Polish horse racing gets a major boost

Article by Dr. Paull Khan

Night Tornado (11) and jockey Stefano Mura on their way to winning the Wielka Warszawska 2022, a race they won for the second year running at Sluzewiec Racecourse

Warsaw’s impressive Sluzewiec Racecourse

On Sunday, October 1st, Poland’s first ever internationally recognised Listed Race will be staged. The €100,000 Wielka Warszawska, for three-year-olds and upwards, is run over 2600m/13f of the impressive, 50-metre wide, turf track at Warsaw’s Sluzewiec Racecourse.

At its meeting in Ireland in February, the European Pattern Committee (EPC) confirmed its decision to award Black Type to the race, deeming it to have met the conditions of the recently introduced ‘flagship race’ scheme. Poland is the second country (after Spain) to benefit from this scheme, introduced last year, which gives EMHF member nations (which have no internationally recognised Group or Listed races) the opportunity to apply for a single ‘flagship race.’ This race is treated slightly more leniently than other races when being assessed for Black Type. Normally, the average internationally agreed rating of the first four finishers in the most recent three runnings of the race should be 100 or over. Under this scheme, a score of 95 in any two of the three most recent renewals is the threshold.

How did the Polish race meet the standard? It was undoubtedly given a boost in 2020, when the globe-trotting Czech-trained Nagano Gold (GB) – who had recently run second in both the Gp.2 Hardwicke Stakes at Royal Ascot and the Gp.1 Grand Prix de Saint Cloud – graced Poland’s premier track with his presence. Nagano Gold, then a six-year-old, prevailed by just a ½ length from a locally trained three-year-old named Night Tornado.

No one could tell at the time that Night Tornado would go on to be quite the star of the show, winning both the 2021 and 2022 editions, more recently with French- and German-trained raiders in his wake, including Nania (GER), who was fresh off a victory in a Hannover Listed Race.

Attaining Black Type is not only an honour for Polish racing but has wider implications, according to Jakub Kasprzak, racing secretary at the Polish Jockey Club and recently voted onto the nine-strong executive council of the EMHF – another example of Polish racing’s growing profile.

Jakub Kasprzak

Kasprzak reflected on the prospect in the run-up to the EPC’s decision: “If the Wielka Warszawska receives the Black Type status, it will undoubtedly be a great distinction and appreciation of Polish racing. The race has a long tradition, and several horses have appeared in the international arena. In addition, for the entire central and eastern European region, it will be a great opportunity to popularise racing.”

But Kasprzak is keeping his feet firmly on the ground: “Of course, we know that receiving such an award is really the beginning of the hard work, to show that it was not a ‘fluke.’ Personally, I am very happy, but I approach it with caution, being aware of the new challenges it poses for us.”

The journey that Polish racing has taken to get to this point is tumultuous. It has featured the need to rebuild from scratch on no fewer than three occasions and can only be understood in the context of the history of Poland overall.

Sluzewiec opening, 1939

The first organised races were run in Warsaw in 1841, on the Mokotow Field, now a large park just south of the city centre, which houses the Polish National Library. At the time, there was no ‘Poland.’ This was in the middle of a 123-year period during which Poland did not exist—having been partitioned in the late eighteenth century between Austria, Prussia and Russia. Warsaw fell into the Russian area and, since 1815, within a semi-autonomous state entitled Congress Poland. The Russian regime curtailed economic and public activity in the region, and racing in Warsaw was, for example, completely suspended between 1861 and 1863.

Originally a dirt track, four stands were erected along its finishing straight. In 1888, it moved to turf, at a time of fresh prosperity: pool betting had recently been introduced and was providing funds for prize money.

Sluzewiec, 1973

At this time, the horses were predominantly domestically bred, oriental horses, initially favoured by Polish breeders as they had historically provided Poland with success on the battlefield. However, the supremacy of the thoroughbred over racing distances (2km–5km) began to be recognised over time; and a thoroughbred breeding industry developed, drawing stallions and broodmares predominantly from England, France, Germany and Austria.

The stud of Count Ludwik Krasinski was pre-eminent in the four decades leading up to the first World War. Based in Krasne, (100kms to the north of Warsaw), it ranked top across the whole Russian Empire on 14 occasions. It produced the winners of five all-Russian derbies, in Moscow, including the famed Ruler.

Lwow Racecourse, 1943

This was an outward-looking period of international competition and success, with Polish-breds winning Classic races in Austria, Germany and Hungary. Two-year-old racing was introduced in the 1880s. (Initially, races were for four-year-olds and up only.) Trainers and riders were often brought in from abroad, and a breakthrough in riding styles occurred in 1901 when American jockey Cassius Sloan showcased the shorter-stirruped style to great effect and was soon mimicked by the domestic riders.

World War I put a stop to all this. In 1915, the racing stables were evacuated to the East. However, the racing spirit was not snuffed out and the president of the Horse Racing Society at the time, Fryderyk Jurjewicz, gathered most of the Polish stables at the track in Odessa (Ukraine) and organised races there throughout the rest of the war. Following which, in the Spring of 1919, about 250 thoroughbreds began their return home, arriving at the Warsaw track on June 28, laying the foundations for thoroughbred racing and breeding in a newly reborn independent Poland. In 1919, over 22 racing days, 193 races were run and a Western European-style racing programme, capped by traditional Classic races, was adopted.

There followed a spell of great growth and optimism. In 1924, the first volume of the Polish Stud Book was published. The following year, the Horse Racing Act was passed, establishing the Horse Racing Committee, with representation from a remarkably broad range of government departments: the Ministries of Agriculture, Military Affairs, Interior Affairs and Treasury all had seats, alongside representatives of the racecourses and breeders.

Lwow Racecourse, 1943

Breeding stock was imported in significant numbers – over 1,000 broodmares from the disintegrated Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as from England, France, Russia and Germany. By 1930, the number of mares bred – often a useful barometer for the health and scale of the sector as a whole – had climbed back up above pre-war levels.

Many racing societies and racetracks emerged in the 1920s at places like Lublin, Lodz and Katowice. From 1933, racing was staged over the winter at the southern town of Zakopane. These regional tracks not only played an important role in the development of the thoroughbred sector, they also enriched the society by providing focal points for social life. Sadly, for most, their time in the sun was short-lived, as Poland was hit especially hard by the Great Depression of the 1930s, leading to their closure.

Even during these straitened times, a grand project was undertaken to construct a modern track on land from the Sluzewiec farm, which had been purchased by the Society for the Encouragement of Horse Breeding. With the help of international experts and renowned landscape architects, the racecourse – which is present-day Poland’s most important track and host to the Wielka Warszawska – was opened on June 3, 1939.

The Second World War caused a complete dispersion of breeding stock. For the third time in a century, thoroughbred breeding had to be started from afresh, and this time, under the constraints of Communism. Private breeding was banned and state studs were established in the place of the liquidated private studs. Slowly, activity increased from the 45 thoroughbred mares registered in 1944. A draft of 230 thoroughbreds reclaimed from Germany provided a timely fillip. By 1950, the mares’ roster had risen to 150, and this figure grew by an average of 10 per year for the next four decades.

Then, in 1989, came the seismic political changes in which Poland played such a pivotal part and saw the overturning of communism. Several state studs were closed down, and private stud farms re-appeared in their place. Individuals could now own and lease racehorses, and racing stables began competing on the principles of the free market. Broodmare numbers shot up to 900 – returning at last to the pre-WWII levels.

The story of Polish racing is, indeed, one of immense resilience. It is a vivid example of how societies – in so many parts of the world, after conflict or disaster – hasten at the earliest opportunity to re-establish horse racing, emblematic as our sport can be of normalcy resumed.

Runners pass the stands at the Baltic Sea resort track of Sopot.

What, then, of Polish racing in the 21st century? The exploits of two horses might be highlighted: those of Galileo (POL) and Va Bank (IRE) – both of whom made waves in Western Europe: the first in the jump racing sphere, the second on the flat.

Let us consider the ‘Polish Galileo’ first. Poland’s Ministry of Agriculture continued to own stallions for some years after 1989 (an example of state involvement that was only eventually ended when, in 2004, Poland entered the EU) and one of the last such was Jape (USA), whose second crop included Galileo, who had won the Polish St Leger, had placed second in the Polish Derby and had been voted Horse of the Year. Galileo was put up for sale at the Sluzewiec Sale in Autumn 2001 and was purchased by British trainer Tom George to go hurdling. Winning on his British hurdling debut in February 2002, George went directly the following month to the Cheltenham Festival, where Galileo was famously victorious in the 27-runner Gr.1 Royal and SunAlliance (now Ballymore) Novices Hurdle.

Polish superstar Va Bank

Va Bank’s remarkable career began with a 12-race unbeaten sequence, which included the Wielka Warszawska, Polish Derby and a German Gp.3. Later, while in training in Germany, he added a further German Gp.3 and Italy’s Premio Roma (Gp.2) to his tally. He now stands as a leading sire in Poland.

Today, Poland has three active racecourses, all turf, of which Sluzewiec is the youngest. Partynice in Wroclav, not far from the Czech and German borders, was founded in 1907 and is dual-purpose, hosting all the country’s 36 jump races. The Baltic Sea track of Sopot is the daddy of the trio, dating back to 1898.

Sixty trainers are licenced in Poland, with a quarter of these confined to training their own horses – just over half train from their own premises; the rest occupy stables at either Warsaw or Wroclav. Training fees average around €6,500pa, excluding veterinary and transport costs. The champion thoroughbred trainer last year, Adam Wyrzyk, notched up 36 wins.

Average prize money on the flat is around €4,600; over jumps, it approaches €7,000. Field sizes are knocking on the door of the ‘magic 8,’ with the flat averaging 7.9 and the jumps 7.1.

All of Poland’s jump races are open to foreign competition, including the Crystal Cup (€37,000) and Wielka Wroclawska (€43,000). On the flat, of the 278 races, the top 35, including all five Classics, and a few lower-class races, are open. Last year, 82 foreign-trained runners were attracted to race in Poland, from Slovakia, Czech Republic, France, Sweden and Germany.

Recent years have seen a growing reliance upon foreign-bred horses, which now represent the slight majority of horses-in-training. Of the 386 imports, 164 were from Ireland, 128 from France and 43 from Britain. Six years earlier, the picture was very different, when over 70% of horses-in-training were home-bred – a cause of some concern in Poland.

Tight finish in front of packed stands at Wroclaw

Despite a new television racing channel and internet betting platform, on-track betting is still the predominant channel for horse racing bets. Turnover is buoyant, but the returns to racing from betting turnover are modest.

The Polish Jockey Club, established in 2001, sits beneath the Ministry of Agriculture. Polish racing is heavily dependent upon government support, with 90%–95% of prize money emanating from that source. It is a relationship that is not without its frustrations:

“If we need to change something, like a rule of racing,” explains Kasprzak, “we are unable to do so without specific governmental approval; and we, as just one among many organisations, often find we are waiting and waiting for this approval to come through.”

What does Kasprzak consider to be Polish racing’s prime challenges and opportunities?

“The first challenge is the support of Polish-bred horses, to rebuild our breed. At this moment, we have a few stallions with good pedigrees and race records. Their first offspring will race this year.

2022 Polish champion thoroughbred trainer Adam Wyrzyk and daughter Joanna, who became the first woman to win the Polish Derby when winning in 2021 on Guitar Man

“Second, we need new racing rules. Third, we have problems in sourcing stewards. People don’t want to be stewards; it is a very hard and responsible job.”

“As regards opportunities, these days, there are many possibilities when it comes to spending free time, but in Poland, our three racecourses offer something special. You can meet friends, eat and drink as well as watch horses compete in the flesh. We have the chance to sell to a new audience this unique way of having a good time.”

This year, Poland is taking centre stage within European racing in another respect. It will, for the first time, host the EMHF’s General Assembly over two days in May. Immediately following this, the inaugural EuroMed Stewards’ Conference will take place at the same Warsaw venue.

And then, thoughts will turn to the Wielka Warszawska, whose shiny new Black Type status has been rewarded with a hefty boost in prize money – the winner taking home €58,000 (up from €38,000 last year). So, trainers seeking a realistic shot at Black Type (remember, statistically, the race has been easier to win than any other European Listed Race) and a nice prize money pot with a 2400m+ horse rated around the 95 mark, consider a trip to Warsaw this October.

Prep school - the role of the pre-trainer in the flat racing world

Article by Daragh Ó Conchúir

WC Equine’s Ellie Whitaker & Tegan Clark

Having had a little poke around the inner workings of pre-training in jumps racing for the last edition, it is now time to do the same in the Flat world.

In both National Hunt and Flat, owners and trainers send horses to be broken and prepped specifically to race, enabling trainers to get on with the job of attending to those in their yard that are ready to run.

Then there is the trading side. In jumps racing, that revolves around the point-to-point scene, where proving a level of ability in competition increases value. In the Flat division, the breeze-up sales are not competitive, but they illustrate athleticism, temperament, physical prowess and of course, raw speed.

While very successful, pre-trainers aren’t universally popular. As mentioned in the pre-training jumpers article, retired trainer and former CEO of the Irish Racehorse Trainers’ Association Michael Grassick argued that they were making an already difficult staffing situation for trainers even worse.

Last February, recently retired trainer Chris Wall asserted in a Racing Post feature that the proliferation of pre-trainers was accelerating the growth of the so-called super trainer, enabling them to stockpile horses.

But then, in the same article, Ben de Haan described the demand for pre-training as a very welcome opportunity to improve revenue streams.

Obviously, Flat racing is a more global field than jumps, so we had to be a little less parochial in sourcing our contributors; we touched base with successful operators in England, France and Ireland, namely Nicolas Martineau, Ellie Whitaker, Tegan Clark, Willie Browne and Ian McCarthy.

Willie Browne

Browne is featured elsewhere in this publication for his training prowess, but it is his nonpareil acumen in sourcing future champions as young stock and then producing them through the breeze-ups that he can hang his hat on. It’s also a lot better way to pay the ever-escalating bills.

Now approaching his 77th birthday, he has more than 40 years’ experience in this sector, having consigned a draft at the very first breeze-up sale in 1978. And though he has moved from the original Mocklershill location outside Fethard, Co Tipperary, to build Grangebarry Stables just over the road, he has retained the home label as a brand for excellence.

It was Browne who sold the first breeze-up graduate to win a Classic, when Speciosa galloped to victory in the 1000 Guineas in 2006, little over a year after breezing at Doncaster. Walk In The Park and Trip To Paris are others to go through his hands while Mill Reef Stakes victor Sakheer has the 2000 Guineas in his sights in the coming months.

Zoffany colt Sakheer

He has broken the million-pound barrier twice at the sales and was one of the first to explore the American market for value when buying horses to breeze—Sakheer, a most recent example having been acquired as a yearling at Keeneland for $65,000 in September 2021 and then making €550,000 at Arqana, eight months later. A year and two days after he was picked up in his native land, the Zoffany colt was a three-and-a-half-length winner of the Mill Reef.

Browne also has a lengthy list of clients who send horses his way to break and pre-train, including Coolmore, the Niarchos family and Canadian owner Chuck Fipke. He trained Spirit Gal to bag a listed prize for Fipke last season before she was moved on to continue her career with André Fabre.

“When we are at it as long as we are, and we know our gallops, it’s fairly smooth,” says Browne. “Basically, we train horses here to run fast for two and a half furlongs, maybe three furlongs. That is what they are gauging you on.

“If you are training and you get to your three-furlong pole, and when you go to the next furlong, then you know if you have a racehorse or not. Because if horses are going very fast for two and a half or three, they’ll invariably slow down. But Spirit Gal wouldn’t slow down. That’s our yardstick, if we think we have something good.

“In pre-training, you wouldn’t have to put in the miles that you’d put in with the horses that are breezing—less time on their backs, you know? I have two horses going away tomorrow—one to John Gosden and one to Ralph Beckett—and we would never have put a gun to their head. I wouldn’t want anybody to think we gun the daylights out of these breeze-up horses, but you have a better idea.

“The horses for trainers, the half-speed is as far as they’d have ever gone, unless they gave them to you until July or August. They’d usually go between March and May. The pre-training is great … it keeps the whole business ticking along.”

Le Mans is noted for horsepower of a different kind, but Nicolas Martineau and his wife Pauline Bottin have a premises just 20 minutes from the venue for the world-famous 24-hour rally that in five years, has established a reputation for producing speed on four legs, rather than wheels.

Among their clients are the Devin family, Louisa Carberry, Tim Donworth and Alessandro Botti. Last year’s Gp. 1 Prix Royal-Oak winner Iresine was one of the earliest graduates from the Martineau school while of the younger crop, Good Guess was placed in a listed race as a two-year-old last term. Starlet du Mesnil and Enfant Roi are some of the graded jumpers he has prepped, while British and Irish followers will know the high-class Fil Dor well.

“At the stable I work with a lot of trainers,” Martineau . And with each horse, we work like the trainer works. We don’t work a horse for Francois Nicolle like we do for Gabriel Leenders. We do specific work, horse by horse.

“The big problem in France is staff, personnel for racing stables. So the trainer, when they call me, they want me to prep the horse to be ready to go racing in four or five weeks, six weeks maximum, just after they leave me. You are doing all the pre-training but up to the stage too where they are ready to go racing.”

That is clearly a dissimilar approach to what is required by most British and Irish trainers, but one aspect of it that is very similar is the staffing shortage, which Browne attributes to his numbers being down to around 50 this year.

Back in France, Martineau even has different feed for the breeze-up two-year-olds and those in pre-training because they are not being trained for the same jobs; and his time learning about both sides of the equation has informed his methods.

“I have my experience from Ireland. I worked for Mick Murphy at Longways Stables. For me, he is the best for the breeze-ups, and I learned so much. He’s exceptional, and I took a lot from working with him.

“I worked for a long time for Jean-Claude Rouget. I worked for a year as well with my wife Pauline for Willie Mullins, and she worked as well for Joseph O’Brien. That was very good experience for pre-training.”

Indeed, the woodchip gallop is a mid-way point between what Mullins and O’Brien have at Closutton and Carriganóg respectively, so that they can cater for all types of horses.

McCarthy is a former NH jockey who had already built his breaking, pre-training and breeze-up operation, Grangecoor Farm on a greenfield site in Kildangan, Co Kildare by the time he had retired in July 2021.

The 34-year-old, who expects to have between six and eight juveniles bound for the Craven, Guineas and Goresbridge Breeze-Ups (while also breaking and pre training Flat and NH youngsters for the racetrack directly and producing jumps horses through the point-to-point sector), places a heavy emphasis on detail and that means not taking any shortcuts, even with spiralling costs.

“I spent ten years with Dessie Hughes and he was a horseman in himself,” McCarthy explains. “I was always interested in the breaking side of it with the stores during the summer, so it was always something that was in my mind from then that I might do.

“I went from there to Ted Walsh, where I learned an awful lot that stood to me when I started breaking and pre-training.

“I put it out there that I was doing it and was lucky enough to have ridden for some good owners that supported me when I was starting out and good trainers when I was freelancing that supported me as well.

“We have about 50–55 horses here, which is a number that works very well. I am so lucky, given how difficult it is for everyone to get staff in that I have five excellent full-time people here. Niall Kelly is head man, and Alan Davison, Johnny Wixted, Sean Donovan, Christine Worrell and Orla McKenna are with me as well. They are vital. We also have eight part-time workers.”

In his experience, there are varying techniques for getting to the same end game of a horse being prepared to give its best on race day. What is sure is that you cannot bring the same approach to every model.

“You try and get to know the horse the best you can. You’ve different types of horses—horses coming from the sale and homebred horses coming from the farm. The sales horses will have a sales prep done and will have that under their belt. Horses coming in off the farm just won’t be as advanced, so they’ll take a little more TLC.

“Here, the yearlings are started off in the lunge ring and are driven for a couple of weeks. They then go on the furlong sand-and-fibre gallop. Then, just before Christmas, they’re put on the three-furlong round sand-and-fibre gallop.

“From day one they’re driven through the stalls so that they adapt to it really well.

“I do like to get the two-year-olds away at the end of January, start of February. We use The Curragh on a regular basis for a day away. It’s an important part of it.”

Two of the best illustrations of Grangecoor’s work arrived in 2021, starting when he had Hierarchy for the Tattersalls’ Guineas Sale. The son of Mehmas breezed the second-fastest time and was sold to David Redvers for 105,000 guineas, going on in the following months to win twice and be placed twice at group level, before only being beaten a length and a quarter in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint.

Hierarchy – Tattersalls Guineas Breeze Up Sale 2021

The same year, he was sent a Profitable filly that had been purchased privately by Liam Donovan on behalf of the Dunphy family. The pocket rocket turned out to be Quick Suzy, who would shed her maiden status at Curragh Racecourse before blitzing the opposition in the Gp. 2 Queen Mary Stakes at Royal Ascot.

“You get a great thrill and satisfaction from something like that. I’d say it’s more satisfying than when riding a winner because you’re putting an awful lot more time into them, and you actually get attached to them and love to see them do well.”

Ellie Whitaker (26) and Tegan Clark (33)

Ellie Whitaker (26) and Tegan Clark (33) set up WC Equine in September 2020, as the world was in Covid lockdown. It wasn’t ideal, but with Robert Cowell looking to let out a yard at Bottisham Heath Stud in Six Mile Bottom, just outside Newmarket, they took the plunge.

What has been so vital for them, given the difficulties in finding enough good staff, is that they are both hands-on, able to muck out and ride, with 35 boxes full. Between the two of them, they broke 64 horses in a five-month period.

Having Newmarket facilities was a considerable help in getting established quickly but so was the initial support of trainers Kevin Philippart de Foy and Roger Varian. They sent yearlings to break and pre-train, while Brendan Morrin of Pier House Stud utilised their services to prep some more for the breeze-ups.

Tegan Clark

Whitaker was working for Cowell at the time, having started out with Mark Dwyer, the former Gold Cup-winning pilot who is a wizard of the breeze-up realm and indeed, has enjoyed extensive success in tandem with Browne. She also worked for Charlie Appleby and among the horses she broke in was triple Gp. 1 winner and champion two-year-old, Pinatubo.

Meanwhile, Clark had worked for Varian. That early support allowed them to showcase their talents, with James Fanshaw and Sean Woods among new clients this year.

“Last year was the first year we managed to get a good client specifically for the breeze-ups,” Clark explains further. “We also bought a few ourselves and have shares here and there, but this is the first year people have rung us and put horses with us to specifically breeze; and we want to try and build on that this year to take those relationships and partnerships into the future.”

This was on the back of two notable successes at the Guineas Sale. In 2021, Royal Aclaim won a maiden within a month of being consigned by WC Equine for Pier House. She won twice more at three and though losing her unbeaten status in the Gp.1 Nunthorpe when favourite, she ran creditably in sixth and was placed subsequently at group level.

Having Newmarket facilities was a considerable help in getting WC Equine established quickly.

Twelve months later, Village Voice was sold. Not the same type of model, she holds an entry in the Irish Oaks for Jessica Harrington, after having just two runs in October, winning her maiden and finishing third in a Gp.3.

“You’ve got to be honest and educate the horses as well as you can so that they do have a lasting career within the sport. It’s brilliant to have a mature two-year-old that’s breezed, but then that’s going to go on and probably have a lovely three-year-old, if not four-year-old career with Jessie Harrington. She already has her black type. So as long as you keep producing that sort of quality, people take notice.”

Initially, all the yearlings go through the same routine, though never together.

“The breezers go through the same process as the pre-trainers from breaking until Christmas time. We give them all a break then; but when the breezers come back in, they have to start knuckling down. You can’t expect a pre-trainer to lay up with them because we are putting the breezers under pressure a lot earlier.”

“There’s a fine line,” notes Whitaker in relation to horses being pre-trained for owners and trainers. “We’re not here to physically break horses or to see how good they are. Our job is to get them through the breaking process and get them up to a path in the training process where they can go up to town (Newmarket) and go up Warren Hill with ease—get them to a business level.

“Every trainer is different, their standards are different and it’s about meeting their standards and what they require. At the end of the day, it’s a product we’re selling and that product needs to appeal to each individual. We’re equipping these young horses with the right tools; and if they can go into a training facility with the right sort of attitude—be calm and confident, we know we’ve done our job well then.”

In terms of the breeze-ups, with Browne owning most of those horses himself or in partnership with others, sourcing is key. He dabbles in buying foals with long-time ally Dwyer, but the majority are yearlings.

“The trouble with nice horses is they might not be racehorses. When we are looking now, we are looking for a completely different type of animal than that we used to look at 10 to 15 years ago. You’d buy a nice-looking horse, with a nice pedigree and if he breezes up with a nice action but maybe not going that quick, he’s compared against nothing else; and if they like what they see and if they like the movement and the horse’s page, and he’s good looking, you are going to get him well done.

McCarthy learned from the likes of Dessie Hughes and Ted Walsh that stood him in good stead when he started breaking and pre-training

“Now I’ve a horse out there that I gave three hundred grand for, and he’s going to the sale in France. He’s by a sexy American sire Into Mischief, he’s training very well and we hope we’ve struck gold; but If he doesn’t breeze well, no matter how well he’s bred or how nice he is, you’ll get badly hurt.”

Nice horses are pricier than ever before, so Browne will prioritise the page and walk if he must. McCarthy suggests that at his price range, “you have to be lenient towards the page... I’ll focus on the individual.”

And while the breezers are pressed far more than pre-trainers because of the more immediate job they must do, McCarthy argues that you can’t make them faster than they are.

“You’re just trying to get the nice individual with the suitable and affordable pedigree, and then to keep them sound and watch their minds, as they are only two-year-olds and still developing.”

“We would be riding horses ten days after they came in,” Browne details his system for the breezers. “When you’ve big numbers, it is a matter of getting them done, but I wouldn’t say a word to somebody who is five or six weeks breaking a horse. There is nothing wrong with that; it’s good practice.”

Everyone agrees that good communication is crucial, be that in terms of honesty about the calibre of animal you are selling or being able to pass on as much information as possible to whoever is taking on a horse you have pre-trained.

In France, once again, it goes a little further.

“Sometimes clients will say, ‘I would like to go to this trainer with this horse’; but I might say, ‘I’m not sure, for this horse, it might be better to go to this one,’” Martineau reveals. “When you know the horses, you know what trainers might be suitable, and that gives the client confidence.”

Apart from staffing, increased costs is a huge challenge. Browne changes the wood chip on his gallop twice a year, and says it is 50 percent more expensive than before.

Martineau points out that the expenses are like those of a licenced trainer but that pre-trainers in France charge around €30–32 a day, while full trainers will get in the region of €70. Still though, he likes having a little more time and a little less pressure. The trade-off is worth it, particularly as the business has been built up now and is making money.

McCarthy offers a pragmatic tone abouts the price of everything rising. It eats into the bottom line, but it cannot lead to a reduction in the calibre of his service, given how appreciative he is of the loyalty shown to him by his various clients.

“The big thing for me is attention to detail,” McCarthy emphasises. “That is of the utmost importance through the entire process, and that starts with feed and every step of the way after that.

“Everything is more expensive now, but I look at it that you put in the best of what you need. You can’t cut corners. What you’re doing is educating young horses, and that’s how we see ourselves—as educators of young horses before they join the big boys and go into the next stage of their lives. You need to do everything right, no matter what it costs.”

It is interesting, given Wall’s criticism in particular, that McCarthy will have horses all year around, but that is imperative according to the Galway native, as you have to tailor your approach to the systems horses will be entering.

“For the different trainers we work for, we know their regimes and try to have the horse prepared for them to fit into their regime when they think they’re up to it. The ideal is for them to go in February, but it doesn’t always work like that as all horses are different.

“All the big trainers are going up in numbers. Early into the year and early into the Flat season, we’d be dealing with a lot of the backward two-year-olds and trying to organise them for trainers, giving an opinion of what’s early and of what wants a little more time. And the ones that want a little more time, we’ll be holding onto them and letting them progress and grow into themselves.

“Plenty of trainers would have a couple with me that are not going to be early two-year-olds. They’ll be built up and they’ll be rode in bungees to try [to] strengthen them up and put a top line on them. It’s basically strength and conditioning we’re doing with them.”

Browne states that even the horses he has pre-trained that are being sent to England will most likely go to another pre-trainer, due partly to offset fears of any bug being transmitted, but also because they are full.

“Chris Wall wouldn’t be mad about what we do, but I would go along with what he said about it helping the big trainers stock up,” Browne remarks. “You are taking away half a year’s livelihood from him by doing what you are doing.”

“Unfortunately, trainers don’t have the staff,” observes Clark. “We’ve got the room, we’ve got the availability, we’ve got the staff.

“We’ve got trainers in the hustle and bustle of Newmarket who send horses to us 10 minutes down the road. They might only use us for 10 or 14 days in the summer on grass, keep them ticking over; and then they go back in and are running straight off of that and are happy with the results. The horses are running well.”

And that’s the point. Be it breaking, pre-training, a little R&R, prepping for breeze-ups—the results speak for themselves.

“It’s about being calm and straight,” concludes Martineau. “The voice is always calm. I want my horses very calm and straight on the gallop. If that happens, they can go to the races anywhere and whenever you want.

“They are ready.”

"The Captain" - Cecil Boyd-Rochfort

Article by Jennifer Kelly

Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort

In the hours leading up to her coronation, Elizabeth sat deep in thought, quiet with contemplation. A lady-in-waiting saw the new Queen’s preoccupied countenance and asked her if all was well.

"Oh, yes,” Her Majesty replied, “the captain has just rung up to say that Aureole went really well."

On the precipice of great responsibility, the new monarch’s mind was not only on the serious matters of state, but on the Derby candidate she hoped would carry her colors to victory in a matter of days.

The man entrusted with Aureole’s preparation, the Irishman whose skills had inspired the confidence of a sovereign and the daughter that succeeded him, was Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort. The youngest son of a family known for its service to the Empire and a fondness for sport, Boyd-Rochfort spent his life with horses, a calling that took him from the countryside of County Westmeath, Ireland to the gallops of Newmarket and inspired the confidence of royalty from both sides of the Atlantic.

Aureole, and jockey Harry Carr before the 1953 Epsom Derby, where he eventually finished second, four lengths behind winner Pinza.

A life in sport

When Cecil Charles Boyd-Rochfort greeted the world on April 16, 1887, he was the last of Hamilton and Florence Boyd-Rochfort’s sons, joining brothers Arthur and Harold. His father had been a major in the 15th Hussars and had served as high sheriff of County Westmeath, Ireland, where the family made their home at Middleton.

There, the Boyd-Rochfort family hunted. They rode. They farmed. After his father’s early death, his mother bred horses and raised cattle, sheep, and pigs and even had a racing stable. Cecil carried this love of horses into his education at Eton, where he was an indifferent student, focused more on pedigrees and racing than his studies.

He attended the races along with his coterie of friends who were also keen for the sport. When Cecil left Eton in 1903, his next step was uncertain. His brother Harold encouraged his younger brother to follow him into military service, but Boyd-Rochfort was unwilling to commit, still awaiting his chance to work in racing. That came in 1906, when one of his heroes came knocking with an offer too irresistible to refuse.

Lessons from the best

Like Boyd-Rochfort, Henry Seymour ‘Atty’ Persse heard the siren’s call of the racetrack and followed it to a career as both a rider and a trainer. He finished third in the 1906 Grand National and soon after switched to training at his Park Gate stables near the village of Grately. In need of an assistant, Persse offered the job to the aspiring horseman.

The Irishman had long been a hero of Boyd-Rochfort’s, since the young man had seen Persse win the Conyngham Cup in 1897. Boyd-Rochfort’s tenure with Persse, though, was short, as the latter became the private trainer for Colonel William Hall Walker, the future Lord Wavertree, in 1908. He soon found a position with Colonel Robert Dewhurst’s Bedford Lodge in Newmarket. The young man so impressed his new boss with his knowledge of racing and breeding that Dewhurst allowed him to help with the business of running the stable and sent him with the horses running out of the Newmarket area.

When Sir Ernest Cassel sought a new racing manager, Boyd-Rochfort was suggested for the task. Alongside trainer William Halsey, he bought yearlings, learned more about keeping horses sound, and watched preparations for tries at the English classics. In 1912, Boyd-Rochfort bought a yearling by leading sire Desmond for 3200 guineas. The colt, later named Hapsburg, proved to be worth the price: he finished second in the 1914 Derby and then won the Eclipse and Champion Stakes. He later became a good sire, a testament to the young man’s eye for bloodstock. Boyd-Rochfort would not have long to enjoy his success as World War I prompted him to join the Scots Guard. Cassel promised that his job as racing manager would be there when he returned.

A good start

After the war, where his experience at the Somme had earned him the Croix de Guerre and a promotion, he returned to England as Captain Boyd-Rochfort, a title he would go by for the rest of his life. Back in Newmarket, he found Cassel’s racing stable in a sad state. Sir Ernest himself was in poor health and the stable reflected the same; they had only one win in 1917 and then none in 1918. After William Halsey retired, the captain found a new trainer for the ailing stable, but their fortunes did not improve.

However, the captain’s did. He connected with the American horseman and businessman Marshall Field III, heir to the Marshall Field department store fortune. Field was looking for a trainer for his English stable and Boyd-Rochfort volunteered for the job provided Cassel was open to it. Sir Ernest was cutting back his racing interests and gave the captain permission to work for Field as well.

One of the first horses the captain bought for Field was a filly named Golden Corn. At two, she won the Champagne and the Middle Park Stakes, a rare double achieved by greats like Pretty Polly, the Filly Triple Crown winner of 1904. Field and the captain had struck gold with one of the first horses he picked out for his new owner. Though Golden Corn showed her best at age two, her success promised much for the captain and his association with the American owner.

As Golden Corn was winning, the captain‘s grand year turned sad with the passing of Sir Ernest Cassel. He left the captain a year’s wages in his will, but it was not enough for a new yard for the fledgling trainer. Both his mother and Field lent the needed funds for the purchase of Freemason Lodge in Newmarket. With fifty stalls to fill, the captain took out his trainer’s license in 1923 and got to work.

On his own

That first year, Boyd-Rochfort trained for several owners, including his brother Arthur and Field. He won nineteen races, one of those a victory with Golden Corn in the July Cup at Newmarket. In 1924, he scored his first win in the Irish Oaks, the Irish equivalent of the Oaks at Epsom, with Amethystine.

Through his connection with Marshall Field III, Boyd-Rochfort soon had horses from more American owners, including William Woodward, a banker and chairman of the American Jockey Club, with whom the captain would win races like the Ascot Gold Cup and the St. Leger. In addition to Woodward and Field, his list of American owners counted some of the sport’s biggest names, like Joseph Widener, John Hay Whitney, cosmetics magnate Elizabeth Arden, and diplomat and businessman Harry Guggenheim.

1955 Fillies Triple Crown winner Meld.

Boyd-Rochfort soon picked up another important owner, Lady Zia Wernher. The daughter of the Countess Torby, a granddaughter of Alexander Pushkin, and Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovich, a grandson of Tsar Nicholas I, Lady Zia invested heavily in racing after her marriage to Sir Harold Wernher. For Lady Zia, the captain won the Ascot Gold Cup with Precipitation; the Coronation Cup with Persian Gulf; and the One-Thousand Guineas, the Oaks, and the St. Leger, the Filly Triple Crown, with Meld.

Boyd-Rochfort’s old friend Sir Humphrey de Trafford was another of his earliest owners and one that would stay with him the whole of his career. The captain trained Alcide, who won the 1958 St. Leger, and Parthia, who gave both men their only Derby victory in 1959. In addition to training for his old friend, Boyd-Rochfort made Sir Humphrey best man at his 1944 wedding to Rohays Cecil, the widow of Lieutenant Henry Cecil and mother of four sons, including Henry, who would follow in his stepfather’s footsteps.

To attract owners like Wernher and de Trafford and that cadre of Americans spoke to the skills and expertise that the captain offered, developed through tangibles like hard work and discipline and intangibles born of a life spent with horses.

The man behind it all

His prodigious success had its roots in a confluence of factors. He was brought up in a family with a lifelong interest in horses and racing. He was mentored by two former riders turned trainers who shared the benefits of their time in the saddle and their knowledge acquired while developing horses. The captain was keen to learn from others, from his earliest years at school studying racing and pedigree between lessons to those years with Persse, Dewhurst, and Cassel, where he took in the lessons of healing ailments, feeding the bodies and minds of the horses in his care, and any other topic related to racing and breeding Thoroughbreds. He was a patient trainer, focused on the horse as an individual and less on the expectations that might put his charge in the wrong race at the wrong time.

He was keen to hire the best and set them to the tasks needed to run the yard, but he also had his hands on the horses in his care. He trusted his employees to keep the rigorous schedule he set each day. He felt the legs of his charges, mandated soft water and weighed and measured specific feeding plans for each horse, and believed in long walks for his horses to warm them up for their exercise. He broke in horses at the Lodge in the early days and then later leased Heath Lodge Stud for that purpose. Trainer Sir Mark Prescott, who was a young assistant to Jack Waugh in the late 1960s, remembered that the captain’s horses “used to run in a sheepskin noseband, the lot of them and they always looked marvelous, something maybe a bit above themselves.”

At a given time, as his son Arthur remembers, he would have upwards of 65-70 horses and a stable of around twenty-five staff, from a farrier to a collection of exercise riders and jockeys, that were, as Sir Mark put it, well-mannered “like little gentlemen.” At 6’5”, the captain towered over most of his staff, and was, as his secretary Anne Scriven recalled, “a very stately Irish gentleman. Very upright, very Edwardian.”

“He would say, ‘You boy do that,’ even to [assistant trainer] Bruce Hobbs,” she shared. After winning the Grand National on Battleship, the youngest jockey to do so, Hobbs spent a decade and a half as Boyd-Rochfort’s assistant.

Arthur remembered his father as “being a Victorian and very upright. They were brought up in a different era then they were very strict in the yard, and everything was immaculate.”

“The captain was old school, aristocratic, he was completely confident in his superiority to most people,” Sir Mark remembered. “But he was always nice, very polite.”

As a trainer, he was an observation horseman and a stickler for detail and demanded the same of his employees. He eschewed gossiping on the Heath as some trainers were wont to do, preferring to watch his charges intently. The captain no doubt stood at attention watching one horse in particular for owner William Woodward, a long and lanky chestnut with a wide white blaze, a champion in America who was trusted to this singular conditioner for a tall task: winning the Ascot Gold Cup.

A challenge for the captain

Americans know Omaha as the third name on the short list of horses to have won the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes, and the Belmont Stakes, the American Triple Crown. Owner William Woodward’s aspirations were not limited to winning classic races in his own country, but also in England, the place where he cultivated his grand ambitions as a young man working for the American Ambassador Joseph Choate in the earliest years of the 20th century. One of the classics he aspired to was the 2½-mile Ascot Gold Cup.

Omaha with jockey pat beasley and groom bart sweeney

Omaha’s three-year-old season had been cut short by injury, and, with his sire Triple Crown winner Gallant Fox already representing Woodward’s Belair at stud, the American did not need to retire his second Triple Crown winner. Instead, he took the risk of sending Omaha via the Aquitania to England, his ultimate destination Freemason Lodge. The Triple Crown winner was not the first Woodward had sent to the captain, but the task ahead of the trusted horseman could be considered somewhat of a titanic one: take a horse primarily trained on dirt, who had only raced counterclockwise and never more than 1½ miles and prepare him to run a mile longer clockwise on grass.

The captain would send the American horse on longer gallops, from a mile and a quarter to two miles at least once a week, building the colt’s stamina and giving him the chance to stretch out the long stride that had made him such a success at distances over a mile. Couple those regular gallops under Pat Beasley, the stable’s lead jockey, with the captain’s regimen of walking, water, and feed, and Omaha was quickly fit enough to easily win his first start in England, the 1½-mile Victor Wild Stakes at Kempton Park. Three weeks later, back at Kempton Park, he took the two-mile Queen’s Plate with ease. Clearly, the captain’s plan to acclimate and prepare the American horse for the Ascot Gold Cup was working.

In the Gold Cup itself, nearly three weeks later, the 2½ miles came down to the last two furlongs, as Omaha and the filly Quashed, herself an accomplished stayer, battled down the stretch. Anytime one pulled ahead, the other fought back, neither giving way until the very end. In what would be a photo finish today, the ultimate decision came down to judge Malcolm Hancock. The difference between the winning Quashed and the captain’s charge Omaha was a simple nose. That Omaha was able to come so far in such a short amount of time was testament to not only the well-bred champion but also Cecil Boyd-Rochfort, a horseman whose true brilliance came through in how he was able to sense and cultivate a horse’s potential.

It was this instinct about the individual horse, the care he put into their development, and the discipline he imbued into his staff and himself that brought him an opportunity afforded to few: a chance to train for the Royal Stable. First for King George VI and then for Queen Elizabeth II, he brought his beloved monarchs great victories, ones befitting a man who had made horses his life's work.

A royal opportunity

When Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort took over the Royal Stable, he had already been leading trainer in 1937 and won his share of both English and Irish stakes. As he went to work for the Royal Family, whom he greatly admired according to son Arthur, he was able to continue working with Lady Zia and Sir Humphrey as well as his American owners. With the Royal Stable, though, came some of his signature wins.

For the King, he won the Coronation Stakes at Royal Ascot with Avila, the One Thousand Guineas and the Dewhurst with Hypericum, and the Cesarewitch with Above Board. Days after Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, the captain started Aureole in the Derby, seeking a Classic victory for the lifelong horsewoman. Aureole mounted a bid in the stretch but could not catch Pinza. Aureole would go on to win the King George and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Royal Ascot the following year, giving the Queen her first victory on the Ascot Heath.

Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort and Queen Elizabeth II in the paddock at Kempton Park as she watched her colt Agreement being unsaddled after his victory in the Coventry Three Year Old Stakes.

Though the Derby would elude them, the captain would bring the Queen a Classic win in the Two-Thousand Guineas with Pall Mall. In all, he conditioned fifty-seven winners for the King, one hundred and thirty-six for Queen Elizabeth II, and three for the Queen Mother. As he approached his eighty-first year and the end of his time as a conditioner, the Queen made him a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order for his service to the Royal Stable.

As he prepared his exit, the captain named his stepson Henry Cecil as his successor at Freemason Lodge. Cecil had been his assistant for four years, his education and experience preparing him to take the helm from his stepfather. Though his temperament differed from that of his stepfather and their relationship could be fragile at times, Henry picked up where the captain left off and crafted a Hall of Fame career of his own.

A legacy of excellence

Forty years after his death and a century after he took out his trainer’s license, Sir Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort lives on in racing’s record books, as the conditioner of champions and the mentor of a man named Cecil, the one who gave us Frankel in all of his glory. The friends of his time are all gone yet his regal bearing and enduring reputation for discipline and detail live on in the stories of the horses he conditioned.

His patience for developing horses yielded a trio of victories in the Ascot Gold Cup and a Triple Crown with a girl named Meld. It was his brilliance that capitalized on the untapped potential of Omaha, already an elite name in America, and brought him to the precipice of victory at Ascot.

The captain took his boyhood love of horses and turned it into his calling as a conditioner of champions for royalty on both sides of the Atlantic. Though his name may ring unfamiliar to 21st century ears, Cecil Boyd-Rochfort made his mark on the century that preceded it, etching his name into the record books many times over for King, Queen, country, and beyond.

The captain (left) and trainers Ben and Jimmy Jones with American Triple Crown winner Citation at Hialeah, c1949.

TopSpec Trainer of the Quarter - Tony Martin and Good Time Jonny

Article by Lissa Oliver

It might be hard for some to choose a single highlight from the Cheltenham Festival, but it was very easy indeed to single out a shrewd training performance by AJ (Tony) Martin, who is our TopSpec Trainer of the Quarter following Good Time Jonny’s fine win in the Pertemps Network Final Handicap Hurdle. Martin mapped a clever campaign to the Final and had the eight-year-old gelding spot-on for the day to secure Martin’s first win at the Festival since 2015.

Based in the tranquil Irish countryside at Trimblestown Stud in Kildalkey, County Meath, Irish handler Martin has the ideal facilities for both Flat and National Hunt horses. A successful amateur jockey in his day, Martin has now been training for over 20 years and has earned a reputation for getting the best out of his horses and for his patience at allowing every horse to progress at their own pace.

Just such a horse is Good Time Jonny, who notched two wins at Leopardstown in the 2021/22 season and promised enough to start in the Gr.1 Albert Bartlett Novices' Hurdle at last year’s Cheltenham Festival before being pulled up in the Gr.1 Novice Hurdle at Punchestown.

This season, his jumping let him down somewhat when he was tried over fences, although he managed a fourth place in the Beginners’ Chase at Listowel. Having lost his way a little, he bounced back with a qualifying run when third in the Pertemps Network Handicap Hurdle, enough to secure his place at Cheltenham in the Final. In between, he warmed up at Leopardstown, when hampered by a faller.

The ups and downs of jumping stood him in good stead, though. In the Final, Good Time Jonny lost ground at the start, was hampered by a second-flight faller and was just about last turning for home. Under a superb ride from Liam McKenna, he kept persevering and hit the front on the run-in to win, going away by three and a quarter lengths.

Martin was predictably delighted to land another Festival winner. “Days like this are the ones you live for. He was last at the top of the hill but Liam had the patience to sit and wait, and it turned out well," he says. "It’s been a few years now since we had a winner here, but it is worth the agony and the hardship. It’s absolutely brilliant. A bit of a gap makes it better!

“The horse has been coming along really well since Leopardstown last time, I just thought the ground might not suit him—he likes better ground, but he went through it well.

“We had a lot of good years and some bad luck, and it’s nice to be back with some good horses. They are not Gr.1 horses, but in their own category, they are all right. I have some great men, jockeys and staff behind me this year, and I’m just so happy for them. These colours, the Beneficial colours, have given us great days.

Product Focus

Three new products available for trainers this spring 2023

PAVESCO - TWYDIL® ARTRIDAY

NEW feed supplement for joints from TWYDIL®, Switzerland.

Since MSM has been registered as a controlled substance, we decided to launch on the equine market a product that can be used daily and long term.

Following our recent scientific investigations, it appears that the combination of chondroïtin, glucosamine, pro-anthocyanin and ASU brings an active and efficient support on the cartilage health and its functionality.

ASU means « avocado and soybean unsaponifiable fatty acids ». This extract is particularly efficient for the stabilisation of the cartilage extra-cellular matrix, bringing a noticeable preventive effect. The combination of these ingredients have an effect on all parts of the joints: cartilage, synovial fluid and membrane. The pro-anthocyanin fraction has a powerful anti-oxidant property with a high tropism for joints, so breaking the vicious circle conducting to lameness.

Horses show an improvement of their general suppleness and of their stride. The well-being is also taken into consideration because training is better tolerated.

50g daily for 30 days minimum is recommended to observe an improvement. It may be needed to continue for a longer period in sensitive horses.

The product is available in 1.5 kg pails.

For more information visit: www.twydil.com

NAF Five Star Metazone

By Dr Andy Richardson BVSc CertAVP(ESM) MRCVS, Veterinary Director at NAF

Whatever the challenge, keep your yard ‘in the zone’ with NEW NAF Five Star Metazone.

Metazone has been formulated by the Veterinary and Nutrition experts at NAF and is an innovative, evidence based nutraceutical that targets the support of natural anti-inflammatory pathways in all racehorses. The synergistic blend of plant based phytochemicals that make up this product support these pathways wherever they are needed in the body - whether that be for joints, hooves, tendons, ligaments, muscles or skin. The unique herbal complex of Metazone works in synergy wherever those triggers occur within the system, to ensure we maintain freedom from discomfort. Maintaining optimum comfort ensures racehorse welfare and provides an optimal environment for recovery and maximising athletic potential.

Unwanted or excessive inflammation is a major issue for the well-being and performance of horses in training and a major cause of lost training days and missed races. Metazone is the culmination of many years of research and knowledge gathered by the scientific team at NAF on how plant based phytochemicals can positively influence the body.

Formulated specifically to manage, relieve and control, Metazone provides nutritional support for common issues that may interrupt a training schedule. Metazone supports a horse’s natural anti-inflammatory responses, which are often under maximum stress when in training, helping them to stay sound through periods of repeated, strenuous exercise. The product is suitable when a short term boost is needed but may also be used for long term daily administration when comfort is key. The natural formula is gut kind and designed to work effectively without compromising gut health. It can be fed alongside any other NAF product that will support underlying structures as required.

Independently trialled, Metazone has been robustly trialled by equine researchers at The Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester in a blinded, cross-over designed trial, and assessed by a panel of external vets. Real results research also includes trials with leading trainers, who have all seen the benefit of getting their horses ‘in the Metazone’.

Metazone is available as a fast-acting liquid, in an instant use syringe and as palatable powder. The liquid comes in 5L and 1L sizes with the syringes available as 3 x 30ml and the powder is in a 1.2kg tub.

For more information on pricing and the product, contact NAF’s Racing Manager Sammy Martin on 07980 922041 or smartin@naf-uk.com.

Plusvital - Neutragast

Plusvital Neutragast is now available in pellets.

Ideal for fussy eaters, Neutragast Pellets promote gastrointestinal health in convenient & palatable soy protein base pellet form.

Using research proven ingredients to promote digestive performance the pellets contain key ingredients boswellia extract, calcified seaweed, saccharomyces cerevisiae and provides a source of B vitamins to help with food metabolism.

Boswellia extract (Terepenes and Boswellic acids) have been shown to have several beneficial effects including anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Boswellia compounds have been shown to be of benefit in cases of intestinal inflammation. This is achieved through modulation of the inflammatory cell (leukocyte) response.

Calcified seaweed has been reported to have a positive effect on buffering of pH in equine stomachs. Presented in the form of Lithothamnium Calcareum this acts as a safeguard against excess acid within the stomach.

Additionally Plusvital Neutragast Pellets contain the amino acid Threonine which is one of the main amino acid components of the protein mucin. Mucin forms a gel-like structure which makes up the mucosal barrier that protects the stomach wall against its own acidic secretions.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (active yeast) is a probiotic which promotes intestinal health through multiple pathways including increased fibre digestion.

As it is a pellet supplement it works well with pelleted feed or straight feed concentrates and can be used as part of a daily routine.

For more information visit: www.plusvital.com

Sarah Steinberg - One of Germany’s up-and-coming trainers

Article by Catrin Nack

Compared with leading European racing nations, Germany's figures are very small indeed. Roughly 2200 horses, trained by 70 licensed trainers are trained here. With a big chunk trained by a chosen few – think Marcus Klug, Henk Grewe, Andreas Wöhler or Peter Schiergen – the numbers for smaller stables become smaller still.

Few trainers train more than 100 horses at the best of times; the ‘powerhouse’ yards with 150+ or even 200+ horses – which are so common nowadays in England, Ireland and France – are simply non-existent in a racing country constantly boxing above its weight.

As does Sarah Steinberg, no pun intended.

Sarah Steinberg´s official training list comprises 26 horses, three of which are her own. This is small even by local standards. Sarah Steinberg makes no excuses: “I do not want to train more than 35 anyway.” Small, but brimming with quality, it is quality horses that she strives to train. “My owners do not want runners in low (rated) handicaps, and for them I do not want that either. We think big and aim big”

Steinberg is a salaried trainer, employed by the RTC Rennpferde Trainings-Center GmbH. The name behind the entity is that of Hans-Gerd Wernicke, a 93-year-old manufacturer of quality sleeping systems.

His company Wenatex was founded in Salzburg, and it is under that name that his horses race. Stall Salzburg has 13 horses in training – thus comprising 50% of Steinberg’s inmates.

A further five are owned by Brümmerhof Stud, a major owner-breeder and supporter of German racing. Famous as the breeder of Danedream – and infamous for selling her early in her 2yo season - Brümmerhofs Gregor Baum just closed his own private training facility in Hannover. His link to Sarah Steinberg could well point to her future. But let's look back into her already remarkable journey in racing before we dare to look into the future.

Sarah Steinberg is 34 years old, with no family ties in racing whatsoever. Her aunt kept Arabian horses, and early memories consist of watching the Germany Derby on TV; but she can’t recall her first Derby winner, “I wasn’t really interested, and I certainly did not catch fire early on.” Animals – horses and dogs – were part of her upbringing; and while circumstances were traumatic, the following story is early proof of the unusual dedication and commitment to the creature. “My father had a very serious accident. He was hospitalised for months and had to spend long weeks in rehabilitation after. This meant I had to look after the 30 Huskies (we owned) for more than a year, otherwise they would have been given away.” Steinberg was just eight years old.

She was given a holiday on a pony farm for a job well done after, and it was then that her fascination for horses took root.

Her education with horses was classic and western style. Racing came into her life by default rather than design. Yet again, it certainly wasn’t love at first sight.

With her parents pressing for a solid education, her growing passion for horses got in the way. A small local permit holder with eight horses – Steinberg had answered an advert in a local (non-racing) paper – could not provide the structure they desired.

But Germany's formal education system – even in racing – led to a visit to Cologne, still the administrative centre of German Racing. Here she was taken on by Andreas Trybuhl, son of a racing family and the first proper trainer who spotted her talent. Steinberg was on her way.

Well, sort of. It wasn´t that Deutscher Galopp had waited for a young female rider, with fancy ideas at that. Steinberg rode in a couple of races. Nineteen rides and two wins are hardly the stuff of legends. She then plied her trade as a work-rider — in big yards.

Leaving Trybuhl, she worked for Peter Schiergen, had a short stint with Marcus Klug and was riding out for Jens Hirschberger when he trained Adlerflug. But Steiberg was still ‘just’ a work-rider nonetheless.

When the opportunity came, Steinberg grabbed it with both hands. Enter Hans-Gerd Wernicke. By the time their paths crossed, Wernicke had been an owner for nine years, with group performer Poseidon Adventure and the wonderful Gp1 winner Night Magic – both trained in Munich by Wolfgang Figge.

Figge retired at the end of the 2015 season, and Wernicke was on the lookout for a new trainer. Again, it was an advert that changed the course of Steinberg’s life.

“I thought I really had nothing to lose. But I had nothing to recommend me either – no references, no proper job description to boost. After all, I was only a work-rider.” Wernicke liked what he read – liked even better what he heard when Steinberg detailed her ideas about training and didn’t ponder for long. It didn’t take Steinberg long to prove just how good of a choice she had been, either.

It wasn’t that Wernicke approached his new, young trainer with starry eyes. He was prepared to give her a chance, but at first it was with horses for whom she was second choice – horses from other yards, who for whatever reason didn’t, or couldn’t, fulfil their potential.

Night Wish, in March 2016, was her first winner as a fully fledged trainer; he was only the second starter she sent out. Better was to come when Night Wish again read the script and became her first pattern scorer when taking the Grand Prix de Vichy (Gp3) later that year.

In seven full seasons Steinberg has now, at home and abroad, trained 124 winners, 14 of them Group winners. This year she operated at a nearly 30% winner-to-starter ratio in her native Germany. She has trained a Classic winner in Fearless King (German 2000 Guineas, Gp2) – the first female trainer to do so in Germany – and Mendocino, was her first Gp1 winner, when scoring in German´s most prestigious open-age Gp1, the Großer Preis von Baden this past September.

Trainers simply do not come more hands-on than Sarah Steinberg. She rides six lots a day, she grooms, and she drives the horsebox. She even, unique among her peers, leads up nearly all her charges.

Finding good staff is a challenge even she cannot resolve, but Steinberg is the first to admit she isn’t easy to work for either. “I expect a lot and cannot tolerate mediocrity. I had to learn that I simply cannot expect employees to work as hard as I do.”

Invaluable assistance comes in the shape of René Piechulek, of Torquator Tasso-fame. The jockey's rise to fame is worth its own chapter, but he started riding out for Steinberg at the end of 2017, becoming attached to Stall Salzburg in the process.

With no chances of foreign jockeys, COVID accelerated his rise to salaried stable jockey. And he did become attached, quite literally, to Sarah Steinberg as well; they are life partners now.

“René is invaluable – simply irreplaceable to the yard; I simply could not do it without him. I am the trainer after all, he does as I tell him, but I would be lost without his feedback.” For Steinberg, training horses is a mission. With her background in classic riding, it is small wonder that above-average riding skills are essential for her staff.

“Horses need to use their backs, and they can only do this if they bend their necks properly. So much damage is done when horses do not use themselves right.”

On average, her horses are ridden about an hour a day, with an additional four hours spent in one of the six (four grass) paddocks. Daily, that is.

With few exceptions, racehorses in Germany are trained directly on the racecourse – Munich in Steinberg´s case – a base she cannot praise highly enough.

Crucially, Munich´s training centre is right next to the track itself with long and well-maintained grass and sand gallops, and with only a handful of trainers sharing those facilities.

Wernicke's generous approach and competitive nature developed just what Steinberg wanted in their own stables. “I really have everything I need; it’s top class. I have my private trotting ring; there is a covered hall. I have a salt box, which I use to great effect, and two solariums. The open country next to the training tracks is another plus; we have choices and can give the horses a change of scenery.”

She works closely with her trusted vets and a chiropractor, not to mention a top-class farrier. Conveniently, the RTC GmbH comes with a racing secretary too, so the time Steinberg has to spend in the office is very limited indeed.

“Really, I would never want to work self-employed. My system simply would not work with all those pressures attached.” Individuality is the key. “Of course, the basic work is the same for all horses, but the individuality starts creeping in once horses start showing their quirks. We love to get to the bottom of problems and want to bring the best out of every horse in our care.”

Remarkably, three of her 26 inmates have a German GAG (rating) of 90 or higher – roughly 106 plus in International ratings. Nowadays, Steinberg is responsible for selecting youngsters at the sales. Wernicke is a racing man and not a breeder.

The stable's flagbearer for the last couple of years has been the above-mentioned Mendocino, bred by Brümmerhof Stud and a son of the late Adlerflug.

Selected by Steinberg, he represents all she looks for in a horse. “I look at horses, not pedigrees. In fact, I couldn’t care less about the breeding. I need to see the horse's personality. I try to read their eyes, and how they play with their ears tell me something too. They need to be alert – lively. I don’t like the docile ones. A shorter back and strong back hands are essential to me, but I can forgive small mistakes if I feel the attitude is right. After all, it's all down to their character and their will to win.”

Offspring of the much missed sire Adlerflug, present their own challenges, but in Mendocino, Steinberg has found a horse of a lifetime.

The now 5yo has won three races from 11 starts and has provided Steinberg with that all-important win at the highest level, and he did take his team to Paris Longchamp on the first Sunday in October.

“I am accredited as his ‘lass’ and ride him myself every morning.” She rejects the notion that surely she will not lead him up when competing in a big race.

“Of course I will,” she muses. Steinberg has lost count of the winner´s ceremonies she missed because of her role as a ‘lass’ – something Wernicke had learned to accept. “He was a bit miffed when I kept skipping the ceremonies because I wanted to be with the horse after the race, so I pointed out that it's better to have those winners and no trainer, or not so fast horses. He can see the humorous side now.”

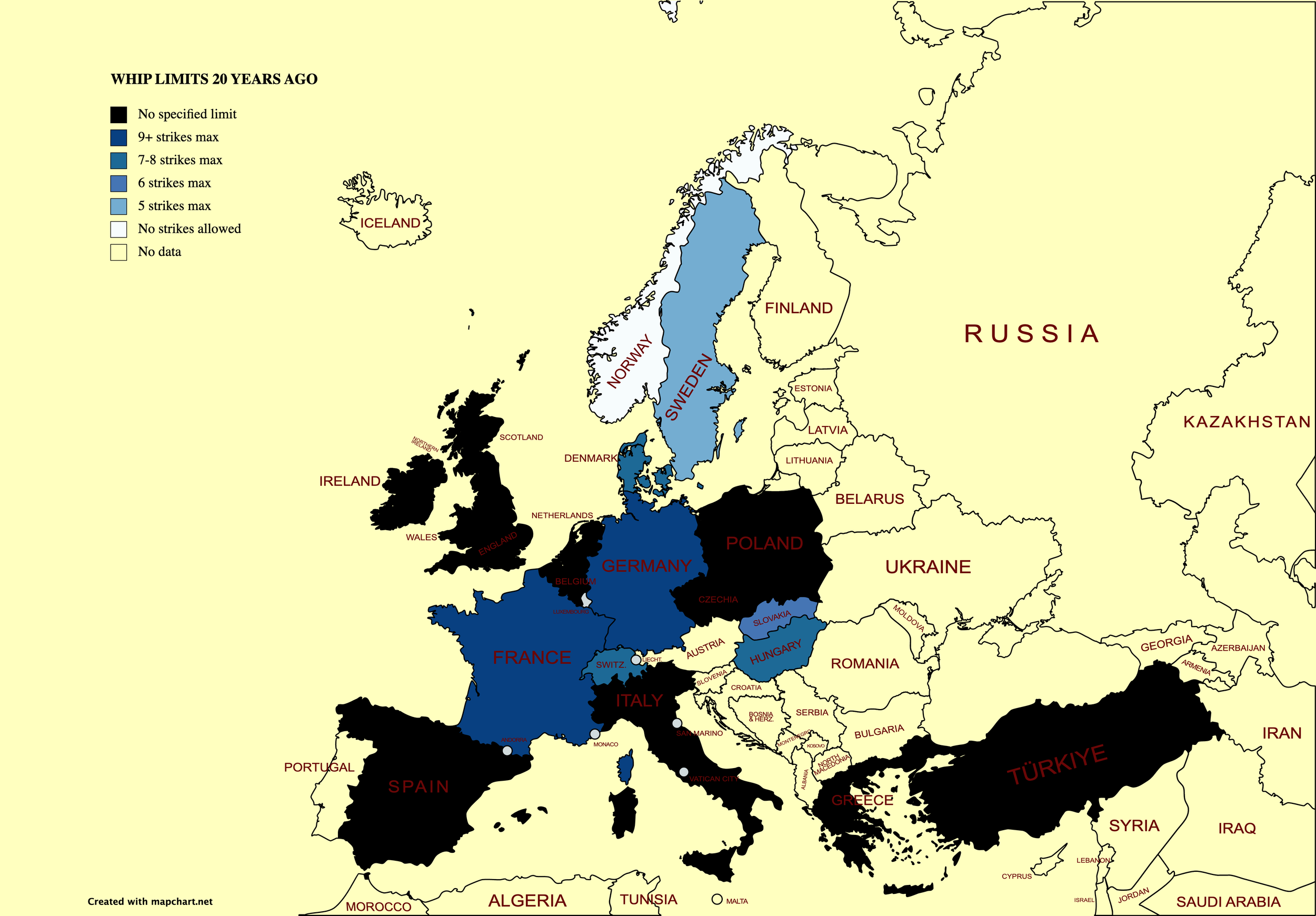

The whip-debate and animal welfare put extra pressure on German racing. Steinberg has a clear view on both: “The whip is essential – a life-saver for riders. With the short stirrups, we need it to correct but never to abuse. We need strict rules and even stricter penalties. As for animal welfare, I am in the game because I like horses – we all do. We like them, and we want the best. Performance is no cruelty to horses, and I firmly believe the majority of racehorses couldn’t be better cared for. There are black sheep in all walks of life, and much more must be done to educate about the good work that is done away from the public eye.”

Steinberg is realistic enough to wonder what the future holds, even though Wernicke shows no signs of stopping. The recent trip to Hong Kong (with Mendocino) came at Wernicke’s insistence and was Germany's sole representative.

There is no happy ending to report, as Mendocino proved worth his billing as a “character.” After behaving beautifully in the preliminaries, he reared in the starting stalls and refused to jump with the field – the first time he has shown such antics. But Steinberg wouldn’t be Steinberg if she wouldn’t rise to this challenge too.

Artificial Intelligence tools - and their growing use in racing

Book 1 of the Tattersalls October Yearling Sale is traditionally where some of the finest horseflesh in the world is bought and sold. The 2022 record-busting auction saw 424 lots pass through its hallowed rotunda for a total of 126,671,000 guineas. One of the jewels in the crown was undoubtedly lot 379, a Frankel colt out of Blue Waltz, who was knocked down to Coolmore's M.V. Magnier, joined by Peter Brant, for 1,900,000 guineas.

It is easy to see why lot 379 made Coolmore open its purse strings. He has a stallion’s pedigree, being out of a Pivotal mare. His sire has enjoyed a banner year on the track, with eight individual Gp/Gr1 winners in 2022. He is a full brother to the winning Blue Boat, himself a 450,000 guineas purchase for Juddmonte Farms at Book 1 in 2020. Lot 379 is undeniably impressive on the page.

But it is not his impeccable pedigree that makes Tom Wilson believe lot 379 has the makings of a future champion. “The machine doesn’t have any biases. It doesn’t know whether it’s a Galileo or a Dubawi or a Havana Grey,” he says. “The machine just looks at the movement of the horse and scores it as it sees it. It has no preconceptions about who the elite sires in the market are. It’s completely neutral.”

The “machine” to which Wilson is referring is, in reality, a complex computational model that he claims can predict with 73 percent accuracy whether a horse will be elite (which he defines as an official rating of 90 or above, or the equivalent in its own jurisdiction) or non-elite (horses rated 60 or below) based on its walk alone. It’s a bold claim. So how does he do it?

First, Wilson taught an open source artificial intelligence tool, DeepLabCut, to track the movements of the horse at the walk. To do this, he fed it thousands of hours of footage. He then extracted around 100 frames from each video and manually labelled the body parts. “You teach it what a hock is, what a fetlock is, what a hip is,” he explains. “Eventually, when you feed new videos through, it automatically recognises them and plots the points. Then you can map the trajectories and the angles.”

He then feeds this information into a separate video classification algorithm that analyses the video and compares it to historic data in order to generate a predicted rating for the horse. “Since 2018, I’ve taken about 5,000 videos of yearlings from sales all around the world with the same kind of biometric markers placed on them and then gone through the results and mapped what performance rating each yearling got,” he says. “So we’re marrying together the video input from the sale to the actual results achieved on track.”

Lot 379 has a projected official rating of 107 based on his biomechanics alone, the highest of all the Frankel’s on offer in Book 1 (yes, even higher than the 2,800,000 gns colt purchased by Godolphin). Wilson’s findings have been greeted with scepticism in some quarters. “There’s so many other factors that you can’t measure,” points out trainer Daniel Kübler. “There’s no way an external video can understand the internal organs of a horse, which you can find through vetting. If it’s had an issue with its lungs, for example, it doesn’t matter how good it looks. If it’s inefficient at getting oxygen into its system, it’s not going to be a good racehorse.”

“It’s not a silver bullet,” concedes Wilson. “There are multiple ways to find good horses. It’s just another metric, or set of metrics, that helps.” But is it really “just another metric,” or the opening salvo in a data revolution that has the potential to transform the way racehorses are bought and sold?

Big data. Analytics. Moneyball. It goes by many names, but the use of data in sports is, of course, nothing new. It was brought to popular attention by Michael Lewis in his 2003 book Moneyball and by the 2011 film of the same name starring Brad Pitt.

It charted the fortunes of the Oakland Athletics baseball team. You know the story: Because of their smaller budget compared to rivals such as the New York Yankees, Oakland had to find players who were undervalued by the market. To do this, they applied an analytical, evidence-based approach called sabermetrics. The term ‘sabermetrics’ was coined by legendary baseball statistician Bill James. It refers to the statistical analysis of baseball records to evaluate and compare the performance of individual players. Sabermetrics has subsequently been adopted by a slew of other Major League Baseball teams (in fact, you would be hard pressed to find an MLB team that doesn’t employ a full-time sabermetrics analyst), and ‘moneyball’ has well and truly entered the sporting lexicon on both sides of the Atlantic.