Young racehorse development through the lens of biotensegrity and fascia science

The debate surrounding the appropriate age to commence racehorse training remains a contentious topic. Advocates of traditional biomechanical models argue that training at 18 months is premature, as a horse's skeletal system does not reach full maturity for several more years. However, skeletal development alone presents a limited perspective. I would like to introduce another perspective from a rising research field. Through the lens of biotensegrity and fascia science, a more comprehensive approach emerges—one that considers the interconnectedness of a horse’s entire physiological system. Well-structured training at a relatively young age can support the holistic development of the racehorse, fostering both physical and psychological adaptability.

The Influence of gravity and early adaptation

From the moment a foal is born, it must quickly adapt to the force of gravity. Passage through the birth canal initiates its structural alignment, and within hours, the foal is standing and moving independently. Foals are born with predominantly fast muscle fibres (2X). The ability to travel up to seven kilometers daily alongside its dam is a testament to the foal’s inherent adaptability. This early exposure to movement and environmental stimuli plays a crucial role in its physiological and neurological development.

Challenging traditional views on skeletal maturity

This article seeks to introduce an alternative perspective on how the horse interacts with gravity, incorporating the principles of biotensegrity and fascia. It is important to note that most research is done on corpses and the fascia dries out almost directly after the circulation stops. Traditionally, equine skeletal maturation has been the primary concern regarding the timing of racehorse training. However, a singular focus on bone development overlooks the adaptability of connective tissues and the overall structural integrity of the horse. All young horses as an adaptation to their environment are in a critical phase of learning and adaptation—both physically and mentally—which must be accounted for in any training approach.

Veterinary discourse on skeletal maturity presents conflicting perspectives. Veterinarian Chris Rogers asserts that the skeleton of a two-year-old Thoroughbred is sufficiently developed for training, drawing parallels to human child development. Conversely, Dr. Deb Bennett posits that full skeletal maturity does not occur until six to eight years of age regardless of breed. All horses go through almost the same skeletal development phases, although thoroughbreds are extremely adapted through breeding to grow much quicker. While Bennett’s perspective has been widely accepted, Rogers’ viewpoint aligns with the practical realities of racehorse development, supporting the industry’s traditional training timelines.

Flat racehorses typically begin training at around 18 months of age. At this stage, their skeletal and connective tissues are still developing, as research consistently shows. Cartilage, bones, muscles, and ligaments undergo intensive growth and adaptation. Every experience the young horse encounters contributes to its physiological and neurological development, shaping its ability to perform the tasks expected of a racehorse. Training at a young age offers several advantages, as young horses are highly receptive and adaptable. As explored later in this article, their connective tissues develop in response to the challenges they are exposed to, reinforcing their structural integrity over time.

Racehorse training inherently involves a selection process. Horses that do not meet performance expectations within the first few seasons are often retired from racing by the age of three or four, making way for new yearlings. Those that demonstrate both speed and durability may continue competing well into their later years. Those are often geldings. Mares and stallions that show promise may transition into breeding programs. The rest, if their foundational training has been well-structured, can adapt successfully to second careers as riding horses, often becoming ideal partners for young equestrians at the start of their horsemanship journey.

Tensegrity principles

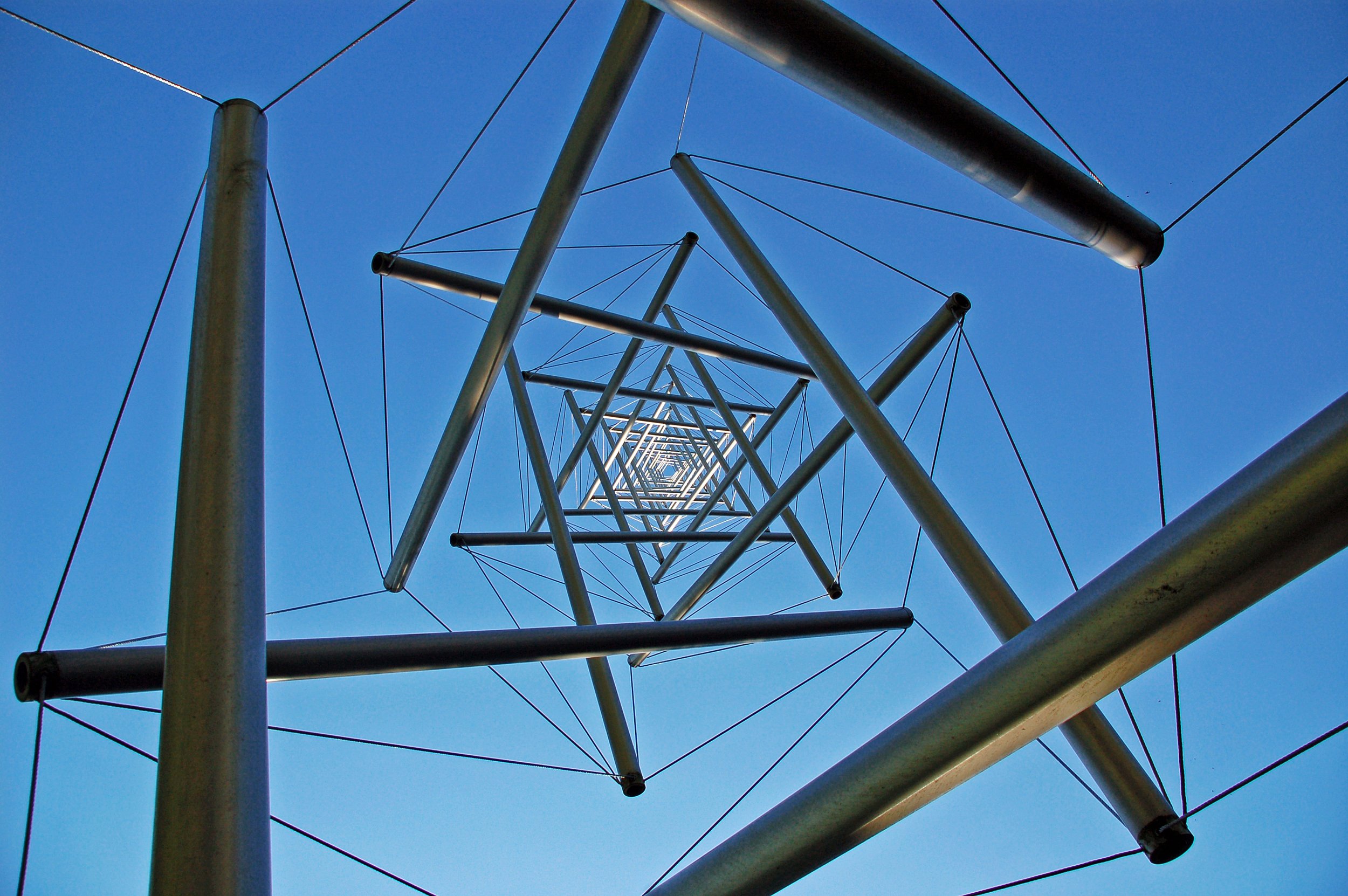

Tensegrity (tensional integrity) is a structural principle that explains how forces of tension and compression interact to create stability in a system. Originally coined by architect and engineer Buckminster Fuller, tensegrity has been widely applied in biological systems, including human and equine anatomy.

The role of fascia and biotensegrity in equine development

A traditional biomechanical view perceives the horse's skeleton like a rigid brick wall—if one part weakens, the entire structure becomes vulnerable to collapse. In contrast, a tensegrity-based perspective views the horse as a dynamic suspension bridge, where forces are distributed across an interconnected network of fascia, tendons, and ligaments. In this model, the skeleton is not a rigid load-bearing framework but rather ‘floats’ within the fascial system, allowing for adaptability, resilience, and efficient force distribution.

Biotensegrity highlights the balance between tension and compression within the body. In equine anatomy, the skeleton functions as a stabilizing framework, while fascia, tendons, and ligaments manage dynamic forces. Fascia, composed predominantly of collagen, exists in various densities, from loose connective tissue that facilitates muscle glide to the more rigid structures forming tendons and bones. This complex, fluid-filled network plays a crucial role in maintaining stability, distributing forces, and mitigating the impact of training.

Training influences the structural adaptation of connective tissues. Properly executed, it can enhance durability and resilience, reinforcing ligaments and tendons much like steel cables under controlled tension. Understanding the dynamic interplay between muscle, fascia, and skeletal development allows for training methods that optimise long-term soundness and performance.

Fascia

One of the most abundant proteins in the body is collagen, which forms connective tissue in all its various forms—from loose fascia, which separates muscles, to denser collagen structures that align with the direction of force and develop into tendons, ligaments, or bone. One of the key functions of loose fascia is to allow muscles to glide smoothly against one another without friction when one muscle contracts and another stretches.

Loose fascia consists of a collagen network, with its spaces primarily filled with water and hyaluronic acid. It is a highly hydrated structure—young horses are composed of approximately 70% water. Imagine a water-filled balloon, where the skin acts as the boundary between the internal and external environments. During fetal development, collagen structures form first, providing the framework within which the organs develop. Collagen, a semiconductive protein, relies on water to function optimally.

The water-rich environment surrounding fascia transforms it into an extraordinarily intelligent communication network. Its function is highly responsive to the body's pH levels, adapting moment by moment to internal conditions. As the central hub for force transfer and energy recycling, fascia provides immediate balance and support—often operating beyond the constraints of the nervous system.

Fascia's remarkable adaptability is rooted in its multifaceted properties. It is nociceptive, meaning it is capable of detecting pain and harmful stimuli, alerting the body to potential injury or strain. It is also proprioceptive, enabling the body to sense its position and movement in space, which aids in maintaining coordination and balance. Additionally, fascia exhibits thixotropic properties—allowing it to shift between a gel-like state and a fluid-like state depending on movement, which enhances flexibility and responsiveness.

Finally, fascia demonstrates piezoelectric properties, generating electrical charges in response to mechanical stress, playing a crucial role in cellular signaling and tissue remodeling. These combined characteristics enable fascia to dynamically adjust to both mechanical and biochemical stimuli, ensuring optimal function in response to ever-changing internal and external conditions."

Fascia has no clear beginning or end; it distributes pressure and counteracts the force of gravity.

The biotensegrity of equine locomotion and how horses rest while standing

Horses possess a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that allows them to rest while standing, a capability underpinned by the principles of biotensegrity. This structural efficiency is achieved through an intricate network of tendinous and ligamentous locking mechanisms working in harmony with the skeleton.

In the forelimbs, the extensor and flexor tendons engage to stabilise the skeletal structure, minimizing muscular effort. Meanwhile, in the hind limbs, a specialised locking mechanism is activated when the patella (kneecap) is positioned against a flat section on the femur just above the stifle, further contributing to this passive support system.

This adaptation allows horses to conserve energy while remaining poised for rapid movement. In the event of sudden danger, they can instantly transition from rest to flight, ensuring their survival—an essential trait for both wild and athletic performance. The efficiency of this natural support system exemplifies the principles of biotensegrity, where tension and compression forces work in balance to maintain structural integrity with minimal effort.

The head and neck function as critical balancing structures, comprising approximately 10% of the horse's total body weight. The forelimbs bear roughly 60% of the body’s weight, but true structural support originates from above the elbow joint. The spine, a central element of equine biomechanics, acts as a suspension system. The primary function of the equine spine is to support the internal organs, a role that also enables the horse to carry a rider.

This structural foundation ensures both stability and balance, allowing for efficient movement and performance under saddle. The propulsion generated by the hind legs is efficiently transferred to the forehand through the back muscles, which are reinforced with robust connective fascia plates, ensuring optimal movement and stability. This structural complexity underscores the need for a training regimen that respects the developmental timing of multiple interrelated systems beyond just the skeletal framework.

Risks and adaptations in young racehorses

While early training offers advantages in developing resilience in young racehorses ( they have a high percentage muscle fiber 2X), it also presents risks. The spinal column, particularly the lumbar-sacral junction, endures significant forces during high-speed galloping. Without appropriate conditioning, the vulnerability of these structures can lead to pathologies such as kissing spines or pelvic instability. Their growth plates remain open, making them more susceptible to the impact of high-speed forces, compensatory adaptations to early training stress may manifest as different maladaptive adaptations in connective and skeletal tissues, potentially diminishing long-term performance capabilities.

However, when managed correctly, the high adaptability of collagen structures in young horses allows for positive adaptation. Training introduces controlled tensile and compressive forces, fostering the development of strong, functional connective tissues. The challenge lies in striking the right balance between stimulus and recovery to optimise long-term soundness and athletic potential.

The value of tacit knowledge in training practices

Experienced trainers have an intuitive understanding of the complex relationships between tissues and biomechanics, a knowledge that is often honed through years of careful observation and practical experience. This tacit expertise is fundamental in shaping training strategies that take into account the horse’s overall development. A comprehensive training program should not only focus on the maturation of the horse’s bones but also prioritise the adaptive growth of fascia, ligaments, and muscles. By doing so, trainers ensure that young racehorses develop in a way that is aligned with their evolving physiological capabilities, promoting balanced growth and minimizing the risk of injury. This holistic approach allows for the optimal performance and longevity of the racehorse, fostering a more sustainable path toward peak athleticism.

Conclusion: a holistic perspective on racehorse development

The evolution of equine training methodologies has greatly benefited from recent advancements in scientific understanding, offering a more refined approach to racehorse development. By incorporating biotensegrity principles into training programs, a more comprehensive view of the horse’s physical structure and function emerges, shifting the focus from skeletal maturity alone to a broader understanding of the interconnected roles of fascia, connective tissues, and adaptive biomechanics. This shift in perspective allows for the cultivation of healthier, more resilient athletes who can perform at their peak while minimizing the risk of injury.

With equine welfare at the forefront, adopting a holistic approach to racehorse development—one that blends cutting-edge biomechanics, physiological insights, and traditional training wisdom—will pave the way for more sustainable, ethical practices within the industry. Such an approach not only enhances performance in the short term but also ensures the longevity and well-being of racehorses throughout their careers. Ultimately, by embracing this integrated perspective, the racing industry can promote a future where both the performance and welfare of horses are prioritised, leading to a more ethical and effective standard of training.

---

Extra Reading References

- Levin, S. (Biotensegrity: www.biotensegrity.com)

- Clayton, H. M. (1991). *Conditioning Sport Horses*. Sport Horses Publications.

- Adstrup, S. (2021). *The Living Wetsuit*. Indie Experts, P/L Austrasia.

- Schultz, R. M., Due, T., & Elbrond, V. S. (2021). *Equine Myofascial Kinetic Lines*.

- Bennett, D. (2008). *Timing and Rate of Skeletal Maturation in Horses*.

- Rogers, C. W., Gee, E. K., & Dittmer, K. E. (2021). *Growth and Bone Development in Horses*.

- Ruddock, I. (2023). *Equine Anatomy in Layers*.

- Myers, T. W. (2009). *Anatomy Trains (2nd Edition)*. Churchill Livingstone.

- Diehl, M. (2018). *Biotensegrity*.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). *The Structure of Scientific Revolutions*. University of Chicago Press.

- Tami Elkyayam Equine Bodywork

Alfredo Marquez: Raised at the Racetrack

Lions and Tigers and Bears, OH MY!

Being “raised at the racetrack” takes on the true meaning of the phrase when one is referring to trainer Alfredo Marquez. The California conditioner, now 75, was introduced to the backside of a racecourse when he was just a month old.

Article by Annie Lambert

The old Agua Caliente Racetrack in Tijuana, Mexico, has tethered Alfredo Marquez to Thoroughbred racing and his roots in Mexico for a lifetime. He spends off days from his California training barns at his home in Tijuana, a gated community literally built in an area where Caliente’s old barns once stood.

“That’s where I still live,” Marquez affirmed. “I still live basically in the barn area. We have a gated community where they tore out like six barns; there is a fence between the other barns and our homes. Most of the old barns are still there. They got bears, lions, tigers, elephants and a few Andalusian horses…all the barns are occupied by different kinds of animals.”

The “old” Caliente hosted Thoroughbred horse racing between late 1929 until the early 1990s, a golden era for the racecourse. Greyhound racing seven nights a week now satisfies the live racing obligation needed to continue their simulcast signal.

But, how did wild animals come to replace racehorses in the old stable area?

Jorge Hank Rhon was raised in Mexico by his wealthy, powerful German immigrant parents. Before taking over the Agua Caliente track in 1984, he moved to Tijuana from Mexico City where he had been an exotic animal trader. Rhon owned nine pet shops, six veterinary clinics and a dolphin show.

Before moving, he sold his businesses—many of which were paid for in part with exotic animals: rhino, leopards, cougars, panthers, tigers and even the Andalusians. During the evening horse races, Caliente spectators were able to watch some of the menagerie roaming on the infield.

Rhon still owns Grupo Caliente, Mexico’s largest sports betting company.

What does Rhon do with the animals? “Feeds ‘em,” Marquez said with a laugh. “It’s like a small private zoo for the owner of the track. He’s an animal lover.”

Rearview Mirror

The Marquez family has been a part of Caliente’s storied history—as well as California tracks—for several generations; nearly every Marquez family member is or has been a racetracker. They worked at tracks like Santa Anita, Hollywood Park, Golden Gate, Bay Meadows and mostly Del Mar “because it’s only a jump from Tijuana.”

Marquez’s brother, Saul Marquez, is currently a jockey valet for Juan Hernandez (current leading rider at Santa Anita), Franklin Calles and Ricardo Gonzalez at Santa Anita. Saul’s son, Saul Jr., was a jockey agent for a long time and worked sales at horse auctions. He now runs his own business as an independent trucker. A nephew, Victor Garcia, is the son of former jockey Juan Garcia and is also a trainer at Santa Anita.

“A lot of my Tijuana family, most of them, worked at the track,” Marquez said. “They were grooms, trainers, assistant trainers, pony boys, exercise riders and jockeys.

From an early age, Marquez, worked within the Thoroughbred racing industry in many capacities. His one wish from the beginning was to own a racehorse.

“My main goal was to own horses,” Marquez said. “That was it from day one, since I was born. I had a horse when I was young. My dad bought me a horse for my birthday when I was seven. I sold it when I was eight. It was a riding horse, a filly. In those days [in Tijuana], there were no cars. You walked to school, which was not too far from home, and you walked to the racetrack.”

Marquez claimed his first horse for $1,000 in 1964, at the age of 16. He took a horse named Social Book off Wes Cain and the owner, Mrs. Morton. Those connections claimed the horse back just three weeks later for $1,400.

“They sent him up north, and he made like $50,000,” Marquez said of Social Book.

His second claim was Cahill Kid, trained by then leading trainer, C.L. Clayton.

“That was a very, very nice horse—a stud,” Marquez recalled. “I ran him six times and had four wins, a second and a third. I lost him for $1,600. I think all together I made about $7,800 in three months, which was a lot of money then and a lot more nowadays.”

“I bought a Chevrolet Impala in Mexico with the money,” Marquez added. “I also bought property—a lot that I built apartments on later—like in 1968, I finished building.”

While he was claiming his first horses, Marquez worked for trainer L.J. Brooks until he was “17 or 18,” before going to work for a smaller trainer with only a couple of horses. Marquez remembers one really nice gray horse he handled, The Roan Clown—a two-time winner at Pomona.

Motivos & More

The English translation for motivo is “a reason for doing something, causing or being the reason for something.” Motivos was a horse perfectly named to become the young trainer’s favorite horse—a horse he owned himself.

“I had Motivos, a Mexican bred,” Marquez explained. “He ran twice in California, then I took him back to Mexico, to Tijuana. In one year, he was Sprinter of the Year, Miler of the Year and Horse of the Year. In the 1980s, he took everything—running from 5 ½ furlongs, a flat mile, a mile and an eighth and mile and a quarter.”

“What I admired about that horse was, when he goes short, he goes to the lead and they never catch him,” the trainer added. “And when you go a mile or more, he breaks on top, and he lays back second or third; he doesn’t go past, then he makes a run. He’s just like a human. I’ve never seen any horse like him, ever. He was amazing—amazing—and he was so smart.”

Motivos even ran second in the $250,000-added Clásico Internacional del Caribe (Caribbean Derby), the most important Thoroughbred black-type stakes race in the Caribbean for three-year-olds. The Caribe is for the best colts and fillies from the countries that are members of the Confederación Hipica del Caribe; the race rotates between those countries each year.

In 1988, the Caribe was held at Caliente. Marquez ran Don Gabriel (MEX) and Joseph (MEX), both colts owned by Cuadra San Gabriel. “Don Gabriel won it, and Joseph ran second,” Marquez said. “Nobody had ever run one-two before.”

With Equibase earnings of $8,384,323, Marquez has trained multiple graded-stakes winners over the years.

Melanyhasthepapers (Game Plan) was purchased as a yearling for $40,000 out of the Washington sale at Emerald Downs by owners Ron and Susie Anson. They named the colt after Melanie Stubblefield who handled all the registration papers at Santa Anita for decades.

Melanyhasthepapers

“I bought the colt off the Ansons for $40,000 when they retired from owning horses,” Marquez remembered. “He ended up being a stake horse.”

Melanyhasthepapers earned $311,152 between 2003 and 2006 including five wins; the horse won the Cougar II Stakes at Hollywood Park, ran second in the All-American Handicap (G3) at Golden Gate and third in Santa Anita’s Tokyo City Handicap (G3).

Tali’sluckybusride

The Ansons also purchased Tali’sluckybusride as a yearling out of the 2000 Washington sale for $23,000. The Delineator filly went on to win the Oak Leaf Stakes (G1) and was third in both the Hollywood Starlet Stakes (G1) and Las Virgenes Stakes (G1). She ultimately earned $245,160.

Ron Anson obviously had an eye for a runner. “Ron was pretty good at claiming horses and buying them privately,” Marquez said. “He died last year.”

Marquez-trained stakes horses include: Martha and Ray Kuehn’s - Irish (Melyno (IRE)) that won the Bay Meadows Derby (G3); Anson’s - Irguns Angel (Irgun) topped the A Gleam Handicap (G2), ridden by Eddie Delahoussaye; and their gelding, Peach Flat (Cari Jill Hajji), was triumphant in the All-American Handicap (G3).

“We claimed Peach Flat up north at Bay Meadows for $20,000—his second start,” Marquez pointed out. “We won seven races with him.”

Tali’sluckybusride

The Border & Beyond

Marquez used to check on sales yearlings at Gillermo Elizondo Collard’s Rancho Natoches in Sinaloa, Mexico. In 1989, between inspecting sales yearlings, he spotted a mare with a baby at her side that caught his eye.

“It’s a big, beautiful farm,” Marquez pointed out. “I’m checking those horses, and I see this mare with a little baby—probably five months old. The owner bought the mare at Pomona in foal to La Natural; this is that baby.”

When Marquez inquired about buying the La Natural, the owner informed him that the colt was Mexican-bred, not Cal-bred. The trainer wrote a check for what had been paid for the mare – he thinks $6,000 – and asked that the baby be delivered to him at Caliente as a two-year-old.

“I waited almost two years,” Marquez said. “I got him and two other horses [for training] delivered to quarantine at Caliente Racetrack. I broke him at Caliente along with the other two.”

The La Natural colt, named Ocean Native, made his first start for Marquez at Del Mar in 1991 in a $50,000 maiden-claiming race with Kent Desormeaux riding. The dark bay gelding won going away first time out. Less than three weeks later, Desormeaux rode him back for a second win in the Saddleback Stakes at Los Alamitos.

After running up and down the claiming ranks, Marquez lost Ocean Native on a win for a $25,000 tag at Del Mar in 1993. The durable gelding was hardly finished, however. He ultimately ran fourth in his last race with a $3,000 tag in 1999 at Evangeline Downs. Ocean Native ran 77 times, won 12 races and earned $155,194.

One of the babies that arrived at Caliente with Ocean Native was a Pirate’s Bounty named Tajo. Marquez remembered the colt as “a really nice horse that broke his maiden at Del Mar; and he also won an allowance at Hollywood Park second time out.”

The Anson’s Lord Sterling (Black Tie Affair [IRE]) took his connections on a two-week trip to Tokyo, Japan, for the very first running of the Japan Cup Dirt (G1).

Lord Sterling

In late 1998, Marquez claimed Lord Sterling from Jerry Hollendorfer at Golden Gate, in just his second out for $50,000. The horse had run second his first out there in a $25,000 maiden claimer.

Over the next two years, Lord Sterling won four additional races for Marquez including a listed stake at Santa Rosa. In October of 2000, the horse finished second in the Meadowlands Cup Handicap (Gr.2) as the longest shot on the board. That effort punched his ticket to Japan.

“We were invited and almost won the race,” Marquez recalled with enthusiasm. “[Lord Sterling] ran a big, big third in a $2.5 million race. We went back the following year with another of Anson’s horses, Sign of Fire.”

Sign of Fire (Groomstick), a graded-stakes placed runner, unfortunately bled and ran out of the money.

“Tokyo is like five racetracks in one,” Marquez said. “They got turf, dirt, a bigger turf and steeplechase. They only ran Saturday and Sunday. But, like on Friday, you see hundreds of people sleeping on the sidewalk so they can go into the races. They limit it to, I think, 100,000 people. They gamble, and I mean they really gamble…

“You know what’s really amazing? When the horses come out of the gate, everybody gets quiet until the race is over; it is total silence.”

Love & Compassion

Marquez commutes between his Tijuana home and Southern California tracks—roughly a three-hour drive to Santa Anita. He spends a few days each week in Mexico, depending on his schedule—a routine that has sustained him for 40 years.

He and his wife, Angela, a certified public accountant, have four children. His son and three daughters were not encouraged to pursue racetrack careers, according to their father. The kids are smart, educated and on the road to bright futures.

“I wanted them to buy property instead of horses,” Marquez explained. “Real estate—that’s where the money is. Horses are fun, and when you race, you enjoy as much as possible; but you can’t win every time.”

Marquez’s son Jonathon graduated from San Francisco State University. He and Angela recently traveled to Boston to see Jonathon receive his Masters Degree in speech therapy. Their daughter Brenda graduated from Grand Canyon University of Phoenix with a Masters in Education and is teaching. Daughter Georgette teaches in San Diego and another daughter, Yvette, evaluates autistic children.

Although Marquez encouraged his children to pursue education and positive careers, he loves “everything racetrack,” especially training and owning horses. He also takes compassionate aftercare of his trainees.

Marquez claimed Starting Bloc (More Than Ready) in the spring of 2018 for $50,000 out of the Richard Mandella barn. The colt ran 15 times for Marquez, picking up 11 checks, including three wins.

When his horses show signs of being at the end of their careers, Marquez has a solution.

“We’ve still got Starting Bloc up at the ranch in Nevada,” Marquez said. “My owner, Robert Cannon’s son, Michael, has a big, 5,000 head cattle ranch up there. [Retired horses] have a whole big field. It’s their home for life.”

Lil Milo (Rocky Bar) is another of Marquez’s horses headed to the ranch for life. “He won the Clocker’s Corner Stakes the last time he ran,” the trainer pointed out. “His owner Dr. [Jack] Weinstein died right after the horse won, like a month later.”

Most of his career, Marquez trained a barn of 40 to 45 horses. Most of his owners became like family; and as they aged and drifted out of the horse business or passed on, Marquez also slowed down.

“When they retired, I retired,” he explained. “Right now, I’ve got the smallest barn as possible—only six to eight horses. But I’m going to stay in business until I drop. You have to have your mind working all the time. I don’t want to stop.”

Marquez recalls all of the many great horses he has trained with enthusiasm and can rattle off stories of every one. As he says, “I’ve been so lucky to own horses. They are still in my memory, in my heart.”