Graded Stakes Winning Owners - Kris Chandler (Spirit of Makena)

Article by Bill Heller

Spirit of Makena wins the 2023 Triple Bend Stakes at Santa Anita.

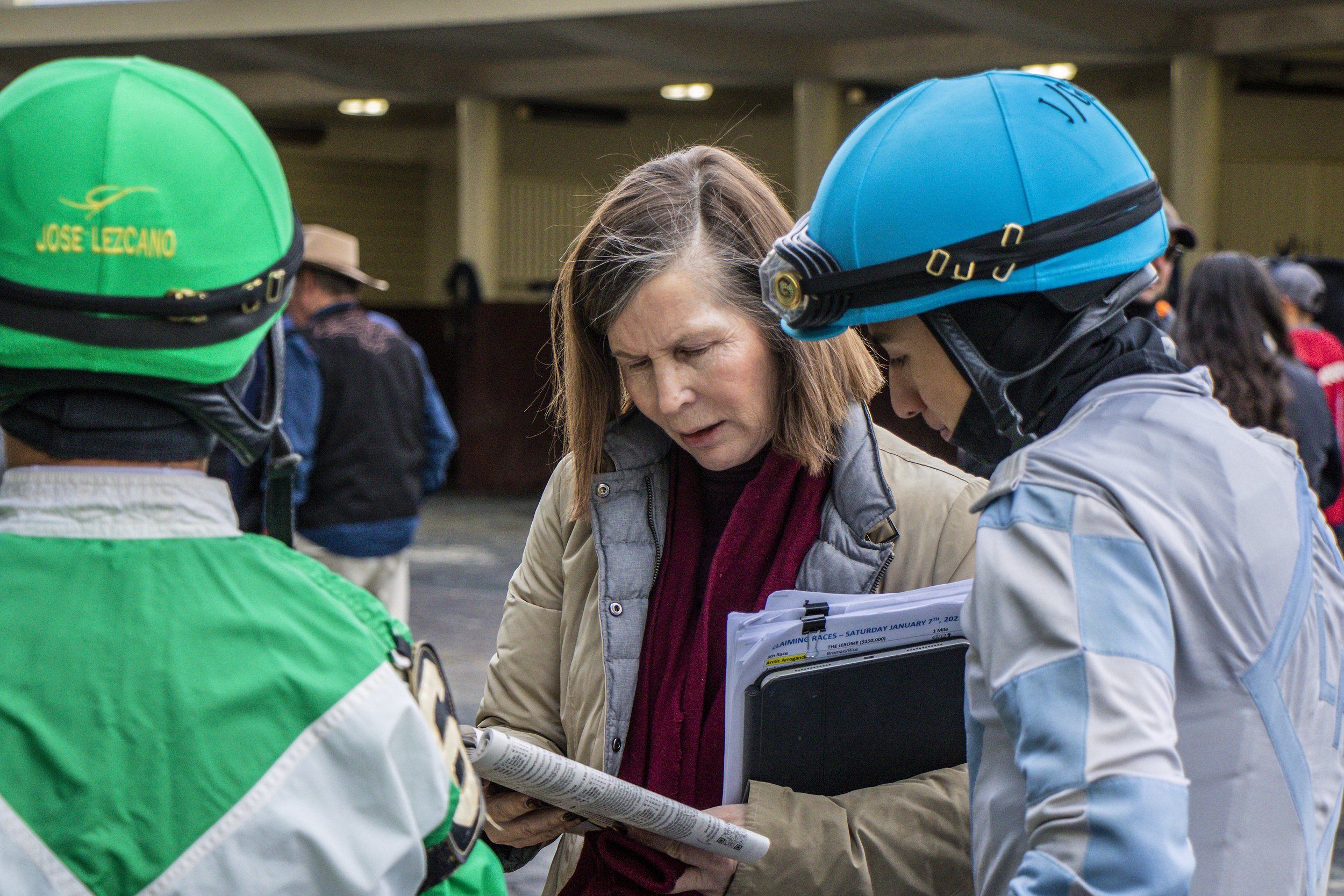

When Kris Chandler’s five-year-old horse Spirit of Makena, owned and bred by her recently-deceased husband Bruce, captured the Grade 3 San Carlos Stakes at Santa Anita, March 1st, in his stakes debut, Kris Chandler watched on TV. When trainer George Papaprodromou pointed Spirit of Makena to the Grade 2 Triple Bend Stakes at the same track May 27th, Chandler decided to watch the race in person. “It was the first time I went to the track in four years,” Chandler said.

It was worth the wait. Spirit of Makena won the Triple Bend by a length and a quarter under Joe Bravo, making him four-for-five lifetime. “It was emotional on a lot of levels,” Chandler said. “Horse racing was his passion, and he waited a lifetime for this. He had horses for over 40 years and never had a horse like this. So it’s beyond special.”

Patience allowed Spirit of Makena to develop. A variety of issues delayed his career debut until August 5th, 2022, when he won by 2 ¼ lengths as a four-year-old. A head loss finishing second in an allowance race has been his only blemish. Working around quarter cracks, Spirit of Makena won an allowance race before tacking on a pair of graded stakes victories.

The one with Chandler there was unforgettable. “She was very happy, very emotional,” Papaprodromou said. “She wished Bruce was there with her. I got to meet Bruce. They’re great people and he’s a nice horse. I’m grateful to train a horse like that and I would like to thank the owners for giving me a horse like that. It’s great to train for them. We are looking forward to a nice future with him.”

That future will help Chandler move on with her life after losing Bruce last October 16th, the day before their anniversary, following a four-year battle with cancer. “I met Bruce in Maui in Hawaii 26 years ago,” Chandler said. “Bruce and I did horses together. I’ve always loved horses, since I was a little kid, with my dad.”

Bruce Chandler’s family owned The Los Angeles Times and its parent, the Times Mirror Company, for decades.

Kris Chandler got more involved with her husband’s horses over the years. “Because I paid attention to the breeding,” she said. “He named me Director of Breeding. That was his title for me. He was breeding to horses in California. I convinced Bruce to breed to Ghostzapper (in Kentucky). I said, 'This is a great sire.’ I convinced him that if you want to get a good horse, you must breed to a good horse.

Spirit of Makena’s dam, Win for M’lou by Gilded Time, was bred by the Chandlers and named for Kris’s mom. “My mom got so excited,” Chandler said. “She was going to be famous.”

Somewhat. Win for M’lou became the Chandler’s first $100,000 winner ($115,230), surpassed only by Mai Tai ($140,405). Spirit of Makena has taken the Chandlers to a new level, having already earned $347,600 in just five starts.

Unfortunately, Spirit of Makena took forever to make it to the races. And Bruce became ill. “He got sick in 2019,” Chandler said. “He wanted to keep going. Our favorite place in the world is Maui, and part of it was because he had to live there the past few years. I’ve been taking care of my husband for the last four years. His mobility got worse and he couldn’t travel. Horse racing was the only thing he could watch. It’s still emotional being without him right now.”

She’s had and still has a ton of support from her Hawaiian community. She lives on Makena Road in Makena. “Everyone in Hawaii is behind the horse,” Chandler said. “The McKenna Golf and Beach Club are like family. The general manager, Zak Fahmie, sent a letter to all the members about this horse, a once-in-a-lifetime horse. He’s kind of like a miracle horse. We didn’t think he was going to get to the racetrack. He was at the farm in California for two years. For him to be a horse like this, it’s a miracle. From being so injured to being such a great horse. It’s a great story. We took our time with him. He’s getting better. He’s just a wonderful horse, very intelligent. You can pet him.”

Spirit of Makena keeps her and her husband connected. Initially, after her husband passed, Chandler thought she was going to get out of racing. Now she has a horse who may take her to the Breeders’ Cup Sprint at his home track, Santa Anita. “I’m trying to get out, but this is getting me very excited,” she said. “Having a horse like this, I kind of feel Bruce’s spirit. I think he just knows.”

Walter Rodriguez

Article by Ken Snyder

We see them every day in the news—men, women and children trudging north across Mexico, searching for a brighter future in the best bet on the globe: the United States. For most Americans, we don’t foresee them winning that bet like our ancestors did generations ago. The odds against them are huge.

But long shots do come in.

Walter Rodriguez was 17 years old when he pushed off into the Rio Grande River in the dark from the Mexican bank, his arms wrapped around an inner tube to cross into the U.S. The year was 2015, which differs from 2023 only in scale in terms of illegal immigration. He crossed with two things: the clothes on his back and a desire to make money he could send home. How he ended up making money and yes, quite a bit of it at this point, meant overcoming the longest odds imaginable and, perhaps, a lot of divine intervention.

Getting here began with a long six-week journey to the border from Usulutan, El Salvador, conducted surreptitiously and not without risk and a sense of danger.

His family paid $5,000 to a “coyote” (the term we’ve all come to know for those who lead people to the border).

“They would use cars with six or eight people packed in, and we would drive 10 hours. We’d stay in a house. Next morning, they would drive again in different cars, like a van; and there would be more people in it.”

Three hours into a trek through South Texas brush after his river crossing, the border patrol intercepted him. He first went to jail for several days. After that, he was flown to a detention center for illegally migrating teenagers in Florida with one thread tying him to the U.S. and preventing deportation: an uncle in Baltimore. After a month there and verification that his uncle would take him in, Walter flew to Baltimore and his uncle’s home in Elk Ridge, Maryland. From El Salvador, the trip covered about 3,200 miles.

He worked in his uncle’s business, pushing, lifting and installing appliances, doing the work of much larger men despite his diminutive size. More than a few people marveled at his strength. Ironically, and what he believes divinely, more than a few people unknowingly prophesied what was to come next for Rodriguez. Particularly striking and memorable for Walter was an old man at a gas station who looked at him and said twice. “You should be a jockey.”

For Walter, the counsel was more than just a chance encounter with a stranger. It is a memory he will carry his whole life: “This means something. I think God was calling me.”

Laurel Park just happened to be 15 minutes from where Rodriguez lived in Elk Ridge.

Whether by chance or divine intervention, the first person Rodriguez encountered at Laurel was jockey J.D. Acosta. Walter asked in Spanish, his only language at the time, “Where can I go to learn how to ride? I would like to ride horses.”

He couldn’t have gotten better direction. “I’ve got the perfect guy for you,” said Acosta. That was Jose Corrales, who is known for tutoring and mentoring young jockeys—three of whom have won Eclipse Awards as Apprentice of the Year and a fourth with the same title in England. That was Irish jockey David Egan who spent a winter with Corrales in 2016 before returning to England. He piloted Mishriff to a win in the 2021 Saudi Cup.

“This kid—he came over out of the blue to my stable,” recalled Corrales. “He said, ‘I’m so sorry. Somebody told me to come and see you and see if maybe I could become a jockey.’”

Corrales sized up Rodriguez as others had, echoing what others had told him: “You look like you could be a jockey.”

The journey from looking like a jockey to a license, however, was a long one; he knew nothing about horses or horse racing.

Perhaps surprisingly for someone from Central America, where horses are a routine part of the rural landscape, Rodriguez was scared of Thoroughbreds.

He began, like most people new to the racetrack, hot walking horses after workouts. Corrales also took on the completion of immigration paperwork that had begun with Rodriguez’s uncle.

His first steps toward becoming a rider began with learning how to properly hold reins. After that came time on an Equicizer to familiarize him with the feel of riding. The next step was jogging horses—the real thing.

“He started looking good,” said Corrales.

“I see a lot of things. I told him, ‘You’re going to do something.’”

Maybe the first major step toward becoming a jockey began with the orneriest horse in Corrales’ barn, King Pacay.

“I was scared to put him on,” said Corrales. In fact, the former jockey dreaded exercising the horse, having been “dropped” more than a few times by the horse.

Walter volunteered for the task. “Let me ride him,” Corrales remembered him saying before he asked him, “Are you sure?”

Maybe before the young would-be jockey could change his mind, Corrales quickly gave him a leg up.

“In the beginning, he almost dropped him,” said Corrales, “but he stayed on and he didn’t want to get off. He said, ‘No, I want to ride him.’”

“It was like a challenge I had to go through,” said Rodriguez, representing a life-changer for him—a career as a jockey or a return to his uncle’s business and heavy appliances.

The horse not only helped him overcome fear but gave him the confidence to do more than just survive a mean horse.

“I started to learn more of the control of the horses from there.”

Using the word “control” is ironic. In Rodriguez’s third start as a licensed jockey, he won his first race on a horse he didn’t control.

“To be honest, I didn’t know what I was doing. I just let the horse [a Maryland-bred filly, Rationalmillennial] do his thing. I tried to keep her straight, but I didn’t know enough—no tactics, none of that. We broke from the gate, and I just let the horse go.”

Walter Rodriguez receives the traditional dousing from fellow jockey Jorge Ruiz after winning his first career race at Laurel Park, 2022.

It was the first of 11 victories in 2022 in six-and-a-half months on Maryland tracks and then Turfway Park in Kentucky. Earnings were $860,888 in 2022; and to date, at the time of writing not quite halfway through the year, his mounts have earned a whopping $2,558,075. Most amazing, he led Turfway in wins during that track's January through March meet with 48. He rode at a 19% win rate.

Next was a giant step for Rodriguez: the April Spring meet at Keeneland, which annually draws the nation’s best riders.

He won four races from 39 starts. More significant than the wins, perhaps, is the trainer in the winner’s circle with Rodriguez on three of those wins: Wesley Ward.

How Ward came to give Rodriguez an opportunity goes back to 1984, the year of Ward’s Eclipse Award for Outstanding Apprentice. One day on the track at Belmont, he met Jose Corrales. On discovering Corrales was a jockey coming off an injury and battling weight, Ward encouraged him to take his tack to Longacres in Seattle. The move was profitable, leading to a career of over $4.4 million in earnings for Corrales and riding stints in Macau and Hong Kong.

The brief exchange on the racetrack during workouts began a friendship between Corrales and Ward that continued and is one more of those things that lead to where Rodriguez is today as a jockey.

Corrales touted Rodriguez to Ward, who might be the perfect trainer to promote an apprentice rider. Ward’s success as a “bug boy” eliminates the hesitation many of his owners might have against riding apprentices.

He might be the young Salvadoran’s biggest fan.

“I can’t say enough good things about that boy. He’s a wonderful, wonderful human being and is going to be a great rider.”

He added something that is any trainer’s sky-high praise for a jockey: “He’s got that ‘x-factor.’ Horses just run for him.”

Corrales, too, recognizes in Rodriguez a work ethic in short supply on the race track. “A lot of kids, they want to come to the racetrack, and in six months they want to be a jockey. They don’t learn horsemanship,” said Corrales. “You tell Walter to do a stall, he does a stall. You tell him to saddle a horse, he saddles the horse. He learns to do what needs to be done with the horses.

“He’s got the weight. He’s got the size. He’s got a great attitude. He works hard.”

Ward was astonished at something the young man did when one of his exercise riders didn’t show up at Turfway one morning: “He was leading rider at the time but got on 15 horses that morning and that’s just one time.“ Ward estimated Rodriguez did the same thing another 25 times.

“He’ll do anything you ask; he’s just the greatest kid.”

Ward recounted Rodriguez twice went to an airport in Cincinnati to pick up barn workers flying back to the U.S. from Mexico to satisfy visa requirements. “He’d pick them up at the airport from the red-eye flight at 4:30 in the morning and then drive them down to work at Keeneland.”

Walter on Wesley Ward’s Eye Witness at Keeneland.

With Rodriguez’s success, talent is indisputable, but Corrales also credits a strong desire to reach his goal combined with an outstanding attitude. Spirituality, too, is a key attribute developing in extraordinary circumstances in his home country.

When Rodriguez was three years old, his father abandoned him and his mother. As for her, all he will say is, “She couldn’t raise me.” His grandmother, Catalina Rodriguez, was the sole parent to Rodriguez from age three.

He calls his grandmother “three or four times a week,” and she knows about his career, thanks to cousins that show her replays of his races.

Watching him leave El Salvador was difficult for her, but she saw it as necessary to the alternative. He credits her for giving him “an opportunity in life. Otherwise, I would be somebody else, doing bad things back at home.”

Surprisingly, her concerns for her grandson in the U.S. were more with handling appliances than 1,110-pound Thoroughbreds.

“When I was working with my uncle, she wasn’t really happy; she wasn’t sure about what I was doing.

“But I kept saying to her, let’s have faith. Hopefully, this is going to be okay. Now she realizes what I was saying.”

His faith extends to the latest in his career: riding at Churchill Downs this summer. “One day I got on my knees and I said to God, ‘Please give me the talent to ride where the big guys are.’“

Gratitude is another quality that seems to come naturally for Rodriguez. After the Turfway Park meet at the beginning of April, he flew back to Maryland to provide a cookout for everybody in Jose Corrales’s barn.

He also sends money to El Salvador, not only to his grandmother but to help elderly persons he knows back home. During the interview, he showed pictures of food being served to people in his village at his former church. At least a significant portion of that is financed by Rodriguez’s generosity.

“I love to help people. It will come back to you in so many ways. I’ve seen how it came back to me.”

According to Corrales, there have been discussions about a possible movie on Rodriguez, who just received his green card in June of this year.

“These days with immigration, crossing the border and all the trouble we’re having—to have somebody cross the border and have success, it’s a blessing,” Corrales said.

A blessing, for sure, but one that was meant to be. Walter encapsulated his journey and what happened after he went to Laurel Park with a passage from a psalm in the Bible: “The steps of a good man are ordered of the Lord.”

Celebrating breeders - Howie Walton

Article by Bill Heller

Howie Walton has spent his life in Toronto loving horses, riding, racing and breeding them.

“He absolutely loves his horses,” one of his trainers, John Mattine, said. “When someone has that passion for the game, you want to do well for him and succeed.”

Walton succeeded beyond his wildest imagination in business, starting his own plastics company, Norseman Plastics, and selling it for millions. That allowed him to follow his heart and make good on a promise to himself. “As a kid, I always loved horses. I said if I ever did well, I’d buy a horse.”

He bought a riding horse, Lakeview Noel, who lived to be 31 years old. Then Howie bought Quarter Horses, doing quite well with them, and switched to Thoroughbreds—making an enormous impact on Canadian racing.

“He’s great for the sport,” another one of his trainers, Jamie Attard, said. “He really is. He’s a breeder’s breeder and an owner’s owner. He’s been supporting Ontario racing for so many years.”

There are rewards for doing so, specifically for Ontario-breds and its rich supplement program. “The bonuses for Ontario-breds are fairly high,” said Walton. “I’ve always raced at Woodbine. I’ve been there a long time.”

Along the way, his concern for his horses has never wavered. “We had a horse,” recalls Attard. “His name was Buongiorno Johnny. He broke his maiden in a stakes race (winning the $150,000 restricted Vandal Stakes July 31, 2011), then he had an issue down the line. We lost the horse for $32,000 (on June 25, 2014). Three years later, he was in some bottom-level claimer (a $4,000 claimer at Thistledown). Howie paid them double the claiming price and retired him on his farm. He always lets you do what is right. If it’s the little thing, he’ll send him to the farm for some time off. He retired a six-year-old we had and gave it to my girlfriend. The horse always comes first. His heart is as big as the grandstand.”

Jamie Attard’s father, Canadian Hall of Famer Sid, also trains for Walton and echoes his son’s opinion: “If a horse is not right, he doesn’t want to run him. If I call up saying his horse has a problem, he’ll say, `Scratch him.’”

Howie Walton (blue jacket) receives the 2022 Recognition of Excellence Award at the recent 39th Annual CTHS Awards from CTHS Ontario President & National Director Peter Berringer.

There are worse calls ro receive. Sid and Howie know first-hand. Their two-year-old home-bred filly, A Touch of Red, a daughter of Howie’s top horse and now leading stallion Signature Red, won her debut by five lengths at Woodbine in a maiden $40,000 claimer last September 19. On October 10, she won the $100,000 South Ocean Stakes for Ontario-breds by a neck as the even-money favorite.

“She was breezing seven days before her next race,” Sid said. “She worked by herself that day. She’s going five-eighths. Good bug boy on her. He noticed something wrong. He pulled her up. She started shaking. She died. Looked like a heart attack. She was such a nice, nice filly. Beautiful. Big. Strong. I was never so shocked in my life.”

Sid called Howie and told him the tragic news. “I said, `Howie, I’m very, very sorry.’”

Walton replied, “Sid, don’t worry about nothing. It’s nobody’s fault.”

He and Sid have another talented filly who just turned three, another home-bred daughter of Signature Red, Ancient Spirit. She won a maiden $40,000 claimer by four lengths, the $100,000 Victoria Queen Stakes by 2 ½ and concluded her two-year-old season with a second by a neck in the South Ocean Stakes to her stable-mate, A Touch of Red. The torch has been passed on.

A couple months after A Touch of Red’s death, Walton said, “In this game, you have good-luck and bad-luck horses. She won a stakes race and had a heart attack and died.”

As if that wasn’t bad enough, Howie then endured the removal of his gallbladder. ”It wasn’t fun,” he said. He leaned on his family, his wife of 47 years Marilyn, their adult sons Benjamin, who is 43, works for his dad with his apartment building investments; and 42-year-old Michael, who is in the plastics business. The Waltons have four grandchildren and a standard poodle named Riley. “A house isn’t a home unless you have a dog in it,” Howie said. “Poodles are as smart as hell.”

So is his owner. “I was a pretty smart guy; I went to the University of Toronto, and I was a chemical engineer. I did well with plastics.”

He did incredibly well with the company he started. “I had it for 30, 40 years,” Walton said. “It got pretty big. It was quite an operation. I had 500, 600 people under me. We had plants around the states. I had big clients: Pepsi Cola, Coca Cola, all the milk companies—you name them. It turned out to be a $230 million company. I started at zip.”

How did he do it the first time? “I worked like hell; I wasn’t married. We used to run 24 hours, seven days a week. I don’t know if I could do it again.”

Marilyn isn’t surprised that her husband succeeded. “When he does something, he puts 150 percent into it. He makes up his mind, and he’s very focused. He was a born salesman. He knows how to talk to people, how to treat people.”

She also knows how resourceful Howie can be.

Marilyn and Howie lived near each other but hadn’t met. “We used to pass each other going to work on the same day. Then one day he wrote down my license plate. In those days, you could do that and look a person up.

“We met. We were engaged in three months and married three months after that; and we’ve been married 47 years.”

Marilyn was impressed with Howie’s horsemanship. “It started with the Quarter Horses. What I really loved about it was he was not the person who goes to the races and just watches. He went to the barn and used to clean their feet after the race. He really cares for animals. He is a true animal lover. He loves dogs. Same thing with Thoroughbreds. He truly, truly loves them. He always had a passion for them.”

Signature Red (rail side) wins the 2011 Highlander Stakes.

The horse Howie Walton is most passionate about is Signature Red. “John Mattine’s dad, Tony, picked out Signature Red," recalled Howie. (Red is Howie’s favorite color.)

John said, “My father trained for him. He was basically his first trainer. My dad bought everything for him before. Most of the good broodmares he has trace back to my dad.”

Racing from the age of three until he was six, Signature Red, a son of Bernstein out of Irish and Foxy by Irish Open, won six of 27 starts, including two consecutive runnings of the Gr. 2 Highlander Turf Stakes in 2010 and 2011, and earned $630,232.

Buongiorno Johnny before his 2011 Vandal Stakes win.

He stands at Frank Stronach’s Adena Springs in Aurora, Ontario, for C$5,000 this year and has now sired the winners of 168 races through the end of 2022. His progeny has earned more than C$6.2 million.

“I think he’s the best value stud in Canada,” says Walton. Accordingly, he has continually sent his best mares to Signature Red. “I believe in him.”

He also believes in the value of Signature Red’s offspring. That’s why at last year’s CTHS Ontario Premier Yearling Sale, he bought back three Signature Red yearlings as well as a filly by Red Explosion, a son of Signature Red, for a combined total of C$290,000. “Not really a hard decision,” said Walton. “My stock is very high quality. I believe in my stock. I believe in my stud.”

Howie has become friends with Adena’s farm manager Sean Smullen and farm owner Frank Stronach. “In 2002, he started putting some horses in here—layups. We developed a good relationship over the years. The man—he loves his animals. No matter what’s wrong, he’ll do it to save the animal. There’s no expense too big to care for his horse. He wants to give it a quality of life. He’s very loyal,” says Smullen.

Walton cherishes his friendship with Frank Stronach. “I’ve known him for a long time. He’s a dynamic guy. Anyone building an electric car plant at the age of 90 … there aren’t many guys like him. As a businessman, I admire that. I told him that. He said, `I guess I’ve made a few billion in my life.’ He’s quite a guy. I hope he lives to be 200. When he’s gone, I don’t know who’s going to run his operation. When he had his tiff with his daughter, he told me, `Howie, it’s only money. I’ll make more.’”

One of Walton’s home-breds made quite a bit of money out of just six starts before being sold. Maritimer, trained by Sid Attard, won his maiden debut by a head and then finished second by a head to his stable-mate Buongiorno Johnny in that 2011 Vandal Stakes. Maritimer then finished second in an allowance race, a late-tiring fourth in the Gr. 3 Summer Stakes and first in two stakes: the $250,000 Coronation Futurity by 2 ½ lengths then the $175,000 Display by 5 ½ lengths. After being sold, he went winless in four starts, including fifth in the Gr. 2 Autumn Stakes at Woodbine. He failed to hit the board in three starts in Dubai, including an 11th in the Gr. 2 U.A.E. Derby.

Though he concentrates on Thoroughbreds, Walton still has Quarter Horses. “What attracted me was the horse. They were big. They were strong. They were smart and beautiful. Not as edgy as a Thoroughbred. I still have a few.”

He treats them the same way he treats Thoroughbreds. And the same way he treats people: love, loyalty and a laser-like focus. “I am a loyal guy,” he said. “If I don’t like you, I’ll tell you.”

Marilyn put it this way: “What you see is what you get.”

Howie Walton and trainer Sid Attard with Generous Touch and jockey Eurico Rosa da Silva.

Air Quality and Air Pollution’s Impact on Your Horse’s Lungs

Article by Dr. Janet Beeler-Marfisi

There’s nothing like hearing a horse cough to set people scurrying around the barn to identify the culprit. After all, that cough could mean choke, or a respiratory virus has found its way into the barn. It could also indicate equine asthma. Yes, even those “everyday coughs” that we sometimes dismiss as "summer cough" or "hay cough" are a wake-up call to the potential for severe equine asthma.

Formerly known as heaves, broken wind, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), this respiratory condition is now called severe equine asthma (sEA). These names reflect how our scientific and medical understanding of this debilitating disease has changed over the years. We now consider heaves to be most comparable to severe asthma in people.

But what if your horse only coughs during or after exercise? This type of cough can mean that they have upper airway irritation (think throat and windpipe) or lower airway inflammation (think lungs) meaning inflammatory airway disease (IAD), which is now known as mild-to-moderate equine asthma (mEA). This airway disease is similar to childhood asthma, meaning that it can go away on its own. However, it is still very important to call your veterinarian out to diagnose mEA. This disease causes reduced athletic performance, and there are different subtypes of mEA that benefit from specific medical therapies. In some cases, mEA progresses to sEA.

Equine Asthma and Air Quality

What does equine asthma have to do with air quality? A lot, it turns out. Poor air quality, or air pollution, includes the barn dusts—the allergens and molds in hay and the ground-up bacteria in manure, as well as arena dusts and ammonia from urine. Also, very importantly for both people and horses, air pollution can be from gas and diesel-powered equipment. This includes equipment being driven through the barn, the truck left idling by a stall window, or the smog from even a small city that drifts nearly invisibly over the surrounding farmland. Recently, forest-fire smoke has been another serious contributor to air pollution.

Smog causes the lung inflammation associated with mEA. Therefore, it is also likely that air pollution from engines and forest fires will also trigger asthma attacks in horses with sEA. Smog and smoke contain many harmful particulates and gases, but very importantly they also contain fine particulate matter known as PM2.5. The 2.5 refers to the diameter of the particle being 2.5 microns. That’s roughly 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. Because it is so small, this fine particulate is inhaled deeply into the lungs where it crosses over into the bloodstream. So, not only does PM2.5 cause lung disease, but it also causes inflammation elsewhere in the body including the heart. Worldwide, even short-term exposure is associated with an increased risk of premature death from heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer. This PM2.5 stuff is not trivial!

In horses, we know that PM2.5 causes mEA, so it’s logical that smog and forest-fire smoke exposure could exacerbate asthma in horses, but we don’t know about heart disease or risk of premature death.

Symptoms, Diagnostic Tests and Treatments

Equine asthma manifests with a spectrum of symptoms that vary in severity and the degree of debilitation they cause. Just like in people with asthma, the airways of horses with mEA and sEA are “hyperreactive.” This means that the asthmatic horse’s airways are extra sensitive to barn dusts that another horse’s lungs would just “ignore.” The asthmatic horse’s airways constrict, or become narrower, in response to these dusts. This narrowing makes it harder to get air in and out of the lungs. Think about drinking through a straw. You can drink faster with a wider straw than a skinnier one. It’s the same with air and the airways. In horses with mEA, the narrowing is mild. In horses with sEA, the constriction is extreme and is the reason why they develop the “heaves line”; they have to use their abdominal muscles to help squeeze their lungs to force the air back out of their narrow airways. They also develop flaring of their nostrils at rest to make their upper airway wider to get more air in. Horses with mEA do not develop a heaves line, but the airway narrowing and inflammation do cause reduced athletic ability.

The major signs of mEA are coughing during or just after exercise that has been going on for at least a month and decreased athletic performance. In some cases, there may also be white or watery nasal discharge particularly after exercise. Often, the signs of mEA are subtle and require a very astute owner, trainer, groom, or rider to recognize them.

Another very obvious feature of horses with sEA is their persistent hacking cough, which worsens in dusty conditions. “Hello dusty hay, arena, and track!” The cough develops because of airway hyperreactivity and because of inflammation and excess mucus in the airways. Mucus is the normal response of the lung to the presence of inhaled tiny particles or other irritants. Mucus traps these noxious substances so they can be coughed out, which protects the lung. But if an asthma-prone horse is constantly exposed to a dusty environment, it leads to chronic inflammation and mucus accumulation, and the development or worsening of asthma along with that characteristic cough.

Accurately Diagnosing Equine Asthma

Veterinarians use a combination of the information you tell them, their observation of the horse and the barn, and a careful physical and respiratory examination that often involves “rebreathing.” This is a technique where a bag is briefly placed over the horse’s nose, causing them to breathe more frequently and more deeply to make their lungs sound louder. This helps your veterinarian hear subtle changes in air movement through the lungs and amplifies the wheezes and crackles that characterize a horse experiencing a severe asthma attack. Wheezes indicate air “whistling” through constricted airways, and crackles mean airway fluid buildup. The fluid accumulation is caused by airway inflammation and contributes to the challenge of getting air into the lung.

Other tests your veterinarian might use are endoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and in the specialist setting, pulmonary function testing. They will also perform a complete blood count and biochemical profile assay to help rule out the presence of an infectious disease.

Endoscopy allows your veterinarian to see the mucus in the trachea and large airways of the lung. It also lets them see whether there are physical changes to the shape of the airways, which can be seen in horses with sEA.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, or “lung wash” is how your veterinarian assesses whether there is an accumulation of mucus and inflammatory cells in the smallest airways that are too deep in the lung to be seen using the endoscope. Examining lung wash fluid is a very important way to differentiate between the different types of mEA, between sEA in remission and an active asthma attack, and conditions like pneumonia or a viral lung infection.

Finally, if your veterinarian is from a specialty practice or a veterinary teaching hospital, they might also perform pulmonary function testing. This allows your veterinarian to determine if your horse’s lungs have hyperreactive airways (the hallmark of asthma), lung stiffening, and a reduced ability to breathe properly.

Results from these tests are crucial to understanding the severity and prognosis of the condition. As noted earlier, mEA can go away on its own; but medical intervention may speed healing and the return to athletic performance. With sEA, remission from an asthmatic flare is the best we can achieve. As the disease gets worse over time, eventually the affected horse may need to be euthanized.

Management, Treatment and Most Importantly—Prevention

Successful treatment of mEA and sEA flares, as well as long-term management, requires a multi-pronged approach and strict adherence to your veterinarian’s recommendations.

Rest is important because forcing your horse to exercise when they are in an asthma attack further damages the lung and impedes healing. To help avoid lung damage when smog or forest-fire smoke is high, a very useful tool is your local, online, air quality index (just search on the name of your closest city or town and “AQI”). Available worldwide, the AQI gives advice on how much activity is appropriate for people with lung and heart conditions, which are easily applied to your horse. For example, if your horse has sEA and if the AQI guidelines say that asthmatic people should limit their activity, then do the same for your horse. If the AQI says that the air quality is bad enough that even healthy people should avoid physical activity, then do the same for you AND your horse. During times of poor air quality, it is recommended to monitor the AQI forecast and plan to bring horses into the barn when the AQI is high and to turn them out once the AQI has improved.

Prevent dusty air. Think of running your finger along your tack box – whatever comes away on your finger is what your horse is breathing in. Reducing dust is critical to preventing the development of mEA and sEA, and for managing the horse in an asthmatic flare.

Logical daily practices to help reduce dust exposure:

Turn out all horses before stall cleaning

Wet down the aisle prior to sweeping

Never sweep debris into your horse’s stall

Use low-dust bedding like wood shavings or dust-extracted straw products, which should also be dampened down with water

Reduce arena, paddock, and track dust with watering and maintenance

Consider low-dust materials when selecting a footing substrate

Steam (per the machine’s instructions) or soaking hay (15–30 minutes and then draining, but never store steamed or soaked hay!)

Feed hay from the ground

Feed other low-dust feeds

Avoid hay feeding systems that allow the horse to put their nose into the middle of dry hay—this creates a “nosebag” of dust

Other critical factors include ensuring that the temperature, humidity and ventilation of your barn are seasonally optimized. Horses prefer a temperature between 10–24 ºC (50–75 ºF), ideal barn humidity is between 60–70%. Optimal air exchange in summer is 142 L/s (300 cubic feet/minute). For those regions that experience winter, air exchange of 12–19 L/s (25–40 cubic feet/minute) is ideal. In winter, needing to strip down to a single layer to do chores implies that your barn is not adequately ventilated for your horse’s optimal health. Comfortable for people is often too hot and too musty for your horse!

Medical interventions for controlling asthma are numerous. If your veterinarian chooses to perform a lung wash, they will tailor the drug therapy of your asthmatic horse to the results of the wash fluid examination. Most veterinarians will prescribe bronchodilators to alleviate airway constriction. They will also recommend aerosolized, nebulized or systemic drugs (usually a corticosteroid, an immunomodulatory drug like interferon-α, or a mast cell stabilizer like cromolyn sodium) to manage the underlying inflammation. They may also suggest nebulizing with sterile saline to help loosen airway mucus and may suggest feed additives like omega 3 fatty acids, which may have beneficial effects on airway inflammation.

New Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research is paramount to expanding our knowledge of what causes equine asthma and exploring innovative medical solutions. Scientists are actively investigating the effects of smog and barn dusts on the lungs of horses. They are also working to identify new targeted therapies, immunotherapies and other treatment modalities to improve outcomes for affected horses.

Conclusion

Both mild and severe equine asthma are caused and triggered by the same air pollutants, highlighting the need for careful barn management. The alarming rise in air pollution levels poses an additional threat to equine respiratory health. Recognizing everyday coughs as potential warning signs and implementing proper diagnostic tests, day-to-day management practices and medical therapies are crucial in combating equine asthma. By prioritizing the protection of our horse’s respiratory health and staying informed about the latest research, we can ensure the well-being of our equine companions for years to come.

Highlights

Work to prevent dust and optimize barn air exchange.

Avoid idling farm equipment and trucks around horses.

Don’t ignore a cough—call your veterinarian.

Monitor your local air quality index—it’s a free and simple way to help prevent lung damage!

Thermoregulation - Too hot to handle!

Article by Adam Jackson MRCVS

Exertional heat illness (EHI) is a complex disease where thoroughbred racehorses are at significant risk due to the fact that their workload is intensive in combination with the high rate of heat production associated with its metabolism. In order to understand how this disease manifests and to develop preventative measures and treatments, it is important to understand thermoregulation in horses.

What is thermoregulation?

With continuous alteration in the surrounding temperature, thermoregulation allows the horse to maintain its body temperature within certain limits. Thermoregulation is part of the greater process of homeostasis, which is a number of self-regulating processes the horse uses to maintain body stability in the face of changing external conditions. Homeostasis and thermoregulation are vital for the horse to maintain its internal environment to ensure its health while disruption of these processes leads to diseases.

The horse’s normal temperature range is 99–101°F (37.5–38.5°C). Hyperthermia is the condition in which the body temperature increases above normal due to heat increasing faster than the body can reduce it. Hypothermia is the opposite condition, where the body temperature decreases below normal levels as the body is losing heat faster than producing it. These conditions are due to the malfunction of thermoregulatory and homeostatic control mechanisms.

Horses are colloquially referred to as warm-blooded mammals—also known as endotherms because they maintain and regulate their core body, and this is opposite ectotherms such as reptiles. The exercising horse converts stored chemical energy into mechanical energy when contracting various muscles in its body. However, this process is relatively inefficient because it loses roughly 80% of energy released from energy stores as heat. The horse must have effective ways to dissipate this generated heat; otherwise, the raised body temperatures may be life threatening.

Transfer of body heat

There are multiple ways heat may be transferred, and this will flow from one area to another by:

1. Evaporation

The main way body heat is lost during warm temperatures is through the process of evaporation of water from the horse’s body surface. It is a combination of perspiration, sweating and panting that allows evaporation to occur.

Sweating is an inefficient process because the evaporation rate may exceed the body heat produced by the horse, resulting in the horse becoming covered and dripping sweat. This phenomenon occurs faster with humid weather (high pressure).

Insensible perspiration is the loss of water through the skin, which does not occur as perceivable sweat. Insensible perspiration takes place at an almost constant rate and is the evaporative loss from skin; but unlike sweating, the fluid loss is pure water with no solutes (salts) lost. The horse uses insensible perspiration to cool its body.

It is not common for horses to pant in order to dissipate heat; however, there is evidence that the respiratory tract of the horse can aid in evaporative heat loss through panting.

2. Conduction

Conduction is the process where heat is transferred from a hot object to a colder object, and in the case of the horse, this heat transfer is between its body and the air. However, the air has poor thermal conductivity, meaning that conduction plays a small role in thermoregulation of the horse. Conduction may help if the horse is lying in a cool area or is bathed in cool water.

The horse has the greatest temperature changes occurring at its extremities, such as its distal limbs and head. The horse can alter its blood flow by constricting or dilating its blood vessels in order to prevent heat loss or overheating, respectively.

Interestingly, the horse will lie down and draw its limbs close to its body in order to reduce its surface area and to control conduction. There also have been some adaptive changes in other equids like mules and burros, where shorter limbs, longer ears and leaner bodies increase its surface area to help in heat loss tolerance.

3. Convection

Convection is the rising motion of warmer areas of a liquid or gas and the sinking motion of cooler areas of the liquid or gas. Convection is continuously taking place between the surface of the body and the surrounding air. Free convection at the skin surface causes heat loss if the temperature is low with additional forced convective heat transfer with wind blowing across the body surface.

When faced with cold weather, a thick hair coat insulates and resists heat transfer because it traps air close to the skin; thus, preventing heat loss. Whereas, the horse has a fine hair coat in the summer to help in heat loss.

4. Radiation

Radiation is the movement of heat between objects without direct physical contact. Solar radiation is received from the sun and can be significant in hot environments, especially if the horse is exposed for long periods of time. A horse standing in bright sunlight can absorb a large amount of solar radiation that can exceed its metabolic heat production, which may cause heat stress.

How the horse regulates its body temperature

The horse must regulate its heat production and heat loss using thermoregulatory mechanisms. There are many peripheral thermoreceptors that detect changes in temperature, which leads to the production of proportional nerve impulses. These thermoregulators are located in the skin skeletal muscles, the abdomen, the spinal cord and the midbrain with the hypothalamus being instrumental in regulating the internal temperature of the horse. A coordinating center in the central nervous system receives these nerve incoming impulses and produces output signals to organs that will alter the body temperature by acting to reduce heat loss or eliminate accumulated heat.

The racehorse and thermoregulation

The main source of body heat accumulation in the racehorse is associated with muscular contraction. At the initiation of exercise, the racehorse’s metabolic heat production, arising from muscle contraction, increases abruptly. The heat production does alter the level of intensity of the work as well as the type of exercise undertaken.

During exercise, the core body temperature increases because heat is generated and the horse’s blood system distributes this heat throughout the body. Hodgson and colleagues have theorized and confirmed via treadmill studies that the racehorse has the highest rate of heat production compared to other sporting horses. In fact, the racehorse’s body temperature can rise 33°F (0.8°C) per minute, reaching 108°F (42.0°C). But what core temperature can the horse tolerate and not succumb to heat illness and mortality? The critical temperature for EHI (exertional heat illness) is not known, but studies have demonstrated that a racehorse can be found to have core temperatures between 108°F - 109° F (42–43°C) without any clinical symptoms. Currently, anecdotal evidence is only available, suggesting that a core temperature of 110°F (43.5°C) will result in manifestation of EHI with the horse demonstrating central nervous system dysfunction such as ataxia (incoordination). In addition, temperatures greater than 111°F (44°C) result in collapse.

Heat loss in horses

A horse loses heat to the environment by a combination of convection, evaporation and radiation, which is magnified during racing due to airflow across the body. However, if body heat gained through racing is not minimized by convection, then the racehorse’s body temperature is regulated entirely by evaporation of sweat. This evaporation takes place on the horse’s skin surface and respiratory tract.

The horse has highly effective sweat glands found in both haired and hairless skin, which produces sweat rates that are highest in the animal kingdom. Efficient evaporative cooling is present in the horse because its sweat has a protein called latherin, which acts as a wetting agent (surfactant); this allows the sweat to move from its skin to the hair.

Because of the horse’s highly blood-rich mucosa of its upper respiratory tract, the horse has a very efficient and effective heat exchange system. Estimates suggest this pathway dissipates 30% of generated heat by the horse during exercise. As the horse exercises, there is blood vessel dilation, which increases blood flow to the mucosa that allows more heat to be dissipated to the environment. When the respiratory tract maximizes evaporative heat loss, the horse begins to pant. Panting is a respiratory rate greater than 120 breaths per minute with the presence of dilated nostrils; and the horse adopts a rocking motion. However, if humidity is high, the ability to evaporate heat via the respiratory route and skin surface is impaired. The respiratory evaporative heat loss allows the cooling of venous blood that drains from the face and scalp. This blood may be up to 37°F (3.0°C) cooler than the core body temperature of 108°F (42.0°C). And as it enters the central circulatory system, it can significantly have a whole-body cooling effect. This system is likely an underestimated and significant means to cool the horse.

Pathophysiology of EHI in the thoroughbred

Although it is inconsistent to determine what temperature may lead to exertional heat illness (EHI), it is known that strenuous exercise, especially during heat stress conditions leads to this disease. In human medicine, this disease is recognised when nervous system dysfunction becomes apparent. There are two suggested pathways that lead to EHI, which may work independently or in combination depending on the environmental factors that are present during racing/training.

1. Heat toxicity pathway

Heat is known to detrimentally affect cells by denaturing proteins leading to irreversible damage. In general, heat causes damage to cells of the vascular system leading to widespread intravascular coagulation (blood clot formation), pathologically observed as micro thrombi (miniature blood clots) deposits in the kidneys, heart, lungs and liver. Ultimately, this leads to damaged organs and their failure.

Heat tissue damage depends on the degree of heat as well as the exposure time to this heat. Mammalian tissue has a level of thermal damage at 240 minutes at 108°F (42°C), 60 minutes at 109°F (43°C), 30 minutes at 111°F (44°C) or 15 minutes at 113°F (45°C). This heat damage must be borne in mind following a race requiring suitable and appropriate cooling methods, otherwise inadequate cooling may lead to extended periods of thermal damage causing disease.

The traditional viewpoint is that EHI is caused by strenuous exercise in extreme heat and/or humidity. However, recent studies have revealed that environmental conditions may only cause 43% of EHI cases, thus, suggesting that other factors are involved.

2. Heat sepsis pathway

In some instances. a horse suffering from EHI may present with symptoms and clinical signs similar to sepsis like that seen in an acute bacterial infection.

A bacterial infection leading to sepsis causes an extreme body response and a life threatening medical emergency. Sepsis triggers a chain reaction throughout the body particularly affecting the lungs, urinary tract, skin and gastrointestinal tract.

Strenuous exercise in combination with adverse environmental conditions may lead to sepsis without the presence of a bacterial infection— also known as an endotoxemic pathway—causing poor oxygen supply to the mucosal gastrointestinal barrier. Ultimately, the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract is compromised, allowing endotoxins to enter the blood system and resulting in exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome (EIGS).

However, researchers have observed that EHI in racehorses is unpredictable as EHI may develop in horses following exercise despite “safe” environmental conditions. Even with adequate cooling and resuscitative therapies, tissue damage that occurs demonstrates that thermoregulatory and inflammatory pathways may vary, and hyperthermia may be the trigger but may not necessarily be driving the condition.

Diagnosis of EHI

The diagnosis of EHI is based on the malfunctioning of the central nervous system.

Initially, hyperthermia reduces the blood flow to the cerebrum of the brain, leading to a decrease of oxygen to that area—also known as ischemia. As a result, the clinical signs are:

Extreme restlessness

Confusion

Substantial headache

If this hyperthermia continues, then the blood-brain barrier (an immunological barrier between circulating blood that may contain microorganisms like bacteria and viruses to the central nervous system) begins to leak plasma proteins, resulting in cerebral oedema (build up of fluid causing affected organ to become swollen). If treatment is not initiated at this point, then neuronal injury will result especially in the cerebellum.

EHI follows and involves serious CNS dysfunction. The clinical signs associated with EHI are:

Delirium

Horses unaware of their surroundings

The final stage of EHI occurs when the swollen oedematous brain compresses vital tissue causing cellular damage. The clinical signs of end-stage EHI are:

Collapse

Unconsciousness

Coma

Death

Definition of EHI

EHI most commonly occurs immediately after a race when the horse is panting, sweating profusely and may be dripping with sweat. The most reliable indication of EHI is clinical signs associated with the dysfunction of the central nervous system in the presence of hyperthermia. Researchers have provided descriptions of levels of CNS dysfunction, ranging from level 1 to level 4.

Level 1 – The earliest recognizable signs of CNS dysfunction

The horse becomes restless, agitated and irritable. There is often head nodding or head shaking. The horse is difficult to restrain and will not stand still. Therapeutic intervention such as cooling can resolve these clinical signs, but if the horse is inadequately cooled then the disease can escalate.

Level 2 – Obvious neurological dysfunction

Often misdiagnosed as colic symptoms, the horse becomes further agitated and irritable with the horse kicking out without any particular stimulus present. This stage is dangerous to all handlers involved as the horse’s behavior is unpredictable.

Level 3 – Bizarre neurological signs

At this stage, the horse has an altered mentation appearing vacant, glassy-eyed and “spaced-out”. In addition, there is extreme disorientation with a head tilt and leaning to one side with varying levels of ataxia (wobbly). It has been observed that horses may walk forward, stop, rear and throw themselves backwards. It is a very dangerous stage, as horses are known to run at fences, obstacles and people. Horses may also present as having a hind limb lameness appearing as a fractured leg with hopping on the good limb. These clinical signs may resolve with treatment intervention.

Level 4 – Severe CNS dysfunction

There is severe CNS dysfunction at this stage of EHI with extreme ataxia, disorientation and lack of unawareness of its surroundings. The horse will continuously stagger and repeatedly fall down and get up while possibly colliding with people or objects with a plunging action. Unsurprising, the horse is at risk of severe and significant injury. Eventual collapse with the loss of consciousness and even death may arise.

Treatment of EHI

In order to achieve success in the treatment of EHI, it is imperative that there is early detection, rapid assessment and aggressive cooling. The shorter the period is between recognising the condition and treatment, the greater the chance of a successful outcome. In particular settings such as racecourses or on particularly hot and humid days, events must be properly equipped with easily accessible veterinary care and cooling devices. It is highly effective if a trained worker inspects every horse in order to identify those horses at risk or exhibiting symptoms.

If EHI is recognised, veterinary intervention will be paramount in the recovery to prevent further illness and suppress symptoms. It will be important to note any withdrawal periods of any non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and analgesics before returning to racing. There are a number of effective ways to cool the horse with easily accessible resources.

Whole body cooling systems

Cooling the horse with ice-cold water is an effective way to draw heat from the underlying tissues. In addition, cooling the skin redistributes cooled blood back to the central circulatory system thus reducing thermal strain with the cooling of core body temperature.

The system that works best for horses due to its size is spray cooling heat transfer. It is ideal to have two operators to spray either side of the horse. It is recommended to begin at the head and neck followed by the chest and forelimbs then the body, hind limbs and between the legs. Spray nozzles are recommended to provide an even coverage of the skin surface.

Dousing is another technique in which horses are placed in stalls and showered continuously until the condition resolves. Pouring buckets over the entire body of the horse is not recommended as most of the water falls to the ground, thus, not efficient at cooling the horse.

Because most horses suffer from EHI immediately after the race, the appropriate location for inspection, cooling systems and veterinary care should be in the dismounting yard and tie-up stalls. There must be an adequate supply of ice to ensure ice-cold water treatment.

When treating a horse with EHI, there must be continuous and uninterrupted cooling until the CNS dysfunction has disappeared.

When the skin surface temperature decreases to 86°F (30°C), cutaneous skin vessels begin to disappear; CNS function returns to normal, and there is the normalization of behavior. Cooling can be stopped, and the horse can be walked once CNS abnormalities have resolved. It must remain closely monitored for a further 30 minutes in a well-ventilated and shaded region. It is important that they are not unattended.

Scraping sweat off of the horse must only be done if the conditions are humid with no airflow. However, if it is hot and there is good airflow, scraping is unnecessary because the sweat will evaporate.

Cooling collars

During strenuous exercise, there is a combination of heat production in the brain, reduced cerebral blood flow, creating cerebral ischaemia as well as the brain being perfused with hot blood. It is believed that cooling the carotid artery that aids in blood perfusion of the brain might be a strategy to cool the brain. A large collar is placed on either side and around the full length of the horse’s neck and is cooled by crushed ice providing a heat sink around the carotid artery; and it is able to pump cooled blood into the brain.

Another possible benefit of this device is the cooling of the jugular veins, which lie adjacent to the carotid arteries. The cooled blood in the jugular veins enter the heart and is pumped to the rest of the body, hence, potentially cooling the whole body. In addition, it is thought that the cooling of the carotid artery causes it to dilate, allowing greater blood flow into the brain.

Provision of shaded areas

Shaded areas with surfaces that reflect heat, dry fans providing air flow and strategically placed hoses to provide cool water is an important welfare initiative at racecourses in order to minimize risk of EHI and treat when necessary.

Conclusion

The most effective treatment of EHI is the early detection of the disease as well as post-race infrastructure that allows monitoring of horses in cooling conditions, while providing easily accessible treatment modalities when they are needed.

Evaluating the horse’s central nervous system dysfunction is essential to recognise both the disease as well as monitoring the progression of the disease. CNS dysfunction allows one to define the severity of the condition.

Understanding the pathophysiology of EHI is essential. It is important to recognise that it is a complex condition where both the inflammatory and thermoregulatory pathways work in combination. With a better understanding of these pathways, more effective treatment for this disease may be found.

Enhancing horse safety in training and racing

The Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures 2023

Article by Adam Jackson MRCVS

The Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures, is an annual gathering devoted to the racing industry and the health and wellbeing of the horses involved.

This year, equine veterinarians, researchers, students and industry professionals from around the world attended the event, held June 8, 2023, at the historic Tattersalls Sales in Newmarket, England.

There were insightful and informative lectures that educated the attendants but also instigated a healthy, lively debate on the health and welfare of the training and competing of horses. The underlying theme that was present during the whole event was all members of the conference had a deep passion and commitment to continuously progress and improve on managing the welfare and wellbeing of the horses in the industry, both on and off of the track.

Two very special guest speakers, Sir Mark Prescott and Luca Cumani, wonderfully illustrated these sentiments as they described their reflections on the improvement and enhancement of horse safety.

Horse racing may be regarded as an elite sport, and all activities involving horses have an element of risk. All stakeholders in the racing industry must continuously work to ensure that the risks are minimized in order to reduce the number of injuries and fatalities that may occur in training and on the racecourse. There are now well-publicized concerns regarding the acceptability of exposing horses to risk in racing. These lectures and all of the attendees embraced the values of the public will so that there can be continued acceptance of horse sports.

Reducing the Incidence of Fractures in Racing

Christopher Riggs of The Hong Kong Jockey Club clearly outlined the various strategies to reduce the risk of fractures in racehorses. There are two principal strategies that may used to reduce the incidence of severe fractures in horses while racing and training:

1.Identifying extrinsic factors that increase risk and take action to minimize them.

An example would be investigating different racing surfaces in order to determine which may provide the safest racing surface. However, studies have provided limited evidence and support for subtle extrinsic factors.

2.Identifying individuals that are at increased risk and prevent them from racing or minimize that risk until the risk has subsided.

There are many research routes that are being undertaken to identify those horses that may be at a higher risk of fractures. There are investigations involving heritability and molecular studies that may provide evidence of genetic predisposition to fracture. However, Dr. Riggs explained that further understanding of the relationship between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors is required before genetic screening is likely to be of practical use.

Pre-race screening of horses by diligent clinical examination is poor at reducing the incidence of fracture. Dr. Riggs described another strategy that may assist with a clinical examination that is the use of biomarkers in blood and urine.

Unfortunately, the precision to be of practical value has so far remained relatively unrewarding. Wearable technology that records biometric parameters, including stride characteristics, has shown some promise in identifying horses that are at increased risk of fracture; although Dr. Riggs explained that this work requires further development.

Finally, Dr. Riggs described both the use and current limitations of diagnostic imaging in identifying pre-fracture pathology in order to identify a horse at imminent risk of fracture. He conceded that further knowledge of the significance of the range of abnormalities that can be detected by imaging is incomplete.

Dr. Riggs concluded his lecture by expressing that the implementation of diagnostic imaging to screen “high-risk” horses identified through genetic, epidemiology, biomarkers and/or biometrics may be the best hope to reduce the incidence of racing fractures. This field can be advanced with further studies, especially of a longitudinal nature.

Professor Tim Barker of Bristol Veterinary School discussed the need for further investment in welfare research and education. One avenue of investment that should be seriously considered is the analysis of data related to (fatal) injuries in Thoroughbred racing over the last 25 years.

It was expressed, with the abundance of data that has been collected, that some risk factors would be relatively simple to identify. An encouraging example in the collection and use of data to develop models in predicting and potentially preventing injury has been conducted by the Hong Kong Jockey Club funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Equine Welfare Research Foundation. This may provide an opportunity to pilot the use of risk profiling to contribute to decision-making about race entries. In addition, the results of the pilot study combined with other sources of data may encourage race authorities to mandate the collection of veterinary and training data in order to help in risk mitigation.

Horse racing is an international sport, and there are different governing bodies that ensure racing integrity. However, the concept of social license equestrian sports and Thoroughbred horse racing continues to gain significant public attention. Therefore, racing governing bodies are increasingly aiming to provide societal assurances on equine welfare.

Dr. Ramzan of Rossdales Veterinary Surgeons provided an eloquent and clear message during his lecture that race yard veterinarians and trainers are instrumental in ensuring good horse health and welfare and reducing serious injury of the horse both while training or racing, which will provide sufficient trust and legitimacy from the public and society. This feasible goal can be reached with good awareness of members involved in the care and training of each individual horse and conveying this information and any concerns to their veterinarian. The veterinarian can also contribute by honing their knowledge and skills and working closely with yard staff in order to make appropriate and better targeted veterinary intervention.

In the last two decades, there has been an incredible evolution and exciting developments in diagnostic imaging in the veterinary profession. It is believed that these technologies can provide a significant contribution to helping in mitigating fracture risks to racehorses on the course and in training.

Professor Mathieu Spriet of University of California, Davis, described how these improvements in diagnostic imaging has led to the detection of early lesions as well as allowing the monitoring of the lesions’ evolution.

He continued by explaining the strengths and limitations of different imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET). Being one of the leaders in the use of PET in equine veterinary medicine, he presented further insight on how this particular modality provides high-resolution 3-D bone scans while being very sensitive to the identification of bone turn-over prior to the development of structural changes and allowing one to distinguish between active and inactive processes when structural changes are present.

He concluded his impressive lecture by providing evidence with amazing PET images that the role of imaging is not merely for diagnostic purposes to characterize clinical abnormalities, but can also be used as a screening tool in certain horse populations for fracture risk assessment or for the monitoring of lesions to provide clearance for racing.

Fractures, due to bone overloading rather than direct trauma occur commonly in Thoroughbred racehorses and are the leading cause of euthanasia on the racecourse. Despite many changes to race conditions, the number of catastrophic fractures has remained relatively static, with approximately 60 horses a year having a fatal fracture during a race in the UK.

Against this backdrop, there have been great developments in the diagnosis and treatment of fractures in the last 40 years. Prevention of racecourse and training fractures would be ideal so the development of efficacious techniques to screen horses at risk may reduce the incidence and preserve social licensing.

Dr. Ian Wright

One technique discussed by Dr. Ian Wright of Newmarket Equine Referrals was to help mitigate the impact of racecourse fractures, which would be acute immobilization of racecourse fractures, thus, reducing associated pain and anxiety while optimizing clinical outcome and reducing on course fatality rates. Because of our increased understanding of fracture pathogenesis and their associated biomechanics, effective fracture immobilization has been made possible. The majority of fractures that occur in flat racing and between obstacles in jump racing, are a result of stress or fatigue failure of the bone and not associated with trauma.

In addition, fractures seen on the racecourse are often found in the same specific sites (i.e., metacarpal/metatarsal condyles and the proximal sesamoid bones of the fetlock) and have repeatable configurations. With this understanding and knowledge, racecourse veterinarians can optimally immobilize a fracture in a logical and pre-planned manner.

As Dr. Wright expressed, this allows the fracture patient to have reduced pain and anxiety and enable the horse to be moved from the course comfortably so that it can be further examined. Ultimately, this allows the veterinarian and all stakeholders to make effective and judicious decisions for the sake of the horse’s welfare and wellbeing. As Dr. Wright concluded, this benefits both horses and racing.

Dr. Debbie Guest of the Royal Veterinary College discussed a different approach in mitigating the risk of fractures during training and racing by developing novel tools to reduce catastrophic fractures Thoroughbreds. Because it has been found that some horses are more inherently predisposed to fractures than other horses, Dr. Guest and her team have developed a genome-wide polygenic risk score so that one can potentially calculate an individual horse’s risk of fracturing during training or racing compared to the population as a whole.

This strategy may contribute in identifying genetically high-risk horses so that additional monitoring of the patients can be exercised during their careers and also leading to fracture risk, which are found to be the cause of approximately half of these incidents.

The system of using DNA testing to identify biological processes that may or may not be present ultimately leading to fracture risk may be a powerful tool in lowering the risk of catastrophic fracture and requires further research and application.

Cardiac events & sudden cardiac death in training and racing

In racehorses, sudden death that is associated with exercise on the racetrack or during training is a serious risk to jockeys and adversely affects horse welfare and the public perception of the sport. It is believed 75% of race day fatalities result from euthanasia following a catastrophic injury. The other 25% of fatalities is due to sudden deaths and cardiac arrhythmias are found to be the cause of approximately half of these incidents. The lectures focused on this area of concern by providing three interesting lectures on cardiac issues in the racehorse industry.

Dr. Laura Nath of the University of Adelaide, explained the difficulties in identifying horses that are at risk of sudden cardiac death. It is believed that part of the solution to this difficult issue is the further development and use of wearable devices including ECG and heart rate monitors.

With the use of these technologies, the goal would be to recognize those horses that are not progressing appropriately through their training and screen these horses for further evaluation. This course of action has been seen in human athletes that develop irregular rhythms that are known to cause sudden cardiac death with the use of computational ECG analysis, even when the ECGs appear normal on initial visual inspection.

Knowing that ECGs and particularly P-waves are used as a non-invasive electrocardiographic marker for atrial remodeling in humans, Dr. Nath recently completed a study on the analysis variations in the P-wave seen on ECGs in athletic horses and found that increases of P-waves in racehorses are associated with structural and electrical remodeling in the heart and may increase the risk of atrial fibrillation (cardiac event).

Dr. Celia Marr of Rossdales Veterinary Surgeons continued the discussion of cardiac disease in both the training and racing of horses. Unfortunately, cardiac disease knowledge does lag compared to musculoskeletal and respiratory diseases when considering the causes of poor performance in racehorses. Due to the fact that cardiac rhythm disturbances are fairly common, occurring in around 5–10% of training sessions in healthy horses in Newmarket and over 50% of horses investigated for poor performance, Dr. Marr expressed the need for further research and investigation in this area.

In addition, this research needs to determine if there is indeed a link between heart rhythm disturbances and repeated episodes of poor performance and sudden cardiac arrest. ECGs and associated technologies are helpful, but there are limitations such as the fact that rhythm disturbances do not always occur every time the horse is exercised. Therefore, it would be of great value that a robust criterion is established when evaluating ECGs in racehorses. The Horserace Betting Levy Board has provided funding for investigation by initially exploring the natural history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (self-correcting form) to understand risk factors and predict outcomes for affected horses.

Continuing the theme of the lectures on irregular heart rhythms and associated sudden cardiac death (SCD) in training and racing, Professor Kamalan Jeevaratnam described his exciting research in using artificial intelligence (AI) to identify horses at increased risk of developing irregular rhythms that may cause SCD.

AI is an exciting and rapidly expanding field of computer science that is beginning to be implemented in veterinary medicine. With funding by the Horserace Betting Levy Board and the Grayson Jockey Club Research Foundation, Professor Jeevaratnam of the University of Surrey, has piloted three novel algorithms that help predict horses with rhythm abnormalities through the analysis of horses’ ECGs.

It was acknowledged that further research is required to develop this technology by using data collected from multiple sources, but the initial results are promising in the development of an useful AI tool to identify horses at risk of SCD and prevent catastrophic events, thus, ensuring the welfare of the horse in racing.

Conclusion

The Gerald Leigh Memorial Lectures was a thoroughly successful and enjoyable event attended by a variety of different members of the horse racing industry. Not only did the lecturers provide interesting and valuable information but also excitement for the future of racing. It was very clear that all the lecturers and attendees were passionate and committed to the racehorse welfare and wellbeing as well as retaining the social license for an exciting sport.

#Soundbites - What do you look for when you evaluate a yearling at sales, and are there sire lines that influence your opinions?

Linda Rice

Linda Rice

I look for a good shoulder, and usually that will transcend into a great walk, an athletic walk. I do that for the length of stride. I like to buy young mares. Of course I have preference for some stallions I have had success with like City Zip. And then stallions everybody likes: sons of Into Mischief, sons of Curlin, sons of McLain’s Music. I’ve done well with them. If they have a great shoulder and a great walk, I’ll take a shot on an unproven stallion.

Brad Cox

The first thing, from a physical standpoint, is you have to consider his size. Is he too big or too small? As far as sire lines, you’re looking for signs. You totally have to have an idea what the yearling will look like. Will he look like his sire? You pay attention.

Graham Motion

Graham Motion

I think many of us get influenced by stallions’ progeny that we have trained before. There are other ones that we avoid if we haven’t done well with a sire’s prodigy. I think the one thing I look for is athleticism in general. I’m not overly critical of conformation.

John Sadler

John Sadler

We’re looking primarily for dirt pedigrees for California. I have a good idea what works here, what doesn’t work here. Obviously, I’m partial to some of the sires I trained, Twirling Candy, Accelerate, and Catalina Cruiser who’s off to a very fast start. On the conformation side, I look for a well-conformed horse that looks like an athlete. As an experienced trainer, you look for any little things. You learn what you can live with or without. Then, obviously, I’m looking for Flightlines in a couple of years!

Simon Callaghan

Simon Callaghan

Generally, I’m looking for an athlete first and foremost. Conformation and temperament are two major factors. Yes, there are sire lines I like—not one specific one. Certainly it’s a relatively small group.

Tom Albertrani

Tom Albertrani

I’m not a big sales guy, but when I do go, I like to look at the pedigree first. Then I look for the same things as everyone else. Balance is important. I like to see a horse that’s well-balanced, and I like nicely muscle-toned hindquarters.

Michael Matz

One of the things, first of all, is I look at the overall picture and balance. We always pick apart their faults, then what things that are good for them. You look for the balance, then if they’re a young yearling or an older yearling. Those are some of the things I look at. If you like one, you go ahead. There are certain sires if you have had luck with them before. It all depends on what the yearling looks like. I would say the biggest things I look at are their balance and their attitude. When you see them come out and walk, sometimes I like to touch them around the ear to see how they react to that. That shows if they’re an accepting animal.

Alan F. Balch - Elephants

Article by Alan F. Balch

Among my earliest childhood memories is loving elephants. As soon as I first laid eyes on them in the San Diego Zoo, I was fixated. I still am. Not too long ago, at its relatively new Safari Park, I stood for an hour watching these pachyderms of all ages in their new enormous enclosure, enjoying a massive water feature. Now, every time I fire up YouTube, it knows of my interest; I am immediately fed the latest in elephant news and entertainment.

Right up there with horses and racing.

You probably know, however, that you’ll never see elephants in a major American circus anymore. No more elephant riding, either. Even that is endangered in parts of the world where it goes back centuries, along with forest work. Zoos now breed their own.

Which brings me to the difference between animal welfare and animal “rights,” which is the crux of the problem horse racing faces everywhere it still exists, not to mention all horses in sport.