The latest published research on pre-biotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge

Article by Sorcha O’Connor

We all know that winning races depends on far more than what happens on the day at the track. The health, fitness, and mentality of a racehorse are built long before race day. Increasingly, science tells us that one of the most powerful drivers of performance is hidden inside the horse: the gut. Understanding this hidden half of the body is key to understanding health and disease.

Gut health is central not only to digestion but also to energy supply, recovery, immunity, behavior, and resilience against disease (O’Brien et al., 2022). When the gut is compromised, the impact is felt in poor performance, poor recovery, and increased veterinary bills. On the other hand, when the gut is healthy, horses can perform at their best more consistently.

In this article, we explore the role of gut health in racehorse performance, the risks posed by modern feeding practices, and the latest published research including recent field trials carried out on a novel gut supplement containing pre-biotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

The Gut’s Microbiome and Performance

Unlike us, horses can digest fiber. Up to 70% of a racehorse’s energy can come from the fermentation of fiber in the hindgut, where microbes break it down into volatile fatty acids that fuel endurance and sustained performance. A healthy hindgut microbiome also contributes to the synthesis of B-vitamins (vital for energy metabolism and red blood cell production), it supports immune function and plays a role in hormone balance and even a horse’s behavior (Kauter et al., 2019). Although we are only beginning to understand the many functions of the horse’s microbiome, we do know how to fuel it with a diversified, fiber-based diet (Raspa et al., 2024).

Recent research highlights how much gut health influences a horse’s career. The Well Foal Study at the University of Surrey, UK followed Thoroughbred foals from birth to three years of age and found that those with more diverse gut microbiota early in life experienced fewer illnesses and went on to have more successful racing careers (Leng et al., 2024). This connection between gut diversity, health, and future performance directly shows the importance of looking after gut health from the very start of a racehorse’s life

For trainers, the practical implication is clear: a horse’s ability to perform at its peak depends on the stability and balance of its gut microbiome. A compromised gut means reduced energy extraction, more risk of conditions like colic and laminitis, and behavioral changes such as nervousness or lack of focus (Boucher et al., 2024).

Risks of Modern Training Diets

The natural diet of the horse is based on grazing and high-fiber forages. Modern training, however, demands higher energy intake than forage alone can provide. This has led to the widespread use of cereals and high-starch concentrates. While effective at delivering energy quickly, they also pose risks when fed in large amounts.

Studies show that feeding more than 5.5 - 11lbs (2.5–5kg) of cereal per day increases the risk of colic nearly fivefold. Horses fed more than 6lbs (2.7kg) of oats daily were almost six times more likely to colic (Tinker et al., 1997; Hudson et al., 2001). These figures are illustrated below.

2.5 – 5 kg of cereal per day

= 4.8 x colic risk

>5 kg of cereal per day

= 6.3 x colic risk

2.7 kg of oats per day

= 5.9 x colic risk

Similarly, research on equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) shows that feeding more than 0.07oz (2g) of starch per kilogram of bodyweight per meal raises the risk of squamous ulcers by over threefold (Luthersson et al., 2009). This is illustrated in terms of scoops in Figure 3 below (based on average starch levels in a racehorse cube or muesli).

1102lbs (500kg)

Why? Because the horse’s digestive anatomy is poorly adapted to digest large starch meals. Horses produce no amylase in their saliva, and their stomach and small intestine, the sites of starch digestion, are relatively small. When there is an overload of cereal, the starch bypasses these sections and enters the hindgut, where it disrupts microbial fermentation (Julliand & Grimm, 2017). The result is increased acidity, microbial imbalance (dysbiosis), and a cascade of problems ranging from ulcers and colic to poor recovery and unpredictable behavior (Bulmer et al., 2019).

On top of diet, the stresses of a modern racehorse’s life: transport, intense training, and routine veterinary interventions put further pressure on the microbiome. Each of these factors can disrupt gut balance, setting the stage for both health issues and reduced performance (Mach et al., 2020).

Supporting a Healthy Gut

Despite these risks, trainers have good tools to support gut health. The first step is to respect the horse’s natural digestive design:

Forage first: Provide ad lib hay or haylage where possible to keep the digestive system functioning as nature intended. Offering at least a small bit of hay before the morning hard feed has recently been shown to slow gastric emptying meaning a slower, steadier arrival of grain to the gut to allow for better digestion (Jensen et al., 2025). This small amount of hay can create a fibrous mat in the stomach that acts as a buffer against gastric acid. This reduces the risk of acid splash onto the more sensitive squamous region of the stomach lining, thereby helping to protect against ulceration.

Small, frequent meals: Avoid overloading the stomach and small intestine with large concentrate feeds. Horses are trickle feeders, designed to eat little and often.

Controlled starch intake: Keep starch levels per meal controlled as described in Figure 2 to not overwhelm the digestive capacity of the gut.

Consistency: Avoid sudden changes in feed or forage sources, which can disrupt microbial populations. The horse’s digestive system needs a time period of at least 10-14 days to adjust to a change in their diet.

Beyond feeding management, nutritional science has delivered additional aids. These should only be considered once the main dietary and forage management is in order.

Prebiotics — specific fibers that serve as food for beneficial microbes and help support microbial balance.

Probiotics, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (a yeast proven to improve fiber digestion), or Saccharomyces boulardii can stabilize the hindgut in horses on high-starch diets.

Postbiotics — more recently, attention has turned to these beneficial compounds produced during fermentation, which can positively influence gut function and whole-body health.

New Research: Postbiotics and Faecal pH

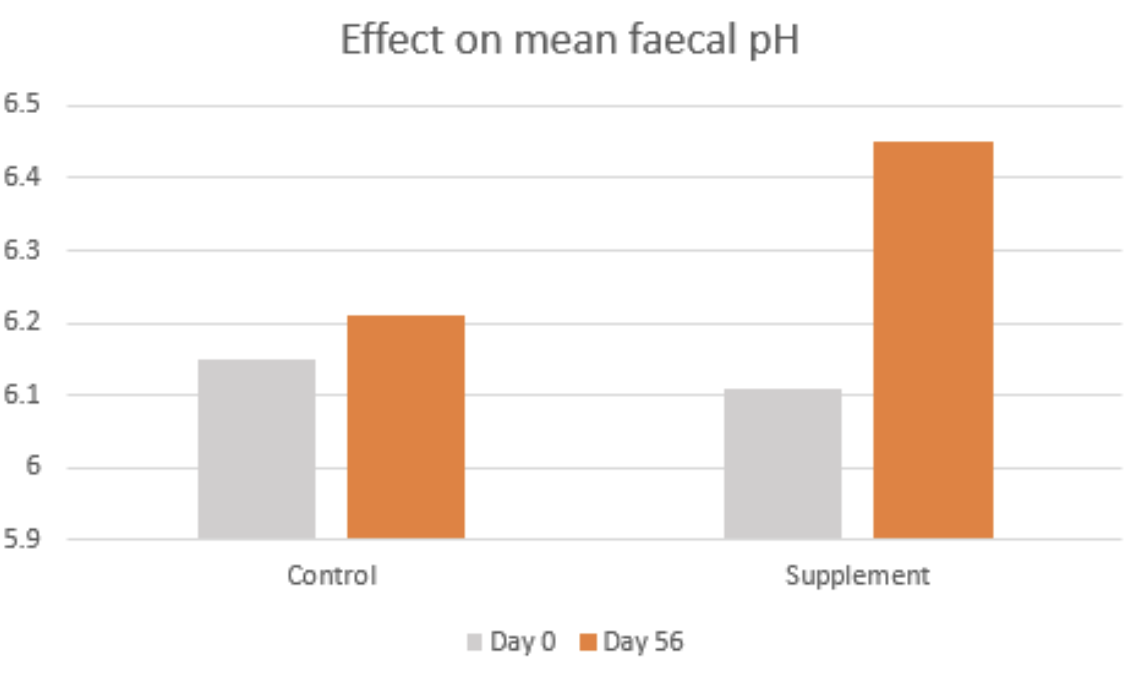

Recent field research involving Thoroughbreds in training has provided new evidence on how targeted nutritional support can shape the gut environment. A novel gut supplement, a nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins, and a fermented yeast postbiotic was trialled on 34 Thoroughbreds in training over an eight-week period. The horses in the trial receiving this supplement showed a significant reduction in faecal pH compared to the control group as shown in Figure 4, indicating a healthier, more stable hindgut environment (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

Figure 4: The effect on faecal pH over time in both groups in the trial

Why does this matter? Faecal pH has been shown as a practical measure for assessing the condition of the rest of the hindgut (Costa et al, 2015). High acidity (low pH) in the hindgut signals excess starch fermentation and an increased risk of acidosis, colic, and poor nutrient absorption. By reducing faecal pH, the supplement supported a more balanced microbial population and more efficient fiber digestion.

For trainers, the benefits of a more stable hindgut:

Consistent energy supply: Better fiber fermentation means a more reliable source of slow-release energy, supporting stamina.

Reduced digestive upset: Lower risk of colic, acidosis, loose droppings, etc.

Improved recovery: A healthier gut environment supports nutrient absorption and immune resilience.

Mental focus: Balanced microbiota have been linked to calmer behavior and reduced stress responses.

This research positions postbiotics as a promising new tool in equine nutrition. While probiotics deliver live organisms and prebiotics provide fuel for the microbiome, postbiotics are the beneficial by-products themselves. They can modulate inflammation, support immunity, and stabilize the gut environment without the storage and survival challenges associated with live probiotics (Valigura et al., 2021).

Beyond Supplements

While supplements are valuable, they are only one small piece of the horse’s diet. Trainers should consider gut health as a whole-yard management issue. Consistency of forage supply is key. Sudden changes in hay or haylage batches can disrupt microbial populations. Hydration must be monitored closely, as dehydration increases the risk of impaction colic. Stress management, from minimising unnecessary transport to keeping consistent training plans and providing adequate turnout or downtime, also play key roles in keeping the gut stable.

Veterinary practices should also be considered. Antibiotics, while sometimes necessary, are known to disrupt the gut microbiome for months after use. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use and working with vets to target treatments carefully will help protect long-term gut health and performance. The gut microbiome is made up of thousands of bacteria and other microbes that can be destroyed by an antibiotic course and may take months to recover. Antibiotics should only be used when truly necessary. When they are required, ensure the horse is on a high-quality, fiber-rich diet to help keep the gut supported during this stressful period (Collinet et al., 2021).

Looking Ahead – Gut Health as a Competitive Edge

Equine microbiome research is still in its early stages, but the message is already clear, gut health is tightly connected to race performance. Trainers who prioritise digestive stability through smart feeding, careful management, and targeted nutritional support will not only reduce veterinary costs but also gain a competitive advantage on the track.

The next generation of supplements, including those using postbiotic technology, offers exciting potential to further support racehorses in training. By nurturing a healthier hindgut environment, these tools can help horses get more from their feed, recover faster, and maintain focus under the pressures of racing.

The race truly does start in the gut. By trusting and supporting that hidden engine, trainers can help their horses reach the finish line stronger, healthier, and more consistent than ever.

The gut microbiome of a foal as early as one month old plays a key role in shaping its future health and performance. The foal begins its colonisation through contact with the microbiota of the mare’s vaginal and skin surfaces and its surrounding environments. Its gut microbiome reaches a relatively stable population by approximately 60 days in age. For this reason, sourcing well-reared, high-quality stock is essential to give young horses the best start. A healthy microbiome should be supported throughout the racehorse’s career to give him the best chance of success.

For hundreds of years, the Thoroughbred industry has focused on genetics, breeding from elite bloodlines to produce the fastest, strongest, and most resilient horses. Emerging research, however, suggests another layer of inheritance that may have been overlooked. A foal acquires much of its gut microbiota from its dam, meaning these microbes could prove just as influential as pedigree in determining future health and performance.

References

Boucher, L., Leduc, L., Leclère, M. & Costa, M.C. (2024) ‘Current understanding of equine gut dysbiosis and microbiota manipulation techniques: comparison with current knowledge in other species’, Animals (Basel), 14(5), p.758. doi:10.3390/ani14050758.

Bulmer, L.S., Murray, J.A., Burns, N.M. et al. (2019) ‘High-starch diets alter equine faecal microbiota and increase behavioral reactivity’, Scientific Reports, 9(1), p.18621. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54039-8.

Collinet, A., Grimm, P., Julliand, S. & Julliand, V. (2021) ‘Sequential modulation of the equine fecal microbiota and fibrolytic capacity following two consecutive abrupt dietary changes and bacterial supplementation’, Animals (Basel), 11(5), p.1278. doi:10.3390/ani11051278.

Costa, M.C., Silva, G., Ramos, R.V. et al. (2015) ‘Characterization and comparison of the bacterial microbiota in different gastrointestinal tract compartments in horses’, Veterinary Journal, 205(1), pp.74–80. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.03.018.

Hudson, J.M., Cohen, N.D., Gibbs, P.G. & Thompson, J.A. (2001) ‘Feeding practices associated with colic in horses’, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(10), pp.1419–1425. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.219.1419.

Jensen RB, Walslag IH, Marcussen C, Thorringer NW, Junghans P, Nyquist NF. The effect of feeding order of forage and oats on metabolic and digestive responses related to gastric emptying in horses. Journal of Animal Science. 103:skae368. doi: 10.1093/jas/skae368. PMID: 39656737; PMCID: PMC11747703.

Julliand, V. & Grimm, P. (2017) ‘The impact of diet on the hindgut microbiome’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 52, pp.23–28. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2017.03.002.

Kauter, A., Epping, L., Semmler, T. et al. (2019) ‘The gut microbiome of horses: current research on equine enteral microbiota and future perspectives’, Animal Microbiome, 1(1), p.14. doi:10.1186/s42523-019-0013-3.

Leng, J., Moller-Levet, C., Mansergh, R.I. et al. (2024) ‘Early-life gut bacterial community structure predicts disease risk and athletic performance in horses bred for racing’, Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.17124. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-64657-6.

Luthersson, N., Nielsen, K.H., Harris, P. & Parkin, T.D. (2009) ‘Risk factors associated with equine gastric ulceration syndrome (EGUS) in 201 horses in Denmark’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 41(7), pp.625–630. doi:10.2746/042516409x441929.

Mach, N., Ruet, A., Clark, A. et al. (2020) ‘Priming for welfare: gut microbiota is associated with equitation conditions and behavior in horse athletes’, Scientific Reports, 10(1), p.8311. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65444-9.

O’Brien, M.T., O’Sullivan, O., Claesson, M.J. & Cotter, P.D. (2022) ‘The athlete gut microbiome and its relevance to health and performance: a review’, Sports Medicine, 52(Suppl 1), pp.119–128. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01785-x.

O’Connor, S. & Mulligan, F. (2024) ‘A field study of a novel nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins, and postbiotics’ effects on equine gut acidity’, presented at the 28th Congress of the European Society of Veterinary and Comparative Nutrition, Dublin, 9–10 Sept.

Raspa, F., Vervuert, I., Capucchio, M.T. et al. A high-starch vs. high-fiber diet: effects on the gut environment of the different intestinal compartments of the horse digestive tract. BMC Veterinary Research 18, 187 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03289-2

Tinker, M.K., White, N.A., Lessard, P. et al. (1997) ‘Prospective study of equine colic risk factors’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 29(6), pp.454–458. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03158.x.

Valigura, H.C., Leatherwood, J.L., Martinez, R.E., Norton, S.A. & White-Springer, S.H. (2021) ‘Dietary supplementation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product attenuates exercise-induced stress markers in young horses’, Journal of Animal Science, 99(8), skab199. doi:10.1093/jas/skab199.