STUDY SUPPORTS PREVENTATIVE SURGERY TO REDUCE RECURRING ENTRAPMENT COLIC

WORDS - JACKIE BELLAMY-ZIONS INTERVIEWING: DR. NICOLA CRIBBWhen a horse suffers nephrosplenic entrapment, a specific type of displacement colic, the risk of it happening again can be elevated. For high-performance horses, that means more than pain and emergency bills; it can disrupt training schedules and competition plans. A preventative surgery called laparoscopic closure of the nephrosplenic space has been widely used for years, but until now, no one knew how long the benefits lasted. Dr. Nicola Cribb, Department of Clinical Studies, Ontario Veterinary College (OVC), discusses new research from a five-year study at the OVC.

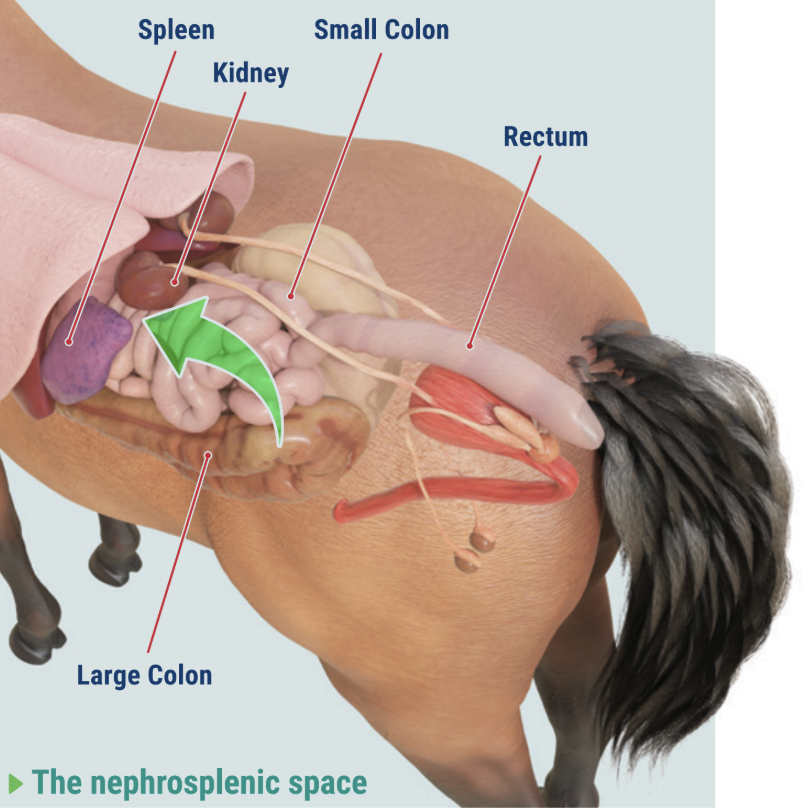

► What is nephrosplenic entrapment colic?

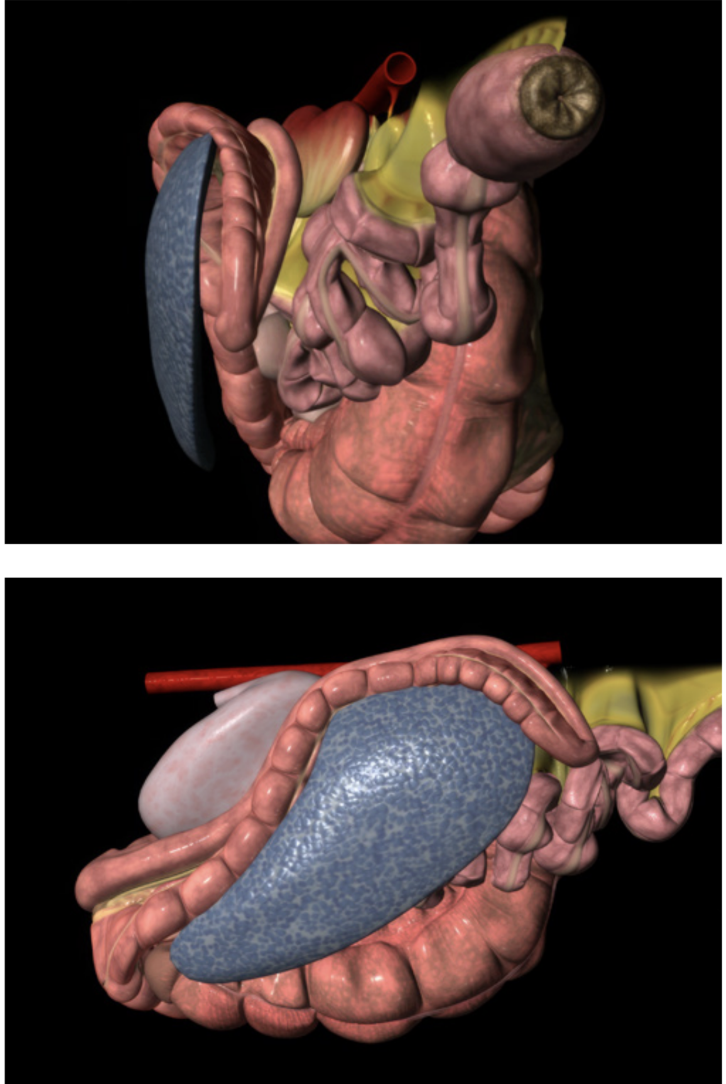

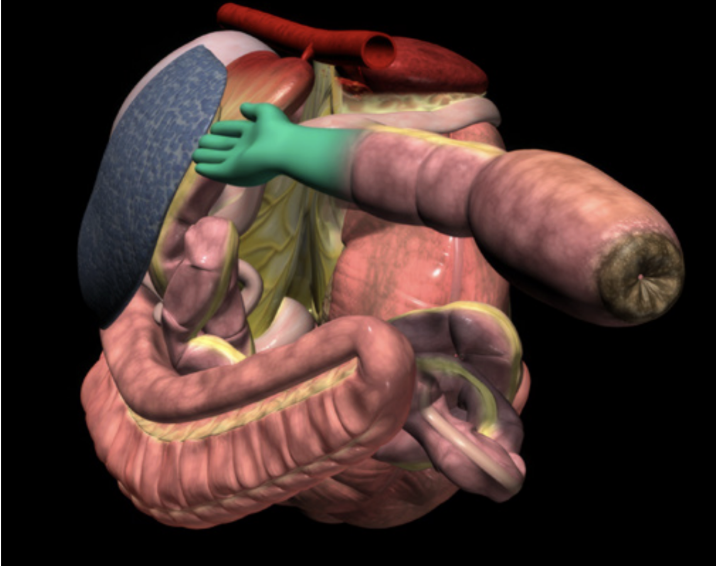

Nephrosplenic entrapment colic is a condition where a section of the large intestine, usually the large colon, moves into the natural gap between the spleen and the left kidney. That gap is called the nephrosplenic space. Some horses can have a deeper or wider space, and if an excess of gas builds up in the large colon, it can cause displacement and the colon may slip into this trough and become trapped.

The result can be painful abdominal distension, gas accumulation, and obstruction of normal gut movement as well as enlargement of the spleen. If untreated, the condition can become life-threatening.

This type of colic is sometimes referred to as left dorsal displacement. While the colon can wander in different directions within the abdomen, this form involves movement to the left and into the nephrosplenic space, where getting unstuck on its own can be difficult, especially if the spleen becomes enlarged.

► Why is it serious?

Nephrosplenic entrapment often requires rapid veterinary intervention. Some horses can be managed medically, but many need surgery to correct the displacement. Horses that have experienced it once can be at higher risk of experiencing it again. That potential for recurrence is why veterinarians began recommending a preventative procedure that closes off the space so the colon cannot fall back into it.

► Why a study of the preventative surgery was needed

Preventative laparoscopic closure of the nephrosplenic space was developed around 25 years ago, it has been widely recommended for horses who have suffered left dorsal displacement colic in order to reduce the chances of recurrence, yet important questions remained.

"We have always been in a position where we've made an assumption that we've closed the space, it's adhered together and the horse is able to go back to exercise and carry on with the rest of its normal life," comments Cribb. "But we've never really had a good method of assessment after we've done the preventative surgery, at which point we could say yes, turn your horse back out to normal exercise and continue as normal."

Both horse owners and veterinarians wanted to know how long the protection can last. Researchers wondered whether a simple, non-invasive test such as ultrasound could confirm that the space had been effectively closed after surgery and if that closure was able to stand the test of time. Recent literature raised these unknowns, which prompted a team at the Ontario Veterinary College to design a long-term study that would follow horses' that had undergone the post-surgical procedure to find out how well the adhesions hold up.

► The nephrosplenic space

Dr. Cribb and her team set out to evaluate the durability of closure over five years, and to compare common follow-up methods, namely rectal palpation and ultrasound, against repeat laparoscopy, the gold-standard way to look directly at the adhesion.

"We were uniquely positioned to revisit horses' years after their surgery," noted Dr. Cribb. "Putting the laparoscope back in allowed us to verify whether adhesions were present and robust, then compare that against our imaging and palpation findings. That's how we could say, with confidence, what really holds up over time."

► When is elective closure considered?

3D DIAGRAMS COURTESY OF THE GLASS HORSE PROJECT/VETIN3D.NET

Veterinarians consider laparoscopic closure under several conditions: • After a confirmed episode of nephrosplenic entrapment. Horses that have had one episode can be at higher risk for another, which can be costly and dangerous.

• In horses with an anatomical predisposition - a deeper nephrosplenic space or certain conformational traits can make entrapment more likely.

• In high-performance horses. When training and competition schedules can be severely affected by repeat colic events, owners and teams may pursue prevention.

• When the horse is clinically stable and recovered from the initial episode, and the owner understands the risks, costs, and potential benefits.

• When a veterinarian confirms suitability for laparoscopy, including appropriate body condition and an abdomen free from concurrent disease

• When prevention is chosen over repeated emergency interventions, especially if the recurrence risk can outweigh surgical risk.

► What the OVC study set out to do The team's objectives were straightforward and practical:

1. Evaluate the long-term durability of closure, with follow-up at five years after surgery

2. Assess follow-up tools, asking whether ultrasound and rectal palpation can predict closure quality.

3. Develop a reproducible adhesion scoring system, so results can be compared consistently across cases.

To accomplish this, the researchers needed to look at the adhesion itself and decide how strong and extensive it was. Since there was no equine-specific scoring system, the team created one. This is an important contribution because standardized scoring allows future studies to compare outcomes reliably.

The research team built a reproducible adhesion scoring system drawing on established grading frameworks from human surgery, then adapted it for equine anatomy. The score measured three things: how mature the adhesion was (its fibrous development), how strong it felt, and how much of the nephrosplenic space it covered.

► How the study was designed

Twelve horses that had previously undergone laparoscopic closure were included in the OVC study. Each horse had imaging and rectal palpation before surgery, then approximately 30 days after surgery, and again five years later.

At five years, each horse also underwent repeat laparoscopy. This allowed the team to directly inspect the space and judge whether adhesions were present and strong across a meaningful portion of the area between spleen and kidney.

To learn more about what was happening inside the body, the team studied tissue from a few horses and analyzed it for changes over time. They also ran statistical tests to see if anything done during surgery, or measured soon after, could help forecast long- term success.

This approach matters to researchers. Much work has gone into finding the best technique for this surgery, but studies often lack long-term follow-up. This project is notable because it is the first to provide a five-year look, using laparoscopy in order to verify what owners and veterinarians rely on after surgery.

► What the research team found

Strong adhesions can persist for at least five years.

On repeat laparoscopy, most horses had mature, fibrous tissue that kept the space closed. Eight out of ten horses examined had strong adhesions covering most of the nephrosplenic space.

• Rectal palpation can be a useful follow-up tool.

A hands-on examination at four to six weeks after surgery can provide useful information about whether the space feels closed. Ultrasound had limitations.

Although ultrasound is non-invasive and widely available, the researchers found that the bowel often interfered with the view of the nephrosplenic space. Measurements changed over time, but those changes did not consistently match what laparoscopy later showed.

"After the initial entrapment is corrected, some horses are simply at higher risk of doing it again," Cribb explained. "That's why the preventative technique was developed, to remove the 'trough' that invites the colon to fall in. Our long-term look shows most horses keep strong, mature adhesions for years."

Normal anatomy of the nephrosplenic space

"Ultrasound seemed attractive because it's non-invasive and accessible," Crib added. "But in practice, we saw bowel interference and poor correlation with actual adhesion strength. A veterinary rectal exam remains the better indicator at that crucial four to six week mark."

► What this means for horse owners and high-performance programs

The study supports proactive decisions after an episode of nephrosplenic entrapment. While every horse is unique, laparoscopic closure can provide long-lasting protection in many cases. Owners, trainers, and barn managers can use these findings to structure conversations with their veterinary team and plan a careful return to work.

Proactive decisions, practical questions:

• Is my horse a good candidate? Discuss the horse's history, anatomy, and performance goals.

• What is the timeline? Consider when elective closure might be scheduled after recovery from initial surgery, and map out a realistic rehabilitation plan.

• What is the follow up plan? Plan for a rectal exam at four to six weeks. Clarify what signs would prompt additional evaluation.

• Barn management routine. Work with your vet to reduce sudden feed changes, manage stress from shipping and competition, and support hydration and forage intake.

• How to track progress? Keep a simple log of feed adjustments, training intensity, travel dates, and any signs of digestive discomfort, then share those notes at follow-ups.

► Why this research matters for every horse owner

"It helps us justify the use of this surgery after this type of colic and it helps owners make a decision on whether this is the right choice for their horse," explained Cribb.

Recurring colic can affect horse welfare and disrupt programs that depend on consistent training. Preventing repeat entrapment of the colon can help keep horses in condition and maintain confidence in planning seasons and competitions. The study's long-term data gives owners and insurers valuable information when weighing options and assessing risk. It also provides veterinarians with scientific clarity when advising clients on whether preventative surgery for left dorsal displacement can be a suitable choice after an initial episode.

From a research standpoint, this project fills a gap. Much effort has gone into developing and refining techniques to close the nephrosplenic space, yet long-term outcomes can be difficult to capture. This study is notable because it provides five-year follow-up and validates results with repeat laparoscopy, which is considered the most direct way to judge what is happening inside the abdomen. The adapted adhesion scoring system gives future investigators a practical way to compare cases, and it sets the stage to connect scoring with real-world outcomes, such as how long horses remain free of entrapment colic signs.

► What comes next?

"Our five year study showed the adhesions can last and their quality in keeping the space closed," said Dr. Cribb. "We want to go a step further and ask: are these preventing colic signs for this specific type of colic?"

The researchers are interested in larger data sets tracking clinical cases over longer periods to further validate the adhesion scoring system and to see whether stronger scores line up with more time "colic-free".

PRACTICAL CHECKLIST AFTER AN ENTRAPMENT EPISODE

1. Confirm the diagnosis and discuss prevention. After the horse stabilizes, ask whether laparoscopic closure can be appropriate.

2. Plan the follow-up. Schedule a rectal exam at four to six weeks.

3. Map the return to work. Re-introduce exercise gradually. Emphasize forage, hydration, routine and avoid abrupt feed changes as outlined in Equine Guelph's Colic Risk Rater (see below).

4. When returning to travel and competition. Minimize stressors around shipping. Keep electrolytes and water access consistent, and monitor for changes in manure quality and consistency.

5. Keep records. Note any colic-like signs, feed changes, and intense training days. Share your log at veterinary check-ins.

6. Educate your team. Make sure grooms, riders, and barn managers understand early warning signs and the post-op plan.

EQUINE GUELPH helping horses for life

While some cases, like nephrosplenic entrapment, require surgical intervention, the goal of prevention is to avoid costly, life-saving procedures whenever possible. Many colic risks can be reduced through informed management. Education is your best defense.

February is Colic Prevention Month at Equine Guelph, but it's always a good time to take action to reduce colic risk.

COLIC RISK RATER:

Identify risk factors in your barn and areas for improvement with Equine Guelph's FREE online tool designed to help you enhance safety, management, and horse health.

GUT HEALTH & COLIC/ULCER PREVENTION SHORT COURSE: FEB 16-27, 2026

Learn from experts in this concise, evidence- based online program for your entire team.

VISIT THEHORSEPORTAL.CA

EQUINE NEWS & RESOURCES

Gut issue biomarkers and their use in signalling dysbiosis

Article by Jackie Zions

Gastrointestinal issues (GI) are the number one cause of morbidity in horses other than old age. An unhealthy digestive system can cause poor performance, pain, discomfort, diarrhea, and a whole host of issues that can sideline your horse. It’s no wonder researchers are paying close attention to the ‘second brain’ and it’s billions of inhabitants. Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) researcher, Dr. Luis Arroyo has been studying the equine gastrointestinal systems for many years with several research projects receiving funding from Equine Guelph. Arroyo discusses what we know about equine gut health, causes of GI disorders and the extensive continuing research to understand what unstable and stable gut populations look like.

Starting with some basic anatomy Arroyo says, “The gastrointestinal tract of a horse is extremely large, and there are many things that can cause disturbances to the normal functioning or health of the gut.” A healthy gut microbiome is essential for the horse’s entire body to function optimally.

Signs of GI issues

Common signs of disorders could include abdominal pain, bloating, changes in fecal consistency (including diarrhea or constipation), excessive drooling, decrease in water consumption, lack of or poor appetite, weight loss and low body condition score.

“Some cases are more obvious to owners,” says Arroyo, “like poor performance, or acute or chronic diarrhea.”

Changes of behaviour such as becoming cranky or moody can be tell-tale signs there is unrest in the GI system. Biting at the flanks can signal abdominal pain as well as reactivity to being saddled. When the horse stops wanting to perform and athletic abilities suddenly decline, if there is no obvious lameness, GI issues are high among the considerations.

“Horses are herbivores, designed to consume a diet of forage, and to break down complex sugars within that forage.” says Arroyo. “The gut microbiota does this job and is very important for healthy digestion.” Recent research is connecting the changes in diversity of microbial communities to conditions like colic, colitis, and gastric ulcers.

Causes of GI Issues

Colic is the number one clinical condition occurring in horses. It is well-known that sudden dietary changes can be a major contributor as well as diets that are high in grain. This can create changes in the volatile fatty acids produced in the GI system, which in turn can lead to the development of gas colic. Arroyo provides the example of switching from dry hay fed in the winter, too rich, lush, spring grass as a big cause of rapid fermentation that can cause colic.

Any abrupt change, even if it’s a good quality feed to a different good quality feed, can be a source of colic. Then there is the more obvious consumption of moldy, poor, quality hay. So not only the quality but the transition/adaptation period needs to be considered when making feed changes and this goes for both changes to forage or concentrates.

A table of feed transition periods on the Equine Guelph website states an adaptation period of at least 10 – 14 days is recommended. Transition periods under seven days can increase colic risk over 22 times!

“Decrease in water consumption can be an issue, especially in countries with seasons,” says Arroyo. When water gets really cold, horses often drink less, and if it freezes, they don’t drink at all, which can lead to impaction colic. Parasite burden can also cause colic. If your horse lives in a sandy environment, like California, ingesting sand can cause impaction colic.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) can cause colic or ulcers. NSAIDS can interfere with blood supply to the GI tract causing ulceration, for example in the mucosa of the stomach. Prolonged use can cause quite severe ulceration.

NSAIDS are not the only drugs that can contribute to GI issues. “Antibiotics - as the name says - kill many kinds of bacteria,” says Arroyo. “They are designed for that! Invariably they deplete some bacterial populations including in the intestine, and that is a problem because that may allow some other bacteria, potentially pathogenic or harmful, to overgrow, and that can cause dysbiosis.”

In a recent study, by fellow OVC researcher, Dr. Gomez and co-workers, it was determined that damage to the intestinal microbiota could occur after only 5 days of administering antibiotics to horses. Damage to the intestinal microbiota resembled dysbiosis that can potentially result in intestinal inflammation and colitis predisposing the horse to diarrhea. Judicious use of antibiotics and antimicrobials are advised.

There are infectious and non-infectious causes of colitis. Infectious examples include salmonella and then there is Neorickettsia risticii, which if ingested from contaminated sources, can cause Salmonellosis or Potomac horse fever, respectively.

“Any stress factors such as transportation, fasting or intense exercise like racing, can be a factor for developing stomach ulcers,” says Arroyo.

Current Diagnostics

Putting together a picture of the horse’s health status includes gathering clinical history from the horse owner and performing a physical examination for motility and hydration status. A biochemistry profile and complete set count can be gathered from blood testing.

Gastric ultrasound allows veterinarians to view the wall of the intestine, noting if it has thickened or distended, which could occur in cases when there is colic. They can assess appearance and find out if the intestine is displaced or if there is a twist. Gastroscopy is commonly used to find ulcers in the stomach and can reach as far as the first part of the duodenum.

GI Research

“DNA sequencing has been a breakthrough in science in terms of understanding the communities of different microorganisms living in many different niches from the skin to the lungs to the upper airways to the intestine,” says Arroyo.

It has allowed in-depth study of the population of microorganisms, providing a big picture of the different inhabitants in various areas of the GI tract, such as the lumen of the small intestine and the small and large colon. “The microorganisms vary, and they have different functions in each compartment,” says Arroyo.

DNA sequencing has allowed researchers to study microbial populations and gather information on what happens to bacterial communities when impacted by diseases like colitis. “We can see who is down, and who is up,” explains Arroyo, “and determine what populations have been depleted.” It has led to a better knowledge of which of the billions of factors are harmful to the system and which can compromise the health of the horse.

Robo-gut is one example of a fantastic system where bacterial communities are being replicated in the lab to mimic what would be found in a natural environment.

Researchers at the University of Guelph have measured metabolic profiles of the bacterial population after the addition of supplements like probiotics and prebiotics. They found they can dramatically change the metabolites that are being produced, according to what is being added to the system.

Exciting new research that could impact the future of diagnostics includes screening for biomarkers as indicators of intestinal health among equine microbiota. Dr. Arroyo is currently working with research partner, Dr. Marcio Costa, from the University of Montreal, looking for biomarkers that indicate changes in the inhabitants of the equine gut that take place during the early onset of illness.

“A biomarker is a biological molecule that you can find in different places,” explains Arroyo. “For example, you might find them in tissue, blood, urine, or different body fluids. They can signal normal or abnormal processes or could reveal a marker of a disease. For example, a biomarker can be used to see how well the body might respond to a treatment or to a disease condition.”

“The objective of a dysbiosis index is quantifying ‘X’ number of certain bacteria that are important to us,” says Arroyo. In this case, the dysbiosis derives from sequencing of the bacterial population in fecal samples.

Changes in the intestinal microbiota (dysbiosis) are present before and during the outset of diseases and after treatment with antibiotics. Arroyo cites the example of decreased Lachnospiraceae commonly observed when there is intestinal inflammation.

Bacterial biomarkers are currently being used in other species to accurately predict intestinal dysbiosis, for example in cats and dogs. One canine study quantified the number of seven different taxa of importance of the total bacterial populations. This information is entered into a mathematical algorithm that comes up with results explaining which bacteria have increased or decreased. Based on those numbers, one can use a more specific taxa to identify dysbiosis. In a feline study, it was discovered that six bacterial taxa could be accurately used to predict diarrhea in 83% of cases.

It is hoped the same results could be accomplished for horses. Developing PCR testing to screen for biomarkers could be a game changer that could potentially provide speedy, economical early diagnostics and early treatment.

So far, the most remarkable finding in the preliminary data reveals that in horses with colitis, the whole bacterial population is very depleted.

“At this stage we are in the process of increasing our numbers to find significant differences in which bacterial taxa are more important,” says Arroyo. “Soon we hope to share which bacteria taxa are more promising for predicting dysbiosis in horses with gastrointestinal disease.”

The researchers are delving into a huge biobank of samples to identify potential markers of intestinal dysbiosis in horses, utilizing PCR testing as a faster and more economical alternative to the complex DNA sequencing technologies that have been used to characterize changes in microbiota thus far. The goal is to develop simple and reliable testing that veterinarians can take right to the barn that will result in early treatment and allow closer monitoring of horses at the first onset of GI disease.

Top Tips to Protect Digestive Health

Horses are hind gut fermenters who rely on adequate amounts of fiber in the diet to maintain healthy gut function.

Make dietary changes slowly as abrupt changes disrupt the microbiota.

Avoid large grain meals as huge portions of highly fermentable diets can be quite harmful to the microbiota and can also be a source of risk for developing gastric ulcers. Opt to spread out concentrates into several smaller rations.

Prevent long periods of fasting which can also lead to ulcers. Horses are continuous-grazers, and they need to have small amounts of feed working through their digestive system to keep it functioning optimally.

Have a parasite prevention program.

Provide fresh water 24/7 to maintain good hydration and keep contents moving smoothly through the GI tract.

Keep up to date on dental appointments.

Motion is lotion – turn out and exercise are extremely important to gut function.

In closing, Arroyo states, “These top tips will help keep the horse happy and the gastrointestinal tract functioning properly.”

A New Look at Lameness

Words - Jackie Zions (interviewing Dr. Koenig)

Prevention is the ideal when it comes to lameness, but practically everyone who has owned horses has dealt with a lay-up due to an unforeseen injury at some point. The following article will provide tools to sharpen your eye for detecting lameness, review prevention tips and discuss the importance of early intervention. It will also begin with a glimpse into current research endeavouring to heal tendon injuries faster, which has obvious horse welfare benefits and supports horse owners eager to return to their training programs. Dr. Judith Koenig of Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) spends half of her time as a surgeon and teacher with a strong interest in equine sports medicine and rehabilitation, and the other half as a researcher at the OVC.

Lameness is a huge focus for Koenig, whose main interest is in tissue healing. “I think over the past 20 or 30 years we have become very, very good in diagnosing the cause of lameness,” says Koenig. “In the past, we had only radiographs and ultrasound as a diagnostic tool, but by now most referral centers also have MRI available; and that allows us to diagnose joint disease or tendon disease even more. We are much better now [at] finding causes that previously may have been missed with ultrasound.”

Improvements in diagnostics have resulted in increased ability to target treatment plans. With all the different biologics on the market today, Koenig sees a shift in the management of joint disease with more people getting away from steroids as a treatment.

The following list is excerpted from Equine Guelph’s short course on lameness offered on TheHorsePortal.ca. It outlines the different diagnostics available:

Stem Cell Therapy

When asked for the latest news on research she has been involved in, Koenig proclaims, “I'm most excited about the fact that horses are responding well to stem cell treatment—better than I have seen any response to any other drug we have tried so far!”

Koenig has investigated the use of many different modalities to see if they accelerate tissue healing and has studied which cellular pathways are affected. Two recent collaborative studies have produced very exciting findings, revealing future promise for treating equine osteoarthritis with stem cell therapy.

In a safety study, Koenig and her team at the Ontario Veterinary College have shown equine pooled cryopreserved umbilical cord blood, (eCB) MSC, to be safe and effective in treatment of osteoarthritis.

“These cells are the ones harvested from umbilical cord blood at the time of foaling and then that blood is taken to the lab and the stem cells are isolated out of it,” explains Koenig. The stem cells are then put through a variety of tests to make sure they are free of infectious diseases. Once given a clean bill of health, they are expanded and frozen.

The stem cells harvested from multiple donors of equine umbilical cord blood [eCB, (kindly provided by eQcell), MSC] were compared to saline injections in research horses. “This type of cells is much more practical if you have a cell bank,” says Koenig. “You can treat more horses with it, and it’s off the shelf.” There were no systemic reactions in the safety study. Research has also shown no different reactions from sourcing from one donor or multiple donors.

In the second study, 10 million stem cells per vial were frozen for use in healing OA from fetlock chips in horses that were previously conditioned to be fit. After the fetlock chip was created, exercise commenced for six more weeks, and then osteoarthritis was evaluated by MRI for a baseline. Half the horses were treated with the pooled MSC stem cells, and the control group received saline before another month of exercise. Then MRI and lameness exams were repeated, and arthroscopy was repeated to score the cartilage and remove the chip.

Lameness was decreased and cartilage scores were improved in the group that received stem cell therapy at the time of the second look with arthroscopy.

Many diagnostics were utilized during this study. MRIs, X-rays, ultrasounds and weekly lameness evaluations all revealed signs of osteoarthritis in fetlock joints improved in the group treated with (eCB) MSCs. After six weeks of treatment, the arthroscopic score was significantly lower (better cartilage) in the MSC group compared to the control group.

“Using the MRI, we can also see a difference that the horses treated with stem cells had less progression of osteoarthritis, which I think is awesome,” says Koenig. “They were less lame when exercised after the stem cell therapy than the horses that received saline.”

This research group also just completed a clinical trial in client-owned horses diagnosed with fetlock injuries with mild to moderate osteoarthritis changes. The horses were given either 10 million or 20 million stem cells and rechecked three weeks and six weeks after the treatment. Upon re-evaluation, the grade of lameness improved in all the horses by at least one. Only two horses presented a mild transient reaction, which dissipated after 48 hours without any need for antibiotics. The horse’s joints looked normal, with any filling in the joint reduced.

There was no difference in the 18 horses, with nine given 10 million stem cells and the other nine 20 million stem cells; so in the next clinical trial, 10 million stem cells will be used.

The research team is very happy with the results of this first-of-its-kind trial, proving that umbilical cord blood stem cells stopped the progression of osteoarthritis and that the cartilage looked better in the horses that received treatment. The future of stem cell therapy is quite promising!

Rehabilitation

Research has shown adhering to a veterinary-prescribed rehabilitation protocol results in a far better outcome than paddock turn out alone. It is beneficial for tendon healing to have a certain amount of controlled stimulation. “These horses have a much better outcome than the horses that are treated with just being turned out in a paddock for half a year,” emphasizes Koenig. “They do much better if they follow an exercise program. Of course, it is important not to overdo it.”

For example, Koenig cautions against skipping hand-walking if it has been advised. It can be so integral to stimulating healing, as proven in recent clinical trials. “The people that followed the rehab instructions together with the stem cell treatment in our last study—those horses all returned to racing,” said Koenig.

“It is super important to follow the rehab instructions when it comes to how long to rest and not to start back too early.”

Another concern when rehabilitating an injured horse would be administering any home remedies that you haven't discussed with your veterinarian. Examples included blistering an area that is actively healing or applying shockwave to mask pain and then commence exercise.

Prevention and Training Tips

While stating there are many methods and opinions when it comes to training horses, Koenig offered a few common subjects backed by research. The first being the importance of daily turnout for young developing horses.

Turnout and exercise

Many studies have looked at the quality of cartilage in young horses with ample access to turn out versus those without. It has been determined that young horses that lack exercise and are kept in a stall have very poor quality cartilage.

Horses that are started early with light exercise (like trotting short distances and a bit of hill work) and that have access to daily paddock turnout, had much better quality of cartilage. Koenig cited research from Dr. Pieter Brama and similar research groups.

Another study shows that muscle and tendon development depend greatly on low grade exercise in young horses. Evaluations at 18 months of age found that the group that had paddock turnout and a little bit of exercise such as running up and down hills had better quality cartilage, tendon and muscle.

Koenig provides a human comparison, with the example of people that recover quicker from injury when they have been active as teenagers and undergone some beneficial conditioning. The inference can be made that horses developing cardiovascular fitness at a young age stand to benefit their whole lives from the early muscle development.

Koenig says it takes six weeks to regain muscle strength after injury, but anywhere from four to six months for bone to develop strength. It needs to be repeatedly loaded, but one should not do anything too crazy! Gradual introduction of exercise is the rule of thumb.

Rest and Recovery

“Ideally they have two rest days a week, but one rest day a week as a minimum,” says Koenig. “I cannot stress enough the importance of periods of rest after strenuous work, and if you notice any type of filling in the joints after workout, you should definitely rest the horse for a couple of days and apply ice to any structures that are filled or tendons or muscles that are hard.”

Not purporting to be a trainer, Koenig does state that two speed workouts a week would be a maximum to allow for proper recovery. You will also want to make sure they have enough access to salt/electrolytes and water after training.

During a post-Covid interview, Koenig imparted important advice for bringing horses back into work methodically when they have experienced significant time off.

“You need to allow at least a six-week training period for the athletes to be slowly brought back and build up muscle mass and cardiovascular fitness,” says Koenig. “Both stamina and muscle mass need to be retrained.”

Watch video: “Lameness research - What precautions do you take to start training after time off?”

The importance was stressed to check the horse’s legs for heat and swelling before and after every ride and to always pick out the feet. A good period of walking is required in the warmup and cool down; and riders need to pay attention to soundness in the walk before commencing their work out.

Footing and Cross Training

With a European background, Koenig is no stranger to the varying track surfaces used in their training programs. Statistics suggest fewer injuries with horses that are running on turf, like they practice in the UK.

Working on hard track surfaces has been known to increase the chance of injury, but delving into footing is beyond the scope of this article.

“Cross training is very important,” says Koenig. “It is critical for the mental and proper musculoskeletal development of the athlete to have for every three training days a day off, or even better provide cross-training like trail riding on these days."

Cross-training can mitigate overtraining, giving the body and mind a mental break from intense training. It can increase motivation and also musculoskeletal strength. Varied loading from training on different terrain at different gaits means bone and muscle will be loaded differently, therefore reducing repetitive strain that can cause lameness.

Hoof care

Whether it is a horse coming back from injury, or a young horse beginning training, a proficient farrier is indispensable to ensure proper balance when trimming the feet. In fact, balancing the hoof right from the start is paramount because if they have some conformational abnormalities, like abnormal angles, they tend to load one side of their joint or bone more than the other. This predisposes them to potentially losing bone elasticity on the side they load more because the bone will lay down more calcium on that side, trying to make it stronger; but it actually makes the bone plate under the cartilage brittle.

Koenig could not overstate the importance of excellent hoof care when it comes to joint health and advises strongly to invest in a good blacksmith. Many conformational issues can be averted by having a skilled farrier right from the time they are foals. Of course, it would be remiss not to mention that prevention truly begins with nutrition. “It starts with how the broodmare is fed to prevent development of orthopedic disease,” says Koenig. Consulting with an equine nutritionist certainly plays a role in healthy bone development and keeping horses sound.