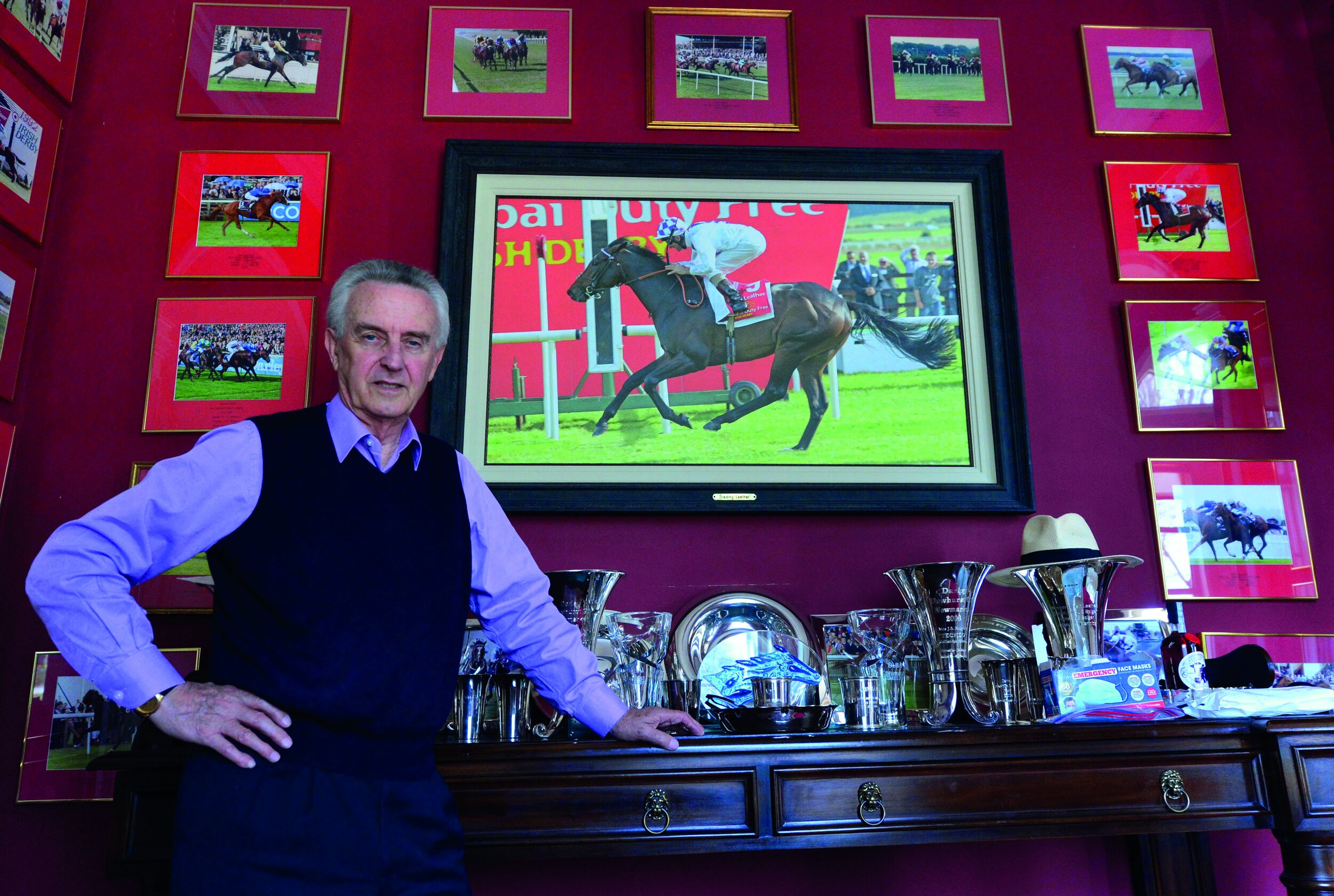

HENRY DE BROMHEAD - "I'M GOING TO TRY TO TRAIN A CLASSIC WINNER ONE DAY."

WORDS: DARAGH Ó CONCHÚIRHenry de Bromhead has had a good day. Another one.

A winner at Thurles is today's bounty. You surmise it could have been better, with two runner-up finishes from his other pair of representatives.

In trademark de Bromhead style, such notions of grandeur are rebuffed. Any visit to the track that includes a smiling debrief and a photo under the No 1 lollipop, is a good one. Especially when Messrs Mullins, Elliott and Cromwell are providing the opposition.

Still, it is reflective of the rich vein of form in which the Waterford trainer's string has been through the autumn and into the beginning of the winter campaign, as well as the seamless transition of Darragh O'Keeffe into the role as Knockeen's No 1 following the retirement in May of the incomparable Rachael Blackmore, that one in three is the least we are expecting.

October 2025 provided de Bromhead with his highest ever monthly tally of winners in Ireland (18) and a notably impressive strike rate (32%). His PB before that in terms of victories was 17 in September 2020 at a clip of 30%, and in terms of strike rate was 31% in November 2024, when he still managed to record 16 winners. There are clearly some strong summer months too, such as the 11 well-earned triumphs recorded in July 2024.

This is not a coincidence. It is, to a considerable degree, as a result of a policy of not going the full 12 rounds with his sport's heavyweights.

The subsequent bounty from such guerilla tactics is not just about short-term gain, however. The strategy's prime benefit is having the horses re-appear fresh and in mint condition after a mid-term break, for when the gloves must come off in the spring, particularly at Cheltenham.

So our expectations are an indication too of de Bromhead's position as one of the greatest to ever condition a national hunt horse, transforming a boutique establishment set up by his father Harry, from whence Fissure Seal won what is now the Pertemps final for a syndicate of dentists in 1993.

He is the only trainer to be victorious in the Gold Cup, Champion Hurdle and Champion Chase in the one week, as achieved when Minella Indo, Honeysuckle and Put The Kettle On prevailed among six festival winners in 2021.

He added the Grand National as Minella Times launched Blackmore into the stratosphere a few weeks later, repeating his Gold Cup feat of saddling the runner-up also. Stupendously, there was another 1-2 when the Gold Cup placings were reversed by A Plus Tard in 2022.

Yet despite having all of Cheltenham's championship races (2 Gold Cups, 2 Champion Hurdles, 4 Champion Chases and a Stayers' Hurdle), the National, a total of 61 Grade 1s and 25 Cheltenham Festival winners on his vaunted CV, he chose to expand into the flat sphere to improve the profitability of his business.

Being Henry de Bromhead, he has proven very astute and adept in this department. In June 2025, he registered his first Royal Ascot success thanks to Ascending and would go on to record his best tally of winners in Ireland, on the level, in the calendar year with 17.

There are six group races on the resumé now, Blackmore highlighting her versatility when steering future Group 2 winner Terms Of Endearment to victory in the Bronte Cup at York in May 2024. But peruse the variety of venues at which those prizes were plundered: Toulouse, Goodwood, York, Sandown and Cork. So imaginative. So smart.

Some might find it incongruous that a man at the very top of his profession has serious concerns about the future of his sport, and industry. But, of course, his voice carries more weight for that.

De Bromhead gets uncharacteristically animated when discussing the funding of horse racing, and speaks about it, mostly uninterrupted, for nearly ten minutes. He is appalled by a model he believes is inimical to the interests of the sport and all who gain a living from it. In particular, he is passionate about the need to cut the umbilical cord between racing and the giant bookmaking corporations and is lobbying to build momentum towards racing creating its own betting company, with a view to becoming self-sustainable. This is something he believes is achievable within 10-15 years of such a venture being set up. More of which, anon.

We have become accustomed to the de Bromhead periodical fecundity, when the ground has yet to get bottomless, his "nicer sort of winter horses" are unleashed and Closutton and Cullentra, in particular, have yet to activate their 'Drag Reduction System. Often, there has been a lull in January and February, and there have been a few years where pundits and punters alike have wondered about the form of the de Bromhead representatives going into March. We know better now.

"It sort of worked for us over the years. We generally aim to have those festival horses ready from October onwards, depending on ground. Horses that prefer nicer ground would be earlier, horses that prefer softer ground would be a little bit later, but we generally aim to have them out by the end of October, November time. And we'd probably go to Christmas with them.

"So I'm never sure then... you could call it a lull. But also, we'd put away a lot of our horses in January with a view to the spring. So it's just worked for us over the years. I suppose you're trying to start a little bit earlier than Willie, for example, because you know, otherwise, you're coming up against all his big guns from now on.

"It's a case of sticking with what has worked before. I suppose we're creatures of habit, a lot of trainers, and that has worked well for us over the years. We'd always be aiming towards Christmas, trying to have two or three runs under their belts and then try and freshen them up before the spring."

It is quite something to be setting new landmarks not long after all the great champions have retired. The Minellas Indo and Times, A Plus Tard, Champion Chase heroine Put The Kettle on and the equine queen of Knockeen, dual Champion Hurdler and four-time Cheltenham victress, Honeysuckle.

But cycles conclude and you plan for the next great challenge, even after you have scaled Everest. Not that you are ever buying a horse with anything more than hope.

"I'm not sure you can plan for a Honeysuckle or Indo, that they were going to go on and do what they were going to do. Put The Kettle On, we bought as a store. We were very lucky that these horses came along. These were horses you dream of having, that you might get one in a lifetime, and they suddenly came within a couple of years of each other.

"We don't restock with as many horses as some of the bigger yards every year. I think it's sort of comparable to football teams with transfer markets. The bigger you are, the more you have to spend, the more new horses coming into your system, and then the more likely you are to come upon these top horses. That's what we're all striving to get.

"With what we have to spend, we wouldn't have as many young horses coming through as some of the big yards. So maybe it's less frequent we're going to come upon them, but we know we have the system. When we get them, we will produce. We'll get the best out of them and hopefully give them every chance to get to those blue riband events.

"Ultimately, when any of us are buying them, none of us actually know. You have your systems that work for you, but no one knows which one is going to be the champion until you get them into your system. We had that period with all those amazing horses that we had, and we've still got some really nice horses and some really nice young ones coming through this year. We hope that we will bring them through to compete in those big races."

He covers the gamut of markets in terms of acquiring French stock, point-to-pointers and stores. Like everyone, he is trying to find value.

"Some of our clients buy their own horses and send them in. Some of them ask us to find horses for them. So we have spotters at the point-to-points that help us source these horses. Gerry Hogan helps us. Alex Elliott has helped us, with plenty of agents that put horses to us or our clients.

"That's the way we buy stores as well, though it's less stores. We have had more luck with form horses, but, we still had a Gold Cup horse as a store, Sizing John. We didn't train him when he won it, but we sourced him as a store and we sourced Sizing Europe as a store, the likes of Special Tiara, Put The Kettle On.

"D'you know what? The more I think of it, they nearly find you, those real ones. But once you have a system that you can produce and nurture them to be that class... once you have that, you've got to stick to that and hope that your policies work."

Sticking to what work does not mean you are not constantly evaluating and re-evaluating.

"If I was to criticise myself, maybe I'm not aggressive enough or proactive enough with my buying policy. I think we've got a good way of sourcing, and it's worked for us very well over the years but maybe I could be more proactive. We've got brilliant clients who support us. We get really nice horses to train and try to get from 150 (rated) to 170, those horses are so hard to find, and they're the ones we all want."

De Bromhead likes the way Knockeen works now, the rhythms. Expanding would change that. It goes back to the reasonable policy of not taking a scalpel to a healthy patient. If it ain't broke, and all that. He is very comfortable with the scale of the operation.

"It means we can be a bit more bespoke to horses and try and suit them, rather than them suiting a system for us. The thing for us is trying to nurture them along. Since I started training, probably one of the main things for me was... it's so hard to get a good horse, when you get a good one, it's trying to get that longevity. And I think we've proven that over the years with the likes of Honeysuckle, Envoi Allen, Bob Olinger, Minella Indo, Sizing Europe. Once you get those good horses, you're trying to maintain them and keep them going at the highest level for as long as you can." It speaks volumes.

There has been one monumental alteration to the landscape though, in the ascension of O'Keeffe to the throne vacated by Blackmore. De Bromhead was well established prior to her arrival at Knockeen - Sizing Europe, Special Tiara, Sizing John, Petit Mouchoir, Identity Thief, Champagne West, Shanahan's Turn and Days Hotel all pre-dated the Killenaule marvel.

But it is inarguable that he rocketed to another level in conjunction with her. They became behemoths, growing together. Blackmore has been the pilot for 31 of his 61 Grade 1s. Andrew Lynch is the next highest provider with seven. She was in the plate for 16 of the 25 Cheltenham triumphs. They were inextricably linked as they soared to the moon.

O'Keeffe had been used regularly since delivering A Plus Tard from the clouds to win the Savills Chase at Christmas in 2020. It was the teenager's first ride in a Grade 1. He scored on Maskada in the Grand Annual a little more than two years later. Right now, the Doneraile native is miles clear of Jack Kennedy and Paul Townend in the race to add the champion jockey title to his conditional crown, though the latter pair are now in full cry with their primary employers, Elliott and Mullins.

"That's been really good," de Bromhead concurs. "What we achieved with Rachael was incredible, and she was amazing to work with. And we had some unbelievable years. That's a good point about how we grew with Rachael. Rachael really helped us grow as well. She was incredible, what she brought to the table.

"But Darragh rode A Plus Tard in the Savills Chase and everyone said, 'God, fair play, you're putting up a 19-year- old. I didn't even know he was 19. I had thought he was a lot older, it felt that he was around a lot longer. He's always been working away with us, so I'm delighted to see him taking his opportunities. It's very similar to Rachael. He's a brilliant rider. He's really so clued in. He wants it as much as we do.

"Obviously, there was a window last autumn where Rachael was unfortunate to get that injury (broken neck), and Darragh stepped in and did really well. So it was encouraging to see that, but I didn't know Rachael was going to retire when she did. I had no idea, to be honest, but at least we knew that Darragh had stepped into it for a while and did really well."

He has taken to utilising Billy Lee more in recent years too and it was the Limerick man that was on board when Ascending denied Nurburgring by a neck in the Ascot Stakes last June.

"That was an incredible day for a number of reasons. I always wanted to have a winner at Royal Ascot, so it was brilliant to tick that box. We'd love to train a few more. What made it extra special was getting it for the Joneses, with Chris and Afra there and the boys. That was brilliant. Chris and Afra have always been brilliant supporters of ours. We got a real kick out of that."

Seamie Heffernan was on board Ascending with what we now know was the impossible task of attempting to overcome Ethical Diamond in the Ebor, getting only six pounds from the subsequent Breeders' Cup Turf hero. De Bromhead saddled Magical Zoe to win the valuable prize 12 months previously.

"We went into (flat racing) from a trading perspective. My view is, as a jumps trainer, I don't like to train and trade. In my opinion, they don't really go well, it just doesn't suit me. I like to buy horses for jumps clients independent of us, being from point-to-points or whatever. So I never really wanted to trade jumpers.

"But we have this infrastructure, and we have a great team at home. So I think it was probably about seven or eight years ago that we said we'd just dabble in it and see, and bought a couple of fillies, and they sold really well, and it became a good trade. It started well, so we continued doing it. We got some great trades out of it and we can have a piece of the pie as well in that."

Commerce may have been the motive for dipping the toe into the summer game but the competitive juices are flowing now and a little taste of the big time in that sector has induced the germination of a much greater career goal.

"This year we've had a good enough season. Owner-breeders have sent us some nice horses, and some clients have bought a few nice horses for us as well. So, it's exciting.

"I'm going to try to train a Classic winner one day. "You have to have ambition. It's something we enjoy doing. Some of our clients really enjoy it, some like a bit of both. It's people's hobby but we want to achieve what we can."

The irony, which he acknowledges, is that the international market that has helped him land some lovely touches, has had a direct impact on the NH world, with a significant reduction in flat horses making the transition to the jumps game due, in some part at least, to the phenomenal prize money available in the likes of Hong Kong, Australia, America and the Middle East.

"Oh absolutely. Now, obviously, you'd probably look more for a horse that likes a bit of soft ground off the flat, which mightn't suit these places but yeah, it has. It's definitely made them a lot more expensive. I've never bought many off the flat but it has made it harder."

It is financial reality that has led to this trend. The same financial reality that nudged de Bromhead towards his flat racing sideshow. And the same financial reality that winds him up to 90 when queried on the biggest challenge facing the industry right now.

"It's very simple. It's prize money. I've got a strong view on racing's association with corporate gambling companies. It's not bookmakers anymore. These are massive corporate gambling companies... the days of racing and bookmakers going hand-in- hand, that's completely different now. I think we're used as a shop window for the corporate gambling companies to get people to their sites, to bring them across to their online gaming, which is a far more profitable part of their business than gambling on racing. "I have a fairly radical view. I think we should be going pure Tote, like France, like all the richest racing nations, and I think it's achievable. We'd need more government support than we have at the moment, but I think we could become a self-funding industry within the next 10 to 15 years, like France, like Australia, who actually have allowed the corporates in, and they're already starting to see a fall in their TAB turnover, which is affecting finances.

"So I think it could get worse before it gets better. You listen to the likes of (HKJC CEO Winfried) Engelbrecht-Bresges, and British and Irish racing needs to move more towards pool betting. It's more punter-friendly. Even if you're a winner, you can get on. From what I hear, anyone who's a successful gambler, if you win with these corporates, you get shut down, you're not allowed to bet, which seems so fundamentally wrong to me.

"I think this new form of gambling (online casinos) is going like alcohol and cigarettes. It's getting to be a real taboo, and it's becoming socially and politically unacceptable. And racing is associated with that now."

Which makes it an easy target.

"And yet, you look at the addiction rates. I think you're three or four times more likely to be addicted to online casinos than you are betting on racing. And in racing, it's a skill. I can't see the difference between wagering on racing and wagering on stocks and shares. I actually can't. It's a skill. Some people are better at it than others and these corporate gambling companies won't allow the people that are good at it to wager. It all seems so fundamentally wrong to me.

"It would be a massive change, but I think if the Irish and British racing industry got together and got behind it (it would work). Racing is so popular, it's incredible. We sort of put ourselves down but I'm amazed, day-in, day-out, people that know about me, know what I do, that I didn't think would have had any interest in racing, and it's not from a betting perspective.

"I think we need to improve the engagement. You look at Japan. The whole story of where this horse that you are seeing racing today is told at the racecourses. We need to look at that." He is not talking about the midweek fixtures, when you might not find the worst sinner in attendance.

"You're gonna have to have industry days. They have those in France... but still, I think, the PMU gets something like 800 million, and the Exchequer gets 800 million. And there's something like 13 billion wagered on French racing worldwide, which is similar to Britain and Ireland, and yet they get 800 million to run French racing. Okay, I know it's decreased a tiny bit. But I think as an industry, we have to take ownership of that." He is rolling now.

"These ambassadors for these corporate gambling companies. I don't get that. I just don't get it. It was offered to me a few times, and I thought about it, but I didn't do it and I really wouldn't dream of doing it now. Now I think we should all become ambassadors for our industry, for our sport. And if that's the Tote or pool betting; it may not be the Tote. Something like the World Pool, but obviously for Ireland and Britain."

Self-sustainability should be the goal of administrators and participants alike, and de Bromhead is being proactive in attempting to build support for his idea.

"There's a few of us discussing it. That's the dream. It's going to take a lot of people to pull it together, and mainly the industry and all the stakeholders. That's the reality. This thing we're dependent on, corporate gambling companies, that bookmaker/ racing relationship is gone. They use us as a shop window to get people to convert them to their online casinos, and soon we're gonna not be really much use to them.

"In the previous media rights deal you were paid per race. Now it's a percentage of turnover. So if they don't price up a race, which they didn't at Bath last year, they don't have to pay us, whereas before, they had to pay seven or eight grand for that race. So I just think we need to get away from that."

It's what everyone wants but no one is sure how to achieve it. Yet. "We need more cohesion to achieve it and more industry buy- in to achieve it. But I think if you could point to people that you could be racing for a 30 grand maiden hurdle in time, I think that's massive for the industry and makes it more sound."

It is a credit to him that he is not just exercised by the malaise but offers a possible solution and is attempting to rally people to the cause. And all the while, keeping the home fires burning, as fruitfully as ever before.

Envoi Allen brought his tally of Grade 1s to ten - six under de Bromhead's tutelage - when winning Down Royal's Champion Chase for the third time last month. He clearly doesn't act at Kempton so after a break, will build towards spring and probably the Cheltenham Gold Cup.

Stayers' Hurdle champ, Bob Olinger is another who works back from Cheltenham, and Hiddenvalley Lake, in the same ownership, is a Grade 1 winner in that division too. Meanwhile Quilixios was alongside Marine Nationale when falling at the last in the Champion Chase, a race de Bromhead has won four times. The former Triumph Hurdle winner is back for more.

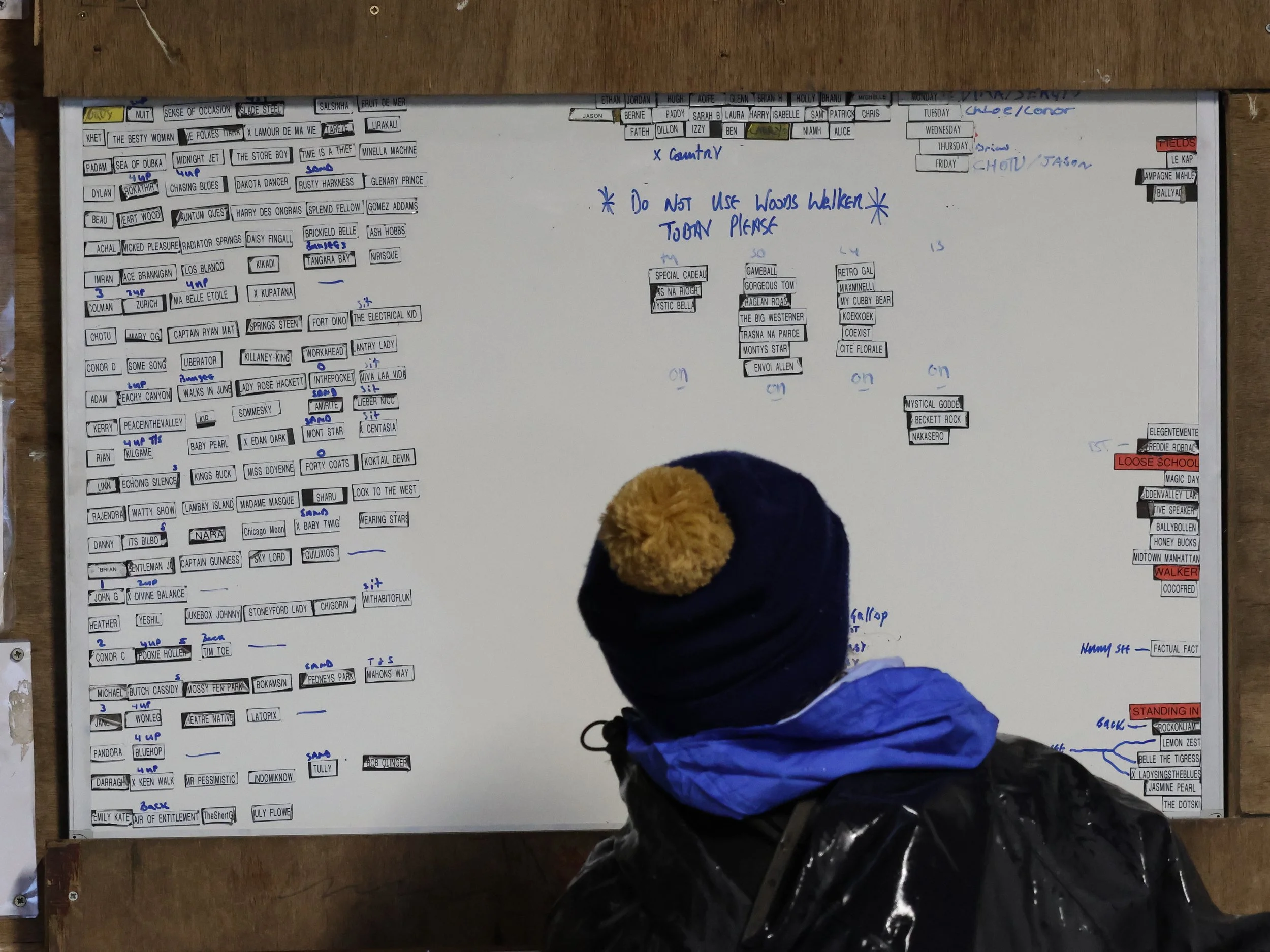

Then you have the raft of younger charges, such as July Flower, The Big Westerner, Forty Coats, Mister Pessimistic, Fruit De Mer, Slade Steel, Workahead, Gameball, Sky Lord, Tim Toe, Koktail Divin and Gomez Addams. And The Short Go and Monty's Star are more established chasers likely to pick up their share of prize money in the coming months. On paper, the succession planning has been shrewdly implemented.

"Obviously, the bubble bursts every now and again. But once you can keep the dream alive with a few nice horses, they'll all find their level and we'll keep trying to bring them through."

A vision for victory - six-time champion trainer Nicky Henderson on his forty-seven seasons at the top of the National Hunt table

Article by Alysen Miller

“Of course, they’d never let me have a driving licence,” chortles Nicky Henderson. We are in his jeep hurtling across the Lambourn Downs on our way to watch first lot get put through their paces. I reach reflexively for my seatbelt. “I drive around here [‘here’ being, naturally, the historic Seven Barrows] but I wouldn't see a car coming until it's 50 yards away. Which is not a very safe way of driving,” he admits.

Henderson suffers from macular degeneration – an eye disease that affects central vision. People with macular degeneration can't see things that are directly in front of them. Henderson started experiencing blurred vision 10 years ago. Since then, his eyesight has become progressively worse. “When you lose those these things gradually, you don't notice it to start with,” he says.

While living with the condition certainly comes with challenges, it cannot be said that Henderson’s failing eyesight has dulled the six-time champion trainer’s enthusiasm for the game. “There are a lot of things I can't do, and there are definitely things that I miss,” he explains. “The worst thing is not being able to see people's faces. I can't really read without putting it in great big letters [on his iPad], and even then it still doesn't work particularly well. I read what I have to read.”

This includes reading the Racing Post cover to cover every day. “Well, the greyhounds get a miss,” he says. “But I don't read a daily newspaper. I’m probably the only person you’ve ever written an article about who will never read it,” he quips. “But I can see horses. That’s the one thing I can see. Once they're out, I know exactly who's who and what’s where. If that was a human, I couldn't tell you who it was if I didn't know them at that distance. But I can see the whole horse.”

There is little that hasn’t already been written about Nicholas John Henderson LVO OBE, obviating the need for him to read my humble contribution to the canon. He is the son of Johnny Henderson, a banker and racehorse owner (not to mention aide-de-camp to Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, whom he tapped to be Nicky’s godfather) who was instrumental in keeping Cheltenham Racecourse out of the clutches of property developers when, in 1963, he and other Jockey Club members formed Racecourse Holdings Trust, a non-profit-making organisation that raised £240,000 (approximately £4.4 million today) to purchase the racecourse and safeguard its future, and that of the Cheltenham Festival.

Henderson père’s name was added to the title of the Grand Annual Handicap Chase in 2005. It had been expected that Henderson fils would follow his father’s well-healed footsteps into pinstripe suited respectability. “And I did, in a roundabout way,” he says. He spent a year in the Sydney offices of aristocratic private stockbroker Cazenove. He had been “mucking about in Western Australia with sheep and cattle and horses” when he was summoned back to London to start his City career. “I didn't like the idea of it, so they came up with a great idea,” he says. “I could go back to Australia and be in their Sydney office, which had two people in it. That was going to suit me an awful lot better than sitting in London. So off I went, back to Australia, until it was eventually time to go back to London and get serious.” He lasted a year and a half. “I just couldn't sit behind a desk and stare at a wall,” he says.

Instead, he became assistant trainer to the legendary Fred Winter. “I was at Fred’s for five years,” he says. “Then it was either a matter of going elsewhere to see if I could learn something else or kicking off [on my own] and seeing what happened.” So the legend goes, in 1978 he was at the pub when he agreed to purchase Windsor House Stables from Roger Charlton. “We just dreamt it up one night. Roger was going to go and be Jeremy Tree's assistant and he said, ‘Well, why don't you buy my place?’” he reminisces. “So he went off to Jeremy’s and I went down the road from Uplands, which was where Fred was. We had about five horses to start with. I hadn’t got a clue what we were doing, but it sort of got off the ground, miraculously.”

Windsor House came with two amenities – an equine swimming pool (something of a novelty at the time) and Head Lad Corky Browne. “Roger said to me, ‘I've got this amazing head lad who and you really want to take him on.’” Corky would become Henderson’s right-hand man and remain an integral part of the team for more than four decades. He retired in 2019. “And then somebody said to me, ‘I've got a really good traveling head lad,’ which was Johnny Worrall,” Henderson continues. “And there was only one other person we needed: Jimmy Nolan, who was used to ride for Fulke Walwyn. So I had the best head lad you could have, the best traveling head lad you could have, and a really good rider in Jimmy.”

The second half of the twentieth century was a golden age for National Hunt trainers in Lambourn. “There was Fred and Fulke, and then Richard Head and Jenny Pitman came along later,” he says. “They were great, legendary, men that you just looked up to and spoke to very quietly, if required to speak. We had such enormous awe and respect for those guys. They were icons. They were gods.”

Now Nicky Henderson is one of those icons. His accolades include nine Champion Hurdles and six Champion Chases. Amongst currently active trainers only Willie Mullins has won more races at the Cheltenham Festival than Henderson, making him Britain’s most successful trainer at the Festival. His encyclopaedic list of winners runs from Altior to Zongalero, the latter of whom was second in the Grand National in Henderson’s first year as a trainer. “A horse like him comes along and you nearly win the Grand National in your first year… Well, that would have been daft,” says Henderson. “Fred Winter did it, incidentally. But to come second in the Grand National in our first ever year? That’s how lucky you can be,” he says self-deprecatingly.

I put it to him that Napoleon famously said he’d rather have lucky generals than good ones. “I don't think Monty would appreciate that!” Henderson laughs. Monty – Field Marshal Montgomery – and Henderson maintained a correspondence throughout the general’s life. “He was a fascinating man, and we got on very well. We had some very funny times together. We did write to each other a lot. But if I had said, ‘God, you were lucky,’ I think he'd think was a bit more skill in it than that!”

Zongalero’s second place in the 1979 Grand National – beaten by two lengths by Rubstic, the smallest horse in the race – has yet to be bettered by a Seven Barrows runner. But Henderson remains grateful for his first flag bearer. “He was the first horse I was ever asked to train,” he remembers. “He was quite a well-known horse. Tom Jones – who trained him – was becoming more and more of a flat trainer, so he was giving up the jumpers. He had this great big thing and he thought it was better for him to go somewhere else and, blow me down, I got this amazing letter one day – before we'd even opened the yard – saying, ‘I've got this horse. I'd like you to train it for me.’ I thought he was mad. Anyway, Zongalero came along with a few others, and, you know, the bits and pieces suddenly turned up and it sort of got the ball rolling. But I see him as the first great horse.”

If Zongalero was the first great horse, he certainly was not the last. Henderson’s current stable stars include Jonbon, Constitution Hill, Sir Gino, Lulamba and Jango Baie. “Those top horses are as good a string as anyone could have,” says Henderson. “They're all genuine Group 1 horses, the top of their categories.” But after four decades at the top of the game, does Henderson ever worry about the Young Turks snapping at his heels? “There are a lot of very good young trainers coming through, particularly National Hunt,” he says. “I think we're probably all competitive. I know I am. You wouldn't do this if you didn’t want to win. There's no point in going out there thinking, ‘I’m just going to do this for fun.’”

So what’s the secret to his longevity? “There are two things you need: good horses and good people. You've got to have an awful lot of good people,” he says firmly. “That is essential.” He is quick to pay credit to Charlie Morlock – whom he describes in Montgomerian terms as his aide-de-camp – and Assistant Trainer George Daly as well as his wife, Sophie. “I know you're trying to write about me,” he says, breaking the fourth wall. “But it's not about me. Gosh, no. It's the whole operation.

“We were talking about eyes,” he continues. “I have actually got three different pairs of eyes,” he says, “in Charlie, George and Sophie. I would be in serious trouble without them. They're vital.” Morlock previously assisted Henderson for 10 years before striking off to train in his own name. “And he did fine,” says Nicky. “But it was a mutual idea that we get back together again. And he's been here for God knows how long this time. George is my assistant trainer, he's Charlie's aide-de-camp. We just do everything together.” It all sounds a bit like being a field marshal, I suggest. “I suppose so,” he says. “It has to be reasonably regimented with that number of people and that number of horses. We pull out at 7.30am every single morning, 365 days of the year, except Sundays.” Every evening Henderson goes round half the yard. “I'm feeling their legs, looking at them. ‘You've got lighter,’ ‘You’ve put weight on,’ ‘I don't like your leg,’ ‘You look well,’ ‘You look shocking.’ Not many yards would do evening stables like we do here. It's still very old fashioned.”

Despite his insistence on his antiquity, Henderson is not immune to the proliferation of technology that has swept through the racing industry in the past decade. “It's got its advantages,” he admits. “We use heart rate monitors. There is blood testing and scoping, all the modern technology. It filters through.” But there are limits to his embrace of technology: “It’s not like I'm still going to school like these guys are, or have been over to Australia and America to learn all the new technology they have over there that you can bring to this country. We’ll pick it up somewhere along the line,” he says. Henderson has also revealed an unexpected gift for social media. (“I hate it,” he says.) And yet few among us will ever look at a photo of a printed page of Calibri the same way again.

In the course of researching this profile I managed to turn up a news report from 1979 (written by one Brough Scott) that describes Henderson’s training as showing “a mastery and skill beyond his years.” It is submitted that, more than four decades later, the reverse is true: the septuagenarian Henderson trains with an energy and enthusiasm that belies his age. As Henderson looks ahead to yet another National Hunt season – his 47th – there is one prize that eludes him: the English Grand National. “We've won all the Champion Chases and Champion Hurdles and Gold Cups, a couple of King Georges. I think most of them have got ticks by them,” he says. “But a Grand National is the obvious thing [that’s missing].

“Embarrassingly, there are no Grand Nationals [in his trophy cabinet] whatsoever. Except for the American, which I really can't count because it's a two-and-a-half-mile hurdle race.” The obvious candidate to capture Henderson’s white whale is Hyland. “He ran in it last year and I think he would have probably grown up from the experience. And I would think it's probably on his agenda this season.” One can’t help but hope that Henderson will get to see a Seven Barrows runner crossing the winning post in first place at Aintree, even if he has to watch it on TV. “One thing I don't see particularly well is on a racecourse. I can't see even with binoculars,” he says.

With Henderson’s eyesight failing it’s tempting to think of Ludwig van Beethoven, who produced arguably his greatest works when completely deaf. Even as he rages against the dying of the light, Henderson has no intention of calling time on his training career. “I'm first to admit it, I've been very, very lucky. But we've done our best to make the most of it, and it's been fun. And it’s still fun. And I intend to go on having fun.”

Mario Baratti - how he’s created a classic winning stable in the heart of Chantilly

Mario Baratti is sitting behind the desk in the spacious office of his stable off the main avenue leading into Chantilly, munching a croissant in between second and third lots. I decline his offer of breakfast, and we quickly agree to communicate in French and to use the friendly “tu” form instead of the more formal “vous”.

Above the trainer’s right shoulder, a large watercolour depicts a scene of Royal Ascot, “it was a wedding gift and it was too big for the house so it has a perfect place here… The colours are beautiful and it’s a wonderful source of inspiration!” The walls are also adorned with photos and a framed front page of French racing daily Paris-Turf showing Baratti’s two Classic winners to date, Angers who lifted the German 2000 Guineas at Cologne in 2023 and Metropolitan who propelled his handler onto the big stage with a first Group 1 victory in the Poule d’Essai des Poulains a year later. There is plenty of space left for memorabilia which seems sure to come to celebrate wins in the future.

Born and raised in Brescia in North-West Italy near Lake Garda, Mario Baratti has a slightly different profile from several of his compatriots who are now successfully operating in Britain and France. The 35-year-old does not hail from a big racing family and he has little experience of training in his native country.

He explains, “My father was a great sportsman and was good at a lot of sports. Between age 18 and 25 he rode over jumps as an amateur. I started riding very early, at age four or five, and showjumped and evented when I was young and then started riding as an amateur as soon as I could. I was a true amateur as I didn’t start working in racing until I was 19. I was lucky to ride about 70 winners, in Italy but also in Britain and France, in a relatively short career in the saddle.”

A couple of summer stints with John Hills in Lambourn as a teenager further fuelled the young Mario’s passion for racing and he soon joined Italy’s legendary trainer, Mil Borromeo in Pisa, “Mil Borromeo was a great trainer, very sensitive and with an amazing capacity to listen to his horses. His objective was to create champions and he succeeded many times during his career. He was on the same level as the top trainers from England, Ireland and France from the time. He was very sensitive and attentive to his horses. My official title with him was assistant but I was so young I was more of an intern.”

After a year with the Classic Italian trainer, Borromeo advised the young Barrati to spread his wings and continue his education, both in racing and academically.

The Botti Academy

The logical port of call was Newmarket and the stable of training’s rising Italian star of the time, Marco Botti. “I used to ride out in the mornings and go to Cambridge in the afternoons to learn English. The original plan was to spend just a year in England to pass a language exam, but after I passed the exam, Marco Botti proposed the position of assistant if I stayed with him. When I started he had less than 50 horses and during the four years I was there the number rose to over a hundred so it was a real growth period. I had the good fortune to ride horses like Excelebration who was exceptional, and to travel to Dubai, or Santa Anita for the Breeders’ Cup... He had six or seven real high-quality Group horses, who could travel and win abroad.

I learnt many things during my time with Marco and the most important was probably how to manage the horses in the best possible way to optimize their potential. I think the secret to his international success is that he travels his horses at the right moment. He understands when a horse is tough enough to go abroad, and he doesn’t take them too early in their careers.”

After four years in the buzzing racing town of Newmarket, it was time to continue the learning curve and despite an offer to join another compatriot, Luca Cumani, Baratti remembers, “everyone advised me to go to America or Ireland.” So the young Italian found himself in rural County Kilkenny. “Jim Bolger said he would only take me if I stayed for three years, but in the end I cut my time short. It was a very good experience and I learnt a lot about breaking in yearlings and working with youngsters. I learnt what I could in a short time as I was only there for three or four months, an intense experience of work and life. Mr Bolger is a real horseman, who is tough on his horses but always manages to produce champions. He can do things that others cannot allow themselves to do, because he breeds and owns a lot of the horses himself.”

Despite the prestige of his Classic-winning mentor, Baratti was unable to settle in Ireland. “I like the countryside, but I was isolated. I was 25 years old and never saw or spoke to anyone and the lifestyle wasn’t for me. So one day I told him, “I can’t stay three years”, and he said, “you want to train in London? You can’t train in London!” I’ll never forget that! But he understood and in the end he said, “I’ve taught a lot of top professionals, McCoy, O’Brien, but it’s up to you if you want to leave. I hope that you find someone as good as me…””

Pascal Bary an inspiring mentor

Next stop was France, and Baratti took advantage of a couple of months before his start date with his next boss, Pascal Bary, to join fellow Italian Simone Brogi who had recently set out training in Pau. He also spent a month with Brogi’s former boss, Jean-Claude Rouget, at Deauville’s all-important August meeting.

“The time helped me to learn French and integrate into the French ambiance, which wasn’t easy. I found it much tougher to settle in France than in Newmarket. As a foreigner I felt less well received. Even at Newmarket, I started as an assistant when I was 18 years old, with no experience, and it was tricky to manage a team of 25 or 30 staff. But when I started here it was even more difficult to handle the French staff. They would say to me ‘I’ve never done that in 30 years and I’m not going to start now…’ During the early days with Pascal Bary, I thought that France wasn’t going to be for me. Then it became a personal challenge and I decided to stick it out. Now, Pascal Bary is one of the closest friends I have here in Chantilly, but at the start he wasn’t an easy boss. It took two years, of the four that I was there, before we built up a real relationship. On my side, I was very respectful, and I saw him as someone who was very reserved, so we kept our distance. I was in awe of him and his career. He wasn’t interested in just winning races, he wanted to develop the best out of his horses. That’s why he had such a great career. 41 Group 1 wins in a 40-year career is a huge achievement. He won Dianes, Jockey-Clubs, Poules, Guineas, Breeders Cups, the Irish Derby… He’s the only French trainer to win the Dubai World Cup. He started off going to California for the Breeders’ Cup when he was very young. He would dare to step into the unknown, because at the time it was much more complicated to travel around the world.

I was lucky to be there at the time of Senga - who won the Prix de Diane and Study of Man won the Prix du Jockey-Club. So I worked with top horses, who were perfectly managed, and many of them were for owner-breeders. Very early in the season, when the grass gallops opened, he would immediately pick out the three or four standout horses and plan their programme. He could tell right away which ones had talent ‘this one will debut in the Prix des Marettes at Deauville… ‘ I remember that year the filly did exactly that and won; it was Senga and she went on to win the Diane.

When you spend time with someone at the end of their career, there is more to learn. Pascal Bary had a superb training method, and he had the success he did because he was very firm in his decisions. He’s not someone who changes his mind every day, and there aren’t many people like that nowadays. He was very sensitive to his horses and always sought to create champions. I try to keep in mind his method.”

Changing dimension

The string for third lot is now ready to pull out and we make our way through the yard which has been adapted to accommodate an expanding string.

“We recently acquired the next-door yard and we knocked through the walls of a stable to make a passageway between the two. I now have 73 boxes in these two yards, plus 15 at another site which has the benefit of turnout paddocks.”

Through a gate in the hedge at the back of the courtyard and we are straight onto the famed Aigles gallops as the sun starts to break through the clouds on what had begun as an overcast morning.

“It’s a magnificent site; we are so lucky to have such beautiful surroundings and for me to be able to access the gallops on foot.” As we make our way to the walking ring in the trees where the Baratti string circles before and after work each morning, the trainer tells me, “I still ride out every Sunday, bar only two or three weeks in the year. I think it’s important to exercise as many as we can on a Sunday and if I ride two, that’s a help to the staff and a real pleasure for me too.”

The string of around twenty juveniles, many still unraced, passes before the trainer who gives multilingual orders. “Here we speak Italian, French, English, Arabic and Czech,” he explains, “we try to all speak French but of course sometimes we communicate in Italian, especially when things get heated! We’ve more than doubled in size since last autumn and so we built up the new team throughout the winter and in spring. It’s all coming together now. For the first few years everything went very smoothly, but there were only half a dozen members on the team! When you get up to 25, it’s a different story.”

The team includes a couple of former Italian trainers who left their country and now work as managers for the burgeoning Baratti stable, plus veteran Filippo Grasso Caprioli, Mario’s uncle who was a leading amateur rider in Italy in his time. “He “just” rides out, he doesn’t have a position of responsibility but he does give us the benefit of his age and experience!”

Another vital member of the team is Monika, Mario’s Czech-born wife. “We first met at the Breeders’ Cup when I travelled with Planteur and she was the work rider of Romantica for André Fabre. When I first moved to France we both lived in the same village, 100m away from each other but we never bumped into each other. We met again four years after I moved to France. We’ve been together now for seven years and married this spring. Monika is an excellent rider and she also takes care of the accounts, but her most difficult job is taking care of our two small boys. I think she sometimes comes into the yard for a break!”

As we trudge across the damp turf to the Réservoirs training track, Baratti expands on his choice of Chantilly. “When I was in Newmarket I thought I would never leave, but then it was logical to continue here after I had done my time with Pascal Bary. And of course, the French system is very beneficial compared to elsewhere in Europe. The facilities here in Chantilly are second to none. When I first started I used to use all of the gallops but now I have my routine and regularly use Les Réservoirs. I often use the woodchip but there is plenty of choice. Once you have understood how each track works then it’s simple.”

The first group of two-year-olds canter past, and Mario runs through some of the sires represented: Siyouni, Lope de Vega, Wootton Bassett, for owners such as Nurlan Bizakov, Al Shir’aa, Al Shaqab and powerful French operators such as Laurent Dassault, Bernard Weill and others.

“This is the first year that I’ve had such a good panel of owners, and a better quality of horses. It is certainly thanks to Metropolitan and the successful season we had last year. In previous years, we did well with limited material, and we managed to win Listed or Group 3 races which isn’t easy when you only have 20 horses. This year we have more horses but haven’t won any big races yet (he laughs nervously) but they will come…”

Indeed days after the interview, the stable enjoyed a prestigious Group success on Prix du Jockey-Club day with the Gérard Augustin-Normand homebred Monteille, a sprinting filly who was trained last year by the now-retired Pascal Bary.

“It's very important to have owners who also have a breeding operation. They have a different outlook on racing and they are often the ones that produce the really top horses. They expect good results, of course, but they understand the disappointments and are generally more patient. The other owners are important too, and Metropolitan, who we bought at the sales, is the proof of that.”

Classic memories

Understandably, a smile widens across Mario’s face as he remembers the day when the son of Zarak lifted the Poule d’Essai des Poulains to offer the trainer his first major Classic winner.

“I was only in my fourth year of training, it wasn’t even in my dreams to win a Poule so soon in my career. It’s hard to describe, the joy was enormous. The fact that we ran in the race again this year, with a very good horse (Misunderstood) but everything went wrong, makes you realise now how difficult it is for everything to go right on a day like that. I always thought that Metropolitan was an exceptional horse. We were far from favourites in the Poule but I knew we had a good chance of winning. The owners rang me on the morning of the race and asked, ‘Mario do you think we can win?’ and I said Yes! He had finished fifth in the Prix de Fontainebleau and we had ridden him to avoid a hard race, but still, many observers overlooked him. Apart from in his last race on Champions Day, he never put a foot wrong. He confirmed his class when third in the St James’s Palace Stakes in a top-class field and then was beaten by the best four-year-old miler in Europe, Charyn, in the Jacques le Marois. And at the time, we only had three or four three-year-olds in the yard, so the percentage was amazing.”

Baratti had already tasted Classic glory a year earlier, thanks to Angers (Seabhac) who won the Group 2 Mehl-Mülhens-Rennen (German 2000 Guineas). A first successful international raid from the handler who learnt from some of the industry’s specialists.

“You travel if your horse is very, very good, or not quite good enough,” he explains.“If you travel to Royal Ascot, you have to be exceptional, the same for the Breeders’ Cup. But for Germany you can take a decent horse who isn’t quite good enough for the equivalent races here. Angers had finished second in the Prix Machado which is a trial for the Poule d’Essai. I already had Germany in mind for him if he was placed in the Machado, and he went on to win well in Cologne. Every victory is very important, the key is to aim for the right race within the horses’ capabilities. Each horse has his own “classic” to win, with a made-to-measure programme.”

Many expatriate Italian trainers target Group entries in their native country, but Baratti is not keen to explore this option. “I have never had a runner in Italy. I did make an entry recently but we ended up going elsewhere. Italian black-type is very weak for breeding purposes, so it’s not really worthwhile for me to race there. There are a lot of good professionals in Italy but I don’t really have much connection with them because I’ve never worked over there, I left when I was young.”

A realistic approach

Baratti’s adopted homeland of France has recently announced austerity measures for the forthcoming seasons to compensate for falling PMU turnover and pending the results of a recovery plan which aims to increase the attractivity of French racing for owners and public. France Galop prize money will be reduced by 6.9%, equating to 10.5 million euros during the second half of 2025 and 20.3 million euros for following seasons until a hoped-for return to balance in 2029.

“It’s normal,” says the Italian pragmatically. “It’s better that they make a small reduction now than wait two or three years and have to make drastic cuts. It’s necessary to take the bull by the horns, not like how it was in Italy when they let the situation decline and then it became too hard and too late to redress. We are fortunate to be in a country where prize money is very good compared with our neighbour countries in Europe, so a small reduction won’t affect people too much.

Owning racehorses is a privilege and a passion. It is a luxury and people should treat it as such, not buy horses as a means to earn money. If you buy a magnificent yacht, it costs a fortune, and it’s pure outlay. Money spent on having fun. Nowadays, a lot of people invest in racehorses for business purposes, but they need to have the necessary means. If you are lucky to buy a horse like Metropolitan and then sell him for a lot of money, that’s another story, but it wasn’t the aim at the outset.”

He remembers an important lesson on owner expectations from former mentor Pascal Bary. “I was surprised once when Mr Bary received some foreign owners in his office. They wanted to buy ten horses. He told them, the trainer earns money, not every day, but he tries, in any case his objective is to earn money, the staff earn money and the jockey earns money. Normally, the owner loses money. If things go well, they don’t lose much, if they go very well they can break even, and when it’s a dream, then you can make money, but that’s the exception to the rule. The guys had quite a lot of money to invest and they were there, open-mouthed. In the end they chose another trainer. But Mr Bary was right. If I decide to buy a horse tomorrow for 5,000€, I have to consider that 5,000€ as lost. If I want to invest, I should buy a house.

His explanation was very clear and that’s how racing should be understood. It would be nice to have a group of friends buy a horse, but it costs a lot. Ideally it should just be for pleasure, like membership at the golf, or tennis. It's an expenditure. And if in the end you end up winning, then all the better. And it can happen. Bloodstock agents do that for a living but it’s their profession. My owners are in racing for the pleasure.”

With an upwardly-mobile, internationally-minded and ambitious young trainer, Baratti’s owners certainly look set for a pleasurable ride over the forthcoming seasons, and the office walls are unlikely to remain white for long.

Henk Grewe - the Classic winning German Trainer

Article by Catrin Nack

When Grewe retired from race-riding and took up training in 2014, it wasn’t exactly the hottest news in German racing. He had been a middle-of-the-road jockey, never reaching lofty heights. But as a trainer, he has made it to the top of his profession.

Eleven years later and February 2025 - it’s six fifteen in the morning and It's pitch black. The first lot is out already, and Grewe is in the saddle.

The majority of German racehorses are trained on a racecourse. Nearly every main track – think Düsseldorf, Cologne, Hannover, Iffezheim or Hoppegarten – doubles as a training centre. A chosen few have the luxury of private premises, but Grewe shares Cologne racecourse with three other major trainers, and roughly 300 horses.

Shared facilities consist of a trotting ring, and two sand gallops, sand, not fibre. His roughly 78 boxes are split into four stable blocks, of various size and quality. The largest block of roughly 40 boxes was actually a grandstand in bygone times.

Tighter animal welfare measures saw a row of windows being installed, with one row of horses glancing onto the stable alley, the other side enjoying a room with a view to both sides.

Every box is filled generously with straw, something increasingly rare in domestic racing yards. “The year I used sawdust was my worst ever, and I am convinced there is a correlation. Horses feel comfy on straw so there you go.” Three horse-walkers grace the place, one is called “the terrace” as it has no roof. And basically, that’s it. The height of technical racehorse training.

A covered trotting ring is in the distance, but “that’s not mine. That’s Peters [Schiergen, of Danedream fame]” says Grewe.

No saltbox, treadmill, solarium, let alone a pool. Scales somewhere, “but I hardly use them.” He concedes that horses may have a perfect racing weight, “but I need to see that. If a trainer can´t spot it, well….”

There is a simplicity in the whole setup, mirrored in the trainer´s beliefs. “Really, you can train a horse anywhere. Hans-Walter Hiller [who was Champion Trainer in 1999, and whose yard he was attached to as a jockey] trained on a strip next to a motorway, so clearly you don’t need much.”

Grewe’s principles when it comes to readying horses are cut from the same cloth. “The most important thing is routine. Routine. Once the horse figures out what he has to do he can relax in that routine, and he feels secure. I don’t like fresh horses. On average my horses are out three hours a day, it comes down to three things: routine, the feeding, and proper medical care.”

The yard has a couple of paddocks now too, and some horses are turned out in the afternoon. Roughly 23 people work for Grewe, with active and retired jockeys playing a vital part in the morning. Thore Hammer-Hansen is one of them.

Having returned to his roots in 2024, the jockey, with a retainer from Cologne racecourse president Eckard Sauren, wasted little time to take German racing by storm. He combined with Grewe (but not Sauren) to win the German Derby on Palladium (more of him later); the end of the year saw him crowned Champion jockey as well.

Fresh from a trip to Riyadh, where he guided the Marian-Falk Weißmeier-trained, Straight to a respectable 5th place at Gp.2 level, Hammer-Hansen feels slightly under the weather but is full of praise of Grewe, who “is a team-player and a very good trainer”.

Much needed positives after other work-riders declare that the trainer's most remarkable trait is “his bad mood before the first lot”. While such statements are (hopefully) tongue-in-cheek, the relaxed atmosphere with a lot of banter is duly noted; Grewe is usually riding three lots himself and doesn’t shy away from the general chores.

Grewe doesn't miss a beat: while preparing his horse and answering cumbersome questions at the same time, his eye is all over the place and every idleness is (duly) spotted.

It all started inconspicuously. Born in 1982, his parents had a couple of horses, so the foundations were laid early on. “I had to decide whether I wanted to be a professional table tennis player or pursue horses. I felt there was more money in the latter.” The good, the bad and the ugly, money is a recurring theme for Grewe.

It is what drives him, because, quite plainly, “I want to be rich”. Grewe retired from race-riding with a handful of Black-Type wins to his name. With the help of then-business partner Christoph Holschbach he set up a limited company to train racehorses on August 1st 2014, with a mere 12 (bad) horses; his first runner, just 20 days later, was a winner.

They kept coming. It was quantity over quality at first, “I had to get my name out”. In his prime Grewe had roughly 120 horses. The first Listed winner came in 2017, the first Group winner, Taraja in a Hamburg Gp.3, in May 2018. Khan, who eventually switched to hurdles, provided the breakthrough at the highest level when taking the Großer Preis von Europa in September 2018.

The hardy and consistent Rubaiyat flew the flag for four seasons; unbeaten as a 2yo in 2019, he won at least one Group race in every season. While he missed out on valuable Gp.1 glory, his trainers list of high-class winners started growing: the German Derby (Gp.1) twice (Sisfahan and Palladium), the German Oaks (Muskoka), the Großer Preis von Europa (Donjah and Khan), The Großer Preis von Bayern (Sunny Queen and Assistent).

When asked if he has a preference for fillies or colts, the answer is an emphatic “no”. While the German Derby was the highlight of 2024 (next the birth of his son Mikk), the yard won eight more Group races. Having been crowned Champion Trainer in 2019 and 2020, Grewe's focus started to shift.

He still likes to travel, but now it´s for Black-Type and not for claimers. His intimate knowledge of the French racing system means that country still is his preferred hunting ground, along with Italy, where he has won 10 Group-races to date if our counting hasn’t let us down. But gone are the days when for every domestic runner he had two abroad.

Grewe no longer has that number of horses, nor does he want to. “Horse numbers are down [in Germany] because training is just too expensive,” he admits. “Look, I am very open about this but every month my owners part with €3000 per horse. Who can afford that? Look at the prize money and do the maths. Syndicates are the solution, no two ways about it.”

It helps that Grewe has syndicated horses in his yard. While Germany may not be ready for micro share syndicates (even though Hammer-Hansen evidently thinks so), it was certainly ready for a syndicate called Liberty Racing, founded in 2020 by shrewd entrepreneur Lars-Wilhelm Baumgarten and partner Nadine Siepmann. Selling 25 shares at €25.000 apiece (for a bundle of three hand-picked horses) may have taken some persuasion at first, but success came almost instantly; now there is a waiting list.

Buying (and owning) a Group 1 winner in every year since its foundation, Liberty Racing has now won two German Derby’s in a row. Fantastic Moon was their flagbearer in 2023 when taking the blue ribbon for trainer Sarah Steinberg, and Palladium was the winner of last year's race on the first Sunday in July - the traditional date for the German Derby.

Palladium was trained by Grewe, who still marvels in the wonders of it all. After spending considerable time telling me that he doesn’t ‘do’ emotions, doesn’t have a favourite horse and doesn’t get attached to horses, his eyes did light up when recalling that day. “Look, nothing came easy to Palladium and he didn’t excite us at home.” He ran ok as a 2yo [no win] and proceeded to win a small race on his fourth start, before finishing a lacklustre 4th in Germany's main Derby trial, the Union Rennen.

“I am still not sure what wonders combined in Hamburg and how we managed to win there. It was great, especially with my girlfriend being heavily pregnant with our first child [son Mikk was born later that month]“.

So you had emotions that day? “Maybe for five minutes,” he smiles.

Mikk naturally changed a lot. “Everything changed with him, and I wonder what I did all day before he came. We came home from a holiday the other day, so many suitcases and his buggy. I thought - clearly we need a bigger car! I don’t think it changed the way I train, but I do feel more pressure to succeed, to earn money as I want him to have every chance in life.” The money, right? No emotions, right?

Palladium of course went on to write his own chapter in Grewe's (and Liberty Racing’s) vita when selling for €1.4 million at last year's Arc Sale. This made him the highest-priced horse ever to go hurdling and joined Nicky Henderson’s famed Lambourn stable. He was a winner on his first start over the smaller obstacles at Huntingdon in late January. But, come this summer, an ambitious flat campaign may beckon too.

It's not that Grewe and Liberty Racing are resting on their laurels. The latter naturally features prominently on Grewe's owners list, with five 3yo’s for three different syndicates. Among those is a strapping son of Camelot, purchased for €180,000 at the 2023 BBAG Sales and from Röttgen Studs fabled A-damline.

Called Amico, and stabled in the same block that housed Assistent and Muskoka, Grewe asks, “do you want to see this year's Derby winner?” Well that is some introduction. History in the shape of three Derby winners in a row would beckon for Liberty Racing, and while that’s not unprecedented in the annals of the German Derby, it certainly hasn’t been done with shared ownership.

Nowadays Grewe trains roughly 80 horses and runs a tight ship. “It´s too expensive to have a bad horse in training and I am quick to call a spade a spade. Not everyone likes that.”

He always has an eye on the strike-rate and had nearly 30% winners to runners in 2024. His horses are brought along a little slower nowadays, but 2yo racing with its lucrative sales races is vital to his business. “Nothing wrong with training 2 year olds, in fact they need it and studies clearly show the benefit of starting early. I am no fan of pre-training though.”

He calls a spade a spade when it comes to German racing too, where low prize money, “ineffective” leadership and rival racecourses are his main complaints.

He misses the sense and obligations for the wider good of racing from the latter group in particular, but feels the tide is ever so slowly turning for the better.

“They [the racecourses] need to work together, and with the owners, to create a more potent environment. My impression is they slowly understand. I do speak my mind, and people listen.”

Syndicates, as mentioned, are Grewe’s idea of accelerating fortunes in German racing and he sees responsibilities with trainers, himself included. “I know I need to get much better at communicating with owners, and yes, no doubt trainers could – and should – set up racing clubs and syndicates.”

Grewe remains as hungry as ever, if not hungrier. “I have won nearly everything worth winning in Germany, but there is loads left abroad.” Eckhard Sauren's horse, Penalty - a rare son of Frankel on these shores, is pencilled in for European Gp.1 mile races.

Constant rumours suggest that Grewe is only biding his time in Germany, but more imminently he plans to take the helm of his training company buying out his (new) business partners in 2025. New chapters will be written, and the best is surely yet to come.

Gavin Cromwell - the leading dual-purpose trainer

Words by Daragh Ó Conchúir

Gavin Cromwell has just arrived at Goresbridge for the Point-to-Point and National Hunt Horses-in-Training Sale.

This is off-Broadway fare, with a top-priced lot of €62,000 taken home by Charles Byrnes. Only a handful of Irish trainers are active. Most of the stock is bound for Britain.

It offers a glimpse as to why Cromwell is no longer a farrier but an eight-time Grade One and six-time Cheltenham Festival-winning trainer, with three victories in Prestbury Park’s signature championship contests.

He may now be officially categorised in a so-called Big Four in the Irish jumps game but is bemused by the association with Messrs Mullins, Elliott and de Bromhead given their relative rolls of honour. His market remains primarily at far lower levels.

Three days previously, Cromwell acquired three horses at the Tattersalls December Yearling Sale. Lest one has forgotten, the Meath man has saddled group winners on the Flat too, at two of the most exalted venues of that sphere, ParisLongchamp and Ascot. He has enjoyed the thrill of Royal success at the latter course twice.

Princess Yaiza scored in the Prix de Royallieu in 2018, nine months after Raz De Maree delivered in the Welsh Grand National. Raz de Maree was a 13-year-old gelding galloping over nearly 3m6f on heavy ground and jumping 18 fences (four were omitted). About three and a half years later, two-year-old filly Quick Suzy scorched to glory in the 5f Queen Mary Stakes on good-to-firm going at Royal Ascot.

The three yearlings were bought for an accumulated £108,000, a Ghaiyyath colt being the most expensive at £40,000. Later on, Cromwell would add another trio to his burgeoning army, costing a grand total of €49,000 between them. The €25,000 for Aspurofthemoment is his largest single outlay.

They type of horses he has bought over these few days not only magnify his achievements, and his talents, but offer a glimpse of his all-inclusive approach to training and sourcing, of his ambition and tireless endeavour. There is no pigeon-holing this guy. Juveniles, veterans, handicappers, elite performers, over obstacles or on the level. You have a horse with some ability, he will get it to win.

And while he has had some significant support from JP McManus in particular over jumps and Lindsay Laroche on the Flat, both relationships grew out of their attraction to his results and were cemented by continuing success thereafter. In the same way, he will train a couple of horses for Qatar Racing next season, having sold them one this year. These affiliations developed from the foundation stone of the entire operation: sourcing stock cheaply as most of his owners do not have deep pockets. If they are good, they are often acquired by people that do.

What being in Goresbridge tells us is that Gavin Cromwell is always on it, to use modern sporting parlance. He does not switch off. And the results speak for themselves.

How recently was Gavin Cromwell still a farrier? Many will be surprised to hear that he only finished “four or five years ago.” That’s after he had become a Cheltenham Champion Hurdle winner.

The 50-year-old is now a six-time Festival victor at Prestbury Park, with half of those successes coming in championship races, Flooring Porter’s Stayers’ Hurdle double arriving in the wake of Espoir D’Allen’s Champion Hurdle triumph in 2019.

His tally of winners over jumps and on the Flat continues to rise, while his numerous cross-channel raids have yielded 14 winners at a 23% clip last season in National Hunt and an even better percentage of 5/20 since the start of 2023 in the summer code.

This has been achieved within a clear business strategy that focuses on a sound financial footing while marrying that with a philosophy based on ambition, and a development of leadership techniques that have proven more essential as the operation has grown from his early days on a 14-acre greenfield site, to the 150 stables and state-of-the-art facilities on 80 acres at Danestown. That brings more staff, more owners, more suppliers. More demands.

So you develop a team around you. The likes of right-hand man Garvan Donnelly. Keith Donoghue, the jockey who helped revitalise Tiger Roll and Labaik in his days working for Cromwell’s former housemate, Gordon Elliott. Race planner, Troy Cullen. Kevin and Anna Ross, brought on board to oversee the purchase of more Flat horses, many of which have been sold at a considerable profit.

Being among the aforementioned quartet excluded from some races by Horse Racing Ireland as a strategy to increase opportunities for the rest of the trainers came as a shock. Not least because he has not had a Grade One winner in Ireland since Flooring Porter announced himself a star of the future in the Christmas Hurdle at Leopardstown four years ago. That was his fourth top-flight triumph and that tally has been doubled across the water at Cheltenham and Aintree.

For context, Willie Mullins saddled a world record 39 last season alone.

Cromwell should really be heralded as a poster boy for what is possible in what some observers have argued is an unproductive, overly polarised environment, unconducive to fresh blood breaking through.

While he would love a yard of Grade One horses and dreams of registering a maiden Group One, most of his stock comprises handicappers. Therefore, the selling angle is vital. The paradox of that model is he sees the negative impact that has had on the depth of the Flat game, as well as the National Hunt.

This all makes for a riveting conversation.

Given that there isn’t a category of race Cromwell does not have a horse or an owner for, talent acquisition is a round-the-clock consideration. And it is one of the areas he has had to outsource because of his expansion.

“Kevin and Anna Ross have been helping to buy the yearlings for the last season, and this season. That’s working out great,” he says and with good cause.

Among the selections last year are dual group-placed Fiery Lucy, who finished her season a slightly unlucky three-length fourth to Lake Victoria in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf at Del Mar. Mighty Eriu was sold to Qatar Racing after finishing second on debut and went on to be runner-up in the Queen Mary, Cromwell’s worst result from his three juvenile runners at Royal Ascot. And Chorr Dubh was sold to America for six figures after winning on debut at Gowran Park. That trio cost less than €80,000 between them.

Diego Ventura was more expensive, relatively, at €72,000 but that was at the Tattersalls Breeze-Up Sale in May. He won on debut two months later under Cromwell’s go-to Flat pilot, Gary Carroll, and was promptly sold to Wathnan Racing, transferring to the tutelage of Hamad Al Jehani in Newmarket.

“I’ve always bought all my own horses up to this but it’s very hard to find time to do everything, and then, of course, to try and find someone that you trust, so Kevin and Anna have been great for the Flat horses.

“I’m taking a run down here to Goresbridge today and it’s the lesser point-to-point horses but we have lots of lesser orders. Predominantly, it’s the lesser horses that we have.

“You’re constantly trying to think outside the box and trying to buy value, and trying to buy a horse that could potentially turn out to be a decent horse. You would always be trying to buy an unlucky horse. A horse that was second or third maybe, in some of those maidens, and the winner maybe made three or four hundred thousand. And maybe he had three or four runs, and it didn’t happen for him. Maybe he could have a fall mixed into the form.”

It brings to mind Emmet Mullins revealing in this publication last year that he always had an eye on strong finishers in point-to-point maidens. He prefers a horse galloping through the line in third to a winner hanging on. The market can miss a horse like that. When you don’t have a huge reservoir of funding, you have to be smart, identify a gap that few, if any, have noticed or have interest in.

“The other thing you have to do is, you have to take a chance. I would buy some of these horses on spec; find them and bring them home. I bought Will The Wise last year on spec, £95,000. It was as much money as I’ve ever spent on spec on a horse. But thankfully, I got someone to buy him.

“I suppose when things are going well, you can have the confidence to do that. You’ll find someone. It’s a little bit easier for me to say that than it is for a smaller trainer that has a handful of horses and no access to any owners. It is difficult but listen, I was that person one time. I remember buying a horse in Newmarket and he stood me 20 grand. I couldn’t find anybody for him, and I had to sell him to another trainer.”

But he kept going back. After stints with Dessie Hughes and Paul Kellaway, and at Flemington Racecourse, while he chased a dream of being a jockey, he took out his licence to train in 2005, having learned his trade as a farrier. Dodder Walk was his first NH winner, in Cork on April 7, 2007. Five Two broke the duck on the Flat at Dundalk on November 26, 2010. Balrath Hope bagged the Ulster Oaks two years later and Sretaw delivered a big pot with the Irish Cambridgeshire in 2014. Elusive Ivy won the JLT Handicap Hurdle and Mallards In Flight the Glencarraig Lady Handicap Chase.

By now, his services as a farrier were much in demand, with the high-flying Elliott a major client. As he notes himself, it is only until very recently that being the man that shod 2015 Gold Cup winner, Don Cossack wasn’t what people tended to mention when his name came up.

Having started with a barn for eight horses to train as a hobby, with an apartment above it that he lived in, Cromwell added a second for 13. The recession gazumped all progress but he would not be deterred. Picking up horses and making contacts brought better results. Further barns were built, housing 25, then 30 and then 50. An isolation yard was added also.

The five-furlong straight, uphill woodchip gallop has worked splendidly with the Flat juveniles ready, and while his jumpers will use it too, they are generally worked on the round, deep sand gallop complete with speedometer.

While the share in prize money is considerable, it is moving the Flat horses through the international market that really greases the wheels and facilitates the improvement of the amenities. It is a delicate balance, when you are hungry to climb the ladder and improve the quality of your string, but pragmatism ensures you are still in business next year.

“We’ve got plenty of yearlings this year and sold plenty of two-year-olds. I suppose it’s a business model that we’re buying them with the view to trading them. I have a few Flat owners, the likes of Lindsay LaRoche, who owned Princess Yaiza and Snellen, who won at Royal Ascot. Those horses are bred to race and bought to race. So that’s slightly different to the rest of the business model.

“We sold Mighty Eriu this year to Qatar and she stayed with us for a little bit. She went to Royal Ascot and I think we’re going to potentially have a couple of Qatar horses for next season. We have one three year old here at the moment for them.

“So some will stay in training, and then others are in training to be sold, whether they’re sold to existing owners, or maybe someone could buy them and they stay at the yard, remains to be seen. But it’s a business model, and it’s been working nicely. We’ve bought plenty of yearlings now for next season and hopefully they will work out.”

The prize money in Australia, Hong Kong and America puts a value, in particular, on a band of horse that cannot be replicated in Europe. So capitalising on big offers will always make sense but it does mean that the pool is thinning, in both codes, with many of those Flat horses having previously transitioned into NH athletes.

“I actually didn’t go to Newmarket Horses-in-Training Sale this year or last year. It’s so hard to buy those three year olds to go hurdling. It’s too expensive for what they are, for what we want them for. The Australian market is too good and lots of those international markets.

“We sent a few to Goffs Horses-in-Training Sale. They were looked at numerous times, and they all sold. They had won a few, but they were only at a level. We had two National Hunt horses at the sale, and they never got looked at once. It’s a world market (on the Flat), and they went to all different countries, and there’s no problem selling them. It’s a great trade. But it means we can’t buy off the Flat to go jumping or to have as good dual-purpose horses.”

Attending sales are about more than going with a shopping list.

“The lads who are getting on are the lads you’ll meet at the sales. You have to be buying your horses all the time. And sure you don’t know who you’re gonna meet. I seldom go to a sale that I don’t come home with a horse, whether I met someone and I got the horse to train, or I bought him.”

The future dividend of networking can be significant too because relationships are at the core of anything that thrives. Gavin Cromwell Racing is no different.

“You spend your whole time trying to surround yourself with good people and if you can keep adding to that, it makes everything work better, and it makes life a lot easier. Someone said to me one day, ‘You spend all your time trying to make yourself redundant.’

“The system is there, and the people are there to implement it. You’ve the 3Ds: decide, delegate and disappear. And I think sometimes, the hardest part of that is to disappear. But if you decide and you delegate, there’s no point doing them unless you disappear. You delegate, you have to pass on the responsibility, and the only way you’ll pass that on is to disappear. And if it’s not done right then, well then you’ve to go back to the start again. But if you’ve decided and you’ve delegated, you have to pass out the responsibility, and you have to do it with confidence. That’s what makes everybody grow.”

A really clever person knows what they do not know. And they go about ensuring that they acquire those skillsets or surround themselves with people that possess them. That’s how it has been with the management of people and Cromwell’s leadership.

“I suppose you learn from other people. I learned an awful lot from some of my owners, who are obviously very good in business, and chat to them. They pass on a lot.”

There have been some personnel additions in recent years that have been pivotal in the upward surge.