Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures 2020 - minimising risk from equine infectious disease - how it will hopefully help support education on equine infectious disease

By Celia M Marr

IN ASSOCIATION WITH:

COVID-19 has affected all corners of the thoroughbred world and has changed lives, work patterns and the social activity that underpins racing. One of its minor impacts was that this year, the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lecture series, usually coordinated by Beaufort Cottage Educational Trust at the National Horseracing Museum, Palace House, Newmarket each summer, was cancelled.

This annual lecture series is supported by the Gerald Leigh Charitable Trust in honour of Mr Leigh’s passion for the thoroughbred horse and its health and welfare. Coincidentally, the topic which had been selected for 2020 was Minimising Risk from Equine Infectious Disease. Finding that a meeting was impossible, the trustees organised for presentations to be filmed remotely, and these are now available online.

THE LECTURES SERIES INTRODUCTION BY NICK WINGFIELD DIGBY, CHAIRMAN, BEAUFORT COTTAGE TRUST

Gastrointestinal disease is a common problem in foals and youngstock with potentially serious illnesses involved. Dr Nathan Slovis, director of the McGee Center, Lexington, Kentucky, USA, explained that by six months of age, 20% of foals will have had infectious diarrhoea. Dr Slovis presents a concise and very practical account of how we can minimise risk of infection in this age group.

The specific causes of gastrointestinal disease vary with age. Foals frequently display mild diarrhoea at around the time of the foal heat, generally a problem that will clear up uneventfully. Major infections in foals include rotavirus, Salmonella, Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium difficile. Infectious disease can be life-threatening if infection leads to shock, so every gastrointestinal case should be assessed carefully; early intervention is critical.

Vaccines are available to help minimise risk of rotavirus but prevention relies primarily on proper hygiene and appropriate choice of disinfectants, which vary depending on the particular microorganism concerned.

PRESENTATION BY DR NATHAN SLOVIS, DIRECTOR OF THE MCGEE CENTER, LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY

Diagnosis: PCR and ELISA technologies

The speed and availability of laboratory testing have been revolutionised in recent years with the introduction of ELISA and PCR technology. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is an immunological assay commonly used to measure antibodies, antigens or proteins. An ELISA test relies on finding a molecule which is unique to a virus or bacteria and is used to find several equine pathogens, including rotavirus, Clostridium difficile and Clostridium perfringens.

PCR technology rapidly makes millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample, allowing the lab to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it to a large enough amount to study in detail. Rapid tests are now available, which have revolutionised the diagnostic approach across a huge range of equine infections; relevant to foal diarrhoea is that this technology is used for rapid testing of faecal samples for Salmonella.

In addition to being extremely quick, both PCR and ELISA tests are very sensitive. Dr Slovis emphasised how important this is in early identification of diseases with the potential to spread rapidly in young horses.

Auditing environmental contamination

All the speakers in the webinar series spoke of the importance of robust biosecurity and common themes emerged in all four webinars regardless of the animals’ age or whether respiratory, skin or gastrointestinal infection is involved.

Dr Slovis’ clinical practice includes offering services to identify areas of environmental contamination. This involves a detailed inspection of all areas on the farm together with laboratory testing for the common pathogens. Key benefits of a facility evaluation service are to help support staff education and to highlight areas of weakness in biosecurity practices; and farmers and vets can work together to devise practical solutions to farm-specific problems. In his webinar, Dr Slovis shows some great examples of what not to do, which are drawn from his extensive experience of advising on biosecurity practices in equine facilities.

THE PRESENTATION BY PETER RAMZAN, A MEMBER OF THE RACING TEAM AT ROSSDALES LLP, NEWMARKET, UK:

Infectious challenges in young horses on training yards

Peter Ramzan, member of the Racing Team at Rossdales LLP, Newmarket discussed how to reduce risks when horses move into training. Piet is a fellow of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons and has written extensively on a range of disorders affecting horses in training. He summarised three areas relevant to this age group: lower respiratory tract disease, ringworm and the rare but sporadic disease threats such as strangles and neurological herpes.

Lower respiratory tract disease

This problem is mainly responsible for coughing and affects around 80% of two-year-olds and 25% of three-year-olds. Research in Newmarket has shown that for every 100 horses, there are around 10 cases each month, but prevalence varies between yards and seasons with a peak in early spring. Bacteria are believed to be a more common cause than viral infection, but both can cause coughing and can occur simultaneously.

Prevention is better than cure

Exposure to disease-causing microorganisms is inevitable and cannot be prevented, but risk of clinical disease can be reduced by optimising immunity. It is helpful if exposure occurs prior to or early in training. Ramzan concluded that homebreds that have bypassed public sales and the inevitable mixing with other horses there are at greater risk of interruptions to their training when they do enter yards as two-year-olds. He went on to emphasise that it is not necessarily helpful to aggressively treat respiratory infections in pre-training—better to let infection run through yearlings and young two-year-olds, providing that they remain mildly affected as this helps them build immunity to protect them during their racing careers.

As well as discussing the biosecurity measures which apply across all age groups and disease threats, particular points that Ramzan emphasised for reducing the impact of infectious disease in training yards included the importance of avoiding the introduction of yearlings to the main yards before the end of the season and adoption of a strategic vaccination programme. Vaccines should be given to horses in a year ahead of the influx of yearlings while maintaining immunity throughout the racing season; autumn and spring boosters are most likely to achieve this.

Antimicrobial stewardship

It is increasingly clear that overuse of antimicrobials is promoting resistance to these potentially lifesaving drugs. Vets and trainers should avoid their use, except where bacterial infection is highly likely, or ideally confirmed with laboratory testing. Ideally the lowest class of antibiotics should be used first, reserving protected classes, such as enrofloxacin and ceftiofur. Ramzan shared data from his practice over the last two decades which showed an alarming increase in resistance to oxytetracycline, which is the commonly used antimicrobial. Conversely, in the same period, oral trimethoprim sulphonamide, which is not used as much as it could be, has had a rise in sensitivity, likely because it is not used as often as it could be.

Herpes virus Type 1: a uniquely challenging foe

Professor Lutz Goehring, head of Equine Medicine and Reproduction at Ludwig-Maximilian University, in Munich, Germany, has had a distinguished research career focussed on equine herpes type 1 (EHV1). This virus has the potential to cause both abortion storms and outbreaks of neurological disease in all age groups, including horses in training.

PRESENTATION BY PROF. LUTZ GOEHRING IS HEAD OF EQUINE MEDICINE AND REPRODUCTION AT LUDWIG-MAXIMILIAN UNIVERSITY, IN MUNICH, GERMANY.

Equine Herpes Virus is a real threat to horse health and performance. Racing yards can be particularly vulnerable to outbreaks, but there are some easy steps you can take to reduce the risks.

Dr Wendy Talbot, vet at Zoetis explains: EHV is a contagious viral infection causing respiratory disease, abortions and neurological disease. Carrier horses show no clinical signs, but the virus can be reactivated at any time and spread to other horses and this is more likely to happen during times of stress. 1,2,3

EHV can be transmitted by direct horse-to-horse contact and by nasal or ocular discharge, which can spray or travel through the air over short distances. It can also be spread by sharing infected equipment, and via people who have been in contact with infected horses. This is why it’s crucial to have good biosecurity measures in place at yards, races, training and sales events. 4

Signs of the virus can be visually obvious or very subtle: horses may have a nasal discharge, weepy eyes, swollen glands and a cough and fever or a less noticeable lethargy, lack of appetite and reduced performance. 1,5

Vaccination against EHV is important because it helps tip the balance in favour of the horse’s immune system and reduces viral shedding.

Vaccination programmes should run concurrently with rigorous hygiene and isolation protocols to help minimise the risks of EHV spreading.

It’s also important not to mix unvaccinated horses with vaccinated ones to provide the best level of protection. 6,7

If you think any of your horses may have any symptoms of respiratory disease,isolate them immediately and contact your vet to discuss the next course of action.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION FOLLOW THIS LINK

1. Slater J (2014) Equine Herpesviruses. In: Equine Infectious Diseases. Eds., D.C. Sellon and M. Long, Saunders, St. Louis. P151-169

2. Allen GP (2002) Respiratory Infections by Equine Herpes Virus Types 1 and 4. International Veterinary Information Service.

3. Slater J. What is Equine Herpes Virus? Accessed August 2019 https://www.horsedialog.co.uk/Health/WhatisEHV.aspx

4. Allen, GP (2002) Epidemic disease caused by equine herpesvirus-1: recommendations for prevention and control. Equine Veterinary Education; 14(3):136-142.

5. Davis, E. (2018) Disorders of the respiratory system. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, eds. Equine Internal Medicine, 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier:313-386.

6. Lunn, DP., et al. (2009) Equine herpesvirus-1 consensus statement..J Vet Intern Med. 23(3). 450-461

7. Equine herpesviruses: a roundtable discussion Philip Ivens, David Rendle, Julia Kydd, James Crabtree, Sarah Moore, Huw Neal, Simon Knapp, Neil Bryant J Richard Newton Published Online:12 Jul 2019 https://doi.org/10.12968/ukve.2019.3.S2.1

EHV1, like its virus relatives that cause cold sores in humans, has the ability to become latent. This means that the virus can sit in an inactive form in certain nerves and lymph node tissues, only to be reactivated and start to spread amongst groups of horses. While latent, the virus is out of reach of the immune system. Latent infection with EHV1 is widespread in horse populations globally.

Reactivation of EHV1 is not a common event, but it is associated with “stressful” situations such as mixing with new horses, transport, above-normal exercise, and in mares with foaling. Understanding the mechanisms involved in reactivation, spread to other horses and subsequent uptake of the virus into tissues—such as the placenta and fetus to cause abortion and to the spinal cord to cause neurological signs and paralysis—has been the main focus of Prof Goehring’s research career.

EHV1 is easy to kill with soaps and disinfectants when it is outside the body, again highlighting the importance of good biosecurity practices in studs and training yards. The virus spreads from horse to horse when there is close contact and droplets breathed out by an infected horse are inhaled by another. Shortly after inhaling the virus, there is a short temperature spike and then a second more intense spike usually occurs 8-10 days later. Neurological signs or abortion will typically come days or weeks after this second temperature spike.

Outbreak mitigation

Early detection and effective quarantine are the mainstays of EHV1 outbreak prevention. In the face of a potential outbreak, swift action to stop spread is critical. Movement on and off the property must cease. Horses with subtle clinical signs—slight nasal discharge, lymph node enlargement and fever—can now be tested very quickly for EHV1 using a nasal swab PCR. Horses should be tested to identify any that are shedding the virus; and any which are positive must be removed to isolation. Horses housed near these individuals should be quarantined in case they are incubating the disease. Horses in the early stages of infection may benefit from treatment to prevent neurological complications.

Distance is the key to stopping this droplet-aerosol infection; and although the distance does not need to be great, more is always better. Traditionally racehorses exercise in strings. An exercising horse which is shedding virus creates a tail of viral particles trailing behind it. In his webinar, Prof Goehring talked about the advantages of increasing distance between exercising horses and showed the benefits of exercising alongside rather than one behind the other. When there is infection around, consideration should also be given to the order horses go out to exercise, with those least likely to have infection exercising first.

Immunity, current and future vaccines

Following infection or vaccination, horses produce both antibodies and specialised cells with the ability to fight off EHV1 infection. Vaccination can be expected to reduce both the clinical signs and the shedding of virus if they are challenged. However, this immunity gradually wanes with time and with currently available herpes virus vaccines, repeat vaccination every six months is recommended

.

It is also important to understand that there is a balance between immunity level and infectious dose such that horses which are challenged with a very high dose of virus are more likely to develop fever than those that are exposed to a low dose—this again highlights the importance of effective biosecurity practices on studs and training yards.

Finally, although not yet available for equine herpes viruses, novel sub-unit vaccines introduced for similar herpes viruses in humans have been shown to cement latent virus into its hidden location and stop reactivation. Prof Goehring suggested this technology may be the light at the end of the tunnel for horses because this novel approach may reduce the likelihood of the outbreak initiation, which begins with reactivation of latent virus.

PRESENTATION OF DR. RICHARD NEWTON, DIRECTOR OF EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DISEASE CONTROL AT THE ANIMAL HEALTH TRUST, KENTFORD, UK.

Lessons from the European flu epizootic 2019

Although current attention is on COVID-19, it is important to reflect on lessons from the equine influenza outbreak which affected many countries in Europe last year. Dr Richard Newton, epidemiologist and an authority on equine infectious disease, coordinated much of the UK’s surveillance and communication during this outbreak, working at that time at the Animal Health Trust, Newmarket, Suffolk.

Equine influenza is a contagious rapidly-spreading viral respiratory disease. Common signs of infection include fever and coughing; and coughing is an important factor in spread as infected particles are released and can spread over wide distances to affect others. Unlike EHV1, there is no carrier or latent state, and the flu virus needs chains of transmission to persist in a horse population; an infected horse has to pass the virus on to another in order for the infection to perpetuate in a group. Vaccination is used to break these chains of transmission by reducing susceptibility. However, flu virus evolves continuously, constantly producing new strains; and in order to be effective, vaccine strains must keep up with this evolution and be updated periodically.

The R number: what does it mean?

The R number, or basic reproduction number, is the number of cases on average that one case generates over the course of its infectious period. If the R number is less than one, the chain of transmission will die out, and infection will cease. Vaccination plays a major role in reducing the R number by limiting the number of susceptible animals.

Lessons from 2019

Flu occurred in several countries in Europe last year. In the UK, we saw two waves of this infection whereas other countries, notably Ireland and Holland, had different patterns. The Clade 1 strain of virus involved in the 2019 outbreak had not been seen in Europe for over a decade.

Flu mainly affects non-vaccinated horses but can occur in vaccinated animals, particularly if a new strain challenges a population. Fortunately, prompt action by the British Horseracing Authority last year minimised flu occurrence within our racing population. In January, based on information coming out of other European countries, the BHA veterinary committee advised six monthly booster vaccinations.

A six-day stoppage in racing and horse movements after flu was identified in a racing yard in early February. The majority of flu outbreaks occurred in unvaccinated horses, and the second spike seen in the summer of 2019, was associated with horse gatherings at shows and fairs. Nevertheless 18% of flu cases involved appropriately vaccinated animals, some of which might have been vaccinated after contracting infection, while many of the others were nearing the time when a booster was due.

The UK’s racing populations are highlight connected, and the racing stoppage was prompted by the occurrence of flu in vaccinated animals. This break provided the necessary pause during which the scale of infection could be assessed. A huge number of racehorses were tested, and Dr Newton explained that an important conclusion from this experience was that there is a need to scale up lab testing capacity to support such a response in future, particularly if we were to be challenged by a completely novel strain of flu.

What did we do well?

Racing heeded the earliest warnings with its six-month booster recommendation, applied a lockdown and implemented test and trace and finally, on releasing lockdown, racing applied biosecurity precautions, concepts now familiar to us all in relation to COVID-19.

Dr Newton acknowledged that these lessons were missed or ignored outside of racing, leading to a second wave in the non-thoroughbred during the summer; and horse owners and event organisers did not adequately embrace the simple messages regarding the importance of vaccination and isolation. Many of the outbreaks which occurred last summer were associated with the introduction of new animals on a premise. The UK horse population has a low national vaccine coverage, estimated at around 40%—a statistic which puts the UK in a poor light compared to other European countries where uptake in the general horse population is much higher.

Do we need to improve vaccines and vaccine strategy?

Vaccine strains are continuously reviewed by The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) panel—critical work which in the UK is supported by the Horserace Betting Levy Board. Currently there is insufficient scientific evidence to recommend an equine influenza vaccine strain update, although this might not be far away. On the other hand, reducing booster vaccine intervals is clearly beneficial. Flu vaccines work by stimulating the horse to produce antibodies which decline with time. There is variation in vaccine response between individual horses with some animals less well protected than others. Dr Newton reviewed information from multiple studies and outbreaks and concluded the weight of evidence overwhelmingly supports a six-monthly booster. Increasing vaccine uptake across the national herd will involve improved education in the non-thoroughbred world but is critical to supporting herd immunity. Improved awareness will benefit all horses including thoroughbreds.

Take-home messages

All four speakers highlighted practical biosecurity measures as critical in reducing the risks of infectious disease. Vaccines are essential for both flu and EHV1. They are not infallible, and ongoing research will lead to improved vaccine technology. Most important of all is that education of people working with thoroughbreds, and across the wider equestrian world, will help support early recognition and management of disease when it occurs. This year’s Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures will hopefully help support this education by making information on equine infectious disease available online.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Minimising serious fractures of the racehorse fetlock - risk reducing of catastrophic fractures associated with the fetlock joint

By VA Colgate, PHL Ramzan & CM Marr

Minimising serious fractures of the racehorse fetlock

In March 2020, a symposium was held in Newmarket, UK, aiming to devise measures which could be used internationally to reduce the risk of catastrophic fracture associated with the fetlock joint. The meeting was supported by the Gerald Leigh Charitable Trust, the Beaufort Cottage Charitable Trust and the Jockey Club with additional contributions from a number of industry stakeholders. On the first day a panel of international experts made up of academic professors, Chris Whitton (Melbourne, Australia), Sue Stover (Davis, California), Chris Kawcak (Colorado), Tim Parkin (Glasgow) and Peter Muir (Wisconsin); experienced racehorse clinicians, Ryan Carpenter (Santa Anita) and Peter Ramzan (Newmarket); imaging experts, Sarah Powell (Newmarket) and Mathieu Spriet (Davis, California); and vets with experience in racing regulatory bodies, Scott Palmer (New York) and Chris Riggs (Hong Kong) joined forces to discuss risk assessment protocols, particularly those based on imaging features which might indicate increased risk of imminent fracture. This was followed by a wider discussion with a diverse invited audience of veterinary and industry stakeholders on how our current knowledge of fracture pathophysiology and risk factors for injury could be used to target risk assessment protocols. A report of the workshop outcomes was recently published in Equine Veterinary Journal.

The importance of risk reduction

With the ethics of the racing industry now in the public spotlight, there is recognition that together veterinary and horseracing professionals must strive to realise an improvement in equine injury rates. Intervention through risk profiling programmes, primarily based on training and racing metrics, has a proven track record; and the success of a racing risk management program in New York gives evidence that intervention can and will be successful.

The fetlock of the thoroughbred racehorse is subjected to very great loads during fast work and racing, and over the course of a training career this can result in cumulative changes in the bone underlying the articular cartilage (‘subchondral’ bone) that causes lameness and may in some circumstances lead to fracture. Fracture propagation involving the bones of the fetlock (cannon, pastern or proximal sesamoid bones) during fast work or racing can have catastrophic consequences, and while serious musculoskeletal injuries are a rare event when measured against race starts, there are obviously welfare and public interest imperatives to reduce the risk to racehorses even further. The dilemma that faces researchers and clinicians is that ‘fatigue’ injuries of the subchondral bone at some sites within the fetlock can be tolerated by many racehorses in training while others develop pathology that tips over into serious fracture. Differentiating horses at imminent risk of raceday fracture from those that are ‘safe’ to run has not proven particularly easy based on clinical grounds to date, and advances in diagnostic imaging offer great promise.

Profiling to inform risk assessment

Risk profiling examines the nature and levels of threat faced by an individual and seeks to define the likelihood of adverse events occurring. Catastrophic fracture is usually the end result of repetitive loading, but currently there are no techniques that can accurately determine that a bone is becoming fatigued until some degree of structural failure has actually occurred. However, diagnostic imaging has clear potential to provide information about pathological changes which indicate the early stages of structural damage.

Previous research has identified a plethora of epidemiological factors associated with increased risk of serious catastrophic musculoskeletal injury on the racetrack. These can be distilled into race, horse and management-related risk factors that could be combined in statistical models to enable identification of individual horses that may be at increased risk of injury.

In North America, the Equine Injury Database compiles fatal and non-fatal injury information for thoroughbred racing in North America. Since 2009, equine fatalities are down 23%; and important risk factors for injury have been identified, and this work has driven ongoing improvement.

The problem with all statistics-based models created so far for prediction of racehorse injury is that they have limited predictive ability due to the low prevalence of racetrack catastrophic events. If an event is very rare, and a predictive tool is not entirely accurate, many horses will be incorrectly flagged up as at increased risk. At the Newmarket Fetlock workshop, Prof Tim Parkin shared his work on a model which was based on data from over 2 million race starts and almost 4 million workout starts. Despite the large amount of data used to formulate the model, Tim Parkin suggested that if we had to choose between two horses starting in a race, this model would only correctly identify the horse about to sustain a fracture 65% of the time. Furthermore, the low prevalence of catastrophic injury means it will always be difficult to predict, regardless of which diagnostic procedure is employed.

Where do the solutions lie?

A radiograph showing a racing thoroughbred’s fetlock joint. The arrow points to a linear radiolucency in the parasagittal groove of the lower cannon bone—a finding that is frequently detectable before progression to serious injury.

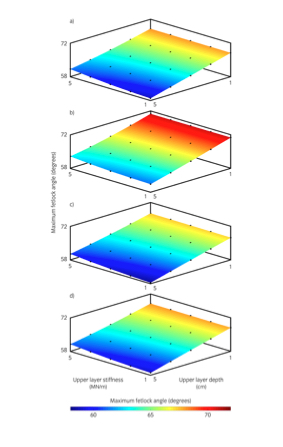

One possible strategy to overcome the inherent challenge of predicting a rare event involves serial testing. Essentially with this approach, a sequence of tests is carried out to refine sub-populations of interest and thus improve the predictive ability of the specific tests applied. An additional consideration in the design of any such practical profiling system would have to be the ability to speedily come to a decision. For example, starting with a model based on racing and training metrics such as number of starts and length of lay-off periods, as well as information about the risk associated with any particular track or racing jurisdiction, entries could be screened to separate those that are not considered to be at increased risk of injury from a smaller sub-group of horses that warrant further evaluation and will progress to Phase 2. The second phase of screening would be something relatively simple. Although not yet available, there is hope that blood tests for bone biomarkers or genetic profiles could be used to further distil horses into a second sub-group. This second sub-group might then be subjected to more detailed veterinary examination, and from that a third sub-group, involving a very small and manageable number of horses flagged as potentially at increased risk, would undergo advanced imaging. The results of such diagnostic imaging would then allow vets to make evidence-based decisions on whether or not there is sufficient concern to prompt withdrawal of an individual from a specific race from a health and welfare perspective. Of course there are other considerations which limit the feasibility of such a system, including availability of diagnostic equipment and whether or not imaging can be quickly and safely performed without use of sedation or other drugs, which are prohibited near to a race start.

Diagnostic techniques for fetlock injury risk profiling

Currently there is no clear consensus on the interpretation of images from all diagnostic imaging modalities, and important areas of uncertainty exist. Although a range of imaging modalities are available, each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and advances in technology currently outstrip our accumulation of published evidence on which to base interpretation of the images obtained.

Interpretation is easy when the imaging modality shows an unequivocal fracture such as a short fissure in a cannon bone. Here the decision is simple: the horse has a fracture and must stop exercising. Many cases, however, demonstrate less clearly defined changes that may be associated with bone fatigue injury.

Currently radiography remains the most important imaging modality in fetlock bone risk assessment. With wide availability and the knowledge gained by more advanced imaging techniques refining the most appropriate projections to use; radiography represents a relatively untapped resource that through education of primary care vets could immediately have a profound impact on injury mitigation. The most suitable projection with which to detect prodromal condylar fracture pathology in the equine distal limb is the flexed dorsopalmar (forelimb) or plantarodorsal (hindlimb) projection. On this projection, focal radiolucency in the parasagittal groove, whether well or poorly defined, with or without increased radio-opacity in the surrounding bone, should be considered representative of fracture pathology unless evidence from other diagnostic imaging modalities demonstrates otherwise.

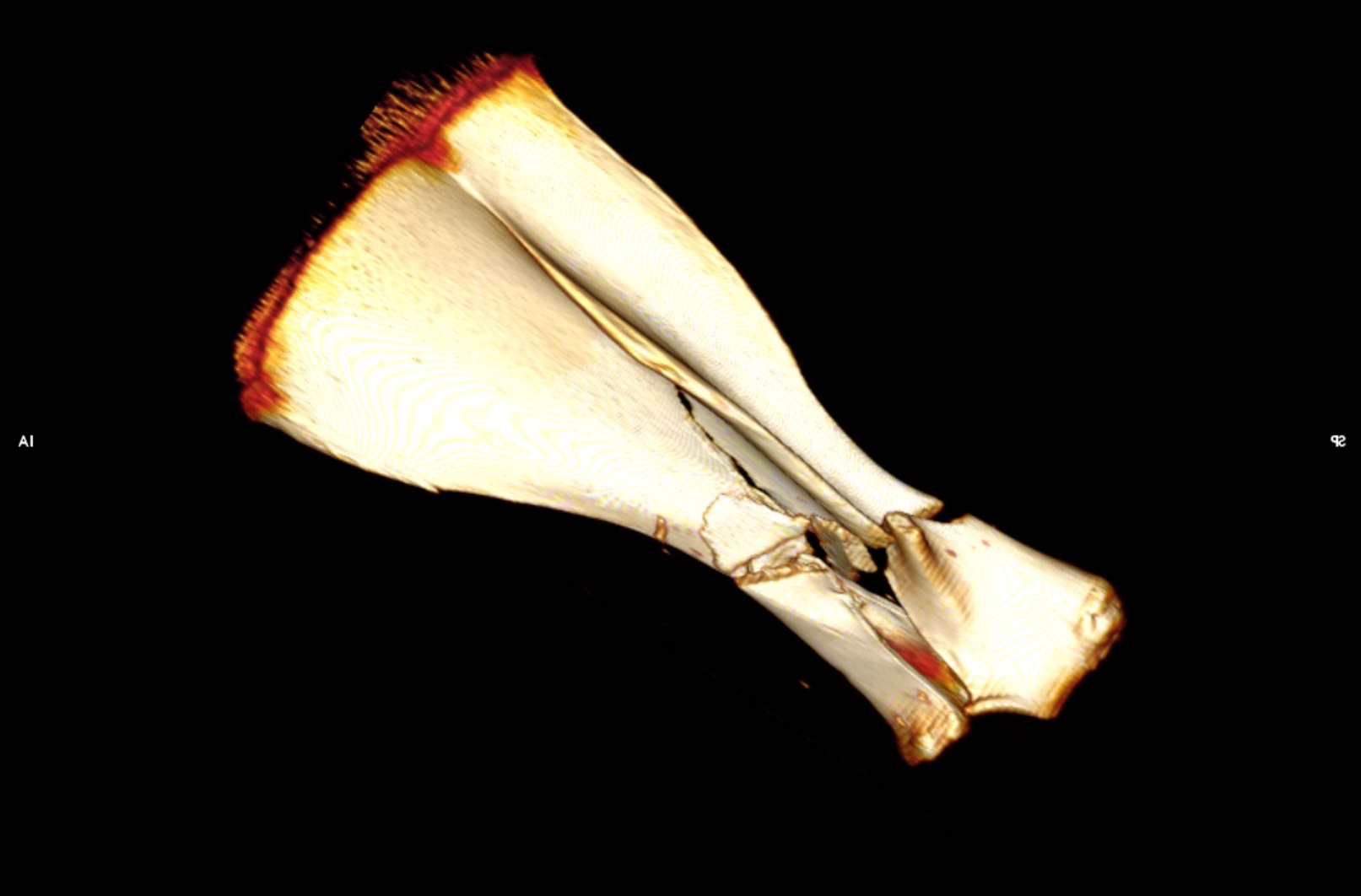

Computed Tomography (CT) excels at identification of structural changes and is better than radiography at showing very small fissures in the bone. However, additional research is needed to determine specific criteria for interpretation of the significance of small lesions in the parasagittal groove with respect to imminent risk of serious injury. There are good indications that fissure lesion size and proximal sesamoid bone volumetric measurements have the potential to be useful criteria for prediction of condylar and proximal sesamoid bone fractures respectively. With technological advancement, it is likely that CT will be more widely used in quantitative risk analysis in the future.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has the ability to detect alterations in the fluid content of bones, which allows assessment of acute, active changes. Indeed standing, low-field MRI has been shown to be capable of detecting bone abnormalities not readily identifiable on radiography and has been successfully used for injury mitigation in racehorse practice for some time. However, when used for evaluation of cartilage and subchondral bone lesions, there is a relatively high likelihood of false positive results.

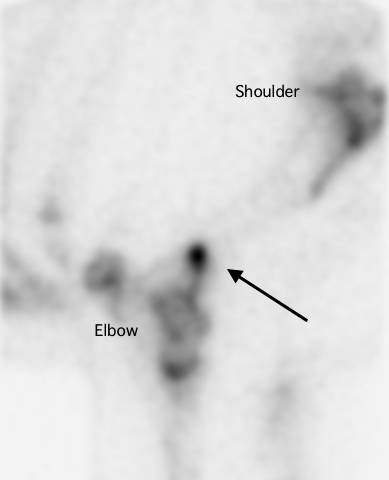

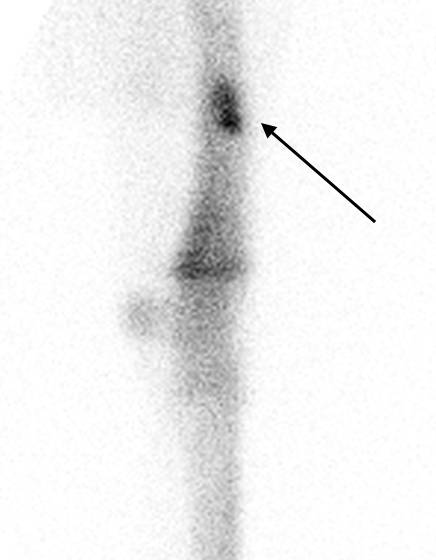

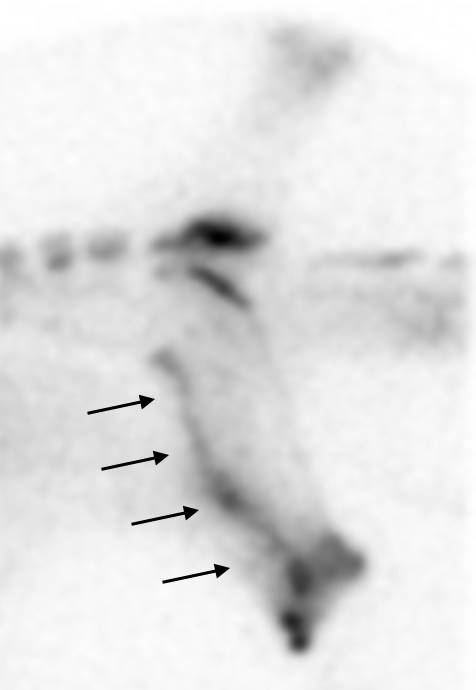

PET is the most recent advance in diagnostic imaging. It is being developed in California and, when combined with CT, provides information on bone activity and structure. In these three images of the same fetlock, from different aspects, the orange spots indicate increased activity in the proximal sesamoid bone, which is a potential precursor to more serious injury.

Image courtesy of Dr M. Spriet, University of California, Davis.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

Antimicrobial resistance

By Jennifer Davis and Celia Marr

Using antimicrobials as effectively as possible helps to reduce their use overall. For septic arthritis, intravenous regional perfusion of antimicrobials can achieve very high concentrations within a specific limb. This involves placing a temporary tourniquet to reduce blood flow away from the area while the antimicrobial is injected into a nearby blood vessels. The technique is suitable for some but not all antimicrobial drugs.

Growing numbers of bacterial and viral infections are resistant to antimicrobial drugs, but no new classes of antibiotics have come on the market for more than 25 years. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria cause at least 700,000 human deaths per year according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Equivalent figures for horses are not available, but where once equine vets would have very rarely encountered antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, in recent years this serious problem is a weekly, if not daily, challenge.

The WHO has for several years now, designated a World Antibiotic Awareness Week each November and joining this effort, British Equine Veterinary Association and its Equine Veterinary Journal put together a group of articles exploring this problem in horses.

How do bacterial populations develop resistance?

Certain types of bacteria are naturally resistant to specific antimicrobials and susceptible to others. Bacteria can develop resistance to antimicrobials in three ways: bacteria, viruses and other microbes, which can develop resistance through genetic mutations or by one species acquiring resistance from another. Widespread antibiotic use has made more bacteria resistant through evolutionary pressure—the “survival of the fittest” principle means that every time antimicrobials are used, susceptible microbes may be killed; but there is a chance that a resistant strain survives the exposure and continues to live and expand. The more antimicrobials are used, the more pressure there is for resistance to develop.

The veterinary field remains a relatively minor contributor to the development of antimicrobial resistance. However, the risk of antimicrobial-resistant determinants travelling between bacteria, animals and humans through the food chain, direct contact and environmental contamination has made the issue of judicious antimicrobial use in the veterinary field important for safeguarding human health. Putting that aside, it is also critical for equine vets, owners and trainers to recognise we need to take action now to limit the increase of antimicrobials directly relevant to horse health.

How does antimicrobial resistance impact horse health?

This mare’s problems began with colic; she underwent surgery to correct a colon torsion (twisted gut). When the gut wall is damaged, bacteria easily spread throughout the body. The mare developed an infection in her surgical incision and in her jugular veins, progressing eventually to uncontrollable infection—resistant to all available antimicrobials with infection of the heart and lungs.

The most significant threat to both human and equine populations is multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli, MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium, and rising MDR strains of Salmonella spp. and Clostridium difficile. In an analysis of 12,695 antibiograms collected from horses in France between 2012-2016, the highest proportion (22.5%) of MDR isolates were S. aureus. Identification of ESBL E.coli strains that are resistant to all available antimicrobial classes has increased markedly in horses. In a sampling of healthy adult horses at 41 premises in France in 2015, 44% of the horses shed MDR E.coli, and 29% of premises shedding ESBL isolates were found in one third of the equestrian premises. Resistant E. coli strains are also being found in post-surgical patients with increasing frequency.

Rhodococcus equi is a major cause of illness in young foals. It leads to pneumonia and lung abscesses, which in this example have spread through the entire lung. Research from Kentucky shows that antimicrobial resistance is increasingly common in this bacterial species.

Of major concern to stud owners, antimicrobial-resistant strains of Rhodococcus equi have been identified in Kentucky in the last decade, and this bacteria can cause devastating pneumonia in foals. Foals that are affected by the resistant strains are unlikely to survive the illness. One of the leading authorities on R equi pneumonia, Dr Monica Venner has published several studies showing that foals can recover from small pulmonary abscesses just as quickly without antibiotics, and has pioneered an ‘identify and monitor’ approach rather than ‘identify and treat’. Venner encourages vets to use ultrasonography to quantify the infected areas within the lung and to use repeat scans, careful clinical monitoring and laboratory tests to monitor recovery. Antimicrobials are still used in foals, which are more severely affected, but this targeted approach helps minimise drug use.

What can we do to reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance?

Faced with a coughing horse, trainers will often pressure their vet to administer antibiotics, hoping this will clear the problem up quickly. Many respiratory cases will recover without antibiotics, given rest and good ventilation.

The simple answer is stop using antimicrobials in most circumstances except where this is absolutely avoidable. In training yards, antimicrobials are being over-used for coughing horses. Many cases are due to viral infection, for which antibiotics will have little effect. There is also a tendency for trainers to reach for antibiotics rather than focusing on improving air quality and reducing exposure to dust. Many coughing horses will recover without antibiotics, given time. Although it has not yet been evaluated scientifically, adopting the ‘identify and monitor’ approach, which is very successful in younger foals, might well translate to horses in training in order to reduce overuse of antimicrobials.

Vets are also encouraged to choose antibiotics more carefully, using laboratory results to select the drug which will target specific bacteria most effectively. The World Health Organization has identified five classes of antimicrobials as being critically important, and therefore reserved, antimicrobials in human medicine. The critically important antimicrobials which are used in horses are the cephalosporins (e.g., ceftiofur) and quinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin), and the macrolides, which are mainly used in foals for Rhodococcal pneumonia. WHO and other policymakers and opinion leaders have been urging vets and animal owners to reduce their use of critically important antimicrobials for well over a decade now. Critically important antimicrobials should only be used where there is no alternative, where the disease being treated has serious consequences and where there is laboratory evidence to back up the selection. British Equine Veterinary Association has produced helpful guidelines and a toolkit, PROTECT-ME, to help equine vets achieve this.

How well are we addressing this problem?….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Ulcer medication: are the products to treat that different?

By Celia Marr

Stomach ulcers are not all the same

Racehorse trainers and their vets first began to be aware of stomach ulcers over 20 years ago. The reasons why we became aware of ulcers are related to technological advances, which produced endoscopes long enough to get into the equine stomach. At that time, scopes were typically about 2.5m long and were most effective in examining the upper area of the stomach, which is called the squamous portion. Once this technology became available, it was quickly appreciated that it is very common for racehorses to have ulcers in the squamous portion of the stomach.

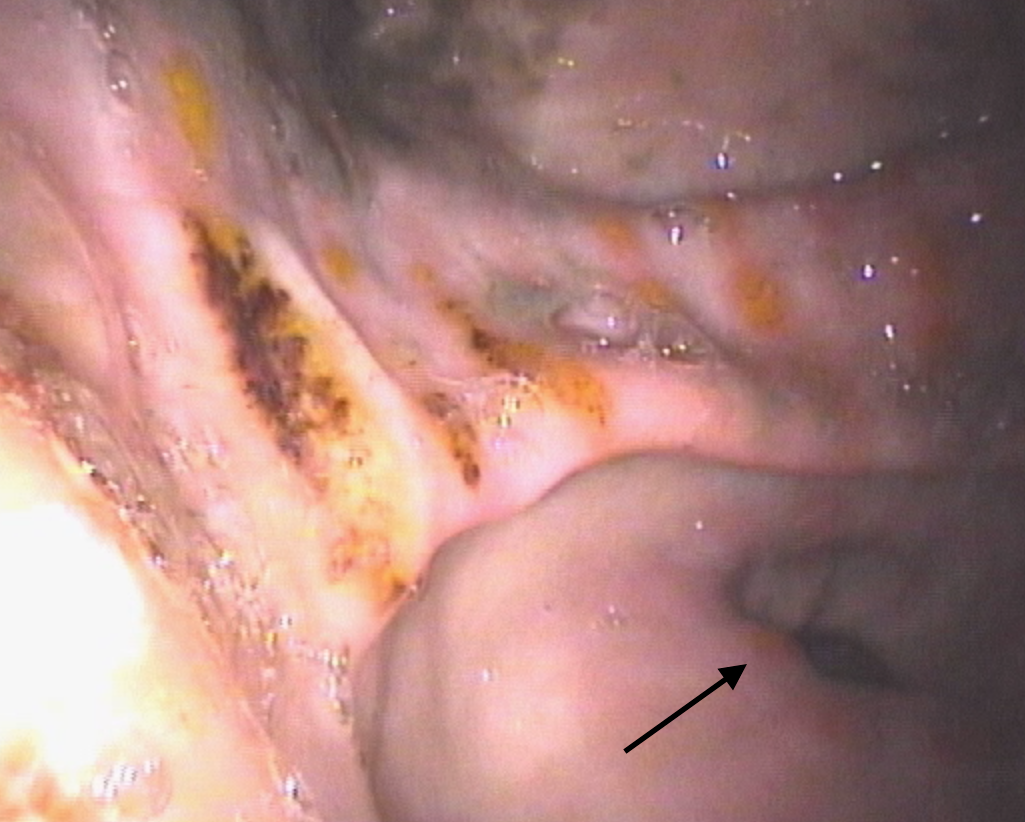

Fig 1. The equine stomach has two regions: the upper region is the squamous portion and the lower region is the glandular portion. The squamous portion is lined by pale pink tissue which is susceptible to acid damage. The glandular portion is lined by darker purple tissue. Acid is produced in this region. In this horse, the stomach lining is healthy and unblemished. The froth is due to saliva which is continuously swallowed.

The equine stomach has two main areas: the squamous portion and the glandular portion. The stomach sits more or less in the middle of the horse, immediately behind the diaphragm and in front of and above the large colon. Imagine the stomach as a large balloon with the oesophagus—the gullet—entering halfway up the front side and slightly to the left of the balloon-shaped stomach and the exit point also coming out the front side but slightly lower and to the right side. The tissue around the exit—the pylorus—and the lower one-third, the glandular portion, has a completely different lining to the top two-thirds, the squamous portion.

The stomach produces acid to start the digestive process. Ulceration of the squamous portion is caused by this acid. Like the human oesophagus, the lining of the squamous portion has very limited defences against acid. But, the acid is actually produced in the lower, glandular portion. The position of the stomach is between the diaphragm, which moves backwards as the horse breathes in and the heavy large intestine which tends to push forwards as the horse moves. During exercise, liquid acid produced at the bottom of the stomach is squeezed upwards onto the vulnerable squamous lining. It makes sense then that the medications used to treat squamous ulcers are aimed at blocking acid production.

Lesions in the glandular portion of the stomach are less common than squamous ulcers. The acid-producing glandular portion has natural defences against acid damage including a layer of mucus and local production of buffering compounds. At this point, we actually know relatively little about the causes of glandular disease, but it is becoming increasingly obvious that disease in the glandular portion is very different from squamous disease. Often, it is more difficult to treat.

Fig 2. This horse shows signs of discomfort. She carries her head low, her ears are back a little, and the muscles of the face are clenched, affecting the shape of the nostrils and eye.

Stomach ulcers can cause a wide range of clinical signs. Some horses seem relatively unaffected by fairly severe ulcers, but other horses will often been off their feed, lose weight, and have poor coat quality. Some will show signs of abdominal discomfort, particularly shortly after eating. Other horses may be irritable—they can grind their teeth or they may resent being girthed. Additional signs of pain include an anxious facial expression, with ears back and clenching of the jaw and facial muscles and a tendency to stand with their head carried a little low.

Assessing ulcers

Ulcers can only be diagnosed with endoscopy. A grading system has been established for squamous ulcers, which is useful in making an initial assessment and in documenting response to treatment.

Grade 0 = normal intact squamous lining

Grade 1 = mild patches of reddening

Grade 2 = small single or multiple ulcers

Grade 3 = large single or multiple ulcers

Grade 4 = extensive, often merging with areas of deep ulceration

Fig 3. Grade 1 squamous ulcers which are mild patches of reddening.

Fig 4. Grade 2 squamous ulcers—there are several of these, but they are all small.

Fig 5. Grade 3 squamous ulcers—these are larger, and there are several.

Fig 6. Grade 4 squamous ulcers—there are extensive deep ulcers with active haemorrhage.

Although it is used for research purposes, this grading system does not translate very well to glandular ulcers where typically, lesions are described in terms of their severity (mild, moderate or severe), distribution (focal, multifocal or diffuse), thickness (flat, depressed, raised or nodular) and appearance (reddening, haemorrhagic or fibrinosuppurative). Fibrinosuppurative suggests that inflammatory cells or pus has formed in the area. Focal reddening can be quite common in the absence of any clinical signs. Nodular and fibrinosuppurative lesions may be more difficult to treat than flat or reddened lesions. Where the significance of lesions is questionable, it can be helpful to treat the ulcers and repeat the endoscopic examination to determine whether the clinical signs resolve along with the ulcers.

Fig 7. The glandular tissue around the pylorus (or exit point) has reddened patches. This is of questionable clinical relevance, and many horses will show no signs associated with these lesions.

Fig 8. There are dark red patches of haemorrhage in the glandular tissue of the antrum—the region adjacent to the pylorus—which is the dark hole toward the bottom of this image.

Fig 9.This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. There are depressed suppurative (yellow) areas several of which also have haemorrhage. Nearer to the pylorus there is reddening and raised, swollen areas (arrow).

Fig 10. This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. The majority of lesions are depressed and haemorrhagic.

Medications for squamous ulcers

Because of the prevalence and importance of gastric ulcers, Equine Veterinary Journal publishes numerous research articles seeking to optimise treatment. The most commonly used drug for treatment of squamous ulcers is omeprazole. A key feature of products for horses is that the drug must be buffered in order to reach the small intestine, from where it is absorbed into the bloodstream in order to be effective. Until recently only one brand was available, but there are now several preparations on the market and researchers have been seeking to show whether new medicines are as effective as the original brand. There is limited information comparing the new products, and this information is essential to determine whether the new, and often cheaper, products should be used.

A team of researchers formed from Charles Sturt University in Australia and Louisiana State University in the US has compared two omeprazole products given orally. A study reported by Dr Raidal and her colleagues, showed that not only were plasma concentrations of omeprazole similar with both products, but importantly, the research also showed that gastric pH was similar with both products and both products reduced summed squamous ulcer scores. Both the products tested in this trial are available in Australia and, although products on the market in UK have been shown to achieve similar plasma concentrations and it is therefore reasonable to assume that they will be beneficial, as yet, not all of them have been tested to show whether products are equally effective in reducing ulcer scores in large-scale clinical trials. Trainers should discuss this issue with their vets when deciding which specific ulcer product they plan to use in their horses.

Avoiding drugs altogether and replacing this with a natural remedy is appealing. There is a plethora of nutraceuticals around and anecdotally, horse owners believe they may be effective. One such option is aloe vera that has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and mucus stimulatory effects which might be beneficial in a horse’s stomach. Another research group from Australia, this time based in Adelaide, has looked at the effectiveness of aloe vera in treating squamous ulcers and found that, although 56% of horses treated with aloe vera improved and 17% resolved after 28 days, this compared to 85% improvement and 75% resolution in horses given omeprazole. Therefore, Dr Bush and her colleagues from Adelaide concluded treatment with aloe vera was inferior to treatment with omeprazole.

Medications for glandular ulcers….

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Wobbler Syndrome and the thoroughbred

By Celia M Marr, Rossdales Equine Hospital and Diagnostic Centre

Wobbler Syndrome, or spinal ataxia, affects around 2% of young thoroughbreds. In Europe, the most common cause relates to narrowing of the cervical vertebral canal in combination with malformation of the cervical vertebrae. Narrowing in medical terminology is “stenosis” and “myelopathy” implies pathology of the nervous tissue, hence the other name often used for this condition is cervical vertebral stenotic myelopathy (CVSM).

Wobbler Syndrome was the topic of this summer’s Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, an event held at Palace House, Newmarket. Gerald Leigh was a very successful owner breeder and these annual lectures, now in their second year, honour of Mr Leigh's passion for the thoroughbred horse and its health and welfare. The lectures are attended by vets, breeders and trainers, and this year because of the importance and impact of Wobbler syndrome on thoroughbred health, several individuals involved in thoroughbred insurance were also able to participate.

Blindfolding the horse, exacerbates the ataxia and improves the accuracy of objective ataxia assessment.

Dr Steve Reed, of Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital, Kentucky and international leader in the field of equine neurology gave an overview of Wobbler Syndrome. Affected horses are ataxic, which means that they have lost the unconscious mechanisms which control their limb position and movement. Young horses with CVSM will generally present for acute onset of ataxia or gait abnormalities, however, mild ataxia and clumsiness may often go unnoticed. Trainers often report affected horses are growing rapidly, well-fed, and large for their age. It is common for riders to describe an ataxic horse as weak or clumsy. Sometimes, a horse which has been training normally will suddenly become profoundly affected, losing coordination and walking as though they were drunk, or in the most severe cases stumbling and falling. Neurological deficits are present in all four limbs, but are usually, but not always more noticeable in the hindlimbs than the forelimbs. In horses with significant degenerative joint disease, lateral compression of the spinal cord may lead to asymmetry of the clinical signs.

When the horse is standing still, it may adopt an abnormal wide-based stance or have abnormal limb placement, and delayed positioning reflexes. At the walk, the CVSM horse’s forelimbs and hindlimbs may not be moving on the same track and there can be exaggerated movement of the hind limbs when the horse is circled. Detailed physical examination may reveal abrasions around the heels and inner aspect of the forelimbs due to interference, and short, squared hooves due to toe-dragging. Many young horses affected with CVSM have concurrent signs of developmental orthopaedic disease such as physitis or physeal enlargement of the long bones, joint effusion secondary to osteochondrosis, and flexural limb deformities.

Radiography is generally the first tool which is used to diagnose CVSM. Lateral radiographs of the cervical vertebrae, obtained in the standing horse, reveal some or all of five characteristic bony malformations of the cervical vertebrae: (1) “flare” of the caudal vertebral epiphysis of the vertebral body, (2) abnormal ossification of the articular processes, (3) malalignment between adjacent vertebrae, (4) extension of the dorsal laminae, and (5) degenerative joint disease of the articular processes. Radiographs are also measured to document the ratio between the spinal canal and the adjacent bones and identify sites where the spinal canal is narrowed.

ABOVE L–R: Lateral radiographs can show the vertebral bones have an abnormal shape with flare of the caudal vertebral epiphysis (curved arrow) and extension of the dorsal laminae (straight arrow). Abnormal ossification of the articular processes and enlargement of the joints due to degenerative joint disease (arrows). Measuring the ratio of the spinal canal to the adjacent bone identifies narrowing of the spinal canal. In this case, the narrowing is dramatic due to mal-alignment of adjacent vertebral bones.

Dr Reed also highlighted myelography as the currently most definitive tool to confirm diagnosis of focal spinal cord compression and to identify the location and number of lesions. The experts presenting at the Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures agreed that myelography is essential if surgical treatment is pursued. However, an important difference between the US and Europe was highlighted by Prof Richard Piercy, of the Royal Veterinary College, University of London. In Europe, protozoal infection is very rare, whereas in US, equine protozoal myeloencephalitis can cause similar clinical signs to CVSM. Protozoal myeloencephalitis is diagnosed by laboratory testing of the cerebral spinal fluid but there is also a need to rule out CVSM. Therefore, spinal fluid analysis and myelography tends to be performed more often in the US. Prof Piercy pointed out that in the absence of this condition, vets in Europe are often more confident to reach a definitive diagnosis of CVSM based on clinical signs and standing lateral radiographs.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Osteochondrosis: genetic causes and early diagnosis

By Prof. Celia M Marr

Osteochondrosis (OC) is a common lesion in young horses affecting the growing cartilage of the articular/epiphyseal complex of predisposed joints at specific predilection sites. In the young thoroughbred, it commonly affects the stifles, hocks, and fetlocks. As this condition has such important impact on soundness across many horse breeds, it is commonly discussed in Equine Veterinary Journal. Four recent articles covered causes of the disease, its genetic aspects, and a new and very practical approach to early diagnosis through ultrasound screening programmes on stud farms.

OC is a disease of joint cartilage. Cartilage covers the ends of bones in joints, and healthy cartilage is central to unrestricted joint movement. With OC, abnormal cartilage can be thickened, collapsed, or progress to cartilage flaps or osteochondral fragments separated from the subchondral bone leading to osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD). OC and OCD can be regarded as a spectrum rather than two discrete conditions.

Certain joints are prone to OC & OCD, and there is some variation between breeds on which joints have the highest prevalence. In Australian thoroughbreds, 10% of yearlings had stifle OC, 8% had fetlock OC, and 6% had hock OC. The prevalence data may seem very high, but thoroughbred breeders may take some comfort in learning that similar, and indeed slightly higher prevalences, are reported in the warmblood breeds, standardbreds, and Scandinavian and French trotters. Heavy horse breeds have the highest prevalences.

In an article discussing progress in OC/OCD research, Professor Rene Van Weeren concludes that the clinical relevance of OC is man made. In feral horses, where there is no human influence on mating pairings, OC does occur but at much lower prevalence than in horse breeds selected for sports or racing. Similarly, in pony breeds where factors other than speed and size are desirable characteristics, OC is also rare. These facts suggest that sports and racehorse breeders have inadvertently introduced a trait for OC along with other, desired traits. There is a strong link between height and OC, suggesting that one of the desired traits with unintended consequences is height. This is of particular relevance in sports horses: the Dutch warmblood has become taller at a rate of approximately 1 mm per year over the past decades, which might not seem much but it is still an inch in 25 years. Van Weeren points out that if the two-hands tall Eohippus or Hyracotherium, the browsing forest-dweller with which equine evolution started some 65 millions of years ago, had evolved at this speed, the average horse would now have stood a staggering 40 miles at the withers.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

The On-going Effort to Minimise the Rate and Impact of Fractures

Published in European Trainer, January - March 2018, issue 60.

In thoroughbred racing, musculoskeletal injury is a major safety concern and is the leading reason for days lost to training. Musculoskeletal injury is the greatest reason for horse turnover in racing stables, with financial implications for the owner and the racing industry. Injuries, particularly on race day, have an impact on public perception of racing.

Upper limb and pelvis fractures are less common than lower limb fractures, but they can lead to fatalities. Reducing the overall prevalence of fractures is critical and, at the very least, improving the rate of detection of fractures in their early stages so the horse can be withdrawn from racing with a recoverable injury will be a big step forwards in racehorse welfare. Currently, we lack information on the outcomes following fracture, and an article recently published in the Equine Veterinary Journal (EVJ) from the veterinary team at the Hong Kong Jockey Club (HKJC) addressed this important knowledge gap.

Hong Kong Fracture Outcome Study

The HKJC veterinary team is in a unique position to carry out this work because their centralised and computerised database of clinical records, together with racing and retirement records, allows them to document follow-up, which is all but impossible elsewhere in the world. Dr Leah McGlinchey, working with vets in Hong Kong and researchers from the Royal Veterinary College, London, reviewed clinical records from 2003 to 2014 to identify racehorses that suffered a fracture or fractures to the bones of the upper limb or the pelvis during training or racing, confirmed by nuclear scintigraphy, radiography, ultrasonography, or autopsy....

To read more - subscribe now!

Gallery

Diagnosis of laryngeal problems: hocus pocus or cutting edge science?

CLICK ON THE IMAGE ABOVE TO BUY THIS BACK ISSUE NOW!

First published in European Trainer issue 57 - April '17 - June '17