Alan Balch - Turning Point

Article by Alan Balch

November 1, 1986, is the date the Breeders’ Cup was assured of a viable future. The first one at Santa Anita. This year at Del Mar will be the 42nd edition.

Its founding visionary, John R. Gaines, had repeatedly emphasized the importance and potential of the Breeders’ Cup for marketing racing: to stimulate its massively increased sporting awareness through the televised spectacle of our championships.

Yet, mysteriously, its early leaders had chosen two of the least telegenic tracks in America for the first editions: Hollywood Park and Aqueduct.

I’m one of the few still left in racing (or even alive) who was in the midst of that mystery at the time. In fact, it was my responsibility at Oak Tree Racing Association and Santa Anita to prepare and lead the presentations of our proposals for the site selectors, prior to 1984, and again for 1986.

That committee (which included several Thoroughbred paragons including Nelson Bunker Hunt and John Nerud) had locations across the entire nation to consider. But California tracks in those days were perennial leaders in attendance and handle and – most important – reliably nice November weather. Most everyone thought the inaugural choice came down to the southland rivals, Hollywood Park and Santa Anita.

So, in 1982 and early 1983, Oak Tree emphasized both our statistical superiority and Santa Anita’s pending hosting of the 1984 Olympic Games Equestrian Sport: the potential worldwide double of exceptional excellence for that year which would be provided for its launch. And I vividly remember Oak Tree President Clement Hirsch proclaiming to the selectors, “it has never rained on that weekend at Santa Anita,” which was true, but tempted fate. It did rain that weekend, in 1983, the year before the first one. (It has at least once since then, too.)

Hollywood Park emphasized . . . well, Hollywood . . . with Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant, and their fellow stars, along with the 20th Century movie lot. Plus, a pile of cash in earnest to assist the fledgling effort. It was chosen for the premier.

Naturally, we the losers were chagrined. Even angry. Oak Tree’s brass at the time privately suggested “never again.” Personally, and not for the last time, through the cloudy experience of bitter disappointment, I dimly saw some advantages of not being “first” at such an undertaking. Those few of us still around who witnessed that day at Hollywood Park will remember what I mean, particularly in terms of “operational challenges,” to put it much more politely than deserved.

Ultimately, and with far more reluctance than anyone would now admit, Oak Tree’s leadership decided to try again in 1985, to receive “the honor” of hosting in 1986. Breeders’ Cup administration in those days was nothing like the independent behemoth it has grown to become. Then, it relied very heavily on existing host track management, the track’s own marketing, operations, and racing expertise. It had no choice but so to do. But with that reliance came plenty of tension, most of it healthy, as the host track not only wanted to protect its own prerogatives, but also the interests of local fans, owners, and trainers. Breeders’ Cup, quite rightly, insisted on proper accommodations and recognition of all those who put up the multi-million-dollar purses – the breeders and their constituencies.

As part of our effort to win that year, Oak Tree sent me to meet with Mr. Hunt at his Texas spread, the famous Circle T, not far from DFW airport. That was an early morning I’ll never forget. “Bunker” arrived by himself to pick me up at the airport curb, driving his (old) Cadillac. “Son, I hope you’re not hungry, because we’re going to the farm first to see my horses.” He wasn’t exactly lithe, you know, but he gave me my own workout that day: we walked back and forth with each set, he describing their individual quirks and pedigrees in detail, watching them gallop or work. It was all in his head, without pause: he loved the game, he loved those horses, and knew both deeply. I was a “suit” in those days, but I saw the essence of racing in a new way. At the elbow of one of its greatest advocates. I learned way, way more than I had ever expected.

Then, onto the local greasy spoon for grits and whatever, with Bunker and his local mates yucking it up . . . that was the atmosphere for my pitch.

I can’t remember now if we had any real competition . . . we were coming off not just a highly successful Olympic Games effort, but also our Fiftieth Anniversary season where we drew our single-day record crowd of over 85,000, averaging nearly 33,000 per racing day.

If you look back now at the videos of the races that first Santa Anita Breeders’ Cup Day [https://breederscup.com/results/1986?tab=results], you can see what those truly mammoth crowds looked like. Official attendance was just under 70,000, easily a new record, as was the handle. Unlike today, however, official crowd numbers significantly understated attendance . . . since only those passing through a turnstile were counted, leaving out large numbers of backstretch personnel, as well as all the kids. The television spectacle that only Santa Anita can offer was in full, crystal-clear view.

The financial future of Breeders’ Cup was finally assured.

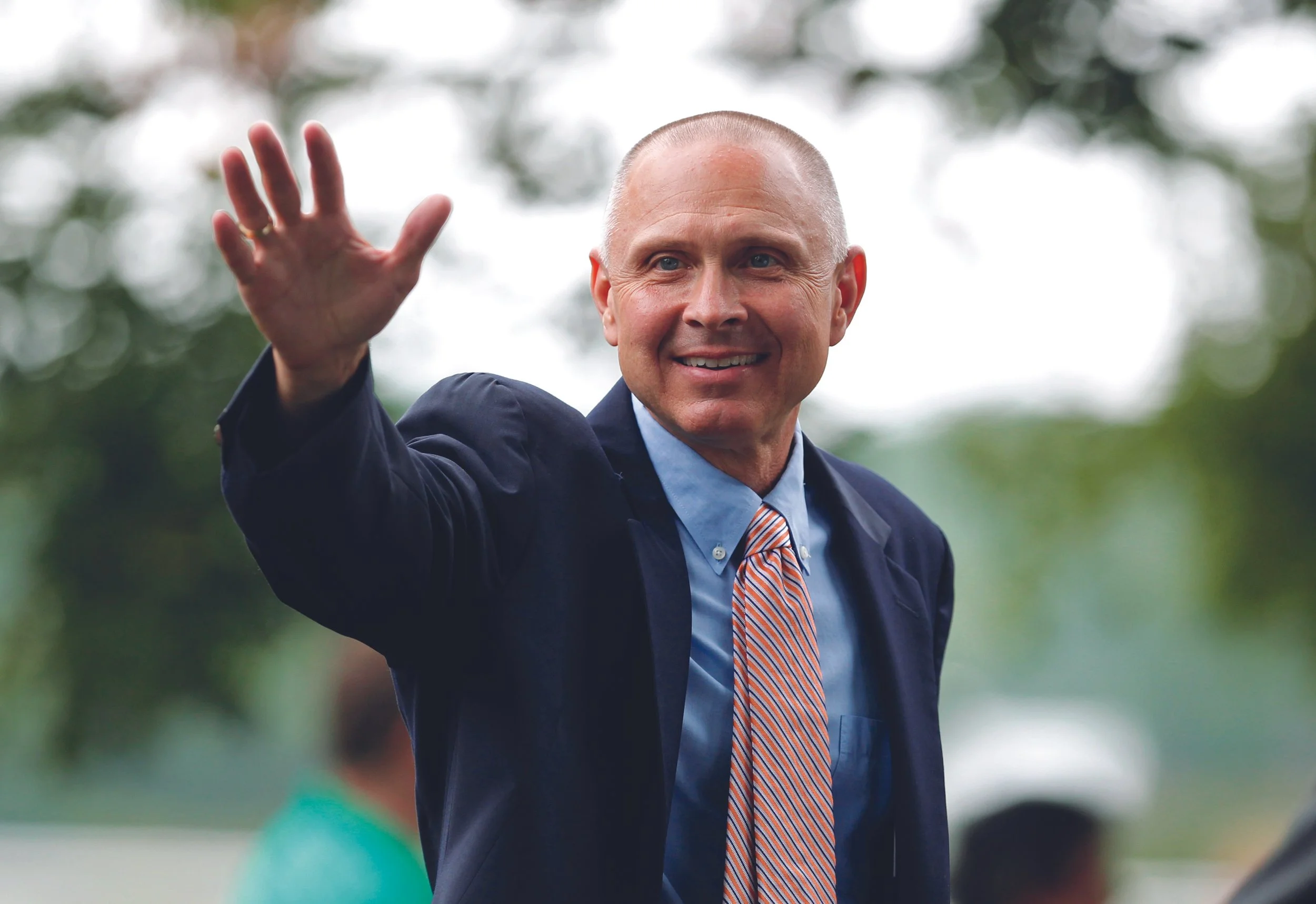

Rusty Arnold’s second wind

Article by Alicia Hughes

It had been a good run, Rusty Arnold told himself. More than good, actually.

Since the time he took out his trainer’s license in 1975, the Kentucky native had plied his trade with as much integrity as any conditioner in the Thoroughbred industry. There were the typical hardships that are part and parcel when one’s vocation hinges on the health of 1,000-pound equine athletes. But there were plenty of successes as well for the third-generation horseman, including his distinction of being your favorite trainer’s favorite trainer, a status earned through years of having his insight sought by both inquisitive up-and-comers and stalwarts like the late Christophe Clement.

He had won Grade 1 races. He had established himself as a consistent force in Kentucky and New York - two circuits that run constant litmus tests on one’s aptitude. So, when he saw his numbers dwindling about 10 years ago in terms of the horses coming into his care and results produced on the track, Arnold told his wife, Sarah, the time had come for them to start thinking about what the winding down process would look like for the barn.

Because when you’re five decades into your career, and you’re a not a trainer with 100-plus head backed by one-percenter clientele providing a steady pipeline of blue-blooded stock, it would be foolish to think the best years of your professional life were about to manifest on the heels of one of your most disheartening seasons. That’s the sort of comeback that only exists on the pages of sentimental scripts, not in the what-have-you-done-for-me-lately reality of competitive landscapes

Right?

“Around 2015…we didn’t have a good year. We had probably gone down to less than 30 horses, the lowest number we’d had in about 30 years, and I told Sarah, ‘I’ve had a wonderful run, but the good ones have stopped coming and we better be prepared to downsize and ride off into the sunset’,” Arnold recalled. “We weren’t thinking of giving it up, but we were thinking, okay we’ll have this one barn right here (at Keeneland) and know we won’t be in the highlight anymore. We’ll have to cut back a little bit.

“And then, all at once….”

Horsemen often joke about how fate responds when they attempt to plan long-term. From the moment Arnold started entertaining the notion of paring down his presence in the sport that has been his lifeblood, the universe began laughing in his face - and hasn’t stopped since.

Longevity in and of itself is not an unusual career trait for Thoroughbred trainers, especially in an industry where success is more the slow burn variety rather than overnight. What is uncommon, particularly for modest-sized barns trying to maintain numbers in the era of the super trainer, is the kind of resurgence Arnold is experiencing at a time when many horsemen of similar ilk are battling to keep from being squeezed out.

In 2025, his 50th year of conditioning horses under his name, George R. “Rusty” Arnold II has defied the metrics that say he is in the twilight of his profession. Heading into October, he had already established a career high for single-season earnings at $4.7 million and counting, topping the mark of more than $4.3 million he set for himself just one year ago. In the wake of that soul-searching 2015 season that saw him win just 20 races – his fewest total in more than 30 years – Arnold’s barn has generated at least $2.2 million in earnings in nine of the last ten years with 34 of his 108 career graded stakes victories coming in the past decade.

To put the remarkable nature of the trajectory Arnold is on into perspective, consider he was saddling starters even before the legend that was D. Wayne Lukas changed the game forever by switching his focus strictly to Thoroughbreds in the late 1970s. While he hasn’t had the elite-level resources boasted by such veteran Hall of Famers as Bill Mott, Bob Baffert, Steve Asmussen, and Todd Pletcher, what Arnold does have is a loyal base of owners like G. Watts Humphrey and the Bromagen family who know they are putting their faith in a trainer that unfailingly walks the walk when it comes to hands-on horsemanship.

His program isn’t built around chasing Triple Crown races and he has yet to hold Breeders’ Cup hardware above his head. When it comes to achievements that demand a rarified skillset, however, Arnold’s enduring ability to keep cranking his bar of success into a higher stratosphere is among the most extraordinary.

“I feel like I’m what they call in golf a journeyman. I’ve never won a major, but always played well,” said Arnold, who headed into the 2025 Keeneland Fall meet tied with Mott as the track’s all-time winningest trainer with 307 victories. “After 50 years, I think one of the things I’m proudest of is the people I’ve worked for a long time. I’ve had a lot of people who have stuck with me a long time.

“I’m not a Hall of Fame trainer. I don’t have a Hall of Fame career. But they’ve entrusted us to do what is best for their horse, and we’ve tried really hard to do that. We’ve always tried to err on the side of the horse. And what’s the old saying…nobody commits suicide with a 2-year-old who can run in the barn. So, then all at once we had a bunch of good horses. And it’s just been fabulous.”

Among the proteges this season who have testified to Arnold’s reputation as one of the best pure horsemen in the game is BBN Racing’s Kilwin, winner of the Grade 1 Test Stakes, multiple graded stakes winner Echo Sound, and Grade 3 victress Daisy Flyer – all of whom prevailed at the ultimate proving ground that is Saratoga Race Course.

With nearly 2,000 career victories to his credit and a shedrow that has produced more than $91 million in earnings, the 70-year-old Arnold has long stopped having to prove anything to anyone. That hasn’t stopped him from repeatedly reminding his brethren of what he and his team are capable of when given a modicum of talent to work with and the freedom to lean into his tried-and-true philosophies.

When Lyndsay Delello joined Arnold as an assistant nearly six years ago, she quickly discovered why job openings with the Paris, Ky born trainer were few and far between.

Whether one is visiting his flagship barn on Rice Road at Keeneland or walking down the shedrow his charges occupy on the Churchill Downs backstretch, the faces helping Arnold steer the ship rarely change – including his famed barn cat population headed by the venerable orange tabby, Chester. Shifts in the staff payroll are an outlier rather than a regular occurrence, due in no small part to that fact Arnold makes sure the dynamic in his barn is such that trust and recognition goes both ways for everyone.

“Before I started working here, everyone was like ‘The best job in Kentucky is with Rusty Arnold. You’ll never get it, but it’s the best job in Kentucky,’” Delello said. “That’s been his reputation. There are a bunch of guys who have been with Rusty for years. Riders, everyone, it’s the same. We really don’t have much of an employee turnover. He listens to our opinions and what I love too is he’s here every morning. He’s putting his hands on every horse.”

“There are some trainers where it’s like ‘I’m the boss, you do this,’” added Sarah Arnold, also known as the heartbeat of the operation. “Even with our riders, they’ll be getting on the horses, and they’ll say, ‘Do you think Rusty will let me try this?’. Most of the time, he’ll listen to people and their opinions on the horses. He takes it all in…and he’s not afraid of strong women.”

The standard of care in his barn and the dedication from those delivering it are not the only things that haven’t wavered throughout Arnold’s career.

The “old school” label is one the former University of Kentucky pre-vet student wears like a badge of honor. While he is savvy enough to evolve with the changing dynamics of the sport, the level of attention Arnold dispatches to each of his horses and the way he determines the most auspicious path for each is, at its core, the same now as it was when he notched his first stakes win in the 1976 Neptune Handicap at River Downs with Fleeting North.

“Some of the therapies and technologies that people use on the horses he’s open to but it’s mostly just basic horsemanship,” Sarah Arnold said of her husband’s training techniques.

The number of horses in his career currently sits around 50, a figure Arnold says is the sweet spot that allows him to lay eyes on every runner he is tasked with honing. Patience is the barn’s North Star as well as tailoring training to the individual, not the other way around. And while he doesn’t shirk the technical and veterinary advancements that have made some aspects of training easier, Arnold is still one to lean first and foremost on giving a horse time – a seemingly simple conviction, but one that can get lost in the modern-day focus of getting black-type on the resumes of well-pedigreed babies to set them up for careers in the breeding shed.

Exhibit A to the above came in 2019 when Calumet Farm sent Arnold a homebred son of Twirling Candy named Gear Jockey, a talented individual but one who needed a deft hand to get him placed in the right spots competitively and held together physically. After breaking through to earn his first graded score in the 2021 $1 million Turf Sprint Stakes (G3) at Kentucky Downs, the bay horse went through an eight-race losing skid and setbacks, including being sidelined for nearly eight months at one point.

Not only was Arnold able to get Gear Jockey back to the races, but he received the ultimate validation for giving his charge every chance when he captured the Turf Sprint at Kentucky Downs for a second time in 2023, besting a field that included eventual Grade 1 winner Cogburn.

“I feel like Gear Jockey was the best training job I ever did,” Arnold said. “He had his issues, but he won two $1 million races which was hard to do with a horse like him. He had a lot of issues, but when we’d get him over there when he was right, he was a really good horse.

“I’m not saying you don’t make some changes along the way because you do. But I sat around guys like Allen Jerkens and Shug McGaughey and Bill Mott, and you watch what everyone else does,” Arnold continued. “I never worked under a big trainer, I worked under my father for a while…but the rest of the time I picked it up from people. The one philosophy is just, take care of your horse, get him sound and happy. Don’t try and overdo it or overthink it. If you’ve done something that has worked for 25 years and you hit a bad time, you just stick to your guns. Get them healthy and they’ll run for you.”

That level of integrity Arnold has maintained paid off most right when things appeared to be taking a turn for the dire.

Over the last 15 years, clients like Calumet Farm and Boston Red Sox third-baseman Alex Bregman – who could have their pick of trainers – made a deliberate choice to come on board with his program. In the same time span, Ashbrook and BBN Racing have stepped up their participation, collectively resulting in such notable runners as Ashbrook’s 2016 Ashland Stakes (G1) winner Weep No More, fellow Grade 1 winner Concrete Rose, who was campaigned in partnership by Ashbrook and BBN, and Bregman’s stakes winner and Breeders’ Cup starter, Totally Justified.

The lofty purse structure offered by the Kentucky circuit is one factor Arnold points to for helping lure owners like BBN Racing his way as they know they can have their stock there year-round with an established barn and reap the financial benefits. Perhaps the biggest intangible behind Arnold’s ability to maintain his longtime owners like Humphrey while attracting newer clients, however, is the fact that he doesn’t let extreme circumstances impact either his perspective or his faith in his ability.

“Rusty doesn’t get too high or too low, he doesn’t overreact or under react,” said Bo Bromagen, bloodstock consultant for BBN Racing and racing manager for Ashbrook Farm, whose family have been clients of Arnold for decades. “I tend to get swept up in the positives and negatives and if I didn’t have Rusty Arnold, I don’t know how I would maintain a level of sanity. It’s more than just the big wins, it’s the fact you can always count on him. The way he’s been completely honest with us and told us the truth, whether we wanted to hear it or not, is something that over 40 years has really resonated for us.

“I'm probably going to ruffle some feathers but…the super trainers sometimes become a manager of trainers,” Bromagen continued. “And Rusty has stayed at a certain size where he gets eyes on his horses every day. He sees everything that's going on in his barn. And I think a lot of people see what we see in him, which is a talented horseman who is going to do right by the horse more than anything else.”

Like most of his comrades, Arnold is too focused on tending to his equine proteges to indulge in much self-reflection about his feats. What he is intentional about is expressing his gratitude to those who have seen him play the long game his way over the years and signed up to be part of the team.

“I’m humbled by how lucky I’ve been, and I know how lucky I’ve been,” said Arnold, who moved his base back to Kentucky full time in 2006 after more than 20 years in New York. “I’ve met a lot of really, really good people and I’ve got some young people I work for now that I’m crazy about - Alex Bregman, Bo, Brian Klatsky with BBN. Bregman had a lot of choices when he came into this business, buying horses for the money he’s buying them for and making a splash. He can have (five-time Eclipse Award winner) Chad (Brown), he can have Todd (Pletcher). He felt comfortable and gave us the opportunities.

“Usually, it doesn’t happen that way. Usually when you get up in your 60s, everyone wants a younger guy. And again, all these horses started coming in and nothing gets you more enthused than horses who can run. When you play this on a big level, you want to be able to play it on the big level. And fortunately, right now we can.”

When he first went out on his own five decades ago, the goal for the son of the late George R. Arnold Sr., co-owner of Fair Acres Farm, was simply to make a living doing what he always loved. That part of the equation has long taken care of itself, and over the years, the younger Arnold’s success has been measured as much by the folks who seek him out on the rail as any of his top-level triumphs.

“One of the things he’s always told me is he loves the fact that some of the younger generation like Riley Mott and other trainers who are up and coming, they love to talk to Rusty,” Sarah Arnold said. “And he loves that, to let his age and experience trickle down. Even up until 4-5 years ago, Christophe Clement would still call him sometimes and ask him ‘What do you think about this horse?’. People like to pick his brain because they know he is just super honest and has the ethics and morals in this business.”

Among the pieces of wisdom Arnold imparts to the next generation is his appreciation for the nature of the landscape they must operate in. Given that most trainers back in the day were capping their numbers below 50, he feels anyone who can hold their own against the top percentile conditioners like Brown, Pletcher, and Brad Cox is well positioned to follow in his indefatigable footsteps.

“I think it’s so much harder for the younger kids to get going now than when I got going because there were no such thing as super trainers then,” Arnold said. “Those guys would get their 40 horses and they wouldn’t take any more. That’s how I got going. I got recommended to owners. That doesn’t happen anymore. Now, if a guy has 200, 10 more doesn’t bother him. It’s a whole different game. It’s not better or worse, it’s just different.”

There isn’t much Arnold would change about his own career path, but there are certain new experiences he very much would like to explore: namely, getting one of his sport’s “majors”. His best efforts from 18 starts in the Breeders’ Cup are a pair of third place finishes. And while he is hopeful to have contenders for this year’s two-day World Championships at Del Mar Oct. 31-Nov. 1, he would love to make a fairytale type result happen when the Breeders’ Cup is literally in his backyard at Keeneland in 2026.

“I’d like to win one. I don’t know what I can say it would mean to me because I haven’t won one,” Arnold said of the Breeders’ Cup. “We’ve won well over 100 graded stakes, and I think 20 something different horses have won Grade 1s for us. But I haven’t won a Triple Crown race or a Breeders’ Cup. I’d like to win one…then I’d know how it feels.”

Time claims that Arnold is nearing the end of a thoroughly admirable career, that the days of adding grandiose milestones to the pile and churning out the best version of his skillset should be in the rearview. In addition to being one of the respected conditioners in the game, he also among the most grounded.

And the reality is, the current incarnation of Rusty Arnold may still be reaching its peak.

“I’ve got all the confidence in the world in him and frankly he’s got confidence in himself that he knows what he’s doing,” Bromagen said. “What can I say about him? The only thing the guy has ever done for me is everything I needed.”

The latest published research on pre-biotics, digestible fibres, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge

Article by Sorcha O’Connor

We all know that winning races depends on far more than what happens on the day at the track. The health, fitness, and mentality of a racehorse are built long before race day. Increasingly, science tells us that one of the most powerful drivers of performance is hidden inside the horse: the gut. Understanding this hidden half of the body is key to understanding health and disease.

Gut health is central not only to digestion but also to energy supply, recovery, immunity, behavior, and resilience against disease (O’Brien et al., 2022). When the gut is compromised, the impact is felt in poor performance, poor recovery, and increased veterinary bills. On the other hand, when the gut is healthy, horses can perform at their best more consistently.

In this article, we explore the role of gut health in racehorse performance, the risks posed by modern feeding practices, and the latest published research including recent field trials carried out on a novel gut supplement containing pre-biotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins and postbiotics to show how trainers can give their horses a competitive edge (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

The Gut’s Microbiome and Performance

Unlike us, horses can digest fiber. Up to 70% of a racehorse’s energy can come from the fermentation of fiber in the hindgut, where microbes break it down into volatile fatty acids that fuel endurance and sustained performance. A healthy hindgut microbiome also contributes to the synthesis of B-vitamins (vital for energy metabolism and red blood cell production), it supports immune function and plays a role in hormone balance and even a horse’s behavior (Kauter et al., 2019). Although we are only beginning to understand the many functions of the horse’s microbiome, we do know how to fuel it with a diversified, fiber-based diet (Raspa et al., 2024).

Recent research highlights how much gut health influences a horse’s career. The Well Foal Study at the University of Surrey, UK followed Thoroughbred foals from birth to three years of age and found that those with more diverse gut microbiota early in life experienced fewer illnesses and went on to have more successful racing careers (Leng et al., 2024). This connection between gut diversity, health, and future performance directly shows the importance of looking after gut health from the very start of a racehorse’s life

For trainers, the practical implication is clear: a horse’s ability to perform at its peak depends on the stability and balance of its gut microbiome. A compromised gut means reduced energy extraction, more risk of conditions like colic and laminitis, and behavioral changes such as nervousness or lack of focus (Boucher et al., 2024).

Risks of Modern Training Diets

The natural diet of the horse is based on grazing and high-fiber forages. Modern training, however, demands higher energy intake than forage alone can provide. This has led to the widespread use of cereals and high-starch concentrates. While effective at delivering energy quickly, they also pose risks when fed in large amounts.

Studies show that feeding more than 5.5 - 11lbs (2.5–5kg) of cereal per day increases the risk of colic nearly fivefold. Horses fed more than 6lbs (2.7kg) of oats daily were almost six times more likely to colic (Tinker et al., 1997; Hudson et al., 2001). These figures are illustrated below.

2.5 – 5 kg of cereal per day

= 4.8 x colic risk

>5 kg of cereal per day

= 6.3 x colic risk

2.7 kg of oats per day

= 5.9 x colic risk

Similarly, research on equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) shows that feeding more than 0.07oz (2g) of starch per kilogram of bodyweight per meal raises the risk of squamous ulcers by over threefold (Luthersson et al., 2009). This is illustrated in terms of scoops in Figure 3 below (based on average starch levels in a racehorse cube or muesli).

1102lbs (500kg)

Why? Because the horse’s digestive anatomy is poorly adapted to digest large starch meals. Horses produce no amylase in their saliva, and their stomach and small intestine, the sites of starch digestion, are relatively small. When there is an overload of cereal, the starch bypasses these sections and enters the hindgut, where it disrupts microbial fermentation (Julliand & Grimm, 2017). The result is increased acidity, microbial imbalance (dysbiosis), and a cascade of problems ranging from ulcers and colic to poor recovery and unpredictable behavior (Bulmer et al., 2019).

On top of diet, the stresses of a modern racehorse’s life: transport, intense training, and routine veterinary interventions put further pressure on the microbiome. Each of these factors can disrupt gut balance, setting the stage for both health issues and reduced performance (Mach et al., 2020).

Supporting a Healthy Gut

Despite these risks, trainers have good tools to support gut health. The first step is to respect the horse’s natural digestive design:

Forage first: Provide ad lib hay or haylage where possible to keep the digestive system functioning as nature intended. Offering at least a small bit of hay before the morning hard feed has recently been shown to slow gastric emptying meaning a slower, steadier arrival of grain to the gut to allow for better digestion (Jensen et al., 2025). This small amount of hay can create a fibrous mat in the stomach that acts as a buffer against gastric acid. This reduces the risk of acid splash onto the more sensitive squamous region of the stomach lining, thereby helping to protect against ulceration.

Small, frequent meals: Avoid overloading the stomach and small intestine with large concentrate feeds. Horses are trickle feeders, designed to eat little and often.

Controlled starch intake: Keep starch levels per meal controlled as described in Figure 2 to not overwhelm the digestive capacity of the gut.

Consistency: Avoid sudden changes in feed or forage sources, which can disrupt microbial populations. The horse’s digestive system needs a time period of at least 10-14 days to adjust to a change in their diet.

Beyond feeding management, nutritional science has delivered additional aids. These should only be considered once the main dietary and forage management is in order.

Prebiotics — specific fibers that serve as food for beneficial microbes and help support microbial balance.

Probiotics, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (a yeast proven to improve fiber digestion), or Saccharomyces boulardii can stabilize the hindgut in horses on high-starch diets.

Postbiotics — more recently, attention has turned to these beneficial compounds produced during fermentation, which can positively influence gut function and whole-body health.

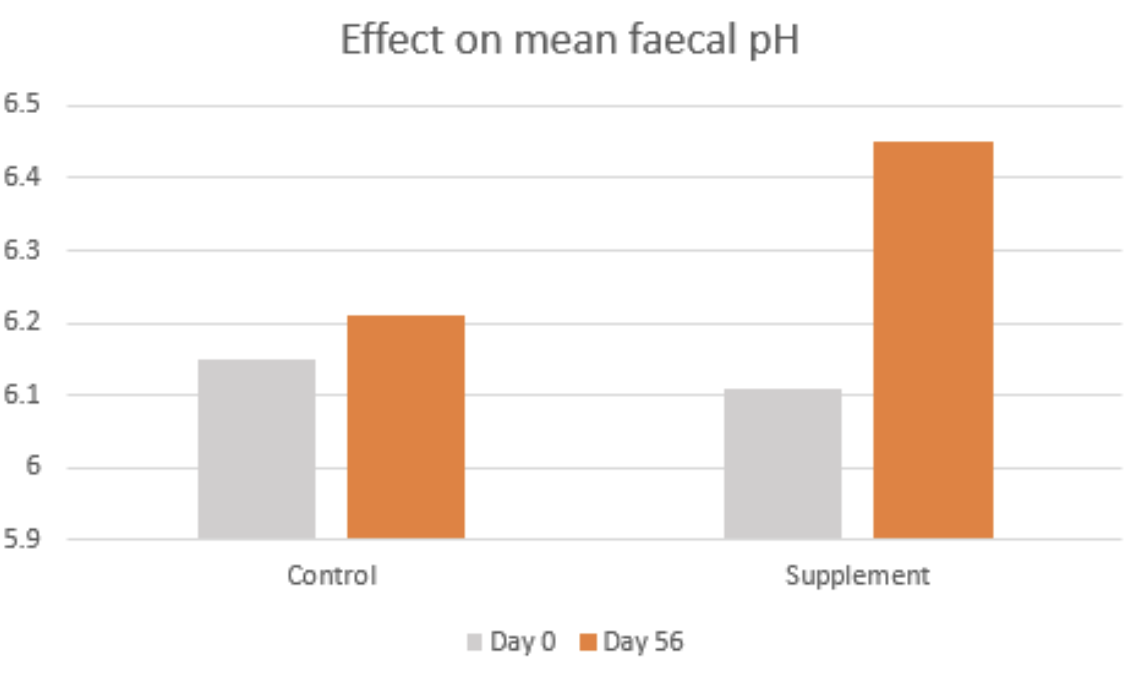

New Research: Postbiotics and Faecal pH

Recent field research involving Thoroughbreds in training has provided new evidence on how targeted nutritional support can shape the gut environment. A novel gut supplement, a nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins, and a fermented yeast postbiotic was trialled on 34 Thoroughbreds in training over an eight-week period. The horses in the trial receiving this supplement showed a significant reduction in faecal pH compared to the control group as shown in Figure 4, indicating a healthier, more stable hindgut environment (O’Connor and Mulligan, 2024).

Figure 4: The effect on faecal pH over time in both groups in the trial

Why does this matter? Faecal pH has been shown as a practical measure for assessing the condition of the rest of the hindgut (Costa et al, 2015). High acidity (low pH) in the hindgut signals excess starch fermentation and an increased risk of acidosis, colic, and poor nutrient absorption. By reducing faecal pH, the supplement supported a more balanced microbial population and more efficient fiber digestion.

For trainers, the benefits of a more stable hindgut:

Consistent energy supply: Better fiber fermentation means a more reliable source of slow-release energy, supporting stamina.

Reduced digestive upset: Lower risk of colic, acidosis, loose droppings, etc.

Improved recovery: A healthier gut environment supports nutrient absorption and immune resilience.

Mental focus: Balanced microbiota have been linked to calmer behavior and reduced stress responses.

This research positions postbiotics as a promising new tool in equine nutrition. While probiotics deliver live organisms and prebiotics provide fuel for the microbiome, postbiotics are the beneficial by-products themselves. They can modulate inflammation, support immunity, and stabilize the gut environment without the storage and survival challenges associated with live probiotics (Valigura et al., 2021).

Beyond Supplements

While supplements are valuable, they are only one small piece of the horse’s diet. Trainers should consider gut health as a whole-yard management issue. Consistency of forage supply is key. Sudden changes in hay or haylage batches can disrupt microbial populations. Hydration must be monitored closely, as dehydration increases the risk of impaction colic. Stress management, from minimising unnecessary transport to keeping consistent training plans and providing adequate turnout or downtime, also play key roles in keeping the gut stable.

Veterinary practices should also be considered. Antibiotics, while sometimes necessary, are known to disrupt the gut microbiome for months after use. Avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use and working with vets to target treatments carefully will help protect long-term gut health and performance. The gut microbiome is made up of thousands of bacteria and other microbes that can be destroyed by an antibiotic course and may take months to recover. Antibiotics should only be used when truly necessary. When they are required, ensure the horse is on a high-quality, fiber-rich diet to help keep the gut supported during this stressful period (Collinet et al., 2021).

Looking Ahead – Gut Health as a Competitive Edge

Equine microbiome research is still in its early stages, but the message is already clear, gut health is tightly connected to race performance. Trainers who prioritise digestive stability through smart feeding, careful management, and targeted nutritional support will not only reduce veterinary costs but also gain a competitive advantage on the track.

The next generation of supplements, including those using postbiotic technology, offers exciting potential to further support racehorses in training. By nurturing a healthier hindgut environment, these tools can help horses get more from their feed, recover faster, and maintain focus under the pressures of racing.

The race truly does start in the gut. By trusting and supporting that hidden engine, trainers can help their horses reach the finish line stronger, healthier, and more consistent than ever.

The gut microbiome of a foal as early as one month old plays a key role in shaping its future health and performance. The foal begins its colonisation through contact with the microbiota of the mare’s vaginal and skin surfaces and its surrounding environments. Its gut microbiome reaches a relatively stable population by approximately 60 days in age. For this reason, sourcing well-reared, high-quality stock is essential to give young horses the best start. A healthy microbiome should be supported throughout the racehorse’s career to give him the best chance of success.

For hundreds of years, the Thoroughbred industry has focused on genetics, breeding from elite bloodlines to produce the fastest, strongest, and most resilient horses. Emerging research, however, suggests another layer of inheritance that may have been overlooked. A foal acquires much of its gut microbiota from its dam, meaning these microbes could prove just as influential as pedigree in determining future health and performance.

References

Boucher, L., Leduc, L., Leclère, M. & Costa, M.C. (2024) ‘Current understanding of equine gut dysbiosis and microbiota manipulation techniques: comparison with current knowledge in other species’, Animals (Basel), 14(5), p.758. doi:10.3390/ani14050758.

Bulmer, L.S., Murray, J.A., Burns, N.M. et al. (2019) ‘High-starch diets alter equine faecal microbiota and increase behavioral reactivity’, Scientific Reports, 9(1), p.18621. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54039-8.

Collinet, A., Grimm, P., Julliand, S. & Julliand, V. (2021) ‘Sequential modulation of the equine fecal microbiota and fibrolytic capacity following two consecutive abrupt dietary changes and bacterial supplementation’, Animals (Basel), 11(5), p.1278. doi:10.3390/ani11051278.

Costa, M.C., Silva, G., Ramos, R.V. et al. (2015) ‘Characterization and comparison of the bacterial microbiota in different gastrointestinal tract compartments in horses’, Veterinary Journal, 205(1), pp.74–80. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2015.03.018.

Hudson, J.M., Cohen, N.D., Gibbs, P.G. & Thompson, J.A. (2001) ‘Feeding practices associated with colic in horses’, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(10), pp.1419–1425. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.219.1419.

Jensen RB, Walslag IH, Marcussen C, Thorringer NW, Junghans P, Nyquist NF. The effect of feeding order of forage and oats on metabolic and digestive responses related to gastric emptying in horses. Journal of Animal Science. 103:skae368. doi: 10.1093/jas/skae368. PMID: 39656737; PMCID: PMC11747703.

Julliand, V. & Grimm, P. (2017) ‘The impact of diet on the hindgut microbiome’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 52, pp.23–28. doi:10.1016/j.jevs.2017.03.002.

Kauter, A., Epping, L., Semmler, T. et al. (2019) ‘The gut microbiome of horses: current research on equine enteral microbiota and future perspectives’, Animal Microbiome, 1(1), p.14. doi:10.1186/s42523-019-0013-3.

Leng, J., Moller-Levet, C., Mansergh, R.I. et al. (2024) ‘Early-life gut bacterial community structure predicts disease risk and athletic performance in horses bred for racing’, Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.17124. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-64657-6.

Luthersson, N., Nielsen, K.H., Harris, P. & Parkin, T.D. (2009) ‘Risk factors associated with equine gastric ulceration syndrome (EGUS) in 201 horses in Denmark’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 41(7), pp.625–630. doi:10.2746/042516409x441929.

Mach, N., Ruet, A., Clark, A. et al. (2020) ‘Priming for welfare: gut microbiota is associated with equitation conditions and behavior in horse athletes’, Scientific Reports, 10(1), p.8311. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65444-9.

O’Brien, M.T., O’Sullivan, O., Claesson, M.J. & Cotter, P.D. (2022) ‘The athlete gut microbiome and its relevance to health and performance: a review’, Sports Medicine, 52(Suppl 1), pp.119–128. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01785-x.

O’Connor, S. & Mulligan, F. (2024) ‘A field study of a novel nutritional combination containing prebiotics, digestible fibers, B-vitamins, and postbiotics’ effects on equine gut acidity’, presented at the 28th Congress of the European Society of Veterinary and Comparative Nutrition, Dublin, 9–10 Sept.

Raspa, F., Vervuert, I., Capucchio, M.T. et al. A high-starch vs. high-fiber diet: effects on the gut environment of the different intestinal compartments of the horse digestive tract. BMC Veterinary Research 18, 187 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03289-2

Tinker, M.K., White, N.A., Lessard, P. et al. (1997) ‘Prospective study of equine colic risk factors’, Equine Veterinary Journal, 29(6), pp.454–458. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03158.x.

Valigura, H.C., Leatherwood, J.L., Martinez, R.E., Norton, S.A. & White-Springer, S.H. (2021) ‘Dietary supplementation of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product attenuates exercise-induced stress markers in young horses’, Journal of Animal Science, 99(8), skab199. doi:10.1093/jas/skab199.

Does the lunar cycle affect horses' performance?

Ken Snyder interviews Dr Barbara Murphy

Moon myths demystified: Lunar phases and a full moon are credited with impacting births, violence, you name it. But there is no hard data to support it, especially effects on humans. Horses? Yes and no.

“According to the available research, moonlight has very little impact on them,” said Dr. Barbara Murphy, Associate Professor of Equine Science at University College-Dublin and the Founder and Chief Scientific Officer for Equilume. The company researched and produced lighting for horses to maximize fertility, performance, and health.

There is one thing: “A retrospective study in Thoroughbreds was done, which showed that peak conception rates occurred during or immediately after a full moon,” said Murphy.

She offers, however, an explanation drawing on common sense plus knowledge of light and its effects. “Horses in the wild tend to be more reproductively active at dawn and dusk. That's around the time they can still see what they're doing, and predators aren't as prevalent at that time. Plus, it’s often when stallion testosterone levels are highest in spring.”

Just as Thoroughbred mares instinctively foal at night as a defense against predators (even though they are ensconced in perfectly safe barns), a full moon in the wild provides enough light to breed when there is less risk of predators. Instinct continues.

There is another factor at work too, according to Murphy. “It's the quality of daylight and the normal absence of light at night.”

White light or regular daylight comprise multiple wavelengths of different colors. Blue wavelengths in light optimally suppress melatonin to regulate sleep-wake cycles and make daylight essentially a time of wakefulness. Melatonin in the body is a hormone that rises in the evening and falls in the morning. It basically tells us it’s time for rest and recovery.

“Blue light is usually absent at night, facilitating sleep, but moonlight has some blue light in it when there is a full moon. The blue light itself makes them [horses] more alert and more active around that time.”

There is much more known, however, about blue light and its documented impact on horse foaling, behavior, and overall health.

Manipulating light, of course, has long been a practice in Thoroughbred horse breeding to create a false spring for mares to foal early. “You want them under an extended duration of light around Thanksgiving or the first of December. That turns on all their reproduction and growth hormones in time for when we want them in the breeding barn,” Murphy said. This light essentially tricks the mare into thinking spring is here and they begin entering heat cycles.

Murphy recommends practices that have produced astonishing results. One is maintaining consistency with the duration of light. Sixteen hours is optimal. Nature takes care of some but not all of that.

Research as part of Murphy’s study for a PhD at the University of Kentucky introduced her to transitioning to another kind of light to ensure horses receive maximum benefits of nighttime rest. “We were trying to take blood samples from horses at night. My professor at the time told me, ‘Whatever you do, Barbara, be very careful and only use dim red light to collect your samples at night.’ Red light won’t disrupt the effects of melatonin, giving horses a full night’s rest and uninterrupted growth for the foal. In short, uninterrupted night darkness in nature should be duplicated or mimicked with stabled horses.

Murphy went back to Ireland and developed a red light for stables similar to that used in developing photographs. “What it means is the stable staff can go in and check the horses. They can put on bandages, they can take a temperature, they can feed them without disrupting their circadian rhythm.”

Light quality is also important. “Daylight is about one thousand times or more intense than what we normally need in a stable. Most good LED lights now have some blue component, which is great, and they should be left on during the day and not turned off in the middle of the day when they're finished exercising or coming in from turn-out. However, to be used effectively, they should ideally be on a timer, have a high blue component and transition gradually to red light or darkness at night”.

A study conducted by an Ocala trainer involved 200 horses, half of whom were put under blue enriched light by day on a timer and a dimmed red light at night. The study was to see the impact on horses before a breeze-up sale in Florida. With horses under blue and red light there was, what the trainer reported as “an incredible difference in the muscling that was put on by the horses, their coats, their condition, their training, and trainability.”

“There was a massive difference in the quality of the scopes,” she added. “Most notable according to the trainer was an absence of pharyngitis.”

A number of other studies investigating the benefits of light, this time for pregnant mares, were carried out in Kildare in Ireland, Brandenburg in Germany and Lexington, Kentucky. Results were reported in the scientific journals Theriogenology, Domestic Animal Endocrinology and The Equine Veterinary Journal. One studied 46 Quarter Horse mares at a research farm in Kentucky. Nineteen mares were fitted with commercially available blue-light masks identical to blinkers used for some horses in races, but with a blinker over just one eye delivering blue light to extend dusk until 11 pm nightly. In total, “daylight” was extended to 16 hours. A second group of 27 horses, matched for age and expected foaling dates to the first group, did not receive additional blue light.

The 19 horses foaled babies with an average weight just over 104 pounds (good for a Quarter Horse baby). Foals from the other 27 horses without blue light had an average weight of just under 96 pounds. In another study, after foaling, researchers discovered in blood samples from one-day old “blue light babies” evidence of a better immune system. “The foals got to their feet fifteen minutes faster if the mare had been exposed to blue light for that last one hundred days before foaling, which was fascinating, because the foals were stronger, more mature,” Murphy said.

The greatest benefit, however, may be in ensuring a normal gestation period of 335 days for horse breeders with mares receiving added blue light. Twenty percent of Thoroughbred mares go longer than 355 days. In a Kildare study, mares without added light had an average gestation length of 350 days. Mares equipped with a blue-light mask in those final three months of pregnancy shortened gestation by almost 14 days to foal close to their due dates. Clearly, careful practices using light can mean important gains for breeding efficiencies.

“The German study found that the mare's follicles post-foaling were bigger. Also, ‘the foal heat ovulation,’ which is the first ovulation that the mare has after she foals, occurred five days sooner, and indicated better post-foaling fertility.

“If a mare conceives in February during the start of the breeding season, and she's due to foal in the subsequent January, she needs to see long days of light again in December. Normally in nature, when a mare foals in April or May, which is the natural breeding season, she would have received the long daylight signal for the final months of her pregnancy.”

In a presentation to the International Society for Equine Reproduction (ISER) Murphy expanded on findings from studies to note that ideal exposure to daytime blue light positively impacts circadian rhythms (biological processes with a 24-hour period). Pre-foaling applications of blue light showed a bevy of benefits in post-foaling fertility, an earlier return to estrus post-foaling, improved colostrum, high foal immunity, and improved first-service conception rates in older mares to name only a few of the benefits.

It could be, perhaps, expected that added blue-light has bearing on stallions and their year-round fertility. A research study resulted in higher testosterone levels through a breeding season, higher sperm produced earlier in the breeding season, and increased semen volume.

Murphy laments the lack of understanding and application in some facets of the industry about light cycles. “I just wish more people would appreciate the power of the light they expose their horses to, and the timing of it.

“The final three months of gestation is the fastest growing time of a horse’s entire life, and the light we give to the pregnant mare controls how the foal develops.” This is also true for horses in training in order to achieve those marginal gains and all of their organs working together in synchrony. “If you have a strong, light-dark cycle, every single aspect of their physiology works better. They're getting more nutrition from their food, they're putting on more muscle, they’re healthier.”

That’s not saying all breeders and farms aren’t aware of a blue light regimen and its benefits. “If you drive around the Bluegrass you'll see them from December on, the little blue lights in the field from the blinkers. The light mask has been fourteen years on the market now, it’s pretty established, but there are some left still to be convinced” Murphy said.

Her company was the first to manipulate a mare’s cycle with a head piece. “I originally developed it in order that the horses could be turned out more and be more active and less stressed and exercised yet still meet our timelines for reproduction.”

Murphy looked, too, at light therapy within stables when horses are brought in after turnout. Her challenge was “provide them with light that's similar to nature and have the same effect--the long daylight, delivered consistently, with optimum wavelengths similar to nature.”

The important thing, Murphy said, is an uninterrupted rest period at night. Just as with humans, sleep interruptions deprive one of sufficient rest to enable us—horses and humans—to be at our best. “White light abruptly turned on at night is a stressor to horses and plays havoc with their internal rhythms. So think before you flick the switch!” she says.

Developing a surgical procedure that could revolutionize the treatment of tie-back surgery

Jackie Bellamy-Zions interviews Professor of Large Animal Surgery, Taralyn McCarrel

Roaring in horses is not just a loud, raspy noise made during exercise; it is an issue in the upper airway that restricts airflow and can limit performance in large breed horses such as Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, and warmbloods. Ontario Veterinary College associate professor of Large Animal Surgery, Taralyn McCarrel, is seeking to develop a surgical procedure that could revolutionize the treatment of tie-back surgery, offering new hope for affected horses.

Roaring, or recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, is a condition where one of the nerves controlling the muscles of the throat becomes dysfunctional. This commonly results in paralysis of the left arytenoid cartilage.

McCarrel provides a quick anatomy lesson, comparing the trachea to a castle, “The airway is made-up of two cartilages called the arytenoids. The arytenoids close like doors to cover the trachea, and then the epiglottis is like the drawbridge that comes up and covers them.” With recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, the control to open the doors is abnormal and overwhelmingly, it is most common that the left side becomes affected.

When the nerve fails, the muscle atrophies and the horse struggles to open the left door of the airway because it lacks the stimulus to contract. Due to the inability for the left arytenoid to be held open, the tissue is left flapping and causes the ‘roaring’ noise. The laryngeal neuropathy puts a limitation on the volume of air available for oxygen exchange which can significantly impact the horse's exercise tolerance, causing them to tire quickly.

McCarrel points out, “This condition is long recognized, with scientific reports dating back to before the formal establishment of veterinary medicine.” Affected horses often exhibit signs of nerve abnormalities throughout their bodies, though these do not have observable consequences aside from the paralysis of important laryngeal muscles. The most noticeable sign is the loud noise produced during exercise if there is a limitation in airflow.

Prevalence and Affected Breeds

Roaring is most common in large breed horses, with draught horses estimated around 33% prevalence. Thoroughbreds have a lower prevalence, ranging from 2% to 8%, while warmbloods are also affected. The condition is often detected early in racehorses due to routine scoping, but in warmbloods, it may go unnoticed until they are older and working harder. Interestingly, some high-level dressage horses can have a completely paralyzed arytenoid cartilage yet make minimal noise, possibly due to head position, speculates McCarrel.

Tie Back Surgery

Prosthetic laryngoplasty, commonly known as tie back surgery, is the current gold standard for treating roaring. This involves making an incision under the horse's neck and suturing the paralyzed cartilage to keep the airway open. Incisional healing typically takes 10-14 days. McCarrel recommends at 30 days post-surgery the horse is scoped to ensure proper healing.

Some surgeons recommend waiting six weeks for the position of the arytenoid cartilage to stabilize following tie back surgery. McCarrel explains, “We try and put the cartilage in a certain open position but there's a strong tendency for it to collapse back to some degree and there's some reset. Most horses will settle at their final position around six weeks.”

Success rates vary widely in literature with non-racehorses generally having a better prognosis due to their lower dependence on maximum sprint-level athletic effort.

Limitations of the Current Tie-Back Procedure and New Ideas

The tie-back procedure, performed to improve airflow in horses with one-sided laryngeal paralysis, has shown varying outcomes that may be influenced by the surgeon's skill. While the complication rate is not extremely high, searching for new ways to minimize complications and optimize results increases the likelihood of horses returning to optimal performance.

One of the most common complications is the arytenoid cartilage not staying as open as intended. McCarrel says, “If we model airflow, then in theory we need to get 88% of maximum to be able to return airflow to be similar to normal.”

Many horses will fall below this threshold, raising questions if they can reach their full competition or racing potential.

The current tie-back procedure involves sutures that can stretch, slip, or cut into the cartilage (causing a loose loop), leading to inconsistent results. “The back of the cartilage we tie the arytenoid cartilage flap to is very thin,” says McCarrel citing another challenge of the current surgical approach.

It was while looking at a CT (computed tomographic image) of a skull, that went as far back as the larynx, that inspiration hit McCarrel. Eyeing up the cricoid, which has thicker cartilage where it contacts the arytenoid cartilage, McCarrel conceived a surgical method that could do away with the knot and sutures and instead use a screw which could result in better stability.

McCarrel also saw the potential for this new surgery to become minimally invasive, only requiring a tiny incision, like what is used in arthroscopy. This would minimize soft tissue trauma that can interfere with the lining of the esophagus, which most often occurs when placing sutures. “If we can place this screw through a little stab incision, we can potentially avoid impinging on and potentially damaging the muscles and nerves in that area,” hypothesizes McCarrel. This could reduce some of the less common complications of tie back surgery like chronic cough or dysphasia (feed entering airways), abnormal swallowing leading to lower airway contamination and reflux of saliva from the esophagus.

Step One

The initial step, already published, demonstrated the ability to CT the equine throat and produce models for measuring the desired parameters. The dimensions of pins and screws were also modeled to ensure they could fit across the targeted area.

Step Two

Phase two was performed by McCarrel’s former resident creating models with a screw rather than suture holding arytenoid cartilage open to the thicker cricoid cartilage. It was then exposed to negative pressures in an airflow chamber for basic proof of concept.

Next Steps and Use of CT

The next step, funded by Equine Guelph, aims to develop a minimally invasive surgery for positioning cartilage through a tiny incision. The current project involves modeling the shape and size of horse airways to create inserts that fit over standard intubation tubes. Via the mouth, these inserts will push the arytenoid cartilage into the desired position, as confirmed on CT prior to surgery.

This requires CT scans of many specimens to create models and determine the number of different inserts needed. The goal is to select the appropriate size insert for each horse during surgery, ensuring precise abduction and opening.

Future steps will include developing an approach and guide to pre-plan screw size and exact placement to ensure accuracy and avoid going into the airway.

Introducing CT 3-D guidance will be a key component to the development of a less invasive procedure. “We can do all the planning before we make the incision,” says McCarrel, “so when it comes time to do the actual surgery, the surgical approach will be very small, and the surgical time will be short.”

“For years now we've had this move in human surgery to increase the amount of imaging guidance in order to have smaller incisions, more precise and minimally invasive surgery,” says McCarrel.

This new approach aims to provide more accurate implant placement with less disruption of muscles and nerves in the larynx, minimize complications and improve outcomes for horses with laryngeal paralysis.

How stud farms determine stallion fees

Article by Jennifer Kelly

The end of the year brings magical seasons like the Breeders’ Cup, winter holidays, and in horse racing, a cascade of retirements as prospective stallions and broodmares exit their careers on the track for the next phase. This is when the sport goes from wagering on races that last minutes to one that lasts years, a bet, a wager that pedigrees, physical attributes, and on-track performances will translate to the breeding shed.

That wager hinges on a mix of knowns and unknowns; a test of how to transition a stallion from athlete to producer, balancing husbandry and business acumen, aided by tax incentives and the lure of opportunity in an ever-evolving marketplace.

*************************************************************

The first Thoroughbred stallion imported to the United States was Bulle Rock, a son of the Darley Arabian out of a Byerley Turk mare, who arrived in Virginia in 1730. A century later, Glencoe, broodmare sire of Kentucky and Asteroid, landed on American soil in 1836. In those early eras, transporting horses was a challenge, so a stallion would stand in one location, servicing mare from the immediate area before being moved to a different farm the following season.

As transportation improved, the process reversed. An owner could keep their stallion at their farm, inviting broodmares to come to him. Sole owners and breeders like Samuel Riddle, who stood Man o’ War, could control the size of their stallions’ books and the quality of the mares admitted to the breeding shed. Income from stud fees went directly to the owner, along with the tax burden.

As stallion prices rose, sharing financial responsibility – i.e., purchase price, veterinary care, board, fertility insurance – became appealing. Syndicates allowed partners to share costs while also ensuring sustained demand for that sire’s services. Shareholders, often broodmare owners themselves, could use their breeding rights or sell them and later decide to retain and race the foal in their colors or sell it to recoup some of their expenses.

One of the earliest syndicates came in 1925, when Arthur B. Hancock of Virginia’s Ellerslie and Kentucky’s Claiborne Farm joined forces with William Woodward, Marshall Field III, and Robert Fairbairn, all of whom had breeding programs of their own, to purchase Sir Gallahad III, a stakes winner in England and France. The group pooled $125,000 to bring the son of Teddy to Claiborne, where he went on to sire Triple Crown winner Gallant Fox along with classic winners like Gallahadion, High Quest, and Hoop Jr.

By the 1950s, syndicates had become more common as breeding in the United States started shifting toward farms standing multiple stallions, often owned by groups of up to 40 shareholders. That number, said Headley Bell of Mill Ridge Farm, was based on the idea that “if a stallion were turned out in a herd of mares, that 40 would be a natural herd for them.”

“Horses stood on syndicate agreements, which were very refreshing in that there generally were 40 or 45 shares in a horse, and breeders were limited to one Northern Hemisphere season,” said Michael Hernon of Hernon Bloodstock, who recruited Tapit for Gainesway Farm. “Now, this would be horses like Nijinsky, Mr. Prospector, Danzig, and the like. Because of the limitation in the supply of the product and the success of those horses in the commercial market, their fees became quite significant. But that resulted from the fact that the supply was so controlled. Over time, somewhat regrettably, we started to move away from syndicate agreements.”

Today, syndicates remain a viable way to launch a new stallion, but outright ownership by major breeders like Coolmore and Spendthrift, has become more common. With previous owners often retaining a share, these arrangements—combined with the commercial market’s expansion—have fueled book sizes that now exceed 200 mares. The Jockey Club’s 2024 Report of Mares Bred listed ten stallions that covered 200+ mares.

In 2025, commercial consideration drives much of the decision making. Farms that bring on new stallions choose between syndication or outright ownership, reflecting an industry increasingly oriented toward breeding to sell.

*************************************************************

At Fasig-Tipton’s The Saratoga Select Yearling Sale in August and then the Keeneland September Yearling Sale, the top sellers came from established stallions Gun Runner and Into Mischief. First-crop sires like Flightline, Life Is Good, and Mandaloun also made headlines, each with yearlings selling for seven figures, led by 2022 Horse of the Year Flightline with 10 total. Flightline also commanded $2.5 million for a share at the 2024 Keeneland Championship Sale at Del Mar, underscoring how lucrative new stallions can be.

With stallion ownership generally falling into the categories of syndication or sole ownership, breeders no longer need to stand and support stallions entirely on their own. Sole ownership allows breeders like Spendthrift to control a stallion’s book and retain the earnings, though it also carries the preponderance of the risk.

“We generally own a stallion outright,” said Ned Toffey, Spendthrift’s general manager. “Very often, the people who've raced a horse are interested in retaining some percentage. That's generally something that remains on the table for us. But the majority of our stallions, we own all or most of.”

For farms like Claiborne, syndication remains the preferred model: “It's a lot of money to bring in these high-dollar stallions, and we can't do it all ourselves,” observed Claiborne president Walker Hancock. “We rely on some great shareholders and syndicate members to help us stand the horse and make the purchase possible. It has evolved over the years. This year, we did our first 50-share syndicate, which we've never done before.”

Ocala Stud favors partnerships over syndication. “We like to partner. We have syndicated horses in the past, but it's been a long time since we've done so,” said David O’Farrell, Ocala Stud’s general manager. “As the Florida Breeding Program has waned over the years, we just feel like there's fewer people that would be willing to participate in a syndicate. It's worked better for us to have partnerships, whether it be four or five different partners that invest in a stallion and then support the horse with mares.”

Regardless of the ownership structure, adding a new stallion relies on two factors: the stars of the racing year and the relationships each farm has nurtured over time. This process can begin months or even years before a potential stallion retires from racing. As Hernon observed, “lately, the demand for a young, appealing horse starts coming into focus earlier, and the horse starts to be pursued from that point of view. Then, conversely, some of them might come down to a career-ending injury that forces the horse to come out of training.”

The challenge remains identifying stallions whose on-track appeal will translate to the breeding shed. As Mill Ridge’s Headley Bell put it, “now you're starting a whole another purpose for this horse and you're redefining what this horse is going to look like. If we believe in him and in his potential as a stallion, we have to give him the best chance. As in, it's not just buying that horse, it's will the market support the horse so people will send mares?”

What are farms looking for in a potential stallion? Hernon identified four factors: “the pedigree, the physical, the performance, and those combined will lead you to the price. And then, of course, the stud fee will ultimately be determined by how much is paid for the horse. The farm has to try and structure the deal whereby they can get enough representation of mares underneath the horse to give them a chance and try and recapture their expenditure before the horse becomes exposed with his first couple of crops on the racetrack.”

Farms must consider not only who is available in a given year, but also who is already in the shedrow.

“We probably wouldn't go after two sires of the same caliber, like the same distance, same surface, same sire line, so we do try and differentiate between that,” noted Hancock.

Sequel Stallions’ Becky Thomas looks for “a sire line that I respect. Our last stallion that we brought to market was Honest Mischief, of course. He’s the leading sire of his group. I try to model our program up of what I feel like is brilliance. At some point in time, I want to see that you displayed something that was different than a lot of the other stallions.”

For programs like O’Farrell’s, a stallion is just the beginning of their investment. They maintain a broodmare band of about 50, raise the resulting foals through their two-year-old year, sell them essentially as ready-made racehorses.

“It really comes down to, do we feel like we can get a runner? And do we feel like that we can market these horses at the two-year-old sales in three years? It’s a huge investment for us, carrying them to the two-year-old sales,” O’Farrell shared. “You've got a significant amount of investment in that broodmare, and so you better believe in the stallion because you're carrying the output for so long.”

Once a farm identifies a candidate, the challenge is turning successful racehorse into a successful stallion and doing it quickly enough to ensure long-term commercial viability.

*************************************************************

Farms take different approaches to ensure a prospect transitions into a pro. For Spendthrift, “our goal is to add at least one, if not several, stallions every year. That's basically because we understand that the simple odds are that most stallions are not going to be successful,” Toffey said. “Our mindset is that we have to continually try to bring in new horses to continue to build the roster and to replace the ones that are not making the grade.”

Other farms, especially regional ones like Ocala Stud, do not add a new name every year. “We’re not always in the market for a new stallion because we can't justify bringing one in and standing them for enough money,” O’Farrell observed. “It's hard to justify it from a stud fee perspective. When we look at stallions, rather than doing the math of seeing what it would take to get out in three years, our philosophy is more, would we be willing to breed 15 good mares to the stallion in the first two years?”

Bringing on a new stallion carries significant costs, including fertility insurance, board, veterinary care, and marketing. Such a significant investment requires the stud fee be calculated carefully. Price the stallion too high and breeders may shy away; too low, and it can signal a lack of confidence. “The objective of every farm is to get mares to the stallion. When you set the stud fees, you’re basically taking a wild guess,” O’Farrell explained. “Obviously, it comes down to what you paid for the horse. Not that you need to get that money back in three years, but you need to price him to where you feel like he can be competitive.”

The stud fee also affects long-term viability. “It's become expensive now to board a horse and pay the insurance and the associated vet work. We're in a different world now. The in-vogue stallions are highly in demand and they're going to cost a lot of money,” Hernon observed. “It's a catch-22 because the farms who buy them, based on purchase price and the demand and the competition for said horses, will determine a high dollar value on the horse to secure them. Consequently, the farm has to breed a significant number in order to make the figures work, and recapture most of their investment.”

Setting that fee is not formulaic; it is nuanced. “It's not just one or two Grade 1s equals X stud fee,” Toffey observed. “What did they do at two? What did they do at three? How did they win their races? Who did they beat? Who is the sire? What is the female family? How did they win their races? Were they the favorite every time or were they 20 to 1 and came out of nowhere? There's a lot of variables that go into building it.”

For farms like Mill Ridge and their stallion Oscar Performance, a horse that the Amermans bred and raised at the farm, Bell emphasized collaboration. “We've got to do this together. Our objective isn't to make him worth the most valuable today. We have to make him valuable down the road. In order to do that, we're going to have to be reasonable in how we price this horse because those 20 shareholders end up being your partners. You're asking them not to support this horse in the first year; you're really trying to provide incentives to them to support them in the first through fourth year, at least.”

Spendthrift and similar stud farms take a proactive approach when it comes to promoting new stallions because perception drives demand. “Since a huge percentage of the breeding market today are commercial breeders, when they look at a horse, they got to feel like, ‘This is a horse that I can use and have some success with,’” Toffey shared. “Either it's going to work well with my mare, it looks the part, or ‘Hey, look, people are really going want to buy these horses, buy this horse's offspring, so they're going to be commercially viable.’”

Commercial viability often comes before racing ability. Buyers, whether mare owners, pinhookers, or racing managers, rely on tangible factors like pedigree and physical attributes when deciding whether to invest in a stallion’s progeny. Bringing on a new stallion means not only covering the costs of a mature horse but also attracting customers for his services—that is marketing.

For a horse like Flightline, an undefeated Horse of the Year, marketing is easier. For others, farms use in-house marketing teams or public relations firms.

“Every horse has strengths and weaknesses, and we, go back to the old expression, accentuate the positive. We want to look at what messages will resonate with breeders,” Toffey said. Spendthrift brands each stallion individually, developing logos and merchandise, as do other farms like Claiborne and Lane’s End.

Other breeders take a lighter approach. “Our philosophy is, if you stand horses, if you stand a quality stallion at the right price, that is going to be the best advertisement,” O’Farrell observed.

Marketing, along with the stud fee, ultimately affects book size. In 2024, 64 first-year sires covered a minimum of five mares, with four—Gunite, Elite Power, Pappacap, and Taiba—servicing 200 or more. That’s just 6% of the total. Other stallions with large books, like Justify, Gun Runner, and Vekoma, had multiple breeding seasons under their belts. Book size reflects more than stud fee; it also depends on the stallion himself.

“Horses, like people, are different. They're made different. They have different characters, different DNA. They're not all equal on the racetrack, and they're certainly not all equal in the breeding shed,” Hernon observed. “Horses have different levels of libido and fertility, and some have a limitation in the number of mares they can comfortably breed in a season. Newer stallions, they don't know what they're doing, and they have to be taught.”

While breeding a mare may seem an instinctual undertaking for a horse, in reality it is a skill no different than teaching a horse to accept a rider and then to race. Farms may limit a new stallion’s book to allow them a chance to learn. Overbreeding a horse can be as problematic as over racing, because it can affect their confidence and create challenges for a stallion manager.

“Often, what we do with our first-year horses is we start them a little bit lower to make sure that they can handle [the job.] Not every horse can handle 180, or 160, or 150. So the first year, we're going to try to keep them down below 200,” Toffey observed. “There's some things we can do to estimate those things beforehand, but you really never know until you get into breeding season. It's a case-by-case basis.”

Some farms maintain each stallion’s book at a set level but have adjusted over the past 25 years to remain competitive. “We used to cap it at 140, but we felt like our stallions were at a bit of a competitive disadvantage with other people breeding theirs to 250 plus,” Claiborne’s Hancock shared. “In order to keep up, we have raised our book size to about 175, 180. Now, I don't anticipate going over that. I think our stallions can comfortably handle breeding that many mares.”

A farm’s book policy can influence where a stallion stands or where breeders send their mares. “Breeders will just have to choose what farm policy of numbers of mares on the book that they're comfortable with, and that can predetermine their choice as to stallion and where they might breed,” Hernon observed.

Technology has also reshaped book management. Broodmare managers have tools like drugs to help a mare ovulate at a more ideal time and ultrasounds able to show finer details, enabling veterinarians to gauge the size of an ovarian follicle and predict more precisely when a mare might be ready to breed. Whereas in previous decades, a mare might need to be covered twice to ensure that they catch, such advances can increase the chance a stallion impregnates them on one.

“We're now able to do book sizes with the assumption that mares don't need to be doubled. Whereas it used to be not uncommon to have to double a mare on a heat cycle. Now it still happens, but it's rare that we have to double a mare. That alone opens up so many more spots. We're able to be way more efficient with the use of a stallion,” Toffey said.

Even after identifying a stallion prospect, negotiating a deal, setting a stud fee, and filling the book, doing it outside Kentucky, which remains the heart of American breeding, can be challenging, even in established regions like California, Florida, and New York.

*************************************************************

Even generations of experience in the sport does not insulate a farm from the realities of the modern bloodstock marketplace. David O’Farrell, the third generation at Ocala Stud, acknowledges the challenges: “Look, there's no question that Kentucky is the center of commerce in the Thoroughbred world and will be for a very long time. It's getting tougher in the so-called regional markets. But I do think there's a very good opportunity in places like Florida, where people that are investing and doing business have the opportunity to win these [breeder] awards, even though they might not be as lucrative in Kentucky.”

Becky Thomas of New York’s Sequel Stallions takes a similar approach: “Our stallions in New York cannot compete with the stud fees that Journalism and Sovereignty are going to demand. So we do not compete at that level, and most people in Kentucky cannot compete at that level. We try to be competitive with our like class level.”

For Rocky Savio of Savio-Cannon Thoroughbreds, moving their stallion Smooth Like Strait, from Kentucky to California might go against conventional wisdom, but the move was strategic. The stallion’s foals can be raced at his owners’ home tracks, as well as take advantage of the California-bred incentive program.

“We feel familiar with this scene. Michael [Cannon] and I have been going to Del Mar for the past 30 years of our lives, and Smooth Like Strait did most of his racing and winning on the West Coast. He's a California horse,” Savio shared.

In September, the California Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association announced a bonus increase for Cal-bred winners of maiden special weight races at 4 ½ furlongs and longer in both restricted and open company, adding $2,500 to both bonus for races at Santa Anita and Del Mar. Starting with the 2026 crop, the CTBA also instituted a $1,000 bonus for each registered state-bred foal up to 25 foals per CTBA member breeder. Additionally, the organization provides a transportation reimbursement up to $3,000 for mares 12 years old or younger purchased for $20,000 or more out of state and then bred to a California stallion.

“Obviously, another reason why we're going to California is for the Cal-bred bonuses.

That's why we made the move,” Savio shared. “I know everyone's moving the other way, and we're going against the grain of what's actually happening. But I think there's something left there that is beneficial to an owner.”

Regional programs in California, New York, and Florida offer awards for breeders and stallion owners, plus stakes races restricted to state-breds. The New York Racing Association is even moving toward full purse parity for state-bred races by 2027, while Florida adds incentives for state-breds at select out-of-state tracks in 2026.

Even with these incentives, programs like Sequel and Ocala Stud must compete with Kentucky, especially given the commercial market growth. As such, stud fees have to be competitive in states where the margins are slimmer and even a thousand dollars can make or break a stallion’s season.

“You have to understand your market. If they're not selling, then you've got a price that is too high. If they're selling too much, then you've got a price that’s too low. So you have to feel the market out a little bit. And it's incredible how much a $1,000 price point makes a difference in a market like Florida,” said O’Farrell.

Thomas sees that “New York is somewhat of an island, but really, we are part of an international business. I don't want to bring stallions to market that I don't feel like have a domestic as well as international feel if they hit. I mean, there's no stallion that's popular past the freshman year unless they hit.” Because it remains a top-tier racing hub, owners still flock to the Empire State to compete in its lucrative and famed tests. With the coming purse parity and the new Belmont Park, breeding, selling, and racing in New York is full of financial opportunity beyond purses.