200 years of horse racing in Germany

Words - Lissa Oliver

Horseracing is the oldest organised sport in Germany and this year it celebrates a major milestone. The very first thoroughbred race in Germany took place in Doberan, on the Baltic Sea, 10 August 1822, this summer marking the 200th anniversary. Around 30 racing clubs have organised a total of 136 race days to mark the celebration.

German-bred racehorses are recognised internationally for their stamina and soundness, which is no accident and links directly to that historic day in Doberan. Breeding selection and breed improvement through tests of performance remains a mandate of the Animal Breeding Act, with the retirement of stallions to stud strictly governed.

Organised racing in Germany was very quickly established. As early as 13 August of the same year, 1822, the Doberan Racing Club was founded, the first of the racing clubs created to oversee the contests. The Berlin Racing Club followed in 1828 and by the 1830s numerous new clubs had been formed across the country.

Today, the Düsseldorf Equestrian and Racing Club has the proud boast of being Germany’s oldest continuously existing racing club, founded in 1844, and in April Düsseldorf racecourse had the honour of hosting the first of the anniversary celebrations.

Another major milestone followed when, in 1858, the French casino owner Edouard Bénazet had the racecourse built in Iffezheim near Baden-Baden. Ten years later, Emperor Wilhelm I attended the official opening of the Hoppegarten racecourse in Berlin, 17 May 1868, which quickly developed into one of the most important racecourses in Europe.

The oldest continuous race in Germany is the Union Race, first held in 1834. Created as a supreme test for three-year-olds it was eventually relegated by the Deutsches Derby. The Norddeutsches Derby, as it was originally known, was established at Hamburg in 1869, becoming the now-familiar Deutsches Derby in 1889. During the wars it was staged at Grunewald in 1919, Hoppegarten in 1943 and 1944, Munich in 1946 and Cologne in 1947. The great Königsstuhl, in winning the Henckel-Rennen, Deutsches Derby and St-Leger in 1979, remains the only horse to win the German Triple Crown.

The first commercial German bookmakers sprang up in the middle of the 19th century and, following the French model, a totaliser was set up in Berlin in 1875. From 1905 to 1922 bookmaker bets were banned in Germany, but since then the Tote and bookmakers have been competing with each other.

The early part of the 20th century saw racing clubs springing up as vigorously as the grass and in 1912 there were more than 100 racecourses in Germany. Obviously, world events saw that blossoming situation change drastically. The First World War represented a turning point in the fate of German racing, but it was the Second World War that had a lasting and damaging impact.

Appropriately, racing returned to West Germany after the war years on 12 August 1945 at Leipzig, but in the German Democratic Republic racing became, at best, a marginal sport. Hoppegarten was nationalised and one of only six racecourses hosting racing.

It was a brighter new start in the West and the racing season resumed in full at Munich in April 1946. A steady resurgence followed, and Cologne developed into the leading training centre, while Hamburg remained the home of the Deutsche Derby.

As with other European racing nations there was little change in the ensuing years, but 1980 marked another significant milestone when Dortmund became the first all-weather track in Europe, for the first time making winter racing under floodlights possible.

Following the reunification of Germany, racing came more into focus with the public and Berlin’s Hoppegarten, in particular, enjoyed renewed popularity. In 2021, the Group 1 LONGINES 131st Grand Prix of Berlin received great international recognition when it was included in the top 100 of the world's best races. However, it is Baden-Baden that is regarded as the leading German racecourse, in terms of betting turnover and also from a sporting, social and international viewpoint, staging popular meetings in spring, summer and autumn.

As already mentioned, the breeding of German thoroughbreds has always been carefully regulated to ensure continuing success. The German breeding industry began around 1800, originally in Mecklenburg. In 1842 the first Deutsche Stud Book was published. It contained 242 breeders who between them kept 779 broodmares. Less than 10% had more than 10 mares. This has hardly changed to this day; there are only a few large stud farms, but many breeders with only one or two mares. Currently, about 460 breeders have around 1,300 broodmares.

One of the great traditional studs is the Prussian State Stud in Graditz, near Leipzig, founded in 1668 and already dedicated solely to thoroughbred breeding by the first half of the 19th century. Twelve Derby winners were raised there from 1886 (Potrimpos) to 1937 (Abendfrieden) and Graditz-produced horses were esteemed to the extent that there were times when they had to carry additional weight to give their rivals a better chance.

The oldest private stud farm is Gestüt Schlenderhan near Cologne, founded in 1869 by Baron von Oppenheim. From 1908 to the present day, Schlenderhan has bred 19 Deutsches Derby winners, most recently In Swoop in 2020. A great example of the success of small-scale German breeders is, of course, 2021 Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe winner Torquator Tasso, bred by Paul H. Vandeberg from his only mare, Tijuana; herself from Schlenderhan breeding.

The 200th anniversary of German racing is being celebrated across the country, with commemorative stamps produced by Deutsches Post. The highlight will be the festivities at Berlin-Hoppegarten racecourse from 12 to 14 August. The three-day anniversary meeting opens with an official ceremony at the Hotel Adlon Kempinski in Berlin and on Saturday evening, 13 August, the Hoppegarten racecourse invites everyone to a big anniversary party. Details available at:

Milestones in gallop racing - German gallop (deutscher-galopp.de)

The story of Never Say Die

By James C. Nicholson

The first Kentucky-bred winner of the Epsom Derby would earn a place in Thoroughbred racing lore and even played a small role in the early history of the most successful musical group of the twentieth century. But he nearly didn’t survive his first night of life.

In late March 1951, John Bell and his wife returned from a night out to find that a new foal had arrived at their leased acreage outside Lexington. Its mother, an undersized daughter of American Triple Crown winner War Admiral named Singing Grass, was exhausted, as was the barn foreman who had helped her with a difficult delivery.

Never Say Die

The unusually large chestnut colt, by Irish-bred stallion Nasrullah, was having trouble breathing as he lay beside his mother. His right foreleg was tucked awkwardly under his body. Concerned that the newborn might not make it, Bell retrieved a bottle of bourbon whiskey from a desk in the tack room. He took a quick nip for himself and poured the rest of the bottle’s contents down the throat of the struggling foal. The elixir revived the woozy colt, which, fittingly, would be named Never Say Die.

After being taught to carry a rider by Bell and his Jonabell Stables team, the colt was sent to the Newmarket training yard of seventy-two-year-old conditioner Joe Lawson, who had twice been British flat racing’s Champion Trainer, and had captured most of England’s top races, but for whom the Derby had proven elusive. The colt’s owner, Robert Sterling Clark, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune, split his horses between Lawson and another trainer named Harry Peacock. Peacock had won a coin flip to determine which man would receive first choice of Clark’s horses that year. Though he liked the look of Never Say Die, he was not interested in training a son of Nasrullah. Nasrullah was well on his way to one of the most outstanding stud careers in history, but the memory of the stallion’s inability to run to his potential because of temperamental idiosyncrasies was still fresh for many British horsemen.

Never Say Die had been a gangly foal, but he filled out to become a lovely, compact, balanced young colt with a slightly better disposition than that of his notorious sire. Though he never displayed the mental peculiarities on the racetrack that Nasrullah had, Never Say Die did develop a reputation for moodiness and difficulty among the humans that cared for him.

A turf writer for the Daily Express observed that Never Say Die had “an excellent, strong, straight pair of hind legs, even if the joints appear to be somewhat rounded. The captious critics might say that he is over-long of his back. Undoubtedly his best points lie in front of the saddle. There is a rhythmical quality about the set of his neck, shoulder, and powerful forearm which is carried down through the flat knees to a hard, clean underpinning.” The handsome colt’s most notable feature was a prominent white blaze that ran the length of his head—from above his eyes to the tip of his nose.

After some encouraging performances as a two-year-old, including a win in the six-furlong Rosslyn Stakes at Ascot and a third-place finish in the Richmond Stakes at Goodwood, Lawson held guarded hope for Never Say Die at three, and believed a talented young rider named Lester Piggott would help the American colt reach his potential.

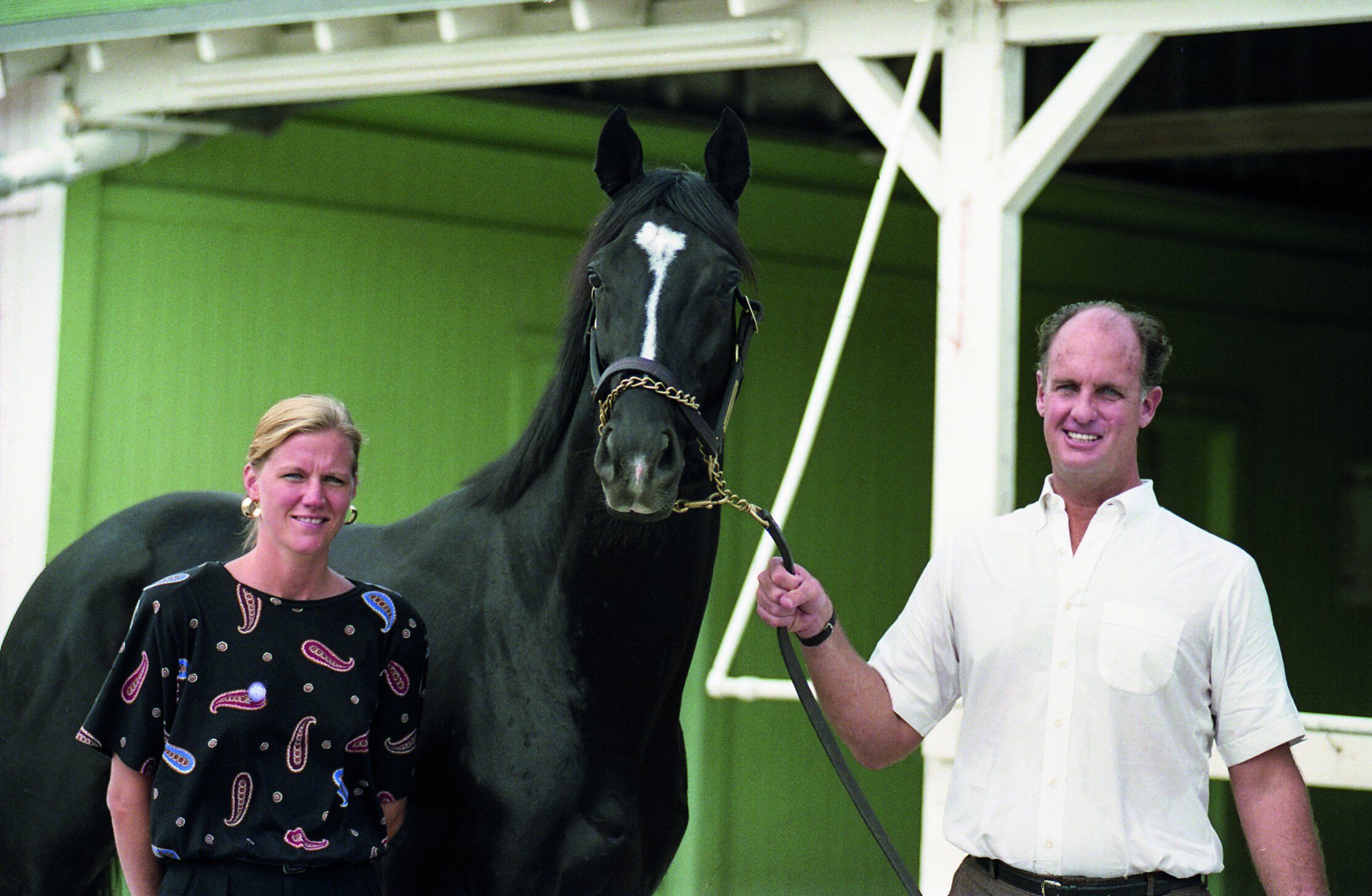

John A. Bell III at Jonabell Farm. Never Say Die’s success helped Bell establish Jonabell Farm as one of the leading Thoroughbred operations in America

If anyone was ever destined to become a jockey, it was Lester Keith Piggott, born in 1935 on Guy Fawkes Day in Oxfordshire. The branches of Piggott’s family tree were littered with jockeys and equestrians, dating back to the 1700s. His grandfather Ernie Piggott had won the Grand National three times as a jockey. Lester’s grandmother came from a long line of riders that included her two Derby-winning brothers. Lester’s father, Keith, was a successful jockey, winning five hundred races over a thirty-year career, before becoming a champion trainer of jumpers. Lester’s mother, Iris, also descended from a long line of top-notch jockeys and trainers and was an accomplished rider in her own right.

Lawson took his time with Never Say Die early in his three-year-old season. With eighteen-year-old Piggott in the irons, the colt began the year with a respectable second-place finish in the Union Jack Stakes at Aintree. He regressed next time out, starting slowly in the seven-furlong Free Handicap at Newmarket, and never factoring in the race. But when stretched out in distance two weeks later for the Newmarket Stakes, Never Say Die gave a performance good enough to convince his owner to give him a shot in the Derby. Though he had tired in the late stages to finish third, he was beaten just a half-length and a head in the ten-furlong test.

Piggott had chosen to ride at Bath that day, and Lawson was inclined to remove him from the Derby-bound colt for his disloyalty. Fortunately for Piggott, the trainer’s first three choices to replace him already had Derby mounts. With the “boy wonder of the turf” again aboard, Never Say Die joined twenty-one rivals on a chilly and damp afternoon at the starting line for the 175th running of the Epsom Derby. Top contenders included Darius, the Two Thousand Guineas victor; Rowston Manor, winner of the Derby Trial Stakes at Lingfield; and the Queen’s colt, Landau. Bookmakers listed Never Say Die as a 33 to 1 long shot. His odds would have been even higher but for the popularity of his young rider and the charm of the colt’s name.

Never Say Die was away quickly from the starting barrier and fell in just behind the first group of front-runners in the early going. He maintained his position, clear of trouble, into Tattenham Corner. Rounding the final turn, Piggott bided time, well off the rail and just behind Rowston Manor, Landau, and Darius. Early in the final straight he eased his mount to the outside. Passing tiring rivals, Never Say Die roared to the front in mid-stretch and strode on for a two-length win, to the astonishment of hundreds of thousands in attendance and millions listening to the BBC radio broadcast.

With his colt’s Derby conquest, Sterling Clark became the first American owner to win the renowned race with an American horse that he bred himself. In the Derby’s long history there had been only one American-born horse to win—Pennsylvania-bred Iroquois, in 1881. No horse born in Kentucky, the commercial breeding center of the American Thoroughbred industry, had ever won the British Classic.

American horsemen were overjoyed. In The Thoroughbred Record, a Kentucky-based weekly publication, columnist Frank Jennings noted that, prior to Never Say Die’s victory, “repeated failure on the part of Americans in the English Derby not only was becoming monotonous but was downright discouraging. Men of less determination and means than Mr. Clark gradually had become reconciled to the idea that a score in the big race at Epsom was virtually impossible with a colt bred and raised on this side of the Atlantic. Never Say Die did a great deal toward changing this thought and at the same time [demonstrated] that American bloodlines, when properly blended with those of foreign lands, can hold their own in the top company of the world.”

The seventy-six-year-old Clark had lived a remarkable life. He had served as a U.S. Army officer during the Spanish-American War and the Boxer Rebellion, led a research expedition through rural Asia, and built one of the finest private collections of European painting masterpieces in the world. In his later years, he created the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute near the campus of Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. But nothing provided him greater satisfaction than that historic Derby triumph.

Clark learned the race result via telephone. The winning owner was in a New Your City hospital, having chosen not to postpone some scheduled tests. But he was often reluctant to attend the races even when circumstances did not preclude his presence. Large race day crowds made him nervous.

An impromptu champagne celebration was organized in the hospital room, and Clark proposed a series of toasts. A small group of friends and family first drank to Piggott and Lawson. Then they saluted Bell, the young Kentucky horseman whose fast thinking had helped the Derby champion survive his first night and at whose Jonabell Farm the colt was raised and introduced to a saddle. For Bell, born into a wealthy Pittsburgh family that lost its banking and coal fortune amidst scandal when he was still a child, Never Say Die’s Derby score provided a vital piece of early publicity for his fledgling equine operation that would eventually become one of the most respected in the world and, following a 2001 sale to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, home to Darley’s North American stallions.

In Liverpool, two hundred thirty miles northwest of Epsom, a middle-class housewife named Mona Best listened to the BBC broadcast of the Derby on the family radio. When the results were announced, she jumped for joy. Mona had pawned her jewelry to finance a bet on Never Say Die because she fancied his name. With her winnings, she put a down payment on the house she had long admired, a large fifteen-room Victorian at 8 Hayman’s Green in the West Derby section of Liverpool.

Before it was fixed up, children called it “Dracula’s Castle.” But it had an unusually spacious cellar where, after renovations, Mona opened the Casbah Coffee Club as a place where her son Pete and his friends could congregate. The idea proved much more popular with the neighborhood youth than she had imagined, however, and soon the club had a thousand members who paid an annual fee of 12 ½ pence.

A group of teenaged musicians called the Quarrymen played the opening night in late August 1959, after helping to paint the walls and the ceilings that summer. Their set included American rock n roll favorites such as Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” and Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven.” The group’s name was a nod to Quarry Bank High School, which their lead singer, John Lennon, had attended. Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ken Brown rounded out the lineup.

Mona was sufficiently impressed with the four guitarists to offer them a weekly engagement at the Casbah. Their compensation was to be three pounds cash, and all the Coca-Cola and crisps that the boys could consume. Soon the young musicians dropped Brown, changed their name to the Beatles, and were looking for a drummer to join them for an extended booking in Germany. Pete became the Beatles’ first regular drummer and played with the band for two years, including their three formative stints in Hamburg, before being replaced by Ringo Starr at the precipice of international celebrity.

Whereas the Beatles were four lads from Liverpool who took America by storm with music that had distinctly American roots, Never Say Die was an American-born horse with a pedigree dominated by European influence that won England’s greatest horse race. Although Never Say Die’s Derby victory did not have the immediate impact on Thoroughbred racing that the Beatles had on western culture, his win at Epsom in 1954 was an important signal of change that had been taking place for decades. Vast fortunes with roots in the American industrial expansion of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries had made it possible for wealthy Americans and their heirs to purchase many of Europe’s top Thoroughbreds from their aristocratic owners and import them to America for breeding purposes. By the 1970s, American racehorses produced from those European bloodlines would be winning Europe’s top races with some regularity, and with lasting ramifications for the international Thoroughbred industry.

Remembering Sunday Silence and his lasting global influence

By Nancy Sexton

For over a quarter of a century, there has been an air of inevitability within Japanese racing circles. Sunday Silence dominated the sire standings in Japan for 13 straight years, from 1995 to 2007—his last championship arriving five years after his death. He was a true game changer for the Japanese industry, not only as a brilliant source of elite talent but as a key to the development of Japan as a respected racing nation. Any idea that his influence would abate in the years following his death was swiftly quashed by an array of successful sire sons and productive daughters. In his place, Deep Impact rose to become a titan of the domestic industry. Others such as Heart’s Cry, Stay Gold, Agnes Tachyon, Gold Allure and Daiwa Major also became significant sires in their own right. Added to that, Sunday Silence is also a multiple-champion broodmare sire and credited as the damsire of 203 stakes winners and 18 champions. “Thoroughbreds can be bought or sold,” says Teruya Yoshida of Shadai Farm, which bought Sunday Silence out of America in late 1990 and cultivated him into a global force. “As Nasrullah sired Bold Ruler, who changed the world’s breeding capital from Europe to the U.S., one stallion can change the world. Sunday Silence is exactly such a stallion for the Japanese thoroughbred industry.”

Sunday Silence ant Pat Valenzuela winning the 1989 Kentucky Derby

Sunday Silence has been dead close to 20 years, yet the Japanese sires’ table remains an ode to his influence. In 2021, Deep Impact landed his tenth straight sires’ championship with Heart’s Cry and Deep Impact’s rising son Kizuna in third and fourth. Six of the top 11 finishers were sons or grandsons of Sunday Silence. Deep Impact was also once again the year’s top sire of two- and three-year-olds. Against that, it is estimated that up to approximately 70% of the Japanese broodmare population possess Sunday Silence in their background. All the while, his influence remains on an upswing worldwide, notably via the respect held for Deep Impact. A horse who ably built on the international momentum set by Sunday Silence, his sons at stud today range from the European Classic winners Study Of Man and Saxon Warrior—who are based in Britain and Ireland—to a deep domestic bench headed by the proven Gp 1 sires Kizuna and Real Impact alongside Shadai’s exciting new recruit Contrail. In short, the thoroughbred owes a lot to Sunday Silence.

Inauspicious beginnings

Roll back to 1988, however, and the mere idea of Sunday Silence as one of the great fathers of the breed would have been laughable. For starters, he almost died twice before he had even entered training. The colt was bred by Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds Ltd in Kentucky with appealing credentials as a son of Halo, then in his early seasons at Arthur Hancock’s Stone Farm. Halo had shifted to Kentucky in 1984 as a middle-aged stallion with a colourful existence already behind him. By Hail To Reason and closely related to Northern Dancer, Halo had been trained by Mack Miller to win the 1974 Gr 1 United Nations Handicap.

It was those bloodlines and latent talent that prompted film producer Irving Allen to offer owner Charles Englehard a bid of $600,000 for the horse midway through his career. Allen’s idea was to install Halo in England at his Derisley Wood Stud in Newmarket; and his bid was accepted only for it to be revealed that his new acquisition was a crib-biter. As such, the deal fell through, and Halo was returned to training, with that Gr 1 triumph as due reward.

Queen Elizabeth II meets Halo

Would Halo have thrived in England? It’s an interesting question. As it was, he retired to E. P. Taylor Windfields Farm in Maryland, threw champion Glorious Song in his first crop, Kentucky Derby winner Sunny’s Halo in his third and Devil’s Bag—a brilliant two-year-old of 1983—in his fourth. Devil’s Bag’s exploits were instrumental in Halo ending the year as North America’s champion sire. Within months, the stallion was ensconced at Stone Farm, having been sold in a deal that reportedly valued the 15-year-old at $36 million. Chief among the new ownership was Texas oilman Tom Tatham of Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds. In 1985, Tatham sent the hard-knocking Wishing Well, a Gr2-winning daughter of Understanding, to the stallion. The result was a near black colt born at Stone Farm on March 26, 1986.

It is part of racing’s folklore how Sunday Silence failed to capture the imagination as a young horse—something that is today vividly recalled by Hancock.

“My first recollection of him was as a young foal,” he recalls. “He was grey back then—he would later turn black.

“I was driving through the farm, and I looked into one of the fields and saw this grey colt running. The others were either nursing or sleeping, but there was this colt running and jumping through the mares.

"We had a number of foals on the place at the time, and I wasn’t sure which one it was, so I rang Chester Williams, our broodmare manager. I said, ‘Hey Chester, who is this grey foal in 17?’ And he told me it was the Wishing Well colt. He was flying—he would turn at 45 degree angles and cut in and out of the mares. And I remember thinking even then, ‘Well, he can sure fly.’

“Then on Thanksgiving Day later that year, he got this serious diarrhea. We had about 70 foals on the farm, and he was the only one that got it; we had no idea where he got it from. Anyway, it was very bad. I called our vet, Carl Morrison, and between 9 a.m. and midday, we must have given him 23 litres of fluids.

“We really thought he was going to die, but Sunday Silence just wouldn’t give up. Obviously it set him back some; he was ribby for a few weeks. But I have never seen anything like it in a foal during 50 years at Stone Farm, and at Claiborne before then; and I remember thinking then that it was a spooky thing for him to get it and then to fight through it the way he did.”

Arthur Hancock

As Hancock outlines, Sunday Silence was very much Halo’s son—not just as a black colt with a thin white facial strip but as a tough animal with a streak of fire. Halo had arrived from Maryland with a muzzle and a warning. Confident that a muzzle was an overreaction, Stone Farm’s stallion men worked initially without it, albeit against Hancock’s advice. It wasn’t long until the muzzle went back on. Not long after his arrival, Halo ‘grabbed the stallion man Randy Mitchell in the stomach and threw him in the air like a rag doll.’

“Halo then got on his knees on top of Randy,” recalls Hancock, “and began munching on his stomach. Virgil Jones, who was with Randy, starts yelling at Halo and hitting him with his fist. Halo let go, and they managed to get him off. “After that, the muzzle stayed on.”

Sunday Silence possessed a similar toughness. Indeed, that mental hardiness is a trait that continues to manifest itself in the line today, although not quite to the danger level of Halo.

“Sunday Silence had a lot of guts and courage, even then,” remembers Hancock. “I remember being down at the yearling barn before the sale and hearing this yell. It was from one of the yearling guys, Harvey. Sunday Silence had bitten him in the back—I’d never had a yearling do it before then and haven’t had one since.”

He adds: “When he came back here after his racing days, we had a photographer come to take some shots of him. Sunday Silence was in his paddock, and we were trying to get him to raise his head. I went in there and shook a branch to get his attention. Well, he looked up, bared his teeth and started to come after me—he was moving at me, head down like a cat. And I said, ‘No you’re ok there boy; you just continue to graze’ and let him be.

“He was Halo’s son, that’s for sure, because Wishing Well was a nice mare. Sunday Silence had a mind of his own, even as a yearling. I remember we couldn’t get him to walk well at the sales because he’d pull back against the bit all the time.”

It was that mental toughness and the memory of Sunday Silence flying through the fields as a young foal that remained with Hancock when the colt headed to the Keeneland July Sale. Then an individual with suspect hocks—a trait that still sometimes manifests itself in his descendants today—he was bought back on a bid of $17,000.

Staci and Arthur Hancock

“I thought he’d bring between $30,000 and $50,000,” he says. “So when it was sitting at $10,000, I started bidding and bought him back at $17,000. I took the ticket to Tom Tatham out the back of the pavilion and said, ‘Here, Tom, he was too cheap; I bought him back.’ And Tom said, ‘But Ted Keefer [Oak Cliff advisor] didn’t like him, and we don’t want him.’

“I remember we had another one that was about to sell, so I just said, ‘Ok Tom,’ put the ticket in my shirt pocket, walked away and thought, ‘Well, I just blew another $17,000.’

Another scrape with death

Hancock then tried his luck at the two-year-old sales in partnership with Paul Sullivan. The colt was sent to Albert Yank in California and catalogued to the Californian March Two-Year-Old Sale at Hollywood Park, again failed to sell—this time falling to World Wide Bloodstock (aka Hancock)—on a bid of $32,000, well below his owner’s valuation of $50,000.

“I told Paul and he said, ‘Well, I’ll take my $16,000 then,’” recalls Hancock.

So the colt was loaded up for a return trip to Kentucky. Then more ill-luck intervened. The driver suffered a fatal heart attack while on a north Texas highway, and the van crashed, killing several of its load. Sunday Silence survived but was injured.

“Sunday Silence was in the vets for about a week,” says Hancock. “He could hardly walk, and then Carl Morrison rings me and says, ‘Arthur, I think he’s a wobbler.’ I said, ‘What are you going to do?’ He said that all he could do was leave him in a paddock and see what happened.

“So he left him out there, and about a week later, he rings me and says, ‘You need to come to barn 16 and see this Wishing Well colt.’ It was unbelievable. I went down there, and there he was, ripping and running around just like he was a foal. It was a miracle—a spooky thing.”

Therefore Sunday Silence had already lived a pretty full life by the time he joined Charlie Whittingham in California. A true master of his profession, Whittingham handled over 250 stakes winners during his 49 years as a trainer, among them such champions as Ack Ack, Ferdinand and Cougar alongside the European imports Dahlia and Exceller. Appropriately, Cougar would go on to stand at Stone Farm, where he sired Hancock’s 1982 Kentucky Derby winner Gato Del Sol.

“Charlie Whittingham had seen Sunday Silence in California and rang me to ask about him,” says Hancock. “I told him I’d sell him half to $25,000. And he said, ‘But you bought him back for $32,000.’ Well the year before, we’d had Risen Star [subsequent winner of the Preakness and Belmont Stakes] go through Keeneland for $250,000. Charlie had asked about taking half of him, but we had wanted $300,000, so said, ‘Sure you can buy half for $150,000.’ And he had declined.

“I reminded him of that, and he chuckled and said, ‘Well, I’d better take it this time.’”

He adds: “Charlie was a brilliant horseman with a lot of experience. He was very smart. He had a sixth sense about horses. And he had great patience, like those great trainers do. Without Charlie, I don’t think Sunday Silence would have reached the level that he did. He just took his time with him.”

Whittingham paid Hancock $25,000 for a half share in the colt and later sold half of that share to a friend, surgeon Ernest Galliard. Within no time, that looked like a good bit of business.

It is a fine reflection of the trainer and his staff, in particular work rider Pam Mabes, that Sunday Silence’s temperament was successfully honed. In Jay Hovdey’s biography of the trainer, the colt is likened to ‘Al Capone singing with the Vienna Boys Choir’—his morning exercise routinely punctuated by bad behaviour.

“They’d take him out every day before dawn,” recalls Hancock. “I remember he had a thing about grey lead horses. Every time he saw one, he’d just go after it.

“Charlie called me one morning—4 a.m. his time; he’d always get to the barn at 4 a.m. I answered, thinking, What’s he doing calling me at this time? I said, ‘Hey Charlie, what you doing?’ He said, ‘Just waiting on the help.’ I knew he had something on his mind. Then he said, ‘You know what, this big black son of a bitch can run a little’—Charlie was a master of the understatement.’”

Brought along steadily by Whittingham, Sunday Silence romped to a 10-length win second time out at Hollywood Park in November 1988. And after running second in an allowance race, he returned at three to win his first two races: an allowance and the San Felipe Handicap.

While he was emerging as a potential Classic candidate on the West Coast, Ogden Phipps’ homebred Easy Goer was laying down the gauntlet in New York. A handsome red son of Alydar with regal Phipps bloodlines trained by Shug McGaughey, Easy Goer was evoking comparisons with Secretariat, capturing the Gr1 Cowdin and Champagne Stakes at two before running out the 13-length winner of the Gotham Stakes in a record time early on at three. To many observers, he appealed as the likely winner of the Kentucky Derby, if not the Triple Crown. Indeed, theirs would become an east-west rivalry that would enthral racegoers during the 1989 season.

The pair met for the first time in the Kentucky Derby. Sunday Silence, partnered by Pat Valenzuela, was fresh off an 11-length win in the Santa Anita Derby. Easy Goer, though, had won the Wood Memorial in impressive style and was therefore the crowd’s choice. Yet on a muddy track, Sunday Silence had the upper hand, winning with authority over an uncomfortable Easy Goer in second.

“Of all his races, the Kentucky Derby stands out,” says Hancock. “We’d been fortunate enough to win it with Gato Del Sol, and I’m a Kentuckian; so to win it again meant a lot. “It was an extremely cold day, it was spitting snow, and Sunday Silence was weaving all the way down the stretch. Yet he still won.”

With many feeling that the track had not played to Easy Goer’s strengths, he was fancied to turn the tables in the Preakness Stakes. However, once again, Sunday Silence emerged as the superior, albeit following an iconic, eye-balling stretch duel. Easy Goer did gain his revenge in the Belmont Stakes, making the most of the 1m4f distance and Belmont Park’s sweeping turns to win by eight lengths. The Triple Crown was gone, but Sunday Silence would later turn the tables in the Breeders’ Cup Classic, where his ability to deploy tactical speed at a crucial moment turned out to be a winning move against his longer-striding rival.

Charlie Whittingham and wife Peggy with jockey Pat Valenzuela after winning the 1989 Preakness Stakes

“The Breeders’ Cup just sealed everything—champion three-year-old and Horse of the Year,” says Hancock. “It was the great showdown. Chris McCarron was able to use him at just the right time and Easy Goer, with that long stride of his, was closing. It was a great race.” Crowned Horse of the Year, Sunday Silence underwent arthroscopic knee surgery which delayed his four-year-old return to June, when he won the Californian Stakes. A head second to Criminal Type in the Hollywood Gold Cup next time out brought the curtain down on a spectacular career.

No takers

Sunday Silence in the paddock at Belmont Park

Plans called for Sunday Silence to join his sire Halo at Stone Farm. A wonderful racehorse who danced every dance, there were grounds for thinking that Sunday Silence would be an asset to the Kentucky bloodstock landscape. But breeding racehorses even then also adhered to commercial restrictions, and as a cheap yearling with suspect hocks and an underwhelming female line, he did little to spark interest. This was in contrast to Easy Goer, who retired to much fanfare at Claiborne Farm.

“We tried to syndicate him and called people everywhere—Kentucky, England, France, and the answer was always the same,” says Hancock. “It became apparent very quickly that people wouldn’t use him.

“It was spread around the industry that he was a fluke, another Seabiscuit or Citation who could run but that would be no good at stud. It was said that he was crooked, which he wasn’t, and that he was sickle-hocked, which he was as a young horse but grew out of. He was an ugly duckling that grew into a swan.

“We had three people on the books to take shares and two that would send mares. Then I spoke to my brother Seth at Claiborne, and he had 40 contracts to send out for Easy Goer.

“At the same time, [U.S. President] Ronald Reagan changed the tax laws, and land became worth a lot less, as did shares in horses.”

The Yoshidas had already bought into the horse and suddenly, Hancock was left with little choice.

“At the same time, I got a call from a representative of Teruya Yoshida saying that Shadai would be interested in buying the whole horse,” he says. “They were offering $250,000 per share. I talked to a number of people about it—Bill Young at Overbrook Farm, Warner Jones; and they all said the same thing: that it was a no-brainer to sell.

“At the end of the day, I had two contracts and three shares sold. I owed money. I had to sell.

“The day he left, I loaded him up myself; and I don’t mind admitting that when that van went down the drive, I cried.”

He adds: “Basically, the Japanese outsmarted everybody.”

An immediate success

Out of a first crop of 67 foals, Sunday Silence sired 53 winners. A total of 22 of 36 starters won at two, led by champion two-year-old Fuji Kiseki, whose success in the Gr1 Asahi Hai Futurity set the scene for events to come. A tendon injury restricted Fuji Kiseki to just one further start when successful in a Gr2 the following year. Yet that failed to stop the Sunday Silence juggernaut.

Genuine and Tayasu Tsuyoshi ran first and second in the Japanese 2,000 Guineas and later dominated the Japanese Derby, with Tayasu Tsuyoshi turning the tables. Dance Partner also landed the Japanese Oaks. As such, Sunday Silence ended 1997 as Japan’s champion sire despite the presence of only two crops.

That first crop would also come to include Marvelous Sunday, who led home a one-two for his sire in the 1997 Gp 1 Takarazuka Kinen. In no time at all, Sunday Silence had sealed his place as a successor to earlier Shadai heavyweight Northern Taste.

“I believe Sunday Silence was a stallion that possessed the potential to be very successful anywhere in the world,” reflects Teruya Yoshida. “We were just lucky to be able to introduce him to Japan as a stallion.

“He changed the Japanese breeding industry completely, especially as he sired successful sons as race horses and stallions. Those sons have again sired successful grandsons.

“It is extraordinary that one stallion continued to produce good quality stallions over three generations. Today, it is said that approximately 60-70% of the Japanese broodmares have Sunday Silence in their female lines.”

Another top two-year-old, Bubble Gum Fellow, emerged from his second crop alongside a second 2,000 Guineas winner in Ishino Sunday and St Leger hero Dance In The Dark. Stay Gold, Sunday Silence’s first real international performer of note by virtue of his wins in the Hong Kong Vase and Dubai Sheema Classic, followed in his third while another Japanese Derby winner followed in his fourth in Special Week, also successful in the Japan Cup.

And so it continued. In all, his stud career came to consist of six Japanese Derby winners (Tayasu Tsuyoshi, Special Week, Admire Vega, Agnes Flight, Neo Universe and Deep Impact), seven 2,000 Guineas winners (Genuine, Ishino Sunday, Air Shakur, Agnes Tachyon, Neo Universe, Daiwa Major and Deep Impact), four St Leger winners (Dance In The Dark, Air Shakur, Manhattan Cafe and Deep Impact) and three 1,000 Guineas winners (Cherry Grace, Still In Love and Dance In The Mood). While a number of those good Sunday Silence runners became fan favourites, there’s no doubt that the best arrived posthumously in the champion Deep Impact. A member of his penultimate crop and out of the Epsom Oaks runner-up Wind In Her Hair, Deep Impact swept the 2005 Japanese Triple Crown and another four Gp 1 races, including the Japan Cup and Arima Kinen, at four. One of Japan’s most popular horses in history, he also ran third in the 2007 Arc.

Fittingly, Deep Impact was also quick to fill the void left at Shadai by his sire’s death from laminitis in 2002.

International acclaim

The Japanese bloodstock industry during the mid-1990s was still relatively isolated from the rest of the world, better known certainly in Europe as the destination for a slew of Epsom Derby winners. Sunday Silence would change all that.

As word of his dominance at stud grew, so did international interest. Teruya Yoshida was swift to capitalise. In 1998, he sent his homebred Sunday Silence filly, Sunday Picnic, to be trained in Chantilly by André Fabre. It was a successful endeavour as the filly won the Prix Cleopatre and ran fourth to Ramruma in the Oaks. By that stage, Shadai had also entered into a partnership with John Messara of Arrowfield Stud with the principal idea of breeding mares to Sunday Silence on southern hemisphere time. Again, the move proved to be a success. Out of a limited pool of Australian-bred runners, Sunday Silence threw the 2003 AJC Oaks heroine Sunday Joy, who would go on to produce eight-time Gp 1 winner More Joyous and Listed winner Keep The Faith, subsequently a Gp 1 sire.

Sheikh Mohammed also joined the fray, notably by sending a relation to Miesque, the Woodman mare Wood Vine, to Sunday Silence in 1998. The resulting foal, the Irish-bred Silent Honor, was trained by David Loder to win the 2001 Cherry Hinton Stakes at Newmarket. Silent Honor was the opening chapter of a successful association for the Sheikh with Sunday Silence that also came to include Godolphin’s 1,000 Guineas runner-up Sundrop, a JRHA Select Foal Sale purchase, and homebred Gp 3 winner Layman. Layman was foaled in the same 2002 crop as the Wertheimer’s high-class miler Silent Name. Initially trained in France by Criquette Head-Maarek, Silent Name was a dual Listed winner before heading to the U.S., where he won the Gr 2 Commonwealth Breeders’ Cup for Gary Mandella. Similarly, patronage of Sunday Silence also reaped rewards for the Niarchos family as the sire of their influential producer Sun Is Up, subsequently the dam of their top miler Karakontie. At the same time, several Japanese-trained horses were advertising the stallion to good effect on a global scale, notably Zenno Rob Roy, who ran a close second in the 2005 Juddmonte International, and Heart’s Cry, who was third in the King George a year later.

Sunday Silence at Shadai Stallion Station, Japan

Sire of sires

Meanwhile, it was becoming very apparent just how effective Sunday Silence was becoming as a sire of sires. Shadai was initially home to plenty of them, including the short-lived Agnes Tachyon, who left behind a real star in champion Daiwa Scarlet, and Fuji Kiseki, the sire of champions Kinshasa No Kiseki and Sun Classique. Stay Gold’s successful stud career was led by the household names Orfevre, who ran placed in two Arcs and is now a proven Gp 1 stallion for Shadai, and Gold Ship. Japan Dirt Derby winner Gold Allure became a leading dirt sire—his record led by champions Copano Rickey, Espoir City and Gold Dream. Manhattan Café is the sire of five Gp 1 winners. As for Special Week, he sired champion Buena Vista and Gr 1 winner Cesario, now regarded as something of a blue hen.

Those sons still in production are entering the twilight years of their stud career. The death of Deep Impact in July 2019 robbed Japan of its international heavyweight stallion. Similarly, the announcement that fellow Shadai stallion Heart’s Cry would be retired ahead of the 2021 season removed a very able substitute. Often in the shadow of Deep Impact, Heart’s Cry evolved into an exceptional sire for whom an international profile consisted of the British Gp 1 winner Deirdre, American Gr 1 winner Yoshida and Japanese champion Lys Gracieux, the 2019 Cox Plate heroine.

However, another Shadai stallion, Daiwa Major, remains in service at the age of 21. Well regarded as a fine source of two-year-olds and milers, he earned international recognition in 2019 as the sire of Hong Kong Mile winner Admire Mars, now also a Shadai stallion. Neo Universe, best known as the sire of Dubai World Cup winner Victoire Pisa, and Zenno Rob Roy are also proven Gp 1 sires as is Deep Impact’s brother Black Tide, the sire of champion Kitasan Black. The latter is also now based at Shadai and the sire of Gp 2 winner Equinox out of his first crop of two-year-olds.

As such, even without Deep Impact, Sunday Silence’s influence as a sire of sires would have been immense. Deep Impact, however, took matters to another level. To date, he is the sire of 53 Gp 1 or Gr 1 winners. As far as Japan is concerned, they cover the spectrum, ranging from Horse of the Year Gentildonna to the 2020 Triple Crown hero Contrail—one of seven Japanese Derby winners by the stallion—and a host of top two-year-olds. Significantly, Deep Impact had been exposed to an international racing audience when third past the post in the 2007 Arc and that played out in a healthy level of outside support when he retired to Shadai for the 2008 season.

For the Wildenstein family, that reaped major rewards in the form of their Poule d’Essai des Pouliches heroine Beauty Parlour, her Listed-winning brother Barocci and French Gp 3 winner Aquamarine. That early success, as well as his growing reputation in Japan, helped to pique the attention of Coolmore. The Irish powerhouse began sending mares in 2013 and were swiftly rewarded by the 2,000 Guineas winner Saxon Warrior, now part of the Coolmore roster in Ireland, and the Gp 1-placed September out of a limited pool of foals. The Prix de Diane heroine Fancy Blue followed in 2020.

Yet better was to come in 2021 in the top three-year-old Snowfall. Bred by Coolmore in Japan out of Best In The World, a high-class Galileo sister to Found, the filly made giant strides from two to three for Aidan O’Brien to sweep the Epsom, Irish and Yorkshire Oaks. Her wide-margin victories in those summer highlights placed Snowfall in rarefied company while further illustrating just how well Deep Impact clicked with some of those high-flying Galileo mares. The same cross has one final chance to shine through the stallion’s last, small crop which includes two-year-olds out of the top Ballydoyle race mares Rhododendron, Minding and Hydrangea. Aidan O’Brien’s yard also houses a brother to Saxon Warrior who is out of the top two-year-old Maybe. Similarly, the Niarchos family, who patronised him from the outset, bred Le Prix du Jockey Club hero Study Of Man, whose Classic campaign in 2018 coincided with that of Saxon Warrior’s. Indeed, Deep Impact was at the height of his international powers when succumbing to a neck injury at the age of 17 in the summer of 2019.

Global exposure

While Deep Impact would build on the global foundations laid by his sire, there was a determination during the intervening years between Sunday Silence’s death and Deep Impact’s own success to expose the blood to a global audience. Chief among them was French-based agent Patrick Barbe, who sourced a number of sons to stand in France, and Frank Stronach, who purchased Silent Name to stand at his Adena Springs Farm. Barbe was the force behind importing an eclectic group of Sunday Silence horses to stand at Haras de Lonray during the mid-2000s. They were invariably priced towards the lower end of the market, yet Barbe was rewarded for his foresight, in particular through the addition of Divine Light, whose first French crop yielded the 1000 Guineas and Cheveley Park Stakes heroine Natagora.

“I have worked with Shadai for over 35 years,” he says, “and I thought it would be interesting to bring the Sunday Silence bloodline to Europe—it hadn’t been tried very much at the time. It can be difficult to educate breeders about different blood, but people had already had slight exposure to Sunday Silence, so it wasn’t too bad.

“Rosen Kavalier was one of the first we brought over. Then we imported Divine Light. Teruya Yoshida had mentioned to me that he thought he was going to do well at stud, as he had been an extremely good sprinter. But he covered only nine mares in his first season in Japan. So we brought him to France, and in his first crop, he sired Natagora.”

As fate would have it, Natagora’s true ability came to light in the months following his sale to the Jockey Club of Turkey. Divine Light left behind just under 100 foals from his time in France and went on to enjoy further success in Turkey as the sire of champion My Dear Son.

“Divine Light was a good-looking horse,” says Barbe. “He was out of a Northern Taste mare and was compact—very similar to Northern Dancer.” He adds: “Sunday Silence was a phenomenal sire, but he also had a pedigree that was similar to Northern Dancer. I feel that was the reason that he did very well with Northern Taste, who was obviously also inbred to Lady Angela [the dam of Nearctic] himself.”

Divine Light wasn’t the only success story out of the French Sunday Silence experiment. While Rosen Kavalier was compromised by fertility problems, Gp 3 winner Great Journey sired several smart runners, while Gp 2 winner Agnes Kamikaze left behind a clutch of winners.

“Great Journey was a very good racehorse and became a consistent sire,” says Barbe. “He did well as the sire of Max Dynamite—a very good stayer—and Soleil d’Octobre, who won two Listed races.”

Today, the sole son of Sunday Silence available in either Europe or North America is Silent Name. Now 20 years old, he has found his niche within the Canadian market as a source of durable, talented runners—in a nutshell, what we have come to expect from the sireline.

Silent Name

Despite never standing for more than C$10,000, Canada’s three-time champion sire is responsible for over 30 black-type winners, making him the nation’s leading sire of a lifetime of stakes winners. They include champion sprinter Summer Sunday, Brazilian Gp 1 winner Jaspion Silent and last year’s Gp 1 Highlander Stakes winner Silent Poet. So although entering the veteran stage of his stud career, momentum behind the stallion continues to remain robust at a fee of C$7,500, as Adena Springs North manager Dermot Carty explains.

“Silent Name started out with us in Kentucky, but in 2008, we decided to bring him to Canada along with Sligo Bay,” he says. “He got three good books off the bat. At the same time, he shuttled to Brazil, and then just as his first Kentucky crop hit, he was sent to New York [where he spent two seasons with McMahon of Saratoga Thoroughbreds].

“I pleaded to bring him back to Canada. People were starting to buy them, they were liking them, and the smaller trainers were doing well with them.

“He’s a really good-looking horse—strong, a little bit sickle-hocked but with good bone. And he’s a tough horse, as tough as they go.

“When we bought him, he was really the only big horse in the pedigree, but it’s a typical Wertheimer family, and it’s improved a lot since then.” In fact, Silent Name is a half-brother to Galiway—a current rags-to-riches story of the French scene whose early crops include last year’s Qipco British Champions Stakes winner Sealiway.

“He’s out of a Danehill mare who is out of a Blushing Groom mare who is out of a Raja Baba mare,” adds Carty. “They’re all big influences.

“A lot of them can run on Polytrack, but they also excel on turf.

“He was the leading sire in Canada for three years straight; the last horse to do that was Bold Executive. Frank has sent a pile of mares to him in recent years and done very well. He’s going to get you a tough horse—people who like to race like him.”

Walmac Farm in Kentucky also made an early foray into Sunday Silence blood with the acquisition of Hong Kong Gp 1 winner Hat Trick in 2008. Latterly based at Gainesway Farm, Hat Trick threw top French two-year-old Dabirsim in his first crop and in turn, that horse sired Albany Stakes winner Different League out of his own debut crop. Noted for siring stock that comes to hand quickly, Dabirsim remains popular at Haras de Grandcamp in Normandy, also home to Deep Impact’s talented son Martinborough. Hat Trick died in 2020 and today, Kentucky representation of the Sunday Silence line relies on the young WinStar stallion Yoshida. A son of Heart’s Cry, he was sourced out of the JRHA Select Sale and went on to land the 2018 Woodward Stakes. He was popular in his first season at stud in 2020, covering 145 mares; and his first foals sold for up to $150,000 at the Kentucky winter breeding stock sales.

Fruitful experiment

Meanwhile, the retirements of Saxon Warrior to Coolmore in Ireland and Study Of Man to Lanwades Stud in Newmarket provide European breeders with quality access to Deep Impact blood. Saxon Warrior’s first crop sold for up to €540,000 as yearlings last year and are now in the yards of Aidan O’Brien, William Haggas and Mark Johnston among others.

The first crop of Study Of Man are yearlings of 2022. As would be expected from a Niarchos homebred who stands at Lanwades Stud, he is being well supported by his powerful connections, as highlighted by the stud’s owner Kirsten Rausing in a piece with The Owner Breeder magazine last June.

STUDY OF MAN

“I have sent him all my best mares,” she said. “I have nine from the Alruccaba family and a number of others from different families, including a very nice filly out of [Gp 1 winner] Lady Jane Digby and others out of Cubanita [a dual Gp 3 winner] and Leaderene [dam of current Australian stakes winner Le Don De Vie].

“It’s early days, but he looks to be a true-breeding bay. I would also say that a few of them look to have a bit of Sunday Silence about them.”

From the Niarchos’ point of view, utilising Study Of Man allows them to tap into inbreeding to his granddam, the family’s excellent miler and blue hen Miesque. Hers is one of the finest families worldwide and it is indicative of the high regard in which the Niarchos held Sunday Silence that they chose to support him with several members of the family.

“The relationship between the Niarchos family and Shadai dates back to when they bought Hector Protector from us,” recalls Alan Cooper, racing manager to the Niarchos family. “We had breeding rights in the horse, and we said, well we better send some mares to Japan and use him, which worked out well as we went on to breed [champion] Shiva.

“And that led us to using Sunday Silence. The Sunday Silence adventure was very fruitful. It was lovely to get some fillies by him, and we’re still benefitting today from them.”

Among the mares sent to Sunday Silence was Miesque’s Listed-winning daughter Moon Is Up. The resulting foal, Sun Is Up, never ran but went on to throw Karakontie, whose three Gp 1 victories included the Poule d’Essai des Poulains and Breeders’ Cup Mile. Study Of Man is out of Miesque’s Storm Cat daughter Second Happiness while another mare, Metaphor, foaled the Listed-placed Celestial Lagoon, in turn the dam of Dante Stakes runner-up Highest Ground.

“We also obviously had a lot of success breeding from Deep Impact through Study Of Man,” says Cooper. “We also have a filly named Harajuku, who won the Prix Cleopatre last year. Another Deep Impact that we bred, Dowsing, is now at stud in Indiana.

“It’s been a very good experience breeding in Japan. The Sunday Silence line seems to have a bit of character, but I think as with anything to do with Halo, if they’re good, they’re very, very good.”

The Niarchos family are also in the privileged position of owning a two-year-old from the final, small crop of Deep Impact. The filly in question is out of the Listed-placed Malicieuse, a Galileo half-sister to Arc hero Bago.

In Kentucky, meanwhile, the Niarchos family have also thrown their weight behind Karakontie at Gainesway Farm in Kentucky. The son of Bernstein is emerging as one of the most versatile stallions in North America, thanks to a clutch of early stakes winners that range from Princess Grace, a Graded stakes winner on both turf and dirt, to Del Mar Derby winner None Above The Law. Interestingly, Princess Grace is the product of a Silent Name mare, meaning that she is inbred to Sunday Silence. Indeed, she is the first stakes winner outside of Japan to carry his inbreeding.

Too much of a good thing?

Can there be too much of a good thing? In Sunday Silence, the Japanese racing scene has been dominated to such a degree—through both his sons and daughters—that outcrosses aren’t always easily available. And when such an animal does retire to stud in Japan, quite often their success is a reflection of their ability to cross effectively with Sunday Silence-line mares—the likes of Lord Kanaloa and Harbinger being notable examples.

In addition, successful inbreeding to Sunday Silence has taken time to gain momentum. However, in recent years, the tide has started to change.

Aside from Princess Grace, one recent major flag bearer has been the Japanese Fillies Triple Crown heroine Daring Tact. Efforia, who defeated Contrail in last year’s Gp 1 Tenno Sho (Autumn), is another fine advert among a group of 19 stakes winners from a pool of close to 4,000 named foals.

One of the greatest

Sunday Silence might be receding in pedigrees, but his influence has never been stronger. Many of the line remain easily distinguishable with their dark coat and rangy stature; for the most part, they are hardy runners with a physical and mental toughness to them.

“All these horses—they ran forever,” says Barbe. “They’re tough, train on and they’re sound. Whatever their level, they are consistent horses with a longevity to them.”

Granted, those descendants of Sunday Silence now coming through at stud in Japan aren’t always helped by having to compete with each other. But at the same time, the omens remain good, particularly in relation to Deep Impact’s own legacy as a sire of sires, which already includes the successful Shadai sires Kizuna and Real Impact. The latter became the first son of his sire to be represented by a Gp 1 winner when Lauda Sion won the 2020 NHK Mile Cup while Kizuna ends 2021 a top-four Japanese stallion, thanks to the exploits of the recent Gp 1 Queen Elizabeth II Cup winner Akai Ito and the Prix Foy hero Deep Bond.

Another young son, Silver State, is Japan’s second leading first-crop sire of 2021; only a minor four-time winner himself, he has already exceeded expectations by throwing the Gp 1-placed Water Navillera in his first crop.

The presence of Saxon Warrior and Study Of Man in Europe and other Gp 1 performers such as Satono Aladdin, Staphanos and Tosen Stardom in Australasia fuels the idea that this branch of the line is only going to become more powerful on a global scale. In short, international respect for the sireline is also at an all time high.

“Thanks to Sunday Silence, the Japanese racehorses earn respect from horsemen around the world today,” says Yoshida. “In return, breeders tend to find good broodmares to send to good stallions—Japanese breeders today buy a lot of good broodmares in the international markets.

“This enables Japanese breeding to keep developing. So you can imagine how strong Sunday’s impact is to our industry.”

Arkle - the legend, Himself

Racing commentator, Sir Peter O'Sullevan called him 'a freak of nature'. Fan mail to him was addressed, 'Himself, Ireland'.

In March 2014 it will be 50 years since Arkle won his first Cheltenham Gold Cup and this issue features excerpt from Anne Holland's new biography, which tells his story and of the people around the legendary steeplechaser who enabled him to produce his brilliant best.

Racing Against Arkle (From Chapter 8: ENGLAND v IRELAND, MILL HOUSE v ARKLE 1963-64)

Arkle had run six times in his first season, seven in his second and now, 1963-4, was to be the busiest of his career with eight. His reputation was red hot and the whole of Ireland was on fire about him. England was not. They had their own hero, Mill House, the ‘Big Horse’ who as a six-year-old had stormed to Cheltenham Gold Cup glory while Arkle was cruising to a mere novice win at the Festival.

The build up on both sides of the water that autumn was intense. Arkle had become what in today’s parlance is called a ‘Saturday’ horse. Television sets were still few and far between in Ireland and many fans, if they could not get to the track, would flock to whatever friends, relations or pubs had this large, new-fangled, somewhat ‘snowy’ black and white machine taking up a chunk of the sitting room.

At the time Michael Hourigan, now one of Ireland’s leading trainers was an apprentice jockey serving his time with Charlie Weld (father of Dermot) at Rosewell House on the Curragh. It was a strict life but a fair one and the lads found Mrs Gita Weld a perfect mother figure. When Arkle was running the lads were allowed into the house to watch him on the television.

‘I remember the crowds following him in, people were able to get a lot closer to the horses then,’ says Michael Hourigan.

Schoolboy Kevin Colman (now manager of Bellewstown and Laytown races) went to some lengths to reach a television.

‘I got the impression that Arkle ran every Saturday – he wasn’t wrapped in cotton wool. A family friend, Jim Kelly, ran the local athletics club and worked for the Greenshield stamp people including half day Saturdays. My sister Carmel and I were about twelve and fourteen and we used to go in to Dublin with him; his mother lived in Julianstown and on the way back we would watch Arkle on their black and white telly; television was a great novelty then.’

Arkle began his third season by running in a Flat race, against pukka Flat racehorses (unlike his two initial Bumpers which are specifically for NH horses in the making.) Although Arkle had gone through the previous season unbeaten (two hurdles and five chases) he was eligible for the one mile six furlong Donoughmore Maiden Plate because he was, indeed, a maiden on the Flat. There were thirteen runners for the weight for age contest; Arkle had to carry 9 stone 6lb along with three others and the lowest weight was 7 stone 13lb; Arkle was odds-on favourite.

It meant he would have to have a flat race jockey. One of the very best professionals was chosen in Tommy ‘TP’ Burns, who had not only been Champion jockey three times, but who had also grown up with Greenogue very much a part of his childhood.

Speaking in early 2013, just before his eighty-ninth birthday, TP recalled, ‘I spent a lot of my childhood at Tom Dreaper’s and rode a pony around the yard there. He taught me to drive a motor car and he was a friend. My father, Tommy, hunted with the Wards, and used to ride young horses from Tom when cattle were his number one business and the horses were his pleasure.

‘There were some good horses there and they were very carefully trained. They weren’t roughed up and half broken down before reaching maturity; he knew how to mind horses, and they would go on racing until they were twelve years old.’

THERE'S MORE TO READ ONLINE....

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN - EUROPEAN TRAINER - ISSUE 43

TO READ THIS ARTICLE IN FULL - CLICK HERE

Author: Anne Holland

The Hambletonians - the history behind the former racecourse and training centre.

If the turf at Hambleton had a voice, it would tell a long a colourful story of aristocracy riding up onto the hill and men coming down the drover's road from the north to race, of a royal trophy.

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN - EUROPEAN TRAINER - ISSUE 42