Dangers of inbreeding and the necessity to preserve sire lines in the thoroughbred breed

Inbreeding is the proportion of the genome identically inherited from both parents.

Inbreeding coefficients can be estimated from pedigrees, but pedigree underestimates the true level of inbreeding. Genomics can measure the true level of inbreeding by examining the extent of homozygosity (identical state) in the DNA of a horse. A mechanism to examine genomic inbreeding for breeding purposes has yet to be developed to be used by all breeders but once available, it must be considered as a tool for breeders.

Breeding of potential champion racehorses is a global multi-billion sterling or dollar business, but there is no systematic industry-mediated genetic population management.

Inbreeding in the modern thoroughbred

The thoroughbred horse has low genetic diversity relative to most other horse breeds, with a small effective population size and a trend of increasing inbreeding.

A trend in increased inbreeding in the global thoroughbred population has been reported during the last five decades, which is unlikely to be halted due to current breeding practices.

Ninety-seven percent of pedigrees of the horses included in a recent study feature the ancestral sire, Northern Dancer (1961); and 35% and 55% of pedigrees in EUR and ANZ contain Sadler’s Wells (1981) and Danehill (1986), respectively.

Inbreeding can expose harmful recessive mutations that are otherwise masked by ‘normal’ versions of the gene. This results in mutational load in populations that may negatively impact on population viability.

Genomics measured inbreeding is negatively associated with racing in Europe and Australia. The science indicates that increasing inbreeding in the population could further reduce viability to race.

In North America, it has been demonstrated that higher inbreeding is associated with lower number of races. In the North American thoroughbred, horses with higher levels of inbreeding are less durable than animals with lower levels of inbreeding. Considering the rising trend of inbreeding in the population, these results indicate that there may also be a parallel trajectory towards breeding less robust animals.

Note that breeding practices that promote inbreeding have not resulted in a population of faster horses. The results of studies, generated for the first time using a large cohort of globally representative genotypes, corroborate this.1,3

Health and disease genes

It is both interesting and worrisome to consider also that many of the performance-limiting genetic diseases in the thoroughbred do not generally negatively impact on suitability for breeding; some diseases, with known heritable components, are successfully managed by surgery (osteochondrosis dessicans, recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, for example), nutritional and exercise management (recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis), and medication (exercise induced pulmonary haemorrhage). This unfortunately facilitates retention of risk alleles in the population and enhances the potential for rapid proliferation of risk alleles if they are carried by successful stallions.

Types of inbreeding

Not all inbreeding is bad. Breeders have made selections for beneficial genes/traits over the generations, resulting in some inbreeding signals being favoured as they likely contain beneficial genes for racing. Importantly, examination of a pedigree cannot determine precisely the extent of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ inbreeding. This can only be determined from DNA analysis.

Historic inbreeding (arising from distant pedigree duplicates) results in short stretches of DNA identically inherited from sire and dam.

This may be considered ‘good’ inbreeding.

It has no negative effect on racing.

The horse may be carrying beneficial mutations that have been maintained from distant ancestors through breeders’ selection.

Recent inbreeding (arising from close pedigree duplicates) results in long stretches of DNA identically inherited from sire and dam.

This may be considered ‘bad’ inbreeding.

It is negatively associated with racing.

The horse may be carrying harmful mutations that have not yet been ‘purged’ from the population.

Obviously, in terms of breeding, it’s always possible to find examples and counterexamples of remarkable individuals; but the science of genetics is based on statistics and not on individual cases.

Sire lines

Analysis of the Y chromosome is the best-established way to reconstruct paternal family history in humans and animal species. The paternally inherited Y chromosome displays the population genetic history of males. While modern domestic horses (Equus caballus) exhibit abundant diversity within maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA, until recently, only limited Y-chromosomal sequence diversity has been detected.

Early studies in the horse indicated that the nucleotide variability of the modern horse Y chromosome is extremely low, resulting in six haplotypes (HT). However, this view has changed with the identification of new genetic markers, showing that there is considerably more genetic diversity on the horse Y chromosome than originally thought. Unfortunately, in thoroughbreds, the male gene pool is restricted, with only three paternal lines remaining.

The Institute of Animal breeding and genetics of the Veterinary Medicine School at Vienna applied fine-scaled Y-chromosomal haplotyping in horses and demonstrated the potential of this approach to address the ancestry of sire lines. They were able to show the microcosmos of the Tb-clade in the thoroughbred sire lines.

It is interesting to note that more than half of the domestic horses in the dataset (76 of 130) have a Y chromosome with a thoroughbred ‘signature’. These includes thoroughbreds, standardbreds, many thoroughbred-influenced breeds (warmbloods, American quarter horses, Franches-Montagnes, a Lipizzan stallion and the Akhal-Tekes).

The General Stud Book shows that thoroughbred sire lines trace back to three founding stallions that were imported to England at the end of the 17th century. 5 Now, the heritage of the thoroughbred sire lines can be better understood using Y chromosome information. It is now possible to clearly distinguish sublines of Darley Arabian, born in 1700 (Tb-d) and Godolphin Arabian, born in 1724 (formerly Tb-g, now Tb-oB3b). The third founder, Byerley Turk, born in 1680, was characterised by the Tb-oB1 clade. According to pedigree information, only few of the tested males trace back paternally to Byerley Turk, which are nearly extinct.

There are now 10 different Y chromosome sub-types known in the thoroughbred. Two come from the Godolphin Arabian, five come from Byerley Turk, and three come from Darley Arabian.

Even if genetic analysis shows that there was an error in the stud book recording of St Simon’s parentage and that horses descending from St Simon should be attributed to the Byerley Turk lineage, probably 90% of the current stallions are from the Darley Arabian male line. So, there is a true risk that we could lose a major part of the Y chromosome diversity.

Conclusions and solutions

We should do everything we can to ensure that thoroughbreds are being sustainably bred and managed for future generations. With the breeding goal to produce viable racehorses, we need to ask ourselves, are we on track as breeders?

If inbreeding is negatively affecting the chances of racing and resulting in less durable racehorses, will this continue to affect foal crops in the future? How can we avert the threat of breeding horses that are less able to race? If the ability to race is in jeopardy, then is the existence of the thoroughbred breed at risk?

International breeding authorities are studying the situation and thinking about general measures allowing the sustainability of the breed.

Breeders

What can individual breeders do to produce attractive foals that are safe from genetic threats? How do you avoid the risk of breeding horses that are less fit to race?

There is no miracle recipe, and each breeder legitimately has his preferences.

An increasingly important criteria for the choice of a stallion is his physical resistance and his vitality, as well as those of his family. It is often preferable to avoid using individuals who have shown constitutive weaknesses, or who seem to transmit them.

The use of stallions from different male lines can make it possible to sublimate a strain and better manage the following generations. The study of pedigrees must exceed the three generations of catalogue pages.

In the future, genomics—the science that studies all the genetic material of an individual or a species, encoded in its DNA—will certainly be able to provide predictive tools to breeders. This is a track to follow.

Trainers

Trainers should be aware of the danger of ‘diminishing returns,’ where excessive inbreeding occurs. Today, when animal welfare and the fight against doping are essential parameters, it is obvious that trainers must be aware of the genetic risks incurred by horses possibly carrying genetic defects.

Together with bloodstock agents, trainers are the advisers for the owners when buying a horse. Trainers already know some special traits of different families or stallions, but genomic tools might become essential for them too.

Sources

1. Genomic inbreeding trends, influential sire lines and selection in the global Thoroughbred horse population Beatrice A. McGivney 1, Haige Han1,2, Leanne R. Corduff1, Lisa M. Katz3, Teruaki Tozaki 4, David E. MacHugh2,5 & Emmeline W. Hill ; 2020. Scientific Reports | (2020) 10:466 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57389-5

2. Inbreeding depression and durability in the North American Thoroughbred horse Emmeline W. Hill, Beatrice A. McGivney, David E. MacHugh; 2022. Animal Genetics. 2023;00:1–4. _wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/age

3. Founder-specific inbreeding depression affects racing performance in Thoroughbred Horses. Evelyn T. Todd, Simon Y. W. Ho, Peter C. Thomson, Rachel A. Ang, Brandon D. Velie & Natasha A. Hamilton; 2017. Scientific Reports | (2018) 8:6167 | DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-24663-x

4. The horse Y chromosome as an informative marker for tracing sire lines Sabine Felkel, Claus Vogl , Doris Rigler, Viktoria Dobretsberger, Bhanu P. Chowdhary, Ottmar Distl , Ruedi Fries , Vidhya Jagannathan, Jan E. Janečka, Tosso Leeb , Gabriella Lindgren, Molly McCue, Julia Metzger , Markus Neuditschko, Thomas Rattei , Terje Raudsepp, Stefan Rieder, Carl-Johan Rubin, Robert Schaefer, Christian Schlötterer, Georg Thaller, Jens Tetens, Brandon Velie, Gottfried Brem & Barbara Wallner; 2018. Scientific Reports | (2019) 9:6095 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42640-w

5. Identification of Genetic Variation on the Horse Y Chromosome and the Tracing of Male Founder Lineages in Modern Breeds Barbara Wallner, Claus Vogl, Priyank Shukla, Joerg P. Burgstaller, Thomas Druml, Gottfried Brem Institute of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Depart. 2012. PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org April 2013, Volume 8, Issue 4, e60015

6. New genetic evidence proves that the recorded pedigrees of the influential leading sires Bend Or and St. Simon were incorrect. Alan Porter; ITB 2021

7. Eight Belle’s breakdown: a predictable tragedy William Nack; ESPN.com 2008

8. Suzi Prichard-Jones: Founder of "The Byerley Turk & Godolphin Arabian Conservation Project"

Special thanks to Emmeline Hill for her help in the completion of this article

Artificial Intelligence tools - and their growing use in racing

Book 1 of the Tattersalls October Yearling Sale is traditionally where some of the finest horseflesh in the world is bought and sold. The 2022 record-busting auction saw 424 lots pass through its hallowed rotunda for a total of 126,671,000 guineas. One of the jewels in the crown was undoubtedly lot 379, a Frankel colt out of Blue Waltz, who was knocked down to Coolmore's M.V. Magnier, joined by Peter Brant, for 1,900,000 guineas.

It is easy to see why lot 379 made Coolmore open its purse strings. He has a stallion’s pedigree, being out of a Pivotal mare. His sire has enjoyed a banner year on the track, with eight individual Gp/Gr1 winners in 2022. He is a full brother to the winning Blue Boat, himself a 450,000 guineas purchase for Juddmonte Farms at Book 1 in 2020. Lot 379 is undeniably impressive on the page.

But it is not his impeccable pedigree that makes Tom Wilson believe lot 379 has the makings of a future champion. “The machine doesn’t have any biases. It doesn’t know whether it’s a Galileo or a Dubawi or a Havana Grey,” he says. “The machine just looks at the movement of the horse and scores it as it sees it. It has no preconceptions about who the elite sires in the market are. It’s completely neutral.”

The “machine” to which Wilson is referring is, in reality, a complex computational model that he claims can predict with 73 percent accuracy whether a horse will be elite (which he defines as an official rating of 90 or above, or the equivalent in its own jurisdiction) or non-elite (horses rated 60 or below) based on its walk alone. It’s a bold claim. So how does he do it?

First, Wilson taught an open source artificial intelligence tool, DeepLabCut, to track the movements of the horse at the walk. To do this, he fed it thousands of hours of footage. He then extracted around 100 frames from each video and manually labelled the body parts. “You teach it what a hock is, what a fetlock is, what a hip is,” he explains. “Eventually, when you feed new videos through, it automatically recognises them and plots the points. Then you can map the trajectories and the angles.”

He then feeds this information into a separate video classification algorithm that analyses the video and compares it to historic data in order to generate a predicted rating for the horse. “Since 2018, I’ve taken about 5,000 videos of yearlings from sales all around the world with the same kind of biometric markers placed on them and then gone through the results and mapped what performance rating each yearling got,” he says. “So we’re marrying together the video input from the sale to the actual results achieved on track.”

Lot 379 has a projected official rating of 107 based on his biomechanics alone, the highest of all the Frankel’s on offer in Book 1 (yes, even higher than the 2,800,000 gns colt purchased by Godolphin). Wilson’s findings have been greeted with scepticism in some quarters. “There’s so many other factors that you can’t measure,” points out trainer Daniel Kübler. “There’s no way an external video can understand the internal organs of a horse, which you can find through vetting. If it’s had an issue with its lungs, for example, it doesn’t matter how good it looks. If it’s inefficient at getting oxygen into its system, it’s not going to be a good racehorse.”

“It’s not a silver bullet,” concedes Wilson. “There are multiple ways to find good horses. It’s just another metric, or set of metrics, that helps.” But is it really “just another metric,” or the opening salvo in a data revolution that has the potential to transform the way racehorses are bought and sold?

Big data. Analytics. Moneyball. It goes by many names, but the use of data in sports is, of course, nothing new. It was brought to popular attention by Michael Lewis in his 2003 book Moneyball and by the 2011 film of the same name starring Brad Pitt.

It charted the fortunes of the Oakland Athletics baseball team. You know the story: Because of their smaller budget compared to rivals such as the New York Yankees, Oakland had to find players who were undervalued by the market. To do this, they applied an analytical, evidence-based approach called sabermetrics. The term ‘sabermetrics’ was coined by legendary baseball statistician Bill James. It refers to the statistical analysis of baseball records to evaluate and compare the performance of individual players. Sabermetrics has subsequently been adopted by a slew of other Major League Baseball teams (in fact, you would be hard pressed to find an MLB team that doesn’t employ a full-time sabermetrics analyst), and ‘moneyball’ has well and truly entered the sporting lexicon on both sides of the Atlantic.

Take Brentford FC. As recently as 2014, the West London club was languishing in the third tier of English football. Today, Brentford is enjoying its second consecutive season in the top flight (Premier League), bucking the trend of teams that gain promotion only to slingshot back down to the lower leagues after one season.

What is their secret? Moneyball. Brentford’s backroom staff has access to vast streams of data that detail how their players rank across a number of key metrics. This information helps them make day-to-day training ground decisions. But crucially, it also shapes their activity in the transfer market by helping them to identify undervalued players to sell on for a profit. Players such as Ezri Konsa, purchased from Charlton for a rumoured £2.5 million in 2018 before being sold, one year later, to Aston Villa for a £10 million profit. Think of it as the footballing equivalent of pinhooking.

The bottom line is that data analysis has already transformed the way athletes are recruited and trained across a range of sports. It stands to reason, therefore, that statistical modelling could help buyers who are spending, on average, 298,752 guineas for a yearling at Book 1 make informed purchasing decisions.

“I’ve always been interested in applying data and technology to an industry that doesn’t exactly embrace technology.” That’s according to star bloodstock agent Bryon Rogers. Rogers is widely regarded as the godfather of the biometrics movement in racing. “The thoroughbred industry is one that moves slowly, rather than quickly,” he adds, with a dash of irony.

Having cut his teeth at Arrowfield Stud in his native Australia and Taylor Made Farm in Kentucky, in 2011 he started his own company, Performance Genetics. As its name implies, the company initially focused on DNA sequencing, attempting to identify markers that differentiated elite and non-elite horses.

From there, it branched out into cardiovascular and biomechanical research. Rogers quickly discovered that it was the biomechanical factors that were the most influential in terms of identifying future elite horses. “When you put all the variables in, the ones that surface to the top as the most important are actually the biomechanical features: the way the horse moves and the way the horse is constructed. They outweigh DNA markers and cardiovascular measurements,” he explains.

According to Rogers, roughly a fifth (19.5 percent, to be exact) of what makes a horse a horse is explained by the way it moves. “That’s not to say that [those other factors] are not important. It’s just that if you’re ranking them by importance, the biomechanical features are more important than the cardiovascular ones.”

His flag bearer is Malavath. Purchased at the 2020 Goffs Premier Yearling Sale for £29,000, she was first sold for €139,200 at the Arqana Breeze Up Sale the following year. “I know when I’ve found one,” recounts Rogers. “I walked up to her [at the sale], and there was nobody else there. At that time, [her sire] Mehmas wasn’t who he was. But her scores, for us, were an A plus. She shared a lot of the common things with the good sprinter-milers that we’ve got in the database. A lot of the dimensions were very similar, so she fit into that profile.” She has since proven herself as a Gp2 winner and most recently finished second behind Kinross in the Prix de La Forêt on Arc day.

In December 2022, Malavath sold again, but this time for €3.2m to Moyglare Stud and is set to continue her racing career in North America under the tutelage of Christophe Clement.

A find like Malavath has only been made possible through the rapid development of deep learning and artificial intelligence in recent years. Rogers’s own models build on technology originally developed for driverless cars—essentially, how a car uses complex visual sensors and deep learning to figure out what’s happening around it in order to make a decision about what to do next.

But wait. What is deep learning? Here comes the science bit! Machine learning and deep learning are both types of artificial intelligence. “Classical” machine learning is A.I. that can automatically adapt with minimal human interference. Deep learning is a form of machine learning that uses artificial neural networks to mimic the learning process of the human brain by recognising patterns the same way that the human nervous system does, including structures like the retina.

“My dad’s an eye surgeon in Australia and he was always of the opinion that what will be solved first in artificial intelligence will be anything to do with vision,” says Rogers knowingly. Deep learning is much more computationally complex than traditional machine learning. It is capable of modelling patterns in data as sophisticated, multi-layered networks and, as such, can produce more accurate models than other methods.

Chances are you’ve already encountered a deep neural network. In 2016, Google Translate transitioned from its old, phrase-based statistical machine translation algorithm to a deep neural network. The result was that its output improved dramatically from churning out often comical non-sequiturs to producing sentences that are closely indistinguishable from a professional human translator.

So does this mean that the received wisdom around how yearlings are selected is outdated, subjective and flawed? Not exactly. “There are so many different ways of being a good horse; I don’t think [selecting horses] will ever completely lose its appeal as an art form,” says Rogers. “But when we get all this data together and we start to look at all these data points, it does push you towards a most predictable horse.” In other words, following the data will not lead you to a diamond in the rough; rather, it’s about playing the percentages. And that’s before all before the horse goes into training.

After that point, the data only gets you so far. “I would say [the use of biomechanical modelling] probably explains somewhere between 30 to 40 percent of outcome,” says Rogers. “It’s very hard to disentangle. The good racehorse trainer has got all the other things working with him: he’s got the good jockeys, the good vet, the good work riders. He’s got all of those things, and their effect on racetrack outcomes is very hard to model and very hard to disaggregate from what we do.”

Nevertheless, it does not look like big data is going away any time soon. “It might be a couple of years away,” says Rogers. “As bloodstock gets more and more expensive and as the cost of raising a horse gets more and more expensive, the use of science is going to rise.” He believes there’s already an analytics arms race happening behind the scenes.

“For me, it isn’t a case of if it’s valuable; it’s a case of when it will be recognised as being valuable.” That’s Wilson again. “What you see in every sport is a big drive towards using statistical analysis and machine learning to qualify and understand performance. Every other sporting sector tells us that these methods will be adopted, and the ones that adopt them first will gain a performance edge over the rest of the field.”

Comparisons to Deep Blue’s defeat of Garry Kasparov might be premature, but it is clear that the racing industry is fast approaching a tipping point. “I don’t think the machine on its own beats the human judge,” says Wilson. “But I think where you get the real benefit is when you use the information you've been given by machine learning and you combine that with deep human expertise. That’s where the application of these types of things are the most successful in any sport. It’s the combination of human and machine that is power. Humans and machines don’t have to compete with each other.”

So will more trainers be adopting the technology? “There’s lots of different data points that you can use to predict a horse’s potential, and it’s understanding all of the pieces together,” says Kübler. “I’d want a bit more proof of concept. Show me that your system is going to save me loads of time and add loads of value. We’ll see in three or four years’ time how good it was.”

In the meantime, all eyes will be on Lot 379.

Dermot Cantillon - What it takes to breed winners and run a racecourse

Article by Daragh Ó Conchúir

“My philosophy is if you’re in something and you can get into a position where you can bring change about for the common good, that’s a thing to aim for. I’m not one for being a hurler on the ditch, give out and not try and do anything about it.”

Dermot Cantillon, The Irish Field (February 24, 2018)

Living true to his motto, Dermot Cantillon ran for election to Seanad Éireann—the upper house of the Irish Legislature (the Oireachtas)—two years ago. He was prompted to do so, even though he had no political background or experience, by a firm belief that horse racing and the bloodstock industry lacked representation despite their significance to national and local economies.

As an independent candidate, the Co Waterford native was up against the powerful party machines with their established lobbies and financial clout, so it did not come as a big surprise he did not make the cut. But he would not have been true to himself and his ideals had he not had a go.

Proactivity is a default setting for Cantillon, who along with his equally industry-immersed wife Meta Osborne, owns and runs Tinnakill House Stud in the Laois village of Coolrain. As a man who has walked the walk and continues to do so, he is always worth listening to on matters pertaining to the sport and business of thoroughbred racing.

Apart from being a breeder of multiple Gp. 1 winners and overseeing a flourishing enterprise for two decades, Cantillon has also helped steward the massive strides made by Naas Racecourse in 13 years as chairman.

In addition, the 62-year-old is chairman of Irish Thoroughbred Marketing, a director of Goffs and board member of the Irish Equine Centre. Previously, he has served as chairman and president of the Irish Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association, chairman of Tote Ireland and director of Horse Racing Ireland.

He also served as manager of the Smurfit family’s Forenaghts Stud outside Naas for 32 years until standing down two years ago. This is a polymath on breeding, selling and running racehorses.

Osborne is the daughter of Michael, the late Irish Turf Club (IHRB) senior steward and Irish National Stud managing director. He was also the creator of Dubai as an international racing venue and of Sheikh Mohammed’s stud operations in Ireland. Meta would follow in her father’s footsteps by becoming the first woman—and still the only one—to be Turf Club/IHRB senior steward and is a current HRI director.

She is Kildangan Stud’s chief vet, having worked there for 34 years, while her family has been inextricably linked with Naas Racecourse since its foundation.

She and Cantillon make a good couple and that they don’t agree on everything is a positive. Among the many things they shared a page on was the desire to own their own stud. They bought Tinnakill in 2002 when it was a sheep farm, and the fecundity of the land and broodmares that have inhabited it since has propagated substantial success. Among the stellar cast of those bred there are Alexander Goldrun, Red Evie (dam of Arc-winning Breeders’ Cup heroine Found) and Casamento.

As a four-time Gp. 1 winner in four countries and three continents before injury brought his career to a premature conclusion last month, State Of Rest is the best though.

Due to the colt’s astounding feats in adding the Prix Ganay and Prince of Wales’ Stakes this year to last season’s Saratoga Derby and Cox Plate triumphs, Juddmonte made a bid for the son of Starspangledbanner’s 10-year-old Quiet American homebred dam Repose, who is in foal to Frankel.

“To be perfectly honest, like most Irish people in the industry, I’m a trader at heart,” Cantillon relates. “By definition then, if a big enough offer comes along, you’re gonna sell. Legacy is important but at the same time being able to meet your commitments for a long period of time and the security of that is also very important; and that won it over for me. She became too valuable a mare nearly to hold on to in proportion to the other mares I had. She was worth nearly more than everything else put together. That’s a total imbalance.

“We have a philosophy to buy taproot-type females in outstanding American and European families, and she was the embodiment of that in that her dam Monaassabaat, who we bought initially, was out of It’s In The Air, who was one of the best mares in America ever (five of her 16 triumphs were Gr. 1’s) and also a fabulous producer. So it was an overnight success that took 15 years.”

Despite the windfall, Cantillon will not be splurging unnecessarily, though he will look to improve the lowest bar. With around 40 mares, Tinnakill focuses on quantity; and thanks to their canny approach and eye for a bargain, that tends to produce some quality along the way.

“We don’t spend a lot at the sales. We buy mares from one grand to maybe seventy five. That’s the comfort zone for us, and that’s where we intend to stay. To be successful at that level, you need a lot of mares; and you hope some will make it big for you. The philosophy is probably to throw enough at the wall and some of it will stick.”

They are willing to sell their homebreds at any stage up to and including as a racehorse but will not be forced into accepting a price that doesn’t match their value.

“I see five different opportunities to sell along the way. The first one is in utero, the second one is the foal, the third is yearlings, the fourth is breeze-ups and the fifth one—the ultimate one—is in training. So within the philosophy of business, all five operate—and I’d say more so now, the fifth one. To show confidence in our own yearlings especially, we’ll keep 25 percent in them in partnership if whoever buys them asks us to do so. We’ll go to the next level on the understanding that if they prove themselves on the racetrack, they will get sold in a commercial way.

“We’d predominantly be known as foal sellers, and we sell a lot of foals in England and Ireland. People want foals that they can bring to the Orby and so on, and we sell those sort of foals. If they make money, so be it.

“We tend to keep any foal after the 15th of April. People have an idea of what a foal should look like—it’s a good, strong foal. As they head towards a May foal, the discount that you’re expected to take can be fairly big, so we don’t tend to bring the later foals to the foal sales; they tend to go on to the yearling sales. At the yearling sales, we bring mostly foals we failed to sell because we didn’t get what we thought the foal should’ve made, and also later foals.”

The demand for precocity and immediate results has inflated that specific market, but that means there is value for discerning buyers.

“What happens at yearling and foal sales is that people have a certain view of what a good foal or a good yearling should look like, and most people have exactly the same view. So if you have that particular product, you get a big premium. But for people buying horses, I think the value is slightly to either side and for a deviation of 10 percent, you might get a discount of 50.

“So if you can forgive some slight physical flaws, these are going to be discounted significantly; and I think there’s great value if people can get away from perfection to look upon the foal and yearling more as an athlete with slight imperfections but at the same time, an athlete.

“I think for that reason trainers probably make the best buyers because they’ve seen it all, whereas often, agents are under pressure to buy the horse that ticks all the boxes.”

Fashion also applies to stallions and again, Cantillon is imaginative when it comes to where he sends his mares. He has said previously that he likes to go against the tide when selecting stallions.

“I like to breed to middle-distance horses. Last year, I bred five mares to Australia. I think he’s a very good stallion. He can get you a two-year-old, he can get you a good three-year-old, he can get you a horse you can sell to Australia for a lot of money if it shows some form. The demand for middle-distance horses is enormous and very lucrative.

“The only time I would be breeding to ‘expensive stallions’ would be a foal share. I wouldn’t be putting more than 30 or 40 grand into any mare, barring we owned a nomination. I do invest in a lot of stallion shares, and to a large extent, that dictates what my mare is going to.

“I think it’s a great business move. It’s not without risk, but you can buy a stallion share; and in most cases, you’ll get most of your money back within three or four years. And if it hits, you’ll get many multiples of it. So, I think, if you’re in the industry, you have a nucleus of mares that you can use these nominations on, it makes huge sense economically to invest in stallion shares.”

He sees the economics of horse breeding as being cyclical and thus predicts a significant downturn in two or three years, with the thoroughbred industry tending to “have a significant correction” within a couple of years of a societal recession.

There is no hint of doom in these utterances, given that he has always cut his cloth to measure, and he expects any shrewd operator to insulate themselves in preparation for what’s down the tracks. Indeed while he has expressed concern for the smaller breeders in the past, he believes the environment is more conducive to them getting a positive return for their investment now.

“I think it’s a bit healthier than it was. The top end was very lucrative and is still very lucrative, but maybe there aren’t as many players at the very top end where there’s a lot of players in the middle tier now.

“I think that ITM and the sales companies in Ireland have done a great job in attracting American buyers. There was a significant increase in yearlings going to America from the Orby Sale last year. That’s a tremendous result. To some extent, the American market is replacing the Maktoum market in Ireland. And when you look at history, you always see that major players come and go; but the industry always survives, and I think now the American market is going to get better and better.

“There’s a couple of factors there. The injuries in turf racing are less, the number of participants in turf races are more, and that’s good from a gambling point of view. And the fact we’ve sent a lot of horses over to America now, they’re acting as advertisements for the next bunch, and they’re doing exceptionally well. So as night follows day, I think that at the upcoming yearling sales, the American influence will be huge.

“I think Charles O’Neill (ITM CEO) has done an outstanding job. To see him in action internationally is a joy to behold. That’s a role that takes a long time to get people’s trust. Our industry is based on trust, but he has it now; and a lot of markets have been opened up year-in, year-out by him visiting these places with his team. Over time there’ve been very lucrative transactions, especially for horses in training, as a result of that.”

Back at home the evolution continues, and Cantillon’s entrepreneurial son, Jack, has become a key part of a team in which manager Ian Thompson is also a vital cog.

“I think Jack is a good catalyst because he pushes you. A lot of the accolades have to go to him because I’d be at the sales sometimes and he’d be after buying a mare without me knowing. He’d never buy a mare I wouldn’t have bought myself, but he pushes the boat out more than I would and that keeps me on my toes.”

Among Cantillon Jnr’s interests is Syndicates.Racing, which focuses on the fractional ownership model and has been a resounding success on both codes in a very short span of time. The founder’s proud parents have shared the journey, and Dermot emphasises the importance placed on having a positive race-day experience. This is a central tenet of all the improvements that have taken place at Naas during his tenure.

“In terms of building the new stand, the whole concept of it was to bring the horse into the main focus. You look to your right, and you have the horses in the parade ring along with the actors—the jockeys, the trainers—you have that whole environment there. Then you look to the left, and you see where the horses will be participating. So the whole philosophy of that stand was to bring the horse more into focus.”

Osborne calls Naas her husband’s “fifth child,” and it has certainly flourished in an atmosphere that promotes and encourages imaginative thinking. Former manager Tom Ryan oversaw much of the improvement, and Eamonn McEvoy continues in a similar vein.

“The philosophy is ‘never stop.’ What’s next? Eamonn has done a super job. He’s a very progressive, inclusive person. He tries to bring everybody with him.”

Rewards have come in the form of the upgrading of the Lawlor’s of Naas Novice Hurdle to Gr. 1 status and being asked to take up the slack during The Curragh’s redevelopment. But there is clear impatience about the difficulty in climbing further up the ladder. Not yet having a Gp. 1 race on the flat is especially annoying.

“My big frustration is that within the whole structure of Irish racing there’s no pathway in how you can get better. How do you go from being classed as a second-grade track to being one of the elite tracks? I’ve asked this question five years, six years now, and nobody has been able to tell me. How do we change it so that the 13 Gp. 1 races in Ireland are not divvied out every year to two tracks? Why can’t other tracks that have a good proposition get one of those races? Why don’t we challenge the status quo for the benefit of Irish racing? Nobody’s been able to tell me why not except that they won’t rock the boat.

“Convention is an easy way of management, but it’s not the progressive way.”

In any high performance network, the existence of a clear pathway provides an incentive for improvement and as a consequence, raises standards. Why do more than trouser the media money if it doesn’t matter what you do?

“That’s exactly it. That’s what we’ve been told for generations, more or less. There are little tweaks where they give progressive tracks like Naas additional fixtures; and also, we’ve been able to increase our black-type races. But at the same time, there’s a glass ceiling there, and we need to break that for the good of Irish racing. We need to be progressive. We’re not progressive. We just maintain the status quo.

“There’s two ways we can get a Gp. 1. The first is to have an existing Gp. 1 transferred from another racecourse. The other way would be one of our races, over time because of the ratings, would qualify as a Gp. 1. At this point in time, there are one or two races that we would think could be due to be upgraded, but it hasn’t happened yet and that’s frustrating.”

There are some “outside the box” plans that are being considered at the moment that include some potential ground-breaking global partnerships. Further enhancements for the course are also in the pipeline.

As for the racing product itself, he believes maintaining quality is critical.

“My view of Ireland: we’re like what the All Blacks tend to be in rugby. If a horse wins a good two-year-old race in Naas, then he’s marketable to the whole world as that’s as good as you can get in terms of a young horse and where he’s performing. I have a lot of sympathy that everybody gets a run because I have some bad horses myself that can’t get into races, but I think it’s very important that we maintain the brand.”

He believes that the betting tax should be limited to winnings for off-course bookies but be increased to three percent. This would lead to a likely increase in funding for racing, he argues. It would also go some way to arresting the decline of the on-course betting ring that used to be central to the race-day experience.

“We need to give an advantage to bookies on track. There needs to be something which makes you go racing if you want to bet and a differentiation between off-track and on-track in terms of the three per cent could be a big help.

“When I was on the board at Naas first around 25 years ago, a very good race meeting could turn over a million pounds on-track. Now we’re looking at 150 (thousand). There’s a crisis. We need to do something radical about the crisis. My solution would be to have no tax on-course and increase the tax off-course on winnings.”

This might also help increase attendances, which despite what some industry leaders suggest, has to be a cause for concern with racing’s supporters getting older by the year.

“We’re nearly totally dependent on media rights money to operate the racecourse. You could do a strength-and-weakness analysis, and a massive weakness is its dependence on the media rights. Because of the media rights, we’ve maybe neglected the attendance.

“We now have a new audience, which is the digital audience and… people don’t travel to race meetings like they used to, so the emphasis has to be on the local audience, and we have identified that at Naas. We have taken a number of steps, and we’re going to take more to be more and more part of the Naas community. If we’re going to get people back racing, we see our growth within Naas and its environs.”

It is a recipe that has worked for a number of regional venues but has not yet been utilised, successfully at least, by too many. And as Cantillon has already suggested, media rights income has removed much of the incentive to bother doing so.

That said, he understands the disappointment of some of the smaller racecourses that feel the distribution of the media rights income has been inequitable.

“Something like an extra seven-to-nine percent went back to central funds when the last agreement was made. I was in the room when the thing was voted on, and people were looking at how much extra they were getting; and they were so happy about how much extra they were getting, they didn’t really think of the implications of giving an extra seven or eight per cent to Horse Racing Ireland. Horse Racing Ireland said, ‘Oh that’ll all come back in grants.’ And as a totality, it came back in grants. But for certain racecourses, it didn’t come back proportionally because if a track couldn’t come up with 60 percent of the cost, they wouldn’t get the 40 percent grant; and I understand their frustration.”

The current deal concludes next year, and he yearns for a “unified approach” towards negotiating the next one. But whatever unfolds, positive or negative, Dermot Cantillon will be putting his best foot forward. He knows no other way.

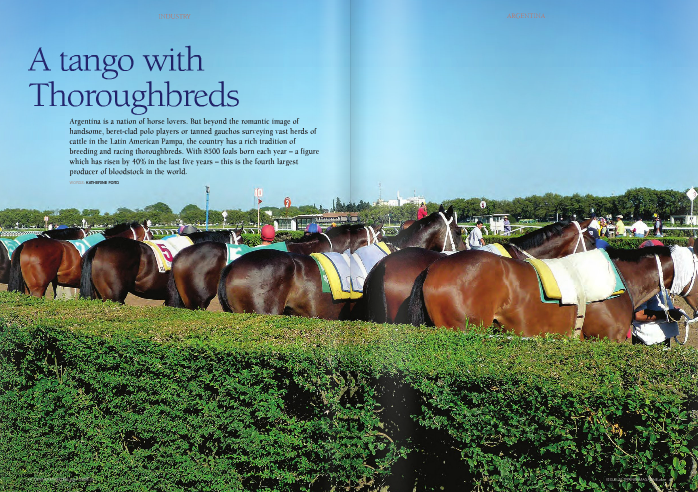

Racing in Argentina

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

(European Trainer - issue 35 - Autumn 2011)

Keeping it in the family - can a horse's family traits be used to a trainer's advantage?

It’s the same story at every dinner party, writes Frances J. Karon. A stranger will invariably ask, “What do you do?”, as if the response will somehow explain the very essence of one’s being. Similarly, the first question we have for the owner or trainer who tells us he has a nice yearling on the farm is, “What’s it by?”

The question is multifunctional. First, it enables us to gauge how seriously we can take this person. We will immediately discount the proud owner's opinion if the horse is by a bad stallion. Second, we make a generalisation based on the reply. If, for instance, the yearling's sire is Theatrical, we tell ourselves that it will obviously be a slow maturing turf horse who will want a route of ground.

Frances J Karon (European Trainer - issue 29 - Spring 2010)