Alan Balch - Turning Point

Article by Alan Balch

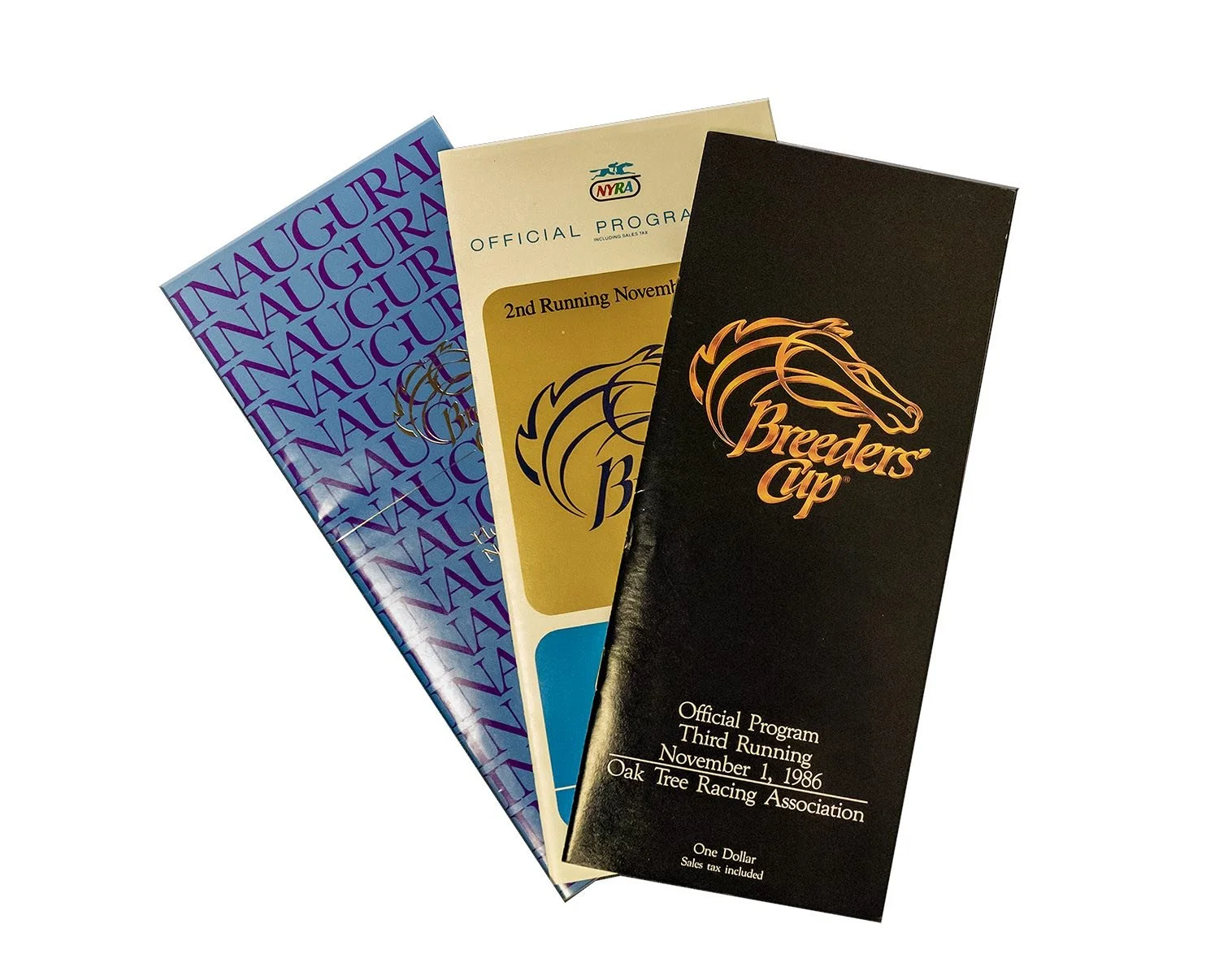

November 1, 1986, is the date the Breeders’ Cup was assured of a viable future. The first one at Santa Anita. This year at Del Mar will be the 42nd edition.

Its founding visionary, John R. Gaines, had repeatedly emphasized the importance and potential of the Breeders’ Cup for marketing racing: to stimulate its massively increased sporting awareness through the televised spectacle of our championships.

Yet, mysteriously, its early leaders had chosen two of the least telegenic tracks in America for the first editions: Hollywood Park and Aqueduct.

I’m one of the few still left in racing (or even alive) who was in the midst of that mystery at the time. In fact, it was my responsibility at Oak Tree Racing Association and Santa Anita to prepare and lead the presentations of our proposals for the site selectors, prior to 1984, and again for 1986.

That committee (which included several Thoroughbred paragons including Nelson Bunker Hunt and John Nerud) had locations across the entire nation to consider. But California tracks in those days were perennial leaders in attendance and handle and – most important – reliably nice November weather. Most everyone thought the inaugural choice came down to the southland rivals, Hollywood Park and Santa Anita.

So, in 1982 and early 1983, Oak Tree emphasized both our statistical superiority and Santa Anita’s pending hosting of the 1984 Olympic Games Equestrian Sport: the potential worldwide double of exceptional excellence for that year which would be provided for its launch. And I vividly remember Oak Tree President Clement Hirsch proclaiming to the selectors, “it has never rained on that weekend at Santa Anita,” which was true, but tempted fate. It did rain that weekend, in 1983, the year before the first one. (It has at least once since then, too.)

Hollywood Park emphasized . . . well, Hollywood . . . with Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant, and their fellow stars, along with the 20th Century movie lot. Plus, a pile of cash in earnest to assist the fledgling effort. It was chosen for the premier.

Naturally, we the losers were chagrined. Even angry. Oak Tree’s brass at the time privately suggested “never again.” Personally, and not for the last time, through the cloudy experience of bitter disappointment, I dimly saw some advantages of not being “first” at such an undertaking. Those few of us still around who witnessed that day at Hollywood Park will remember what I mean, particularly in terms of “operational challenges,” to put it much more politely than deserved.

Ultimately, and with far more reluctance than anyone would now admit, Oak Tree’s leadership decided to try again in 1985, to receive “the honor” of hosting in 1986. Breeders’ Cup administration in those days was nothing like the independent behemoth it has grown to become. Then, it relied very heavily on existing host track management, the track’s own marketing, operations, and racing expertise. It had no choice but so to do. But with that reliance came plenty of tension, most of it healthy, as the host track not only wanted to protect its own prerogatives, but also the interests of local fans, owners, and trainers. Breeders’ Cup, quite rightly, insisted on proper accommodations and recognition of all those who put up the multi-million-dollar purses – the breeders and their constituencies.

As part of our effort to win that year, Oak Tree sent me to meet with Mr. Hunt at his Texas spread, the famous Circle T, not far from DFW airport. That was an early morning I’ll never forget. “Bunker” arrived by himself to pick me up at the airport curb, driving his (old) Cadillac. “Son, I hope you’re not hungry, because we’re going to the farm first to see my horses.” He wasn’t exactly lithe, you know, but he gave me my own workout that day: we walked back and forth with each set, he describing their individual quirks and pedigrees in detail, watching them gallop or work. It was all in his head, without pause: he loved the game, he loved those horses, and knew both deeply. I was a “suit” in those days, but I saw the essence of racing in a new way. At the elbow of one of its greatest advocates. I learned way, way more than I had ever expected.

Then, onto the local greasy spoon for grits and whatever, with Bunker and his local mates yucking it up . . . that was the atmosphere for my pitch.

I can’t remember now if we had any real competition . . . we were coming off not just a highly successful Olympic Games effort, but also our Fiftieth Anniversary season where we drew our single-day record crowd of over 85,000, averaging nearly 33,000 per racing day.

If you look back now at the videos of the races that first Santa Anita Breeders’ Cup Day [https://breederscup.com/results/1986?tab=results], you can see what those truly mammoth crowds looked like. Official attendance was just under 70,000, easily a new record, as was the handle. Unlike today, however, official crowd numbers significantly understated attendance . . . since only those passing through a turnstile were counted, leaving out large numbers of backstretch personnel, as well as all the kids. The television spectacle that only Santa Anita can offer was in full, crystal-clear view.

The financial future of Breeders’ Cup was finally assured.

The Alan Balch Column - Future?

According to etymologists, the word “future” only dates to the 1300s.

Human life up to then, I guess, must have been so “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (to copy the philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ description of life outside society), that humanity could scarcely conceive of the very idea of a “future.”

If we could envision the concept of a future, I reason, we would have had a word for it.

This surprises me, since like so many other things it invented, horse racing may itself have started the first intense debates about what “the future” holds: according to the latest Artificial Intelligence, there was gaming on the races as far back as ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Way, way before the 14th century.

You have to understand the concept of “future” if you’re betting on an outcome that hasn’t yet occurred. Our entire sport, one might say, is “future-oriented.” If we knew with certainty what a result would be, we would have no game. And far, far less fun.

Just ask everyone who went against the bridge jumpers who bet the ranch on that 1-9 shot to show . . . which then didn’t.

Or, ask the breeders. They “breed the best to the best and hope for the best,” the aphorism often attributed to John E. Madden. Yes, that family . . . of Hamburg Place in Kentucky.

So, “future-orientation” is the foundation of horse racing in many respects, beginning with breeding. It’s also something I deeply considered in my last school days, and again in my early days of race track marketing at Santa Anita, more than half a century ago.

One of my teachers, Edward Banfield, wrote a controversial book, The Unheavenly City, in which he argued that social class distinctions in human society are not determined by heritable biological traits such as race, or similarities among income, occupations, schooling, or status. Those had been almost universally understood to cause classes among people, and it’s probably still a consensus. Instead, he held, a person’s class is determined by a “psychological orientation toward the future,” that is to say, whether a person is more or less oriented toward the future or the present. The more future-oriented, in his view, the “higher class.”

Gamblers, I found out through research, tend to be “present-oriented.” Tend to live “moment to moment.” And I saw this constantly throughout the race track, whether in the exclusive areas with dress codes for the ultra-wealthy, or on the grandstand main floor at the wire, where the blue-collar crowd congregated. Occupation, race, appearance, and income varied absurdly – the present-oriented bettors want action, now! Immediate gratification.

Banfield believed instead that a person’s relation to time gave them their “class culture,” which in turn then influenced their tastes and behavior.

Thoroughbred breeders are required by laws of nature to be future-oriented (mares requiring almost a year for gestation, added to the time necessary for planning matings); yet breeding is also, by definition, high-risk. Risk abounds everywhere else in racing, too. Isn’t this among the seductive allures and fascinations and contradictions racing provides, like no other sport?

In my track-management decades, the public companies I worked for always confronted the tension between earnings-per-share-this-quarter vs. investing for future growth. We couldn’t escape public disclosure of our audited financials, whether for shareholders or regulators. The discipline this required of California track management, unfortunately, seems to be a thing of the past, over more than the last two decades.

And the result looks increasingly catastrophic.

Every decision that any track management makes has to account for the size of the horse population available to race. This should go without saying -- but in California, it doesn’t! Management can announce the end of racing at a track which undergirds most of a state’s breeding, apparently without understanding or considering the consequences, not only for every other connected enterprise in the state, but also for itself. And without any objective evidence of the basis for its financial decision-making.

And, if it did understand or consider those consequences of its decisions, ponder the implications of having made them anyway.

In the 2025 Santa Anita meet which ended in June, California-breds accounted for just under half of all starts, an all-time high. As of May this year, not coincidentally, horses bred in California were over 51% of the total population stabled in the south, including 60% of the population at Los Alamitos. Every one of those was bred while year-around racing was conducted at Golden Gate Fields and the fairs in Northern California – where over 70% of starters were bred in the state.

As the North American foal crop has steadily declined, according to The Jockey Club Fact Book, the Kentucky share has been rising, to nearly 50% now. The California, Florida, and other shares, for the most part, have been declining precipitously. The implications of this are ominous for the geography of American racing as it has existed for nearly a century.

What the future holds will always be as mysterious as peering out into the vast universe with stark wonder. And all of us in racing know better than the rest of the world, and every investor, that “past performance is not indicative of future results.”

In our own California case, however, past performance has brought us to an exceptionally precarious position.

The Alan Balch Column - Artists of the air

There are ever fewer of us around who can clearly remember the world before the advent of television. And the Internet.

But as I thought about the retirement of Trevor Denman, and all his illustrious contributions to American racing, nostalgia overtook me. As it does quite often these troubling days.

Those of us who have been around for eight decades or more remember when sports were largely heard, not seen. If you couldn’t get yourself to a ballpark, or college football stadium, or race track (there really weren’t that many of them, considering the size of the United States, or any country) in the 1940s, or earlier, you followed sports on the radio.

Baseball games were often, even mostly, recreated, with appropriate sound effects. Believe it or not. I was just a kid when I realized that the pop of the ball into the glove was phony, because it was the same for each pitch. Same thing for the sound of a batted ball! The crowd effects were ridiculously similar from inning to inning and park to park. The telegraph wires provided the “facts,” and the announcers re-created the action. Someone named Ronald Reagan began his career doing that kind of sports announcing.

Then there were the movie theater newsreels, which almost always had the leading sports. You could “thrill” to Clem McCarthy calling a race, whether it was the first Santa Anita Handicap in giant clouds of dust, or Seabiscuit beating War Admiral at Pimlico, and actually see them. After having heard them on the radio when the races were run.

So, the radio was how racing first came into my life. And into millions of other lives. Joe Hernandez was the original Voice of Santa Anita. He called its first 15,587 consecutive races, never missing one at the winter meeting, from Christmas Day 1934 until he fainted at the microphone in January 1972, and died several days later from the effects of being kicked on the backstretch at Hollywood Park during morning training. That iron-man streak was one of the most remarkable achievements in sport, in its own way, ranking up there with Lou Gehrig’s.

Countless of us, particularly throughout California, only knew racing through Joe’s lilting, accented radio calls, all beginning with his booming, “There they go!” -- whether from Santa Anita or Del Mar or tracks in the north. “From the foot of the majestic San Gabriel mountains, this is your announcer Joe Hernandez at spectacular Santa Anita,” he would intone, and your imagination took over. Just like it did in other sports on radio, when the artist was . . . well, an artist!

Hearing him from childhood, live and also re-creating the day’s races, hawking “Turf Craft winners” for a sponsor, I couldn’t believe my good fortune meeting him when I was first employed at Santa Anita. We immediately started using his artistry in commercials, and he gifted me with all his old recordings, which he had meticulously kept since 1934. I pestered him constantly, and he was an unsurpassed raconteur. He unhesitatingly told me the greatest race he called was the Noor (117 pounds, Longden) and Citation (130, Brooks) battle in the 1950 San Juan Capistrano. They hooked each other for almost the entire mile and three-quarters on the main track. Noor won by a nose. Let your own imagination take over: “the two raced head and head for five-sixteenths, the lead see-sawing back and forth, in the most protracted drive,” said Evan Shipman in the American Racing Manual. “They were to continue locked right down to the wire, where, with the luck of the nod, the camera caught Noor’s nose in front.” Broken down by quarters, the race reads: 24, 23.4, 24.3, 25.3, 24.3, 24.3, 25.3! Citation led at the mile and a half mark, two-fifths faster than the American record at the time; the two set a new track record by almost six full seconds, and a new American record.

His 1940 call of Seabiscuit becoming “a new world’s champion” in the Santa Anita Handicap still rings in my ears, from the souvenir we produced, “70,000 fans going absolutely crazy, including your announcer, and he broke the track record, it’s up there.”

Is it any wonder that a bust of Hernandez graces the Paddock Gardens at Santa Anita? Perhaps the only such recognition for a race caller in the world?

As Joe’s most luminous and artistic successor, Trevor has long-since joined the pantheon of the world’s great artists of the air waves, but in an entirely different era. With the advent of racing being televised lived, he couldn’t have gotten away with any of Joe’s famous antics: he once sat down after calling the horses through the stretch to the wire off the hillside grass course, when they still had another mile to run. Waking up to what had happened as the horses turned into the backstretch, with his customary aplomb he simply blew into the mike and tapped it twice, then proclaimed, “TESTING, TESTING,” and continued as though there had been a power outage.

Having once yearned to be a jockey, Trevor’s viewpoint has always been unique. He asked permission to walk the courses at Santa Anita his first day. Asked why, he said to me, “I have to see everything from the riders’ perspectives.” He was the first American caller seamlessly to integrate the riders’ names and styles in his pictures, as he painted the race. He also seemed to know instinctively just how much horse each jock had at all times. If you listened carefully to his tenor, many were the times when you knew who the winner would be at the half-mile post.

Still, all the tributes to him can be summed up very simply: he has been, in short, “UN-BE-LIEVE-ABLE.”

Alan Balch Column - In search of . . .

Article by Alan Balch

I’ve always thought racing is the world’s greatest sport for many reasons, chief among them the fact that human and animal are united in an athletic contest that mirrors and condenses “real life” in every single race.

The struggle to compete, and to win, with the outcome unknowable in advance. Potentially accessible to and witnessed (and participated in) by the entire range of humanity, from most to least exalted, almost all of which can bet on the outcome. With the resulting winners and losers. And all the possible ramifications of that, financial and otherwise.

Add to that the track’s abundant social life, especially on race days, the beauty and majesty of horses and so many of racing’s settings, not to mention the sport’s sheer entertainment value . . . it’s hard to believe that it’s struggling to survive in much of America.

Particularly California.

How can this be so? I’m searching for answers. Reasons. And outcomes? Every individual race, after all, presents the same challenge, a search -- in microcosm.

All of us should also be searching for solutions to the serious problems our sport faces, if it is to endure. Let alone prosper.

In this vein, there could be no greater tribute to the late, esteemed, and highly accomplished Ed Bowen, than finally to act with sincerity on his 1991 plea, if it isn’t already too late . . . that “leadership by narrow vision should be replaced by a sense of common goals.” Nearly thirty-five years ago, in a very important sense, he predicted what has now befallen us, particularly in the Golden State, owing to a pronounced failure to reject the “narrow vision” of our sport’s leadership. Especially since that deficient, occluded vision has now metastasized, with very predictable results.

There can be little doubt than an utter failure to embrace effective strategic planning (including “a sense of common goals” among all of the sport’s interdependent parts) has led California racing to the precipice. Are other major jurisdictions, such as Florida, far behind?

It didn’t have to be this way. In the early 1980s, California and particularly Santa Anita racing were on the crest of a dynamic wave of strong, even record-breaking business, powered by investments in marketing, management, and new technology. The public companies which owned California’s major tracks were future-oriented. I vividly remember Robert Strub leading lengthy discussions among what have become known as racing’s “stakeholders,” including owner/trainer representation of course, and legislators, to assess our weaknesses and the potential future threats to our success. As a member of Santa Anita’s management myself at the time, I knew first-hand the projected value of our 440 acres; we sought to inspire and elaborate a business plan that would protect the future of racing while at the same time carefully developing the property from its perimeter inward, with training and stabling to be increasingly located elsewhere, principally at Pomona’s protected county property.

The details, plausibility, and ultimate strategic viability of any ancient planning are not what’s important now, in California or elsewhere. What is important is the “sense of common goals” we had then, as opposed to the “narrow vision” which continues to afflict us now, and even threatens our once-vibrant communities in California and Florida particularly.

The Strubs of Santa Anita -- Dr. Charles Strub and his son Bob -- were known above all else for their unflinching and rock-solid integrity. Some of their positions and initiatives were unpopular, but they were never shy about expressing the reasons for them, and sharing those reasons and their vision with their interdependent partners in the sport, while always considering counterpoints. Above all, they taught the gospel that Bowen espoused: “The approach that, Without us, there would be no game, stands in the way of progress. It is a simplistic approach, blinkered on both sides, for it is so self-evident in every case that it hardly bears repeating.”

However, that very simplistic and blinkered approach Bowen cited decades ago, wherein track ownership makes decisions in a vacuum, then dictates to everyone else, whether legislators, regulators, owners, trainers, breeders, jockeys, fans, or media, is what has brought us to the edge. Along with their well-documented failures to honor commitments, conflicting and even rival statements from within the same company management, and a revolving door of inexperienced and inexpert “leaders.”

Do all successful businesses “win” because they see the future so well, better than their competitors? Consider that the particularly difficult enterprise of racing, in all its aspects, especially risk, is essentially future-oriented – it begins with breeding race horses, with the annual foal crop. That fact alone requires knowledgeable track ownerships to comprehend where racing is headed many years in advance, based on objective evidence. And it mandates sophisticated guidance to tracks by breeders, trainers, and owners, whose own interdependent businesses require understanding of critical trends, that may not be readily apparent to others. Especially to any track owner who chooses to operate and make decisions about their racing enterprises in a vacuum, rather than with an objective, truly experienced strategic team.

When track ownership is apparently immune to the true interests of the human and equine populations on whose backs their profits have been generated . . . when its highly compensated managers and representatives either pretend to listen to other viewpoints or don’t even try . . . is it any wonder that all the rest of us are left to search the skies for the answers we seek, or possibly even divine intervention?

Alan Balch Column - Elite and not

By Alan F. Balch

The first time I can remember thinking about “elites” in the horse world was in connection with preparing for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Equestrian Events, to be held at Santa Anita. And in the decade after that, when defining “elite” and “non-elite” became critically important in determining how non-racing equestrian sport would be governed in the United States.

A leader of the Olympic Movement told me that tension between those two groups of athletes were at the root of most disputes in sport. I scoffed at that very thought, even though I didn’t then know what the word “scoff” even meant. After all, I reasoned, being a decidedly non-elite competitor myself, my admiration for the elites was unbounded; I knew that they knew they were all once non-elite themselves.

But I was wrong. Woefully wrong.

To be clear, let’s not have any stereotypes in what follows. All “elites” in any pursuit don’t necessarily think or act the same way; ditto those not-so-elite. And their definitions are fluid, too. Seabiscuit and John Henry, after all, lead an impressive list of “former claimers.” The list of former stakes runners is even longer. So, too, with comparable categories of humans?

While you’re pondering that, let’s turn to the pyramid, illustrated here as depicted on the back of the American buck. In all my Olympism years and after, this is the ubiquitous symbol in sport showing the tiny high-performance elite at the apex . . . everyone else in greater and greater less-elite numbers reaching to its foundation.

Now to apply it to American racing. And ultimately to California racing.

Most of us have forgotten, or never knew, that the “Pattern” race system, of grading stakes, started in Europe in the early 1970s, only came to the USA in 1974, courtesy of TOBA (Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association). All stakes are not of equal quality “black type” – in terms of horseflesh, purse, or importance to breeding. A method of sorting them was necessary, from non-graded, up in three more stages to the top, the most elite, Grade I. TOBA, using proven and mostly objective expertise, sets minimum purses for each level, and analyzes field-quality annually to adjust grades.

But the vast majority of American races, now totaling around 35,000 annually, are not graded stakes . . . only about 450 are, with about 100 at Grade I. The very apex of racing’s pyramid is tiny indeed. Elite.

So, what?

As American gaming has evolved over the last 30 years, the consequences for racing . . . and, particularly, California racing . . . have been dire. I vividly remember the head of Churchill Downs in the early 90s, Tom Meeker, addressing a conference in California, where he put forward a preliminary strategy for his company to engage heavily in non-racing alternative gaming initiatives. I was appalled. Wrongly. Again.

Think of the almost infinite number of bettable “outcomes” during a racing day at the track, not just on the races themselves but also on everything else, from objective numbers to colors to lengths to times to you-name-it.

I believed then (and still do) that racing as an industry should have been investing, for many years prior, in serious research and development: to broaden both the concept and definition of pari-mutuel wagering beyond its then-existing horizons. Adding fixed-odds races and a multitude of propositions and other bets, to compete with every type of game then available away from the track. Amending existing Racing Law to permit such gaming without serious limitation. Always preserving the race track as the destination for and focus of legalized sports betting. Since racing invented it centuries ago.

“Marketing myopia” used to be a thing: the most famous example of it was what befell the railroad barons. Those myopic tycoons kept saying the railroad itself was their business, instead of transportation broadly defined – causing them to miss out on much greater wealth opportunities from every other more modern mode. Or even the first Tote company, which was distracted by making so much money from racing when it probably could have outdone IBM in what became “technology.”

But Churchill Downs, under evolving leadership, leveraged its monumental, nearly infinite brand value in multiple directions, and became a gaming juggernaut. While preserving and enhancing its Kentucky home writ large. Have you paid attention to its stock price and market value over these last couple decades?!

American purses in New York, Kentucky, and Arkansas, particularly, have soared on the basis not just of connected casino and other gaming revenues, but also on Historical Horse Racing (HHR) machine income, which mimics slots. While we in California grapple with the opposite scenario.

To make matters much worse, 1/ST suddenly and peremptorily closed Golden Gate Fields – despite Northern California racing’s position as the foundation level of California’s historic pyramid of racing and breeding.

Since then, there have been further attempts - led by one entity - to impede every effort of California breeders and its northern community of owners and trainers to organize a new and independent circuit there.

That’s the “Eye of Providence” at the top of our American pyramid, as if to symbolize in this instance that even California racing’s elites and aristocrats will not long prosper without a broad and functional foundation. We all need each other. Any strategy for a rational way forward cannot and will not succeed without brainstorming, understanding, intellectual support, and commitment from both the non-elite and elite together.

Or are our California elites too afflicted with their own version of a selfish myopia, which comes with such great risks even and especially to themselves?

Alan Balch Column - Principles of Marketing

Article by Alan F. Balch

When I first joined the management of Santa Anita in 1971 (that’s right, over a half-century ago), one of the earliest meetings I had with its leadership made an everlasting impression on me.

Indoctrinating me were Robert Strub, son of the track’s founder Charles H. “Doc” Strub, and General Manager Fred Ryan, who had worked for Eugene Mori (of Hialeah, Garden State Park, and Tanforan fame). Giants of American racing evolution.

I had been placed in charge of ‘public relations’, which included advertising, promotion, and publicity. The term ‘marketing’ had only recently become relevant to most businesses and had not yet been applied to racing management anywhere in the world. The first thing I had to remember, I was told, was that free admission to boost attendance was never to be suggested. As Mori had once famously said, “the view alone at Santa Anita is worth the price of admission.” Ryan added, “we have the tightest gate in racing, and it’s going to stay that way.” Non-betting sources were 50% of revenue then, remember.

Then, Strub had his say. “My father always warned that we can’t let ourselves go the way of buggy whips. We continually need new, young thinking, and that’s why you’re here.” I guess I don’t have to add that way back then, there was a thirty-year age gap between mine and the next older department head on the track staff. My assigned task, my only task, was to drive attendance. “Don’t worry about anything else,” Strub advised, “you get them here, and the betting will take care of itself.” True then. Still true.

Marketing for profit never changes. What’s old is new. In these pages two years ago, I extolled the virtues of Royal Ascot. Especially its continually advancing marketing, under Ascot’s director of racing and public affairs, Nick Smith, who says (and way more important, does) the right things.

So, too, says (and does) Mark Taylor, of Taylor Made Farms and through Medallion Racing a partner in a Royal Ascot Group 1 winner Porta Fortuna.

Both of them understand marketing in the old Santa Anita way, now lost from much of American racing, especially in California. Real marketing is an investment, not principally an expense. It is also an attitude. A way of doing business. The only way ancient businesses (which racing and breeding certainly are) can survive a constantly changing and increasingly competitive world. Engaging and funding proper marketing, rightly understood, is the necessary if not the sufficient condition for the survival of any business enterprise in the modern world. And, sad to say, most of what now passes for ‘marketing’ in California racing is anything but.

Here’s Taylor, for whom Royal Ascot was “beyond my wildest expectations. However they have done it, everybody who works there genuinely takes an interest in the customer experience. What I really took away from it for our organization is more training and spending more time getting each employee to really put themselves in the customer’s shoes. And say, ‘how can I make this an incredible experience for them and let the person know I care.’”

This very quotation could have been lifted right out of Philip Kotler’s foundational textbook, ‘Principles of Marketing’, which was the inspiration for modern marketing beginning in the late 1960s. “Marketing is sales from the customer’s point of view.” Further, Kotler advised that marketing point of view had to be ingrained in all functions of any organization, from operations to finance to production, in order to optimize success. And that was no easy task, since that marketing point of view . . . as it begins to succeed at all levels and results in growth . . . creates more and more hard work for everyone in every function, as well as a new mindset.

Emphasizing the critical nature of attendance at the races, not just betting, Ascot’s Smith mirrored those comments: "Hospitality was at record levels this year, with 13 Michelin stars across the kitchens, but that top-end fine dining option is quite resilient whereas general ticket sales aren't always. The racing is at the heart of it for a lot of people. You have a competitive interest betting product as well as racing at the highest level, and all of these things need to come together. We have huge positives which we need to promote and be proud of. This is a time to step back and say let's look at what's really good about the sport, promote it, be proud of it and build from it." Amen, I say.

Where racing is struggling (including California), failures of marketing and management are critical reasons. Even Del Mar, long the brightest light in the West, has dimmed. Where boisterous big turnouts of over 40,000 stormed the track in the last decade, the largest attendance last year was barely over 20,000. For the last three years, just over the 10,000 mark attended its marquee $1-million Pacific Classic, half to a third of what it had drawn historically, supposedly in the name of ‘superior customer experience’ for the relatively few present! The abysmal attendance at the last Breeders’ Cups at Santa Anita, and on its own prestigious days, were actually fractions of the figures announced.

Since its origination some 300 years ago, racing as a sport and enterprise has been relentlessly confronted by change and competition. That it has survived at all is remarkable, I suppose, but also a tribute to its majesty and allure . . . when presented, managed, and marketed properly. Look not just to Ascot, but also to Belmont at Saratoga, to Keeneland, and to Churchill Downs: investment, renewal, and sophisticated, integrated marketing, both industrial and consumer, with all its modern tools, are essential to racing’s future.

Many say that the future of racing has little to do with attendance at the track. If that is so, where will all the breeders, trainers, owners, and bettors come from?

Alan Balch - Fiefdoms redux?

I’m reminded of racing’s counterproductive fiefdoms by a 2008 writing in these pages of the late Arnold Kirkpatrick, my much-revered colleague and friend. Back then, it seemed to him, there were way too many fiefs in the way of industry-wide accomplishments.

To Arthur Hancock’s suggestion that our problems were caused by a lack of leadership, Arnold was “unalterably convinced that our problem is not a lack of leadership but too much leadership.” He counted 183 separate organizations in Thoroughbred racing alone, each with their own agendas and jealousies. “With 183 rudders all pointed in different directions, we have two possible outcomes – at best, we’ll be dead in the water; at worst, we’ll be breaking apart on the rocks.”

In 2024, can it be said, without irony, that this is the best of times, and the worst of times?

In North America, and California in particular, an historic sport and industry contraction is well underway, by every possible indicator – led by the declining foal crop. One might think there has been a corresponding contraction in the list of racing’s organizations; somehow, I doubt that’s true. Nevertheless, in the “Golden State,” once a perennial leader of American racing, we have lost a critical mass of tracks since 2008: Bay Meadows, Hollywood Park, fair racing at Vallejo, San Mateo, Stockton, and Pomona, and Golden Gate Fields this year.

Is it simply a coincidence that this all happened while one racing operator – the Stronach Group -- increasingly dominated and controlled the sport in California, as no track owner ever before was permitted to do?

Arnold’s word “fiefdom” . . . comes back to mind, but now from a different perspective. In European feudal times, as we learned in school, the fief was a landed estate given by a lord to a vassal in return for the vassal's service to the lord. There are a great many California owners, trainers, breeders, jockeys, vendors, fans, and even regulators, who have been wondering how the vassals ever turned the tables.

In a Los Angeles Times interview published on April 5, Aidan Butler, the chief executive officer of 1/ST Racing and Gaming, the Stronach operator, used the term “imbeciles” to describe those who would question the company’s intentions, and perhaps its motives, in sending what was widely perceived as a blatantly threatening letter to the California Horse Racing Board.

Instead, he termed the letter “transparent.” And then stated, “if nothing else, people have been forewarned.” Seconds before, he had claimed that the amount of money Stronach had invested in Santa Anita proved its good intentions. This is the same executive who months earlier had suddenly announced, giving stakeholders notice of only hours, that Golden Gate Fields would be closed within weeks, before changing his mind under pressure from the rest of the industry.

Confused?

Stronach’s track management may be described many ways; truthfully “transparent” is certainly not one of them, despite constant assertions to the contrary. As a private family company, even in a regulated industry, its leaders can claim whatever they want with impunity. After all, the exceptionally valuable real estate on which most (all?) of their track holdings reside appears to make them immune from audit or inspection: they rarely, if ever, are reluctant to tell their racing fraternity vassals that it’s their way or no way. The damage resulting from that attitude is staggering.

Edward J. DeBartolo, Sr., was a predecessor billionaire owner of multiple American tracks. Perhaps, however, because of his ownership of great and successful team sports franchises, among other interests such as construction, retail, and shopping center development, not to mention education and philanthropy, he knew what he didn’t know. He realized he always needed teammates. He delighted in saying to his fellow track owners that managing race tracks was by far the most difficult of all his enterprises, due to the elaborate interdependent structure of racing, and its nearly infinite number of critical component interests, each with different expertise. More complicated than any of his other pursuits, he said! To succeed in racing challenged him to learn, and his success resided in hiring, consulting with, and relying on people who knew more than he did. As it did in all his businesses.

Even to the most oblivious, it can’t have been hidden to the Stronach leadership that entering the heavily-regulated California racing market in the late 1990s would present serious challenges, at least as enormous as the opportunities. Acquiring the two glorious racing properties of Santa Anita and Golden Gate (with a relatively short leasehold at a third, Bay Meadows) had to have been exciting. To someone with the DeBartolo outlook on interdependent management, rather than the inverse, it could have been invigorating and boundlessly successful.

That the opposite has resulted is an enormous tragedy for the sport worldwide, not just in California. After all, the State of California’s economy (as measured by its own Gross State Product) is among the top five in the world, outranking even the United Kingdom’s. How could this happen?

Had Stronach leadership begun, at the outset, consulting and cooperating in good faith with its California partners (including regulators, legislators, and local communities, not to mention fellow racing organizations, the owners, trainers, breeders, and other tracks), learning from them as teammates rather than dictating to them, California racing would look far different now than it does. Its imperious and constantly changing management leadership compounded perennial problems and threats, not to mention complicating the industry’s politics and standing in California sports. Obvious failures to understand California markets and invest in sophisticated communications and marketing also have been apparent, despite continual assertions to the contrary.

Is there still hope for California racing? Yes . . . but if and only if honest humility suddenly appears from Stronach leaders, and immediate, sincere engagement occurs with all the rest of the interdependent entities upon whose lives and success the racing industry depends.

Alan Balch - What, me worry?

Article by Alan F. Balch

If you’re of a certain age, you can’t help but remember Alfred E. Neuman, the perennial cover creature of MAD magazine. I sure do, and not mainly because of the magazine’s content . . . I was a dead ringer for him. Skinny, gap-toothed, freckle-faced, red-haired, with crazy big ears. So my laughing “friends” said, anyway.

Kids can be so mean to each other.

Obviously, the teasing stuck with me. For a lifetime. But back then, I shared another trait with him: nothing worried me. Everything seemed like a joke. Like everyone else, I just yearned to grow up so I could be free. Free of school, free to live all day, every day, with horses in a stable, if I wanted. Which I did.

By college, though, I was an inveterate worrier, and still am. My best friend once said, “Alan, if you didn’t have anything to worry about, you’d be worried about that!”

We in racing, and in California particularly, have an overabundance of worries these days. How the hell did it all happen? From leading the world in attendance and handle a few short decades back, not to mention great weather, we have (not suddenly) come to . . . this.

In an interdependent sport, business, industry, such as ours, everything one part does affects all the others. No part can succeed without the others; if one fails, all fail. Unfortunately, there have been many failures to observe amongst all of us.

Ironically – but not entirely unexpectedly – I believe California racing’s historical prowess started to unravel in the best of times: the early 1980s. Our California Horse Racing Board regulators no doubt believed the industry was so strong that it could easily withstand disobeying a statutory command, which “disobedience” some of us believed could lead to disaster.

Hollywood Park sought to purchase and operate Los Alamitos, despite a clear prohibition in the law forbidding one such entity to own another in the state, “unless the Board finds the purpose of [the law] will be better served thereby.” Santa Anita’s management at the time objected strenuously, including in unsuccessful litigation, providing a “list of horrors” that might ensue if the delicate balance among track ownerships in the state were disturbed.

Among those horrors was the prediction that a precedent was being set for the future, where one enterprise might not only become significantly more influential than others, it could even become more authoritative and powerful than the regulator itself.

We at Santa Anita, whose management I was in at the time, were deeply concerned about our own influence and competitive position . . . and our reservations and predictions were largely ignored, undoubtedly for that very reason. At everyone else’s peril, as it has ultimately turned out.

That Hollywood Park acquisition move turned out to be ruinous. For Hollywood Park! And the cascade of repercussions that followed, including changes of control at that track, led to another fateful regulatory change in the early 1990s: the splitting of the backstretch community’s representation into separate and sometimes rival organizations of owners and trainers, which in every other state in the Union are joined as one. Before his death, the author of that idea (Hollywood’s R.D. Hubbard) said, “That was the worst mistake I ever made.”

Consider that in the first half-century of California racing, interests of the various track owners, as well as owners and trainers in one organization, were carefully balanced. No one track interest ruled, because the numbers of racing weeks were carefully allotted in the law by region.

Unilateral demands of horsemen went nowhere. Practically speaking, the Racing Law couldn’t be changed in any important way without all the track ownerships agreeing, with the (single) horsemen’s organization. In turn, that meant there were regular meetings of all the tracks together, often with the horsemen, or at their request, to address the multitude of compelling issues that constantly arose.

But when that balance was disrupted, even destroyed, is it any surprise that for the last three decades the full industry-wide discussions that were commonplace through the 1980s are now so rare that track operators can’t remember when the last meaningful one even took place?

Thoroughbred owners have meetings of their Board not even open to their own members, and never with the trainers’ organization. The Federation of California Racing Associations (the tracks) apparently still exists, but hasn’t even met since 2015. The Racing Board meets publicly, airing our laundry worldwide on the Internet, showcasing our common dysfunction and lack of internal coherence to anyone who might be tempted to race on the West Coast.

Not to mention those extremists who cry out constantly to “Kill Racing.” And one private company, which also owns the totalizator and has vast ADW and other gaming holdings, not to mention all the racing in Maryland and much of it in Florida, answerable to nobody, controls most of the Thoroughbred racing weeks in both northern and southern California.

Our current regulators didn’t make the long-ago decisions that set all this in motion, and may not even be aware of them. In addition, the original, elaborate regulatory and legal framework that was intended in 1932 to provide fairness and balance in a growing industry is unlikely to be effective in the opposite environment. And the State Legislature? All the stakeholders originally and for decades after believed nothing was more important than keeping the government persuasively informed, in detail, of the economic and agricultural importance of racing to the State. Tragically, that hasn’t been a priority for anyone in recent history.

Just to top it off: as an old marketer of racing and tracks myself, I believe in strong, expensive advertising and promotion as vital investments. For the present and future. I once proved they succeed when properly funded and managed; but I’m a voice in the wilderness now, to be certain, when betting on the races doesn’t even seem to be on the public’s menu.

What? Me worry?!

Alan Balch - Federalism Redux

As if we in American racing weren’t already facing serious threats to our very existence as a major sport, and an exceptionally elaborate interdependent business, now we’re also an example of the present national political dysfunction and irrationality. Just one more sharp dagger.

Over a half-century ago, I spent a previous lifetime in academia—studying government and political philosophy, with an emphasis on American political enterprise and evolution. When I joined Santa Anita, I never thought that I would one day witness at the racetrack the fundamental contradictions of the American founding!

But here we are, courtesy of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA). As you are probably aware, this addition of national government oversight to Thoroughbred racing, which had previously been the province of state-by-state regulation, came by way of its sudden inclusion in a must-pass federal budget bill in the waning days of the Trump presidency. Courtesy of Republican Party Leader Senator McConnell, of Kentucky—whose patrons The Jockey Club and Churchill Downs advocated for it.

There is little doubt that the enabling legislation wouldn’t have been adopted had it been considered on its own merits, absent the cover of the required federal budget.

In any event, the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted at the founding, reads in whole, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

Since racing had always been regulated by the individual states where it had been held (for nearly 100 years, or even more in some states), its sudden impending regulation by the federal government was bound to raise serious issues of “federalism.”

Way back when American schools required Civics and American Government to be taught—rigorously—we all were expected to learn the basic founding stories: about the original thirteen colonies of Great Britain, the American Revolution, and the Articles of Confederation which preceded the Constitution. Suffice it to say that the age-old tensions between the prerogatives and responsibilities of the individual state governments and those of the national (“federal”) government underpin all of American politics.

Federalism, our system of government whereby the same geographic territory is under the jurisdiction of multiple layers of authority, is at once the genius of our American democratic republic and its potential debilitating weakness. Such a structure requires cooperation—and repeated compromise. It’s been nearly 250 years since our Declaration of Independence. To this day, our founding tensions underlie virtually all our politics and governments . . . from local school boards to town and city councils, to counties, states, and the federal government.

So, is it any wonder that when consensus in our complex, diverse nation is still so difficult to achieve on fundamental issues of human rights, race and voting procedures, our own (trivial?) questions of how horse racing is to be governed hardly have merited a glance?

Irony has heaped upon irony in racing’s current regulatory quagmire. The contemporary political party that seems to believe in the supremacy of states’ prerogatives as to critical issues of voting and personal behavior—the opposite one from the party that used that same banner to fuel the secession of Southern states igniting the Civil War in 1860—has abandoned it when it comes to racing oversight! Its leadership believes the heavy hand of the federal government is too weighty for issues of life, death and voting, but necessary to wield on regulating racing.

Thus far, trying to use federal law to serve the cause of regulatory uniformity nationwide has resulted in the opposite, at great expense, monetary and otherwise. The “otherwise” may well include sacrificing basic tenets of due process of law, such as the presumption of innocence for those accused of misbehavior.

And all of this was so unnecessary. The Jockey Club and the other prime movers of HISA should have simply engaged in good faith at the outset with the Association of Racing Commissioners International (ARCI). Its model rules have been developed over decades of interfacing with state racing boards and the Racing Medication and Testing Consortium, which includes trainer and owner representation. With that approach, the issues now plaguing all of us would be much diminished, if they still existed at all. Bottom line, nobody in the sport wants cheaters. But a relatively few in the sport, it would seem, do still want to decide for and dictate to all the rest of us. Does The Jockey Club actually want a more rapidly shrinking sport? It’s entirely possible, perhaps probable, with all the foreseeable angst.

HISA leadership professes to be open, transparent and willing to consider improvements. If that is so, why won’t it immediately understand the serious threat of “provisional suspensions” to every trainer and owner, and the near-total lack of transparency and timely response when it comes to cases of obvious environmental contamination? That very concept of “provisional” suspension, which came from international non-racing equestrian sport regulation, is indicative of a blindness to the realities of racing which would have never occurred were the ARCI model rules adopted.

Instead of using its expensive public relations machine to continue sending repeated self-serving, congratulatory messages to a skeptical community, HISA should tell all the rest of us how we can go about expeditiously amending its rules to provide for practical, fair and truly transparent governance.

Publius (the pseudonym for James Madison in Federalist Paper #47) wrote this in 1788: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

As it stands now, HISA’s authority, rule-making, disciplinary practices and governance are perilously close to just that destructive.

WIth absent judicial intervention, only HISA itself can open the door to necessary reform—before it’s too late.

Alan F. Balch - Elephants

Article by Alan F. Balch

Among my earliest childhood memories is loving elephants. As soon as I first laid eyes on them in the San Diego Zoo, I was fixated. I still am. Not too long ago, at its relatively new Safari Park, I stood for an hour watching these pachyderms of all ages in their new enormous enclosure, enjoying a massive water feature. Now, every time I fire up YouTube, it knows of my interest; I am immediately fed the latest in elephant news and entertainment.

Right up there with horses and racing.

You probably know, however, that you’ll never see elephants in a major American circus anymore. No more elephant riding, either. Even that is endangered in parts of the world where it goes back centuries, along with forest work. Zoos now breed their own.

Which brings me to the difference between animal welfare and animal “rights,” which is the crux of the problem horse racing faces everywhere it still exists, not to mention all horses in sport.

Owing to many, many factors, animals in our contemporary world have increasingly and vocally been portrayed as having rights, just like humans. (Or as humans should, we might more exactly say.) Even some of the more moderate organizations that oppose horse racing couch their fundamental opposition in the bogus claim that there is no critical difference among species, human and non-human (just as there is none among races of humans) . . . that to believe there is such a difference is to be “speciesist.” Which, to our enemies, is at par with racist on the continuum of odious and repulsive.

Truth be told (not particularly important for those who would destroy equine sport), there are in fact critically important differences between species, and types of sentient beings.

The most critical is that only humans among all species can conceive of the very notions of welfare and conservation! Other sentient beings cannot, even if they experience rudimentary “feelings.” Nor can they conceptualize their own welfare, let alone of the welfare of other animals or sentient beings. Only humans can make intellectual choices. Don’t these simple irrefutable facts order the species, in favor of humans over all others?

Humans formed the first (and only) animal welfare organizations. Animals didn’t. Humans developed conservation. Animals didn’t. Humans developed veterinary medicine, not animals, as well as genetics, domesticated breeding programs, and on and on.

For better or worse, humans also discovered and elaborated anthropomorphism . . . the attribution of human behavior or characteristics to animals. Insects. Or objects. The world now has humanistic talking and thinking animals of virtually every description—crickets and ants, and even cars, machines, weapons, and airplanes. We think nothing of it, do we? Yet it tempts us—dangerously—to consider all of those as members of our own family.

To do so is fantasyland. “Alternate realities and facts,” products of humans, are counters to objective truth. They threaten all humans. And, therefore, all animals. This kind of “intelligence” is not just artificial, it’s destructive. Its potential ramifications are frightening, to any human capable of fear. Would anyone like to see a “friendly” nuclear weapon arrive? Nor can I forget the three young jokesters in 2007 who thought a tiger in a San Francisco zoo might be fun to provoke—until she killed one of them.

The anthropomorphist or vegan humans who hate racing and all organized activities with non-humans (including pet owning), which they claim must require the animals’ “informed consent,'' seriously threaten the future of all equine sport. They have captured the attention of the world’s media; they capitalize on the contemporary and widespread emotion that animals are part of our own family, exploiting any relatively rare incident of abuse or sheer accident as a reflection on the whole of sport. The media embraces and embellishes the controversy without understanding the dangers of its origin.

Sadly, it is we who have bred these elephants in our room. Even though horse racing above all other equestrian activities has advanced the equine standard of care and veterinary medicine immeasurably and inexorably—for centuries now, worldwide, that exceptional standard has collided with market economics and human greed, to the detriment of the race horse—imperiling the very sport itself. We have increasingly been breeding potential unsoundness to unsoundness for at least half a century, then disguising and possibly amplifying conformation defects with cosmetic surgeries. And we wonder why our horses are more fragile?!

In America, our breed registry’s grandees have looked everywhere but in the mirror for the sport’s villains. In so doing, they have invited, stimulated, and even enhanced horse racing’s growing disrepute. They have cast blame for our woes on trainers, veterinarians, therapeutic medications, track operators, state regulators, and even the bedrock of American law—due process—but not on themselves. Their new, elaborate, often indecipherable enormity of national rules wrongly purport to address every potential weakness in the sport. But not weakness in the breed itself, for which they themselves must be held responsible.

The aim of breeding a better horse is the foundation of horsemanship. Or it should be. By “better,” for a couple hundred years, we meant both more durable and more tenacious for racing—racing as a test of stamina, substance, and soundness. “Commercial” breeding, for the sake of breeding itself and financial return at sales, not to mention glory at two and three, with quick retirement to repeat the cycle, is failing the breed itself. Obviously.

Our sport’s aristocrats, who are so fascinated with the efficacy of their new rules, have long needed a look at their mirrors. Let’s see if they can also regulate their own house—registration, breeding, selling—developing effective deterrence to and prohibitions on the perpetuation of fragility and unsoundness. Can they incentivize breeding for racing, to test substance and stamina?

That’s the elephant in our room: the critical, fundamental need to breed a sounder horse.

Alan Balch - The stress test

Article by Alan F. Balch

My old horse trainer, one of the wisest people I ever met—and I find many trainers to be so wise, way beyond their formal educations—used to define stress this way: the confusion created when one's mind overrides the body's basic desire to choke the living [bleep] out of some [bleep] who so desperately needs it.

Any trainer reading this will immediately recognize the sensation, surrounded as he or she is by countless other “experts” (at least in their own minds): regulators, do-gooders, gamblers, veterinarians, reporters, owners, blacksmiths, hotwalkers, entry clerks, and track officials—to name only a very few categories of her or his advisers.

Everyone else in racing these days (not to mention virtually everyone else on Earth) is experiencing that same sensation. Our mutual feelings of stress are ubiquitous—that is to say, they’re everywhere in virtually everything we’re doing.

I can remember a time, not that long ago, when people went to the races, or owned horses, to get away from politics. And stress. The objectivity of the photo-finish camera, invented nearly a century ago now, was a welcome relief from all the conflicting opinions outside the track enclosures. And my $2 was just as valuable as Mr. Vanderbilt’s.

To be certain, there have always been politics within racing—our own politics. And gradually, with politically appointed state regulators, non-racing politics, real politics, became more and more intrusive as the decades marched on.

What we have witnessed in the last few years, however, is something new. Or, perhaps, a throwback to the early 1900s, when much of American racing was simply abolished in the name of “reform,” which a “reform” movement later led even to prohibition! It’s perhaps instructive that prohibition of alcoholic beverages ended about the same time that modern pari-mutuel betting on newly approved tracks began in the 1930s.

I’m not sure that what we’re witnessing now in racing—the advent of national, federal legislation to accompany and supplant state-by-state regulation—will be as cataclysmic for racing as what happened before in the name of “reform,” but I’m also not sure that it won’t be.

What it comes down to is this: how much reform did or does present-day racing really need? Are the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA) and its bureaucratic bedfellows actually going to result in whatever reform is really necessary? Or, are we going to fail this stress test?

The Jockey Club and Breeders’ Cup—those august, elite, and self-righteous bodies who always claim to know what’s best for racing—now find themselves arrayed against the National Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association and the Association of Racing Commissioners International. The latter can be equally self-righteous and are accompanied by some state regulators, but have no august or elite pretensions. Quite the opposite, in fact, they claim to represent “the people.” Which is to say, bluntly, the non-elite. And let there be no mistake: in racing as in all things, the less-than-elite vastly outnumber the elite. The taking of sides we’re seeing leads to absurd ironies: one vocal HISA supporter dared to scorn the Kentucky HBPA for not being democratic enough . . . apparently not realizing that The Jockey Club, prime mover of HISA, is perhaps the least democratic organization on the globe, with the possible exception of the Catholic Church.

More importantly, the top of any sport’s pyramid is very, very tiny indeed, and isolated, unless it has a broad and sturdy foundation with ready and fair access to the top. Those at the tip-top would do well to consider that fundamental fact. In American racing, remember that those graded stakes purses are funded by how much is bet on the overnights—meaning, for the most part, non-elite and lower level claiming races—which need robust field sizes to attract sufficient handle. Those are the trainers and owners represented by the organizations who are questioning the necessity and implementation of several supposed HISA “reforms.”

We hear these reasons for racing’s supposedly necessary reforms. First, we need to stamp out cheating. Second, we need to better protect the welfare of horses. Third, we need uniformity of racing rules throughout the country.

Following the experience of the last year or so, does anyone now seriously believe that adding a new layer of national bureaucratic and governmental oversight to the state oversight and regulation we’ve had since the 1930s will lead to greater uniformity, rather than more complexity, confusion, and cost? Predictably, uh, no. And, in the bargain, just what is happening to the total cost of racing regulation and oversight?

Equine welfare? To the extent that the rest of the nation expects to be required, for the most part, to follow California’s progress, this could be a positive. But is it outweighed by resulting confusion, misunderstanding, and outright resistance to its very necessity, practicality, and incremental costs? Why were so many complex regulations that were not in dispute replaced by even more intricate new language and protocols that indicate lack of fundamental horsemanship?

Finally, the worst self-inflicted wound, the perception that cheating is rampant in racing, repeated endlessly and without proof by The Jockey Club, in its anti-Lasix crusade. Yes, the authorities discovered and proved a cheating scandal via wiretaps intended for another purpose. So, please point us to the armor in the HISA hierarchy of complicated supervision that will prevent such an outrage from happening again.

What’s to be done? Well, we can continue to hope this bronc can be broke . . . and be thankful our cowboy is mounted on a horse instead of a tiger. If he is.

Alan Balch - Awake yet?

Article by Alan F. Balch

I don’t know about you, but as for me, a couple of years ago when I started hearing about being “woke,” and since then have been relentlessly pounded with the expression, I hadn’t a clue what that meant.

I’m not sure I entirely understand it now . . . but I did some research.

At just about the time of his commemorative holiday in January, I learned that the late Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s last Sunday sermon prior to his 1968 murder was entitled, “Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution.” Dr. King referred to the tale of Rip Van Winkle, who had been asleep for 20 years, dozing off during the reign of King George III of England, and awakening during the presidency of George Washington. He literally slept through the American revolution.

King preached that his congregations needed to awaken to the injustice still all around them, and demand meaningful change. He exhorted them "to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change.”

If I had fallen asleep in 1990, when I had major responsibilities at both Golden Gate Fields and Santa Anita, and awakened today, I would recognize the San Francisco Bay and the San Gabriel Mountains immediately. But I would have slept through a different kind of revolution than Rip did.

Given the ages and longevity of racing’s community of trainers – in California and elsewhere – is it any wonder that the era of critical change our sport has faced and continues to undergo feels threatening, daunting, and sometimes even overwhelming?

While racing has perennially (ever since its modern conception in the 1930s) been the most heavily regulated of all professional sports, by far, recent additions of a new federal regulatory structure, added to various and sometimes inconsistent state and track rules, have made for an even heavier burden on all those responsible for the welfare of horses. Each new straw on this camel’s back can seem like a tree.

If the trainers and veterinarians need to be wide awake, so too do the owners, regulators, media, and track managements! The impetus for Congressional action and federal regulation of racing, on its surface, was to harmonize and improve oversight of the sport. Wasn’t it?! Not to mystify and complicate it any further.

Training a horse . . . and horsemanship itself . . . are infinitely complex by themselves. To begin with. There are plenty of books about these subjects, but no manuals. The rules governing training have sometimes been conceived, enforced, and praised, by individuals whose experience doesn’t include even one working minute in a stall or shed-row, and who couldn’t begin to persuasively define horsemanship. And who then wonder why morale on the backstretch isn’t positive?!

All of us in racing or non-racing equestrian sport, worldwide, have been raised with the mantra that the welfare of the horse is paramount. But actions speak louder than words. With all the attention to elaborate rules and regulatory structures, where is the corresponding attention to and investment in backstretch conditions, for both human and equine residents? In track conditions and the latest surfaces and technologies?

We hear a great deal today about equestrian sports’ “social license to operate,” that the treatment of animals must match the public’s expectation of proper welfare practices.

“Well,” I’ve always been tempted to say, “let’s bring the public to the horses, where they live, so the public will see how well they are treated.” At Santa Anita, we did that for years, and very successfully. But when I see many of today’s backstretches, as opposed to how they looked when I went to sleep 30 years ago, I’m appalled. If regulators and track managements expect the professionals who care for the horses to bear the burden of more onerous requirements and regulations for behavior than ever before, shouldn’t the conditions under which the horses live/train and the professionals (including veterinarians) practice their trades be at the highest levels of expectation as well?

In all the “social license” and horse welfare discussions, it’s appealing but wrong to ascribe human characteristics to horses – as animal “rights” groups consistently do. We who love horses, as horses, must do better, in our own language, to avoid the traps the enemies of sport with horses are setting for us, whether consciously or not. Two-year-old colts or fillies (or even foals and weanlings) should not be referred to as “babies.” They aren’t. We shouldn’t call males or females “boys or girls,” either. They aren’t. We shouldn’t say, “he loves being a race horse.” He doesn’t know what that means. The concepts of “love,” or even “happiness,” are human, not equine. He probably does “love” carrots or sugar; actually, he doesn’t, because he doesn’t think like we do. But a good trainer knows when a horse is content, satisfied, happy . . . or nervous, upset, and unhappy! Even though the horse is not those things in human terms, but instead in the context of being an equine. An animal.

In 1824, William Wilberforce, member of the British Parliament, was a founder of what became the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the very first animal welfare organization in the world. He was among the most wide-awake of all humans at the time, and maybe ever: he was the leading English advocate for the abolition of slavery. He was a man of conscience, rather than party. He led his peers in advocating new ideas, remained vigilant, and unflinchingly faced the challenges of necessary change.

He knew the differences between humans and animals, and that real animal welfare can only be achieved and maintained by humans.

Alan Balch - Remembering where we come from

Victor Espinoza photo

Like so many of us in racing, I’ve been horse crazy my entire life.

Some of my earliest memories are being on my dad’s shoulders, going through the livestock barns at the San Diego County Fair, and then lighting up when we got to the horse show . . . which, back then, was located just outside the turn at Del Mar into the backstretch, at the old 6-furlong start, long before the chute was extended to 7/8. All their horse barns back then were the original adobe, open to the public during the fair, and we could walk down the shed rows talking to the horses, petting those noses and loving the stable smells.

At least I did. My mom was appalled, of course.

She assumed, I’m certain, that I would grow out of my weird fixation. But the way those things go at certain ages, the more I was discouraged, the more obsessed I became. The fact that our family was decidedly not elite in any respect, certainly not educationally or financially, became a great opportunity for me to work at what I loved the most: taking care of the horses, to begin with, and camping at the barn whenever possible. At first, I wasn’t getting paid at all—except in getting to learn to ride by watching and listening and then riding my favorite horses without having to rent them. Lessons were out of the question.

I gradually learned that the people who owned and showed and raced horses had to have the money to do it, and being able to do that myself was beyond my imagination. I don’t remember ever caring. Nor do I remember ever being mistreated because of my lowly station. In fact, it was a great bonus for me to get out of school at times to travel to shows and live in a tack room in the stables. And, as I grew older, to start getting paid actual wages for my work.

Making it through college and graduate school without having to wash dishes in the dining hall led to my loving equestrian sport in a different way and at a much different level—especially when I met Robert Strub at the Forum International Horse Show in Los Angeles (which I was managing while attending school). He offered me a position at Santa Anita.

Elite equestrian sport, racing and non-racing alike, became the rest of my distinctly non-elite life. And, I venture to say, my fellow non-elites in these sports vastly outnumber the elites.

Almost all trainers, jockeys and racing labor on the backstretch, who make the game go from hour to hour, day to day, month to month, and year to year, weren’t elite when they started out, at least by any definition except the one that counts: their merit, their specialized skills, and their commitment to horses and the sport. I remember how moved I was a decade ago when one of international racing’s most elite trainers got choked up when describing how it felt to be appointed a director of an esteemed racing association. “I’m just a trainer,” he said, as though his accomplishments and expertise didn’t qualify him to rub shoulders and contribute to deliberations alongside wealthy and powerful elite decision-makers. They did. And they do.

In this greatest of all sports . . . where the interdependence of all its critical components is its essence . . . elites of accomplishment and merit, like him, comfortably perform alongside all the other elites, including those of birth, inherited or self-made wealth and royalty.

Horses have brought us all together, and many of us have been lucky enough to know—and be appreciated by—some of the world’s most famous personages.

So it was when Victor Espinoza, the self-proclaimed “luckiest Mexican on Earth,” won the Triple Crown, and later had occasion to meet and joke with Queen Elizabeth II at Royal Ascot. Doesn’t his story sum it up? And remind most of us where we came from?

The eleventh of twelve children, born on a dairy farm in Tulancingo, Hidalgo, growing up to work in a manufacturing plant and the stables, Victor drove a bus to pay for jockey school. Anyone who has endured Mexico City traffic knows the elite skills that must have been required! He aspired to more; his skill and determination resulted in successes reserved for the very fewest of the world’s top athletes. As the famed Dr. Robert Kerlan – who treated athletes at the highest levels of every major sport – once observed, “pound for pound, jockeys are the greatest.”

When honored by the Edwin J. Gregson Foundation, which has raised over $6 million from the racing community in 20 years—of which 98% is dedicated to backstretch programs including scholarships for its children—Victor again cited his luck in achieving what he has without much school, as well as his amazement at the Gregson’s success in its scholarship program. Hundreds of backstretch community children have gone to college because of it—in fields ranging from mechanical engineering to biology, nursing, graphic design, criminal justice, life sciences, sociology and everything else.

A few are now even among the world’s elites in architecture and medicine. The backstretch teaches tenacity.

And isn’t that just one reason why her late Majesty the Queen loved horses, racing, and its community, above all her other pursuits?

Alan Balch - Inspiring Ascot

Although I’ve never been to Royal Ascot, I first went to the course in October 2012, for the second British Champions Day, where Frankel “miraculously” recorded his 14th straight and final win after having been left at the start of the rich Champion Stakes.

On a cold, damp day, with the going “soft, heavy in places,” a capacity crowd of 32,000 was in attendance, and somewhat uncharacteristically for the British (I was told), yelled itself crazy for Frankel’s super effort. Not to mention trainer Henry Cecil.

Actually, however, Ascot has a true capacity far in excess of that day’s attendance. In the most recent Royal meeting, in June this year, crowds of over 60,000 were there. The television coverage of the masses of humanity in the stands, the infield and the various enclosures all along the mile straight, the paddocks, and on both ends of the strikingly beautiful permanent stands, gave any racing fan a thrill.

At the Cheltenham Festival for jump racing in March this year, attendance over four days ranged from 64,000 to 74,000 . . . “almost capacity,” according to management. And that left the media speculating about possibly adding a fifth day to its schedule, “like Royal Ascot.”

I was in London myself this year, late in March, amazed (and pleased) to see abundant advertising for Royal Ascot almost everywhere I went. Even though Opening Day was over two months away! Track managements in Britain clearly don’t take such attendance figures for granted . . . they believe in strong promotion and marketing, at least for their major racing, and undoubtedly their commercial sponsors (of which there are many high-profile brands) do as well.

What I see here in American racing attendance is virtually the opposite. And it’s a grave concern. Have we given up trying to persuade fans to go to the races?

The exceptions here seem to be the Triple Crown races, Breeders’ Cup, some Oaklawn days, the short summer meetings at Del Mar and Saratoga, and the two short Keeneland sessions. As one of racing’s dinosaurs, I admit to living in the past. But when I joined Santa Anita in 1971, I was told by one of racing’s most authoritative figures that I’d never see a crowd of 50,000 at our track again: “Those days are long gone.” Within five years, however, the Santa Anita Handicap, Derby and Opening Day were regularly drawing well over 50,000. More importantly, our daily average attendance 15 years later, over 17 weeks of 5 days each, peaked at just under 33,000 in 1986. And that was when announced attendance in California was scrupulously honest and audited.

I mention this because now I hear the old pessimism again, all the time, walking through the nearly vacant quarter-mile long stand at Santa Anita . . . that the days of regular big crowds at race tracks, actually any real crowds at all, are long gone. The reasons cited are obvious: Internet, satellite and telephone betting, pervasive competition from other sports and gaming, and the proliferation of all sorts of simulcasting—all disincentives for going to the races.