The value of good hoof balance and how to evaluate this alongside your farrier

Article by Adam Jackson MRCVS

Introduction

The equine foot is a unique structure and a remarkable feat of natural engineering that follows the laws of biomechanics in order to efficiently and effectively disperse concussional forces that occur during the locomotion of the horse. Hoof balance has been a term used by veterinarians and farriers to describe the ideal conformation, size and shape of the hoof relative to the limb.

Before horses were domesticated, they evolved and adapted to survive without any human intervention. With respect to their hoof maintenance, excess hoof growth was worn away due to the varied terrain in their habitat. No trimming and shoeing were required as the hoof was kept at a healthy length.

With the domestication of the horse and our continued breeding to achieve satisfactory performance and temperament, the need to manage the horse’s hoof became essential in order to ensure soundness and performance. The horse’s foot has evolved to ensure the health and soundness of the horse; therefore, every structure of the foot has an essential role and purpose. A strong working knowledge of the biology and biomechanics of the horse’s foot is essential for the veterinarian and farrier to implement appropriate farriery. It was soon concluded that a well-balanced foot, which entails symmetry in shape and size, is essential to achieve a sound and healthy horse.

Anatomy and function of the foot

The equine foot is extremely complex and consists of many parts that work simultaneously allowing the horse to be sound and cope with the various terrains and disciplines. Considering the size and weight of the horse relative to the size of the hoof, it is remarkable what nature has engineered. Being a small structure, the hooves can support so much weight and endure a great deal of force. At walk, the horse places ½ of its body weight through its limbs and 2 ½ its weight when galloping. The structure of the equine foot provides protection, weight bearing, traction, and concussional absorption. Well-balanced feet efficiently and effectively use all of the structures of the foot to disperse the forces of locomotion. In order to keep those feet healthy for a sound horse, understanding the anatomy is paramount.

The foot consists of the distal end of the second phalanx (short pastern), the distal phalanx (pedal bone, coffin bone) and the navicular bone. The distal interphalangeal joint (coffin joint) is found between the pedal and short pastern bone and includes the navicular bone with the deep digital flexor tendon supporting this joint. This coffin joint is the center of articulation over which the entire limb rotates. The navicular bone and bursa sits behind the coffin bone and is stabilized by multiple small ligaments. The navicular bone allows the deep digital flexor tendon to run smoothly and change direction in order to insert into the coffin bone. The navicular bursa is a fluid-filled sac that sits between the navicular bone and the deep digital flexor tendon.

The hoof complex can be divided into the epidermal weight-bearing structures that include the sole, frog, heel, bulbs, bars, and hoof wall and the anti-concussive structures that include the digital cushion, lamina, deep digital flexor tendons, and ungual (lateral) cartilage. The hoof wall encloses the dermal structures with its thickest part at the toe that decreases in thickness as it approaches the heel. The hoof wall is composed of viscoelastic material that allows it to deform and return its shape in order to absorb concussional forces of movement. There is enough deformation to diminish the force from the impact and load of the foot while preventing any damage to the internal structures of the foot and limb. As load is placed on the foot, there is deformation that consists of:

Expansion of the heels

Sinking of the heels

Inward movement of the dorsal wall

Biaxial compression of the dorsal wall

Depression of the coronary band

Flattening of the sole

The hoof wall, bars and their association with the sole form the heel base with the purposes of providing traction, bearing the horse’s weight while allowing the stability and flexibility for the expansion of the hoof capsule that dissipates concussional forces on foot fall. The sole is a highly keratinized structure like the hoof wall but made up of nearly 33% water so it is softer than the hoof wall and should be concave to allow the flattening of the sole on load application. The frog and heel bulbs serve a variety of special functions ranging from traction, protection, coordination, proprioception, shock absorption and the circulation of blood.

When the foot lands on the ground, the elastic, blood-filled frog helps disperse some of the force away from the bones and joints, thus, acting as a shock absorber. The venous plexus above the frog is involved in pumping blood from the foot back to the heart when the foot is loaded. In addition, there is shielding of the deep digital flexor tendon and the sensitive digital cushion (soft tissue beneath the sole that separates the frog and the heel bulb from the underlying tendons and bones). Like the heel bulbs, the frog has many sensory nerve endings allowing the horse to be aware of where his body and feet are and allows the horse to alter landing according to the condition of the ground (proprioception and coordination).

The soft tissue structures comprise and form the palmar/plantar aspect of the foot. The digital cushion lies between the lateral cartilages and above the frog and bars of the horse’s hoof. This structure is composed of collagen, fibrocartilage, adipose tissue and elastic fiber bundles. The digital cushion plays a role in shock absorption when the foot is loaded as well as a blood pumping mechanism. Interestingly, it has been found that the digital cushion composition varies across and within breeds. It is thought the variation of the composition of the digital cushion is partially dictated by a genetic predisposition. In addition, the composition of the digital cushion changes with age. As the horse ages the composition alters from elastic, fat and isolated collagen bundles to a stronger fibrocartilage. Finally, the digital cushion and connective tissue within the foot have the ability to adapt to various external stimuli such as ground contact or body weight. The lateral cartilage is a flexible sheet of fibrocartilage that suspends the pedal bone as well as acting as a spring to store and release energy. The lamina is a highly critical structure for hoof health. The lamina lies between the hoof wall and the coffin bone. There are two types of lamina known as the sensitive (dermal) lamina and insensitive (epidermal) lamina. The insensitive lamina coming in from the hoof wall connects to the sensitive lamina layer that is attached to the coffin bone and these two types of lamina interdigitate with each other to form a bond.

Hoof and Musculoskeletal System

The hoof and the musculoskeletal system are closely linked and this is particularly observed in the posture of the horse when resting or moving. Hoof shape and size and whether they are balanced directly affects the posture of the horse. Ultimately, this posture will also affect the loads placed on the skeletal system, which affects bone remodeling. With an imbalance, bone pathologies of the limbs, spine and pelvis may occur such as osteoarthritis. In addition, foot imbalances result in postural changes that lead to stress to the soft tissue structures that may lead to muscle injuries and/or tendon/ligament injuries.

Conformation and hoof balance

The terms balance and conformation are used frequently and used to describe the shape and size of the limb as a whole as well as the individual components of the limb and the spatial relations between them. Balance is the term often used to describe the foot and can be viewed as a subset of conformation.

Conformation should be considered when describing the static relations within the limb and excludes the foot. Balance should be considered when describing the dynamic and static relationship between the horse’s foot and the ground and limb as well as within the hoof itself.

These distinctions between conformation and balance are important to assess lameness and performance of the horse. Additionally, this allows the veterinarian and farrier to find optimal balance for any given conformation.

The term hoof balance does lack an intrinsic definition. The use of certain principles in order to define hoof balance, which in turn can be extended to have consistent evaluation of hoof balance as well as guide the trimming and shoeing regimens for each individual horse. In addition, these principles can be used to improve hoof capsule distortion, modify hoof conformation and alter landing patterns of the foot. These principles are:

Evaluate hoof-pastern axis

Evaluate center of articulation

The need for the heels to extend to the base of the frog

Assessing the horse’s foot balance by observing both static (geometric) balance and dynamic balance is vital. Static balance is the balance of the foot as it sits on a level, clean, hard surface. Dynamic balance is assessing the foot balance as the foot is in motion. However, horses normally do not resemble the textbook examples of perfect conformation, which creates challenges for the farriers and veterinary surgeons. The veterinarian should instigate further evaluation of the foot balance and any other ailments, in order to provide information that can be used by the farrier and veterinarian in formulating a strategy to help with the horse’s foot balance. With the farrier and veterinarian working cooperatively, the assessment of the hoof balance and shoeing of the foot should deliver a harmonious relationship between the horse’s limb, the hoof and the shoe.

Dynamic Balance

The horse should be assessed in motion as one can observe the foot landing and placement. A balanced foot when in motion should land symmetrically and flat when moving on a flat surface. When viewed from the side, the heels and toe should land concurrently (flat foot landing) or even a slight heel first landing. It is undesirable to have the toe landing first and often suggests pain localized to the heel region of the foot. When observing the horse from the front and behind, both heel bulbs should land at the same time. Sometimes, horses will land first slightly on the outside or lateral heel bulb of the foot but rarely will a horse land normally on the medial (inside) of the foot. If the horse has no conformational abnormalities or pathologies the static balance will achieve the dynamic balance.

Static Balance

Hoof –pastern axis (HPA)

The hoof pastern axis (HPA) is a helpful guideline in assessing foot balance. With the horse standing square on a hard, level surface, a line drawn through the pastern and hoof should be parallel to the dorsal hoof wall and should be straight (unbroken). The heel and toe angle should be within 5 degrees of each other. An underrun heel has been defined as the angle of the heel being 5 degrees less than the toe angle. The heel wall length should be roughly 1/3 of the dorsal wall. In addition, the cannon (metacarpus/metatarsus) bone is perpendicular to the ground and when observed from the lateral side, the HPA should be a straight line. When assessing the foot from the side, the dorsal hoof wall should be aligned with the pastern. The optimal angle of the dorsal hoof wall is often cited as being 50-54°. The length of the dorsal hoof wall is variable but guidelines have been suggested according to the weight of the horse.

It is not uncommon that the hind feet are more upright compared to the fore feet at approximately 5 degrees. A broken hoof-pastern axis is the most common hoof imbalance. There are two presentations of a broken HPA known as a broken-back HPA and a broken-forward HPA. These changes in HPA are often associated with two common hoof capsule distortions that include low or underrun heels and the upright or clubfoot, respectively.

A broken-back hoof-pastern axis occurs when the angle of the dorsal hoof wall is lower than the angle of the dorsal pastern. This presentation is commonly caused by low or underrun heel foot conformation accompanied with a long toe. This foot imbalance is common and often thought to be normal with one study finding it present in 52% of the horse population. With a low hoof angle, there is an extension of the coffin and pastern joints resulting in a delayed breakover and the heels bearing more of the horse's weight, which ultimately leads to excess stress in the deep digital flexor tendon as well as the structures around the navicular region including the bone itself.

This leads to caudal foot pain so the horse lands toe first causing subsolar bruising. In addition, this foot imbalance can contribute to chronic heel pain (bruising), quarter and heel cracks, coffin joint inflammation and caudal foot pain (navicular syndrome). The cause of underrun heels is multifactorial with a possibility of a genetic predisposition where they may have or may acquire the same foot conformation as the parents. There are also environmental factors such as excessive dryness or moisture that may lead to the imbalance.

A broken-forward hoof-pastern axis occurs at a high hoof angle with the angle of the dorsal hoof wall being higher than the dorsal pastern angle. One can distinguish between a broken-forward HPA and a clubfoot with the use of radiographs. With this foot imbalance, the heels grow long, which causes the bypassing of the soft tissue structures in the palmar/plantar area of the foot and leads to greater concussional forces on the bone. This foot imbalance promotes the landing of the toe first and leads to coffin joint flexion as well as increases heel pressure. The resulting pathologies that may occur are solar bruising, increased strain of the suspensory ligaments near the navicular bone and coffin joint inflammation.

Center of articulation

When the limb is viewed laterally, the center of articulation is determined with a vertical line drawn from the center of the lateral condyle of the short pastern to the ground. This line should bisect the middle of the foot at the widest part of the foot and demonstrates the center of articulation of the coffin joint. The widest part of the foot (colloquially known as “Ducketts Bridge”) is the one point on the sole that remains constant despite the shape and size of the foot. The distance and force on either side of the line drawn through the widest part of the foot should be equal, which provides biomechanical efficiency.

Heels extending to the base of the frog

With respect to hoof balance, another component of the foot to assess is that the heels of the hoof capsule extend to the base of the frog. The hoof capsule consists of the pedal bone occupying two-thirds of the space and one-third of the space is soft tissue structures. This area is involved in dissipating the concussional and loading forces and in order to ensure biomechanical efficiency both the bone and soft-tissue structures need to be enclosed in the hoof capsule in the same plane.

To achieve this goal the hoof wall at the heels must extend to the base of the frog. If the heels are allowed to migrate toward the center of the foot or left too long then the function of the soft tissue structures have been transferred to the bones, which is undesirable. If there is a limited amount to trim in the heels or a small amount of soft tissue mass is present in the palmar foot then some form of farriery is needed to extend the base of the frog (such as an extension of the branch of a shoe).

Medio-lateral or latero-medial balance

The medio-lateral balance is assessed by viewing the foot from the front and behind as well as from above with the foot raised. To determine if the foot has medio-lateral balance, the hoof should be bisected or a line is drawn down the middle of the pastern down to the point of the toe.

You should be able to visualize the same amount of hoof on both the left and right of that midline. In addition, one should observe the same angle to the side of the hoof wall. It is important to pick up the foot and look at the bottom. Draw a line from the middle quarter (widest part of foot) on one side to the other then draw a line from the middle of the toe to the middle sulcus of the frog.

This provides four quadrants with all quadrants being relatively the same in size (Proportions between 40/60 to 60/40 have been described as acceptable for the barefoot and are dependent on the hoof slope). The frog width should be 50-60% of its length with a wide and shallow central sulcus. The frog should be thick enough to be a part of the bearing surface of the foot. The bars should be straight and not fold to the mid frog. The sole should be concave and the intersection point of both lines should be the area of optimal biomechanical efficiency.

The less concavity means the bone is nearer to the ground, thus, bearing greater concussional force. Finally, assess the lateral and medial heel length. Look down at the heel to determine the balance in the length of both heel bulbs. Each heel bulb should be the same size and height. If there are any irregularities with the heel bulbs then sheared heels may result, which is a painful condition. Medio-lateral foot imbalance results in the uneven loading of the foot that leads to an accumulation of damage to the structures of the foot ultimately causing inflammation, pain, injury and lameness. Soles vary in thickness but a uniform sole depth of 15mm is believed to be the minimum necessary for protection.

Dorso-palmar/plantar (front to back – DP) balance

Refers to the overall hoof angle and the alignment of the hoof angle with the pastern angle when the cannon bone is perpendicular to the ground surface. When assessing the foot from the side, the dorsal hoof wall should be aligned with the pastern. The optimal angle of the dorsal hoof wall is often cited as being 50-54°. The length of the dorsal hoof wall is variable but guidelines have been suggested according to the weight of the horse.

The heel and toe angle should be within 5 degrees of each other. An underrun heel has been defined as the angle of the heel being 5 degrees less than the toe angle. The heel wall length should be roughly 1/3 of the dorsal wall.

A line dropped from the first third of the coronet should bisect the base. A vertical line that bisects the 3rd metacarpal bone should intersect the ground at the palmar aspect of the heels.

Radiographs

A useful way to assess trimming and foot balance is by having foot x-rays performed. Radiography is the only thorough and conclusive method that allows one to determine if the foot is not balanced and the bony column (HPA) is aligned.

Shoes should be removed and the foot cleaned before radiographs are executed. The horse is often placed on foot blocks to elevate the feet off the ground so that the foot can be centered in the cassette and x-ray beam.

Latero-medial view – The side view of the foot allows one to assess the dorsal and palmar aspects of the pedal bone as well as the navicular bone. The horse should be standing squarely on a flat, level surface. This projection is useful in determining the point of breakover and the hoof pastern axis should be parallel with the hoof wall. The lateral view will demonstrate the length of the toe and the alignment of the dorsal surface of the pedal bone with the hoof wall, which should be parallel. This view also allows one to determine the depth of the sole and inadequate solar depth is usually accompanied with excessive toe length (broken-back HPA). One may observe a clubfoot, broken forward.

One can distinguish between a clubfoot and a broken-forward HPA with radiographs. The broken-forward HPA the hoof angle of the heel is greater than the angle of the dorsal hoof wall. The clubfoot also demonstrates these steep/high hoof angles but additionally the alignment of the coffin, short and long pastern bones are broken forward.

Dorsopalmar/plantar views - this “front to back” view is also performed with the horse standing squarely on 2 positioning blocks. This projection allows the evaluation of medial to lateral balance and conformation of the foot with observation and measurement of the medial and lateral wall length and angle. Horses with satisfactory conformation present with a parallel joint surface of the pedal bone to the ground. The coffin joint should be even across its width. In addition, the lateral and medial coronet and the lateral and medial walls are of equal thickness and the distance from the lateral and medial solar margins to the ground are similar.

With foot imbalance, this author has observed that fore feet may have a higher lateral hoof wall, whereas, the hind feet may have a higher medial hoof wall. It is worth noting that the pelvis, stifle and hocks are adapted to move laterally allowing a slight rotating action as it moves. This action may cause uneven wear or poor trimming and shoeing may cause this limb movement to be out of line.

Trimming

Often, trimming and shoeing are based on empirical experience that includes theoretical assumptions and aesthetic decisions. The goals of trimming and shoeing are to facilitate breakover, ensure solar protection and provide heel support. Trimming is the most important aspect of farriery because it creates the base to which a shoe is fitted. Hoof conformation takes into account the function and shape of the foot in relation to the ground and lower limb both at rest and exercise. Each individual foot should have a conformation that provides protection and strength while maximizing biomechanical efficiency often viewed as foot balance.

An important question that initially needs to be addressed is whether the horse requires shoes or not. The answer does depend on what type of work the horse performs, what is the amount of workload, the conformation of the horse (especially the limbs and foot) and are there any previous or current injuries. It must be stressed that the most important aspect, whether the horse is shod or not, is that the trim ensures an appropriately balanced foot for the horse. If there is poor trimming then this may lead to uneven and increased workload on the limb leading to an increased strain of the hoof and soft tissues (i.e. ligaments, tendons) that increase the risk of injury and developing acute and chronic lameness.

The foot can be evaluated, trimmed and/or shod in a consistent, reproducible manner that considers:

Hoof-pastern axis (HPA)

The center of articulation

Heels extending to the base of the frog

Appropriate trimming and shoeing to ensure the base of the foot is under the lateral cartilage; therefore, maximizing the use of the digital cushion, can help in creating a highly effective haemodynamic mechanism. Shoeing must be done that allows full functionality of the foot so that load and concessional forces are dissipated effectively.

To implement appropriate farriery, initially observe the horse standing square on a hard service to confirm that the HPA is parallel. If The HPA is broken forward or backward then these balances should be part of the trimming plan. To determine the location of the center of rotation, palpate the dorsal and palmar aspect of the short pastern just above the coronary band and a line dropped vertically from the center of that line should correlate with the widest part of the foot.

Shoeing

When the shoe is placed on the horse, the horse is no longer standing on its feet but on the shoe; therefore, shoeing is an extension of the trim. The shoe must complement the trim and must have the same biomechanical landmarks to ensure good foot balance. It is this author’s view that the shoe should be the lightest and simplest possible. The shoe must be placed central to the widest part of the foot and the distance from the breakover point to the widest part of the foot should be equal to the distance between the widest part of the foot and the heel.

It has been shown that the use of shoes that lift the sole, frog and bars can reduce the efficient workings of the caudal foot and may lead to the prevalence of weak feet. A study by Roepstorff demonstrated there was a reduced expansion and contraction of the shod foot but improved functionality of solar and frog support. With this information, appropriate shoeing should allow increased functionality of the digital cushion, frog and bars of the foot, which improves the morphology and health of the hoof and reduces the risk of exceeding the hoof elasticity.

Disease associated with hoof imbalance

As seen in the figure above, foot imbalance can lead to multiple ailments and pathologies in the horse. It must be noted that the pathologies that may result are not necessarily exclusive for the foot but may expand to other components to the horse’s musculoskeletal system. In addition, not one but multiple pathologies may result. Diseases that may result from hoof imbalance are:

Conclusion

Foot balance is essential for your horse to lead a healthy and sound life and career. With a strong understanding of the horse anatomy and how foot imbalance can lead to lameness as well as other musculoskeletal ailments, one can work to assess and alter foot balance in order to ensure optimal performance and wellbeing of the horse. It is essential that there is a team approach involving all stakeholders as well as the veterinarian and farrier in order to achieve foot balance. With focus on foot balance, one can make a good horse into a great horse.

**NEW** for 2024 - Bloodstock Briefing - Asking pinhookers if the shift in the 2yo sales season (to later dates) has influenced the type of horses they consign for sale

Article by Jordin Rosser

Even though term pinhooking came from the tobacco industry in Kentucky, it is widely used in the Thoroughbred racing industry as a concept where horses are bought at one stage of life and sold at another stage of development in the hopes of a profit based on the breaking, training and maturing process of these animals.

We have gathered a panel of pinhook sellers of both yearling to two-year-olds, weanling to yearlings, and breeders to discuss their thoughts on selection at sales and their view of the business. Our panelists include: Richard Budge, the general manager of Margaux Farm who oversees the breeding and training of yearlings and two-year-olds; Eddie Woods, a well-established two-year-old consignor and yearling pinhooker; Marshall Taylor, a thoroughbred advisor at Taylor Made – known for yearling consignments; Niall Brennan, a respected two-year-old consignor and yearling pinhooker.

Q: When selecting yearlings for pinhooking to the two-year-old sales or weanlings for the yearling sales, which qualities do you look for?

Many of the panelists concur on the primary qualities necessary for a prospective successful pinhook being conformation, pedigree, and clean vetting – but generally, wanting “quality”. Such traits include an early maturing body, muscle, good conformation, and pedigree for yearling pinhooks to two-year-olds. Some consignors weigh some of the main qualities with different weights, for example, Eddie Woods looks at the conformation of the prospect before the pedigree but will analyze sire lines and sire statistics to assist him in his selections. In contrast, Richard Budge starts with the pedigree then evaluates the conformation and analyzes the whole picture. For weanling to yearling pinhooks, the primary attributes to consider are pedigree, conformation, good movement, and early foaling dates. Marshall Taylor further discussed wanting to find a good-sized body, longer neck, laid back shoulders and good strides when walking. At the end of the day, “quality is a perception” as stated by Niall Brennan – these qualities are statistically likely to sell well in both the yearling sales and the two-year-old sales from the seller’s perspective.

Q: Given the two-year-old sales have decreased in number and have moved to later months, do you believe it has incentivized yearling selection and/or breeders to favor later maturing horses?

A resounding “no” came from the panelists. Looking back into the history of two-year-old sales gave a clearer picture as to why the sentiment has not changed. The main two-year-old sales currently are the OBS March, April and June sales in Ocala, Florida as well as the Fasig Tipton May and June sales in Timonium, Maryland. However, there used to be OBS February, Calder and Adena Springs sales, Fasig Tipton’s Gulfstream sale, and Barretts’ (a company whose final auction was in 2018) March and May sales in Pomona, California.

Niall Brennan commented that when the earlier sales were going on, the horses would “breeze within themselves easily” instead of breezing for the clock as is evident in today’s sales. Due to this emphasis, pinhookers noticed some horses needed more time to mature to run quicker times and with the horsemanship shown throughout the industry – all the panelists indicated that “the horse will tell you which sale it belongs in”. With the two-year-olds’ sales model having changed many variables, one variable that stayed the same is the horse attributes needed to be successful in these sales. Which leads to the conclusion being the same and sentiment remaining steady despite changes in the industry.

Q: Hypothetically, if the two-year-old sales changed from breezing to galloping with technological devices to provide metrics to analyze, do you think the market or breeders would change their strategies?

Most of the panelists believed this hypothetical would not work well for the two-year-old sales model. Some of the panelists discussed the Barretts sales model having horses gallop untimed instead of breezing or breezing with times in the 100ths. Niall Brennan commented that the granularization of the breeze times “caused more speculation from the buyers” and changed their perspective on the individual horses based on fractions of a second. The juxtaposition of sales with only untimed gallops and sales with timed breezes caused many buyers to “compare apples to oranges” – leading to a perceived dismissal of the idea.

In the current market and with the technology available today, this may not be possible, but Marshall Taylor believes “any information you have is good information” and “moving forward with technology is a positive”. In the future and with significant technological advancements, this hypothetical could be real. In the words of Niall Brennan, “the time will come when we aren’t worried about time [during breezing]”.

Q: In terms of breeding, what trends do you currently see and what trends do you want to see benefiting the pinhooking market?

The consensus from the panelists indicated breeding speed and quick maturing horses is the current trend in the pinhooking market. Richard Budge stated “precociousness is valued highly into the making of a stallion” in America. Marshall Taylor mentioned technology is used in making breeding decisions, particularly Nick reports. These use the daily updating percentage of stakes winner indexes to determine if sire and dam lines are compatible for the desired outcome culminating in a high performing racehorse.

Based on many of the responses in what type of weanlings or yearlings are selected at the beginning of the pinhooking process, the need for precocious and well-bred horses is no surprise. Richard Budge, believes that turf racing has become more popular and believes the growth of this segment in thoroughbred racing should encourage pinhooks to look for turf in their prospect’s pedigrees. However, the bloodlines will need to support this idea and the American breeders will need to include more English, French and South American bloodlines to adjust for these factors.

Q: Where do you see the pinhooking market right now?

The panelists all agree on this point: the buyer market is focused on quality over quantity and concentration of the buyer market. These trends encourage pinhookers to purchase weanlings or yearlings that tick all their boxes to produce quality prospects leading to increased prices as a function of competition. According to many panelists, the market is focused on what is perceived to be the “top end” – by pedigree, conformation, vetting, and/or under tack time. Based on the rising costs of ownership, Marshall Taylor mentioned “partnerships are becoming more popular” amongst the buyers, allowing owners to offset these increased costs.

———-

Throughout these interviews, it is apparent pinhookers have a keen ability to read the horses and determine how to bring their best on “NFL combine” day in the case of the two-year-olds. Niall Brennan and Richard Budge gave credit and appreciation to all the pinhookers who actively prepare these athletes and show their horsemanship through breaking, training, consigning, and breeding of these animals.

We see all the hard work that goes into preparing these athletes for race day through their accomplishments. To produce this feat on demand and to make money in the process is what pinhooking thoroughbreds is all about.

Factors for racing ability and sustainability

By Judy Wardrope

Everyone wants to be able to pick a future star on the track, ideally, one that can compete at the stakes level for several seasons. In order to increase the probability of finding such a gem, many buyers and agents look at the pedigree of a horse and the abilities displayed by its relatives, but that is not always an accurate predictor of future success. When looking at a potential racehorse, the mechanical aspects of its conformation usually override the lineage, unless of course, the conformation actually matches the pedigree.

For our purposes, we will examine three horses at the end of their three-year-old campaigns and one at the end of her fourth year. In order to provide the best educational value, these four horses were chosen because they offer a reasonable measure of success or failure on the track, have attractive pedigrees and were all offered for sale as racing prospects in a November mixed sale. The fillies were also offered as broodmare prospects.

Is it possible to tell which ones were the better racehorses and predict the best distances for those who were successful? Do their race records match their pedigrees? Let’s see.

Horse #1

This gelding (photographed as a three-year-old) is by Horse of the Year Mineshaft and out of a daughter of Giants Causeway, a pedigree that would suggest ability at classic distances. He brought a final bid of $275k as a yearling and $45k as a maiden racing-prospect at the end of his three-year-old year after earning $19,150. His story did not end there, however. He went back to racing, changed trainers a few times, was claimed and then won a minor stakes at a mile while adding over $77k to his total earnings. All but one of his 18 races (3-3-3) were on the dirt, and he was still in training at the time of writing.

Structurally, he has some good points, but he is not built to be a superior athlete nor a consistent racehorse. His LS gap (just in front of the high point of croup) is considerably rearward from a line drawn from the top point of one hip to the top of the other. In other words, he was not particularly strong in the transmission and would likely show inconsistency because his back would likely spasm from his best efforts.

Horse #1

His stifle placement, based on the visible protrusion, is just below sheath level, which is in keeping with a horse preferring distances around eight or nine furlongs. However, his femur side (from point of buttock to stifle protrusion) of the rear triangle is shorter than the ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock), which not only adds stress to the hind legs, but it changes the ellipse of the rear stride and shortens the distance preference indicated by stifle placement. Horses with a shorter femur travel with their hocks behind them do not reach as far under their torsos as horses that are even on the ilium and femur sides. While the difference is not pronounced on this horse, it is discernable and would have an effect.

He exhibits three factors for lightness of the forehand: a distinct rise to the humerus (from elbow to point of shoulder), a high base of neck and a pillar of support (as indicated by a line extended through the naturally occurring groove in the forearm) that emerges well in front of the withers. The bottom of his pillar also emerges just into the rear quarter of his hoof, which, along with his lightness of the forehand, would aid with soundness for his forequarters.

The muscling at the top of his forearm extends over the elbow, which is a good indication that he is tight in the elbow on that side. He developed that muscle in that particular fashion because he has been using it as a brake to prevent the elbow from contacting the ribcage. (Note that the tightness of the elbow can vary from side to side on any horse.)

He ran according to his build, not his pedigree, and may well continue to run in that manner. He is more likely to have hind leg and back issues than foreleg issues.

Horse #2

This filly (photographed as a three-year-old) is by champion sprinter Speightstown and out of a graded-stakes-placed daughter of Hard Spun that was best at about a mile. The filly raced at two and three years of age, earning $26,075 with a lifetime record of 6 starts, one win, one second and one third—all at sprinting distances on the dirt. She did not meet her reserve price at the sale when she was three.

Horse #2

Unlike Horse #1, her LS gap is much nearer the line from hip to hip and well within athletic limits. But, like Horse #1, she is shorter on the femur side of her rear triangle, which means that although her stifle protrusion is well below sheath level, the resultant rear stride would be restricted, and she would be at risk for injury to the hind legs, particularly from hock down.

She only has two of three factors for lightness of the forehand: the top of the pillar emerges well in front of the withers, and she has a high point of neck. Unlike the rest of the horses, she does not have much rise from elbow to point of shoulder, which equates with more horse in front of the pillar as well as a slower, lower stride on the forehand. In addition, the muscling at the top of her forearm is placed directly over her elbow… even more so than on Horse #1. She would not want to use her full range of motion of the foreleg and would apply the brake/muscle she developed in order to lift the foreleg off the ground before the body had fully rotated over it to avoid the elbow/rib collision. This often results in a choppy stride. However, it should be noted that the bottom of her pillar emerges into the rear quarter of her hoof, which is a factor for soundness of the forelegs.

Her lower point of shoulder combined with her tight elbow would not make for an efficient stride of the forehand, and her shorter femur would not make for an efficient stride of the hindquarters.

Her construction explains why she performed better as a two-year-old than she did as a three-year-old. It is likely that the more she trained and ran, the more uncomfortable she became, and that she would favor either the hindquarters or the forequarters, or alternate between them.

She did not race nearly as well as her lineage would suggest.

Horse #3

This filly (photographed as a three-year-old) is by champion two-year-old, Midshipman, and out of a multiple stakes-producing daughter of Unbridled’s Song. She raced at two and three years of age and became a stakes-winner (Gr3) as a three-year-old, tallying over $425k in lifetime earnings from 12 starts. Although she did win one of her two starts on turf, she was best at 8 to 8.5 furlongs on the main track. She brought a bid of $775k at the sale and was headed to life as a broodmare.

Horse #3

Her LS gap is just slightly rearward of a line drawn from hip to hip and is therefore well within the athletic range. Her rear triangle is of equal distance on the ilium and femur sides, plus her stifle protrusion would be just below sheath level if she were male. She has the engine of an 8- to 9-furlong horse and the transmission to utilize that engine.

Aside from all three factors for lightness of the forehand (pillar emerging well in front of the withers, good rise of the humerus from elbow to point of shoulder and a high base of neck), the bottom of her pillar emerges into the rear quarter of her hoof to aid in soundness.

Although she shows muscle development at the top of her forearm, the muscling does not extend over her elbow the way it does on the previous two horses. Her near side does not exhibit the tell-tale muscle of a horse with a tight elbow, and thus, she would be comfortable using a full range of motion of the forehand.

Proportionately, she has the shortest neck of the sample horses, which may be one of the reasons she has developed the muscle at the top of her forearm. Since horses use their necks to aid in lifting the forehand and extending the stride, she may compensate by using the muscle over her humerus to assist in those purposes.

Of the sample horses, she is the closest to matching heritage and ability.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 55 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 55 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.95

Conformation and breeding choices

By Judy Wardrope

A lot of factors go into the making of a good racehorse, but everything starts with the right genetic combinations, and when it comes to genetics, little is black and white. The best we can do is to increase our odds of producing or selecting a potential racehorse. Examining the functional aspects of the mare and then selecting a stallion that suits her is another tool in the breeding arsenal.

For this article we will use photos of four broodmares and analyze the mares’ conformational points with regard to performance as well as matings likely to result in good racehorses from each one. We will look at qualities we might want to cement and qualities we might hope to improve for their offspring. In addition, we will look at their produce records to see what has or has not worked in the past.

In order to provide a balance between consistency and randomness, only mares that were grey (the least common color at the sale) with three or more offspring that were likely to have had a chance to race (at least three years old) were selected. In other words, the mares were not hand-picked to prove any particular point.

All race and produce information was taken from the sales catalogue at the time the photos were taken (November 2018) and have not been updated.

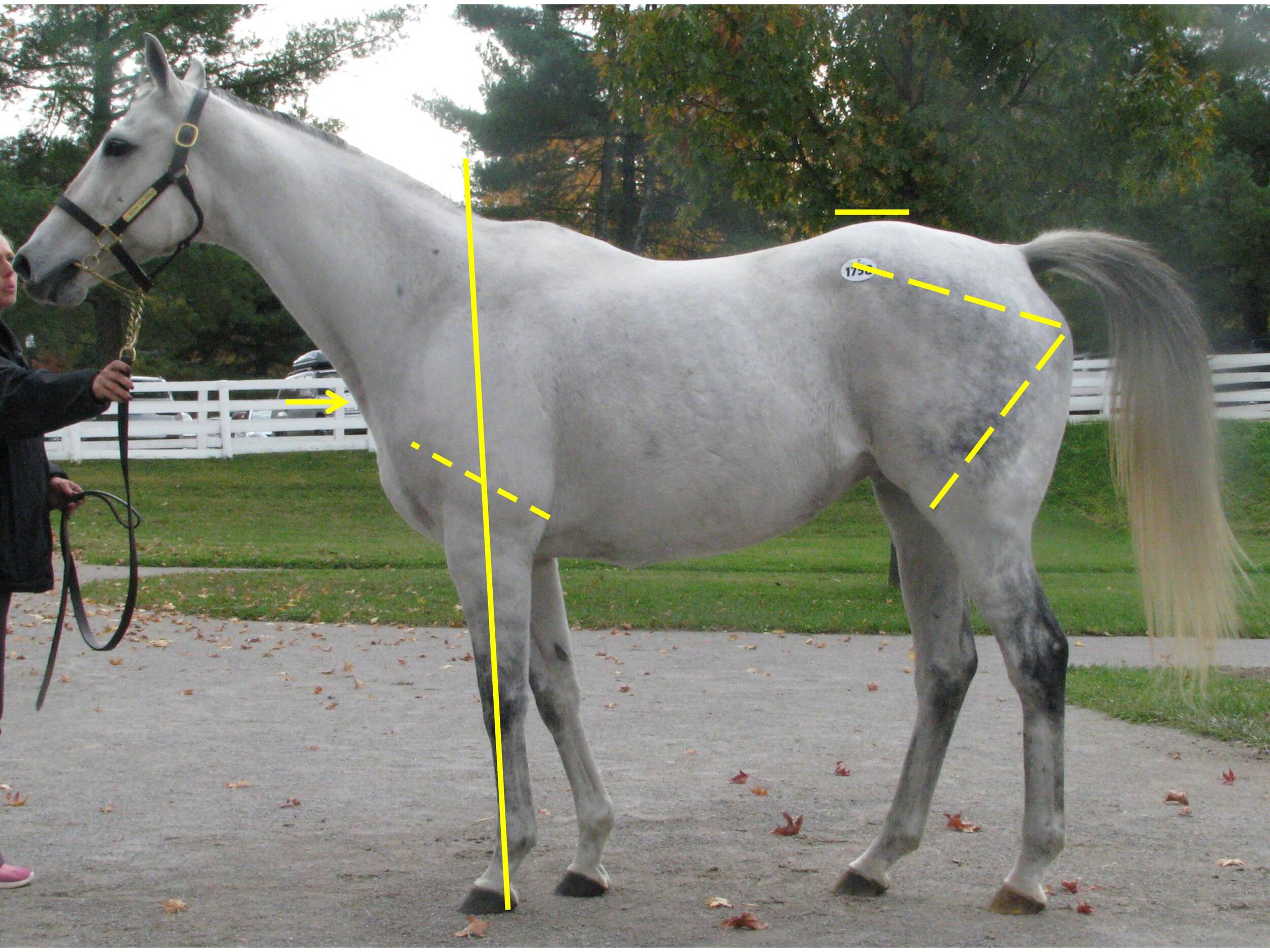

Mare 1

Her lumbosacral gap (LS) (just in front of the high point of croup, and the equivalent of the horse’s transmission) is not ideal, but within athletic limits; however, it is an area one would hope to improve through stallion selection. One would want a stallion with proven athleticism and a history of siring good runners.

Mare 1

The rear triangle and stifle placement (just below sheath level if she were male) are those of a miler. A stallion with proven performance at between seven furlongs and a mile and an eighth would be preferable as it would be breeding like to like from a mechanical perspective rather than breeding a basketball star to a gymnast.

Her pillar of support emerges well in front of the withers for some lightness of the forehand, but just behind the heel. One would look for a stallion with the bottom of the pillar emerging into the rear quarter of the hoof for improved soundness and longevity on the track. Her base of neck is well above her point of shoulder, adding additional lightness to the forehand, and she has ample room behind her elbow to maximize the range of motion of the forequarters. Although her humerus (elbow to point of shoulder) shows the length one would expect in order to match her rear stride, one would likely select a stallion with more rise from elbow to point of shoulder in order to add more lightness to the forehand.

Her sire was a champion sprinter as well as a successful sire, and her female family was that of stakes producers. She was a stakes-placed winner at six furlongs—a full-sister to a stakes winner at a mile as well as a half-sister to another stakes-winning miler. Her race career lasted from three to five.

She had four foals that met the criteria for selection; all by distance sires of the commercial variety. Two of her foals were unplaced and two were modest winners at the track. I strongly suspect that this mare’s produce record would have proven significantly better had she been bred to stallions that were sound milers or even sprinters.

Mare 2

Her LS placement, while not terrible, could use improvement; so one would seek a stallion that was stronger in this area and tended to pass on that trait.

The hindquarters are those of a sprinter, with the stifle protrusion being parallel to where the bottom of the sheath would be. It is the highest of all the mares used in this comparison, and therefore would suggest a sprinter stallion for mating.

Mare 2

Her forehand shows traits for lightness and soundness: pillar emerging well in front of the withers and into the rear quarter of the hoof, a high point of shoulder plus a high base of neck. She also exhibits freedom of the elbow. These traits one would want to duplicate when making a choice of stallions.

However, her length of humerus would dictate a longer stride of the forehand than that of the hindquarters. This means that the mare would compensate by dwelling in the air on the short (rear) side, which is why she hollows her back and has developed considerable muscle on the underside of her neck. One would hope to find a stallion that was well matched fore and aft in hopes he would even out the stride of the foal.

Her sire was a graded-stakes-placed winner and sire of stakes winners, but not a leading sire. Her dam produced eight winners and three stakes winners of restricted races, including this mare and her full sister.

She raced from three to five and had produced three foals that met the criteria for this article. One (by a classic-distance racehorse and leading sire) was a winner in Japan, one (by a stallion of distance lineage) was unplaced and one (by a sprinter sire with only two starts) was a non-graded stakes-winner. In essence, her best foal was the one that was the product of a type-to-type mating for distance, despite the mare having been bred to commercial sires in the other two instances.

TO READ MORE - BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 54 (PRINT)

$6.95

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.9

Pedigree vs Conformation

By Judy Wardrope

What are the factors people consider when assessing a potential racehorse? In part, it depends on their intentions. Different choices may be made if the horse or offspring is intended for their own use or how the horse or offspring might sell.

And when a horse gets to the track, what factors help a trainer decide on a particular distance or surface to try? Most of the trainers I interviewed say that they usually look at who the sire is when trying to determine distance and/or surface preferences.

Trainer Mark Frostad said, “I look at the pedigree more than the individual regarding distance and surface.”

Richard Mandella says that his determining factors are “conformation, style of action, pedigree and the old standby, trial and error.”

Roger Attfield says, “It is extremely hard to tell turf versus dirt. I’ve watched horses all my life and I’ve tried to figure it out. I can tell when I start breezing them. I had a half-sister [to Perfect Soul], who was stakes-placed, and she couldn’t handle the turf one iota. I had the full brother…also turf. Approval could win on the dirt, but as soon as he stepped on the turf, he was dynamite.”

What about when planning a potential breeding for a mare or a stallion? Is conformation more important than pedigree? Or does pedigree have more influence than conformation? How much of a role does marketing play in the selections?

Although ancestry and conformation do go together, the correlation is complicated. For example, top basketball players tend not to come from families of short people, but most NBA stars do not have siblings who are star players. The rule holds for other athletes, including gymnasts. But what would you get if you crossed a basketball player with a gymnast?

Pedigree is not an absolute despite what marketing campaigns may lead you to believe. Look at human families—maybe even your own. Are you built like all of your siblings, do you all have the same talents? And what about your cousins? Are you all built alike and of equal talent?

When it comes to Thoroughbred horses, you will find that only the very top sires boast a percentage of stakes winners nearing 15%. If one assumes that a stakes winner is the goal of most breeders, then that would indicate at least an 85% failure rate.

When breeding horses or selecting potential racehorses, the cross might look good on paper or in our imaginations, but what are the odds that the offspring would be able to perform to expectations if it was not built to be a success at the track? Looking at the big picture, one has to wonder what we are doing to the gene pool if we only breed for marketability.

To get a better understanding, let’s look at four horses. Three of our sample horses have strong catalog pages, but did they run according to their pedigrees or according to the mechanics of their construction? Furthermore, did the horse with the humdrum catalog page have a humdrum racing career?

Ocean Colors

PEDIGREE

She is by Orientate, a campion sprinter of $1,716,950 (including a win in the Breeders' Cup Sprint [Gr1], who sired numerous stakes horses and was the broodmare sire of champions.

Her dam, Winning Colors, earned $1,526,837, was the champion three-year-old filly and beat the boys in the Kentucky Derby [Gr1] and the Santa Anita Derby [Gr1]. She was a proven classic-distance racehorse.

Winning Colors was the dam of 10 registered foals, 9 to race, 6 winners, including Ocean Colors and Golden Colors (a stakes-placed winner in Japan, who produced Cheerful Smile, a stakes winner of $1,878,158 in North America), and she is ancestor to other black-type runners.

CONFORMATION

Her lumbosacral gap (LS), which is just in front of the high point of croup and functions like the horse's transmission, is considerably rearward of ideal. This constitutes a significant difference when compared to either of her athletic parents.

The rear triangle is equal on the ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock) and femur side (point of buttock to stifle protrusion), and her stifle is well below where the bottom of the sheath would be if she were male. In essence these would contribute to the long, ground-covering stride seen in distance horses like her dam.

Her pillar of support (a line extending through the natural groove in her forearm) emerges well in front of her withers for some lightness to the forehand and into the rear quarter of the hoof for added soundness.

Her base of neck is neither high nor low when compared to her point of shoulder, meaning that placement neither added nor subtracted weight on the forehand.

Because her humerus (elbow to point of shoulder) is not as long as one would expect for a range of motion that would match that of her hindquarters, she likely resembles her sprinter lines in this area. Although I never saw her race, I strongly suspect that her gait was not smooth. In order to compensate for a shorter stride in the front than in the back, she probably wanted to suspend the forehand while her hindquarters went through the full range of motion. Unfortunately, she is not strong enough in the LS to effectively use that method of compensating.

RECORDS

Her race record shows her as a stakes-placed mare and winner of $127,093 but closer examination shows that the stakes race was not graded with a small purse and that her three wins, two seconds and three thirds were not in top company.

While valuable on paper as a broodmare, and despite being mated to some top stallions early in her breeding career, she failed to produce a quality racehorse. Naturally her value dropped significantly until she sold in November 2018 for $20,000 in foal to Anchor Down.

Sequoyah

PEDIGREE

His sire, A.P. Indy earned $2,979,815, won the Breeders’ Cup Classic and the Belmont Stakes plus was the Eclipse Champion three-year-old and Horse of the Year. He was also a top sire of stakes horses as well as a noted sire of sires.

His dam, Chilukki, earned more than $1.2 million, was the Eclipse Champion two-year-old filly, was second in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies, and set track records at Churchill Downs for both 4.5 furlongs and a mile. Her sire won the Breeders’ Cup Sprint and equaled a track record for 7 furlongs.

CONFORMATION

His LS is 1.5” (by actual palpation) rearward of ideal and just at the outer limits of the athletic range.

His rear triangle is slightly shorter on the femur side (point of hip to stifle protrusion), which not only decreases the range of motion of the rear leg by changing the stride’s ellipse, but it adds stress to the hind leg from hock down.

The stifle placement (well below sheath level) would indicate a preference for distances around 10 furlongs (similar to his sire’s), except for the short femur.

His pillar of support does emerge in front of the withers, but the bottom of the line emerges behind the heel, making him susceptible to injury to the suspensory apparatus of the foreleg (tendons and ligaments).

His humerus is of medium length and is moderately angled and would represent a range of motion that would match the hindquarters. However, the tightness of his elbow (note the circled muscling over the elbow) would likely prevent him from using the full range of motion. He would stop the motion before the elbow contacted his ribs; thus, the development of that particular muscle as a brake and a reduction in stride length. His base of neck was well above point of shoulder, which adds some lightness to his forehand.

RECORDS

He was injured in his only start and had zero earnings. He did go to stud based on his pedigree, but was not a success. He sired one stakes winner of note, a gelding out of a stakes-winning Smart Strike daughter, who won at distances from 7 to 9 furlongs.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (PRINT)

$6.95

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PRINT & ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION

$24.95