Smaller nations - the challenges facing trainers in Denmark, Poland and Spain

In the last issue, we featured a table of champion trainers and jockeys across Europe, compiled by Slovakia’s Dr Marian Surda. In this one, we have selected three of those champion trainers—those of Denmark, Poland and Spain—and tried to find out a little more about them and what it is like to be at the top of the training tree in their respective countries. While there is plenty of positivity and success to report, the challenges of sustaining viable businesses in the ‘smaller’ racing nations of our region, even for those at the top of their profession, are evident. It is a salutary finding that two of the three are looking to move on from the countries in which they have made their names.

Of our chosen trio, Guillermo Arizkorreta was the most highly ranked (by earnings), finishing 7th of 19 with earnings of €886,250 achieved through 61 winners at a strike rate of 19.3%. Niels Petersen not only finished 9th with his €311,537 in Denmark, but he also finished 8th as champion in Norway, with a further €443,856. And Cornelia ‘Conny’ Fraisl, one of only two females on the list, came in at No 14, earning €131,791 from her 50 wins in Poland.There are many similarities between the three. All happen to be of a similar ‘vintage’, being in their late 40’s or 50’s.

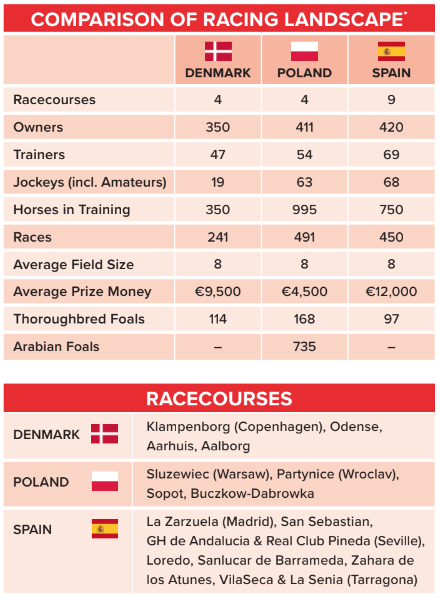

Denmark has the fewest horses in training but has ready access to those trained in neighbouring Sweden and Norway. The number of trainers among whom these horses are divided are roughly comparable, as are the numbers of their owners. There is some disparity in prize money, with Poland some way adrift of the other two countries. None has a thriving thoroughbred breeding industry, producing limited numbers of foals and therefore relying on foreign-bred imports and foreign-trained runners to achieve the near-identical average field sizes of eight runners per race.

Denmark has one thoroughbred-only track (Copenhagen’s Klampenborg) and three dual gallop and trotting courses. In Poland, Sluzewiec—the main track at the country’s capital—is joined by three others, including Wroclav (where most Polish jump races are run) and the seaside track at Sopot. Spain has four traditional tracks, headed by La Zarzuela in Madrid and, in addition, has three beach racecourses and two ‘pop-up’ tracks.

NIELS PETERSEN

Niels Petersen can claim a unique achievement among current European trainers, in that he is Champion Trainer not only in Denmark, but also in Norway. While Petersen was born and raised in Denmark, he has lived in Norway for the past 25 years, from which base he has stewarded a stellar training career. He has earned the title of multiple champion trainer in all three Scandinavian countries, with combined annual prize money often exceeding €1M and peaking at around €1.7M. Over the years, he has garnered 788 winners in Scandinavia, at a strike rate of around 16%.

Petersen is a prolific winner of Scandinavia’s richest race, the Group III Stockholm Cup International. Square de Luynes ran up a hat-trick of wins.from 2019 to 2021, and Bank of Burden was a four-time victor in a long career. “My most consistent horse was probably Bank of Burden, but my best horse has been Square du Luynes. The Racing Post called him ‘Frankel of the Fjords’”!

Asked for his view of the best trainers in Europe, he says, “People like to say it’s a numbers game, and of course it is, and I know they have the firepower; but the way Aiden O’Brien and John Gosden place their horses, and the level they maintain year after year is just amazing and fantastic to watch. And I greatly admire Karl Burke. To have bounced back and actually raised his game, as he has, after all he’s been through…”.

As for the riders: “Frankie Dettori is special, of course, and I think William Buick, whom I know very well, is a fantastic jockey”. And turning to racetracks: “Ascot and Longchamp are absolutely fantastic tracks, and here in Scandinavia, Bro Park is very level and fair”.

Petersen’s move to Norway was by way of circumstance, not planning. Having completed his education and military service, he worked in Baden-Baden, (alongside friends who included jockey William Buick’s father) for a couple of years, before returning to his homeland, where he suffered a serious riding accident. Forced to seek work opportunities which did not involve riding, his knowledge of the German language came in handy, and he was asked to accompany Scandinavian-trained horses when they raced in Germany. There he met a Norwegian trainer who invited Petersen to join him in Norway to help train his jump horses.

Last year and the year before, Petersen operated a satellite yard in Denmark, (just as once he did also in Sweden). Around 15 of his 55 horses were based at Klampenborg racecourse, and in both those years he claimed the Danish championship. However, despite that success, adverse exchange rate movements have led him to abandon the Danish base. “The Danish customers actually preferred to put the horse up with me in Norway. I haven’t lost any clients, and all their horses I have with me in Norway now.”

Petersen is quick to praise the integrated race planning across the Scandinavian nations, making it practicable for trainers to map out campaigns for their horses. So, for example “if you have an outstanding miler, you can target all the big mile races, more or less.”

Securing owners in any one country is challenging enough—how does Petersen approach the task of finding owners in three countries? He is clear that the trainer’s job is not simply to train the horses—the social component is also vitally important. For example, the path to Dubai for its Carnival is a well-trod one—its purpose for Petersen being as much to enrich social relations with and amongst his owners as the pursuit of prize money.

“I’ve got to make people enjoy the hobby I can provide them with. You do sacrifice a lot of time in doing that. But when you’ve sat on the beach and shared a bottle of wine in your swimming trunks, you become better friends!”

The travel and the socialising place a premium on having excellent staff back at base and has been fortunate to have had a long-standing assistant in the business in the shape of his elder sister. “I make sure that my staff are well paid, and I’m strict in observing proper working hours. It has become more difficult to find good staff, but word of mouth has ensured we have an excellent team, including a number from South America”.

Petersen has noticed a reduction in horses in training in all three countries. “I’m a bit pessimistic as to the future of racing here, especially in Norway, because our government is not supporting the industry at all. It classifies it as a hobby and, unlike in Sweden and Denmark and elsewhere, you cannot own horses as part of a business. It means owners have to pay 25% VAT on top of imports, which they can’t get back.”

Dubai’s allure is, of course, all the greater in the contrast it provides to the long, harsh Scandinavian winters. Petersen rues the fact that, from November to April, the Scandinavian climate renders virtually impossible the effective preparation of horses and, despite his huge success there, he has an eye out for opportunities abroad. “I would like to say I’m not looking for something outside, but I am. I live and breathe Scandinavian racing, but do I see myself here in five years’ time? I don’t think so. I don't see myself being here in five years’ time. I'm only 51 years old—not even at my peak—and I want the opportunity to challenge myself where I know I should be: on the bigger international scene”.

Until then, Scandinavia has given Petersen many special memories. What was his best day? “In Denmark, on Derby Day 2021, I had runners in seven races, and I won all seven of them!” If Square de Luynes was ‘Frankel of the Fjords’, then, after that ‘magnificent seven’, one could almost be forgiven for dubbing Niels Petersen ‘Frankie of the Fjords’.

CONNY FRAISL

Fraisl’s rise to the top in Poland has been meteoric. Her first year with a public trainer’s licence was as recent as 2020, when, with 44 winners, she finished second in the trainers’ table. Two years later, she was crowned Champion, with 50 winners. Fraisl is alone among our trio in concentrating almost exclusively on Arabian, rather than thoroughbred racing.

“I was born in beautiful Salzburg, Austria”, she explains. “My grandparents had a little farm and, when I was three, my dad bought me my first pony. It was a ‘typical’ stubborn Shetland Pony; and once I’d landed on the ground several times, I asked my dad to ‘sell this pony and buy me a guinea pig’!”

But the lure of riding returned a decade later. “Close to the place I lived, there was a training stable for trotters where I spent every free afternoon, all my holidays from the age of 13. Racing always was fascinating for me. Flat racing In particular but, due to the fact that there was no flat racing stable in my area, I stayed the next seven years with trotters. But I always had an eye on flat racing and, in 1996, when I moved from Salzburg to Vienna, I was finally close to a racetrack where regular flat races were held. So, I made contact with one of the trainers, started to ride regularly in daily training there, gained my amateur licence and bought my first own racehorse.”

“I had the possibility of riding work in Florida for several weeks, and I could learn a lot about starting young horses there. During my earlier days in the trotting stable, I learned a lot about intensity of training, interval training, feeding and the general needs of racehorses”.

As an amateur, Fraisl notched up around 25 winners in Austria and Hungary, where she rode for two seasons for different trainers. Turning professional in 2006, she has amassed 208 winners in the saddle to date, riding in countries as far afield as Malaysia.

For her training career, Fraisl moved to Poland, her then-partner’s homeland, where she set up a private breeding and training facility in Strzegom, not far from Wroclav. “At the beginning, we had in training only homebred horses, thoroughbreds. Step by step, one by one, came some Arabians from Austria, Germany, Sweden.... and when they started to win more and more races. Owners from different countries recognised the job we were doing and sent us more and more Arabian horses to be trained in Poland. Today, she has some 80 boxes and 40 places for youngstock. She is an advocate of turnout for horses’ well-being. “Twenty-five huge grass paddocks can be used all year round and all of our horses—including the racehorses—enjoy several hours outside every day. This is the most positive aspect for mental health. We also have an indoor arena and a horse walker as well as many possibilities to ride out into fields and forest to create the most individual training for our horses as possible”.

These days, Fraisl continues to ride out for nearly all the lots. “This is the best possibility for me to see how the horses in training work, how they behave—simply to ‘feel’ them”.

However, in Fraisl, we find another champion trainer wanting to move on from the country of their triumphs. “Actually we are dramatically reducing the number of our horses, and we are not accepting new horses and owners. The reason is that I am leaving Poland soon and will stop my job as a trainer here”.

Fraisl cites a multitude of reasons for this bombshell decision which, she says, she has taken after lengthy consideration. “The number of foreign Arabian horses—as we mainly have them in training—is also getting smaller and smaller. This means that we are forced to enter three, four or five horses from our stable together in one race, or that race will be cancelled. This makes no sense for us and our owners any more”.

Stagnant prize money and rising costs (of staff, transport, feed, bedding and veterinary and blacksmith services) are another factor. In addition, “there is a big lack of work riders. Most trainers work with a handful of enthusiastic amateurs, mainly young girls, who come to ride some lots before school or study or during holidays”. Fraisl also rues the talent drain of the best jockeys in Poland to other countries. She claims that drug and alcohol misuse is a real issue amongst riders and also that black-economy practices are common in the capital, with staff being employed without legal papers or insurance. “We have all our staff employed on a legal basis, and this is why we are the most expensive stable in Poland. We are already tired [of] explaining to the potential new owners why the prices of others are much lower—that's why we finally decided to close our training stable”.

These points were put to the Polish Jockey Club (PJC) racing secretary and the EMHF executive council member, Jakub Kasprzak. Kasprzak points to the fact that Poland is not alone in facing economic challenges, with high inflation being experienced generally across the continent. “It is true that prize money has not risen for some years, but it still compares favourably with that in, for example, Czechia or Slovakia. We are currently trying to support breeders and owners of Polish-bred horses. We have put in place a five-year programme to help this group of people. Ms Fraisl’s yard has 95% foreign-bred horses, so she is unable to participate in that programme. We have been paying transport only to horses to travel to Sopot (just four days’ racing per year) because there are no horses in training within 100km of that racecourse.”

“It is true that Polish riders, of all levels of ability, will often seek happiness abroad. But a shortage of racing staff is something that is being experienced throughout Europe. We are now seeing many staff coming from countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. However, I don’t recognise her point about insurance and illegal workers. Every rider MUST have official insurance to be licenced. We at the PJC are very exacting about it. And as to drug and alcohol problems, every rider has a medical control before the start of a race. If the medical officer sees anything incorrect, he will report it to the stewards. Two years ago, one rider was suspended for one year for being drunk on race day”.

Where will Fraisl relocate to? “Time will tell. I hope to find a nice place where I can continue my work with Arabian horses.”

Fraisl has not been averse to sending horses abroad to compete ‘whenever it makes sense’. Indeed it has been the forays abroad that have provided her with her most treasured racing memories. “As key moments, I would mention the experience [of taking] part and finishing fifth in the UAE President Cup - UK Derby in Doncaster this year with Bahwan and especially our first Group winner last year in Jägersro, Sweden. For me as a trainer, this was the first Group race abroad. For our young stable jockey it was the first big chance to ride a Group race and show his talent abroad so we said ‘let's go and try’. We had no idea how the colt would do on a dirt track and without the whip (in accordance with the rules in Sweden). In the event, it was the first Group win for me as trainer, for our jockey, and for the breeder....it was an unforgettable day for all of us”.

GUILLERMO ARIZKORRETA

One man has enjoyed a stranglehold on the Trainers’ Championship in Spain for over a decade. Guillermo Arizkorreta first topped the table in 2012 and has remained there ever since.

By contrast with the other featured trainers, Arizkorreta trains at shared facilities, with some 25 others, at the La Zarzuela racetrack, very close to Madrid. It helps contain costs and has in turn contributed to the fact that Arizkorreta’s owners have enjoyed an enviable return on their annual costs, of over 75%. “It is very easy for the trainer. The owner pays €200/month to the racecourse, and it includes stabling, water supply, electricity, use of gallops, etc. Overall, having a horse in the yard costs around €1500/month, all included. It means that it is not that difficult to cover the cost of having a racehorse. On average, my horses have earned €13.500/year since I started”.

His operation supports some 70 horses in training and a workforce of around 25. “We have very nice staff, from many countries: Germany, Chile, Czech Republic, Italy, Nicaragua, Bolivia. As everywhere, there is a shortage, and it is not easy to find good riders. We have around 17 full-timers who work approximately 40 hours a week, a couple of part-timers, and some jockeys who are self-employed. The staff that work full-time work one weekend in two and the same for the evening stables. The basic wage for a full-time rider is around €19.000/year”.

“I started in a pony club in Oiartzun (close to San Sebastian) which was owned by a racehorse owner. There I met (four-time French Champion jockey) Ioritz Mendizabal, who had a keen interest in racing; and we started to ride racehorses in our local track in San Sebastian. From then on, I started following Spanish racing, and afterwards I started to follow racing and breeding around the globe, which became my passion”.

Arizkorreta singles out three key events in his rise to the top. “First, being able to compete in the FEGENTRI series as an amateur rider opened my eyes, and I was lucky to ride in many countries. Secondly, after finishing my degree, I spent nearly six years working as [an] assistant in the UK to Mr Cumani and in France to Mr Laffon Parias; and I learned a lot with them.

“Lastly, Madrid racecourse was closed between 1996 and 2005, and I was lucky to be ready to start my career at the same time as the racecourse reopened. I was known as an amateur rider in Spain, and all the background from my experience abroad helped me a lot to get some clients in very exciting times”.

“We have won 878 races from 4,450 runners. In Spain, we have won all the major races and probably our biggest achievement abroad was to win a Gp3 and a Gp2 on the same weekend in Baden Baden in 2021”.

Loyal support from some of the country’s biggest owners has been a hallmark of Arizkorreta’s career. “I have a good bunch of owners. The majority of them have been with the yard for a long time. At the moment, we have around 20 different ownership entities—33% sole ownership and the rest partnerships. The majority of them used to come racing when they were children and have a good knowledge of the sport”.

Arizkorreta has not been shy of campaigning his horses abroad and has reaped healthy rewards, capped by that dual Group-winning day in Germany. “Since I started, I have always tried to race as much as possible abroad. We have had 112 winners abroad—mainly in France, but we have also won in Dubai, Germany, Morocco and Switzerland; and we have had runners in Saudi, Sweden, UK, and Italy”.

“I feel we have done pretty well abroad, and in the right races, our horses are usually competitive”.

The trainer has much that is positive to say about racing in his country. “Madrid Racecourse is our ‘shield’, classified, as it is, as a monument. It is a fabulous racecourse, with lovely stands, a good turf track and a good crowd of people every meeting. It is very close to the city centre and is a track definitely worth visiting. Prize money could be better for the big races but in general is good, especially for the low-grade races. Being close to France helps us find suitable races for some horses”.

As to what could be improved, Arizkorreta would welcome improved planning of the race programme and greater unity between trainers, jockeys, and owners to “push in the same direction and to improve the basics of our industry”. And financial structures also mean that there is not the opportunity to access horse walkers or equine swimming pools.

All in all for Arizkorreta, the future, if not stellar, looks stable. “I think in five years’ time we will be in a similar position. Things could be much better but, realistically, with politicians not giving us the tools to develop the betting and our industry; it is hard to imagine an improvement in the short term. We need them to make a long-term plan for racing and breeding and to consider it as an industry that can create wealth and employment in many areas. Since 2005, the ruling government has helped us with prize money, which covers nearly all the races run in the year; and I see no reason why it should change, especially in Madrid.

“We have some lovely racecourses, which are always attended by a good crowd. In our biggest racecourse in Madrid, the weather is usually lovely, and it is becoming very popular in the city. There is scope to improve in many areas, and I can see it being one of the nicest racecourses in Europe. San Sebastian needs more support from the local government, but it is a historic racecourse in an amazing city. And I hope Mijas racecourse will reopen at some point”!

It was heartening to find that at least one of our ‘smaller nations’ champion trainers shows no signs of wishing to leave the country.

Amy Murphy – Thinking Outside the Box

Equuis Photography / Jason Bax

Article by Katherine Ford

“I’m a bit choked up; this horse means the absolute world to me…” Amy Murphy was close to tears at Auteuil in March as she welcomed stable stalwart Kalashnikov back into the Winners’ Enclosure with Jack Quinlan aboard. It was a first success in almost four years for the ten-year-old, although the intervening months had seen the popular gelding performing creditably at Graded level in campaigns interrupted by injury. Connections pocketed €26,680 for the winners’ share of the €58,000 conditions hurdle; but the satisfaction far surpassed the prize money.

“An awful lot of blood, sweat and tears have gone into getting him back, but don’t get me wrong: if at any point we thought that he wasn’t still at the top of his game, we’d have stopped because he doesn’t owe us anything.” Runner-up in the Supreme Novices’ Hurdle at the 2018 Festival and a Grade 1 winner at Aintree the following season, Kalashnikov put Amy Murphy—with her refreshing enthusiasm and undeniable horsemanship—on the map from the start of their respective careers.

“He is very much a people’s horse. He was campaigned from the early days at the highest level, and he had some real good battles as a young horse; and I think that those types of horses that don’t go down without a fight, people lock onto them and follow them.”

From veterans to juveniles

Equuis Photography / Jason Bax

While the achievement of keeping a ten-year-old on form and identifying a winnable race at Auteuil for his French debut is considerable, the success was all the more notable as it came just three days after Myconian had earned connections €15,000 for victory in the Prix du Début at Saint-Cloud—the first juvenile contest of the Parisian season. It is rare to find a trainer with success at both ends of the age spectrum, in two different disciplines, but when you add in the fact that Amy Murphy had crossed the Channel to complete this unusual double, it demonstrates a laudable versatility.

“We try and work with everything we get sent. We’re in a fortunate position where we’ve got the best of both worlds with lots of lovely young horses; but Kalashnikov, Mercian Prince and some of the old brigade have been with us since we started. I started training six years ago, and they were two of the first horses in my yard so they’ve been a big part of my career and still are.”

Twelve-year-old Mercian Prince has racked up a total of 13 wins for Amy since arriving in her fledgling yard from France in 2016, with three of these coming in the past 12 months and including one in Clairefontaine last summer. As with Kalashnikov, patience has reaped rewards with this veteran.

“Mercian Prince is very tricky to train at home—he has a mind of his own, and everything’s got to be on his terms. We do lots of different things with him. He will go three or four times during the year to the beach at Holkham, which is about an hour down the road. It keeps him mentally active. I’m a big believer in freshening them up. I like to string a couple of races together and then give them a week or ten days out in the field at the farm—things like that. It’s fine if you’ve got two-year-olds and it’s a short-term game; but with older horses that you know are going to stick around, you’ve got to keep them fresh.”

From pony-mad to the youngest trainer in Newmarket

Ambitious and determined, Amy Murphy spent her childhood on her father’s Wychnor Park Stud in Staffordshire. “My dad bred National Hunt horses as a hobby. I always had ponies and hunted and showjumped until I was about 16; then I started riding out for local trainers and got bitten by the racing bug. I spent all of my weekends and holidays riding out for as many people as would let me in. My dad wouldn’t let me leave school without any qualifications, so I went to Hartpury College and did a diploma in equine science. The day after that finished, I was in a racing yard.”

After a stint with Nicky Henderson, Amy’s now-characteristic adventurous spirit led her to Australia and an educational season with Gai Waterhouse. “Australia was where I learnt more about spelling horses. Their horses will only have three or four runs together and their seasons are split up so they can campaign them with breaks in between the different carnivals. Gai is obviously brilliant with her two-year-olds and does lots of stalls work with them, and that was another important thing I learnt with her.”

On returning to the UK, Amy joined Tom Dascombe as pupil assistant at Michael Owen’s Manor House in Cheshire, which opened the doors to France for the first time, overseeing his satellite base in Deauville during a summer. Her racing education was completed with four years at Luca Cumani’s stable in Newmarket before setting out on her own in 2016, at age 24—the youngest trainer in Newmarket.

“One of the biggest things I learnt from Luca was making sure a horse is ready before you run. As you become a more mature trainer, you relax more into it; you learn that patience pays off. If you think something needs a bit more time or something’s not quite right, then nine times out of ten, you need to be patient.”

Patience is a virtue

Amy with Pride Of America & Lemos with Miss Cantik.

Amy Murphy may have learnt patience with her horses, but she is impatient with a system that she has had to seek and find alternative campaigns for her horses due to low prize money in the UK. “As William Haggas said to me the other day, I’ve got off my rear end and done something about the situation.” She continues, “It’s very hard to make it pay in England, sadly, so it’s either sit here and struggle or do something outside the box.”

Amy’s first Stakes success came in France in just her second season training, thanks to £14,000 breeze-up purchase Happy Odyssey, winner of a juvenile Listed contest at Maisons-Laffitte and who quickly added more profit by selling for €300,000 at Arqana’s Arc Sale just days later. “From very early on, we’ve targeted France. To start with, it was just the black-type horses; but once I got to know the programme a bit better, we started to bring a few of the others across too.”

The ”we” referred to includes Amy’s husband, former Brazilian champion apprentice Lemos de Souza, whom she met when working for Luca Cumani and who now plays a vital role at Amy’s Southgate Stables. “He’s a very good rider and a very good judge of a horse, and is a great asset to have with the two-year-olds. It’s nice having someone to work with and bounce ideas off. He has travelled all over the world—Dubai, Japan, Hong Kong—for Luca Cumani with all of his good horses.”

French flair

Tenrai & Jade Joyce.

Last year, the pair widened their horizons further with the decision to take out a provisional licence in France, renting a yard from trainer Myriam Bollack-Badel in Lamorlaye. “We were going into the complete unknown. My travelling head girl Jade Joyce was based out there along with another girl; and we basically sent out twelve horses on the first day and between them, they had a fantastic three months. The two-year-olds were where our forte lay and what we tried to take advantage of, whereas we had never had horses run in handicaps in France. So, we had to get the older horses handicapped, and the system is completely different.

Amy with racing secretary, Cat Elliott.

There were plenty of administrative errors early on, as my secretary Cat Elliot was doing everything from in Newmarket; so there were plenty of teething problems and plenty of pens being thrown across the office… For example, I didn’t know you couldn’t run a two-year-old twice in five days, so I tried to declare one twice in five days … little things like that. It was all a learning process, like going back to square one again.”

The operation was declared a resounding success, with eight wins and 15 placed runners during the three-month period, amassing a hefty share of the €276,927 earned by the stable during 2022 in France. Among the success stories, juvenile filly Manhattan Jungle was snapped up by Eclipse Thoroughbred Partners after two wins at Chantilly and Lyon Parilly and was later to take Murphy and team to Royal Ascot, the Prix Morny and the Breeders’ Cup. Meanwhile, another juvenile filly, Havana Angel, earned black type in the Gp.3 Prix du Bois, entered Arqana’s Summer Sale as a wild-card and changed hands for €320,000.

The sole regret is that France Galop only allows trainers one chance with the provisional licence. “We tried to apply again this year but sadly got turned down. Moving over full time is not out of the question in the future.”

Vive la Difference

During her stint at Lamorlaye, Amy had the chance to observe some of the French professionals; and although she stresses, “I wasn’t up at Chantilly so didn’t get to see the likes of André Fabre…,” she also notes, “The gallops men would be very surprised by how quick our two-year-olds would be going regularly. The French seem to work at a slower pace, whereas we are more short and sharp; and we use the turf as much as we can. We would work our two-year-olds in a last piece of work with older horses to make sure that they know their job.”

Impressed by the jumps schooling facilities in Lamorlaye, Amy was also complimentary about other aspects of the training centre. “I like the way that you can get the stalls men that work in the afternoon to come and put your two-year-olds through in the morning. That’s all very beneficial to both the horse and to the handlers because they know each other. Another big thing which I love over in France is that when the turf is too quick, they water it so that you can still train on it in the mornings, even at the height of the summer.”

Even without the provisional licence, Amy Murphy’s name is still a familiar sight on French racecards. At the time of writing in late May, her stable has earned €117,446 in prize money and owners’ premiums in 2023, from 18 runners of which four have won and eight placed.

To reduce travel costs, organisation is key. “I had a filly that ran well in a €50,000 maiden at Chantilly recently, and she travelled over with a filly that ran and won at Saint-Cloud three days later. They were based at Chantilly racecourse for the week and moved across to Saint-Cloud on the morning of the race and then came home together on Friday night. It takes a bit more logistics but financially it makes sense to send two together.” As for the owners, they have made no complaints about seeing their horses race further afield. “Plenty of my owners have been over to France; they love it. I haven’t had one person say they don’t want to go to France yet, anyway!”

Defending an industry

Closer to home, a subject dear to Amy’s heart is horse welfare and the image of racing. On her social media accounts, she promotes the cause and has invited the public to visit her stable to see for themselves the care that racehorses are given. “I’ve had a couple of contacts but nowhere near as many as I’d like. As an industry, we have to show that this image that so many people have of racing is just not true. The only way we can do that is by getting people behind the scenes and letting them see just how well these animals are loved and cared for by all of the girls and guys in the yards. Events like the Newmarket Open Day, when we get thousands of people in to visit the years, are the kind of thing that we need to keep pushing. I want to be in this sport for a long time, so I want to do anything I can to help promote it.”

With advocates like Amy and a generation of motivated young trainers, the sport of horse racing can count on some highly professional, hard-working and modern ambassadors, in the UK, France and beyond.

Assessment of historical worldwide fracture & fatality rates and their implications for thoroughbred racing’s social licence

Article by Ian Wright MRCVS

Racing’s social licence is a major source of debate and is under increasing threat. The principal public concern is that racing exposes horses to significant risk of injury including catastrophic (life-ending) injuries of which fractures are the commonest cause. The most recent studies in the UK indicate that fractures account for approximately 75% of racecourse fatalities. Recent events highlight the need for urgent stakeholder discussion, which necessarily will be uncomfortable, in order to create cogent justification for the sport and reliant breeding industry.

A necessary prelude to discussion and debate is an objective assessment of risk. All and any steps to reduce risks and mitigate their impact are important and must be embraced by the horseracing industry (and quite possibly all other horse sports). To begin this, a here and now assessment is important: put simply, does the price paid (risk) justify the benefit (human pleasure, culture, financial gain, employment, tax revenue, etc). Objective data provides perspective for all interested parties and the voting public via their elected representatives, who ultimately provide social licence, with other welfare issues—both human and animal—on which society must pass judgement.

The data in Tables 1 to 12 report a country by country survey of fracture and fatality rates reported in scientific journals and documented as injuries/fatalities per starters. It may be argued that little of the data is contemporary; the studies range from the years 1980 to 2013. However, the tabulated data provided below is the most up to date that can be sourced from independently published, scrutinised scientific papers with clear—albeit sometimes differing—metric definitions and assessable risk rates.

In assimilating and understanding the information, and in order to make comparisons, some explanatory points are important. The first, and probably the most important, is identification of the metric. Although at first glance, descriptor differences may appear nuanced, what is being recorded massively influences the data.

These include fatality, catastrophic injury, fracture, orthopaedic injury, catastrophic distal limb fracture, fatal musculoskeletal injury, serious musculoskeletal injury, and catastrophic fracture. The influence of the metric in Japanese racing represents the most extreme example of this: ‘fracture’ in the reporting papers included everything from major injuries to fragments (chips) identified after racing in fetlocks and knees, i.e. injuries from which recovery to racing soundness is now an expectation. At the opposite pole, studies in other countries document ‘catastrophic’, i.e. life-ending fractures which have a substantially lower incidence. The spectrum of metric definitions will all produce different injury numbers and must be taken into account when analysing and using the data.

Studies also differ in the methods of data collection that will skew numbers in an undetermined manner. Some only record information available at the racecourse, others by identifying horses that fail to race again within varying time periods, horses requiring hospitalisation following racing, etc. The diagnostic criteria for inclusion of horses also vary between reports: some document officially reported incidents only, some are based only on clinical observations of racecourse veterinary surgeons, while others require radiographic corroboration of injuries.

From a UK perspective, the data is quite robust in concluding that risks differ significantly between race types. The majority of fractures that occur in flat racing, and between obstacles in jump racing, are the result of stress or fatigue failure of bone. They are not associated with traumatic events, occur during high speed exercise, are site specific and have repeatable configurations. In large part these result from a horse’s unique athleticism: in the domesticated species, the thoroughbred racehorse represents the pinnacle of flight-based evolution. Fractures that result from falls in jump racing are monotonic—unpredictable, single-event injuries in which large forces are applied to bone(s) in an abnormal direction.

This categorisation is complicated slightly as fatigue failure at one site, which may be bone or supportive soft tissue, can result in abnormal loads and therefore monotonic fracture at another. The increased fracture rate in jump racing is explained in part by cumulative risk. However, it is complicated by euthanasia of horses with injuries with greater post injury commercial value and/or breeding potential that might be treated. Catastrophic injuries and fatality rates in NH flat races are most logically explained by a combination of the economic skew seen in jump racing and compromise of musculoskeletal adaptation.

Racing surface influences both injury frequency and type. Studies in the UK have consistently documented an increased fatality rate and incidence of lower limb injury on synthetic (all weather) surfaces compared to turf. Although risk differences are clear, confounding issues, such as horse quality and trainer demographic, mean that the surface per se may not be the explanation. In the United States, studies reporting data from the same geographic location have produced mixed results. In New York, these documented greater risks on dirt than turf surfaces; while a California study found no difference, and a study in Florida found a higher risk on turf. A more recent study gathering data from the whole of the U.S. reported an increased risk on dirt surfaces. Variations in the nature of injury between surfaces may go some way toward explaining fatality differences.

Much has been done to reduce recognisable risk factors particularly in jump racing; but in the UK, it is likely (for obvious data supported reasons) that it will come under the greatest scrutiny. The incidence of fractures and fatalities in flat racing are low, and the number of currently identified risk factors are high. Over 300 potential influences have been investigated, and over 50 individual factors demonstrated statistically are associated with increased risk of catastrophic injury.

The majority of fractures occurring in flat racing (and non-fall related fractures in jump racing) are now also treatable, enabling horses to return to racing and/or to have other comfortable post-racing lives.

The common public presumption that fractures in horses are inevitably life-ending injuries is a misconception that could readily be remedied. An indeterminate number of horses are euthanised on the basis of economic viability and/or ability to care for horses retired from racing. On this point, persistence with a paternalistic approach is a dangerous tactic in an educated society. Statements that euthanasia is ‘the kindest’ or ‘best’ thing to do, that it is an ‘unavoidable’ consequence of fracture or that only ‘horsemen understand or know what is best’ can be seen as patronising and will not stand public scrutiny.

At some point, data to distinguish between horses euthanised as a result of genuinely irreparable injuries and those with fractures amenable to repair will become available. Before this point is reached, the consequences require discussion and debate within the racing industry.

Decisions on acceptable policies will have to be made and responsibility taken. In its simplest form, this is a binary decision. Either economic euthanasia of horses, as with agricultural animals, is considered and justified as an acceptable principle by the industry or a mechanism for financing treatment and lifetime care of injured horses who are unlikely to return to economic productivity will have to be identified. The general public understands career-ending injuries in human athletes: These appear, albeit with ongoing development of sophisticated treatments at reducing frequency, in mainstream news.

Death as a direct result of any sporting activity is a difficult concept in any situation and draws headlines. Removal of the treatable but economically non-viable group of injuries from data sets would reduce, albeit by a currently indeterminate number, the frequency of race course fatalities. However, saving horses' lives whenever possible will not solve the problem: it will simply open an ethical debate viz is it acceptable to save horses that will be lame? In order to preserve life, permanent lameness is considered acceptable in people and is not generally considered inhumane in pets. Two questions arise immediately: (i) How lame can a horse be in retirement for this to be considered humane? (ii) Who decides? There is unquestionably a spectrum of opinion, all of which is subjective and most of it personal. It will not be an easy debate and is likely to be complicated further by consideration of sentience, which now is enshrined in UK law (Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022); but it requires honest ownership of principles and an agreed policy.

For the avoidance of doubt, while the focus of this article and welfare groups’ concerns are on racecourse injuries, those sustained in training follow a parallel pathway. These currently escape attention simply by being, for the most part, out of sight and/or publicity seeking glare.

Within racing, there is unquestionably a collective desire to minimise injury rates. Progress has been made predominantly by identification of extrinsic (i.e. not related to the individual horse) risk factors followed by logical amendments. In jump racing (monotonic fractures), obstacle modification, re-siting and changing ground topography are obvious examples of risk-reducing measures that have been employed.

In flat racing progress has involved identification risk factors such as race type and scheduling, surface, numbers of runners, track conditions etc which have guided changes. However, despite substantial research and investment, progress in identification of intrinsic (ie relating to the individual horse) risk factors is slow. While scientifically frustrating, a major reason for this is the low incidence of severe fractures: this dictates that the number of horses (race starters) that need to be studied in order to assess the impact of any intervention is (possibly impractically) high. Nonetheless, scientific justification is necessary to exclude a horse from racing and to withstand subsequent scrutiny.

Review of potential screening techniques to identify horses at increased risk of sustaining a fracture while racing is not within the scope of this article, but to date none are yet able, either individually or in combination, to provide a practical solution and/or sufficiently reliable information to make a short-term impact. It is also important to accept that the risk of horses sustaining fractures in racing can never be eliminated. Mitigation of impact is therefore critical.

When fractures occur, it is imperative that horses are evaluated to be given the best possible on course care. This may, albeit uncommonly be euthanasia. Much more commonly, horses can be triaged on the course and appropriate support applied before they are moved to the racecourse clinical facility for considered evaluation and discussion. The provision of fracture support equipment to all British racecourses in 2022 marked a substantial step forward in optimising injured horse care.

Neither racing enthusiasts nor fervent objectors are likely to change their opinions. The preservation of social licence will be determined by the open-minded majority who lie between: it is the proverbial ‘man on the street’ who must be convinced. The task of all who appreciate horse racing's contributions to society and wish to see it continue is to remain focussed on horse welfare, if necessary to adjust historical dogmas, absorb necessary costs and to encourage open, considered, honest (factually correct) risks versus benefits discussion.

Warsaw finally hosts EMHF assembly and stewards' conference

Article by Paull Khan

It’s just possible that the main benefit of the EMHF to its racing administrator members is the social dividend. Many of us have been involved for a dozen years or more, and the bonds that have developed within our network allow easy and unhesitating communication whenever some international issue or other should crop up in our racing lives. This column’s regular reader will know that the EMHF seeks to enrich our members’ education by moving our biannual meetings around the region and combining them with attending the races in the host country. In this issue, following a successful gathering in Poland, we try to convey a little of the flavour of an EMHF General Assembly reunion.

Back in 2019, when we gathered in Oslo and memorably celebrated Norway’s exuberant May 17th National Day celebrations, it was announced that, the following year, we would reconvene in Warsaw. That was not to happen, due to COVID, and the next two years were Zoom affairs. When the pandemic’s grasp began to ease, the Polish plan was back on the table— only for the conflict in neighbouring Ukraine to put an end to those hopes. Ireland manfully stepped in to host us at The Curragh in 2022; and so, when our party—of 48, from 19 countries—finally descended on the Polish capital on the middle weekend of May, there was a palpable feeling of relief.

By common consent, it was worth the wait.

Following the pattern introduced in Ireland, the event was split across two days. The first afternoon was devoted to all the things that one associates with a General Assembly: financial, membership and administrative matters, together with updates, from each member country present, on the state of racing in their respective nations, as well as from various relevant committees and sister organisations. The hosts also gave a colourful account of the rollercoaster that is the history of racing in their homeland.

We were pleased to welcome, once again, representatives of the European Federation of Thoroughbred Breeders’ Associations (EFTBA) and the European and African Stud Book Committee (EASBC). Because the EMHF has long taken the view that we in the equine sector should avoid operating in isolation, and instead benefit from cross-fertilisation of knowledge and ideas, these organisations, together with the European Trotting Union (UET) and European Equestrian Federation (EEF), are standing invitees to our General Assemblies.

After an excellent dinner that evening at the elegant Rozana restaurant in the Konstancin area of the city, our second morning was wider in its scope, and the floor was given to a number of experts who presented on a range of matters of current interest or concern.

Police involvement in French racing

Those who followed the high-profile rape allegations against Pierre Charles Boudot or the arrests of the Rossi trainer brothers might have been struck and intrigued by the closeness of the involvement of the French police. Henri Pouret, EMHF executive council member for France, explained how there is a branch of the national French police force—the Service Centrale Courses et Jeux—dedicated to racing and gaming matters. No licenced or registered participant in French racing—be they owner, trainer, jockey or breeder—is allowed to participate unless their registration is authorised by the ‘racing police’. Then, once registered, if such an individual becomes subject to judicial proceedings, the racing police may require France Galop, or its trotting equivalent, Le Trot, to withdraw or suspend their licence. This is not just a theoretical power—on no fewer than 25 occasions did they do just this in the course of last year.

It is only for the past three years that doping a racehorse has been a criminal act in France. It seems likely that the racing police will play an ever more central part in the regulation of French racing.

FEGENTRI and the International Pony Racing Championship

With EMHF’s formation last year of the European Pony Racing Association (EPRA) and the launch in 2023 of FEGENTRI’s Junior Championship, never has there been a more opportune time to explore and develop the relationship between the amateur and professional communities in European racing. It was therefore a pleasure to receive FEGENTRI’s secretary-general, Charlotte Rinckenbach, to explain the work and relevance of her organisation.

FEGENTRI, the international federation of gentlemen and lady riders, has a history that stretches back to 1955. It is therefore longer established, not only longer than the EMHF, but also longer than both the IFHA and the Asian Racing Federation. It organises amateur races around the world, across four main championships, and prides itself on providing a distinct and effective route by which to involve people in our sport from diverse walks of life.

FEGENTRI Junior is the first international pony racing championship of its kind. It has started in a modest way, with four countries each fielding two young riders, aged between 14 and 16 years. (The competition, which has the full support of the EPRA, is open to those of 12 years and over; but no-one younger than 14 was chosen this year). Their level of experience varies greatly—some have only ridden in a dozen races; others have 150 rides and over 50 winners under their belts. These eight trail-blazing youngsters have the wonderful opportunity of riding competitively in Florence, Bro Park, Chantilly, Livorno and Kincsem Park. And who’s to say that, from amongst them, we will not see a champion of the future?

Gene doping and its implications for EMHF members

‘Gene doping is not a rumour anymore’, was the stark opening warning from Dr Kanichi Kusano of the Japan Racing Association, one of the world’s experts in this sphere. He explained that the abuse of genetic therapies is a major threat to racing’s integrity. In the worst-case scenario, the heritable genome of a thoroughbred would be changed through genetic modification at the breeding stage—of the eggs, sperm or embryo. The good news is that, in this race, the ‘good guys’ are up with the pace, and already there are out of competition (OOC) tests for gene doping that are being deployed.

Smaller countries, without extensive resources to direct towards research or detection, were advised to prepare by ensuring their rules adequately outlawed the practice and to publicise and start a programme of deterrent sample collection, followed by OOC testing as soon as the leading racing nations offer a suitable commercial service.

The World Pool

Tallulah Wilson, UK Tote Group’s head of international racing, spoke of the burgeoning impact of the World Pool and how EMHF countries could get involved through the World Tote Association (WoTA). World Pool, the Hong Kong-based system for commingling bets placed on key international races, is only four years old; but it has already demonstrated that races selected for inclusion enjoy a startling increase in pool betting turnover.

Higher liquidity attracts the high-rollers and creates a virtuous circle from which the participating racecourses benefit, potentially boosting prize money. However, legislative restrictions in Hong Kong mean that the races included do not number in the thousands, or even hundreds. Just 25 race days, predominantly in Britain and Ireland, will form the 2023 roster. While this number is growing, the prospects of most EMHF member countries having a race included in the near term are only distant (although fresh ground has been broken this year through the inclusion—as a single race from a different country within a World Pool Day—of the German Derby).

However, Wilson’s message was that ‘everyone is welcome’ within WoTA. Member countries’ Tote operators were encouraged to apply to join, opening up the possibility of their punters being able to bet into the commingled World Pools and earning that pool operator and its racing industry a slice of the take-out.

Racing to school and National Racehorse Week

For over 20 years, a British programme has been introducing racing to schoolchildren, presenting aspects of their school curriculum through the lens of a visit to a racecourse, training yard or stud. John Blake, CEO of Racing to School, spoke of 16,000 children who attended such a course last year, instilling in many of them a positive sentiment towards the sport, which may hopefully translate in time into ownership or professional involvement.

The third National Racehorse Week in Britain will take place in September, when racing yards and stud farms will open their doors to welcome members of the public. Over 10,000 took up the offer last year, of whom one-fifth were new to racing.

At a time when our sport’s public image is under increasing pressure, these positive interactions with the public are initiatives which many member countries could look to replicate.

Racing at Sluzewiec

With the business affairs completed, it was off to the races. The approach to Sluzewiec Racecourse is through a proud avenue of mature trees, and the whole expansive site was lush and green. The stands were indeed grand, completed, with unfortunate timing, in 1939—just before the onset of war. An attractive feature of the main grandstand is a sloping, stepless zigzag by which one ascends and descends from floor to floor. It makes for a photogenic feature—ideal for the fashion catwalks that are sometimes staged there.

The EMHF Cup was run over a mile for unraced three-year-olds worth €3,200. It attracted a field of eight runners. The winner, Sopot was one of only two Polish-breds, taking on horses foaled in Great Britain, France, Czech Republic and Ukraine.

The nine-race card was worth a total of €24,000. A mixed programme comprised thoroughbred, trotting and Arab races, from 1300m (6 1/2f) up to 2400m (1 1/2m). No race attracted fewer than seven runners and the largest field was 11. Interestingly, in an apprentice race, for riders who had ridden fewer than 25 winners, the whip was not allowed to be carried, let alone used.

Horserace betting is not ingrained in Polish society, and there was little evidence of avid form study, or raucous cheering. However, the crowd’s demographic was a revelation: it was hard to spot a grey hair, with patrons almost exclusively families or young adults. It made for a beguilingly relaxed atmosphere.

Our horizons have been broadened by the experience of witnessing racing in such diverse settings across the EuroMed region as Waregem, (Belgium), La Zarzuela (Madrid, Spain), Kincsem Park (Budapest, Hungary), Casablanca (Morocco), Leopardstown and The Curragh (Ireland), St. Moritz (Switzerland), Bro Park (Sweden), Hamburg (Germany), Marcopoulo (Athens, Greece), Bratislava (Slovakia), Les Landes (Jersey, Channel Islands), Pardubice (Czech Republic), Ovrevoll (Oslo, Norway), Veliefendi, Istanbul and Izmir (Turkey), Cheltenham (Great Britain) and now Warsaw.

Seeing the sport flourish in such varied surroundings brings home the need to do all we can to preserve racing in every country in which it currently takes place. Singapore’s decision to draw the curtain down on horseracing was such dispiriting news. A broad and thriving base to our pyramid enriches us all.

First EuroMed Stewards’ Conference

Few things in international racing excite as much comment and criticism as comparing decisions taken by stewards around the world. There is a constant cry for consistency in the rules that apply to the running of a race, in the way stewards interpret both the races and the rules, and in the levels of penalty handed down. Harmonisation of such matters is a real challenge, not least because there is nobody in horse racing that sets world rules; each national racing authority sets its own. But that is not to say that substantial efforts are not made constantly to improve things in this area. It is the very raison d’etre of the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities’ (IFHA’s), International Harmonisation of Racing Rules Committee (IHRRC), and is also the subject of much of the discussion at the International Stewards’ Conferences (ISC) that the IFHA has staged, roughly every two years, around the world.

But these meetings must limit the numbers of delegates in attendance, and it is in practice that only the major racing nations benefit from being party to the discussions. For this reason, it was decided to stage a Stewards’ Conference for the EuroMed region and to welcome all EMHF member countries—large and small. This suggestion, proposed by Germany, was picked up with enthusiasm by Britain. Thus, it came to be that the day after the General Assembly, the BHA’s Brant Dunshea chaired the inaugural EuroMed Stewards’ Conference, which attracted a pleasing turnout of 30 delegates from 12 countries.

Joining from Australia via Zoom was Kim Kelly, who has for many years chaired both the IHRRC and ISC; he set the scene and placed this gathering into its global context. There followed a range of presentations, including the following.

Competency-based training programme

The job of the steward is high-profile, highly-charged and perpetually subject to criticism from both the media and the public. The BHA’s Cathy O’Meara described how Britain has recently introduced a competency-based training programme to ensure that its stewarding workforce, along with all raceday teams, is (and remains) up to the job. Through a combination of interactive on-line learning, shadowing, mentoring and more, stewards learn, and are then assessed on, race reading, the rules, enquiry training and report writing. And, once initial competencies are met, the learning journey is not over. All stewards will be required to complete continued professional development, where half of the content relates directly to their roles and half to general industry-related issues such as equine and human welfare. A next step will be to develop a module for the use of those in the industry, such as trainers and the general public. The BHA also has plans to offer to receive stewards from smaller racing nations to assist in their development.

Illegal betting

The EMHF’s equivalent in the Asian and Oceanian region, the Asian Racing Federation (ARF) and, in particular, Hong Kong, is on the front line in a battle against illegal betting. The ARF has established a Council on Anti-Illegal Betting and Related Financial Crime; and its chair, Martin Purbrick, joined us by video conference.

The stark facts are that illegal betting is growing much more quickly than legal betting and already represents the majority of online betting. Aside from the fact that illegal betting makes no contribution to racing, nor to society at large, through taxation, it is also intrinsically linked to race-fixing and organised crime. While Asia may be the historic hotbed of this activity, Purbrick cautioned that Asian illegal betting has already expanded into Europe.

Online betting is no respecter of national boundaries, and if we are to be successful in this war, it will require a joined-up, cross-border and multi-agency approach, involving governments, racing authorities, gambling authorities and the police. But we cannot leave it to these organisations alone—it is incumbent upon all of us to be aware of the risks of race manipulation and to whistle-blow if ever we encounter it.

Virtual stewards’ room

This column (April 2020) described a novel system of remote stewarding, witnessed by the author in Johannesburg. It looked forward to a day when Stewards are situated at a central location, away from the track, from which they communicate with the principals on-track and view video footage. This might be widely adopted, promising more consistent application of the rules and the opportunity for smaller countries to outsource their stewarding function to larger countries.

The Conference heard how this brave new world might just have moved a step closer. The BHA reported on a system first trialled in 2020 and prompted by the COVID outbreak. The pandemic created a situation in which there was a real risk of stewards being unavailable due to a requirement to isolate. In response, assistant stewards began working remotely, through video conferencing from their homes, but initially without access to the full range of views available to the stewards on-course. The BHA then set about developing a hub, away from the racecourse, which offered the full range of race replays. While it was considered there was still the need to have a senior person on the course, the hub provided resilience against absence, allowed stewards to officiate at afternoon and evening meetings on the same day, etc.

The trial has now been rolled out in Britain, such that all assistant stewards have the option to work from home, improving their work/life balance. Around 25 percent of fixtures are covered by the technology, and it is planned to expand this further in the future.

Anti-doping activities

It has long been appreciated that trainers, when racing in different jurisdictions, should, as far as is practicable, be assured of facing similar treatment regarding medication control. To that end, the European Horseracing Scientific Liaison Committee (EHSLC) was set up over 30 years ago and continues to lead on this area of racing administration in our region. The Conference heard how the EHSLC (which is comprised of the chief veterinary officer/anti-doping manager from the member countries, representatives of the national laboratories, which carry out regulatory work for those countries, specialist pharmacologists and senior administrators from the racing authorities) has generated a significant amount of data relating to common use medications and has published detection times for many substances. The science underlying these data is rigorous and the subject of considerable review and has often been accepted by the wider global racing community, forming the basis of international screening limits.

Feedback on the inaugural EuroMed Stewards’ Conference has been universally positive, and there is much enthusiasm to make this a regular event, perhaps again being staged alongside our General Assemblies.

Train, Race, Recover and Repeat – How targeted nutrition can support the recovery process to optimise performance

Article by Dr Andy Richardson BVSc CertAVP(ESM) MRCVS

Introduction

Horses evolved as herd-living herbivores with a digestive tract designed to cope with a near continuous dietary input of forage in the form of a wide range of plant species. A large hindgut acts as a fermentation vessel where gut microbiota (predominantly a mix of bacteria, protozoa and fungi) exist in harmony with the horse in order to digest the fibre rich plant material.

Fibre is important to the horse for several reasons. The digestion of fibre releases energy and other key nutrients to the horse. Fibre also acts to provide bulk in the digestive tract, thus helping maintain the passage of faecal material through the system. Fibre also acts like a sponge to absorb water in the gut for release when required.

As horses became domesticated and used for work or sporting purposes, more energy-dense feeds in the form of cereal grains were introduced to their diet, as simple forage did not provide for all the caloric requirements. Cereal grains are rich in starch, which is an energy-dense form of nutrition. However, too much starch can cause problems to a digestive tract that remains designed for a pasture-based diet. The issues that can be caused by the trend away from a solely pasture-based diet can be digestive, behavioural or clinical.

Nonetheless, the combination of forage and cereal-based concentrates remains the mainstay approach for the majority of horses in training today, in order to maximise performance. A great deal of research and expertise are utilised by the major feed companies to ensure that modern racehorse concentrate feeds provide adequate provision of the major nutrients required and minimise unwanted effects of starch in the diet.

This article aims to discuss some scenarios where targeted or supplemented nutrition can act to help overcome some of the nutritional challenges faced by the modern horse in training, as they “Train, Race, Recover and Repeat.”

Equine Gastric Ulceration Syndrome (EGUS)

EGUS occurrence in racehorses is well documented, with prevalence shown to be over 80% in horses in training (Vatistas 1999). With a volume of approximately 2–4 gallons (7.53–15 litres), the stomach in horses is relatively small compared to their overall size due to its functional role in accommodating trickle feeding that occurs during their natural grazing behaviour.

As a horse chews, it produces saliva, which is a natural buffer for stomach acid. When the horse goes for a period of time without chewing, the production of saliva ceases, and stomach acid is not as effectively neutralised. The lower half of the stomach is better protected from acid due to its more resistant glandular surface. The upper, or squamous, region does not have such good protection, however, and this can be a problem during exercise when acid will physically splash upwards, potentially leading to gastric ulceration.

In practice, this can presentrepresent a challenge for horses in training. Typically, they will be fed a concentrate-based feed in the early morning that stimulates a large influx of acid in order to help digest the starch. This may be followed by a period without ad-lib access to hay, thus reducing the amount of saliva subsequently produced to act as a buffer. When the horse is subsequently worked, there is a risk of acid damaging the upper squamous region of the stomach. There is some evidence to suggest that the provision of hay in advance of exercise may act like a sponge for the acid, as well as helping form a fibrous matt to minimise upward splash.

Gastric ulceration can go undetected in horses in training and may not lead to any obvious clinical signs. In other horses, it can lead to colic, poor appetite, dull coat and behavioural changes. In both scenarios, it is likely that the ulceration will have an impact on their performance, with decreased stride length, reduced stamina and inability to relax at speed all being possible consequences (Nieto 2009). Gastric ulceration can therefore have a significant impact on the ability of a horse to perform optimally day in day out in a training environment. This is exacerbated when ulceration leads to a reduction in appetite, with the obvious downside of a reduction in calorie intake leading to condition loss and further drop in performance.

This is an area where targeted nutrition has been clinically proven to play an important role. Ingredients such as pectin, lecithin, magnesium hydroxide, live yeast, calcium carbonate, zinc and liquorice have all been studied as having beneficial effects on gastric ulceration (Berger 2002, Loftin 2012, Sykes 2013). It is likely that a combination of the active ingredients will be most efficacious, with benefits noted when the supplement is added to the feed ration to help neutralise acid and form a gel-like protective coating on the stomach surface.

The daily administration of a targeted gastric supplement can be an important part of daily nutrition of the horse in training, alongside the use of pharmaceuticals such as omeprazole or esomeprazole when required.

Sweat loss

Horses have one of the highest rates of sweat loss of any animal, with sweat being comprised of both water and electrolyte ions such as sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium and calcium. Therefore, it is not surprising that horses in training are at risk of unwanted issues should sweat loss not be replaced.

It is also worth noting that transportation can also lead to excessive sweat loss, with studies showing sweat rates of 5 litres per hour of travel on a warm day (van den berg 1998).

If the electrolytes lost in sweat are not adequately replaced, a drop in performance can result, as well as clinical issues such as thumps, dehydration and colic.

Electrolytes play key roles in the contraction of muscle fibres and transmission of nerve impulses. Horses without adequate electrolyte levels are at risk of early onset fatigue that may result in reduced stamina. It is also worth noting that horses that train on furosemide will have higher levels of key electrolyte losses, so will require targeted support to help maintain performance levels (Pagan 2014).

There is also evidence to suggest that pre-loading of electrolytes may be beneficial (Waller 2022). For horses in daily work, the addition of electrolytes to the evening feed will not only replace losses but also help optimise levels for the following day’s travel or race. The benefit of providing electrolytes with feed is that it will minimise the risk of the electrolyte salts irritating the stomach lining, which can occur if given immediately after exercise on an empty stomach. Feeding electrolytes when the horse is relaxed back in the stable will also allow them to drink freely, with the added benefit that electrolytes will stimulate the thirst reflex when they are relaxed, ensuring they are adequately hydrated for the following day.

Products should be chosen on the basis of adequate key electrolyte provision as not all products will provide meaningful levels of all the key electrolyte ions.

Muscle soreness

The process of muscle breakdown and repair is a normal adaptive response to training. This process can lead to inflammation and soreness or stiffness after exercise. In humans, there is a well-recognised condition called Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS).

Further research is required to fully understand the impact of DOMS in horses. DOMS is the muscular pain that develops 24–72 hours after a period of intense exercise. There is no pain felt by the muscles at the time of exercise, in contrast to a ‘torn muscle’ or ‘tying-up’ for example.

In humans, DOMS is thought to be the result of tiny microscopic fractures in muscle cells. This happens when doing an activity that the muscles are not used to doing or have done it in a more strenuous way than they are used to.

The muscles quickly adapt to being able to handle new activities, thus avoiding further damage in the future; this is known as the “repeated-bout effect”. When this happens, the micro-fractures will not typically develop unless the activity has changed in some substantial way. As a general rule, as long as the change to the exercise is under what is normally done, DOMS are not experienced as a result of the activity.

In practice, avoiding any post-exercise muscle soreness in a training programme may be unavoidable, as exercise intensity and duration increases. Horses are far from being machines, so there is a fine balance between a programme that gets a horse fit for purpose without some post-exercise muscle discomfort. Physiotherapy, swimming and turnout will all likely benefit horses experiencing muscle discomfort. Whilst non-steroidal anti-inflammatories will always have their place for horses in training, one area of advancement is the use of plant-based phytochemicals to support the anti-inflammatory response (Pekacar 2021). These may have the benefit of not leading to unwanted gastrointestinal side effects and not having prolonged withdrawal times, although this should always be checked with any supplement particularly with the recent update regarding MSM on the BHA prohibited substance list.

Exercise will also lead to a process of muscle cell damage caused by oxidative stress. This is an inflammatory process and recovery from oxidative stress is key to allow for muscle cell repair and growth. Antioxidants are compounds that help recovery and repair of muscle cells following periods of intense exercise. The process of oxidative stress in muscle cells can lead to muscle fatigue and inflammation if left unsupported. Antioxidant supplementation in the form of Vitamin E or plant-based compounds can help protect against excessive oxidative stress and support muscle repair after exercise (Siciliano 1997).

Conclusion

Nutritional management of horses in training is a complex topic, not least as every horse is an individual and so often needs feeding accordingly. Whilst there is a lot of science available on the subject, the ‘art of feeding’ a racehorse—something that trainers and their staff often have in-depth knowledge of— remains an incredibly important aspect. Targeted nutritional supplements undoubtedly have their place, as discussed in, but not limited to, the scenarios above.

Veterinarians, physiotherapists, other paraprofessionals and nutritionists all play a role in minimising health issues and maximising performance. In the quest for optimal performance on the track, nutritional support is one of the cornerstones of the ‘marginal gains’ theory that has long been adopted in elite human athletes. There is no doubt that racehorses themselves are supreme athletes that live by the mantra of Train, Race, Recover, and Repeat.

References

Berger, S. et al (2002). The effect of acid protection in therapy of peptic ulcer in trotting horses in active training. Pferdeheilkunde 27 (1), 26-30,

Loftin, P. et al (2012). Evaluating replacement of supplemental inorganic minerals with Zinpro Performance Minerals on prevention of gastric ulcers in horses. J.Vet. Int. Med. 26, 737-738

McCutcheon, L.J. and geor R.J. (1996). Sweat fluid and ion losses in horses during training and competition in cool vs. hot ambient conditions: implications for ion supplementation. Equine Veterinary Journal 28, Issue S22.

Nieto, J.E. et al (2009). Effect of gastric ulceration on physiologic responses to exercise in horses. Am. J. Vet. Res.70, 787-795.

Pagan, J.D. et al (2014). Furosemide administration affects mineral excretion in exercised Thoroughbreds. In: Proc. International Conference on Equine Exercise Physiology S46:4.

Pekacar, S. et al (2021). Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects of Rosehip in Inflammatory Musculoskeletal Disorders and Its Active Molecules. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 14(5), 731-745.

Rivero, J.-L.L. et al (2007). ‘Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses’. Journal of Applied Physiology 102(5), 1871–1882.

Siciliano, P.D. et al (1997). Effect of dietary vitamin E supplementation on the integrity of skeletal muscle in exercised horses. J Anim Sci.75(6), 1553-60.

Sykes, B. et al (2013). Efficacy of a combination of a unique, pectin-lecithin complex, live yeast, and magnesium hydroxide in the prevention of EGUS and faecal acidosis in thoroughbred racehorses: A randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Equine Veterinary Journal, 45, 16.

van den Berg, J. et al (1998). Water and electrolyte intake and output in conditioned Thoroughbred horses transported by road. Equine Vet J. 30(4), 316-23.

Vatistas, N.J. et al (1999) Cross-sectional study of gastric ulcers of the squamous mucosa in thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet J Suppl. 29, 34–39.

Waller, A.P., and M.I. Lindinger. (2022). Tracing acid-base variables in exercising horses: Effects of pre-loading oral electrolytes. Animals (Basel) 13(1), 73.

Thermoregulation in horses

Article by Adam Jackson - MRCVS

Exertional heat illness (EHI) is a complex disease where thoroughbred racehorses are at significant risk due to the fact that their workload is intensive in combination with the high rate of heat production associated with its metabolism. In order to understand how this disease manifests and to develop preventative measures and treatments, it is important to understand thermoregulation in horses.

What is thermoregulation?

With continuous alteration in the surrounding temperature, thermoregulation allows the horse to maintain its body temperature within certain limits. Thermoregulation is part of the greater process of homeostasis, which is a number of self-regulating processes the horse uses to maintain body stability in the face of changing external conditions. Homeostasis and thermoregulation are vital for the horse to maintain its internal environment to ensure its health while disruption of these processes leads to diseases.

The horse’s normal temperature range is 37.5–38.5°C (99–101°F). Hyperthermia is the condition in which the body temperature increases above normal due to heat increasing faster than the body can reduce it. Hypothermia is the opposite condition, where the body temperature decreases below normal levels as the body is losing heat faster than producing it. These conditions are due to the malfunction of thermoregulatory and homeostatic control mechanisms.

Horses are colloquially referred to as warm-blooded mammals—also known as endotherms because they maintain and regulate their core body, and this is opposite ectotherms such as reptiles. The exercising horse converts stored chemical energy into mechanical energy when contracting various muscles in its body. However, this process is relatively inefficient because it loses roughly 80% of energy released from energy stores as heat. The horse must have effective ways to dissipate this generated heat; otherwise, the raised body temperatures may be life threatening.

Transfer of body heat

There are multiple ways heat may be transferred, and this will flow from one area to another by:

1. Evaporation

The main way body heat is lost during warm temperatures is through the process of evaporation of water from the horse’s body surface. It is a combination of perspiration, sweating and panting that allows evaporation to occur.

Sweating is an inefficient process because the evaporation rate may exceed the body heat produced by the horse, resulting in the horse becoming covered and dripping sweat. This phenomenon occurs faster with humid weather (high pressure).