EMHF - The state of jump racing around the world

Words - Paull Khan

What state of health is jump racing really in? For someone living in Britain, for example, the picture is a little confusing. On the plus side, interest levels in the sport relative to the flat seem never to have been higher – of the top British races by betting turnover, almost all are over obstacles. And no festival, Royal Ascot included, generates more anticipation and excitement than does Cheltenham. Then one considers Ireland and the merciless pummelling, which the Brits have become accustomed to, of the home team by Irish-trained horses at that very Festival. And France: you won’t find a topflight jumps card where the commentator’s mastery of French pronunciation will not be put to the test – such is the prevalence of French-bred imports.

But then, on the darker side of the coin, one cannot fail to register increasing societal unease. A growing unwillingness to accept the unavoidable reality of injuries and fatalities, however rare their occurrence. And views being expressed that these headwinds are not only serious – they may be terminal, with venerable trainers opining that jump racing in Britain will not outlive them. And we are aware of the swingeing contraction of jump racing in Australia, which gives those existential fears more weight.

So, your columnist set out on a journey of discovery – to try to find out the true state of health of jump racing globally.

The first thing I was struck by is how rare a bird jump racing is, globally speaking. There are vast tracts of this planet on which the sport simply does not exist. More troubling yet, in several parts of the world there are memories of a sport that once existed but that has now perished.

Take Canada. Ross McKague of the Canadian Graded Stakes Committee sets out the picture starkly. “We have never had, do not currently have, nor are there any plans for, any organized jump races in Canada.”

Similarly in South Africa. “Apart from one or two amateur jump races on the inside of the race course in the Eastern Cape at the now defunct Arlington Race course”, Arnold Hyde, Racing Control Executive at the National Horseracing Authority there explains, “I am not aware of jump races in an official capacity taking place here. I guess that there has not been a culture for jump racing in South Africa and with our dwindling horse population (hopefully with the latest import/export developments the trend is reversed), I cannot see this changing anytime soon”.

How about South America, then? Ignacio Pavlovsky, IFHA Technical Advisor for that continent, recalls there having been racing in Chile once upon a distant time. His research reveals that the last steeplechase was held there in 1986.

So where, outside Europe, is this elusive creature to be found? The green in the background maps gives the answer. The USA for one – but restricted to a ribbon of States in the East of the nation. We have mentioned Australia, where, within recent years, the sport has ceased in both Tasmania and South Australia and is only now to be found in Victoria. Then there’s New Zealand and Japan. And that, unless anyone corrects me, is just about it.

What is the scale of jump racing in these non-European countries, and how has it shifted in recent decades? Taking as our simple metric the number of jump races staged, we can see that Japan has virtually flat-lined over the past 20 years. USA, meanwhile, has seen a 20% decline, while New Zealand’s programme has all but halved and Australia’s has worse than halved.

Over that period, there has been a remarkable consistency in what has happened to average field sizes. In America, they have reduced by 13%, in New Zealand by 14% and in Australia by 15%, indicating that the pool of jump horses is contracting at a faster rate than the number of contests on offer. The average jump race in Australia attracts 8.2 runners; that in New Zealand 7.8 and that in the States just 6.5. Reducing field sizes is, in fact, a scourge of jump racing affecting virtually all of the world’s jumping nations.

And what of the future? Hearteningly, two recent reviews, the first in New Zealand and the second in Australia, have come down in favour of the continuation of the sport. The latter took place against the backdrop of calls from the local RSPCA for the closure of the sport in Victoria, following the deaths of three horses at the August meet in Ballarat.

September’s announcement from RV stated that “Due to the increase in fatal incidents across the 2024 jumps racing season, this year’s review will go beyond the standard process. A broader, whole-of-business approach will be adopted to analyse a broad range of metrics….The report and recommendations will consider the future viability of jumps racing in Victoria, and/or what further changes can be made to improve the safety record of the sport”.

RV’s Chaiman, Tim Eddy added: “The safety record across the 2024 jumps racing season was unacceptable and the events of the final meeting at Ballarat were heartbreaking for all involved in the Victorian jumps racing community”.

Last month’s report linked jumping’s reprieve to a raft of safety measures, including the cessation of jumps racing at certain tracks, a contraction of the season in the quest for safe ground and increased oversight on safety compliance.

Meanwhile, just over the Tasman Sea, a very similar exercise has recently concluded. And if one needed any more evidence of the existential nature of these deliberations, consider this early sentence from the review’s executive summary:

“The scope of the review is to evaluate the future of jumps racing by examining scenarios in which it either continues or is discontinued”.

Again, the review came down in favour of continuation and prompted this joyous headline to an article by respected journalist Michael Guerin: ‘Jumps racing saved in New Zealand with bold new changes ahead’.

Noteworthy was the difference in tone and apparent motivation for the two studies. Whereas, in Victoria’s, horse welfare was front and centre, in New Zealand the focus was more on such aspects as revenue, employment and jump racing’s role as a second career for flat racers. Its approach to the welfare issue was muted: “It is well documented that jumps racing carries higher risks than flat racing, to both horses and jockeys. The figures however did not suggest to the Panel that jumps racing should be discontinued, but the Panel did agree that any additional safety measures should be identified and implemented”. The report gave a nod to “avoiding firm track conditions early in the jumps season” and noted that “even those who supported the continuation of jumps identified a concern about use of the whip during the races, especially at the end of the races after the last jump…when horses are tired”. Its main recommendations, however, centred on programming changes, promotional initiatives to raise the profile of jockeys, and various measures for their sourcing, (including, intriguingly, “a recruitment and licensing program to streamline the readiness of UK riders for racing in New Zealand”).

For Guerin, this emphasis is reflective of broader public attitudes in New Zealand where, he observes “many have farm ties and most city people probably don’t watch jumps racing as it is no longer in Auckland”.

Japanese jump racing is battling twin concerns of declining betting revenue and dwindling jockey numbers. The Japan Racing Association’s Takahiro Uno, Chair of the Asian Pattern Committee notes that its jump races were recently moved, as a result, from the major tracks to smaller venues. But there is a desire to protect the rich history of jumping – Japan’s premier jump race, the Nakayama Daishogai, is not far away from its centenary. Already, an apprentice system which is agnostic as to the age of the apprentice has been introduced, to incentivise flat riders to make the transition and a return of some jump races to the big metropolitan venues is under consideration.

Let us return home, to Europe. A survey of EMHF members revealed that jump racing can be found in no fewer than 13 of them. That’s the good news. The less good news is that decline and contraction is evident virtually across the board, and in two countries - Austria and Norway - jump racing has died out within the last 20 years.

In Germany, the downswing is precipitous.

Despite a 93% reduction in jump races since 2004, field sizes have plummeted to less than 4.5 runners. To Rudiger Schmanns, Racing Direktor at Deutscher Galopp the sport is in its last throes. What does he envisage in the next 10 years? “No races. No, riders, no horses and further animal welfare pressure”.

The picture in Italy is brighter – but not much.

In 2004, 728 individual horses started over the jumps; today that number is 212. Twenty years ago, one could enjoy jumping at 15 Italian tracks. Now, there is just Pisa, Trevisa and Merano left. The last-named remains a gem amongst European jumps courses, but is heavily propped up by incoming foreign-trained runners, mainly from the Czech Republic. Around half of Merano’s prize money goes abroad, and around half of that to the powerful Czech stable of Scuderia Aichner and Josef Vana jnr.

And, turning to Czech Republic on our European round-up, we detect the first green shoots of optimism.

While a reduction in scale is still apparent, it is far less pronounced than in the earlier countries. And the above tells but half the story, since, as has been noted, Czech-trained runners ply their trade in neighbouring countries with great success. Martina Krejci, General Secretary of the Czech Jockey Club observes: “Very many Czech trainers and owners start in jump races abroad. For example, this weekend in Wroclav (Poland), the Crystal Cup runners were almost all Czech”. Krejci anticipates a bounce-back will take place starting next year, with race numbers returning to their levels of 10 and 20 years ago. One of the biggest impediments to growth, though, is the dearth of jockeys.

It is as well to consider the Central European countries as a region, as well as individual territories, such is the level of international traffic of runners.

Polish statistics are distorted somewhat by the fact that, in the early part of this century, a number of jump races for half-breds were additionally run. These then ceased, and were supplanted with thoroughbred races, which drew liberally for their runners from neighbouring countries, such as Czech Republic. Notwithstanding this quirk, Polish jump racing, if not in rude health, is certainly faring better than most.

Sweden now flies the Scandinavian jump racing flag alone. The jumps are a distant memory in Denmark and the last hurdle race in Norway took place in 2022. Swedish jumping’s future is itself under intense scrutiny, explains Dennis Madsen, Racing Director of the Swedish Horseracing Authority, following the betting operator’s devastating decision no longer to take bets on this code of racing. For Madsen, though, jump racing’s problems are very largely replicated on the flat in Sweden, and he detects a frightening decline in horseracing the world over which he feels is both inexorable and inevitable. “Yes”, he concedes, “Cheltenham and Ascot and the Melbourne Cup still sell out, but these are merely the biggest icebergs, which will melt the slowest. The smaller countries will be erased before the bigger countries – but the bigger countries are melting as well”.

One can find jumping in Belgium, Channel Isles, Hungary, Slovakia and Switzerland, in some of which it is hanging on doggedly, but the scale of activity in these countries is even tinier – none runs more than 20 jump races annually.

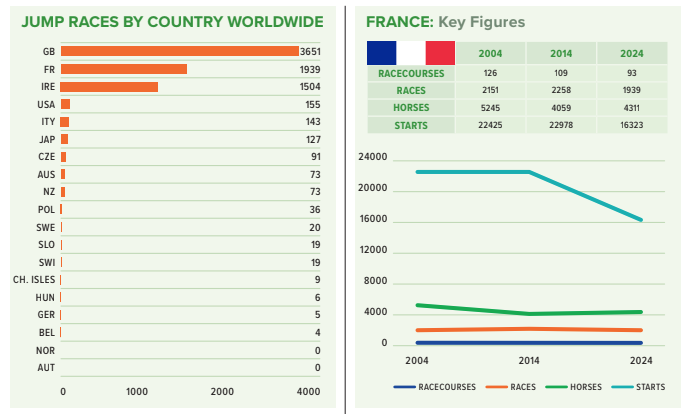

Which leaves Britain, Ireland bigger countries and France. The sheer scale of the dominance of the ‘big three’, and particularly of Britain, is vividly apparent from this chart. Between them, they account for over 90% of the world’s jump races. Nearly 8,000 jump races are run each year around the world and nearly half of these take place in Britain.

So, when considering the overall health of the jumps, most of our attention must be paid to this triumvirate.

France has seen just a modest 10% reduction in its jump races since 2004, where it is staged on 93 tracks today, compared with 123 tracks then. But the number of starts has fallen far faster, by more than one quarter, meaning that field sizes have gone from 10.4 down to 8.4.

Among the causes of this decline, Henri Pouret, Chief Operating Officer at France Galop cites the rise in French-breds being exported, a reduction in racecourses on security grounds due to a lack of volunteer staff and a shortage of jump jockeys, especially amateurs. However, the code remains an important part of the French racing product: “Jump racing and breeding are key in the horse racing landscape in France”, says Pouret. “t still represents one third of the races organised in France and of our different runners. There is a plan to restore Auteuil Racecourse which is the flagship of jump racing in France”.

“The main factor likely to influence the scale of jump racing in your country over the coming years, will be public perception and social license to operate regarding falls and fatalities”.

To invigorate the sport, Pouret would welcome the development of pony racing over jumps.

Ireland’s jumps industry is showing considerable resilience. The number of races has actually increased, but individual horses competing in those races and the aggregate number of starts are both down by over 10%, leading to average fields of a still healthy 11.5, compared with a whopping 13.8 twenty years ago. However, the metrics have improved in the most recent decade.

Jason Morris, Director of Strategy at Horse Racing Ireland, provides the context: “Ireland is in a more positive position than many jurisdictions as jump racing has grown over the past 10 years in line with HRI's strategic objective to become the global leader. The number of races and runners has increased while we have been able to maintain a very competitive average field size of 11.5 runners per race. Irish runners are consistently winning the majority of races at the Cheltenham Festival and an Irish trainer Willie Mullins was crowned British champion trainer for the 2023/24 jumps season. An attractive race programme, strong prize money, well attended race meetings and the continued success of Irish-trained runners are incentivising many international owners to have their jumps horses based in Ireland, while the Irish point-to-point sector continues to provide an invaluable nursery for developing young horses”.

“Our intention is that jumps racing will continue to grow in Ireland over the next 10 and indeed 20 years”.

“The biggest influencing factor and threat to Irish jumps racing is the potential decline of jumps racing in Britain given its importance as an export market for Irish horses and the symbiotic racing and breeding relationship between the two countries. A strong British jumps sector is vital for Irish racing”.

“In terms of invigorating jumps racing, there are concerns about the availability of sufficient horses going forwards and HRI is working on initiatives with the Irish Thoroughbred Breeders Association to ensure the continuing production of quality Irish-breds, including earlier participation on the racecourse for jumps-bred horses. The concentration of success in a shrinking number of very powerful yards is another area for focus. While we celebrate the success of our top trainers, we want to ensure that the grass roots continue to grow as well and that there is a strong pyramid supporting the upper echelons. We will therefore be looking at race planning measures to provide more opportunities for smaller trainers and owners to be competitive. Finally, equine welfare is very much at the forefront of everything HRI does, and we work very closely with the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Board to ensure the highest standards of veterinary care and injury risk prevention”.

And a not dissimilar picture is apparent in the world’s jump racing capital, Britain. Again, there are more races today – 10% more over two decades. But, as we have seen in so many countries, the jump horse population and its preparedness to compete has fallen, by some 12%. The pressure on field sizes is more acute in Britain than in Ireland, having fallen from 10.2 (2004) to 8.2 today.

Let us turn to Richard Wayman, the British Horseracing Authority’s Director of Racing and Betting, for a perspective on these bald statistics.

“Although our numbers have remained relatively stable in more recent years, since 2004 there has been a 6.5% decline in the number of horses running at least once over Jumps during the course of the year.

There are many factors that will have contributed to that downward trend, not least the expansion and improvement of the all-weather programme on the Flat through the winter. It is only since 2006 that we have had floodlit meetings routinely staged throughout the core Jumps season and we believe that this change has had an impact on the number of horses running over obstacles.

We’ve also seen an increase in the number of Flat horses being sold to continue their careers overseas and that too has also meant fewer horses switching codes. The days of Jump trainers buying large numbers of horses off the Flat at the Horses in Training Sales in the autumn has become an increasingly distant memory as more and more horses are purchased to continue their Flat racing career elsewhere.

There have been some changes in the make-up of racehorse owners that, in all likelihood, have worked against Jumping. The number of sole owners has declined, with there being an increase in syndicates and racing clubs. Whilst some of those groups, of course, own horses over Jumps, the lower risk of injuries, the prospect of the horses being able to run more often and the potential to pick up more prize money has almost certainly worked in favour of the Flat. Indeed, it is interesting to see an increasing number of Jumps trainers evolving their own business models to include training Flat horses.

More generally, the difficult economic climate will have had a downward impact on racehorse ownership, as will the increasing urbanisation of society meaning that fewer people are involved with horses generally, again something that will have particularly worked against Jump racing”.

How would Wayman anticipate these numbers will look in 10 and 20 years' time?

“Although some of our numbers have been under pressure over the past decade or two, Jump racing remains incredibly popular with fans of the sport. The top 15 races in Britain for generating betting turnover all take place over Jumps. In addition, 37 of the top 50 betting races are also over obstacles.

Of the three race meetings that cut through into mainstream media in Britain – namely the Cheltenham Festival, the Grand National meeting, and Royal Ascot – two take place over Jumps. Our terrestrial broadcaster reports that their viewing figures are at their highest through the Jumps season.

Jump racing remains a hugely popular and much-loved sport that can thrive in the years ahead. That doesn’t mean that it will return to the levels of 20 years ago as we have to accept that the world has changed. However, with help from a mix of short- and longer-term measures, we believe that Jump racing can grow, and indeed thrive, over the course of the next decade and beyond”.

What would he like to see happen to invigorate Jump racing?

“A variety of measures, rather than one silver bullet, will all need to play a part in supporting our participants and racecourses to ensure that we collectively deliver a robust and vibrant sport in the years to come.

This will involve supporting the supply chain of Jump horses, continuing to invest in the mares’ programme and providing financial incentives to support the breeding of quality Jumping stock. It will require learning lessons about what has worked elsewhere and understanding whether those could be successfully applied in Britain, for example the earlier development of Jump horses such as in France, or the Novice Chase programme in Ireland.

We must make the ownership of Jump horses as attractive as possible. As well as investing in the overall experience, at a time of rising costs, making the financial equation more enticing for owners will be key to supporting the quality and quantity of our Jump horses. We have some brilliant Jumps trainers and, again, introducing steps that will assist them in attracting investment from owners, in particular building upon our increased investment that is being made into the Novice programme for both hurdlers and chasers, will be vital.

The race programme also has a role to play in ensuring that we can deliver an effective development pathway which provides promising young horses with the opportunities to help them fulfil their potential and provide the sport with its future stars.

And, of course, the development of exciting equine stars is critical to ensuring that Jump racing remains an attractive proposition for fans and customers, both new and existing. As a broad, overarching and final point, it obviously remains vital to maintain a strong and constant focus on all possible measures to improve the welfare and safety of our horses and riders, together with ensuring we provide a sport that is consistently more competitive and compelling at all levels”.

What, then, might we say in answer to our opening question? Well, first, it must be conceded that we have simply taken jump racing’s pulse – a full medical examination would be necessary to make secure pronouncements. But it might be safe to conclude the following.

Jump racing, while present in fewer locations than in the past, is still to be found in seventeen jurisdictions spread across four continents, and staged at over 200 racetracks.

Nearly half of all jump races are run in Britain, with over 90% in Britain, Ireland or France.

In the past 20 years, the number of jump races has fallen, but only by 3.5%, from a little over 8,000 races to a little under that figure.

The pool of horses taking part has shrunk significantly, by around 18%, from over 23,000 to around 19,000.

Further, these horses are tending to run less slightly frequently, with aggregate starts in jump races falling by over 20%. The average jumper now makes 3.55 starts per season, rather than 3.7.

Field sizes have come under pressure world-wide, as a consequence. There are, on average, two fewer horses in each jumps race – 8.6 compared with 10.6 in 2004.