1 CVM (Wobbler Syndrome) and osteochondrosis affecting their neck. Others had fragments which were larger and more discrete, with evidence of articular process joint enlargement/arthritis but no other bony lesions. These horses were typically older and of a range of breeds and uses.

In those horses presenting with signs of neck pain but no neurologic deficits, surgical removal of these fragments was proposed. Following further consideration and cadaver training, we have begun to offer this surgery for horses that fit the appropriate criteria and have surgically accessible fragments. We have performed arthroscopic or arthroscopic-assisted fragment removal from eight articular process joints in six horses to date. No intraoperative or postoperative complications have been encountered; and five of six horses showed complete resolution of neck pain. In the sixth horse, full recovery was not anticipated due to the presence of additional neck pathology, but partial improvement occurred for two years. Fragment removal has relieved signs of neck pain and stiffness and caused improved performance in these horses.

Two procedures that are emerging to treat spinal nerve root impingement are a targeted peripheral nerve root injection and a keyhole surgical procedure to widen the intervertebral foramen. Nerve root injection is performed in the standing sedated horse under ultrasound guidance. Surgery is performed under anaesthesia, using specialised minimally invasive equipment to widen the bony foramen using a burr. This surgery is in its infancy but offers an exciting treatment option.

Additionally, CT gives us the ability to better plan for fracture repair, undoubtedly improving our case selection for Wobbler surgery; it more accurately guides intra-articular injection of the articular process joints.

Summary

Computed tomography is transforming our ability to diagnose conditions of the horse’s neck. The procedure is low risk and now widely available in the UK and other parts of Europe. It is driving the innovation of novel treatment options with the goal of improving outcomes and reducing losses to conditions of the neck. Our CT findings are posing new questions about neck function, pain and neurologic disease and is an active area of ongoing research.

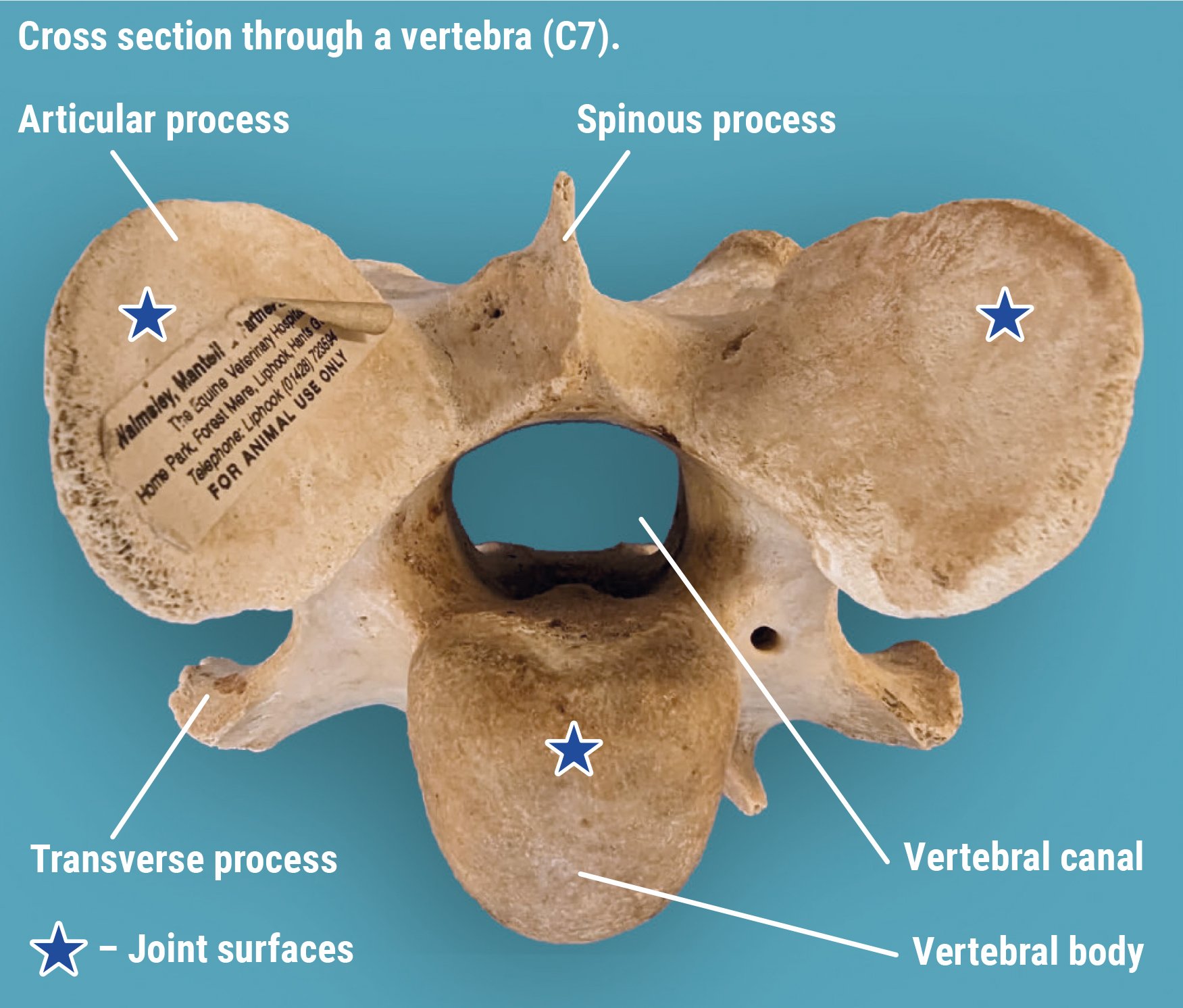

Anatomy of the cervical vertebrae

The neck vertebrae of the horse

The neck consists of seven cervical vertebrae which form a gentle S-shaped curve to link the skull at the poll to the thoracic vertebrae of the chest. Its primary functions are to protect the spinal cord, support the heavy weight of the head and to allow a large range of movement so that a horse can monitor his environment and run at speed, both being vital to this prey species.

The first (atlas) and second (axis) cervical vertebrae are highly adapted to allow head mobility. The third to sixth vertebrae are very similar in shape, whereas the seventh is shortened as it starts to show similar features to the vertebrae of the thorax. The typical cervical vertebra consists of a cylindrical column of bone (vertebral body) articulating with adjacent vertebrae via an intervertebral disc.

Running along the upper surface of this bony column is a bony canal created by the vertebral arch. This canal protects the spinal cord and associated structures that run through the centre. Above and to the side of the spinal canal sit the paired articular processes and below; and to the side sit the transverse processes. These are bony prominences to which muscles attach. The soft tissues of the neck are complex and intrinsically linked to the forelimbs and entire axial skeleton.

The articular processes also form the articular process joints (facet joints) which create an additional two joints between each vertebra. Although highly adapted, these joints are similar to others in the body consisting of cartilage-lined surfaces, a joint capsule and joint fluid. The joint surfaces are oval in shape, approximately 3-4cm in diameter and sit at an oblique angle to the neck. They provide important additional support and mobility to the neck.

References:

Schulze N., Ehrle, A., Beckmann, I and Lischer, C. (2021) Arthroscopic removal of osteochondral fragments of the cervical articular process joints in three horses. Vet Surg. ;1-9.

Swagemakers J-H, Van Daele P, Mageed M. Percutaneous full endoscopic foraminotomy for treatment of cervical spinal nerve compression in horses using a uniportal approach: Feasibility study. Equine Vet J. 2023.

Tucker R, Parker RA, Meredith LE, Hughes TK, Foote AK. Surgical removal of intra-articular loose bodies from the cervical articular process joints in 5 horses. Veterinary Surgery. 2021;1-9.

Wood AD, Sinovich M, Prutton JSW, Parker RA. Ultrasonographic guidance for perineural injections of the cervical spinal nerves in horses. Veterinary Surgery. 2021; 50:816–822.

Wobbler Syndrome and the thoroughbred

By Celia M Marr, Rossdales Equine Hospital and Diagnostic Centre

Wobbler Syndrome, or spinal ataxia, affects around 2% of young thoroughbreds. In Europe, the most common cause relates to narrowing of the cervical vertebral canal in combination with malformation of the cervical vertebrae. Narrowing in medical terminology is “stenosis” and “myelopathy” implies pathology of the nervous tissue, hence the other name often used for this condition is cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (CVSM).

Wobbler Syndrome was the topic of this summer’s Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, an event held at Palace House, Newmarket. Gerald Leigh was a very successful owner breeder and these annual lectures, now in their second year, honour of Mr Leigh's passion for the thoroughbred horse and its health and welfare. The lectures are attended by vets, breeders and trainers, and this year because of the importance and impact of Wobbler syndrome on thoroughbred health, several individuals involved in thoroughbred insurance were also able to participate.

Blindfolding the horse, exacerbates the ataxia and improves the accuracy of objective ataxia assessment.

Dr Steve Reed, of Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital, Kentucky and international leader in the field of equine neurology gave an overview of Wobbler Syndrome. Affected horses are ataxic, which means that they have lost the unconscious mechanisms which control their limb position and movement. Young horses with CVSM will generally present for acute onset of ataxia or gait abnormalities, however, mild ataxia and clumsiness may often go unnoticed. Trainers often report affected horses are growing rapidly, well-fed, and large for their age. It is common for riders to describe an ataxic horse as weak or clumsy. Sometimes, a horse which has been training normally will suddenly become profoundly affected, losing coordination and walking as though they were drunk, or in the most severe cases stumbling and falling. Neurological deficits are present in all four limbs, but are usually, but not always more noticeable in the hindlimbs than the forelimbs. In horses with significant degenerative joint disease, lateral compression of the spinal cord may lead to asymmetry of the clinical signs.

When the horse is standing still, it may adopt an abnormal wide-based stance or have abnormal limb placement, and delayed positioning reflexes. At the walk, the CVSM horse’s forelimbs and hindlimbs may not be moving on the same track and there can be exaggerated movement of the hind limbs when the horse is circled. Detailed physical examination may reveal abrasions around the heels and inner aspect of the forelimbs due to interference, and short, squared hooves due to toe-dragging. Many young horses affected with CVSM have concurrent signs of developmental orthopaedic disease such as physitis or physeal enlargement of the long bones, joint effusion secondary to osteochondrosis, and flexural limb deformities.

Radiography is generally the first tool which is used to diagnose CVSM. Lateral radiographs of the cervical vertebrae, obtained in the standing horse, reveal some or all of five characteristic bony malformations of the cervical vertebrae: (1) “flare” of the caudal vertebral epiphysis of the vertebral body, (2) abnormal ossification of the articular processes, (3) malalignment between adjacent vertebrae, (4) extension of the dorsal laminae, and (5) degenerative joint disease of the articular processes. Radiographs are also measured to document the ratio between the spinal canal and the adjacent bones and identify sites where the spinal canal is narrowed.

ABOVE L–R: Lateral radiographs can show the vertebral bones have an abnormal shape with flare of the caudal vertebral epiphysis (curved arrow) and extension of the dorsal laminae (straight arrow). Abnormal ossification of the articular processes and enlargement of the joints due to degenerative joint disease (arrows). Measuring the ratio of the spinal canal to the adjacent bone identifies narrowing of the spinal canal. In this case, the narrowing is dramatic due to mal-alignment of adjacent vertebral bones.

Dr Reed also highlighted myelography as the currently most definitive tool to confirm diagnosis of focal spinal cord compression and to identify the location and number of lesions. The experts presenting at the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures agreed that myelography is essential if surgical treatment is pursued. However, an important difference between the US and Europe was highlighted by Prof Richard Piercy, of the Royal Veterinary College, University of London. In Europe, protozoal infection is very rare, whereas in US, equine protozoal myeloencephalitis can cause similar clinical signs to CVSM. Protozoal myeloencephalitis is diagnosed by laboratory testing of the cerebral spinal fluid but there is also a need to rule out CVSM. Therefore, spinal fluid analysis and myelography tends to be performed more often in the US. Prof Piercy pointed out that in the absence of this condition, vets in Europe are often more confident to reach a definitive diagnosis of CVSM based on clinical signs and standing lateral radiographs.