The work being done on the prevention of serious fractures in the racehorse

Fractures: are they inevitable or preventable?

The incidence of serious fractures in horses racing on the flat is low (around one case every one to two thousand starters); but when fractures occur the consequences are often severe for the horse and, sometimes, the jockey. Both the severity and the dramatic nature of these injuries cause a significant negative impact to everyone connected with the horse, as well as spectators.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) convened the Global Summit on Equine Safety and Technology at Woodbine Racecourse, Toronto, in June 2024, to focus on how current research into causes of racehorse fatalities on the course, including fractures, can be advanced and translated into action, to better understand the factors leading to fatalities and potentially mitigate them. At the meeting there were two workshops where specialist veterinary clinicians, pathologists and researchers came together to focus on Exercise Associated Sudden Death incidents and fractures.

Why do fractures occur?

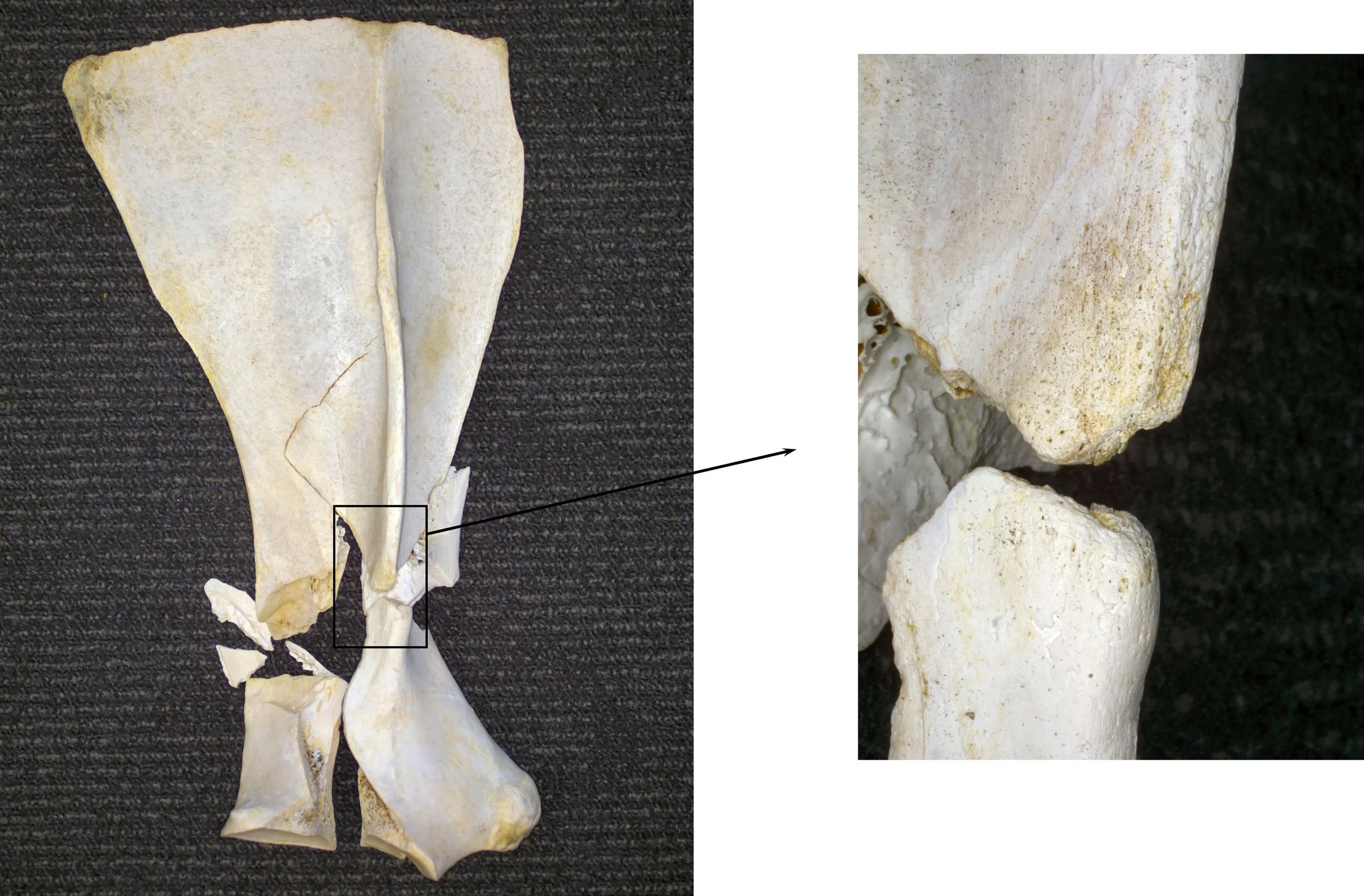

While most fractures that affect racehorses on the flat appear to arise spontaneously, while the horse is racing, and in the absence of any obvious trauma, we now know that the majority are the consequence of structural fatigue, involving a process that started weeks or even months earlier. Just as a paper clip will break if it is repeatedly bent once too often, a bone will fracture if it is loaded recurrently beyond certain limits. Microscopic damage accumulates in the bone tissue until a small fissure develops, which can extend to a severe fracture if it is not detected and the horse continues to race.

The fatigue life of bone decreases exponentially as the magnitude of load on the bone during each loading cycle increases. Loads on the skeleton are directly related to the speed of exercise, work at a fast gallop causes fatigue damage at a rate many orders of magnitude greater than when the horse is exercised at slower speeds. Unfortunately, fatigue damage, and even formation of small fissures in the bone, often proceed without the horse showing any outward signs and so, historically, affected horses have often gone undetected until it is too late.

Are there any natural biological mechanisms that protect against fracture?

An ability to run fast has been of evolutionary benefit to horses by enabling them to escape predators. Humans have refined this characteristic in specific breeds, notably the Thoroughbred, through targeted breeding and training practices. The need for a horse to undertake a fast gallop in the wild is likely to be relatively infrequent and well-within the bounds that are likely to cause fatigue damage. Conversely, society’s expectations of racehorses, and the training imposed on them, place loads on the skeleton that may be excessive.

Some readers may be surprised to learn that bone is a remarkably “smart” tissue. It is so much more than the equivalent of the “concrete structural beam” laid down to support man-made structures. While bone is composed partly of minerals, it is still very much a living tissue, packed with blood vessels, nerves and cells. Furthermore, the cells are all physically interlinked through microscopic projections, and can communicate with each other through their interconnections. This biological network allows bone tissue to detect the effects of loads applied to the bone as whole, and to initiate a cellular response to model the bone structure if those loads change.

For instance, increase in the magnitude of prevailing loads (e.g. through increase in an animal’s weight or the introduction of high-speed work) will cause greater deformation of the bone and this will stimulate a process that results in the formation of additional bone mass and, if beneficial, subtle reshaping of the bone’s geometry. The bone will be stronger as a result and deform less for the given load. Conversely, if the prevailing loads decrease (e.g. during a period of rest) bone deformation is reduced, and bone may be removed through a process of resorption. This overall mechanism of remodelling is called “adaptation”. Bone adaptation facilitates the formation and maintenance of a skeleton that is continually fit for purpose, even as that purpose changes.

Beyond this, there are biological mechanisms that detect when a bone is damaged (e.g. small cracks develop) and will initiate repair. The restoration process involves removal of microscopic packets of bone tissue, including the damaged portion, and its replacement with fresh, healthy material. This process means that fatigue-related damage of bone can be resolved and, theoretically, that a bone can tolerate infinite cycles of load. However, the process of repair has been shown to be inhibited if the bone is still regularly subjected to cycles of high load (i.e. the horse remains in training) and it can also be overwhelmed if the rate of damage accumulation is too high.

Are fractures something that racing just has to live with or can we do something about them?

Applying the knowledge we have gained from research over the past forty years has already had an impact on reducing the risk of fractures in some situations, and there are good reasons for optimism that we will be able to prevent a much greater proportion of racing fractures in the future. For example, epidemiological studies can help to identify certain management practices and design features of racecourses associated with an increased risk of fracture and these can be modified.

The introduction of strict rules governing the validity of sale of a horse in a claiming race in some jurisdictions in the USA, depending on the health status of the horse immediately after the race, has had a significant impact on reducing the incidence of fractures. Over 300 potential risk factors have been examined and those found to have a significant association with fracture, modelled in numerous studies.

Applying the findings to individual racecourses still requires much work and, ultimately, almost half of the variation in risk of fracture appears to be due to factors associated directly with the horse itself. Epidemiology has also been applied to identify characteristics of a horse’s history that may indicate that it is at higher risk of fracture. These studies depend on access to detailed and accurate data and recent work has highlighted the importance of including veterinary records. Access to these records, suitably anonymised to protect confidentiality, will have a profound impact in the development of more accurate models that can be used to predict the risk of fracture.

Studies into the genetics of Thoroughbreds have identified particular genes that are associated with a predisposition to fracture. This is a highly complex field and interaction of the environment and genetics ultimately determines the fracture status of an individual animal. However, genetic screening will help to identify horses that may benefit from closer monitoring. Clearly this is a sensitive topic, especially to breeders, although hopefully stakeholders will make choices that will be in the best interest of Thoroughbreds and racing in the long term.

Wearable technology, carried on the horse to record cardiac and stride data shows promise in being able to identify horses at early stages of skeletal injury. Preliminary results suggest that this is possible by identifying changes in stride characteristics, such as stride length, in individual animals in races leading up to the horse sustaining an injury. There has been a lot of interest and publicity associated with wearable technology and its use to identify horses both at imminent risk of fracture as well as those with irregularities of cardiac rhythm which may lead to exercise associated sudden death, although work still needs to be undertaken to substantiate their use in both these contexts.

These devices are also proving increasingly valuable as tools to record actual workload undertaken by individual horses in training. This is important information that is needed for researchers to accurately model associations between workload and risk of fracture, and for trainers to use to apply such models in the future.

Modern clinical imaging technology, especially that which allows detailed scrutiny of areas of bones in the locations where fractures commonly originate, facilitates identification of bone damage due to fatigue much earlier than was previously possible. The increasing availability of computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) machines that can be used to image the lower limb of the standing horse has made their application more practical in horses that are in active training.

There is potential for this technology to be used to screen horses prior to racing, as is currently undertaken before some race meetings in the state of Victoria, Australia. The enhanced resolution of CT helps to identify subtle fissures in bone that may be overlooked by conventional x-ray procedures and in such cases its value as a screening tool is indisputable. However, work is still ongoing to decipher the importance of even more subtle changes in bone structure. Undertaking imaging studies carries expense, and is not without some risk, and the concept of regularly imaging the relevant anatomical regions of racehorses to screen for risk of fracture clearly has challenges.

A simple blood test for “biomarkers” that could identify animals at an early stage of pre-fracture pathology would be a helpful tool. Even if the accuracy of such a test was insufficient to make important decisions about whether or not to race a horse, it could at least be used to reduce the number of animals that would need to be subjected to imaging studies.

Research into changes in the patterns of arrays of many molecules in the blood (so called “omics” studies) have led to many breakthroughs in screening systems in humans and animals. Preliminary studies give hope that this technology can be used to assist in the detection of horses at increased risk of fracture, although a practical test is still likely to be several years off.

It is important to acknowledge that all screening tests carry some risk: they may falsely identify normal horses to be at increased risk (false positives) and fail to recognise horses that have a problem (false negatives). Careful development and thorough testing of screening systems is therefore essential, and this takes time and money. Furthermore, no test is ever 100% accurate, and the practical application of screening designed to prevent fractures will require racing to strike a balance between stopping some normal horses from running and failing to identify some of those likely to suffer a fracture. This will require informed and engaged discussion between researchers and all relevant industry stakeholders, and strong leadership and clear communication from racing’s regulators.

Perhaps an even greater question is whether we can recommend ways of exercising horses in training that minimise the risk of fatigue damage that leads to fracture in the first place. Research conducted in Melbourne, Australia demonstrated that trainers who worked their horses at high speed in training less frequently than others experienced a lower incidence of fracture.

A very important additional bit of detail was that, excepting the extremes, their racing results and performance outcomes were no different. Recognition that bone is like other tissues, in that it needs time to respond to changes in physical activity and requires a training programme that accounts for this, is important. We are all well aware of the need to develop muscle to improve power and endurance in training, but the concept of training bone is less familiar.

Fortunately, an adaptive response of bone has been shown to occur reasonably quickly to only a few cycles of altered load. Stimulating young, healthy racehorses to increase the strength of their bones requires only a short distance of gallop work. Therefore, introducing a very small amount of fast work at the early stages of a training programme can be sufficient to prepare the bones for more sustained work without the risk of causing substantial fatigue damage. However, if the horse is rested from high-speed work for more than a few days, the process reverses, and bone mass will start to be resorbed (in evolutionary terms, there is no point wasting energy carrying around bones that are bigger and heavier than you need them to be).

So, when a horse is brought back into work after a period of rest, the process of training the skeleton has to be considered all over again. Periods of rest in themselves are also important to allow the bone to repair because even a sensitive training programme will result in some fatigue damage, and the accumulation of this damage may eventually lead to fracture. The innate, biological mechanism of bone repair is switched off (inhibited) while horses remain in active training and a period of rest is required for this process to be reactivated and for repair of fatigue-damaged tissue to take place. Therefore, periodic periods of rest from training are required in order to give the skeleton the best opportunity to heal and “reset” itself.

In summary, a training programme that:

reduces the distance of work (especially high-speed work) that a horse undertakes in its racing career to optimal levels that promote bone health (while racing and training);

stimulates appropriate development of bones through short bursts of fast work early on in a training campaign;

builds periods of rest into a horse’s life span in training;

will all reduce the risk of accumulated fatigue damage that predisposes to fractures developing.

To move forward, the industry needs to invest in research so that metrics can be developed to help trainers to apply these concepts to their own training techniques in a practical way. There will be a range of durations and speeds of work that will reduce the risks of fracture across different populations of Thoroughbreds, and these will only be demonstrated by investing in studies measuring the effects of different training regimes in significant numbers of horses.

Scientists and Racing Working Together

Developing and applying measures that are designed to reduce the risk of fracture will require the commitment of all stakeholders. We also need to be realistic in acknowledging that, due to the athletic nature of racing, the risk of a racehorse sustaining a fracture will never be eliminated and, sadly, for some of these injuries euthanasia will be the only humane option.

When racing authorities communicate to the public that the safety of equine athletes in racing is a priority, their credibility is clearly demonstrated by investing in work to bring the risks of injury, including fractures, down to the lowest possible level.

There will inevitably be an element of “pain” associated with the work and changes required to reduce injury rates. Screening systems will disrupt normal cycles of work, there will be frustration as horses that appear fit are withdrawn from races on the basis of findings of “risks” that we might find difficult to conceptualise, there will be additional financial demands to fund studies, and a sense of exposure as records that are necessary for researchers to do their work are shared, even with promises of confidentiality and anonymity.

At the Toronto meeting, the IFHA has already committed to supporting global scientific research efforts to reduce the incidence of racehorse injuries, including fractures. I look forward to the benefits this co-ordinated approach to research can bring by both reducing injury rates in equine athletes, and at the same time, demonstrating to society the priority racing gives to equine welfare.

The work being done to monitor and detect gene doping practices and understanding the future perspectives in breeding

The pursuit of genetic perfection no longer ends with traditional selection. Alongside meticulously planned breeding programs and increasingly sophisticated genomic profiling, a new and controversial possibility is quietly gaining ground - gene doping. The idea of altering a thoroughbred’s gene expression to enhance muscle power, endurance, or cellular recovery is both compelling and profoundly unsettling.

In experimental research, these tools are already being tested using animal models and although no official cases have been reported in racing so far, the specter of their potential use is growing increasingly real. The discourse around gene doping and gene therapy more broadly, is emerging with greater urgency, raising complex ethical, technical, and regulatory questions.

This is an extremely dangerous development, not only because it threatens the integrity of competition, but also due to the unknown risks it poses to the animals themselves, who may be subjected to genetic manipulation without the capacity to understand or consent. Both the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) have taken a clear stance against such practices, prohibiting their use in both human and equine athletes.

Despite these regulatory safeguards, the rapid pace of genetic science is testing the limits of current frameworks. Advances in biotechnology are no longer confined to the laboratory or speculative discourse they are beginning to manifest in the real world. While equestrian regulators have outlined strict prohibitions, enforcement is inherently reactive, often lagging behind innovation. The gap between what is technically possible and what is legally permitted is widening, and within that space, experimental applications of gene editing are quietly advancing. It is in this grey zone, between regulation and research, that the first real-world example of genetically edited equine athletes has emerged.

This shift from theory to application became strikingly evident in October–November 2024, when Argentina’s biotech firm Kheiron Biotech announced the birth of five genetically edited polo foals, marking the world's first CRISPR‑Cas9–engineered equine athletes.

These horses were derived from mesenchymal stem cells of Polo Pureza, a champion Argentine polo mare celebrated in the breeders’ Hall of Fame. Rather than cloning, scientists used CRISPR‑Cas9, a highly precise genome-editing tool, acting like molecular scissors to modify specific DNA segments. The primary target was the myostatin (MSTN) gene, which restricts muscle growth by silencing or altering this gene. The resulting foals were designed to possess enhanced muscle mass and explosive speed, while preserving the mare’s natural agility and temperament.

The editing process involved removing an oocyte’s nucleus, replacing it with DNA from Polo Pureza’s edited stem cells, and implanting the embryos into surrogate mares; five live foals were born from eight pregnancies.

In the context of the horse racing industry, where the value of a Thoroughbred can hinge on milliseconds of performance and the ability to sustain speed over distance, gene editing presents an especially tempting field.

Can we imagine this scenario extending into the racing world?

Scientifically, the answer is yes. The same techniques used to enhance athletic potential in polo ponies could, in principle, be applied to racehorses. Several genetic traits directly influence race performance and could be enhanced through precise gene editing. The range of traits that could be enhanced is both broad and strategically targeted. The ultimate goal would be to produce a horse that runs faster, resists fatigue better, recovers more quickly, and possibly even suffers fewer injuries, all thanks to targeted genetic interventions.

One of the primary areas where gene editing could intervene is muscle development. Racehorses rely on explosive power and speed, and one of the key genes responsible for regulating muscle growth is myostatin (MSTN).

This gene acts like a natural limiter, preventing muscles from growing excessively. By suppressing or modifying MSTN, it’s possible to significantly increase the mass and strength of skeletal muscles, giving horses more power during acceleration and allowing them to maintain higher speeds.

Enhancing muscle development could be especially valuable for short-distance (sprint) races, where raw power is a major performance factor. Alongside MSTN, scientists may also target follistatin, a glycoprotein that naturally inhibits myostatin and encourages muscle growth. Its manipulation, already studied in other species, could serve as an indirect yet powerful enhancer of muscle development in horses.

Another key aspect involves muscle endurance and recovery, where hormones like Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) and growth hormone (GH) play essential roles. IGF-1 stimulates protein synthesis and helps in repairing tissue damage after intense effort.

Gene therapy involving IGF-1 has shown increased muscle mass in animal studies, even without training. When combined with exercise, its effects are amplified, and it may also reduce muscle loss during periods of rest (highly relevant in racing horses recovering from injury or off-season periods).

Performance in longer races, however, is not just about power, it’s about how efficiently a horse uses oxygen. Here, oxygen transport genes like erythropoietin (EPO) and HIF-1 become highly relevant. By increasing red blood cell production, these genes allow muscles to receive more oxygen during effort, delaying fatigue and improving aerobic endurance. In practice, a horse with genetically enhanced EPO expression could maintain high levels of exertion for longer without performance dropping off. In addition, HIF-1 also activates other processes, such as the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis) and improved mitochondrial function, both of which contribute to athletic stamina.

There is also the possibility of influencing muscle contraction efficiency through genes like ACTN3, which is associated with fast-twitch muscle fibers, those responsible for rapid, explosive movements. Variations in this gene may help differentiate a horse better suited to sprints versus long-distance racing.

Beyond functional performance, gene editing also opens the door to phenotype modification, adjusting physical traits that contribute indirectly to racing ability. This includes aspects like limb length, back structure, stride angle, body mass distribution, and joint strength. Studies have identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and genes like TBX15 that influence skeletal development and muscle fiber differentiation.

By acting on these, one could refine the physical ideal standard of a horse to better match the ideal conformation for speed and biomechanics. This would mark a radical shift from traditional breeding, where physical traits emerge through generations of selection, to a scenario where conformation is engineered at the embryonic stage.

In essence, the application of gene editing in horse racing presents the theoretical possibility of designing equine athletes tailored not only for general fitness, but for specific racing distances, styles, and even track conditions. A genetically customised thoroughbred could, in theory, be built for explosive sprints, long-distance endurance, or optimal biomechanics on certain surfaces.

“Does the end justify the means?”

This timeless question, posed by Machiavelli centuries ago, feels strikingly relevant in today’s ethical debate over gene editing in sport horses. The growing scientific evidence that gene editing in horses is not only possible but increasingly feasible brings to the forefront a complex and deeply important moral dilemma. Just because we can manipulate the genome of a future equine athlete, should we?

At the heart of the discussion lies the fundamental value of fair play, a core principle that defines the legitimacy of competitive sport. If one horse is genetically enhanced before birth while others are bred through traditional means, can they still compete on equal terms? Gene editing, by its very nature, introduces an artificial advantage, one that is not earned through training, nutrition, or breeding judgment, but through direct technological intervention at the biological level.

Such practices risk turning the racecourse into a competition not of horses, but of laboratories and geneticists. The fairness of the sport would be compromised, not only for competitors but for owners, breeders, and spectators who trust in the authenticity of the contest. Moreover, equine athletes cannot give consent to be genetically modified. Altering their genome for human-defined goals raises profound questions about animal welfare, autonomy, and dignity. Is it ethical to “design” an animal for performance, knowing that such manipulation may also carry unknown health risks or reduce genetic diversity?

While innovation has always shaped sport, from training techniques to equipment, the line between enhancement and manipulation must be clearly drawn. Gene editing, when used for performance purposes, crosses that line. It challenges the spirit of horsemanship, the unpredictability of natural talent, and the integrity of racing itself. Ultimately, preserving fair play may mean accepting the biological limits of even the most elite Thoroughbreds and recognising that what makes sport meaningful is not control over the outcome, but the uncertainty of it.

Indeed, these ethical concerns have not gone unnoticed by the governing bodies of equine sport. Organisations such as the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA), and most notably the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) have already taken a firm and proactive stance against the use of gene editing for performance enhancement.

The BHA, in particular, is now leading the way globally in developing and implementing anti-gene doping protocols within its world-class equine anti-doping programme. In a decisive move to protect the integrity of British racing and the welfare of thoroughbred horses, the BHA has officially expanded its anti-doping operations to include routine testing for gene doping, both on raceday and out-of-competition.

This includes the detection of direct DNA manipulation via gene editing as well as gene transfer, where foreign genetic material is introduced into the horse’s cells to boost athletic traits or accelerate recovery.

Such practices are clearly prohibited under the Rules of Racing, and the BHA recognises gene doping as a serious and growing threat, not only to fair competition, but also to equine health and the future integrity of the breed.

To confront this emerging risk, the BHA has invested nearly £2 million in cutting-edge scientific research in collaboration with the LGC laboratory in Fordham, establishing a dedicated gene doping detection team as early as 2019.

In partnership with the Centre for Racehorse Studies, researchers at LGC have successfully developed analytical techniques capable of identifying evidence of gene doping, achieving UK Accreditation Service approval to perform this next generation of highly sensitive testing. This new gene doping detection framework is already active, forming part of a comprehensive testing programme that combines random sampling with intelligence-led investigations.

The goal is not only to ensure compliance with the Rules of Racing, but also to act as a powerful deterrent preserving the fairness of the sport and prioritising the welfare of the horse. With this initiative, the BHA is sending a clear message: that the use of genetic engineering to manipulate equine performance will not be tolerated, and that the tools now exist to detect and act upon it.

Gene-doping represents the current frontier of innovation and concern within the world of racing. While science continues to demonstrate the increasing feasibility of genetic intervention, both in theory and in practice, this progress brings with it a set of unresolved questions that extend beyond biology or regulation.

The potential to influence a horse’s genetic makeup with surgical precision is no longer a distant possibility, but a reality under active discussion. Yet, embracing such power uncritically could signal a shift in the very foundation of equestrian sport: from a celebration of natural ability, training, and partnership, to a controlled outcome engineered in a lab.

At its core, this conversation is not just about doping, it is about the boundaries between humans and nature, between technological capability and ethical restraint, and between competition and manipulation. The choices made now will shape not only the future of the sport, but also its meaning. As the line between what is possible and what is permissible becomes increasingly thin, the challenge will not only be to detect gene doping, but to decide, collectively, whether sport should allow itself to go down this path at all.