How stud farms determine stallion fees

Article by Jennifer Kelly

The end of the year brings magical seasons like the Breeders’ Cup, winter holidays, and in horse racing, a cascade of retirements as prospective stallions and broodmares exit their careers on the track for the next phase. This is when the sport goes from wagering on races that last minutes to one that lasts years, a bet, a wager that pedigrees, physical attributes, and on-track performances will translate to the breeding shed.

That wager hinges on a mix of knowns and unknowns; a test of how to transition a stallion from athlete to producer, balancing husbandry and business acumen, aided by tax incentives and the lure of opportunity in an ever-evolving marketplace.

*************************************************************

The first Thoroughbred stallion imported to the United States was Bulle Rock, a son of the Darley Arabian out of a Byerley Turk mare, who arrived in Virginia in 1730. A century later, Glencoe, broodmare sire of Kentucky and Asteroid, landed on American soil in 1836. In those early eras, transporting horses was a challenge, so a stallion would stand in one location, servicing mare from the immediate area before being moved to a different farm the following season.

As transportation improved, the process reversed. An owner could keep their stallion at their farm, inviting broodmares to come to him. Sole owners and breeders like Samuel Riddle, who stood Man o’ War, could control the size of their stallions’ books and the quality of the mares admitted to the breeding shed. Income from stud fees went directly to the owner, along with the tax burden.

As stallion prices rose, sharing financial responsibility – i.e., purchase price, veterinary care, board, fertility insurance – became appealing. Syndicates allowed partners to share costs while also ensuring sustained demand for that sire’s services. Shareholders, often broodmare owners themselves, could use their breeding rights or sell them and later decide to retain and race the foal in their colors or sell it to recoup some of their expenses.

One of the earliest syndicates came in 1925, when Arthur B. Hancock of Virginia’s Ellerslie and Kentucky’s Claiborne Farm joined forces with William Woodward, Marshall Field III, and Robert Fairbairn, all of whom had breeding programs of their own, to purchase Sir Gallahad III, a stakes winner in England and France. The group pooled $125,000 to bring the son of Teddy to Claiborne, where he went on to sire Triple Crown winner Gallant Fox along with classic winners like Gallahadion, High Quest, and Hoop Jr.

By the 1950s, syndicates had become more common as breeding in the United States started shifting toward farms standing multiple stallions, often owned by groups of up to 40 shareholders. That number, said Headley Bell of Mill Ridge Farm, was based on the idea that “if a stallion were turned out in a herd of mares, that 40 would be a natural herd for them.”

“Horses stood on syndicate agreements, which were very refreshing in that there generally were 40 or 45 shares in a horse, and breeders were limited to one Northern Hemisphere season,” said Michael Hernon of Hernon Bloodstock, who recruited Tapit for Gainesway Farm. “Now, this would be horses like Nijinsky, Mr. Prospector, Danzig, and the like. Because of the limitation in the supply of the product and the success of those horses in the commercial market, their fees became quite significant. But that resulted from the fact that the supply was so controlled. Over time, somewhat regrettably, we started to move away from syndicate agreements.”

Today, syndicates remain a viable way to launch a new stallion, but outright ownership by major breeders like Coolmore and Spendthrift, has become more common. With previous owners often retaining a share, these arrangements—combined with the commercial market’s expansion—have fueled book sizes that now exceed 200 mares. The Jockey Club’s 2024 Report of Mares Bred listed ten stallions that covered 200+ mares.

In 2025, commercial consideration drives much of the decision making. Farms that bring on new stallions choose between syndication or outright ownership, reflecting an industry increasingly oriented toward breeding to sell.

*************************************************************

At Fasig-Tipton’s The Saratoga Select Yearling Sale in August and then the Keeneland September Yearling Sale, the top sellers came from established stallions Gun Runner and Into Mischief. First-crop sires like Flightline, Life Is Good, and Mandaloun also made headlines, each with yearlings selling for seven figures, led by 2022 Horse of the Year Flightline with 10 total. Flightline also commanded $2.5 million for a share at the 2024 Keeneland Championship Sale at Del Mar, underscoring how lucrative new stallions can be.

With stallion ownership generally falling into the categories of syndication or sole ownership, breeders no longer need to stand and support stallions entirely on their own. Sole ownership allows breeders like Spendthrift to control a stallion’s book and retain the earnings, though it also carries the preponderance of the risk.

“We generally own a stallion outright,” said Ned Toffey, Spendthrift’s general manager. “Very often, the people who've raced a horse are interested in retaining some percentage. That's generally something that remains on the table for us. But the majority of our stallions, we own all or most of.”

For farms like Claiborne, syndication remains the preferred model: “It's a lot of money to bring in these high-dollar stallions, and we can't do it all ourselves,” observed Claiborne president Walker Hancock. “We rely on some great shareholders and syndicate members to help us stand the horse and make the purchase possible. It has evolved over the years. This year, we did our first 50-share syndicate, which we've never done before.”

Ocala Stud favors partnerships over syndication. “We like to partner. We have syndicated horses in the past, but it's been a long time since we've done so,” said David O’Farrell, Ocala Stud’s general manager. “As the Florida Breeding Program has waned over the years, we just feel like there's fewer people that would be willing to participate in a syndicate. It's worked better for us to have partnerships, whether it be four or five different partners that invest in a stallion and then support the horse with mares.”

Regardless of the ownership structure, adding a new stallion relies on two factors: the stars of the racing year and the relationships each farm has nurtured over time. This process can begin months or even years before a potential stallion retires from racing. As Hernon observed, “lately, the demand for a young, appealing horse starts coming into focus earlier, and the horse starts to be pursued from that point of view. Then, conversely, some of them might come down to a career-ending injury that forces the horse to come out of training.”

The challenge remains identifying stallions whose on-track appeal will translate to the breeding shed. As Mill Ridge’s Headley Bell put it, “now you're starting a whole another purpose for this horse and you're redefining what this horse is going to look like. If we believe in him and in his potential as a stallion, we have to give him the best chance. As in, it's not just buying that horse, it's will the market support the horse so people will send mares?”

What are farms looking for in a potential stallion? Hernon identified four factors: “the pedigree, the physical, the performance, and those combined will lead you to the price. And then, of course, the stud fee will ultimately be determined by how much is paid for the horse. The farm has to try and structure the deal whereby they can get enough representation of mares underneath the horse to give them a chance and try and recapture their expenditure before the horse becomes exposed with his first couple of crops on the racetrack.”

Farms must consider not only who is available in a given year, but also who is already in the shedrow.

“We probably wouldn't go after two sires of the same caliber, like the same distance, same surface, same sire line, so we do try and differentiate between that,” noted Hancock.

Sequel Stallions’ Becky Thomas looks for “a sire line that I respect. Our last stallion that we brought to market was Honest Mischief, of course. He’s the leading sire of his group. I try to model our program up of what I feel like is brilliance. At some point in time, I want to see that you displayed something that was different than a lot of the other stallions.”

For programs like O’Farrell’s, a stallion is just the beginning of their investment. They maintain a broodmare band of about 50, raise the resulting foals through their two-year-old year, sell them essentially as ready-made racehorses.

“It really comes down to, do we feel like we can get a runner? And do we feel like that we can market these horses at the two-year-old sales in three years? It’s a huge investment for us, carrying them to the two-year-old sales,” O’Farrell shared. “You've got a significant amount of investment in that broodmare, and so you better believe in the stallion because you're carrying the output for so long.”

Once a farm identifies a candidate, the challenge is turning successful racehorse into a successful stallion and doing it quickly enough to ensure long-term commercial viability.

*************************************************************

Farms take different approaches to ensure a prospect transitions into a pro. For Spendthrift, “our goal is to add at least one, if not several, stallions every year. That's basically because we understand that the simple odds are that most stallions are not going to be successful,” Toffey said. “Our mindset is that we have to continually try to bring in new horses to continue to build the roster and to replace the ones that are not making the grade.”

Other farms, especially regional ones like Ocala Stud, do not add a new name every year. “We’re not always in the market for a new stallion because we can't justify bringing one in and standing them for enough money,” O’Farrell observed. “It's hard to justify it from a stud fee perspective. When we look at stallions, rather than doing the math of seeing what it would take to get out in three years, our philosophy is more, would we be willing to breed 15 good mares to the stallion in the first two years?”

Bringing on a new stallion carries significant costs, including fertility insurance, board, veterinary care, and marketing. Such a significant investment requires the stud fee be calculated carefully. Price the stallion too high and breeders may shy away; too low, and it can signal a lack of confidence. “The objective of every farm is to get mares to the stallion. When you set the stud fees, you’re basically taking a wild guess,” O’Farrell explained. “Obviously, it comes down to what you paid for the horse. Not that you need to get that money back in three years, but you need to price him to where you feel like he can be competitive.”

The stud fee also affects long-term viability. “It's become expensive now to board a horse and pay the insurance and the associated vet work. We're in a different world now. The in-vogue stallions are highly in demand and they're going to cost a lot of money,” Hernon observed. “It's a catch-22 because the farms who buy them, based on purchase price and the demand and the competition for said horses, will determine a high dollar value on the horse to secure them. Consequently, the farm has to breed a significant number in order to make the figures work, and recapture most of their investment.”

Setting that fee is not formulaic; it is nuanced. “It's not just one or two Grade 1s equals X stud fee,” Toffey observed. “What did they do at two? What did they do at three? How did they win their races? Who did they beat? Who is the sire? What is the female family? How did they win their races? Were they the favorite every time or were they 20 to 1 and came out of nowhere? There's a lot of variables that go into building it.”

For farms like Mill Ridge and their stallion Oscar Performance, a horse that the Amermans bred and raised at the farm, Bell emphasized collaboration. “We've got to do this together. Our objective isn't to make him worth the most valuable today. We have to make him valuable down the road. In order to do that, we're going to have to be reasonable in how we price this horse because those 20 shareholders end up being your partners. You're asking them not to support this horse in the first year; you're really trying to provide incentives to them to support them in the first through fourth year, at least.”

Spendthrift and similar stud farms take a proactive approach when it comes to promoting new stallions because perception drives demand. “Since a huge percentage of the breeding market today are commercial breeders, when they look at a horse, they got to feel like, ‘This is a horse that I can use and have some success with,’” Toffey shared. “Either it's going to work well with my mare, it looks the part, or ‘Hey, look, people are really going want to buy these horses, buy this horse's offspring, so they're going to be commercially viable.’”

Commercial viability often comes before racing ability. Buyers, whether mare owners, pinhookers, or racing managers, rely on tangible factors like pedigree and physical attributes when deciding whether to invest in a stallion’s progeny. Bringing on a new stallion means not only covering the costs of a mature horse but also attracting customers for his services—that is marketing.

For a horse like Flightline, an undefeated Horse of the Year, marketing is easier. For others, farms use in-house marketing teams or public relations firms.

“Every horse has strengths and weaknesses, and we, go back to the old expression, accentuate the positive. We want to look at what messages will resonate with breeders,” Toffey said. Spendthrift brands each stallion individually, developing logos and merchandise, as do other farms like Claiborne and Lane’s End.

Other breeders take a lighter approach. “Our philosophy is, if you stand horses, if you stand a quality stallion at the right price, that is going to be the best advertisement,” O’Farrell observed.

Marketing, along with the stud fee, ultimately affects book size. In 2024, 64 first-year sires covered a minimum of five mares, with four—Gunite, Elite Power, Pappacap, and Taiba—servicing 200 or more. That’s just 6% of the total. Other stallions with large books, like Justify, Gun Runner, and Vekoma, had multiple breeding seasons under their belts. Book size reflects more than stud fee; it also depends on the stallion himself.

“Horses, like people, are different. They're made different. They have different characters, different DNA. They're not all equal on the racetrack, and they're certainly not all equal in the breeding shed,” Hernon observed. “Horses have different levels of libido and fertility, and some have a limitation in the number of mares they can comfortably breed in a season. Newer stallions, they don't know what they're doing, and they have to be taught.”

While breeding a mare may seem an instinctual undertaking for a horse, in reality it is a skill no different than teaching a horse to accept a rider and then to race. Farms may limit a new stallion’s book to allow them a chance to learn. Overbreeding a horse can be as problematic as over racing, because it can affect their confidence and create challenges for a stallion manager.

“Often, what we do with our first-year horses is we start them a little bit lower to make sure that they can handle [the job.] Not every horse can handle 180, or 160, or 150. So the first year, we're going to try to keep them down below 200,” Toffey observed. “There's some things we can do to estimate those things beforehand, but you really never know until you get into breeding season. It's a case-by-case basis.”

Some farms maintain each stallion’s book at a set level but have adjusted over the past 25 years to remain competitive. “We used to cap it at 140, but we felt like our stallions were at a bit of a competitive disadvantage with other people breeding theirs to 250 plus,” Claiborne’s Hancock shared. “In order to keep up, we have raised our book size to about 175, 180. Now, I don't anticipate going over that. I think our stallions can comfortably handle breeding that many mares.”

A farm’s book policy can influence where a stallion stands or where breeders send their mares. “Breeders will just have to choose what farm policy of numbers of mares on the book that they're comfortable with, and that can predetermine their choice as to stallion and where they might breed,” Hernon observed.

Technology has also reshaped book management. Broodmare managers have tools like drugs to help a mare ovulate at a more ideal time and ultrasounds able to show finer details, enabling veterinarians to gauge the size of an ovarian follicle and predict more precisely when a mare might be ready to breed. Whereas in previous decades, a mare might need to be covered twice to ensure that they catch, such advances can increase the chance a stallion impregnates them on one.

“We're now able to do book sizes with the assumption that mares don't need to be doubled. Whereas it used to be not uncommon to have to double a mare on a heat cycle. Now it still happens, but it's rare that we have to double a mare. That alone opens up so many more spots. We're able to be way more efficient with the use of a stallion,” Toffey said.

Even after identifying a stallion prospect, negotiating a deal, setting a stud fee, and filling the book, doing it outside Kentucky, which remains the heart of American breeding, can be challenging, even in established regions like California, Florida, and New York.

*************************************************************

Even generations of experience in the sport does not insulate a farm from the realities of the modern bloodstock marketplace. David O’Farrell, the third generation at Ocala Stud, acknowledges the challenges: “Look, there's no question that Kentucky is the center of commerce in the Thoroughbred world and will be for a very long time. It's getting tougher in the so-called regional markets. But I do think there's a very good opportunity in places like Florida, where people that are investing and doing business have the opportunity to win these [breeder] awards, even though they might not be as lucrative in Kentucky.”

Becky Thomas of New York’s Sequel Stallions takes a similar approach: “Our stallions in New York cannot compete with the stud fees that Journalism and Sovereignty are going to demand. So we do not compete at that level, and most people in Kentucky cannot compete at that level. We try to be competitive with our like class level.”

For Rocky Savio of Savio-Cannon Thoroughbreds, moving their stallion Smooth Like Strait, from Kentucky to California might go against conventional wisdom, but the move was strategic. The stallion’s foals can be raced at his owners’ home tracks, as well as take advantage of the California-bred incentive program.

“We feel familiar with this scene. Michael [Cannon] and I have been going to Del Mar for the past 30 years of our lives, and Smooth Like Strait did most of his racing and winning on the West Coast. He's a California horse,” Savio shared.

In September, the California Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association announced a bonus increase for Cal-bred winners of maiden special weight races at 4 ½ furlongs and longer in both restricted and open company, adding $2,500 to both bonus for races at Santa Anita and Del Mar. Starting with the 2026 crop, the CTBA also instituted a $1,000 bonus for each registered state-bred foal up to 25 foals per CTBA member breeder. Additionally, the organization provides a transportation reimbursement up to $3,000 for mares 12 years old or younger purchased for $20,000 or more out of state and then bred to a California stallion.

“Obviously, another reason why we're going to California is for the Cal-bred bonuses.

That's why we made the move,” Savio shared. “I know everyone's moving the other way, and we're going against the grain of what's actually happening. But I think there's something left there that is beneficial to an owner.”

Regional programs in California, New York, and Florida offer awards for breeders and stallion owners, plus stakes races restricted to state-breds. The New York Racing Association is even moving toward full purse parity for state-bred races by 2027, while Florida adds incentives for state-breds at select out-of-state tracks in 2026.

Even with these incentives, programs like Sequel and Ocala Stud must compete with Kentucky, especially given the commercial market growth. As such, stud fees have to be competitive in states where the margins are slimmer and even a thousand dollars can make or break a stallion’s season.

“You have to understand your market. If they're not selling, then you've got a price that is too high. If they're selling too much, then you've got a price that’s too low. So you have to feel the market out a little bit. And it's incredible how much a $1,000 price point makes a difference in a market like Florida,” said O’Farrell.

Thomas sees that “New York is somewhat of an island, but really, we are part of an international business. I don't want to bring stallions to market that I don't feel like have a domestic as well as international feel if they hit. I mean, there's no stallion that's popular past the freshman year unless they hit.” Because it remains a top-tier racing hub, owners still flock to the Empire State to compete in its lucrative and famed tests. With the coming purse parity and the new Belmont Park, breeding, selling, and racing in New York is full of financial opportunity beyond purses.

Additionally, as O’Farrell points out, for regional farms like his to send mares out of state is not cost effective.

“That's what's killing the business in the regional markets, in my opinion,” O’Farrell said. Everybody wants to access the Kentucky stallions. But when you have a farm and you have to pay somebody else to care for your horses and you don't have control over them, it's a huge problem. It makes it harder to be a breeder when you're also paying another farm to take care of your mares.”

With that in mind, collaboration between racetracks and breeders is key to regional markets, “They need the product. We need the races. So it is very much a partnership,” said Thomas. “And I think we, on both sides, need to continue to be excellent partners and grow the program.”

“Those factors are extremely significant because we need a breeder base far beyond what you see in Kentucky because there's a lot of our commercial New York breeders that breed outside of New York as they have resident mares, and they're still a registered New York bred as long as you follow the rules of the program. We don't just compete within New York; we compete within the whole domestic market.”

Regional breeders still feel pressure to compete with Bluegrass stallions, balancing stud fees and acquisitions to stay viable. That means sending mares to Kentucky despite the costs, “something that's not talked about enough,” O’Farrell said. “I think that you have to find a way to lessen the burden for people who have farms in these regional markets to access those types of stallions. Because there's no question, the industry has gone more towards a flight to quality. You’ve got to let people want to try to improve their breeding programs, but you can't have it so burdensome to where they have to pay for their farm and pay for other people's farms, too.”

As Savio observed, “our industry is filled with guys like Michael and I, people with one or two stallions, trying to make the right decisions. Once you get to the middle and the bottom of the sport, it's just people trying to make the right decisions. Not everybody's a Gun Runner or an Into Mischief, or even some of those top 25 horses. Everybody else is fighting for the same dollar. And it's very hard.”

Those decisions can make or break farms in regional markets, especially in light of the stiff competition they face in the ever-present and all-encompassing commercial markets. State breeding programs and federal benefits like bonus depreciation help breeders like the O’Farrells, Rocky Savio, Michael Cannon, and others stay close to home and still compete across the country.

*************************************************************

The 2025 Keeneland September Yearling Sale capped a blockbuster year for bloodstock. Fasig-Tipton’s Saratoga Select Sale posted 25 seven-figure yearlings out of 166 sold, while Keeneland saw 57 seven-figure yearlings among 3,076 lots. Saratoga grossed a record $100,715,000, up 22.6% from 2024, while Keeneland hit $531,634,400, up 24% from its 2024 record.

One factor driving this year’s records includes recent legislation which reinstated bonus depreciation, a tax benefit that the federal government had been phasing out until this past July.

“Depreciation is just a fancy term for when I can write off or deduct the purchase price of assets that I buy and I use in my business,” said accountant Jen Shah.

In the long run, this 100% bonus depreciation means that a farm can write off that expenditure the same year, thus reducing their tax burden. That means more cash in their pocket to spend, which means more capital to burn. But the deduction only comes that first year, so “you have more cash in your pocket sooner because you've reduced your tax burden” so long as that horse is available for whatever purpose the buyer intends, in this case, for stallion services.

“It doesn't have to necessarily be bred, but the horse has to be available to be bred. Now, you would never breed a horse in the fall in the Northern Hemisphere, but it does have to be retired from racing before year end in order for you to say that that horse is placed in service,” Shah shared. The goal of this tax benefit is to encourage investment in American assets. In this case, that includes stallion prospects.

As Headley Bell points out, the federal government was already a willing partner to the sport, but these changes give breeders something they always need more of: time.

“Uncle Sam is really our best partner. If you look at the business, in my opinion, the depreciation and things we have are extraordinary,” Bell observed. “Because it's a hard business, you have to demonstrate that you are trying to run it as a business in order to take advantage of it. But it allows you to buy time and offset other income or revenue, so you have to try to position yourself to get lucky. You can't just keep on going down that road of losing money, so this allows you to buy time. And in this business, buying time is the best thing you can do.”

As Hernon pointed out, the end result is that “people are willing to pay more money for what is perceived to be good prospect. And there's a lot of money that's come into the market.” With so much liquidity, “people are more aggressive spending this year under the current tax law situation. Now, if that remains constant, that's to be determined.”

Another issue at the heart of these recent record sales is the concentration of sire power to a vaunted few, which narrows the genetic diversity of the Thoroughbred. The origin story of the breed starts with the Byerley Turk, the Darley Arabian, and the Godolphin Arabian. Through selective breeding first in England and then here, both the Byerley Turk and Godolphin Arabian lines are on the outside looking in, with the Darley Arabian line becoming most prominent in the United States. Some of this shift comes from the influence of the commercial market on breeding in the last 25-50 years.

“We have two sports today. We've got racing and we have sales, and each are highly addictive. There's a huge amount of a drama attached to both spheres, and the sales are like the gladiator's ring, I suppose. It's highly charged,” pedigree expert and author Suzi Prichard Jones observed. “Owners probably get to play more of a role in the whole sales saga than they do on the race course. There's intrigue. ‘Who's on this horse? Who's bidding? So and so looked at it. We'll bid this much.’ It's a game, and It's very addictive. People are breeding horses and buying horses accordingly.”

Often the reason why certain lines dominate over others is directly related to results on the racetrack as well as intangibles like temperament. Certain sire lines, most notably the Byerley Turk, were known for an abundance of spirit, which has led some breeders to prefer horses who are easier to handle. However, the long-term effects of allowing the commercial marketplace to inform breeding choices are still unknown.

“The reason these horses are commercial is because they've bred successful racehorses and they're producing successful racehorses,” said Prichard Jones. “Nobody's doing anything wrong. But when you take a deeper dive, and you look at the genetics and the pedigrees behind them all, you have to raise the question, is this a good thing?”

“If we need that diversity, then we're going to find out to our detriment in 20 years’ time, because then every Thoroughbred will be descended from Phalaris, who was a horse born in 1913. It's going to be interesting just to see how it goes.”

This focus on the commercial is a pivot from the sport’s origins, where families with names like Whitney, Woodward, and Stanley were able to breed to race, their eye on the results on the racetrack rather than the results in the sales ring. This shift has pushed the issue of genetic diversity in the Thoroughbred to the side, with the issue of pedigrees focused more on the productive sire lines rather than the overall genetic health of the breed.

“There are very few people who actually make money in this game. For a lot, it's a lifestyle. They just keep their heads above water. Maybe one year you have a good year, the next two or three years, you just eke along, and then you have a really bad year, and then maybe you have a really good year again,” Prichard Jones observed. “And that's how it goes. We love these horses dearly and we're addicted to them. This is a dreamer's game.”

*************************************************************

Breeding is not for the faint of heart. Declining foal crops, shrinking markets, and high expenses challenge even experienced operations.

“That's the challenge of today’s ‘commercial market.’ These stallions are getting so many mares in the first year that it's harder for these other potential stallions to get enough mares to be able to give them a chance,” Bell said. “That's the crossroads we are today, the commercial market driving these stallions.”

With more than half of all foals born in the United States going through the auction ring, the pressure to produce horses that offer breeders high returns in sales makes bringing a new stallion to market a gamble not everyone can afford. As with any given race day, when even a longshot has a chance to win, predicting which stallions will hit and which will miss is often the biggest bet.

“Mr. Hughes used to love to say about this game, ‘Nobody knows.’ I think it's particularly true about standing stallions,” Spendthrift’s Toffey observed. “I don't think there's any better illustration than that.”

Staying Close to Home: Cynthia McKee Continues a Legacy of Success in West Virginia

Article by Jennifer Kelly

Of the twenty-seven states that are currently home to Thoroughbred racetracks, twenty also feature state breeding programs, incentives meant to reward breeders for keeping their bloodstock close to home and owners for racing their horses in their birth state. The money generated supplements purses and enables both groups to invest more in the places they call home.

For Cynthia McKee and Beau Ridge Farm, benefits like the West Virginia Thoroughbred Development Fund have allowed her and her late husband John not only to put down roots in their childhood home but also to flourish, building a program that has brought them success in the breeding shed and on the state’s racetracks.

Mountain Mama

Cynthia McKee’s roots in West Virginia racing date back to the opening of Charles Town in 1933, long before the breeder/owner/trainer herself was born. Her father Charles O’Bannon was a 14-year-old boy watering the horses that pulled the starting gate when the racetrack opened and worked his way up to track superintendent, a position he held for more than 40 years. For the O’Bannon family, the sport and the equine athletes were a way of life, making McKee’s lifelong devotion to both a natural progression.

“My dad was the track superintendent, and my mom, she worked part-time in the admissions. I just grew up around horses and I liked them,” she recalled. “I guess I was five or six, and I got my first pony. My dad did a lot of stuff with the 4-H Pony Club around here.”

From there, McKee graduated to show jumping, “but I couldn't make a living with show horses. I wanted to stay with the animals and the racing was the only way to do it.” First, she galloped horses and then went to work for Vincent Moscarelli, who along with his wife Suzanne bred and raced horses in the state, their Country Roads Farm producing Grade 1 winners Soul of the Matter and Afternoon Deelites for Burt Bacharach. It was Moscarelli who gave McKee a chance to take charge of his barn when he went away for a few days. “He came back, and he said he really thought he'd leave again because I'd won quite a few races,” she recalled. “He did it again the following year. But by then, I had started dating John [McKee].”

Raised in Kearneysville, John McKee graduated from Charles Town High School, served in the Navy, and then returned to the area to raise and breed Black Angus and Pinzgauer cattle. He started training racehorses in 1969 and bought the original Beau Ridge Farm near Bunker Hill in the early 1970s. By the latter part of the decade, he was racing in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and his home state. He met the former Cynthia O’Bannon through the racetrack when her hunters happened to be stabled in his barn:

“He said to me one day, he said, ‘Wouldn’t you rather have your two horses on a farm somewhere and you could move your jumps out there? I'd really like to have some more stalls. They just don't have any more stalls. You could just move your horses up there and set your show jumps up in that field,’” she recalled. “I moved my show horses up to his farm and he raced horses in my stalls. And I guess that's how it started because I was up there every day taking care of my horses and riding.”

From there, John McKee and Cynthia O’Bannon were partners in breeding, owning, and training horses, making their home at Beau Ridge and taking turns traveling to tracks like Atlantic City to race their horses. They later moved to Kearneysville, where the couple built a three-furlong training track and a breeding program that has become quite the juggernaut for the Mountain State. In addition to their 170 acres, the McKee’s greatest investment to this point has been the stallion Fiber Sonde.

A Foundation Named Fiber Sonde

Bred by Aaron and Marie Jones, Fiber Sonde is a 2005 foal by Unbridled’s Song, sire of Arrogate and Liam’s Map, out of the Storm Cat mare Silken Cat. An incident with a fence left the colt with a broken shoulder, keeping him off the racetrack; John McKee then bought the two-year-old prospect at the Keeneland November Sale in 2007 for $8,000. The couple opted not to race him and instead sent him to stud at Beau Ridge. The gray stallion went on to become a superstar, topping the state’s sire list from 2018 to 2023 and finishing second to Juba in 2024 despite the 20-year-old’s fertility issues.

“We can only breed him once a day, and I try to be very selective with him,” McKee shared. “I don't breed too many outside mares, but the people that supported us from day one with him, I still let them breed some. Indian Charlie is a really good cross with him, so we've bought a few Indian Charlie mares over the years. Distorted Humor also is a good cross with him. Those mares are going to come first.”

The most notable successes for the Fiber Sonde pairing with an Indian Charlie mare include four of his foals with the mare Holy Pow Wow: Late Night Pow Wow, Muad’dib, Duncan Idaho, and Overnight Pow Wow. Racing for Javier Contreras and Breeze Easy, Late Night Pow Wow became the son of Unbridled’s Song’s only graded stakes winner when she took the Grade 3 Charles Town Oaks in 2018 and the Grade 3 Barbara Fritchie at Laurel the following year. The mare also had five black-type stakes wins, including the Cavada, one of the nine stakes on the West Virginia Breeders’ Classic card.

Local trainer Jeff Runco purchased both Muad’dib and Duncan Idaho for owner David Raim. The former was second in the 2022 edition of the Grade 2 Charles Town Classic and won the Sam Huff West Virginia Breeders’ Classic Stakes the same year in addition to two other black-type stakes victories. Duncan Idaho captured the WVBC Dash for Cash Stakes this past October.

The McKees also bred Overnight Pow Wow, a 2021 foal that Cynthia convinced her husband to keep rather than sell as they had done with other Fiber Sonde-Holy Pow Wow foals. “He was more for selling than me,” Cynthia reflected. “I don't like selling them.” Her instinct to keep the filly has reaped rewards, though John McKee, who passed away in early February 2023, missed out on Overnight Pow Wow’s thrilling start to her career. The now four-year-old amassed eight wins in 11 starts in 2024, including a win in the WVBC Cavada against older fillies and mares in addition to her two black-type wins at their home track. The success of the Fiber Sonde-Holy Pow Wow’s pairing made the mare’s untimely death in late December a bitter pill for McKee.

“The only thing I could tell you is, when that mare died, it like to kill me,” she shared. “I cried for a week. I was going to sell everything and move to Charleston, South Carolina, and retire on Folly Beach. Then I got to thinking about Fiber Sonde and our many other mares. This is home.”

Beau Ridge is also home to five other stallions, including Redirect, another unraced prospect that could pick up where Fiber Sonde leaves off. McKee’s Direct the Cat, who has two WVBC stakes victories already, is a daughter of Redirect out of the Fiber Sonde mare Cat Thats Grey, another WVBC winner who has also become a producer for Beau Ridge: her 2022 colt Im the Director won last year’s West Virginia Futurity, and her 2017 gelding Command the Cat was black-type stakes placed. A son of Grade 1 winner Speightstown out of the Seattle Slew mare alternate, Redirect stands for the same stud fee as Fiber Sonde, $1,000. That fee remains unchanged for 2025, allowing both to stay competitive in a state where the breeding reward program is such a draw.

“To me, the money is in the development fund awards,” McKee said. “So, the more [mares] I can get to them, the better.”

Mountain State Racing

The state currently boasts two Thoroughbred racetracks, Hollywood Casino at Charles Town Races, located near Charles Town in the state’s eastern tip, and Mountaineer Casino Racetrack and Resort, in Chester, near New Cumberland in the Northern Panhandle. These two racetracks hosted 285 race days in 2023, with 2,300 races total and an average field size of 7.4 horses.

Both tracks currently have casinos in addition to their racing facilities, their revenues providing more than $1 billion in funds for purses since the state legalized video lottery machines in 1994 and then added table games in 2007. The state also sets aside $800,000 in purse money for more than a dozen state-bred stakes, including the West Virginia Futurity for two-year-olds at Mountaineer, the Sadie Hawkins Stakes for fillies and mares three years old and up at Charles Town, and the Robert G. Leavitt Memorial Stakes for three-year-olds, also at Charles Town. Both racetracks write one to three races per day for accredited state-breds as well.

Additionally, the West Virginia Thoroughbred Development Fund, established in 1983, incentivizes breeders and owners to not only breed in the state, but also to race there, paying a percentage of the accredited horse’s earnings at the state’s racetracks. Each year, breeders get 60%, owners 25%, and then 15% goes to the owners of the winning horse’s sire. To qualify, the horse’s breeder must be a resident or keep their breeding stock in the state, or the sire must be a resident of the Mountain State.

The Supplemental Purse Awards program, also known as the 10-10-10 Fund, distributes up to 10% of the winner’s share of the purse to the owner, breeder, and/or sire owner of an accredited state bred and/or sired winner. In all, the WVTDF awards up to $5 million to breeders, owners, and sire owners of state-bred or -sired horses that earn money at the state’s two racetracks. For Beau Ridge and McKee, this kind of money not only rewards their bloodstock investment in the state but also allows them to concentrate their racing there.

“We get around a large check in February every year. If that horse makes a penny and it's by my stallion, then I make a penny. It's based on your horse versus what other horses earn,” McKee shared. “The purses come here and there, and then the development fund, you get this big chunk of change all at one time. I tried to put enough away that I could operate for five weeks without having to touch any savings. Because you know in this business, you can be on top of the world one minute and you're bottom of the heap the next time.”

In a state with a population of 1.77 million, one that has sustained racing for more than 90 years, the Thoroughbred Development Program shows that “at even one of the smaller racetracks, that you can be successful,” McKee observed. “You don't have to be on the center stage to be successful. Do we make the money they make in New York and California? No. But even the little man that's only got one horse, he's going to get that check in February, too.”

No matter the size of the operation, whether it’s Beau Ridge with their six stallions, 30 mares, and racing stable of about 35, or a smaller operation, the state wants them to breed and race there and programs like the WVTDP enable that grassroots investment that keeps these circuits going. “Most are investing it all back in the industry, and they're excited to be a part of it,” McKee said. “A lot of them pay all their bills off then. It wipes the slate clean, and we can play again.”

Between Mountaineer and Charles Town, the Mountain State will see upwards of 280 days of racing in 2025, with at least one race written for state-breds each day. In addition to the plethora of racing days and the WVTDF, the West Virginia Breeders’ Classic card provides stakes opportunities for state-breds each autumn; modeled on the Maryland Million, this special night of racing was the brainchild of the late Sam Huff, former NFL player and breeder. All of these encourage stables like McKee’s close to home rather than traveling to Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and beyond: “I haven't [raced elsewhere] much lately because of the breeding program. I mean, I almost lose money going out of state,” the trainer shared.

John’s death in 2023 has kept the former Cynthia O’Bannon at Beau Ridge more than ever. This native daughter remains focused on the sport in her home state, putting her time and energy not only into promoting the breeding program that sustains her but also continuing the program that she and her late husband spent years developing.

Balancing Act

When Cynthia O’Bannon met John McKee in the late 1970s, they developed a partnership that lasted nearly 50 years. By the time the couple decided to build a life together, he had purchased Beau Ridge and started investing in bloodstock, determined to breed good horses and then race them. From there, the couple would take turns traveling around the Mid-Atlantic, starting horses at racetracks in Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia.

In later years, they consolidated their racing to their home state and brought on stallions like Fiber Sonde, building their broodmare band to capitalize on their pedigrees. The couple became involved with the West Virginia Thoroughbred Breeding Association, John serving as a past president and Cynthia now occupying the same position. John’s passing at age 83 left both his wife and his farm bereft of the guiding hand that had been at the helm for so long.

“When he first passed away, I wanted to go to bed and pull the covers over my head. I couldn't do it,” McKee shared. “But I had all these horses. I had employees. I had to go. And thank God that I did. Because if I would have sold everything, probably two or three months later, I'd be so damn bored, I wouldn't know what to do.”

Crediting her late husband as her training mentor, Cynthia McKee continues running Beau Ridge and their racing stable, wearing the mantle of owner-operator, saying that “I just found that it’s easier if I do it myself.” She oversees 12 full-time employees between both facets of her business, which includes not only boarding many of the mares that her stallions cover but foaling them as well. She has also focused on cutting down the farm’s broodmare band: “There were 60 some mares here when he passed. I do have it down to 30. I'd like to cut it down to about 20 mares and maybe 20, 25 in training.”

Though she downplays her training skills – “I always tell everybody [John]'s a better trainer. I'm a better caretaker” – McKee had her best years as a conditioner yet in 2023 and 2024, earning $829,141 and $972,117 and finishing with a win percentage of 22% and 20%, respectively. This comes on the heels of her husband’s best years in 2020-2022, three seasons where they earned more than $1 million each year. She won two West Virginia Breeders’ Classics in 2023, with No Change taking the Onion Juice and Direct the Cat winning the Triple Crown Nutrition Stakes, and then four in 2024, with Catch the Humor, Direct the Cat, No Change, and Overnight Pow Wow. As the 2025 racing season begins, she looks forward to more from Overnight Pow Wow and Direct the Cat plus several two-year-olds, all aiming to make this year’s Breeders’ Classic night another banner night for Beau Ridge.

“With these two-year-olds, getting them ready, you got to let them tell you, you can't rush them too much. You got to let them tell you when they're ready to move on. You might think they're ready to work, and they might not even know what that means. So, you got to work with the horse a little bit and let them know what's going on,” she shared. She aims to give each horse three weeks between starts, though “sometimes you have to do it in two, depending on how the condition books fit you.”

With six stallions, including a life changer in Fiber Sonde and a promising successor in Redirect, standing at Beau Ridge, a band of broodmares that continue to produce runners, and a stable full of established winners like Overnight Pow Wow and up-and-coming two-year-olds, Cynthia McKee is “not ready to hang it up quite yet.” She carries on, running the show while giving her late husband his due credit for what they built together. This horsewoman, though, “just [does] it. I get up in the morning and I just go, and I do as much as I can that day. There are times that I'm glad I'm busy because there are things that happen that you just feel like going to bed, pulling the covers over your head, and crying. But I can't stop long enough to do that.”

“The main thing that kept me going is the horses, like Fiber Sonde. I couldn't put him somewhere. I couldn't do that. He built this farm. This is his home. He built this and [Holy] Pow Wow, and Ghost Canyon. They've given us everything, and now they got some age on them. What am I supposed to do? Boot them somewhere? I just kept thinking about that,” McKee reflected.

Instead, she keeps going, planning, and racing, proof that staying close to home, thanks to the support of programs like the West Virginia Thoroughbred Development Fund, can sustain the sport as much as deeper pockets and larger stables have. Beau Ridge and Cynthia McKee show that long-term sustainable success in the sport of horse racing takes many forms and benefits from investment at all levels, a reminder of the many ways that men and women across the country and around the world make their living caring for and competing with these equine athletes.

#Soundbites - What do you look for when you evaluate a yearling at sales, and are there sire lines that influence your opinions?

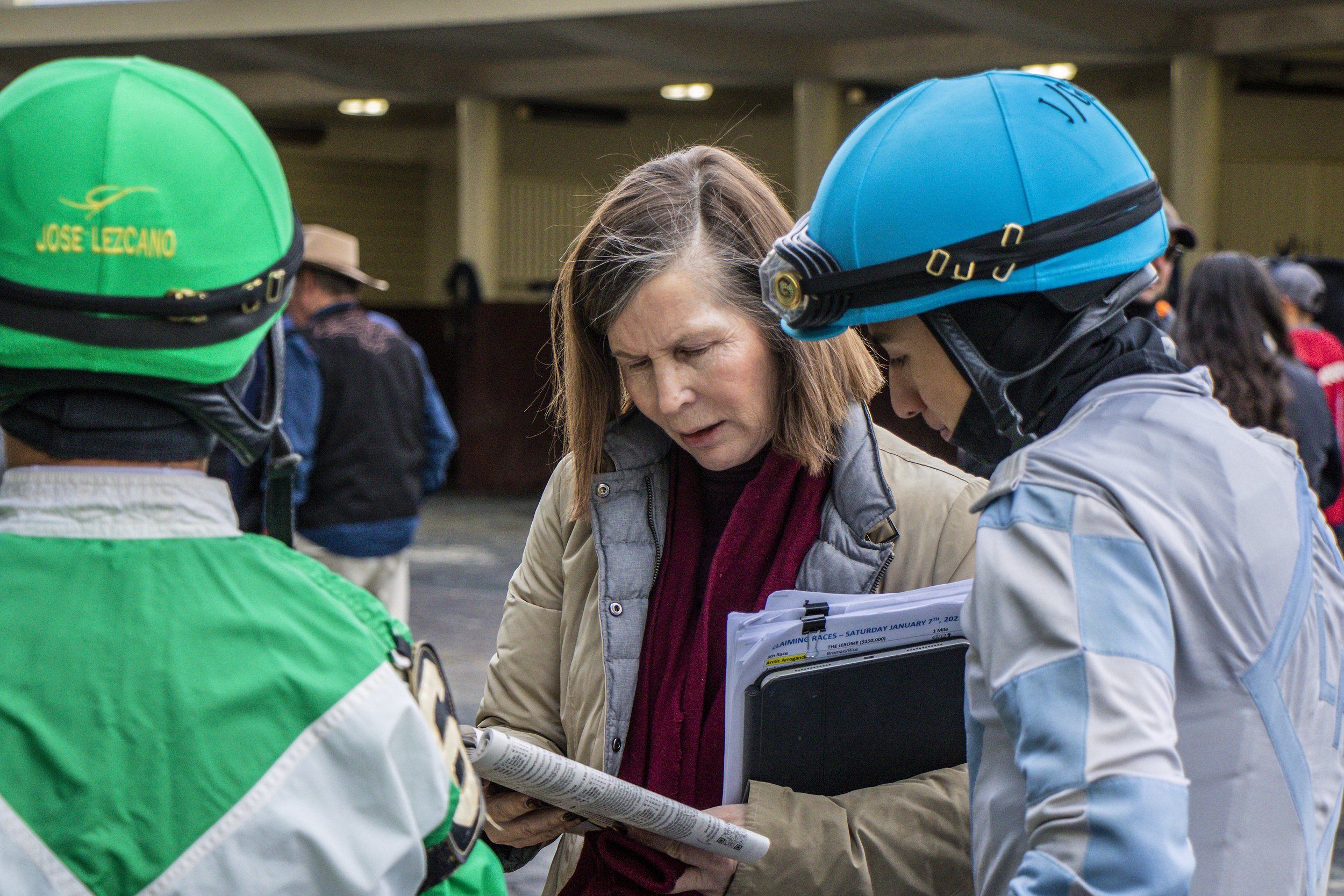

Linda Rice

Linda Rice

I look for a good shoulder, and usually that will transcend into a great walk, an athletic walk. I do that for the length of stride. I like to buy young mares. Of course I have preference for some stallions I have had success with like City Zip. And then stallions everybody likes: sons of Into Mischief, sons of Curlin, sons of McLain’s Music. I’ve done well with them. If they have a great shoulder and a great walk, I’ll take a shot on an unproven stallion.

Brad Cox

The first thing, from a physical standpoint, is you have to consider his size. Is he too big or too small? As far as sire lines, you’re looking for signs. You totally have to have an idea what the yearling will look like. Will he look like his sire? You pay attention.

Graham Motion

Graham Motion

I think many of us get influenced by stallions’ progeny that we have trained before. There are other ones that we avoid if we haven’t done well with a sire’s prodigy. I think the one thing I look for is athleticism in general. I’m not overly critical of conformation.

John Sadler

John Sadler

We’re looking primarily for dirt pedigrees for California. I have a good idea what works here, what doesn’t work here. Obviously, I’m partial to some of the sires I trained, Twirling Candy, Accelerate, and Catalina Cruiser who’s off to a very fast start. On the conformation side, I look for a well-conformed horse that looks like an athlete. As an experienced trainer, you look for any little things. You learn what you can live with or without. Then, obviously, I’m looking for Flightlines in a couple of years!

Simon Callaghan

Simon Callaghan

Generally, I’m looking for an athlete first and foremost. Conformation and temperament are two major factors. Yes, there are sire lines I like—not one specific one. Certainly it’s a relatively small group.

Tom Albertrani

Tom Albertrani

I’m not a big sales guy, but when I do go, I like to look at the pedigree first. Then I look for the same things as everyone else. Balance is important. I like to see a horse that’s well-balanced, and I like nicely muscle-toned hindquarters.

Michael Matz

One of the things, first of all, is I look at the overall picture and balance. We always pick apart their faults, then what things that are good for them. You look for the balance, then if they’re a young yearling or an older yearling. Those are some of the things I look at. If you like one, you go ahead. There are certain sires if you have had luck with them before. It all depends on what the yearling looks like. I would say the biggest things I look at are their balance and their attitude. When you see them come out and walk, sometimes I like to touch them around the ear to see how they react to that. That shows if they’re an accepting animal.

State Incentives 2023

Article by Annie Lambert

The bad news is, North American inflation has substantially increased expenses in Thoroughbred racing. The good news is, U.S. purses in 2022 were up nearly 11% from 2021. Also, states and farms are working to provide owners and breeders an opportunity to counter those growing costs with healthy incentive opportunities.

State Pluses

U.S. inflation rose to a shuttering 9.1% last year, but it has dropped to the current 6.5%. Canada’s most recent number was 6.8%. Both numbers, although improved, still leave horsemen pushing higher outlays across the board. Breeders, owners and trainers can help buffer inflated costs with readily available incentive programs.

Mary Ellen Locke, registrar and incentive program manager for the California Thoroughbred Breeders Association, cited there are no changes to that state’s programs for the current year. As one of the most successful state organizations, the CTBA has seldom tried to fix what is not broken.

“I think [our program] has helped sustain our numbers through Covid and the economy being down,” Locke pointed out. “The numbers of Thoroughbred foals are down all over, but we are holding our own in California.”

The association’s definition of a Cal-bred is one thing helping California retain those foal numbers. Cal-breds are those foals dropped in the state after being conceived there by a California stallion. Or, “any Thoroughbred foal dropped by a mare in California if the mare remains in California to be next bred to a Thoroughbred stallion standing in the state” will be classified as Cal-bred. If the mare cannot be bred for two consecutive seasons, but remains in California during that period, her foal will still be considered a Cal-bred.

The Pennsylvania Horse Breeders Association is offering a new race series for two-year-olds in 2023, according to Brian Sanfratello, the group’s executive secretary. The Pennsylvania-bred series offers three stakes for fillies and three for colts.

“The first two races will feature purses of $100,000 to be run during Pennsylvania Day at the Races at Parx Racing,” Sanfratello offered. “The second set will have purses of $150,000 and will also be held at Parx the day of the Pennsylvania Derby; and the third in the series will feature $200,000 purses at a track to be determined.”

Trainers of the top three earning horses will be rewarded with bonuses of $25,000, $15,000 and $10,000.

In addition, Penn National has increased their owner bonus to 30%. The racetracks in that state pay for owner bonuses.

Virginia has been on a roll since passing their historical horse racing legislation in 2019. Last year, according to Debbie Easter, executive director of the Virginia Thoroughbred Association (VTA), Colonial Downs averaged $612,000 in daily purse monies.

The Virginia Racing Commission approved an additional nine days of racing for the current year. Colonial Downs, the only live racing venue in the state, will run Thursday through Saturday from July 13 to September 9.

“Thanks to Historic Horse Racing (HHR) machines in Virginia, breeding, raising and racing Thoroughbreds has never been better,” according to Easter. “In 2023, the Virginia Breeders fund should double to over $2 million thanks to funds received from HHR.

Virginia breeders currently earn bonuses when Virginia-bred horses win a race anywhere in North America. If pending legislation passes the Virginia General Assembly, breeders will have an update for 2023. They will earn awards for horses placing first through third in North America.

“Because of budget constraints that limit the Virginia-Certified program to $4 million in both 2023 and 2024, we have made changes to our very successful program that pays 25% bonuses to the developers of Virginia-Certified horses that win at Mid-Atlantic region racetracks, which includes New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and West Virginia in addition to Virginia,” Easter added. “The plan is to increase funding for the program once Colonial Downs adds more HHR locations and machines, hopefully in 2024 and 2025.”

Iowa and New Mexico may not produce the largest annual foal crops in North America, but they each had Breeders’ Cup contenders last year.

Tyler’s Tribe (Sharp Azteca) headed to Keeneland undefeated in five starts in his home state of Iowa to contest the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint (G1). Unfortunately, the then two-year-old gelding was eased into the stretch after bleeding. He did regroup to finish third at Oaklawn Park just a month later in the Advent Stakes.

After challenging the inside speed during the Breeders’ Cup Filly and Mare Sprint (G1), New Mexico-bred Slammed (Marking) finished out of the money. Although the now five-year-old mare has not run since, her previous earnings of $557,030 (13 starts, 9-1-0) give her credibility as a broodmare prospect.

With the majority of Breeders’ Cup contenders raised on Kentucky bluegrass, mare owners may want to start watching for options in Iowa and New Mexico.

Bonus Bucks

Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners launched in the fall of 2011. Their ability to acquire, manage and develop runners and put together partnerships is quantified by their gross earnings of $42,561,789.

Eclipse President, Aron Wellman, sees the value of state-bred incentives and makes use of them, although his first order of business is finding the right horses.

“We are going to buy a horse because we like the horse,” Wellman confirmed. “If we buy something eligible for regional programs, we take advantage of them.”

The group’s Chief Financial Officer, Bill Victor, notices incentive earnings on his bottom line. “Breeder incentive programs are important to any stable.”

Spendthrift Farm continues to enjoy their fruitful and much copied programs. This year, Safe Bet will feature Coal Front (Stay Thirsty) standing at $5,000. If Coal Front does not produce at least one graded or group stakes winner by December 31, from his first two-year-old crop the mare owner will owe no stud fee. If he produces a stakes winner, the normal fee will be owed.

Share the Upside features Greatest Honour (Tapit) for 2023. The breeder sends a mare to this stallion, has a live foal and pays the $10,000 fee. That foal entitles the mare owner to a lifetime breeding to Greatest Honour, an annual breeding share, with no added costs. Greatest Honour is, however, sold out for this year.

Both these Spendthrift programs minimize risks and offer great value, especially to smaller breeders.

Canada continues its successful Ontario Thoroughbred Improvement Program (TIP) with a current budget of $800,000.

The province’s Mare Purchase Program (MPP) provides breeder incentives to invest in and ship mare power into Ontario. Foal mares—purchased for a minimum of $10,000 (USD), with no maximum price, at a recognized auction outside of Ontario, but produce 2023 foals in the providence— are eligible for a rebate. The rebate is for 50% of the purchase price up to $25,000 (CAD) with a limit of $75,000 (CAD) per ownership group. Mares bred back to a registered Ontario Sire in the 2023 breeding season are also eligible for a $2,500 (CAD) bonus.

The Mare Recruitment Program (MRP) incentivizes mare owners who bring an in-foal mare to Ontario to foal in 2024. Owners will receive a $5,000 (CAD) incentive for each in-foal mare brought to Ontario. The mare must not have foaled in Ontario in 2022 or 2023. MRP is for mares purchased at an Ontario Racing accredited sale in 2023 and must have a minimum purchase price of $5,000 (USD).

Breeders of record are eligible for additional bonuses through TIP. Specific details on the MPP and MRP programs criteria are outlined in the applicable criteria book.

The Struggle Is Real

Minnesota’s only Thoroughbred racetrack suffered a low blow recently when their 10-year marketing agreement with the nearby Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux community expired without renewal. The track will be racing fewer days this year to keep purse amounts competitive without the additional funds.

The former agreement forbad Canterbury from supporting additional gaming legislation in the state; they are now free to push for sports wagering and slots of historical horse racing machines.

Canterbury Park’s Thoroughbred 2023 stakes schedule will feature twenty-four races totaling $1.65 million in purses.

Texas Thoroughbred has one of the most innovative breed associations in the United States, especially for a state that has suffered setbacks over the decades. Their plan to promote Texas racing through public relations was a great success last year and will continue through this year.

“A series of events are conducted at Sam Houston Race Park, Lone Star Park and in connection with the Texas Two-Year-Old in Training Sale and the Texas Summer Yearling Sale,” said Texas Thoroughbred Association Executive Director Mary Ruyle. “Last year, this initiative resulted in forty-two new, first-time Texas Thoroughbred racehorse owners, equating to slightly more than $300,000 through participation in the Texas Thoroughbred Racing Club and private purchase connections set-ups.”

Due to Texas’ stance on the Horseracing and Integrity Act (HISA), the Texas Racing Commission does not send out their racing signal unless it is out of the United States. When HISA was enacted July 1, 2022, they only had 14 days of the meet remaining. This year it has hindered their purse structure and the Accredited Thoroughbred Awards, according to Ruyle.

To resolve the problem, they have begun running races earlier in the day, rather than in the evenings, to draw more spectators and handle. They also made a deal with Woodbine to export their signal to Canada.

“At this moment, the purses are essentially the same,” Ruyle said. “As we get into the meet, we’ll see if we are able to sustain that.”

All Thoroughbred racing states within the United States, along with provinces in Canada, have some deals to incentivize breeders. Researching states of interest can provide the means to fend off these inflationary times in North America.

Ontario Breeding

By Alex Campbell

The Ontario breeding industry has experienced a number of twists and turns since the provincial government canceled the lucrative slots-at-racetracks program back in 2013. Prior to the cancelation of the program, the once robust industry had years where more than 1,600 mares were bred in the province, according to numbers published by The Jockey Club. In 2018, that number was down to 733.

While the cancelation of the program has impacted the majority of the province’s breeders, well-known breeding operations in Ontario have experienced success through all of the uncertainty. Sam-Son Farm won back-to-back Sovereign Awards as Canada’s top breeder in 2013 and 2014, while Frank Stronach’s Adena Springs won three straight Sovereign Awards between 2015 and 2017 when they bred two Queen’s Plate winners in that time, including Shaman Ghost in 2015 and Holy Helena in 2017.

Along with these big operations, several other commercial breeders are also experiencing success, not only in Ontario but throughout North America and internationally as well. Ivan Dalos’ Tall Oaks Farm bred two Gr1 winners in 2018, including full brothers Channel Maker, who won the Joe Hirsch Turf Classic at Belmont Park, and Johnny Bear, who won the Gr1 Northern Dancer Turf Stakes at Woodbine for the second consecutive year. In addition, Dalos also bred Avie’s Flatter, Canada’s champion two-year-old in 2018; dam In Return, who produced Channel Maker; and Johnny Bear, which was Canada’s Outstanding Broodmare. As a result, Tall Oaks Farm won its first Sovereign Award for Outstanding Breeder in 2018 as well.

Horses bred by David Anderson’s Anderson Farms and Sean and Dorothy Fitzhenry also were big winners at last year’s Sovereign Awards. Anderson bred Queen’s Plate winner and 2018 Canadian Horse of the Year, Wonder Gadot, while Fitzhenry’s homebred, Mr Havercamp, was named champion older male and champion male turf horse. Both Anderson and Fitzhenry have also had success selling horses internationally, primarily at Keeneland. In 2017, Anderson sold Ontario-bred yearling, Sergei Prokofiev—a son of Scat Daddy—to Coolmore for $1.1 million. One of Fitzhenry’s success stories is that of Marketing Mix, who he sold for $150,000 to Glen Hill Farm at the 2009 Keeneland September Yearling Sale. Marketing Mix went on to win the Wonder Where Stakes at Woodbine as a three-year-old in 2011, and captured two Gr1 victories later on in her career in the 2012 Rodeo Drive Stakes at Santa Anita and the 2013 Gamely Stakes at Hollywood Park.

For Anderson, commercial breeding is all he’s ever known. The son of the late Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame inductee, Robert Anderson, David Anderson grew up around horses at his father’s farm in St. Thomas, Ontario. In the 1970s and 1980s, Anderson Farms was one of the biggest breeders and consignors in the province, breeding several graded stakes winners. In fact, in 1985, Anderson Farms was the leading consignor at both the Saratoga and Keeneland yearling sales.

“That’s what my father established years ago, and that’s what I grew up with was breeding and selling at all of the international sales,” David Anderson said. “We haven’t diverted from that philosophy in nearly 50 years. It’s what I learned growing up, and I try to buy the best quality mares that I can and breed to the best quality sires that I can.”

David Anderson (blue suit) with Peter Berringer

While Anderson closely watched his father build up the Thoroughbred side of the business, he got experience of his own breeding Standardbreds. After all, the farm’s location in Southwestern Ontario is in the heart of Standardbred racing in the province. Anderson said the Standardbred business had a number of success stories spanning more than a decade: breeding champions such as Pampered Princess, Southwind Allaire, Cabrini Hanover, and The Pres.

In 2010, Robert Anderson passed away from a heart attack, and the farm was taken over by David Anderson and his sister, Jessica Buckley, who is the current president of Woodbine Mohawk Park. Anderson went on to buy Buckley out of her share of the farm and took on full control. He also decided he wanted to focus exclusively on Thoroughbred breeding and racing.

“After my Dad died I decided I wanted to jump back into the Thoroughbreds,” he said. “I sold all the Standardbreds and put everything I had back into Thoroughbreds. I came full circle back to my roots, and this is where I really love it.”

It’s been a long-term project for Anderson to get the farm to where it is today. After taking control of the farm, Anderson sold off all of his father’s mares—with the exception of one—and began to build the business back up. Anderson said his broodmare band currently sits between 25 and 30, which is where he wants to keep it.

Fitzhenry, on the other hand, took a much different path to his current standing in the Thoroughbred breeding industry. Fitzhenry said his start in Thoroughbred racing came through a horse owned by friends Debbie and Dennis Brown. Fitzhenry and his wife, Dorothy, would follow the Brown’s horse, No Comprende, who won seven of his 30 starts in his career, including the Gr3 Woodbine Slots Cup Handicap in 2003.

The Fitzhenrys decided they wanted to get involved in ownership themselves and partnered with the Browns on a couple of horses. The more Fitzhenry got involved, the more the breeding industry appealed to him.

TO READ MORE - BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 54 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 54 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.9

Pedigree vs Conformation

By Judy Wardrope

What are the factors people consider when assessing a potential racehorse? In part, it depends on their intentions. Different choices may be made if the horse or offspring is intended for their own use or how the horse or offspring might sell.

And when a horse gets to the track, what factors help a trainer decide on a particular distance or surface to try? Most of the trainers I interviewed say that they usually look at who the sire is when trying to determine distance and/or surface preferences.

Trainer Mark Frostad said, “I look at the pedigree more than the individual regarding distance and surface.”

Richard Mandella says that his determining factors are “conformation, style of action, pedigree and the old standby, trial and error.”

Roger Attfield says, “It is extremely hard to tell turf versus dirt. I’ve watched horses all my life and I’ve tried to figure it out. I can tell when I start breezing them. I had a half-sister [to Perfect Soul], who was stakes-placed, and she couldn’t handle the turf one iota. I had the full brother…also turf. Approval could win on the dirt, but as soon as he stepped on the turf, he was dynamite.”

What about when planning a potential breeding for a mare or a stallion? Is conformation more important than pedigree? Or does pedigree have more influence than conformation? How much of a role does marketing play in the selections?

Although ancestry and conformation do go together, the correlation is complicated. For example, top basketball players tend not to come from families of short people, but most NBA stars do not have siblings who are star players. The rule holds for other athletes, including gymnasts. But what would you get if you crossed a basketball player with a gymnast?

Pedigree is not an absolute despite what marketing campaigns may lead you to believe. Look at human families—maybe even your own. Are you built like all of your siblings, do you all have the same talents? And what about your cousins? Are you all built alike and of equal talent?

When it comes to Thoroughbred horses, you will find that only the very top sires boast a percentage of stakes winners nearing 15%. If one assumes that a stakes winner is the goal of most breeders, then that would indicate at least an 85% failure rate.

When breeding horses or selecting potential racehorses, the cross might look good on paper or in our imaginations, but what are the odds that the offspring would be able to perform to expectations if it was not built to be a success at the track? Looking at the big picture, one has to wonder what we are doing to the gene pool if we only breed for marketability.

To get a better understanding, let’s look at four horses. Three of our sample horses have strong catalog pages, but did they run according to their pedigrees or according to the mechanics of their construction? Furthermore, did the horse with the humdrum catalog page have a humdrum racing career?

Ocean Colors

PEDIGREE

She is by Orientate, a campion sprinter of $1,716,950 (including a win in the Breeders' Cup Sprint [Gr1], who sired numerous stakes horses and was the broodmare sire of champions.

Her dam, Winning Colors, earned $1,526,837, was the champion three-year-old filly and beat the boys in the Kentucky Derby [Gr1] and the Santa Anita Derby [Gr1]. She was a proven classic-distance racehorse.

Winning Colors was the dam of 10 registered foals, 9 to race, 6 winners, including Ocean Colors and Golden Colors (a stakes-placed winner in Japan, who produced Cheerful Smile, a stakes winner of $1,878,158 in North America), and she is ancestor to other black-type runners.

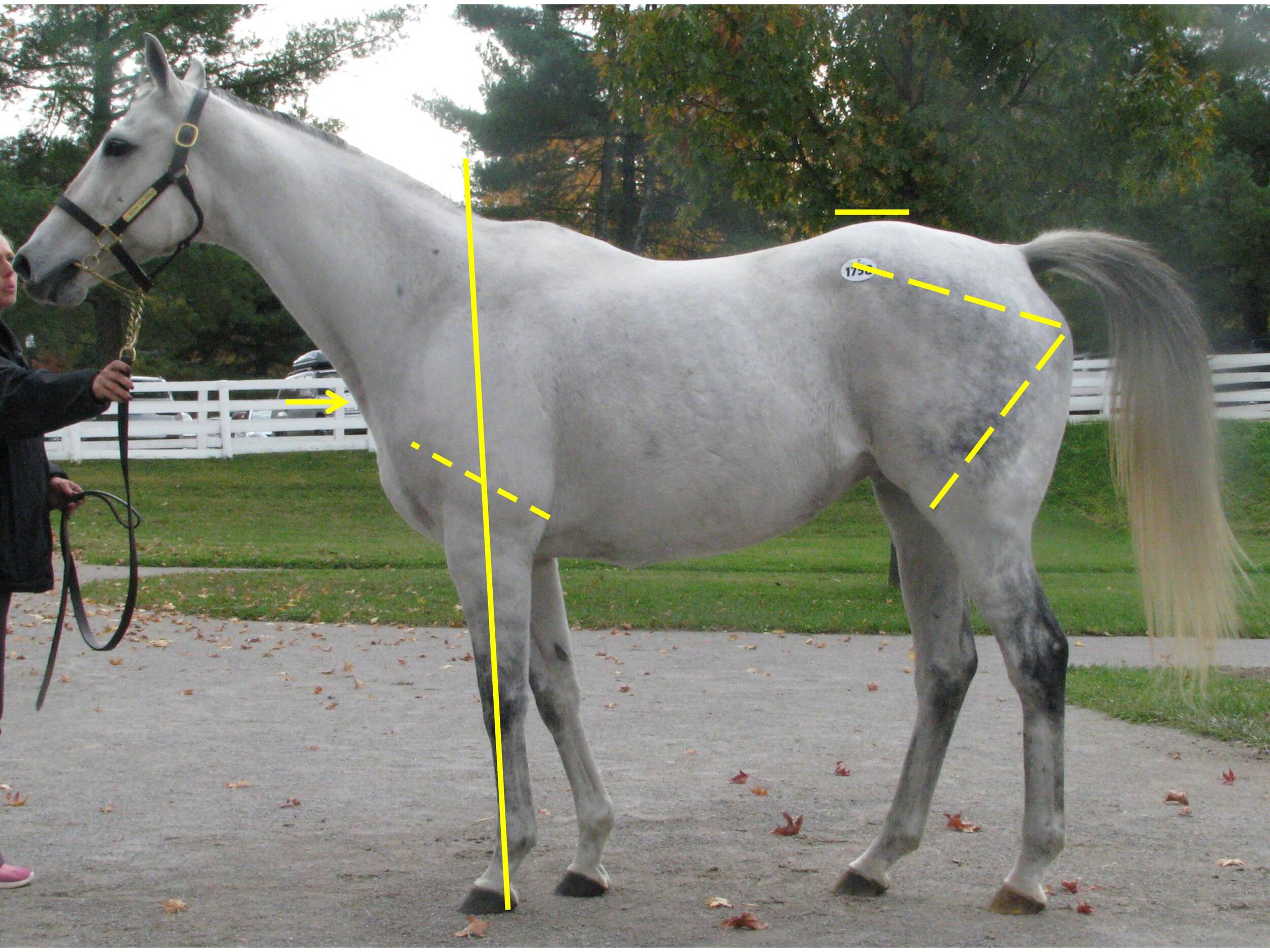

CONFORMATION

Her lumbosacral gap (LS), which is just in front of the high point of croup and functions like the horse's transmission, is considerably rearward of ideal. This constitutes a significant difference when compared to either of her athletic parents.

The rear triangle is equal on the ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock) and femur side (point of buttock to stifle protrusion), and her stifle is well below where the bottom of the sheath would be if she were male. In essence these would contribute to the long, ground-covering stride seen in distance horses like her dam.

Her pillar of support (a line extending through the natural groove in her forearm) emerges well in front of her withers for some lightness to the forehand and into the rear quarter of the hoof for added soundness.

Her base of neck is neither high nor low when compared to her point of shoulder, meaning that placement neither added nor subtracted weight on the forehand.

Because her humerus (elbow to point of shoulder) is not as long as one would expect for a range of motion that would match that of her hindquarters, she likely resembles her sprinter lines in this area. Although I never saw her race, I strongly suspect that her gait was not smooth. In order to compensate for a shorter stride in the front than in the back, she probably wanted to suspend the forehand while her hindquarters went through the full range of motion. Unfortunately, she is not strong enough in the LS to effectively use that method of compensating.

RECORDS

Her race record shows her as a stakes-placed mare and winner of $127,093 but closer examination shows that the stakes race was not graded with a small purse and that her three wins, two seconds and three thirds were not in top company.

While valuable on paper as a broodmare, and despite being mated to some top stallions early in her breeding career, she failed to produce a quality racehorse. Naturally her value dropped significantly until she sold in November 2018 for $20,000 in foal to Anchor Down.

Sequoyah

PEDIGREE

His sire, A.P. Indy earned $2,979,815, won the Breeders’ Cup Classic and the Belmont Stakes plus was the Eclipse Champion three-year-old and Horse of the Year. He was also a top sire of stakes horses as well as a noted sire of sires.

His dam, Chilukki, earned more than $1.2 million, was the Eclipse Champion two-year-old filly, was second in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies, and set track records at Churchill Downs for both 4.5 furlongs and a mile. Her sire won the Breeders’ Cup Sprint and equaled a track record for 7 furlongs.

CONFORMATION

His LS is 1.5” (by actual palpation) rearward of ideal and just at the outer limits of the athletic range.

His rear triangle is slightly shorter on the femur side (point of hip to stifle protrusion), which not only decreases the range of motion of the rear leg by changing the stride’s ellipse, but it adds stress to the hind leg from hock down.

The stifle placement (well below sheath level) would indicate a preference for distances around 10 furlongs (similar to his sire’s), except for the short femur.

His pillar of support does emerge in front of the withers, but the bottom of the line emerges behind the heel, making him susceptible to injury to the suspensory apparatus of the foreleg (tendons and ligaments).

His humerus is of medium length and is moderately angled and would represent a range of motion that would match the hindquarters. However, the tightness of his elbow (note the circled muscling over the elbow) would likely prevent him from using the full range of motion. He would stop the motion before the elbow contacted his ribs; thus, the development of that particular muscle as a brake and a reduction in stride length. His base of neck was well above point of shoulder, which adds some lightness to his forehand.

RECORDS

He was injured in his only start and had zero earnings. He did go to stud based on his pedigree, but was not a success. He sired one stakes winner of note, a gelding out of a stakes-winning Smart Strike daughter, who won at distances from 7 to 9 furlongs.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (PRINT)

$6.95

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PRINT & ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION

$24.95

Top 20 Pennsylvania Breeders of 2017

By Linda Dougherty

It was a record-setting year for Glenn E. Brok, who in 2017 collected the most Pennsylvania Breeding Fund awards in the program’s history.

Brok, who owns Diamond B Farm in Mohrsville with his wife Becky, saw his homebreds earn $374,651, while he garnered stallion awards of $75,191, for a total of $449,842. The top homebred for Brok was The Man, a son of Ecclesiastic, who formerly stood at Diamond B. He captured the Banjo Picker Sprint Stakes for Pennsylvania-breds at Parx Racing, as well as five consecutive allowance races for a perfect six-for-six season.

“The Pennsylvania breeding program has been really great for us,” Brok said. “And our program is stronger and better than other states.”

* Donald L. Brown Jr. was the second-leading breeder in Pennsylvania in 2017, with his combined breeder and stallion awards totaling $326,862. His top three award winners were all sired by the stallion Messner, who stood at Penn Ridge Farms in Harrisburg before being exported. These were Ruby Bleu ($42,127), Wildcat Cartridge ($42,806) and Wildcat Combat ($41,794).

“The Pennsylvania breeder awards give you the best opportunity to recover and possibly profit from the expenses of raising a horse,” said Brown. “Further, the awards are great for Pennsylvania agriculture! I would rather see a farm and green grass than a parking lot or strip mall.”

* It was sheer sire power for Northview-PA, as the Peach Bottom nursery owned by Richard Golden earned $321,053 in stallion awards. Dominating the Pennsylvania sire list in terms of stallion awards earned was Jump Start, whose progeny garnered $207,984. Other stallions who stand or stood at the farm were Fairbanks ($54,988), Medallist ($28,836), Love of Money ($21,298), El Padrino ($7,352), and Bullsbay ($366). Jump Start was the top sire in the Mid-Atlantic region in 2017, with total progeny earnings of more than $5.4 million. His top Pennsylvania-bred during the year was Late Breaking News, who earned more than $47,000 in awards for his breeder, Stacy McMullin Machiz.

* Thanks to a pair of stakes-winning half-sisters, the Barlar LLC stable of owner/breeder Larry Karp was the fourth-leading recipient of breeders awards in 2017. Karp’s homebreds earned $214,866 while he earned $58,431 in stallion awards from the progeny of E Dubai, for a total of $273,297. Imply, a daughter of E Dubai out of Allude, by Orientate, captured the Northern Fling Stakes at Presque Isle Downs, accruing $161,000 in breeder awards. Her younger half-sister Advert, by Lonhro, won the Malvern Rose Stakes at Presque Isle, earning $92,624 in breeder awards.