STUDY SUPPORTS PREVENTATIVE SURGERY TO REDUCE RECURRING ENTRAPMENT COLIC

WORDS - JACKIE BELLAMY-ZIONS INTERVIEWING: DR. NICOLA CRIBBWhen a horse suffers nephrosplenic entrapment, a specific type of displacement colic, the risk of it happening again can be elevated. For high-performance horses, that means more than pain and emergency bills; it can disrupt training schedules and competition plans. A preventative surgery called laparoscopic closure of the nephrosplenic space has been widely used for years, but until now, no one knew how long the benefits lasted. Dr. Nicola Cribb, Department of Clinical Studies, Ontario Veterinary College (OVC), discusses new research from a five-year study at the OVC.

► What is nephrosplenic entrapment colic?

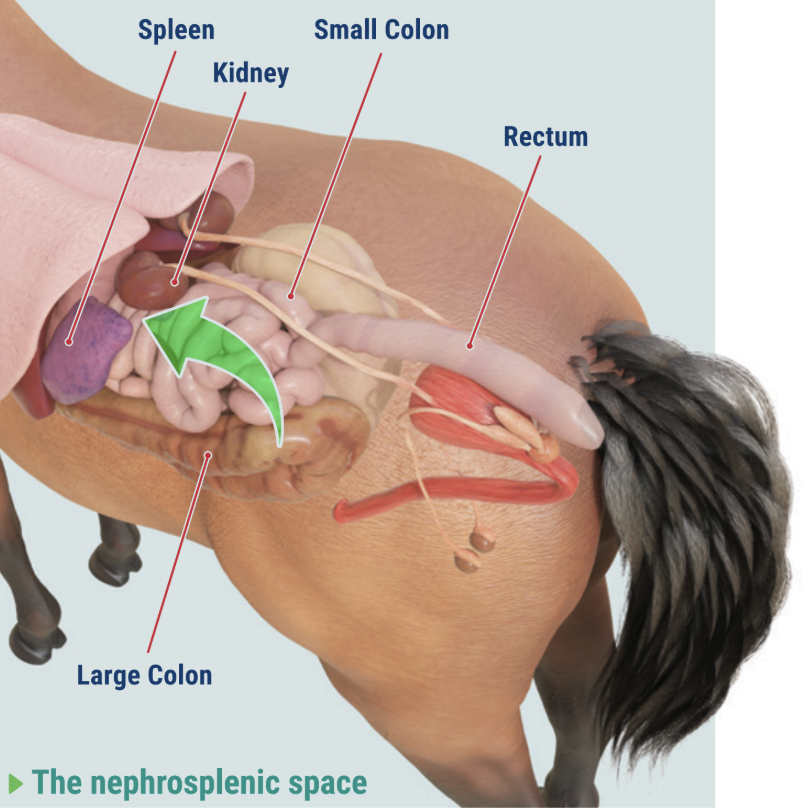

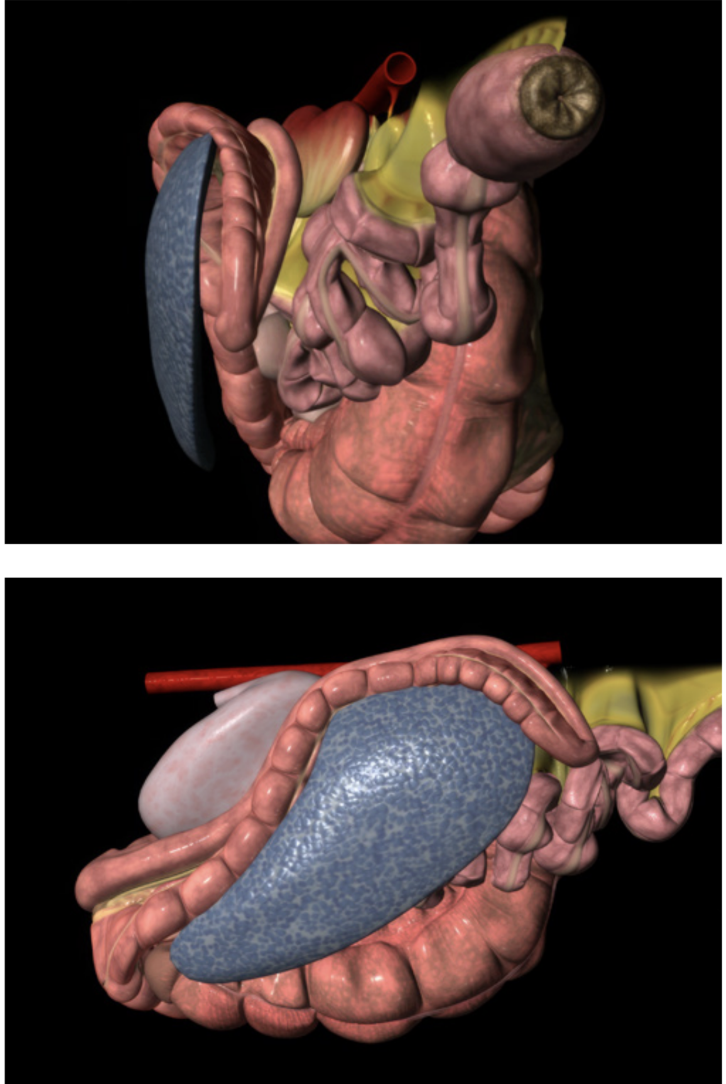

Nephrosplenic entrapment colic is a condition where a section of the large intestine, usually the large colon, moves into the natural gap between the spleen and the left kidney. That gap is called the nephrosplenic space. Some horses can have a deeper or wider space, and if an excess of gas builds up in the large colon, it can cause displacement and the colon may slip into this trough and become trapped.

The result can be painful abdominal distension, gas accumulation, and obstruction of normal gut movement as well as enlargement of the spleen. If untreated, the condition can become life-threatening.

This type of colic is sometimes referred to as left dorsal displacement. While the colon can wander in different directions within the abdomen, this form involves movement to the left and into the nephrosplenic space, where getting unstuck on its own can be difficult, especially if the spleen becomes enlarged.

► Why is it serious?

Nephrosplenic entrapment often requires rapid veterinary intervention. Some horses can be managed medically, but many need surgery to correct the displacement. Horses that have experienced it once can be at higher risk of experiencing it again. That potential for recurrence is why veterinarians began recommending a preventative procedure that closes off the space so the colon cannot fall back into it.

► Why a study of the preventative surgery was needed

Preventative laparoscopic closure of the nephrosplenic space was developed around 25 years ago, it has been widely recommended for horses who have suffered left dorsal displacement colic in order to reduce the chances of recurrence, yet important questions remained.

"We have always been in a position where we've made an assumption that we've closed the space, it's adhered together and the horse is able to go back to exercise and carry on with the rest of its normal life," comments Cribb. "But we've never really had a good method of assessment after we've done the preventative surgery, at which point we could say yes, turn your horse back out to normal exercise and continue as normal."

Both horse owners and veterinarians wanted to know how long the protection can last. Researchers wondered whether a simple, non-invasive test such as ultrasound could confirm that the space had been effectively closed after surgery and if that closure was able to stand the test of time. Recent literature raised these unknowns, which prompted a team at the Ontario Veterinary College to design a long-term study that would follow horses' that had undergone the post-surgical procedure to find out how well the adhesions hold up.

► The nephrosplenic space

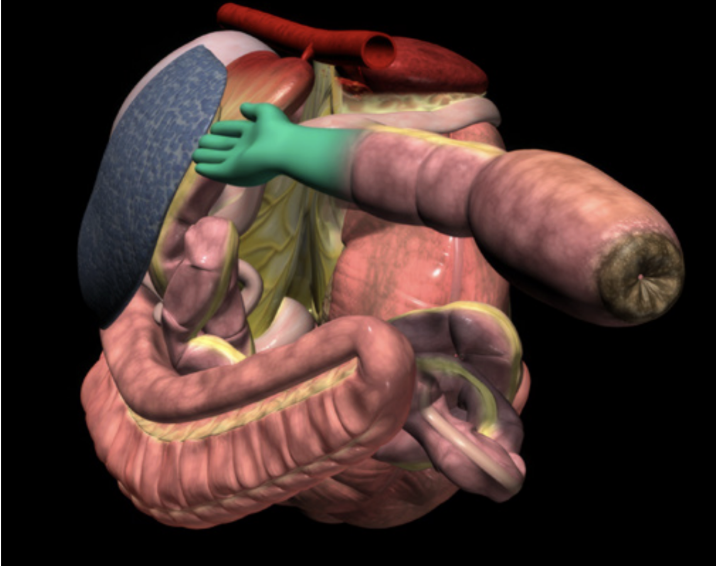

Dr. Cribb and her team set out to evaluate the durability of closure over five years, and to compare common follow-up methods, namely rectal palpation and ultrasound, against repeat laparoscopy, the gold-standard way to look directly at the adhesion.

"We were uniquely positioned to revisit horses' years after their surgery," noted Dr. Cribb. "Putting the laparoscope back in allowed us to verify whether adhesions were present and robust, then compare that against our imaging and palpation findings. That's how we could say, with confidence, what really holds up over time."

► When is elective closure considered?

3D DIAGRAMS COURTESY OF THE GLASS HORSE PROJECT/VETIN3D.NET

Veterinarians consider laparoscopic closure under several conditions: • After a confirmed episode of nephrosplenic entrapment. Horses that have had one episode can be at higher risk for another, which can be costly and dangerous.

• In horses with an anatomical predisposition - a deeper nephrosplenic space or certain conformational traits can make entrapment more likely.

• In high-performance horses. When training and competition schedules can be severely affected by repeat colic events, owners and teams may pursue prevention.

• When the horse is clinically stable and recovered from the initial episode, and the owner understands the risks, costs, and potential benefits.

• When a veterinarian confirms suitability for laparoscopy, including appropriate body condition and an abdomen free from concurrent disease

• When prevention is chosen over repeated emergency interventions, especially if the recurrence risk can outweigh surgical risk.

► What the OVC study set out to do The team's objectives were straightforward and practical:

1. Evaluate the long-term durability of closure, with follow-up at five years after surgery

2. Assess follow-up tools, asking whether ultrasound and rectal palpation can predict closure quality.

3. Develop a reproducible adhesion scoring system, so results can be compared consistently across cases.

To accomplish this, the researchers needed to look at the adhesion itself and decide how strong and extensive it was. Since there was no equine-specific scoring system, the team created one. This is an important contribution because standardized scoring allows future studies to compare outcomes reliably.

The research team built a reproducible adhesion scoring system drawing on established grading frameworks from human surgery, then adapted it for equine anatomy. The score measured three things: how mature the adhesion was (its fibrous development), how strong it felt, and how much of the nephrosplenic space it covered.

► How the study was designed

Twelve horses that had previously undergone laparoscopic closure were included in the OVC study. Each horse had imaging and rectal palpation before surgery, then approximately 30 days after surgery, and again five years later.

At five years, each horse also underwent repeat laparoscopy. This allowed the team to directly inspect the space and judge whether adhesions were present and strong across a meaningful portion of the area between spleen and kidney.

To learn more about what was happening inside the body, the team studied tissue from a few horses and analyzed it for changes over time. They also ran statistical tests to see if anything done during surgery, or measured soon after, could help forecast long- term success.

This approach matters to researchers. Much work has gone into finding the best technique for this surgery, but studies often lack long-term follow-up. This project is notable because it is the first to provide a five-year look, using laparoscopy in order to verify what owners and veterinarians rely on after surgery.

► What the research team found

Strong adhesions can persist for at least five years.

On repeat laparoscopy, most horses had mature, fibrous tissue that kept the space closed. Eight out of ten horses examined had strong adhesions covering most of the nephrosplenic space.

• Rectal palpation can be a useful follow-up tool.

A hands-on examination at four to six weeks after surgery can provide useful information about whether the space feels closed. Ultrasound had limitations.

Although ultrasound is non-invasive and widely available, the researchers found that the bowel often interfered with the view of the nephrosplenic space. Measurements changed over time, but those changes did not consistently match what laparoscopy later showed.

"After the initial entrapment is corrected, some horses are simply at higher risk of doing it again," Cribb explained. "That's why the preventative technique was developed, to remove the 'trough' that invites the colon to fall in. Our long-term look shows most horses keep strong, mature adhesions for years."

Normal anatomy of the nephrosplenic space

"Ultrasound seemed attractive because it's non-invasive and accessible," Crib added. "But in practice, we saw bowel interference and poor correlation with actual adhesion strength. A veterinary rectal exam remains the better indicator at that crucial four to six week mark."

► What this means for horse owners and high-performance programs

The study supports proactive decisions after an episode of nephrosplenic entrapment. While every horse is unique, laparoscopic closure can provide long-lasting protection in many cases. Owners, trainers, and barn managers can use these findings to structure conversations with their veterinary team and plan a careful return to work.

Proactive decisions, practical questions:

• Is my horse a good candidate? Discuss the horse's history, anatomy, and performance goals.

• What is the timeline? Consider when elective closure might be scheduled after recovery from initial surgery, and map out a realistic rehabilitation plan.

• What is the follow up plan? Plan for a rectal exam at four to six weeks. Clarify what signs would prompt additional evaluation.

• Barn management routine. Work with your vet to reduce sudden feed changes, manage stress from shipping and competition, and support hydration and forage intake.

• How to track progress? Keep a simple log of feed adjustments, training intensity, travel dates, and any signs of digestive discomfort, then share those notes at follow-ups.

► Why this research matters for every horse owner

"It helps us justify the use of this surgery after this type of colic and it helps owners make a decision on whether this is the right choice for their horse," explained Cribb.

Recurring colic can affect horse welfare and disrupt programs that depend on consistent training. Preventing repeat entrapment of the colon can help keep horses in condition and maintain confidence in planning seasons and competitions. The study's long-term data gives owners and insurers valuable information when weighing options and assessing risk. It also provides veterinarians with scientific clarity when advising clients on whether preventative surgery for left dorsal displacement can be a suitable choice after an initial episode.

From a research standpoint, this project fills a gap. Much effort has gone into developing and refining techniques to close the nephrosplenic space, yet long-term outcomes can be difficult to capture. This study is notable because it provides five-year follow-up and validates results with repeat laparoscopy, which is considered the most direct way to judge what is happening inside the abdomen. The adapted adhesion scoring system gives future investigators a practical way to compare cases, and it sets the stage to connect scoring with real-world outcomes, such as how long horses remain free of entrapment colic signs.

► What comes next?

"Our five year study showed the adhesions can last and their quality in keeping the space closed," said Dr. Cribb. "We want to go a step further and ask: are these preventing colic signs for this specific type of colic?"

The researchers are interested in larger data sets tracking clinical cases over longer periods to further validate the adhesion scoring system and to see whether stronger scores line up with more time "colic-free".

PRACTICAL CHECKLIST AFTER AN ENTRAPMENT EPISODE

1. Confirm the diagnosis and discuss prevention. After the horse stabilizes, ask whether laparoscopic closure can be appropriate.

2. Plan the follow-up. Schedule a rectal exam at four to six weeks.

3. Map the return to work. Re-introduce exercise gradually. Emphasize forage, hydration, routine and avoid abrupt feed changes as outlined in Equine Guelph's Colic Risk Rater (see below).

4. When returning to travel and competition. Minimize stressors around shipping. Keep electrolytes and water access consistent, and monitor for changes in manure quality and consistency.

5. Keep records. Note any colic-like signs, feed changes, and intense training days. Share your log at veterinary check-ins.

6. Educate your team. Make sure grooms, riders, and barn managers understand early warning signs and the post-op plan.

EQUINE GUELPH helping horses for life

While some cases, like nephrosplenic entrapment, require surgical intervention, the goal of prevention is to avoid costly, life-saving procedures whenever possible. Many colic risks can be reduced through informed management. Education is your best defense.

February is Colic Prevention Month at Equine Guelph, but it's always a good time to take action to reduce colic risk.

COLIC RISK RATER:

Identify risk factors in your barn and areas for improvement with Equine Guelph's FREE online tool designed to help you enhance safety, management, and horse health.

GUT HEALTH & COLIC/ULCER PREVENTION SHORT COURSE: FEB 16-27, 2026

Learn from experts in this concise, evidence- based online program for your entire team.

VISIT THEHORSEPORTAL.CA

EQUINE NEWS & RESOURCES

Can Spirulina help horses recover faster from intense exercise?

Article by Jackie Bellamy-Zions interviewing Wendy Pearson and Dr. Nadia Golestani

Elevating performance and seeking the competitive edge is what makes equine supplements a billion-dollar industry, but what makes the difference between a supplement that simply creates ‘expensive urine’ and a nutritional supplement that could actually have an impact?

Associate professor at the University of Guelph, Wendy Pearson and Ph.D. candidate Dr. Nadia Golestani, answer this question and more in their quest to develop quality nutraceuticals with positive equine health benefits. Their latest study on Spirulina reveals potential for expediting recovery after intense exercise. It also holds promise supporting joint health and optimizing performance through enhancing oxygen delivery in the bloodstream.

Why Spirulina?

After becoming a DVM, Dr. Nadia Golestani began to pursue her goal of becoming an animal nutritionist, enrolling in the University of Guelph’s Master of Animal Biosciences program under the supervision of Dr. Wendy Pearson.

After attending Pearson’s lectures on exercise physiology, Golestani developed a good understanding of the controversy surrounding antioxidants and the lack of research as to whether they were good for exercise performance or not. For her Master’s, Golestani examined inflammatory response of cartilage during exposure to nutraceuticals that could potentially have a role in equine joint care.

Golestani had her eyes opened to the potential of Spirulina after reading a book named ‘Spirulina World Food.’ It was a gift from accomplished medicinal chemistry consultant, Ralph Robinson, which accompanied an award for Golestani’s research in equine nutrition and physiology.

Golestani wanted to explore ways Spirulina could be used in exercise physiology. Her Ph.D research, under Pearson, set out to study the effects of Spirulina as an antioxidant and how it could potentially modulate inflammation after high-intensity exercise in horses. It was made possible thanks to the support of Robinson, owner of Selected Bioproducts (Herbs for Horses) Inc., and funding from Equine Guelph.

What is Spirulina?

The blue-green algae is gaining popularity not just in human athletes but in equine ones as well. The nutritional profile contains C-phycocyanin and Beta carotene and 60 – 70% amino acids. It has vitamin B, iron, vitamin E and essential fatty acids, particularly gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) plus many more vitamins, proteins and minerals.

Golestani’s study focused on C-phycocyanin and Beta carotene in Spirulina with their potential antioxidant effects. New data shows antioxidants can be a double-edged sword with the capability of reducing inflammation as this may actually interfere with natural tissue adaptation after the rigors of exercise. Golestani’s study is looking for the best applications for Spirulina to optimize equine performance without interfering in the natural tissue adaptation process.

Enhancing recovery without interfering with transient inflammation

Some inflammation is normal after exercise and protects structures as they recover from the workout. Only when inflammation becomes excessive, does it become a concern in disrupting recovery.

“Transient inflammation is good and needed for recovery. Inflammation challenges the tissue, and the tissue responds by becoming stronger,” says Pearson. “What isn't good is chronic, sustained inflammation. We want to see if we can do something about the way tissue responds to an exercise bout, without interfering with transient inflammation.”

Golestani explains, when a horse undergoes exercise, their ATP (adenosine triphosphate) producing mitochondria are working hard. One of the natural byproducts is Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS are highly reactive molecules containing oxygen), which is good unless they are produced in excess leading to oxidative stress. When there is an imbalance between the production of ROS and the body's ability to detoxify them with antioxidants, this is when chronic oxidative stress can trigger vicious cycles of inflammation. Oxidative stress can also lead to cell death and therefore dysfunction and disease. Maintaining balance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses is essential for cellular health.

Golestani sums up, “Strenuous exercise, especially when it is high impact, is going to stress the horse’s joints and increase oxidative stress. Imbalance can damage the cells, proteins, lipids in the joint tissue and may lead to early onset of arthritis.”

Pearson adds, “Moderate intensity exercise is very good for protecting cartilage structure, but when you have repeated bouts of strenuous or very high intensity exercise it can tip the scales to more breakdown of cartilage than you have time to resynthesize. Tissue breakdown occurs when synthesis can't keep up, that's when you start to see declining structural integrity of the tissue.”

‘What is adequate recovery time’ becomes the million-dollar question with no definitive answer given a multitude of variables including the starting fitness level, type of activity, intensity of work, and other factors specific to each horse as an individual. This is where talented horse trainers excel. They can pick up on a change of behaviour in the horse in a workout even before physical signs of stress and adjust the training program accordingly.

You bet your biomarkers

Golestani researched the antioxidant effects of Spirulina, by looking at biomarkers associated with inflammation. In her study, biomarkers were measured before and after exercising horses that were given a Spirulina supplement against those who were not.

Results showed that exercise caused a temporary increase in nitric oxide (NO), a marker of oxidative stress, shortly after activity. This rise was discovered in both blood plasma and the synovial fluid. Horses given Spirulina had lower NO levels during recovery, indicating better management of oxidative stress. In joint fluid, NO levels increased 24 hours after exercise but were better controlled in the Spirulina group, with lower levels observed later in recovery. This signifies not only the potential for quick recovery from exercise but also properties that could promote joint health.

Another inflammation marker, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), was also measured. PGE2 levels in the blood peaked eight hours after exercise and were higher in horses that received Spirulina, suggesting a stronger initial response to exercise. In joint fluid, Spirulina-supplemented horses showed lower PGE2 levels early in recovery, which may help reduce inflammation in joints over time and lower chances of early onset of arthritis.

A key finding was that Spirulina boosted levels of Resolvin D1 (RvD1). “RvD1 is so important in resolving the inflammation and promoting the clearance of inflammatory cells and for tissue repair,” said Goestani. RvD1 is a bio active lipid mediator derived from omega-3 fatty acid. Horses receiving Spirulina had consistently higher RvD1 levels in their blood and joint fluid during after exercise.

The rise in the RvD1 biomarker highlights how Spirulina has the potential to enhance this natural resolution pathway and its potential to protect against inflammation, speed up recovery and promote cartilage protection.

Pearson echoed the dramatic increase in Resolvin D1 in the horse’s receiving Spirulina to be pretty strong evidence that it could protect horses from bouts of transient inflammation from becoming chronic and contribute to faster recovery after exercise.

Horses fed Spirulina in the study also had higher hematocrit levels, which means their blood could carry more oxygen, translating into potentially enhanced performance. They also maintained higher glucose levels during recovery, providing more energy. Eight hours after exercise the control group had a drop in glucose, but the group fed Spirulina did not. Retaining glucose stores post-exercise is especially helpful for performance horses that need sustained energy and endurance during training or competition.

Importantly, there were no negative effects on cartilage biomarkers, further suggesting Spirulina may also promote joint health during recovery.

Look at the label and beyond the label

“Buying a quality product requires looking beyond the label,” says Pearson. “There are so many products on the market today that it is virtually impossible for even somebody like me, who spends my life looking at nutraceuticals, to look at a label of one product and tell the difference between that and the product on the shelf right next to it.”

Looking for third party quality assurance can be one indicator on the label that the product has some validity. Examples include:

ISO 22000 The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides standards to ensure the quality, safety, and efficiency of products.

HACCP Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points principles identify, evaluate, and control hazards that are significant for food safety.

CCP Critical Control point is a step in the manufacturing process where control can be applied to prevent, eliminate, or reduce a food safety hazard to acceptable levels including: properly mixing ingredients to ensure uniform distribution and prevent contamination, applying heat or other sterilization methods to eliminate microbial hazards and ensuring the final product is packaged in a way that prevents contamination and preserves quality.

NASC The National Animal Supplement Council (NASC) Quality Seal is a mark of quality assurance for animal health supplements in the USA.

GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices) Certification: This certification ensures that the products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards. It covers all aspects of production, from the raw materials to the hygiene of staff.

UFAS (Universal Feed Assurance Scheme): This scheme is specific to the UK and ensures that animal feed and supplements are produced to high standards of safety and quality.

BETA NOPS (Naturally Occurring Prohibited Substances): This certification is particularly important for competitive horses. It ensures that the supplements are free from substances that are banned in equine sports.

Most importantly, Pearson implores horse owners to find out if the manufacturer has invested in research on the particular product they are marketing. “Lots of companies will talk about the fact that they're science based, but if you peel off a layer or two, you find that in fact the science they're talking about is science other researchers have done on ingredients that show up on the label on their product.”

Pearson emphasizes the importance of manufacturers conducting research of their products in the targeted species that supplement is created for. She takes a moment to lament the vast number of supplements on the market with no significant research behind them. It is much cheaper for companies to use anecdotal reports or sponsor a top rider to promote their products than conduct double blind studies with valid evidence-based results.

“The research is expensive,” says Pearson. “We are lucky to have funding from Equine Guelph for our latest study on Spirulina. If consumers prioritized purchasing products with research behind them, manufacturers that are not yet doing research on their products would have an economic reason to do so.”

So, horse owners have a bit of homework to do if they want a quality product and not just ‘expensive urine’. Asking to see the research on the product you intend to buy is the best bet for purchasing a product that is likely to deliver on its claims.

Nutraceuticals Increasing Popularity Raises Precautions

Pearson recalls when she started researching nutraceuticals for horses in 1997, “The word was not even well-known back then. It simply wasn’t a ‘thing’ at the time.” We have gone from whisperings of feed additives and ‘novel’ ingredients being the work of ‘witch doctors’ to the common place practice of adding supplements to feed.

“There is a night-and-day difference with upwards of 80% of horse owners adding something to their horses’ diet; whether that something is electrolytes or nutraceuticals or herbal supplements,” says Pearson. “These products can be really helpful in improving health, but they are not intended to be an opportunity for horse people to start to self-diagnose and self-treat disease.”

Pearson tells horse owners to always work with their veterinarian. “This is a very important point. Where these products are best positioned is when it's in conversation with the vet; not that all vets are experts in nutraceuticals, but they are all experts in animal health and specifically animal disease.”

Potential problems arise if horse owners end up delaying treatment of a potentially serious problem by reaching for a supplement rather than calling their vet. Pearson cautions, “Using these products can potentially delay proper veterinary care when they're not used properly.”

#1 Consult your veterinarian before adding supplements to your horse’s diet.

#2 Buy from a company that conducts research on their products and doesn't just claim to be ‘science-based’.

Top 3 practical take-aways:

Enhanced Oxygen Delivery and Energy Boost: Spirulina helped improve oxygen delivery and energy reserves in horses.

Support for Joint Health: Spirulina supplementation reduced markers of oxidative stress and enhanced inflammation resolution without damaging joint cartilage. This suggests Spirulina may protect against wear-and-tear on joints, helping reduce the risk of arthritis and supporting long-term joint health in active horses.

Faster Recovery After Exercise: Horses given Spirulina recovered more effectively after intense exercise, as seen by enhancing the production of pro-resolving molecules like Resolvin D1 (RvD1). This makes Spirulina a practical addition to the diet of horses involved in regular training or high-intensity work.

These findings highlight Spirulina’s potential as a safe and natural dietary supplement for managing inflammation, protecting joint health, and supporting recovery in equine athletes. Further research is needed to confirm long-term benefits, but this current study provides evidence that Spirulina offers a promising tool for promoting health and performance in horses.

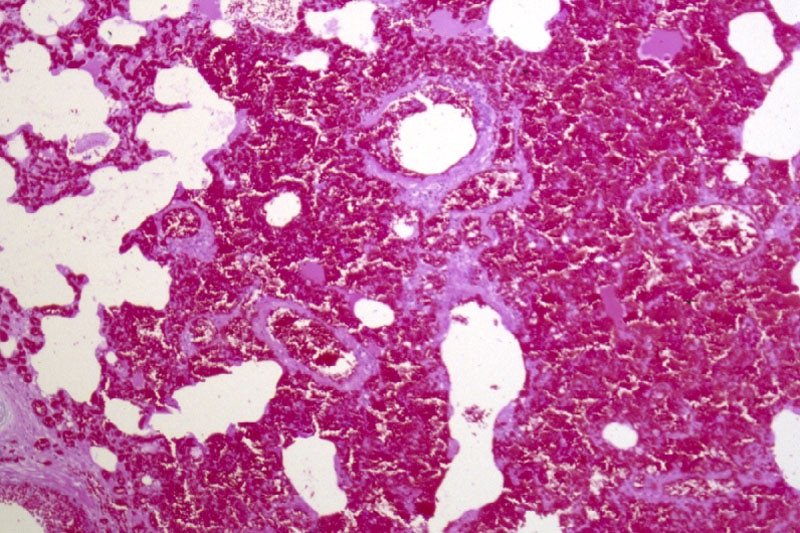

EIPH - could there be links to sudden death and pulmonary haemorrhage?

Dr Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS, explores preliminary research and hypotheses, being conducted by the University of Guelph, to see if there is a possibility that these conditions are linked and what this could mean for future management and training of thoroughbreds.

"World's Your Oyster,” a three-year-old thoroughbred mare, presented at the veterinary hospital for clinical examination. She won her maiden start as a two-year-old and placed once in two subsequent starts. After training well as a three-year-old, she failed to finish her first start, easing at the top of the stretch, and was observed to fade abruptly during training. Some irregularity was suspected in heart rhythm after exercise. Thorough clinical examination, blood work, ultrasound of the heart and an ECG during rest and workout revealed nothing unusual.

Returning to training, Oyster placed in six of her subsequent eight starts, winning the last two. She subsequently died suddenly during early training as a four-year-old. At post-mortem, diagnoses of pulmonary haemorrhage and exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage were established—a very frustrating and unfortunate outcome.

Across the racing world, a case like this probably occurs daily. Anything that can limit a horse's ability to express its genetic potential is a major source of anxiety when training. The possibility of injury and lameness is the greatest concern, but a close second is respiratory disease, with bleeding from the lungs (most often referred to as exercise induced pulmonary [lung] haemorrhage or EIPH) being high on the list.

EIPH is thought to occur in as many as 85 percent of racehorses, and may initially be very mild without obvious clinical consequences. In some cases it can be associated with haemorrhage of sufficient severity for blood to appear at the nostrils, even at first occurrence. In many racing jurisdictions this is a potentially career-ending problem. In these horses, an impact on performance is unquestionable. Bleeding from the lungs is the reason for the existence of ‘Lasix programs,’ involving pre-race administration of a medication considered to reduce haemorrhage. Such programs are controversial—the justifications for their existence ranging from addressing welfare concerns for the horse to dealing with the performance impacts.

Much less frequently encountered is heavy exercise-associated bleeding from the nostrils (referred to as epistaxis), which can sometimes be accompanied by sudden death, during or shortly after exercise. Some horses bleed heavily internally and die without blood appearing at the nostrils. Haemorrhage may only become obvious when the horse is lying on its side, or not until post-mortem. Affected animals do not necessarily have any history of EIPH, either clinically or sub-clinically. There is an additional group of rare cases in which a horse simply dies suddenly, most often very soon after work and even after a winning performance, and in which little to nothing clearly explains the cause on post-mortem. This is despite the fact most racing jurisdictions study sudden death cases very closely.

EIPH is diagnosed most often by bronchoscopy—passing an endoscope into the lung after work and taking a look. In suspected but mild cases, there may not be sufficient haemorrhage to be visible, and a procedure called a bronchoalveolar lavage is performed. The airways are rinsed and fluid is collected and examined microscopically to identify signs of bleeding. Scoping to confirm diagnosis is usually a minimum requirement before a horse can be placed on a Lasix program.

Are EIPH, severe pulmonary haemorrhage and sudden death related? Are they the same or different conditions?

At the University of Guelph, we are working on the hypothesis that most often they are not different—that it’s degrees of the same condition, or closely related conditions perhaps with a common underlying cause. We see varying clinical signs as being essentially a reflection of severity and speed of onset of underlying problems.

Causes in individual cases may reflect multiple factors, so coming at the issues from several different directions, as is the case with the range of ongoing studies, is a good way to go so long as study subjects and cases are comparable and thoroughly documented. However, starting from the hypothesis that these may all represent basically the same clinical condition, we are approaching the problem from a clinical perspective, which is that cardiac dysfunction is the common cause.

Numerous cardiac disorders and cellular mechanisms have the potential to contribute to transient or complete pump (heart) failure. However, identifying them as potential disease candidates does not specifically identify the role they may have played, if any, in a case of heart failure and in lung haemorrhage; it only means that they are potential primary underlying triggers. It isn't possible for us to be right there when a haemorrhage event occurs, so almost invariably we are left looking at the outcome—the event of interest has passed. These concerns influence the approach we are taking.

Background

The superlative performance ability of a horse depends on many physical factors:

Huge ventilatory (ability to move air) and gas exchange capacity

Body structure including limb length and design - allows it to cover ground rapidly with a long stride

Metabolic adaptations - supports a high rate of energy production by burning oxygen, tolerance of severe metabolic disruptions toward the end of race-intensity effort

High cardiovascular capacity - allows the average horse to pump roughly a brimming bathtub of blood every minute

At race intensity effort, these mechanisms, and more, have to work in coordination to support performance. There is likely not much reserve left—two furlongs (400m) from the winning post—even in the best of horses. There are many wild cards, from how the horse is feeling on race day to how the race plays out; and in all horses there will be a ceiling to performance. That ceiling—the factor limiting performance—may differ from horse to horse and even from day to day. There’s no guarantee that in any particular competition circumstances will allow the horse to perform within its own limitations. One of these factors involves the left side of the heart, from which blood is driven around the body to the muscles.

A weak link - filling the left ventricle

The cardiovascular system of the horse exhibits features that help sustain a high cardiac output at peak effort. The feature of concern here is the high exercise pressure in the circulation from the right ventricle, through the lungs to the left ventricle. At intense effort and high heart rates, there is very little time available to fill the left ventricle—sometimes as little as 1/10 of a second; and if the chamber cannot fill properly, it cannot empty properly and cardiac output will fall. The circumstances required to achieve adequate filling include the readiness of the chamber to relax to accept blood—its ‘stiffness.’ Chamber stiffness increases greatly at exercise, and this stiffened chamber must relax rapidly in order to fill. That relaxation seems not to be sufficient on its own in the horse at high heart rates. Increased filling pressure from the circulation draining the lungs is also required. But there is a weak point: the pulmonary capillaries.

These are tiny vessels conducting blood across the lungs from the pulmonary artery to the pulmonary veins. During this transit, all the gas exchange needed to support exercise takes place. The physiology of other species tells us that the trained lung circulation achieves maximum flow (equivalent to cardiac output) by reducing resistance in those small vessels. This process effectively increases lung blood flow reserve by, among other things, dilating small vessels. Effectively, resistance to the flow of blood through the lungs is minimised. We know this occurs in horses as it does in other species; yet in the horse, blood pressure in the lungs still increases dramatically at exercise.

If this increase is not the result of resistance in the small vessels, it must reflect something else, and that appears to be resistance to flow into the left chamber. This means the entire lung circulation is exposed to the same pressures, including the thin-walled capillaries. Capillaries normally work at quite low pressure, but in the exercising horse, they must tolerate very high pressures. They have thin walls and little between them, and the air exchange sacs in the lung. This makes them vulnerable. It's not surprising they sometimes rupture, resulting in lung haemorrhage.

Recent studies identified changes in the structure of small veins through which the blood flows from the capillaries and on toward the left chamber. This was suspected to be a pathology and part of the long-term consequences of EIPH, or perhaps even part of the cause as the changes were first identified in EIPH cases. It could be, however, that remodelling is a normal response to the very high blood flow through the lungs—a way of increasing lung flow reserve, which is an important determinant of maximum rate of aerobic working.

The more lung flow reserve, the more cardiac output and the more aerobic work an animal can perform. The same vein changes have been observed in non-racing horses and horses without any history or signs of bleeding. They may even be an indication that everything is proceeding as required and a predictable consequence of intense aerobic training. On the other hand, they may be an indication in some horses that the rate of exercise blood flow through their lungs is a little more than they can tolerate, necessitating some restructuring. We have lots to learn on this point.

If the capacity to accommodate blood flow through the lungs is critical, and limiting, then anything that further compromises this process is likely to be of major importance. It starts to sound very much as though the horse has a design problem, but we shouldn't rush to judgement. Horses were probably not designed for the very intense and sustained effort we ask of them in a race. Real-world situations that would have driven their evolution would have required a sprint performance (to avoid ambush predators such as lions) or a prolonged slower-paced performance to evade predators such as wolves, with only the unlucky victim being pushed to the limit and not the entire herd.

Lung blood flow and pulmonary oedema

There is another important element to this story. High pressures in the capillaries in the lung will be associated with significant movement of fluid from the capillaries into lung tissue spaces. This movement in fact happens continuously at all levels of effort and throughout the body—it's a normal process. It's the reason the skin on your ankles ‘sticks’ to the underlying structures when you are standing for a long time. So long as you keep moving a little, the lymphatic system will draw away the fluid.

In a diseased lung, tissue fluid accumulation is referred to as pulmonary oedema, and its presence or absence has often been used to help characterise lung pathologies. The lung lymphatic system can be overwhelmed when tissue fluid is produced very rapidly. When a horse experiences sudden heart failure, such as when the supporting structures of a critical valve fail, one result is massive overproduction of lung tissue fluid and appearance of copious amounts of bloody fluid from the nostrils.

The increase in capillary pressure under these conditions is as great as at exercise, but the horse is at rest. So why is there no bloody fluid in the average, normal horse after a race? It’s because this system operates very efficiently at the high respiratory rates found during work: tissue fluid is pumped back into the circulation, and fluid does not accumulate. The fluid is pumped out as quickly as it is formed. An animal’s level of physical activity at the time problems develop can therefore make a profound difference to the clinical signs seen and to the pathology.

Usual events with unusual consequences

If filling the left ventricle and the ability of the lungs to accommodate high flow at exercise are limiting factors, surely this affects all horses. So why do we see such a wide range of clinical pictures, from normal to subclinical haemorrhage to sudden death?

Variation in contributing factors such as type of horse, type and intensity of work, sudden and unanticipated changes in work intensity, level of training in relation to work and the presence of disease states are all variables that could influence when and how clinical signs are seen, but there are other considerations.

Although we talk about heart rate as a fairly stable event, there is in fact quite a lot of variation from beat to beat. This is often referred to as heart rate variability. There has been a lot of work performed on the magnitude of this variability at rest and in response to various short-term disturbances and at light exercise in the horse, but not a lot at maximal exercise. Sustained heart rate can be very high in a strenuously working horse, with beats seeming to follow each other in a very consistent manner, but there is in fact still variation.

Some of this variation is normal and reflects the influence of factors such as respiration. However, other variations in rate can reflect changes in heart rhythm. Still other variations may not seem to change rhythm at all but may instead reflect the way electrical signals are being conducted through the heart.

These may be evident from the ECG but would not appear abnormal on a heart rate monitor or when listening. These variations, whether physiologic (normal) or a reflection of abnormal function, will have a presently, poorly understood influence on blood flow through the lungs and heart—and on cardiac filling. Influences may be minimal at low rates, but what happens at a heart rate over 200 and in an animal working at the limits of its capacity?

Normal electrical activation of the heart follows a pattern that results in an orderly sequence of heart muscle contraction, and that provides optimal emptying of the ventricles. Chamber relaxation complements this process.

An abnormal beat or abnormal interval can compromise filling and/or emptying of the left ventricle, leaving more blood to be discharged in the next cycle and back up through the lungs, raising pulmonary venous pressure. A sequence of abnormal beats can lead to a progressive backup of blood, and there may not be the capacity to hold it—even for one quarter of a second, a whole cardiac cycle at 240 beats per minute.

For a horse that has a history of bleeding and happens to be already functioning at a very marginal level, even minor disturbances in heart rhythm might therefore have an impact. Horses with airway disease or upper airway obstructions, such as roarers, might find themselves in a similar position. An animal that has not bled previously might bleed a little, one that has a history of bleeding may start again, or a chronic bleeder may worsen.

Relatively minor disturbances in cardiac function, therefore, might contribute to or even cause EIPH. If a horse is in relatively tough company or runs a hard race, this may also contribute to the onset or worsening of problems. Simply put, it's never a level playing field if you are running on the edge.

Severe bleeding

It has been suspected for many years that cases of horses dying suddenly at exercise represent sudden-onset cardiac dysfunction—most likely a rhythm disturbance. If the rhythm is disturbed, the closely linked and carefully orchestrated sequence of events that leads to filling of the left ventricle is also disturbed. A disturbance in cardiac electrical conduction would have a similar effect, such as one causing the two sides of the heart to fall out of step, even though the rhythm of the heart may seem normal.

The cases of horses that bleed profusely at exercise and even those that die suddenly without any post-mortem findings can be seen to follow naturally from this chain of events. If the changes in heart rhythm or conduction are sufficient, in some cases to cause massive pulmonary haemorrhage, they may be sufficient in other cases to cause collapse and death even before the horse has time to exhibit epistaxis or even clear evidence of bleeding into the lungs.

EIPH and dying suddenly

If these events are (sometimes) related, why is it that some horses that die of pulmonary haemorrhage with epistaxis do not show evidence of chronic EIPH? This is one of those $40,000 questions. It could be that young horses have had limited opportunity to develop chronic EIPH; it may be that we are wrong and the conditions are entirely unrelated. But it seems more likely that in these cases, the rhythm or conduction disturbance was sufficiently severe and/or rapid in onset to cause a precipitous fall in blood pressure with the animal passing out and dying rapidly.

In this interpretation of events, the missing link is the heart. There is no finite cutoff at which a case ceases to be EIPH and becomes pulmonary haemorrhage. Similarly, there is no distinct point at which any case ceases to be severe EIPH and becomes EAFPH (exercise-associated fatal pulmonary haemorrhage). In truth, there may simply be gradation obscured somewhat by variable definitions and examination protocols and interpretations.

The timing of death

It seems from the above that death should most likely take place during work, and it often does, but not always. It may occur at rest, after exercise. Death ought to occur more often in racing, but it doesn't.

The intensity of effort is only one factor in this hypothesis of acute cardiac or pump failure. We also have to consider factors such as when rhythm disturbances are most likely to occur (during recovery is a favourite time) and death during training is more often a problem than during a race.

A somewhat hidden ingredient in this equation is possibly the animal's level of emotional arousal, which is known to be a risk factor in humans for similar disturbances. There is evidence that emotions/psychological factors might be much more important in horses than previously considered. Going out for a workout might be more stimulating for a racehorse than a race because before a race, there is much more buildup and the horse has more time to adequately warm up psychologically. And then, of course, temperament also needs to be considered. These are yet further reasons that we have a great deal to learn.

Our strategy at the University of Guelph

These problems are something we cannot afford to tolerate, for numerous reasons—from perspectives of welfare and public perception to rider safety and economics. Our aim is to increase our understanding of cardiac contributions by identifying sensitive markers that will enable us to say with confidence whether cardiac dysfunction—basically transient or complete heart failure—has played a role in acute events.

We are also looking for evidence of compromised cardiac function in all horses, from those that appear normal and perform well, through those that experience haemorrhage, to those that die suddenly without apparent cause. Our hope is that we can not only identify horses at risk, but also focus further work on the role of the heart as well as the significance of specific mechanisms. And we hope to better understand possible cardiac contributions to EIPH in the process. This will involve digging deeply into some aspects of cellular function in the heart muscle, the myocardium of the horse, as well as studying ECG features that may provide insight and direction.

Fundraising is underway to generate seed money for matching fund proposals, and grant applications are in preparation for specific, targeted investigations. Our studies complement those being carried out in numerous, different centres around the world and hopefully will fill in further pieces of the puzzle. This is, indeed, a huge jigsaw, but we are proceeding on the basis that you can eat an elephant if you're prepared to process one bite at a time.

How can you help? Funding is an eternal issue. For all the money that is invested in horses there is a surprisingly limited contribution made to research and development—something that is a mainstay of virtually every other industry; and this is an industry.

Look carefully at the opportunities for you to make a contribution to research in your area. Consider supporting studies by making your experience, expertise and horses available for data collection and minimally invasive procedures such as blood sampling.

Connect with the researchers in your area and find out how you can help. Watch your horses closely and contemplate what they might be telling you—it's easy to start believing in ourselves and to stop asking questions. Keep meticulous records of events involving horses in your care— you never know when you may come across something highly significant. And work with researchers (which often includes track practitioners) to make your data available for study.

Remember that veterinarians and university faculty are bound by rules of confidentiality, which means what you tell them should never be ascribed to you or your horses and will only be used without any attribution, anonymously. And when researchers reach out to you to tell you what they have found and to get your reactions, consider actually attending the sessions and participating in the discussion; we can all benefit—especially the ultimate beneficiary which should be the horse. We all have lots to learn from each other, and finding answers to our many challenges is going to have to be a joint venture.

Finally, this article has been written for anybody involved in racing to understand, but covering material such as this for a broad audience is challenging. So, if there are still pieces that you find obscure, reach out for help in interpretation. The answers may be closer than you think!

Oyster

And what about Oyster? Her career was short. Perhaps, had we known precisely what was going on, we might have been able to treat her, or at least withdraw her from racing and avoid a death during work with all the associated dangers—especially to the rider and the associated welfare concerns.

Had we had the tools, we might have been able to confirm that whatever the underlying cause, she had cardiac problems and was perhaps predisposed to an early death during work. With all the other studies going on, and knowing the issue was cardiac, we might have been able to target her assessment to identify specific issues known to predispose.

In the future, greater insight and understanding might allow us to breed away from these issues and to better understand how we might accommodate individual variation among horses in our approaches to selection, preparation and competition. There might be a lot of Oysters out there!

For further information about the work being undertaken by the University of Guelph

Contact - Peter W. Physick-Sheard, BVSc, FRCVS.

Professor Emeritus, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph - pphysick@uoguelph.ca

Research collaborators - Dr Glen Pyle, Professor, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph - gpyle@uoguelph.ca

Dr Amanda Avison, PhD Candidate, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Guelph. ajowett@uoguelph.ca

References

Caswell, J.I. and Williams K.J. (2015), Respiratory System, In ed. Maxie, M. Grant, 3 vols., 6th edn., Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 2; London: Elsevier Health Sciences, 490-91.

Hinchcliff, KW, et al. (2015), Exercise induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses: American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement, J Vet Intern Med, 29 (3), 743-58.

Rocchigiani, G, et al. (2022), Pulmonary bleeding in racehorses: A gross, histologic, and ultrastructural comparison of exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage and exercise-associated fatal pulmonary hemorrhage, Vet Pathol, 16:3009858221117859. doi: 10.1177/03009858221117859. Online ahead of print.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.

Vitalie, Faoro (2019), Pulmonary Vascular Reserve and Aerobic Exercise Capacity, in Interventional Pulmonology and Pulmonary Hypertension, Kevin, Forton (ed.), (Rijeka: IntechOpen), Ch. 5, 59-69.

Manohar, M. and T. E. Goetz (1999), Pulmonary vascular resistance of horses decreases with moderate exercise and remains unchanged as workload is increased to maximal exercise, Equine Vet. J., (Suppl.30), 117-21.