Terry Finley

Words - Bill Heller

“If horse racing was just about dollars and cents, very few people would be in this game because it’s a terrible investment,” West Point Thoroughbreds founder and CEO Terry Finley said.

Yet he has been passionately invested in Thoroughbreds for much of his life, bringing in more than 2,000 new owners through racing partnerships in West Point Thoroughbreds’ first 31 years.

His father, a chemistry teacher who served in the U.S. Navy during World War II, found relief from the demands of his job and raising seven children in Levittown, Pennsylvania, at the racetrack—first as a $2 bettor and then by getting involved in a partnership.

Terry was 10 years old. “I saw how much fun they had,” Terry said. “It was teachers, plumbers, state workers and the like. I saw how much fun and enjoyment a partnership could be.”

His six older siblings didn’t take to racing, giving Terry additional, much-appreciated time with his father. They forged a special bond through their love of horses and horse racing, frequently doing double-headers: Thoroughbreds in the afternoon and harness-breds at night.

Most people would be surprised to learn that Terry has waged his private battle with stuttering much of his life. He rarely stutters now, if at all, but it was bad enough as a senior in high school that he thought it cost him his appointment to West Point. It did not.

Terry graduated from West Point in the star-studded Class of 1986, which featured many high-profile graduates including former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and four of Terry’s closest friends: Steve Cannon, the former CEO of Mercedes Benz who is now a co-owner of the Atlanta Falcons; Joe DePinto, the long-tenured CEO of 7-Eleven Inc.; David Urban, a CNN political commentator and a powerful member of the Republican Party and former FBI agent Jim Diorio.

Working together, those five friends created the Johnny Mac Soldiers Fund named for their classmate, Col. John M. McHugh, a fatal victim of a suicide bomber in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2010. The Fund helps the children and family of fallen soldiers with college costs. Through 2021, the Fund has awarded $25 million in scholarships to more than 3,500 college students all over the country.

After leaving the Army with the rank of Captain in November, 1994, Terry toiled in a job he hated, selling life insurance for a year and a half, before finally conceding to his life-long passion for horses.

Terry started West Point Thoroughbreds with a $6,500 claimer and now boasts 2017 Kentucky Derby winner Always Dreaming and Flightline, his undefeated four-year-old who is currently ranked fifth in the world after capturing the Gr. 1 Met Mile by six lengths.

Terry’s wife Debbie and their daughter Erin are key members of West Point Thoroughbreds’ corporate team.

Debbie and Terry met in pottery class in the 10th grade, started having dates at racetracks, and have been together ever since. Terry especially admires her tenacity as a mother, specifically helping their children, Erin and Ryan, secure the coaching they needed to pursue their passions. “She wouldn’t take `no’ for an answer,” Terry said proudly.

Erin didn’t let a horrific hand injury when she was four years old prevent her from continuing her riding lessons and becoming a top equestrian, frequently transitioning former West Point Thoroughbreds to a second career.

One can only imagine how difficult it was for Erin to deal with her injury growing up. Then one day at Saratoga, Terry ran into Steve Asmussen and noticed that Steve was also missing part of his thumb. Terry brought Erin to Steve, and they connected immediately when Steve reached out his damaged hand. “There was this mutual feeling that we’re not the only people in the world that had this type of accident.” Erin said.

Erin’s younger brother, Ryan, an All-American and professional soccer player, graduated from the prestigious Wharton School and will begin a business career with a consulting firm in Dallas in October.

Terry has been West Point’s general, deploying his Thoroughbreds around North America to one of a dozen top trainers, forming strategic alliances and relying on key officers, especially his wife and daughter, to oversee his troops day-to-day. Having been exposed to breakthrough technology in the Army, Terry has been ahead of the curve ever since, reflected in West Point’s website, television ads and customer service.

“He’s worked very hard at it,” his Kentucky-based trainer and buddy Dale Romans said. “I watched it from its infancy—Terry was smart enough to use the Internet and social media. I think he was the first one. He was very ahead of the curve. “

Along the way, West Point Thoroughbreds has taken care of its Thoroughbreds when their racing days were over, through its Congie DeVito Black and Gold Fund. Congie didn’t let his brittle bone disease prevent him from becoming Terry’s first employee after nagging him for months. Congie pioneered West Point’s technology—cutting-edge material at the time. “He was very valuable,” Terry said. “He was everything to our entire team.” Terry treated him accordingly, surprising Congie with an electric wheelchair and customized van that gave him mobility he’d never had his entire life. “It was the first time he could control his direction,” Terry said. “He did figure 8’s over and over. I’ve never seen a person happier or more content. He always wanted to run. This was the closest he could come. It was one of the proudest moments of my life.”

When Congie died in 2011 at the age of 35, he donated his two kidneys, saving two other lives. “The kidneys were his gift out the door,” his mother, Roberta, said. “He was the one who thought of it.”

While trying his best to avoid the spotlight, Terry has quietly become an industry leader. “Terry’s a straight-forward guy, very honest and cares about the sport,” former NFL linebacker Robert “Stonewall” Jackson, a partner on Always Dreaming, said. “He wants to do the right thing for the industry.”

He does so quietly. “It’s pretty remarkable,” his son Ryan said. “Other people—you can’t get to shut up. That’s something I learned from my dad: being humble.”

Erin calls her father “the definition of the American dream: serving your country and taking a risk. I am proud of him for not giving up with two kids and not a lot of financial backing, and grinding it out.”

Terry said, “It’s a labor of love. I get to live my dream: to win races.”

Advocating for Humane Education - the work being done to educate youngsters in equine welfare

Words - Bill Heller

How do you change culture? How do you ensure horses’ welfare? “Education is the answer,” Equine Advocates’ founder Susan Wagner said. “To me, it’s the only thing that changes the picture.”

She knows quite a bit about change. When Secretariat’s 1973 Triple Crown chase drew her to the racetrack for the first time, she witnessed his 31-length victory in the 1973 Belmont Stakes and was so dazzled that she quit her job and got a new one as a hotwalker on the backstretch the very next day. A myriad of jobs followed: working at Sagamore Farms in Maryland; writing for the Horsemen’s Journal; doing radio and TV work for the New York Racing Association and for Teletrack off-track betting in New Haven, Connecticut; and becoming the first female jockey agent in New York, representing George Martens, who won the 1981 Belmont Stakes on Summing to deny Pleasant Colony the Triple Crown. She then worked for New York Zoological Society and for Friends of Animals.

When she learned of horse slaughter in the United States, she and her sister Karen began Equine Advocates (EA) in 1996. They opened the Equine Advocate Farm and Sanctuary near Chatham, New York—40 miles southeast of Saratoga Springs—in late 2004. EA currently has 82 residents, including 19 Thoroughbreds. The newest horse, a wild Mustang mare named Onaqui, arrived from Utah on June 4.

In 2006, with the considerable help of longtime supporter and Thoroughbred owner and breeder Jeffrey Tucker, EA constructed a humane education center on the 140-acre farm to teach kids, preschool through college, about the humane treatment of horses. She was stunned two years later to learn that New York State has a law mandating humane education courses be taught at elementary schools. Section 809 of New York State Education Law mandates every elementary school in the state teach “the humane treatment and protection of animals and the importance of the part they play in the economy of nature as well as the necessity of controlling the proliferation of animals which are subsequently abandoned and caused to suffer extreme cruelty.” The law has been on the books since 1947, yet very few schools even know about it today.

Fifty-five years after the law was passed, the New York State Bar Association created the Committee on Animals and the Law to focus on legal issues regarding the interests of animals and to serve as a legal resource for humane-related issues pertaining to animals and “make a difference for both animals and people.”

Just like that law, few people are aware of that committee.

But at least New York State has a humane education mandate. Only eight of the other 49 states do: California, Florida, Illinois, Maine, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington.

“If any state should offer humane education, Kentucky immediately comes to mind since the breeding of horses for racing is what that state is most famous for,” Wagner said.

“There’s been a law since 1947, but it hasn’t been implemented,” retired Brooklyn elementary school teacher Sheila Schwartz said. “There’s no one around to see that it’s being done.”

She said she was “shocked” when she learned about the state law from the ASPCA in 1980. She began teaching it immediately and continued to do so until she retired in 2014. She created a humane education curriculum in 1985, and served as the chairman of the United Federation of Teachers Humane Education program from 1989 through 2014. “We were a support group,” she said. “Most of the teachers didn’t want to start a program.”

Asked to guess what percentage of schools have programs now, she replied, “I’d be surprised it is more than two to five percent.”

PETA noted: “Under New York State’s current education laws, elementary schools are required to provide instruction in the humane treatment and protection of animals. Unfortunately, many educators are not even aware of this requirement, and compliance is inconsistent.”

Teachers that do want to start humane education courses have a valuable resource in Humane Education Advocates Reaching Teachers (H.E.A.R.T), which offers full-service humane education programs in New York City, Chicago and Indianapolis and is accessible online. Its mission is “to develop a generation of compassionate youth who create positive change for animals, people and the natural world.”

What have all these kids who didn’t have humane education classes been missing? “Humane education gives them another way to view animals,” Schwartz said. “I think it makes them empathetic to animals and to each other. When I did the program, we would have them role playing. What are the alternatives?”

Susan Wagner has made a career of finding alternatives for horses. Yet she is realistic: “We can’t rescue every horse. So the best thing we can do is teach young people the tools to rescue them on their own in addition to being able to report animal abuse to the authorities. One of our main issues is to eliminate horses being treated poorly.”

Yet she and Michele Jacobs, the humane education teacher she hired last November, do not indoctrinate their students. “We don’t tell these kids what they should think,” Wagner said. “We show photos of a horse pulling a carriage in a busy city and a horse in a pasture pulling a carriage in a field. We ask the kids, ``What do you see? What do you feel?’ Then we get them to talk about horses. We tell them the different types of horses and what they are used for. There are ways to handle a horse properly. We’re very careful not to tell them what is right or what is wrong. They look at the pictures and they decide.”

Then they get to tour Susan’s farm. Horses meant to be slaughtered and/or have suffered abuse are now living like kings and queens in oversized paddocks, receiving excellent care and huge doses of love and carrots from a steady stream of visitors. Each horse’s story is posted just outside their paddock. They come to Susan when she calls their names. The bond she enjoys with them is obvious.

In 2019, the last full year of activity before the two-year pandemic, more than 800 students from nearby schools enjoyed the EA’s classes and tours. “It’s great for these kids,” Wagner said. “They love it. Some bring their parents back on open-house days.”

Michele, who began riding lessons when she was four, said. “It’s wonderful working here. I had teaching jobs all over the area, and I’ve always wanted a job working with horses.” Now she’s doing both.

She, too, was unaware of the state law: “I did not know about it. I don’t know why schools aren’t doing programs.”

Her programs at EA are geared to “inspire a new love of equines by thinking for themselves,” Michele said. “We talk about taking care of the horses. The younger ones’ reactions are curiosity. They want to know more about the animal. I had third and fifth grade students last week,” Michele said. ”They all sat down right away. They were very interested. They asked very intelligent questions. Even the third-graders were all over about horses having feelings. Their faces lit up. Another time, we had a three-year-old with one of the horses. It was her first time seeing a horse—a huge animal. The way she looked at him and touched him was beautiful.”

Michele’s three kids, 11-year-old Benjamin, 13-year-old Matthew and 16-year-old Caleb, have all been to Susan’s farm. “I’m very passionate about horses, seeing their expressions,” Benjamin said. “I like petting them. I want to help my mom with humane education. It’s definitely not right to treat horses badly. A lot of other animals, too. I want to learn about it.”

Matthew, who helps his mom take care of their own horse, said, “I just think they’re really cool animals. I think it’s very important because if you treat them the wrong way, you’re not going to live a happy life. I believe the animals have feelings, too.”

Caleb, their 16-year-old brother, has done a 10-hour volunteering stint at EA and plans on doing it again as a part of his school’s mandated policy of volunteer work. “I think the farm is really beautiful,” he said. “I know they treat their horses and other animals very well. I think what they are doing is excellent.”

Other kids of Caleb's age are happy participants at EA, too. Danielle Melino, who lives in Austerlitz, 15 minutes from EA, is a high school agriculture teacher at Housatonic Valley High School in Connecticut (EA is close to the New York-Connecticut state line). “We were the first post-COVID class to visit the farm,” she said. “It was probably the best field trip I’ve taken with my kids in years. We heard from Michele, Susan and volunteers. My students were blown away. They learned about a lot of topics: PMU (pregnant mares’ urine used to treat menopause), wild Mustangs, horse slaughter, carriage horses and camp horses. We learned about the history of the organization. I always tell my students these horses couldn’t ask for a better setting and better care on these beautiful grounds.”

She was so impressed with EA’s program that she reached out to another high school who also visited the farm, and also brought her 4-H class there. “I think humane education should be in every school,” Danielle said.

Daniela Caschera teaches preschool for three- and four-year-olds kids at Albany Academy, where Michele had taught. Her kids did a zoom with Michele. “She had left a bucket of items before we did the zoom,” Caschera said. “We guessed what they might be used for. Then, when she zoomed, she talked about those items: a horseshoe, some food, a brush, a file for teeth.

“They were so excited. One of my students, Leon Carey, then visited the farm with his parents. He loves animals. His father is a vet. His grandfather has a reindeer farm in Corning.”

Daniela was appreciative of having a zoom with Michele available during the pandemic: “With COVID, it was a way to introduce something new to the kids. My kids were very engaged, for three- and four-year-olds. They asked a lot of questions. After that, Michele gave us part of a tour.”

One moment stood out for Daniela: “We were talking about horses sleeping standing up. One of my little girls asked why. She’s the youngest person in my class. And she told her mom why horses sleep standing up. It stuck.”

Daniela intends to spend a whole week next year focused on horses as part of her curriculum.

Ray Whelihan, an associate professor at the State University of New York – Cobleskill, teaches an animal science class. He’s been visiting Susan’s farm for a decade. “Susan is a key part of the course,” he said. “She zoomed during COVID. It is such a professional organization over there. She gives extraordinary care.”

Susan has been working with Ray to create an individual course focusing solely on horses and/or a course of equine ethics.

“We desperately need humane education because kids are the future horse caregivers in America,” Wagner said. “I think every state should have humane education because every state has horses. For states with major horse racing and breeding, humane education should be compulsory because there are so many more horses bred. It’s important to make sure that every horse bred to race, whether or not he races, has a soft landing. Humane euthanasia should be considered a last resource to make sure the horses don’t fall through the cracks and end up being slaughtered.”

Classes and tours are just part of EA’s humane education program. Its Kid’s Corner is part of its Fun From Home program. There are equine-themed puzzles, quizzes, mazes and games, and video tours of the farm.

Brand new are the Equine Readers Club, offered online, once a month on Saturdays at noon, which are available on Facebook and YouTube; and “Live at Lunchtime” on Wednesdays is also available on those two platforms.

Following a two-year absence during the pandemic, EA scheduled seven open houses in 2022. The first was on May 14 and the last will be on November 5.

EA plans to expand its humane education program, hoping to reach as many children as possible. “I think it’s something that people don’t know about—how bad horses can be treated and how bad they are treated,” Caleb Jacobs said. “They should be treated like a dog and a cat. I think more people should know about it.”

#Soundbites - How are you complying with HISA regulations, and what additional steps are you taking to be compliant?

Words - Bill Heller

Michael Matz

I don’t think we have any choice. It is what it is, and you have to do it. It’s extra work, but it makes a fair playing field. This is what we have to do. I’m sure there are a lot of glitches that will have to be worked out. We just have to comply. I hope it makes a big difference. With the bunch of people caught (cheating), it should have been done a long time ago.

Richard Mandela

I’m lucky I’ve got my son helping. He showed me yesterday what we will be doing: a lot of recording information—we’re already doing at Santa Anita, ever since a couple years ago when we had problems with horses breaking down. It’s a great improvement, but it involves a lot of recording, inspections, checking, double checking, triple checking. It’s a pain in the neck, but it’s working.

Dale Romans

I’m going to hire a person to do all the HISA stuff. I’m going to put him on staff. I can’t do it myself. I’m going to have an open mind about HISA, but I think there’s going to be some unnecessary repetitive work. They’ll have to figure that out.

Bruce Levine

Bruce Levine

I haven’t registered yet (as of June 9). I’m going to look at it next week. My wife will do that for me. I’m all for uniform rules, but some of the smaller tracks may have a problem. It’d be nice to have uniform rules. I just don’t know how much horse knowledge they have. They should have had people on the backstretch asking questions.

Joe Sharp

Basically, it’s been a learning process for everybody. We’re trying to follow the guidelines that they’re giving us. It seems all the kinks haven’t been worked out yet. We’re waiting for changes in a couple of things. We’re registered and trying to sort through what they’re asking. There’s a little lack of clarity in some areas. I think we’re all trying to do the right thing.

Mike Stidham

First of all, I’m complying by just filling out the forms for myself and my horses. It’s quite a bit of data and a lot of paperwork. Everything they’re asking trainers to do has to be documented—what we did, what the vets did. I think there’s a redundancy. Whether or not this is the answer to solve many of the problems of the industry remains to be seen. We’re all going to find out after a period of time.

Wayne Catalano

I don’t know what to think, to tell you the truth. We’ll do whatever we have to do. I don’t know what difference it’s going to make. People can get around a lot of things.

Pat Kelly

I don’t think we need it. The little guys don’t need it. I only have two horses. We’ve already done a lot of this with the National THA (National Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association). They want people to do all this, but there’s no funding for it. It’s another layer of government bureaucracy we don’t need. I just don’t see everyone doing this by July 1. They may have to push the date back. I’ll sign up if I have to.

Ron Ellis

It’s not a great thing when government gets involved. It seems like a lot of unnecessary red tape. My owners are grumbling. They all have to do paperwork. We’ll see how it works out.

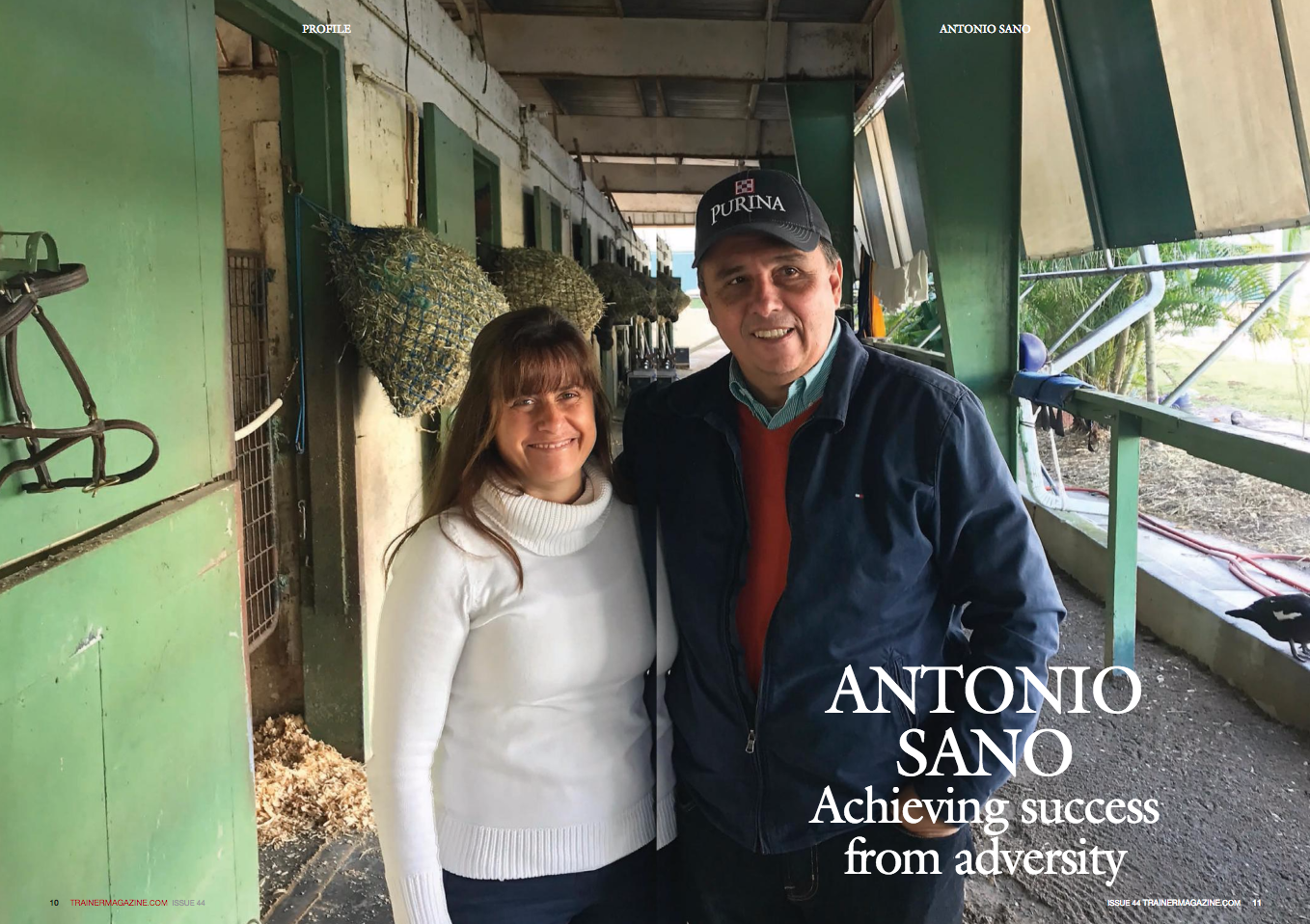

Antonio Sano trainer of Preakness contender - Simplification

This article was first published ahead of the 2017 Kentucky Derby - when Calder was still open for training.

We’re republishing it ahead of the 2022 Preakness Stakes - where Sano will start Simplification for owner Tami Bobo.

————————————————————————————————-

Antonio Sano is an early riser and according to his wife Maria Christina, not the greatest of sleepers in any instance. Up at 3:50 every morning come rain or shine, Sano can be found splitting time between his barns at Calder and Gulfstream Park. Between the two locations, he’s got roughly 70 horses in his care.

Assistant trainer Jesus “Chino” Prada

The two- and three-year-old are based at Calder, and the older horses are some 10 miles away at Gulfstream. “I like the track [at Calder] for the babies. It’s a good track, deep sand, and when it rains it drains, while over at the other place, it can take two days to clear.” Assistant trainer Jesus “Chino” Prada, who has been an integral member of the team since Sano started training in the U.S., chips in: “Gulfstream is great for racing, but here is the best for training.”

Sano might not yet be a household name across North America, but in his native Venezuela, the man’s a legend. He trained no less than 3,338 winners on his home soil, and it was only thanks to a kidnapping in 2009 that lasted longer than a month that he quit training in the country. The kidnapping -- his second -- resulted in the father-of-three doing what was best for his family, which was to remove them from the danger that his success was creating.

Sano is a third-generation trainer. “My father, grandfather, and uncle all worked with horses,” he recounts. “My father right now is 88 years old. He arrived from Italy when he was just 16 and was working with horses. They came from Sicily. In fact, my whole family is from there, including my wife!”

After graduating from college with a degree in engineering, the magnetic pull to the racetrack was too great, and Sano went to work as an assistant trainer Julio Ayala to enhance what knowledge and skills had been passed down to him from his father and grandfather.

Eventually (March, 1988) setting up on his own, Sano ended up training in Venezuela for 23 years, earning the trainers’ championship title 19 times and winning an average of 150 races annually, with three year-end win tallies in excess of 200. That’s no mean feat when you consider that racing only takes place twice a week in the major city of Valencia, where Sano was based.

In Venezuela, according to Sano, the pedigrees of the horses he trained were a little different than what he works with in the U.S., and so was the daily training regime. “I had 160 horses in my barn and worked the horses in four groups. Riders here take the horses to the track every 45 minutes and come back. There 4 sets of 40 horses each. Every rider work on 2 horses per set. I had the privilege to count with 20 riders at that time. We would take them all to the track at 6 A.M. At 6:45 A.M., the second set would be ready, the third by 7:30 A.M., and the last before 8:30 A.M.”

After first going from Venezuela to Italy, Sano and his family moved to the U.S. in March of 2010. They had visited the country before without spending any time at the racetrack, preferring the great vacationing opportunities that Florida offers with a young family in tow.

Well known for his training of staying types, Sano found the transition to training the speed-bred horses of the U.S. “Each horse is different, but I’ve learned more from others around me here in the U.S. than I ever learned in Venezuela,” he says -- modest words, perhaps, for a trainer who is a master of his game. “But my focus is always on the way the horses finish.”

Prada has been a friend of Sano’s for over 40 years. They attended trainer school together, along with Enrique Torres.

Their teaming up in Florida may never have happened had Sano decided to move to Italy after the kidnapping. “Italy has beautiful people and great food, but the racing wasn’t for me. So I went to Florida and met Mike Antifantis (the racing secretary at Calder at the time), who gave me a couple of stalls. I then had to go back to Venezuela and close shop, giving all my horses away.”

March 22, 2010, was an important date in Sano’s and Prada’s lives. It marked the start of a new chapter, when they claimed their first horse for their fledgling operation. The numbers quickly grew from there. “Two horses became four, and quickly we had 10,” recounts Prada.

The stable ended its first season with 37 winners, including two in stakes races. Knowing very few people or being known to few was probably a good thing for Sano as he and Prada quietly went about building their business. And where resentment for the new man in town could have quickly grown, friendships flourished with other trainers. “They treated me well and with respect,” says Sano.

With a successful formula in place, Sano’s stable was able to gradually improve the quality of stock. Still, his patronage remains primarily from Venezuelan or other Latin American ownership interests; he hasn’t really caught on with American owners.

In 2004, Sano started to shift his focus away from claiming horses to buying yearlings, while still using the claiming philosophy of trading up purchases. This time last year, Sano had high hopes for a then-unraced Broken Vow filly named Amapola, who he had bought as a yearling for $25,000. Amapola crossed the wire first by nearly 10 lengths in her May, 2016, debut in track record time for four-and-a-half furlongs at Gulfstream, only to lose the race in the stewards room for drifting in at the start. She turned a lot of heads that day, and Sano parted with her for a substantial profit. “I sold her for the money,” he says.

As with most buyers at sales, pedigree and conformation are at the top of Sano’s list when studying a catalogue page, but for him the stride of the individual and the horse’s eye are the main factors to determine if he is going to raise his hand in the ring -- should the price fall in his preferred buying range of $5,000 to $50,000.

In 2015, Sano made a number of purchases at yearling sales, and came home from the Keeneland September sale with a good-looking son of first crop sire and Florida Derby winner Dialed In.

The sale of that colt, from the consignment of Jim and Pam Robinson’s Brandywine Farm, must have been a rather bittersweet moment for breeders Brandywine and Stephen Upchurch. The chestnut’s dam Unbridled Rage had died about a week and a half after he was born, and the newly orphaned foal was bottle-fed until a foster mare could be found.

Sano with Gunnevera

That colt, for which Sano had the winning bid at $16,000, was, of course, Gunnevera. And thanks to him, if Dialed In hadn’t already been a particular favorite of Sano’s, he certainly would be now.

After the sale at Keeneland, Gunnevera, along with the other Sano purchases, was sent to Classic Mile Park in Ocala, where he was broken by Julio Rada a classmate of Sano and Prada’s at the Venezuelan training school in 1988.

Gunnevera was showing potential at Classic Mile and by the time of his arrival at Calder, his reputation was growing. However, the faith shown in him by those who knew him best wasn’t being shared by everyone: the first-time owner who Sano had bought the horse for eventually got around to paying for the colt...but the check bounced.

The name “Gunnevera” has no real meaning. It’s a combination of place names and words favored by his ownership interests -- Jamie Diaz, originally from Spain but now in Miami; and Peacock Racing, a partnership of Venezuelans Guillermo Guerra and Guerra’s father-in-law Solomon Del-Valle, who ended up with the horse just six weeks before his first run.

Del-Valle’s friendship with Sano is deeper than most normal friendships, as it was he who helped Sano’s wife arrange and finance Sano’s release from his kidnappers. “I told him that we bought horses at the yearling sale and this was the best one, that I’m going to make him a champion.” Sano’s prophecy looks like it’s showing some promise, and Gunnevera’s success has gone someway toward repaying Del-Valle’s generosity to the Sano family over the years.

————————————————————————————————-

Fast forward to 2022 and Gunnevera stands as a stallion at Pleaseant Acres Stallions in Morriston, FL. He has earned his place in the stallion barn on the back of his race record - winning the Grade 2 Saratoga Special and the Grade 3 Delta Downs Jackpot at two. At three he won the Grade 2 Fountain of Youth, finished second in both the Grade 2 Holy Bull and the Grade 1 Travers and was a game third in the Grade 1 Florida Derby.

As a four year old he finished second in a pair of Grade 1’s - The Breeders’ Cup Classic and the Woodward Stakes and ran a gallant third in the Pegasus World Cup (Gr.1). At five, his third place finish in the Dubai World Cup (Gr.1) meant that he retired with earnings of over $5.5m and as such has become the highest ever earner to stand at stud in Florida.

Gunnevera was not his trainer’s first graded stakes winner; although none received anywhere near the level of acclaim as the son of Dialed In. Sano previously handled Devilish Lady, City of Weston, and Grand Tito to graded stakes wins.

Sano is the first to admit that nothing has compared to the Gunnevera success story and the national exposure he received. But how well does he react to the inevitable pressure? “I’ve never been in a situation like this before, but it’s a blessing,” he calmly says. For Maria Christina, it’s as if her husband’s life is going on just the same. “He never sleeps before any race, he’s always thinking about something.”

Come to think of it, Sano’s whole day and night seems to be taken up with work or thinking about horses. The work day often ends 16 hours after it began, giving Sano a little much-needed family time with his three children. His eldest son Alessandro is already following in the family business and now works as one of his father’s assistant trainers.

But what about time away from horses, does Sano take a vacation? “One week -- and I don’t relax,” he says. “He’s always on the phone to Chino and I say, ‘No phone, Tony, the horses won’t run faster with you not there,’” interjects Maria Christina.

“Twenty (five) years ago when Alessandro was born, I would never have thought that I would be where I am now,” says Sano.

“But Tony, you were scared to come here 20 years ago. There wasn't the opportunity we have here in Venezuela,” retorts Maria Christina.

So Venezuela’s loss is America’s gain, and this is one family truly living the American dream.

First published in North American Trainer issue 44 - May - July 2017

Buy this back issue here!

Brian Lynch - the Australian born trainer whose set to make a mark at Ellis Park this summer

By Ken Synder

“If you find something you love, you’ll never work a day in your life,” said trainer Brian Lynch. “I’ve been blessed to do a job that I have a passion for. I have fun with it.”

“Fun” is not a word often associated with training Thoroughbreds. The job, as everyone in racing knows and as Lynch noted, “is seven days a week, 365 days a year.” The word, however, crops up often for those who know Lynch.

“He’s fun to be around,” said Richard Budge, general manager at Margaux Farm, where many of Lynch’s horses have begun careers as yearlings.

Dermot Carty, a bloodstock agent who first met Lynch when he came to Canada in 2005, echoed Budge: “With Brian, he just makes it fun. He makes it enjoyable through the good times and the bad. He’s one of the few true characters in the business who actually puts enjoyment into horse racing.”

Greg Blasi, Churchill Downs outrider who knows Lynch away from the racetrack “cowboying” with him, (more on this later), expressed it most succinctly: “He’s a hoot.”

Of course, the most fun is trips to the winner’s circle, and Lynch has made plenty of those: 720 at press time and earnings just short of $47 million.

A native of Wagga Wagga in New South Wales, Australia, Lynch fits, perhaps, the profile of a stereotypical and classic “Aussie.”

“We have more of a laid-back attitude than Americans. It’s nothing to share a few beers with each other and have a good time…helps you make new friends, that’s for sure.”

What Lynch did before coming on the racetrack may explain also why racing is more fun to him than anything. He was a bull rider back home. In fact, he came to America in 1992 to join this country’s professional circuit with big purses after learning the trade locally. “They had a local rodeo back home, and it was a big thing. Not far from the racetrack was a horse trader who had some bucking horses and some bucking bulls; and I used to hang around his place a lot. That’s where I got the taste for jumping on bulls.”

The racetrack Lynch mentioned is an unusual triangular racecourse that was across the road from his home and where he got his start, filling water buckets and learning to ride as a boy. “I could ride from a young age. It wasn’t long before I graduated to galloping horses.

“I was always a little bit too big to be a jockey. I sort of found a lot of work helping on the wilder horses.” Apparently, it was experience sufficient to prepare him for something bigger and more dangerous…with horns.

Thoroughbreds sidetracked Lynch when he came to Southern California and a small farm near the border with Mexico. “There was a little Thoroughbred farm called Suncoast Thoroughbreds. I got a job breaking colts for them, and it wasn’t far from San Luis Rey.”

Lynch said he “annoyed” the stewards there till they gave him a trainer’s license. His start was with two horses at San Luis Rey.

That led to training for the Mabee family’s Golden Eagle Farm in Ramona in San Diego County.

“I kicked around California for a lot of years just with small numbers, just scratching out a living—selling, and running horses, and flipping horses. I was bringing some from Australia and moving them.”

His big break was training at Santa Anita and Del Mar where he met some important influences. “Most say they admire the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. For me, it’s Ron McAnally, Jack Van Berg, and Bobby Frankel,” he said with a laugh.

When Frankel learned the Mabee family was going to downsize their Thoroughbred operation, he approached Lynch about joining his stable as an assistant. “He was starting to get more two-year-olds than he’d ever had. That’s when Chad [Brown] and I teamed up with horses for Bobby. Chad went to California, and I went to South Florida and Palm Meadows in the first year that it opened,” said Lynch.

“Bobby certainly wasn’t a textbook teacher,” Lynch said of the legendary New York trainer who died in 2009. “He wasn’t going to walk you through everything. He was a guy that if you were around him enough and you didn’t absorb anything from him or learn anything from him, then shame on you.”

Frankel, not known publicly as being chatty, was half of a truly odd couple with the amiable Aussie. Not just the experience, but the friendship is treasured by Lynch. “He had a heart of gold. He was a great guy to train horses for and just a wonderful human being.”

Lynch’s big break came when he moved to Canada to manage Frankel’s division at Woodbine in 2005. In 2006 he went out on his own, eventually becoming a private trainer for Frank Stronach.

Canada was very much to his liking; in both 2006 and 2007, his earnings topped $1 million before jumping to over $3 million in 2008. That year began his string of consecutive top 100 earning trainers in North America that continued through last year.

He is quick to credit owners for his success and consistency: “I’ve been very blessed to have long-term owners who like to play the game and who have always tried to work on finding the better horses. Fortunately enough, if you look back over the list, there’s been quite a few of them.”

Quite a few indeed. Lynch trained Clearly Now, who set the Belmont record for seven furlongs (1:19.96) in that track’s 2014 Sprint Championship, earning an Equibase speed figure of 122. (To give you an idea of how phenomenal the performance was, the next year’s Sprint Championship winner won in 1:22.57.) Other top horses include Grand Arch, owned by Jim and Susan Hill of Margaux Farm and winner of the Gr. 1 Shadwell Turf Mile Stakes at Keeneland in 2015; Oscar Performance, winner of the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf at Santa Anita in 2016; and Heart to Heart, winner of two consecutive back-to-back Gr. 1 stakes in 2018 at Keeneland and Gulfstream Park. Most notable outside the U.S. was a win in Canada’s 2015 Queen’s Plate Stakes with Shaman Ghost.

While many trainers get labels for being good with two-year-olds, sprinters, etc., there is an enviable trademark for Lynch’s horses: long careers. “I’ve raced two- and three-year-olds and still have them around running Gr. 1’s and winning at six or seven.” Grand Arch raced till the ripe old age of seven and in stakes company, finishing his career in the Forbidden Apple Stakes at Belmont. “Keep them in good form and you’ll have them still around when they’re older,” said Lynch who also points to “patient owners” like the Hills, willing to give their horses a break as a necessary ingredient in managing racing careers.

If there is a label, Lynch is unaware of it. When it was pointed out that in the past five years he had started more horses on the turf than on dirt, his response elicited another Lynch trademark: humor. “Probably because they were too slow for the dirt.

“I guess I primarily grew up training horses and riding horses to run on the turf down there [Australia], so I probably am influenced to run ‘em on the grass. I’m certainly not frightened by the dirt, by any means, but somehow, I ended up trying them on the grass. If they run well there, I’ll keep them on that surface.”

Brian Lynch with mentor D. Wayne Lucas

As intent as he is on enjoying himself and bringing enjoyment to others in the game, he is “no-nonsense” as a trainer—a euphemism not used by Carty to describe Lynch. “He can figure out in a very short period of time if a horse has or does not have any talent. He’s not one of those bull***t trainers who tells people that, ‘yes, yes, it’s going to get better’ and in his heart and soul, he knows it’s just for a day rate. He’s not interested in the day rate. He’s interested in developing and making great racehorses.”

Asked about his success and consistency, Lynch responded with characteristic modesty and self-deprecation: “One thing I’ve learned about training horses over the years is I’ve gotten very good at delivering bad news. That’s what you seem to do a lot.”

Unlike many high-profile trainers with multiple divisions and large strings of horses who are more business people than trainers, Lynch’s focus is the barn first, and then business. “It’s switch on, switch off,” said Carty. “Clients will feel good and enjoy themselves at the races with Lynch. But when he goes back to that barn and those horses, he switches to Brian Lynch who looks after the horses, making sure they’re ok.

“He’s there first thing in the morning, and following the races, he goes over and checks every stall and goes through it. He’s not one who would just leave it to the help,” said Carty.

Richard Budge offered another perspective on Lynch. “I would say he’s unique in the fact he’s willing to roll the dice in a stakes race with a horse that may be an outsider.”

Brian Lynch with groom Juan Garcia

A case in point was a recent start by Phantom Currency (yet another Hills-owned horse) in the Gr. 3 Kitten’s Joy Appleton Stakes at Gulfstream in April. The horse was coming off a 13-month layoff. While most trainers may have looked for an allowance race tune-up, Lynch went for the gold. The horse won, earning a very impressive 114 Equibase speed figure.

“If a horse is training well, he’ll ask, ‘Why not? Let’s give it a shot,’” added Budge.

“That would be a huge positive. We can be a little tentative about where to place them or put them. You never know if you could have run a stakes race when you run in an allowance.

That very question faces Lynch with his first potential Kentucky Derby starter, in Classic Causeway.

After two impressive wins—the first in the Gr. 3 Sam F. Davis Stakes in February and a month later in the Gr. 2 Lambholm South Tampa Bay Derby with identical and impressive Equibase speed figures of 104—the horse finished a mystifying last in the Florida Derby.

Classic Causeway, owned and bred by Clarke M. Cooper and Kentucky West Racing, is one of three foals from the final crop of Giant’s Causeway who died in 2018.

He made his debut at Saratoga last September and blew away the competition from gate to wire over seven furlongs, winning by six-and-a-half lengths. The horse entered the Derby picture with a third-place finish in the Gr. 1 Breeders’ Futurity in October at Keeneland and followed that with a second-place finish in the Gr. 2 Kentucky Jockey Club Stakes in November at Churchill Downs. His two wins at Tampa Bay Downs earned him qualifying points for one of the 20 spots in the gate the first Saturday in May.

Before the Florida Derby, Lynch had this to say about the son of the great Giant’s Causeway, known as the “Iron Horse” after winning five Gp. 1 races in just 11 weeks as a three-year-old. “You always hope that you come across one in your career that you can have a ‘kick at the can’ in the Derby, but fortunately this horse came into our stable, and he’s done everything we’ve asked of him. I think he’s just getting better, and we’re really excited to have him.”

louis rushlow

Whatever lies ahead, Lynch said he will “stop and smell the roses,” whether they’re draped across the withers of Classic Causeway at Churchill Downs or the figurative kind.

He embraces a positive attitude toward racing that most of us should emulate. “Racing is a game of ups and downs. You could be dodging missiles in Ukraine. You get over a loss, have a beer or soft drink, and move on.”

His idea of relaxation may be an indication of the kind of person Brian Lynch is. When Greg Blasi mentioned one day he and other outriders were going up to a farm east of Louisville to work cattle, the 57-year-old Lynch was quick to say to Blasi, “If you ever need some help, just let me know.”

He’s ridden with Blasi, and the others as many times as he’s had the opportunity, ever since. “He’s just a very good horseman, whether it’s on the back of a pony herding cows—just whatever,” said Blasi. “He used to gallop his own horses. He’s come up the hard way, and he tells stories about when he didn’t have a couple of nickels to rub together. Nothing was handed to him. I respect guys like that. There are a lot of people that didn’t have to struggle to get where they are.

“He’s also a lot of fun to be around.” Ah, there’s that word.

For a guy who’s ridden bucking broncos and bulls, you might expect a certain fearlessness. Not so: “I have one fear in life, and that is that there’s a good time going on somewhere and I’m not in the middle of it.”

Racehorse Bone Health: From a Nutritional Perspective

Strong, healthy bones are the foundation for racehorse soundness, but unfortunately skeletal injuries are an issue that every trainer will face. There are many factors involved in the production of strong bones; however, two key factors that we can influence are training and nutrition.

By Louise Jones

Every trainer knows how important exercise is to ‘condition’ the bones, and we are constantly striving to improve training programmes so that sufficient strain is applied to signal an increase in bone development, whilst not straining the bones to the point of fracture; this is a difficult balancing. Perhaps more fundamental to this is the role of diet in supporting bone density, strength and repair. Even minor nutrient deficiencies or imbalances can mean that the horse doesn’t receive the nutrients it requires for healthy bones and thus increases the risk of potential problems down the track.

Understanding how bone is formed and adapts in response to training, alongside the critical role optimal nutrition plays in these processes, can help to ensure skeletal soundness and minimise the risk of bone-related injuries.

Bone formation & remodelling

Bone formation occurs by a process of endochondral ossification; this is where soft cartilage cells are transformed into hard bone cells. Bone consists of three types of cells and an extracellular matrix. This extracellular matrix is made mainly from the protein collagen, which makes up to 30% of mature bone and is a key element in connective tissue and cartilage. The three types of cells in bone are:

Osteoblasts: These are the cells that lay down the extracellular matrix and are responsible for the growth and mineralisation/hardening of bone.

Osteoclasts: These cells are involved in the breakdown of bone, so that it can be replaced by new stronger bone.

Osteocytes: These cells work to maintain and strengthen when a bone requires modelling or remodelling.

Bone mineral content (BMC) is a measure of the amount of mineral in bone and is an accurate way of measuring the strength of a bone. Interestingly, about 70% of bone strength is due to its mineral content; calcium being the most notable and accounting for 35% of bone structure. A horse’s bones do not fully mature until they are about 5-6 years old. So, whilst a horse will have reached 94% of their mature height when they are a yearling, they will have only reached 76% of their total BMC.

Although it may seem like mature bone is inert, it is in fact a highly dynamic tissue, and BMC is constantly adapting in response to exercise and rest by a process called remodelling.zBone remodelling is a complex process involving several hormones and nutrients. Essentially when mature bone ages or is placed under stress, such as exercise, small amounts of damage occur. This results in the osteoclast cells removing the old or damaged bone tissue. In turn, this triggers osteoblasts and osteocytes to repair the bone by laying down collagen and minerals over the area, thus strengthening the bones. It’s estimated that 5% of the horse’s total bone mass is replaced (remodelled) each year. It should be noted that during the remodelling process, bone is in a weakened state. Therefore, if during this period, the load applied to the bones exceeds the rate at which they can adapt, injuries such as sore shins can occur.

Bone strength & exercise

When galloping, a horse places up to three times its body weight in force on the lower limbs. The more load or pressure put on a bone, the greater the bone remodelling that will need to take place. Ultimately, this will result in new, stronger bones being formed.

Studies have shown that correct exercise can increase bone density in the cannon bone, the knee and sesamoid bones; and this can help reduce the likelihood of skeletal injury. However, the intensity of training is key; low intensity exercise (trotting), whilst essential for muscle development, has been shown to only result in small change in cannon bone density. Whereas training at high speeds for a short amount of time (sprinting), rather than repetitive slow galloping, has shown to result in a significant increase in bone density. This is highlighted in a study using a treadmill where short periods of galloping at speeds over 27mph (43 km/hour) were associated with a 4-5% increase in the density of the cannon bone.

Whilst exercise clearly plays a pivotal role in bone density, doing too much too soon can be disastrous and result in issues such as:

Sore/buck shins: This is a common injury in young racehorses. It is caused by excessive pressure on the bones resulting in tiny fractures on the cannon bone, which may not have fully mineralised (strengthened and hardened). This results in the periosteum (a fibrous membrane of connective tissue covering the cannon bone) becoming inflamed.

Bone chips: Another common skeletal injury in racehorses, mostly seen in joints, particularly in the knee. This is when a tiny fracture occurs in the joint, weakening the bone and ultimately resulting in a ‘chip’ of the bone becoming separated.

When trying to maximise skeletal strength, periods of lower intensity exercise or rest are just as important as gallop work, as they give the bone a chance to remodel. However, prolonged rest will have a negative effect on skeletal health. Research has looked at the loss of BMC in the cannon bone when horses were placed on box-rest (with 30 minutes on the walker) and found overall BMC was reduced. Therefore, even horses returning to work after a short period of 1-2 weeks of box-rest could potentially have a significant decline in bone density and thus be at increased risk of skeletal injury once exercise recommences.

It’s also important to bear in mind that when a young horse starts training, it is normally coming from a 12–24-hour turnout. This is where the horse has the ability to gallop and play. However, once training begins, they are typically stabled from long hours with short intervals of low intensity training. Consequently, bone demineralisation can occur. In addition, during this early stage of training, bone will undergo a significant degree of remodelling in response to exercise. Initially this process makes the bone more porous and fragile before it regains its strength. As a result, research has shown that horses can have reduced bone density during the first few months of training, with bones being at their weakest and the horse more prone to issues such as sore shins between day 45–75 of training.

It should be noted that even when training is carried out slowly, conditions such as sore shins can still happen as bone remodelling occurs at different rates in every horse and is influenced by factors such as track surface and design. While there is some information on exercise and bone development from which to make inferences, a definitive answer as to the perfect amount of exercise to support optimal bone development has not yet been found.

Nutrition & bone health

Exercise is essential to bone health, but nutrition plays an equally important role. Bone is continuously being strengthened, repaired and replaced. And if we can aid bone remodelling with good nutrition, we can decrease the likelihood of skeletal injury. The essential nutrients for bone health are protein, minerals and vitamins, including calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), zinc (Zn) copper (Cu), vitamins A, D and K.

Protein: Collagen is a protein and forms the bony matrix on which minerals are deposited. Feeding sufficient high-quality protein, rich in essential amino acids such as lysine and methionine, is therefore a key factor in the development of strong healthy bones. When selecting an appropriate feed for horses in training, both the level and quality of the protein it provides should be carefully considered; not all protein is equal.

Calcium & Phosphorus: It is well documented that these essential minerals are the foundation of strong and healthy bones, making up 70% of the BMC. The ratio of calcium and phosphorus in the diet is also very important for bone mineralisation. This is because imbalances in the Ca:P ratio can result in the removal of calcium from the skeleton and may lead to bone demineralisation. The minimum Ca:P ratio in the diet should be 1.5:1, with the ideal ratio being at least 2:1 for young horses. It is important to note that adding other feedstuffs such as chaffs or cereals to the horse’s feed can alter the Ca:P ratio in the overall diet. For example, adding oats, which are high in phosphorus, will reduce the calcium to phosphorus ratio and this may adversely affect calcium absorption. On the other hand, including some alfalfa, which is high in calcium, can help to increase the Ca:P ratio if required.

Copper & Zinc: Copper is an important mineral for bone, joint and connective tissue development. Lysyl oxidase is an enzyme that requires copper. It is responsible for cross-linking of collagen, and therefore copper plays an important role in the formation of new bone which requires a collagen matrix. Similarly, zinc is integrally involved in cartilage turnover; and research has shown that horses supplemented with zinc, as part of a complete mineral package, have increased bone mineral density compared to horses fed an unsupplemented diet. Copper and zinc are frequently found to be low in forage and therefore must be provided in the form of a hard feed or supplement.

Vitamins: A number of vitamins play essential roles in skeletal health. For example, vitamin A is involved in the development of osteoblasts—the cells responsible for laying down new bone—whilst vitamin D is needed for calcium absorption. More recent research has also shown that feeding vitamin K improves the production of osteocalcin, the hormone responsible for facilitating bone metabolism and mineralisation. Furthermore, research in two-year-old thoroughbreds suggests that feeding vitamin K may help increase bone mineral density and thus potentially be beneficial for decreasing the incidence of sore shins. Although standard feed manufactures include vitamin A and D in their feeds, a few also now include vitamin K.

Supplementation for bone health

Young horses in training, those recovering from injury or returning to work following a rest will benefit from additional nutritional support targeted at maintaining improving bone health. In these situations, supplementing with elevated levels of calcium and phosphorus will help improve bone health. Look for a supplement containing collagen, which is rich in type I and II collagen, proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans—all of which aid the bone remodelling process and help to maintain bone health. Choosing a supplement that also contains chelated copper and zinc, as well as vitamins A and D, will also help support bone mineralisation.

In summary, skeletal injuries have a huge adverse effect on the racing industry and are a common cause of lost training days. Undoubtedly, adapting our training regimes, modifying our gallops and improving our management practices will all help to reduce the risk of bone-related injuries. Equally, the role of nutrition in bone health should not be overlooked. A balanced diet, rich in nutrients, minerals and vitamins, can contribute significantly to bone density and strength. Proper nutrition is an essential parameter of skeletal health, participating in both the prevention and treatment of bone diseases. To achieve a strong, sound skeleton, you must feed the bones.

The Importance of forage testing

Forage (hay/haylage) is an important source of nutrients for horses in training. However, the levels of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus and copper present can vary enormously and depend on factors such as the species of grass and the land on which it was grown. It is recommended that you regularly test the nutritional value of your forage. This will highlight any mineral excess/deficiencies and allow for the ratios of certain minerals such as calcium and phosphorus to be assessed. In most cases, any issues identified can be corrected through using an appropriate hard feed and/or supplement.

Marketing racing - the efforts being made by tracks across North America

By Ken Synder

At some point in time—70 years or so ago in the 1950s—the decision was made by the “powers that were” in horse racing to not broadcast races on the burgeoning medium of television. There was a fear that it would keep fans home watching racing on TV rather than at the racetrack. The decision, of course, backfired. On-track attendance diminished in a sport that had historically been part of a “Big Three,” which included baseball and boxing.

In one of those strange twists of history, the decision also succeeded many years later in driving the biggest part of racing’s fan base to… guess what? Television. Today, TV networks like TVG broadcast racing from around the country, and even the world, to viewers at home with Advance Deposit Wagering accounts.

Things, obviously, have changed and changed hugely. But some things haven’t. The following newspaper headline, provided by Aidan Butler, chief operating officer of 1/ST Racing and president of 1/ST Content, is as true then as it is now: “No young people come racing anymore.” When was it written? The 1930s.

Young people and equally, if not more importantly, new owners don’t “come racing anymore.”

Ironically, television is the lifeline for the sport and perhaps the “tip of the spear” for bringing in those missing young people and new owners.

In 2019, at one of the sport’s major venues, Santa Anita, there were 13 racing fatalities on the dirt surface. This may have been the nadir for horse racing, threatening the very existence of the sport in California with potential effects rippling to racetracks across America and those involved in breeding and sales in Kentucky and Florida. But in a state with the most virulent cancel culture, Santa Anita—specifically the Stronach Group and 1/ST Racing—“canceled the cancelers.” In 2020, there were zero racing fatalities on the dirt surface.

What do animal welfare and safety have to do with marketing? It’s elementary: Marketing begins with a product. “The best thing we’ve got is the horses above anything else,” said Butler.

“The world is changing. Do people want to be involved or watch a sport that involves animals? There’s not one group now that doesn’t have an outlook toward the animal welfare and the care of the animals to make it safer.”

He offers a brutal assessment of the past, which may account for racing’s journey to some kind of abyss in 2019. “We’ve inherited an old-fashioned model where maybe it [safety] once wasn’t the core focus.”

“The culture now in California, particularly at Santa Anita, is one that, if anything goes wrong, everybody is horrified. Everybody sees that there’s not going to be a future. For years, when something went wrong, it was an accepted thing.”

The safety of horse and rider is part of a big jigsaw puzzle, he said, but perhaps it is the most important piece in marketing a sport perceived negatively by many. He recalled a dinner in California with someone who visibly winced when informed Butler was part of the racing industry. “He said, ‘You’ve been having a lot of injured horses, right?’” Butler conceded that yes, that was the case in 2019 but then went through changes that produced dramatic improvements—most critically vet inspections during training hours—to get across that positive animal welfare, born out statistically at Santa Anita, has never been higher.

“In 30 minutes, he couldn’t wait to come out to the track,” said Butler, adding with a laugh, “It’s going to take a long time to go through everybody in California over dinner.”

Of course, that’s where marketing in the traditional sense takes over, but not all in the traditional mediums of radio, TV and newspaper. For younger potential fans, “the first touchpoint these days is digital,” said David Wilson 1/ST’s chief marketing officer. “It’s on the iPhone or smartphone. Having strong social media is really our opportunity to cultivate our community, connect with them and inspire them to come to our tracks.

“It’s about the convergence of sports, entertainment and technology.” Wilson believes the task is creating narratives and stories that will capture the imagination of potential younger fans who have had little or no exposure to horse racing.

Part of that too, according to Wilson, is marketing to younger fans in audiences not previously targeted. “We need to look at how we are addressing women in the sport. How are we addressing African-American and Latino communities? How are we making sure that any minorities have opportunities not only to work within our companies but to feel represented? We make very conscious efforts that if we want to be a modern company, we want to address all of our customers, and all of our customers are diverse. Our marketing and our social platforms and the inspiration between the sport and entertainment all need to reflect that.”

Traditional markets as well are being looked at in new ways. “Your owners bring other people. These are potentially new owners and it’s grassroots, but it is something that’s been overlooked.”

To show appreciation to owners, all 1/ST race tracks make “best turned-out” awards every day—something routine in the UK and Ireland but novel in the U.S., except for major race days. Champagne toasts after every win are also standard at tracks.

“It’s so difficult, especially during some of the big meets, to get a winner; and you have to try and bend over backward to show the owners that you are really thankful for their participation,” said Butler.

For bettors and others who love horses or simply want a day at the races, one task for racing marketers is how do you add to weekday attendance on, say, a Wednesday afternoon at Gulfstream Park in the blazing summer heat? “There is really no easy answer,” Butler admits, but there is effort. Gulfstream is attracting people to the track for business lunches with food and beverages on par with the best restaurants and a backdrop the restaurants, of course, can’t offer: horses.

Gulfstream is also exploring the engineering for lighting the racetrack for night racing, which should boost on-track attendance on those days that normally don’t draw a lot of fans while also beating the Florida heat.

1/ST is not the only racetrack seeking enhanced owner-engagement and new fans, especially in the wake of COVID-19. Some tracks are also doing things to combat unique obstacles.

Canada’s Woodbine Racetrack in Toronto—the premier racing venue in Canada—is challenged by a dearth of owners. “We don’t have tax benefits for owners like you get in the States,” said Martha Wakeley, who manages horsemen concierge services and is also manager of Racing Operations. The biggest hindrance, however, is a population base generally without a family background in racing unlike the U.S., where racing is bequeathed to succeeding generations in places like Kentucky.

COVID, oddly enough, offered Woodbine an opportunity to evaluate the owner experience. Because COVID allowed only owners on track during lockdowns, management was able to see and define needs in hospitality and customer service that had, perhaps, gone unnoticed before. Wakely called it a “silver lining” that came out of the pandemic. “We opened an exclusive lounge just for owners and trainers and their guests,” she said, noting that most trainers at Woodbine are also owners.

The goal with owners is to recognize their importance and to make them feel special. Part of that, too, is for guests of owners to see that their hosts and hostesses are very important to Woodbine. Wakely stated something that is obvious but still often overlooked: “Without the owners, we don’t have a job.”

The track has invested much time and travel in marketing to owners as well as everyday race fans. Hospitality teams from Woodbine have visited Santa Anita, Saratoga, Keeneland and Churchill Downs to study and replicate what works at U.S. tracks.

Woodbine may, however, exceed the U.S. customer experience with concierge services beyond the racetrack. “We have looked at groups coming in for stakes races and being available to book golf tee times and tickets to the theater,” said Wakely. “We want to be able to offer all that to make it a whole weekend experience.”

The experience at Keeneland Race Course in Lexington, Kentucky is well-known; it is the “Fenway Park” of American racing—the required destination for “racing as it was meant to be,” to quote a marketing theme from years back. It is arguably the most picturesque and bucolic in the world. It is also not lacking for patrons. In the last pre-COVID year, 2019, Keeneland’s daily attendance average was just over 15,000 for the spring/April meet and was slightly higher in the fall/October meet.

So what do you do when you don’t lack for owners and, most critically, racing fans? In the case of Keeneland, they have written the proverbial book on corporate sponsorships. Two sponsors, Toyota and Maker’s Mark bourbon, have surpassed 25 years with Keeneland. Two other sponsors—Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital and Darley—will reach the 20-year mark with Keeneland this year.

“Sponsorships are incredibly valuable to Keeneland, as they provide important funding for our racing purses, our investments in fan education, advancements in safety and integrity initiatives, philanthropic initiatives for our sport and the central Kentucky community…and the list goes on and on,” said Christa Marillia, Keeneland vice-president and chief marketing officer.

In Lexington, local horse farms like Claiborne Farm, Coolmore, and the aforementioned Darley also sponsor premier stakes races, essentially investing in their own industry. “They buy and sell horses at our auctions, compete on our racetrack, and understand and appreciate the full circle of Keeneland’s business model,” Marillia said.

NYRA & Fox Sports host and paddock analyst Maggue Wolfendale (L) with host and reporter Acacia Courtney (R)

In an irony of ironies, racing beyond Triple Crown races and the TVG network catering to ADW accountholders has made its way to national telecasts regularly. “America’s Day at the Races,” produced by NYRA and airing on Fox network channels FS1 and FS2, features live racing on Saturdays and Sundays. The impetus for NYRA was entry into the ADW market, a revenue stream already flowing for Twin Spires, Express Bet and TVG. “We really were playing catchup so we thought we needed a TV strategy,” said Tony Allevato, chief revenue officer for NYRA and president of NYRA Bets.

“Our original concept was we would pick up selected dates during the year and put them on Fox regional networks—Fox Sports West, Fox Sports Ohio. We put together a pilot and showed it to Fox. They loved it,” said Allevato. Instead of a regional strategy, however, the pilot spurred Fox to suggest a show on FS2, broadcasting nationally.

The first production was a daily show from Saratoga, two hours a day and produced by NYRA’s TV department with input from Fox that amounted to 80 hours the first year.

“We got a fantastic reaction from the industry,” said Allevato. Broadcast hours were added, and Fox acquired equity with NYRA, which gave the network a slice of the ADW wagering. “We’ve provided an extra revenue stream for the telecast. Not only is there the traditional advertising and sponsorship revenue, but you also have wagering dollars coming in; and it’s become a win-win for both of us. For Fox, they’re incentivized to give us the most distribution possible.”

Distribution included the recent Arkansas Derby, broadcast on FS1 as part of “America’s Day.” “We have a couple of shows that will be on Fox [the main network] this year, which will be over a million viewers for each one of those. That’s more eyeballs watching horse racing, more wagering, more account signups, more fans. It’s really almost like we’re creating a new ecosystem to help grow the sport,” said Allevato.

Growth is aimed at more than just ADW accounts, he added. “Even though the sport has really gone to online betting, our goal is to get people to come to the track. That’s our number-one goal. We believe once you come to the track, you will become a fan for life.”

“America’s Day” content is aimed at driving live attendance at racetracks. “The stories are all there: Within every race, there’s an owner, there’s a trainer, there’s a jockey, there’s a groom, there’s the pace of the race, there’s the favorite.”

NYRA doesn’t forget marketing to owners either, according to Allevato. “One of the rules for our show is we must interview one owner at a minimum, and that doesn’t mean just for a million-dollar race; it can be for a ten-thousand dollar race.

Allevato, too, points with pride to production values that rival, if not surpass, that of other sports. “When we’re covering a race in New York, we’ll have 35 cameras on a certain select day, compared to a college basketball game with seven cameras. That is a real big-time production.

NYRA & Fox Sports TV analysts Andy Serling (L) and Anthony Stabile (R)

“With the Arkansas Derby, we had three people at Aqueduct contributing remotely and six announcers at Oaklawn Park.

“We believe horse racing is our sport. We want people flipping through the channels, land on a Fox Sports 2 or FS1, see “America’s Day at the Races,” and go, ‘Wow, this is major league!’ We don’t ever want to come across as a second-tier product.”

Can all of this be “the start of something big,” to borrow from the song title? Combined with the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act potentially providing central governance, successful marketing aimed at improving on-track owner-trainer-fan experiences, and NYRA’s venture into national television the impact, are promising. Can it take racing back to its preeminent days in the first half of the 20th century, when it was one of the three biggest sports in the land? There is more competition for sports fans than in the ‘50s.

If “something big” isn’t starting, however, there’s a better-than-average chance racing may be in store for something bigger at least.

Jeff Drown

By Bill Heller

Highly successful Minnesota businessman Jeff Drown admitted that he didn’t like what he was seeing, watching his Kentucky Derby hopeful Zandon in the Gr. 1 Blue Grass Stakes at Keeneland April 9th. “When we were three-eighths out and dead last, I was wondering what was going on. That didn’t seem like the plan.”

But Zandon’s jockey, Flavien Prat, wasn’t panicking. And Zandon weaved through the horses in front him, found a seam and blew past Smile Happy to win by 2 ½ lengths, giving Jeff his first starter in the Run for the Roses on the first Saturday in May. That could give his trainer, Chad Brown, his first Derby victory. “Chad had him ready to go; he was high on him last fall and this spring. We’ve had high expectations for him all along.”

Drown was thrilled to share the Blue Grass victory with his mother and father, his wife Jill, and their five children. “It was fantastic; they had an absolute blast. Jill really likes it. She has a lot of fun with it.“

After the race, Drown was asked how many horses he owns. “I say, ‘Not enough.’ My wife says, ‘Too many.’”

Jeff Drown leads in Zandon after winning the 2022 Blue Grass Stakes

Having his father with him at the Blue Grass was special to Jeff. He got introduced to racing through his father and his friends when he tagged along for trips to Canterbury Park. “Lots of fun,” Jeff said. Years later, he got a group of friends together to buy a racehorse. “We had a little luck with it. I said, ‘Boy, this is fun. Let’s try again.’”

Drown’s ongoing success in business has allowed him to get into Thoroughbred ownership.

He is the founder and CEO of Lyon Contracting Inc., and co-owner of Trident Development, LLC. Both businesses are in St. Paul, where Jeff attended college at St. Cloud State University, earning a bachelor’s degree in business management and real estate.

“I owned real estate before I got out of college. I bought a bunch of student apartments near college at St. Cloud State. Back then, the market was really depressed. I bought them and managed them. They became valuable, and I sold them. Then I bought an apartment building. Then I built a small one, and we kept getting bigger and bigger.”

He began Lyon Contracting in 2000, and it is now one of the region’s largest real estate developers providing premium design and building services, general contracting and construction management services. The company has now expanded into North and South Dakota, Wisconsin and Iowa. Trident Development owns several of the developments Lyon Contracting has built.

Asked of his love for Thoroughbreds, Drown said, “They’re fantastic animals, fun to be around, fun to watch race. It’s no different than being in business. You have to build a solid team. It starts with (bloodstock agent) Mike Ryan. Go out and find these horses to buy. Get them broken. From there, it’s finding the right trainer.”

Zandon, ridden by Flavien Prat, wins the 2022 Blue Grass Stakes at Keeneland Racecourse

He thanks Mike for introducing him to Chad. Jeff and Chad’s first home run together was Structor, who sold for $850,000 as a two-year-old to Jeff and his partner, Don Rachel. Structor was three of four, taking the 2019 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf and earning $710,880. “We hoped to bring him back to run in the Derby, but he had a slight injury and a breathing issue,” Drown said. “He went to stud in Japan.”

Zandon is also three-for-four and has earned $713,000. That number could grow quickly if he fares well in the Derby and the Triple Crown.

Jeff Drown celebrates Zandon’s Blue Grass win

Ironically, he could be one of two Minnesota-owned Derby starters beginning with the letter Z. Zosos, who finished second in the $1 million Louisiana Derby to Epicenter, is owned by Barry and Joni Butzow of Eden Prairie.

Drown wouldn’t trade his chances in the Kentucky Derby with anybody. “It’s my first Derby,” he said. “It’s very exciting. There’s no doubt. You see these two-year-olds prepping and you wonder, ‘Can they make the Derby? Can they make the Oaks?’ There’s a lot of enjoyment taking a horse from a yearling being broken to watch him train and grow up and see the talent develop. It’s just a lot of fun.”

Preakness Stakes - Owner Profile - Tami Bobo - Simplification

By Bill Heller

Having loved, ridden and worked with horses for 46 of her 48 years, and having dealt with Arabians, Quarter Horses and Thoroughbreds, you’d think Tami Bobo would have picked up all the equine knowledge she’ll ever need. Wrong.

Asked if she is still learning, Tami said, “One hundred percent, if you just watch them. I learn every day from horses. I love to learn, so I enjoy it. Most recently, I’ve been learning about this industry. It’s fascinating. Not being born into it, I wasn’t exposed to people approaching you wanting to buy your horses.”

The most inquiries have been about one horse, Simplification, who will take Tami and Simplification’s trainer, Antonio Sano, to the Preakness Stakes off a solid dirt record of three victories, one second, two thirds and a fourth placed finish last time out in the Kentucky Derby. “My hat’s off to Antonio, managing a staff, trying to execute a plan,” Tami said. “Most recently, my learning is how to manage a Kentucky Derby contender.”

Now the learning journey moves on to Baltimore where Simplification will break from the #1 hole in the 2022 Preakness Stakes.

She may not have been born into horse racing, but she didn’t miss by much. “I have pictures of me on a horse when I was less than two-years-old,” she said. “My family moved to Ocala when I was eight years old. I showed horses all over the country.”

Working at one point as a single mother, she had to hustle to make a living with horses. “Quarter Horses were keeping me whole,” she said. “I was teaching riding lessons and pinhooking Quarter Horses. I did very well pinhooking, but the profit with Quarter Horses is small. It kept food on the table.”

Asked how she has dealt with different breeds, she said, “I think at the end of the day, it’s horsemanship. You are either a horseman or you’re not. If you know horses and pay attention, they will tell you what they need. Then you address any issues. There’s an idea that horses aren’t intelligent. It’s a misconception. Horses are extremely intelligent. They have to have intelligence and the mindset to race.”

Simplification, jockey Javier Castellano, and Tami Bobo celebrate after winning the Mucho Macho Man Stakes at Gulfstream Park, 2022

In 2010, Bobo switched from Quarter Horses to Thoroughbreds and is still enjoying the wisdom of that decision. And the first Thoroughbred she bought was Take Charge Indy, a phenomenally bred colt by A.P. Indy out of multiple graded-stakes winner Take Charge Lady, whose victories included the Gr. 1 Ashland and Spinster Stakes.