Walter Rodriguez

Article by Ken Snyder

We see them every day in the news—men, women and children trudging north across Mexico, searching for a brighter future in the best bet on the globe: the United States. For most Americans, we don’t foresee them winning that bet like our ancestors did generations ago. The odds against them are huge.

But long shots do come in.

Walter Rodriguez was 17 years old when he pushed off into the Rio Grande River in the dark from the Mexican bank, his arms wrapped around an inner tube to cross into the U.S. The year was 2015, which differs from 2023 only in scale in terms of illegal immigration. He crossed with two things: the clothes on his back and a desire to make money he could send home. How he ended up making money and yes, quite a bit of it at this point, meant overcoming the longest odds imaginable and, perhaps, a lot of divine intervention.

Getting here began with a long six-week journey to the border from Usulutan, El Salvador, conducted surreptitiously and not without risk and a sense of danger.

His family paid $5,000 to a “coyote” (the term we’ve all come to know for those who lead people to the border).

“They would use cars with six or eight people packed in, and we would drive 10 hours. We’d stay in a house. Next morning, they would drive again in different cars, like a van; and there would be more people in it.”

Three hours into a trek through South Texas brush after his river crossing, the border patrol intercepted him. He first went to jail for several days. After that, he was flown to a detention center for illegally migrating teenagers in Florida with one thread tying him to the U.S. and preventing deportation: an uncle in Baltimore. After a month there and verification that his uncle would take him in, Walter flew to Baltimore and his uncle’s home in Elk Ridge, Maryland. From El Salvador, the trip covered about 3,200 miles.

He worked in his uncle’s business, pushing, lifting and installing appliances, doing the work of much larger men despite his diminutive size. More than a few people marveled at his strength. Ironically, and what he believes divinely, more than a few people unknowingly prophesied what was to come next for Rodriguez. Particularly striking and memorable for Walter was an old man at a gas station who looked at him and said twice. “You should be a jockey.”

For Walter, the counsel was more than just a chance encounter with a stranger. It is a memory he will carry his whole life: “This means something. I think God was calling me.”

Laurel Park just happened to be 15 minutes from where Rodriguez lived in Elk Ridge.

Whether by chance or divine intervention, the first person Rodriguez encountered at Laurel was jockey J.D. Acosta. Walter asked in Spanish, his only language at the time, “Where can I go to learn how to ride? I would like to ride horses.”

He couldn’t have gotten better direction. “I’ve got the perfect guy for you,” said Acosta. That was Jose Corrales, who is known for tutoring and mentoring young jockeys—three of whom have won Eclipse Awards as Apprentice of the Year and a fourth with the same title in England. That was Irish jockey David Egan who spent a winter with Corrales in 2016 before returning to England. He piloted Mishriff to a win in the 2021 Saudi Cup.

“This kid—he came over out of the blue to my stable,” recalled Corrales. “He said, ‘I’m so sorry. Somebody told me to come and see you and see if maybe I could become a jockey.’”

Corrales sized up Rodriguez as others had, echoing what others had told him: “You look like you could be a jockey.”

The journey from looking like a jockey to a license, however, was a long one; he knew nothing about horses or horse racing.

Perhaps surprisingly for someone from Central America, where horses are a routine part of the rural landscape, Rodriguez was scared of Thoroughbreds.

He began, like most people new to the racetrack, hot walking horses after workouts. Corrales also took on the completion of immigration paperwork that had begun with Rodriguez’s uncle.

His first steps toward becoming a rider began with learning how to properly hold reins. After that came time on an Equicizer to familiarize him with the feel of riding. The next step was jogging horses—the real thing.

“He started looking good,” said Corrales.

“I see a lot of things. I told him, ‘You’re going to do something.’”

Maybe the first major step toward becoming a jockey began with the orneriest horse in Corrales’ barn, King Pacay.

“I was scared to put him on,” said Corrales. In fact, the former jockey dreaded exercising the horse, having been “dropped” more than a few times by the horse.

Walter volunteered for the task. “Let me ride him,” Corrales remembered him saying before he asked him, “Are you sure?”

Maybe before the young would-be jockey could change his mind, Corrales quickly gave him a leg up.

“In the beginning, he almost dropped him,” said Corrales, “but he stayed on and he didn’t want to get off. He said, ‘No, I want to ride him.’”

“It was like a challenge I had to go through,” said Rodriguez, representing a life-changer for him—a career as a jockey or a return to his uncle’s business and heavy appliances.

The horse not only helped him overcome fear but gave him the confidence to do more than just survive a mean horse.

“I started to learn more of the control of the horses from there.”

Using the word “control” is ironic. In Rodriguez’s third start as a licensed jockey, he won his first race on a horse he didn’t control.

“To be honest, I didn’t know what I was doing. I just let the horse [a Maryland-bred filly, Rationalmillennial] do his thing. I tried to keep her straight, but I didn’t know enough—no tactics, none of that. We broke from the gate, and I just let the horse go.”

Walter Rodriguez receives the traditional dousing from fellow jockey Jorge Ruiz after winning his first career race at Laurel Park, 2022.

It was the first of 11 victories in 2022 in six-and-a-half months on Maryland tracks and then Turfway Park in Kentucky. Earnings were $860,888 in 2022; and to date, at the time of writing not quite halfway through the year, his mounts have earned a whopping $2,558,075. Most amazing, he led Turfway in wins during that track's January through March meet with 48. He rode at a 19% win rate.

Next was a giant step for Rodriguez: the April Spring meet at Keeneland, which annually draws the nation’s best riders.

He won four races from 39 starts. More significant than the wins, perhaps, is the trainer in the winner’s circle with Rodriguez on three of those wins: Wesley Ward.

How Ward came to give Rodriguez an opportunity goes back to 1984, the year of Ward’s Eclipse Award for Outstanding Apprentice. One day on the track at Belmont, he met Jose Corrales. On discovering Corrales was a jockey coming off an injury and battling weight, Ward encouraged him to take his tack to Longacres in Seattle. The move was profitable, leading to a career of over $4.4 million in earnings for Corrales and riding stints in Macau and Hong Kong.

The brief exchange on the racetrack during workouts began a friendship between Corrales and Ward that continued and is one more of those things that lead to where Rodriguez is today as a jockey.

Corrales touted Rodriguez to Ward, who might be the perfect trainer to promote an apprentice rider. Ward’s success as a “bug boy” eliminates the hesitation many of his owners might have against riding apprentices.

He might be the young Salvadoran’s biggest fan.

“I can’t say enough good things about that boy. He’s a wonderful, wonderful human being and is going to be a great rider.”

He added something that is any trainer’s sky-high praise for a jockey: “He’s got that ‘x-factor.’ Horses just run for him.”

Corrales, too, recognizes in Rodriguez a work ethic in short supply on the race track. “A lot of kids, they want to come to the racetrack, and in six months they want to be a jockey. They don’t learn horsemanship,” said Corrales. “You tell Walter to do a stall, he does a stall. You tell him to saddle a horse, he saddles the horse. He learns to do what needs to be done with the horses.

“He’s got the weight. He’s got the size. He’s got a great attitude. He works hard.”

Ward was astonished at something the young man did when one of his exercise riders didn’t show up at Turfway one morning: “He was leading rider at the time but got on 15 horses that morning and that’s just one time.“ Ward estimated Rodriguez did the same thing another 25 times.

“He’ll do anything you ask; he’s just the greatest kid.”

Ward recounted Rodriguez twice went to an airport in Cincinnati to pick up barn workers flying back to the U.S. from Mexico to satisfy visa requirements. “He’d pick them up at the airport from the red-eye flight at 4:30 in the morning and then drive them down to work at Keeneland.”

Walter on Wesley Ward’s Eye Witness at Keeneland.

With Rodriguez’s success, talent is indisputable, but Corrales also credits a strong desire to reach his goal combined with an outstanding attitude. Spirituality, too, is a key attribute developing in extraordinary circumstances in his home country.

When Rodriguez was three years old, his father abandoned him and his mother. As for her, all he will say is, “She couldn’t raise me.” His grandmother, Catalina Rodriguez, was the sole parent to Rodriguez from age three.

He calls his grandmother “three or four times a week,” and she knows about his career, thanks to cousins that show her replays of his races.

Watching him leave El Salvador was difficult for her, but she saw it as necessary to the alternative. He credits her for giving him “an opportunity in life. Otherwise, I would be somebody else, doing bad things back at home.”

Surprisingly, her concerns for her grandson in the U.S. were more with handling appliances than 1,110-pound Thoroughbreds.

“When I was working with my uncle, she wasn’t really happy; she wasn’t sure about what I was doing.

“But I kept saying to her, let’s have faith. Hopefully, this is going to be okay. Now she realizes what I was saying.”

His faith extends to the latest in his career: riding at Churchill Downs this summer. “One day I got on my knees and I said to God, ‘Please give me the talent to ride where the big guys are.’“

Gratitude is another quality that seems to come naturally for Rodriguez. After the Turfway Park meet at the beginning of April, he flew back to Maryland to provide a cookout for everybody in Jose Corrales’s barn.

He also sends money to El Salvador, not only to his grandmother but to help elderly persons he knows back home. During the interview, he showed pictures of food being served to people in his village at his former church. At least a significant portion of that is financed by Rodriguez’s generosity.

“I love to help people. It will come back to you in so many ways. I’ve seen how it came back to me.”

According to Corrales, there have been discussions about a possible movie on Rodriguez, who just received his green card in June of this year.

“These days with immigration, crossing the border and all the trouble we’re having—to have somebody cross the border and have success, it’s a blessing,” Corrales said.

A blessing, for sure, but one that was meant to be. Walter encapsulated his journey and what happened after he went to Laurel Park with a passage from a psalm in the Bible: “The steps of a good man are ordered of the Lord.”

Personal preference - training from horseback or the ground

By Ed Golden

At 83, when many men his age are riding wheelchairs in assisted living facilities, Darrell Wayne Lukas is riding shotgun on a pony at Thoroughbred ports of call from coast to coast, sending his stalwarts through drills to compete at the game’s highest level.

Darrell Wayne Lukas accompanies Bravazo, ridden by Danielle Rosier

One of three children born to Czechoslovakian immigrants, Lukas began training quarter horses full time in 1967 at Park Jefferson in South Dakota. He came to California in 1972 and switched to Thoroughbred racing in 1978. Rather than train at ground level as most horsemen do, Lukas has called the shots on horseback lo these many years, winning the most prestigious races around the globe.

A native of Antigo, Wisconsin, he was an assistant basketball coach at the University of Wisconsin for two years and coached nine years at the high school level, earning a master’s degree in education at his alma mater before going from the hardwood to horses.

His innovations have become racing institutions, as his Thoroughbred charges have won nearly 4,800 races and earned some $280 million. They are second nature to him now.

“I’m on a horse every day for four to five hours,” said Lukas, who’s usually first in line. “I open the gate for the track crew every morning. I ride a good horse, and I make everybody who works for me ride one.

“My wife (Laurie) rides out most days. She’s got a good saddle horse. I make sure my number one assistant, Bas (Sebastian Nichols) rides, too.”

The Hall of Fame trainer is unwavering in his stance.

“I want to be close to my horses’ training, because I think most of the responses from the exercise rider and the horse are immediate on the pull up after the workout or the exercise,” Lukas said.

“I don’t want that response 20 minutes later as they walk leisurely back to the barn. I want it right there. If I’m working a horse five-eighths, and I have some question about its condition, I want to see how hard it’s breathing myself, before it gets back to the barn.

“I’ve always been on a pony when my horses train, ever since I started. I’ve never trained from the ground. If my assistants don’t know how to ride, they have to take riding lessons, and they’ve got to learn how to ride. I insist on them being on horseback.”

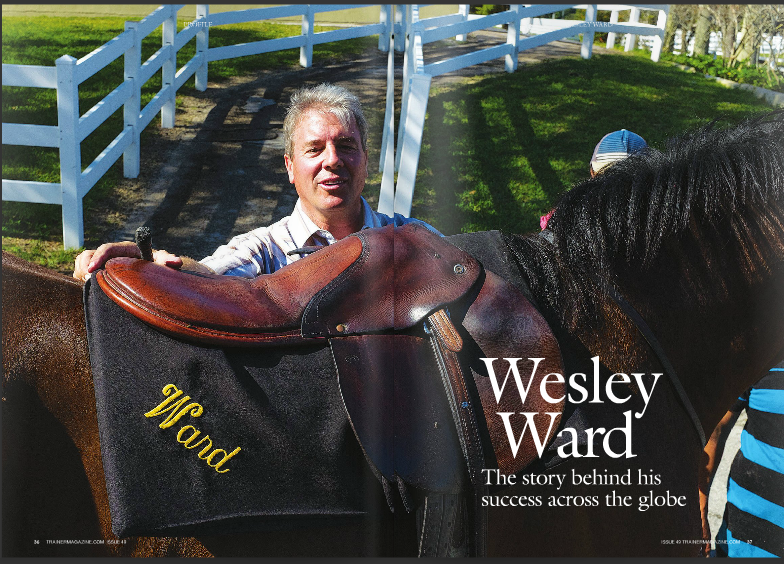

Wesley Ward, a former jockey and the 1984 Eclipse Award winner as the nation’s leading apprentice rider, is a landlubber these days as a trainer, yet has achieved plaudits on the international stage.

Wesley Ward

“I don’t think there’s any advantage at all on horseback,” said Ward, who turns 51 on March 3. “Look at (the late) Charlie Whittingham. “He’s the most accomplished trainer in history, I think, and he wasn’t on a pony . . . Everybody’s different. It’s just a matter of style. I can see more from the grandstand when the horses work.

“I like to see the entire view, and on a pony, you’re kind of restricted to ground level, so you can’t really tell how fast or how slow or how good they’re going.

“I like to step back and observe the big picture when my horses work. I can check on them up close when they’re at the barn. But all trainers are different. Some like to be close to their horses and see each and every stride. I’ve tried it both ways, and I like it better from an overview.”

Two-time Triple Crown-winning trainer Bob Baffert, himself a former rider, employs the innovative Dick Tracy method: two-way radio from the ground to maintain contact with his workers on the track.

Bob Baffert

“I used to train on horseback,” said Baffert, who celebrated his 66th birthday on Jan. 13, “but you can’t really see the whole deal when you’re sitting on the track. From the grandstand, you can see the horses’ legs better and you can pick up more.

“On horseback, you can’t tell how fast a horse is really going until it gets right up to you. That’s why I switched. I have at least one assistant with a radio who’s on horseback, and I can contact him if someone on the track has a problem.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (PRINT)

$6.95

Pre Breeders’ Cup 2018, issue 50 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Standing in the wings - Assistant Trainers

By Ed Golden

The term “second banana” originated in the burlesque era, which enjoyed its heyday from the 1840s to the 1940s.

There was an extremely popular comedy skit where the main comic was given a banana after delivering the punch line to a particularly funny joke. The skit and joke were so widely known that the term “top banana” was coined to refer to anyone in the top position of an organization.

The term “second banana,” referring to someone at a pejorative plateau, had a similar origin from the same skit. There would have been no Martin without Lewis, no Abbott without Costello, and no Laurel without Hardy.

Racing has its own version of second bananas, only they’re not in it for the yuks. They’re called assistants, and it’s a serious business.

Most of the laughs come in the winner’s circle, and if not outright guffaws, there at least have been miles of smiles for Hall of Fame trainer Jerry Hollendorfer and assistant Dan Ward, who spent 22 years with the late Bobby Frankel before joining Hollendorfer in 2007.

While clandestinely harboring caring emotions in their souls, on the surface, Frankel did not suffer fools well, nor does Hollendorfer. A cynic has said Ward should have been eligible for combat pay during those tours.

But he endures, currently with one of the largest and most successful barns in the nation, with 50 head at Santa Anita alone. Hollendorfer hasn’t won more than 7,400 races being lucky. It is a labor of love through dedication and scrutinization to the nth degree, leaving little or nothing to chance.

A typical day for the 71-year-old Hollendorfer and the 59-year-old Ward would challenge the workload of executives at any major corporate level. Two-hour lunches and coffee breaks are not on their priority list.

“I get to the track before three in the morning,” Ward said, “because we starting jogging horses at 3:30. It takes about a half-hour until we get every horse outside, check their legs, jog them up and down the road, and if we see something that will change our routine--the horse doesn’t look like it’s jogging right or if it’s got a hot foot--we’ll adjust the schedule.

“We won’t send a horse to the track without seeing it jog. We’ll watch all the horses breeze, and if something unexpected happens that we have to deal with, we diagnose it and take care of it. Meanwhile, we’re also going over entries and the condition book, making travel arrangements and staying current on out-of-town stakes and nominations.

“Each time a new condition book comes out, I go over it with Jerry, we agree on which races to run in, and then go out and try and find riders.

“I’ll ask him what claiming price we should run a horse for, but with big stakes horses, the owners have the final say. Jerry and I usually agree on the overnight races, but in some big stakes, it might take more time deciding which horses run in what races. All this consumes most of the day, plus doing the time sheets and the payroll.”

It’s a full plate even with a shared workload, but Ward is considering flying solo should a favorable chance come his way.

“I’m hoping to go on my own,” he said. “Right now, I’m in a very good position, but if the right opportunity comes along, or if Jerry one day decides not to train anymore, I would be qualified to take over. In the future, however, I definitely hope to train on my own.”

Despite his workaholic demeanor, Ward has found time recently to enjoy a slice of life in the domestic domain.

“I was married for a year on March 6 and it’s been the best time,” he said. “My wife (Carol) already had two kids, and now they’re our kids, and it’s really great.”

Ward is a worldly man with diversity of thought, traits Hollendorfer sought when he brought him on board.

“In my barn, I often give the reins to my assistants,” Hollendorfer said. “I like them to make decisions, so when I hired Dan Ward I told him that I wasn’t looking for a ‘yes man’ but for somebody who would state his opinion, and if he felt strongly about it, to stand his ground.

“I make the final decisions, but I want a person who is not afraid to make decisions and lets me know what’s going on when I’m not there. There’s not a successful trainer I know of who doesn’t fully have good support back at his barn, and that’s where I’m coming from.

“It’s not only Dan who makes important contributions, it’s (assistants) John Chatlos at Los Alamitos and Juan Arriaga and (wife) Janet Hollendorfer in Northern California.

“Your supporting cast of assistant trainers has to be solid, too,” said Hollendorfer, who had a trio of three-year-olds hoping to prove they were Triple Crown worthy at press time: Choo Choo, a son of English Channel owned and bred by Calumet Farm; Lecomte winner Instilled Regard; and San Vicente winner Kanthaka.

“If horses are good enough to go (on the Triple Crown trail), you go,” Ward said. “If you miss it, you concentrate on a late-season campaign. It worked well for Shared Belief and Battle of Midway.” Shared Belief, champion two-year-old male of 2013, won 10 of 12 career starts but missed the 2014 Kentucky Derby due to an abscess in his right front foot. Given the necessary time off, he recovered and won the Pacific Classic later that year, and in 2015, the Santa Anita Handicap.

Battle of Midway outran his odds of 40-1 finishing third in the 2017 Kentucky Derby and won the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile last November.

Ron McAnally, in the homestretch of a Hall of Fame career that has reaped a treasure trove of icons led by two-time Horse of the Year John Henry, is down to a dozen runners at age 85, none poised to join Bayakoa, Paseana, Northern Spur, and Tight Spot on the trainer’s list of champions. As McAnally says, “I have outlived all my owners,” save for his wife, Deborah, and a handful of others.

Still, maiden or lowly claimer, Thoroughbreds deserve the best of care, which any dedicated trainer readily provides, cost be damned. His glorious past well behind him, trouper that he is, McAnally remains a regular at Santa Anita, although leaving all the heavy lifting to longtime assistant Dan Landers.

Landers was born in a racing trunk, to paraphrase an old show business lexicon. His late father, Dale, rode at Santa Anita the first day it opened, on Christmas Day 1934, and won the second race on a horse named Let Her Play. Landers still has a chart of the race.

“Even if I weren’t here for a few weeks, Dan would know what to do because he’s been with us a long time,” McAnally said. “Dan really works hard, and although he’s got three or four grooms, if they don’t perform their duties as they should, he finds someone else.

“That’s the type of guy he is. He wants things done perfectly--the barn is always clean--and that’s what you look for in an assistant, someone who can take your place when you’re not there, and he’s there.

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

August - October 2018, issue 49 (PRINT)

$5.95

August - October 2018, issue 49 (DOWNLOAD)

$3.99

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

Print & Online Subscription

$24.95

Staff recruitment and retention. How can we grow our workforce?

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

This article appeared in - European Trainer - issue 54

Wesley Ward Trainer Profile

Trainer Wesley Ward didn’t invent “thinking outside the box,” but he sure is living it—joyfully and successfully: racing fillies vs. colts in graded stakes, running an America-maiden claiming winner in a stakes race at Ascot, giving a 10-pound apprentice his first mount at prestigious Saratoga, and skipping the Breeders’ Cup at Santa Anita to watch his son in a cross country meet a couple thousand miles away in Florida.

Royal Ascot - history, tradition - and 5 days of unsurpassable racing!

Royal Ascot attracts the best trainers and horses from around the world. Watched over by Her Majesty The Queen, with pomp and ceremony adding to five fabulous days of racing, it's easy to see why Ascot draws the international crowd.

"The history and tradition of the place are what makes it so special; it has been going since the early 18th Century." said Ramsey, who has been involved in ownership since 1969 and numbers the 2005 Dubai World Cup among the long list of big races he has plundered, months before the Royal Ascot meeting last year.

THERE'S MORE TO READ ONLINE....

THIS ARTICLE FIRST APPEARED IN - NORTH AMERICAN TRAINER - ISSUE 31

TO READ THIS ARTICLE IN FULL - CLICK HERE

Author: James Crispe