Assessment of historical worldwide fracture and fatality rates and their implications for Thoroughbred racing

Article by Ian Wright

Racing’s social license is a major source of debate and is under increasing threat. The principal public concern is that racing exposes horses to significant risk of injury including catastrophic (life-ending) injuries of which fractures are the commonest cause. The most recent studies conducted in the UK indicate that fractures account for approximately 75% of racetrack fatalities. Recent events highlight the need for urgent stakeholder discussion, which necessarily will be uncomfortable, in order to create cogent justification for the sport and reliant breeding industry.

A necessary prelude to discussion and debate is an objective assessment of risk. All and any steps to reduce risks and mitigate their impact are important and must be embraced for horse racing (and quite possibly all other horse sports) to survive. To begin this, a here and now assessment is important: put simply, does the price paid (risk) justify the benefit (human pleasure, culture, financial gain, employment, tax revenue, etc.)? Objective data provides perspective for all parties, including the voting public who, via their elected representatives, ultimately provide social license with other welfare issues, both human and animal, on which society must pass judgement.

The data in Tables 1 to 12 report a country by country survey of fracture and fatality rates reported in scientific journals and documented as injuries/fatalities per starters. It may be argued that little of the data is contemporary; the studies range from the years 1980 to 2013. However, the tabulated data provided below is the most up to date that can be sourced from independently published, scrutinized scientific papers with clear—albeit sometimes differing—metric definitions and assessable risk rates.

In assimilating and understanding the information, and in order to make comparisons, some important explanatory points are important. The first, and probably the most important, is identification of the metric. Although at first glance, descriptor differences may appear nuanced—what is being recorded massively influences the data. These include fatality, catastrophic injury, fracture, orthopedic injury, catastrophic distal limb fracture, fatal musculoskeletal injury, serious musculoskeletal injury, and catastrophic fracture.

The influence of the metric in Japanese racing represents the most extreme example of this: “fracture” in the reporting papers included everything from major injuries to fragments (chips) identified after racing in fetlocks and knees, i.e., injuries from which recovery to racing soundness is now an expectation. At the opposite pole, studies in other countries document “catastrophic,” i.e., life-ending fractures which have a substantially lower incidence. The spectrum of metric definitions will all produce different injury numbers and must be taken into account when analyzing and using the data.

Studies also differ in the methods of data collection that will skew numbers in an undetermined manner. Some record only information available at the racetrack, others by identifying horses that fail to race again within varying time periods, and horses requiring hospitalization following racing, etc. The diagnostic criteria for inclusion of horses also vary between reports: some document officially reported incidents only, some are based only on clinical observations of racetrack veterinarians, while others require radiographic corroboration of injuries.

The majority of fractures that occur in flat racing, and between obstacles in jump racing, are the result of stress or fatigue failure of bone. They are not associated with traumatic events, occur during high speed exercise, are site specific and have repeatable configurations. In large part, these result from horses’ unique athleticism: in the domesticated species, the Thoroughbred racehorse represents the pinnacle of flight-based evolution. Fractures that result from falls in jump racing are monotonic, unpredictable and single-event injuries in which large forces are applied to bone(s) in an abnormal direction. This categorization is complicated slightly as fatigue failure at one site, which may be bone or supportive soft tissue, and can result in abnormal loads and therefore monotonic fracture at another.

The increased fracture rate in jump racing is explained in part by the cumulative risk of stress/fatigue and monotonic fractures. However, it is complicated by euthanasia of horses with injuries that in animals with greater post injury, commercial value and/or breeding potential might be treated. Catastrophic injuries and fatality rates in NH flat races (designed for young jump racing bred horses to gain experience before racing over obstacles; colloquially termed bumper races) are most logically explained by a combination of the economic skew seen in jump racing and compromise of musculoskeletal adaptation.

Much has been done to reduce recognizable risk factors particularly in jump racing, but in the UK, it is likely—for obvious data-supported reasons—that it will come under the greatest scrutiny. It might be argued that, outside of Europe, information on jump racing is interesting but of minimal impact to social license elsewhere. However, in the author’s opinion, a holistic perspective is important: loss of one sector or geographic location creates the potential for a momentum-gathering domino effect.

The incidence of fractures and fatalities in flat racing is low, and the number of currently identified risk factors is high. Over 300 potential influences have been investigated and over 50 individual factors demonstrated statistically to be associated with increased risk of catastrophic injury.

Racing surface influences both injury frequency and type. Studies in the UK have consistently documented an increased fatality rate and incidence of lower limb injury on synthetic surfaces compared to turf. Although risk differences are clear, confounding issues such as horse quality and trainer demographic mean that the surface per se may not be the explanation. In the United States, studies reporting data from the same geographic location have produced mixed results.

In New York these documented greater risks on dirt than turf surfaces while a California study found no difference and a study in Florida found a higher risk on turf. A more recent study gathering data from the whole of the US reported an increased risk on dirt surfaces. Variations in injury nature between surfaces, for example the increased incidence of sesamoid fractures (breakdown injuries) on dirt versus synthetic and turf surfaces, may go some way toward explaining fatality differences.

The majority of fractures occurring in flat racing (and non-fall related fractures in jump racing) are now also treatable, enabling horses to return to racing and/or to have other comfortable post-racing lives. The common public presumption that fractures in horses are inevitably life-ending injuries is a misconception that could readily be remedied. An undetermined number of horses are euthanized on the basis of economic viability and/or ability to care for horses retired from racing. On this point, persistence with a paternalistic approach is a dangerous tactic in an educated society.

Statements that euthanasia is “the kindest” or “best” thing to do, that it is an “unavoidable” consequence of fracture or that only “horsemen understand or know what is best” can be seen as patronizing and will not stand public scrutiny. At some point, data to distinguish between horses euthanized as a result of genuinely irreparable injuries and those with fractures amenable to repair will become available. Before this point is reached, the consequences require discussion and debate within the racing industry.

Decisions on acceptable policies will have to be made and responsibility taken. In its simplest form, this is a binary decision. Either economic euthanasia of horses, as with agricultural animals, is considered and justified as an acceptable principle by the industry; or a mechanism for financing treatment and lifetime care of injured horses who are unlikely to return to economic productivity will have to be identified. The general public understands career-ending injuries in human athletes. These appear, albeit with ongoing development of sophisticated treatments at reducing frequency, in mainstream news. Death as a direct result of any sporting activity is a difficult concept in any situation and draws headlines.

Removal of the treatable but economically non-viable group of injuries from data sets would reduce, albeit by a currently undetermined number, the frequency of race track fatalities. However, saving horses' lives whenever possible will not solve the problem; it will simply open an ethical debate viz is it acceptable to save horses that will be lame.

In order to preserve life, permanent lameness is considered acceptable in people and is not generally considered inhumane in pets. Two questions arise immediately (i) how lame can a horse be in retirement for this to be considered humane? (ii) who decides? There is unquestionably a spectrum of opinion, all of which is subjective and most of it personal. It will not be an easy debate and is likely to be complicated further by consideration of sentience, which now is enshrined in UK law (Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022); but it requires honest ownership of principles and an agreed policy.

For the avoidance of doubt, while the focus of this article and welfare groups’ concerns are on racetrack injuries, those sustained in training follow a parallel pathway. These currently escape attention simply by being, for the most part, out of sight and/or publicity seeking glare.

Within racing, there is unquestionably a collective desire to minimize injury rates. Progress has been made predominantly by identification of extrinsic (i.e., not related to the individual horse) risk factors followed by logical amendments. In jump racing (monotonic fractures), obstacle modification, re-siting and changing ground topography are obvious examples of risk-reducing measures that have been employed.

In flat racing, progress, has involved identification risk factors such as race type and scheduling, surface, numbers of runners, track conditions, etc., which have guided changes. However, despite substantial research and investment, progress in identification of intrinsic (i.e., relating to the individual horse) risk factors is slow. While scientifically frustrating, a major reason for this is the low incidence of severe fractures; this dictates that the number of horses (race starters) that need to be studied in order to assess the impact of any intervention is (possibly impractically) high. Nonetheless, scientific justification is necessary to exclude a horse from racing and to withstand subsequent scrutiny.

Review of potential screening techniques to identify horses at increased risk of sustaining a fracture while racing is not within the scope of this article but to date, none are yet able, either individually or in combination, to provide a practical solution and/or sufficiently reliable information to make a short-term impact. It is also important to accept that the risk of horses sustaining fractures in racing can never be eliminated. Mitigation of impact is therefore critical. When fractures occur, it is imperative that horses are seen to be given the best possible on-course care. This may, albeit uncommonly be euthanasia. Much more common, horses can be triaged on the course and appropriate support applied before they are moved to the racetrack clinical facility for considered evaluation and discussion. The provision of fracture support equipment to all British racecourses in 2022 marked a substantial step forward in optimizing injured horse care.

The distress/anxiety that accompanies an acute unstable racetrack fracture is considered predominantly to result from loss of limb control (horses are flight-based herd animals). Pain is both suppressed and delayed by catecholamines, e.g., adrenaline (the latent pain syndrome). As a result, relief of distress and anxiety from appropriate limb support always exceeds chemical analgesia. The immobilization principles behind the fracture support equipment are that fatigue/stress fractures have predictable courses; the distracting forces can therefore be predicted and logically counteracted. This is real progress: adoption of the principles and employment of the equipment in other countries would send out a strong positive welfare message.

Neither racing enthusiasts or fervent objectors are likely to change their opinions. The preservation of social license will be determined by the open-minded majority who lie between. It is the man on the street who must be convinced; most have no concept of the frequency of injury, care available or outcome potentials.

The task of all who appreciate horse racing's contributions to society and wish to see it continue is to remain focused on horse welfare, if necessary, to adjust historical dogmas, absorb necessary costs and to encourage open, considered, honest (factually correct) risks versus benefits discussion.

Country by country survey of fracture and fatality rates as reported in scientific journals and documented as injuries/fatalities per starters from 1980 to 2013.

Golden anniversaries - The New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Corporation and the Jockey Club of Canada

Article by Bill Heller

The New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Corporation and the Jockey Club of Canada are celebrating their golden anniversaries in 2023, and both are as vibrant and vital as they have ever been.

Each organization benefited from strong leadership in its early days. Dr. Dominick DeLuke, an accomplished oral and maxillofacial surgeon in Schenectady, New York, became the first president of the New York Thoroughbred Breeders Inc. DeLuke was seldom in the spotlight while he did the grunt work of getting New York-breds more competitive.

E.P. Taylor, the co-founder of the Jockey Club of Canada, was a legendary figure in Thoroughbred racing who is most remembered for his immortal racehorse and sire Northern Dancer. Taylor was seldom out of the spotlight. Asked of E.P. Taylor’s impact, Jockey Club of Canada Chief Steward Glenn Sikura said, “How would I do that? I think the word that comes to mind is visionary. Would we have Woodbine racetrack without E.P. Taylor? Absolutely not.”

New York-breds – Get with the Program

How do you start improving a breeding program? You begin with incentives. Using a small percentage of handle on Thoroughbred racing in New York State and a small percentage of video lottery terminal revenue from Resorts World Casino NY at Aqueduct and at Finger Lakes, the New York State Thoroughbred Breeding and Development Fund Corporation rewards owners and breeders of registered New York-breds awards for finishing in the top four in a race and provides substantial purse money for races restricted to New York-breds. The Fund pays out $17 million annually in breeder, owner and stallion owners awards and in purse enrichment at New York’s tracks.

“If it wasn’t for the rewards program, I wouldn’t be in the business,” Dr. Jerry Bilinski of Waldorf Farm said. “The program is the best in the country in my view and it helps the vendors, feed stores and all that.”

Bilinski, the former chairman of the New York State Racing and Wagering Board, bred his first New York-bred mare, Sad Waltz, in 1974.

He acknowledges DeLuke’s vital contribution. “Dr. DeLuke was a forefather,” Bilinski said. “I had dinner with him a number of times. He was smart. He was a smart guy. He didn’t try to reinvent the wheel.”

Instead, DeLuke, a 1941 graduate of Vanderbilt University and the Columbia University School of Dental and Oral Surgery, began breeding horses before the New York-bred program even began. He humbly visited every Kentucky farm that would receive him and asked dozens of questions about everything from breeding practices to barn construction to fencing. He learned enough to own and breed several of the fledgling New York-bred stakes winners. Divine Royalty, Vandy Sue, Dedicated Rullah and Restrainor won four runnings of the New York Futurity for two-year-olds in six years from 1974 through 1979. Restrainor also was the winner of the inaugural Damon Runyon Stakes in 1979.

DeLuke purchased a 300-acre farm in the foothill of the Adirondacks and named it Assunta Louis for his parents. Two decades later, Chester and Mary Bromans, the dominant owners of current New York-breds, many of whom have won open stakes, purchased the farm in 1995 and renamed it Chestertown. They named one of their New York-bred yearlings Chestertown, and he sold for a record $2 million as a two-year-old.

Fio Rito winning the 1981 Whitney Handicap.

Long before that, the New York-bred program needed a spark, and a valiant six-year-old gelding named Fio Rito provided a huge one in 1981. Fio Rito was literally a gray giant, 17.1 hands and 1,300 pounds. Twenty-two years before Funny Cide won the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, Fio Rito, who was owned by Ray LeCesse, a bowling alley owner in Rochester, and trained by Mike Ferraro, who is still going strongly at the age of 83, Fio Rito put his love of Saratoga Race Course to the test in the Gr.1 Whitney Handicap. A legend at Finger Lakes, where he won 19 of 27 starts, he had posted four victories and a second in five prior Saratoga starts.

He almost didn’t make the Whitney. Two days before the race, Fio Rito, who had won his four prior starts, injured his left front foot. It wasn’t serious. But the competition was. Even though there had been three significant scratches—Temperence Hill, Glorious Song and Amber Pass—he was taking on Winter’s Tale, Noble Nashua and Ring of Light.

Fio Rito winning the 1981 Whitney Handicap.

Ridden by Finger Lakes superstar Les Hulet, Fio Rito broke through the starting gate before the start, usually a recipe for disaster. But assistant starter Jim Tsitsiragos, held on to Fio Rito’s reins and didn’t let Fio Rito get away.

Though pushed on the lead every step of the way, Fio Rito held off Winter’s Tale to win by a neck in 1:48, just one second off Tri Jet’s track record and the fourth fastest in the Whitney’s illustrious history.

“TV and the media made sort of a big deal for a horse to come from Finger Lakes and be a New York-bred too,” Ferraro said. “It was kind of exciting for us to even compete in that race.”

The following year, another New York-bred, Cupecoy’s Joy, won the Gr.1 Mother Goose Stakes.

Still, New York-breds had a long way to go to be really competitive against top open company.

In 1992, Saratoga Dew won the Gr.1 Beldame and became the first New York-bred to win an Eclipse Award as Three-Year-Old Filly Champion.

In 1992 Saratoga Dew became the first New York-bred horse to win an Eclipse Award.

Two years later, Fourstardave completed a feat which may never be approached let alone topped. He won a race at Saratoga for the eighth straight year. Think about that. It’s the safest record in all of sports. Three years earlier, Fourstardave’s full brother, Fourstars Allstar, won the Irish Two Thousand Guineas.

And then came Funny Cide with Jack Knowlton and Sackatoga Stable, trainer Barclay Tagg, Hall of Fame jockey Jose Santos and a yellow school bus. Funny Cide was born at Joe and Anne McMahon’s farm, McMahon of Saratoga Thoroughbreds.

The McMahons, 76-year-old Joe and 73-year-old Anne, have been breeding, raising and racing horses before the New York-bred program started. They now boast a 400-acre farm with some 300 horses including 70 of their mares, 70 other mares, stallions including their star Central Banker, yearlings and foals.

“We’re very proud of what we accomplished,” Joe McMahon said. “It feels very good. It’s something we focused on for 50 years. With all the farms that have come and gone, it’s amazing that we’re still here.”

Now they have their three children helping run the business. They had nobody when they started.

A wedding present from Anne’s father allowed them to buy their farm in 1970. “It was hard,” McMahon said. “There wasn’t any interest.”

Slowly, the New York-bred program created interest. The McMahons did everything they could to help, successfully lobbying for changing the residency rules for mares in New York and beginning the New York-bred Preferred Sales. “I recruited the horses for the New York-bred sales,” McMahon said. “I’m very proud of that because that changed the whole business. It created a market. It was the early ‘90s. That was a real-game changer, and it is today.”

Central Banker with Corey Nakatani up win the 2014 Churchill Downs Stakes.

Today, the McMahons stand Central Banker, the leading stakes sire outside of Kentucky. “We went from breeding $1,000 stallions in New York to standing the best horse out of Kentucky,” McMahon said. “That’s a huge thing. He and Freud are the most successful stallions in New York.”

He continued, “We should be the poster child for the breeding program because we didn’t have anything starting out. Everything we got, we literally put back in the game. We continue to operate. I thought that was the purpose of the program: to maintain agricultural land that otherwise would have been developed commercially.”

Funny Cide was a turning point. “Funny Cide was a real game-changer for the whole industry,” McMahon said. “It was like an impossible dream come true. It was remarkable that a New York-bred won the Kentucky Derby.”

It was also remarkable what his jockey said after winning the race.

At the time of the 2003 Kentucky Derby, there had been a popular television commercial sponsored by the New York Thoroughbred Breeders, Inc., trumpeting the rich award program of New York State. After Funny Cide won the 2003 Kentucky Derby, commentator Donna Barton on horseback was the first person to interview Santos. She said, “You’re very happy about winning the Derby.” Jose replied with the catchline of the TV Commercial, “Get with the program, New York-breds.” Years later, Santos said, “I don’t even know how it came out of me. That surprised me when I heard it.”

Funny Cide added the 2003 Gr.1 Preakness Stakes and the 2004 Gr.1 Jockey Club Gold Cup.

Tiz the Law wins the 2020 Belmont Stakes.

A steady stream of accomplished New York-breds, including 2006 Gr.1 Beldame Stakes winner Fleet Indian and two-time Gr.1 Whitney winner Commentator (in 2005 and 2008) followed, before New York-breds provided more jolts. Mind Your Biscuits, the all-time leading New York-bred earner ($4,279,566), captured the 2018 Gr.1 Golden Shaheen in Dubai. That summer, Diversify added his name to the list of Whitney winners.

In 2019, Sackatoga Stable and Barclay Tagg’s Tiz the Law began his sensational two-year career by winning his debut at Saratoga. He added the Gr.1 Champagne, then dominated in both the 2020 Gr.1 Belmont Stakes—the first leg in the revised Triple Crown because of Covid—and the Gr.1 Travers Stakes. He was then a game second to Authentic in the Gr.1 Kentucky Derby.

“When people buy a New York-bred, they hope he can be the next Funny Cide or Tiz the Law,” Fund Executive Director Tracy Egan said. “I think it’s the best program in the country.”

That doesn’t mean it’s been a smooth journey. “It’s been a bumpy road,” former New York Racing Association CEO and long-time New York owner and breeder Barry Schwartz said. “There were so many changes. But I think today they’re on a very good path. I think the guy they have in there (New York Thoroughbred Breeders Inc. Executive Director Najja Thompson) is pretty good. Clearly, it’s the best breeding program in America.”

Thompson said, “The program rose from humble beginnings to today when we see New York-breds compete at the highest level.”

Certainly the New York Racing Association supports the New York-bred program. One Showcase Day of all New York-bred stakes races has grown into three annually. “NYRA has been a great partner in showcasing New York-breds,” Thompson said. “We make up 35 percent of all the races at NYRA.”

There’s a great indication of how New York-breds are perceived around the world. Both the third and fifth highest New York-bred earners, A Shin Forward ($3,416,216) and Moanin ($2,875,508) raced exclusively in Asia. A Shin Forward made 25 of 26 career starts in Japan—the other when he was fourth in a 2010 Gr.1 stakes in Hong Kong. Moanin made 23 of his 24 starts in Japan and one in Korea, a 2018 Gr.1 stakes.

Mind Control ridden by John Velazquez wins the 2018 Hopeful Stakes at Saratoga Race Course.

This year, new stallion Mind Control, who won more than $2.1 million, brought together three New York farms together: Rocknridge Stud, where Mind Control stands, Irish Hill and Dutchess Views Stallions. Mind Control’s strong stallion fee of $8,500 certainly reflects confidence in the New York-bred program.

“If you look at the quality of New York-bred horses, it just proves that it’s a success,” Bilinski said. “We’re never going to be Kentucky, but we’ll be the best we can in New York. It’s improved by leaps and bounds.”

Thompson concluded, “Anyone there at the start of the program would be proud of where we are now.”

The Jockey Club of Canada – Great Timing

Northern Dancer, Bill Hartack up, and E.P. Taylor after the 1964 Kentucky Derby win.

If timing is everything, then E.P. Taylor and his nine co-founders, knocked the formation of the Jockey Club of Canada out of the park. The Jockey Club came to life on Oct. 23, 1973, and its board of stewards were announced Oct. 27.

The very next day, the entire racing world was focused on Canada, specifically at Woodbine, where 1973 Triple Crown Champion Secretariat made the final start of his two-year career. Racing under Eddie Maple—a last-second replacement when jockey Ron Turcotte chose not to delay a suspension in New York, costing him the mount—Secretariat aired by 6 ½ lengths in the Canadian International as the 1-5 favorite.

At its initial meeting, Taylor was elected the Jockey Club’s Chairman of the Board and Chief Steward.

The other eight founders were Colonel, Charles “Bud” Baker, George Hendrie, Richard A.N. Bonnycastle, George Frostad, C.J. “Jack” Jackson and J.E. Frowde Seagram.

“These people were all very successful at what they did,” Jim Bannon, a Thoroughbred commentator who is in the Canadian Hall of Fame, said. “They were great business people who had a great sense of adventure and got in early when it was time for the Jockey Club. They were all gung-ho to be there. I think we got the best of the best right at the beginning. They were great enthusiasts, all of them. They saw E.P. Taylor’s success, and they were glad to join him.”

Edward Plunket Taylor was the first Canadian to be made a member of the United States Jockey Club in 1953 and also the first Canadian to be elected president of the Thoroughbred Racing Association in 1964. In 1973, he was named North America’s Man of the Year. He won Two Eclipse Championships as Outstanding Breeder in 1977 and 1983.

Northern Dancer with trainer Horatio Luro, Keeneland,1964.

Of course, by then, Northern Dancer’s brilliance on and off the track had been well documented. On the track, Northern Dancer won 14 of 18 starts, including the Gr.1 Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, with two seconds and a pair of thirds including his six-length defeat by Quadrangle in the 1964 Belmont Stakes. Northern Dancer more than atoned in his following start, winning the Queen’s Plate by 7 ¼ lengths as the 1-10 favorite. Taylor won the Queen’s Plate 11 times under his own name or Windfields Farm and bred 22 winners of Canada’s signature stakes. But Northern Dancer bowed a tendon shortly after winning the 1964 Queen’s Plate and was retired.

Initially, Northern Dancer’s stud fee at Windfields Farm in Maryland was $10,000. That changed quickly in 1967 when his first seven sales yearlings all won. Five of them won stakes. Northern Dancer’s stud fee was up to $100,000 in 1980 and climbed to $200,000 just two years later.

Northern Dancer sired 146 stakes winners, including several who went on to be great stallions themselves including Lyphard, Nijinsky II, Nureyev, Danzig, The Minstrel, Sadler’s Wells, Storm Bird, Vice Regent and Be My Guest. “Of all my father’s accomplishments in racing and breeding, I believe he was most proud of having established the Northern Dancer sire line,” Taylor’s son, Charles, said in the book Champions.

Taylor’s impact on Canadian racing can’t be overstated. He consolidated Canada’s seven tracks to three, improving Fort Erie and Old Woodbine/Greenwood and building a new Woodbine. “Without Mr. Taylor, Canadian racing would not be!” Hall of Fame trainer Frank Merrill said.

In 1973, Taylor resigned as the Chairman of the Ontario Jockey Club to head the Jockey Club of Canada. “We’ve never had a national Jockey Club before,” Taylor said at the time. “We felt it was important to Canadian racing to have this kind of organization, which could address important racing issues of the day.”

Fifty years later, the Jockey Club is still leading Canadian racing. Its current membership tops 100 with owners, breeders, trainers and key industry stakeholders.

Among its duties are conducting the annual Sovereign Awards; annually designating graded stakes; working to improve federal tax guidelines for owners and representing Canada at the annual International Federation of Horse Racing Authorities Conference.

“There are a lot of running parts,” trainer and Jockey Club member Kevin Attard said. “It kind of opens your eyes to a different part of racing from a trainer’s perspective. There’s a lot of things that go on a daily basis to have the product we have and put on the best show possible.”

Hall of Fame trainer Mark Casse, also a member of the Jockey Club, said, “It’s a great organization. It’s always trying to do what’s best for horse racing.”

That means continuing the battle for tax relief. “This is something that is extremely important to the Canadian horse owners and breeders,” Casse said. “It’s definitely the number-one priority.”

Sikura, who is also the owner of Hill ‘n’ Dale Farm Canada, said, “Fighting to get tax equity has been a battle for decades. We haven’t made major strides, but that won’t mean we stop trying. It doesn’t compare favorably to other businesses.’’

Asked about progress on that issue, he said, “We’re marginally better off.”

In general, Sikura said, “I think we have the same challenges most jurisdictions have. I’m cautiously optimistic. It’s always been an uphill battle, but horse racing people are a resilient group.”

Fred Hooper - The Extraordinary Life of a Thoroughbred Legend

This summer, author Bill Heller publishes his latest book, Fred Hooper, The Extraordinary Life of a Thoroughbred Legend. the rags-to-riches story of a true giant of the racing world.

Excerpts from the book are published below with the full book available to purchase exclusively via trainermagazine.com/hooper

Fred W. Hooper didn’t just survive 102 years—he lived them. Every single day until he died. As the keynote speaker at the 1981 Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame inductions in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., on August 6, he shared part of a poem that he said reflected his philosophy of life. He was 83 years old at the time.

“I want to be thoroughly used when I leave this earth,” he said. “The harder I work, the more I live. I rejoice in life. Life is no brief candle to me. It is sort of a splendid torch which I have hold of at the moment and want to make burn as bright as I can before passing it on to future generations.”

On the morning of his last day in 2000, he called his trainer, former NFL cornerback Bill Cesare, to check about a filly they were going to race two days later. Fred’s third wife, Wanda, who was married to him for 30 years, called Bill back the next morning to tell him the sad news that Fred had passed.

He left behind a legacy of success in so many different fields that it is hard to fathom one human being doing so much. He was:

An eighth-grade dropout who became a substitute teacher at his former grammar school, then, decades later, funded a school, Hooper Academy—still thriving 50 years later in Montgomery, Ala.

A teenage horse swapper, a daredevil at the George State Fair, a barber, a boxer, a potato farmer, a carpenter, a steel worker, a timber trader, a county commissioner, a stockyard builder and an extremely successful cattle breeder.

A construction worker who got his first job with no previous experience and, really, no knowledge of the business, who quickly opened his own company and built roads, bridges, dams, airports and buildings all over the southeast and courses at racetracks around the country.

A Thoroughbred owner who won the rescheduled 1945 Kentucky Derby with the first Thoroughbred yearling he bought, Hoop Jr., named for his son. Later, he fired and rehired trainers as frequently as his friend, George Steinbrenner, went through managers of the New York Yankees. Fred’s favorite horse, three-time champion filly Susan’s Girl, went through seven trainers in her illustrious career: Jimmy Picou, John Russell, Charley “Chuck” Parke, Hall of Famer Tommy “TJ” Kelly, J.L. Newman, Robert Smith and Ross Fenstermaker. “He’d fire me, hire somebody else, then hire me back,” Ross said in 2020. Ross also trained Fred’s $3.4 million-earner, Champion Precisionist, for the bulk of his career.

A Thoroughbred innovator and pioneer—the first owner to successfully ship his horses cross-country on airplanes to contest stakes races, designing the stalls and manufacturing the adjustable ramp to load them on and off; the first to bring three jockeys from Panama to ride in the United States and all three became Hall of Famers: Braulio Baeza, Jorge Velasquez and Laffit Pincay Jr., who collectively won more than 20,000 races, and one of the first to buy horses in South America to race and breed in the U.S. Fred also weighed his horses regularly to monitor their health.

A Thoroughbred breeder of 115 stakes winners, literally creating his own pedigrees with his home-breds.

A Thoroughbred gambler whose speedy Olympia won a legendary match race with a Quarter Horse, earning the $50,000 winner-take-all pot and more than $90,000 he booked in side bets. Olympia was Fred’s first airplane shipper in 1949, returned to finish sixth as the favorite in the Kentucky Derby, then became an incredibly impactful sire.

A Thoroughbred industry leader who formed the national Thoroughbred Owners’ and Breeders Association and the Florida Thoroughbred Owners’ and Breeders’ Association, serving as president in both organizations.

Along the way, he and his horses received seven Eclipse Awards, Thoroughbred racing’s highest honor.

In a beautiful Blood-Horse story after Fred passed, trainer John Russell, also a fine writer, said, “No one ever loved racing more than Mr. Hooper, and certainly no one loved his horses more than this man.”

Fred showed his love every time he drove his Cadillac around his farm’s pastures to distribute carrots to his horses. He’d hide the carrots behind his back, and each horse had to nuzzle him to get the treat.

Fred was the patriarch of a large loving family, all of whom called him Big Daddy. To this day, everybody in Thoroughbred racing still calls him Mr. Hooper—a measure of the immense respect he still generates. “He’s just one of those iconic names in our sport,” Hall of Fame jockey Mike Smith said. “When you got an opportunity to ride for a man like Mr. Hooper, you knew you had made it. You knew he was such a giant in the sport.”

How did one of 13 children born on a farm in Cleveland, Ga., accomplish all that? “One of his favorite lines was `Look ahead. Never look back,’” Wanda said. “He always looked forward.”

Sometimes he had no other choice. That made his journey even more remarkable.

“He was a very positive man,” his daughter, Betty Hooper Green, said. “He always said, `Look to the future. Don’t think about mistakes you made in the past. Look to the future and make things better.’”

Hall of Fame jockey Pat Day remembers being at trainer Bill Cesare’s barn the day after Fred’s two-year-old filly won a race at Arlington Park: “We were at the barn, and somebody came by and wanted to buy the filly. He said, `No, I want to keep her. I’m going to watch her babies run.’”

Pat said, “I was flabbergasted. He was maybe 92 or 93. Here’s a two-year-old filly who’s going to race as a three-year-old, then maybe as a four-year-old. Then she’s going to be bred and have a baby, who wouldn’t race for at least another two years. We’re talking six or seven years. I looked at him. He was such an optimist.”

Maybe it was because of his work ethic—one likely instilled by his father, struggling to keep food on the table for their ever-growing family. Regardless, Fred earned his success. Nothing was ever handed to him, so he relied on himself to pave his way through his long life. “The harder I work, the luckier I get,” Fred told Wanda.

He worked alone. He almost always owned his horses by himself, rarely in a partnership. In Jim Bolus’ book Remembering the Derby, Fred said, “I just feel that what I have I want to own myself. I just have always felt like that whatever I do; if it’s wrong, why then I’ll be to blame. I was in heavy construction, building roads and airports and dams over six of the southeastern states for 36 years, and I just didn’t want a partner, that’s all.”

His way with horses was to keep his barns meticulous. He paid attention to all the details, no matter how small. In a December 1, 1997 Sports Illustrated article celebrating Fred’s recent 100th birthday, Frank Lidz wrote of Fred and Wanda’s 912-acre spread in Ocala: “Throughout the estate, from breeding sheds to training gallops, all is immaculately groomed. Flowers abound. Grass is clipped. Stables are clean and freshly painted, masonry pointed and trim, tack in order, hay baled, manure invisible.”

That required attention to detail. “They would put up posts in the ground to build a fence on his farm,” Fred’s grandson, Buddy Green, said. “He would push against the post in a pick-up truck to make sure it didn’t move. He was that type of man. I respect that. He wanted it done right.”

Fred always felt right when he was with horses, especially his own. “Horses were his children,” Buddy’s mother, Betty Green said. “He would stop on his way into town at the vegetable stand, and he’d pick up carrots and take them to his horses. They would break the car antenna. They loved it, and they all would come.”

Fred’s impact on horse racing still resonates long after he passed.

When American Pharoah ended a 37-year Triple Crown drought by sweeping the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes and the Belmont Stakes in 2015, he carried bloodlines featuring five of Fred’s horses, Zetta Jet, Tri Jet, Crozier, Olympia and Hoop Jr. Justify, the 2018 undefeated Triple Crown Champion, and Ghostzapper, a superstar on the track and off as a stallion, both trace back to Tri Jet.

When the coronavirus pandemic forced Churchill Downs to reschedule the 2020 Kentucky Derby from the first Saturday of May to the first Saturday of September, a story in the Montgomery Independent documented the first and only other time the Derby was postponed: in 1945 when Hoop Jr. won.

At Gulfstream Park on January 23, 2021, Phipps Stable and Claiborne Farm’s five-year-old horse Performer won the 35th running of the $125,000 Gr3 Fred W. Hooper Stakes at one-mile on turf. The race was formally named the Tropical Park Handicap.

Later in 2021, another senior class graduated from Hooper Academy.

Not bad for an eighth-grade dropout in rural Georgia. Not bad at all.

********************************

Many times, Fred would tell people his favorite horse was three-time Champion filly Susan’s Girl. And while Hoop Jr. and Precisionist also meant the world to him, Olympia may have been the most fascinating horse he ever owned.

A sub-headline on Anne Peters’ July 3rd, 2015, Blood-Horse pedigree analysis of Olympia quoted her story’s final sentence:

Without Olympia our world would be a much slower place

Yet for all the blazing speed he showed in races and passed on to his progeny, Olympia was also the sire of 1970 Steeplechase Champion Top Bid, who won the three-mile Temple Gwathmey Stakes by four lengths at Belmont Park during his champion season at the age of six.

Fred’s trainer Ivan Parke bred Olympia, a son of Heliopolis out of Miss Dolphin by Stimulus. Parke had trained Miss Dolphin, a stakes winner who set four track records after selling for just $700 as a yearling at Saratoga in 1936.

American Classic Pedigrees described Olympia as a “small, lengthy bay horse with a Roman nose. Olympia was a blocky, powerful sprinter type who ran to his looks.”

Fred didn’t want his trainer owning horses, so he purchased Olympia when he was one month old while keeping Parke as his trainer.

Olympia shined as a two-year-old immediately, winning his maiden debut at Keeneland April 16, 1948, by three lengths. He went on to win the Joliet Stakes at Washington Park by 3 ½ lengths, the Primer Stakes at Arlington Park by four lengths and the Breeders’ futurity at Keeneland by a neck. He finished second in the Bashford Manor at Churchill Downs, the Arlington Futurity, the George Woolf Memorial Stakes at Washington Park and in the Babylon Handicap and the Cowdin at Aqueduct. He finished his two-year-old season with four victories, six seconds and one third from 14 starts—almost all of them on the lead—earning $76,362.

As a three-year-old, he rocked the racing world.

Stella Moore, a Quarter Horse Champion owned by Quintas I. Roberts of Palatka, Fla., had beaten a speedy Thoroughbred named Fair Truckle in a California match race.

Roberts asked Fred if he’d like to have his Olympia take on Stella Moore in a match race. Fred had been the king of match races with Prince/Royal Prince and he agreed, suggesting they each put up $50,000 in a winner-take-all quarter-mile match race at Tropical Park Racetrack in Coral Gables, five miles north of Miami. Roberts countered with an offer of each owner betting $25,000, and Fred agreed. The match race would be held in between races at Tropical Park on January 5, 1949, matching freshly-turned three-year-old Thoroughbred colt Olympia against the now four-year-old Quarter Horse mare Stella More.

According to Jim Bolus in “Remembering the Derby,” Calumet Farm’s trainer Ben Jones told Ivan Parke that he was foolish to think Olympia could win. “One day, just two or three days before the match race was run, a groom from Calumet Farm’s barn came up there with $1,000 and said to Ivan Parke, 'We want to bet on the Quarter Horse,’” Fred told Bolus. “I said, ‘Ivan, let me have that money. That’s Ben Jones’ money.’ I told the groom, ‘Go back and tell Ben to send some more money up. I have some more left.’”

Almost all accounts of the match race put the figure Fred handled that fateful afternoon in side bets at $93,000.

In Frank Lidz’s 1997 story about Fred in Sports Illustrated, Fred said, “People thought I was crazy to let Olympia race a Quarter Horse at two furlongs. I knew I was crazy, all right, but Olympia was awfully fast, and I thought he could beat anybody.”

But showing great attention to detail, Fred measured the course. “The finish line was 73 feet short of a quarter-mile when the gate was put in the chute,” Fred told Ed Bowen in Legacies of the Turf, Volume 2. “I changed the finish and made them run the full quarter. I wasn’t going to take any of the worst of it.”

Pat Farrell, the Tropical Park Racing Secretary, was given the awesome responsibility of recording bets and making payoffs. “I never saw such action,” he told Chuck Tilley in his 1997 Florida Horse cover story on Fred.

Writing about Fred in his book Stories from Cot Campbell, Racing’s Most Interesting People, Cot Campbell said of Pat: “As he received money, he pushed it into the top right drawer of his desk and locked it. At post time, he then locked the door to the racing secretary’s office and rushed out to see the making of racing history.”

According to Fred, “Olympia and Stella Moore broke nearly even. At the eighth pole, Stella Moore was about two lengths in front, but when they got to the finish line, Olympia was there first.” Olympia had won by a head in :22 4/5.

“The finish was scary, but not nearly as scary as the settling of the bets,” Campbell continued in his book. “After pictures were taken and hands were shaken, a big crowd went back to Pat Farrell’s office for the settling-up ceremonies.

“With a big smile on his face, Pat withdrew his key from his pocket, held it up as a magician might have, and with a flourish inserted it into the lock on the drawer. He flung the drawer open for one and all to behold the absolute staggering cache of greenbacks, now belonging to Fred Hooper.

“The drawer was empty. Pat Farrell looked as if he would lose his lunch. His face was ashen, and he thrust his hand into the drawer as if he might be able to feel the money, even though he certainly could not see it! The atmosphere in the room was decidedly tense. Finally, Farrell jerked the drawer completely out of the desk. The bigger drawer beneath it was housing a truly splendid clump of greenbacks. There was the stash of cash. There was no back panel in the top drawer, so as Farrell hurriedly pushed the final batch of bills toward the back of the drawer, the dough had dropped out of sight into the bottom compartment.”

Fred collected, gave a $1,000 tip to Pat Farrell, and then, according to Lidz’s story in Sports Illustrated, came up with this classic: “I told Roberts that if he was game, I’d fetch another Thoroughbred from my stable.’ He said, `No thanks; I’ve got just enough money to get back home.’”

Hall of Fame trainer John Nerud, who would become close friends with Fred, shared this story with Chuck Tilley and Gene Plowden’s book This is Horse Racing: “After I looked at the match race, I went back to my barn and there was a fellow sitting on a bucket and crying; a big man he was, just sitting there crying. I went over and asked him what was the matter. He looked up at me and said, `I just lost an automobile agency today!’”

From then on, Olympia was the horse to beat in the Kentucky Derby. He wore the label of Derby favorite well, though the Daily Racing Form (then called the Morning Telegraph) didn’t include the match race in Olympia’s past performance lines, presumably because he had raced against a Quarter Horse.

Just two weeks after the match race, Olympia led most of the way before tiring to finish second by a half-length as the 2-5 favorite in the Hibiscus Stakes at Hialeah, January 19.

Fred then sent Olympia to California to continue his Derby preparation. In doing so, Fred pioneered what is commonplace today: flying Thoroughbreds cross-country to contest major stakes races around the country.

“Horses weren’t being flown around those days,” Fred told Ed Bowen in 1973. “Eastern Airlines leased me a DC-4, which was a nice plane, but I had fixed my own crates and everything and put the horse and the lead pony in. I fixed some canvas muzzles that had a screw in the bottom of them, so I could put two oxygen tanks in the plane, with about 30 feet of hose on each. The plane was not pressurized. Also, I fixed straps to go over their shoulders.

“I told Eastern that since I had to do everything to get the horses ready to fly, I should pick out my own pilot; so they said I could pick any pilot I wanted. I chose Dick Merrill, who was one of the greatest (and an ace pilot during World War II). We flew two horses out there, left them for 30 days for the races, then flew them back.”

There was a great picture accompanying Ed Bowen’s 1973 story in the Blood-Horse showing the interior of the plane with Fred standing next to Olympia while Dick Merrill was petting Olympia’s face and Ivan Parke looked on.

Soon Olympia and Colosal became frequent fliers. Eventually, other owners and trainers would catch up to the kid from Georgia who pioneered shipping horses by air, long before Hall of Fame trainer D. Wayne Lukas was celebrated for flying horses coast-to-coast for stakes races. Joe Drape wrote in a January 6, 2013, story in the New York Times: “Back in the 1980s, when his stable was 250 strong and he flew horses all over to win the nation’s biggest races, Lukas earned the nickname `D. Wayne off the plane.’”

Fred did that three decades earlier.

But in 1949, not everyone thought flying horses on planes was a good idea. “He was one of the first ones to fly horses,” Fred’s nephew, Harold Campbell said. “He built an adjustable ramp for horses to use to walk into an airplane. When he first used it, it was one of the biggest things that happened in Montgomery. It was unreal. There were TVs, newspapers. One thing I will never forget is that the article on the front page of the newspaper said:

“Fred W. Hooper – A man that has more dollars than cents, flying horses”

Fred’s reaction? “He didn’t take to that very well,” Harold said. “Damn right. He didn’t let them get away with it. He gave them hell. He did a lot of first-time things. He always ended coming out of it smelling like roses.”

Olympia did his part. Showing zero jet lag—actually airplane lag—Olympia made his first start at seven furlongs as Parke tried stretching out his speed. He captured the San Felipe Stakes by five lengths as the even-money favorite February 5.

Exactly two weeks later, Olympia stretched out to a mile-and-an-eighth in the Santa Anita Derby. Sent off the 3-5 favorite, Olympia led most of the way, tiring late to finish second by a length and a half to Old Rockport.

Remembering Sunday Silence -30 years since he first entered the breeding shed. We look at the lasting legacy he has left on the racing world.

By Nancy Sexton

For over a quarter of a century, there has been an air of inevitability within Japanese racing circles.

Sunday Silence dominated the sire standings in Japan for 13 straight years from 1995 to 2007—his last championship arriving five years after his death. He was a true game changer for the Japanese industry, not only as a brilliant source of elite talent but as a key to the development of Japan as a respected racing nation.

Any idea that his influence would abate in the years following his death was swiftly quashed by an array of successful sire sons and productive daughters. In his place, Deep Impact rose to become a titan of the domestic industry. Others such as Heart’s Cry, Stay Gold, Agnes Tachyon, Gold Allure and Daiwa Major also became significant sires in their own right. Added to that, Sunday Silence is also a multiple champion broodmare sire and credited as the damsire of 202 stakes winners and 17 champions.

Teruya Yoshida of Shadai Farm

“Thoroughbreds can be bought or sold,” says Teruya Yoshida of Shadai Farm, which bought Sunday Silence out of America in late 1990 and cultivated him into a global force. “As Nasrullah sired Bold Ruler, who changed the world’s breeding capital from Europe to the U.S., one stallion can change the world. Sunday Silence is exactly such a stallion for the Japanese Thoroughbred industry.”

Sunday Silence has been dead close to 20 years, yet the Japanese sires’ table remains an ode to his influence.

In 2020, Deep Impact landed his ninth straight sires’ championship with Heart’s Cry and Stay Gold’s son Orfevre in third and fourth. Seven of the top 12 finishers were sons or grandsons of Sunday Silence.

Another descendant, Deep Impact’s son Kizuna, was the nation’s leading second-crop sire. Deep Impact himself was the year’s top sire of two-year-olds.

Against that, it is estimated that up to approximately 70% of the Japanese broodmare population possess Sunday Silence in their background.

All the while, his influence remains on an upswing worldwide, notably via the respect held for Deep Impact. A horse who ably built on the international momentum set by Sunday Silence, his own sire sons today range from the European Classic winners Study Of Man and Saxon Warrior—who are based in Britain and Ireland—to a deep domestic bench headed by the proven sires Kizuna, Mikki Isle and Real Impact.

In short, the Thoroughbred owes a lot to Sunday Silence.

Inauspicious beginnings

Roll back to 1988, however, and the mere idea of Sunday Silence as one of the great fathers of the breed would have been laughable.

For starters, he almost died twice before he had even entered training.

Queen Elizabeth II meets Halo.

The colt was bred by Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds Ltd in Kentucky with appealing credentials as a son of Halo, then in his early seasons at Arthur Hancock’s Stone Farm.

Halo had shifted to Kentucky in 1984 as a middle-aged stallion with a colourful existence already behind him.

By Hail To Reason and closely related to Northern Dancer, Halo had been trained by Mack Miller to win the 1974 Gr1 United Nations Handicap.

It was those bloodlines and latent talent that prompted film producer Irving Allen to offer owner Charles Englehard a bid of $600,000 for the horse midway through his career. Allen’s idea was to install Halo in England at his Derisley Wood Stud in Newmarket; and his bid was accepted only for it to be revealed that his new acquisition was a crib-biter. As such, the deal fell through, and Halo was returned to training, with that Gr1 triumph as due reward.

Would Halo have thrived in England? It’s an interesting question. As it was, he retired to E. P. Taylor Windfields Farm in Maryland, threw champion Glorious Song in his first crop, Kentucky Derby winner Sunny’s Halo in his third and Devil’s Bag—a brilliant two-year-old of 1983—in his fourth.

Devil’s Bag’s exploits were instrumental in Halo ending the year as North America’s champion sire, and within months, the stallion was ensconced at Stone Farm, having been sold in a deal that reportedly valued the 15-year-old at $36 million. Chief among the new ownership was Texas oilman Tom Tatham of Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds.

In 1985, Tatham sent the hard-knocking Wishing Well, a Gr2-winning daughter of Understanding, to the stallion. The result was a near black colt born at Stone Farm on March 26, 1986.

It is part of racing’s folklore how Sunday Silence failed to capture the imagination as a young horse—something that is today vividly recalled by Hancock.

Staci & Arthur Hancock with Sunday Silence.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents or sign up below to read this article in full

ISSUE 59 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 59 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Remembering Hollywood Park - Edward “Kip” Hannan and the Hollywood Park archive

By Ed Golden

In an age of “Races Without Faces,” Edward Kip Hannan is a renaissance man.

Kip Hannan outside of UCLA’s Royce Hall

Not to be confused with an anarchist bent on destroying history’s truths, Hannan is an archivist, with an ethos dedicated to preserving timeless treasures and ensconcing them in pantheons for future generations.

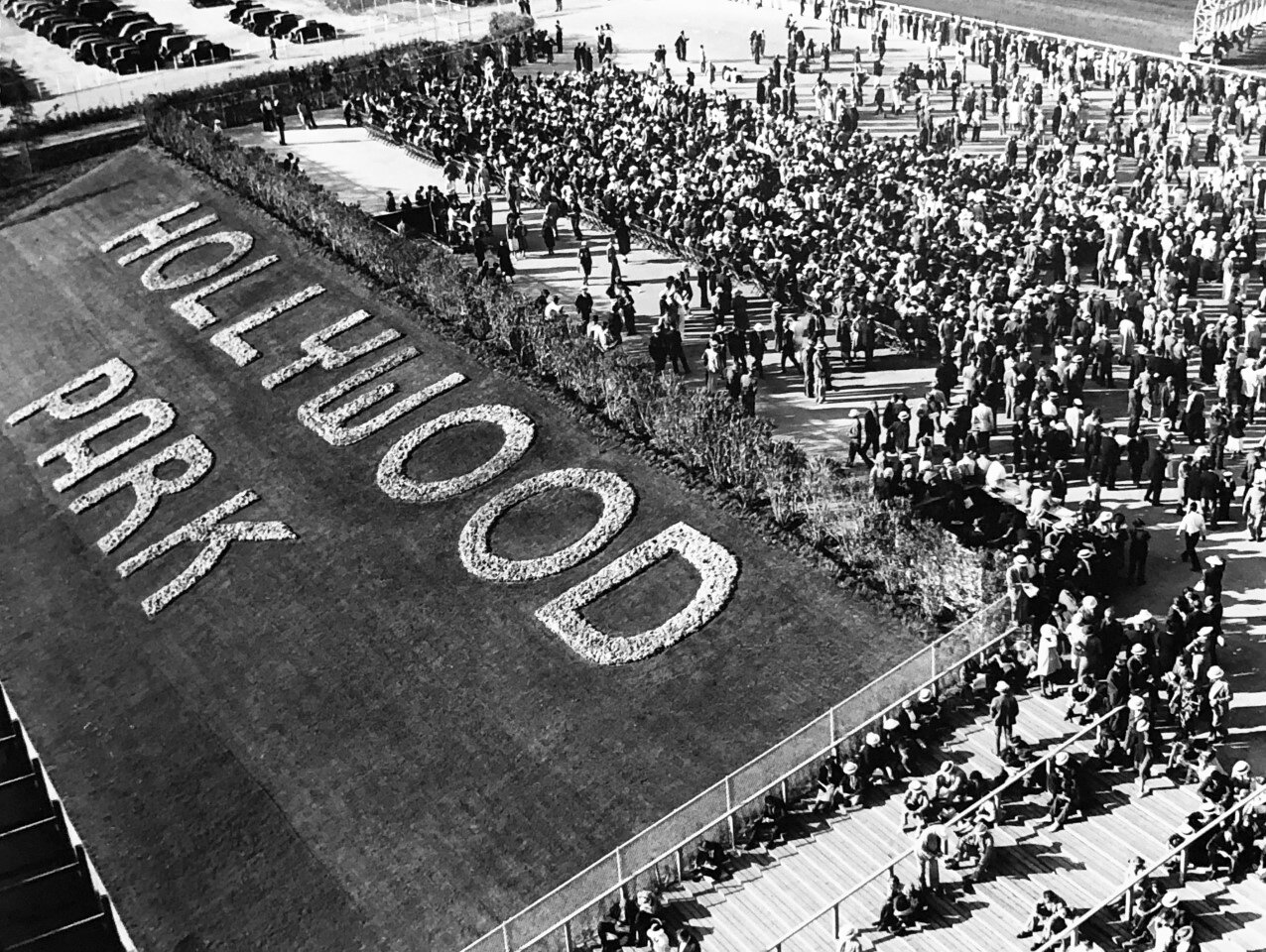

With the artistic and obdurate passion of a Michelangelo, when Hollywood Park closed forever on Dec. 22, 2013, like a man possessed with an oblation, Hannan knew there was “gold in them thar hills” and dug in like he was assaulting the Sistine Chapel.

Far from a fool and capitalizing on today’s applied sciences, Hannan has successfully transitioned through more than four decades, surviving—yea, overcoming—a concern once epitomized by Albert Einstein who said: “I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world will have a generation of idiots.”

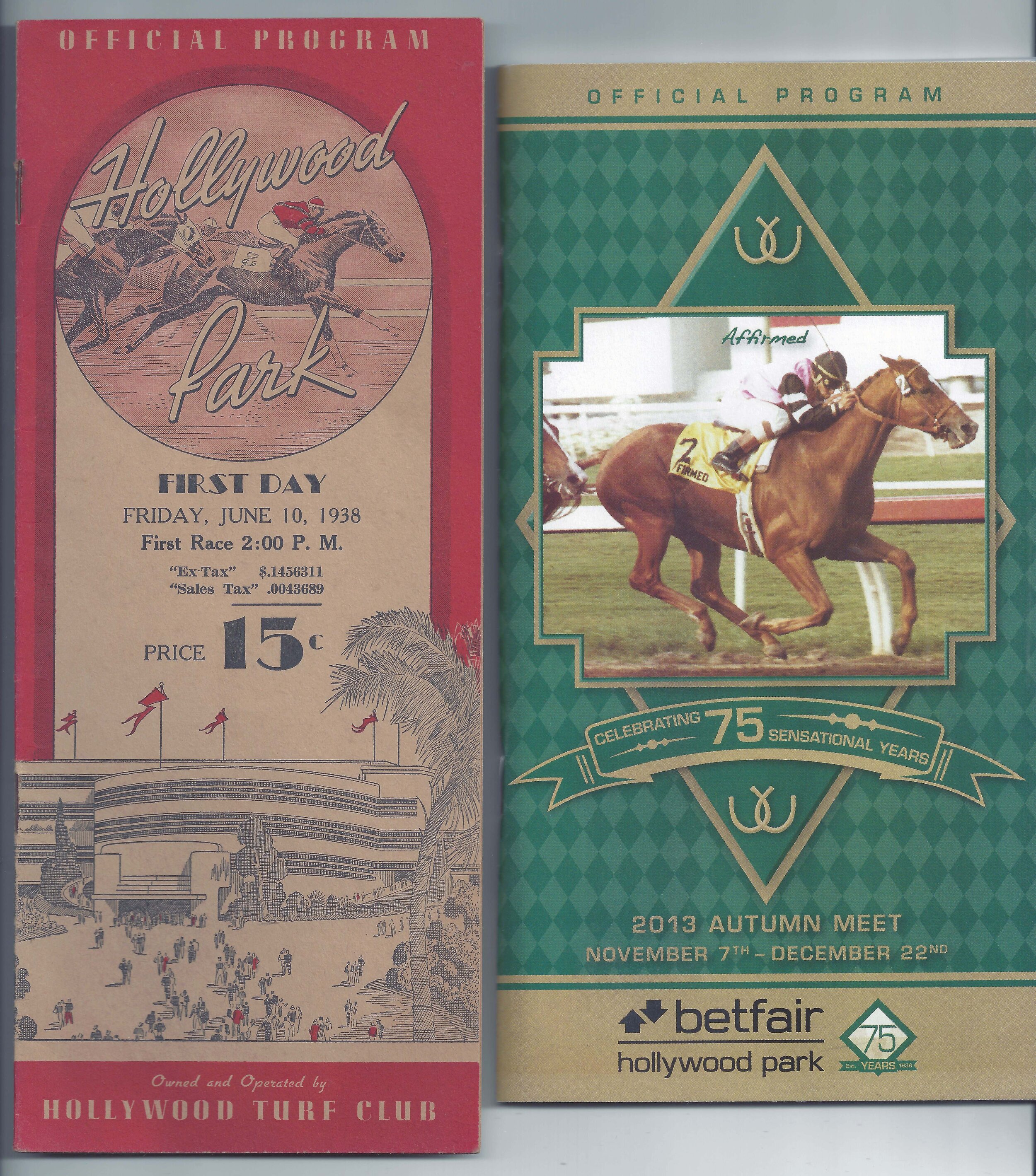

Hannan made it his mission to rescue archives from the Inglewood, Calif. track that opened 75 years earlier on June 10, 1938. The Hollywood Turf Club was formed under the chairmanship of Jack L. Warner of the Warner Brothers film corporation.

Hollywood Park Opening Day and Closing Day programs.

Among the 600 original shareholders were many stars, directors and producers of yesteryear from movieland’s mainstream, including Al Jolson, Raoul Walsh, Joan Blondell, Ronald Colman, Walt Disney, Bing Crosby, Sam Goldwyn, Darryl Zanuck, George Jessel, Ralph Bellamy, Hal Wallis, Wallace Beery, Irene Dunne and Mervyn LeRoy.

They pale, however, compared to the equine stalwarts that raced at Hollywood Park, which include 22 that were Horse of the Year: Seabiscuit (1938), Challedon (1940), Busher (1945), Citation (1951), Swaps (1956), Round Table (1957), Fort Marcy (1970), Ack Ack (1971), Seattle Slew (1977), Affirmed (1979), Spectacular Bid (1980), John Henry (1981 and 1984), Ferdinand (1987), Sunday Silence (1989), Criminal Type (1990), A.P. Indy (1992), Cigar (1995), Skip Away (1998), Tiznow (2000), Point Given (2001), Ghostzapper (2004) and Zenyatta (2010).

Hannan obviously had his hands full, but thrust ahead undeterred as he soldiered on to digitize Hollywood Park’s entire film/video history of nearly 4,000 stakes races for eventual public access.

It seemed a mission mandated by a higher power.

Hannan, who turns 57 on Jan. 29, was born in Phoenix, Ariz., where his mother and father had come from Brooklyn. Moving to California when he was just two, they lived on the Arcadia/Monrovia border within a couple miles of storied Santa Anita, and left in 1972 for nearby Temple City where Kip has lived ever since.

In 1979, at the tender age of 15, he began working as a marketing aide at Santa Anita under the aegis of worldly racing guru Alan Balch and his fastidious publicity sidekick, Jane Goldstein.

Hollywood Park, 1939.

He was the last employee at Hollywood Park in order to organize archives for digitization and eventual transfer to the UCLA Library, where he began working in late 2014 as videographer and editor. He is still employed there, maintaining the integrity of Hollywood Park film, video, photo and book archives.

Hannan sums up his career in one word: “Fascinating.”

“I had already started collecting music at age 11, in 1975,” Hannan said, “and probably because of this, I associate many life events with the music of the time. I’m sure many people can relate.

“It was at Santa Anita where and when I first met Lou Villasenor, who was already working there and would go on to become a staple of its TV broadcast team—a job he held for nearly 35 years before his death in 2018.

“Lou became one of my best friends and eventually was the one who brought me to Hollywood Park where I was hired to work in its television department in 1986.”

As marketing aides, their tasks were menial and labor intensive, such as removing duplicates from mailing lists, organizing contest entry cards filled out by fans, and other simple office-related duties. After a few years, Hannan was promoted to supervisor.

At Santa Anita in 1982, Hannan met another new hire who became an instant best friend: Kurt Hoover, current TVG anchor whose relaxed and ingratiating on-camera presence is the stuff of network standards. He also is a devoted and skilled handicapper and a successful horse owner.

“We hit it off immediately,” Hannan says.

A couple years later, Hannan left Santa Anita briefly to study television production at Pasadena City College, while also finding time to work at Moby Disc Records in town.

Burt Bacharach and wife Angie Dickinson admire their race horse Apex II in his Hollywood Park stall, 1969.

“I had always been a movie buff, with the original 1933 ‘King Kong’ my inspiration, along with ‘One Million Years B.C., and not just because of Fay Wray and Raquel Welch—although I had crushes on both. It was the dinosaurs and the stop-motion filmmaking and special effects.

“I wanted to get into film somehow but couldn’t afford USC, so the gateway was video/television production, first in high school and then at Pasadena City College.

“It was around this time, summer of 1985, that Santa Anita contacted me out of the blue,” he said. “Knowing I had radio operation training in college, they told me of a radio station in the planning stages that would be an on-site source for racing fans and handicappers broadcasting information throughout the day.

“Nearly doubling my hourly wage from the record store, I jumped at the chance. It was designed and organized by the same company that created the low-power AM radio station that can be picked up near the LAX Airport for flight information; and soon, KWIN Radio AM was created.

“I was the operator/engineer with countless marketing people and handicappers available for on-air hosts and guests. It was at this time I met Mike Willman, the ‘roving reporter’ and program manager of sorts, who gathered interviews on his cassette recorder for us to air.

“On April 23, 1986, Villasenor took me to Hollywood Park where he was program director and graphics operator in its TV department.

“I was fortunate to be there and was in the right place at the right time. They were short of cameramen that day, and word came from Hollywood Park President Marje Everett that many of her personal friends would be attending, including popular celebrities of music, film, television and politics.

“The TV department was to capture ‘Opening Day Greetings’ from them on their arrival. The TV director asked if I could handle the professional portable camera, portable tape deck and tripod. I said yes, gathered up everything, and headed to the Gold Cup Room, avoiding crowded elevators with all that gear.

“It was then I realized my career was moving up, for at that moment, not three steps behind me on the escalator were Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Jackson. As we continued to climb, all I could think of was getting to a phone to tell my folks how my first day went, before it had even started!

Michael Jackson and Elizabeth Taylor, 1986.

“There is one particular snapshot taken in the Gold Cup Room that I cherish. I’m not in the photo but was about six feet ahead of them, walking with my gear like I was on top of the world at age 22.

“I did get Michael Jackson’s autograph later, as miraculously he only had one bodyguard with him that day. At the time, there was not a bigger pop music star on the planet, and it was surreal to see him right before me.

“Even though they both declined to appear on camera for a greeting, it was Elizabeth Taylor who got to me. As I set up my camera gear not 25 feet from where she was sitting (and momentarily alone), she glanced up from the table and looked directly at me with this big smile.

“I literally melted! As I continued to fumble getting the camera onto the tripod, I kept thinking, ‘Dear God, those eyes!’ and I was ready to sign on for husband number seven, as suddenly it had all made sense to me. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

ISSUE 58 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 58 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Remembering - Seattle Slew - 1977 Triple Crown winner

By Ed Golden

All photographs published by kind permission of Hollywood Park archive

Bob Baffert was a young pup of 24, fresh out of college about to make a name for himself training Quarter horses at outposts in Arizona like Sonoita and Rillito when Seattle Slew became the first undefeated Triple Crown winner in 1977.

Forty-one years later, in 2018, Baffert followed suit, deftly leading Justify successfully down racing’s Yellow Brick Road to become only the second undefeated Triple Crown winner in history.

Now 67, the most recognizable trainer on the planet is a two-time Triple Crown winner (American Pharoah in 2015), and had the fates allowed, could have been a four-time winner, save for Silver Charm losing the 1997 Belmont Stakes by a length and Real Quiet by an excruciating nose the very next year in a defeat that smarts to this day.

Still young at heart four decades after he began his career, Baffert has fond memories of Seattle Slew, who became one of racing’s giants despite being purchased for the miniscule sum of $17,500.

“I was 24 and still in college I think, but I saw Seattle Slew win the Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont on TV, even though I wasn’t into watching a lot of Thoroughbred races,” Baffert said. “I was still a Quarter horse guy.

“But when I saw him run, I knew the name, and it was a great name—one that stuck with you.

Seattle Slew in the stable area at Hollywood Park,1977.

“He was a most impressive horse, especially because in the paddock, he looked completely washed out but would run a hole in the wind.”

He would use up so much energy before a race and still destroy the opposition; and that’s a trait he throws (in his bloodlines).

“He ran as a four-year-old at Hollywood Park and got beat, and then I quit watching him because I lost interest after that. But to me, he was one of the greatest horses I ever saw run on YouTube.”

***

The following story is about Seattle Slew: part Seabiscuit, part Secretariat. It was published on May 14, 2002, but is appropriately resurrected here in advance of this year’s altered Triple Crown.

This is an exclusive firsthand interview the author obtained with the late Doug Peterson—a bear of a man who trained Seattle Slew in his four-year-old season and who provided a Runyonesque tale of the horse and those closest to him before his untimely death of an apparent accidental prescription drug overdose on Nov. 21, 2004 at age 53.

Seattle Slew being saddled in the paddock before the Swaps Stakes at Hollywood Park, 1977.

(Reprinted courtesy of Gaming Today)

Great race horses do not necessarily prove to be great stallions.

Citation and Secretariat were champions on the track, but each was a dud at stud. Cigar was a king on the track but fired blanks in the breeding shed. He was infertile.

But one Thoroughbred that succeeded on both fronts was Seattle Slew, who in 1977 became the only undefeated horse to win the Triple Crown.

One of racing’s all-time bargains as a $17,500 yearling purchase, Seattle Slew died last Tuesday in Lexington, Ky., exactly 25 years to the day of his Kentucky Derby triumph. He was 28 and still productive at stud, despite falling victim to the rigors of old age in recent years.

Seattle Slew in the stable area at Hollywood Park,1977.

His stud fee was $100,000 at the time of his death and $300,000 at its apex.

Here was a horse for the ages—the likes of which racing may never see again. Consider this: at two, he broke his maiden in his first attempt, and two races later won the Champagne Stakes; at three, he won the Derby, the Flamingo, the Wood Memorial, the Preakness and the Belmont.

At four, he won the Marlboro Cup, the Woodward and the Stuyvesant. He won the Derby by 1¾ lengths as the 1-2 favorite in a 15-horse field. Overall, the dark bay son of Bold Reasoning won 14 of 17 starts and earned $1,208,726.

Doug Peterson was a naïve kid of 26 when he took over the training of Seattle Slew from Billy Turner, who conditioned him for owners Karen and Mickey Taylor through the Triple Crown.

Now 50, Peterson is a mainstay on the Southern California circuit where he operates a successful, if nondescript, stable. But his memories of the great ‘Slew are ever vivid.

“I got Seattle Slew late in his three-year-old year, after he got beat by J.O. Tobin at Hollywood Park (in the Swaps Stakes),” Peterson recalled. “Billy Turner brought him out here, but he didn’t want to run him. As the horse was getting off the van and they slid up the screen door that was on the top of his stall, it fell down and hit him on the head.

“The day of the race he had a temperature. That’s why he couldn’t make the lead. There was no horse ever going to be in front of this horse, but despite the temperature, they ran him anyway because of all the hype and all the money and all the fans who wanted to see him. That’s what started the disagreement between the Taylors and Turner.”

Peterson got his chance to train Seattle Slew through a stroke of good fortune.

“I was in Hot Springs, Arkansas, sitting on a bucket,” Peterson said. “I was cold and down and out, and this girl—an assistant for another trainer—came by and told me, ‘If you’re going to make it big, you’ve got to go to New York.’ I packed up with two bums and went to New York.

“I got stables at Belmont Park on the backside of Billy Turner, but that was just a coincidence. Turns out, I was in the right place at the right time because Dr. (Jim) Hill was the veterinarian for Billy, and he came to my barn and I asked him to work on a couple of my horses.

“Dr. Hill recognized my horsemanship, and he and Mickey Taylor were buying 15 yearlings. They were going to need two trainers, and this is how the whole thing started. They said Billy would have a string and I would have a string. Well, before the next year, they fired Billy. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 56 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 56 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.95

Remembering Randy Romero

By Bill Heller

Hall of Fame jockey Randy Romero began winning races when he was nine years old—races at the bush tracks of rural Louisiana before hundreds of witnesses with lots of money on the line. If it was too much pressure for a little kid, he never showed it. He rode the rest of his life that way, seemingly impervious to the pressure of big stakes races and in defiance of a litany of serious injuries that would lead to life-long illness that he battled until the day he passed on August 29th.

He was 13 when he fell while working a horse and fractured his kneecap. Three years later, he had his first serious accident at Evangeline Downs. Another horse came over on Randy’s horse, who went down. Randy was trampled on by multiple horses. It punctured his lung, liver and kidney; and doctors would have to remove his spleen. He was unconscious for two days. When he awoke in the hospital, his mother begged him to stop riding. He told her, “Momma, I want to be a jockey.”

He was born to ride. When he retired at the end of 1999, he was the 26th leading jockey ever with 4,294 victories despite missing some six years from injuries. He won 25 riding titles at 10 different tracks including Arlington Park, Belmont Park, Fair Grounds and Keeneland.

What would his numbers have been if he only missed two or three years? Or if he hadn’t been nearly burned to death in 1983 in a freak accident in a sweatbox? Randy flicked off a piece of rubbing alcohol on his shoulder and it hit a light bulb and caused the sweatbox to explode. Randy suffered second and third degree burns over 60 percent of his body. Doctors gave him a 40-percent chance of surviving. He was back riding in 3 ½ months and won his first race back on a horse trained by his brother Gerald.

TO READ MORE - BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 54 (PRINT)

$6.95

ADD TO CART

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.9

A jockey's life: The true tall tales of gatebreakin' Ray Adair

By Peter J. Sacopulos

Like many baby boomers who entered their teens in the mid-1960s, Raymond Adair Jr. had an issue with his father. But it wasn’t a disagreement over long hair, rock music, or his choice of friends. The problem, in young Ray Adair’s eyes, was his father’s appalling ability to stretch the truth.

Ray Sr. claimed he began life as a foundling, left under a pinion tree by a band of Crow Indians before being adopted by a couple who ran a ranch in New Mexico. That was bad enough, but it was Ray Adair’s endless exaggerations about his horseracing career that really embarrassed his son.

In the elder Adair’s accounts, he won his first Thoroughbred race at age six. He lost a match race against the legendary Seabiscuit by a nose. He won the Bluegrass Stakes, finished second in the Preakness, and rode in the Kentucky Derby twice. He stood down gangsters and befriended greats like Eddie Arcaro. It was all too much.

“Growing up, I thought Dad was just a bullshitter. Or a horseshitter, anyway,” Ray Jr. says with a soft chuckle. “Imagine how I felt when I figured out all those horseracing stories were true.”

Throughout his childhood, Ray Jr. had been aware that his father was a jockey and horse trainer. His family, including his mother Evelyn and his older sister Rayette, had tagged along on the racing circuit for years. But Ray Sr.’s racing days and the Adair family’s nomadic ways came to an end in 1961. Evelyn had been diagnosed with cancer and could no longer travel. The family settled in Phoenix, and Ray Sr. hung up his silks and worked for a fruit distributor. Evelyn died in 1963, and Ray moved the family to Window Rock to work for his brother-in-law, who taught him how to operate construction equipment.

In Colorado for an unrelated job interview in 1964, Ray decided to call Thoroughbred breeder Conyer (“Connie”) Stewart. Connie Stewart had first seen Ray ride at the Jamaica Race Course in New York around 1950 (Ray Sr. sometimes said he first met Conyer Stewart in 1943. However, the Centennial Track did not open until 1950, making the late 1940s more likely). Deeply impressed, Stewart offered Adair a job as his jockey at the newly built Centennial Track near Littleton, Colorado. Adair and Stewart hit it off, but Ray, a top rider on the prestigious east coast circuit, passed on the offer. After he left the east coast in the mid-1950s, Ray did do some riding for Stewart at Centennial.

The day Ray called him, Connie Stewart answered the phone at his new Stewart Thoroughbred Farm. He immediately offered Ray the job of manager. Adair and his children came to live at the ranch, and Rayette and Ray Jr. attended school in Rye and helped out with the chores. Ray Jr. worked alongside his dad for four years, seeing firsthand how good his father was with horses. Ray Sr. seemed to have found the ideal life after racing—until he and Connie Stewart abruptly fell out.

“I never really knew why,” Ray Jr. says, but he believes it was likely due to a quirk of his dad’s personality. Raymond Adair Sr. could be as sweet as soda pop or as stubborn as a mule. “The same thing had happened with my uncle in Window Rock. Dad was a little guy, only five feet three,” his oldest son recalls. “He was sensitive about it, and I think it made him quick to jump to the conclusion that someone was trying to push him around.”

Ray Sr. left and took a job maintaining roads for the county. Not wanting to change high schools, Ray Jr. stayed on. It was while working for Connie Stewart that Ray Jr. began to realize his father’s fantastic racing tales were true. Ray Jr. would bring one of them up as an example of his dad’s penchant for telling whoppers, only to have Stewart say, “Actually, your dad did do that.” It would take many years and some research to get the full picture, but eventually, Ray Jr. and his relatives would marvel at the true adventures of the jockey known as Gatebreakin’ Ray Adair.

Those adventures began in the summer of 1928, when a Texan named Louie Kirk arrived in the town of Blanco, New Mexico, and entered a Thoroughbred stallion named Static in a match race at the San Juan County Fair. Kirk stabled the horse at the track, and found an eager, if unlikely, caretaker in six-year-old Raymond Adair. Small for his age but full of energy, Ray was growing up on a nearby ranch and had a remarkable knack with horses. The boy not only loved them, he seemed to understand and communicate with them in that special way that only a few people can. Little Ray Adair earned a half-dollar a day feeding Static, cleaning his stall and riding the horse to the river for water.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

August - October 2018, issue 49 (PRINT)

$5.95

August - October 2018, issue 49 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

The Legacy of El Prado

By Frances J. Karon

From the town of Cashel in County Tipperary, Ireland, at Lyonstown Stud, sprang a stallion that launched a breeding operation for Canadian entrepreneur Frank Stronach and has left an unmistakable mark on Thoroughbred racing.

Raced, like his sire and dam before him, by Robert Sangster, El Prado was trained on the holy ground of Ballydoyle by the incomparable Vincent O’Brien.

A son of Sadler’s Wells, in his day the leading sire in Great Britain and Ireland a record 14 times, El Prado caught the attention of bloodstock agent Dermot Carty.

To appreciate what El Prado has accomplished, one must recognize the brilliance of his sire.

Sadler’s Wells entered stud in 1985 to immediate success. Over time, he became the sire of 294 stakes winners, including 14 individual Irish classic winners, 12 classic winners England, and three classic winners in France.

But it was El Prado, foaled in 1989 from the brilliant Lady Capulet, that would travel his talents to North America and find a home in Kentucky as the stud who made Stronach’s Adena Springs an award-winning force in racing.

*

Charles O’Brien, an assistant to his father, trainer Vincent O’Brien, when El Prado was racing, looks back fondly on the young horse.

“He was not a very typical Sadler’s Wells and didn’t look like him,” recalled O’Brien. “Most of them were bay with white points, and he was grey and bigger and more substantial. Many were quite light-framed, but he was a big, heavy horse.”

O’Brien recalls putting a green El Prado through his paces.

“He wasn’t the two-year-old type but he had such a good constitution that we just kept moving him up in his work, and he thrived on it and just kept going, although he didn’t really have the physique of a sharp two-year-old,” said O’Brien.