Amy Murphy – Thinking Outside the Box

Equuis Photography / Jason Bax

Article by Katherine Ford

“I’m a bit choked up; this horse means the absolute world to me…” Amy Murphy was close to tears at Auteuil in March as she welcomed stable stalwart Kalashnikov back into the Winners’ Enclosure with Jack Quinlan aboard. It was a first success in almost four years for the ten-year-old, although the intervening months had seen the popular gelding performing creditably at Graded level in campaigns interrupted by injury. Connections pocketed €26,680 for the winners’ share of the €58,000 conditions hurdle; but the satisfaction far surpassed the prize money.

“An awful lot of blood, sweat and tears have gone into getting him back, but don’t get me wrong: if at any point we thought that he wasn’t still at the top of his game, we’d have stopped because he doesn’t owe us anything.” Runner-up in the Supreme Novices’ Hurdle at the 2018 Festival and a Grade 1 winner at Aintree the following season, Kalashnikov put Amy Murphy—with her refreshing enthusiasm and undeniable horsemanship—on the map from the start of their respective careers.

“He is very much a people’s horse. He was campaigned from the early days at the highest level, and he had some real good battles as a young horse; and I think that those types of horses that don’t go down without a fight, people lock onto them and follow them.”

From veterans to juveniles

Equuis Photography / Jason Bax

While the achievement of keeping a ten-year-old on form and identifying a winnable race at Auteuil for his French debut is considerable, the success was all the more notable as it came just three days after Myconian had earned connections €15,000 for victory in the Prix du Début at Saint-Cloud—the first juvenile contest of the Parisian season. It is rare to find a trainer with success at both ends of the age spectrum, in two different disciplines, but when you add in the fact that Amy Murphy had crossed the Channel to complete this unusual double, it demonstrates a laudable versatility.

“We try and work with everything we get sent. We’re in a fortunate position where we’ve got the best of both worlds with lots of lovely young horses; but Kalashnikov, Mercian Prince and some of the old brigade have been with us since we started. I started training six years ago, and they were two of the first horses in my yard so they’ve been a big part of my career and still are.”

Twelve-year-old Mercian Prince has racked up a total of 13 wins for Amy since arriving in her fledgling yard from France in 2016, with three of these coming in the past 12 months and including one in Clairefontaine last summer. As with Kalashnikov, patience has reaped rewards with this veteran.

“Mercian Prince is very tricky to train at home—he has a mind of his own, and everything’s got to be on his terms. We do lots of different things with him. He will go three or four times during the year to the beach at Holkham, which is about an hour down the road. It keeps him mentally active. I’m a big believer in freshening them up. I like to string a couple of races together and then give them a week or ten days out in the field at the farm—things like that. It’s fine if you’ve got two-year-olds and it’s a short-term game; but with older horses that you know are going to stick around, you’ve got to keep them fresh.”

From pony-mad to the youngest trainer in Newmarket

Ambitious and determined, Amy Murphy spent her childhood on her father’s Wychnor Park Stud in Staffordshire. “My dad bred National Hunt horses as a hobby. I always had ponies and hunted and showjumped until I was about 16; then I started riding out for local trainers and got bitten by the racing bug. I spent all of my weekends and holidays riding out for as many people as would let me in. My dad wouldn’t let me leave school without any qualifications, so I went to Hartpury College and did a diploma in equine science. The day after that finished, I was in a racing yard.”

After a stint with Nicky Henderson, Amy’s now-characteristic adventurous spirit led her to Australia and an educational season with Gai Waterhouse. “Australia was where I learnt more about spelling horses. Their horses will only have three or four runs together and their seasons are split up so they can campaign them with breaks in between the different carnivals. Gai is obviously brilliant with her two-year-olds and does lots of stalls work with them, and that was another important thing I learnt with her.”

On returning to the UK, Amy joined Tom Dascombe as pupil assistant at Michael Owen’s Manor House in Cheshire, which opened the doors to France for the first time, overseeing his satellite base in Deauville during a summer. Her racing education was completed with four years at Luca Cumani’s stable in Newmarket before setting out on her own in 2016, at age 24—the youngest trainer in Newmarket.

“One of the biggest things I learnt from Luca was making sure a horse is ready before you run. As you become a more mature trainer, you relax more into it; you learn that patience pays off. If you think something needs a bit more time or something’s not quite right, then nine times out of ten, you need to be patient.”

Patience is a virtue

Amy with Pride Of America & Lemos with Miss Cantik.

Amy Murphy may have learnt patience with her horses, but she is impatient with a system that she has had to seek and find alternative campaigns for her horses due to low prize money in the UK. “As William Haggas said to me the other day, I’ve got off my rear end and done something about the situation.” She continues, “It’s very hard to make it pay in England, sadly, so it’s either sit here and struggle or do something outside the box.”

Amy’s first Stakes success came in France in just her second season training, thanks to £14,000 breeze-up purchase Happy Odyssey, winner of a juvenile Listed contest at Maisons-Laffitte and who quickly added more profit by selling for €300,000 at Arqana’s Arc Sale just days later. “From very early on, we’ve targeted France. To start with, it was just the black-type horses; but once I got to know the programme a bit better, we started to bring a few of the others across too.”

The ”we” referred to includes Amy’s husband, former Brazilian champion apprentice Lemos de Souza, whom she met when working for Luca Cumani and who now plays a vital role at Amy’s Southgate Stables. “He’s a very good rider and a very good judge of a horse, and is a great asset to have with the two-year-olds. It’s nice having someone to work with and bounce ideas off. He has travelled all over the world—Dubai, Japan, Hong Kong—for Luca Cumani with all of his good horses.”

French flair

Tenrai & Jade Joyce.

Last year, the pair widened their horizons further with the decision to take out a provisional licence in France, renting a yard from trainer Myriam Bollack-Badel in Lamorlaye. “We were going into the complete unknown. My travelling head girl Jade Joyce was based out there along with another girl; and we basically sent out twelve horses on the first day and between them, they had a fantastic three months. The two-year-olds were where our forte lay and what we tried to take advantage of, whereas we had never had horses run in handicaps in France. So, we had to get the older horses handicapped, and the system is completely different.

Amy with racing secretary, Cat Elliott.

There were plenty of administrative errors early on, as my secretary Cat Elliot was doing everything from in Newmarket; so there were plenty of teething problems and plenty of pens being thrown across the office… For example, I didn’t know you couldn’t run a two-year-old twice in five days, so I tried to declare one twice in five days … little things like that. It was all a learning process, like going back to square one again.”

The operation was declared a resounding success, with eight wins and 15 placed runners during the three-month period, amassing a hefty share of the €276,927 earned by the stable during 2022 in France. Among the success stories, juvenile filly Manhattan Jungle was snapped up by Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners after two wins at Chantilly and Lyon Parilly and was later to take Murphy and team to Royal Ascot, the Prix Morny and the Breeders’ Cup. Meanwhile, another juvenile filly, Havana Angel, earned black type in the Gp.3 Prix du Bois, entered Arqana’s Summer Sale as a wild-card and changed hands for €320,000.

The sole regret is that France Galop only allows trainers one chance with the provisional licence. “We tried to apply again this year but sadly got turned down. Moving over full time is not out of the question in the future.”

Vive la Difference

During her stint at Lamorlaye, Amy had the chance to observe some of the French professionals; and although she stresses, “I wasn’t up at Chantilly so didn’t get to see the likes of André Fabre…,” she also notes, “The gallops men would be very surprised by how quick our two-year-olds would be going regularly. The French seem to work at a slower pace, whereas we are more short and sharp; and we use the turf as much as we can. We would work our two-year-olds in a last piece of work with older horses to make sure that they know their job.”

Impressed by the jumps schooling facilities in Lamorlaye, Amy was also complimentary about other aspects of the training centre. “I like the way that you can get the stalls men that work in the afternoon to come and put your two-year-olds through in the morning. That’s all very beneficial to both the horse and to the handlers because they know each other. Another big thing which I love over in France is that when the turf is too quick, they water it so that you can still train on it in the mornings, even at the height of the summer.”

Even without the provisional licence, Amy Murphy’s name is still a familiar sight on French racecards. At the time of writing in late May, her stable has earned €117,446 in prize money and owners’ premiums in 2023, from 18 runners of which four have won and eight placed.

To reduce travel costs, organisation is key. “I had a filly that ran well in a €50,000 maiden at Chantilly recently, and she travelled over with a filly that ran and won at Saint-Cloud three days later. They were based at Chantilly racecourse for the week and moved across to Saint-Cloud on the morning of the race and then came home together on Friday night. It takes a bit more logistics but financially it makes sense to send two together.” As for the owners, they have made no complaints about seeing their horses race further afield. “Plenty of my owners have been over to France; they love it. I haven’t had one person say they don’t want to go to France yet, anyway!”

Defending an industry

Closer to home, a subject dear to Amy’s heart is horse welfare and the image of racing. On her social media accounts, she promotes the cause and has invited the public to visit her stable to see for themselves the care that racehorses are given. “I’ve had a couple of contacts but nowhere near as many as I’d like. As an industry, we have to show that this image that so many people have of racing is just not true. The only way we can do that is by getting people behind the scenes and letting them see just how well these animals are loved and cared for by all of the girls and guys in the yards. Events like the Newmarket Open Day, when we get thousands of people in to visit the years, are the kind of thing that we need to keep pushing. I want to be in this sport for a long time, so I want to do anything I can to help promote it.”

With advocates like Amy and a generation of motivated young trainers, the sport of horse racing can count on some highly professional, hard-working and modern ambassadors, in the UK, France and beyond.

Assessment of historical worldwide fracture & fatality rates and their implications for thoroughbred racing’s social licence

Article by Ian Wright MRCVS

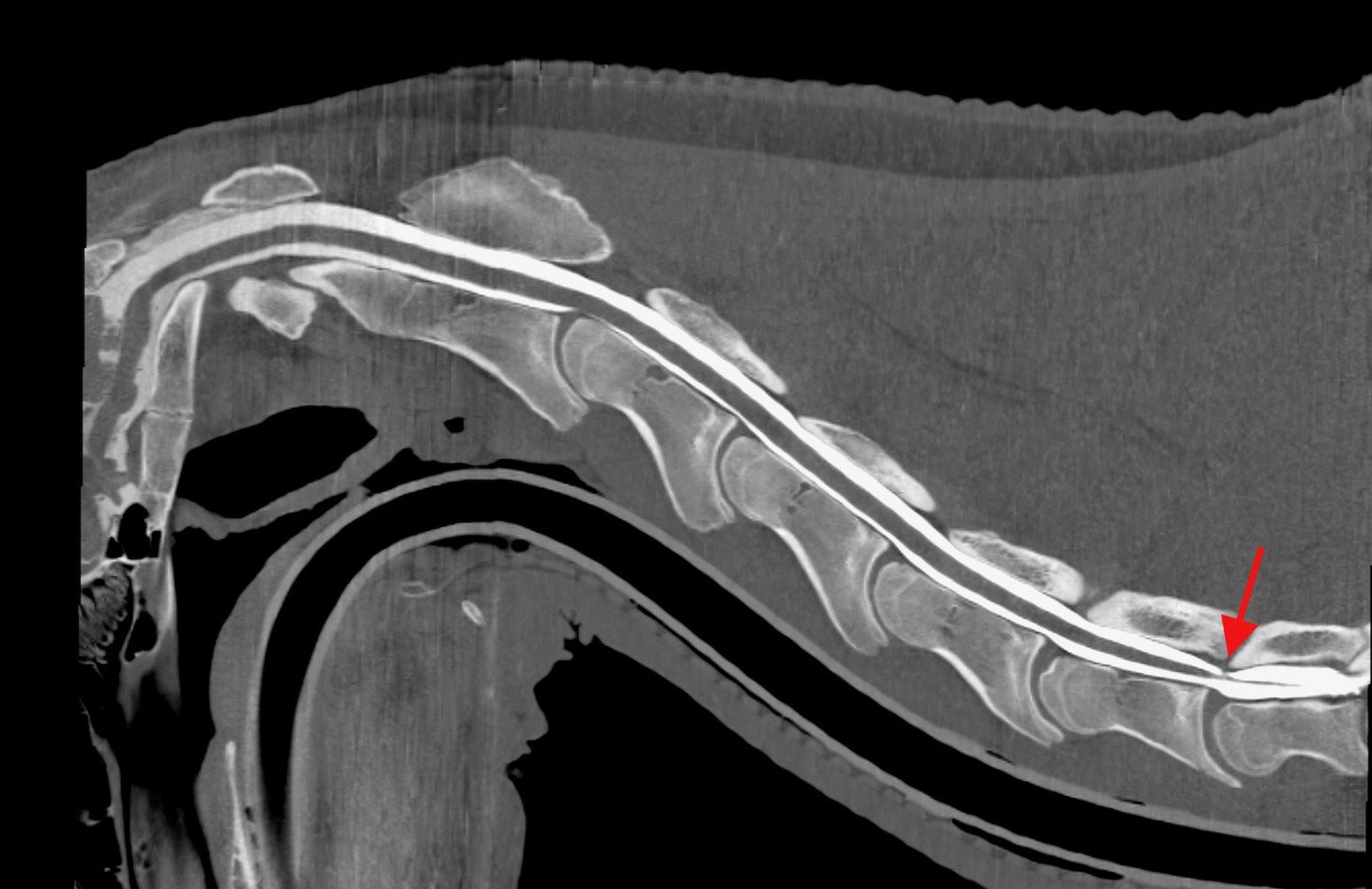

Racing’s social licence is a major source of debate and is under increasing threat. The principal public concern is that racing exposes horses to significant risk of injury including catastrophic (life-ending) injuries of which fractures are the commonest cause. The most recent studies in the UK indicate that fractures account for approximately 75% of racecourse fatalities. Recent events highlight the need for urgent stakeholder discussion, which necessarily will be uncomfortable, in order to create cogent justification for the sport and reliant breeding industry.

A necessary prelude to discussion and debate is an objective assessment of risk. All and any steps to reduce risks and mitigate their impact are important and must be embraced by the horseracing industry (and quite possibly all other horse sports). To begin this, a here and now assessment is important: put simply, does the price paid (risk) justify the benefit (human pleasure, culture, financial gain, employment, tax revenue, etc). Objective data provides perspective for all interested parties and the voting public via their elected representatives, who ultimately provide social licence, with other welfare issues—both human and animal—on which society must pass judgement.

The data in Tables 1 to 12 report a country by country survey of fracture and fatality rates reported in scientific journals and documented as injuries/fatalities per starters. It may be argued that little of the data is contemporary; the studies range from the years 1980 to 2013. However, the tabulated data provided below is the most up to date that can be sourced from independently published, scrutinised scientific papers with clear—albeit sometimes differing—metric definitions and assessable risk rates.

In assimilating and understanding the information, and in order to make comparisons, some explanatory points are important. The first, and probably the most important, is identification of the metric. Although at first glance, descriptor differences may appear nuanced, what is being recorded massively influences the data.

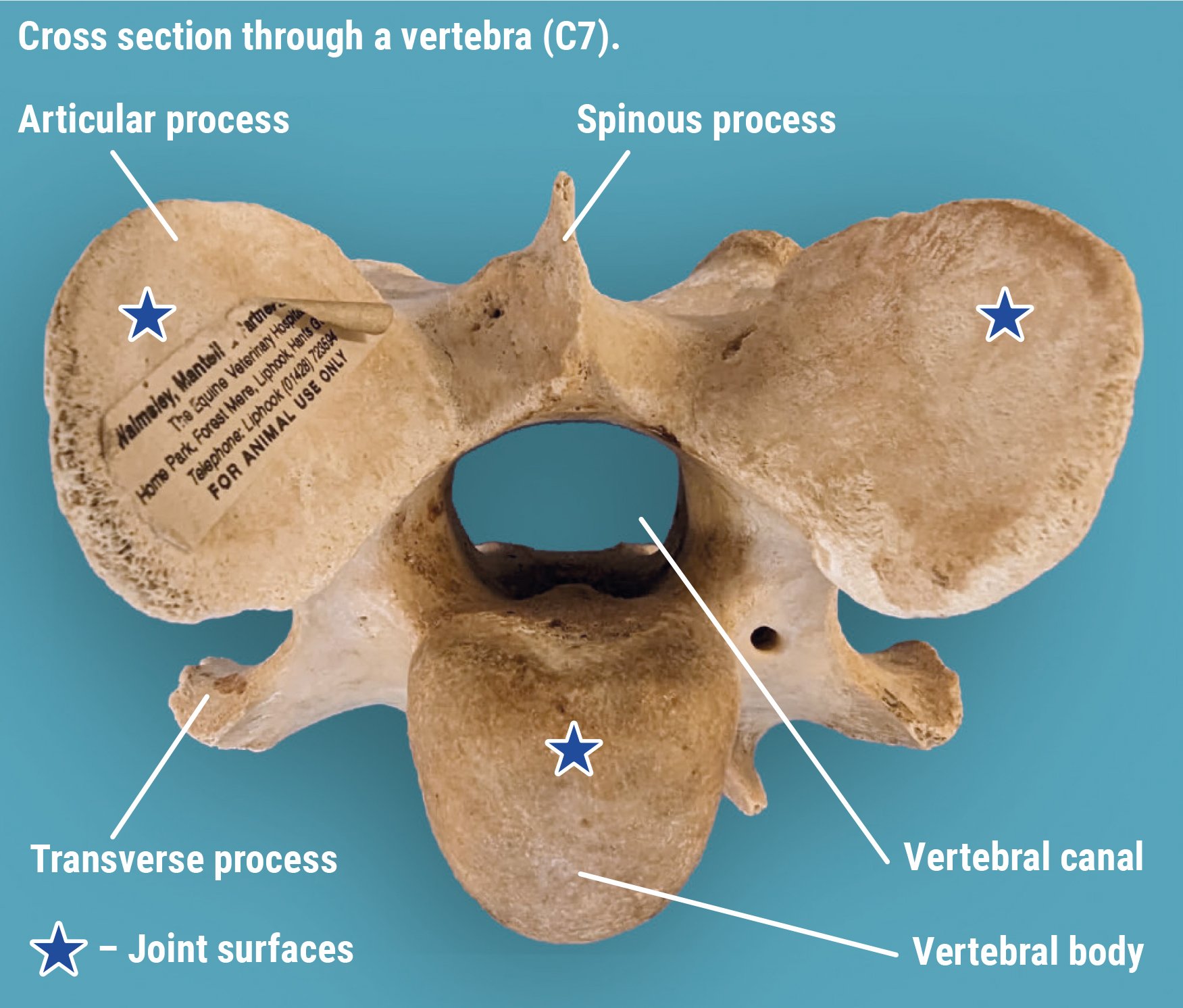

These include fatality, catastrophic injury, fracture, orthopaedic injury, catastrophic distal limb fracture, fatal musculoskeletal injury, serious musculoskeletal injury, and catastrophic fracture. The influence of the metric in Japanese racing represents the most extreme example of this: ‘fracture’ in the reporting papers included everything from major injuries to fragments (chips) identified after racing in fetlocks and knees, i.e. injuries from which recovery to racing soundness is now an expectation. At the opposite pole, studies in other countries document ‘catastrophic’, i.e. life-ending fractures which have a substantially lower incidence. The spectrum of metric definitions will all produce different injury numbers and must be taken into account when analysing and using the data.

Studies also differ in the methods of data collection that will skew numbers in an undetermined manner. Some only record information available at the racecourse, others by identifying horses that fail to race again within varying time periods, horses requiring hospitalisation following racing, etc. The diagnostic criteria for inclusion of horses also vary between reports: some document officially reported incidents only, some are based only on clinical observations of racecourse veterinary surgeons, while others require radiographic corroboration of injuries.

From a UK perspective, the data is quite robust in concluding that risks differ significantly between race types. The majority of fractures that occur in flat racing, and between obstacles in jump racing, are the result of stress or fatigue failure of bone. They are not associated with traumatic events, occur during high speed exercise, are site specific and have repeatable configurations. In large part these result from a horse’s unique athleticism: in the domesticated species, the thoroughbred racehorse represents the pinnacle of flight-based evolution. Fractures that result from falls in jump racing are monotonic—unpredictable, single-event injuries in which large forces are applied to bone(s) in an abnormal direction.

This categorisation is complicated slightly as fatigue failure at one site, which may be bone or supportive soft tissue, can result in abnormal loads and therefore monotonic fracture at another. The increased fracture rate in jump racing is explained in part by cumulative risk. However, it is complicated by euthanasia of horses with injuries with greater post injury commercial value and/or breeding potential that might be treated. Catastrophic injuries and fatality rates in NH flat races are most logically explained by a combination of the economic skew seen in jump racing and compromise of musculoskeletal adaptation.

Racing surface influences both injury frequency and type. Studies in the UK have consistently documented an increased fatality rate and incidence of lower limb injury on synthetic (all weather) surfaces compared to turf. Although risk differences are clear, confounding issues, such as horse quality and trainer demographic, mean that the surface per se may not be the explanation. In the United States, studies reporting data from the same geographic location have produced mixed results. In New York, these documented greater risks on dirt than turf surfaces; while a California study found no difference, and a study in Florida found a higher risk on turf. A more recent study gathering data from the whole of the U.S. reported an increased risk on dirt surfaces. Variations in the nature of injury between surfaces may go some way toward explaining fatality differences.

Much has been done to reduce recognisable risk factors particularly in jump racing; but in the UK, it is likely (for obvious data supported reasons) that it will come under the greatest scrutiny. The incidence of fractures and fatalities in flat racing are low, and the number of currently identified risk factors are high. Over 300 potential influences have been investigated, and over 50 individual factors demonstrated statistically are associated with increased risk of catastrophic injury.

The majority of fractures occurring in flat racing (and non-fall related fractures in jump racing) are now also treatable, enabling horses to return to racing and/or to have other comfortable post-racing lives.

The common public presumption that fractures in horses are inevitably life-ending injuries is a misconception that could readily be remedied. An indeterminate number of horses are euthanised on the basis of economic viability and/or ability to care for horses retired from racing. On this point, persistence with a paternalistic approach is a dangerous tactic in an educated society. Statements that euthanasia is ‘the kindest’ or ‘best’ thing to do, that it is an ‘unavoidable’ consequence of fracture or that only ‘horsemen understand or know what is best’ can be seen as patronising and will not stand public scrutiny.

At some point, data to distinguish between horses euthanised as a result of genuinely irreparable injuries and those with fractures amenable to repair will become available. Before this point is reached, the consequences require discussion and debate within the racing industry.

Decisions on acceptable policies will have to be made and responsibility taken. In its simplest form, this is a binary decision. Either economic euthanasia of horses, as with agricultural animals, is considered and justified as an acceptable principle by the industry or a mechanism for financing treatment and lifetime care of injured horses who are unlikely to return to economic productivity will have to be identified. The general public understands career-ending injuries in human athletes: These appear, albeit with ongoing development of sophisticated treatments at reducing frequency, in mainstream news.

Death as a direct result of any sporting activity is a difficult concept in any situation and draws headlines. Removal of the treatable but economically non-viable group of injuries from data sets would reduce, albeit by a currently indeterminate number, the frequency of race course fatalities. However, saving horses' lives whenever possible will not solve the problem: it will simply open an ethical debate viz is it acceptable to save horses that will be lame? In order to preserve life, permanent lameness is considered acceptable in people and is not generally considered inhumane in pets. Two questions arise immediately: (i) How lame can a horse be in retirement for this to be considered humane? (ii) Who decides? There is unquestionably a spectrum of opinion, all of which is subjective and most of it personal. It will not be an easy debate and is likely to be complicated further by consideration of sentience, which now is enshrined in UK law (Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022); but it requires honest ownership of principles and an agreed policy.

For the avoidance of doubt, while the focus of this article and welfare groups’ concerns are on racecourse injuries, those sustained in training follow a parallel pathway. These currently escape attention simply by being, for the most part, out of sight and/or publicity seeking glare.

Within racing, there is unquestionably a collective desire to minimise injury rates. Progress has been made predominantly by identification of extrinsic (i.e. not related to the individual horse) risk factors followed by logical amendments. In jump racing (monotonic fractures), obstacle modification, re-siting and changing ground topography are obvious examples of risk-reducing measures that have been employed.

In flat racing progress has involved identification risk factors such as race type and scheduling, surface, numbers of runners, track conditions etc which have guided changes. However, despite substantial research and investment, progress in identification of intrinsic (ie relating to the individual horse) risk factors is slow. While scientifically frustrating, a major reason for this is the low incidence of severe fractures: this dictates that the number of horses (race starters) that need to be studied in order to assess the impact of any intervention is (possibly impractically) high. Nonetheless, scientific justification is necessary to exclude a horse from racing and to withstand subsequent scrutiny.

Review of potential screening techniques to identify horses at increased risk of sustaining a fracture while racing is not within the scope of this article, but to date none are yet able, either individually or in combination, to provide a practical solution and/or sufficiently reliable information to make a short-term impact. It is also important to accept that the risk of horses sustaining fractures in racing can never be eliminated. Mitigation of impact is therefore critical.

When fractures occur, it is imperative that horses are evaluated to be given the best possible on course care. This may, albeit uncommonly be euthanasia. Much more commonly, horses can be triaged on the course and appropriate support applied before they are moved to the racecourse clinical facility for considered evaluation and discussion. The provision of fracture support equipment to all British racecourses in 2022 marked a substantial step forward in optimising injured horse care.

Neither racing enthusiasts nor fervent objectors are likely to change their opinions. The preservation of social licence will be determined by the open-minded majority who lie between: it is the proverbial ‘man on the street’ who must be convinced. The task of all who appreciate horse racing's contributions to society and wish to see it continue is to remain focussed on horse welfare, if necessary to adjust historical dogmas, absorb necessary costs and to encourage open, considered, honest (factually correct) risks versus benefits discussion.

Warsaw finally hosts EMHF assembly and stewards' conference

Article by Paull Khan

It’s just possible that the main benefit of the EMHF to its racing administrator members is the social dividend. Many of us have been involved for a dozen years or more, and the bonds that have developed within our network allow easy and unhesitating communication whenever some international issue or other should crop up in our racing lives. This column’s regular reader will know that the EMHF seeks to enrich our members’ education by moving our biannual meetings around the region and combining them with attending the races in the host country. In this issue, following a successful gathering in Poland, we try to convey a little of the flavour of an EMHF General Assembly reunion.

Back in 2019, when we gathered in Oslo and memorably celebrated Norway’s exuberant May 17th National Day celebrations, it was announced that, the following year, we would reconvene in Warsaw. That was not to happen, due to COVID, and the next two years were Zoom affairs. When the pandemic’s grasp began to ease, the Polish plan was back on the table— only for the conflict in neighbouring Ukraine to put an end to those hopes. Ireland manfully stepped in to host us at The Curragh in 2022; and so, when our party—of 48, from 19 countries—finally descended on the Polish capital on the middle weekend of May, there was a palpable feeling of relief.

By common consent, it was worth the wait.

Following the pattern introduced in Ireland, the event was split across two days. The first afternoon was devoted to all the things that one associates with a General Assembly: financial, membership and administrative matters, together with updates, from each member country present, on the state of racing in their respective nations, as well as from various relevant committees and sister organisations. The hosts also gave a colourful account of the rollercoaster that is the history of racing in their homeland.

We were pleased to welcome, once again, representatives of the European Federation of Thoroughbred Breeders’ Associations (EFTBA) and the European and African Stud Book Committee (EASBC). Because the EMHF has long taken the view that we in the equine sector should avoid operating in isolation, and instead benefit from cross-fertilisation of knowledge and ideas, these organisations, together with the European Trotting Union (UET) and European Equestrian Federation (EEF), are standing invitees to our General Assemblies.

After an excellent dinner that evening at the elegant Rozana restaurant in the Konstancin area of the city, our second morning was wider in its scope, and the floor was given to a number of experts who presented on a range of matters of current interest or concern.

Police involvement in French racing

Those who followed the high-profile rape allegations against Pierre Charles Boudot or the arrests of the Rossi trainer brothers might have been struck and intrigued by the closeness of the involvement of the French police. Henri Pouret, EMHF executive council member for France, explained how there is a branch of the national French police force—the Service Centrale Courses et Jeux—dedicated to racing and gaming matters. No licenced or registered participant in French racing—be they owner, trainer, jockey or breeder—is allowed to participate unless their registration is authorised by the ‘racing police’. Then, once registered, if such an individual becomes subject to judicial proceedings, the racing police may require France Galop, or its trotting equivalent, Le Trot, to withdraw or suspend their licence. This is not just a theoretical power—on no fewer than 25 occasions did they do just this in the course of last year.

It is only for the past three years that doping a racehorse has been a criminal act in France. It seems likely that the racing police will play an ever more central part in the regulation of French racing.

FEGENTRI and the International Pony Racing Championship

With EMHF’s formation last year of the European Pony Racing Association (EPRA) and the launch in 2023 of FEGENTRI’s Junior Championship, never has there been a more opportune time to explore and develop the relationship between the amateur and professional communities in European racing. It was therefore a pleasure to receive FEGENTRI’s secretary-general, Charlotte Rinckenbach, to explain the work and relevance of her organisation.

FEGENTRI, the international federation of gentlemen and lady riders, has a history that stretches back to 1955. It is therefore longer established, not only longer than the EMHF, but also longer than both the IFHA and the Asian Racing Federation. It organises amateur races around the world, across four main championships, and prides itself on providing a distinct and effective route by which to involve people in our sport from diverse walks of life.

FEGENTRI Junior is the first international pony racing championship of its kind. It has started in a modest way, with four countries each fielding two young riders, aged between 14 and 16 years. (The competition, which has the full support of the EPRA, is open to those of 12 years and over; but no-one younger than 14 was chosen this year). Their level of experience varies greatly—some have only ridden in a dozen races; others have 150 rides and over 50 winners under their belts. These eight trail-blazing youngsters have the wonderful opportunity of riding competitively in Florence, Bro Park, Chantilly, Livorno and Kincsem Park. And who’s to say that, from amongst them, we will not see a champion of the future?

Gene doping and its implications for EMHF members

‘Gene doping is not a rumour anymore’, was the stark opening warning from Dr Kanichi Kusano of the Japan Racing Association, one of the world’s experts in this sphere. He explained that the abuse of genetic therapies is a major threat to racing’s integrity. In the worst-case scenario, the heritable genome of a thoroughbred would be changed through genetic modification at the breeding stage—of the eggs, sperm or embryo. The good news is that, in this race, the ‘good guys’ are up with the pace, and already there are out of competition (OOC) tests for gene doping that are being deployed.

Smaller countries, without extensive resources to direct towards research or detection, were advised to prepare by ensuring their rules adequately outlawed the practice and to publicise and start a programme of deterrent sample collection, followed by OOC testing as soon as the leading racing nations offer a suitable commercial service.

The World Pool

Tallulah Wilson, UK Tote Group’s head of international racing, spoke of the burgeoning impact of the World Pool and how EMHF countries could get involved through the World Tote Association (WoTA). World Pool, the Hong Kong-based system for commingling bets placed on key international races, is only four years old; but it has already demonstrated that races selected for inclusion enjoy a startling increase in pool betting turnover.

Higher liquidity attracts the high-rollers and creates a virtuous circle from which the participating racecourses benefit, potentially boosting prize money. However, legislative restrictions in Hong Kong mean that the races included do not number in the thousands, or even hundreds. Just 25 race days, predominantly in Britain and Ireland, will form the 2023 roster. While this number is growing, the prospects of most EMHF member countries having a race included in the near term are only distant (although fresh ground has been broken this year through the inclusion—as a single race from a different country within a World Pool Day—of the German Derby).

However, Wilson’s message was that ‘everyone is welcome’ within WoTA. Member countries’ Tote operators were encouraged to apply to join, opening up the possibility of their punters being able to bet into the commingled World Pools and earning that pool operator and its racing industry a slice of the take-out.

Racing to school and National Racehorse Week

For over 20 years, a British programme has been introducing racing to schoolchildren, presenting aspects of their school curriculum through the lens of a visit to a racecourse, training yard or stud. John Blake, CEO of Racing to School, spoke of 16,000 children who attended such a course last year, instilling in many of them a positive sentiment towards the sport, which may hopefully translate in time into ownership or professional involvement.

The third National Racehorse Week in Britain will take place in September, when racing yards and stud farms will open their doors to welcome members of the public. Over 10,000 took up the offer last year, of whom one-fifth were new to racing.

At a time when our sport’s public image is under increasing pressure, these positive interactions with the public are initiatives which many member countries could look to replicate.

Racing at Sluzewiec

With the business affairs completed, it was off to the races. The approach to Sluzewiec Racecourse is through a proud avenue of mature trees, and the whole expansive site was lush and green. The stands were indeed grand, completed, with unfortunate timing, in 1939—just before the onset of war. An attractive feature of the main grandstand is a sloping, stepless zigzag by which one ascends and descends from floor to floor. It makes for a photogenic feature—ideal for the fashion catwalks that are sometimes staged there.

The EMHF Cup was run over a mile for unraced three-year-olds worth €3,200. It attracted a field of eight runners. The winner, Sopot was one of only two Polish-breds, taking on horses foaled in Great Britain, France, Czech Republic and Ukraine.

The nine-race card was worth a total of €24,000. A mixed programme comprised thoroughbred, trotting and Arab races, from 1300m (6 1/2f) up to 2400m (1 1/2m). No race attracted fewer than seven runners and the largest field was 11. Interestingly, in an apprentice race, for riders who had ridden fewer than 25 winners, the whip was not allowed to be carried, let alone used.

Horserace betting is not ingrained in Polish society, and there was little evidence of avid form study, or raucous cheering. However, the crowd’s demographic was a revelation: it was hard to spot a grey hair, with patrons almost exclusively families or young adults. It made for a beguilingly relaxed atmosphere.

Our horizons have been broadened by the experience of witnessing racing in such diverse settings across the EuroMed region as Waregem, (Belgium), La Zarzuela (Madrid, Spain), Kincsem Park (Budapest, Hungary), Casablanca (Morocco), Leopardstown and The Curragh (Ireland), St. Moritz (Switzerland), Bro Park (Sweden), Hamburg (Germany), Marcopoulo (Athens, Greece), Bratislava (Slovakia), Les Landes (Jersey, Channel Islands), Pardubice (Czech Republic), Ovrevoll (Oslo, Norway), Veliefendi, Istanbul and Izmir (Turkey), Cheltenham (Great Britain) and now Warsaw.

Seeing the sport flourish in such varied surroundings brings home the need to do all we can to preserve racing in every country in which it currently takes place. Singapore’s decision to draw the curtain down on horseracing was such dispiriting news. A broad and thriving base to our pyramid enriches us all.

First EuroMed Stewards’ Conference

Few things in international racing excite as much comment and criticism as comparing decisions taken by stewards around the world. There is a constant cry for consistency in the rules that apply to the running of a race, in the way stewards interpret both the races and the rules, and in the levels of penalty handed down. Harmonisation of such matters is a real challenge, not least because there is nobody in horse racing that sets world rules; each national racing authority sets its own. But that is not to say that substantial efforts are not made constantly to improve things in this area. It is the very raison d’etre of the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities’ (IFHA’s), International Harmonisation of Racing Rules Committee (IHRRC), and is also the subject of much of the discussion at the International Stewards’ Conferences (ISC) that the IFHA has staged, roughly every two years, around the world.

But these meetings must limit the numbers of delegates in attendance, and it is in practice that only the major racing nations benefit from being party to the discussions. For this reason, it was decided to stage a Stewards’ Conference for the EuroMed region and to welcome all EMHF member countries—large and small. This suggestion, proposed by Germany, was picked up with enthusiasm by Britain. Thus, it came to be that the day after the General Assembly, the BHA’s Brant Dunshea chaired the inaugural EuroMed Stewards’ Conference, which attracted a pleasing turnout of 30 delegates from 12 countries.

Joining from Australia via Zoom was Kim Kelly, who has for many years chaired both the IHRRC and ISC; he set the scene and placed this gathering into its global context. There followed a range of presentations, including the following.

Competency-based training programme

The job of the steward is high-profile, highly-charged and perpetually subject to criticism from both the media and the public. The BHA’s Cathy O’Meara described how Britain has recently introduced a competency-based training programme to ensure that its stewarding workforce, along with all raceday teams, is (and remains) up to the job. Through a combination of interactive on-line learning, shadowing, mentoring and more, stewards learn, and are then assessed on, race reading, the rules, enquiry training and report writing. And, once initial competencies are met, the learning journey is not over. All stewards will be required to complete continued professional development, where half of the content relates directly to their roles and half to general industry-related issues such as equine and human welfare. A next step will be to develop a module for the use of those in the industry, such as trainers and the general public. The BHA also has plans to offer to receive stewards from smaller racing nations to assist in their development.

Illegal betting

The EMHF’s equivalent in the Asian and Oceanian region, the Asian Racing Federation (ARF) and, in particular, Hong Kong, is on the front line in a battle against illegal betting. The ARF has established a Council on Anti-Illegal Betting and Related Financial Crime; and its chair, Martin Purbrick, joined us by video conference.

The stark facts are that illegal betting is growing much more quickly than legal betting and already represents the majority of online betting. Aside from the fact that illegal betting makes no contribution to racing, nor to society at large, through taxation, it is also intrinsically linked to race-fixing and organised crime. While Asia may be the historic hotbed of this activity, Purbrick cautioned that Asian illegal betting has already expanded into Europe.

Online betting is no respecter of national boundaries, and if we are to be successful in this war, it will require a joined-up, cross-border and multi-agency approach, involving governments, racing authorities, gambling authorities and the police. But we cannot leave it to these organisations alone—it is incumbent upon all of us to be aware of the risks of race manipulation and to whistle-blow if ever we encounter it.

Virtual stewards’ room

This column (April 2020) described a novel system of remote stewarding, witnessed by the author in Johannesburg. It looked forward to a day when Stewards are situated at a central location, away from the track, from which they communicate with the principals on-track and view video footage. This might be widely adopted, promising more consistent application of the rules and the opportunity for smaller countries to outsource their stewarding function to larger countries.

The Conference heard how this brave new world might just have moved a step closer. The BHA reported on a system first trialled in 2020 and prompted by the COVID outbreak. The pandemic created a situation in which there was a real risk of stewards being unavailable due to a requirement to isolate. In response, assistant stewards began working remotely, through video conferencing from their homes, but initially without access to the full range of views available to the stewards on-course. The BHA then set about developing a hub, away from the racecourse, which offered the full range of race replays. While it was considered there was still the need to have a senior person on the course, the hub provided resilience against absence, allowed stewards to officiate at afternoon and evening meetings on the same day, etc.

The trial has now been rolled out in Britain, such that all assistant stewards have the option to work from home, improving their work/life balance. Around 25 percent of fixtures are covered by the technology, and it is planned to expand this further in the future.

Anti-doping activities

It has long been appreciated that trainers, when racing in different jurisdictions, should, as far as is practicable, be assured of facing similar treatment regarding medication control. To that end, the European Horseracing Scientific Liaison Committee (EHSLC) was set up over 30 years ago and continues to lead on this area of racing administration in our region. The Conference heard how the EHSLC (which is comprised of the chief veterinary officer/anti-doping manager from the member countries, representatives of the national laboratories, which carry out regulatory work for those countries, specialist pharmacologists and senior administrators from the racing authorities) has generated a significant amount of data relating to common use medications and has published detection times for many substances. The science underlying these data is rigorous and the subject of considerable review and has often been accepted by the wider global racing community, forming the basis of international screening limits.

Feedback on the inaugural EuroMed Stewards’ Conference has been universally positive, and there is much enthusiasm to make this a regular event, perhaps again being staged alongside our General Assemblies.

Train, Race, Recover and Repeat – How targeted nutrition can support the recovery process to optimise performance

Article by Dr Andy Richardson BVSc CertAVP(ESM) MRCVS

Introduction

Horses evolved as herd-living herbivores with a digestive tract designed to cope with a near continuous dietary input of forage in the form of a wide range of plant species. A large hindgut acts as a fermentation vessel where gut microbiota (predominantly a mix of bacteria, protozoa and fungi) exist in harmony with the horse in order to digest the fibre rich plant material.

Fibre is important to the horse for several reasons. The digestion of fibre releases energy and other key nutrients to the horse. Fibre also acts to provide bulk in the digestive tract, thus helping maintain the passage of faecal material through the system. Fibre also acts like a sponge to absorb water in the gut for release when required.

As horses became domesticated and used for work or sporting purposes, more energy-dense feeds in the form of cereal grains were introduced to their diet, as simple forage did not provide for all the caloric requirements. Cereal grains are rich in starch, which is an energy-dense form of nutrition. However, too much starch can cause problems to a digestive tract that remains designed for a pasture-based diet. The issues that can be caused by the trend away from a solely pasture-based diet can be digestive, behavioural or clinical.

Nonetheless, the combination of forage and cereal-based concentrates remains the mainstay approach for the majority of horses in training today, in order to maximise performance. A great deal of research and expertise are utilised by the major feed companies to ensure that modern racehorse concentrate feeds provide adequate provision of the major nutrients required and minimise unwanted effects of starch in the diet.

This article aims to discuss some scenarios where targeted or supplemented nutrition can act to help overcome some of the nutritional challenges faced by the modern horse in training, as they “Train, Race, Recover and Repeat.”

Equine Gastric Ulceration Syndrome (EGUS)

EGUS occurrence in racehorses is well documented, with prevalence shown to be over 80% in horses in training (Vatistas 1999). With a volume of approximately 2–4 gallons (7.53–15 litres), the stomach in horses is relatively small compared to their overall size due to its functional role in accommodating trickle feeding that occurs during their natural grazing behaviour.

As a horse chews, it produces saliva, which is a natural buffer for stomach acid. When the horse goes for a period of time without chewing, the production of saliva ceases, and stomach acid is not as effectively neutralised. The lower half of the stomach is better protected from acid due to its more resistant glandular surface. The upper, or squamous, region does not have such good protection, however, and this can be a problem during exercise when acid will physically splash upwards, potentially leading to gastric ulceration.

In practice, this can presentrepresent a challenge for horses in training. Typically, they will be fed a concentrate-based feed in the early morning that stimulates a large influx of acid in order to help digest the starch. This may be followed by a period without ad-lib access to hay, thus reducing the amount of saliva subsequently produced to act as a buffer. When the horse is subsequently worked, there is a risk of acid damaging the upper squamous region of the stomach. There is some evidence to suggest that the provision of hay in advance of exercise may act like a sponge for the acid, as well as helping form a fibrous matt to minimise upward splash.

Gastric ulceration can go undetected in horses in training and may not lead to any obvious clinical signs. In other horses, it can lead to colic, poor appetite, dull coat and behavioural changes. In both scenarios, it is likely that the ulceration will have an impact on their performance, with decreased stride length, reduced stamina and inability to relax at speed all being possible consequences (Nieto 2009). Gastric ulceration can therefore have a significant impact on the ability of a horse to perform optimally day in day out in a training environment. This is exacerbated when ulceration leads to a reduction in appetite, with the obvious downside of a reduction in calorie intake leading to condition loss and further drop in performance.

This is an area where targeted nutrition has been clinically proven to play an important role. Ingredients such as pectin, lecithin, magnesium hydroxide, live yeast, calcium carbonate, zinc and liquorice have all been studied as having beneficial effects on gastric ulceration (Berger 2002, Loftin 2012, Sykes 2013). It is likely that a combination of the active ingredients will be most efficacious, with benefits noted when the supplement is added to the feed ration to help neutralise acid and form a gel-like protective coating on the stomach surface.

The daily administration of a targeted gastric supplement can be an important part of daily nutrition of the horse in training, alongside the use of pharmaceuticals such as omeprazole or esomeprazole when required.

Sweat loss

Horses have one of the highest rates of sweat loss of any animal, with sweat being comprised of both water and electrolyte ions such as sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium and calcium. Therefore, it is not surprising that horses in training are at risk of unwanted issues should sweat loss not be replaced.

It is also worth noting that transportation can also lead to excessive sweat loss, with studies showing sweat rates of 5 litres per hour of travel on a warm day (van den berg 1998).

If the electrolytes lost in sweat are not adequately replaced, a drop in performance can result, as well as clinical issues such as thumps, dehydration and colic.

Electrolytes play key roles in the contraction of muscle fibres and transmission of nerve impulses. Horses without adequate electrolyte levels are at risk of early onset fatigue that may result in reduced stamina. It is also worth noting that horses that train on furosemide will have higher levels of key electrolyte losses, so will require targeted support to help maintain performance levels (Pagan 2014).

There is also evidence to suggest that pre-loading of electrolytes may be beneficial (Waller 2022). For horses in daily work, the addition of electrolytes to the evening feed will not only replace losses but also help optimise levels for the following day’s travel or race. The benefit of providing electrolytes with feed is that it will minimise the risk of the electrolyte salts irritating the stomach lining, which can occur if given immediately after exercise on an empty stomach. Feeding electrolytes when the horse is relaxed back in the stable will also allow them to drink freely, with the added benefit that electrolytes will stimulate the thirst reflex when they are relaxed, ensuring they are adequately hydrated for the following day.

Products should be chosen on the basis of adequate key electrolyte provision as not all products will provide meaningful levels of all the key electrolyte ions.

Muscle soreness

The process of muscle breakdown and repair is a normal adaptive response to training. This process can lead to inflammation and soreness or stiffness after exercise. In humans, there is a well-recognised condition called Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS).

Further research is required to fully understand the impact of DOMS in horses. DOMS is the muscular pain that develops 24–72 hours after a period of intense exercise. There is no pain felt by the muscles at the time of exercise, in contrast to a ‘torn muscle’ or ‘tying-up’ for example.

In humans, DOMS is thought to be the result of tiny microscopic fractures in muscle cells. This happens when doing an activity that the muscles are not used to doing or have done it in a more strenuous way than they are used to.

The muscles quickly adapt to being able to handle new activities, thus avoiding further damage in the future; this is known as the “repeated-bout effect”. When this happens, the micro-fractures will not typically develop unless the activity has changed in some substantial way. As a general rule, as long as the change to the exercise is under what is normally done, DOMS are not experienced as a result of the activity.

In practice, avoiding any post-exercise muscle soreness in a training programme may be unavoidable, as exercise intensity and duration increases. Horses are far from being machines, so there is a fine balance between a programme that gets a horse fit for purpose without some post-exercise muscle discomfort. Physiotherapy, swimming and turnout will all likely benefit horses experiencing muscle discomfort. Whilst non-steroidal anti-inflammatories will always have their place for horses in training, one area of advancement is the use of plant-based phytochemicals to support the anti-inflammatory response (Pekacar 2021). These may have the benefit of not leading to unwanted gastrointestinal side effects and not having prolonged withdrawal times, although this should always be checked with any supplement particularly with the recent update regarding MSM on the BHA prohibited substance list.

Exercise will also lead to a process of muscle cell damage caused by oxidative stress. This is an inflammatory process and recovery from oxidative stress is key to allow for muscle cell repair and growth. Antioxidants are compounds that help recovery and repair of muscle cells following periods of intense exercise. The process of oxidative stress in muscle cells can lead to muscle fatigue and inflammation if left unsupported. Antioxidant supplementation in the form of Vitamin E or plant-based compounds can help protect against excessive oxidative stress and support muscle repair after exercise (Siciliano 1997).

Conclusion

Nutritional management of horses in training is a complex topic, not least as every horse is an individual and so often needs feeding accordingly. Whilst there is a lot of science available on the subject, the ‘art of feeding’ a racehorse—something that trainers and their staff often have in-depth knowledge of— remains an incredibly important aspect. Targeted nutritional supplements undoubtedly have their place, as discussed in, but not limited to, the scenarios above.

Veterinarians, physiotherapists, other paraprofessionals and nutritionists all play a role in minimising health issues and maximising performance. In the quest for optimal performance on the track, nutritional support is one of the cornerstones of the ‘marginal gains’ theory that has long been adopted in elite human athletes. There is no doubt that racehorses themselves are supreme athletes that live by the mantra of Train, Race, Recover, and Repeat.

References

Berger, S. et al (2002). The effect of acid protection in therapy of peptic ulcer in trotting horses in active training. Pferdeheilkunde 27 (1), 26-30,

Loftin, P. et al (2012). Evaluating replacement of supplemental inorganic minerals with Zinpro Performance Minerals on prevention of gastric ulcers in horses. J.Vet. Int. Med. 26, 737-738

McCutcheon, L.J. and geor R.J. (1996). Sweat fluid and ion losses in horses during training and competition in cool vs. hot ambient conditions: implications for ion supplementation. Equine Veterinary Journal 28, Issue S22.

Nieto, J.E. et al (2009). Effect of gastric ulceration on physiologic responses to exercise in horses. Am. J. Vet. Res.70, 787-795.

Pagan, J.D. et al (2014). Furosemide administration affects mineral excretion in exercised Thoroughbreds. In: Proc. International Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology S46:4.

Pekacar, S. et al (2021). Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects of Rosehip in Inflammatory Musculoskeletal Disorders and Its Active Molecules. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 14(5), 731-745.

Rivero, J.-L.L. et al (2007). ‘Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses’. Journal of Applied Physiology 102(5), 1871–1882.

Siciliano, P.D. et al (1997). Effect of dietary vitamin E supplementation on the integrity of skeletal muscle in exercised horses. J Anim Sci.75(6), 1553-60.

Sykes, B. et al (2013). Efficacy of a combination of a unique, pectin-lecithin complex, live yeast, and magnesium hydroxide in the prevention of EGUS and faecal acidosis in thoroughbred racehorses: A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Equine Veterinary Journal, 45, 16.

van den Berg, J. et al (1998). Water and electrolyte intake and output in conditioned Thoroughbred horses transported by road. Equine Vet J. 30(4), 316-23.

Vatistas, N.J. et al (1999) Cross-sectional study of gastric ulcers of the squamous mucosa in thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet J Suppl. 29, 34–39.

Waller, A.P., and M.I. Lindinger. (2022). Tracing acid-base variables in exercising horses: Effects of pre-loading oral electrolytes. Animals (Basel) 13(1), 73.

Thermoregulation in horses

Article by Adam Jackson - MRCVS

Exertional heat illness (EHI) is a complex disease where thoroughbred racehorses are at significant risk due to the fact that their workload is intensive in combination with the high rate of heat production associated with its metabolism. In order to understand how this disease manifests and to develop preventative measures and treatments, it is important to understand thermoregulation in horses.

What is thermoregulation?

With continuous alteration in the surrounding temperature, thermoregulation allows the horse to maintain its body temperature within certain limits. Thermoregulation is part of the greater process of homeostasis, which is a number of self-regulating processes the horse uses to maintain body stability in the face of changing external conditions. Homeostasis and thermoregulation are vital for the horse to maintain its internal environment to ensure its health while disruption of these processes leads to diseases.

The horse’s normal temperature range is 37.5–38.5°C (99–101°F). Hyperthermia is the condition in which the body temperature increases above normal due to heat increasing faster than the body can reduce it. Hypothermia is the opposite condition, where the body temperature decreases below normal levels as the body is losing heat faster than producing it. These conditions are due to the malfunction of thermoregulatory and homeostatic control mechanisms.

Horses are colloquially referred to as warm-blooded mammals—also known as endotherms because they maintain and regulate their core body, and this is opposite ectotherms such as reptiles. The exercising horse converts stored chemical energy into mechanical energy when contracting various muscles in its body. However, this process is relatively inefficient because it loses roughly 80% of energy released from energy stores as heat. The horse must have effective ways to dissipate this generated heat; otherwise, the raised body temperatures may be life threatening.

Transfer of body heat

There are multiple ways heat may be transferred, and this will flow from one area to another by:

1. Evaporation

The main way body heat is lost during warm temperatures is through the process of evaporation of water from the horse’s body surface. It is a combination of perspiration, sweating and panting that allows evaporation to occur.

Sweating is an inefficient process because the evaporation rate may exceed the body heat produced by the horse, resulting in the horse becoming covered and dripping sweat. This phenomenon occurs faster with humid weather (high pressure).

Insensible perspiration is the loss of water through the skin, which does not occur as perceivable sweat. Insensible perspiration takes place at an almost constant rate and is the evaporative loss from skin; but unlike sweating, the fluid loss is pure water with no solutes (salts) lost. The horse uses insensible perspiration to cool its body.

It is not common for horses to pant in order to dissipate heat; however, there is evidence that the respiratory tract of the horse can aid in evaporative heat loss through panting.

2. Conduction

Conduction is the process where heat is transferred from a hot object to a colder object, and in the case of the horse, this heat transfer is between its body and the air. However, the air has poor thermal conductivity, meaning that conduction plays a small role in thermoregulation of the horse. Conduction may help if the horse is lying in a cool area or is bathed in cool water.

The horse has the greatest temperature changes occurring at its extremities, such as its distal limbs and head. The horse can alter its blood flow by constricting or dilating its blood vessels in order to prevent heat loss or overheating, respectively.

Interestingly, the horse will lie down and draw its limbs close to its body in order to reduce its surface area and to control conduction. There also have been some adaptive changes in other equids like mules and burros, where shorter limbs, longer ears and leaner bodies increase its surface area to help in heat loss tolerance.

3. Convection

Convection is the rising motion of warmer areas of a liquid or gas and the sinking motion of cooler areas of the liquid or gas. Convection is continuously taking place between the surface of the body and the surrounding air. Free convection at the skin surface causes heat loss if the temperature is low with additional forced convective heat transfer with wind blowing across the body surface.

When faced with cold weather, a thick hair coat insulates and resists heat transfer because it traps air close to the skin; thus, preventing heat loss. Whereas, the horse has a fine hair coat in the summer to help in heat loss.

4. Radiation

Radiation is the movement of heat between objects without direct physical contact. Solar radiation is received from the sun and can be significant in hot environments, especially if the horse is exposed for long periods of time. A horse standing in bright sunlight can absorb a large amount of solar radiation that can exceed its metabolic heat production, which may cause heat stress.

How the horse regulates its body temperature

The horse must regulate its heat production and heat loss using thermoregulatory mechanisms. There are many peripheral thermoreceptors that detect changes in temperature, which leads to the production of proportional nerve impulses. These thermoregulators are located in the skin skeletal muscles, the abdomen, the spinal cord and the midbrain with the hypothalamus being instrumental in regulating the internal temperature of the horse. A coordinating centre in the central nervous system receives these nerve incoming impulses and produces output signals to organs that will alter the body temperature by acting to reduce heat loss or eliminate accumulated heat.

The racehorse and thermoregulation

The main source of body heat accumulation in the racehorse is associated with muscular contraction. At the initiation of exercise, the racehorse’s metabolic heat production, arising from muscle contraction, increases abruptly. The heat production does alter the level of intensity of the work as well as the type of exercise undertaken.

During exercise, the core body temperature increases because heat is generated and the horse’s blood system distributes this heat throughout the body. Hodgson and colleagues have theorised and confirmed via treadmill studies that the racehorse has the highest rate of heat production compared to other sporting horses. In fact, the racehorse’s body temperature can rise 0.8°C per minute, reaching 42.0°C. But what core temperature can the horse tolerate and not succumb to heat illness and mortality? The critical temperature for EHI (exertional heat illness) is not known, but studies have demonstrated that a racehorse can be found to have core temperatures between 42–43°C without any clinical symptoms. Currently, anecdotal evidence is only available, suggesting that a core temperature of 43.5°C will result in manifestation of EHI with the horse demonstrating central nervous system dysfunction such as ataxia (incoordination). In addition, temperatures greater than 44°C result in collapse.

Heat loss in horses

A horse loses heat to the environment by a combination of convection, evaporation and radiation, which is magnified during racing due to airflow across the body. However, if body heat gained through racing is not minimised by convection, then the racehorse’s body temperature is regulated entirely by evaporation of sweat. This evaporation takes place on the horse’s skin surface and respiratory tract.

The horse has highly effective sweat glands found in both haired and hairless skin, which produces sweat rates that are highest in the animal kingdom. Efficient evaporative cooling is present in the horse because its sweat has a protein called latherin, which acts as a wetting agent (surfactant); this allows the sweat to move from its skin to the hair.

Because of the horse’s highly blood-rich mucosa of its upper respiratory tract, the horse has a very efficient and effective heat exchange system. Estimates suggest this pathway dissipates 30% of generated heat by the horse during exercise. As the horse exercises, there is blood vessel dilation, which increases blood flow to the mucosa that allows more heat to be dissipated to the environment. When the respiratory tract maximises evaporative heat loss, the horse begins to pant. Panting is a respiratory rate greater than 120 breaths per minute with the presence of dilated nostrils; and the horse adopts a rocking motion. However, if humidity is high, the ability to evaporate heat via the respiratory route and skin surface is impaired. The respiratory evaporative heat loss allows the cooling of venous blood that drains from the face and scalp. This blood may be up to 3.0°C cooler than the core body temperature of 42.0°C. And as it enters the central circulatory system, it can significantly have a whole-body cooling effect. This system is likely an underestimated and significant means to cool the horse.

Pathophysiology of EHI in the thoroughbred

Although it is inconsistent to determine what temperature may lead to exertional heat illness (EHI), it is known that strenuous exercise, especially during heat stress conditions leads to this disease. In human medicine, this disease is recognised when nervous system dysfunction becomes apparent. There are two suggested pathways that lead to EHI, which may work independently or in combination depending on the environmental factors that are present during racing/training.

1. Heat toxicity pathway

Heat is known to detrimentally affect cells by denaturing proteins leading to irreversible damage. In general, heat causes damage to cells of the vascular system leading to widespread intravascular coagulation (blood clot formation), pathologically observed as micro thrombi (miniature blood clots) deposits in the kidneys, heart, lungs and liver. Ultimately, this leads to damaged organs and their failure.

Heat tissue damage depends on the degree of heat as well as the exposure time to this heat. Mammalian tissue has a level of thermal damage at 240 minutes at 42°C, 60 minutes at 43°C, 30 minutes at 44°C or 15 minutes at 45°C. This heat damage must be borne in mind following a race requiring suitable and appropriate cooling methods, otherwise inadequate cooling may lead to extended periods of thermal damage causing disease.

The traditional viewpoint is that EHI is caused by strenuous exercise in extreme heat and/or humidity. However, recent studies have revealed that environmental conditions may only cause 43% of EHI cases, thus, suggesting that other factors are involved.

2. Heat sepsis pathway

In some instances. a horse suffering from EHI may present with symptoms and clinical signs similar to sepsis like that seen in an acute bacterial infection.

A bacterial infection leading to sepsis causes an extreme body response and a life threatening medical emergency. Sepsis triggers a chain reaction throughout the body particularly affecting the lungs, urinary tract, skin and gastrointestinal tract.

Strenuous exercise in combination with adverse environmental conditions may lead to sepsis without the presence of a bacterial infection— also known as an endotoxemic pathway—causing poor oxygen supply to the mucosal gastrointestinal barrier. Ultimately, the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract is compromised, allowing endotoxins to enter the blood system and resulting in exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome (EIGS).

However, researchers have observed that EHI in racehorses is unpredictable as EHI may develop in horses following exercise despite “safe” environmental conditions. Even with adequate cooling and resuscitative therapies, tissue damage that occurs demonstrates that thermoregulatory and inflammatory pathways may vary, and hyperthermia may be the trigger but may not necessarily be driving the condition.

Diagnosis of EHI

The diagnosis of EHI is based on the malfunctioning of the central nervous system.

Initially, hyperthermia reduces the blood flow to the cerebrum of the brain, leading to a decrease of oxygen to that area—also known as ischemia. As a result, the clinical signs are:

Extreme restlessness

Confusion

Substantial headache

If this hyperthermia continues, then the blood-brain barrier (an immunological barrier between circulating blood that may contain microorganisms like bacteria and viruses to the central nervous system) begins to leak plasma proteins, resulting in cerebral oedema (build up of fluid causing affected organ to become swollen). If treatment is not initiated at this point, then neuronal injury will result especially in the cerebellum.

EHI follows and involves serious CNS dysfunction. The clinical signs associated with EHI are:

Delirium

Horses unaware of their surroundings

The final stage of EHI occurs when the swollen oedematous brain compresses vital tissue causing cellular damage. The clinical signs of end-stage EHI are:

Collapse

Unconsciousness

Coma

Death

Definition of EHI

EHI most commonly occurs immediately after a race when the horse is panting, sweating profusely and may be dripping with sweat. The most reliable indication of EHI is clinical signs associated with the dysfunction of the central nervous system in the presence of hyperthermia. Researchers have provided descriptions of levels of CNS dysfunction, ranging from level 1 to level 4.

Level 1 – The earliest recognizable signs of CNS dysfunction

The horse becomes restless, agitated and irritable. There is often head nodding or head shaking. The horse is difficult to restrain and will not stand still. Therapeutic intervention such as cooling can resolve these clinical signs, but if the horse is inadequately cooled then the disease can escalate.

Level 2 – Obvious neurological dysfunction

Often misdiagnosed as colic symptoms, the horse becomes further agitated and irritable with the horse kicking out without any particular stimulus present. This stage is dangerous to all handlers involved as the horse’s behaviour is unpredictable.

Level 3 – Bizarre neurological signs

At this stage, the horse has an altered mentation appearing vacant, glassy-eyed and “spaced-out”. In addition, there is extreme disorientation with a head tilt and leaning to one side with varying levels of ataxia (wobbly). It has been observed that horses may walk forward, stop, rear and throw themselves backwards. It is a very dangerous stage, as horses are known to run at fences, obstacles and people. Horses may also present as having a hind limb lameness appearing as a fractured leg with hopping on the good limb. These clinical signs may resolve with treatment intervention.

Level 4 – Severe CNS dysfunction

There is severe CNS dysfunction at this stage of EHI with extreme ataxia, disorientation and lack of unawareness of its surroundings. The horse will continuously stagger and repeatedly fall down and get up while possibly colliding with people or objects with a plunging action. Unsurprising, the horse is at risk of severe and significant injury. Eventual collapse with the loss of consciousness and even death may arise.

Treatment of EHI

In order to achieve success in the treatment of EHI, it is imperative that there is early detection, rapid assessment and aggressive cooling. The shorter the period is between recognising the condition and treatment, the greater the chance of a successful outcome. In particular settings such as racecourses or on particularly hot and humid days, events must be properly equipped with easily accessible veterinary care and cooling devices. It is highly effective if a trained worker inspects every horse in order to identify those horses at risk or exhibiting symptoms.

If EHI is recognised, veterinary intervention will be paramount in the recovery to prevent further illness and suppress symptoms. It will be important to note any withdrawal periods of any non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and analgesics before returning to racing. There are a number of effective ways to cool the horse with easily accessible resources.

Whole body cooling systems

Cooling the horse with ice-cold water is an effective way to draw heat from the underlying tissues. In addition, cooling the skin redistributes cooled blood back to the central circulatory system thus reducing thermal strain with the cooling of core body temperature.

The system that works best for horses due to its size is spray cooling heat transfer. It is ideal to have two operators to spray either side of the horse. It is recommended to begin at the head and neck followed by the chest and forelimbs then the body, hind limbs and between the legs. Spray nozzles are recommended to provide an even coverage of the skin surface.

Dousing is another technique in which horses are placed in stalls and showered continuously until the condition resolves. Pouring buckets over the entire body of the horse is not recommended as most of the water falls to the ground, thus, not efficient at cooling the horse.

Because most horses suffer from EHI immediately after the race, the appropriate location for inspection, cooling systems and veterinary care should be in the dismounting yard and tie-up stalls. There must be an adequate supply of ice to ensure ice-cold water treatment.

When treating a horse with EHI, there must be continuous and uninterrupted cooling until the CNS dysfunction has disappeared.

When the skin surface temperature decreases to 30°C, cutaneous skin vessels begin to disappear; CNS function returns to normal, and there is the normalisation of behaviour. Cooling can be stopped, and the horse can be walked once CNS abnormalities have resolved. It must remain closely monitored for a further 30 minutes in a well-ventilated and shaded region. It is important that they are not unattended.

Scraping sweat off of the horse must only be done if the conditions are humid with no airflow. However, if it is hot and there is good airflow, scraping is unnecessary because the sweat will evaporate.

Cooling collars

During strenuous exercise, there is a combination of heat production in the brain, reduced cerebral blood flow, creating cerebral ischaemia as well as the brain being perfused with hot blood. It is believed that cooling the carotid artery that aids in blood perfusion of the brain might be a strategy to cool the brain. A large collar is placed on either side and around the full length of the horse’s neck and is cooled by crushed ice providing a heat sink around the carotid artery; and it is able to pump cooled blood into the brain.

Another possible benefit of this device is the cooling of the jugular veins, which lie adjacent to the carotid arteries. The cooled blood in the jugular veins enter the heart and is pumped to the rest of the body, hence, potentially cooling the whole body. In addition, it is thought that the cooling of the carotid artery causes it to dilate, allowing greater blood flow into the brain.

Provision of shaded areas

Shaded areas with surfaces that reflect heat, dry fans providing air flow and strategically placed hoses to provide cool water is an important welfare initiative at racecourses in order to minimise risk of EHI and treat when necessary.

Conclusion

The most effective treatment of EHI is the early detection of the disease as well as post-race infrastructure that allows monitoring of horses in cooling conditions, while providing easily accessible treatment modalities when they are needed.

Evaluating the horse’s central nervous system dysfunction is essential to recognise both the disease as well as monitoring the progression of the disease. CNS dysfunction allows one to define the severity of the condition.

Understanding the pathophysiology of EHI is essential. It is important to recognise that it is a complex condition where both the inflammatory and thermoregulatory pathways work in combination. With a better understanding of these pathways, more effective treatment for this disease may be found.

A new mission for Criquette Head

Article by Katherine Ford

Five years after retiring as a trainer, the handler most famous for the Arc double of Trêve wintered in the Bahamas where she devoted herself to caring for her mother Ghislaine during her final months. A figure in French and international racing and bloodstock alongside her late husband Alec, Ghislaine Head was influential in the running of the Haras du Quesnay. Her colours were carried notably by Arc heroine Three Troikas and homebred Prix du Jockey-Club winner Bering; and she passed away peacefully at age 95 in early June.

Horses were far away in the flesh during this time in the Bahamas but still close to Criquette’s heart and very present in her mind. “When would be a convenient time for a chat?” I texted Criquette Head to arrange this interview. The reply pings back, “You can call me at 11.30am French time; I get up at 5am (EST) here every day for my first lot.”

So it is 5.30am in the Bahamas, and Criquette is in fine form as ever with plenty of ideas to discuss. “I’m always wide awake at this time. I can’t get it out of my system. Of course there are no horses here, just water and boats.” When Criquette retired, she announced a plan to sail across the Atlantic in her yacht, named Trêve. However, in typical altruistic style of the former president of the European Trainers Federation, the adventure has been on hold. “My boat is here, but I haven’t done the crossing yet. I will do it one day, but for the moment, my priority is taking care of my mother. I will stay at her side as long as she needs me.”

While she had no physical contact with horses in the Bahamas, and no imminent trans-Altantic sail to prepare for, Criquette has been devoting time and energy recently to the association CIFCH (Conseil Indépendant pour la Filière des Courses Hippiques, or Independent Council for the Racing Industry), which she created with long-time friend and associate Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle some three years ago and now presides.

Senator Anne-Catherine Loisier & Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle.

“The idea came about because I found that our politicians didn’t understand the racing world. I said to myself that as I have some spare time, I would create a little association, and I would try to ask our politicians, those who vote for our laws in the National Assembly or the Senate, to understand what racing means. We are completely separate from any official organisation, and we don’t interfere with France Galop or Le Trot (French harness racing authority). I just want to show the decision makers what racing is all about. I have met a lot of people and invited them to the races. That’s all… I try to make them realise the importance of the racing industry, and the reactions have been very positive.”

An eclectic membership

The CIFCH counts 140 parliamentarians among its membership and supporters, which is a varied panel composed of racing and non-racing people, from a wide professional spectrum.