Biosecurity Beyond the Barn

WORDS: JACKIE BELLAMY-ZIONS INTERVIEWING: DR SCOTT WEESEIn the equine industry, true biosecurity is hard to achieve because horses move around a lot, and many diseases are always present says Ontario Veterinary College infectious disease specialist Dr Scott Weese. "However, it's still important to try to prevent diseases from entering and to have plans in place to manage any outbreaks." With frequent horse movements, endemic pathogens and emerging diseases, there is a need for improved understanding and motivation to adopt better infection control practices.

Infection control begins in the barn and works best when the focus is pro-active rather than reactive. This includes having an access management plan, proper quarantine protocols for new and returning horses, and training EVERYONE who comes on to the property or handles the horses.

► Access management

Controlling how horses, humans, equipment and vehicles can move into and around your yard are all aspects of access management aimed to reduce the transmission of pathogens.

Access management begins at the entrance, where a training facility may use fencing and gated entries to restrict access to the stables and training areas, ensuring only authorised personnel can enter. Procedures at controlled access points such as hand sanitising and boot cleaning help prevent the spread of infections. Both staff and service providers need to be made aware of any infection control measures in place. Clean outerwear that has not been worn to another barn are also recommended to prevent potential spread of disease.

A sign in procedure can be made mandatory for visitors. A log can be helpful to help trace the problem in the event of a disease outbreak. Providing guided tours can ensure they do not enter restricted areas. Additional signage can let visitors know where they can and cannot go.

Controlled access zones can designate specific areas for different activities, such as quarantine zones for new arrivals and separate zones for resident horses, with controlled access points to manage movement.

► Isolation/quarantine

When horses return home or new horses arrive, such as from a sale, it is a good idea to implement quarantine and/or isolation protocols. Ideally this involves housing in a separate building away from your resident horses, but it may be the end of an aisle with several empty stalls in between.

New and returning horses are kept separate and monitored for at least 14 days. This involves twice daily temperature checks and health checks including watching water consumption, appetite, urination, manure and any signs of illness.

Turn out paddocks should also be away from other resident equines, especially if that includes higher risk horses like broodmares and foals.

Effective quarantine includes using separate equipment for isolated or quarantined horses to avoid cross-contamination. This includes water buckets, feed tubs, grooming equipment as well as wheelbarrows, brooms, pitchforks and other cleaning tools.

Ideally, new and returning horses are handled by separate staff. Otherwise, quarantined horses are worked with last and hands are washed before and after each interaction. Strategically placed alcohol-based sanitisers can also be used. If wash stations are limited, this makes it easier for staff and visitors to follow infection control protocols. Disposable gloves, disposable shoe covers and protective clothing are also best practices. Barn cats and other pets should not be allowed to enter the quarantine area.

If you have a number of new or returning horses in quarantine and one shows signs of illness, it should be further separated into isolation and seen by a veterinarian ASAP. Horses should remain in isolation until cleared by the vet, as the horse may have recovered from clinical signs but still be infectious. Signage once again should alert unauthorised persons at the entrance of any areas used for isolation or quarantine.

► Hygiene practices

Of course, those new or returning horses should be housed in a stall that has been both cleaned and disinfected prior to their arrival. Cleaning involves removing all visible manure, bedding and soil before washing the area with soap and water and then allowing it to dry. Then apply a disinfectant recommended by your veterinarian. All disinfectants have strengths and weaknesses and are best used for specific purposes. Bleach has drawbacks as hard water can affect its effectiveness, it can be inactivated by organic material, and it can be irritating to the horse. Steer clear of pressure washers as they can aerosolise certain viruses.

An often-misused step, if you will pardon the pun, is the foot bath. One cannot just walk through without first going through the same routine as mentioned above, both cleaning and disinfecting. First remove debris from the footwear, including the soles using a brush or hose to get all the dirt out of the treads. Immerse the entire bottom of footwear in the disinfectant and scrub. Following the contact time on the product label is important and a dirty footbath does little in the way of boosting biosecurity. Then wash your hands. Other options include dedicated footwear and disposable shoe covers.

Hand hygiene cannot be overstated as one of the most important infection control measures. Best practices on application time for the soap or alcohol-based sanitiser is 20-30 seconds.

Everyone knows not to share communal water, but it is also important not to become blasé about biosecurity when it comes to filling or refilling water buckets. Submersing a hose from one bucket to the next or letting it touch the buckets can be a free ride for a pathogen looking for its next host. So instead of multi-tasking while filling buckets, one could be enjoying a beverage with their free hand.

Not sharing should extend beyond grooming equipment to tack, pads, blankets, and of course medical supplies like syringes, needles and dewormers.

More disease prevention measures include minimising the presence of rodents and insects by keeping feed secure, eliminating standing water and regular removal of manure from stalls and paddocks and as well as management of manure storage areas.

► Vaccination

Vaccination is a crucial aspect of equine healthcare, but vaccines do not provide immediate protection; it can take days or weeks for a horse to develop optimal immunity after vaccination, so timing is very important. Planning ahead will allow vaccines to be given well in advance of the next stressor such as travelling or competition.

While no vaccine boasts 100% immunity, horse owners can rest assured that they are taking proactive steps to maintain their horse's health, minimising the risk of unexpected veterinary expenses. Vaccines significantly reduce the risk of disease which means if a vaccinated horses does get sick, they will generally experience milder symptoms and recover more quickly.

Working closely with a veterinarian to develop and maintain a vaccination program is an important step for optimal equine health. In addition to core vaccinations, your vet will know what diseases are endemic and emerging in your region or regions you will be travelling to. The frequency of your vaccinations or boosters will depend on a number of factors including special circumstances, such as an extended vector season or even a significant wound if it is incurred over 6 months after a Tetanus shot. The length of your competition season may also necessitate a booster of certain shots to maintain optimal immunity.

► Emerging diseases

Infection control specialist Dr Weese says, "Understanding potential mechanisms of transmission is the basis of any infection control or biosecurity program."

Most diseases in horses are caused by pathogens that mainly infect horses. They can spread continuously without needing long-term hosts (like the equine flu virus). They can remain in the horse without causing symptoms for a long time (like Strangles). Some cause infections that can come back at any time (like Equine Herpesvirus). Others may be part of the normal bacteria in horses but can cause disease if given the chance (like Staphylococci and Enterobacteriaceae).

Horses can spread these germs even if they seem healthy, before showing symptoms, after recovering, or as part of their normal bacteria. This makes it hard to identify which horses are infectious. Some symptoms, like fever and diarrhoea, strongly suggest an infection, but any horse can potentially spread germs. Therefore, it's important to have strong infection control practices to manage the risk.

The most frequently reported diseases in the Northern Hemisphere are:

• Strangles: A bacterial infection caused by Streptococcus equi, leading to swollen lymph nodes and respiratory issues. It is highly contagious and spread through contact. This could be nose-to-nose between horses or via contaminated surfaces or equipment such as: shared halters, lead shanks, cross ties, feed tubs, stall walls, fencing, clothing, hands, the hair coat from other barn pets, grooming tools, water buckets, communal troughs.

After an outbreak, cleaning should involve removal of all organic material from surfaces and subsequent disinfection of water containers, feeders, fences, stalls, tack and horseboxs.

• West Nile Virus (WNV): a mosquito-borne virus leading to neurological issues such as inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. WNV can be fatal and survivors can have residual neurological deficits for a period of months to permanent disability.

• Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE): another virus transmitted by mosquitos. This virus is more commonplace in North America with no recently reported equine cases in Europe. Eighty to ninety percent of infected horses develop acute and fatal neurologic disease.

• Equine Infectious Anemia (EIA): is a blood-bourne virus which can be transmitted by insects, medical equipment or passed from mare to foal in utero. With no treatment or cure, horses confirmed positive by a Coggins test can be quarantined or the rest of their life but are usually euthanised.

• Equine Herpesvirus (EHV): This virus had multiple strains and can cause both abortion and neurologic symptoms. Spread via aerosol particles from nasal discharge or from contaminated surfaces. There are vaccines for respiratory and abortive strains but not the neurologic form of EHV-1 (EHM).

These diseases highlight the importance of biosecurity and vaccination in managing equine health.

In February 2025, Equine Guelph partnered with the Equine Disease Communication Center (EDCC), to help horse owners assess and manage infectious disease risks with the relaunch of Equine Guelph’s Biosecurity Risk Calculator (TheHorsePortal.com/BiosecurityTool). The interactive free tool is full of useful information from quarantine protocols, best practices for cleaning, and easy to understand practical access management tips. In just 10 minutes, you can assess and minimise biosecurity threats for your barn.

“Applying routine and basic biosecurity is the best way to prevent infectious diseases,” says Dr Nathaniel White the Director of the EDCC. “This includes isolation of new horses introduced to facilities, monitoring horses’ temperature and preventing horse to horse contact while travelling and keeping vaccinations up to date. Being aware of disease prevalence using information from the EDCC (equinediseasecc.org) and the updated “Biosecurity Risk Calculator” can help owners use management practices to decrease disease risk.”

► Equine infection control measures during transport

Pre-transport preparations entail more than just having your paperwork in order.

Taking the time to clean and disinfect the horsebox or make sure the horsebox you have hired is always cleaned between loads is of paramount importance. If the horsebox smells like horses, it was not adequately cleaned. Perform a horse health check before you leave the property. It is not worth the gamble to stress a horse with travel when it is 'not-quite right'.

Being particular about your horse's travelling companions is just as important as the cleanliness of the horsebox. Avoid travelling with horses from other locations as being in close quarters increases the risk of picking up an infectious disease. Tie the horse loosely if possible. Horses tied short have less ability to lower their head to clear mucus. Allowing freedom of head movement can reduce stress and the bacterial load in the airways. Similarly, hay nets that are hung high, encouraging a high head position, and introducing dust and debris, can challenge mucous clearance.

Ventilation is another important consideration as improving air exchange can reduce the dust and mold spores hanging in the air. Drafts on the other hand can blow particles around in the horsebox.

Many prefer shipping in leather halters because they will break in an emergency but there is a biosecurity benefit too as they are easier to clean. Bacteria can linger in the webbing of polyester halters.

Biosecurity is just as important on the road and when visiting other venues. Disease is easily spread through equipment sharing. While visiting venues away from home be sure to bring your own broom and shovel for cleaning your horsebox and pack a thermometer along with your tack and other equipment. Clean and disinfect your equipment when you get ready to leave your off-site location.

Upon returning to your stables, the cycle begins again, monitoring horses for possible delayed onset of symptoms.

To ensure effective infection control, it is crucial to maintain a proactive approach starting right in the barn with a plan. Implementing access management, enforcing proper quarantine protocols for new and returning horses, and thoroughly training everyone who enters the property or handles the horses are essential steps. By taking these practical steps, we can significantly reduce the risk of infections and promote a healthier environment for all.

IMPROVING WINTER BIOSECURITY & AIR QUALITY IN EQUINE YARDS

WORDS: DR BERNARD STOFFELEffective biosecurity in equine facilities aims to reduce the introduction and spread of pathogens, dust, allergens, and environmental irritants. During the winter stabling period, these risks increase significantly. A horse inhales over 100,000 litres of air per day up to 200,000 with exercise, and colder months typically bring 20-60% higher levels of fine particles (EEA, 2023).

Reduced ventilation, increased humidity and elevated ammonia all contribute to airway stress, making horses more vulnerable to inflammation, coughing, RAO and even exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage (EIPH).

Conventional disinfectants such as quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), chlorine solutions and hydrogen peroxide remain important for surface hygiene, but they do not address airborne irritants, which represent the primary exposure pathway in enclosed stables. Some disinfectants can also leave persistent residues after drying.

Current DEFRA and EU REACH Annex XVII guidance encourages minimising cumulative exposure to such residues in enclosed environments, especially where horses and yard staff spend extended time.

This has led many yards to explore air-active, residue-free approaches as a complement to normal cleaning.

Recent developments in supramolecular chemistry - specifically the use of cucurbiturils, a class of molecular inclusion compounds - offer a practical way to help manage stable air quality. These structures physically bind and neutralise airborne pollutants including dust allergens, fungal fragments, ammonia-related VOCS and odour molecules. Unlike conventional disinfectants, they do not rely on oxidative chemistry or harsh contact action.

After being sprayed into the air, the molecular cages remain active when they settle, continuing to bind deposited pollutants on surfaces such as numnahs (saddle pads), rugs, partitions, bedding and stable doors. This provides an extended window of benefit during the high-risk winter months.

KEY ADVANTAGES OF THIS APPROACH INCLUDE:

Air-active mode of action in the breathing zone

Continued activity after drying, binding allergens and odour compounds on surfaces

Non-corrosive and non-oxidising, with minimal residue

Safe for use in occupied stables, with no requirement to vacate animals or staff

Together with routine hygiene, these innovatio s represent a shift from purely kill-based methods towards holistic air-quality management supporting respiratory comfort and reducing environmental stress during the winter stabling period.

The results of the survey conducted into the husbandry practices that are adopted in the training of racehorses across Europe

Article by Dr Paull Khan

This article must start with an expression of gratitude to the 141 trainers/pre-trainers who gave of their valuable time to respond to our Survey of European Thoroughbred Racehorse Practices.

The survey was prompted by the review currently being conducted by the European Commission (EC) on animal husbandry, and its specific focus on horses. The EC has engaged its scientific advisors, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), to produce a scientific opinion on the protection of horses, and a technical report on current practices for their keeping. The terms of reference for this work specifically include horses kept for ‘competitive activity’ (eg racehorses). The report is wide-ranging but will also consider the access that horses do or do not have to the outdoors and to other horses, the periods they have at grass, as well as their nutrition and feeding regimes. It will look at how these husbandry practices affect such things as gastro-enteric disorders; it will comment on how horses’ welfare is impacted by such aspects of their housing conditions as air quality, temperature and lighting (including natural light and visual horizon). More specifically, it will look at:

Social needs…..(i.e. access to conspecifics, including in visual, auditory, and olfactory form and including stallions).

and

Outdoor access (or lack of), providing the opportunity for grazing and free movement and including the risks related to…..the absence of an outdoor enclosure.

EFSA’s opinion will be evidence-based and it will examine the available scientific and other literature which has a bearing on the terms of reference it has been given. This research is limited, but what there is gives further clues as to likely areas of focus.

A matter which appears to be a growing area of concern is around the degree of social contact which racehorses enjoy, and whether this is sufficient for their needs. Discussion of this subject often leads to the specific consideration of the length of time horses spend outside their boxes, especially when turned-out and freed of training or racing duties. It is in this context that the expression ‘the other 23 hours’ has quickly gained currency, often evoking censure: the implication being that racehorses are ‘let out’ for just one hour a day.

The organisation Eurogroup for Animals, has pronounced on this issue. Based on a ‘case study’, it concludes: “Looking at the holistic picture and multiple indicators, including animal-based indicators, demonstrates that the positive experiences for a racehorse do not counterbalance the negative experiences. When looking holistically at this Thorougbred Racehorse’s life experiences, it is clear he is not living a Good Life, but rather is having only his basic needs met.”.

In our struggle to retain our social licence, anthropomorphism is, of course, a potent enemy and it is easy to imagine the general public being led to compare the ‘fate’ of the racehorse with that of the prisoner, allowed out of his cell to exercise for just one hour a day.

Time out of the stable is, of course, not the only measure of social contact. Even when in their boxes, there are opportunities for social contact between horses. The degree and quality of such contact is variable, depending on the design and layout of the boxes.

The abstract of a 2019 study Housing Horses in Individual Boxes Is a Challenge with Regard to Welfare (Animals, Alice Ruet, Julie Lemarchand etc) begins in trenchant fashion: “Horses are mainly housed in individual boxes. This housing system is reported to be highly detrimental with regard to welfare….” The study duly concluded that: “…the longer the horses spent in individual boxes, the more likely they were to express unresponsiveness to the environment. To preserve the welfare of horses, it seems necessary to allow free exercise, interactions with conspecifics, and fibre consumption as often as possible, to ensure the satisfaction of the species' behavioural and physiological needs.”

One of the most relevant studies that has been conducted in this area, Racehorse welfare across a training season, a doctoral thesis by Rachel Annan et al, was published in Frontiers in Veterinary Science in 2023. This paper noted:

“Our results suggest that a racing season indeed represents a form of challenge for a racehorse’s welfare state, but that some specific factors—such as opportunities for social contacts and increased visual horizons—have potential to help horses overcome the challenge”.

“If racehorses are expected to work at the upper limit of equine athletic ability, it is important that, overall, they experience many positive experiences in order to ensure a positive welfare balance”.

“Our results highlight the importance of the opportunities for social contact for racehorse welfare. All horses were individually housed in a variety of types of stables with differing amounts of social contact both between, and within training yards. Thereby, 54.1% of horses had physical social contact when stabled, which meant they could at least sniff another horse through a social panel or grill between stables, a low wall or at the stable door. This level of social contact is higher than that reported in the leisure horse population where 39%–44% had physical contact while stabled. In our study, access to physical contact (sniff or head and neck) was associated with more lying down, suggesting a greater level of relaxation and quality of sleep. Indeed, horses are more likely to lie down in a sternal or recumbent position when they feel safe and there are social companions nearby. Furthermore, horses can also only enter paradoxical Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep when they lie down in a recumbent position, making lying down an essential activity. Providing opportunities for social contacts appeared therefore positive for the welfare of the present racehorse population”.

“As a social species, the importance of well-established bonds with known conspecifics has been well documented as an essential welfare need for horses. Our results suggest that efforts to increase social contacts for racehorses have been made within the racing industry and has positive repercussions. However, improvement is still required as the majority of social contacts we observed were still restricted to nose-to-nose contacts, usually through bars. Previous research indeed showed that even if horses are intrinsically motivated to access any level of social contacts, full-body contacts are necessary to the establishment of social relationships. As we observed in our study, racehorses are still mainly housed in individual stables during training, as protection from injury and cross-contamination of pathogens is a major concern. Yet, in 2020, the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities published minimum horse welfare standards, which included “opportunities to bond with other animals as a desirable condition to optimise horse welfare.” The Irish Thoroughbred Welfare Council also included social contact as an important aspect of horse welfare in their recently published welfare principles. Finally, social contact was highlighted as “the best life” scenario for racehorses by stakeholders within the racing industry. Altogether, these elements suggest that pursuing the efforts to increase social contacts for racehorses would be an effective and concrete way to improve equine welfare in the industry”.

Studies such as those above, together with the terms of reference of the EC study, helped us shape our questionnaire, which concentrated on stabling, feeding and turnout (both when in and out of training).

A purpose of our pan-European survey - believed to be the first of its kind - is to enhance knowledge of the current situation on the ground in racing yards across the continent. What are trainers’ practices, and what are the experiences of the horses in their care? Are these static, or evolving?

Beyond this, it is hoped to stimulate thought and discussion among trainers and racing regulators, in order that we, as a sector, can best contribute to the broader discourse which is bound to flow from the EC’s review.

THE RESULTS

We received 141 responses from nine countries: Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland (Republic and Northern), Spain and Sweden.

The vast majority were trainers, but 6 responses (4%) came from pre-trainers. There was a good spread of trainers over the two codes. While half described themselves as ‘predominantly flat’, 27% were ‘both flat and jump’ and the remaining 23% were ‘predominantly jump’.

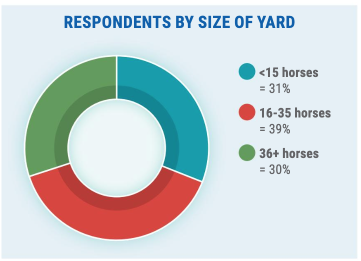

Similarly, there was pleasing representation of all sizes of yard. The survey asked: ‘What is the approximate number of horses you have in your yard at peak season?’ For 31%, this number was up to 15; 39% reported peak totals of between 16 and 35 horses and 30% gave a figure of 35 horses or more.

Twelve yards had 100 or more and five had between 150 and 200.

The figures indicate that, between them, our respondents accounted for over 5,000 horses and over 6,000 boxes.

STABLING

Our responses indicate that, out of the 5,000 or so horses covered, fewer than 150 are stabled in groups. Over 97% are housed individually.

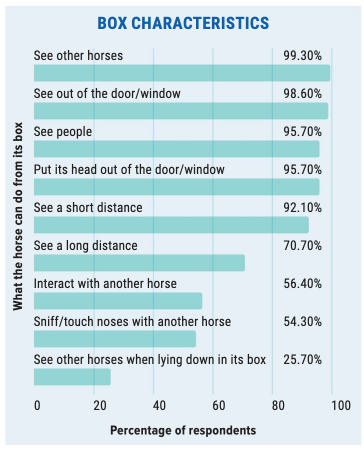

We asked trainers about the design of their boxes, with specific regard to the degree and nature of the contact with other horses that they afforded. Specifically, we asked whether the horse could see out, could put its head out, could see other horses, could do so when lying down (eg through floor to ceiling grills), could sniff/touch noses with another horse, could interact with another horse, could see a short distance (eg to stables opposite), or a long distance (eg a large courtyard or field), or could see people (eg working in the yard). Trainers were asked to tick all those which were applicable. The breakdown of responses is shown below.

Almost universally, trainers’ horses can look out of their box and see other horses. Over 95%% replied that their horses could put their heads out of the box door/window and see people. Seventy per cent said their horses could see a long distance from their boxes. A little over half said their charges could interact with another horse, and sniff/touch noses with another horse. One quarter of respondents had boxes which allowed the horse to see another when lying down.

FEEDING

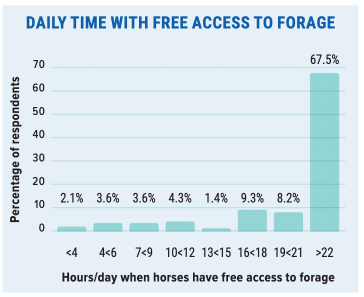

As regards the feeding regime which trainers adopt, we first asked: “What percentage of time do your horses have free access to forage (hay / haylage etc.)?”

Two-thirds of trainers give their horses free access to forage all, or virtually all, of the time. All but 15% give access for at least 16 hours daily.

Question: How many times per day are your horses fed forage?

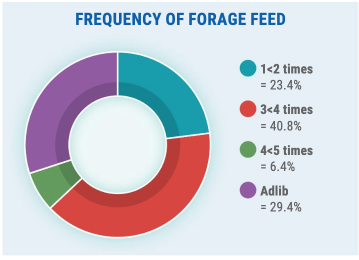

There is a broad spread of practice when it comes to the number of times a trainer’s horses are fed forage. The most popular answer was 3 to 4 times a day (40.8% of trainers). Around 30% of trainers forage-fed their horses on an adlib basis, with around a quarter of trainers feeding once or twice daily. A small percentage (6.4%), fed four or five times a day.

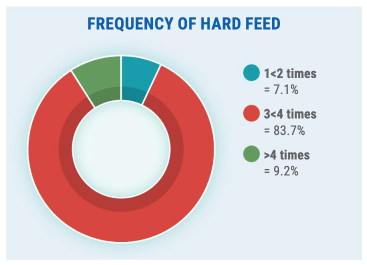

Question: How many times per day do your horses receive hard feeds?

There is greater consensus when it comes to frequency of hard feeds, with 84% choosing their feed their horses three or four times a day. Those who feed less frequently and those who feed more frequently are roughly evenly split.

TURNOUT

We defined ‘turnout’ as more than 15 minutes on a field or pen. We asked “What percentage of your horses in training are turned out daily when weather conditions allow?”

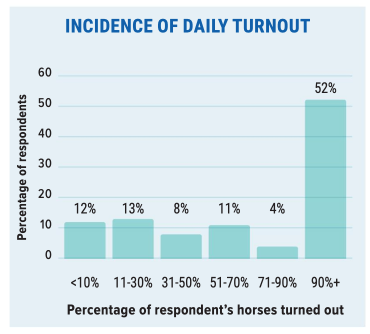

More than half of respondents said they turned 90% or more of their horses out every day. Fewer than one trainer in eight answered that they turned out less than 10% of their horses daily.

We turned next to the typical duration of turnout, asking: “On each occasion, for how long would your horses typically be turned out?”

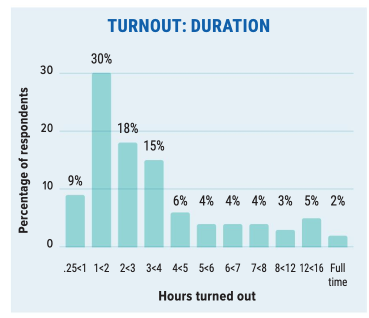

As can be seen from this chart, the most popular duration was 1 to 2 hours, with significant numbers of trainers selecting 2 to 3 hours and 3 to 4 hours. For more than a quarter of trainers, turnout spells of between 4 and 24 hours were the norm.

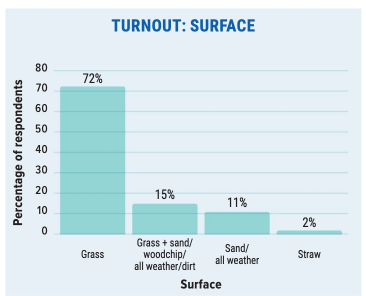

The great majority of trainers turn their horses out on grass. For 72%, this was the sole surface, with a further 15% divided between grass and another surface, variously described as ‘sand’, ‘woodchip’, ‘all-weather’ or ‘dirt’. Where more than one surface was used, the reason was seasonal and weather-related, with grass favoured in summer and the alternative surface in winter. But one trainer’s choice was based on the horse’s gender, answering thus: “Fillies on very large grass fields in groups//colts on 400qm sand paddocks”. One respondent elaborated further: “Mainly grass or sand or inside round pen (sand mixed with fibres - great to have a roll, it's soft), indoor manege = sand surface”.

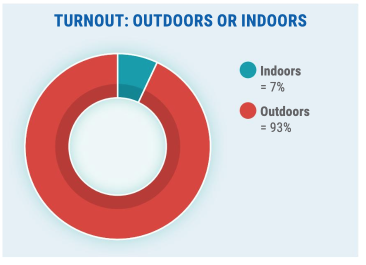

Ninety-three percent of respondents turned their horses out outdoors.

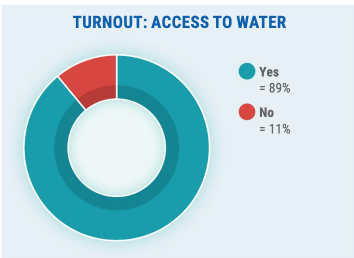

Almost 90% of trainers reported that their horses had access to fresh water when turned out.

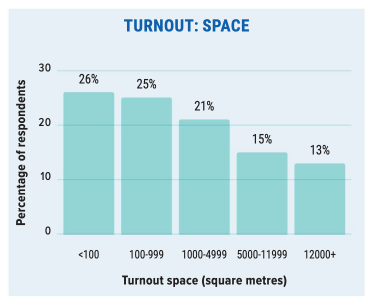

We then asked: “What is the approximate area (square metres) of the space in which they are turned out?” There was great variability in the answers here, as shown by the chart.

(To help interpret these figures, it might be noted that 1 acre is around 4,000 square metres, and a hectare is 10,000 square metres).

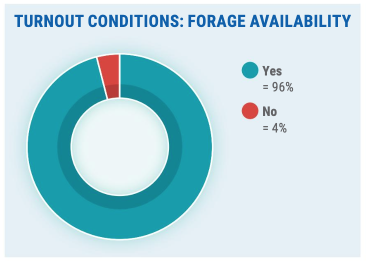

Almost universally, when asked: “Do they have forage availability (grass, hay, etc.)?”, trainers answered affirmatively.

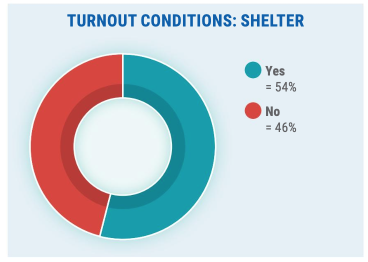

A majority (54%) of trainers provide the horses which they turn out with shelter against the sun or rain.

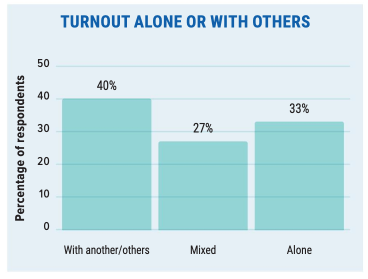

We next asked whether trainers turned their horses out alone, or with others. Two thirds of the replies indicated that at least some horses were turned out with others.

Where there was a mixture of solo or accompanied turnout, the most common reason cited was gender based, with fillies and geldings, but not colts, being trusted to coexist peaceably. For some, the decision was made on the basis of the horses’ character or friendships with other individuals. Several trainers set a limit on the numbers put out together.

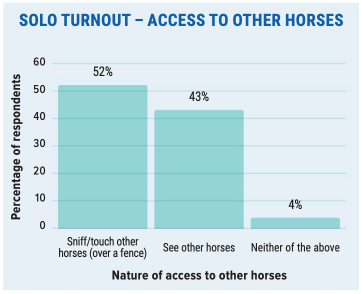

Trainers were asked: “If they are turned out alone, do they have the opportunity to (a) sniff/touch other horses (over a fence), (b) see other horses or (c) neither of the above”. It can be seen that all but 4% of trainers give their solo turned-out horses the chance of some contact with others, with a majority allowing them to sniff and touch another horse.

TIME OUT OF THE YARD

One aspect of a racehorse’s life that can easily be overlooked is their time spent out of training. We sought to build up a picture of racehorses’ experiences during this ‘downtime’, when not in training and therefore not in their trainer’s yard. We asked: “When out of training, are you aware of any instances where horses you train are not either at grass 24 hours a day or at least part of any day (stabled at night for example)?”

Almost universally, it was reported that, when out of training, horses are at grass for all or part of each day, other than when injured or ill. Many yards reported that they come in at night, some said that they would be housed in inclement weather.

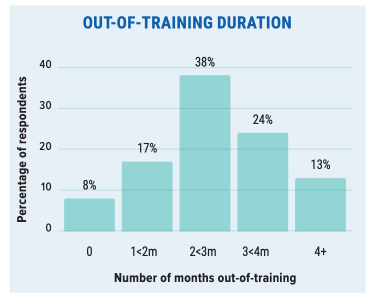

Next, we enquired: “While out of training, typically, for how long each year would your racehorses not be housed in the yard?”

For the great majority, this ‘downtime’ lasts for one to three months. One respondent explained: “It varies a lot. Every horse is an individual and their holidays and how they are turned out is based on their health and mental well-being”. Where trainers specified a typical length of time out of the yard, the spread of responses is shown in the chart below.

Thirteen per cent of trainers stated that there was no time out of the yard. Around one quarter gave a figure of 1 to 2 months, with 38% saying 2 to 3 months. One quarter of trainers reported ‘down-time’ of three months or more.

EVOLUTION

We enquired: “If future legislation were to require horses to be turned out, please select the option that best applies to your situation:

It would be impossible to accommodate this.

I could accommodate this, but only after making extensive and costly adjustments.

No problem, I have the facilities to do this already”.

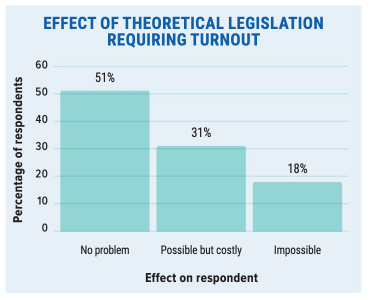

Half of the trainers explained that they could cope without problem with any such theoretical future legislation. Thirty-one per cent could do so, but that it would require costly and extensive changes. Eighteen per cent replied that it would be impossible for them to comply.

We were keen to ascertain the extent to which trainers were settled and static in their approach to such matters as box design and turnout, or, on the other hand, were making changes in these areas. We asked: “Have you recently changed your practices in any way relevant to the above (for example, modifying your boxes or turnout regime)? If so, please describe what you have done”.

No fewer than 30% replied that they had modified their practices in recent years in regard to their housing or turnout regimes. The changes they cited were many and varied. Here is a selection of their comments:

Increasing air, light and social contact in the boxing, adding a paddock and utilising a forest riding area for turnout.

Increasing size and modifying box design so as to allow mutual visibility (eg adding a window in the back wall, or contact/interaction with others

Taking out the top grills to allow grooming and touching

Increasing ventilation in the stable block

Bigger boxes and daily turnout (suitably rugged if inclement weather)

Increasing the number of horses turned out in pairs.

Creating more opportunities for colts to be turned out.

I created 3 paddocks and a large meadow for their recovery and well-being.

I have changed from having water buckets to automatic drinkers in the stables. I previously preferred to know how much water a horse drank on a daily basis but I have not had any issues since switching.

We’ve put webbings in our boxes (American style) to have open doors, more sunshine and better airflow in the boxes.

We built 400qm sand paddocks to bring all colts out 7/7 for at least 1.5 hours;

(fillies on big fields in groups).In the past only groups of 2 horses were outside for 2 hours; now all horses are together outside in two groups (racehorse/riding horses and old racehorses).

Lack of additional space was a common problem, so some initiatives were aimed at making improved use of the space available: “we constantly move the pens and rest the paddocks, harrow, roll and re seed when necessary”, or converting areas especially prone to muddying into all-weather areas: “Added more all weather areas. Our rainfall is high so fields get muddy quickly which then causes the horses to be miserable”. Also “we work hard to find pre-trainers who can turn horses out”.

However, some trainers were keen to point out that turnout is not a simple panacea, as is reflected in these comments:

“Four years ago we started turning the horses out for 2 hours after exercise. Not all horses will settle turned out though and have been upset or even injured themselves”.

“Geldings and fillies in training are turned out in pairs to minimise risk of injury. We used to turnout in larger groups of four but risk factor was higher. We don’t turn out colts in training - risk of injury to themselves is too high. Colts can be turned out individually in pen or lunge ring if needed”.

“More turnout places available in the past but it is far from certain that the horses have benefitted from this”.

Finally, in this section, we enquired as to future plans: “Would you consider doing so in the future? If so, please describe what you would consider doing?”

Almost half of those who responded replied in the affirmative. Here are some examples of their plans:

“Build more paddocks for our colts to be able to keep each one out for longer”

“Get a loan to do fencing on the 10 ha I have bought. Safety fencing. Create more individual paddocks, around the yard, to turn horses out for a few hours a day. Create better access to the private ponds, to walk through/ play. Swim? Re-installing solarium, a treadmill.”

“If I had the money, I would prefer all my horses to live outside as it’s their nature to live in groups. It keeps them relaxed and happy.”

“Going forward I hope to continue to have a large window area in each stable and I would choose gates rather than standard doors as far as is practical.”

“I am considering altering the partition walls in my stables to allow horses to see each other and interact with the horses adjacent to them. The cost of this is a factor though.”

“I think turnout is very important and a great way to keep a horse fresh and happy. If it were possible, all my horses would have some turnout each day”.

Again, though, a few trainers struck a cautionary note about the concept of turnout:

“If find there is always one or two that cant be turned out due to injury or they are a danger to themselves therefore a legislation would have negative impacts on horses welfare”.

“We have turnout but would struggle to turn every horse out every day, the reality is not every thoroughbred is relaxed and settled turned out when in full training. We have a variety of box settings and they are all large, with direct sight of horses again some horses are happy with lots of opportunity to interact with others whilst other prefer a more isolated setting”.

“There are pros and cons to turnout and the fact that people have come to perceive turnout as a principal requirement of good husbandry, doesn't necessarily mean it is right”.

CLOSING REMARKS

The implications of the EC’s review should not be over-stated. We are led to expect that what will result will be guidance, rather than new legislation. But, even if that proves to be so, individual governments may choose to introduce national legislation. Some European countries already have laws which require turnout. Norway requires horses to be turned out/exercised for a minimum of two hours daily; Sweden and Finland mandate daily turnout without specifying the duration. Sweden requires conditions under which horses can exhibit ‘natural behaviour’, (ridden exercise does not count as ‘turnout’).

It is important that racing understands the realities of the way our horses are kept and looked after and hopefully this survey provides a step forward in that aim. The survey highlighted the weight given by trainers to individual care regimes, reflecting a widespread recognition that horses are individuals, with different needs and preferences. What appears very clear from the responses is that European trainers are indeed sensitive to the welfare needs of the racehorses in their care, and are far from resistant to considering where further improvements might be made. This should not surprise us, on the basis that a happy racehorse will be one who will perform better on the track and therefore it is in trainers’ own interests to provide the best possible environment for their horses. It may well be that this flexibility will prove critical in the long-term retention of our social licence.

Promoting 'Best Practice' and why this is important to the outside world

Article by Paull Khan

Complete the survey now at: www.trainermagazine.com/survey - Closing date August 15th 2025

There has perhaps never been a time when it is more important for European trainers to be aware of what is happening politically in Brussels.

It is likely that, by now, readers will be aware of the review being undertaken of the European Union’s laws on animal welfare. The EMHF has, for some years now, been keeping a close watch on developments with the first strand of this review – that relating specifically to welfare in transport. We have been making representations – in writing and by visiting key decision-makers in the European Commission and Parliament – in order to try to ensure that well-intentioned legislative change does not have unintended consequences, not only for our industry, but for our horses themselves. Wherever possible, we have sought to join forces with our sister organisations, to present a unified front across an industry whose political influence is all too often weakened by internal differences.

For the most part, these efforts have borne fruit. Thankfully, the Commission’s proposals for the new laws would, if adopted, give us the continued ability to transport our racehorses in the frictionless way that we have enjoyed for decades and which we doubtlessly take for granted. However, despite specific requests to allow the same freedoms to horses being travelled for breeding or to go to the sales, those journeys have not been included in the Commission’s plans. We continue to fight, alongside the European Federation of Thoroughbred Breeders Associations and many others, for the inclusion of breeding and sales – if we fail, there will be devastating impacts.

There is much less awareness of the second strand of this EU review – and this one threatens to have yet more far-reaching implications for trainers and the way they operate.

This second focus is on the keeping and protection of animals – their husbandry. Work is just beginning on this workstream, but already the Commission has given a strong hint as to the areas that it will be looking into. The review covers a broad range of animals, but the Commission has asked the body to which it turns for scientific advice in these areas – the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) – for a scientific opinion specifically on the protection of horses and other Equidae. The Terms of Reference it has given EFSA are illuminating and arresting.

First, they make clear that EFSA should specifically consider horses kept for breeding, and also ‘working’ horses, which are to include those kept for competition (eg. racehorses). They will be reviewing the most common husbandry systems in place and then identifying welfare consequences of the above and making recommendations to prevent or mitigate those welfare consequences.

For example, EFSA will be assessing, from a welfare perspective, minimum space allowances for the boxes in which horses are housed, the air quality, temperature and lighting in those boxes, the degree to which they can see, hear and smell other horses and the amount of outdoor access and opportunities for grazing and free movement that horses are allowed. They will also be looking at the nutrition and feeding strategies that are used.

They will be considering locomotory, gastro-enteric and metabolic disorders that are found in horses and identifying ‘animal-based measures’ by which those disorders may be identified.

In relation to training, they will be looking at the age at which horses may start to be trained, the temperatures in which training takes place and whether there should be a maximum and the duration of effort and whether there should be a minimum resting period. Practices such as gelding and thermocautery of the limbs (firing) will also come under the spotlight.

In the breeding arena, they will be doing similarly with gestation and weaning conditions, including the age at which weaning takes place, the age of a mare when she is first bred, the number of gestations a mare has and whether there should be a maximum, the period of time between pregnancies and whether there should be a minimum and the practice of Caslick’s procedure.

A presentation on the tasks that EFSA has been set can be found at trainermagazine.com/efsa.

While EFSA has been given until the end of next year to deliver its report, and more time will obviously pass before legislation is agreed and introduced, it is never too early for industries affected to start preparing.

The EMHF is keen that trainers (and others, including breeders) are aware of this activity and is grateful for the opportunity to publicise it through this magazine. Trainers should be given the chance to consider the possible implications of this, to reflect on their own practices and to give thought to whether and in what ways they might look to adjust those practices to ensure maximum welfare benefits for the horses in their care.

It is important that, collectively, we are aware of how things currently work. What are the husbandry practices that are adopted in the training of racehorses, across Europe?

To answer this, we are launching this Questionnaire, which readers are strongly encouraged to complete and submit.

This magazine offers a good way to help start discussions, to pool ideas and expertise so that our industry can, in due course, speak to the European institutions in as informed and measured a way as possible.

How trainers promote best welfare practice across Europe

"Mens sana in corpore sano" - is a well known Italian phrase which translates to “a healthy mind in a healthy body" is a fundamental principle for every athlete, and racehorses are true athletes of the sporting arena. Just like their human counterparts, the performance of a racehorse depends not only on their physical condition but also on their mental well-being. The issue of animal welfare in horse racing is not just a matter of ethics or sensitivity, but the foundation upon which the integrity of the entire sport rests.

The concept of equine welfare extends beyond the mere absence of disease or injury. It concerns the quality of life of the horses, including their daily treatment, living conditions, access to open spaces, appropriate nutrition, and the ability to express natural behaviours. Moreover, it includes ethical training practices that respect the animal's physical limits, avoiding bad training and stress.

In the context of racing, equine welfare is scrutinised not only by industry insiders but also by the public and animal rights activists. Our focus in this section of the article is on the evolution of welfare practices in the leading countries of European horse racing: Great Britain, France, Ireland and Germany.

The goal is to understand not only the current state in terms of equine welfare but also to identify trends and areas for improvement, reflecting on the importance of an ethical and responsible approach to these extraordinary athletes.

GREAT BRITAIN - HORSE WELFARE BOARD (BHA)

The Horse Welfare Board, inclusive of representatives from the BHA, racecourses, and horsemen, unveiled a five-year welfare plan in 2020 to elevate horse welfare in British racing. This plan is dedicated to ensuring a "life well-lived" for racehorses, with a focus on traceability, safety, well-being, alongside initiating the industry's most extensive data project. It targets enhancing health care practices, ensuring lifelong responsibility, reducing injuries, and fostering public trust through transparency and ethical practices. Additionally, the strategy commits to developing a Code of Ethics and advancing veterinary care and injury prevention. Importantly, the implementation team is collaborating with the industry on 26 strategic projects, backed by funding from the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) since 2019 and a recent £3 million grant from the Racing Foundation, to realise these goals.

In the array of projects undertaken by the Welfare Board to bolster safety and uphold equine welfare standards, there are a few that stand out as being exceptionally cutting-edge, such as the: Thoroughbred Census, Equine Vision Project, Data Partnership.

Thoroughbred Census

The project aims to enhance the traceability of retired thoroughbreds, enabling better support for owners and the adaptation of welfare initiatives by British Racing and Retraining of Racehorses (RoR). It involves a six-month census, in partnership with RoR, collecting detailed information on retired racehorses to improve aftercare and respond quickly to equine disease outbreaks.

Equine Vision Project

“We try to look through the horses’ eyes” - Mike Etherington-Simth

In 2017, the BHA and Racing Foundation funded research into equine vision to enhance hurdle and fence safety. Horses, seeing fewer colours than humans, struggle to distinguish between hues like red, orange, and green. The study assessed the visibility of orange markers on racecourse obstacles against alternative colours, considering how weather conditions affect perception.

Data Partnership

This project seeks to enhance racehorse safety and welfare by analysing risks and factors leading to injuries and fatalities on racecourses and during training in Great Britain. It utilises extensive data on races and training practices, employing advanced statistical models to identify risk factors. The initiative, in collaboration with industry stakeholders, aims to provide evidence that informs decisions and measures to minimise risks, directly contributing to the betterment of racehorse welfare.

FRANCE - FRANCE GALOP

France Galop is deeply committed to promoting high standards of horse welfare, aligning with the 8 principles outlined in the "Charte Pour le Bien-Être Équin". This commitment is evidenced through various initiatives, including the inspection of facilities by France Galop veterinarians for new trainers who have acquired their flat racing licences. These checks, part of the certification process, aim to ensure that the infrastructure is suitable for housing horses. In 2021, a total of 410 training centres were inspected by the veterinarians of the Fédération Nationale des Courses Hippiques. The vets also check for prescribed medications and substances on site, adhering to a “zero tolerance” policy.

IRELAND - THOROUGHBRED WELFARE COUNCIL (HRI)

“They have horse welfare right at the forefront of everything they do and I would say they are doing a very good job” Joseph O’Brien

In 2021, the Irish Thoroughbred Welfare Council was assembled to act as an advisor to the Board of HRI and assist in devising policies on welfare matters. HRI gathered 60 industry participants in a co-design project to create a manual called “Our Industry, Our Standards,” aiming to establish a system where welfare standards are verified and measured. These standards include good feeding, good housing, good health and good well-being. Additionally, the Thoroughbred Council is collaborating with IHRB, Weatherby’s, and the Department of Agriculture to create a traceability system that will ensure every horse always has a known link to the responsible person.

Best-Turned-Out League

To promote and encourage the implementation of good animal care and welfare practices, HRI has introduced the “Best-Turned-Out League,” which aggregates these prizes from across the country into a league table with substantial prizes from six different categories, highlighting the impressive standards maintained across the industry. The primary caregivers, who are often lifelong careerists, are our industry employees.

GERMANY - DEUTSCHER GALOPP

Deutscher Galopp, has notably advanced equine welfare within racing in recent years. Not only has it raised the quality standards of horse care within stables, monitored through surprise veterinary checks, but it has also started to develop an intriguing project that monitors the physical development of racehorses.

Physical Maturity Check for 2-Year-Olds Before Training

Deutscher Galopp has implemented regulations requiring that every horse must pass specific veterinary checks. These checks are designed to ascertain sufficient physical maturity before a horse enters into training. A second assessment is conducted shortly before the horse can start in a race, to confirm its physical fitness for competition.

For this section of the article, we canvassed opinion from a selection of industry professionals for their perspectives on issues related to equine welfare.

Q: What role does horse welfare play in your training practices and what specific measures do you implement to safeguard the physical and mental well-being of the horses?

"The welfare of my horses is central to me; it is the most crucial element for the success of my business” asserts Seamus Mullins, a sentiment unanimously echoed by all interviewees who have long regarded animal welfare as a key factor from the outset of their careers in the racing sector. When delving into the practicalities of ensuring each horse's welfare is honoured, Joseph O'Brien highlights the significance of tailoring care to individual needs. "It's crucial not to generalise, as what satisfies one horse might not suit another," he explains. This underlines the necessity of adapting training and rest schedules to cater to their unique preferences and inclinations, guaranteeing their well-being and happiness.

Luca Cumani, who since retiring from training has remained active within the industry, including a term as a director of the BHA and as a pre-eminent breeder emphasises the importance of observation to understand each horse's psychological capabilities and preferences.

Seamus Mullins discusses the regular turnout of horses in individual paddocks while ensuring they are always in association with other horses. The stables are varied to suit different preferences, emphasising the need for regular updates to training methods and facilities to keep the horses in the best condition possible.

Peter Schiergen, Nastasja Volz-Degel, and Alessandro Botti all share this commitment to horse welfare, implementing daily routines, wellness programs, and training methods tailored to the individual needs and physical aptitudes of each horse. They focus on creating a comfortable environment for the horses, using modern facilities such as solariums, water treadmills, and magnetic blankets for massage, highlighting a collective effort to maintain high welfare standards in the racing industry.

Q: How do you educate your staff or team members about the importance of animal welfare?

"I always said to the riders: the relationship with the horse you ride should be viewed as a partnership, akin to that with your wife or daughter, and should be treated with the same respect and care" Cumani explains with a touch of warmth. The stable staff plays a pivotal role in the implementation of animal welfare, which is why, as the interviewees emphasise, it's crucial to focus on their education and enhance their knowledge to the fullest. "We want our staff to become better horsemen," states Schiergen.

Beyond the training provided internally within their stables, some trainers, like Alessandro Botti, with the support of AFASEC (the Association de Formation et d'Action Sociale des Ecuries de Courses - which roughly translates to Association for Training and Social Action of Racing Stables), have decided to offer courses in equine ethology led by experts brought in from outside. This initiative not only sparked significant interest among their staff but also led to an improved approach to working with horses.

Q: The risk of injuries is an inherent component in all sports, including horse racing. What is your opinion on this statement, and what specific actions do you take to minimise the risks?

"Risks are everywhere, especially in competitive activities, whether involving humans or animals, there's a significant element of risk," are the words of Cumani, which also resonated with others we interviewed.

The consensus is that, unfortunately, injuries are inevitable despite efforts to minimise them through practices and care that respect the physical state of the horse. "We try to minimise the risks by checking every horse before a race and during training, we never push the limit of a horse if he isn't ready enough” underlines Schiergen, “we have to get the message across that we are doing all our best to minimise the risks at all accounts”, adds Mullins.

Q: What role do you believe transparency plays in communicating to the public the importance placed on the welfare of racing horses in daily activities, and how do you ensure that this information is effectively shared with the general public?

“There are fewer and fewer people growing up with animals and in farming, and as a result, this is why we need to show through platforms what we do because things we take for granted, someone who has never been to a racing yard may not realise what happens,” says O'Brien. He adds, “It is important to give people access to behind the scenes, and this is why we try to be quite active on social media and encourage people to come to our yard, so that they realise the amount of passion that staff puts in their daily work.”

Public involvement, to make them part of the daily practices of stable life, is crucial, as our interviewees from various parts of Europe maintain. Thanks to numerous activities promoted by the racing authorities of the interviewees' respective countries, Open Day events allow the public to participate in stable life.

Many trainers, like Seamus Mullins, have noticed a significant increase in participation in recent years, “Ten years ago, participation in the UK was about 100, while in 2023 it was more than 500. Moreover, people who participate often express surprise at how well race horses are treated.” However, all the trainers, like Alessandro Botti affirms, it is necessary to increase content on social media, to give the possibility to everyone, every day and in every part of the world, to participate in the daily life of horses in various stables.

Q: What do you think will be the future trends in horse welfare in Racing in the coming years?

All the trainers interviewed are convinced that the standards of equine welfare in racing are already very high. However, they unanimously believe that social pressure from activists will continue to grow, making it necessary to increase transparency and public engagement. Joseph O'Brien emphasised the importance of education: "What I think really has to be put to the forefront is educating people who are not involved in racing; this will be the biggest challenge."

Given the insights on how Racing Authorities operate in terms of Horse Welfare and the daily interest and commitment of trainers, the trend seems to be very positive and reflects very high standards. It is essential, however, that countries collaborate with each other to inspire one another, further improving equine welfare practices, as Helena Flynn, the British Horse Welfare Board Programme Director emphasises "We love these animals and do our best to ensure they are protected, and thus it would be beneficial if the results of various state projects could contribute to inspiring everyone internationally." Therefore, the issue of equine welfare in racing is a complex mosaic of care, respect, and dedication towards the thoroughbred racehorse. Recognising and acting for their welfare is not just a moral duty but the foundation on which to build a fair, sustainable, and most importantly, animal-respectful racing industry.

“It’s a struggle…” The mental wellbeing of trainers and how to support them.

Article by Rupert Arnold

Training racehorses is a stressful occupation. There’s nothing wrong with that - until there is. In today’s world, mental health is front of stage in conversations about occupational health. Though horse racing might often appear to lag behind more progressive parts of society, attention is increasingly being focused on its participants’ capacity to withstand the stresses of a busy, challenging life where performance is in the public eye.

In Britain and Ireland, jockeys have been the first sector to benefit from support structures instigated by their trade associations and governing bodies. They have been encouraged to speak publicly about the causes of depression, anxiety and substance dependence, and in this way have begun to erode the stigma that stifles potentially healing conversations. A pathway has been opened for trainers to follow.

Three racing nations have spearheaded the research on trainers’ mental health. The first studies were conducted in Australia in 2008 by Speed and Anderson on behalf of Racing Victoria. It’s findings that “two-thirds of trainers never or rarely had one day off per week”, and “Trainers also face increased pressure from owners (e.g. pressure to win competitive races), shoulder the burden of responsibility for keeping horses healthy and sound, as well as financial difficulties” will strike a chord with trainers across all racing jurisdictions and sets the precedent for other research.

In July 2018, again in Australia, research on “Sleep and psychological wellbeing of racehorse industry workers” surveyed Australian trainers and found “Trainers reported significantly higher depression and anxiety scores compared with other racing industry workers, racehorse owners, and the general population. They had less sleeping hours and higher daytime dysfunction due to fatigue.”

Simone Seer’s University of Liverpool MBA dissertation of September 2018 “Occupational Stressors for Racehorse Trainers in Great Britain and their Impact on Health and Wellbeing” (supported by Racing Welfare) used qualitative research via unstructured interviews from which themes were analysed to identify patterns and differences between trainers’ experiences.

“Examples included business and finance worries, bureaucracy, the rules of racing, the fixture list, a lack of resources and busy work schedules, managing stressful episodes with racehorse owners and staff and in balancing emotions. The most dominant stressors were those that were felt to be out of a participant’s control and particularly related to racehorses: keeping horses healthy, free from injury, disease and illness, and the pressure to perform in relation to both the participant and their horses…participants were found to be engaged in intensive emotional labour combined with long work hours and busy schedules resulting in a ‘time famine’. All participants had experienced abusive messages by voicemail, email or social media.

“Participants reported mental ill health symptoms brought on by emotional toll, sleep deprivation, insomnia and isolation resulting in outcomes such as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, low confidence and recurrent headaches.”

In 2021, following the watershed of the Covid-19 pandemic, research on Irish racehorse trainers by King et al published in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science examined the “prevalence and risk factors” associated with racehorse trainer mental health. Among their headline findings were some familiar features:

“A prevalence of symptoms associated with common mental disorders was identified. Specifically, depression (41%), adverse alcohol use (38%), psychological distress (26%), and generalised anxiety (18%).

“Career dissatisfaction, financial difficulties, and lower levels of social support increased the likelihood of meeting the criteria for depression, psychological distress and generalised anxiety.”

As Ryan McElligott, Chief Executive of the Irish Racehorse Trainers Association, says: “Training is a tough business. Even the top trainers lose more often than they win. It’s extra competitive so fear keeps training fees down while costs are increasing…it’s a struggle.”

Away from the published science-based research, we must rely on anecdotes to get a picture of the experience of trainers in other European countries.

Perhaps surprisingly, no studies are available on the situation in France. Gavin Hernon, who represents the Association des Entraineur de Galop (AEDG) at the European Trainers Federation (ETF), suggests this may be because France Galop sees itself primarily as a regulator so wouldn’t include trainers’ health and well-being in its remit.

Gavin reports that trainers in France share the same pressures as colleagues in other countries. He says, “A major factor is the high financial cost of doing business. Well-funded prize money may cast a rosy glow across the sport, but this leads to trainers relying on their percentage to make a profit. It also gives them an incentive to own more horses than is the case in other countries. The combination becomes toxic if the horses are not winning, creating a culture of performance anxiety.”

According to Gavin, a common response to the occupational pressure is for trainers to shut themselves away and bottle up their true feelings. This belief is endorsed by Tom Luhnenschloss, the ETF representative in Norway. “Trainers are living in a bubble”, he explains. “Trainers have a certain mentality. Their life is very repetitive, they put their heads down and carry on, without sharing their problems. There are a lot of hidden issues.”

In the smallest racing nations, the subject of trainers’ mental health may not be enough of a priority for specific attention. Karin Lutmanova in the Czech Republic points out “The problem definitely exists, but I do not think anybody has capacity to care about it. Our racing has so many other crucial and elementary problems such as funding, closure of the main thoroughbred stud, and a decrease of racehorses and racing days.”

So there is a consensus that racehorse trainers are susceptible to particular forms of mental health conditions. The obvious follow-up question is, what can be done to support trainers facing these conditions?

At first glance, there seems to be a gap in racing’s provision for trainers. On governing body and charity websites it isn’t difficult to track down welfare/wellbeing support for jockeys and stable staff, less so for trainers. As Tom Lunhenschloss observed, “There is no one to catch you when you fall.” However, further investigation reveals that initiatives are underway.

From a European perspective, Britain and Ireland are adopting slightly different approaches.

Having contributed extensively to the research in Britain, the National Trainers Federation was keen to collaborate with Racing Welfare, the Jockey Club charity that aims to support the workforce of British racing and backed the research. Simone Sear’s paper concluded that “a bespoke, confidential service should be designed in order to support this workforce to gain insight and build resilience… and will need to provide support across a range of issues such as mental health, physical health, sports psychology, business management, HR and legal advice, financial assistance and time management.”

An informal arrangement between Racing Welfare and the NTF began in 2020 with referrals being made via both parties to Michael Caulfield, a sports psychologist with deep connections to horseracing through a previous role heading the Professional Jockeys Association. Racing Welfare also set up the Leaders Line, a centralised structure for supporting people in management positions. Neither of these initiatives achieved a breakthrough in terms of reach and recognition.

Drawing on Racing Foundation-funded research by Dan Martin at the Liverpool John Moores University, the NTF, through its charity Racehorse Trainers Benevolent Fund (RTBF), began working on a different approach inspired by Dan’s recommendation:

“Create a trainer-specific referral system, exclusive to trainers and separate from Racing Welfare, for mental health support. Given the multiple roles of the racehorse trainer, the support should provide organisational psychology, sports psychology, counselling, and clinical support. Former trainers should be considered to receive training to provide some of this support.”

The twist is that instead of building something and expecting the people to come, the RTBF model was about outreach – creating a network of knowledgeable and empathetic people to be visible in the trainer community, starting the conversations that trainers, by their own admission, were unlikely to reach out for on their own.

Michael Caulfield and David Arbuthnot, whose career as a trainer spanned 38 years and who later undertook counselling qualifications through the NTF Charitable Trust, were recruited to go out and about, chatting to trainers in the Lambourn training centre and surrounding area and at race meetings and bloodstock sales.

Harry Dunlop, a former trainer and recently recruited trustee of the RTBF, explains, “It’s well known that however serious the problem, taking that first step to ask for support with a mental health issue is hard to take. People are afraid to show what they perceive as weakness. By getting Caulfield and Arbuthnot into the places where trainers circulate in their daily working lives, we hope to break down barriers and give trainers a chance to share their problems. That might be all it takes to lighten the load. Or it might lead to scheduling a one-to-one at another time.”

Set up as a six-month pilot from July 2023, this initiative has already expanded to Yorkshire in the North and Newmarket, with trainers Jo Foster and Chris Wall respectively providing the support. Initial response from trainers was amused scepticism but this proved to be a superficial reaction. Very quickly, on a private and confidential basis, trainers have begun opening up to members of the support team. One-to-one sessions were scheduled. Trainers who admitted to putting off seeking help, contacted one of the team for a conversation. Thankfully, there has not been a rush of acute cases of serious mental health pathology. But there is clear evidence that “Trainers just want someone to talk to” as Michael Caulfield describes it. It’s worth noting that Caulfield warns against medicalising all the mental health conditions experienced by trainers. “There is a world of difference between a clinical mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and being overwhelmed by the weight of responsibility and/or despair brought on by sheer exhaustion. Most of the time people need an outlet to vent their worries, and more sleep.”

The need for someone familiar to lend a friendly ear is confirmed by Ryan McElligott. “Trainers are a traditional cohort; they have rather conservative values. They don't like to admit they are in trouble; they worry that it's a sign of weakness. It's a close-knit community so generally the first call for help would be to people close to them.” McElligott says the Irish trainers are fortunate to have two sources of support – the Industry Assistance Programme, which gives access to counselling and therapy; and the availability of Jennifer Pugh, the Senior Medical Officer for the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board. He describes her as “a prominent presence” at race meetings, and clearly trainers feel able to communicate with her.

Pugh contributed to the “prevalence and risk factor” paper mentioned above. She points out that with a background as an amateur rider, coming from a training family, and having worked as a racecourse doctor, she was already a recognisable person before taking on her present official role. The need for access to trusted figures appears to be a common factor in effective mechanisms of support.

The Industry Assistance Programme sits under the umbrella of Horse Racing Ireland’s EQUUIP service, described as ‘The People Behind the People’ in the Irish Horse Racing & Breeding Industry. One of its three offers is “health and wellbeing services for everyone who wants it.” As the British experience shows, encouraging trainers to make use of the formalised support system is not straightforward. Though predating EQUUIP’s creation, the Irish research indicated that “only a fifth of trainers had sought support for their personal and emotional problems.”

For this reason, Pugh endorses the social support approach. She says there is a plan to recruit wellbeing “champions” for people to approach out in the community. And having learned much more about trainers’ mental health through the strong communications established to manage racing’s response to the Covid pandemic, a programme of support is being worked on so that trainers’ needs are given the same importance as for jockeys and stable staff.

For a major racing nation comparatively rich in resources, some recognition of the psychological challenges facing trainers might be expected in France. After all, on its website France Galop lists “Ensuring the health of its professionals” in its responsibilities. It goes on to refer only to jockeys and stable staff. Other than redirecting fines levied on trainers under the disciplinary system towards support for retired trainers, France Galop makes no provision for the welfare of trainers. Furthermore, unlike Britain and Ireland, France Galop does not employ an official medical adviser, preferring to provide a list of authorised doctors. That said, this is a new policy area for everyone; France Galop is generally a first mover when it comes to policy initiatives so it can’t be long before a collaboration with the AEDG emerges.

This article has focussed on what we know about trainers’ mental health and ways to help them deal with the impact. What it does not address is the strategic question, how could the sport, the trainer’s business model and – as importantly – trainers’ professional development be structured differently to minimise the risks to trainers’ mental health and therefore reduce the need for intervention when things fall apart?

Looking after our jockeys - Q&A with Denis Egan

Author - Dr. Paull Khan

In this issue, we conclude our series of Question and Answer sessions with the chairs of the various committees that operate in the EMHF region.

Following our features on the Pattern and doping control, we turn our attention to the well-being of our human athletes, the jockeys.

Denis Egan, who until recently was CEO of the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board, has also been the driving force within the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) when it comes to the welfare of riders. Not only does he chair the European Racing Medical Officers Group, but he has also been at the helm of the global International Conference for the Health, Safety and Welfare of Jockeys (ICHSWJ) since its inception some 15 years ago.

This time, our questions have been posed by various jockeys’ associations.

Q: What is the ICHSWJ?

DE: The ICHSWJ is a biennial conference for racing administrators, racecourse doctors, researchers and jockeys’ associations. The first conference was held in Tokyo (Japan) in 2006, and the ICHSWJ was officially recognised as one of the sub-committees of the IFHA in 2009. There have been eight conferences to date, which were held in Tokyo, Japan (2006), Antalya, Turkey (2008), Monmouth Park, USA (2012 & 2013), Hong Kong (2015) and Dubai, UAE (2010, 2017 and 2019).

The conference features presentations from the world’s leading racing administrators, racecourse doctors and researchers who work closely with jockeys both on the racecourse and through research studies. We are hoping to hold the next conference in Dubai in 2022, subject to COVID-19 restrictions being lifted.

Q: What is the charter of the ICHSWJ?

DE: The mission of the ICHSWJ is to provide a forum to discuss and implement strategies to raise the standards of safety and the standards of care provided to jockeys and to create a safer and healthier everyday life for jockeys when they participate in the sport.

The ICHSWJ has seven strategic objectives, namely to:

• RAISE awareness of jockeys’ health, safety and welfare issues

• HARMONISE standards and procedures throughout the world

• HARMONISE the collection of injury data

• PROVIDE a forum for the sharing of information

• SHARE research findings and foster collaboration

• PROPOSE strategies to deal with issues on a global basis

• SET UP a more effective communication mechanism between countries

Q: What do you see as the main focus by the attendees and presenters re jockeys’ health, safety and welfare?Is it bone health, making weight in a healthy manner (e.g., saunas, nutrition and fluid intake), concussion, injuries and falls, psychological/mental health issues, PPE (e.g., helmets and vests), or all of the above?

DE: It is all of the above with an increasing focus on mental health, concussion and making weight safely.If you look back at the agendas for the eight conferences that have taken place, the focus of the initial conferences was on what could be described as ‘traditional’ jockey issues such as weights, injuries and safety equipment, with little or no research having been carried out in any of the areas. Now everything has changed, and the focus is on the increasing amount of research that has been carried out in jockey health and safety-related issues. In Ireland we have been funding research since 2003, and many other countries have now developed their own research programmes. There is now much greater research collaboration between countries than there would have been in the past, and this has contributed to better results.

The one thing that has surprised me most is the huge focus that is now on mental health. The first time it appeared on a conference agenda was in 2017, and it has now become such a major issue everywhere. There have been numerous studies carried out that have found there are significant levels of depression amongst jockeys; and the industry is now addressing this with most countries putting better support in place for jockeys.

Studies have found that the life of a jockey has major highs and lows, and while success is a high, there are far more lows such as wasting, injuries, failing, travelling and social media abuse, which can be very hard to take. Studies have also found that there is a complex interplay between physical and psychological challenges: weight, dehydration, making weight and mood.

Q: What do you think is the number one issue facing jockeys at the moment?