The importance of stable ventilation

By Alan Creighton

Over the past 20 years the Irish Equine Centre has become world leaders in the design and control of the racehorse stable environment. At present we monitor the stable environment of approximately 180 racing yards across Europe.

The basis of our work is to improve biosecurity and the general environment in relation to stable and exercise areas within racing establishments. This is achieved by improving ventilation, yard layout, exercise areas and disinfection routines, in addition to testing of feed, fodder and bedding for quality and reviewing how and where they are stored.

Racehorses can spend up to 23 hours per day standing in their stable. The equine respiratory system is built for transferring large volumes of air in and out of the lungs during exercise. Racehorses are elite athletes, and best performance can only be achieved with optimal health. Given the demanding life of the equine athlete, a high number of racehorses are at risk of several different respiratory concerns. The importance of respiratory health greatly increases in line with the racehorse’s stamina. Therefore, as the distance a racehorse is asked to race increases so does the importance of ventilation and fresh clean air.

Pathogenic fungi and bacteria, when present in large numbers, can greatly affect the respiratory system of a horse and therefore performance. Airborne dust and pathogens, which can be present in any harvested food, bedding, damp storage areas and stables, are one of the main causes of RAO (Recurrent Airway Obstruction), EIPH (Exercise Induced Pulmonary Haemorrhage, also known as bleeding), IAD (irritable airway disease) and immune suppression. All of which can greatly affect the performance of the racehorse. Yards, which are contaminated with a pathogen of this kind, will suffer from the direct respiratory effect but will also suffer from recurring bouts of secondary bacterial and viral infections due to the immune suppression. Until the pathogen is found and removed, achieving consistency of performance is very difficult. Stable ventilation plays a huge part in the removal of these airborne pathogens.

What is ventilation?

The objective of ventilation is to provide a constant supply of fresh air to the horse. Ventilation is achieved by simply providing sufficient openings in the stable/building so that fresh air can enter and stale air will exit.

Ventilation involves two simple processes:

Air exchange where stale air is replaced with fresh air.

Air distribution where fresh air is available throughout the stable.

Good stable ventilation provides both of these processes. One without the other does not provide adequate ventilation. For example, it is not good enough to let fresh air into the stable through an open door at one end of the building if that fresh air is not distributed throughout the stable and not allowed to exit again. With stable ventilation we want cold air to enter the stable, be tempered by the hot air present, and then replace that hot air by thermal buoyancy. As the hot air leaves the stable, we want it to take moisture, dust, heat, pathogens and ammonia out as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 2

It is important not to confuse ventilation with draft. We do not want cold air blowing directly at the horse who now has nowhere to shelter. Proper ventilation, is a combination of permanent and controllable ventilation. Permanent ventilation apart from the stable door should always be above the horse’s head. It is really important to have a ridge vent or cowl vent at the very highest point of the roof. Permanent ventilation should be a combination of air inlets above the horse’s head, which allows for intake of air no matter which direction the wind is coming from, coupled with an outlet in the highest point of the roof (shown in Figure 2). The ridge vent or cowl vent is an opening that allows warm and moist air, which accumulates near the roof peak to escape. The ridge opening is also a very effective mechanism for wind-driven air exchange since wind moves faster higher off the ground. The controllable ventilation such as the door, windows and louvers are at the horse height. With controllable ventilation you can open it up during hot spells or close it down during cold weather. The controllable ventilation should be practical and easy to operate as racing yards are very busy places with limited time.

Where did the design go wrong?

The yards we work in are a mixture of historic older yards, yards built in the mid to late 20th century and yards built in the early 21st century. The level of ventilation present was extremely varied in a lot of these yards prior to working with the Irish Equine Centre. Interestingly the majority of the yards built before World War I displayed extremely efficient ventilation systems. Some of the oldest yards in the Curragh and Newmarket are still, to this day, considered well ventilated.

In parts of mainland Europe including France the picture is very different. In general, the older yards in France are very poorly ventilated. The emphasis in the design of yards in parts of France appears to be more focused on keeping animals warm in the winter and cool during the summer. This is understandable as they do get colder winters and warmer summers in the Paris area, for example, when compared to the more temperate climate in Ireland and the UK. When these yards were built they didn’t have the quality of rugs available that we do now. Most of the yards in France are built in courtyard style with lofts above for storage and accommodation. When courtyard stables are poorly ventilated with no back or side wall air vents, you will always have the situation that the only boxes that get air exchange are the ones facing into the prevailing wind at that time. In this scenario, up to 60% of the yard may have no air exchange at all.

In the mid to late 20th century efficient ventilation design appears to have been overlooked completely. There appears to be no definitive reason for this phenomenon, with planning restrictions, site restrictions in towns like Newmarket and Chantilly, cheaper builds, or builders building to residential specifications all contributing to inadequate ventilation.

Barn and stable designers did not, and in a lot of cases still don’t, realize how much air exchange is needed for race horses. Many horse owners and architects of barns tend to follow residential housing patterns, placing more importance on aesthetics instead of what’s practical and healthy for the horse.

Many horses are being kept in suburban settings because their owners are unfamiliar with the benefits of ventilation on performance. Many of these horses spend long periods of time in their stalls, rather than in an open fresh-air environment that is conducive to maximum horse health. We measure stable ventilation in air changes per hour (ACH). This is calculated using the following simple equation:

Air changes per hour AC/H

N = 60 Q

Vol

N = ACH (Air change/hour)

Where: Q = Velocity flow rate (wind x opening areas in cfm)

Vol = Length x Width x Average roof height.

Minimum air change per hour in a well-ventilated box is 6AC/H. We often measure the ACH in poorly ventilated stables and barns with results as low as 1AC/H; an example of such a stable environment is shown in Figure 3. When this measurement is as low as 1AC/H we know that the ventilation is not adequate. There will be dust and grime build up, in addition to moisture build up resulting in increased growth of mould and bacteria, and there will be ammonia build up. The horse, who can be stabled for up to 23 hours of the day, now has no choice but to breathe in poor quality air. Some horses such as sprinters may tolerate this, but in general it will lead to multiple respiratory issues…

BUY IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Colic - effects of inflammation

By Dr Zofia Lisowski, Prof. Scott Pirie & Dr Neil Hudson

Overview of colic

Colic is a term used to describe the display of abdominal pain in the horse. It is the most common emergency in horses with four to ten out of every 100 horses likely to experience at least one episode of colic each year. It is also the single most common cause of equine mortality. In the US, one study showed that thoroughbreds were more likely to develop colic1 than other breeds. It is of great welfare concern to horse owners, and with the estimated costs associated with colic in the US exceeding $115 million dollars per year2 and the average cost of a horse undergoing colic surgery that requires a resection in the UK being £6437.803, it is also a significant economic issue for horse owners.

Horses with abdominal pain show a wide range of clinical signs, ranging from flank watching and pawing the ground in mild cases, to rolling and being unable to remain standing for any significant period of time in more severe cases. There are numerous (over 50) specific causes of colic. In general, colic occurs as a result of disruption to the normal function of the gastrointestinal tract. This may be attributable to mechanical causes such as an obstruction (constipation), distension (excess gas) or a volvulus (twisted gut). It may also have a functional cause, whereby the intestine doesn’t work as normal in the absence of an associated mechanical problem; for example, equine grass sickness is associated with a functional derangement of intestinal motility due to loss of nerves within the intestine.

Management of colic depends on the cause and can necessitate either a medical or surgical approach. Most horses with colic will either improve spontaneously or with simple medical treatment alone; however, a significant proportion may need more intensive medical treatment or surgery. Fortunately, due to improvements in surgical techniques and post-operative management, outcomes of colic surgery have improved over the past few decades with up to 85% of horses surviving to discharge. Crucially for the equine thoroughbred racehorse population, several studies focussed on racehorses that had undergone colic surgery and survived to discharge, reporting that 63-73% returned to racing. Furthermore, surgical treatment did not appear to negatively impact athletic performance. A similar finding was also seen in the general sport horse population.

Despite significant advancement in colic surgery per se, complications following surgery can have a significant impact on post-operative survival and return to athletic function. Common post-operative complications include:

Complications at the site of the incision (surgical wound)

Infection: Infections at the site of the surgical incision are relatively common. Antibiotics are usually administered before surgery and after surgery. Infections are not normally severe but can increase treatment costs. Horses that develop infections are at greater risk of developing an incisional hernia.

Hernia: Incisional hernias occur when the abdominal wall muscles fail to heal leaving a ‘gap’. Hernia size can vary from just a few centimetres, up to the full length of the incision. Most hernias will not require further treatment, but in more severe cases, further surgery may be required to repair the hernia.

Complications within the abdomen

Haemoperitoneum: A rare complication where there is blood within the abdomen from bleeding at the surgical site.

Anastomosis complications: The anastomosis site is where two opposing ends of intestine that have been opened are sutured back together again. It is important that at this site no leakage of intestinal contents occurs. Leakage or breakdown at this site can lead to peritonitis, which is inflammation or infection within the abdominal cavity and is a potentially life threatening complication.

Adhesions: Scar tissue can form within the abdomen following abdominal surgery. Occasionally this may cause further colic episodes

Further colic episodes

Further colic episodes can occur following surgery. These can occur days to months following discharge.

Endotoxaemia

In some rare cases, horses may develop sepsis in response to toxins released by damaged intestine

Diarrhoea

This is a rare complication. It can develop as a result of infections with C. difficile or Salmonella. As a consequence, some horses may need to be treated in isolation to ensure infection doesn’t spread to other horses or humans.

Post-operative ileus

Post-operative ileus is one of the potential post-operative complications which can lead to a significant increase in hospital stay duration, increased treatment costs and is also associated with reduced survival rates. Post-operative ileus is a condition that affects the muscle function in the intestinal wall. The intestine is a long tube-like structure that has a muscular wall throughout its entire length from the oesophagus to the anus. The function of this muscle is to contract in waves to mix and move food along the length of the intestinal tract, within which digestion occurs and nutrients are absorbed, terminating in the excretion of waste material as faeces. In post-operative ileus these contractions stop and thus intestinal contents are not moved throughout the intestinal tract. In most cases, it is transient and lasts for up to 48 hours following surgery; however, in some cases it can last longer. A build-up of fluid develops within the intestine as a result of the lack of propulsion. This stretches the intestines and stomach, resulting in pain and the horse’s inability to eat. Unlike humans, the horse is unable to vomit; consequently, this excess fluid must be removed from the stomach by other means, otherwise there is a risk of the stomach rupturing with fatal consequences. Post-operative ileus may occur in up to 60% of horses undergoing abdominal surgery and mortality rates as high as 86% have been reported. Horses in which the small intestine manipulated is extensively manipulated during surgery and those that require removal of segments of intestine are at higher risk. Despite the significant risk of post-operative ileus following colic surgery in horses, there is a lack of studies investigating the mechanisms underpinning this condition in horses; consequently, the precise cause of this condition in horses is not fully known.

What causes the intestine to stop functioning?

For many years it was thought that post-operative ileus occurred as a result of a dysfunction of the nerves that stimulate contraction of the muscles in the intestinal wall. This theory has now mostly been superseded by the concept that it primarily results from inflammation in the intestinal wall. Based on human and rodent studies, it has been shown that immune cells in the intestine (macrophages) play a key role in development of this condition. Macrophages are important cells found everywhere in the body, with the largest population being in the intestine. These cells become activated by the inevitable manipulation of the horses’ intestines during colic surgery, with subsequent initiation of a sequence of events which ultimately results in dysfunction of the muscle in the intestinal wall. We know macrophages are present within the wall of the horses’ intestine and that at the time of colic surgery there is an inflammatory response at this site. Although the significance of these findings in relation to post-operative ileus in the horse remains unknown, they provide sufficient justification for ongoing research focused on the inflammatory response in the intestine of horses during and immediately following colic surgery…

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

How technology can quantify the impact saddles have on performance

By Dr. Russell Mackechnie-Guire

Thanks to advances in technology, it is getting easier for scientists to study horses in a training environment. This, combined with recent saddlery developments in other disciplines, is leading to significant progress in the design and fit of exercise saddles.

Back pain, muscle tension and atrophy are common issues in yards. Although there are many contributory factors, the saddle is often blamed as a potential cause. Unlike other equestrian sports, where the effect of tack and equipment on the horse has been investigated, until now there has been little evidence quantifying the influence of exercise saddles.

New era

The technological advances used in sport horse research are sparking a new era in racing, enhancing our understanding of the physiological and biomechanical demands on the horse, and helping improve longevity and welfare. For the trainer this translates into evidence-based knowledge that will result in marginal or, in some cases, major gains in terms of a horse’s ability to race and achieve results. Race research has always been problematic, not least due to the speed at which the horse travels. Studies have previously been carried out in gait laboratories on treadmills, but this is not representative of normal terrain or movement. Thanks to new measuring techniques, we can now study the horse in motion on the gallops. Evidence of this new era arises from a recent study published in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. It found areas of high pressures under commonly used exercise saddles which had a negative influence on back function, affecting the horse’s gallop and consequently performance.

The pressure’s on

Researchers used a combination of pressure mapping and gait analysis (see Technology in focus panel) to investigate three designs of commonly used exercise saddles: full tree, half tree and three-quarter tree. The aim was to identify pressure magnitude and distribution under each of the saddles then to establish whether the gait (gallop) was improved in a fourth saddle designed to remove these pressures.

Areas of high pressure were found in the region of the 10th-13th thoracic vertebrae (T10-T13). Contrary to popular belief, none of the race exercise saddles tested in this study produced peak pressure on or around the scapula. The pressures around T10-T13 at gallop in the half, three-quarter and full tree were in excess of those detected during jumping or dressage in sport horses. They were also higher than pressures reported to be associated with clinical signs of back pain. Therefore, it is widely accepted that high pressures caused by the saddle could be a contributory factor to back pain in horses in training.

Three most commonly used saddle-tree lengths, plus the new design (purple 40cm)

Half tree: High peak pressures in the region of T10-T14 were consistent with the end of the tree.

Three-quarter tree: Peak pressure was localised on one side of the back at a time, depending on the horse’s gallop lead.

Full tree: Peak pressure was further back and, although not high, gait analysis demonstrated a reduction in the extent to which the hindlimb comes under the horse, reducing the power in the stride.

New design: A more uniform pressure distribution, recording the lowest peak pressures at each location.

Lower pressure leads to longer strides

When looking at propulsion, there are two important measurements: the angle of the femur relative to the vertical and hip flexion. When pressures were reduced beneath the saddle, researchers saw an increased femur-to-vertical angle in the hindlimb and a smaller hip flexion angle (denoting the hip is more flexed).

A greater femur-to-vertical angle indicates that the hindlimb is being brought forward more as the horse gallops.

A smaller hip flexion angle denotes the hip is more flexed, allowing the horse to bring his quarters further under him and generate increased power.

Improved hip flexion was recorded in the new saddle design (A) compared to a commonly used saddle (B).

When pressure is reduced in the region of T13, the hindlimb is allowed to come more horizontally under the horse at this point in the stride, leading to an increase in stride length. Researchers speculate that this could be due to the fact that the thorax is better able to flex when pressure is reduced.

Perhaps surprisingly, the study found that reducing saddle pressures did not result in any significant alteration in the forelimb at gallop. The major differences were recorded in hindlimb function. This could be explained anatomically; the forelimb is viewed as a passive strut during locomotion, whereas the hindlimbs are responsible for force production.

This is consistent with findings in the sport horse world, where extensive research investigating pressures in the region of the 10th-13th thoracic vertebrae has shown that reducing saddle pressure is associated with improved gait features in both dressage and jumping.

Speed matters…

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

No guts, no glory!

By Catherine Rudenko

Can we increase the efficiency of the digestive system through dietary and supplementary manipulation in order to alter performance and recovery?

The idiom ‘no guts, no glory’, when taken in the literal sense, is quite an appropriate thought for the racehorse. The equine gut is a collection of organs, which when in a state of disease, causes a multitude of problems; and when functioning effectively, it is key for conversion of food to fuel and maintaining normal health.

In the same way we consider how fuel-efficient our car engines are, what power can be delivered and the influence of fuel quality on function, we can consider the horses’ digestive anatomy. The state of the ‘engine’ in the horse is critical to the output. What is fed or supplemented, and the manner in which we do so, has fascinating and somewhat frightening effects on efficiency and recovery.

We now, in a human context, have a much better understanding of the relationship between the gut and states of disease. Before disease in a notable sense is present, we see loss of function and reduction in performance. With equines, in recent years, the focus has fallen toward ulceration and the stomach. Now interest is growing into the small and large intestines, looking at factors that influence their performance and in turn how this affects performance on the track.

In order to consider how we can positively influence gut function, first we need to understand its design and capability, or lack of capability which is more often the problem. The horse, by definition, falls into the category of a large non ruminant herbivore—the same grouping as rhinoceroses, gorillas and elephants. The horse is well designed for a fibre-based diet, as reflected by the capacity of the large intestines, yet we must rely heavily on the small intestine when feeding racehorses. Health and function of both small and large intestines are important and are connected.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is a relatively short tube of approximately 25m in length—the same length as found in sheep or goats. The primary role of the small intestine is the digestion of protein, fats and carbohydrates. The workload of this organ is significant and is also time constrained, with feed typically moving at a rate of 30cm per minute (1). The rate of passage is highly influenced by whether the stomach was empty before feeding, or if forage has recently been consumed. The advice of feeding chaff with hard feed is in part to the slow rate of passage and give further time for the processes of digestion.

The mechanisms for digestion in the small intestine include pancreatic juices, bile and enzymes. Of particular interest are the various enzymes responsible for digestion of protein and carbohydrates— the key nutrients often considered when choosing a racing diet. The ability to digest carbohydrate, namely starch, is dependent on two factors: firstly, form of starch and the level of alpha-amylase—a starch-digesting enzyme found in the small intestine. Whilst the horse is quite effective in digestion of protein, there are distinct limitations around digestion of starch.

Starch digestion, or lack of digestion in the small intestine, is the area of interest. When feeding, the aim is to achieve maximum conversion of starch in the small intestine to simple sugars for absorption. This is beneficial in terms of providing a substrate readily available for use as an energy source and reducing the ill effects seen when undigested starch moves into the next section of the digestive tract. Alpha-amylase is found in very limited supply in the equine small intestine—the amount present being only approximately 5% of that found within a pig. Despite a low content, the horse can effectively digest certain cereal starches, namely oats, quite effectively without processing. However, other grains commonly used, (e.g., barley and maize [corn]), have poor digestibility unless processed. Flaked, pelleted or extruded cereals undergo a change in starch structure enabling the enzyme to operate more effectively.

Processing grains whilst improving digestion does not alter the amount of enzyme present in the individual. An upper limit exists on starch intake, after which the system is simply overloaded and the workload is beyond the capacity of the naturally present enzymes. The level is estimated at 2g starch per kilogram of bodyweight in each meal fed. In practice, this translates to 3.5kg (7 ¾ lbs) of a traditional grain-based diet of 28% starch. In bowls, this is roughly 2 bowls of cubes or 2 ¼ bowls of mix—an intake typical of an evening feed. The ‘safe limit’ as a concept is questionable because of other factors involved in starch digestion, including how quickly a horse will eat their feed, dental issues and individual variation in the level of alpha-amylase present.

In practice, feeding racehorses will invariably test the capacity of the small intestine as the volume of feed required to meet the demands of training is significant, and through time constraints of both horse and human results in a large-sized evening meal. The addition of amylase or other enzymes to the diet is therefore of interest. Addition of amylase is documented to increase digestion of maize (corn)—one of the most difficult grains to digest—from 47.3% to 57.5% in equines (2). Equally, wheat digestion has been evidenced to improve with a combination of beta-glucanase, alpha-amylase and xylanase in equines, increasing starch digestion from 95.1% to 99.3% (3).

Use of enzymes in the diet has two areas of benefit: increasing starch conversion and energy availability, and reducing the amount of undigested starch that reaches the hindgut. The efficacy of the small intestine directly impacts the health of the large intestine—both of which influence performance.

Large Intestine

The caecum and colon, of which there are four segments, form the group referred to as the hindgut. Their environment and function are entirely different to that of the small intestine. Here, digestion is all about bacterial fermentation of the fibrous structures found in forages and parts of grains and other feed materials. The time taken to digest foodstuffs is also significantly different to that of the small intestine, with an average retention time of 30 hours.

The end result of fermentation is the production of fatty acids, namely acetate, butyrate and propionate—the other by-product of fermentation being lactate. The level of fatty acids and lactate produced is dependent on the profile of bacteria found within the gut, which in turn react to the type of carbohydrate reaching the hindgut. There are markedly different profiles for horses receiving a mostly fibre-based diet compared to those with a high-grain intake.

The interaction between the microbial organisms and metabolism, which directly influences health and disease, is gaining greater understanding. By looking at the faecal metabolome, a set of small molecules that can be identified in faecal samples, and the categories of bacteria in the gut, it is possible to investigate the interaction between the individual horse, its diet and bacteria. Of course, the first challenge is to identify what is normal or rather what is typical of a healthy horse so that comparatives can be made. Such work in horses in training, actively racing at the time of the study, has been carried out in Newmarket.

Microbiome is a term used to describe microorganisms, including bacteria, that are found within a specific environment. In the case of the horses in training, their microbiome was described before and after a period of dietary intervention. The study evidences the effect on the hindgut of including an enzyme supplement, ERME (Enzyme Rich Malt Extract). The table below shows changes in nine bacterial groups before and after supplementation.

Along with changes in bacterial abundance, which were relatively small, came more significant changes within the metabolome. The small molecules found in the metabolome are primarily acids, alcohols and ketones. Of particular interest, and where statistical significance was found, were changes in acetic acid and propionic acid evidencing an effect on the digestive process.

Whilst production of fatty acids is desired and a natural outcome of fermentation, further work is needed to determine what is an optimum level of fatty acid production. This study of horses in training is an interesting insight into an area of growing interest.

Effects on Performance & Large Intestine Function…

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Conformation and Breeding Choices

By Judy Wardrope

A lot of factors go into the making of a good racehorse, but everything starts with the right genetic combinations; and when it comes to genetics, little is black and white. The best we can do is to increase our odds of producing or selecting a potential racehorse. Examining the functional aspects of the mare and then selecting a stallion that suits her is another tool in the breeding arsenal.

For this article we will use photos of four broodmares and analyze the mares’ conformational points with regard to performance as well as matings likely to result in good racehorses from each one. We will look at qualities we might want to cement and qualities we might hope to improve for their offspring. In addition, we will look at their produce records to see what has or has not worked in the past.

In order to provide a balance between consistency and randomness, only mares that were grey (the least common color at the sale) with three or more offspring that were likely to have had a chance to race (at least three years old) were selected. In other words, the mares were not hand-picked to prove any particular point.

All race and produce information was taken from the sales catalogue at the time the photos were taken (November 2018) and have not been updated.

Mare 1

Her lumbosacral gap (LS) (just in front of the high point of croup, and the equivalent of the horse’s transmission) is not ideal, but within athletic limits; however, it is an area one would hope to improve through stallion selection. One would want a stallion with proven athleticism and a history of siring good runners.

The rear triangle and stifle placement (just below sheath level if she were male) are those of a miler. A stallion with proven performance at between seven furlongs and a mile and an eighth would be preferable as it would be breeding like to like from a mechanical perspective rather than breeding a basketball star to a gymnast.

Her pillar of support emerges well in front of the withers for some lightness of the forehand but just behind the heel. One would look for a stallion with the bottom of the pillar emerging into the rear quarter of the hoof for improved soundness and longevity on the track. Her base of neck is well above her point of shoulder, adding additional lightness to the forehand, and she has ample room behind her elbow to maximise the range of motion of the forequarters. Although her humerus (elbow to point of shoulder) shows the length one would expect in order to match her rear stride, one would likely select a stallion with more rise from elbow to point of shoulder in order to add more lightness to the forehand.

Her sire was a champion sprinter as well as a successful sire, and her female family was that of stakes producers. She was a stakes-placed winner at six furlongs—a full-sister to a stakes winner at a mile as well as a half-sister to another stakes-winning miler. Her race career lasted from three to five.

She had four foals that met the criteria for selection; all by distance sires of the commercial variety. Two of her foals were unplaced and two were modest winners at the track. I strongly suspect that this mare’s produce record would have proven significantly better had she been bred to stallions that were sound milers or even sprinters.

Mare 2

Her LS placement, while not terrible, could use improvement; so one would seek a stallion that was stronger in this area and tended to pass on that trait.

The hindquarters are those of a sprinter, with the stifle protrusion being parallel to where the bottom of the sheath would be. It is the highest of all the mares used in this comparison, and therefore would suggest a sprinter stallion for mating.

Her forehand shows traits for lightness and soundness: pillar emerging well in front of the withers and into the rear quarter of the hoof, a high point of shoulder plus a high base of neck. She also exhibits freedom of the elbow. These traits one would want to duplicate when making a choice of stallions.

However, her length of humerus would dictate a longer stride of the forehand than that of the hindquarters. This means that the mare would compensate by dwelling in the air on the short (rear) side, which is why she hollows her back and has developed considerable muscle on the underside of her neck. One would hope to find a stallion that was well matched fore and aft in hopes he would even out the stride of the foal.

Her sire was a graded-stakes-placed winner and sire of stakes winners, but not a leading sire. Her dam produced eight winners and three stakes winners of restricted races, including this mare and her full sister.

She raced from three to five and had produced three foals that met the criteria for this article. One (by a classic-distance racehorse and leading sire) was a winner in Japan, one (by a stallion of distance lineage) was unplaced, and one (by a sprinter sire with only two starts) was a non-graded stakes-winner. In essence, her best foal was the one that was the product of a type-to-type mating for distance, despite the mare having been bred to commercial sires in the other two instances.

Mare 3 ….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Antimicrobial resistance

By Jennifer Davis and Celia Marr

Using antimicrobials as effectively as possible helps to reduce their use overall. For septic arthritis, intravenous regional perfusion of antimicrobials can achieve very high concentrations within a specific limb. This involves placing a temporary tourniquet to reduce blood flow away from the area while the antimicrobial is injected into a nearby blood vessels. The technique is suitable for some but not all antimicrobial drugs.

Growing numbers of bacterial and viral infections are resistant to antimicrobial drugs, but no new classes of antibiotics have come on the market for more than 25 years. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria cause at least 700,000 human deaths per year according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Equivalent figures for horses are not available, but where once equine vets would have very rarely encountered antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, in recent years this serious problem is a weekly, if not daily, challenge.

The WHO has for several years now, designated a World Antibiotic Awareness Week each November and joining this effort, British Equine Veterinary Association and its Equine Veterinary Journal put together a group of articles exploring this problem in horses.

How do bacterial populations develop resistance?

Certain types of bacteria are naturally resistant to specific antimicrobials and susceptible to others. Bacteria can develop resistance to antimicrobials in three ways: bacteria, viruses and other microbes, which can develop resistance through genetic mutations or by one species acquiring resistance from another. Widespread antibiotic use has made more bacteria resistant through evolutionary pressure—the “survival of the fittest” principle means that every time antimicrobials are used, susceptible microbes may be killed; but there is a chance that a resistant strain survives the exposure and continues to live and expand. The more antimicrobials are used, the more pressure there is for resistance to develop.

The veterinary field remains a relatively minor contributor to the development of antimicrobial resistance. However, the risk of antimicrobial-resistant determinants travelling between bacteria, animals and humans through the food chain, direct contact and environmental contamination has made the issue of judicious antimicrobial use in the veterinary field important for safeguarding human health. Putting that aside, it is also critical for equine vets, owners and trainers to recognise we need to take action now to limit the increase of antimicrobials directly relevant to horse health.

How does antimicrobial resistance impact horse health?

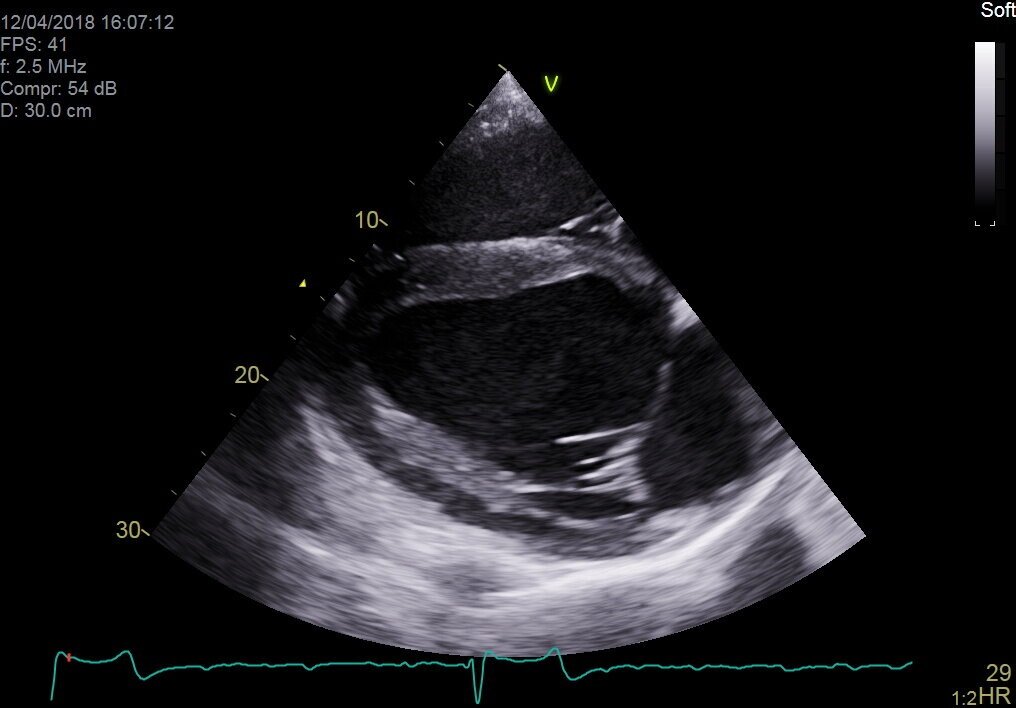

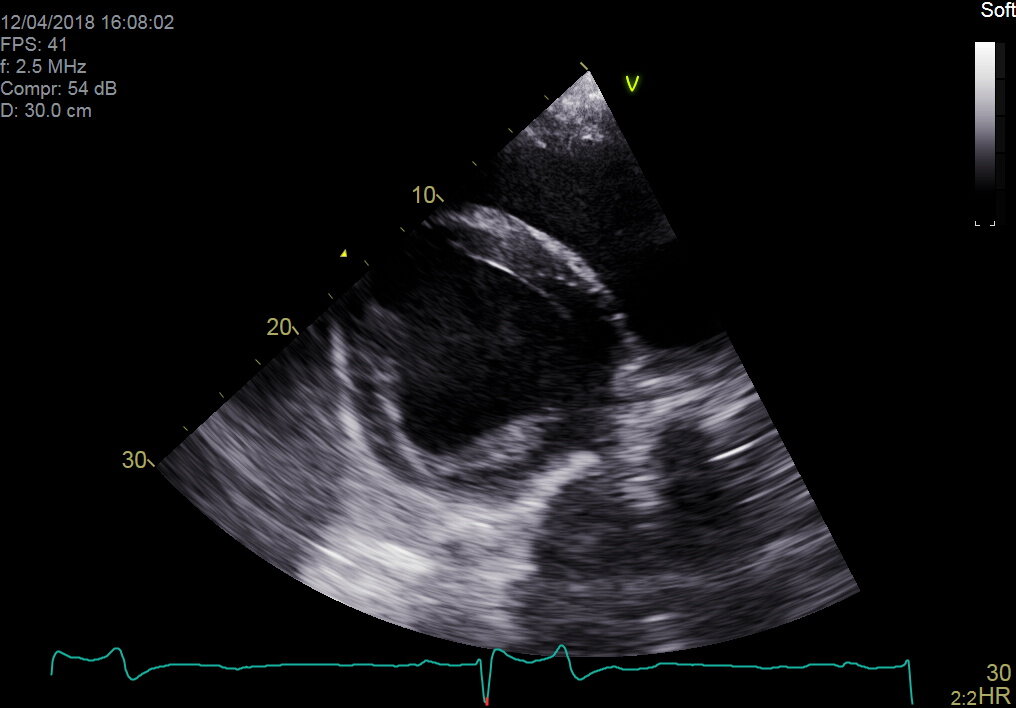

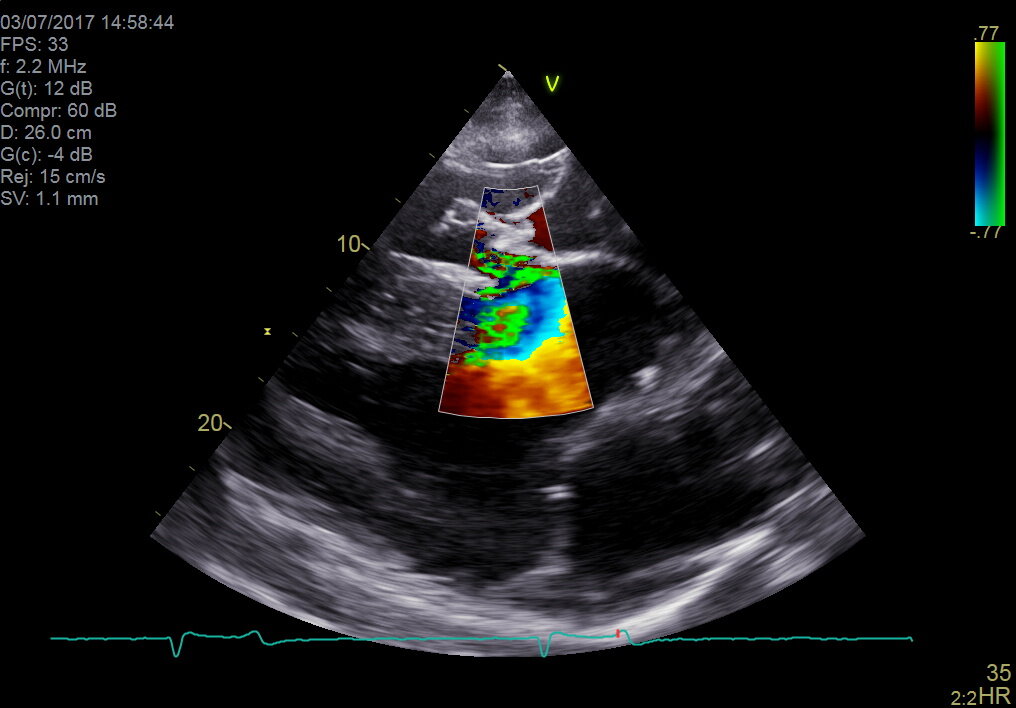

This mare’s problems began with colic; she underwent surgery to correct a colon torsion (twisted gut). When the gut wall is damaged, bacteria easily spread throughout the body. The mare developed an infection in her surgical incision and in her jugular veins, progressing eventually to uncontrollable infection—resistant to all available antimicrobials with infection of the heart and lungs.

The most significant threat to both human and equine populations is multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli, MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium, and rising MDR strains of Salmonella spp. and Clostridium difficile. In an analysis of 12,695 antibiograms collected from horses in France between 2012-2016, the highest proportion (22.5%) of MDR isolates were S. aureus. Identification of ESBL E.coli strains that are resistant to all available antimicrobial classes has increased markedly in horses. In a sampling of healthy adult horses at 41 premises in France in 2015, 44% of the horses shed MDR E.coli, and 29% of premises shedding ESBL isolates were found in one third of the equestrian premises. Resistant E. coli strains are also being found in post-surgical patients with increasing frequency.

Rhodococcus equi is a major cause of illness in young foals. It leads to pneumonia and lung abscesses, which in this example have spread through the entire lung. Research from Kentucky shows that antimicrobial resistance is increasingly common in this bacterial species.

Of major concern to stud owners, antimicrobial-resistant strains of Rhodococcus equi have been identified in Kentucky in the last decade, and this bacteria can cause devastating pneumonia in foals. Foals that are affected by the resistant strains are unlikely to survive the illness. One of the leading authorities on R equi pneumonia, Dr Monica Venner has published several studies showing that foals can recover from small pulmonary abscesses just as quickly without antibiotics, and has pioneered an ‘identify and monitor’ approach rather than ‘identify and treat’. Venner encourages vets to use ultrasonography to quantify the infected areas within the lung and to use repeat scans, careful clinical monitoring and laboratory tests to monitor recovery. Antimicrobials are still used in foals, which are more severely affected, but this targeted approach helps minimise drug use.

What can we do to reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance?

Faced with a coughing horse, trainers will often pressure their vet to administer antibiotics, hoping this will clear the problem up quickly. Many respiratory cases will recover without antibiotics, given rest and good ventilation.

The simple answer is stop using antimicrobials in most circumstances except where this is absolutely avoidable. In training yards, antimicrobials are being over-used for coughing horses. Many cases are due to viral infection, for which antibiotics will have little effect. There is also a tendency for trainers to reach for antibiotics rather than focusing on improving air quality and reducing exposure to dust. Many coughing horses will recover without antibiotics, given time. Although it has not yet been evaluated scientifically, adopting the ‘identify and monitor’ approach, which is very successful in younger foals, might well translate to horses in training in order to reduce overuse of antimicrobials.

Vets are also encouraged to choose antibiotics more carefully, using laboratory results to select the drug which will target specific bacteria most effectively. The World Health Organization has identified five classes of antimicrobials as being critically important, and therefore reserved, antimicrobials in human medicine. The critically important antimicrobials which are used in horses are the cephalosporins (e.g., ceftiofur) and quinolones (e.g., enrofloxacin), and the macrolides, which are mainly used in foals for Rhodococcal pneumonia. WHO and other policymakers and opinion leaders have been urging vets and animal owners to reduce their use of critically important antimicrobials for well over a decade now. Critically important antimicrobials should only be used where there is no alternative, where the disease being treated has serious consequences and where there is laboratory evidence to back up the selection. British Equine Veterinary Association has produced helpful guidelines and a toolkit, PROTECT-ME, to help equine vets achieve this.

How well are we addressing this problem?….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Roarers - surgery for recurrent laryngeal neuropathy – impact and outcomes

By Safia Barakzai BVSc MSc DESTS Dipl.ECVS

Recurrent laryngeal neuropathy (RLN), more commonly known as ‘roaring’, ‘laryngeal paralysis’ and ‘laryngeal hemiplegia’ is a disorder affecting primarily the left recurrent laryngeal nerve in horses >15hh. This nerve supplies the muscles that open and close the left side of the larynx. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve is also now proven to be affected, but only very mildly, thus affected horses very rarely show signs of right-sided dysfunction.

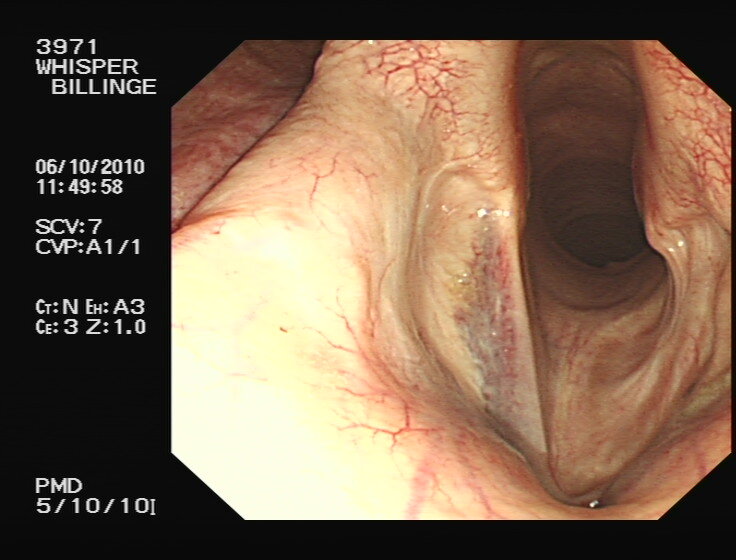

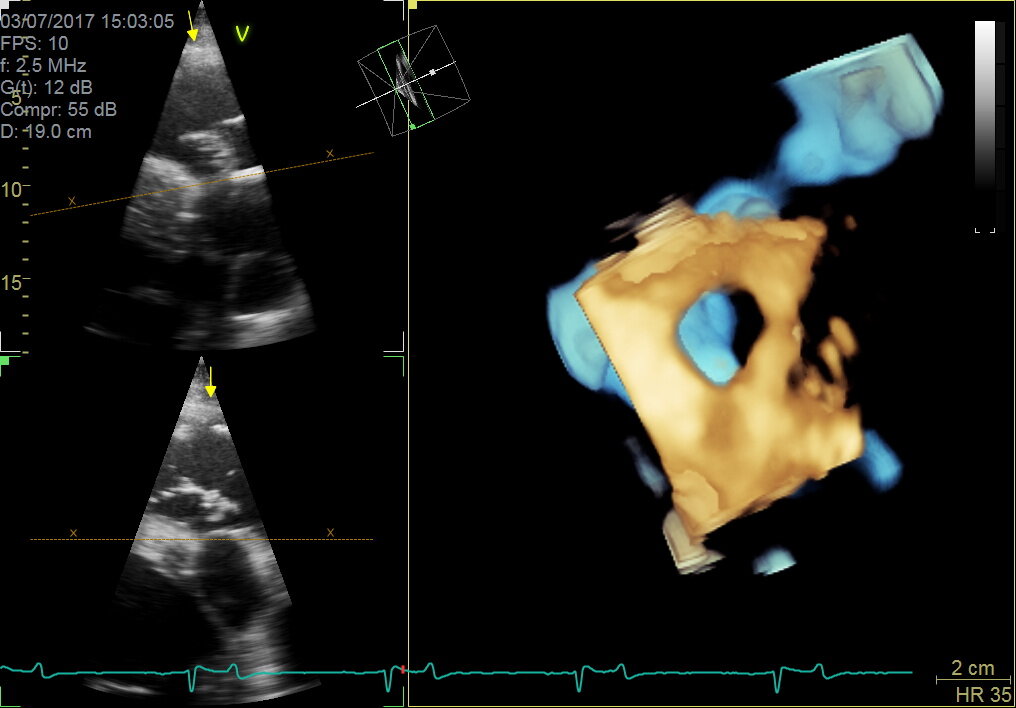

Horses with RLN become unable to fully open (abduct) the left side of their larynx. During exercise they then make abnormal inspiratory noise due to collapse of both the vocal fold(s) and the left arytenoid cartilage (figure 1), and airflow to the lungs can become severely obstructed in advanced cases. There is a proven genetic component to RLN, but in many cases the disease progresses over months or years. The age at which clinical signs become apparent is highly variable. Foals can show endoscopic and pathologic evidence of RLN, but some horses do not develop clinical disease until >10 years old.

Treatment of RLN

Laryngoplasty (tie-back) being performed in standing sedated horses.

Traditionally, left-sided ventriculocordectomy (‘Hobday’/ventriculectomy plus vocal-cordectomy surgery) and laryngoplasty (‘tie-back’) surgeries have been used to treat the disorder, depending on which structures are collapsing and how severely. The intended use of the horse, the budget available and other concerns of the owner/trainer also come into play. New techniques of providing a new nerve supply (‘re-innervating’) to the affected muscle are now being trialled in clinical cases. Pacing the muscle with an implanted electronic device has also been attempted in research cases.

Ventriculocordectomy

Ventriculocordectomy is commonly now referred to as a ‘Hobday’ operation; however, the ‘Hobday’ actually only refers to removal of the blind ending sac that constitutes the laryngeal ventricle. Currently, surgeons tend to remove the vocal cord as well as the ventricle, because it is vocal cord collapse that creates the ‘whistling’ noise. It is a relatively straightforward surgery to perform with minimal risks and complications for the patient. In the last 15 years, there has been a shift to performing it in a minimally invasive way, using a diode laser under endoscopic guidance in the standing sedated horse rather than with the conventional method, via an open laryngotomy incision on the underside of the neck with the horse under a general anaesthetic. However, transendoscopic laser surgery is technically difficult with a very steep learning curve for the surgeon. All ventriculocordectomies are not equal (Fig. 2) and for both laser and ‘open surgery’ methods, incomplete resection of the fold can leave behind enough tissue to cause ongoing respiratory noise and/or airway obstruction after surgery.

Severity of disease can be reasonably estimated using endoscopy in the resting horse (grades 1-4), but the gold standard for assessing this disease is endoscopy during exercise, when the high negative pressure—generated when breathing—test the affected laryngeal muscle, which is trying its best to resist the ‘suction’ effect of inspiration.

During exercise, RLN is graded from A to D, depending on how much the left side of the larynx can open.

Figure 2: Two horses after ventriculocordectomy surgery. The horse on the left has an excellent left-sided ventriculocordectomy, with complete excision of the vocal fold tissue (black arrow). The right cord is intact, but the right ventricle has been removed (‘Hobday’). The horse on the right has bilaterally incomplete vocalcordectomies, with much of the vocal fold tissue left behind.

Sports horses, hunters and other non-racehorses were often previously recommended to have a ventriculocordectomy performed rather than a laryngoplasty, even if they had severe RLN. This decision was often made on the grounds of cost, but also due to fear of complications associated with laryngoplasty (‘tie-back’ surgery). A new study has shown that for horses with severe RLN, a unilateral ventriculocordectomy is actually extremely unlikely to eliminate abnormal noise in severely affected horses, because the left arytenoid cartilage continues to collapse.3 The authors recommended that laryngoplasty plus ventriculocordectomy is a better option than ventriculocordectomy alone for all grade C and D horses if resolution of abnormal respiratory noise and significant improvement of the cross sectional area of the larynx are the aims of surgery.

Advancements in laryngoplasty (‘tie-back’) surgery

Laryngoplasty is indeed one of the most difficult procedures that equine surgeons perform ….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

EMHF UPDATE - What’s been going on at The European Mediterranean Horseracing Federation - Dr Paull Khan reports on a busy end of year schedule

By Dr Paull Khan

WINDSOR AND CHELTENHAM: EMHF EXECUTIVE COUNCIL MEETING

Britain had never before hosted a meeting of the EMHF’s Executive Council. We try to move this annual event around, between as many member countries as possible, so as to further our education of the sport in our region and give the host country a chance to showcase its racing. We have had some memorable racing experiences to accompany our reunions in recent years, including the fearsome fences of Pardubice; the quirky charms of the Grand Steeplechase des Flandres; and the glorious ocean views of Jersey’s Les Landes racecourse. So the pressure was certainly on the British Horseracing Authority to provide an occasion befitting one of Europe’s major racing nations. They did not disappoint, although the British weather all but conspired to ruin the party. The Saturday of Cheltenham’s November Meeting always serves up some of the best jump racing outside the festival itself, and for several of our number, it was the first visit to jump racing’s beating heart. The management of Cheltenham were extraordinarily generous, receiving us all in its Royal Box.

The following day, it was time to do some business, and the spookily imposing Oakley Court Hotel in Windsor, on the banks of the River Thames, provided our base. For fans of the Rocky Horror Picture Show, this was Dr Frank N. Furter’s castle and was also a star of over 200 films including The Brides of Dracula and The Plague of the Zombies. A fitting venue, then, for our nine-strong Executive Council.

Our constitution dictates that representatives of France, Ireland and Great Britain, (as the three EuroMed countries with the largest-scale racing industries), have permanent seats on the ‘Executive Council’ (ExCo). In addition, at least one will always represent the Mediterranean countries, and another the non-European Union countries. This year, we re-elected our chairperson, Brian Kavanagh, also CEO of Horse Racing Ireland, who has held the role since the EMHF’s inception, in 2010. Omar Skalli, CEO of the racing authority of Morocco, was also re-elected as one of our three vice-chairs.

One of the seats on the ExCo of our parent body, the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA), is reserved for the EMHF, to represent our ‘smaller’ racing nations. We agreed to repeat the nomination of Rudiger Schmanns, experienced racing director at Germany’s Direktorium.

Very sadly, we said farewell to both Austria and Libya. The continued political upheaval in Libya is well known to us all, and Austria’s thoroughbred racing activity has regrettably shrunk to such an extent that its Direktorium felt unable to continue as members. We hope very much that they will feel able to return one day.

On the positive side, there has been a flurry of interest in joining the EMHF, with Bulgaria, Romania and Russia all expressing an interest. A process of inspection precedes the accession of any new racing authority, and this will take place in these three countries over forthcoming months.

A key role of EMHF is to keep our members abreast of changes to the International Agreement on Breeding, Racing and Wagering (International Agreement). There have been more changes than ever this year, and the key ones were explained. We also discussed the prospects of more EuroMed countries being able, in future, to stage Black Type races.

We wanted to take advantage of being in Britain by arranging for presentations to be made covering some areas in which British racing has chosen to place more resources than have other racing authorities. One such are the efforts being made to increase the degree of diversity to be found within the sport. Rose Grissell, recently appointed as Head of Diversity and Inclusion in British Racing, described the work that she and the BHA’s Diversity in Racing Steering Group are engaged in. Tallulah Lewis then explained the role and aims of Women in Racing—the organisation of which she is the new chair. The second British ‘specialty’ we chose was the work done at the BHA on analysing betting patterns. Chris Watts, Head of Integrity at the BHA, presented on his team’s work identifying suspicious activity, thereby upholding the integrity of the racing and fending off race-fixing attempts.

ROME: INSPECTION VISIT, ITALIAN MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE

Not many racing authorities have their headquarters in a palace. The governing body for horse racing in Italy is the country’s Ministry of Agriculture (MIPAAFT), whose offices are situated in the magnificent Palazzo dell'Agricoltura, a building replete with paintings, frescos adorning ceilings and walls, wrought-iron decorations and stained-glass windows. It also houses a world-renowned library of all things agricultural.

In January 2019, the European Pattern Committee (EPC) announced that, in view of various ongoing concerns relating to the administration of racing in Italy, not least MIPAAFT’s record of prize money payment, the country would no longer be a full member of the Committee, but would become an associate member and be subject to monitoring. That process has now begun, and this was the first of three planned visits which I shall make by way of an inspection programme, likely to conclude in the summer. The inspection is not restricted in its scope to race planning matters and is therefore being undertaken under the EMHF’s auspices. Additionally, it is evidence of the EPC working ‘with Italy to try to progress matters as quickly as possible such that Italy will hopefully become a full member of the EPC again in the near future’.

SOFIA: INSPECTION VISIT, BULGARIAN NATIONAL HORSE RACING ASSOCIATION….

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

What is equine welfare? Asks Johnston Racing’s vet Neil Mechie

Neil Meche

The world of equine welfare—and animal welfare in general—is a proverbial can of worms. Decisions regarding equine welfare must be made on logical scientific evidence and not be biased by emotion or fear of incorrect perceptions in the media or public eye. As with many things in life, education is the key, especially in a world where large parts of the population have very little experience or knowledge of keeping or working with animals.

The welfare of animals is protected in national legislation in the UK. The Animal Welfare Act 2006 makes owners and keepers responsible for ensuring that the welfare needs of their animals are met. These include the need:

for a suitable environment (place to live)

for a suitable diet (food and water)

to exhibit normal behaviour patterns

to be housed with, or apart from, other animals (if applicable)

to be protected from pain, injury, suffering and disease

Reading these concise bullet points, one would think it quite simple to meet these needs, but issues arise when it comes to interpreting and putting this guidance into practice.

As an insight into how emotive language can change the interpretation of animal welfare requirements, below are the The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) “Five Freedoms,” which are not too dissimilar to the above but portrayed in a different light:

Freedom from hunger and thirst

Freedom from discomfort

Freedom from pain, injury or disease

Freedom to express normal behaviour

Freedom from fear and distress

The RSPCA is a charity champions animal welfare, and the use of words such as hunger, thirst, discomfort, fear and distress conjure up images of tortured animals wasting away in squalor. There is no need for this dramatic language when the preservation of welfare only actually requires common sense and compassion.

The same can be said when considering the welfare of horses, but sadly this is not the case. The biggest welfare issues facing the horse population are not, as the media would have you think, horses breaking their legs on racetracks or the travelling community mistreating horses at Appleby Fair. It is obesity and the mis-management of horses in the general population. Every day horses are being killed by a plethora of issues caused by over-feeding and poor management regimes. Laminitis, colic and numerous hormonal and metabolic diseases negatively affect the welfare of thousands of horses each year and are in a large part caused by the poor knowledge and horsemanship of their owners. It is now a large part of most equine vets’ job to educate horse owners on appropriate feeds and management regimes for their horses.

Racehorses, on the contrary, are looked after with the highest of standards as they are athletes competing at a high level.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Are we going soft on our horses?

By Amy Barstow

Over the years there has been a steady move away from traditional concrete surfaces in yards towards surfaces that are generally considered softer, such as rubber. Furthermore, in some areas, the surfaces of the tracks which link yards with training facilities (horse walks) have also moved towards ‘softer’ surfaces. This has led some to wonder if our horses are missing out on a key opportunity to condition their musculoskeletal system. This article will explore what the scientific research tells us about how different surfaces affect the horse and what this might mean for musculoskeletal conditioning and injury resistance.

The majority of the research that has highlighted the links between surfaces and injuries is from epidemiology studies. These studies view large populations of horses and pull together lots of different factors to elucidate risk factors for injury. They, therefore, do not attempt to investigate why surfaces may be implicated as a risk. To understand the link between surface and injury risk, other types of research must be done including biomechanics studies, lab-based studies on bone and tendon samples and prospective experimental studies. Biomechanics studies explore how the horse, especially their limbs and feet, move on different surfaces and the forces and vibrations that they experience. Lab-based work investigates how musculoskeletal tissues respond to loading and vibrations at the cellular and extracellular level. Prospective experimental studies take a group of horses and expose them to different environments (e.g., conditioning on different surfaces). Then you compare the groups, for example, looking for signs of musculoskeletal injury using diagnostic imaging techniques. The research done using these different techniques can then be pieced together to help us decide how to better manage the health and performance of racehorses.

There is a wealth of epidemiological data to suggest that the surface type and condition during racing influences the occurrence of musculoskeletal injuries in the racehorse. Though it must be remembered that musculoskeletal injury is multifactorial with training regimens, race distance, the number of runners, horse age and sex all coming into play. Though there are comparably fewer data available relating to the effect of training surface type and properties on musculoskeletal injury rates, what is available also suggests that firmer surfaces increase the risk of sustaining an injury either during training or racing. For example, horses trained on a softer, wood fibre surface are less likely to suffer from dorsal metacarpal disease (bucked shins) than those trained on dirt tracks. However, horses trained on a traditional sand surface have been shown to be at a greater risk of injury (fracture) during racing. This could be due to the soft sand surface not stimulating sufficient skeletal loading to adequately condition the musculoskeletal system for the forces and loading experienced during racing. It could also be the result of horses racing on a surface with very different properties to those that they trained on.

So far the majority of the scientific research discussed relates to horses galloping and cantering, which are not the gaits that they will generally be using around the yard or getting to and from the gallops. There is very little work to link sub-maximal (low) speed exercise on different surfaces to injury in horses. In a small group of Harness (trotting) horses, those trained on a softer surface had a lower incidence of musculoskeletal pathology identified using diagnostic imaging techniques, compared to those trained on a firm surface. There is also evidence of the benefit of softer surfaces in livestock housing. Experimental work by Eric Radin in the 1980s found that sheep kept on a concrete floor compared to a softer dirt floor had more significant orthopaedic pathologies at postmortem. Furthermore, the use of rubber matting reduces the incidence of foot lameness in dairy cattle. So it would appear that a softer ground surface is beneficial even at sub-maximal intensity locomotion.

The epidemiological data discussed so far tells us that surface can play a role in injury, but it does not provide any answers for why that may be the case. From a veterinary and a scientific perspective, I am interested in how different surfaces influence limb vibration characteristics and loading in horses. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Diversity and inclusion in European racing

By Dr Paull Khan

When France decided in 2016 to introduce a weight allowance for female riders, it set the racing world murmuring and shone a light on the issue of gender diversity among jockeys.

Jean-Pierre Columbu, vice-president of France Galop, explains: “My president, Edouard de Rothschild, who had introduced Lady Riders’ races about a decade earlier, still felt they were something of a ‘ghetto’, and wanted to do more to see females compete on equal terms”. The 2-kg (4.4lbs) allowance applied to both flat and jump races, but excluded Pattern races. Last year, the allowance was reduced on the flat to 1.5kg.

It was a bold step and one that has quickly produced some dramatic results. Within three years, female professional flat jockeys are getting three times the number of rides they used to, and their winners tally has risen by a staggering 340%. Despite the exclusion of the most lucrative races, the prize money won by horses ridden by females has also nearly trebled, from €4.1M to €12M. To Columbu, this increase in earnings among lady riders is crucial to the recruitment and retention of women. “In our Jockey School”, he notes, “65% are now female. And there are, of course, many, many females in our stables who must have the opportunity to earn money”.

Indeed, it could be said that that the allowance has achieved its objective. Female riders’ percentage of rides, which are winners, has improved from 7.14% to 9.08%—rapidly closing in on the male riders’ equivalent figure of 9.73%. So has the experiment run its course, and will the allowance soon be phased out? Columbu does not think so.

“The allowance is going to stay”, he concludes. “I used to be a surgeon. In males, 35% of body weight is made up of muscle. In women, that figure is 27%. That is why the allowance is needed”.

Of course, France is far from being alone in experiencing under-representation of women riders.

Other countries have been studying the French experiment with interest from afar. In Britain, flag-bearer Hayley Turner’s exploits are well-known. However, not all in the garden is rosy. Rose Grissell, recently appointed Head of Diversity and Inclusion for British Racing, notes: “Recent successes should be celebrated and promoted, but there is further to go. Fourteen percent of professional jockeys are female, but women receive just 8.2% of the rides and, in 2018, no woman rode in a flat Gp1 race. So, while the trends are in many ways encouraging, they do not apply across the board”.

These concerns are echoed by the organisation Women in Racing. Established in 2009, Women in Racing was formed to encourage senior appointments at Board level across the industry and to attract more women into the sport. That ambition remains, but today, according to its chair, Tallulah Lewis, there is more focus on strengthening career development for women at all levels. For Lewis, a prime concern is the attrition rate; in other words, the fact that the 14% figure for female riders that we have noted above occurs despite the ratio of new recruits entering into racing through the two racing schools in Britain, being as high as 70:30 in favour of females. Understanding their lack of progression is a key aim.

Grissell, indeed, intends to examine issues of recruitment, training and retention, looking to help either remove the barriers to lady riders’ success or to lend support. One tactic might be to challenge the perception of the innate inferiority of the female jockey. Grissell again: “A study by PhD student Vanessa Cashmore identified that punters undervalue women riders: a woman riding a horse at odds of 9/1 had the same chance of victory as a man riding one at 8/1”.

Such findings call into question the need for a gender-based riders’ allowance and, indeed, British lady riders themselves have voiced opposition to the concept.

The French experiment—and its undoubted success—presents a dilemma to those who seek better outcomes for women riders but who are convinced that they are equally effective as their male counterparts, given the opportunities.

“We applaud what the French have done in this experiment, as it gives us all more information than we had before”, says Lewis. “Our concern is that it is based on the premise that women are not men’s equal when it comes to race riding—something the evidence disproves”.

Belgium, which boasts the highest percentage of the countries polled, has crunched the numbers and decided against following the French example. Marcel de Bruyne, director of the Belgian Gallop Federation, explains:

“We have the same percentage of females—43% among our professional and amateur riders and, as they achieve approximately the same percentage of winning rides as the men, we do not envisage giving a weight allowance for females”.

(All of which suggests Belgium would make an interesting case study.)

Spain, by contrast, is due to have introduced a 1.5-kg allowance for females by the time this magazine is published. It would be surprising if other countries did not decide to follow suit, either by replicating the weight allowance or conjuring some other incentive for the female jockey. A prize money premium for connections who engage female riders would be one such option, which would have the benefit of leaving the actual terms of competition undistorted.

Of course, gender diversity is but one aspect of diversity in general. It is often the first to be tackled because of the (at least traditional) binary classification applying to the sexes, and the relative ease of data collection. But diversity and inclusion in ethnic or racial terms, in sexual orientation and identification, in physical ability, etc. are all key components when assessing the extent to which a sub-group reflects the wider society in which it sits.

The argument is now widely accepted that homogeneity stifles innovation and that, in addition to any altruistic motivation for advancing the cause of the under-represented, there is also an economic, self-interested imperative for organisations to do so. And there is every reason to suppose that this applies equally to racing. The benefits, in terms of staff recruitment and retention, for example, that would likely flow from well-managed diversity should be just as applicable to, say, a trainer’s yard as to any other commercial operation.

Talking of trainers, the table below shows the percentage of female professional licensed trainers by country, and as with the professional jockeys, again reveals a very wide variation.

What, if anything, is being done to address this disparity? Or indeed, manifestations of a lack of diversity among other groups within racing: administrators and racecourse executives, for example, or, looking more broadly, among those who attend races, or place bets on horseracing?

The short answer would appear to be: not a lot. The country which has done by far the most work in this space would appear to be Great Britain where, two years ago, the British Horseracing Authority established a Diversity in Racing Steering Group.

The story starts in 2017, when Women in Racing jointly commissioned and published a study by Oxford Brookes University, entitled ‘Women’s representation and diversity in the horseracing industry’. The report found evidence of ‘a lack of career development opportunities (at all levels including jockeys), progression and support, some examples of discriminative, prejudice and bullying behaviour, barriers and lack of representation at senior and board level, and negative experiences of work-life balance and pastoral care’.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Down Royal racecourse, tradition reborn

By Lissa Oliver

Down Royal racecourse in Northern Ireland boasts a heritage as regal as its name. They have been racing on the course since the early 18th century—the land originally donated by the first Marquess of Downshire, but its history goes back even further. In 1685, King James II issued a Royal Charter and formed the Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders. In 1750, King George II donated £100 to run the King’s Plate, a race still run today as one of the summer’s highlights, the 2800m Listed Her Majesty’s Plate. The Ulster Derby, now a premier handicap, is the most valuable Flat race hosted by the track, but Down Royal is best loved for the National Hunt Festival held at the start of November and headlined by the Champion Chase.

Inevitably, a rich history must also include challenges and threats and the racecourse has been no exception. As recently as last year the course faced the prospect of closure, its operators, Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders, signalling intent to cease operations in October. Fortunately, owners Merrion Property Group took over the running of the course from January of this year and it has been business as usual.

Emma Meehan CEO

With a bright new future and lofty ambitions, Manager Emma Meehan is charged with seeing those aims achieved, but the path ahead remains fraught with new challenges, not least the spectre of Brexit. Based in the UK, but under the authority of the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board (IHRB), places Down Royal in a tricky position and the timing of the NH Festival opening on 1 November could bring unknown difficulties.

“The impact of any change in the current Tripartite Agreement could create initial difficulties”, Meehan recognises. “We remain in limbo regarding Brexit and continue to communicate with DAERA and the IHRB. We are ready to react to support the passage of runners and riders to our flagship festival on Friday 1 November and Saturday 2 November and beyond. The landscape is changing daily at British Parliamentary level; a general election could be on the cards very soon. Whatever the outcome, we will adapt to any new requirements and ensure we provide maximum assistance to our owners and trainers”.

Facing the unknown isn’t new territory to Meehan and she joined Down Royal at a particularly difficult time, following a successful 14 years as marketing manager at Dundalk Racing Stadium. “I found the transition in the early stages tumultuous to say the least”, she admits. “I likened it to trying to put a jigsaw puzzle back together again and I had to figure out where pieces were and, indeed, that some individuals were holding some of those pieces behind their backs. It was a challenging phase, but one that I grew from personally.

“Fast-forward to now; nine months on and I have a wonderful team and I couldn’t be happier.

The support I have received from Merrion Property Group and their progressive mind-frame has complimented my thinking at all levels. Merrion Property Group have a vision for Down Royal, with racing centric to that vision. We have a five-year investment strategy in the pipeline to bring the facilities, both for the social racegoers and racing fraternity, in line with a Grade 1 track, and modernising in tandem. I’m very excited about the changes afoot at Down Royal”.

In the modern landscape, investing in a racecourse doesn’t seem the best of ventures, particularly a ‘fixer-upper’ in property agent parlance, but Merrion Property Group bought the racecourse as far back as 2006 and saw the end of the lease with the Down Royal Corporation of Horse Breeders as an opportunity to run its own racing-centred business from the track.

“The overall site and infrastructure at Down Royal are huge. Continuous investment is fundamental to remaining competitive in the industry and providing a best in class environment for owners, trainers, bookmakers, punters and all the services and supports which go into racing”, Meehan explains.

“Our aim is to provide memorable and sociable experiences for groups, businesses and sports people, looking to bring together racing, good food and entertainment. Our investment compliments this objective”.

She sees the importance and influence of a community vital and central to the objectives of the new management. “It’s hugely important that the racecourse is the epicentre of the local community, and it’s our intention to embrace the community through several initiatives. Looking ahead to 2020, we are choosing local charities to collect at our gates, ensuring that the platform and the opportunity to raise monies is directed back to our charitable community partners. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Planning a diagnostic-led worm control programme

Common horse worms

By Dr Corrine Austin (Austin Davis Biologics) and Prof Jacqui Matthews (Roslin Technologies)

Planning a diagnostic-led worm control programme

All horses are exposed to worms while grazing, but how we control these parasites is essential to horse health and performance. Most horse owners are aware of testing to determine whether their horse needs deworming. The tests comprise faecal worm egg counts (FEC) for redworm/roundworm detection and saliva testing to detect tapeworm infections (standard FEC methods are unreliable for tapeworm). Until now, encysted small redworm larvae have remained undetectable as FEC only determines the presence of egg laying adult worms. This has meant that routine winter moxidectin treatment has become recommended practice to target potentially life-threatening burdens of small redworm encysted larvae. Excitingly, a new small redworm blood test is being commercialised* which detects all stages of the small redworm life cycle, including the all-important encysted larval phase. Together, these tests offer a complete worm control programme for common horse worms using diagnostic information. This is known as ‘diagnostic-led worm control’ (see Figure 1 for common worms in horses). Essentially, testing is used to tell you whether your horse needs deworming or not.

Why should you use testing to determine whether you should use dewormers or not?

Gone are the days of routinely administering dewormers to every horse and hoping for the best. That strategy is outdated as it has caused widespread drug resistance in worms (i.e., worms are able to survive the killing effects of dewormers and remain in place after treatment, which can lead to disease and in worst cases, death). To reduce the risk of further resistance occurring, we need to ensure that dewormers are only used when they are genuinely needed—when testing detects that horses have a worm burden requiring treatment. Regular testing also helps identify horses likely to be more susceptible to infection and thus at risk of disease in the future.

How to plan your horse’s worm control programme ….

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer Profile: Cathrine Erichsen

By Amie Karlsson

With 400 winners and plenty of pattern-race successes to her name, Cathrine Erichsen is the most successful female trainer ever in Norway.

This interview takes us to Oslo, or to be more precise, a 12-km drive northwest of the city center. Here, tucked away in a quiet residential area, we find Øvrevoll Galoppbane, the sole thoroughbred venue in Norway.

It is the end of August. Erichsen, an independent, charismatic woman with more than 400 winners under her belt, has just got back to routine again after the Norwegian Derby Weekend—the highlight of the Norwegian racing calendar a few days earlier.

Øvrevoll is where Erichsen participated in her first amateur race, saddled her first winner and enjoyed her first black type success. Today, it is where she cares for a string of almost 25 thoroughbreds. Erichsen is one of ten professional trainers at Øvrevoll—there are twenty in total in the country—and she has her base in one of the barns on the backstretch.

She has been training for half her life, but the last four years have been particularly fruitful. In the last three weeks of August, she had won two Gp3 races in Scandinavia with two different horses.

In the middle of summer, Øvrevoll is a beautiful place. Barns, outdoor boxes, lunge pits, paddocks and horse walkers are scattered around the backstretch and in the infield. It is charming and a little bit unpolished racing venue surrounded by mature trees, which provide green barriers between the racecourse and the adjacent villas.

Right now, November seems an eternity away, when freezing temperatures and just a few hours of daylight brings the racing season to a halt until the following April.

One would forgive a Norwegian racehorse trainer for complaining about the winters—even trainers living at latitudes far south of Norway tend to mutter and moan about the weather and training conditions of the winter months.

However, Erichsen’s view on training racehorses in Norway in the winter may come as a surprise.

She explains: “In my opinion, our strong winters is one of the particulars with training horses in Norway, but it is definitely one of the benefits. The cold gets rid of a lot of bacteria, and the snow is one of the best surfaces you can train horses on.”

“We use special shoes with studs which prevent the horses from slipping and snow rim pads that prevent snow packing into their feet. The track workers at Øvrevoll are great. They harrow the snow and make it into a nice training surface. It is smooth—and cold. What other surfaces are there that cool the horses’ legs whilst they train?”