Mario Baratti - how he’s created a classic winning stable in the heart of Chantilly

Mario Baratti is sitting behind the desk in the spacious office of his stable off the main avenue leading into Chantilly, munching a croissant in between second and third lots. I decline his offer of breakfast, and we quickly agree to communicate in French and to use the friendly “tu” form instead of the more formal “vous”.

Above the trainer’s right shoulder, a large watercolour depicts a scene of Royal Ascot, “it was a wedding gift and it was too big for the house so it has a perfect place here… The colours are beautiful and it’s a wonderful source of inspiration!” The walls are also adorned with photos and a framed front page of French racing daily Paris-Turf showing Baratti’s two Classic winners to date, Angers who lifted the German 2000 Guineas at Cologne in 2023 and Metropolitan who propelled his handler onto the big stage with a first Group 1 victory in the Poule d’Essai des Poulains a year later. There is plenty of space left for memorabilia which seems sure to come to celebrate wins in the future.

Born and raised in Brescia in North-West Italy near Lake Garda, Mario Baratti has a slightly different profile from several of his compatriots who are now successfully operating in Britain and France. The 35-year-old does not hail from a big racing family and he has little experience of training in his native country.

He explains, “My father was a great sportsman and was good at a lot of sports. Between age 18 and 25 he rode over jumps as an amateur. I started riding very early, at age four or five, and showjumped and evented when I was young and then started riding as an amateur as soon as I could. I was a true amateur as I didn’t start working in racing until I was 19. I was lucky to ride about 70 winners, in Italy but also in Britain and France, in a relatively short career in the saddle.”

A couple of summer stints with John Hills in Lambourn as a teenager further fuelled the young Mario’s passion for racing and he soon joined Italy’s legendary trainer, Mil Borromeo in Pisa, “Mil Borromeo was a great trainer, very sensitive and with an amazing capacity to listen to his horses. His objective was to create champions and he succeeded many times during his career. He was on the same level as the top trainers from England, Ireland and France from the time. He was very sensitive and attentive to his horses. My official title with him was assistant but I was so young I was more of an intern.”

After a year with the Classic Italian trainer, Borromeo advised the young Barrati to spread his wings and continue his education, both in racing and academically.

The Botti Academy

The logical port of call was Newmarket and the stable of training’s rising Italian star of the time, Marco Botti. “I used to ride out in the mornings and go to Cambridge in the afternoons to learn English. The original plan was to spend just a year in England to pass a language exam, but after I passed the exam, Marco Botti proposed the position of assistant if I stayed with him. When I started he had less than 50 horses and during the four years I was there the number rose to over a hundred so it was a real growth period. I had the good fortune to ride horses like Excelebration who was exceptional, and to travel to Dubai, or Santa Anita for the Breeders’ Cup... He had six or seven real high-quality Group horses, who could travel and win abroad.

I learnt many things during my time with Marco and the most important was probably how to manage the horses in the best possible way to optimize their potential. I think the secret to his international success is that he travels his horses at the right moment. He understands when a horse is tough enough to go abroad, and he doesn’t take them too early in their careers.”

After four years in the buzzing racing town of Newmarket, it was time to continue the learning curve and despite an offer to join another compatriot, Luca Cumani, Baratti remembers, “everyone advised me to go to America or Ireland.” So the young Italian found himself in rural County Kilkenny. “Jim Bolger said he would only take me if I stayed for three years, but in the end I cut my time short. It was a very good experience and I learnt a lot about breaking in yearlings and working with youngsters. I learnt what I could in a short time as I was only there for three or four months, an intense experience of work and life. Mr Bolger is a real horseman, who is tough on his horses but always manages to produce champions. He can do things that others cannot allow themselves to do, because he breeds and owns a lot of the horses himself.”

Despite the prestige of his Classic-winning mentor, Baratti was unable to settle in Ireland. “I like the countryside, but I was isolated. I was 25 years old and never saw or spoke to anyone and the lifestyle wasn’t for me. So one day I told him, “I can’t stay three years”, and he said, “you want to train in London? You can’t train in London!” I’ll never forget that! But he understood and in the end he said, “I’ve taught a lot of top professionals, McCoy, O’Brien, but it’s up to you if you want to leave. I hope that you find someone as good as me…””

Pascal Bary an inspiring mentor

Next stop was France, and Baratti took advantage of a couple of months before his start date with his next boss, Pascal Bary, to join fellow Italian Simone Brogi who had recently set out training in Pau. He also spent a month with Brogi’s former boss, Jean-Claude Rouget, at Deauville’s all-important August meeting.

“The time helped me to learn French and integrate into the French ambiance, which wasn’t easy. I found it much tougher to settle in France than in Newmarket. As a foreigner I felt less well received. Even at Newmarket, I started as an assistant when I was 18 years old, with no experience, and it was tricky to manage a team of 25 or 30 staff. But when I started here it was even more difficult to handle the French staff. They would say to me ‘I’ve never done that in 30 years and I’m not going to start now…’ During the early days with Pascal Bary, I thought that France wasn’t going to be for me. Then it became a personal challenge and I decided to stick it out. Now, Pascal Bary is one of the closest friends I have here in Chantilly, but at the start he wasn’t an easy boss. It took two years, of the four that I was there, before we built up a real relationship. On my side, I was very respectful, and I saw him as someone who was very reserved, so we kept our distance. I was in awe of him and his career. He wasn’t interested in just winning races, he wanted to develop the best out of his horses. That’s why he had such a great career. 41 Group 1 wins in a 40-year career is a huge achievement. He won Dianes, Jockey-Clubs, Poules, Guineas, Breeders Cups, the Irish Derby… He’s the only French trainer to win the Dubai World Cup. He started off going to California for the Breeders’ Cup when he was very young. He would dare to step into the unknown, because at the time it was much more complicated to travel around the world.

I was lucky to be there at the time of Senga - who won the Prix de Diane and Study of Man won the Prix du Jockey-Club. So I worked with top horses, who were perfectly managed, and many of them were for owner-breeders. Very early in the season, when the grass gallops opened, he would immediately pick out the three or four standout horses and plan their programme. He could tell right away which ones had talent ‘this one will debut in the Prix des Marettes at Deauville… ‘ I remember that year the filly did exactly that and won; it was Senga and she went on to win the Diane.

When you spend time with someone at the end of their career, there is more to learn. Pascal Bary had a superb training method, and he had the success he did because he was very firm in his decisions. He’s not someone who changes his mind every day, and there aren’t many people like that nowadays. He was very sensitive to his horses and always sought to create champions. I try to keep in mind his method.”

Changing dimension

The string for third lot is now ready to pull out and we make our way through the yard which has been adapted to accommodate an expanding string.

“We recently acquired the next-door yard and we knocked through the walls of a stable to make a passageway between the two. I now have 73 boxes in these two yards, plus 15 at another site which has the benefit of turnout paddocks.”

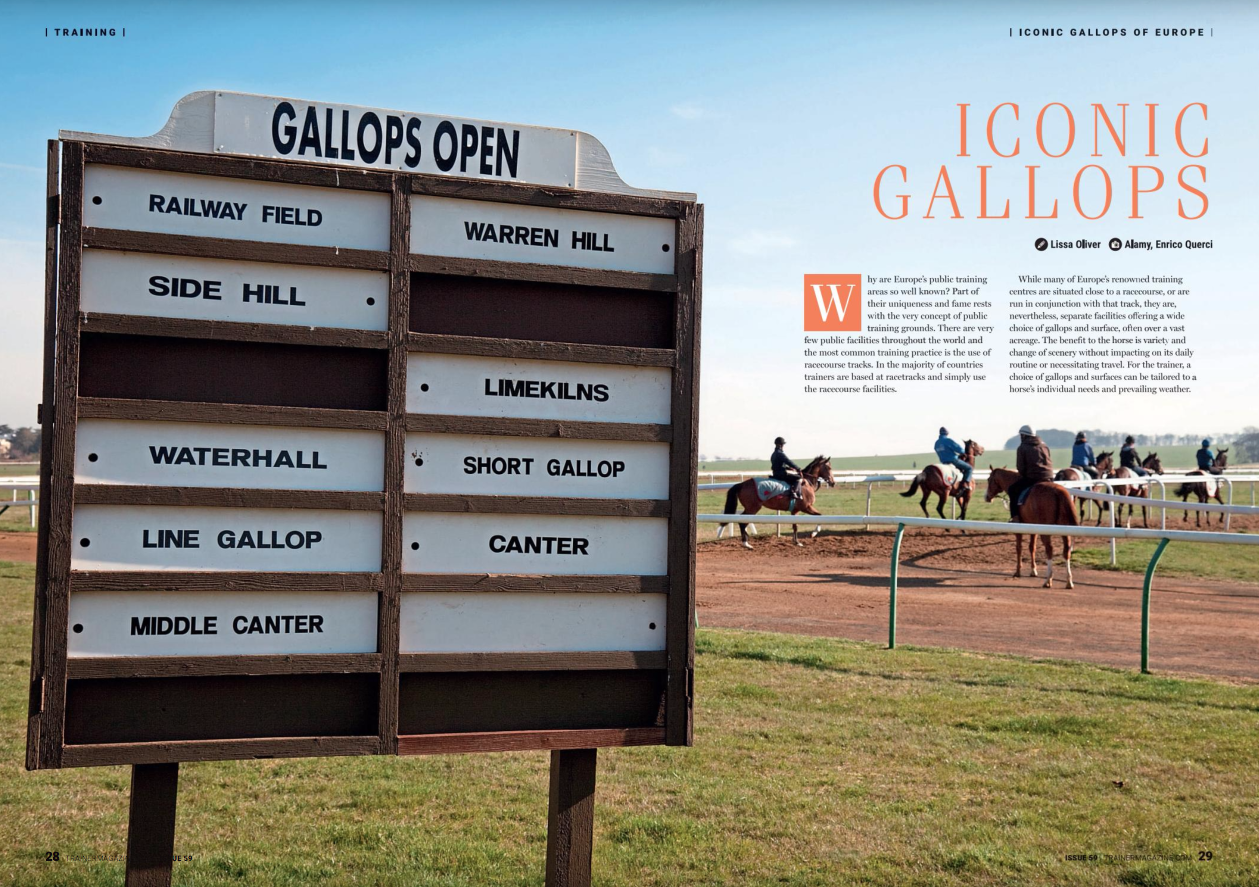

Through a gate in the hedge at the back of the courtyard and we are straight onto the famed Aigles gallops as the sun starts to break through the clouds on what had begun as an overcast morning.

“It’s a magnificent site; we are so lucky to have such beautiful surroundings and for me to be able to access the gallops on foot.” As we make our way to the walking ring in the trees where the Baratti string circles before and after work each morning, the trainer tells me, “I still ride out every Sunday, bar only two or three weeks in the year. I think it’s important to exercise as many as we can on a Sunday and if I ride two, that’s a help to the staff and a real pleasure for me too.”

The string of around twenty juveniles, many still unraced, passes before the trainer who gives multilingual orders. “Here we speak Italian, French, English, Arabic and Czech,” he explains, “we try to all speak French but of course sometimes we communicate in Italian, especially when things get heated! We’ve more than doubled in size since last autumn and so we built up the new team throughout the winter and in spring. It’s all coming together now. For the first few years everything went very smoothly, but there were only half a dozen members on the team! When you get up to 25, it’s a different story.”

The team includes a couple of former Italian trainers who left their country and now work as managers for the burgeoning Baratti stable, plus veteran Filippo Grasso Caprioli, Mario’s uncle who was a leading amateur rider in Italy in his time. “He “just” rides out, he doesn’t have a position of responsibility but he does give us the benefit of his age and experience!”

Another vital member of the team is Monika, Mario’s Czech-born wife. “We first met at the Breeders’ Cup when I travelled with Planteur and she was the work rider of Romantica for André Fabre. When I first moved to France we both lived in the same village, 100m away from each other but we never bumped into each other. We met again four years after I moved to France. We’ve been together now for seven years and married this spring. Monika is an excellent rider and she also takes care of the accounts, but her most difficult job is taking care of our two small boys. I think she sometimes comes into the yard for a break!”

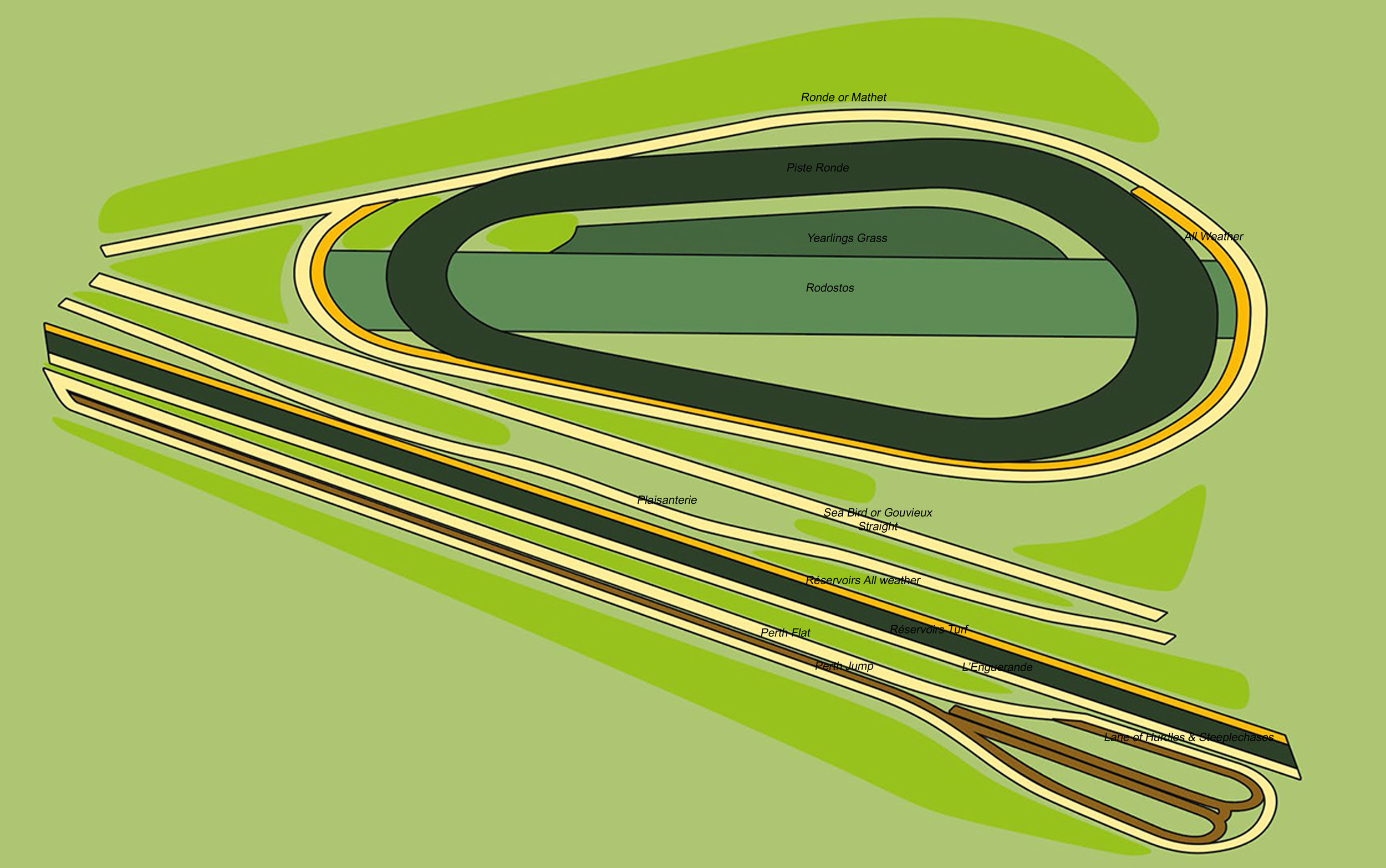

As we trudge across the damp turf to the Réservoirs training track, Baratti expands on his choice of Chantilly. “When I was in Newmarket I thought I would never leave, but then it was logical to continue here after I had done my time with Pascal Bary. And of course, the French system is very beneficial compared to elsewhere in Europe. The facilities here in Chantilly are second to none. When I first started I used to use all of the gallops but now I have my routine and regularly use Les Réservoirs. I often use the woodchip but there is plenty of choice. Once you have understood how each track works then it’s simple.”

The first group of two-year-olds canter past, and Mario runs through some of the sires represented: Siyouni, Lope de Vega, Wootton Bassett, for owners such as Nurlan Bizakov, Al Shir’aa, Al Shaqab and powerful French operators such as Laurent Dassault, Bernard Weill and others.

“This is the first year that I’ve had such a good panel of owners, and a better quality of horses. It is certainly thanks to Metropolitan and the successful season we had last year. In previous years, we did well with limited material, and we managed to win Listed or Group 3 races which isn’t easy when you only have 20 horses. This year we have more horses but haven’t won any big races yet (he laughs nervously) but they will come…”

Indeed days after the interview, the stable enjoyed a prestigious Group success on Prix du Jockey-Club day with the Gérard Augustin-Normand homebred Monteille, a sprinting filly who was trained last year by the now-retired Pascal Bary.

“It's very important to have owners who also have a breeding operation. They have a different outlook on racing and they are often the ones that produce the really top horses. They expect good results, of course, but they understand the disappointments and are generally more patient. The other owners are important too, and Metropolitan, who we bought at the sales, is the proof of that.”

Classic memories

Understandably, a smile widens across Mario’s face as he remembers the day when the son of Zarak lifted the Poule d’Essai des Poulains to offer the trainer his first major Classic winner.

“I was only in my fourth year of training, it wasn’t even in my dreams to win a Poule so soon in my career. It’s hard to describe, the joy was enormous. The fact that we ran in the race again this year, with a very good horse (Misunderstood) but everything went wrong, makes you realise now how difficult it is for everything to go right on a day like that. I always thought that Metropolitan was an exceptional horse. We were far from favourites in the Poule but I knew we had a good chance of winning. The owners rang me on the morning of the race and asked, ‘Mario do you think we can win?’ and I said Yes! He had finished fifth in the Prix de Fontainebleau and we had ridden him to avoid a hard race, but still, many observers overlooked him. Apart from in his last race on Champions Day, he never put a foot wrong. He confirmed his class when third in the St James’s Palace Stakes in a top-class field and then was beaten by the best four-year-old miler in Europe, Charyn, in the Jacques le Marois. And at the time, we only had three or four three-year-olds in the yard, so the percentage was amazing.”

Baratti had already tasted Classic glory a year earlier, thanks to Angers (Seabhac) who won the Group 2 Mehl-Mülhens-Rennen (German 2000 Guineas). A first successful international raid from the handler who learnt from some of the industry’s specialists.

“You travel if your horse is very, very good, or not quite good enough,” he explains.“If you travel to Royal Ascot, you have to be exceptional, the same for the Breeders’ Cup. But for Germany you can take a decent horse who isn’t quite good enough for the equivalent races here. Angers had finished second in the Prix Machado which is a trial for the Poule d’Essai. I already had Germany in mind for him if he was placed in the Machado, and he went on to win well in Cologne. Every victory is very important, the key is to aim for the right race within the horses’ capabilities. Each horse has his own “classic” to win, with a made-to-measure programme.”

Many expatriate Italian trainers target Group entries in their native country, but Baratti is not keen to explore this option. “I have never had a runner in Italy. I did make an entry recently but we ended up going elsewhere. Italian black-type is very weak for breeding purposes, so it’s not really worthwhile for me to race there. There are a lot of good professionals in Italy but I don’t really have much connection with them because I’ve never worked over there, I left when I was young.”

A realistic approach

Baratti’s adopted homeland of France has recently announced austerity measures for the forthcoming seasons to compensate for falling PMU turnover and pending the results of a recovery plan which aims to increase the attractivity of French racing for owners and public. France Galop prize money will be reduced by 6.9%, equating to 10.5 million euros during the second half of 2025 and 20.3 million euros for following seasons until a hoped-for return to balance in 2029.

“It’s normal,” says the Italian pragmatically. “It’s better that they make a small reduction now than wait two or three years and have to make drastic cuts. It’s necessary to take the bull by the horns, not like how it was in Italy when they let the situation decline and then it became too hard and too late to redress. We are fortunate to be in a country where prize money is very good compared with our neighbour countries in Europe, so a small reduction won’t affect people too much.

Owning racehorses is a privilege and a passion. It is a luxury and people should treat it as such, not buy horses as a means to earn money. If you buy a magnificent yacht, it costs a fortune, and it’s pure outlay. Money spent on having fun. Nowadays, a lot of people invest in racehorses for business purposes, but they need to have the necessary means. If you are lucky to buy a horse like Metropolitan and then sell him for a lot of money, that’s another story, but it wasn’t the aim at the outset.”

He remembers an important lesson on owner expectations from former mentor Pascal Bary. “I was surprised once when Mr Bary received some foreign owners in his office. They wanted to buy ten horses. He told them, the trainer earns money, not every day, but he tries, in any case his objective is to earn money, the staff earn money and the jockey earns money. Normally, the owner loses money. If things go well, they don’t lose much, if they go very well they can break even, and when it’s a dream, then you can make money, but that’s the exception to the rule. The guys had quite a lot of money to invest and they were there, open-mouthed. In the end they chose another trainer. But Mr Bary was right. If I decide to buy a horse tomorrow for 5,000€, I have to consider that 5,000€ as lost. If I want to invest, I should buy a house.

His explanation was very clear and that’s how racing should be understood. It would be nice to have a group of friends buy a horse, but it costs a lot. Ideally it should just be for pleasure, like membership at the golf, or tennis. It's an expenditure. And if in the end you end up winning, then all the better. And it can happen. Bloodstock agents do that for a living but it’s their profession. My owners are in racing for the pleasure.”

With an upwardly-mobile, internationally-minded and ambitious young trainer, Baratti’s owners certainly look set for a pleasurable ride over the forthcoming seasons, and the office walls are unlikely to remain white for long.

The Botti family dynasty

When passion and high commitment meet family unity, the potential to build an empire emerges. For generations, the Botti family has been a pillar in the world of Italian horse racing, where a passion for horses is passed down through a deeply rooted family heritage. The blood ties among family members have not only strengthened their personal unity but have also solidified their commitment to the Italian racing world. Two brothers, born and raised in the stables of San Siro, have become mentors to their children, instilling in them the same unconditional love for horses and competition. The story of the Botti family is not just a tale of success and trophies; it is also a profound expression of family dedication and shared passion that continues through the generations.

The racing traditions of the Botti family can be traced back to around 1860, deeply embedded in their maternal lineage with the first English settlers in Pisa, heralding a longstanding equine legacy.

Edmondo Botti, the patriarch, first made a name for himself as a steeplechase jockey before transitioning into a revered trainer. His sons, Alduino and Giuseppe Botti, inherited this fervent passion for horse racing. Giuseppe initially pursued a career as a steeplechase jockey, while Alduino excelled as a flat race jockey, quickly making a mark by winning Group 1 races.

Tragedy struck when their father, Edmondo, died in a road accident while returning from the races in Livorno. This pivotal moment deeply affected both brothers, who, encouraged by the owners of the stables their father had trained at, decided to step into their father’s shoes as trainers. This decision marked the beginning of a new era for the Botti family, as they combined their inherited skills and passion to build on the legacy left by their father.

In 1971, the Botti brothers started their training career in the San Siro training centre. From the outset of their careers as trainers, they quickly achieved notable success; by 1973, they had won their first Italian trainers' championship. From that point onwards, they have been a dominant force in the Italian horse racing scene, missing the top spot in only two out of forty-nine championships.

All the horses under their care were and in part still are trained at the Trenno tracks, part of the San Siro training centre, where they employ a personalised approach tailored to the needs of each horse. This customised training methodology ensured that each horse could achieve its full potential.

Reflecting on the dedication required for such success, Alduino Botti shared, "I must be honest, we always gave it our all. We knew neither holidays or festivals and always strived to work hard and learn new things." He further illustrated his commitment to excellence through a personal anecdote involving Sirlad, a horse that won multiple Group races, "Back when [Trainer] Benetti was working with Sirlad at the stables in San Siro, I made it a point to attend all the training sessions to understand how he managed the horse, so that I could understand what type of training required a horse like that”.

The Botti brothers' methodology was also significantly influenced by their international experiences. They regularly attended and purchased at the sales in the UK, Ireland, and Kentucky, which allowed them in the mornings to observe and learn from foreign training methods, "We woke up early and watched how other stables operated, observing their work routines and how long the horses were trained outdoors." This exposure was crucial. Although Italian tracks were not conducive to the type of training prevalent in England, the exposure and inspiration from abroad had a significant impact on their method. In fact, the iconic Warren Hill track at Newmarket has inspired the design of their new track in their training centre in Cenaia, in Tuscany.

The improvement in results and the champions they have trained, such as Ramonti, Miss Gris, Val d'Erica, Maria Welaska, My Top, and Crackerjack King, not only reaffirmed the Botti brothers' prowess in horse training but also paved the way for them to venture into breeding. "Breeding has always been my passion," Alduino remarks. The decision to start breeding was a natural progression, using mares that they had previously trained. "Having trained them, you know exactly their strengths and weaknesses, which helps in choosing the right crosses," Alduino explains.

The expansion into breeding initially led the Botti brothers to acquire an ex-breeding farm in Cenaia. Originally dedicated to raising their mares and foals, Giuseppe, after a thorough study of the ground and geographical location, had the insight to build an uphill training track there. The facility was first transformed into a pre-training centre. Later, Stefano, Alduino's son, decided to establish his training operations there, and it has since become one of the premier private training centres in Italy. As for the breeding operations, the brothers later purchased another site which continues to serve as their breeding farm, known as "Razza del Velino."

This strategic expansion reflects the Botti family's deep commitment to excellence in both training and breeding, positioning them as key figures in the Italian and international racing scenes.

The Botti family’s passion for horse racing spans generations, with each member continuing to honour and expand upon their rich heritage. Alduino's sons, Marco and Stefano, and Giuseppe's sons, Alessandro and Edmondo, have all embraced their forebears' calling in the world of horse racing.

MARCO

Marco began his career as an apprentice but had to step away due to weight restrictions. He then joined his father at their stable in Milan as an assistant. Seeking to expand his horizons, Marco moved to Newmarket, to work under trainers Luca Cumani and Ed Dunlop, and was also part of the prestigious Godolphin team. These experiences deeply influenced his training style, leading Marco and his wife Lucie to establish their own training facility, "Prestige Place," in the UK. Adapting to British racing conditions was essential, and Marco's time in Newmarket was crucial. Despite the physical distance from Italy, Marco maintains strong ties with his family. He underscores the strength of these bonds, stating, "Distance has strengthened our union. I often attend sales to purchase horses for my brother Stefano. We frequently exchange advice and, with the owners' consent, decide whether a horse is better suited to race in England or Italy."

This strategic collaboration recently led to the success of Folgaria, an unbeaten Italian mare brought to the UK by Marco, who continued her victorious streak by winning the Gp.3 (Fred Darling) Dubai Duty Free Stakes. The enduring bond between Marco and Stefano not only highlights their personal connection but also enhances their professional successes, underlining the strength of family ties in achieving shared goals.

STEFANO

"Ever since I was a child, I have followed every step of my father; horses have always been part of my daily life," Stefano Botti reminisces. By the age of 16, he had obtained his amateur jockey licence and began dominating the field, winning the championship for 15 consecutive years from his second year. His deep involvement in studying races, programs and following training sessions not only fueled his passion but also equipped him for a successful transition to training. During winters, Stefano would relocate to Tuscany to join his father and uncle's stable until he finally settled permanently in Cenaia. Initially, Cenaia served as a pre-training centre where Stefano trained the foals that were later prepared at San Siro.

Over time, the centre expanded significantly, adding two uphill training tracks, one 800-metre woodchip and a 1000-metre all-weather track. This development significantly altered the family’s training approach. "It used to seem that without Milan or Rome, training a horse was difficult, especially without grass tracks. But since moving here, things have turned around. I've trained top horses like Ramonti, achieving third in a Group 1 race in Hong Kong," Stefano explains. The uphill tracks are particularly beneficial for preparing young horses by reducing strain on their forelimbs and enhancing their hindquarters, which Stefano notes makes them nearly always ready at debut. Today, Cenaia is home to about 125 horses, with plans to expand. This innovative approach has led to numerous successes, including wins abroad, such as the Derby in Qatar.

Stefano's relationship with his father remains a cornerstone of his career, "My father is my role model, many of my successes are due to his teachings," reflecting the ongoing collaboration between the San Siro and Cenaia stables towards a unified strategy.

ALESSANDRO

Alessandro Botti embraced his equestrian calling from an early age. Although his initial stint as a jockey was short-lived due to weight constraints, he didn't stray far from the racetrack, choosing instead to work alongside his father and uncle in the family stables. Driven by a spirit of adventure and a desire for new challenges, Alessandro made the bold decision to relocate and establish his training career in France. "It wasn't easy because I lacked nothing at home, but I've always thrived on competition, and this desire pushed me to explore new horizons," he explains.

Today, Alessandro runs a stable in Chantilly, managing approximately 70 horses with the help of his wife. Together, they have celebrated numerous triumphs, accumulating around 500 wins. Alessandro’s future seems firmly rooted in France, a country where he has found both success and satisfaction.

Edmondo

Edmondo has been passionate about horse racing from a young age, famously stating, "I grew up on bread and horses." He began his career as a flat race jockey in 1989 and quickly made his mark by winning his first championship in 1992. After a brief retirement in 2000, his love for the sport reignited, leading to a triumphant return in 2003 where he claimed victories at both the Italian Derby and the Parioli, and rode notable horses like Electrocutionist and Ramonti.

In 2008, Edmondo transitioned to training, partnering with his wife Cristiana Brivio to manage their stable in San Rossore. Together, they've enjoyed significant success, training approximately 130 horses and consistently winning important races both in Italy and internationally. Committed to their enchanting training grounds, Edmondo continues to cherish the Italian racing life, saying, "We train in a magical place, and it would be a shame to give it all up."

THE BOTTI BROTHERS TODAY

Today, the Botti brothers continue to make significant contributions to the world of horse racing, each in their own unique way. Alduino remains actively involved in training at San Siro, working closely with his son Stefano to maintain and enhance their training operations.

Together, they form a dynamic team, perpetuating the Botti family's legacy of excellence in horse racing. Meanwhile, Giuseppe has transitioned his focus towards a more social and political role within the industry.

Faced with the challenges currently besetting Italian horse racing, Giuseppe has voiced his commitment to revitalising the sport that has given him so much. "I want to contribute by giving a new face to Italian horse racing, which has given me everything. Now it's my turn to give back," he declares.

Having lived through and witnessed the transformation of Italian horse racing across various generations as trainers, breeders, and owners, both brothers are acutely aware of the sport’s current crisis. "It pains me to see the state of racing today, remembering a time when there was much more passion" Alduino reflects. The decline in public interest has led to decreased national investment, resulting in the closure of many racetracks and a troubling downturn in breeding. "We decided to increase our breeding activities, reaching a high number of broodmares, but the industry’s decline is forcing us to cut back" Alduino adds, highlighting a severe issue that could impact Italy's future international prominence in racing.

Giuseppe, despite recognising the dire situation, feels a duty to contribute to a revival of the sport that can inject new vitality. "We must not surrender to this situation; we need to stay current as trends change, but we must also draw people back to the races," he asserts. Emphasising the importance of shifting the narrative from betting to promoting the sport and the passion surrounding horse racing, Giuseppe suggests, "Race tracks should become city theatres, places of community gathering for individuals and families."

Faced with the challenges currently besetting Italian horse racing, Giuseppe has voiced his commitment to revitalising the sport that has given him so much. "I want to contribute by giving a new face to Italian horse racing, which has given me everything. Now it's my turn to give back," he declares. To this end, he serves as vice president of the "Final Furlong" association, which aims to promote horse racing on a national scale. This organisation focuses on more socially conscious initiatives, such as the rehabilitation of retired racehorses for integration into Italian equestrian tourism and engaging schools to introduce young people to the marvels of horse racing. Moreover, Giuseppe stresses the need to "engage young people by introducing school opportunities that can lead them to appreciate horse racing and, perhaps, make it a part of their future."

Another concerning issue for the brothers is the decreased Italian participation on the international horse racing scene. Both recognise the necessity to reassert Italy and especially its races as a point of interest for other countries. "Competing with others strengthens us; it not only helps our ratings but also allows us to gauge the level of our horse racing and how we can improve" says Giuseppe.

Both brothers hope for a turnaround and improvement in the industry, emphasising the need for strong commitment from everyone involved, breeders, trainers, and owners, to achieve this goal.

This narrative captures the essence of a family whose life and soul are entwined with the sport of horse racing, making it their life's work and passion. The Botti family has not only excelled in the field but has also passed down a love for the sport through generations. The future looks promising as the passion for horse racing seems to be a lasting trait in the family.

Marco, Stefano, Edmondo, and Alessandro's children also exhibit a keen interest in continuing the family tradition. Thus, the legacy of the Botti family is far from reaching its final chapter, with more stories yet to unfold in the racing world.

Noel George and Amanda Zetterholm - The anglo-swedish duo taking French racing by storm

Article by Katherine Ford

Training partnerships are now firmly established in racing. Father and son (or daughter), husband and wife, or experienced trainer and long-standing assistant; these entities are now regularly seen in Europe and beyond. The association of George & Zetterholm Racing, one of the newest names in the French jumps trainers’ column, doesn’t fit in any of the usual categories but has already proven its efficiency in less than a year of operation.

Twenty-four-year-old Noel George, who found his way to France during Covid, is a former amateur rider and the son of Gr. 1 winning British trainer Tom George; whereas dynamic Swedish-born Amanda Zetterholm boasts a wealth of experience in a variety of capacities in racing and bloodstock around the world. The pair have no background together, and a chance remark has seen them launch as one of France’s most exciting training operations.

“We knew each other, but that was all; and it was (fellow Chantilly trainer) Tim Donworth who suggested we set up together,” explains Amanda. “Noel wanted to train in France, but of course it is complicated to set up here, so it was a good opportunity to do it in partnership. I told Noel I’d found this yard I love, so we went to visit it together, and he said he’d love to train here. I bought the yard exactly a year ago, in September 2022”.

Creating a masterpiece

Amanda and Noel each bring their own talents to the partnership, “I’m the Louvre, and he’s Thomas Gainsborough”! Amanda’s marketing background shines through with her metaphor illustrating that she provides the solid base for Noel to fulfil his role as “the artist” with the horses.

Growing up in Sweden, Amanda Zetterholm enjoyed riding and show jumping but didn’t have any involvement in racing until studies took her to Australia, where she spent time with David Hayes and Matthew Ellerton. “My first job in racing was with agent Damon Gabbedy, who taught me a lot about the breeding side. Then I went to South Africa and spent three years with Mike de Kock, which was a great experience—between Dubai, England and South Africa. He is very avant-garde”.

In 2013, Amanda was recruited by the Aga Khan Studs as commercial executive and has fulfilled a variety of roles for the famous operation. She currently balances the burgeoning training career with work for the Aga Khan Studs but is soon set to devote herself fully to George & Zetterholm Racing. “I’ve spent 10 wonderful years with the Aga Khan Studs, but I will finish at the end of the year; I can’t do both. They’re very proud of what I’ve achieved”.

Add to these achievements a successful amateur riding career on the flat, a stint as Goffs French representative and an instrumental part in the setting up of the stable of former partner David Cottin, with whom she has two young sons, Winston and Clovis, plus success in buying young jumping stock to sell on, which has set her up financially to be able to buy the Chantilly yard; it is clear that Amanda is not shy of a challenge or a busy schedule.

Well-defined roles

“We passed the trainers’ licence together, and the idea was always that Noel wanted to do his training regime. He’s on the track every morning with the horses. I’m out here maybe three times a week currently, but that will change once I finish with the Aga Khan Studs. We both discuss and do the entries. We’re on the same wavelength, and I would say I am a very easy partner. I have a lot of experience, and I don’t feel I have anything to prove.

“In France, there is so much paperwork. I deal with the business side, the staff and the logistics; and I do the communication with the owners, which I love. I don’t feel the stress that Noel feels with the owners as he is the one who has directly prepared the horse, so I can be more relaxed. I am there to reassure them and make sure that they have a good day out. We are very complementary. Noel is a very confident person. You need to be confident to be a good trainer because the horses feel the confidence, and the owners too. He passes that confidence on to everyone”.

Living the dream in France

Noel George displays a confidence which belies his years, and in France he has found an opportunity to fulfil a dream that he had not imagined possible. “Since I left school, I aimed to train flat horses because I didn’t see economically and business-wise how it could work training jumpers in the UK”. After a year with Graham Motion in the USA and summer holidays with Sir Mark Prescott and Joseph O’Brien, Noel George has learnt from some of the best on the flat.

The French connection came about by coincidence, although there is family history across in Chantilly as father Tom George spent time with the pioneering François Doumen in the days of The Fellow, whetting his appetite for cross-Channel raids. “I remember when Dad always used to come over with runners and then Halley won the Gp. 1 Maurice Gillois. I wasn’t there that day but I remember it—Dad built his new kitchen because of it! That stuck in my mind, that the French prize money is amazing… I was meant to be going to Australia as an assistant, but then Covid happened and French racing started before anywhere else; so I moved over to work for Fabrice Chappet”.

Noel didn’t speak French when he arrived but learnt quickly—thanks to language apps, Chappet’s former assistant, and now young trainer Xavier Blanchet, as well as being motivated to communicate when chasing a few French girls!

During the period with Classic-winning Chappet, Noel oversaw a string of horses running under a provisional licence for his father Tom. “I was giving orders to Dad’s horses on the same gallops, and it was a help that I knew the farrier, the feed suppliers etc”.

Provisional training operations in France are restricted to three months, but the experience served to reiterate the financial sense of racing in France but also the accompanying bureaucracy.

“I eventually passed the trainers exams, which aren’t easy! It’s not just knowing the language, it’s knowing all the anatomy of the horse, in French, the employment laws, how to write a payslip—all the different taxes… For that, having Amanda is a huge asset because I can focus on training the horses and she does all that complicated stuff”.

Noel is also full of praise for his father Tom. “He’s a great source of advice for me; I ring him whenever I have a question. We couldn’t do it without him. He’s put his neck on the chopping block by pushing a lot of the horses over here, and it seems to be paying off”.

Top-class training grounds

Another huge advantage for George & Zetterholm Racing is their stable and accompanying facilities. The yard, on the outskirts of the village of Avilly-St-Léonard, has already sent out three winners of France’s feature Grand Steeple-Chase de Paris as former owner Christophe Aubert was responsible for Line Marine (2003) and Mid Dancer (2011 & 2012).

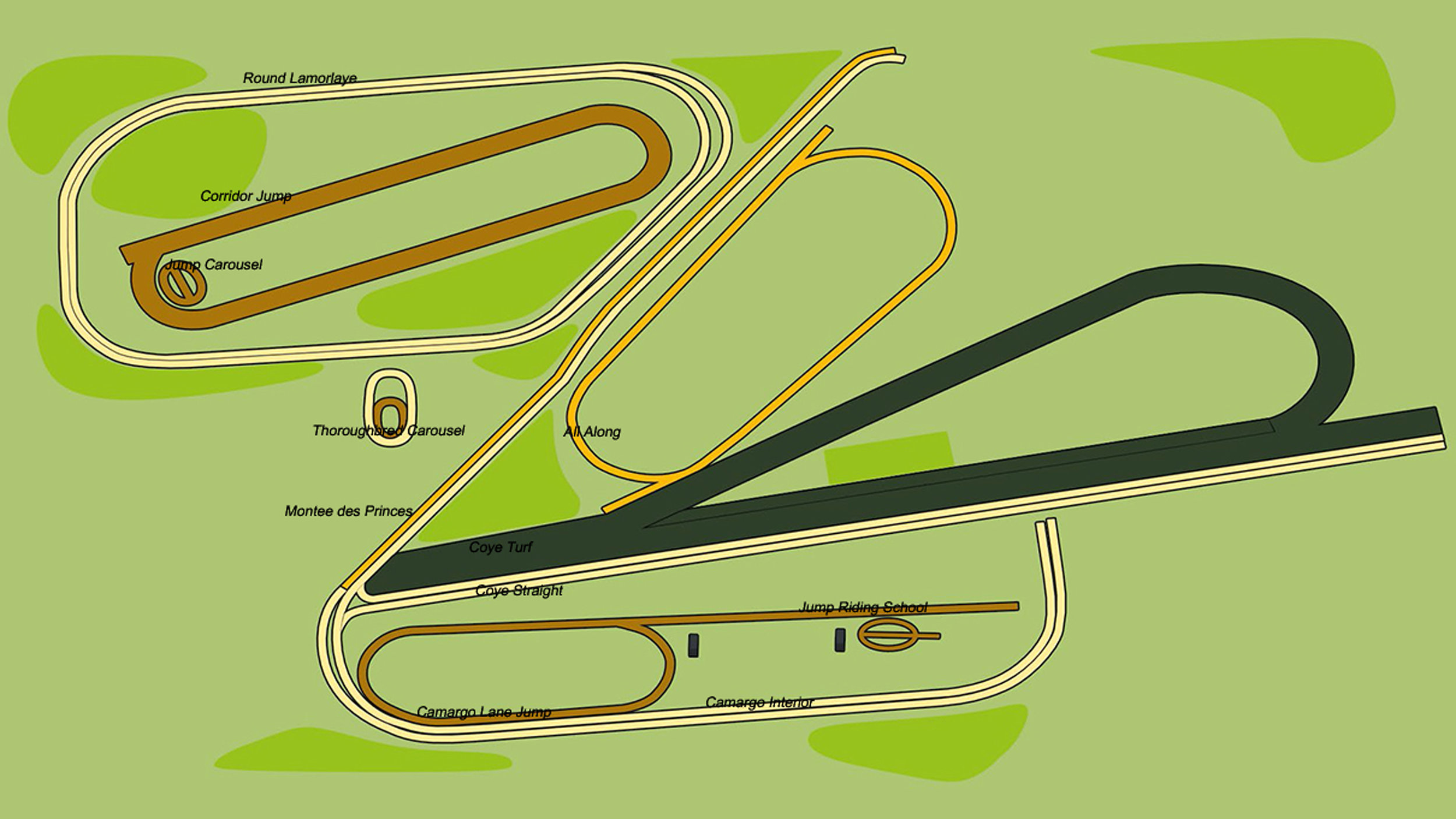

This is part of France Galop’s huge Chantilly training domain, but being slightly out on a peaceful limb compared with the more famous locations of Chantilly, Gouvieux, Lamorlaye and Coye-la-Forêt, it has all the benefits of a private establishment. “We can’t praise France Galop enough for all they do for us,” says Amanda. “When the English owners come over, they just can’t believe it, and even Noel’s dad has his own amazing facilities; but he has to run it all himself. This area of Avilly has been almost dormant for several years and so the France Galop teams are very keen to revive it and make improvements”.

In concrete terms, this means that Noel and Amanda, having the only active stable in the vicinity, have exclusive use of extensive schooling facilities and gallops. “We’ve got cross-country, steeplechase fences and hurdles. They are a little bit smaller than the racecourse ones, but I don’t think you have to jump big in the mornings. It’s better if they’re a bit smaller as they give the horses confidence. We tell the France Galop staff the days when we will be schooling and they make sure everything is prepared”.

Noel adds, “The training centre is incredible, and we are so well looked after by France Galop who really want to help us. They give the horses the best chance possible. We have a 2000m sand gallop through the forest, which we use daily; then there’s a big 2000m sand circle which isn’t watered but in the winter it’s very good for the youngsters—it’s like a racecourse! We have to go to Chantilly to use the grass, but I think it does the horses good to go on the lorry”.

Schooling is an integral part of training jumpers in France; and Noel admits, “I’ve watched videos of how Macaire and Nicolle do all the French schooling and we’ve mixed it with the English way; and it seems to be working”.

The French policy of regular schooling has been adopted, and here again, the French system offers benefits. “The likes of James Reveley, Felix de Giles, Nicolas Gauffenic, and Kevin Nabet will be in nearly every Wednesday. It’s not like in England where the jockeys might be riding up north or down south and are less available for schooling. The horses, especially the older ones over from England, love it. It gives them a change, especially with the different steeplechase obstacles like the bullfinch the bank, the white wall… And as we don’t have the hills they have in England, it is good for fitness”.

“The horses jump more in races here. In a two-mile hurdle in England, they jump eight small hurdles; whereas round Auteuil over two miles, they jump 12 mini-English fences. If you lose two lengths at a hurdle here, it makes such a big difference as the next hurdle comes much quicker than in England. Jumping is very important”.

Making financial sense

Jumping is important, but prize money is even moreso; and in less than a year of operation, the stable has already earnt plenty. “We’ve had 100 runners for 800,000€ in prize money, so that’s 8000€ per runner which is a great statistic. French racing is very lucrative,” says Amanda, while Noel emphasises the point further: “The very fact that a horse can be in training and not cost money is a huge benefit. The number of horses that pay for their training fees in England is very few; whereas if your horse isn’t paying your training fees here, you probably need to think about moving it on. It’s an incredible way to be and a massive advert for French racing. It just takes the pressure off everything”.

Capacity is maybe the only source of pressure currently for George & Zetterholm Racing. The yard has 25 boxes and 14 turn-out paddocks, with a further 15 boxes rented nearby and a barn with 16 more stables under construction at the yard. “We are limited in space, and we want to focus on quality rather than quantity,” says Amanda; although Noel’s ambitions have no limits.

“The dream eventually would be to compete with the top trainers in the championship, but we want to race on both sides of the channel. I’m English. I’ve grown up in England, and we’ve got English owners; so our dream is to win big races in England too. I can’t see why we can’t do that training here. We have amazing grass gallops; we can do racecourse gallops at tracks like Compiègne, so we can get them as ready as anyone in England. Cheltenham is quicker to access for us on the lorry than it is for Gordon Elliot and Willie Mullins; and Kempton is closer to us than Pau”!

Again, the support from Tom George will be key, as horses will spend a few days at his Down Farm in Slad near Cheltenham to acclimatise and school over British obstacles.

“I can understand why Britain is not a priority for many French trainers, as there is so much money to be won here; but we have owners that are buying horses to win on big days and they want to win at the big meetings. When we do get on the boat, hopefully we will bring a few winners back for France, with English owners and English and Swedish trainers”!

A new mission for Criquette Head

Article by Katherine Ford

Five years after retiring as a trainer, the handler most famous for the Arc double of Trêve wintered in the Bahamas where she devoted herself to caring for her mother Ghislaine during her final months. A figure in French and international racing and bloodstock alongside her late husband Alec, Ghislaine Head was influential in the running of the Haras du Quesnay. Her colours were carried notably by Arc heroine Three Troikas and homebred Prix du Jockey-Club winner Bering; and she passed away peacefully at age 95 in early June.

Horses were far away in the flesh during this time in the Bahamas but still close to Criquette’s heart and very present in her mind. “When would be a convenient time for a chat?” I texted Criquette Head to arrange this interview. The reply pings back, “You can call me at 11.30am French time; I get up at 5am (EST) here every day for my first lot.”

So it is 5.30am in the Bahamas, and Criquette is in fine form as ever with plenty of ideas to discuss. “I’m always wide awake at this time. I can’t get it out of my system. Of course there are no horses here, just water and boats.” When Criquette retired, she announced a plan to sail across the Atlantic in her yacht, named Trêve. However, in typical altruistic style of the former president of the European Trainers Federation, the adventure has been on hold. “My boat is here, but I haven’t done the crossing yet. I will do it one day, but for the moment, my priority is taking care of my mother. I will stay at her side as long as she needs me.”

While she had no physical contact with horses in the Bahamas, and no imminent trans-Altantic sail to prepare for, Criquette has been devoting time and energy recently to the association CIFCH (Conseil Indépendant pour la Filière des Courses Hippiques, or Independent Council for the Racing Industry), which she created with long-time friend and associate Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle some three years ago and now presides.

Senator Anne-Catherine Loisier & Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle.

“The idea came about because I found that our politicians didn’t understand the racing world. I said to myself that as I have some spare time, I would create a little association, and I would try to ask our politicians, those who vote for our laws in the National Assembly or the Senate, to understand what racing means. We are completely separate from any official organisation, and we don’t interfere with France Galop or Le Trot (French harness racing authority). I just want to show the decision makers what racing is all about. I have met a lot of people and invited them to the races. That’s all… I try to make them realise the importance of the racing industry, and the reactions have been very positive.”

An eclectic membership

The CIFCH counts 140 parliamentarians among its membership and supporters, which is a varied panel composed of racing and non-racing people, from a wide professional spectrum.

As Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle explains, “Our aim is to share ideas and knowledge, and everyone contributes what they can, depending upon their area of expertise.” Criquette adds, “We wanted to surround ourselves with competent people who are all volunteers. They all like horses, not necessarily racehorses but the horse in general, and the association works in favour of the entire equine sector. The VAT issue is an important one for the CIFCH. If we manage to reduce the rate for equine activity to 10%, the entire horse industry will reap the benefit.”

A key supporter is Senator Anne-Catherine Loisier, vice-president of the CIFCH and who notably assisted in opening the doors of the National Assembly for a meeting with French mayors. Criquette continues, “A year ago, we wrote to all the mayors in France with a racecourse in their municipality with a questionnaire, and most of them very kindly replied to us. However, it’s a shame that the mayors with some of our most important racecourses didn’t respond. We asked them about the economic importance of the racecourses for their municipality; and then we organised a meeting at the National Assembly, which was very productive.” Martine Della Rocca Fasquelle adds, “This was the first time that mayors have been heard singing the praises of racing. We were surprised as we received reactions from very high up, including Emmanuel Macron, who congratulated us for the results of the racing industry.”

Spreading the word

Senators Sonia de la Prôvoté and Valérie Letard and spouses with Criquette Head, Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe 2021.

The CIFCH compiled the responses from 27 mayors, representing communes ranging from Chantilly and Cagnes-Sur-Mer, several municipalities in the West of France (which is a hive of activity for both trotting and gallop racing, training and breeding), to the homes of tracks organising just one or two meetings per year, into an album “Une Ville, Un Hippodrome: les maires ont la parole.” (towns and racecourses, in the words of their mayors). The brochure, which has been distributed to members and interested parties, is an advocacy of the benefits of racing to local communities.

Naturally, Isabelle Wojtoviez, mayoress of Chantilly, underlines the significance of the racecourse and training centre for the town, “It is impossible to imagine Chantilly without horses. The animal is at the centre of our economy, a pillar of our history and a vital tourist attraction...”

Bertrand de Guébriant, mayor of 5,000-inhabitant Craon in the West of France, where the racecourse hosts 10 meetings for a mixture of jumps, flat and trotting action, says, “Craon is one of the most popular provincial tracks in France, and we welcome 25,000 people for our ‘Trois Glorieuses’ festival each year, making it a major tourist attraction. The notoriety of our racing means that the town has a riding centre and a nearby training centre for employment with horses, whose most famous graduate is certainly (leading jump jockey) Clément Lefebvre. During racing periods, Craon enjoys visibility in the media, and finally, the community receives a share of pari-mutuel turnover, which is a real plus for our budget.”

With 80 meetings per year in the three disciplines, the racecourse at Cagnes-sur-Mer plays an important role in the town’s economy. And with its Côte d’Azur coastline, charming old town and proximity to Nice, it already has plenty of advantages.

Mayor Louis Nègre explains, “The image of Cagnes-sur-Mer is intimately linked to the racecourse, especially on an international level. The opportunity for visitors to enjoy racing in a spectacular environment overlooking the Mediterranean represents a unique experience, which contributes to tourists returning to the town. The economic activity connected to the racecourse and training centre is important year-round, while hotels, restaurants and the property markets benefit notably from racing during otherwise quiet periods of the season (during the winter flat and jumps meetings).”

Senator Anne-Catherine Loisier, vice-president of the CIFCH with Criquette Head and Deputy Géraldine Bannier, vice-president of the CIFCH.

The virtuous pari-mutuel model

For Criquette and her fellow CIFCH members and supporters, it is vital to spread positive messages such as these in order to preserve the favourable French system. “Racing has a colossal impact on the economic and environmental state of our country, and this is thanks to our PMU system which must be protected at all costs; however, I get the impression that it is being destroyed. When I see that (online betting operator) Ze Turf has been bought by (lottery and sports betting operator) La Française des Jeux, I fear that racing punters may be tempted away to bet on poker or other markets. We need the PMU and its financial input, which represents our livelihood and that of our regions, our studs and stables. My aim is to valorise and protect this ecosystem which is an example across Europe. France has by far the highest prize money in Europe, and that needs to be preserved. Our system also brings money in for the state; it’s a win-win system. Indeed during the Covid pandemic, the PMU registered good results because the football and all other activity was stopped. We were lucky that the state understood the need for racing and breeding activity to continue. This is a good demonstration of the importance for government to understand the depth of the racing activity and that it is not just a sport like football, for example.”

Racing across Europe and further afield is faced with issues of perception, either from the general public or government representatives. “An association like the CIFCH would have a role to play in other countries,” says Criquette, “but things are more complicated in nations with bookmakers. If you look at the rising powers in world racing nowadays, such as Hong Kong and Japan, they have adopted the pari-mutuel model. I think that the World Pool is a very good concept, which can contribute to promoting the tote system and help racing to raise its level on a global scale.”

“The CIFCH doesn’t get involved in specific debates such as the whip. Personally, I am in favour of limiting the number of strokes, but we must be careful not to overreact. Those who are against racing are people who have never been close to a horse at the races or in training; and one of the missions of the CIFCH is to demonstrate that horse welfare is at the centre of our profession. We are pleased to show newcomers behind the scenes and the quality of care which racehorses receive.”

Opening doors for future owners

After a series of visits, debates and conferences with decision-makers, the CIFCH is set to widen its contacts further in 2023, when a major focus for the committee will be a two-day event in June in Normandy, aimed at business people and potential owners.

Criquette explains, “We will invite entrepreneurs and business people who have nothing to do with racing to come and spend time at a stud farm and training centre in Normandy. Like a lot of people today, all they know about horses is that they have four legs, a head and a tail… Throughout my career I always welcomed people into my stable to discover the horses, and the reactions were invariably positive. Many of these [people] went on to become owners, not necessarily with me; and I was always pleased to see them develop their interest. I was brought up to be very open and welcoming, and now [that] I have free time, I want to continue to help people find out more about racing.”

Always renowned for her generosity with time and explanations, Criquette inherited these and many other qualities from her late father, the great breeder and trainer Alec Head who passed away last summer at age 97.

Criquette and fellow CIFCH members at a meeting in Chantilly, 2021.

“He has left us with a fantastic legacy, and I owe him my success. He always loved his profession and defended the racing industry; and along with Roland de Chambure, he was a precursor in opening up the market with the USA. One thing which struck me when I was younger was that he used to say, ‘You should always try to read your horse. Once you have understood your horse, then the horse will tell you what they are capable of’. I used to say the same thing to all the young assistants who came to work with me and who are now trainers. I told them to pick just one horse and ignore the 80 others; study that one horse, and then tell me what they observed as the horse developed. For me, that is the basis of training. Like people, no two horses are the same, and so you cannot follow the same recipe with them all. You can lose horses by rushing them, and during my era, we were fortunate to have plenty of time. Last year, once again, the examples of Flightline and Baaeed proved that it can be beneficial to wait.”

The family dynasty continues

Criquette’s brother Freddy Head called time on his illustrious training career last year, and the family name is now represented in the profession by his son, Classic-winning Christopher and daughter Victoria. “Papa would have been very proud to see Victoria win her first race recently, and Christopher’s success. Christopher spent time working alongside his father, and two years with me, and Victoria worked for much better trainers than me! She was with Gai Waterhouse, Aidan O’Brien and André Fabre, as well as with her father. We have (French racing channel) Equidia in the Bahamas, so I’m often in front of my TV at 6am here! I keep an eye on everyone, not just my family…”

In addition to owning horses or shares with a range of trainers in France and former assistant David Menuisier in the UK, Criquette also maintains her interest in breeding, despite the heart-wrenching sale of the family’s celebrated Haras du Quesnay last year.

“There were a lot of us—five including my mother—and we didn’t all have the same ideas, so it was a family decision to sell. I love breeding, so I will continue with five broodmares. My grandson Fernando (Laffon-Parias) wants to be an agent and is interested in breeding, so this year I planned all the matings with him. I did consider buying a farm myself, but finally my mares will stay at the Quesnay as the new owners are taking in boarders and have kept on all the old staff under manager Vincent Rimaud. So, I decided to stay, and I will enjoy returning to the stud. It will be a very different feeling for me to visit, with no pressure or concerns about managerial issues. I will just be able to go and admire my mares and foals!”

As ever, with Criquette, the love of horses shines through in her words. “We talk endlessly about the people involved with the horses, which is logical in a way, but in the end, everything depends upon the animal. At all levels, whether in breeding, training or racing, the horse always has the last word.” If Criquette has her way, this would also be true for politics!

The latest from Gavin Hernon

Zyzzyva on the left and Beeswax on the right.

2019 has been good to us thus far. I was delighted to see Zyzzyva and Beeswax both recently make the Chantilly winners enclosure, getting us out of an annoying bout of seconditis. Finishing second place is so very bittersweet for me. On the one hand the horse is well and has put in a good performance, on the other... well, it’s not first. If all our seconds had won, then we would have well passed our target of 10 winners for our first year; however, as my mother rightly said, “better second than second last” and I am truly over the moon with how our horses have been performing over the last few months. Our 14 runners since January 1 have tallied as 3 winners, 6 seconds, a third and 4 not hitting the frame.

As the flat season beckons in earnest, excitement has been building over the past few weeks as we assemble an exciting team of horses. In total, we anticipate having just over 20 horses for the season with a 50/50 split between older horses and juveniles. I am extremely grateful for the amount of people who have been willing to take a chance on a fresh face and I aim to reward every one of them by training their horses to run to the best of their ability.

This is without doubt my favourite time of year as we start to turn the screws on the older horses and the juveniles progress through their bone density training programme. The latter plays a significant part of our juvenile training programme and we commenced the programme mid January.

Training juveniles for bone density simultaneously conditions a horse’s lungs to the pressures they will encounter at race speed and prepares them very early on in their education for the mental pressures put on them whereby fast work becomes part of routine.

I had always been intrigued by the workings done on this by Dr John Fisher at Fair Hill in Maryland as well as the subsequent findings of studies done by David Nunamaker at the New Bolton Clinic in Pennsylvania and I strongly recommend reading up on it: bit.ly/buckedshins

The spread of equine flu has been cause for much concern over the past number of weeks, and it got worryingly close to our training centre when two yards were tested with positives just two miles away in Lamorlaye last week. We are doing all we can to not only boost our horses’ immune systems, but also to increase our biosecurity measures to give our horses every chance of not coming into contact with the virus. It did shock me to see English runners be allowed to run on French soil when their own racing authority deemed them unfit to run. That was an unfathomable logic.

Going forward, a big part of my attention will be on the health of my business as a whole.

Starting out in one of the biggest training centres on the continent brings its professional and financial pressures. We started out with a penetrative pricing model and will continue to operate as such for the 2019 season. Using some of the best raw materials on offer and having an excellent team of staff makes for very skinny margins at the end of the month. The fact that we have been winning races and showing results is by no means a bonus for our work, but a necessity.

January saw us delve into the world of claiming for the first time. Freiheit won her claimer well in Pornichet and was claimed for over €15,000. There is some excellent money that can be made even at this level of racing in France, her owners taking home €21,000 on the day.

We also dipped our toe into the other side of the claiming pool, purchasing an exceptionally well-bred Siyouni filly from the family of Bright Sky, named Siyoulater.

I can’t begin to describe how grateful I am for my excellent team! I feel we have found the perfect balance of youthful energy and wise experience. Regardless of age or experience, they all share a common vein in the fact that they simply love and enjoy horses. They make me very proud as they continue to do an excellent job. I strongly believe happy staff make happy horses, and happy horses win races. It takes as much care and attention matching morning riders to horses as it does matching jockeys. These people are essentially shaping your horses. To make a mistake and cause a personality clash in the morning could cost you dearly in the afternoon. …

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Hindsight - Alec Head

By Oscar Yeadon

Oscar Yeadon recently caught up with Alec Head to look back on his remarkable career as jockey, trainer and breeder, and his part in the enduring Head training dynasty and development of the thoroughbred pedigree in Europe.

Your grandfather William Head Sr. was a steeplechase jockey in Britain before moving to France in the 1870s and later established the training business that you ultimately became part of. Did you ever have an ambition to have a career outside of racing?

“I don’t know why my grandfather came to France, particularly, but he set up in Maisons-Laffitte and then my father set up in Chantilly and everything followed from there. I don’t think I could have done anything else!”

What was your first involvement in racing?

Alec Head (second right) with father, William (right), grand-daughter Patricia, Criquette and Freddy (in the family colours), 1982.

“It was around 1942, when I started race riding. I won the big race over jumps at Auteuil, and was riding on the Flat as well, but got too heavy. We raced through the war and it was tough, and I used to bicycle everywhere. The Germans would go to the races as well, so racing continued but a lot of the courses were shut, so they organised Flat and Jumps meetings at the few that were open, such as Auteuil and Maisons-Laffitte.

“Racing recovered fairly quickly after the war and I stopped riding towards the end of the decade, because I was by then married and my wife Ghislaine said I should stop!

“So I started training and had always planned to do so - what else could I do? We had very few horses, but the business grew organically by winning races. I had some luck in sending horses to Italy, who won their races there, which attracted some Italian owners, who then sent me horses, including Nuccio.

And Nuccio was your big break?

“Yes, Nuccio provided my big break, when he won the Arc in 1952 for the Aga Khan III, who had purchased him the season before. That led to the development of a relationship with Prince Aly Khan, who was a unbelievable, a superman. He could have bought two mountains.”

The Arc has certainly proven a special race for your family...

“Yes, my father twice trained the winner, including Bon Mot, who was ridden by my son, Freddie, the youngest jockey to win the race at that point, aged 19. My daughter Criquette trained Three Troikas to win in 1979, ridden by Freddie and owned by Ghislaine, while Treve’s two wins followed that of Criquette’s son-in-law, Carlos Laffon Parias, with Solemia.”

Treve was bred at Haras du Quesnay, which has been home to your breeding operation for sixty years. How did it start?

“About 10 years into my training career, I was looking for a stud as I love breeding. The stud had not been in use for many years and was not very well known, but I knew the guy who was dealing with Mrs Macomber [the widow of A Kingsley Macomber, who had owned a Preakness winner and also won the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe with Parth].

Haras du Quesnay

“The stud was in bad shape, having been unoccupied since the Germans during the war. It took two years to get it up and running, as we could only afford to do it gradually.”

As a breeder, you have been widely acknowledged as a major influence by bringing American bloodlines to Europe. What are your memories of that period?

“The US bloodlines were doing well and we went to Keeneland and were lucky to buy the likes of Riverman, Lyphard and many others. We would later sell some back to the US, for which we received some criticism as some of the stallions were syndicated and the shareholders liked the money to spend on other stuff!

“Some of those stallions injected new blood into the French breeding industry and you can draw parallels with what Northern Dancer brought to Ireland, through Europe.”

What are your thoughts on the recent moves by the European Pattern Committee to enhance the stayers’ programme?

“It’s a very good thing. You can see the interest is these races. Look at the crowd for the Ascot Gold Cup this year. It’s a great race to win, as I did with Sheshoon, but I was fortunate to have a good jockey in George Moore, who was very smart. Sheshoon was difficult and very temperamental. It’s very important for a stable to have a good long-term stable jockey. Look at Dettori with Gosden.”

Do you think it’s harder or easier for the trainers of today to forge a successful career?

“I really don’t think there’s any difference between then and now. Gosden, de Royer-Dupre and others, are all 70-year-olds, or so, and they’re still at the top.

“At my peak, I had around 120 horses and, later in my career, only trained for Pierre Wertheimer and the Aga Khan. They were top breeders and it was wonderful. Mr Wertheimer gave me the money to buy horses from all over the world. I wouldn’t say I was a pioneer; I was very lucky!

“I think maybe it’s harder for younger trainers today, as the bigger owners have mostly disappeared, but it was hard in our time, too!

Of the trainers who were contemporaries of yours, who stands out?

“At the sales or on the racecourse, I would often run against Vincent O’Brien. He was a genius. He trained Derby winners and Grand National winners. He was very smart, he really was something else. You don’t have trainers who both codes at that level these days.”

Is there anything that you would change about racing today?

“I think racing’s wonderful, so there’s nothing I can really say I would want to change. I had everything I needed as a trainer in Chantilly. The track is beautiful, and you have a forest where you can work and the new dirt track is very good. Having lots of trees means it’s very sheltered. But I would also say Newmarket is a beautiful training centre.”

And what do you feel was your greatest achievement?

“Breeding Treve, that was the best accomplishment. She was unbelievable and unlucky not to win three Arcs.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Starting out - the latest update from new trainer - Gavin Hernon

Saturday 18th August 2018, a dream start and a day that will live very long in the memory.

To win a Deauville maiden, an hour before the hammer starts to fall on some of the best-bred yearlings in Europe would be a special moment for most trainers. I still need to pinch myself to be sure I'm not in a dream to have won the Prix Des Etalons Shadwell with my first runner.

Icefinger is a horse we have always thought might have a touch of class. We had given him Group entries before his race but we might opt for a Listed race to allow him grow up. His very relaxed manner at home just meant that it took him a bit of time to come to hand. Despite our belief in him, I never thought he would be able to beat nice horses who had experience in regarded maidens at the first time of asking. That day was a nice way to culminate the start-up phase of our yard.

ICEFINGER

I firmly believe that the authorization and licensing process in France is the best grounding one can get. That said, it still doesn't quite prepare me for what comes next. Establishing a company in France and getting all the necessary paperwork in place isn't the most straightforward and this is probably an area where France lags behind other neighbouring countries. Admittedly, through August most of Europe takes the month as a holiday which adds to the timeline to do anything. It probably doesn't help that I'm wired to prefer spending time outside with the horses.

I am fortunate that I have an excellent accounting firm in Equicer guiding me through everything step by step and now we're fully set up and running. Even my bank account got held up in the bureaucracy so I'm grateful to my suppliers for their patience.

I feel it is necessary to say that Olivier Delloye of France Galop is an exception and his help throughout has been nothing short of phenomenal given his busy schedule and without him, Icefinger probably would not have been able to run when he did.

My previous update had been written days before myself and my girlfriend, Alice moved into what had served as a lucky yard to Mr. Francois Doumen on the Chemin du Mont De Po. It boasts 25 of some of the newest stables to be built in Chantilly and direct access to Les Aigles and Les Lions training centres. We are very excited to be training from here, the horses love the bright, well circulated boxes and we have settled in well.

We're up and running with three horses in the yard so far, for three different owners, and they've all run already! I'm lucky to have three good owners to start with, who all are interested in doing more and having more horses in France. Icefinger is a dream, one that his owner BLC Horse Racing, agent Morten Buskop and I are hoping will take us to exciting places over the coming months. We'll take it step by step as he still needs to learn more about his job!

We tried to be adventurous with Repercussion, entering him in the Prix Quincey. He is a quirky horse, but he has a lot of ability and just needs things his own way a little bit. Maybe a confidence booster might be best for him!

Epic Challenge is a gent of a horse who has quite a bit of ability. He found instant fame in Chantilly helping to catch a loose filly and being very chivalrous about the whole encounter. Despite his gentle nature, his testicles appear to be causing him some pain and he is set to be gelded in the coming days. I see him having a bit in hand off his UK mark of 83 in time.

We've been working hard to get around the sales and meet people to try and strike up and build relationships with new owners and horses and all going well we've got a few things in the pipeline. It's very difficult at this stage as we have to balance between managing the horses we have in and picking up new ones. Currently it's only Alice and I in the yard which makes getting away that bit harder - Alice is doing a great job riding the horses as evidenced by Icefinger! We've managed to attract a couple of experienced exercise riders for the yard as well who all come on board in the coming weeks and we'll start to get into a more established routine on a bigger scale.

Understandably, our current model of training three horses is far from being a financially viable one. It is however, what I consider to be a key stage in presenting what we do to potential clients. Attracting support in this industry has never been easy, particularly if there aren't results to back it up and I felt that if we could show some results from limited numbers during the sales season, it might just tip some potential clients over our side of the fence and be worth the financial risk.

The moment the first horses arrived on to this yard, life took a significant turn and a commitment was made to give maximum effort in getting the best out of each and every individual that walked into the yard.

There are no hiding places on any racetrack and without an attention to detail that rivals the competition, 4.30 a.m. starts would be in vain and days like Saturday, 18th August 2018 would remain as dreams unfulfilled.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Trainer Profile - Nicolas Clément

Monsieur le président

By Alex Cairns

The Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe is often cited as one of the races trainers would most like to win. To reach such a pinnacle generally takes a lifetime of steady building. Powerful owners must be recruited, facilities enhanced, elite stock acquired. So when three-year-old colt Saumarez landed France’s premier prize in 1990, his trainer Nicolas Clément signalled himself as a major outlier. In just his second full season with a licence and with his first Arc runner, he had become the youngest trainer ever to win the race. Aged 26, he went from relative obscurity to international renown. But this was no flash in the pan. With 30 years’ training experience now under his belt, Clément has proved he does consistency as well as precocity. And he will surely leave a notable legacy through both his on-track achievements and his actions as president of the French trainers’ association. We tracked Nicolas down on the wooded gallops of Chantilly to talk communication, competition, and cooperation.

VOCATION

Being raised in Chantilly is always likely to increase one’s chances of being involved in the racing world. Add in being the son of Classic-winning trainer Miguel Clément and Nicolas’ vocation appears predestined. It could have been very different however.

‘I went to high school in Paris and my mother wanted me to go into business. We compromised with vet studies, but I only lasted two months and then told her I’d got a job on a farm in Normandy. I had always been drawn to horses and racing was my passion from a young age. I spent some time at Taylor Made in America, learning how the whole thing works straight from the farm. This gives a great understanding of the whole cycle; breeding to race and then racing to breed. After that I worked for John Gosden, Vincent O’Brien, and François Boutin. So I was lucky to learn from some of the best in the business. I then got my licence and set up in my father’s yard in 1988.’

This was the yard from which Miguel Clément had sent out Nelcius to win the Prix du Jockey Club in 1966, just one highlight from a successful career sadly cut short at the age of 42. Despite Miguel’s early death, Nicolas still feels a paternal influence.

‘I was very young when my father died, so didn’t get the opportunity to learn as much as I might have from him. He was always an advocate of keeping your horses in the worst company and yourself in the best and I have certainly tried to follow that ethos. He was good friends with a lot of influential people such as Robert Sangster and he had many English and American owners. This open, international approach wasn’t so common in my father’s time and I took a lot from it.’

Taking on the family business in his mid-twenties surely came with a degree of pressure for Nicolas, but winning the Arc at the first attempt is not the worst way to establish one’s credentials.

‘Winning the Arc at such an early stage of my career was exceptional, but it didn’t turn my head. I’ve always known this game is full of ups and downs. Saumarez’ victory definitely put my name out there all the same and helped me expand my stable, with more owners and better stock. Since then we’ve enjoyed more big days thanks to the likes of Vespone and Stormy River. Style Vendome won the French 2,000 Guineas for long-standing owner André de Ganay in 2013 and that was something special. I had bought him at the sales with my partner Tina Rau for less than €100,000. Not many sold at that price go on to be Guineas winners. In the past few seasons The Juliet Rose has been a wonderful filly for us. She took time, but excelled over a mile and a half.’

COMPETITION