Is SDFT tendinopathy a “professional condition” in the jumping racehorse?

Words - Jean Baptiste Pavard

Tendon and ligament disorders are one major cause of poor performance and wastage in equine athletes. The most common structures involved are the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT), the suspensory ligament (SL), the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) and the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT), also called the inferior check ligament.

Thoroughbred racehorses are particularly predisposed to tendon and ligament injuries accounting for approximately 50% of all musculoskeletal injuries to competing racehorses. However, some structures are much more exposed to injuries than others in this population of equine athletes.

Most tendon injuries in racehorses occur to the forelimb tendons, with overstrain injury of the SDFT at the very top of the list. This is particularly true in jump racing, where the prevalence of superficial digital flexor tendinopathy has been found to involve up to 24% of horses in training over 2 seasons (Avella et al. 2009) and could be considered as a “professional condition”.

The higher exposure of tendon injury in jumping horses compared to flat racehorses might be explained by the fact they compete over longer distances, for more seasons and are generally older than horses that race on the flat. Another reason is very likely that the SDFT of jumping horses support bigger strains, and repetitively, when landing over fences.

The main issue for this type of injuries is that tendon healing is slow and requires a long recovery between 10 to 18 months depending on the severity of cases. Although the scar tissue of tendon injuries can be optimised with an effective rehabilitation program, its functionality remains inferior with relatively high re-injury rates in the years following the original lesion. Thus, a complete understanding of SDF tendinopathy and its major risk factors in jump racing are very important to improve prevention and early management of the condition which is a potentially career-ending condition. In the racing community, it has become crucial given big issues it involves in sporting and economic terms, as well as for the health and the welfare of racehorses.

SDF tendonitis - characteristics in jumping racehorses

SDF tendinopathy is one of the most common injuries in jump horses with a prevalence from 10 to 45% depending on epidemiological studies with some variations among trainers. Most of the cases involve the forelimbs, but hindlimb injuries also occur. Typically, lesions are found at the mid-cannon level in a central core lesion.

The disruption of the tendon fibres might generally occur in this area because it appears to be preferentially loaded and degenerates more over the time. However, injuries of the SDFT can be seen at all the levels of the tendon. They are most commonly unilateral, but bilateral SDFT injuries can also occur.

Tendinopathy is a result of mechanical overload, varying from single fibril disruption to complete rupture of the whole tendon. The most common cause of SDFT overstrain injuries in NH horses is an accumulation of damages from repetitive overloading.

The structure of the tendons in horses is matured around 2 years old, and after maturity there is very limited or no adaptation possible. It means that if tendons accumulate an excess of micro-damage over the time (tendon cells have a capacity to repair defects, but it is limited and need time), they become weaker with a loss of elasticity and strength leading to a point where higher SDFT loads / strains result in disruption of fibres with a clinical tendon injury.

Moreover, it is important to be precise that forelimb flexor tendons in racehorses function close to their maximal load / strain-bearing capacity with a narrow safety margin. While failure of the SDFT has been shown occurring for tensile strain* from 12 to 20% in vitro, peak strains within SDFT at the gallop are by around 16%. Since racehorses operate close to the functional limit of the SDFT during fast work, any risk factors that lead to higher loads on tendons during training or racing can result in clinical injury with significant disruption of tendon fibres. Some of these in NH horses are discussed below.

* % increase in length from original length / tensile strain

Causes – Risk factors

Epidemiological studies have identified risk factors for SDF tendinopathy in racehorses. As discussed previously, jump horses are at greater risk than flat racehorses and it could be partially explained by horses being older in jump racing.

Indeed, risk of SDFT injuries increases considerably with age and it appears that the prevalence in jump horses is more important in horses older than 5 years old, with the maximum injury rate seen in horses 12 to 14 years of age.

Other major risk factors identified for SDF tendinopathy are frequent high-speed work, longer race distance, harder racetrack surface, heavier bodyweight and longer training career. Although they were not clearly identified as such, fatigue in relation with exercise duration or lack of fitness and conformation / shoeing (long toe, low heel) might increase the risk of SDF tendon injuries.

In jump racing, SDF tendonitis appeared more common in steeplechasers than in hurdlers, but the reason may be the older age of the first ones rather than the type of racing.

Diagnostic

Assessment of suspected tendon injuries should be based on history and clinical signs associated with diagnostic imaging. In many racing stables, people assess forelimb flexor tendons daily which can help to detect the early lesions of SDF tendinopathy.

However, first signs may be very subtle and variable depending on history, severity and location of injury. They are usually noted within 24 hours of fast work or racing but can also develop at slower work. It is often subclinical and resolves quickly for non-severe injuries with acute lesions characterised by heat, soft tissue swelling and pain on palpation, whilst chronic ones appear with fibrosed thickening.

Overstrain SDFT injuries are classically in the mid-cannon area and present a more or less severe change in profile of the back of the limb leading to the well-known qualification of “bowed tendon”.

However, the obvious signs of inflammation (thickening and heat) are not always present even for some significant injuries and lameness doesn’t appear to be a very consistent feature associated with SDFT injuries. It is typically mild (1 to 2 grades out of 5 at the trot) and improves rapidly over the first week after the injury, however the tendon remains weakened. Consequently, the level of lameness and pain on palpation don’t have a good correlation with the severity of the lesion, except in the most severe cases.

In cases of apparent “bowed” injury with pain response on palpation, it is sufficient to consider there is likely an active tendonitis. In more subtle configuration, the need for ultrasound is indicated to confirm and assess the extent of the lesion.

It may be best to perform or repeat tendon scans at 1 to 3 weeks after clinical injury first noted. Indeed, it allows us to assess lesion severity more accurately because of ultrasonographic underestimation of lesion extent at the beginning of tendon injuries. It is also very important in cases of suspected lesions but initially not well defined.

Moreover, both tendons should be systematically examined on ultrasound for 2 major reasons. Firstly, SDFT tendinopathy are bilateral in up to 67% of cases (Webbon), and secondly it helps to differentiate active lesions versus subclinical changes on ultrasound (ex. “juvenile tendinitis”). A careful ultrasound assessment is also keen to exclude the presence of potential concomitant lesions (ex. SL desmitis).

When SDFT lesions are suspected, the horse should be put at stall rest with only short hand walking until the injury is confirmed or not by ultrasound a few weeks later.

Ultrasound is routinely used by equine veterinarians and is elected to diagnose SDFT injuries as first-line diagnostic imaging. Whilst it is particularly relevant to document tendon lesions, it has been beneficial to develop a scoring system using specific measurements in order to categorise the severity of SDFT tendinopathy.

It is also very useful to establish prognosis and monitor the healing process in line with an adapted rehabilitation program.

Prognosis and return for racing

The prognosis of SDF tendinopathy can be very variable depending on the severity of injury, the convalescence program and the type of racing. Overall, sport prognosis in the Thoroughbred is guarded with a reported return to racing from 20 to 60 % of cases. The major issue of tendon injuries in racehorses is the need for a long recovery and the high rate of re-injury due to poor regenerative capacity of tendon tissue, which is considered as a limiting factor for racing. However, return to training / racing activity is common for most mild / moderate SDFT injuries.

A study with jump racehorses affected by SDFT injuries classifying lesions severity by ultrasound established that all horses with mild lesions returned to training, and 63% raced. 50% of moderately affected horses returned to training, and 23% raced.

In severe lesions, only 30% of horses resumed training, and 23% raced. In the study, the mean of reinjury rate for horses resuming work was 40% over a period of follow-up from 9 to 30 months, but some studies with longer follow-up reported up to 80% of horses sustaining a re-injury. Also, it is remarkable to note that a significant number of re-injuries affect the opposite normal limb.

Definitely, long-term prognosis is influenced by the severity of the lesions. The more severe SDFT lesions are, the lower chance of return to racing, shorter racing career and drop in racing class of those resuming there are. Complete ruptures of SDFT are hopeless for sport prognosis, but paddock life remains possible.

The other factors established to influence the sport prognosis in racehorses affected by SDFT lesions are concomitant lesions, and more particularly bilateral tendinitis which have very poor prognosis. The less classical SDFT lesions like those at the level of carpal or proximal cannon have poorer prognosis for racing and ongoing lameness is frequently present. While it is difficult to study the influence of rehabilitation programs due to the need for a long period of follow-up, controlled exercise showed to provide better prognosis than only uncontrolled pasture rest.

Treatment & Management: How to optimise the healing of tendon lesions?

Contrary to bone, healing of tendon lesions doesn’t allow you to get back pre-injury tissue due to its poor regenerative capacity. It means the structure and function of healed tendons are modified with different mechanical properties. Thus, the aim of SDF tendinopathies’ treatment is to optimise the healing process in order to get a strong and functional repaired tendon as much as possible.

Although there are different options available in the management of SDFT lesions in racehorses, all of them should respect a long recovery with progressive return to work. As said previously, tendon healing is slow, and it is common to consider at least 12 months for return to racing in horses affected by SDFT injuries.

To understand how to manage SDFT tendinopathy, it is important to consider the different phases in the tendon healing process.

In the initial days following the injury, the acute phase is characterised by inflammatory reaction. For a long time, it was advised to control quickly and aggressively the inflammatory response to limit damage to the tendon. However, it is now more and more controversial because the initial inflammatory phase would be beneficial for the repair process of tendons.

The best management of this phase is to treat only in case of excessive pain and acute swelling through the use of anti-inflammatory drugs and cold therapy locally for a period of 3 to 5 days. During this phase, it is important to minimise exercise with stable confinement for the initial weeks. As we discussed previously, the ultrasound assessment of tendon injuries is generally best performed 1 to 3 weeks after the initiation of the injury because it allows to determine the full extent of the lesion. Thus, it is recommended to scan flexor tendons at the end of the acute phase to grade the severity of the lesion and establish a rehabilitation program and prognosis for return to racing activity.

The other crucial period in the management of SDFT tendinopathy is the rehabilitation phase which can begin soon after the inflammation subsides. The cornerstones of healing tendon are the need for time and progressive graded and controlled exercise program. Protocols are quite empirical due to the difficulty to compare long-term outcome with homogenous groups.

Indeed, the program should be determined in relation to the severity of the injury, but classically at least 6 months are necessary for return to cantering. A typical program is to introduce walking once the acute phase has passed with gradual increasing duration until 12 weeks. Ideally, monitoring of healing with ultrasound assessment every 3 months allows to control the evolution of the repair through an assessment of fiber pattern alignment and tendon/lesion size. In normal evolution, trotting can be introduced after 12 weeks and cantering after 32 weeks. Generally, the re-introduction to normal race training is resumed not before 8 to 12 months. Prognosis of SDFT lesions reported for horses rested for less than 6 months is poorer with higher risk of re-injury.

Additional therapies can be used in the aim of optimising the healing of tendon tissue after injuries. Some of them are more and more popular and promising, but it is still difficult to evaluate and compare their efficacy. These modalities have to be considered as an additional intervention to graded exercise programs.

The main interest of these therapies is not to reduce rehabilitation, but to optimise the healing process reducing the chance of re-injury after return to training. These additional therapies range from firing to intralesional therapies with PRP (Platele-rich plasma), PSGAGs (Polysulfated glycoaminoglycans), growth factors (IGF-1) or stem cells. To optimise the efficiency of these therapies, the treatment should be generally realised during the acute phase (more or less 2 weeks after the initiation of the injury).

How SDF tendinopathy can be prevented in racehorses

Prevention is very important due to long recovery and guarded prognosis linked to high re-injury rate. 23–67% of horses with tendon injury treated using conservative methods will re-injure their tendons within 2 years of the original injury.

Strategies with success in preventing/reducing the incidence of tendon injury have not been validated; however, awareness of risk factors associated with SDFT tendinitis provides some useful guidance.

Avoid excessive training to fatigue and permit sufficient recovery time after racing or high-speed training.

Avoid use of poorly prepared or inappropriate track surfaces.

Long-term use of exercise boots/bandages may also contribute to increased risk; magnitude of this risk is unknown but should be balanced against rationale for routine use of bandages in horses that are not prone to interference injuries.

Strategies to reduce risk of reinjury of a rehabilitating/ rehabilitated tendon have also not been validated; however, it is rational to limit excessive loading of tendon.

Possible aspects to assist with above: incorporate treadmill use in training programme; attention to rider weight; minimise horse accruing excessive body condition; ensure maintenance of good dorsopalmar foot balance.

Possible benefit to be derived from regular post-exercise cryotherapy (such as cold water immersion): cooling the lower limb effectively can reduce enzymatic activity in tendon and potentially inhibit cell attrition resulting from high-intensity exercise.

Tracks that are very hard result in higher speeds and increased peak impact loads. These fast tracks are therefore more likely to produce overstrain injuries of tendons.

However, tracks where the surface is uneven, slippery, or shifty seem also to contribute to damaging loading patterns on tendons. Numerous factors influence the mechanical behaviour of a track surface; the weather and track maintenance have a major influence. Moisture content affects all tracks’ mechanical properties, and extreme temperatures appear to affect some synthetic tracks’ mechanical characteristics dramatically.

Experience over years with a particular track type will allow identification of track conditions that may predispose to tendon injuries.

Fatigue is influenced primarily by the horse’s work schedule, level of fitness, and intensity of competition. Fatigue should be considered as a contributor to tendon injuries. With the onset of muscle fatigue, a horse’s stride characteristics change,13 altering the forces on the tendons. Fatigue in any sport results in an inevitable loss of form and coordination in each stride, which is likely to result in an increased risk of injury.

At high speed, lameness may result in excessive loading of the tendons in the contralateral limb.

Horses who are overweight or carrying excess weight will produce greater forces on their tendons compared with lower weight individuals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, tendon and ligament disorders prove to be a major cause of poor performance and lameness within the racing industry. With SDF tendinopathy being at the forefront of these lameness’, there are many strategies that can be adopted to prevent / reduce the incidences of tendon injuries within the thoroughbred.

EMHF - The state of jump racing around the world

Words - Paull Khan

What state of health is jump racing really in? For someone living in Britain, for example, the picture is a little confusing. On the plus side, interest levels in the sport relative to the flat seem never to have been higher – of the top British races by betting turnover, almost all are over obstacles. And no festival, Royal Ascot included, generates more anticipation and excitement than does Cheltenham. Then one considers Ireland and the merciless pummelling, which the Brits have become accustomed to, of the home team by Irish-trained horses at that very Festival. And France: you won’t find a topflight jumps card where the commentator’s mastery of French pronunciation will not be put to the test – such is the prevalence of French-bred imports.

But then, on the darker side of the coin, one cannot fail to register increasing societal unease. A growing unwillingness to accept the unavoidable reality of injuries and fatalities, however rare their occurrence. And views being expressed that these headwinds are not only serious – they may be terminal, with venerable trainers opining that jump racing in Britain will not outlive them. And we are aware of the swingeing contraction of jump racing in Australia, which gives those existential fears more weight.

So, your columnist set out on a journey of discovery – to try to find out the true state of health of jump racing globally.

The first thing I was struck by is how rare a bird jump racing is, globally speaking. There are vast tracts of this planet on which the sport simply does not exist. More troubling yet, in several parts of the world there are memories of a sport that once existed but that has now perished.

Take Canada. Ross McKague of the Canadian Graded Stakes Committee sets out the picture starkly. “We have never had, do not currently have, nor are there any plans for, any organized jump races in Canada.”

Similarly in South Africa. “Apart from one or two amateur jump races on the inside of the race course in the Eastern Cape at the now defunct Arlington Race course”, Arnold Hyde, Racing Control Executive at the National Horseracing Authority there explains, “I am not aware of jump races in an official capacity taking place here. I guess that there has not been a culture for jump racing in South Africa and with our dwindling horse population (hopefully with the latest import/export developments the trend is reversed), I cannot see this changing anytime soon”.

How about South America, then? Ignacio Pavlovsky, IFHA Technical Advisor for that continent, recalls there having been racing in Chile once upon a distant time. His research reveals that the last steeplechase was held there in 1986.

So where, outside Europe, is this elusive creature to be found? The green in the background maps gives the answer. The USA for one – but restricted to a ribbon of States in the East of the nation. We have mentioned Australia, where, within recent years, the sport has ceased in both Tasmania and South Australia and is only now to be found in Victoria. Then there’s New Zealand and Japan. And that, unless anyone corrects me, is just about it.

What is the scale of jump racing in these non-European countries, and how has it shifted in recent decades? Taking as our simple metric the number of jump races staged, we can see that Japan has virtually flat-lined over the past 20 years. USA, meanwhile, has seen a 20% decline, while New Zealand’s programme has all but halved and Australia’s has worse than halved.

Over that period, there has been a remarkable consistency in what has happened to average field sizes. In America, they have reduced by 13%, in New Zealand by 14% and in Australia by 15%, indicating that the pool of jump horses is contracting at a faster rate than the number of contests on offer. The average jump race in Australia attracts 8.2 runners; that in New Zealand 7.8 and that in the States just 6.5. Reducing field sizes is, in fact, a scourge of jump racing affecting virtually all of the world’s jumping nations.

And what of the future? Hearteningly, two recent reviews, the first in New Zealand and the second in Australia, have come down in favour of the continuation of the sport. The latter took place against the backdrop of calls from the local RSPCA for the closure of the sport in Victoria, following the deaths of three horses at the August meet in Ballarat.

September’s announcement from RV stated that “Due to the increase in fatal incidents across the 2024 jumps racing season, this year’s review will go beyond the standard process. A broader, whole-of-business approach will be adopted to analyse a broad range of metrics….The report and recommendations will consider the future viability of jumps racing in Victoria, and/or what further changes can be made to improve the safety record of the sport”.

RV’s Chaiman, Tim Eddy added: “The safety record across the 2024 jumps racing season was unacceptable and the events of the final meeting at Ballarat were heartbreaking for all involved in the Victorian jumps racing community”.

Last month’s report linked jumping’s reprieve to a raft of safety measures, including the cessation of jumps racing at certain tracks, a contraction of the season in the quest for safe ground and increased oversight on safety compliance.

Meanwhile, just over the Tasman Sea, a very similar exercise has recently concluded. And if one needed any more evidence of the existential nature of these deliberations, consider this early sentence from the review’s executive summary:

“The scope of the review is to evaluate the future of jumps racing by examining scenarios in which it either continues or is discontinued”.

Again, the review came down in favour of continuation and prompted this joyous headline to an article by respected journalist Michael Guerin: ‘Jumps racing saved in New Zealand with bold new changes ahead’.

Noteworthy was the difference in tone and apparent motivation for the two studies. Whereas, in Victoria’s, horse welfare was front and centre, in New Zealand the focus was more on such aspects as revenue, employment and jump racing’s role as a second career for flat racers. Its approach to the welfare issue was muted: “It is well documented that jumps racing carries higher risks than flat racing, to both horses and jockeys. The figures however did not suggest to the Panel that jumps racing should be discontinued, but the Panel did agree that any additional safety measures should be identified and implemented”. The report gave a nod to “avoiding firm track conditions early in the jumps season” and noted that “even those who supported the continuation of jumps identified a concern about use of the whip during the races, especially at the end of the races after the last jump…when horses are tired”. Its main recommendations, however, centred on programming changes, promotional initiatives to raise the profile of jockeys, and various measures for their sourcing, (including, intriguingly, “a recruitment and licensing program to streamline the readiness of UK riders for racing in New Zealand”).

For Guerin, this emphasis is reflective of broader public attitudes in New Zealand where, he observes “many have farm ties and most city people probably don’t watch jumps racing as it is no longer in Auckland”.

Japanese jump racing is battling twin concerns of declining betting revenue and dwindling jockey numbers. The Japan Racing Association’s Takahiro Uno, Chair of the Asian Pattern Committee notes that its jump races were recently moved, as a result, from the major tracks to smaller venues. But there is a desire to protect the rich history of jumping – Japan’s premier jump race, the Nakayama Daishogai, is not far away from its centenary. Already, an apprentice system which is agnostic as to the age of the apprentice has been introduced, to incentivise flat riders to make the transition and a return of some jump races to the big metropolitan venues is under consideration.

Let us return home, to Europe. A survey of EMHF members revealed that jump racing can be found in no fewer than 13 of them. That’s the good news. The less good news is that decline and contraction is evident virtually across the board, and in two countries - Austria and Norway - jump racing has died out within the last 20 years.

In Germany, the downswing is precipitous.

Despite a 93% reduction in jump races since 2004, field sizes have plummeted to less than 4.5 runners. To Rudiger Schmanns, Racing Direktor at Deutscher Galopp the sport is in its last throes. What does he envisage in the next 10 years? “No races. No, riders, no horses and further animal welfare pressure”.

The picture in Italy is brighter – but not much.

In 2004, 728 individual horses started over the jumps; today that number is 212. Twenty years ago, one could enjoy jumping at 15 Italian tracks. Now, there is just Pisa, Trevisa and Merano left. The last-named remains a gem amongst European jumps courses, but is heavily propped up by incoming foreign-trained runners, mainly from the Czech Republic. Around half of Merano’s prize money goes abroad, and around half of that to the powerful Czech stable of Scuderia Aichner and Josef Vana jnr.

And, turning to Czech Republic on our European round-up, we detect the first green shoots of optimism.

While a reduction in scale is still apparent, it is far less pronounced than in the earlier countries. And the above tells but half the story, since, as has been noted, Czech-trained runners ply their trade in neighbouring countries with great success. Martina Krejci, General Secretary of the Czech Jockey Club observes: “Very many Czech trainers and owners start in jump races abroad. For example, this weekend in Wroclav (Poland), the Crystal Cup runners were almost all Czech”. Krejci anticipates a bounce-back will take place starting next year, with race numbers returning to their levels of 10 and 20 years ago. One of the biggest impediments to growth, though, is the dearth of jockeys.

It is as well to consider the Central European countries as a region, as well as individual territories, such is the level of international traffic of runners.

Polish statistics are distorted somewhat by the fact that, in the early part of this century, a number of jump races for half-breds were additionally run. These then ceased, and were supplanted with thoroughbred races, which drew liberally for their runners from neighbouring countries, such as Czech Republic. Notwithstanding this quirk, Polish jump racing, if not in rude health, is certainly faring better than most.

Sweden now flies the Scandinavian jump racing flag alone. The jumps are a distant memory in Denmark and the last hurdle race in Norway took place in 2022. Swedish jumping’s future is itself under intense scrutiny, explains Dennis Madsen, Racing Director of the Swedish Horseracing Authority, following the betting operator’s devastating decision no longer to take bets on this code of racing. For Madsen, though, jump racing’s problems are very largely replicated on the flat in Sweden, and he detects a frightening decline in horseracing the world over which he feels is both inexorable and inevitable. “Yes”, he concedes, “Cheltenham and Ascot and the Melbourne Cup still sell out, but these are merely the biggest icebergs, which will melt the slowest. The smaller countries will be erased before the bigger countries – but the bigger countries are melting as well”.

One can find jumping in Belgium, Channel Isles, Hungary, Slovakia and Switzerland, in some of which it is hanging on doggedly, but the scale of activity in these countries is even tinier – none runs more than 20 jump races annually.

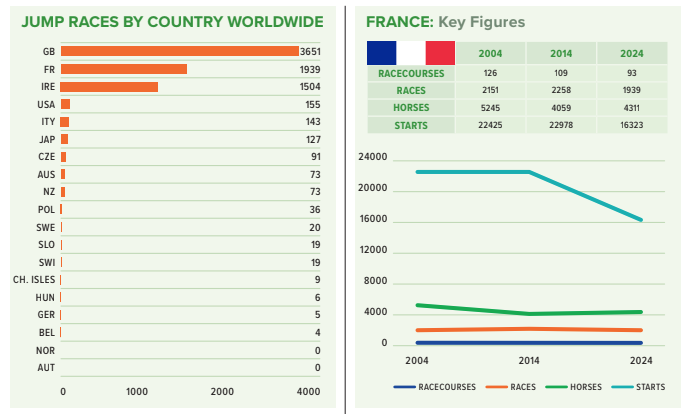

Which leaves Britain, Ireland bigger countries and France. The sheer scale of the dominance of the ‘big three’, and particularly of Britain, is vividly apparent from this chart. Between them, they account for over 90% of the world’s jump races. Nearly 8,000 jump races are run each year around the world and nearly half of these take place in Britain.

So, when considering the overall health of the jumps, most of our attention must be paid to this triumvirate.

France has seen just a modest 10% reduction in its jump races since 2004, where it is staged on 93 tracks today, compared with 123 tracks then. But the number of starts has fallen far faster, by more than one quarter, meaning that field sizes have gone from 10.4 down to 8.4.

Among the causes of this decline, Henri Pouret, Chief Operating Officer at France Galop cites the rise in French-breds being exported, a reduction in racecourses on security grounds due to a lack of volunteer staff and a shortage of jump jockeys, especially amateurs. However, the code remains an important part of the French racing product: “Jump racing and breeding are key in the horse racing landscape in France”, says Pouret. “t still represents one third of the races organised in France and of our different runners. There is a plan to restore Auteuil Racecourse which is the flagship of jump racing in France”.

“The main factor likely to influence the scale of jump racing in your country over the coming years, will be public perception and social license to operate regarding falls and fatalities”.

To invigorate the sport, Pouret would welcome the development of pony racing over jumps.

Ireland’s jumps industry is showing considerable resilience. The number of races has actually increased, but individual horses competing in those races and the aggregate number of starts are both down by over 10%, leading to average fields of a still healthy 11.5, compared with a whopping 13.8 twenty years ago. However, the metrics have improved in the most recent decade.

Jason Morris, Director of Strategy at Horse Racing Ireland, provides the context: “Ireland is in a more positive position than many jurisdictions as jump racing has grown over the past 10 years in line with HRI's strategic objective to become the global leader. The number of races and runners has increased while we have been able to maintain a very competitive average field size of 11.5 runners per race. Irish runners are consistently winning the majority of races at the Cheltenham Festival and an Irish trainer Willie Mullins was crowned British champion trainer for the 2023/24 jumps season. An attractive race programme, strong prize money, well attended race meetings and the continued success of Irish-trained runners are incentivising many international owners to have their jumps horses based in Ireland, while the Irish point-to-point sector continues to provide an invaluable nursery for developing young horses”.

“Our intention is that jumps racing will continue to grow in Ireland over the next 10 and indeed 20 years”.

“The biggest influencing factor and threat to Irish jumps racing is the potential decline of jumps racing in Britain given its importance as an export market for Irish horses and the symbiotic racing and breeding relationship between the two countries. A strong British jumps sector is vital for Irish racing”.

“In terms of invigorating jumps racing, there are concerns about the availability of sufficient horses going forwards and HRI is working on initiatives with the Irish Thoroughbred Breeders Association to ensure the continuing production of quality Irish-breds, including earlier participation on the racecourse for jumps-bred horses. The concentration of success in a shrinking number of very powerful yards is another area for focus. While we celebrate the success of our top trainers, we want to ensure that the grass roots continue to grow as well and that there is a strong pyramid supporting the upper echelons. We will therefore be looking at race planning measures to provide more opportunities for smaller trainers and owners to be competitive. Finally, equine welfare is very much at the forefront of everything HRI does, and we work very closely with the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board to ensure the highest standards of veterinary care and injury risk prevention”.

And a not dissimilar picture is apparent in the world’s jump racing capital, Britain. Again, there are more races today – 10% more over two decades. But, as we have seen in so many countries, the jump horse population and its preparedness to compete has fallen, by some 12%. The pressure on field sizes is more acute in Britain than in Ireland, having fallen from 10.2 (2004) to 8.2 today.

Let us turn to Richard Wayman, the British Horseracing Authority’s Director of Racing and Betting, for a perspective on these bald statistics.

“Although our numbers have remained relatively stable in more recent years, since 2004 there has been a 6.5% decline in the number of horses running at least once over Jumps during the course of the year.

There are many factors that will have contributed to that downward trend, not least the expansion and improvement of the all-weather programme on the Flat through the winter. It is only since 2006 that we have had floodlit meetings routinely staged throughout the core Jumps season and we believe that this change has had an impact on the number of horses running over obstacles.

We’ve also seen an increase in the number of Flat horses being sold to continue their careers overseas and that too has also meant fewer horses switching codes. The days of Jump trainers buying large numbers of horses off the Flat at the Horses in Training Sales in the autumn has become an increasingly distant memory as more and more horses are purchased to continue their Flat racing career elsewhere.

There have been some changes in the make-up of racehorse owners that, in all likelihood, have worked against Jumping. The number of sole owners has declined, with there being an increase in syndicates and racing clubs. Whilst some of those groups, of course, own horses over Jumps, the lower risk of injuries, the prospect of the horses being able to run more often and the potential to pick up more prize money has almost certainly worked in favour of the Flat. Indeed, it is interesting to see an increasing number of Jumps trainers evolving their own business models to include training Flat horses.

More generally, the difficult economic climate will have had a downward impact on racehorse ownership, as will the increasing urbanisation of society meaning that fewer people are involved with horses generally, again something that will have particularly worked against Jump racing”.

How would Wayman anticipate these numbers will look in 10 and 20 years' time?

“Although some of our numbers have been under pressure over the past decade or two, Jump racing remains incredibly popular with fans of the sport. The top 15 races in Britain for generating betting turnover all take place over Jumps. In addition, 37 of the top 50 betting races are also over obstacles.

Of the three race meetings that cut through into mainstream media in Britain – namely the Cheltenham Festival, the Grand National meeting, and Royal Ascot – two take place over Jumps. Our terrestrial broadcaster reports that their viewing figures are at their highest through the Jumps season.

Jump racing remains a hugely popular and much-loved sport that can thrive in the years ahead. That doesn’t mean that it will return to the levels of 20 years ago as we have to accept that the world has changed. However, with help from a mix of short- and longer-term measures, we believe that Jump racing can grow, and indeed thrive, over the course of the next decade and beyond”.

What would he like to see happen to invigorate Jump racing?

“A variety of measures, rather than one silver bullet, will all need to play a part in supporting our participants and racecourses to ensure that we collectively deliver a robust and vibrant sport in the years to come.

This will involve supporting the supply chain of Jump horses, continuing to invest in the mares’ programme and providing financial incentives to support the breeding of quality Jumping stock. It will require learning lessons about what has worked elsewhere and understanding whether those could be successfully applied in Britain, for example the earlier development of Jump horses such as in France, or the Novice Chase programme in Ireland.

We must make the ownership of Jump horses as attractive as possible. As well as investing in the overall experience, at a time of rising costs, making the financial equation more enticing for owners will be key to supporting the quality and quantity of our Jump horses. We have some brilliant Jumps trainers and, again, introducing steps that will assist them in attracting investment from owners, in particular building upon our increased investment that is being made into the Novice programme for both hurdlers and chasers, will be vital.

The race programme also has a role to play in ensuring that we can deliver an effective development pathway which provides promising young horses with the opportunities to help them fulfil their potential and provide the sport with its future stars.

And, of course, the development of exciting equine stars is critical to ensuring that Jump racing remains an attractive proposition for fans and customers, both new and existing. As a broad, overarching and final point, it obviously remains vital to maintain a strong and constant focus on all possible measures to improve the welfare and safety of our horses and riders, together with ensuring we provide a sport that is consistently more competitive and compelling at all levels”.

What, then, might we say in answer to our opening question? Well, first, it must be conceded that we have simply taken jump racing’s pulse – a full medical examination would be necessary to make secure pronouncements. But it might be safe to conclude the following.

Jump racing, while present in fewer locations than in the past, is still to be found in seventeen jurisdictions spread across four continents, and staged at over 200 racetracks.

Nearly half of all jump races are run in Britain, with over 90% in Britain, Ireland or France.

In the past 20 years, the number of jump races has fallen, but only by 3.5%, from a little over 8,000 races to a little under that figure.

The pool of horses taking part has shrunk significantly, by around 18%, from over 23,000 to around 19,000.

Further, these horses are tending to run less slightly frequently, with aggregate starts in jump races falling by over 20%. The average jumper now makes 3.55 starts per season, rather than 3.7.

Field sizes have come under pressure world-wide, as a consequence. There are, on average, two fewer horses in each jumps race – 8.6 compared with 10.6 in 2004.