Small but mighty - the role of antioxidants for horses in training

By Catherine Rudenko

Antioxidants are substances that slow down damage to organisms created by the presence of oxygen. The need for antioxidants is always there, in all species, increasing as exercise intensity and duration increase. Is there merit in specifically supplementing antioxidants to enhance performance?

• The nature of antioxidants

There are many forms of antioxidants naturally present within the body and supplied through the diet. One key feature of antioxidants is that they are “team players.” No one antioxidant alone can maintain the system, and some will only function in the presence of another antioxidant. The role of an antioxidant is to keep reactive oxygen species (ROS) or free-radicals created in the presence of oxygen at an optimum level. Oxygen is required for life; it is always present, but as an element, it is highly reactive and so can also have an adverse effect on the body. The reactivity of oxygen in the body produces ROS which cause damage to cellular components such as DNA, proteins and lipids of cell membranes. Some ROS also have useful cellular functions, and so the purpose of antioxidants is not to eliminate ROS altogether but to maintain a healthy balance. In general, antioxidants operate in two ways: either preventing the formation of an ROS or removing it before it can cause damage to a cell component.

• Sources of antioxidants

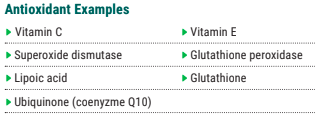

There are multiple sources of antioxidants including vitamins, enzymes and nutrient derivatives. Other nutrients such as minerals, whilst not having antioxidant properties, are also involved as their presence is required for the functioning of antioxidant enzymes. Two key examples are zinc and selenium.

Oxidative stress

As with many body systems, the ideal healthy balance can often go awry. When the level of ROS present overwhelms the capacity of antioxidants present, the body experiences oxidative stress. There are three main reasons for a horse in training experiencing oxidative stress:

• Increased exposure to oxidants from the environment

• An imbalance or shortage in supply of antioxidants

• Increased production of ROS within the body from

increased oxygen metabolism during exercise Oxidative stress is of concern as it can exaggerate inflammatory response and may be detrimental to the normal healing of affected tissues. Oxidative stress during strenuous exercise, such as galloping or endurance, is typically associated with muscle membrane leakage and microtrauma to the muscle. Oxidative stress is now understood to play a role in previously unexplained poor performance. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents or sign up below to read this article in full

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 60 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Can nutrition influence EIPH? - alternative and supportive therapies as trainers seek to find other means of reducing the risk or severity of EIPH

By Catherine Rudenko

EIPH (exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage) was first identified in racehorses in the 16th century. Since this time, the focus has been on mitigating the haemorrhage. Management of EIPH largely revolves around the use of furosemide, dependent of jurisdiction, may or may not be used on the day of racing. Alternative and supportive therapies are becoming increasingly popular as trainers seek to find other means of reducing the risk or severity of EIPH.

Nutrition and plant-based approaches are part of an alternative management program. Whilst research is somewhat limited, the studies available are promising, and no doubt more work will be done as using furosemide becomes more restricted. There are several directions in which nutrition can influence risk for EIPH, including inflammatory response, blood coagulation, cell membrane structure, hypotension and reducing known lung irritants.

The various approaches are all supportive, working on altering an element of risk associated with the condition. Some are more direct than others, focusing on the effect on red blood cells, whilst others work on some of the broader lung health issues such as reducing mucus or environmental irritants.

None are competitive with each other, and there may be an advantage to a ‘cocktail’ approach where more than one mode of action is employed. This is a common practice with herbal-based supplements where the interactive effects between herbs are known to improve efficacy.

Cell membrane

The red blood cell membrane—the semipermeable layer surrounding the cell—is made up of lipids and proteins. The makeup of this membrane, particularly the lipid fraction, appears to be modifiable in response to dietary fatty acids. Researchers feeding 50mls of fish oil found a significant increase in the percentage of omega-3’s in the cell membrane.

Essential fatty acids (EFA’s), omega 3 and omega 6, are important cell membrane components and determine cellular membrane fluidity. Fluidity of a cell membrane is important, particularly when pressure increases, as a cell membrane lacking in fluidity is more likely to break. A cell that can deform, effectively changing rather than breaking, has an advantage and is linked with improved exercise performance in human studies. Inclusion of fish oil in the diet increases the ability of red blood cells to deform.

Kansas State University investigated the effect of omega supplementation on 10 thoroughbreds over a five-month period. The diet was supplemented with either EPA and DHA combined, or DHA on its own. EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) are specific forms of omega-3 fatty acids commonly found in oily fish. When supplementing the diet with both EPA and DHA, a reduction in EIPH was seen at 83 days and again at 145 days. Feeding DHA on its own did not produce an effect.

Fish oil contains both EPA and DHA and is readily available, although the smell can be off-putting to both horse and human. There are flavoured fish oils specifically designed for use in horses that overcome the aroma challenge and have good palatability.

Inflammatory response and oxidative stress

Kentucky Equine research results

Airway inflammation and the management of this inflammatory process is believed to be another pathway in which EIPH can be reduced. Omega-3 fatty acids are well evidenced for their effect in regulation of inflammation, and this mode of action along with effect on cell membrane fluidity is likely part of the positive result found by Kansas State University.

Kentucky Equine Research has investigated the effect of a specific fish oil on inflammatory response with horses in training. The study supplemented test horses with 60mls per day and found a significant effect on level of inflammation and GGT (serum gamma-glutamyl transferase). GGT is an enzyme that breaks down glutathione, an important antioxidant. As GGT rises, less glutathione is available to neutralise damaging free radicals, creating an environment for oxidative stress.

A horse’s red blood cells are more susceptible to oxidative stress than humans, and maintaining a healthy antioxidant status is important for function and maintenance of cell integrity.

Rosehip

Supplements for bleeders will often contain relatively high doses of antioxidants such as vitamin C and vitamin E to support antioxidant status in the horse and reduce risk of damage to cell membranes. Vitamin C has also been shown to benefit horses with recurrent airway obstruction and increase antibody response. Dose rates required for an effect range from 15-20g per day. If including high doses of vitamin C in the diet, it is important to note that any sudden withdrawal can have negative effects. Gradual withdrawal is needed to allow the body’s own mechanisms for vitamin C production to recognise and respond to the change in status.

Rosehips are natural potent antioxidants containing many active substances. Research into the effect of rosehips specifically on red blood cells has shown they have a high efficacy when assessing their ability to ameliorate cell damage.

Hypotensive herbs

Caucus carota – wild carrott

The essential oil of caucus carota species is a well-documented oil having a hypotensive, lowering of blood pressure effect along with antifungal properties. Its antifungal effects are noted against aspergillus species, a common cause of poor respiratory health. Allium sativum is also well known for its ability to lower blood pressure. An initial study (data unpublished) into the effects of these two plants along with herbs reported to alleviate mucus in the lungs has shown promising results in a group of horses in training.

Prolonged blood coagulation

As prolonged blood coagulation is cited as a possible factor for EIPH, herbal products that are noted for their ability to enhance coagulation are in certain parts of the world widely used as part of managing EIPH. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

ISSUE 58 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 58 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

Nutrition - how to rein in your complex carb intake for times when work drops

By Catherine Rudenko

Carbohydrates are by far the largest component of any horse’s diet, typically two thirds by weight, yet we often focus more on other nutrients, such as protein—which in comparison forms only a small portion of the total diet at around 8-13%. Carbohydrates, specifically the balance between differing carbohydrate sources, influences three key areas relating to performance.

The choice of carbohydrate influences the type of energy available, providing varying proportions of ‘fast release’ or ‘slow release’ energy. The type of carbohydrate chosen also impacts behaviour, increasing or decreasing risk of excitability and certain stereotypical behaviours. Last, but by no means least, the choice of carbohydrate and the way in which it is fed impacts digestive health and the ability of the digestive system to convert food to ‘fuel’ for the body.

Getting the balance right between the different types of carbohydrates is important for getting the right results when having to adjust the intensity of training, when resting a horse and when working back up through the stages of fitness.

What are carbohydrates?

There are different ways of classifying or grouping carbohydrates, depending on whether you take things from the plant’s point of view or that of the digestive anatomy of the horse. Working with the horse in mind, carbohydrates are best classified by the section of the digestive system that they are processed in—either the small intestine or large intestine. The site of digestion determines the type of energy provided, often referred to as fast releasing for the small intestine and ‘slow releasing’ for the large intestine. The group of carbohydrates, known as hydrolysable carbohydrates, are the group behind the description of fast releasing, whilst the group known as fermentable carbohydrates are those forming the ‘slow releasing’ category. Within the fermentable group, there are three sub groups of rapid, medium and slow.

What are carbohydrates made of?

There are many types of carbohydrates in the horse’s diet, ranging from simple sugars to more complex structures. They are defined by their degree of polymerisation, which refers to the way in which sugar units are joined together. How a carbohydrate is formed and the type of link present are important as they determine if digestion is possible in the small intestine or whether fermentation in the large intestine is required. This influences the type of energy available.

For horses in training, the type of carbohydrate of particular interest is the polysaccharide group which includes starch, cellulose, hemicellulose and fructans amongst others. Starch is found in significant quantities in hard feeds, whilst cellulose and hemicellulose, amongst other fermentable carbohydrates are abundant in forages. Pasture is a source of fructans, which can change rapidly depending on growing conditions and daylight hours.

Structure

Single sugars, also called simple sugars, comprise one unit only. They are categorised as monosaccharides—the most commonly known being glucose. For horses in training this is a highly valuable sugar as it is the main ‘fuel’ for muscles. Glucose forms the basis of many of the more complex structures of interest to horses in training.

When two sugars join together, they are known as a disaccharide—the best known being lactose which is found in mare’s milk. Oligosaccharides refer to more complex structures where more units are joined together—a common example being fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) which many horses in training are specifically fed as a prebiotic to support digestive function.

Type of Carbohydrate

Polysaccharides, our group of particular interest, are significantly more complex chains that are branched and are not so easily digested as the simple sugars. The branched nature of polysaccharides, such as starch and cellulose, are the result of links between chains of sugars. The type of link present determines whether or not it will be possible for the horse to digest this form of carbohydrate in the small intestine or not.

Starch

Starch is the primary carbohydrate of interest in our hard feeds. It is a hydrolysable carbohydrate, which can be digested in the small intestine, releasing glucose into the bloodstream. For horses in training this is the most important fast release energy source. Starch is found in all plants, with the highest quantities seen in cereals such as oats, barley and maize.

Composition of cereals commonly used in racing feeds

Starch is made up of two types of sugar chains: amylose and amylopectin, which are formed from glucose units. Amylose itself is easily digested, however amylopectin has a different type of bond connecting each branch, which the enzymes of the small intestine cannot break down. Feed processing, which changes the structure of starch and breaks apart the previously indigestible bonds, is therefore a key factor in ensuring that when starch is fed that the maximum amount of glucose is derived.

Amylose and Amylopectin

Feed processing comes in many forms, from simply crushing or rolling the grain to cooking techniques including micronizing, steam flaking, pelleting or extruding. The amount of processing required for what is deemed efficient digestion differs by grain type. Oats have a natural advantage within the cereal group as they can be fed whole, although processing can still improve digestion. Barley, wheat and maize cannot be fed whole or simply rolled. They require cooking to ensure that starch becomes available, and the impact of cooking processes is much greater for these grains.

The availability of starch is assessed through the amount of glucose released into the blood after feeding. The study below shows the effect of steam cooking maize (corn) compared to two processes that simply change the physical appearance, cracking or grinding. Steam-flaked maize is more available as shown by the greater glucose response.

Starch is a fast release energy source, being digested in the small intestine, and the term can easily be misunderstood. It does not mean that the horse will suddenly run at top speed nor appear to be fuelled by ‘rocket fuel’. The word ‘fast’ relates to the relatively short time it takes for digestion to occur and glucose to be available. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

ISSUE 57 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 57 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - ONLY $24.95

The Balancing Act - feed - supplement

By Catherine Rudenko

Key considerations when reviewing what you feed and if you should supplement

With so many feeds and supplements on the market, the feed room can soon take on the appearance of an alchemist’s cupboard. Feeding is of course an artform but one that should be based on sound science. In order to make an informed decision, there are some key questions to ask yourself and your supplier when choosing what ingredients will form your secret to success.

QUESTION #1: What is it?

Get an overview of the products’ intended use and what category of horse they are most suited for. Not every horse in the yard will require supplementing. Whilst one could argue all horses would benefit from any supplement at some level, the real question is do they need it? Where there is a concern or clinical issue, a specific supplement is more likely warranted and is more likely to have an impact. A blanket approach for supplements is really only appropriate where the horses all have the same need (e.g., use of electrolytes).

QUESTION #2: Is it effective?

There are many good reasons to use supplements with an ever-increasing body of research building as to how certain foods, plants or substances can influence both health and performance. Does the feed or supplement you are considering have any evidence in the form of scientific or clinical studies? Whilst the finished product may not—in a branded sense—be researched, the active components or ingredients should be. Ideally, we look for equine-specific research, but often other species are referenced, including humans; and this gives confidence that there is a sound line of thinking behind the use of such ingredients. Having established if there is evidence, the next important question is, does the feed or supplement deliver that ingredient at an effective level? For example, if research shows 10g of glucosamine to be effective in terms of absorption and reaching the joint, does your supplement or feed—when fed at the recommended rate—deliver that amount?

There is of course the cocktail effect to consider, whereby mixing of multiple ingredients to target a problem can reduce the amount of each individual ingredient needed. This is where the product itself is ideally then tested to confirm that the cocktail is indeed effective.

QUESTION #3: How does it fit with my current feeding and supplement program?

All too often a feed or supplement is considered in isolation which can lead to over-supplementing through duplication. Feeds and supplements can contain common materials, (i.e., on occasion there is no need to further supplement or that you can reduce the dose rate of a supplement). Before taking on any supplement, in addition to your current program, you first need to have a good understanding of what is currently being consumed on a per day basis. This is a different matter of comparing one feed tag or supplement pot to another one. Such ‘direct’ comparisons are rarely helpful as dose rates or feeding rates differ, and the manner in which units are expressed is often confusing. Percentages, grams, milligrams and micrograms are all common units of measure used on labeling. The unit chosen can make an inclusion sound significant when perhaps it is not. For example, 1g could be expressed as 1,000mg. Looking at the contribution, any feed or supplement made on an as-fed basis is the only way to know the true value for the horse. There are many categories of supplements in the market with the greatest cross-over existing around use of vitamins or minerals, which appear in both feeds and supplements. Occasionally feeds can also be a source of ingredients used in digestive health supplements or joint supplements. The contribution of your chosen feed(s) is the base from which you decide what, if any, of those matching nutrients or ingredients should be added to. Common areas for cross-over include vitamin E, selenium, B vitamins, iron, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, zinc and copper. Duplication may also occur around use of vitamin C (antioxidant), FOS (prebiotic), MOS (pathogen binder), yeast (prebiotic) and occasionally maerl (marine algal calcium source).

Vitamins and Minerals An often-seen addition to the feed program for Thoroughbreds are bone supplements—providing relevant minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, zinc and copper. Whilst unquestionably important for sound skeletal development these nutrients are also present in feed, albeit at slightly varying levels by brand. Below is a typical profile of a bone supplement with the information as seen per kilogram on the feed label. Calcium and phosphorus are given as percentages on labels and require converting to grams when looking to calculate the amount of nutrients consumed. In this example, the calcium content is 20%, equivalent to 200g per kilogram.

The feeding rate is 31⁄2oz per horse per day. …

CLICK HERE to return to issue contents

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

ISSUE 56 (PRINT)

$6.95

ISSUE 56 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Four issue subscription - PRINT & ONLINE - ONLY $24.95

Thoroughbred nutrition past & present

By Catherine Rudenko

Feeding practices for racehorses have changed as nutritional research advances and food is no longer just fuel but a tool for enhancing performance and providing that winning edge.

While feeding is dominantly considered the content of the feed bucket, which by weight forms the largest part of the horse’s diet, changes in forage quality have also played a role in the changing face of Thoroughbred nutrition. The content of the feed bucket, which is becoming increasingly elaborate with a multitude of supplements to consider, the forages—both long and short chop and even the bedding chosen—all play a part in what is “the feed program.” Comparing feed ingredients of the past against the present provides some interesting insights as to how the industry has changed and will continue to change.

Comparing key profiles of the past and present

The base of any diet is forage, being the most fundamental need of the horse alongside water. Forage quality and form has changed over the years, particularly since haylage entered the market and growers began to focus specifically on equine. The traditional diet of hay and oats, perhaps combined with mash as needed, provided a significantly different dietary intake to that now seen for horses fed a high-grade haylage and fortified complete feed.

Traditional Diet

7kg Oats

1kg Mash – comprised of bran, barley, linseed and epsom salt

0.5kg Chaff

Hay 6% protein consumed at 1% of bodyweight

Modern Diet – medium-grade haylage

8kg Generic Racing Mix

0.5kg Alfalfa Chaff

60ml Linseed Oil

60g Salt

Haylage 10% protein consumed at 1% of bodyweight

Modern Diet – high-grade haylage

8kg Generic Racing Mix

0.5kg Alfalfa Chaff

60ml Linseed Oil

60g Salt

Haylage 13% protein consumed at 1% of bodyweight

Oats field

The traditional example diet of straights with bran and hay easily met and exceed the required amount of protein providing 138 % equirement. When looking at the diet as a whole, the total protein content of the diet inclusive of forage equates to 9.7%. In comparison, the modern feeding example using a high-grade haylage produces a total diet protein content equivalent to 13.5%. The additional protein—while beneficial to development, muscle recovery and immune support—can become excessive. High intakes of protein against actual need have been noted to affect acid base balance of the blood, effectively lowering blood pH.1 Modern feeds for racing typically contain 13-14% protein, which complement forages of a basic to medium-grade protein content very well; however, when using a high-grade forage, a lower protein feed may be of benefit. Many brands now provide feeds fortified with vitamins and minerals designed for racing but with a lower protein content.

While the traditional straight-based feeding could easily meet energy and protein requirements, it had many short-falls relating to calcium and phosphorus balance, overall dietary mineral intake and vitamin intake. Modern feeds correct for imbalances and ensure consistent provision of a higher level of nutrition, helping to counterbalance any variation seen within forage. While forage protein content has changed, the mineral profile and its natural variability has not.

Another point of difference against modern feeds is the starch content. In the example diet, the “bucket feed” is 39% starch—a value that exceeds most modern racing feeds. Had cracked corn been added or a higher inclusion of boiled barley been present, this level would have increased further. Racing feeds today provided a wide range of starch levels ranging from 10% up to the mid-thirties, with feeds in the “middle range” of 18-25% becoming increasingly popular. There are many advantages to balancing starch with other energy sources including gut health, temperament and reducing the risk of tying-up.

The horse with a digestive anatomy designed for forages has limitations as to how much starch can be effectively processed in the small intestine, where it contributes directly to glucose levels. Undigested starch that moves into the hindgut is a key factor in acidosis and while still digested, the pathway is more complex and not as beneficial as when digested in the small intestine. Through regulating starch intake in feeds, the body can operate more effectively, and energy provided through fibrous sources ensures adequate energy intake for the work required.