ETF AGM 2018

Click below to view

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer of the Quarter - Brian Ellison

The TRM Trainer of the Quarter award has been won by Brian Ellison. Ellison and his team will receive a selection of products from the internationally acclaimed range of TRM supplements as well as a bottle of fine Irish whiskey.

By Oscar Yeadon

A familiar face on Britain’s northern racing circuit, first as a jockey and then as a trainer for the last three decades, the Yorkshire-based team of trainer Brian Ellison has established itself as one of the most potent dual-purpose strings in Britain.

Since moving into his Spring Cottage Stables, in Malton, in the early 2000s, Ellison’s record on both the Flat and over Jumps has improved both in terms of quantity and quality. The last five years have been particularly fruitful, including breakthrough black type winners on the Flat and the emergence of stable star, Definitly Red.

This autumn Definitly Red has reaffirmed his credentials as a genuine contender for the Cheltenham Gold Cup in March, following an unbeaten start to the current season with Gr2 victories at Wetherby and Aintree.

In the 2017/18 campaign, Definitly Red finished sixth in the Gold Cup after winning the Cotswold Chase, but won’t take in that race en route to the Cheltenham Festival in 2019. “I thought at the time he had had a hard race,” remembers Ellison, “but he’s in great form this year and we’ll keep him for Cheltenham, possibly followed by the Aintree Bowl. If the ground’s good or good to soft, he has a chance.”

Definitly Red ridden by Danny Cook jumps the last fence before going on to win the Bet365 Charlie Hall Chase at Wetherby Races.

If Definitly Red offers Spring Bank Stables a live hope in the Gold Cup, their recent Gr3 Greatwood Hurdle winner Nietzsche could uphold the team’s honour over hurdles at the spring festivals.

“Nietzsche travelled great and did well at Cheltenham. The tongue strap has helped since last year and while we have to see what does in the meantime, he may go to Cheltenham, as he does like it round there.”

If it’s the jumpers who have been adding to the yard’s haul of black type winners, the Flat string hasn’t been far away. The 2018 flagbearer was the top-class juvenile filly, The Mackem Bullet, who twice finished second to Ballydoyle’s leading 1000 Guineas fancy, Fairyland, in the Lowther Stakes and Cheveley Park Stakes.

Ellison has been quoted as saying that The Mackem Bullet is the best horse he has trained, and she ended her season with a more-than-respectable sixth in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies’ Turf at Churchill Downs. “It was a great feeling to be at Churchill Downs. She was only beaten a length and a half for second, on soft ground. If it had been good, I think she would have been placed.”

The Mackem Bullet’s owner, Katsumi Yoshida, has kept his filly in the US where she may enter training or instead head to Japan to enter her owner’s breeding programme. Her departure leaves a sizeable hole to fill in the string for 2019, but Ellison is looking forward to the season ahead.

“At this moment in time, I think we have the best band we have ever had. Not necessarily of the quality of The Mackem Bullet, but the two-year-olds look nice, and we’re always trying to improve the quality of the string.”

Ellison’s enthusiasm is readily apparent but perhaps in a nod to his days in the saddle, you get the sense that his first love is National Hunt racing.

“I wish I had more jumpers; we have 30 or so at the moment, but in addition to Definitly Red and Forest Bihan, there is Windsor Avenue, who I rate very highly and should make a lovely chaser, and also Ravenhill Road.

“All you ever need as a trainer is one good horse.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Starting out - Gavin Hernon

By Gavin Hernon

It takes six hours door to door from my yard in Chantilly to Park Paddocks in Newmarket. I go there in the hope of coming away with a nice race filly for 2019.

Despite the friendly company of one of my mentors, Nicolas Clement, I can't help but feel that this is six hours of time that could be spent working through the huge workload that comes with running a racing yard.

It's been an eventful first four months in the training ranks, and I'm hugely indebted to my team to be able to say we've had four winners from just eight runners. I appreciate this is a strike rate that no trainer can maintain in the long term, but it's compensation for hard work from the team and for now it's a powerful marketing tool. When recently seeking advice from Andre Fabre regarding the start up plans I had in place, he advised me that the only marketing any trainer needs is winners.

I'm very much a goal-oriented person. For nearly five years, Nicolas Clement has been telling me that if I'm to meet my own high expectations I need to have at least 10 winners in my first 12 months. Just four months later, I feel we are on track but I'm tinkering with the idea of moving the goalposts.

December is set to be our busiest month to date on the track. With an intended runner in a couple of the remaining Listed races in the French racing calendar, I know what I want for Christmas.

Black-type is on my mind already. It’s the holy grail of this industry. It’s what we all dream of. It is so difficult to achieve but I know I have horses capable of it. As I stand on the side of the gallop waiting to see my string, there is no doubt in my mind that I will be disappointed if we fail to win a black-type race by this time next year.

Now that the stable has grown, getting systems and organisational structures in place has become more important.

I think if any of my past employers were to spend a morning with us, they would all see that parts of their training methods have left a lasting impression. Jim Bolger and Graham Motion in particular would both have cause to call it copyright.

Of course there have been setbacks and disappointments, but I've learned that you can't dwell on them. Repercussion missed his end of year target of the Prix Luthier (LR). The news wasn't overly surprising given he had been running since the Lincoln in March. The horse that took me to Arc day in my first year and gave me two wins at Chantilly will have a well deserved break on grass and will be back to 100% again for the 2019 season.

Nevertheless, making that type of phone call to an owner is a gut-wrenching feeling that I don't think I will ever get used to. Before now, I have only ever had to worry about the horse in this situation.

You have to move on, find the next opportunity; prevent the next setback from happening. Dwelling on these matters breeds negativity, inefficiency and serves no purpose to man or horse.

We took a huge risk setting up with just three horses in the middle of the season. I knew a good start leading into the European sales season was my best shot of gaining traction. Similarly, I was acutely aware that if I had nothing to show for it, I would struggle to attract investment. With current forecasts looking to be at 20 horses for the 2019 season, I feel the risk taken is starting to reap its rewards.

Rather surprisingly, I have close to 50 CVs sitting in a drawer in my office from people looking for work. No signs of the staff crisis in Chantilly it would seem. This has allowed me to be selective and form a hard working team of excellent riders who bond well.

We have signed Flavien Masse, who has ridden 55 winners, as our apprentice. Flavien served as an apprentice to Criquette-Head for a number of years.

The sales season has been hectic. Despite knowing my yard is in the excellent hands of my assistant John Donguy in my absence, I'm anxious to get back the moment I leave. It is at home where things need to go right first and foremost.

I have tried to get on sales grounds to assist current owners with their purchases as well as trying to meet as many potential owners as I can. I found this to be quite an alien concept at the start. Of course I had been used to trying to sell myself as an aspiring trainer, but the entire dynamic has changed. I don't have anybody paying me a wage anymore. Get this wrong, and there are consequences.

It was satisfying to see recent purchase Mutarabby win so impressively on his first French start in a competitive conditions race at Deauville. He wasn't at 100%, yet his performance showed that he is capable of at least Listed level and given his turn of foot, his stamina and his love of good ground, there is a race in Melbourne already on my mind should he progress in the manner I'm hoping.

2018 has been very good to me. We have a lot to look forward to next year and It is with great anticipation that my team and I batten down the hatches with plenty of dreams to keep us warm during the winter months.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Hindsight - Uwe Ostmann

By Peter Muhlfeit

Peter Muhlfeit spoke to Uwe Ostmann, who for four decades was a driving force in German racing, winning more than 1.600 races and who at the tender age of 78 still loves outdoor swimming and has a close eye on German racing.

You retired six years ago; how hard was it to give up racing?

It was tough for me as I was practically dealing my whole life with horses. But I live only a five-minute walk away from the racecourse and my former stable in Mulheim. I’m still in touch with the owners of Gestut Auenquelle, for whom I had plenty of success. I’m feeling well, do a lot of sport—cycling and swimming outdoors in a lake—and I watch a lot of racing. I hardly miss a racing day in Cologne.

How do you judge the current situation of German racing?

I’m actually quite optimistic that we will turn the tide, and better days are to come. If there is good weather and good racing, there are plenty of young people coming to watch the horses. But the racing clubs have to work to attract a new crowd. Cologne, Hannover and Hoppegarten are showing the way. But I realise that it is difficult to find sponsors and create the betting revenue to fund top racing.

What got you involved in racing in the first place?

I grew up in Detmold in North-Rhine-Westfalia, and there used to be a small racecourse in the Fifties. Bruno Schütz, one of our best trainers ever, did win a pony race back then. I was fascinated by the horses and wanted to do work with them. An uncle of mine helped me to get an apprenticeship with Sven von Mitzlaff when I was 15.

You learned the trade at the yard who has trained Germany’s only Triple Crown winner Konigsstuhl. What kind of man was Herr von Mitzlaff?

Herr von Mitzlaff was a really fine man—only on few occasions he raised his voice. The whole situation at the stable—we were six apprentices at the time—was very homely. We were raised and educated in a very good way...something that helps and stays with you your whole life.

Von Mitzlaff did win the German Derby seven times. You landed the Derby once—1988 with Luigi, ridden by Walter Swinburn. Was this the biggest moment of your training career?

Yes of course, despite the fact I trained plenty of other great horses. But a Derby win really puts you on the map, in the late Eighties even more so as the media attention was much bigger than it is now. And it was particular sweet for us that Luigi beat Alte Zeit, who was in training with me as a two-year-old and won the Preis der Winterkonigin for me. At three she raced for Hein Bollow. So I was very happy that we beat her and it wasn’t the other way round.

Gonbarda, homebred by Auenquelle, probably was the best filly you ever trained. She won two Gp1 races. What was so special about her?

She had real stamina and a big fighting heart. And even though she was a Lando-offspring she did not need any particular ground. She won the Gp1 Preis von Europa on soft ground. Gonbarda then was sold for big money to Darley Stud. Unfortunately she did not race again but produced some really good horses like the Champion Stakes and Lockinge Stakes winner Farhh.

You had a reputation of being particularly successful with two-year-olds. What was your secret?

I don’t have a secret, but I guess I trusted the good horses to go out early. Mandelbaum, who was unbeaten at two and three years, or Turfkonig, winner of eight Group races, were out three times at two, and it didn’t hurt their career. Today I feel that some trainers are a bit too timid in this respect.

How do you rate the current crop?

Noble Moon, winner of the Preis des Winterfavoriten, is well bred. Sea The Moon has done very well with his first year, and I’m convinced that there will be some good stayers out there by him. I’m anyway amazed that German breeding still manages to produce top horses on a regular basis despite its small base and the fact that we are selling plenty of our best horses abroad.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Marketing priorities across European racing

By Dr Paull Khan

MARKETING PRIORITIES ACROSS EUROPEAN RACING

Three issues that were commonly identified as challenges facing horseracing across Europe at the EMHF’s recent Seminar on “Marketing and Educational Initiatives”:

A worrying shortage of jockeys and stable staff

The broad requirement to raise racing’s profile and appeal; to grow the fan-base and drive ownership

A growing need to win over the hearts and minds of the wider community

Essentially, the marketing of our sport is handled often at a local racecourse or at a national level. Examples of international collaboration exist but are very much the exception. Thus, Racing Authorities, particularly in the “smaller” racing nations, are often working in isolation with limited opportunity to bounce ideas off each other or compare notes as to what has worked and what has not.

It was with this in mind that we invited EMHF members to gather together, to outline the current state of the racing industry in their respective countries and to present on one or two recent initiatives they had introduced. SOREC, the Racing Authority of Morocco, had kindly offered to host. At their National Stud in Bouznika in November we received presentations from countries as diverse, in racing terms, as Belgium, Czech Republic, Great Britain, Greece, Ireland, Morocco, Sweden and Turkey. Delegates from Poland and Spain also attended.

22 delegates from 10 countries attend the EMHF's Marketing & Educational Initiatives Seminar

The degree of commonality among the concerns of Racing Authorities big and small proved striking, and it made the various ideas and approaches being adopted to address them all the more fascinating and relevant.

The difficulty in finding jockeys was highlighted in several presentations. We need not look far, of course, for one reason for this: we live in times when the average weight of our species is rising, yet the same is not the case for the thoroughbred—limiting scope simply to increase the weights allotted. But there are doubtless several other factors at play here: a growing dislocation of the populace from the countryside and from animals, as well as a general decline in the profile and appeal of horseracing (among so many other traditional pursuits), etc.

Jockey shortage and development is one of the key issues facing the Belgian Galop Federation (BGF). Belgian racing is operating at a fraction of its scale a century ago: where there were a dozen racecourses then, there are but three today; where racing took place on a daily basis, there is now a fixture per fortnight. There are just 320 thoroughbreds in training and only 24 jockeys, with two apprentices. The BGF has adopted a combination of targeting those with a proven interest in riding, but not necessarily race-riding, with an innovative approach to jockeys’ training. Pupils at Belgium’s Riding and Horse Care School receive lectures on aspects of the jockey’s life and exposure to the mechanical horse. It is evident from many sports that few things encourage the recruitment of youngsters more effectively than having a home-grown star, and the development of Belgium’s riders has been a central concern of the BGF, which does not have the luxury of a jockey school and has struggled with the expense of sending pupils to such a facility abroad. Their solution: to bring the mountain to Mohammed. Arc- and Derby-winning jockey John Reid has been engaged to provide coaching to jockeys of all levels of experience. Over three days, twice a year, these riders gain the benefit of Reid’s experience, with video material and time on the simulator.

The Czech Jockey Club (CJC)—which, by the way, will reach its centenary in March—is an organisation adept at making its money go a long way. Despite the absence of any statutory funding from betting—41% of prize money is self-funded by the owners and 56% provided by sponsors—Czech racing still boasts 11 racecourses and some high-quality horses. Indeed, in recent years, the 1,000 or so horses in training have collectively picked up more money from foreign raids than the total available to them at home. So, when the CJC received a grant from their Ministry of Agriculture for a project to recruit children into the sport and particularly into their jockeys’ ranks, a great deal was done, despite the grant only amounting to less than €5,500. They targeted 8th and 9th grade children, their parents and educational advisors, in a combination of outreach visits and receiving groups of students, either at their racing school or during race meetings. The initiative garnered television coverage, and extensive use was made of social media to publicise it. How successful this project has been will become evident in March—the deadline for applications to the racing school for youngsters leaving school that summer.

Britain’s European Trainers’ Federation representative, Rupert Arnold, broadened the focus to the related issue of stable staff recruitment and retention. The difficulties being faced in Britain currently had been, he explained, a major driver in his introduction, as the chief executive of the National Trainers Federation, of a new Team Champion Award last year. With the aim of rewarding good management in a trainer’s yard—a standard dubbed “The Winning Approach” was devised, covering many aspects of the way a trainer runs their business. To encourage adoption of the standard, an award, (or, more accurately, two awards—one for larger yards and one for those with up to 40 horses) was put up, with the assistance of sponsorship from insurers Lycett’s. Importantly, these awards were—as their name suggests—for the whole team rather than the trainer alone. The amount of £4,000 went to the winning stable, and the yards that entered were asked to say how they would spend their winnings, if successful. So that the benefits are spread wider than the two victorious stables, a star rating system has also been introduced, providing trainers with a promotional tool. It is hoped that these Team Awards will create a virtuous circle, with more yards adopting best practice, thereby creating a better working environment for staff, increasing staff satisfaction and, ultimately, retention.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Ulcer medication: are the products to treat that different?

By Celia Marr

Stomach ulcers are not all the same

Racehorse trainers and their vets first began to be aware of stomach ulcers over 20 years ago. The reasons why we became aware of ulcers are related to technological advances, which produced endoscopes long enough to get into the equine stomach. At that time, scopes were typically about 2.5m long and were most effective in examining the upper area of the stomach, which is called the squamous portion. Once this technology became available, it was quickly appreciated that it is very common for racehorses to have ulcers in the squamous portion of the stomach.

Fig 1. The equine stomach has two regions: the upper region is the squamous portion and the lower region is the glandular portion. The squamous portion is lined by pale pink tissue which is susceptible to acid damage. The glandular portion is lined by darker purple tissue. Acid is produced in this region. In this horse, the stomach lining is healthy and unblemished. The froth is due to saliva which is continuously swallowed.

The equine stomach has two main areas: the squamous portion and the glandular portion. The stomach sits more or less in the middle of the horse, immediately behind the diaphragm and in front of and above the large colon. Imagine the stomach as a large balloon with the oesophagus—the gullet—entering halfway up the front side and slightly to the left of the balloon-shaped stomach and the exit point also coming out the front side but slightly lower and to the right side. The tissue around the exit—the pylorus—and the lower one-third, the glandular portion, has a completely different lining to the top two-thirds, the squamous portion.

The stomach produces acid to start the digestive process. Ulceration of the squamous portion is caused by this acid. Like the human oesophagus, the lining of the squamous portion has very limited defences against acid. But, the acid is actually produced in the lower, glandular portion. The position of the stomach is between the diaphragm, which moves backwards as the horse breathes in and the heavy large intestine which tends to push forwards as the horse moves. During exercise, liquid acid produced at the bottom of the stomach is squeezed upwards onto the vulnerable squamous lining. It makes sense then that the medications used to treat squamous ulcers are aimed at blocking acid production.

Lesions in the glandular portion of the stomach are less common than squamous ulcers. The acid-producing glandular portion has natural defences against acid damage including a layer of mucus and local production of buffering compounds. At this point, we actually know relatively little about the causes of glandular disease, but it is becoming increasingly obvious that disease in the glandular portion is very different from squamous disease. Often, it is more difficult to treat.

Fig 2. This horse shows signs of discomfort. She carries her head low, her ears are back a little, and the muscles of the face are clenched, affecting the shape of the nostrils and eye.

Stomach ulcers can cause a wide range of clinical signs. Some horses seem relatively unaffected by fairly severe ulcers, but other horses will often been off their feed, lose weight, and have poor coat quality. Some will show signs of abdominal discomfort, particularly shortly after eating. Other horses may be irritable—they can grind their teeth or they may resent being girthed. Additional signs of pain include an anxious facial expression, with ears back and clenching of the jaw and facial muscles and a tendency to stand with their head carried a little low.

Assessing ulcers

Ulcers can only be diagnosed with endoscopy. A grading system has been established for squamous ulcers, which is useful in making an initial assessment and in documenting response to treatment.

Grade 0 = normal intact squamous lining

Grade 1 = mild patches of reddening

Grade 2 = small single or multiple ulcers

Grade 3 = large single or multiple ulcers

Grade 4 = extensive, often merging with areas of deep ulceration

Fig 3. Grade 1 squamous ulcers which are mild patches of reddening.

Fig 4. Grade 2 squamous ulcers—there are several of these, but they are all small.

Fig 5. Grade 3 squamous ulcers—these are larger, and there are several.

Fig 6. Grade 4 squamous ulcers—there are extensive deep ulcers with active haemorrhage.

Although it is used for research purposes, this grading system does not translate very well to glandular ulcers where typically, lesions are described in terms of their severity (mild, moderate or severe), distribution (focal, multifocal or diffuse), thickness (flat, depressed, raised or nodular) and appearance (reddening, haemorrhagic or fibrinosuppurative). Fibrinosuppurative suggests that inflammatory cells or pus has formed in the area. Focal reddening can be quite common in the absence of any clinical signs. Nodular and fibrinosuppurative lesions may be more difficult to treat than flat or reddened lesions. Where the significance of lesions is questionable, it can be helpful to treat the ulcers and repeat the endoscopic examination to determine whether the clinical signs resolve along with the ulcers.

Fig 7. The glandular tissue around the pylorus (or exit point) has reddened patches. This is of questionable clinical relevance, and many horses will show no signs associated with these lesions.

Fig 8. There are dark red patches of haemorrhage in the glandular tissue of the antrum—the region adjacent to the pylorus—which is the dark hole toward the bottom of this image.

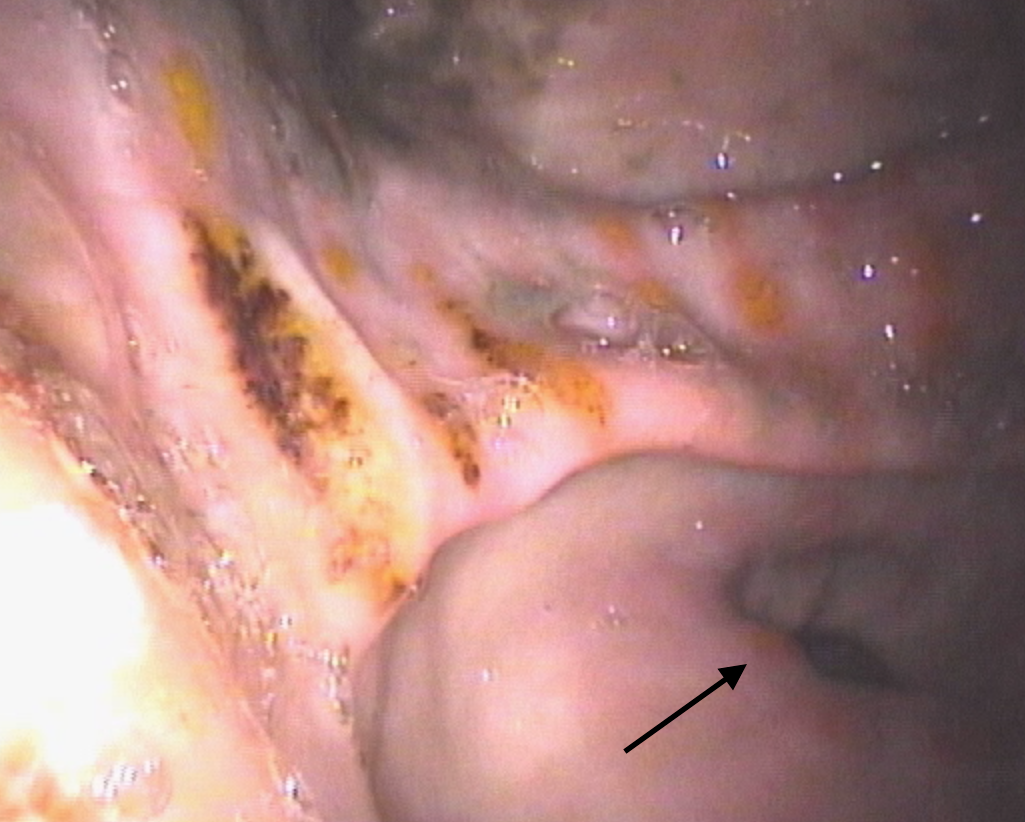

Fig 9.This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. There are depressed suppurative (yellow) areas several of which also have haemorrhage. Nearer to the pylorus there is reddening and raised, swollen areas (arrow).

Fig 10. This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. The majority of lesions are depressed and haemorrhagic.

Medications for squamous ulcers

Because of the prevalence and importance of gastric ulcers, Equine Veterinary Journal publishes numerous research articles seeking to optimise treatment. The most commonly used drug for treatment of squamous ulcers is omeprazole. A key feature of products for horses is that the drug must be buffered in order to reach the small intestine, from where it is absorbed into the bloodstream in order to be effective. Until recently only one brand was available, but there are now several preparations on the market and researchers have been seeking to show whether new medicines are as effective as the original brand. There is limited information comparing the new products, and this information is essential to determine whether the new, and often cheaper, products should be used.

A team of researchers formed from Charles Sturt University in Australia and Louisiana State University in the US has compared two omeprazole products given orally. A study reported by Dr Raidal and her colleagues, showed that not only were plasma concentrations of omeprazole similar with both products, but importantly, the research also showed that gastric pH was similar with both products and both products reduced summed squamous ulcer scores. Both the products tested in this trial are available in Australia and, although products on the market in UK have been shown to achieve similar plasma concentrations and it is therefore reasonable to assume that they will be beneficial, as yet, not all of them have been tested to show whether products are equally effective in reducing ulcer scores in large-scale clinical trials. Trainers should discuss this issue with their vets when deciding which specific ulcer product they plan to use in their horses.

Avoiding drugs altogether and replacing this with a natural remedy is appealing. There is a plethora of nutraceuticals around and anecdotally, horse owners believe they may be effective. One such option is aloe vera that has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and mucus stimulatory effects which might be beneficial in a horse’s stomach. Another research group from Australia, this time based in Adelaide, has looked at the effectiveness of aloe vera in treating squamous ulcers and found that, although 56% of horses treated with aloe vera improved and 17% resolved after 28 days, this compared to 85% improvement and 75% resolution in horses given omeprazole. Therefore, Dr Bush and her colleagues from Adelaide concluded treatment with aloe vera was inferior to treatment with omeprazole.

Medications for glandular ulcers….

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Ride & Guide - which bits work best and what to use when

By Annie Lambert

It is a daily challenge for horsemen to put together bit and equipment combinations that draw out the maximum prowess of their trainees.

Bits and related training accessories are not all they depend on, however. The talented exercise riders they hire represent the hands using those bits, an important factor in the process.

Whatever bits and riggings a trainer prefers, they have a logical reason as to why their choices work within their programme. A lot of that reasoning is chalked up to trial and error experiences.

Bit Bias

Some bits are legal for training and racing while others are not allowed in the afternoons. The most recognisable of the morning-only headgear would be the hackamore. Using a hackamore requires approval from officials.

Danny Hendricks inherited his father’s talent for handling horses. His father toured the rodeo circuit performing tricks.

California trainer Danny Hendricks’ father and uncle, Lee and Byron Hendricks respectfully, toured the rodeo circuit with specialty acts, trick riding and Roman jumping over automobiles. They were superior horsemen that began retraining incorrigible racehorses. The brothers introduced many bits that race trackers had not yet explored. Danny was too young to remember those bits, but did inherit the Hendricks’ talent.

“I had a filly for Dick [Richard Mandella] way back that wouldn’t take a bit; she’d just over flex,” he explained. “If you just touched her she’d put her nose to her chest and go straight back. I put a halter on her with a chifney, so it just hung there, put reins on the halter and started galloping her. It took months before she’d finally take that bit.”

The majority of trainers shrug off which bits are not allowed in the afternoons as they are not devices they’d think of using anyway. In fact, most trainers never ponder “illegal” bits.

Based in Southern California, Hall of Famer Richard Mandella personally feels it’s easy to make too much out of bits. He prefers to keep it simple where possible and to change bits occasionally, “so you put pressure on a different part of the mouth.”

ABOVE: One of the most used snaffles is the D bit, while the Houghton (R) is reserved for horses difficult to keep straight

“I don’t want to hear a horse has to have a D bit every day or a ring bit every day,” Mandella offered. Adding with a chuckle, “It’s good to change what you’re doing to their mouth, which usually isn’t good with race horses.”

Mandella learned a lot from a Vaquero horseman, Jimmy Flores, a successful stock horse trainer. His father was shoeing horses for Flores, who encouraged Mandella, then eight or nine years old, to hack his show horses around.

“Jimmy would put a hackamore on them, to get the bit out of their mouth,” Mandella recalled. “He said to me once, ‘You don’t keep your foot on the brake of your car, you’ll wear the brakes out.’ He was a great horseman.”

Trainer Michael Stidham introduced Mandella to the Houghton bit, which originally came from the harness horse industry.

“The Houghton has little extensions on the sides and it is like power steering,” Mandella said. “As severe as it looks, it’s not hard to ride. We’ve had a lot of luck with horses getting in or out, it corrects them.”

David Hofmans, a multiple graded stakes winning trainer, did not come from a horse background. He fell in love with the business when introduced to the backside by Gary Jones and went to work for Jones’ father, Farrell, shortly after.

“We’re always trying something different if there is a problem,” Hofmans said of his tack options. “I use the same variety of ring bits and D bits with most of our horses. We use a martingale, noseband and sometimes a shadow roll. If you have a problem you try something different, but if everything is okay, you stick with what works.”

Michael McCarthy spent many years working for Todd Pletcher before moving his base to California. When it comes to bits, he hasn’t varied much from his former boss. McCarthy reminded, “When the horses are comfortable, the riders are more relaxed and everybody gets along better.”

“Most horses here just wear a plain old, thick D bit,” he said from his barn at California’s Del Mar meet. “Some of the horses get a little bit more aggressive in the morning, so they wear a rubber ring bit. In the afternoons, if we have one that has a tendency to pull, we may put a ring bit with no prongs.”

McCarthy discovered the Houghton bit in Pletcher’s where they used it on Cowboy Cal, winner of the 2009 Strub Stakes at Santa Anita. He uses the Houghton sparingly to help horses steer proficiently.

Louisiana horseman Eric Guillot said from his Saratoga office that he uses whatever bit a horse needs—a lot of different equipment combinations.

“I use a D bit with a figure 8 and, when I need to steer them, a ring bit with figure 8 or sometimes I use a ring bit with no noseband at all,” he offered. “Sometimes I use a cage bit and I might use a brush [bit burr] when a horse gets in and out. Really, every situation requires a different kind of bit.”

Control Central

An early background riding hunters and jumpers has influenced the racehorse tack choices of Carla Gaines.

“I like a snaffle, like an egg butt or D bit, or something that would be comfortable in their mouths,” she offered. “I use a rubber snaffle if the horse has a sensitive mouth. I don’t like the ring bit because it is extra [bulk] in their mouth.

“A lot of the jockeys like them because they think they have more control over them. I know from galloping that it doesn’t make them any easier; it probably makes them tougher.”

The beloved gelding John Henry will forever be linked with his Hall of Fame trainer, Ron McAnally. The octogenarian has stabled horses at the Del Mar meeting since 1948. From his perch on the balcony of Barn one he surveyed the track and pointed out changes he has seen made over his 70-year tenure there. During those years there have been fewer changes in the equipment he uses than those stable area enhancements.

“Basically a lot of the bits are still the same; they’ve been that way for I don’t know how many years,” he recalled. “Occasionally you’ll find a horse that tries to run out or lugs in, and they’ll put in a different kind of bit.”

According to McAnally’s long-time assistant trainer, Danny Landers, things stay uncomplicated at the barn.

John Sadler’s training habits have also been influenced by his days showing hunters and jumpers. Although he uses the standard bits, decisions are often made by the way horses are framed and balanced.

“I want to see horses carry themselves correctly,” he said. “I’ve always had really good riders since I’ve been training. That is very important to me.”

Sadler likes one of the more recent bits, the Australian ring snaffle, which helps with steering. The bit has larger cheek rings, which helps prevent pinching. He also employs a sliding leather prong.

British born Neil Drysdale, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2000, has been in the states his entire training career. His tack room is one of those treasure troves of equipment, much of which he has only used a time or two. He keeps choices simple and prefers to match each horse to the best bit for the individual.

A shadow roll, used to lower horses’ heads, hang over a rubber ring bit

“I’m not actually keen on the D bit,” he acknowledged. “I think it is quite strong. Every now and again you have to use something stronger, and we’ll use a ring bit or an Australian ring bit, which is quite different and I think it works very well. We have a Houghton which I use rarely; you hope you don’t get those problems and need it.”

No one will ever accuse Louisiana-bred trainer Keith Desormeaux of being anything less than frank when asked his opinion.

“I’m not a big believer in bits,” he said. “Being a former exercise rider, I have my own strong opinions about bits. My strong opinion is that they are useless. My personal preference is a ring bit, because they play with it, not because of its severity. People use it to help with control; you pull on the bit and the ring pushes on the palate.

“When horses play with the ring bit it diverts their attention from all that’s going on around the track. I don’t take a good hold; it just diverts them from distractions going on around them.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Brexit update planning - looking to the Swiss model

By Lissa Oliver

At time of going to press we do know with certainty that Britain has officially left the EU and the EU has agreed the Brexit deal put forward by Theresa May. That should by now be the end of the story, but of course it continues to be only the beginning.

As Tim Collins warned during his speech at the recent World Horse Welfare Conference, whatever the daily outcomes of post-Brexit, “You mustn’t take your eye off the ball and assume it will all be sorted in the next three or four months. Temporary measures last longer than you might think.” He cited Income Tax, an emergency short-term measure introduced in Britain to fund the Napoleonic Wars, and reminded us of two “temporary” structures – the Eiffel Tower and the London Eye!

He pointed out the power we have in lobbying when it comes to animal welfare, one of the biggest issues young voters care about and therefore one of the biggest areas of concern to all political parties.

“The horse industry’s strongest argument is that the horse’s welfare will be badly affected by any delay at ports. Politicians will have to listen to this point. The EU know they are facing critical parliamentary elections and you have a very powerful issue,” Collins said of the movement of horses, pointing out we would be “pushing on an open door.”

His advice was clear. “Focus your campaign on the detail, not the general issues. Campaign on values, not economics. The biggest issue is not being talked about – there is already an EU border between Bulgaria and Turkey and it can take up to six hours for animals to be moved from either side. This is an issue that needs to be at the front and centre of awareness in a way that it is not.”

He concluded, “If you campaign on those points I promise you, you will prevail.”

Already, the racing industry is familiar with some of the documentation needed at border checks, with horses travelling to race in Switzerland. White Turf Racing Association, St Moritz, reminds you of the customs requirements and advises, for a smooth procedure at customs, the following documents have to be provided to the customs clerk:

Passport of the horse

Health certificate TRACES or Annex II

ATA Carnet (international customs document that permits the tax-free and duty-free temporary export and import – to be asked at the International Chamber of Commerce)

The ATA Carnet must be stamped at both customs (abroad and Switzerland) for both the outward journey and the return journey.

Paul Marie Gadot, Direction Opérationnelle des Courses and Chef du Département Livrets Contrôles, tells us that the High Health document, which it is hoped may replace the Tripartite Agreement, is still being negotiated and given Gadot’s determination and the positive view of Tim Collins, we should be optimistic about the outcome.

“We are continuing to work on the subject and we will do it until we get satisfaction,” Gadot tells us. “The HHHS dossier has been transmitted to the EU Commission. The Delegated Acts of the EU Animal Health Law regarding movements of horses aren’t yet finalised and if the horse movement in between the EU member countries seems to be correctly integrated, we need to obtain some progress on the horse movements between third countries and the EU.

“Our Brexit team in the three countries (Ireland, UK and France) has prepared a complementary document explaining all our health procedures in breeding and racing, which fully demonstrates and guarantees the high health status of our horses. This complementary document will be presented to EU Commission representatives at the beginning of December.

“Because UK’s Brexit deal has been agreed by the EU Commission and the EU countries, we may hope that, if the UK Parliament votes the deal, we will maintain the Tripartite Agreement during the transition period. If it isn’t validated by the UK Parliament, even if we are working on practical solutions on the field level, the situation will be very difficult.”

Ireland has already adopted a new measure to assist and support any HHHS agreement. Coming into effect from January 2019 is Ireland’s new 30-day foal notification, which will be a mandatory obligation. Irish breeders are required to notify Weatherbys Ireland General Stud Book within 30 days of the birth of a thoroughbred or non-thoroughbred foal born in Ireland and bred for racing. The notification of birth will be automatically triggered by the submission of DNA (blood and markings).

HRI sees the mandatory 30-day foal notification as integral to the welfare and traceability mandate for the equine industry and believes it will assist in the proviso for life after Brexit, particularly with regards to the free movement of horses.

It will also enable HRI and the IHRB, on behalf of the industry, to trace the whereabouts of thoroughbreds and non-thoroughbreds in Ireland from the earliest stage. This is important for the welfare, biosecurity and disease control measures which underpin horse movement and are the cornerstone of European legislation for equines.

Jason Morris

Jason Morris, HRI Director of Racing, explains “The move to a 30-day foal notification is an important step in ensuring that we have full lifetime traceability of all thoroughbreds for health and welfare reasons. HRI warmly welcomes its introduction which has the widespread support of the industry.”

Shane O’Dwyer

Shane O’Dwyer, CEO ITBA, is in full agreement. “The ITBA welcomes the 30-day foal notification as a positive move that will assist in our efforts for the Codes of Practice and the High Health Horse Concept to be used as the basis of continued, uninterrupted free movement of thoroughbred horses post-Brexit.”

Difficulties with Northern Ireland are unlikely to be resolved in the short-term, but the Irish thoroughbred industry does have the full support of its government.

An Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, stated on the EU-agreed Brexit deal on 18 November, “I am pleased an agreement has been reached between EU and UK negotiators on a draft Brexit Withdrawal Treaty. Our national priorities are:

protecting the Good Friday Agreement.

maintaining the Common Travel Area and related benefits

reaffirming our place at the heart of the EU

protecting trade, jobs and the economy

“On each of these, we have reached a satisfactory outcome today. Avoiding a hard border has proven to be one of the most difficult challenges. What has become known as ‘the backstop’ is now fully spelt out in the Withdrawal Agreement. The backstop would apply “unless and until” a better solution is agreed.

“The legal text ensures that Ireland and the UK can continue to operate the Common Travel Area and the related benefits for our citizens. We are working closely with the UK Government to ensure that this happens smoothly.

“The text also underpins the fundamental rights enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement, and the birth right of citizens of Northern Ireland to identify as Irish, and therefore as European citizens, and so to enjoy the rights and freedoms that come with EU citizenship.”

Varadkar also acknowledged, “The text also allows for a possible extension of the transition period beyond the current end date of December 2020.” Once again, Collins’ forewarning of temporary measures keeps the uncertainty rolling over!

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Understanding Trainers’ mental health

By Lissa Oliver

There is no doubt that the welfare of the horse is important and the public perception of how we care for the horse in training and on retirement impacts directly on the level of support we can expect from sponsors, racegoers and governments. The care of the horse, however, is wholly dependent upon those it is entrusted to and they are the ones who have often been neglected.

Racing Welfare was founded in the UK in 2000 and the service was expanded in 2014. In Ireland, the Industry Assistance Programme (IAP) was launched in 2016 and receives great publicity from Irish racing publications. Both support systems are easily accessed and provide a free and confidential 24-hour service, seven days a week, for everyone working, or who has previously worked, within the thoroughbred industry and their immediate family members.

Sadly, this is not the case elsewhere, but not from want of need. Many German trainers feel the wellbeing of industry professionals in German racing is sadly ignored. If the Direktorium has any regard or respect for stable staff, it is escaping without notice.

“At the Baden-Baden meetings, the stable staff are still living in squalor by today’s standards,” one trainer, who prefers not to be named, tells us. “Jockeys with welfare or alcohol problems are pushed aside and never heard of again. There is no Injured Jockeys Fund, no helplines or advice for a future career. For this day and age that is a really shameful state of affairs.

“It’s time these issues were aired. After all, without our dedicated workforce we have no racing. I have personally helped various people from the industry who have fallen on hard times, even in one case an attempted suicide, and have received no support. It has reached a point where I now only run horses in France when at all possible, I have lost all faith in German racing.”

That really is a damning indictment, particularly as one trainer went so far as to say that their support of an industry professional who had hit rock bottom earned them nothing but derision. It is interesting, too, that none of these individuals wanted to be named. Not for their own modesty, but in respect of the confidentiality of those they had helped.

This same sense of a lack of care and concern was reiterated by a French trainer unaware of AFASEC (www.afasec.fr), a service for racing and breeding professionals. AFASEC (Association of Training and Social Action Racing Stables) was commissioned by France Galop and the French Horse Encouragement Society in 1988 for the training and support of employees of racing stables throughout their career path. The association is managed under the double supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

AFASEC ensures the training of future employees through the French Horse Racing School and offers support to employees throughout their professional life. Five social workers and two social and family economics counsellors are at the disposal of 4,000 French racing professionals. Their mission is to inform, help and support in their professional and personal lives. The social workers can then refer those looking for support to relevant services.

The lack of awareness of this service among some French trainers suggests that more publicity is needed to ensure every racing industry professional has the necessary contact details and can avail of this service when required. The need for trainers to make such services known and displayed in the yard is paramount.

The confidentiality of the support network set up in Britain and Ireland is vital to its success, and Racing Welfare and HRI/CARE prefer not to reveal figures regarding the number of individuals who have availed of the service. However, Racing Welfare supported more than 2,200 people in 2017 with a wide range of challenges, which represents a significant proportion of racing’s workforce.

One trainer who is happy to discuss the help she received from the IAP is Clare Cannon, in County Down, Northern Ireland. She holds a Restricted Licence, with only four horses in her yard, and struggles to make her business pay.

Clare Cannon

Following the particularly harsh winter and spiralling costs, coupled with the retirement of her best horse, Cannon considered giving up and joining the many Irish trainers to have relinquished their licence this year.

“It doesn’t matter how big or small a trainer is, the problems are the same—just on a different scale,” she points out. “A lot of things had happened to me on top of each other. It reached a point when I thought, ‘why am I even doing this’? The biggest thing is that since going to the IAP I’ve had such a great season. If I’d not got help and I’d given up, I would have been watching someone else having a great year with my horses.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

The FEI prohibited list and what it means for racing

By Alysen Miller

The eighth World Equestrian Games in Tryon, North Carolina were not, it is perhaps fair to say, an unbridled success. From unfinished facilities to misspelt signage and, most catastrophically, an entire endurance race that had to be aborted after riders were sent in the wrong direction, the competition generated so much negative coverage that the future of the Games themselves, already in some doubt, now appears to be hanging by a thread (At the time of writing, no formal bidders had thrown their hats into the ring for the 2022 renewal). So it might seem to be a strange time to ask if horseracing has anything to learn from the Fédération Équestre International (FEI). And yet, there is one area in which the FEI is arguably setting an example.

Unlike the global racing industry, which operates under myriad rules and regulations between different countries (and sometimes within the same country), all 134 affiliated nations of the FEI operate under a single set of rules. This includes a single Prohibited Substances Policy to which all jurisdictions must adhere; meaning that a horse trained in Australia is subject to exactly the same medical requirements, including regulations governing banned substances and threshold limits, as a horse trained in, say, America. This stands in stark contrast to the thoroughbred industry. Despite being an increasingly global game, from the now-traditional annual American invasion of Royal Ascot to the recent domination of the Melbourne Cup by European-trained horses, racing can appear positively parochial when it comes to its attitudes towards prohibited substances. “If you compare horseracing to other sports, we have one of the sole sports where there are no equal regulations on the highest level,” elucidates Germany’s Peter Schiergen. “To have [the same] regulations and policies around the world would be a good action for horse racing.”

So what are the factors standing in the way of global harmonisation, and would there ever be a case for following the FEI’s lead and adopting a single set of rules that would apply to horseracing authorities the world over?

Laboratory sample analysis

The FEI’s approach is to divide prohibited substances into two categories: banned substances (that is, substances that are deemed by the FEI to have no legitimate use in competition and/or have a high potential for abuse, including all anabolic steroids and their esters), which are not permitted at any time; and controlled medication (substances that are deemed to have a therapeutic value and/or are commonly used in equine medicine), which are not permitted for use during competition but may be used at other times. These categorisations apply to all national and international competitions, with each national federation being subject to the FEI’s regulations. Testing at competitions is carried out by the FEI’s own veterinary department, while elective out-of-competition testing is also available so that those responsible for the horse can ensure that they allow the appropriate withdrawal times for therapeutic medications. So just how effective are these rules at keeping prohibited substances out of the sport and ensuring a level playing field? Clearly, no system is perfect. The FEI has had its fair share of doping scandals, particularly in the endurance discipline, where stamina, which can be easily enhanced with the aid of pharmacology, is of paramount importance. The FEI, who declined to be interviewed for this article, said in a statement: “Clean sport is an absolute must for the FEI and it is clear that we, like all International Federations, need to continue to work to get the message across that clean sport and a level playing field are non-negotiable. All athletes and National Federations know that regardless of where in the world they compete the rules are the same.” Yet having a global policy does appear to offer a strategic advantage to those seeking to create a level playing field, not only through the creation of economies of scale (the FEI oversees laboratories around the world, and all results are all handled at the federation’s headquarters in Lausanne), but also by creating a framework for cheats to be exiled from all competitions, rather than just one country’s.

While harmonisation and cross-border cooperation does exist in racing, particularly within Europe and individual race meetings—notably the recent Breeders’ Cup—have taken it upon themselves to enact their own programme of pre- and post-race testing, effectively creating their own anti-doping ecosystem; the fact remains that racing lacks an overarching prohibited substances policy. Codes and customs vary widely from—at one end of the spectrum—Germany, which does not allow any colt that has run on declared medication to stand at stud; to North America, where, Kentucky Derby winner Big Brown, whose trainer admitted that he gave the colt a monthly dose of the anabolic steroid, stanozolol, is still active at stud. Stanozolol is the same drug that the Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson tested positive for in 1988, causing him to be stripped of his gold medal in the Seoul Olympics. Although the industry subsequently moved to outlaw the drug for use on horses in training, anabolic steroids are still routinely used as an out-of-competition treatment in a number of states.

“I don’t think the playing field is level,” says Mark Johnston, with typical candour. “Control of anabolic steroids is very important if you want a level playing field. Because there’s no doubt whatsoever that there are advantages to using them.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Is all-weather racing no longer the poor relation?

By Amy Lynam

For much of 2018, racing fans waited with bated breath for the return of Enable. Musings on when and where the wonder mare would reappear were many and varied, but few predicted that the Arc De Triomphe heroine would make her seasonal debut at Kempton on the polytrack surface.

Almost two years prior, the regal Juddmonte homebred, who had garnered high regard at home, made her very first racecourse appearance on Newcastle’s Tapeta track. That fateful day was the 28th of November 2016, when, of course, flat racing had left the turf for the winter months, narrowing John Gosden’s choice to two: run his future star on the all-weather, or not until March.

Enable winning the Arc de Triomphe

Gosden did, however, have turf options in September of 2018, and when quizzed on the decision to run a then five-time Gp1 winner on the all-weather, he had no hesitation: “We had aimed Enable at York, but it came about a week or ten days too early, so Kempton came at exactly the right time. The fact that it was on the all-weather didn’t concern me, as I knew exactly what I was going to get.”

For Enable’s return in the Gp3 September Stakes, the going was described as standard to slow, whereas on the very same day, Ascot raced on good to firm (good in places), while the going at Haydock was heavy. There are few surprises in the going on the all-weather; after all, the clue is in the name, and its consistency is very much appreciated by John Gosden, who says, “When the ground goes too firm in the summer, or during drought, or it becomes bottomless at the end of autumn, the all-weather is a nice place to be. It’s consistent, with bounce, and you can ride a proper race on it.”

It would, however, be unfair to look at all-weather racing as one entity, with “all-weather” encompassing various surfaces, mainly fibresand, polytrack and Tapeta™. Not only this, but each racecourse has its own shape and quirks, as well as its own race programme. Just as on the turf, no two courses are the same.

INSERT TABLE

Gosden is just one trainer who, unsurprisingly, has some favourites, as he shares, “The all-weather track I like the most is Newcastle; it’s very fair and has a good Tapeta surface. It has always been a fair, sweeping course; there are not too many hard luck stories there.” His favour for other all weather tracks is not quite so strong, as he continues, “There’s no doubt that at the likes of Lingfield, you get some unevenly-run races, where they slow the pace down early on and sprint in the straight.”

The opinions of trainers on particular tracks undoubtedly has a great influence on what horses, including what standard of horse, they will run at each. Though he has less hands-on experience with the all-weather racecourses in the UK, French-based trainer John Hammond is impressed by the surface at Lingfield, saying, “I have walked the all-weather track at Lingfield, and it is ‘night and day’ when compared to the all-weather tracks in France.”

When discussing all-weather racing, Hammond is keen to stress the importance of how each track is managed. “All-weather tracks need to be very well maintained and managed by very good groundsmen. I don’t think they pay enough attention to these tracks in France, and they often get too quick.” Hammond could not recommend French all-weather courses’ consistency as Gosden had, as he says, “The all-weather tracks here vary considerably. I wouldn’t mind running a good horse at Lingfield, or Kempton, but Chantilly can be a bit quick.”

All-weather surfaces have been touted for their lack of fatal injuries, but John Hammond sees a different type of injury on all-weather tracks, and this is one of the reasons he does not have many runners on the surface. “I do think young horses suffer from racing on the all-weather,” he says. “I see an increase in bone bruising to the hind cannon bone due to the fact that there is no slippage on synthetic surfaces.” Hammond gained experience in California before taking out his training licence, which has had some effect on his views. “America has torn up most of it’s all-weather tracks. They may have been applauded for fewer fatal injuries, but bone bruising causes intermittent lameness. This can leave a horse runnable but not performing at its best.”

When questioned on potentially running his stable stars on the all-weather, Hammond said, “I wouldn’t be keen on running my top horses on the all-weather in France. If the French all-weather tracks were a bit softer, I might be more keen on it. It didn’t do Enable any harm!”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer Profile - Jessica Harrington

By Lissa Oliver

Some towns are all about the horse, the vast number of racing stables in the one place defining the community that has sprung up among them. Wherever there is a racing centre there are racing people at its heart. The tiny village of Moone is slightly different. There is only one stable in Moone, but that stable is the beating heart of the community.

The County Kildare village is home to the Commonstown Stables of Jessica Harrington, and the success of the yard has sent ripples of prosperity throughout south Kildare and the Wicklow border. Harrington herself might refute that, but Seamus O’Reilly, a local business owner, will beg to differ. He has witnessed a tide of changes in his 40 years at nearby Crookstown, where he owns and runs a now-thriving service station and shop, and he understands better than most the economic impact of a racing stable that has grown to be the area’s largest employer.

“I started the service station in 1978 and this area of South Kildare was unknown then. It was hard to give directions to anyone, no landmarks, they wouldn’t know where to find us, we were tucked away from anywhere,” he recalls. “Things have improved in the last 20 years and it’s more accessible now. It’s a huge bonus to the service station and retail business to have Jessie there; a lot of her employees come in, plus visitors such as her jockeys and owners and the media. The spin off from her success is great.”

It’s interesting to reflect that, about a 40-minute drive away in County Carlow, trainers Jim Bolger and Willie Mullins are the biggest employers in that particular county, so the importance of horseracing to Ireland’s rural heartland can never be underestimated.

Moone has no pub, no post office and no shop; although since the closure of the post office, some of the residents opened and run a part-time community shop. The village may be home to the historic Celtic High Cross, but there is otherwise nothing to bring people here. Except, of course, Commonstown Stables and the stars within.

Don’t get this wrong though, JHR couldn’t be better sited. Moone may be off the radar for many, but a new network of roads and bypasses links it quickly and smoothly with the nearby motorways serving Cork, Tipperary and Dublin, with the Dublin and Rosslare ports accessible within an hour. At home, the horses nestle in the idyllic peace of a secluded part of Kildare, and their journey to the racecourse is just as smooth and comfortable.

It’s a traditional stableyard with a comfortable rustic ambience that blends seamlessly with the more state-of-the-art features that are part of a modern racing establishment. Yet it’s also a production line of Group One and Grade One winners, at the centre of an industry.

“It’s like a small factory,” Harrington’s son-in-law, Richie Galway, observes, as Harrington sits with her family and gives some thought to how her business sits within the community. He recently took a backseat in his managerial role at Punchestown racecourse to devote those skills more fully to JHR (Jessica Harrington Racing), very much a business operation.

“Lots of our staff come in from Castledermot; a lot of them live there,” Richie points out. “There are a few who live here in Moone, but most travel in each day.” Castledermot is a bigger village 20 minutes away, with plenty of local shops, but most of its residents face a daily 90-minute commute to jobs in Dublin city centre.

The Irish rural landscape is changing at a quickening pace, with the so-called commuter belts widening and isolating communities. New housing estates replacing the farmland that no longer pays its way are home to those working in cities an hour or more away, and the homes largely stand empty during the day. Moone is becoming typical, with no local amenities, forcing the car to take over from walking, even for the school runs; and the opportunity to meet, mix and socialise are decreasing as a result. For JHR, the workplace is the hub of community.

“When the post office closed, it was a big loss,” Harrington reflects. “The postman now picks up our post when he delivers and he’s been very good. He makes sure he comes in to us first, so we receive everything earlier in the day, which is a benefit. In many places with just one postal service a day, it tends to be midday, and that must make it hard to organise an office when you’re waiting on something.”

The office is the main entrance room of the farmhouse, leading into the kitchen and hub of family life. It’s no different to any racing yard office—a little too small for the three women working away there and the volume of paperwork, calendars, diaries and newspapers they share it with in the race to stay ahead of the entries. It’s edge of the seat stuff, but only because the chairs are also occupied by the smaller of the dogs who share the space too.

There can be no better working environment, whether for Ally Couchman, office manager, Jessie’s two assistant trainers, her daughters Emma and Kate, and Richie in the office, or the 65 staff members who form part of Team Harrington, headed up by head lad Eamonn Leigh and yard manager Nigel Byrne. It’s hard to imagine where 65 employees would find work elsewhere, particularly the hands-on physical outdoor work that won’t be on offer in Dublin.

“I don’t know how vital we are to the community,” Harrington muses, a lady who prefers not to take credit where it may not be due, as she considers what her business brings to Moone.

Richie is more forthright. “There was a public meeting in Athy on the increased business rates affecting the shops and commercial premises in the area,” he recalls, “and Seamus O’Reilly stood up and stated that if it were not for Jessica Harrington Racing providing so much employment locally, none of the businesses would have the huge revenue that brings in.”

There’s more to it than revenue, of course. Horses engender a strong sense of attachment, and successful horses offer something even stronger—pride. This was never better illustrated than in March 2017, when Jessica was crowned Queen of Cheltenham. The homecoming she received caught her completely by surprise. Imagine Jubilees, Founders Days, Royal Weddings, and then add in the joy and fervour of ‘shared ownership’ as the people of Moone welcomed back their very own heroes.

Supasundae, Rock The World and Gold Cup hero Sizing John had helped to cement their trainer’s name in history as one of the most successful Irish trainers at the Cheltenham Festival and certainly the winning-most lady trainer, should we feel it’s necessary to make any distinction. Harrington’s record speaks for itself, and she’s on an equal-footing with all great trainers. Bringing home three cups from the 2017 Festival, the top prize itself among them, was suddenly Moone’s badge of honour, not just Harrington’s.

Sizing John and Jessica’s daughter, Kate.

“We had a homecoming for Sizing John, to parade him for the media and local fans, and it just took me so much by surprise,” admits Harrington. “The whole community seriously came out, everyone wanted photos taken, we were there for a good couple of hours. I remember worrying about everyone crowding behind the back of the horse, but he took it so well.

“They made me a huge banner; it stretched right across the street, ‘Moone’s Queen of Cheltenham’,” Harrington reveals with a smile. “They very kindly let me keep it, and we have it hanging up in the indoor arena. The village hall was opened up for tea and biscuits and buns and cakes for everyone. It’s amazing what it does for the community.”