How do you maximise Equine health and performance?

QUANTIFY TRAINING WORKLOAD In association with Arioneo

One of the primary goals of any trainer is to establish a suitably high workload to develop the desired qualities, while controlling the amount of exhaustion caused by the training. Indeed, an excessive amount of fatigue might lead to the threshold associated with injury. Therefore, measuring a horse's training helps to develop competitiveness while respecting the physical and mental integrity of the horse.

How to adapt an untrained racehorse’s training?

An undertrained horse has never been trained with a workload for what is required during a race as their body would be unable to keep up with the effort. To detect an under-trained horse, the analysis of physiological parameters coupled with the analysis of sports parameters provides a good key to analysis. Indeed, a horse for which exercise has been easy will not reach its maximum heart rate (HR) and its HR curve will drop immediately after the rider stops exercising.

CONCRETE EXAMPLE

In the following example, Monsieur Arion is a Group horse that arrived in October 2020 at his new trainer’s stable. As an Equimetre user, he was able to track Monsieur Arion’s training from the minute he arrived to begin developing his database.

After winning many races, Monsieur Arion’s trainer discovered that his blood results were low after a race. As a result, training was put on hold for a while.

Monsieur Arion continued training after his recovery, but he never achieved the fitness he had before to his racing success.

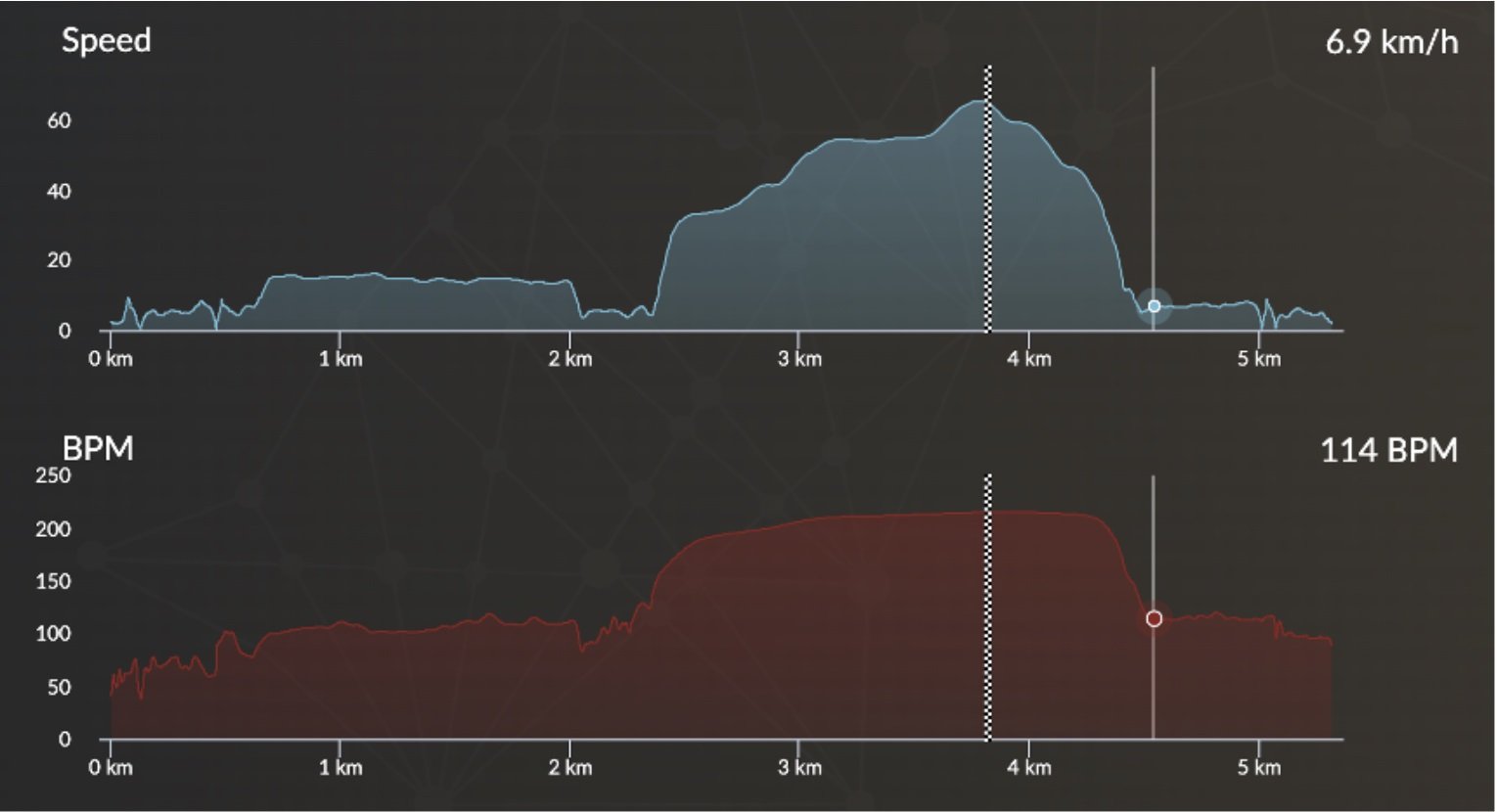

Here we can see the decrease in fitness level.

Indeed, based on the statistics shown above, Monsieur Arion’s recovery ability has worsened slightly for a same degree of training: his heart rate after exercise is 166 BPM, up from 114 BPM when he came in October. This is also true for his recovery 5 minutes after the effort ends.

The trainer was also able to evaluate the differing fitness data. By interviewing Monsieur Arion’s previous trainer, he was able to confirm that his training intensity had decreased because of their different training approaches. He decided to increase the training workload by increasing the distance and intensity.

We can see on the data below that thanks to this training individualisation, Monsieur Arion’s fitness has improved: heart rate 5mins after the effort has decreased.

Here we can see the fitness improvement, with better recovery parameters.

With this method, Monsieur Arion’s fitness improved, and it led to another GR 1 victory.

About Equimetre – Racehorse Monitoring system

Developed specifically for racing professionals, the sensor and the analysis platform allow trainers to collect and analyze their horses’ data simply and quickly.

The X Factor - Growth spurts in young horses: What can we learn from 'human' research into growth and maturation in sport and exercise?

By Alysen Miller

Ask anyone to list five famous Belgians, and odds are that Kevin De Bruyne’s name will make an appearance. The Manchester City midfielder is widely regarded as one of the best footballers of his generation. Yet you might not have heard of him at all were it not for an innovative talent development scheme in his home country that could influence the way we select, train and manage racehorses.

Traditionally young footballers, like racehorses, are grouped age. By contrast, bio banding is the process of grouping athletes on the basis of attributes associated with growth and maturation, rather than chronological age. “Whether you mature earlier or later has quite a lot of bearing in sport, where greater speed, strength or power can be important,” explains Professor Sean Cumming, an affable Orkney Islander based at the University of Bath who studies growth and maturation. “When you look at children in sport, we group them by age for competition and for training. And while age groups are great in so far as it allows you to match kids of similar cognitive development, motor skills and experience, the challenge is that kids can vary hugely in terms of their biological maturity.” Although the effect of this ‘maturity bias’ doesn’t kick in until pubertal onset at around 11 or 12 years of age, the variance in biological maturity can already be anything up to five or six years by that point.

The concept that relative age can play a determinative role in future sporting success is not new. It explains why broodmares are covered in spring to produce foals in February and March. A winter-born colt running in the Derby in early June of its three-year-old year may be up to 10% of its life older than a spring-born animal—an unquestionable advantage. Or is it?

Indeed, it’s not only in horse racing where the orthodoxy around the so-called ‘relative age effect’ holds sway. In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell notes that a disproportionate number of elite Canadian hockey players are born in the earlier months of the calendar year.

The reason, he posits, is that since youth hockey leagues determine eligibility by calendar year, children born in January are pitted against those born in December. Because the earlier-born children are likely to be larger than those born later (at least until somatic factors kick in), they are often identified as better athletes.

This, in turn, gives them more exposure to better coaching, and the gap between the two groups widens. Sociologist Robert K. Merton has dubbed this the ‘Matthew Effect’ after a verse in the Gospel of Matthew: "For unto everyone that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance. But from him, that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.”

But, cautions Professor Cumming, this only tells part of the story: “What even a lot of the academics get wrong is that relative age and maturity are not one and the same. In fact, our data shows that only about 8% of the relative age effect in academy football can be explained by physical maturity. It’s quite possible to be the oldest kid in the age group but also the least mature, or the youngest kid in the age group but also the most mature.”

The focus on relative size and strength alone, in other words, can create a bandwagon effect. “If you’re looking to identify and develop the most talented young athletes, then it’s going to cloud your vision. It’s going to make some kids look fantastic and some kids look quite poor.” Perhaps tellingly, the last January-born Derby winner, Pour Moi, came in 2008. The youngest winner of the last 10 years, Anthony Van Dyck, was born in mid-May.

Machester City and Belgium superstar midfielder Kevin De Bruyne is the Royal Belgian Football Association’s Programme of the Futures’ most famous graduate

Enter De Bruyne. The Royal Belgian Football Association’s Programme of the Futures, as it is known, allows late-developing players to hone their skills by playing mostly friendly matches against teams of the same physical maturity level, irrespective of age. De Bruyne is the scheme’s most famous graduate. Other members of the late-developer club include Dries Mertens, Thomas Meunier and Yannick Carrasco. By deliberately creating a climate in which late-maturing players get a second bite at the cherry, a country with a population of just 11 million has become a global footballing superpower. Unsurprisingly, other nations are starting to catch on, and several similar programmes have sprung up across the UK and Europe.

Every professional football club has a story about the one who got away—the player that was cut from their programme for being too physically small, from Jamie Vardy (released by Sheffield Wednesday at 15) to Harry Kane (the now 6’2” striker was released by Arsenal at the age of nine). But the consequences are more far-reaching than just missing out on the next footballer superstar. There is compelling evidence to suggest that tailoring the training load to the stage of the athlete’s biological maturity can reduce injuries. The amount of time spent off through injury during an athlete’s formative years is thought to be one of the single biggest factors that determines future professional success.

Since overuse injuries and stress fractures all peak when the athlete is going through their pubertal growth spurt, it is important to identify when an athlete is entering this phase and adjust the load accordingly. As Professor Cumming explains, “Because we know the growth spurt typically takes off at around 85-86% [of the athlete’s predicted adult height] and peaks at around 90-91%, as soon as they move into that phase we can change the training prescription to more developmentally focused stuff—coordination, balance, core strength—all things that are going to help the child transition to a phase when their body is changing rapidly, when they’re more at risk of certain types of injuries.” Early evidence from clubs using the method has pointed to a 72% reduction in injuries.

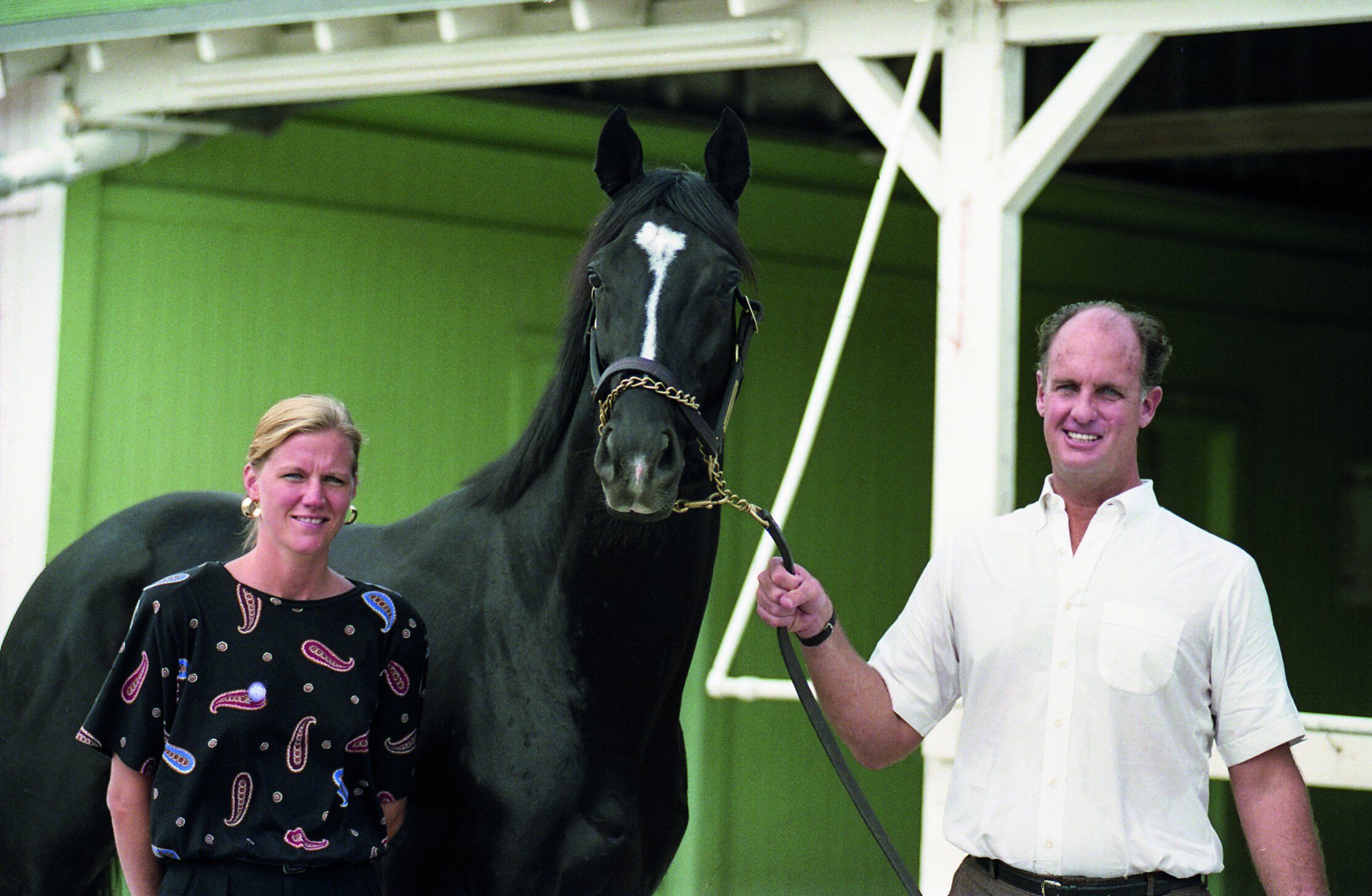

Daniel & Claire Kubler have been bio-banding their horses using knee x-rays, among other metrics, to determine when to increase a horse’s workload

And it’s not just football clubs that are starting to understand the benefits of bio-banding. Daniel and Claire Kübler have been bio-banding their horses using knee x-rays, among other metrics, to determine when to increase a horse’s workload. “We back most of our own horses and train them away to where they can canter relatively comfortably at a normal speed,” says Daniel. “Once a horse can canter away, that’s when we go in and do that first set of x-rays.” The horses are given a grade based on the degree of fusion in the growth plates in the knee, with A being an open growth plate, B being partially closed and C being a closed growth plate. “Those really open ‘A’ horses, you might say, ‘OK, there’s no point—give it a break,’” says Daniel. The C’s, likewise, tend to be easy cases. “It’s really the B horses that are the interesting ones, where you have to make a bit more of a decision,” says Daniel. “What we don’t want to be doing is increasing the workload on a horse that’s relatively immature.”

Although the growth rate in horses varies somewhat by breed, most horses do not reach full physical maturity until around six years of age, with larger breeds like draft horses still growing until eight years of age. A two-year-old horse is an adolescent; it has reached approximately 97% of its mature height by 22 months but critically, its bones will not fully fuse for another four years.

@Equine partnership - equinepartnership.ie

Like humans, horses grow distal to proximal—that is, from the feet up—with the pasterns developing first, fusing at around six months, followed by the cannons at around the one-year mark. The pelvis and spine fuse last. It is during the horse’s two-year-old year that the major leg bones—the radius, ulna and tibia—will fuse. It is therefore important to understand when a horse is entering its growth spurt and tailor its regime accordingly. “It’s about injury reduction,” argues Daniel. “Young athletes are highly susceptible to injury, and by recognising and identifying the growth spurt, you’re massively reducing the injury rate by adapting the training load.”

“The knees are the most delicate bit,” he goes on. “That’s where most of your injuries occur that can cause problems down the line. When you’ve got one with poor grading on its knees, it’s being pre-emptive in your training,” he continues. “You would train that horse a bit more conservatively and not push it quite as hard. You might spend more time on an incline gallop, or you might introduce swimming into the horse’s routine so that you’re putting a bit less concussion through those joints. And hopefully you’re getting the benefit down the line, because they haven’t been pushed too hard, too young.”

Joint licence-holders Daniel and Claire have long advocated for the role of science in training racehorses. “We’re not scared of it,” says Claire, who holds a degree in physiology from Cambridge University. “Having the additional awareness of it gives you a greater understanding,” she asserts. Coming from a non-racing background, meanwhile, has allowed Daniel to approach training with something of a fresh perspective: “It’s the critical questioning. A lot of things in racing are done because that’s the way they’ve always been done, and you can work backwards and find that the reason they work is because, scientifically, it stacks up. But there’s other things where you actually go and look at the science, and it doesn’t make any sense to do that.”

“I love reading about human sports science and listening to podcasts to get ideas,” he explains. “Essentially we’re all mammals, and although there are some differences, there are also a lot of similarities.”

Following the science has not only allowed the Küblers to produce happy, healthy horses—“I’d like to say our horses are very sound and durable,” notes Claire—it has helped them manage owners’ expectations. “Owners enjoy the insights and better understanding themselves as to how the horses progress and develop,” she says.

Feedback from work riders is just as important as the science and can provide and can provide as much insight into the horse’s state of growth as an x-ray

“As a trainer, sometimes you can look at a horse and you can see it’s backwards and it needs time,” says Daniel. “What’s helpful about having the knee x-rays is that it’s a very visible thing to show to someone who doesn’t necessarily understand horses particularly well or isn’t used to them. It’s a simple way to say, ‘Your horse is immature.’ That’s a helpful tool as a trainer in terms of being able to communicate very clearly with your owners.” Posting regularly on social media, meanwhile, has attracted interest from outside the sport—including from Professor Cumming himself, who reached out to Daniel through Twitter.

The science is certainly compelling. But, emphasises Daniel, you cannot rely on data alone. “You can’t solve the challenge of training racehorses purely with numbers in the same way that I don’t think you can solve it purely just by looking anymore, because you’re not looking at bits of information. It’s an example of using a scientific, data-driven, analytical approach to enhance the welfare and time the horse’s development in the right way for that individual,” he says.

“The numbers don’t lie, but still you need the horsemanship,” agrees Claire. Feedback from the work riders, she says, can provide as much insight into a horse’s state of growth as an x-ray. “They can pick up on the horse, whether it’s still maturing and doesn’t quite mentally understand what it’s doing. Then you can come up with ideas together as a team,” she says.

In a climate where racing, and equestrian sport in general, is the subject of increasing scrutiny—both from outside the sport and from within—t is submitted that any sports science techniques that can deliver tangible welfare benefits to the horse should be embraced.

“At the end of the day, they have to go out and race, and they all have to be sound enough to do that,” says Daniel.

“You’re always trying to find ways to help get an edge on the track—to get more winners,” agrees Claire. “But you also just want to do the best for the horse so you’re getting a sound horse to achieve its optimum best.”

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS

4 x print issue and online subscription to European Trainer & online North American Trainer. Access to all digital back issues of both editions.

Your subscription will start with the October - December 2025 issue - published at the end of September.

If you wish to receive a copy of the most recent issue, please select this as an additional order.

How to adapt the race distance to win

In association with Arioneo

How often have you heard that a horse is bred to race a certain distance? That may be accurate, but sometimes stride length and frequency data say otherwise. Some research shows the interest in modelling a horse’s race distance using locomotion data. Thus, we could theoretically use the measurement of a horse’s stride frequency to determine his ideal distance.

Although it may not appear to be a big deal, extending 100 or 200m to the regular race distance might help a horse’s season in specific circumstances.

Madame Arionea’s story – Concrete example

· 4yo filly that we will call Madame Arionea

· During her 2yo season, she raced over 1100m (5.5f) and ran well

· During her 3yo season, she didn’t show any progress even though she showed good fitness abilities during training

Why did this promising mare fail to advance in her three-year-old season over 1100m (5.5f) while demonstrating strong physical ability in training?

1. Assessing her fitness

To begin analysing Madame Arionea’s underperformance, we will review her cardiac data from her three-year season.

We can evaluate Madame Arionea’s recovery and thus quantify her fitness level by studying the evolution of heart rate and speed at the same time. If it is insufficient, this may explain her poor performances.

Heart rate and speed curves from the Equimetre platform

Madame Arionea recovers rather effectively after her effort, as seen by a fall in the heart rate curve at the same time as the decrease in the speed curve.

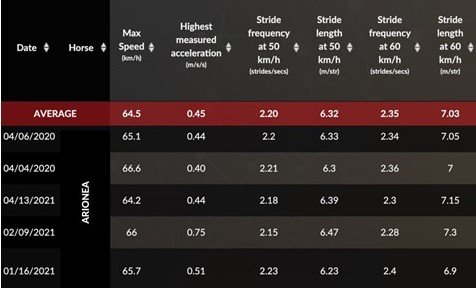

Analytics - Equimetre platform

The data in this table shows the various exercises performed at speeds greater than 60km/h. This enables us to assess recovery capability and its progression following a high-intensity activity.

The data provided above allow us to confirm that Madame Arionea is in excellent physical condition.

Indeed, her recovery ability is classified as normal both immediately after the activity and 15 minutes afterwards.

About Equimetre – Racehorse Monitoring system

2. A better understanding of the stride profile

Following this discovery, another type of data should be investigated: locomotion. Stride length and stride frequency analysis has been suggested as a technique for modelling a racehorse’s preferred distance. Thus, by quantifying a horse’s stride frequency, one may possibly determine the race distance over which he performs best.

Good to know

· According to the theory, a large stride length paired with a less remarkable stride frequency correlates to a miler or stayer stride profile. A profile that combines a very high stride frequency with a less spectacular stride length, on the other hand, belongs to a sprinter.

· It is important to remember that horses are living beings and high-level athletes, and that these principles on the pair stride length/frequency pair do not represent a precise science but provide valuable references.

To assess Madame Arionea’s stride abilities, we shall examine her stride frequency and length at a speed of 60 km/h rather than at top speed. This enables us to make appropriate comparisons between training sessions and investigate this parameter under the same settings.

From the above data, we can define Madame Arionea’s stride profile.

Because her stride frequency does not enable her to compete with horses with the profile of a Sprinter, this mare would be better comfortable at a distance slightly longer than 1100m (5.5f).

3. Madame Arionea’s acceleration strategy

Let’s have a look at Madame Arionea’s acceleration strategy to round up this examination. This involves measuring her change in stride length and stride frequency during the training’s acceleration phase. This technique enables us to objectively assess Madame Arionea’s acceleration.

Madame Arionea reaches her maximum speed by increasing of her stride length (green curve) first. What does this tell us? Her acceleration time will be longer, but this will allow her to save her energy since the heart rate is based on the horse's stride rhythm. In a longer stride, she breathes longer, and inhales a greater volume of air. Thus, the race distance chosen should allow Madame Arionea to take the time necessary to reach her maximum speed during the final sprint.

WHAT DECISION DID THE TRAINERS MAKE REGARDING THIS ANALYSIS?

Given Madame Arionea’s positive 2-year-old season over 1100m and her locomotion data, the trainers decided to progressively increase her racing distance and attempt her over 1300 / 1400m (6.5f / 7f).

Madame Arionea was not monitored throughout her two-year-old season, but we can make the following assumptions. The mare’s locomotion changed once she gained strength and endurance. Her stride length grew while her stride frequency decreased. As a result, for her to perform successfully, her racing distance needed to be increased to provide her time to accelerate.

Madame Arionea won her first race over 1300m (6.5 f), and never race again under 1300m.

The gait of a horse can change as he ages. For example, even if a horse had a good sprint season as a two-year-old, his locomotion evolution must be quantified. You may check that the distance chosen for future races is adequate for his locomotor profile this manner.

Remembering Sunday Silence and his lasting global influence

By Nancy Sexton

For over a quarter of a century, there has been an air of inevitability within Japanese racing circles. Sunday Silence dominated the sire standings in Japan for 13 straight years, from 1995 to 2007—his last championship arriving five years after his death. He was a true game changer for the Japanese industry, not only as a brilliant source of elite talent but as a key to the development of Japan as a respected racing nation. Any idea that his influence would abate in the years following his death was swiftly quashed by an array of successful sire sons and productive daughters. In his place, Deep Impact rose to become a titan of the domestic industry. Others such as Heart’s Cry, Stay Gold, Agnes Tachyon, Gold Allure and Daiwa Major also became significant sires in their own right. Added to that, Sunday Silence is also a multiple-champion broodmare sire and credited as the damsire of 203 stakes winners and 18 champions. “Thoroughbreds can be bought or sold,” says Teruya Yoshida of Shadai Farm, which bought Sunday Silence out of America in late 1990 and cultivated him into a global force. “As Nasrullah sired Bold Ruler, who changed the world’s breeding capital from Europe to the U.S., one stallion can change the world. Sunday Silence is exactly such a stallion for the Japanese thoroughbred industry.”

Sunday Silence ant Pat Valenzuela winning the 1989 Kentucky Derby

Sunday Silence has been dead close to 20 years, yet the Japanese sires’ table remains an ode to his influence. In 2021, Deep Impact landed his tenth straight sires’ championship with Heart’s Cry and Deep Impact’s rising son Kizuna in third and fourth. Six of the top 11 finishers were sons or grandsons of Sunday Silence. Deep Impact was also once again the year’s top sire of two- and three-year-olds. Against that, it is estimated that up to approximately 70% of the Japanese broodmare population possess Sunday Silence in their background. All the while, his influence remains on an upswing worldwide, notably via the respect held for Deep Impact. A horse who ably built on the international momentum set by Sunday Silence, his sons at stud today range from the European Classic winners Study Of Man and Saxon Warrior—who are based in Britain and Ireland—to a deep domestic bench headed by the proven Gp 1 sires Kizuna and Real Impact alongside Shadai’s exciting new recruit Contrail. In short, the thoroughbred owes a lot to Sunday Silence.

Inauspicious beginnings

Roll back to 1988, however, and the mere idea of Sunday Silence as one of the great fathers of the breed would have been laughable. For starters, he almost died twice before he had even entered training. The colt was bred by Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds Ltd in Kentucky with appealing credentials as a son of Halo, then in his early seasons at Arthur Hancock’s Stone Farm. Halo had shifted to Kentucky in 1984 as a middle-aged stallion with a colourful existence already behind him. By Hail To Reason and closely related to Northern Dancer, Halo had been trained by Mack Miller to win the 1974 Gr 1 United Nations Handicap.

It was those bloodlines and latent talent that prompted film producer Irving Allen to offer owner Charles Englehard a bid of $600,000 for the horse midway through his career. Allen’s idea was to install Halo in England at his Derisley Wood Stud in Newmarket; and his bid was accepted only for it to be revealed that his new acquisition was a crib-biter. As such, the deal fell through, and Halo was returned to training, with that Gr 1 triumph as due reward.

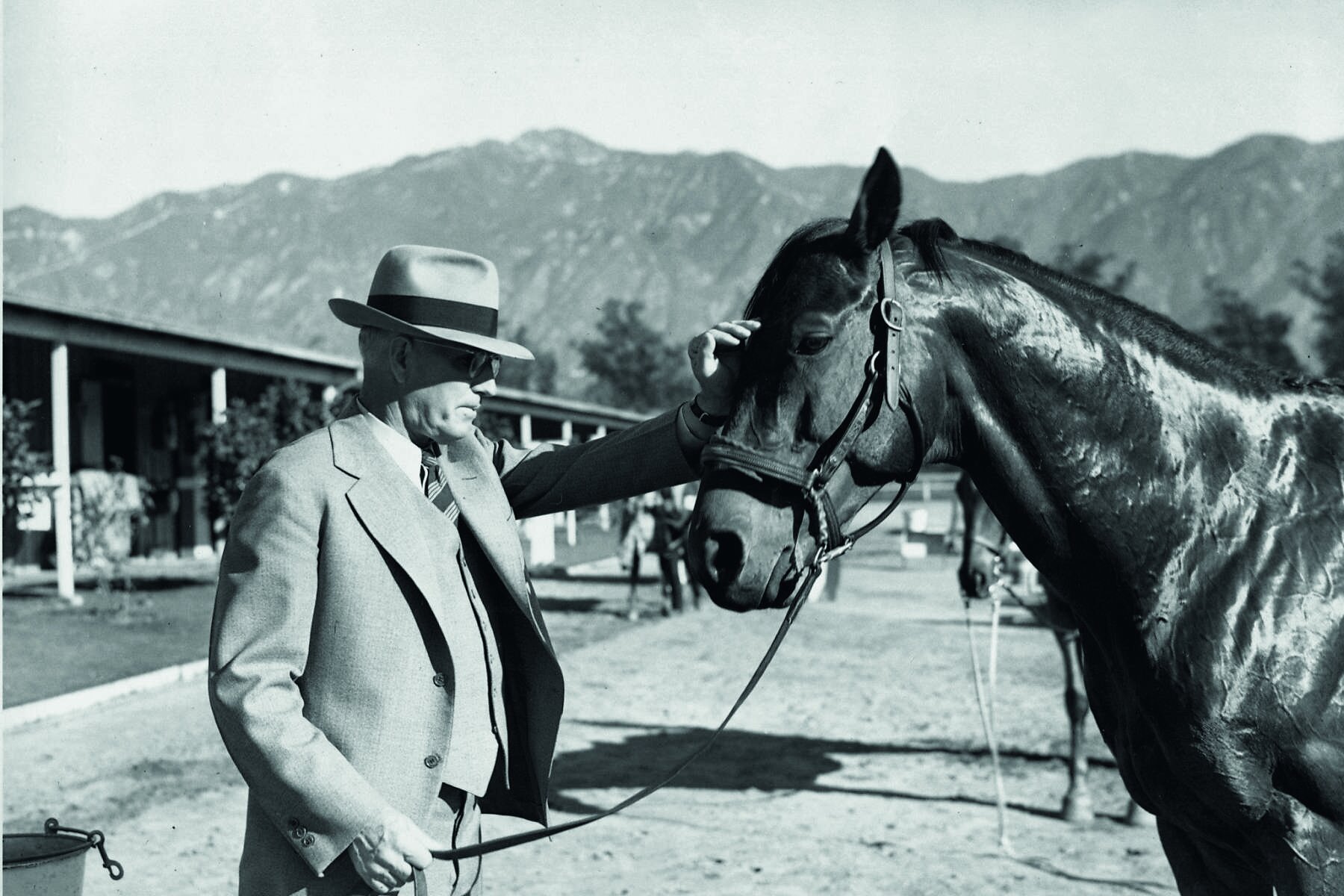

Queen Elizabeth II meets Halo

Would Halo have thrived in England? It’s an interesting question. As it was, he retired to E. P. Taylor Windfields Farm in Maryland, threw champion Glorious Song in his first crop, Kentucky Derby winner Sunny’s Halo in his third and Devil’s Bag—a brilliant two-year-old of 1983—in his fourth. Devil’s Bag’s exploits were instrumental in Halo ending the year as North America’s champion sire. Within months, the stallion was ensconced at Stone Farm, having been sold in a deal that reportedly valued the 15-year-old at $36 million. Chief among the new ownership was Texas oilman Tom Tatham of Oak Cliff Thoroughbreds. In 1985, Tatham sent the hard-knocking Wishing Well, a Gr2-winning daughter of Understanding, to the stallion. The result was a near black colt born at Stone Farm on March 26, 1986.

It is part of racing’s folklore how Sunday Silence failed to capture the imagination as a young horse—something that is today vividly recalled by Hancock.

“My first recollection of him was as a young foal,” he recalls. “He was grey back then—he would later turn black.

“I was driving through the farm, and I looked into one of the fields and saw this grey colt running. The others were either nursing or sleeping, but there was this colt running and jumping through the mares.

"We had a number of foals on the place at the time, and I wasn’t sure which one it was, so I rang Chester Williams, our broodmare manager. I said, ‘Hey Chester, who is this grey foal in 17?’ And he told me it was the Wishing Well colt. He was flying—he would turn at 45 degree angles and cut in and out of the mares. And I remember thinking even then, ‘Well, he can sure fly.’

“Then on Thanksgiving Day later that year, he got this serious diarrhea. We had about 70 foals on the farm, and he was the only one that got it; we had no idea where he got it from. Anyway, it was very bad. I called our vet, Carl Morrison, and between 9 a.m. and midday, we must have given him 23 litres of fluids.

“We really thought he was going to die, but Sunday Silence just wouldn’t give up. Obviously it set him back some; he was ribby for a few weeks. But I have never seen anything like it in a foal during 50 years at Stone Farm, and at Claiborne before then; and I remember thinking then that it was a spooky thing for him to get it and then to fight through it the way he did.”

Arthur Hancock

As Hancock outlines, Sunday Silence was very much Halo’s son—not just as a black colt with a thin white facial strip but as a tough animal with a streak of fire. Halo had arrived from Maryland with a muzzle and a warning. Confident that a muzzle was an overreaction, Stone Farm’s stallion men worked initially without it, albeit against Hancock’s advice. It wasn’t long until the muzzle went back on. Not long after his arrival, Halo ‘grabbed the stallion man Randy Mitchell in the stomach and threw him in the air like a rag doll.’

“Halo then got on his knees on top of Randy,” recalls Hancock, “and began munching on his stomach. Virgil Jones, who was with Randy, starts yelling at Halo and hitting him with his fist. Halo let go, and they managed to get him off. “After that, the muzzle stayed on.”

Sunday Silence possessed a similar toughness. Indeed, that mental hardiness is a trait that continues to manifest itself in the line today, although not quite to the danger level of Halo.

“Sunday Silence had a lot of guts and courage, even then,” remembers Hancock. “I remember being down at the yearling barn before the sale and hearing this yell. It was from one of the yearling guys, Harvey. Sunday Silence had bitten him in the back—I’d never had a yearling do it before then and haven’t had one since.”

He adds: “When he came back here after his racing days, we had a photographer come to take some shots of him. Sunday Silence was in his paddock, and we were trying to get him to raise his head. I went in there and shook a branch to get his attention. Well, he looked up, bared his teeth and started to come after me—he was moving at me, head down like a cat. And I said, ‘No you’re ok there boy; you just continue to graze’ and let him be.

“He was Halo’s son, that’s for sure, because Wishing Well was a nice mare. Sunday Silence had a mind of his own, even as a yearling. I remember we couldn’t get him to walk well at the sales because he’d pull back against the bit all the time.”

It was that mental toughness and the memory of Sunday Silence flying through the fields as a young foal that remained with Hancock when the colt headed to the Keeneland July Sale. Then an individual with suspect hocks—a trait that still sometimes manifests itself in his descendants today—he was bought back on a bid of $17,000.

Staci and Arthur Hancock

“I thought he’d bring between $30,000 and $50,000,” he says. “So when it was sitting at $10,000, I started bidding and bought him back at $17,000. I took the ticket to Tom Tatham out the back of the pavilion and said, ‘Here, Tom, he was too cheap; I bought him back.’ And Tom said, ‘But Ted Keefer [Oak Cliff advisor] didn’t like him, and we don’t want him.’

“I remember we had another one that was about to sell, so I just said, ‘Ok Tom,’ put the ticket in my shirt pocket, walked away and thought, ‘Well, I just blew another $17,000.’

Another scrape with death

Hancock then tried his luck at the two-year-old sales in partnership with Paul Sullivan. The colt was sent to Albert Yank in California and catalogued to the Californian March Two-Year-Old Sale at Hollywood Park, again failed to sell—this time falling to World Wide Bloodstock (aka Hancock)—on a bid of $32,000, well below his owner’s valuation of $50,000.

“I told Paul and he said, ‘Well, I’ll take my $16,000 then,’” recalls Hancock.

So the colt was loaded up for a return trip to Kentucky. Then more ill-luck intervened. The driver suffered a fatal heart attack while on a north Texas highway, and the van crashed, killing several of its load. Sunday Silence survived but was injured.

“Sunday Silence was in the vets for about a week,” says Hancock. “He could hardly walk, and then Carl Morrison rings me and says, ‘Arthur, I think he’s a wobbler.’ I said, ‘What are you going to do?’ He said that all he could do was leave him in a paddock and see what happened.

“So he left him out there, and about a week later, he rings me and says, ‘You need to come to barn 16 and see this Wishing Well colt.’ It was unbelievable. I went down there, and there he was, ripping and running around just like he was a foal. It was a miracle—a spooky thing.”

Therefore Sunday Silence had already lived a pretty full life by the time he joined Charlie Whittingham in California. A true master of his profession, Whittingham handled over 250 stakes winners during his 49 years as a trainer, among them such champions as Ack Ack, Ferdinand and Cougar alongside the European imports Dahlia and Exceller. Appropriately, Cougar would go on to stand at Stone Farm, where he sired Hancock’s 1982 Kentucky Derby winner Gato Del Sol.

“Charlie Whittingham had seen Sunday Silence in California and rang me to ask about him,” says Hancock. “I told him I’d sell him half to $25,000. And he said, ‘But you bought him back for $32,000.’ Well the year before, we’d had Risen Star [subsequent winner of the Preakness and Belmont Stakes] go through Keeneland for $250,000. Charlie had asked about taking half of him, but we had wanted $300,000, so said, ‘Sure you can buy half for $150,000.’ And he had declined.

“I reminded him of that, and he chuckled and said, ‘Well, I’d better take it this time.’”

He adds: “Charlie was a brilliant horseman with a lot of experience. He was very smart. He had a sixth sense about horses. And he had great patience, like those great trainers do. Without Charlie, I don’t think Sunday Silence would have reached the level that he did. He just took his time with him.”

Whittingham paid Hancock $25,000 for a half share in the colt and later sold half of that share to a friend, surgeon Ernest Galliard. Within no time, that looked like a good bit of business.

It is a fine reflection of the trainer and his staff, in particular work rider Pam Mabes, that Sunday Silence’s temperament was successfully honed. In Jay Hovdey’s biography of the trainer, the colt is likened to ‘Al Capone singing with the Vienna Boys Choir’—his morning exercise routinely punctuated by bad behaviour.

“They’d take him out every day before dawn,” recalls Hancock. “I remember he had a thing about grey lead horses. Every time he saw one, he’d just go after it.

“Charlie called me one morning—4 a.m. his time; he’d always get to the barn at 4 a.m. I answered, thinking, What’s he doing calling me at this time? I said, ‘Hey Charlie, what you doing?’ He said, ‘Just waiting on the help.’ I knew he had something on his mind. Then he said, ‘You know what, this big black son of a bitch can run a little’—Charlie was a master of the understatement.’”

Brought along steadily by Whittingham, Sunday Silence romped to a 10-length win second time out at Hollywood Park in November 1988. And after running second in an allowance race, he returned at three to win his first two races: an allowance and the San Felipe Handicap.

While he was emerging as a potential Classic candidate on the West Coast, Ogden Phipps’ homebred Easy Goer was laying down the gauntlet in New York. A handsome red son of Alydar with regal Phipps bloodlines trained by Shug McGaughey, Easy Goer was evoking comparisons with Secretariat, capturing the Gr1 Cowdin and Champagne Stakes at two before running out the 13-length winner of the Gotham Stakes in a record time early on at three. To many observers, he appealed as the likely winner of the Kentucky Derby, if not the Triple Crown. Indeed, theirs would become an east-west rivalry that would enthral racegoers during the 1989 season.

The pair met for the first time in the Kentucky Derby. Sunday Silence, partnered by Pat Valenzuela, was fresh off an 11-length win in the Santa Anita Derby. Easy Goer, though, had won the Wood Memorial in impressive style and was therefore the crowd’s choice. Yet on a muddy track, Sunday Silence had the upper hand, winning with authority over an uncomfortable Easy Goer in second.

“Of all his races, the Kentucky Derby stands out,” says Hancock. “We’d been fortunate enough to win it with Gato Del Sol, and I’m a Kentuckian; so to win it again meant a lot. “It was an extremely cold day, it was spitting snow, and Sunday Silence was weaving all the way down the stretch. Yet he still won.”

With many feeling that the track had not played to Easy Goer’s strengths, he was fancied to turn the tables in the Preakness Stakes. However, once again, Sunday Silence emerged as the superior, albeit following an iconic, eye-balling stretch duel. Easy Goer did gain his revenge in the Belmont Stakes, making the most of the 1m4f distance and Belmont Park’s sweeping turns to win by eight lengths. The Triple Crown was gone, but Sunday Silence would later turn the tables in the Breeders’ Cup Classic, where his ability to deploy tactical speed at a crucial moment turned out to be a winning move against his longer-striding rival.

Charlie Whittingham and wife Peggy with jockey Pat Valenzuela after winning the 1989 Preakness Stakes

“The Breeders’ Cup just sealed everything—champion three-year-old and Horse of the Year,” says Hancock. “It was the great showdown. Chris McCarron was able to use him at just the right time and Easy Goer, with that long stride of his, was closing. It was a great race.” Crowned Horse of the Year, Sunday Silence underwent arthroscopic knee surgery which delayed his four-year-old return to June, when he won the Californian Stakes. A head second to Criminal Type in the Hollywood Gold Cup next time out brought the curtain down on a spectacular career.

No takers

Sunday Silence in the paddock at Belmont Park

Plans called for Sunday Silence to join his sire Halo at Stone Farm. A wonderful racehorse who danced every dance, there were grounds for thinking that Sunday Silence would be an asset to the Kentucky bloodstock landscape. But breeding racehorses even then also adhered to commercial restrictions, and as a cheap yearling with suspect hocks and an underwhelming female line, he did little to spark interest. This was in contrast to Easy Goer, who retired to much fanfare at Claiborne Farm.

“We tried to syndicate him and called people everywhere—Kentucky, England, France, and the answer was always the same,” says Hancock. “It became apparent very quickly that people wouldn’t use him.

“It was spread around the industry that he was a fluke, another Seabiscuit or Citation who could run but that would be no good at stud. It was said that he was crooked, which he wasn’t, and that he was sickle-hocked, which he was as a young horse but grew out of. He was an ugly duckling that grew into a swan.

“We had three people on the books to take shares and two that would send mares. Then I spoke to my brother Seth at Claiborne, and he had 40 contracts to send out for Easy Goer.

“At the same time, [U.S. President] Ronald Reagan changed the tax laws, and land became worth a lot less, as did shares in horses.”

The Yoshidas had already bought into the horse and suddenly, Hancock was left with little choice.

“At the same time, I got a call from a representative of Teruya Yoshida saying that Shadai would be interested in buying the whole horse,” he says. “They were offering $250,000 per share. I talked to a number of people about it—Bill Young at Overbrook Farm, Warner Jones; and they all said the same thing: that it was a no-brainer to sell.

“At the end of the day, I had two contracts and three shares sold. I owed money. I had to sell.

“The day he left, I loaded him up myself; and I don’t mind admitting that when that van went down the drive, I cried.”

He adds: “Basically, the Japanese outsmarted everybody.”

An immediate success

Out of a first crop of 67 foals, Sunday Silence sired 53 winners. A total of 22 of 36 starters won at two, led by champion two-year-old Fuji Kiseki, whose success in the Gr1 Asahi Hai Futurity set the scene for events to come. A tendon injury restricted Fuji Kiseki to just one further start when successful in a Gr2 the following year. Yet that failed to stop the Sunday Silence juggernaut.

Genuine and Tayasu Tsuyoshi ran first and second in the Japanese 2,000 Guineas and later dominated the Japanese Derby, with Tayasu Tsuyoshi turning the tables. Dance Partner also landed the Japanese Oaks. As such, Sunday Silence ended 1997 as Japan’s champion sire despite the presence of only two crops.

That first crop would also come to include Marvelous Sunday, who led home a one-two for his sire in the 1997 Gp 1 Takarazuka Kinen. In no time at all, Sunday Silence had sealed his place as a successor to earlier Shadai heavyweight Northern Taste.

“I believe Sunday Silence was a stallion that possessed the potential to be very successful anywhere in the world,” reflects Teruya Yoshida. “We were just lucky to be able to introduce him to Japan as a stallion.

“He changed the Japanese breeding industry completely, especially as he sired successful sons as race horses and stallions. Those sons have again sired successful grandsons.

“It is extraordinary that one stallion continued to produce good quality stallions over three generations. Today, it is said that approximately 60-70% of the Japanese broodmares have Sunday Silence in their female lines.”

Another top two-year-old, Bubble Gum Fellow, emerged from his second crop alongside a second 2,000 Guineas winner in Ishino Sunday and St Leger hero Dance In The Dark. Stay Gold, Sunday Silence’s first real international performer of note by virtue of his wins in the Hong Kong Vase and Dubai Sheema Classic, followed in his third while another Japanese Derby winner followed in his fourth in Special Week, also successful in the Japan Cup.

And so it continued. In all, his stud career came to consist of six Japanese Derby winners (Tayasu Tsuyoshi, Special Week, Admire Vega, Agnes Flight, Neo Universe and Deep Impact), seven 2,000 Guineas winners (Genuine, Ishino Sunday, Air Shakur, Agnes Tachyon, Neo Universe, Daiwa Major and Deep Impact), four St Leger winners (Dance In The Dark, Air Shakur, Manhattan Cafe and Deep Impact) and three 1,000 Guineas winners (Cherry Grace, Still In Love and Dance In The Mood). While a number of those good Sunday Silence runners became fan favourites, there’s no doubt that the best arrived posthumously in the champion Deep Impact. A member of his penultimate crop and out of the Epsom Oaks runner-up Wind In Her Hair, Deep Impact swept the 2005 Japanese Triple Crown and another four Gp 1 races, including the Japan Cup and Arima Kinen, at four. One of Japan’s most popular horses in history, he also ran third in the 2007 Arc.

Fittingly, Deep Impact was also quick to fill the void left at Shadai by his sire’s death from laminitis in 2002.

International acclaim

The Japanese bloodstock industry during the mid-1990s was still relatively isolated from the rest of the world, better known certainly in Europe as the destination for a slew of Epsom Derby winners. Sunday Silence would change all that.

As word of his dominance at stud grew, so did international interest. Teruya Yoshida was swift to capitalise. In 1998, he sent his homebred Sunday Silence filly, Sunday Picnic, to be trained in Chantilly by André Fabre. It was a successful endeavour as the filly won the Prix Cleopatre and ran fourth to Ramruma in the Oaks. By that stage, Shadai had also entered into a partnership with John Messara of Arrowfield Stud with the principal idea of breeding mares to Sunday Silence on southern hemisphere time. Again, the move proved to be a success. Out of a limited pool of Australian-bred runners, Sunday Silence threw the 2003 AJC Oaks heroine Sunday Joy, who would go on to produce eight-time Gp 1 winner More Joyous and Listed winner Keep The Faith, subsequently a Gp 1 sire.

Sheikh Mohammed also joined the fray, notably by sending a relation to Miesque, the Woodman mare Wood Vine, to Sunday Silence in 1998. The resulting foal, the Irish-bred Silent Honor, was trained by David Loder to win the 2001 Cherry Hinton Stakes at Newmarket. Silent Honor was the opening chapter of a successful association for the Sheikh with Sunday Silence that also came to include Godolphin’s 1,000 Guineas runner-up Sundrop, a JRHA Select Foal Sale purchase, and homebred Gp 3 winner Layman. Layman was foaled in the same 2002 crop as the Wertheimer’s high-class miler Silent Name. Initially trained in France by Criquette Head-Maarek, Silent Name was a dual Listed winner before heading to the U.S., where he won the Gr 2 Commonwealth Breeders’ Cup for Gary Mandella. Similarly, patronage of Sunday Silence also reaped rewards for the Niarchos family as the sire of their influential producer Sun Is Up, subsequently the dam of their top miler Karakontie. At the same time, several Japanese-trained horses were advertising the stallion to good effect on a global scale, notably Zenno Rob Roy, who ran a close second in the 2005 Juddmonte International, and Heart’s Cry, who was third in the King George a year later.

Sunday Silence at Shadai Stallion Station, Japan

Sire of sires

Meanwhile, it was becoming very apparent just how effective Sunday Silence was becoming as a sire of sires. Shadai was initially home to plenty of them, including the short-lived Agnes Tachyon, who left behind a real star in champion Daiwa Scarlet, and Fuji Kiseki, the sire of champions Kinshasa No Kiseki and Sun Classique. Stay Gold’s successful stud career was led by the household names Orfevre, who ran placed in two Arcs and is now a proven Gp 1 stallion for Shadai, and Gold Ship. Japan Dirt Derby winner Gold Allure became a leading dirt sire—his record led by champions Copano Rickey, Espoir City and Gold Dream. Manhattan Café is the sire of five Gp 1 winners. As for Special Week, he sired champion Buena Vista and Gr 1 winner Cesario, now regarded as something of a blue hen.

Those sons still in production are entering the twilight years of their stud career. The death of Deep Impact in July 2019 robbed Japan of its international heavyweight stallion. Similarly, the announcement that fellow Shadai stallion Heart’s Cry would be retired ahead of the 2021 season removed a very able substitute. Often in the shadow of Deep Impact, Heart’s Cry evolved into an exceptional sire for whom an international profile consisted of the British Gp 1 winner Deirdre, American Gr 1 winner Yoshida and Japanese champion Lys Gracieux, the 2019 Cox Plate heroine.

However, another Shadai stallion, Daiwa Major, remains in service at the age of 21. Well regarded as a fine source of two-year-olds and milers, he earned international recognition in 2019 as the sire of Hong Kong Mile winner Admire Mars, now also a Shadai stallion. Neo Universe, best known as the sire of Dubai World Cup winner Victoire Pisa, and Zenno Rob Roy are also proven Gp 1 sires as is Deep Impact’s brother Black Tide, the sire of champion Kitasan Black. The latter is also now based at Shadai and the sire of Gp 2 winner Equinox out of his first crop of two-year-olds.

As such, even without Deep Impact, Sunday Silence’s influence as a sire of sires would have been immense. Deep Impact, however, took matters to another level. To date, he is the sire of 53 Gp 1 or Gr 1 winners. As far as Japan is concerned, they cover the spectrum, ranging from Horse of the Year Gentildonna to the 2020 Triple Crown hero Contrail—one of seven Japanese Derby winners by the stallion—and a host of top two-year-olds. Significantly, Deep Impact had been exposed to an international racing audience when third past the post in the 2007 Arc and that played out in a healthy level of outside support when he retired to Shadai for the 2008 season.

For the Wildenstein family, that reaped major rewards in the form of their Poule d’Essai des Pouliches heroine Beauty Parlour, her Listed-winning brother Barocci and French Gp 3 winner Aquamarine. That early success, as well as his growing reputation in Japan, helped to pique the attention of Coolmore. The Irish powerhouse began sending mares in 2013 and were swiftly rewarded by the 2,000 Guineas winner Saxon Warrior, now part of the Coolmore roster in Ireland, and the Gp 1-placed September out of a limited pool of foals. The Prix de Diane heroine Fancy Blue followed in 2020.

Yet better was to come in 2021 in the top three-year-old Snowfall. Bred by Coolmore in Japan out of Best In The World, a high-class Galileo sister to Found, the filly made giant strides from two to three for Aidan O’Brien to sweep the Epsom, Irish and Yorkshire Oaks. Her wide-margin victories in those summer highlights placed Snowfall in rarefied company while further illustrating just how well Deep Impact clicked with some of those high-flying Galileo mares. The same cross has one final chance to shine through the stallion’s last, small crop which includes two-year-olds out of the top Ballydoyle race mares Rhododendron, Minding and Hydrangea. Aidan O’Brien’s yard also houses a brother to Saxon Warrior who is out of the top two-year-old Maybe. Similarly, the Niarchos family, who patronised him from the outset, bred Le Prix du Jockey Club hero Study Of Man, whose Classic campaign in 2018 coincided with that of Saxon Warrior’s. Indeed, Deep Impact was at the height of his international powers when succumbing to a neck injury at the age of 17 in the summer of 2019.

Global exposure

While Deep Impact would build on the global foundations laid by his sire, there was a determination during the intervening years between Sunday Silence’s death and Deep Impact’s own success to expose the blood to a global audience. Chief among them was French-based agent Patrick Barbe, who sourced a number of sons to stand in France, and Frank Stronach, who purchased Silent Name to stand at his Adena Springs Farm. Barbe was the force behind importing an eclectic group of Sunday Silence horses to stand at Haras de Lonray during the mid-2000s. They were invariably priced towards the lower end of the market, yet Barbe was rewarded for his foresight, in particular through the addition of Divine Light, whose first French crop yielded the 1000 Guineas and Cheveley Park Stakes heroine Natagora.

“I have worked with Shadai for over 35 years,” he says, “and I thought it would be interesting to bring the Sunday Silence bloodline to Europe—it hadn’t been tried very much at the time. It can be difficult to educate breeders about different blood, but people had already had slight exposure to Sunday Silence, so it wasn’t too bad.

“Rosen Kavalier was one of the first we brought over. Then we imported Divine Light. Teruya Yoshida had mentioned to me that he thought he was going to do well at stud, as he had been an extremely good sprinter. But he covered only nine mares in his first season in Japan. So we brought him to France, and in his first crop, he sired Natagora.”

As fate would have it, Natagora’s true ability came to light in the months following his sale to the Jockey Club of Turkey. Divine Light left behind just under 100 foals from his time in France and went on to enjoy further success in Turkey as the sire of champion My Dear Son.

“Divine Light was a good-looking horse,” says Barbe. “He was out of a Northern Taste mare and was compact—very similar to Northern Dancer.” He adds: “Sunday Silence was a phenomenal sire, but he also had a pedigree that was similar to Northern Dancer. I feel that was the reason that he did very well with Northern Taste, who was obviously also inbred to Lady Angela [the dam of Nearctic] himself.”

Divine Light wasn’t the only success story out of the French Sunday Silence experiment. While Rosen Kavalier was compromised by fertility problems, Gp 3 winner Great Journey sired several smart runners, while Gp 2 winner Agnes Kamikaze left behind a clutch of winners.

“Great Journey was a very good racehorse and became a consistent sire,” says Barbe. “He did well as the sire of Max Dynamite—a very good stayer—and Soleil d’Octobre, who won two Listed races.”

Today, the sole son of Sunday Silence available in either Europe or North America is Silent Name. Now 20 years old, he has found his niche within the Canadian market as a source of durable, talented runners—in a nutshell, what we have come to expect from the sireline.

Silent Name

Despite never standing for more than C$10,000, Canada’s three-time champion sire is responsible for over 30 black-type winners, making him the nation’s leading sire of a lifetime of stakes winners. They include champion sprinter Summer Sunday, Brazilian Gp 1 winner Jaspion Silent and last year’s Gp 1 Highlander Stakes winner Silent Poet. So although entering the veteran stage of his stud career, momentum behind the stallion continues to remain robust at a fee of C$7,500, as Adena Springs North manager Dermot Carty explains.

“Silent Name started out with us in Kentucky, but in 2008, we decided to bring him to Canada along with Sligo Bay,” he says. “He got three good books off the bat. At the same time, he shuttled to Brazil, and then just as his first Kentucky crop hit, he was sent to New York [where he spent two seasons with McMahon of Saratoga Thoroughbreds].

“I pleaded to bring him back to Canada. People were starting to buy them, they were liking them, and the smaller trainers were doing well with them.

“He’s a really good-looking horse—strong, a little bit sickle-hocked but with good bone. And he’s a tough horse, as tough as they go.

“When we bought him, he was really the only big horse in the pedigree, but it’s a typical Wertheimer family, and it’s improved a lot since then.” In fact, Silent Name is a half-brother to Galiway—a current rags-to-riches story of the French scene whose early crops include last year’s Qipco British Champions Stakes winner Sealiway.

“He’s out of a Danehill mare who is out of a Blushing Groom mare who is out of a Raja Baba mare,” adds Carty. “They’re all big influences.

“A lot of them can run on Polytrack, but they also excel on turf.

“He was the leading sire in Canada for three years straight; the last horse to do that was Bold Executive. Frank has sent a pile of mares to him in recent years and done very well. He’s going to get you a tough horse—people who like to race like him.”

Walmac Farm in Kentucky also made an early foray into Sunday Silence blood with the acquisition of Hong Kong Gp 1 winner Hat Trick in 2008. Latterly based at Gainesway Farm, Hat Trick threw top French two-year-old Dabirsim in his first crop and in turn, that horse sired Albany Stakes winner Different League out of his own debut crop. Noted for siring stock that comes to hand quickly, Dabirsim remains popular at Haras de Grandcamp in Normandy, also home to Deep Impact’s talented son Martinborough. Hat Trick died in 2020 and today, Kentucky representation of the Sunday Silence line relies on the young WinStar stallion Yoshida. A son of Heart’s Cry, he was sourced out of the JRHA Select Sale and went on to land the 2018 Woodward Stakes. He was popular in his first season at stud in 2020, covering 145 mares; and his first foals sold for up to $150,000 at the Kentucky winter breeding stock sales.

Fruitful experiment

Meanwhile, the retirements of Saxon Warrior to Coolmore in Ireland and Study Of Man to Lanwades Stud in Newmarket provide European breeders with quality access to Deep Impact blood. Saxon Warrior’s first crop sold for up to €540,000 as yearlings last year and are now in the yards of Aidan O’Brien, William Haggas and Mark Johnston among others.

The first crop of Study Of Man are yearlings of 2022. As would be expected from a Niarchos homebred who stands at Lanwades Stud, he is being well supported by his powerful connections, as highlighted by the stud’s owner Kirsten Rausing in a piece with The Owner Breeder magazine last June.

STUDY OF MAN

“I have sent him all my best mares,” she said. “I have nine from the Alruccaba family and a number of others from different families, including a very nice filly out of [Gp 1 winner] Lady Jane Digby and others out of Cubanita [a dual Gp 3 winner] and Leaderene [dam of current Australian stakes winner Le Don De Vie].

“It’s early days, but he looks to be a true-breeding bay. I would also say that a few of them look to have a bit of Sunday Silence about them.”

From the Niarchos’ point of view, utilising Study Of Man allows them to tap into inbreeding to his granddam, the family’s excellent miler and blue hen Miesque. Hers is one of the finest families worldwide and it is indicative of the high regard in which the Niarchos held Sunday Silence that they chose to support him with several members of the family.

“The relationship between the Niarchos family and Shadai dates back to when they bought Hector Protector from us,” recalls Alan Cooper, racing manager to the Niarchos family. “We had breeding rights in the horse, and we said, well we better send some mares to Japan and use him, which worked out well as we went on to breed [champion] Shiva.

“And that led us to using Sunday Silence. The Sunday Silence adventure was very fruitful. It was lovely to get some fillies by him, and we’re still benefitting today from them.”

Among the mares sent to Sunday Silence was Miesque’s Listed-winning daughter Moon Is Up. The resulting foal, Sun Is Up, never ran but went on to throw Karakontie, whose three Gp 1 victories included the Poule d’Essai des Poulains and Breeders’ Cup Mile. Study Of Man is out of Miesque’s Storm Cat daughter Second Happiness while another mare, Metaphor, foaled the Listed-placed Celestial Lagoon, in turn the dam of Dante Stakes runner-up Highest Ground.

“We also obviously had a lot of success breeding from Deep Impact through Study Of Man,” says Cooper. “We also have a filly named Harajuku, who won the Prix Cleopatre last year. Another Deep Impact that we bred, Dowsing, is now at stud in Indiana.

“It’s been a very good experience breeding in Japan. The Sunday Silence line seems to have a bit of character, but I think as with anything to do with Halo, if they’re good, they’re very, very good.”

The Niarchos family are also in the privileged position of owning a two-year-old from the final, small crop of Deep Impact. The filly in question is out of the Listed-placed Malicieuse, a Galileo half-sister to Arc hero Bago.

In Kentucky, meanwhile, the Niarchos family have also thrown their weight behind Karakontie at Gainesway Farm in Kentucky. The son of Bernstein is emerging as one of the most versatile stallions in North America, thanks to a clutch of early stakes winners that range from Princess Grace, a Graded stakes winner on both turf and dirt, to Del Mar Derby winner None Above The Law. Interestingly, Princess Grace is the product of a Silent Name mare, meaning that she is inbred to Sunday Silence. Indeed, she is the first stakes winner outside of Japan to carry his inbreeding.

Too much of a good thing?

Can there be too much of a good thing? In Sunday Silence, the Japanese racing scene has been dominated to such a degree—through both his sons and daughters—that outcrosses aren’t always easily available. And when such an animal does retire to stud in Japan, quite often their success is a reflection of their ability to cross effectively with Sunday Silence-line mares—the likes of Lord Kanaloa and Harbinger being notable examples.

In addition, successful inbreeding to Sunday Silence has taken time to gain momentum. However, in recent years, the tide has started to change.

Aside from Princess Grace, one recent major flag bearer has been the Japanese Fillies Triple Crown heroine Daring Tact. Efforia, who defeated Contrail in last year’s Gp 1 Tenno Sho (Autumn), is another fine advert among a group of 19 stakes winners from a pool of close to 4,000 named foals.

One of the greatest

Sunday Silence might be receding in pedigrees, but his influence has never been stronger. Many of the line remain easily distinguishable with their dark coat and rangy stature; for the most part, they are hardy runners with a physical and mental toughness to them.

“All these horses—they ran forever,” says Barbe. “They’re tough, train on and they’re sound. Whatever their level, they are consistent horses with a longevity to them.”

Granted, those descendants of Sunday Silence now coming through at stud in Japan aren’t always helped by having to compete with each other. But at the same time, the omens remain good, particularly in relation to Deep Impact’s own legacy as a sire of sires, which already includes the successful Shadai sires Kizuna and Real Impact. The latter became the first son of his sire to be represented by a Gp 1 winner when Lauda Sion won the 2020 NHK Mile Cup while Kizuna ends 2021 a top-four Japanese stallion, thanks to the exploits of the recent Gp 1 Queen Elizabeth II Cup winner Akai Ito and the Prix Foy hero Deep Bond.

Another young son, Silver State, is Japan’s second leading first-crop sire of 2021; only a minor four-time winner himself, he has already exceeded expectations by throwing the Gp 1-placed Water Navillera in his first crop.

The presence of Saxon Warrior and Study Of Man in Europe and other Gp 1 performers such as Satono Aladdin, Staphanos and Tosen Stardom in Australasia fuels the idea that this branch of the line is only going to become more powerful on a global scale. In short, international respect for the sireline is also at an all time high.

“Thanks to Sunday Silence, the Japanese racehorses earn respect from horsemen around the world today,” says Yoshida. “In return, breeders tend to find good broodmares to send to good stallions—Japanese breeders today buy a lot of good broodmares in the international markets.

“This enables Japanese breeding to keep developing. So you can imagine how strong Sunday’s impact is to our industry.”

Water treadmills – what can they offer our racehorses?

By Carolyne Tranquille, Dr Kathryn Nankervis & Dr Rachel Murray

Issue 71 of European Trainer (January - March 2021) included an article titled “Understanding hydrotherapy and the benefits of water-based conditioning.” In this issue, we examine the best practices for using water treadmills as part of a training programme.

Water treadmill (WT) exercise is increasingly being used as a routine part of the training of sport horses and now racehorses. However, the research detailing their effects on our equine athletes has only emerged in the last 5-10 years. A WT allows the trainer to provide a pre-determined, very precisely controlled piece of work for the horse. With the addition of water, we can then overlay this most basic piece of work with additional tools due to the properties of water itself: drag and buoyancy. The combined effect of these two forces can yield movement patterns for our horses that are beneficial in supporting training programmes. The million-dollar question then is, how exactly do you select depth and speed of belt to achieve what you want within a training programme?

Contrary to popular belief, heart rates of horses walking in water are not necessarily increased as water levels rise, with horses merely adapting their gait pattern to accommodate for increased drag. Indeed, WT exercise never elicits heart rates of over 120-140 beats/min nor does it elevate blood lactate levels, even when carrying out what might be considered to be the ‘hardest’ type of exercise which is trotting in high water. So, the benefits of this modality clearly aren’t in its ability to act as a substitute for fast work; its benefits are in the responses it can bring about in the horses’ movement pattern and the consequent muscle adaptation that can be provided when horses use it on a regular basis.

In 2019, an international equine hydrotherapy working group produced a WT user guideline document. The following sections highlight the recommendations from the group to obtain the best out of a WT exercise session for our racehorses.

General best practice in water treadmill exercise

Follow manufacturer guidelines for correct machine operation, water care and cleaning of the machine; and seek help from an experienced user to supplement the initial training received by the manufacturer.

Handlers should wear personal protective equipment (e.g., hard hat and gloves) during a WT session, and two handlers should be present.

Horse loading and unloading procedures should be specific to the make and model of the machine, and the environment in which the treadmill is located, with procedures devised to avoid the handlers being directly in front or behind the horse. Loading and unloading of naïve horses seems to present the greatest risk to the handlers.

To help keep the water clean, the horse should be brushed and/or hosed off to remove superficial dirt, the feet are picked out and the tail wrapped.

WT exercise should be avoided for horses with any skin lesions, cuts or abrasions that might be below the water level or for a horse that had received a distal limb joint injection within four days.

If the horse is shod, the shoes should be secure. Shoes with road nails could damage the belt, and large extensions which may affect the flight of the foot in water should be avoided.

Horses can be worked on a WT in a headcollar, chifney or bridle, provided the natural movement of the head and neck are not restricted.

Leg protections should be avoided.

Once the session is complete, the horse should be hosed and dried off, especially the feet, to avoid foot problems.

Introducing horses to the exercise

Horses habituate to WT exercise more readily if they are given several short sessions (up to 15 minutes) on consecutive days.

Sufficient time should be allocated to avoid rushing the horse and ensuring he has a positive experience. The horse can be prepared for the belt moving by asking him to step back and forth a few times; then start the belt as the horse takes a step forward.

The water depth should be increased with each session, provided the horse remains relaxed. Water should be kept at fetlock depth during the first session.

If a light amount of sedation is going to be used for the first session, this should only be done under the direction of a veterinary surgeon.

Horses are considered habituated once a relaxed and rhythmical gait is reached.

Correct posture and movement patterns during water treadmill exercise

What is the correct posture, and how should a horse move during WT exercise?

The horse should be in line with the treadmill and not leaning or rolling from side-to-side.

The horse should be able to move its head, neck and forelimbs without being obstructed by the front of the treadmill.

The horse should be able to maintain position in the middle of the belt without falling to the back.

The horse’s face should be just in front of the vertical.

The head and neck should be largely still.

The horse should have a rounded lumbar spine.

The horse should be ‘pushing’ from the hindquarters.

A regular rhythm to the footfalls should be heard.

What should a horse not look like and not move during WT exercise?

The horse’s face should not approach the horizontal.

There should not be excessive movement of the head and neck (the chicken walk).

There should not be extension of the thoracic and lumbar spine.

The horse should not ‘pull’ from the forehand.

An irregular rhythm to the footfalls should not be heard during a WT session.

Factors influencing selection of speed, water depth and duration of exercise

Speed should decrease as water depth increases.

Walking more slowly than overland is recommended.

Belt speed should be horse-specific, and a suitable speed for the horse should be found before water is introduced into the chamber.

The horse should work in a correct posture (as discussed above).

The benefits of WT exercise can be achieved without trotting. To ensure safety of horse and handler, horses should only trot in the WT once they are confidently walking at various water heights.

Water depth should be training or rehabilitation goal-specific.

The best combination of speed and water depth will vary between horses and should be judged according to the individual horse’s response.

Individual horse fitness, stride length, joint range of movement and capability may change during an individual session or over multiple sessions.

It is important to monitor movement patterns closely and to observe the horse throughout the session and how movement alters in response to changes in speed or water depth and whether these changes are indicative of fatigue. This is relevant at any given water depth.

Benefits of water treadmill exercise for racehorses

Reduction of impact shock

Increased muscle development of the hindquarters

Increased joint range of motion of the limbs and the back

Increased hindlimb range of motion

Controlled straight line exercise without the added weight of the rider

Improved aerobic capacity

Conclusions

This article summaries the best practice for WT use based on the recommendations of the Equine Hydrotherapy Working Group and the Water Treadmill User Guidelines. WT exercise has many potential benefits if the correct protocols are used, and if the horse is in a correct posture and moving optimally when on the WT. Monitoring horse posture and movement patterns throughout the session are essential to assess whether or not the horse is working optimally. The final published guidelines can be found here: tinyurl.com/water-treadmills

International Horse Movement - under the spotlight

At the annual European Horse Network / MEP’s Horse Group Conference in Brussels

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen opened the conference held in Brussels 16 November 2021 with a message of support. Paull Khan, secretary-general of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation, then spoke on international horse movement and, in specific, in the context of the three political and legal factors of Brexit, the EU Animal Health Law and the review of Animal Welfare regulations, particularly the Transport Regulation.

Khan looked at things primarily through a “thoroughbred lens,” but also included other relevant equine sectors. Explaining why horse movement is so important to our sector, Khan pointed out, “Horse racing is not only a serious sport, it is a serious business. We estimated last year that the economic impact of racing in Europe is some €23bn per annum, and the sector directly employs over 100,000 people, mainly in rural areas.

“Horse racing is widespread across the EU. Seventeen of our European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation members are EU member states—the same for our sister organisation, the European Trotting Union; and movement of thoroughbreds is central to this industry.”

While other agricultural animals will typically only move internationally once, if at all, usually for slaughter, horses, particularly racehorses and sports horses, frequently move between countries for reasons other than slaughter. Khan stressed the importance of repeating this to those outside our sector: “As legislators may have in their minds ‘travel for slaughter,’ when they think of international travel of horses and other animals.” Almost 90,000 equines in a normal year travel internationally within, or to and from, the EU; and it is estimated that nearly 60% of these movements are not for slaughter.

“For thoroughbreds, it starts at the very beginning—at their conception,” said Khan. “So the movement of mares to visit stallions is essential. And it is vital, for the improvement of the breed and in order that Europe retains its competitive pre-eminence in this area, that mare owners are able to select from a broad panel of stallions, which may be based in other countries. There are growing concerns in the Stud Book community about inbreeding. Limiting the geographical footprint is an obvious way to restrict that gene pool.”

He went on to point out that during the horse’s racing career, the better it is, the more likely it will travel internationally to contest the best races. “Again, this process is critical to the improvement of the breed. The performances of a racehorse within any given country are only truly validated when that horse is tested by racing the best in other countries.”

Moving on to the issues posed by Brexit, Khan reminded us that the three countries with the largest thoroughbred industries—France, Ireland and Great Britain—had relied on the former Tripartite Agreement to allow for largely free and unrestricted travel within this bloc. There were over 26,000 international movements of thoroughbreds annually between these three nations alone. Now, movement between Great Britain and EU countries requires blood tests, the involvement of official vets for health certification, further health-check on entry, pre-notification of the movement, both outbound and return, Customs paperwork (four sets for a return trip) and the payment of value added tax. “The burden in terms of cost, time and hassle of moving a horse has risen starkly,” Khan illustrated.

“There are also welfare issues here,” he continued. “World Horse Welfare tell me that the requirements are impacting compliant traffic but not non-compliant traffic. We have heard of people choosing to send horses from France, destined for Britain by the long sea route to Ireland, then traveling up to Northern Ireland and finally across to mainland Britain, all in order to avoid all this. Clearly not in the horses’ welfare interests. And we know of delays of several hours at Border Control Posts (BCPs) and of horses—most recently a nine-month-old foal, which was sent back to the UK on its own because of a technicality of the paperwork.”

What is frustrating is that so much of this is unnecessary. Khan said, “Taking the health certification requirements first, they are not serving to solve any existing bio-security problem—there were no issues arising out of the movement of horses to and from the UK throughout the 50 years before Brexit. But putting that aside, the requirement to complete lengthy paperwork is unnecessary, given the existence of a digital alternative.

“And secondly, in respect of the VAT, the vast majority of racing and sport horse movements are return journeys—the horse travels to compete, or breed, and then returns. But even though VAT is not ultimately payable in the case of temporary movements, there is the need for connections of the horse to pay the VAT, or put up security against its value and then reclaim it. This is time consuming, not only for the connections of the horses but also for the revenue officials collecting the money who then have to spend time in repaying that money to the connections when the horse has gone home. Repayments are reportedly typically taking five months from some countries. This is a pointless waste of time and effort for horsemen and officials alike.”

What effect has all this had on movement numbers to and from Great Britain? “It’s very difficult, of course, to split the effect of COVID from that of Brexit; but what we can see very clearly is that, in combination, Brexit and COVID have had a downward impact on thoroughbred movements,” Khan reflected.

“It is clear that racing movements, i.e. international runners, suffered badly in the first year of COVID, roughly halving from 2019, whether between Britain and the EU or the rest of the world. It is true that, since Brexit, rather than seeing a further deterioration, we have witnessed a recovery. Racing movements this year, despite Brexit, have been higher than in 2020—24% higher to and from the EU, and 59% higher to and from the rest of the world. But, while we must be optimistic that the worst effects of COVID are behind us, we cannot be so confident about Brexit. We just don’t know how owners’ and breeders’ behaviour will be modified in future years by the stark reality of their experience in this, ‘Year One’. Now that they know what the final bill added up to and how long it took for them to receive their VAT repayments, it is not unreasonable to surmise that they may choose not to repeat the exercise in the future.”

Even given this year’s recovery, he noted that international runners between Britain and the EU have fallen by one-third against 2019 levels, and those with the rest of the world are down by 13%.

“This means that EU owners and trainers have had fewer opportunities to test their horses against those in Britain, and races on both sides of the water have been weakened, both in their appeal to the public and as international testing grounds.

“This could have a long-term damaging effect in an area where Europe leads the world. No fewer than 38 of the world’s top 100 races are run in Europe—more than Asia which has 23, Australasia 26 and the Americas 13. I mentioned the economic impact of European horse racing over €23bn per annum; much of this is linked to the quality of the races that are run here.”

“Tracing a very different pattern have been non-racing movements (excluding Ireland), which were far more resilient to COVID than were racing movements but which have suffered post-Brexit in a way that racing movements have not. Movements for breeding and other purposes outnumber racing movements by around six to one.

“Looking at movements between Britain and Continental EU—we don’t have these figures for Ireland because Britain and Ireland share a common Stud Book—we see they have more than halved, from 4,283 to 1,964. An indication of the ‘Brexit effect’ can be inferred from the fact that movements between Britain and the rest of the world only reduced by 13%, despite COVID.

“Non-racing movements to and from Ireland have held up remarkably well, being within 4% of 2019 levels. Overall, thoroughbred journeys between Britain and the EU are one-third down on two years ago.

“This isn’t just affecting racing. The European Equestrian Federation have told me that they have seen reduced numbers, both of British competitors at European events and Europeans travelling to Britain. And, taking the perspective of Ireland, we see a very similar picture. Non-racing movement of thoroughbreds between Ireland and the rest of the EU has fallen from 3,951 to 2,407—a 39% fall.

“Overall movements to and from Ireland would appear to be down by one-quarter—less, therefore, than the one-third fall to and from Britain. As in Britain, racing movements have shown a recovery this year, whereas non-racing movements, except those too and from Britain which have been static, have continued to fall.”

Animal Health Law was the next major issue to be examined in detail by Khan, although as he pointed out, the AHL has only applied since April; and member states are at different stages of their practical implementation. “In brief, it is too soon to gauge its impact on horse movement,” he warned.

“The new requirements for the registration of operators and establishments, the registration of the place where a horse is habitually kept, the need to record all arrivals and departures, etc., will create additional work. And it could be argued that the problems these measures are being brought in to address are largely absent in the race and sport horse sectors; and they come at a time when the equine sector is already reeling from the impact of COVID.

“What I would say, however, cautiously, is that, from the soundings I have been making, my impression is that, at least in our sector, there are no widespread concerns over the impact of this new legislation per se on horse movements.”