Stable standards - are racecourses forgetting the horse?

The thoroughbred industry is fairly diverse, with factions arguing their own importance.

Without breeders, we have no horse. Without owners, we have no racing. And without the racehorse, we have no need of racecourses. Racecourse Manager Bill Farnsworth identifies this basic point when he speaks of the stabling facilities at Musselburgh. But sadly, many racecourses in Britain and Ireland are missing the point altogether, and the horse—as Farnsworth refers to an athlete—is the least of their priorities.

The image of half a bale of shavings in a box at Killarney racecourse is a stark one. It is physically awkward to cut a bag and to carry an open bag.

How many of us would bother to go to such penny- pinching lengths at home? Indeed, one Irish trainer pointed out that the provision of just half a bale of shavings per box in a racing yard would certainly incur penalties from any IHRB (Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board) stable inspection. Although the IHRB does not include racecourse stabling standards within its Rules, its veterinary department accepts that half a bale is adequate for race day use. Yet in England, there has been at least one withdrawal due to the minor injuries sustained by a horse rolling in a box with inadequate shavings.

With multiple complaints from British and Irish trainers, a naming and shaming of offending racecourses would have made for a very long and already well-known list. Instead, we might look at those countries who have got it right throughout their tracks, and the racecourse in Britain consistently mentioned as setting the gold standard.

In Germany, trainers seem surprised to be asked about the quality of racecourse stables. Dominik Moser is typical when he explains, “We don’t have a problem with racecourse stabling—90% are on straw, 10% shavings; and where we have shavings, we have three bales per box. The cost of straw has increased this year due to the heavy rains and slight shortage, but it isn’t a problem. I like to see good- sized boxes. I don’t like to see a horse lying down if it doesn’t have enough room.”

Similarly, it isn’t lack of bedding that’s an issue in France but sometimes in the province’s lack of stabling. “We have no problem with hygiene or bedding at racecourse stables,” Gavin Hernon says, “but the problem we have is at smaller tracks when there might be no stable available or we could be sharing with an earlier runner. To be fair, I’ve never had a complaint.”

In recent years, in cases of positive post-race tests in France, the most common cause has been cited as contamination of racecourse stabling, which has led to much more stringent hygiene. “I suppose you could say that one good thing, as a result of that, is that now when you come to the racecourse stables, each box has a plastic seal and you have to break it to enter,” reveals Gina Rarick. “So we can be sure that every box has been disinfected and has clean straw.

“Most of our bedding in France is straw, and there is always enough at the races. If you want to have shavings instead, you have to book in advance and it’s quite expensive. You’ll pay €50-€60, and for that you’ll only be given two bales.

“The worst case I found was in Lyon—there was so much straw in the box and such a lot of dust, the horse started coughing immediately. Deauville always has plenty of bedding, and they use good quality straw. It’s really nicely done, and I find they are really accommodating. Other racecourses can be hit and miss; there is no rule on any set standard.”

Like Hernon, Rarick finds it is the lack of boxes that can be an issue at smaller tracks, particularly after a long journey to get there. Bear in mind that some tracks can be more than eight hours from the main training centres. “The biggest problem I find is that sometimes there are not enough boxes; and at some racecourses out in the country, there are none at all. You are working from the truck,” she says. “When there are too many runners and not enough boxes, the later runners use the same boxes as the earlier runners, which is not really great if you have a later runner. And then in contrast, you might get Chantilly, for example, (who uses) the number of available boxes as an excuse not to have a race; while at other racecourses, they are happy to double up.”

And Rarick raises another point when she notes, “I think it’s unique to France, but there is also a security issue. It seems as though anyone can just wander into the racecourse stables with very few questions asked. So if you’re concerned about that and your horse’s safety, you have to take it upon yourself to be looking after your horse for the whole time it’s there. But really, I think as trainers we kind of like that—not having to be constantly showing the right passes at every gate. It’s very relaxed.”

So that, at least, is how ‘the other half ’ live with the complaint of too much straw, no doubt breaking many Irish hearts. Like in France and Germany, the standard of stabling at Irish racecourses is not written into the Rules.

Michael Grassick, CEO of the IRTA (Irish Racehorse Trainers Association) explains, “It’s at the discretion of the racecourse, but half a bale of shavings is standard, with paper available as an alternative on request. I know a lot comes down to the cost, but the reason behind the half bale is that if there were a deeper bed, it would encourage the horse to roll. We don’t have overnight stays here in Ireland, and horses don’t have so far to travel to the races; so it’s not the issue it is in the UK or some other countries. I would say 99% of trainers find the stabling at Irish racecourses reasonable.”

However, several trainers, including those based in Northern Ireland who still come under the IHRB jurisdiction, are far from happy. With so much media attention on equine welfare, the argument is that half a bale of shavings is totally insufficient for a horse, which might arrive at the races four hours early.

Amanda Mooney

Amanda Mooney tells us, “I am a small trainer in County Meath, and horses are everything to me. All are treated as individuals in my yard and all their needs met to a high standard. I am at a loss when I go racing and feel it’s so wrong that a top athlete—who needs a good thick bed underneath them to pee or feel relaxed—is then asked to deliver what they are trained for, but it is not made comfortable by racecourses.

“As instructed by the IHRB veterinarian, they only need half a bag of shavings in the stable at the racecourse even though they could be stood in the stable for a good few hours before and after their race. If I were to leave a racehorse in a stable at home with just half a bag of shavings on concrete, would this be acceptable to a vet?”

Most trainers raised the issue of the horse’s reluctance to urinate where lack of bedding caused splashing. A comparison to eventing was made, where temporary boxes are made up to match the comfort the horse would be used to at home.

The provision of a safe, non-slip area for trotting up for veterinary inspections was another common appeal. Amanda Mooney points out, “I have a horse who has a very slightly enlarged fetlock, which has never given him any problems and was like this when purchased from Godolphin. I, like all trainers in Ireland when getting our licence, have undertaken to look after all the horses in my care to a top standard, which includes not running a horse if lame or sore. Every time he runs, he is subjected to rigorous joint movement and then required to trot up, which I’ve refused on the grounds of unsuitable surfaces. I have even given a full vet report on the horse for all vets to read at the course.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Looking after our jockeys - Q&A with Denis Egan

Author - Dr. Paull Khan

In this issue, we conclude our series of Question and Answer sessions with the chairs of the various committees that operate in the EMHF region.

Following our features on the Pattern and doping control, we turn our attention to the well-being of our human athletes, the jockeys.

Denis Egan, who until recently was CEO of the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board, has also been the driving force within the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) when it comes to the welfare of riders. Not only does he chair the European Racing Medical Officers Group, but he has also been at the helm of the global International Conference for the Health, Safety and Welfare of Jockeys (ICHSWJ) since its inception some 15 years ago.

This time, our questions have been posed by various jockeys’ associations.

Q: What is the ICHSWJ?

DE: The ICHSWJ is a biennial conference for racing administrators, racecourse doctors, researchers and jockeys’ associations. The first conference was held in Tokyo (Japan) in 2006, and the ICHSWJ was officially recognised as one of the sub-committees of the IFHA in 2009. There have been eight conferences to date, which were held in Tokyo, Japan (2006), Antalya, Turkey (2008), Monmouth Park, USA (2012 & 2013), Hong Kong (2015) and Dubai, UAE (2010, 2017 and 2019).

The conference features presentations from the world’s leading racing administrators, racecourse doctors and researchers who work closely with jockeys both on the racecourse and through research studies. We are hoping to hold the next conference in Dubai in 2022, subject to COVID-19 restrictions being lifted.

Q: What is the charter of the ICHSWJ?

DE: The mission of the ICHSWJ is to provide a forum to discuss and implement strategies to raise the standards of safety and the standards of care provided to jockeys and to create a safer and healthier everyday life for jockeys when they participate in the sport.

The ICHSWJ has seven strategic objectives, namely to:

• RAISE awareness of jockeys’ health, safety and welfare issues

• HARMONISE standards and procedures throughout the world

• HARMONISE the collection of injury data

• PROVIDE a forum for the sharing of information

• SHARE research findings and foster collaboration

• PROPOSE strategies to deal with issues on a global basis

• SET UP a more effective communication mechanism between countries

Q: What do you see as the main focus by the attendees and presenters re jockeys’ health, safety and welfare?Is it bone health, making weight in a healthy manner (e.g., saunas, nutrition and fluid intake), concussion, injuries and falls, psychological/mental health issues, PPE (e.g., helmets and vests), or all of the above?

DE: It is all of the above with an increasing focus on mental health, concussion and making weight safely.If you look back at the agendas for the eight conferences that have taken place, the focus of the initial conferences was on what could be described as ‘traditional’ jockey issues such as weights, injuries and safety equipment, with little or no research having been carried out in any of the areas. Now everything has changed, and the focus is on the increasing amount of research that has been carried out in jockey health and safety-related issues. In Ireland we have been funding research since 2003, and many other countries have now developed their own research programmes. There is now much greater research collaboration between countries than there would have been in the past, and this has contributed to better results.

The one thing that has surprised me most is the huge focus that is now on mental health. The first time it appeared on a conference agenda was in 2017, and it has now become such a major issue everywhere. There have been numerous studies carried out that have found there are significant levels of depression amongst jockeys; and the industry is now addressing this with most countries putting better support in place for jockeys.

Studies have found that the life of a jockey has major highs and lows, and while success is a high, there are far more lows such as wasting, injuries, failing, travelling and social media abuse, which can be very hard to take. Studies have also found that there is a complex interplay between physical and psychological challenges: weight, dehydration, making weight and mood.

Q: What do you think is the number one issue facing jockeys at the moment?

DE: There is no doubt that the number one issue facing jockeys at the moment is mental health; and the fallout from this is being addressed by both the governing bodies in collaboration with the jockeys, which is the way to go. Many countries make sports psychologists available for jockeys if they want to use their services. We have been doing this in Ireland for many years, and while some jockeys may have been reluctant to use these services in the past, more and more have come to realise the benefit of the service.

Q: There has been a lot of research into mental health and wellbeing issues in jockeys, especially in Ireland and the UK. What can governing bodies do to either proactively improve jockeys’ mental wellbeing or support those with issues?

DE: Practically every governing body is now aware of the importance of jockeys’ mental health and wellbeing. The best way of helping jockeys is to be aware of the issues they are facing and to work with the jockeys’ associations to address these issues. The recent collaboration between the Professional Jockeys Association in Great Britain and the BHA is testament to what can be achieved by working together where an outcome was delivered that benefited everyone.

The other way governing bodies can assist is through education and the provision of support services to jockeys, which are easily accessible. Jockeys sometimes need to be educated in the sense of making them aware of what is available and how the services can be accessed. It is sometimes difficult to encourage jockeys to use mental health support services as some see it as a sign of weakness that they need to access these services; and they don’t want their weighing room colleagues to know that they perceive themselves as having issues. In reality, it is a sign of mental strength that they (are) able to make the decision that they need the service.

Q: The issue of burnout is one that is increasing across all sports. How do you feel governing bodies deal with or recognise this as an issue?

DE: It is now being dealt with far better than it was in the past. Great Britain recently announced that jockeys will be restricted to riding at one meeting per day in 2022. This is the second year that this has occurred, and this was agreed in cooperation with the jockeys’ association there. In Ireland there was a holiday for the professional jump riders for a three-week period in early June this year. This worked very well as it gave the jockeys an opportunity for some down time to recharge and take a holiday.

Burnout may not be as big an issue for riders in countries where there are a small number of racecourses or where there is a restricted racing season, but nevertheless, all governing bodies need to be aware of it.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Willie McCreery - the leading Irish flat trainer who is a master at the game of patience

By Lissa Oliver

Master at the game of patience

There is nothing superficial about Rathbride Stables, a traditional yard on the very coalface of the history-steeped Curragh Plains of Kildare. And there’s nothing superficial about Willie McCreery, either. Like most modern yards, the atmosphere is relaxed. McCreery appears laid back, and the staff arrive at 7 a.m. and calmly set about their tasks—the routine as smooth as a well-oiled machine. There are no instructions being given and none needed; teamwork is at its finest.

But there’s a keenness here, too—a simmering energy beneath the calm exterior. McCreery is quietly watchful and aware of every nuance. This is a man who loves what he does and just happens to be very good at it, too. The Wall of Fame in the office bears testament to the success—no better example being Fiesolana, the Gp1 Matron Stakes heroine. Improving every season and gaining a first Gp1 win for McCreery and his team as a five-year-old, she’s a good example, too, of McCreery’s patience and expertise with fillies and older horses, for which he has gained something of a reputation. Her now five-year-old Galileo colt, Up Helly Aa, is also keeping Group company under the tutelage of McCreery.

This is thanks largely to the patronage of owner-breeders. While some trainers survive on sharp two-year-olds and trading, McCreery acknowledges that having the perceived luxury of time with horses that have a longer career ahead comes with its own challenges.

‘Not selling horses and training for owner-breeders brings even more pressure’, he points out. ‘A win becomes more important, and then when they’ve had their win, you’re looking for black type. If they don’t get a win, it’s worse than if they don’t race at all; poor performances run the risk of devaluing the whole family. It comes down to making the right call, being sure enough from what they’re doing at home that they can do well and improve the family; or maybe having to risk the decision not to run them’.

Rathbride Stables, once home to Flashing Steel and where the Irish Grand National winner is now buried, has been home to McCreery since 2010. He had taken out a licence and sent out his first winner two years earlier. The original loose boxes are companion boxes, with the window through to the next box at the feed trough. ‘They can have a chat with their neighbour and have a nibble at the same time’, McCreery says. ‘It encourages them to feed, and I’m a fan of anything that gets them eating well.

‘I feed as best as I can. I hope to be second to none in that respect. I use a combination of Connolly’s Red Mills mix and nuts, and also alfalfa imported from Italy. I’ve picked it up along the way. I’m a firm believer in staying ahead of your feed, and if a horse is a little off, cut back straight away. I feed four times a day’.

McCreery starts his day in the yard at 6 a.m. with the first of the feeds, and he’ll turn out any of the horses not working that morning. That day’s runners will go out in the paddocks in the evening after returning from the races and again the next morning. Rathbride has 40 acres of turnout paddocks, as well as a 400m covered wood chip ride, and is currently home to 60 horses.

It’s ideally situated and well chosen. ‘We can just walk across to the gallops; we’ve the vet just beside us, and we’re within an hour of six tracks. As an example, I had a horse injured on the Old Vic gallop at 7.40 a.m. and he was X-rayed, diagnosed and back in his box—all by 9 a.m. I’m very lucky; any issue at all, and I have the vet with me in five minutes. I can drop blood samples in and have the results in 10 minutes’.

In the pre-COVID days, McCreery liked to give his horses days out, particularly at Dundalk where they could walk round the parade ring in front of a race crowd and gain experience. He also found the local equine pool a great help for horses who enjoyed it, but that’s now closed. ‘I would love to be near a beach; sea water does a great job’, he says. ‘But I’m not a fan of spas. They can mask the injury, and the problem is still going to be there. They’re okay for sore shins’.

Training racehorses was always in his blood; McCreery’s father Peter had enjoyed great success as a National Hunt trainer, and his older brother Peter Jr by coincidence sent out Son Of War to win the Irish Grand National the year before Flashing Steel’s success. We might wonder why McCreery chose the Flat in preference….

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

How breastplates and breast girths can inhibit performance

By Dr Russell Mackechnie-Guire

Using pressure mapping and gait analysis technology, scientists have now measured how breastplates and breast-girths can compromise the horse’s jump and stride at gallop.

Breast girths and breastplates are routinely used to prevent the saddle moving backwards at home on the gallops, and on the track. Post-race bruising to the pectoral muscles, sternal abrasions, soreness and even lacerations caused by a breastplate are often accepted consequences of keeping the saddle in place. But evidence is mounting that, in addition to the physical factors, a poorly designed breastplate or badly fitted breast-girth could also be restricting the horse’s gallop and compromising its jump during a race, therefore impacting the horse’s locomotor efficiency, performance and athletic potential.

Recent research in the sports horse has demonstrated that breastplates have a significant negative effect on the horse’s action over a fence. A further pilot study looking at how breast girths and breastplates affect the racehorse indicates that they influence the movement of the shoulder and forelimbs whilst galloping, potentially comprising gallop efficiency.

Jumping short

PIC 1– Pliance pressure mapping revealed the point of peak pressure common to all breastplates in the test occurred at the point of take-off.

In the sports horse jumping study, scientists used Pliance pressure mapping (pic 1) to identify areas of peak pressure beneath traditionally fitted breastplates. A sensor mat placed between the breastplate and the horse’s skin recorded levels of pressure throughout the jump cycle. Regardless of breastplate design, the highest pressures were consistently seen in the centre of the chest (located on the midline over the sternal region), at the moment of take-off as the horse’s shoulder, elbow and knee were flexed and the shoulder was in its most forward position (point P, pic 2).

PIC 2 - Without a breastplate (top), the horse’s jump forms a smooth parabolic trajectory over the fence from take-off to landing (A).

Alongside pressure mapping, two-dimensional gait analysis was utilised to determine how pressures created by breastplates affected jumping technique. Markers were placed on the horse’s joints, and the horse’s jump was analysed at a rate of 300 frames a second—approximately 25 times faster than the human eye. The data quantified any changes in joint and limb angles. The findings demonstrated that the whole jump is adversely affected by the breastplate design and resultant pressures from the point of take-off to, and including, the stride immediately after landing.

Without a breastplate, the horse’s natural jump is a parabolic (symmetrical) curve, with the highest point an equal distance between take-off and landing. In the study, a breastplate was shown to shorten the horse’s landing position by 0.5m compared to landing with no breastplate.

With a breastplate (bottom), the horse’s lead foot makes contact with the ground much closer to the fence (B), and the landing phase of the jump is steeper.]

This pattern of an altered trajectory was scientifically recorded under experimental conditions over one single oxer fence (1.2m) on a level surface. Applying the same principles to the racehorse, the negative impact that this would have when galloping would be magnified. If the horse’s trajectory over a brush fence is shortened by the same distance as it is over a 1.2m jump, this is likely to have a significant effect on gallop efficiency—in particular stride rate, length and frequency. Over a course of 12 National Hunt fences, if half a metre of ground is lost (as a function of the altered landing trajectory) at every jump, this would require six metres to be made up over ground—potentially the length of a winning stride.

Crash landing….

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Doping control in European racing the role played by the EHSLC

By Dr Paull Khan

AN Q&A INTERVIEW WITH HENRI POURET,

CHAIR OF THE EUROPEAN HORSERACING SCIENTIFIC LIAISON COMMITTEE

In this issue, we continue our series of Question and Answer sessions with the chairs of international committees in the European and Mediterranean regions. We began (Issue 72) with the subject of classifying the major, Black Type races across Europe, with our interview with the chair of the European Pattern Committee, Brian Kavanagh. Here, we move on to the subject of doping control, which is the remit of the European Horserace Scientific Liaison Committee. Its chair, Henri Pouret, answers your questions.

The EHSLC lists these amongst its Terms of Reference:

With the aim of achieving uniformity of approach, to provide advice to the Racing Authorities of the member countries on policy, scientific and procedural matters concerning the Rules of Racing as they relate to prohibited substances.

To recommend alterations to the Rules of Racing as they relate to prohibited substances.

To recommend common policies and procedures where appropriate in the areas of sample collection, sample testing (including confirmatory analysis) and prohibited substances, and to monitor compliance by the member countries with these policies and procedures.

To agree whether specified drugs fall within the List of Prohibited Substances.

To recommend the need, where appropriate, for new or varied threshold levels, for inclusion in the Rules of Racing.

To promote liaison and discussion between the official racing laboratories and the official racing veterinary surgeons of the member countries.

To promote inter-laboratory drug testing programmes, and to monitor the results vis-à-vis the official racing laboratories of the member countries.

To agree with research priorities and to promote joint approaches, where appropriate, for their achievement.

To publish detection periods, agreed jointly between the official racing laboratories and other interested parties in the member countries for therapeutic drugs commonly used in the horse.

To exchange drug intelligence and other relevant information between the member countries.

Pouret, who has a background in law, is the Deputy CEO of France Galop, in charge of racing and also represents France on the International Federation of Horseracing Authority’s (IFHA’s) Harmonisation of Racing Rules Committee.

Q: Let’s get some definitions out of the way first. One of the EHSLC’s Terms of Reference is ‘to recommend the need, where appropriate, for new or varied threshold levels, for inclusion in the Rules of Racing’. What is the difference between a ‘threshold level’ and a ‘screening limit’?

‘Threshold level’ and ‘screening limits’ are two critical indicators for doping control determined in urine and/or plasma.

A ‘threshold level’ is a numerical figure adopted by racing authorities for endogenous substances produced by horses and for some plants traditionally grazed and harvested to horses as feed. International thresholds are recommended by the IFHA’s Advisory Council on Equine Prohibited Substances and Practices and approved by the IFHA Executive Council.

A ‘screening limit’ (SL) is also a numerical figure determined by experts for legitimate therapeutic substances. Some are harmonised internationally and some are harmonised regionally (e.g,. within EHSLC for Europe).

Both ‘threshold level’ and ‘screening limit’ are applied by racing laboratories as a reference for the reporting of positive findings.

Q: On the IFHA website, there are lists published of ‘international screening limits’ and ‘residue limits’. How do these differ?…

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Prick test: Could the ancient Chinese therapy of acupuncture be a trainer’s secret weapon?

By Alysen Miller

At first glance, the Curragh (Ire) based trainer Michael Grassick Jr. may appear to have little in common with NBA legend Shaquille O’Neal. Yet both have embraced a practice derived from traditional Chinese medicine in their quests to leave no margin left ungained when it comes to minimising pain and maximising performance.

Acupuncture may be a controversial subject for some within the equestrian community, but its potential to treat illness and injury and alleviate pain in horses is increasingly being recognised.

“My father used to use it a lot when he was training, so when I took over [in 2013], I continued it,” says Grassick Jr. “I found it very successful. If the lads feel something isn’t quite right, like they’re leaning a little bit or hanging a little bit, then you call the physio. He will pinpoint the area, and we’ll work on that area and usually you wouldn’t need him to look at it again.”

“It’s something I was interested to witness—seeing them, how they respond,” he continues. “You’d see they’d be a lot freer in themselves.”

Although acupuncture has been part of the programme for the equine inhabitants of his family Fenpark Stables for a number of years, it was a brush with Bell’s Palsy that finally convinced Grassick of the benefits of the technique. “One side of my face went numb on me about five or six years ago. They put me on drugs, but the only thing that really got it back 100% was acupuncture.”

So what exactly is acupuncture, and how does it work? Here comes the science bit—concentrate. Acupuncture works by stimulating the sensory nerves under the skin and muscles. Tiny intradermal needles penetrate the skin just enough to stimulate collagen and elastin production—two of the main structural proteins in the extracellular matrix. During this process, the acupuncturist may feel the needle being gripped by the surrounding tissue —a phenomenon known as ‘needle grasp’. A 2001 study by the University of Vermont College of Medicine further revealed that gently manipulating the needles back and forth causes connective tissues to wind around the needle—think spaghetti twirling around a fork—and sends a signal to the fibroblasts (a type of cell that produces the structural framework for such tissues) to spread and flatten, promoting wound healing.

But wait, there’s more. Under MRI, it has been shown that acupuncture causes the body to produce pain-relieving endorphins. Furthermore, it is believed that acupuncture stimulates the central nervous system. This, in turn, releases chemicals into the muscles, spinal cord and brain. These biochemical changes may further help the body’s healing process.

So what’s not to like? According to the British-based acupuncturist, Dietrich Graf von Schweinitz, the scientific benefits of acupuncture have been lost in translation. ‘The trouble with acupuncture is that it has a messy historical baggage’, explains Graf von Schweinitz, ‘that led the Western world to believe that this was metaphysical, spiritual, “barefoot doctor’ territory”’. ‘Qi’ (pronounced “chee”) may be best known as the last refuge of a scoundrel in Scrabble, but in traditional Chinese medicine, the concept of qi refers to the vital life force of any living being. Traditional Chinese medicine practitioners believe the human body has more than 2,000 acupuncture points connected by pathways, or meridians. These pathways create an energy flow—qi—through the body which is responsible for overall health. Disruption of this energy flow can, they believe, cause disease. Applying acupuncture to certain points is thought to improve the flow of qi, thereby improving health. Although in this sense, qi is a pseudoscientific, unverified concept; this linguistic quirk has meant that medical science has been slow to embrace the very real physiological benefits of acupuncture. ‘The ability of neuroscience to unravel more and more of acupuncture physiology is becoming quite staggering’, says Graf von Schweinitz.

A softly spoken American, full of German genes whose accent betrays only the slightest hint of a southern drawl, Graf von Schweinitz was an equine vet for 30 years until he sold his practice to focus on animal acupuncture. ‘I grew up on a farm in Georgia. My parents both came from rural farming backgrounds. So I was around horses all my life. I actually had my first taste of acupuncture at vet school. In my final year there was an acupuncture study going on in the clinics on horses with chronic laminitis or chronic navicular’. Like Grassick, he has personally experienced the benefits of the technique. ‘In my first job as a vet, I got kicked and was treated by a client who was an acupressurist [a close cousin of acupuncture that involves pressing the fingers into key points around the body to stimulate pain relief and muscle relaxation]. The result in terms of pain control was so bizarre and staggering I just thought, “I’ve got to know more about this”, and started my mission’.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

What does the future hold for Maisons-Laffitte racecourse and training centre?

By Katherine Ford

A visitor arriving at Maisons-Laffitte from Paris is greeted as he crosses the bridge over the Seine by a spectacular view of the town’s 15th century baroque chateau. Signage announces arrival in ‘Maisons-Laffitte, Cité du Cheval’.

The racecourse is currently inactive, but the town still revolves very much around the horse, of which approximately 1,000—half of them racehorses—are stabled in the wooded parkland. Supporters of the racecourse hope that a project will be validated to see the track reopen as soon as 2023, while the training community is revitalised following a 1.5 million Euro investment in facilities, and the team is keen to attract new professionals.

France Galop CEO Oivier Delloye explains, ‘The situations with the racecourse and the training centre are two separate subjects. France Galop is focused upon ensuring continuity for the training centre. We have not closed the door to the possibility of racing returning to Maisons-Laffitte, but if this does happen, it will not be organised by France Galop.

‘There is no racing currently planned for Maisons-Laffitte, and none for next year or in the future unless new elements enter the picture. France Galop is working in partnership with the town council because if there is to be a future for the track, it will certainly involve both parties; and the mayor is very keen for the racecourse to re-open. The idea is to seek a new economic model to make use of the buildings and facilities and therefore finance their upkeep, while France Galop would contribute the prize money and a share of the maintenance costs. This is the model used for provincial racecourses in France, and the system works; however, the costs involved in Maisons-Laffitte are higher than at the country tracks. It is important that any racing at Maisons-Laffitte in the future be organised to a high standard in accordance with the track’s status as a Parisian and premium track.

‘Earlier this year, France Galop published a call for expressions of interest and will analyse which projects could be compatible with a commercial exploitation of the racecourse and buildings, in conjunction with the organization of racing. We have received a number of dossiers including some quite creative concepts—from varying profiles of operators to envisaging different ways of promoting the site, which is recognised as being exceptional. The responses are a mixed bag with some quite structured and some more exotic ideas. We hope to be able to select one or two projects to work on a viable business plan. France Galop will not validate any project unless we are certain of its financial sustainability as the last thing we want is for the racecourse to open and then close again shortly after, or for the new operator to lose money and call in the racing authorities to help out. The whole process will be carried out in full consultation with the town of Maisons-Laffitte and in a best-case scenario, racing could return in 2023’.

Ironically, when the racecourse was closed by France Galop to reduce expenditure, the French racing authority announced an ambitious investment programme of 1.5€ million to modernise and improve the town’s racehorse training facilities. Olivier Delloye is pleased with the results: ‘I visited Maisons-Laffitte last week and found that there was a very positive atmosphere with trainers optimistic about the future. It is clear that the professionals based in Maisons-Laffitte have not lost clients due to the closure of the racecourse, and recent results show that the facilities are perfectly adapted for training all types of horses—from juveniles to top milers and the best steeple-chasers of Auteuil’.

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Nutrition Analysis - Understanding equine feed labelling

By Dr Catherine Dunnett, BSc, PhD, R.Nutr

Understanding a bit about feed labelling and feed manufacturing is worth the drudge, as it can help you make better choices for your horses in training and maybe even save a few pounds or dollars. Whilst the information that a feed manufacturer must legally provide can vary from country to country, it is broadly similar. The purpose of feed labelling is primarily to give information about the feed to a potential customer, allowing informed choices to be made. However, it also provides a measure against which legislators and their gatekeepers can ensure feed manufacturing is consistent and that the feed is not being misrepresented or miss-sold.

The on-bag information is most often separated into what’s known as the statutory statement (or the legally required information) and then other useful information which features outside of the statutory statement. The statutory information can be found in a discrete section of the printed bag, or it could be located on a separate ticket, stitched into the bag closure. Whichever is the case, this is the information legally required by the country’s legislators and which the feed manufacturer is legally bound to adhere to. Typically, the information required within the statutory statement includes for example:

Name, address and contact details of the company responsible for marketing and sale of the feed.

The purpose of the feed, for example for pre-training or racing.

Reference to where the feed has been manufactured. Some companies do not have their own manufacturing facility and will use a contract manufacturer. In the UK, a feed mill manufacturing feed must be registered and on the UK list of approved feed business establishments and there is a number, colloquially known as a GB number, which refers to the feed mill’s registration. A useful snippet is that if this GB number changes on pack, this may mean that the manufacturer has switched to a different mill.

A list of ingredients in the feed in order of inclusion. The first ingredient will have the highest level of inclusion and the last being the least level.

A declaration of analysis, which is used to describe the nutritional characteristics of the feed is quite limited in what can legally be declared. There is a predefined legally binding list of analytes that must be declared in this section, which depends on the type of feed. For example, this might include percentage protein, oil, crude fibre, ash, as well as the level of added additives such as copper, vitamins A, D and E, as well as any live microbiological ingredients, or preservatives, binders etc. In addition, the analysis must be carried out using specific laboratory methodologies set out in the legislation. Feed manufacturers are allowed some tolerance on analysis, or limits of variation around their declaration to account for variation in sampling and manufacturing as well as the analytical variation itself and this can be as high as 10-20% in some instances for example.

The level and source of additives. For example, added copper must be declared and the level (mg/kg) and source (copper sulphate or if as a chelate, copper chelate of amino acid hydrate) stated.

Any additives (i.e., ingredients that don’t contribute to the nutritional value of the feed) can only be used if they appear on an authorised list of additives—meaning they have passed scrutiny for safety and efficacy. This list of additives pre-Brexit was maintained by the EU and since Brexit, whilst we can theoretically modify on our own terms, the reality is that we have largely adopted the EU list.

There is a lot of useful information that is not legally allowed within the statutory statement that you will often find on a separate section of the bag, or indeed on a company website. For example, other analyses such as percentage of starch and sugar are often useful when choosing an appropriate feed and an estimate of the level of digestible energy (DE MJ/kg) is also helpful. Feeding guides also generally appear outside the statutory statement and can be quite useful. Whilst I am a firm believer in looking at the horse to help set the required amount of feed, feeding guides do give vital information, particularly about the likely minimum amount of this feed required to deliver a suitable level of vitamins and minerals.

When being first really counts…

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

TopSpec Trainer of the Quarter - Richard Phillips

Britain's first ever National Racehorse Week will take place 12-19 September this year, thanks to the brainchild of Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire trainer, Richard Phillips. When fan pressure led to singer Taylor Swift withdrawing from performing at the Melbourne Cup, Phillips became aware how little people know about racing. ‘If they knew more about it, they would be more comfortable about racing’, he says.

Phillips has been training since 1993, enjoying success with star chasers Time Won’t Wait, Gnome’s Tycoon and Noble Lord, while La Landiere provided his first Cheltenham Festival winner. He has also won awards for his charity work, including the 2021 Community Award at the Godolphin Stud and Stable Staff Awards, the 2014 Voluntary Award at the Animal Health Trust Awards and the 2011 Pride Of Racing Award from Racing Welfare.

‘I am delighted to see the idea of National Racehorse Week spring into life. It is a fantastic opportunity for our owners, staff, trainers and jockeys to come together for a common love of the racehorse. Racing can sometimes be divided, but the one thing we all agree on is our love of the horse. National Racehorse Week will be our chance to show the public and policy makers that racing has absolutely nothing to hide. We have a great story to tell, so let's get it out there and tell it’.

National Racehorse Week has gathered momentum and support from across the racing industry and is funded by the Racing Foundation, The Sir Peter O'Sullevan Charitable Trust and Great British Racing, in partnership with the National Trainers Federation. It is also the first public engagement of the Horse Welfare Board's Equine Welfare Communications Strategy, funded by the HBLB. Phillips is particularly keen to see MPs involved and visiting their local yards. ‘If racing is then discussed, they will be in a position to know more about it’.

As he points out, you never know who might walk into your yard and the influence that may have on them in the future. ‘The public sometimes thinks racing and racehorse ownership is not accessible, but it is and this is our opportunity to show that. So many of us do so much every day and put the health of our horses before our own. This is our chance to engage with local people, invite them into our yard to meet our staff and get into conversation with them’.

Rupert Arnold, Chief Executive of the National Trainers Federation, is equally enthusiastic. ‘There has been overwhelming and enthusiastic support from trainers. Everyone wants a chance to show their respect for the racehorses to whom they give such exceptional care. I am confident that trainers and their staff, who forge such a close bond with their horses, will grasp the opportunity provided by National Racehorse Week’.

It's not too great a leap of imagination to see National Racehorse Week becoming International Racehorse Week, or at the very least European Racehorse Week in years to come. It is a concept easily adopted by other countries and could work in tandem with existing stallion trail weekends, incorporating every aspect of the thoroughbred’s life— ‘from cradle to grave, a life well lived’, as Phillips says.

‘It’s everybody’s duty to do something and it should be enjoyable, not a chore. We can show people how much we do for horses and how much they do for us. Celebrating the racehorse benefits everyone’.

If you are a trainer and interested in finding out more information please contact Harriet Rochester, harriet@nationalracehorseweek.com

To register visit www.nationalracehorseweek.uk

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Can we use biomarkers to predict catastrophic racing injuries in thoroughbreds?

Promising developments in quest to prevent catastrophic racehorse injuries

University of Kentucky study shows association between mRNA biomarkers and catastrophic injuries in Thoroughbred racehorses—a positive step forward in the development of a pre-race screening tool.

By Holly Weimers

Catastrophic injuries in Thoroughbred racehorses is a top-of-mind concern for the global racing industry and its fans. That sentiment is shared by researchers at the University of Kentucky and their collaborators, who are working to learn more about changes happening at a cellular level that might indicate an injury is lurking before it becomes career or life ending.

Could it be possible to identify an early marker or signal in horses at risk of catastrophic injury, allowing for intervention before those injuries happen? And, if so, might this type of detection system be one that could be implemented cost effectively on a large scale?

According to Allen Page, DVM, PhD, staff scientist and veterinarian at UK’s Gluck Equine Research Center, the short answer to both questions is that it looks promising.

To date, attempts to identify useful biomarkers for early injury detection have been largely unsuccessful. However, the use of a different biomarker technology, which quantifies messenger RNA (mRNA), was able to identify 76% of those horses at risk for a catastrophic injury.

An abstract of this research was recently presented at the American Association of Equine Practitioners’ annual meeting in December 2020 and the full study published January 12 in the Equine Veterinary Journal (https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/20423306). In this initial research—which looked at 21 different mRNA markers selected for their roles in encoding proteins associated with inflammation, bone repair and remodeling, tissue repair and general response to injury—three markers showed a large difference in mRNA levels between injured and non-injured horses.

For almost four years, Page and his University of Kentucky colleagues have been analyzing blood samples from almost 700 Thoroughbred racehorses. The samples, collected by participating racing jurisdictions from across the United States, have come from both catastrophically injured and non-injured horses in a quest to better understand changes that might be happening at the mRNA level and if there are any red flags which consistently differentiate horses that suffer a catastrophic injury.

According to Page, the ultimate hope is to develop a screening tool that can be used pre-race to identify horses at increased risk for injury. The results of this study, which was entirely funded by the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission’s Equine Drug Research Council, suggest that analysis of messenger RNA expression could be an economical, effective and non-invasive way to identify individual racehorses at risk for catastrophic injury.

Joining Page in the research from UK’s Gluck Center are Emma Adam, BVetMed, PhD, DACVIM, DACVS, assistant professor, research and industry liaison, and David Horohov, PhD, chair of the Department of Veterinary Science, director of the Gluck Center and Jes E. and Clementine M. Schlaikjer Endowed Chair.

Previous research has shown that many catastrophic injuries occur in limbs with underlying and pre-existing damage, leading to the theory that these injuries occur when damage accumulation exceeds the healing capacity of the affected bones over time. Since many of these injuries have underlying damage, it is likely that there are molecular markers of this that can be detected prior to an injury.

The identification of protein biomarkers for these types of injuries has been explored in previous research, albeit with limited success. The focus of this project, measuring messenger RNA, had not yet been explored, however. The overall objective was to determine if horses that had experienced a catastrophic injury during racing would show increased inflammatory mRNA expression at the time of their injury when compared to similar horses who were not injured.

The genetic acronyms: A primer on DNA, RNA, mRNA and PCR

This research leverages advances made in genetics during the last several decades, both in a greater understanding of the field as well as in applying that knowledge to specific issues facing the equine industry, including catastrophic breakdown in racehorses.

The genetic code of life is made up of genes and regulatory elements encoded by DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, which is found in the nucleus of cells in all living organisms. It is arranged in a double helix structure, similar to a twisted ladder. The rungs of that ladder are nucleotide base pairs, and the ordering of those base pairs results in the specific genetic code called a gene. The genetic code in the genes and the DNA tell the body how to make proteins.

RNA (ribonucleic acid) is created by RNA polymerases, which read a section of DNA and convert it into a single strand of RNA in a process called transcription. While all types of RNA are involved in building proteins, mRNA is the one that actually acts as the messenger because it is the one with the instructions for the protein, which is created via a process called translation. In translation, mRNA bonds with a ribosome, which will read the mRNA’s sequence. The ribosome then uses the mRNA sequence as a blueprint in determining which amino acids are needed and in what order. Amino acids function as the building blocks of protein (initially referred to as a polypeptide). Messenger RNA sequences are read as a triplet code where three nucleotides dictate a specific amino acid. After the entire polypeptide chain has been created and released by the ribosome, it will undergo folding based on interactions between the amino acids and become a fully functioning protein.

While looking at inflammation often involves measuring proteins, Page and his collaborators opted to focus on mRNA due to the limited availability of reagents available to measure horse proteins and concerns about how limited the scope of that research focus would be. Focusing on mRNA expression, however, is not without issues.

According to Page, mRNA can be extremely difficult to work with. “A normal blood sample from a horse requires a collection tube that every veterinarian has with them. Unfortunately, we cannot use those tubes because mRNA is rapidly broken down once cells in tubes begin to die. Luckily, there are commercially-available blood tubes that are designed solely for the collection of mRNA,” he said.

“One of the early concerns people had about this project when we talked with them was whether we were going to try to link catastrophic injuries to the presence or absence of certain genes and familial lines. Not only was that not a goal of the study, [but] the samples we obtain make that impossible,” Page said. “Likewise for testing study samples for performance enhancing drugs. The tubes do an excellent job of stabilizing mRNA at the expense of everything else in the blood sample.”

In order to examine mRNA levels, the project relied heavily on the ability to amplify protein-encoding genes using a technique called the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). By using a variety of techniques, samples from the project were first converted back to DNA, which is significantly more stable than mRNA, and then quantified using a specialized machine that is able to determine the relative amount of mRNA initially present in the individual samples. While it is easy to take for granted the abilities of PCR, this Nobel Prize winning discovery has forever changed the face of science and has enabled countless advances in diagnostic testing, including those used in this study.

The research into mRNA biomarkers….

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

Innovation motivates Paul & Oliver Cole - the ‘joint masters’ of Whatcombe

By Alysen Miller

“All happy families are alike,” as the saying goes. When Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy wrote these words in 1877, Queen Victoria was on the throne, Alexander Graham Bell was installing the world's first commercial telephone service in Ontario, Canada, and Silvio had just won the Derby under Fred Archer. But it would be another 143 years before the British Horseracing Authority gave formal recognition to the outsize role of harmonious familial relationships in training racehorses. Now, thanks to a new initiative introduced in 2020, the father-and-son team of Paul and Oliver Cole can finally enjoy equal billing at the top of the training ticket as one of the first partnerships to train under a joint licence in the UK.

It’s a formula that paid immediate dividends as the Coles became the first joint-licence holders to register a win in the UK when the striking grey Valpolicella vanquished her rivals on her debut in June 2020. They followed that up a fortnight later with a winner at Royal Ascot, courtesy of stable stalwart Highland Chief. They also enjoyed handicap success in the Cambridgeshire—traditionally one of the most competitive handicaps of the year—with Majestic Dawn. “The most exciting thing was getting that first winner,” says Oliver Cole, speaking from the family’s Oxfordshire base. “I like to point out that it was a very old owner, Christopher Wright, who happened to be the owner that day. He’s been a great friend and was very supportive of me taking up the joint licence.”

The move by the BHA to accept joint licence applications, mirroring a successful scheme introduced in Australia several years ago, can be seen as part of a gradual breaking down of the barriers to entry to a career that has often been perceived as the preserve of a handful of a select few, often independently wealthy individuals.

“First of all, women couldn’t have a licence. And then you couldn’t have a joint licence. All sorts of restrictions have eased off,” says Cole père. Paul Cole is, of course, one of Britain’s most successful trainers, with multiple Classic and Royal Ascot winners to his name. For his son Oliver, the fruits of this success meant growing up within the rarefied atmosphere of a top-class racing operation. “My earliest memories are from eight upwards. I was spoiled in that Dad was quite successful at that stage; and for the next 15 to 20 years, he was top of his game. It was great fun. There was a lot of action—a great atmosphere.”

“It’s a glamorous business and the people in it are glamourous,” says Paul, modestly. “They’re just looking for a little bit more out of life than a lot of other people are. It’s exciting.” Mingling with owners and going on international trips was part and parcel of this upbringing (missing school to attend the Melbourne Cup was a particular highlight). So was it any surprise that Oliver chose to follow in his father’s footsteps? “What else would I do?” he shrugs. “That was the thing I was interested in. The thrill and the buzz are huge.”

“It’s a natural progression,” agrees Paul. “Some people might want to be a surgeon, or a pilot, or something like that. But if you’ve got a father that’s already got a set-up, you’re more likely to follow your family into what you know. You’ve already got all the connections in the business. And connections are important.”

Oliver is Paul’s middle son. The eldest, Alexander, initially showed no interest in racing but now manages Jim and Fitri Hay’s racing operations. The youngest, Mark, is a gamer. But it was Oliver who always seemed destined to follow his father into the game.

It’s certainly not hard to understand the lure of the training life for Cole, particularly on a crisp morning in March when the spring sun is stippling the trees, and every blade of grass on their 450-acre property seems bathed in a vernal glow. From this base at the historic Whatcombe estate, nestled in the idyllic Oxfordshire countryside and criss-crossed with private gallops in a variety of surfaces, Paul and Oliver currently oversee a boutique selection of some 40-50 racehorses for a number of high-profile owners, although there is stabling for up to 120. The property has been in the family since 1986, having previously been in the hands of fellow Classic-winning trainers Dick Dawson and Arthur Budgett. If one looks with careful eyes as the sun rises over the Lambourn Valley below, one can almost imagine that little has changed since the Late Roman period, when the land was cultivated for farming. If this ancient history feels close to the surface, signs of the more recent past are also in evidence: Visitors to the yard are greeted by a statue of Snurge, the first horse to win more than £1 million in prize money; while the stabling is presided over by the great Generous—the last of six Derby winners to be sent out by Paul in 1991.

Such a lifestyle was never a given. “I started with nothing,” explains Paul. “Which is not a disadvantage. It’s an advantage. It instils in you that you want to get on in life, and you know how hard it is to get on, and therefore you make just that bit more effort all the time.” It was a desire to provide for his future family that inspired Paul’s single-minded focus in the early years of his career. “If you want to get married and have children, and give the children holidays, and perhaps send them to school, it takes a long time to get your feet on the ground. But it’s something that you know you have to do. I was brought up with the normal insecurities that families have. I like to think I brought my children up with total security. They never needed to worry about where the next meal was coming from. And now, as you can see, we’ve got a wonderful training establishment. It would be difficult to better it.”

Oliver is the first to admit that he is lucky. But he is certainly not alone. The reality is that without family backing, the potential avenues for younger trainers coming into the sport would be considerably fewer. Paul rejects the idea that only those born into racing families have a pathway to a career in training: “There’s no set route to come in. Mick Channon made a few quid playing football—not as much as they make now! So he started [via] that route. People come in from all sorts of different ways. You’ve got to want to do it, of course.” However, he acknowledges the advantages inherent in having a Classic-winning trainer for a father: “If Oliver wanted to go training, he’s got to start from scratch somewhere,” explains Paul. “That’s another yard, accommodation, gallops. There are lots of worries, lots of snags, lots of hurdles. This way, he hasn’t got to get out and prove himself or be compared with me.”

“I think it’s very difficult for some of these young people,” agrees Oliver. “It’s not just the training. The pressures that go with it must be immense. One of the best things about working together is that I’ve got someone to fall back on in case the pressures get too much.”

In many ways, the introduction of joint licensing has merely formalised a practice that has been in existence for as long as racehorses have been trained, whereby sons and, especially, wives serve as de facto co-trainers to their parents or spouses, though often with little or no recognition. Tellingly, among the first to snap up the new joint licence, along with the Coles, were Simon Crisford and his son Ed, and husband-and-wife team Daniel and Claire Kübler, while five-time champion trainer John Gosden and his son Thady are expecting the ink be dry on their new, joint licence in time for the start of season. . “It did need recognising that there are other people seriously involved in the success [of a training yard], says Paul.”

“My mother is a big help around here,” acknowledges Oliver, as the family matriarch wrangles his two daughters in the next room.

Was that the motivation for taking out a joint licence? “You can’t carry on being an assistant forever,” explains Oliver. “You’ve got to make a name for yourself and if it happens that, in the future, I have to go out on my own one day, people will know that I’ve done it.”

Adding Oliver’s name to the licence has also allowed the Coles to expand their pool of potential owners. “Lots of young people wouldn’t want to have a horse with me, but they want to have a horse with Oliver,” says Paul. Of particular benefit during lockdown has been Oliver’s innate generational facility with social media. Owners who have not been able to visit their horses have been provided with GoPro footage of their gallops once a week, shot from a moving quad bike by Oliver. “I think one of the biggest positives from lockdown is that we had a lot of time to work out the GoPro stuff,” he says. He has also invested in a drone in order to shoot sweeping, Francis Ford Coppola-esque aerials of the property, which he proudly shows off on his phone.

Another consequence of lockdown for yards up and down the country is that the stable staff have had to form their own support bubble. Many of them have not seen their families for the best part of a year. How do the Coles keep morale up? “We have a great community of staff here. They tend to stay here for quite a while, and I suppose it’s just a question of keeping them happy. We all like the ethos of a fun place with happy horses,” says Oliver. “And we are a smaller yard, which helps. We have some great people out there, some quite funny ones. They’re friends. You go out there and you can have a laugh. We have a WhatsApp group that all the staff are on and we always talk to each other on that, whether it’s ‘Well done with the winners,’ or, ‘Amelia, you rode really well this morning.’ It’s a really good tool.

Spring is the time for making plans. As the Coles look ahead to the coming season and beyond, they both agree the main effort is to ensure that the business will continue to provide for the next generation. “We’ve just got to get through the next couple of years before we make any big decisions, but our main aim is to fill the yard,” says Oliver.

“This is a big place to run. And if you haven’t got a certain amount of horses, it’s quite a struggle,” agrees Paul. “There’s a lot of finance that goes behind keeping it going. You’ve got to think about that as well. We have diversified a little bit.” (In addition to the main yard, there is a stud division and some rental properties.)

For the time being, the two seem more than happy to continue to work together as a team, with no signs of handing over the reins in prospect just yet. “We got off to an amazing start last year. We were lucky with some very good horses, and long may it continue,” says Oliver.

At this, Paul sits back in his chair and permits himself a satisfied smile. “Despite the hard work and uncertainty, the first 20 years of my career and life were fantastic. Nice people, nice places, nice things. The owners were nice, the horses worked out. So no complaints!” He grins. “Everything’s gone slightly to plan.”

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

TopSpec Trainer of the Quarter - Henry de Bromhead

By Lissa Oliver

At what could be described as the only Irish race meeting held in Britain, where 23 of the 28 Cheltenham Festival races fell to Irish trainers, one Irish trainer in particular led the way. County Waterford-based Henry de Bromhead became the first trainer to achieve the historic feat of winning the Champion Hurdle, Queen Mother Champion Chase and the Gold Cup in the same year.

Add to those the Triumph Hurdle, Mares’ Novices’ Hurdle and the Ballymore Novices’ Hurdle, and it’s little wonder de Bromhead is now looking forward to ‘catching his breath’ while quarantining back home in Ireland.

The amazing week began for the Knockeen team on day one of the Festival, when Honeysuckle powered away under Rachael Blackmore to land the Unibet Champion Hurdle. De Bromhead says of the mare, ‘She’s pretty laid back. She’s really straightforward; she likes her routine, and she’s lovely to have around the place.’

Having watched her success from the track, de Bromhead claimed it as his lucky spot and so it proved—cheering home two more winners on the Wednesday that Bob Olinger got the day’s Gr1 tally started in the Ballymore Novices’ Hurdle, under jockey of the moment Rachael Blackmore. Then de Bromhead became the first trainer to send out a mare to win the Betway Queen Mother Champion Chase, with Put The Kettle On, under Aidan Coleman.

‘We are very lucky to have good mares like them,’ de Bromhead says, ‘and getting tremendous support from our owners. I thought she had a chance, but on ratings I thought she might struggle a bit; but I hoped she would have a squeak.’

The fairer sex again came up trumps for de Bromhead on the Thursday, Telmesomethinggirl, Rachael Blackmore up, leading home stablemate Magic Daze in the Grade 2 Mares’ Novices' Hurdle to give the stable a one-two. De Bromhead said on the day, ‘I’m delighted for Rachael. She is such a good rider and an ultimate professional, and she is brilliant to work with. She earns everything she gets.’

With the week just getting better and better, Quilixios became the fifth winner for the Knockeen team and the fourth Gr1 winner in the JCB Triumph Hurdle, again under Blackmore. ‘He jumped well and did everything right, de Bromhead enthused. ‘I'm delighted for the Thompsons and Cheveley Park—they're great supporters of ours. Rachael was brilliant on him and all credit to Gordon Elliott and his team—the horse looked amazing coming down to us, and we've done very little. It's more down to them than us. He's just a lovely horse to do anything with. He'll be a lovely chaser in time, I'd say.’

Then came the grand finale—the WellChild Cheltenham Gold Cup, and another de Bromhead one-two. Minella Indo and young Jack Kennedy led home stablemate A Plus Tard and to complete an historic hat-trick. ‘It's massive,’ de Bromhead told the press. ‘I can't tell you what it means to win it, or just to win any of these races. I feel like I'm going to wake up and it will be Monday evening! To do this is a credit to everyone that's working with us; we couldn't do any of it without our clients supporting us. They give us the opportunity to buy these good horses, and I just feel extremely lucky.

‘We felt we had the team exactly where we wanted them heading over to Cheltenham, but I've thought that in other years, too, when we haven't done so well. I wasn't confident about any of them winning. They all seemed okay and happy in themselves, and I was just hoping that they would be able to do themselves justice.

‘The whole week was just surreal from start to finish, from Honeysuckle to the Gold Cup and everything in between. It's magic, and I don't think it's going to sink in fully for quite some time. It's the stuff you dream about.’

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

Why are gastric ulcers still a significant concern for horses in training?

By Catherine Rudenko

With the advances in scoping and increased awareness of gastric ulcers, along with the high prevalence found in horses in training, one may wonder, Why is this condition still such a problem? Do we not know enough to prevent this condition from recurring?

The short answer is that much is known, and for certain, there are effective medications and many feeds and supplements designed to manage the condition. The underlying problem is that the factors leading to ulceration, at least the most significant ones, are fundamental to the routine and management of a horse in training. Quite simply, the environment and exercise required are conducive to development of ulcers. Horses in training will always be at risk from this condition, and it is important to manage our expectation of how much influence we can have on ulcers developing, and our ability to prevent recurrence.

Clarifying Gastric Ulceration

Before considering how and why ulcers are a recurrent problem, it is helpful to understand the different types of gastric ulceration as the term most commonly used, Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome (EGUS), is an umbrella term which represents two distinct conditions.

The term EGUS came into use in 1999 and represented ulceration of the two separate locations in the stomach where ulcers are found: the squamous and glandular regions. The two regions are functionally different, and ulceration in either location has different causative factors. This is important when considering what can be managed from a risk point of view at a racing yard. The term EGUS is now split into two categories: Equine Squamous Gastric Disease (ESGD) and Equine Glandular Gastric Disease (EGGD).

ESGD is the most commonly occurring form and the focus of dietary and management interventions. The majority of horses in training have the primary form of ESGD where the stomach functions normally. There is a secondary form that relates to a physical abnormality which causes delayed emptying of the stomach.

The condition ESGD is influenced by the training environment and time spent in training as noted by researchers looking at prevalence of horses out of training compared to those within training. In this case, 37% of untrained thoroughbred racehorses had ESGD and this progressed to 80-100% of horses within two to three months of training. This effect is not unique to thoroughbreds and is seen in other breeds with an ‘active workload’; for example, standardbreds progress from an average of 44% ESGD in the population to 87% when in training. Such research is helpful in understanding two things: firstly, that ulcers in the squamous section can occur outside of training, and that the influence of exercise and dietary changes have a significant effect regardless of breed. Even horses in the leisure category, which are thought of as low risk or at almost no risk at all, can return surprising results in terms of prevalence.

Risk Factors

There are multiple risk factors associated with development of ESGD, some of which are better evidenced than others, and some of which are more influential. These include:

Pasture turnout

Having a diet high in fibre/provision of ‘free choice’ fibre

Choice of alfalfa over other forages

Provision of straw as the only forage source

Restricted access to water

Exceeding 2g of starch per kilogram of body weight

Greater than 6 hours between meals (forage/feed)

Frequency and intensity of exercise

Duration of time spent in a stabled environment combined with exercise

Of these factors, the stabled environment—which influences feeding behaviour—and exercise are the most significant factors. The influence of diet in the unexercised horse can be significant, however once removed from pasture, and a training program is entered into, ulceration will occur as these factors are more dominant. An Australian study of horses in training noted the effect of time spent in training, with an increase in risk factor of 1.7 fold for every week spent in training.

Once in training, there is some debate as to whether provision of pasture, either alone or in company, has a significant effect. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

Inexplicable underperformance: investigate it with the ECG analysis

In association with Arioneo

Providing veterinarians with a real diagnostic challenge, underperformance in the racehorse can be difficult to investigate if the horse’s environment does not benefit from reliable technologies to collect historical data. Indeed, it is difficult to determine the cause of underperformance without almost daily monitoring. The symptoms to be identified are most often subclinical, i.e. they are difficult to detect at rest and during effort. The detection of under-performing horses within the racing industry is a real challenge. Carrying out prevention and detection work could in fact make it possible to avoid serious accidents in training or on the racecourse.

In order to detect the elements influencing the performance of the athletic horse, it is interesting to analyse evolution during an exercise because things that do not occur at rest can appear.

In a series of two articles, we will analyse two cases of underperformance encountered by the leading vet, Dr Emmanuelle van Erck.

In the first case we investigate the loss of performance of a 3-year-old filly. The latter had promising performances during her 2-year-old season and then injured her tendon. The trainer decided to stop her until next season. Once prepared for the return to training, the mare showed good abilities and her return was very satisfying. However, a nosebleed was detected after a small canter. The tracks were not particularly deep and there were no circumstances that could explain this bleeding.

In order to investigate the causes of this bleed, the first step was to analyse the data from the mare when she presented her nose bleed.

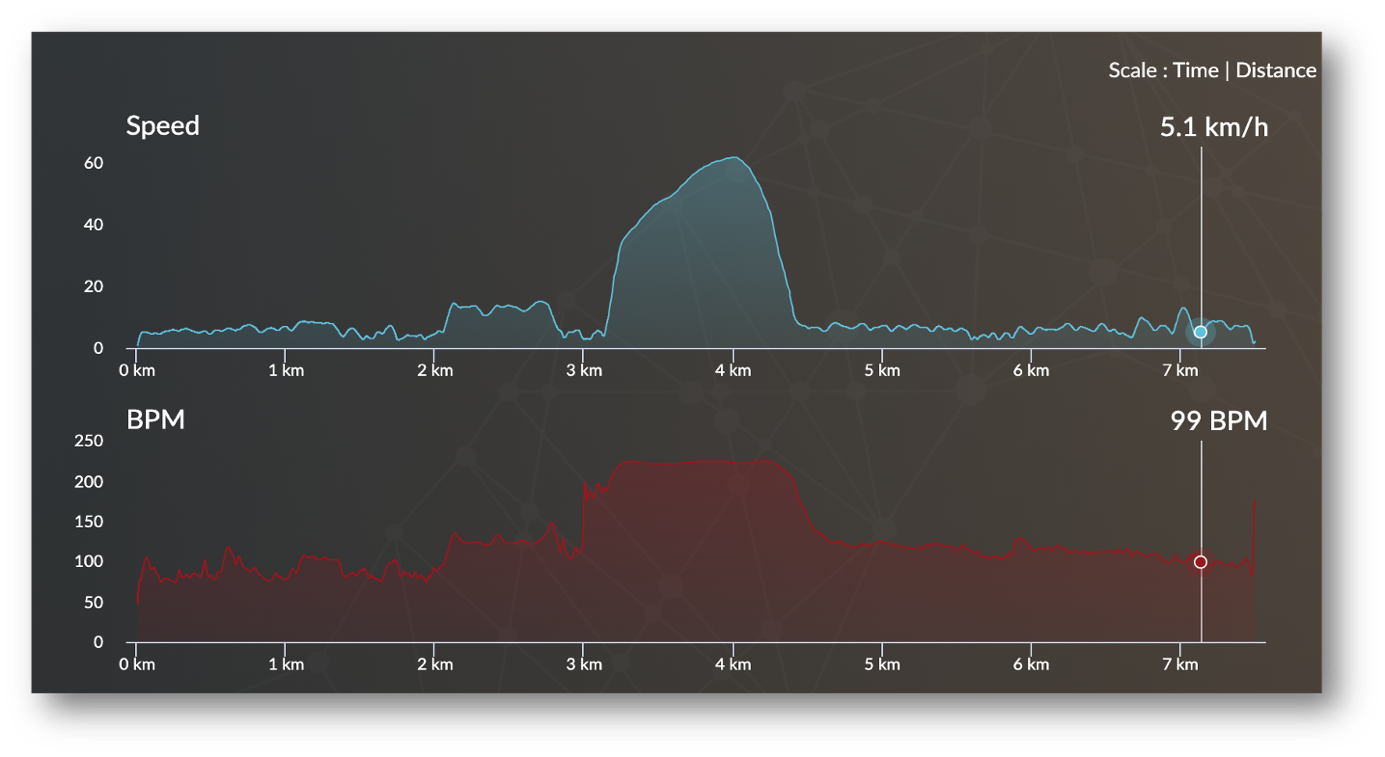

Screenshots of the EQUIMETRE Platform

It can be seen that the speed data are low: the effort does not go beyond 47km/h. The effort was of low intensity, but the heart rate is still very high, up to 217 bpm.

It was necessary to analyse the data from a more sustained training session in order to observe what is happening.

The data is normal: the heart rate changes at the same time as the speed.

The veterinarian decided to compare the horse’s data with those of the other horses, who have done similar work. The data does not show any recovery anomalies, the two curves that are superimposed do not show any significant difference. Her heart rate is a little high after the effort, but nothing catastrophic is observed.

1st conclusion: There is no explanation for the nosebleed in the data.

The veterinarian then decides to look at the ECG of this mare. The latter is pathological and shows 8 superventricular extrasystoles in 1 minute. This is far too frequent, especially in the warm-up and recovery phase.

ECG collected by the EQUIMETRE. Arrows show the arrhythmias.