Racing in the Channel Islands

Guernsey Race Club L'Ancresse meeting 2019. (C. Martin Gray)

By Dr Paull Khan

In a golden spell of several months earlier this jumps season, the exploits of a 12-year-old handicap hurdler named Kansas City Chief and his 21-year-old 7-lb claiming amateur rider Victoria Malzard seemed to be on British television screens almost every Saturday afternoon, ensuring that racing in Jersey (where Malzard is based and the horse is sometimes trained by her mother, Alyson) received perhaps unprecedented publicity. Channel Islands racing does not normally figure high in the consciousness of racefans in Britain—still less, doubtless, in the rest of Europe.

So, what is racing like on these small islands, lying close to the French coast, enjoying a complicated relationship with the United Kingdom? (The Channel Islands—not being part of the UK—were never part of the European Union, so ‘Chexit’ was never a thing.)

There are two Channel Islands racetracks: the CoinShares Les Landes on Jersey and L’Ancresse on Guernsey. The former traditionally stages some nine fixtures annually, bookended by Easter Monday and the late-August bank holiday. It is a left-handed turf track of one mile’s circumference. The usual pattern is to kick off with a hurdle race. The temporary hurdles are then moved off the track, clearing the way for four races on the level. Last year, most races were run for a £2,800 prize fund, with the feature race of the day worth up to £4,750.

L'Ancresse is a temporary track, having to be laboriously set up and taken down each year. Like Les Landes, a turf course, it is by contrast right-handed, with a circumference of nine furlongs. In recent pre-pandemic years, the big race of the day has been the Ravencroft Channel Islands Handicap, which is over around six furlongs and billed as the richest race on either island, with a prize fund of £5,000.

L’Ancresse normally races on but a single day each year—on the early-May bank holiday. But these are not normal times. There has been no racing on Guernsey since 2019, and 2022 will be the third blank year in a row. What COVID-19 began, the island’s wildlife has conspired to continue. Trevor Gallienne, Guernsey Race Club President, picks up the story: “We’ve had an invasion of rabbits over the past two years and also massive crow damage to the grass.”

No Guernsey-based trainer survives, and so the island is perhaps unique in the world in staging a race meeting; but having no domestic horses in training—a situation Gallienne himself describes as a ‘bizarre business model’. Therefore, even when trainers based in Jersey, or in the UK or France, have been tempted to enter, the meeting remains entirely dependent on the vagaries of the weather.

“There are obviously wave restrictions on the boats bringing the horses over and, a few years ago, none of the horses were able to travel and we had to call the meeting off.” Nothing, if not resourceful, however, the Club averted complete financial disaster through persuading those booked into the hospitality marquee to attend a race night in a hotel, instead. Despite all this, there is a resolve to restart, in 2023, the tradition of racing on the island that began over 120 years ago.

A 30-kilometre hop southwest brings you to Jersey’s Les Landes, which has endured similarly turbulent times since COVID-19 struck. “2019 was a very successful year over here”, explains Bunny Roberts, Jersey Race Club President. “And then in 2020, we were hit slam-bang and we had a completely blank year, during which we were still having to pay wages and maintain the course. By 2021, we were in a dire position—the reserves were running out.”

Thankfully, the story takes a happier turn, and in 2022 the race club’s finances are healthy again, and a full and normal fixture list is planned. “We managed to pull it round. We created a very good committee, our patrons stepped up to the plate in a big way, and we are fortunate in that so much of what is done is done voluntarily by people who love the sport. Last year, despite government restrictions at each meeting, we managed to run eight of our nine meetings, albeit later than usual. We were unbelievably lucky with the weather. The crowds supported us, despite the public bar being closed. We allowed people to bring in picnics. For this year, sponsorship is buoyant, and we have eleven £5,000 races, with the minimum now up to £3,000.”

An absence of income from off-track betting or media rights means that the course’s survival depends on creative marketing, with multiple sponsorship offerings, merchandising and a golf day all critical to the financial mix. Roberts takes an upbeat view of the future for Les Landes generally and more specifically of landing the holy grail of media rights income in the future. “It will depend on field size and field quality. Last year the fields were great and the quality of horses in training on the island has improved; we have many rated between 65 and 80. I honestly believe we will get there.”

It is undeniable that, despite relatively modest prize money, there is a healthy interest amongst British-based trainers in taking horses to the islands. In the last pre-pandemic year of 2019, no fewer than nine made the voyage over to Jersey: Neil Mulholland, Phil McEntee, Eve Johnson Houghton, Michael Appleby, John O’Neill, Richard Guest, Colin Heard, Victor Dartnall and Natalie Lloyd-Beavis. Mulholland was well clear as the most successful, with 13 wins of around £30,000, at an impressive strike rate of over 50%.

In addition, four Brits: David Evans, Michael Appleby, Natalie Lloyd-Beavis and Brian Barr sent runners to Guernsey and collectively made a clean sweep on the day, with Evans picking up three of the day’s races, and Appleby the other two.

What, then, is the appeal to these trainers and their owners? “For us it started about eight years ago”, explains Mulholland. “Jim Jamouneau (of Guernsey Race Club) came to the yard one day and said, ‘Why don’t you come to Guernsey?’ We had an owner, Mike Burbage (director of Dajam Ltd), who liked a weekend away, liked the fun, and going to Guernsey for the weekend appealed to him. On our first ever trip, we finished first and second. But every single year we’ve been to the Channel Isles, we’ve had at least one winner, which has made the trip worthwhile. We’ve been Champion Trainer twice. It’s a good weekend away, we enjoy it, and it’s pretty simple really. We go either from Poole, which is the fast boat, or Southampton. We did have to miss one meeting last year because of the weather.”

What kind of horse is suited to Les Landes? “You need something that travels and is well-balanced”, answers Mulholland. The view is supported by local trainer James Moon, whose yard is far enough from Les Landes that he does not use the training track which runs inside the main track, but rather has his own gallops designed to mimic Les Landes’ unique features. “You have to have an intelligent, balanced and tough horse to win round Jersey, with its undulating surface, stiff finish, hard back stretch with a drop-down and both tight and sweeping bends. It’s great for educating horses both young and old.” Another USP is that there are no starting stalls, with all races being started by flag, making it of particular interest to trainers with recalcitrant starters.

While Brexit has not been relevant to links with Britain, it has affected travel to and from mainland Europe and, for those like the Francophile Moon, it has not been welcome. “It’s totally ruined things”, is Moon’s blunt assessment. “It’s made it massively expensive and all the unnecessary paperwork to fill out—the Coggins test, customs paperwork. We took three over to Pornichet last August. It was a real faff—I’m glad we had a winner and a place.” The hassle, however, is not sufficient to put Moon off making future forays to France. “The prize money’s much better, there’s more choice of races and we have French-breds which qualify for the premiums. They pay out down to sixth place; they look after the owners and the breeders. Since Brexit and COVID, we’ve taken the decision that our breeding stock will stay in France.”

For its part, the Channel Islands Racing and Hunt Club—the governing authority for racing on the islands—is keen to facilitate visiting connections. “We welcome them with open arms”, its honorary secretary, Jonathan Perrée points out, “and try to minimise the bureaucracy as much as possible.”

The low volume of races on the islands and modest prize money beg the question: How do Jersey-based trainers survive? Moon explains, “A lot of the yards over here have split operations, with livery in another yard. The liveries keep the yards buoyant through the winter months.”

For Moon, there is one feature of Jersey’s geography that is of distinct benefit to its trainers. “We’ve got lots of lovely flat beaches, without rocks or holes, so a lot of the trainers will use the sands.” Plans to bring beach racing back to Jersey have been put on the back burner due to COVID-19, but it would be popular with Moon.

“It would be a beautiful, perfect surface for the horses. It would probably ride a bit like Southwell. I think a lot of the trainers would be up for it. And it would be a great spectacle and would also encourage people to come up to the racecourse. It’s definitely the kind of thing they should look at.” The first ever Channel Isles races were on the beach, at St Aubin. Would there not be an elegant symmetry, were beach racing to return to the island, nearly 200 years later?

The enthusiasm and dedication of those who run Channel Islands racing cannot be questioned, and it is to be hoped that its dark days are behind us. I will make a prediction. I suspect that, over the next few years, more British trainers will discover that racing at these beautiful tracks provides all the ‘mini-vacation’ benefits for their owners without any of the Brexit-related costs and hassle. With a fair wind—and I use that term advisedly—we could see an explosion of keen international competition on the Channel Isles.

Equine infectious disease surveillance in Northern Europe

By Fleur Whitlock

Equine infectious disease occurrences remain an ever-present threat, irrespective of the country where a horse resides. With climate change and increased international horse movements, monitoring and surveillance of infectious disease is more important than ever. But how is this conducted in our equine population?

In Northern Europe and the majority of countries worldwide, there are three infectious respiratory diseases commonly found to be circulating in horse populations (referred to as ‘endemic’). These include the viral diseases: equine influenza and equine herpes; and the bacterial disease: strangles. It is essential that horse keepers and their veterinary surgeons remain vigilant and knowledgeable around how these diseases present to ensure rapid implementation of control measures if they occur and more importantly what actions to take to prevent them in the first place.

Why is surveillance vital?

Identifying and controlling infectious diseases when they occur is important to limit both the number of infected horses on a premises and the disruptive and costly effects that disease can have on commercial enterprises, as well as avoiding the spread of infection to the wider horse population. To optimise control and prevention measures, diseases are monitored at a national and international level, through surveillance activities.

How is surveillance conducted?

There are two main ways that equine surveillance is conducted:

1. Statutory reporting of notifiable diseases

Diseases that are notifiable under veterinary or human health legislation in horses may include (but are not limited to and will have country-specific designation): African Horse Sickness (AHS), Contagious Equine Metritis (CEM), Dourine, Equine Viral Arteritis (EVA), Equine Infectious Anaemia (EIA), Glanders and West Nile fever. These diseases have been designated as notifiable, either due to their potential implications for human health, equine health or trade. Statutory reporting is required if a disease is suspected due to suspicious clinical signs or confirmed through diagnostic testing, such as those recommended by the HBLB International Codes of Practice before horses are bred each year. The specific approaches to their occurrences will be disease- and country-dependent but may include movement restrictions and testing of the in-contact population as a minimum. Information gathered from these outbreak investigations is evaluated and shared with the wider industry, through platforms such as the World Organisation for Animal Health - World Animal Health Information System (OIE-WAHIS) (https://wahis.oie.int).

2. Voluntary disease investigation and reporting of positive laboratory test results for non-notifiable diseases

If a horse is examined and undergoes confirmatory diagnostic testing through a laboratory and either the veterinary surgeon or laboratory contributes to surveillance initiatives, the diagnosis may be reported (Figure 1). Alongside this, epidemiological data relating to horse-specific factors such as the horse’s age, breed, vaccination status and specific factors such as approximate geographical location, number of resident horses on the premises and history of recent horse movements may also be available. In addition to this, to increase our understanding about pathogens and how they are changing over time, further analysis of the pathogen isolated from the infected horse(s) may be conducted to determine factors such as the particular strain of the pathogen. Information such as this can then be utilised to inform factors such as vaccination requirements. However, given the necessary voluntary steps that are required for a confirmed disease diagnosis to reach the reporting stage through this surveillance method, reported cases may not reflect the true extent of disease in a particular region or country. Also, some bias in the type of outbreaks that get reported may exist as detection and reporting may favour more severe cases, particular groups that undergo required testing or be more likely to be sampled due to subsidised testing costs existing in a particular country.

Figure 1: The pathway of surveillance.

Examples of surveillance initiatives

Country-specific initiatives may be available to encourage diagnostic testing of suspect infectious cases through incentives such as subsidised laboratory fees. In the UK, equine vets can submit nasopharyngeal swab samples from horses with signs that could be indicative of equine influenza, for free PCR testing at a designated laboratory—with this scheme funded by the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) and overseen by Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance (EIDS), University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. In addition to this scheme, EIDS maintains a surveillance network of all commercial laboratories conducting equine influenza testing in the UK, encouraging the voluntary reporting of positive samples and the sharing of associated epidemiological and virological information. Both schemes enable monitoring of equine influenza in the UK, and this is essential given that equine influenza viruses naturally change and adapt, giving the potential for new strains to be more infectious or to emerge beyond the protection imparted by current vaccines. In addition to equine influenza, the UK closely monitors laboratory-confirmed occurrences of equine herpes virus-1 (EHV-1), given its ability to cause neurological signs and abortion in pregnant mares and death of newborn foals. Strangles is also under surveillance with epidemiological and bacteriological data collected and analysed to improve our understanding of this frustrating contagious disease and contribute to improving its control and prevention.

What disease reporting platforms are available?

Figure 3: Examples of the international and country-specific reporting platforms monitored by the International Collating Centre (ICC): an interim email report issued by ICC and a recent embedded disease alert.

Country-specific reporting platforms exist worldwide, and these predominantly notify stakeholders—usually through email alerts—about laboratory-confirmed disease occurrences in the reporting country. Examples in Europe include France’s Réseau D'épidémio-Surveillance En Pathologie Équine (RESPE, www.respe.net), the Netherlands Surveillance Equine Infectious Disease Netherlands (SEIN, www.seinalerts.nl), Belgium’s Equi Focus Point Belgium (EFPB, www.efpb.be) and Switzerland’s Equinella (www.equinella.ch).

Figure 3: Examples of the international and country-specific reporting platforms monitored by the International Collating Centre (ICC): an interim email report issued by ICC and a recent embedded disease alert.

Complementary to this, the International Collating Centre (ICC) is overseen by EIDS and supported by the International Thoroughbred Breeders’ Federation (ITBF) and International Equestrian Federation (FEI) and has for over 30 years collated outbreak reports from available country-specific reporting contacts and platforms worldwide. In addition, EIDS receives reports directly from veterinary surgeons and diagnostic laboratories (Figure 2). Collated reports are sent to registered subscribers on an almost daily basis through an email that contains embedded links to specific ICC outbreak alerts. A quarterly summary report is also produced and emailed to subscribers four times a year and is available in the resources and archive section of the ICC website (https://equinesurveillance.org/iccview/). Reported outbreaks are predominately made up of at least one case that has had the diagnosis confirmed through laboratory testing. It is therefore expected that those outbreaks that reach the reporting stage by the ICC will not reflect true infectious disease frequency within the international equine population; and a country with no reported outbreaks of a disease does not necessarily mean that the disease is not present in that country.

Figure 3: Examples of the international and country-specific reporting platforms monitored by the International Collating Centre (ICC): an interim email report issued by ICC and a recent embedded disease alert.

There is an interactive ICC website enabling analysis of all international infectious disease outbreaks reported through the ICC, which was launched in August 2019; and outbreak data for all of 2019 onwards is available through this platform. Through the ICC, infectious disease outbreak information is shared with stakeholders throughout the world, ensuring people remain up to date through this active communication network.

In addition to the ICC, EIDS has an equine influenza-specific platform, EquiFluNet (www.equinesurveillance.org/equiflunet), which presents influenza outbreak reports for the UK and worldwide.

A summary of the recent findings of surveillance initiatives

Equine influenza

During 2019, Europe experienced an epidemic of equine influenza with widespread welfare and economic effects, including the temporary ceasing of horseracing in the UK. During 2021, influenza occurrences in Europe reported by the ICC returned to a more expected level (Figure 3). However, the potential of viral strain changes alongside international horse movements makes monitoring and surveillance of this virus essential.

Equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1)

During 2019, Europe experienced an epidemic of equine influenza with widespread welfare and economic effects, including the temporary ceasing of horseracing in the UK. During 2021, influenza occurrences in Europe reported by the ICC returned to a more expected level (Figure 3). However, the potential of viral strain changes alongside international horse movements makes monitoring and surveillance of this virus essential.

Equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1)

Figure 2: European countries reporting equine influenza outbreaks in Europe through the ICC for 2019, 2020 and 2021.

EHV-1 is endemic in Europe, and the ICC regularly reports on occurrences of EHV-1 disease. An example of an ICC report released during 2020 detailed an outbreak of EHV-1 neurological disease on a premises in Hampshire, United Kingdom, with multiple equine fatalities (Figure 4 – left panel). Another example of an ICC report included a widespread neurological EHV-1 outbreak that occurred in Spain at several international show jumping events during 2021 (Figure 4 – right panel).

Figure 4: The International Collating Centre(www.equinesurveillance.org/iccview) reports detailing outbreaks of equine herpesvirus-1 neurological disease in Hampshire, United Kingdom in January 2020 (left) and Valencia, Spain in February 2021 (right).

West Nile fever (WNF)

Figure 5: European countries reporting equine WNV outbreaks in Europe reported through the ICC from 2019, 2020 and 2021.

WNF is caused by West Nile virus (WNV) by biting mosquitoes, with birds acting as sources of the virus. It is a zoonotic disease, meaning humans can become infected if bitten by an infected mosquito. The ICC has reported equine cases across Europe over recent years (Figure 5). Given that many countries in Europe remain ‘free’ from WNV, it is still possible for horses to have neurological signs such as weakness and incoordination or even death following infection. Humans can also be affected if bitten by an infected mosquito, so monitoring and surveillance of equine WNF occurrences, alongside mosquito, bird and human surveillance are essential. By way of example, WNV was confirmed in birds and humans in the Netherlands for the first time in 2020, but as of March 2022, it has not yet been confirmed in horses.

Summary

Having an appreciation of how and why surveillance of equine infectious diseases are conducted helps to improve engagement with and encourage an increased contribution to surveillance initiatives. A well-informed view on equine infectious disease outbreaks worldwide ensures continued advancements in enhancing control and prevention measures. This in turn will help reduce the risk from disease outbreaks and ensure the industry can continue to operate to its full potential.

Sources for further information about equine infectious diseases and their control and prevention are available

More information about equine infectious diseases and prevention/control:

Horserace Betting Levy Board’s International Codes of Practice 2021: https://codes.hblb.org.uk/

Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance (EIDS) website, hosting the International Collating Centre (ICC) and Equiflunet: www.equinesurveillance.org

Sign up to receive International Collating Centre reports by contacting EIDS: equinesurveillance@gmail.com

Jim Bolger - What he has achieved in racing and the thoroughbred breeding industry will never be replicated

By Daragh Ó Conchúir

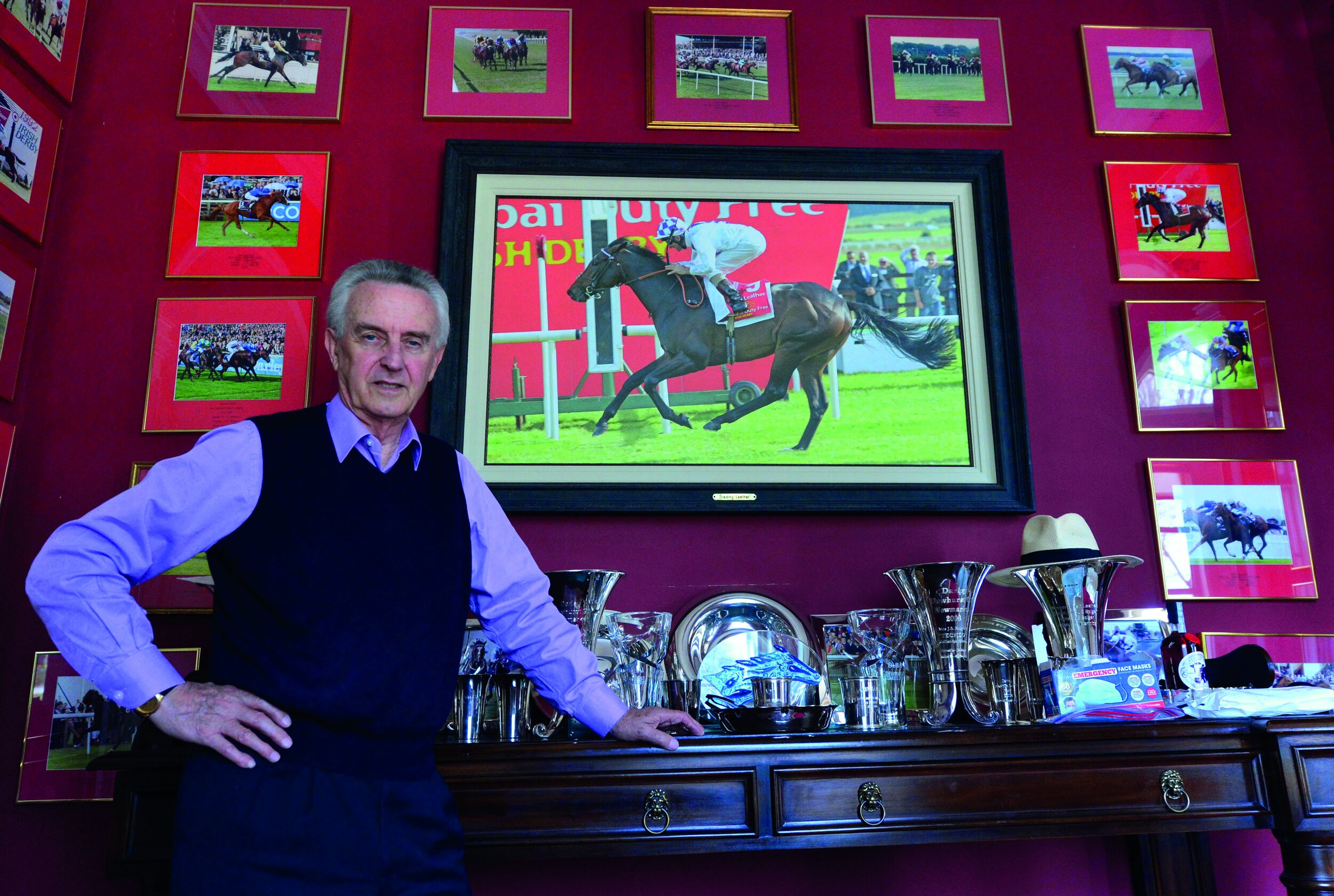

Some interesting comments there from three behemoths of the racing and commercial bloodstock world that sum Jim Bolger up and though made in the past, they were emphasised once more in the present, by the exploits of Poetic Flare and Mac Swiney, and by risking the opprobrium of most of his training colleagues and the wider industry in claiming that doping is a serious problem in Ireland.

Coolmore titan, John Magnier referred to Bolger not being a mé féiner, which for our non-Gaelic speakers, is someone motivated only by self-interest. Bolger, he argued, had always had the best interests of the wider industry and people within it, at heart. Also, he was a straight shooter.

Joe Osborne, MD of Godolphin Ireland, compared the Wexford native, who turned 80 on Christmas Day 2021, to Tesio and it was appropriate. There is no one else in racing now operating at the scale he does as someone who breeds so that he can race in numbers and quality. Unless the landscape of the industry alters significantly, there will never be another. Osborne spoke too of Bolger’s courage.

And then there is the espousal by the man himself of the type of philosophy that doesn’t feature in too many self-help books. Don’t be afraid of doubling down if you think you are right, even if first impressions are that the initial call was an error or it went badly wrong on you. That is a testament to his self-belief. Some might call it stubbornness. Call it what you like, we know as a result of what he has built since starting off at Phoenix Park, that it can work – as long as you know what you’re doing.

Galileo, who died last year after a decade of dominance in the stallion stakes, wasn’t even a second thought for breeders until Bolger intervened. Some of that, of course, was necessity. He could not afford to access the commercially popular routes, so had to be creative.

The result was an unprecedented dominance by one stallion but even though he long since has been priced out of sending his mares to the Coolmore record breaker, the proud son of Oylegate was reaping the benefits still in 2021.

Bolger bred and trained Teofilo to an unbeaten champion two-year-old career in 2006 before injury prevented the colt from attempting to translate that brilliance into classic glory. That success and the Irish Derby victory of Soldier Of Fortune, who also came into the world and was reared at Bolger’s Redmonstown Stud before being sold to Coolmore, rewarded the support of a sire whose first crop had failed to deliver. New Approach emerged from the third crop, out of Bolger’s first Champion Stakes winner Park Express, to be champion two- and three-year-old, emulating his sire to win the Epsom Derby.

Teofilo is the damsire of Mac Swiney, who followed up Group 1 success as a juvenile by edging out stablemate Poetic Flare in a thrilling renewal of the Irish 2000 Guineas last summer. Teofilo is also the sire of hugely impressive Ascot Gold Cup victor, Subjectivist, bred by Bolger too. Of course the now Coolcullen resident bred and trained Mac Swiney’s grand dam Speirbhean, and his dam Halla Na Saoire.

It wasn’t just the backing of Galileo that marked Bolger’s outside-the-box thinking. See Mac Swiney’s pedigree for evidence of a lateral approach – the first Group 1 winner inbred to Galileo, in this instance, 2x3. It just isn’t the done thing but that wouldn’t ever put the man off.

Last year he sold a Teofilo filly at Goffs who was 2x2 to Galileo and 3x3 to Danehill. To the non-pedigree gurus, that means Galileo is both her paternal and maternal grandsire, while both her grand dams by Danehill. It isn’t that the rule book wasn’t read, it’s just that the bits that didn’t add up to him have been ignored. And the results keep coming.

Poetic Flare and Kevin Manning were effortless victors of the St James’s Palace Stakes

There would have been no Poetic Flare without that initial support of Galileo either. Again, the Newmarket 2000 Guineas and St James’s Palace Stakes winner’s dam and grand dam, Maria Lee and Elida, were bred and trained by Bolger, but so was his sire, who had preceded him on both those rolls of honour. Dawn Approach, grandson of Galileo and Park Express, now stands at Bolger’s Redmonstown Stud.

There was a week in October 2020, when Bolger bred four juvenile stakes winners, two of them Group 1 winners, and he trained three of them, who ran in the colours of his wife Jackie.

When Poetic Flare prevailed in a ding-dong battle with Master Of The Seas at Newmarket last May, Bolger was the first since John Barnham Day in 1844 to breed, own and train the winner of the mile classic. It would have been eight years earlier only he sold Dawn Approach to Godolphin towards the end of the horse’s juvenile campaign.

That places context on his training and breeding feats in 2021. That his 54-year-old son-in-law Kevin Manning was still in the plate, as strong as an ox in Newmarket, cool as a breeze at Royal Ascot, was surely the cherry on top of the cream. They have shared glory all over the world together. The trainer isn’t the only one of them for whom age is no barrier to attacking a day and any challenge that comes with it, with vigour.

Courage, conviction and he would argue, a sense of fair play for all, were behind his decision to speak out about his suspicion that doping is a major problem in Irish racing, initially in an interview in The Irish Field at the time of his spectacular breeding success in October 2020.

He discussed the issue in greater depth in interviews with Paul Kimmage in the Sunday Independent and in other interviews, in print and podcast, though some demanded more detail.

While there was some support from trainers, most notably Ger Lyons, Johnny Murtagh and Richard O’Brien, and a handful more that expressed such support below the radar, by and large, his peers were outraged.

He decided not to accept an invitation to appear before the Joint Oireachtas Committee to look into the claims. That was prudent legally and while the Twitterati scream for names, you can know things and not be able to prove them. That failure to show or offer hard evidence has been interpreted by the majority within racing as meaning he has nothing and is engaging merely in “pub talk”, as Aidan O’Brien, his former assistant put it. The leadership of the Irish Racehorse Trainers’ Association, of which he is no longer a member, was more scathing.

The raid on a stud farm just outside Monasterevin is concerning however, though details remain sketchy, not least surrounding the identity of substances confiscated from John Warwick.

That a conversation began, that media outside racing media took an interest, that bodies outside of the Irish Horseracing Regulatory Body took an interest, that measures to beef up dope-testing were beefed up considerably albeit that such measures had been mooted for some time, that the IHRB now faces inevitable changes of governance and structure as a result of recommendations for the Joint Oireachtas Committee that arose from his comments, will have pleased him.

But if there is doping, the cheats need to be rooted out. And if there isn’t, the system needs to be robust enough to ensure that there is confidence in this being the case. But Lance Armstrong passed 500 tests. Most forms of enforcement are reactive, the cheats, the criminals lead the way.

Mac Swiney’s narrow success under Rory Cleary over Poetic Flare in the Irish 2000 Guineas represented a stunning imprimatur of the Bolger methodology

That’s where retrospective testing comes in and given the samples are kept, one hopes that this might happen. It is all for the benefit of the sport and business in the end. Bad publicity that might come from unearthing cheating is something to be proud of because it is something you can stand by. As Murtagh said, “The guns are out… This will be good for Irish racing.”

Prior to the Irish Champion Stakes, Bolger told Johnny Ward, of this parish, in an interview in The 42 that what marked Poetic Flare out was talent and robustness. “I’ve trained nothing as hardy as him.”

Fashioned in his maker’s image, it seems. Completely durable. Suffice to say, in his four score years, the boss of Glebe House and Redmonstown Stud has left his mark and continues to do so.

Nigel Tinkler - A Full Circle, or Full Steam Ahead?

By Mark Rowntree

Four decades have passed since a youthful Nigel Tinkler started training racehorses at Boltby, North Yorkshire. But the unbroken will to succeed through tried and tested methods burns stronger and brighter than ever.

The Tinklers have always been synonymous with success, with Nigel’s mother, Marie Delfosse, landing showjumping’s prestigious Queen Elizabeth II Cup at Wembley in 1953 prior to going on to forge a successful career as a point-to-point jockey. His father, Colin Sr, was raised in Nottingham, working as a stable employee to the North London-based Delfosse family before becoming a car dealer in Scarcroft (Leeds) and then a trainer. Older brother Colin Jr—father to jockeys Andrew and Nicky Tinkler—was also drawn to explore the family lifestyle of choice, namely training racehorses.

Nigel explains, “Basically, I knew nothing else other than horseracing from about the age of seven. Watching the Derby and the Grand National became like a drug to me, and my memory could easily chart the entire history of those great races. For the current generation of youngsters, history is often seen as less important than the present, even with the distinct advantage of Google or Wikipedia.”

Since 1666—instigated by King Charles II—the Newmarket Town Plate has been a similarly fiercely contested annual event. With the lure of a string of Newmarket sausages to the winner, Tinkler, then aged 12, first took to the saddle to compete over a demanding three-and three-quarter–mile circuit. Just over three years later, at Sedgefield on Boxing Day 1973, Nimble Joe became Tinkler’s first winner as a full-fledged jockey.

Tinkler went on to notch an impressive 200-plus winners in the saddle, but the lack of a steady income from riding gradually edged him closer toward the training ranks. Citing the frustration of being taken off horses on the biggest of all stages, he says, “I broke a few bones and all, but the main thing I broke was my heart. I probably did too well too early and wasn’t quite mature enough to deal with the bigger jobs. When I was younger, I was quite ignorant—a cocky bastard—although I did have a lot of enthusiasm to improve and learn.”

Initially Tinkler took over the training licence from his father, saddling his first winner over hurdles (Just Jet) at Wolverhampton in early November 1980, but it soon became clear that he needed his own space.

“I decided to move into training and quite honestly thought that with a dozen or so horses, and if I gambled on them, I could earn as much in one day as in one year as a jockey. I didn’t view this as taking a punt; it was more akin to investing, and that’s how I set off as a trainer, buying the yard and building the stables.”

“The property at Langton (near Malton) was a market garden when I bought it for £49,000. I was told that I was crazy, but I couldn’t keep training from Boltby; my father was getting sick of me.”

“I looked at yards in Middleham and various other properties elsewhere, including the Camacho’s, Roger Fell’s and Malcolm Jefferson’s; but after a year or so of searching, I settled on Woodland Stables. I've never sought to move as I love northern racing; our local racecourses are a lovely way to spend a summer afternoon.”

Tinkler doesn’t seek to mask the fact that gambling played a pivotal role in developing and building the business. “In the early 1980s, I’d be having £2,000 on just four or five horses per year. It was very difficult to lose, and this helped me to build the yard. Ironically, I hardly bet nowadays.”

For the Tinklers, progress didn’t occur by chance. An insightful vision from Colin Sr—long before syndicate ownership was viewed as an acceptable form of ownership—led to the creation, rise and expansion of the Full Circle Syndicate.

“When I first started training, if someone called and said, ‘Can I have a half share in a horse?’, I’d say no, but please do come back when you can afford a full share. Frankly, I was doing alright before my father set up the Full Circle.”

“However, Full Circle provided the opportunity for anyone to buy a horse; my father was well before his time when you look back with Highclere, Middleham Park, Elite Racing and Ontoawinner—all among the current list of successful syndicate operators.”

Tinkler Sr faced an uphill battle in launching the Full Circle Syndicate, having firstly to go to the Jockey Club to seek a change in rules, which at that stage permitted only 12 individuals to own a horse. Shared ownership, even in quarter shares, was considered unusual, and he wanted to have 360 shareholders per horse: hence Full Circle.

Nigel explains; “I said we’d get approximately 100 shareholders—at £450 per year—but after a Cheltenham Festival winner (The Ellier) and a Grand National third (Monamore), we ended up drawing in £13,000!”

Without a shadow of doubt, the rise of the Full Circle Syndicate captured the attention of those closely associated with racing, but perhaps more importantly also the imagination of the general public at large. Far from resting on his laurels, and as outlined by Tinkler Jr, Tinkler Sr was ever so swift in capitalising upon that initial success.

“My father ran a premium-rate tipping line adjacent to Full Circle and was soon receiving weekly dividends of £10,000. For clarity, the Full Circle shareholders had their own ordinary (non-premium rate) telephone number to call for private and confidential information.”

“In those days, before a bar was placed on such premium-rate services, people were simply going to work and calling the tipping line, or in some cases, the sex line! He’d say to me, ‘I’ve got terrible trouble with the phone line; can you give it a ring to check’? Thank you; that’s working fine, and another £2 goes straight into the coffers.”

Partly after stricter regulations were introduced on 0898-style phone numbers, the success and the allure of the Full Circle ebbed away until the syndicate eventually ceased to operate. Nevertheless, as Tinkler is keen to stress, Full Circle played a major role in changing the overall landscape of racehorse ownership.

“Times have certainly changed for the better; racing was once known as the sport of kings, but now it’s the sport for all. In 2022, a small share in a horse with Middleham Park Racing can have you standing in the paddock next to Her Majesty the Queen.”

For Tinkler, National Hunt Racing was always his first love, with horses such as The Ellier, Rodeo Star, Bank View, Sacre D’Or and Satin Lover propelling his training career forward at a rapid rate of knots. The Ellier (under Gee Armytage) took the Kim Muir Chase at the 1987 Cheltenham Festival, while a mere six year later, Sacre D’Or plundered the Mildmay of Flete over those same hallowed Prestbury Park fences.

Ironically, in 1991, it was the ill-fated State Jester for whom Tinkler harboured Cheltenham Festival aspirations. After a couple of years of searching for the perfect replacement, Sacre D’Or emerged. Tinkler recalls: “An owner with John Mackie was seeking funds, so Sacre D’Or became available prior to Cheltenham for £22,000. After viewing the horse, my owner said, ‘We’ll offer £20,000’; but I was adamant that for the purposes of luck we should offer the full asking price. When he went on to win the Mildmay of Flete, the first thing I said to my owner was that it’s a good job you gave the full £22,000!”

By the late 1980s, Tinkler was also beginning to make his mark as a flat trainer, even though by his own admission, and despite notching a combined total of nearly 80 winners (1988-89 season), he’d become a little blasé. “Looking back and being self-critical there was no reason to be running horses worth £15,000 in sellers. I’m totally different now, and I’ve never been as dedicated to training as I’ve been over the past few years.”

“I knew two years before I stopped training jumpers that the flat would eventually become my life. The type of horse that I was buying off the flat could only go so far over jumps. They’d win their novice hurdles and then a novice chase or two, but being flat-bred, they weren’t strong enough to sustain multiple seasons over obstacles.”

“To train jumpers, you’d need to aspire to be competing at Ascot, Cheltenham and Newbury, and unless you had £100,000 plus to spend on a single horse, it was very difficult to do that. For not a lot of money, I’ve had runners at Royal Ascot in addition to horses winning at most of the major flat festivals.”

“My horses have a nice, easy life which surprises some people as it’s not like my general attitude. When I’m with horses, a year is like a click of the finger. I’m lucky with loyal owners who basically throw me the rope, and say, ‘Look, just do whatever you think is best.’”

At a sprightly 36, Rodeo Star remains very much the boss of his plush retirement pad at nearby Wetherby. Bought from Sheikh Mohammed at the Newmarket Sales, and with Martin Pipe acting as underbidder, he was knocked down to Tinkler for £26,000. Tinkler speaks fondly of Rodeo Star.

“He won first time out for us at Newcastle before winning a Tote Gold trophy and a Chester Cup. We took him to Chester on the Monday prior to the race in midweek and worked him around the track under Nicky Carlisle. Immediately afterwards, I said, ‘Right, let’s go and celebrate him winning with a Bucks fizz and champagne breakfast.’ He was a good horse—a very good horse.”

Despite those vividly fond memories, Rodeo Star wasn’t the best horse to pass through Tinkler’s hands at Woodland Stables.

“Sugarfoot was the best horse I’ve ever trained. He won first time out at Ayr as a two-year-old before taking a break. I kicked James Lambie (of the Sporting Life) out of the pub one evening when he had the [audacity] to suggest that the horse must have an injury. I said, ‘He isn’t injured, but he’s our horse and we can do what the f**k we want with him.’

“We backed him each way to win a lot of money (at 40-1) in the 1998 Royal Hunt Cup. He finished fourth under Royston French, but had he been drawn on either side of the track he’d have won that race. He carried 7st 12lb there but was a proper group horse in the making.”

“The next summer he was 107-rated, and with York’s Bradford & Bingley being a 0-105, I rang up the handicapper and said, ‘Look, I’ve got a real problem here. The owner is very unwell (he sadly passed away the following year), and with a real lack of races in which to run, it would help enormously if I could have 2lb back from you in order to race at York.’ I called again from the gallops at 10am the following Tuesday; 105 [rating]. Result: I’d seen him working at home knowing full well that he was a 110-plus horse for the future, and the race at York was ours for the taking! With none other than Kieran Fallon booked to do the steering that afternoon, [he] gave his seriously ill owner such an immense thrill.”

Tinkler’s training methods have demonstrably stood the test of time, and despite recognising that he’s probably become “a little OCD”, that can only be attributable to a deep passion and enduring admiration for the racehorse.

He eludes, “When Ubettabelieveit went to the Breeders’ Cup, I took him, I rode him, I led him up. When I have a runner at Ascot, I’ll go and walk up with the horse from the stable yard. The other trainers staff know what I’m like, but I do think some of them have respect for what I do.”

“When the press approached me for interview straight after Acklam Express had finished second in Dubai, I said, ‘No, I must go and see the horse first.’ The horses are my best friends.”

As a man who has saddled well over 1,000 career winners, Tinkler acknowledges a certain element of change has occurred with regards the training of racehorses, but his spark and vigor for life continue to be fueled by searching for the highest possible level of performance from each individual horse within his care.

“With training nowadays, the big difference is that you can win a 0-60 handicap with an arm in a sling. When I first started training, you’d have a horse entered for a race a month before, and after he’d run, he’d have a few days break before selecting the next target. You trained every single horse to suit his or her individual needs.”

“Some will state that Martin Pipe revolutionised the training of racehorses, but when the five-day entry system was introduced, most started training their horses on a higher rev-counter. Horses are now usually fit and ready to race but, in my opinion, horses being trained on a higher rev-counter leads to more injuries and therefore a shorter racing career.”

“You can’t have a horse spot on for a race if you make the decision to compete only 48 hours before. It’s like making a Christmas lunch and saying we don’t know whether we’re going to eat on Christmas Eve, Boxing Day or a week later.”

It is testament to Tinkler, that although driven firmly by the strength of his own convictions, he seeks to heap praise upon those to whom he is closest, stating, “I wouldn’t swap my staff.”

“My secretary Samantha (Mark Birch’s daughter) has been with me for 28 years. Helen Warrington has been with me for 22 years. She’s one of the main work riders. My wife Kim—I probably should’ve mentioned her first—rides out four or five lots every single day, and I’d be lost without her.”

“Kim and Helen feed off each other, and I’m just there to pick up the pieces. They train the horses as much as I do. It’s not Nigel—it’s the whole unit.”

Despite such praise, Tinkler is vociferous in expressing his opposition to the recent introduction of joint licences in Britain. “I don’t believe in joint licences, and in any case, I’d have to have the entire team listed as the trainer. How far down the line do you go?”

“If ever you were to get into trouble, how do you penalise or suspend two people? A single-named person must be held accountable. A lot of the time owners don’t like to have horses with people who are older than themselves, so perhaps this is a reason for the greater involvement of the younger generation (i.e., Mark and Charlie Johnston).”

Wife Kim is a qualified jockey coach—a form of mentoring, which had it been available in the early 1980s, Nigel believes it may have prolonged his riding career. Kim is a massive influence behind the scenes at Langton.

“Kim coaches our jockeys, and it’s down to her that our riders have finesse. She not only focuses on their riding style, but also advises on their diet and way of life.”

“Many people think that Kim was lucky because she was small and light, but she was only light because she controlled her diet and exercised properly. At 18, she got to 9st 2lb, but by the time she reached 20, her regular riding weight was 7st. That didn’t happen without a fair bit of effort! She was a dedicated rider (the leading female jockey), and she rode us many, many winners.”

“Jockeys have always had a problem with weight. It hasn’t suddenly become an issue, and it always will be an issue. Wherever you place the line, there’ll be a jockey struggling to make the weight.”

Even in the days when female jockeys were under-represented in the sport, Tinkler recognised added value and was willing to offer competent riders mounts. He explains: “My mother was a jockey; she was leading amateur a couple of times, and I soon realised she had a lot of ability and that horses ran for her. I think the horses like the girls, and some ride a good race and are conscientious.”

Harking right back to the Graham McCourt era, a stable jockey has always been viewed as a necessity to Tinkler. “Graham’s determination to win was simply unbelievable—far exceeds any other jockey that I’ve had riding my horses since. He was so strong that he won on horses that shouldn’t have won.”

Hawick native Rowan Scott, described as being “very chilled”, is the current stable jockey at Langton. Tinkler says, “Rowan is a natural horseman, and it makes no difference to him whether he’s riding in a Gp2 in Dubai or a seller at Redcar. He finds it very easy to ride horses as he’s such a natural.”

Understudy to Scott is the bubbly Lancastrian Faye McManoman, who has flourished with an increased exposure to professional race-riding and the ongoing support offered by jockey coach Kim.

“When a horse comes home after, say, Faye McManoman has ridden them, they’ll usually eat their dinner. Often under more forceful handling, horses can come home and sulk. It’s no problem if a jockey (male or female) is less forceful than a counterpart, so long as there is consistency. The important thing is the horses enjoy their race.”

“When Faye first started riding, she was very moderate. She has worked her socks off to improve. She now rides a good race, and her percentage of winners for the quality of horses she rides is solid.”

“For most races, I’m more than happy for Faye to ride, and the owners love her. In truth, I’m very easy to ride for as long as you try to do it my way. It’s not difficult.”

Tinkler is a hearty advocate of placing a supporting arm around an individual in times of need, but he equally craves strong and rigid leadership from the British Horseracing Authority (BHA). Discussing a recent high-profile disciplinary case, Tinkler says; “To think that a jockey fails a breathalyser test in May, but the case isn’t heard until the following February isn’t good enough for the individual concerned, the other jockeys that are riding or indeed the horses competing in those races.”

“It’s not a greatly expensive job to test riders daily. The BHA are testing a few horses per day on a racecourse, and if a horse is unable to produce a simple urine sample, the costs incurred are significant. Given the amount spent on testing those horses, and without having a go at anyone at all, a jockey who is known to have an issue should be tested daily until the authorities are satisfied those issues have been resolved.”

“It’s basically common sense that we should be testing jockeys more often. Plenty of jockeys have needed support in the past, and plenty will continue to do so in the future, but we can’t have the situation where riders are competing under the influence of alcohol, drugs or whatever.”

So, what of the future for a resurgent Tinkler?

“I’d been doing okay training 20 or so winners per year until I got a contact in Hong Kong which resulted in me shifting the emphasis to selling some of the better horses before they’d raced. Obviously, I was doing very nicely out of selling these horses abroad, but some people began to question my skills as a trainer as the total number of winners fell. I addressed that, and the winners have flowed again in recent years. 2021 was my best tally on the flat (41 winners), and as a result, I’ve gained more and more new clients. It’s all snowballed.”

Ubettabelieveit (centre, red cap) was Nigel’s first runner at the Breeders’ Cup and finished third to Golden Pal in the 2020 Juvenille Turf Sprint

“In 2020, we were lucky to buy Ubettabelieveit because in an ordinary year he’d have gone to the breeze-ups, but given the COVID situation, the vendors were in a difficult spot in that they didn’t know what was going to happen. There were two horses that we liked, and I didn’t know which one to pick, so I rode them both myself and chose Ubettabelieveit, which turned out not to have been a difficult decision!”

“It wasn’t easy for us getting into America to see Ubettabelieveit compete at the Breeders’ Cup. We had to change flights in Atlanta, and the customs officer wouldn’t let me proceed. So I asked Max Pimlott [International Racing Bureau] to pass the papers, which stated I was the trainer.”

He said, “We’re in Atlanta; I don’t think anyone will be bothered about what is happening in Kentucky!”

“During the coronavirus pandemic, you couldn’t simply walk in the United States. I was placed in a room for over an hour while all the paperwork was checked and double-checked.”

“The Breeders’ Cup was a brilliant experience though, and Kentucky is simply out of this world. If you had three or four lives, you’d have one of those in Kentucky.”

With an evident sparkle in his eye, and a glowing smile across his face, Tinkler offers a typically frank and forthright assessment of current stable star Acklam Express: “We knew his three-year-old season would be difficult, so we thought we’d be better off running during the winter. At his age, we knew that facing the top sprinters would be like banging his head against a brick wall.”

“He did run a good race in the King’s Stand Stakes at Royal Ascot (10th), but we thought, Where are we going to take him next? He needed a little time off to mature, so we took him to Cliff Stud (Helmsley) and turned him out with a view to running in three races at Meydan in early 2022. After that, we’ll certainly think about running him in the United Kingdom during the summer—with the King’s Stand a possible starting point. But we won’t make any firm decisions until the end of April.”

As Tinkler’s playful mind turns to a second or third life somewhere exotic (prior to Kentucky), he also acknowledges the long-standing haven of Malton, North Yorkshire as home away from home. With ambitious local trainers Brian Ellison and Julie Camacho equally instrumental to the ongoing improvements at a shared gallop, and with first-class facilities already on offer at Woodland Stables, the future for any prospective Nigel Tinkler inmate remains rosy.

SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS

The story of Never Say Die

By James C. Nicholson

The first Kentucky-bred winner of the Epsom Derby would earn a place in Thoroughbred racing lore and even played a small role in the early history of the most successful musical group of the twentieth century. But he nearly didn’t survive his first night of life.

In late March 1951, John Bell and his wife returned from a night out to find that a new foal had arrived at their leased acreage outside Lexington. Its mother, an undersized daughter of American Triple Crown winner War Admiral named Singing Grass, was exhausted, as was the barn foreman who had helped her with a difficult delivery.

Never Say Die

The unusually large chestnut colt, by Irish-bred stallion Nasrullah, was having trouble breathing as he lay beside his mother. His right foreleg was tucked awkwardly under his body. Concerned that the newborn might not make it, Bell retrieved a bottle of bourbon whiskey from a desk in the tack room. He took a quick nip for himself and poured the rest of the bottle’s contents down the throat of the struggling foal. The elixir revived the woozy colt, which, fittingly, would be named Never Say Die.

After being taught to carry a rider by Bell and his Jonabell Stables team, the colt was sent to the Newmarket training yard of seventy-two-year-old conditioner Joe Lawson, who had twice been British flat racing’s Champion Trainer, and had captured most of England’s top races, but for whom the Derby had proven elusive. The colt’s owner, Robert Sterling Clark, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune, split his horses between Lawson and another trainer named Harry Peacock. Peacock had won a coin flip to determine which man would receive first choice of Clark’s horses that year. Though he liked the look of Never Say Die, he was not interested in training a son of Nasrullah. Nasrullah was well on his way to one of the most outstanding stud careers in history, but the memory of the stallion’s inability to run to his potential because of temperamental idiosyncrasies was still fresh for many British horsemen.

Never Say Die had been a gangly foal, but he filled out to become a lovely, compact, balanced young colt with a slightly better disposition than that of his notorious sire. Though he never displayed the mental peculiarities on the racetrack that Nasrullah had, Never Say Die did develop a reputation for moodiness and difficulty among the humans that cared for him.

A turf writer for the Daily Express observed that Never Say Die had “an excellent, strong, straight pair of hind legs, even if the joints appear to be somewhat rounded. The captious critics might say that he is over-long of his back. Undoubtedly his best points lie in front of the saddle. There is a rhythmical quality about the set of his neck, shoulder, and powerful forearm which is carried down through the flat knees to a hard, clean underpinning.” The handsome colt’s most notable feature was a prominent white blaze that ran the length of his head—from above his eyes to the tip of his nose.

After some encouraging performances as a two-year-old, including a win in the six-furlong Rosslyn Stakes at Ascot and a third-place finish in the Richmond Stakes at Goodwood, Lawson held guarded hope for Never Say Die at three, and believed a talented young rider named Lester Piggott would help the American colt reach his potential.

John A. Bell III at Jonabell Farm. Never Say Die’s success helped Bell establish Jonabell Farm as one of the leading Thoroughbred operations in America

If anyone was ever destined to become a jockey, it was Lester Keith Piggott, born in 1935 on Guy Fawkes Day in Oxfordshire. The branches of Piggott’s family tree were littered with jockeys and equestrians, dating back to the 1700s. His grandfather Ernie Piggott had won the Grand National three times as a jockey. Lester’s grandmother came from a long line of riders that included her two Derby-winning brothers. Lester’s father, Keith, was a successful jockey, winning five hundred races over a thirty-year career, before becoming a champion trainer of jumpers. Lester’s mother, Iris, also descended from a long line of top-notch jockeys and trainers and was an accomplished rider in her own right.

Lawson took his time with Never Say Die early in his three-year-old season. With eighteen-year-old Piggott in the irons, the colt began the year with a respectable second-place finish in the Union Jack Stakes at Aintree. He regressed next time out, starting slowly in the seven-furlong Free Handicap at Newmarket, and never factoring in the race. But when stretched out in distance two weeks later for the Newmarket Stakes, Never Say Die gave a performance good enough to convince his owner to give him a shot in the Derby. Though he had tired in the late stages to finish third, he was beaten just a half-length and a head in the ten-furlong test.

Piggott had chosen to ride at Bath that day, and Lawson was inclined to remove him from the Derby-bound colt for his disloyalty. Fortunately for Piggott, the trainer’s first three choices to replace him already had Derby mounts. With the “boy wonder of the turf” again aboard, Never Say Die joined twenty-one rivals on a chilly and damp afternoon at the starting line for the 175th running of the Epsom Derby. Top contenders included Darius, the Two Thousand Guineas victor; Rowston Manor, winner of the Derby Trial Stakes at Lingfield; and the Queen’s colt, Landau. Bookmakers listed Never Say Die as a 33 to 1 long shot. His odds would have been even higher but for the popularity of his young rider and the charm of the colt’s name.

Never Say Die was away quickly from the starting barrier and fell in just behind the first group of front-runners in the early going. He maintained his position, clear of trouble, into Tattenham Corner. Rounding the final turn, Piggott bided time, well off the rail and just behind Rowston Manor, Landau, and Darius. Early in the final straight he eased his mount to the outside. Passing tiring rivals, Never Say Die roared to the front in mid-stretch and strode on for a two-length win, to the astonishment of hundreds of thousands in attendance and millions listening to the BBC radio broadcast.

With his colt’s Derby conquest, Sterling Clark became the first American owner to win the renowned race with an American horse that he bred himself. In the Derby’s long history there had been only one American-born horse to win—Pennsylvania-bred Iroquois, in 1881. No horse born in Kentucky, the commercial breeding center of the American Thoroughbred industry, had ever won the British Classic.

American horsemen were overjoyed. In The Thoroughbred Record, a Kentucky-based weekly publication, columnist Frank Jennings noted that, prior to Never Say Die’s victory, “repeated failure on the part of Americans in the English Derby not only was becoming monotonous but was downright discouraging. Men of less determination and means than Mr. Clark gradually had become reconciled to the idea that a score in the big race at Epsom was virtually impossible with a colt bred and raised on this side of the Atlantic. Never Say Die did a great deal toward changing this thought and at the same time [demonstrated] that American bloodlines, when properly blended with those of foreign lands, can hold their own in the top company of the world.”

The seventy-six-year-old Clark had lived a remarkable life. He had served as a U.S. Army officer during the Spanish-American War and the Boxer Rebellion, led a research expedition through rural Asia, and built one of the finest private collections of European painting masterpieces in the world. In his later years, he created the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute near the campus of Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. But nothing provided him greater satisfaction than that historic Derby triumph.

Clark learned the race result via telephone. The winning owner was in a New Your City hospital, having chosen not to postpone some scheduled tests. But he was often reluctant to attend the races even when circumstances did not preclude his presence. Large race day crowds made him nervous.

An impromptu champagne celebration was organized in the hospital room, and Clark proposed a series of toasts. A small group of friends and family first drank to Piggott and Lawson. Then they saluted Bell, the young Kentucky horseman whose fast thinking had helped the Derby champion survive his first night and at whose Jonabell Farm the colt was raised and introduced to a saddle. For Bell, born into a wealthy Pittsburgh family that lost its banking and coal fortune amidst scandal when he was still a child, Never Say Die’s Derby score provided a vital piece of early publicity for his fledgling equine operation that would eventually become one of the most respected in the world and, following a 2001 sale to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, home to Darley’s North American stallions.

In Liverpool, two hundred thirty miles northwest of Epsom, a middle-class housewife named Mona Best listened to the BBC broadcast of the Derby on the family radio. When the results were announced, she jumped for joy. Mona had pawned her jewelry to finance a bet on Never Say Die because she fancied his name. With her winnings, she put a down payment on the house she had long admired, a large fifteen-room Victorian at 8 Hayman’s Green in the West Derby section of Liverpool.

Before it was fixed up, children called it “Dracula’s Castle.” But it had an unusually spacious cellar where, after renovations, Mona opened the Casbah Coffee Club as a place where her son Pete and his friends could congregate. The idea proved much more popular with the neighborhood youth than she had imagined, however, and soon the club had a thousand members who paid an annual fee of 12 ½ pence.

A group of teenaged musicians called the Quarrymen played the opening night in late August 1959, after helping to paint the walls and the ceilings that summer. Their set included American rock n roll favorites such as Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally” and Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven.” The group’s name was a nod to Quarry Bank High School, which their lead singer, John Lennon, had attended. Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ken Brown rounded out the lineup.

Mona was sufficiently impressed with the four guitarists to offer them a weekly engagement at the Casbah. Their compensation was to be three pounds cash, and all the Coca-Cola and crisps that the boys could consume. Soon the young musicians dropped Brown, changed their name to the Beatles, and were looking for a drummer to join them for an extended booking in Germany. Pete became the Beatles’ first regular drummer and played with the band for two years, including their three formative stints in Hamburg, before being replaced by Ringo Starr at the precipice of international celebrity.

Whereas the Beatles were four lads from Liverpool who took America by storm with music that had distinctly American roots, Never Say Die was an American-born horse with a pedigree dominated by European influence that won England’s greatest horse race. Although Never Say Die’s Derby victory did not have the immediate impact on Thoroughbred racing that the Beatles had on western culture, his win at Epsom in 1954 was an important signal of change that had been taking place for decades. Vast fortunes with roots in the American industrial expansion of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries had made it possible for wealthy Americans and their heirs to purchase many of Europe’s top Thoroughbreds from their aristocratic owners and import them to America for breeding purposes. By the 1970s, American racehorses produced from those European bloodlines would be winning Europe’s top races with some regularity, and with lasting ramifications for the international Thoroughbred industry.

Spain back in the Black Type big time new policy offers hope for other ‘smaller’ racing nations

La Zarzuela racecourse, Madrid

By Dr Paull Khan

This year’s winner and placed horses in the Gran Premio de Madrid—run on Saturday, June 25th at Madrid’s La Zarzuela racetrack—will qualify for ‘black type’ in sales catalogues. This follows a decision by the European Pattern Committee (EPC) to approve a new ‘flagship race’ scheme designed to give ‘emerging’ EMHF racing nations a leg up in their quest for international recognition of their best races.

When news of the decision broke, the deadline for entries for this historical race—run on turf for three-year-olds and up, over 2,500 metres with a prize fund of €68,000—was days away. So, the track extended the deadline by a few days, while its new status was publicised. This paid dividends, with two additional entries received from Great Britain and France. There is still ‘room at the inn’, there being a Supplementary Entry stage on June 20th.

La Zarzuela’s director-general, Alvaro Gutierrez

La Zarzuela’s director-general, Alvaro Gutierrez, gave his reaction to the development: “For La Zarzuela, who have just celebrated 80 years since opening, and for the whole Spanish horseracing industry—to get back a Black Type race means a lot. We have been working over recent years to be more international and develop our races in quality and level. We have very good tracks and very good professionals that demonstrate, whenever they compete abroad, the quality of our horses. Our local Category A races are really well-situated in prize money terms. We deserve to be recognised by IFHA again with a Black Type race—it will help us to continue developing and improving our horse racing program.”

The Spanish Jockey Club’s Paulino Ojanguren, an EMHF executive council member, agrees: “Black Type races mean good horses, good trainers and good jockeys; and that is what people want to see at the racetrack. A race like the Gran Premio de Madrid is a very good reason to attend the meeting and also a reward for everybody who has been involved in horse racing during the last difficult years.”

La Zarzuela is certainly a striking racecourse. Its signature ‘rippled’ grandstand roof, designed way back in the 1930s by pioneering structural engineer Eduardo Torroja, seems to float almost weightlessly above you. But how does its grass track ride?

“La Zarzuela is one of the most beautiful racetracks in Europe”, says Gutierrez. “It is a monument in its own right, which is in the running for World Heritage by UNESCO on the strength of its architecture and legacy. Also, the facilities are really good and the turf track always has the best of care. Horses here need to be fast because the pace normally is strong, they normally need to be suited by fast ground and to be tough, as the 3-furlong final straight is demanding, with the last furlong uphill. So, in essence, quality horses appreciate our racetrack.

“In 2020, before COVID started, we organised an international female jockeys championship and the feedback from jockeys and trainers was universally really good about our facilities and organisation. Prize money payments are made within 21 days. That’s why we have been visited in recent years by international horses and trainers, such as: Carlos Laffon-Parias, Mauricio Delcher-Sanchez, Christophe Ferland, Andrew Balding, Ed Dunlop, Jean-Laurent Dubord and Nicolas Caullery.”

So, what exactly is this ‘flagship race’ policy, how did it come about and what does it mean for other smaller European racing nations?

Jason Morris

Europe has long led the way when it comes to the quality control of its pattern. It laudably applies the rules by which races are designated Group I, II or III or Listed with a strictness that is unparalleled around the world. But there has long been the feeling that, for those countries without Black Type races, this makes entry into the Black Type ‘club’ unduly difficult. In recent years, the EMHF has been inching closer to finding a proposal that ‘squares this circle’ to the EPC’s approval. It was Jason Morris, racing director at Horse Racing Ireland and newly appointed chair of the EPC, who came up with the formula which got the idea over the line and met with unanimous EPC support. He explains:

“The EPC supported a proposal from Ireland to take supportive action for the development of racing in the smaller EMHF racing nations. Growing the importance of racing in more EMHF countries will potentially produce political, promotional and commercial benefits for the industry throughout Europe. Helping to stimulate interest in racing in more European countries, improving the quality and standards of the racing and breeding industries within a broader swathe of the EMHF, growing potential export and ownership markets, and encouraging greater international participation and political recognition are all potential benefits.”

“Leading the way in quality control will remain the EPC’s strong ambition. However, pushing for that objective should not prevent us from assisting the development of the smaller EMHF countries. So, in order to move forwards, the EPC agreed to adopt a more liberal approach and agree to a lower Listed rating requirement on the basis that this would only apply to one race per smaller country.”

The full criteria are these:

An emerging country must adhere to basic EMHF-defined administration/integrity standards and be a member of the EMHF.

A maximum of one qualifying race is permitted per emerging country which qualifies on the basis of a lower rating parameter/tolerance level.

This lower parameter/tolerance level is 5 lbs below the normal Listed race levels (i.e., 95 lbs, rather than 100 lbs, with the exception of fillies/mares and two-year-old races, where the thresholds are lower).

A race from an emerging country must have achieved this required (lower) rating at least twice in the past three years, meaning that races must have been run at least twice.

The race’s prize fund must be a minimum of €50,000.

A qualifying race is given three years to establish itself before being subject to review and could be downgraded if falling below the lower ‘exceptional’ parameter/tolerance level thereafter (with the general principle being that it must either achieve the 5-lb lower average race rating over three years or the annual rating in two years out of the three renewals).

If a country wishes to seek Listed status for more than one race or Group status for any race, all Black Type races from that country must meet the full normal rating parameters; and the country would then become an associate member of the European Pattern Committee.

Trainers can thus get a good handle on the likely winnability of these Black Type races from knowing that the average rating of the first four home over recent renewals will have been between 95 and 100.

“An aspiration for the EPC”, Morris continues, “would be that the award of Listed status to one race would serve as a catalyst to improve their race programme and horse population, hopefully propelling them to become associate members in time (allowing more than one race to achieve Listed status if reaching the standard rating parameters).”

No fewer than five countries made applications under the new scheme, despite having only a few weeks in which to do so. In this, the first year, Spain was the only country whose chosen race rated highly enough, but it is our strong hope that, with more time in which to plan, other countries will be successful in the future.

“It is very pleasing that Spain has already been able to achieve the required level for Listed status to be awarded to the Gran Premio de Madrid and that several other countries were keen to put forward races, which will hopefully qualify for future consideration. The EPC will work with the respective rating authorities on trying to standardise their rating file levels with European norms to facilitate future evaluations.”

“An emerging country with aspirations for a race to be awarded Listed status by the EPC, but not yet achieving the rating requirements, will hopefully take encouragement to target the key race(s) within their jurisdiction for the future with enhanced prize money and promotion to boost the quality of the races. For races in an emerging country to be successful, strong communication of the opportunities internationally and incentives to encourage high quality overseas participation will be important.”

This European scheme could form a blueprint for the development of smaller racing nations in other regions of the globe. Your correspondent represents emerging countries on the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities’ Executive Council, and discussions with counterpart ‘ExCo’ member for the Asian Racing Federation, Bruce Sherwin of New Zealand, have revealed an interest in its adoption in Asia as well.

Racecourse Fracture Support System

By Ian Wright

Figure 1: The fracture support system is provided in two mobile impact-resistant carrying boxes that protect the equipment and allow it to be checked before racing. All boots and splints are permanently labelled with individual racecourse identification to ensure return of equipment that may have left the racecourse.

The year 2022 heralds a major step forward in racehorse welfare and a world first for British racecourses. With a generous grant from the Racing Foundation and additional support from the RCA, ARVS and NTF, all British racecourses are to be provided with fracture support systems (Figure 1). These consist of two compression boots and two flexion splints—both for use in the forelimbs—and a set of aluminium modular adjustable splints. One size of each compression boot and flexion splint fits the majority of flat racehorses and the other larger jump racehorses. Together, these provide appropriate rigid external support for the vast majority of limb fractures that occur during racing. The general principles are that management of all fractures is optimised by applying rapid and appropriate support to provide stability, reduce pain and relieve anxiety.

In the last 25 years, there have been major improvements in fracture treatment due to significant advances in surgical techniques (particularly with internal fixation), minimally invasive approaches (arthroscopy) and the use of computed tomography (CT). Arthroscopy and CT allow accurate mapping and alignment of fractures, which is important for all horses and critical for athletic soundness. All have contributed to improving survival rates; and it is now safe to say that with correct care, the vast majority of horses that sustain fractures in racing can be saved. Equally importantly, many can also return to full athletic function including racing.

Fracture incidences and locations vary geographically and are influenced by race types, track surfaces and conditions. There is good evidence that the majority of non-fall–related fractures (i.e., those occurring in flat racing and between obstacles in jump racing) are caused by bone fatigue. This is precipitated by the absolute loads applied to a bone, their speed/frequency and the direction of force application. As seen with stress or fatigue, failure in other high-performance working materials such as aeroplanes or formula one cars—in which applied forces are relatively consistent—fractures in racehorse bones occur at common sites, in particular configurations and follow similar courses. Once the fracture location has been identified, means of counteracting forces that distract (separate) the bone parts can therefore be reliably predicted and countered.

Worldwide, the single most common racing fracture is that of the metacarpal/metatarsal condyles (condylar fracture). In Europe, the second most common fracture is a sagittal/parasagittal fracture of the proximal phalanx (split pastern). Both are most frequent in the forelimbs. In the United States, particularly when racing on dirt, fractures of the proximal sesamoid bones (almost always in the forelimbs) are the most common reason for on-course euthanasia. They occur less frequently when racing on turf but are seen at increased frequency on all-weather surfaces in the UK.

There is no specific data documenting outcomes of horses with sustained fractures on racecourses. However, there is solid data for the two commonest racing injuries. The figures below are a meta-analysis of published data worldwide.

CONDYLAR FRACTURES

Repaired incomplete fractures; 80% returned to racing

Complete non-displaced fractures; 66% of repaired fractures returned to racing

Displaced fractures; 51% raced following repair

Propagating fractures; 40% raced following repair

SPLIT PASTERN

Short incomplete fractures; 65% returned to racing

Long incomplete fractures; 61% returned to racing

Complete fractures; 51% returned to racing

Comminuted fractures in most circumstances end racing careers but with appropriate support and surgical repair, many horses can be saved. There is only one comprehensive series of 64 cases in the literature of which 45 (70%) of treated cases survived.

Figure 2: Newmarket Compression Boot.