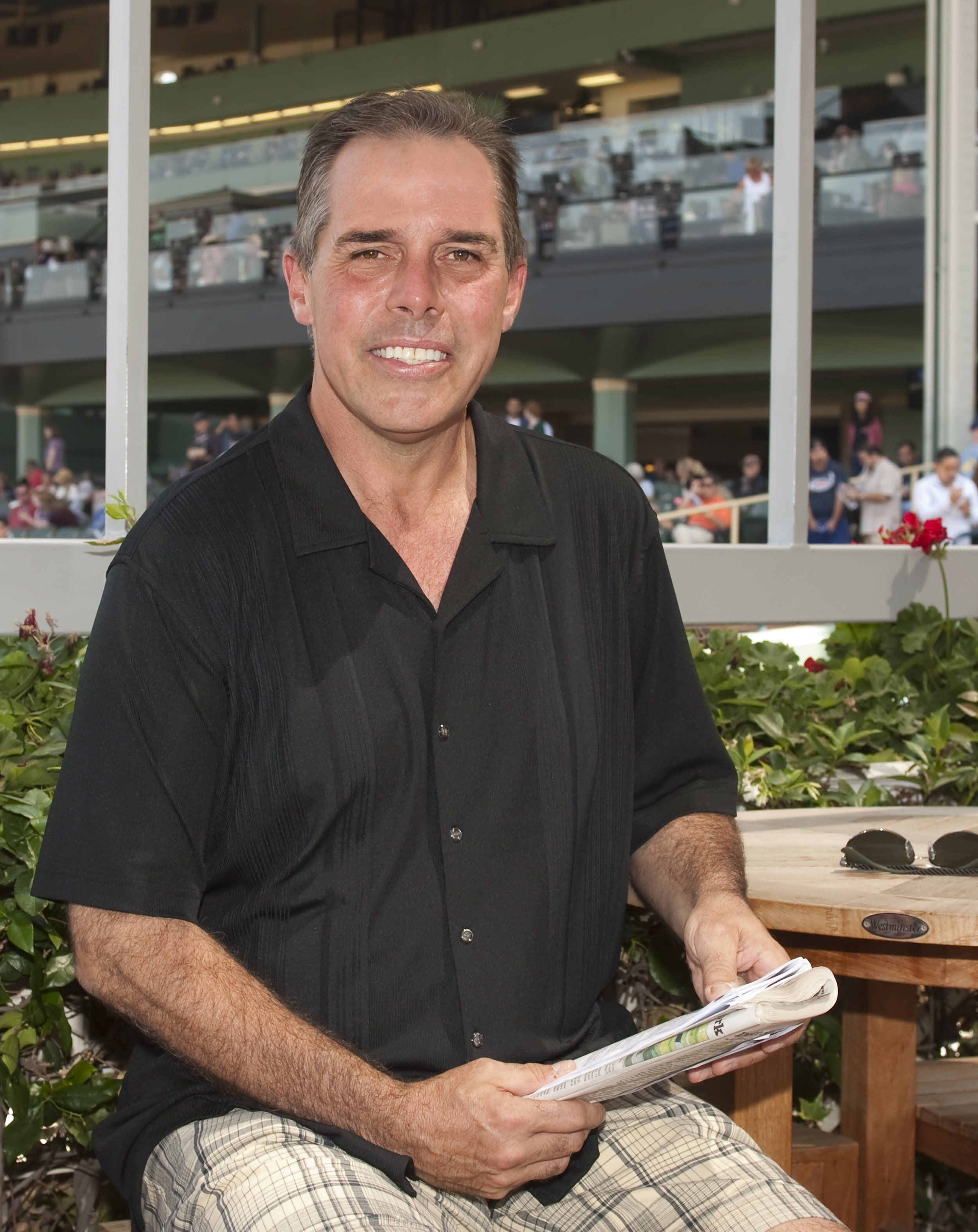

All in the Family: Larry Rivelli Finds Another Level Thanks to Trust, Relationships

Article by Jennifer Kelly

In an era of super trainers with even larger owners behind them, the sport of horse racing still has at its foundation a legion of owners and trainers who operate on a smaller scale but nonetheless make big news on the racetrack. These are the men and women who have built their lives around the equine athletes in their care, their knowledge passed down through generations, supporting racetracks at all levels. These are breeders, owners, trainers, and many more who think of themselves as a family, one bonded by the love of horses.

For Larry Rivelli, a third-generation horseman, family is at the heart of his barn. Lessons learned by his grandfather’s and uncle’s sides have informed his approach to his work and his relationships with owners as he takes his career to a new level.

Windy City Boy

A Chicago native, Rivelli comes by his horsemanship honestly: his late grandfather Pete and uncle Jimmy DiVito both made their livelihoods in the sport. Pete made his life with horses, preferring his education on the track rather than in a schoolroom as early as 5th grade. He galloped horses for Bing Crosby, worked with horses during his stint in the Army, and then returned to racing in Chicago and California afterward. He trained for Louis B. Mayer, Harry James and Betty Grable, and Lindsay Howard, son of Charles Howard, owner of the famed Seabiscuit. He returned to Chicago for good in the 1960s and spent the rest of his career there.

Son Jimmy followed him into the business as well, his home base also in Chicago. Alongside both worked Larry Rivelli, son of Pete’s daughter Julie and Jimmy’s nephew. While his mother worked, “I stayed with my grandparents a lot. And it was just racing forms and programs on the kitchen table every day. I would read them. My grandfather would read them. We would just go back to the track. The track was eight minutes from the house.”

DiVito put his grandson to work cleaning stalls when he was nine or ten years old; later, he worked with his uncle Jimmy during school breaks, both giving Rivelli opportunities to learn the skills that would serve him when he went out on his own. The young Rivelli always had athletic ambitions at heart – “I either wanted to be a professional football player or a horse trainer,” – leading the state in rushing in his junior and senior years of high school before going on to St. Cloud State University in Minnesota. There, he played wide receiver and kick returner for the Huskies, and after graduation, found his opportunities at the next level were limited. Instead, he turned to the family business.

“[Training] was always just something that I really was enamored with as a little kid. That's what I really wanted to do, train racehorses, and I think that's why I've been so successful,” Rivelli shared. “It's just not even a job to me. Being a horse trainer, it's just a way of life. You either got to love it or you're not going to be able to do it. You have to have a passion for it.”

With his mother Julie and stepdad Victor in his corner, Rivelli went out on his own as a public trainer, taking out his license in 1999, the year after his grandfather died. He made Chicago his base, staying close to home while building his business and his family. On the home front, Rivelli has daughter Brittany, a competitive synchronized skater, and son Dominic, a collegiate hockey player, continuing the family’s athletic tradition.

His foundation made the transition from football to training an easy one, a natural progression for a young man who grew up idolizing his famed grandfather and uncle.

Training Methodologies

Rivelli’s background as a football player and his emphasis on family has inspired his approach to training since he hung out his shingle as a public trainer 25 years ago. His experience as an athlete has cultivated an awareness of the relationship between how a horse feels physically and how they will perform on the racetrack. While such a correlation might seem obvious, first-hand understanding of that dynamic helped Rivelli manage his equine athletes in a manner that emphasizes both fitness and work ethic in his starters.

“If you've been an athlete, you’ve dealt with injuries and setbacks and therapy differently than people that, let's just say, never played a sport,” Rivelli shared. “It's a sport, and horses get hurt. They want to try to work through these injuries where horses are so much bigger and heavier than humans. And they're putting all that pressure on about the size of our legs. So, if something goes wrong, I take steps back and time heals everything most of the time.”

Dr. Jean White, an Ocala, Florida veterinarian and part of the Rivelli team, describes the trainer’s approach as one where “he would rather do less and have the horse want to do more. If he doesn't think the horse can win, he doesn't want to run it. If it needs rest, let it rest. If it needs its feet fixed, fix them. If it needs us to evaluate it and figure out why, then do that.”

“It's just like a human being. People go to the gym and absolutely kill themselves every day, and then they don't feel so great,” she observed. “It's a different style. It's a different thought process, a different mentality.”

That emphasis on fitness means the trainer is “a four to six weeks [between races] guy. Occasionally or situationally, you'll have something come up sooner.”

“Back in the day [2002-2006], I had a turf sprinter, Nicole's Dream, and she was really, really good,” Rivelli remembered. “They had a boys race and a girls race in Chicago, and they were separated by a week. There was no other races on the planet for her for three and a half months, so I ran her back. And she won. She was an extremely sound horse, too, so it made that decision easier.”

The native Chicagoan prefers to run his horses in winnable spots so that they are not asked to give too much over and over again: “I take pride in running most of my horses. I'm a bad loser, so I won't run one if I don't think they can win, really. I'll take as much time as we need to get them to that point. We'll even stop on them and back off and send them home and turn them out and bring them back. If something's not going right during the process instead of getting ready, we're just going to stop. Horses, they only got so many races in them.”

Instead, the trainer prefers to give a horse time off and only bring them back “when they’re 100% and ready to go. And that's why he has horses that run ‘til they're eight,” White shared. “They're wanting to train, wanting to run.”

Vincent Foglia of Patricia’s Hope, one of Rivelli’s biggest owners, points out what he sees is behind the trainer’s success: “He does the same thing every day, seven days a week. He's got that set list. He's always looking at that big sheet. He's always writing down who's going to be walking, who's going to be galloping, who's breezing. It's like clockwork. His consistency, the amount of time he puts into it, is very regimented. Very consistent and meticulous. That's his approach. That's great. And he always does what's right by the horse every time. That's first and foremost.”

That emphasis on consistency and care has helped the third-generation trainer build a solid career in his native racing scene. In 2000, his first full season, Rivelli’s barn had 57 starts and an 8-7-9 record, for 14% win and 42% win-place-show percentages; in 2024, his 25th season, he had 279 starts and a record of 89-45-26, for 25% win and 50% WPS percentages. Nationally, Rivelli has been in the Top 50 by wins in 12 out of the last 15 years. His career win percentage of 26% and WPS of 56% reflects his ability to put his horses in the right spots for success. To this point in his career, much of that has been in the Chicago area.

He won his first training title at Arlington Park in 2011, and then was the track’s leading trainer from 2014 to its final season in 2021. Rivelli then shifted his stable to Hawthorne, the lone racetrack remaining in the Chicago area, and won leading trainer titles there for their 2021-2023 spring meets. This native son emphasizes his roots, saying “I'll still consider myself a Chicago trainer [even] if there are no tracks in Illinois.”

For his winter racing, Rivelli has horses stabled in a private barn at Fair Grounds in New Orleans, one he purchased from former owner Louis Roussel, an acquisition that signaled his intent to make a long-term investment in Louisiana. “The state is thriving as far as races. They got four tracks in the state, and they're all doing their thing,” Rivelli shared. In addition, he has horses at Turfway Park near Cincinnati and then shifts back to his home base at Hawthorne the rest of the year. In addition to being on home turf there, the track’s proximity works in his favor as “it's easier on the help and on yourself,” plus “I [can] ship to Churchill, which is four hours. To ship to Keeneland is three and a half hours, three hours to Indiana. So, all these tracks around us, it's not a big deal to ship. You ship over a couple of days before or a week before. I like the fact that the horses are all under one roof.”

Staying in this area also helps Rivelli maintain the relationships that he has built with owners like Patricia’s Hope and Richard Ravin, both of whom found ample success at the Windy City’s racetracks. The bonds the trainer has formed with those two owners exemplify his approach to doing business: keeping it all in the family.

Bonded with Success

Two ownership mainstays in the Rivelli barn include Richard Ravin and the Foglia family, the Chicago-area entrepreneurs-turned-philanthropists behind the Patricia’s Hope stable. Ravin’s investment in the sport includes both his current racing-age horses in Rivelli’s barn and the broodmares that Dr. White keeps on one of her Ocala-area properties. Both owners have been with Rivelli for more than a decade and count the trainer as more than just a partner in the sport. They are a team, and as the trainer puts it, “these are my guys, and they know that. It’s very rare that you have people like that that are in the game with you, and they are happier for you when we win than they are for themselves.”

An Ohio native who settled in the Chicago area in the 1960s, Ravin retired from the insurance business and got into horse ownership after a chance encounter with a friend who had bought into Nicole’s Dream, one of Rivelli’s earliest successes. Ravin partnered with Dare to Dream Stable in the sprinter and then expanded into breeding as well. He met Rivelli through “the four or five guys that we got together as a horse ownership group, and they're the ones that picked him. I didn't know him. I got to know Larry since we had the Nicole's Dream and a couple others when we made a couple of purchases early on, back in 2000, 2001. And I've been together with Larry ever since.”

The Foglia family got into the ownership game after years of trips to Arlington that became bonding moments for mother Patricia and son Vincent, Jr. Father Vincent founded Sage Products, Inc., a medical supply company in Cary, Illinois. The company’s prosperity allowed the family to start the Foglia Family Foundation, which supports health care and education in the Chicago area. The younger Foglia wanted to expand their love of the sport into ownership in 2010. They met Rivelli when they wanted to claim a horse and immediately hit it off: “I knew he was winning most of the races at Arlington. That was it. I knew nothing. I got a quick introduction to him on the phone because we were going to claim a horse at Gulfstream. We just hit it off. We have similar backgrounds and are real close in age and became friends really quickly,” Foglia remembered.

“He is like my brother that I never had. We are like two very similar people as far as just the way we are and ended up just being a great partnership and an even better friendship,” the trainer shared. That friendship led to a partnership that dominated at Arlington Park. While Rivelli was leading trainer for much of the track’s final decade, Patricia’s Hope was the leading owner. Rivelli also introduced the Foglias to Ravin, which led to the trainer and owners forging a solid partnership behind horses like Grade 3 stakes winner Jean Elizabeth and Grade 2 turf sprinter One Timer.

Patricia’s Hope also has brought Rivelli Breeders’ Cup success. Their Cocked and Loaded was the trainer’s first Breeders’ Cup starter at Keeneland in 2015, and turf sprinter Nobals gave both their first Breeders’ Cup winner with his neck victory over Big Invasion in the Grade 1 Breeders’ Cup Turf Sprint at Santa Anita in 2023. The Foglias were also partners in Two Phil’s, second in the 2023 Kentucky Derby behind Mage. They bought into the colt, who became both the trainer’s and the owners’ first Derby starter, on Rivelli’s recommendation.

“I'm tight with Larry. I'm his biggest investor. I'm his biggest owner. And we're very good friends,” Foglia shared. “The Sagans, who owned [Two Phil’s], they were trying to sell that horse from the sale on out. They wanted the money. I'm like, should I go in? He [Rivelli] goes, ‘Absolutely.’ I said, I'll take as much as I could get. I ended up getting 80%.”

That trust is at the heart of Rivelli’s relationship with his owners. As Ravin puts it, “First of all, he's a very loyal guy and he just totally exemplifies honesty, integrity, and character. Those are the type of people I really want to be associated with. When you got a person like Larry, it then becomes a friendship, even more so than the partnership.” The Foglias echo that sentiment, the younger Vincent sharing that the trainer “always tells the truth. He's always working hard, and he does right by the horse, and he's honest about everything.”

That honesty translates into a trust that makes the relationship between Rivelli, Ravin, the Foglias, and Dr. White a collaborative effort where “there is plenty of room between the owners and the two of us for somebody to raise their hand and go, ‘Wait. What are we doing? Wait a second.’” White observed. “That is allowed. Every once in a while, somebody goes, ‘yeah, we need to look at the situation differently.’”

In the end, what each appreciates about working with team Rivelli is “the friendship, the team working together, being honest and direct, being upfront, it's just a tremendous experience,” Ravin shared. “My wife threw a very special 80th birthday party for me down here last year. And there was Larry flying from Chicago, coming down and being there as a surprise. So that's the person, that's the relationship, and that's as good as I can give an example of what a quality person he is.”

Rivelli echoes those sentiments whenever he talks about owners like Ravin and the Foglias. “I'm so fortunate right now that the people that I have, my main owners, I can literally say, I love these people,” the trainer shared. “These are my people. If they said tomorrow we quit, I'd say, ‘All right, where are we going for breakfast?’ These are my guys. And they know that, and I know that. And it's very rare that you have people like that that are in the game with you, and they are happier for you when we win than they are for themselves. Like me, I'm so happy for my guys, like for Vinnie and his mom and Richard Ravin and when they win, than I am for myself.”

So much of the success a trainer builds over the course of their career depends on the relationships they cultivate with racetrack officials, jockeys, veterinarians, and most of all, owners. As Dr. White shared, the dynamic between Rivelli and his owners can best be summed up with “Vinnie would just [say], ‘okay, whatever you want to do, whatever you think is best, Riv. That's what we're going to do.’”

That kind of trust, especially when Arlington closed leaving them without the site of much of their early success, led to a rethinking of their business model and one of Rivelli’s highest profile horses to date.

A Change in Perspective

Rivelli and team may have dominated Arlington’s last decade, but the track’s closure meant Patricia’s Hope, Richard Ravin, and their trainer needed to rethink their approaches to racing going forward. While they have found success after shifting to Hawthorne, they have changed the type of horses they want in their barn. “The game plan for the owners and myself has changed. Whether we're at Hawthorne or Turfway or Fair Grounds, that's really not important. It's all just a matter of what's running,” the trainer observed. “Focusing our efforts on buying more expensive horses, so to say, or better horses instead of filling the barn with the 20s, 30s, 8s, 12s, because you wanted to have one for each spot. Now we're looking for the best horses we can get all the time.”

That shift to quality over quantity means a multi-layered approach to acquiring horses, mostly through either private purchases or through sales like the Ocala Breeders’ Sales Two-Year-Olds-in-Training Sale. “Our thing is we really do a little bit of everything,” Rivell shared. “There's no method to this. There's no foolproof approach. If we just go to the sale every year, the two-year-old sales, we're going to get couple, of course. I bought One Timer, who has made over a million dollars, as a yearling for $21,000 on the way out of a sale just walking out. I thought I had a big budget that year. I spent a lot of money. That was the cheapest horse I bought. He was little. He's put together good, and I liked him. He looked like he would be fast. He grew up into this beauty, and he's woin over a million dollars. He's just a real nice racehorse.”

Nobals, on the other hand, “we bought him after he ran, so he was a proven horse.” Rivelli purchased the gelding by Noble Mission out of the Empire Maker mare Pearly Blue for $150,000 from owner/trainer Leland Hayes. “And then at the [2022 OBS] two-year-olds in training sale we saw Two Phil’s. The breeder gave him to me, said he wants to sell the horse. Patricia's Hope [the Foglia family] bought the piece that the guy wanted to sell.” Add in Richard Ravin’s broodmares as well as Two Phil’s now standing at stud, Rivelli and company also “breed a few. [Vinnie] will be breeding a couple because he stayed in for a percentage on Two Phil’s. So, we're going to have a lot of action. And you never know where it's going to come from.”

This new focus brought Rivelli his three most successful seasons to date, including 2023, with $4.9 million in earnings and a win percentage of 31%. “It's just a coincidence, but it's funny. The first year we decided to change the motto was the year we won the Breeders’ Cup [with Nobals] and almost won the Derby [with Two Phil’s],” he shared. “We couldn't make a wrong move that year at all. It was great.”

As his highest profile horses to date, One Timer, Two Phil’s, and Nobals are the best illustrations of the trainer’s approach to buying, preparing, and racing his horses. All three were acquired in different ways, each catching Rivelli’s attention based on their physical appearance or performance; Nobals’s lone start at Presque Isle at age two prompted Rivelli to pursue buying the gelding. After acquiring the talent comes planning a campaign. Even if the trainer envisions a specific goal for a horse, like the Kentucky Derby or the Breeders’ Cup, he still approaches the season start by start.

Nobals was already a stakes winner prior to his 2023 Breeders’ Cup win, taking the listed Arlington-Washington Futurity at age two and following that with two black-type stakes wins at Turfway at age three, all on synthetic. Rivelli also tested him on turf: his first win at age four came in the Grade 2 Twin Spires Turf Sprint on the Kentucky Derby undercard at Churchill Downs, a three-quarter-length victory that had Rivelli circling the Breeders’ Cup at Santa Anita on his calendar. To get there, the gelding went to Horseshoe Indianapolis and won the William Garrett Handicap; to Saratoga, where he was second to Cogburn in the Grade 3 Troy; and then to Colonial Downs for the Da Hoss, which he won by a head, before his trip out west to Santa Anita. Each start was about four weeks apart with eight weeks between the Da Hoss and his win in the Turf Sprint. With Nobals returning for his six-year-old season, Rivelli knows his sprinting star has fewer options if he wants to build toward a second try at the Breeders’ Cup: “For Nobals, for those type of individuals, there are less select races for a five-eighths turf specialist and sprinter. Wherever they're at, you got to go to.”

When Two Phil’s (Hard Spun – Mia Torri, by General Quarters) landed in his barn in 2022, Rivelli was not thinking about the Kentucky Derby trail until his Grade 3 Street Sense win over a sloppy Churchill Downs surface, his third win in five starts at age two. That 5¼-length win came around two turns, the colt’s second try at 1 1/16 miles after finishing out of the money in the Grade 1 Breeders’ Futurity at Keeneland. After that, “we took a little closer order on what races we were going to run him in and stuff like that,” the trainer remembered. “Now, if he had run a third in that race, maybe I wouldn't have gone the route I went, but he won pretty convincingly.”

Trying for the first Saturday in May “always is in the back of your mind, but when you don't have the opportunity or you don't have those type of horses all the time, it's hard,” Rivelli observed. “I’ve had one or maybe two. It's because I know what it takes to have those horses. I could have taken several horses that I've made hundreds of thousands of dollars with by running them in other races besides those races and try to qualify for the Derby, but I knew they weren't good enough, even though other people or other trainers might have gone down that road just for the fact to go down it.”

The Street Sense win showed Rivelli and the partnership, including Patricia’s Hope, that the colt had the potential for a try at the Run for the Roses. To get there, the trainer sent his colt to Fair Grounds, where he was third behind Angel of Empire in the Grade 3 Lecomte that January and then second behind Instant Coffee in the Grade 2 Risen Star four weeks later. Rivelli then sent his colt to Turfway for the Grade 3 Jeff Ruby Steaks, which Two Phil’s won by 5¼ lengths. Six weeks later, Rivelli was on the backside of Churchill Downs with a serious Derby contender and a barrage of media seeking out the chestnut colt and his Windy City connections.

Two Phil’s and regular rider Jareth Loveberry, another Arlington refugee, entered the gate on the first Saturday of May as one of the four horses with single digit odds, fourth choice behind Angel of Empire, Tapit Trice, and Japanese hopeful Derma Sotogake. Loveberry stalked the pace set by Verifying and Kingsbarns through the first mile and then edged clear by 1½ lengths with three furlongs to go. Mage mounted his bid on their outside, building enough momentum to pass Two Phil’s in the final furlong. Though they were not victorious, “the overall day, with the Derby and with Nobals winning the half million-dollar race, that was probably the best day,” Rivelli shared.

The trainer then broke with tradition and opted not to send Two Phil’s to Pimlico for the Grade 1 Preakness Stakes two weeks later. “We ran in the Derby, ran in the biggest, the baddest race in the planet, and we almost won,” Rivelli reflected. “What do you do now? Okay, that's done. Horse is doing great. Let's find spots where we can't lose. Not what we can maybe win, where we can't lose.”

That choice to skip the Preakness reflects this veteran trainer’s philosophy about both spotting his horses and timing their starts. The two-week turnaround makes the two races “too close, especially that caliber of race. I know they've been talking about backing it up, which I think would be a good thing.”

Instead, Rivelli chose to follow up Two Phil’s second-place turn at Churchill Downs with a jaunt to Thistledown for the Grade 3 Ohio Derby six weeks later. “There's only so many times he's going to ask a horse to give a hundred percent of its effort,” Dr. White shared. “He's much more likely to ship to some other racetracks away from the crowd and ask them to run to 70% or 80% of their potential and leave that 100% for a spot here or there.” The nine-furlong stakes was another tour-de-force performance from the son of Hard Spun. Once again, he laid just off the pace, took over in the stretch, and finished strong, beating second-choice Bishops Bay by 5¾ lengths.

“He was spectacular that day. We were so glad to see that he was back, and we was really looking forward to what he was going to do next,” Rivelli remembered. “We were all high fiving on the plane, drinking, partying on the way back. And then the next day, it's like, ‘Oh, my gosh.’ Hit right in the gut.”

After his Ohio Derby win, the colt started showing lameness in his left front ankle. Radiographs showed that the issue was a fractured sesamoid. The injury was not life-threatening, but it was career-ending. Two Phil’s was retired with a 10-5-2-1 record and $1,583,450 in earnings. He now stands stud at WinStar Farm, with both Rivelli and the Foglias retaining shares.

The veteran trainer was realistic about Two Phil’s injury and retirement. “The prognosis is generally not very good. His was not that bad, but it wasn't insignificant. If you gave him a year off, he probably could be fine, or you could go back to training him,” Rivelli observed. “Me, like I said, being an athlete, knowing this stuff, you could be fine, but you're going to lose a step or two or three. What will be the point? What does he need to prove? He doesn't owe us anything. You always want to do right by the horse.”

With 65 to 70 horses and 30 employees in his barns, with a close-knit group of owners and team that have helped take him to a new level, Larry Rivelli is ready for 2025 and beyond.

The Next Thing

For this Chicago native, the name of the game is adapting. “Life throws stuff at you. You got to adapt anyway. And that's the key to it is, if you can keep adapting, you're on good footing,” Rivelli shared. “It's like coaching a football team. You got to keep the players healthy as you can for as long as you can. Meanwhile, trying to win races and be in the right spots where you're not going to run fifth, sixth, eighth, and put miles on your horse and not make your owner money.”

With racing in his hometown down to one racetrack, this native son hopes that Hawthorne will add a casino to its facility, which will help keep the sport afloat in Illinois as such additions have elsewhere. In the meantime, his fellow Chicagoans Richard Ravin and the Foglia family will be along for the ride with complete trust in the man caring for their horses.

“I have never thought about calling, watching, doing, or anything else with anybody except Larry,” Ravin shared. The retired insurance executive cites his trainer’s best advice about racing – having patience – as the foundation behind his confidence: “If we're patient and care about our horses, I think we'll be rewarded both for doing the right thing because it's the right thing to do, and we'll be rewarded by getting the wins that we need to get to make it a viable operation.”

Vincent Foglia, Jr. received similar advice from Rivelli: “Don't get too excited about one start. Don't try to rush anything. Do what you think the horse can do. Stay within your limitations of the horse you have and its ability. Relax.” That perspective got the Foglias within a length of a Kentucky Derby. It is an experience that the family behind Patricia’s Hope would be willing to repeat, and they “would only do it with Rivelli. I've had people who want me to go in with them on other horses, and I will say, ‘Sure, but who do you want to train?’ Anyone that says different from Riv, I say, ‘I'm out.’”

The trainer’s 2025 does include another possible Derby contender, Murdock (Vekoma-Saucy At Midnight, by Midnight Lute), owned by Carolyn Wilson. “He won first time out by 10. He ran in one of the first two-year-old races of the year in Chicago. And he won like I thought he would,” Rivelli shared. “And then he had a couple of setbacks, and then he had a testicle up in his stomach, and we had to operate. Then he had something wrong with his foot. But he's a serious horse.”

The year also includes another potential Breeders’ Cup campaign for Nobals, who is set to make his first start soon; and for One Timer, the new year brings a possible return to Kentucky Downs, the site of his Grade 2 Franklin-Simpson victory and a track that the gelding has run well over.

“He [Nobals] can run in the race because he's won the Breeders’ Cup, and he's a Grade 1 winner, so he probably will get in as long as I spot his races. I probably would either turn him out for a little bit, but he was lightly raced last year, and he's doing really good. I don't think I want to campaign him from now all the way to the Breeders’ Cup. That would be one whole year of training,” Rivelli shared.

“One Timer, I'll probably keep him on the Polytrack and then run him in a Churchill or Ellis race, places like that,” the trainer said. “He's a little different horse to train, a little different horse to keep going. So, when he's going good, we're going to keep him in action.”

As for goals in this new year, short and long, Larry Rivelli is a realist. “Short-term goals is to wake up tomorrow,” the native Chicagoan laughed. “If you start making too many long-term plans in this game, I think it ends up biting you in the ass because you push yourself. It's like, okay, I got the next three races for this horse, and then tomorrow something happens.”

“The owners I have are great. They're not sweating, saying ‘we got to run.’ They let me do my thing, which is great. And I think that's why we've been so successful,” he shared. “It's just a pretty good team. And my help, the people that work for me. Obviously, none of this would happen if I didn't have them.”

On race days big and small, his grandfather is never far from his thoughts, especially when Rivelli is getting his picture taken in the winner’s circle. “When I point, is actually I'm pointing to my grandfather,” this third-generation horseman shared. “I used to point up in the sky to him. That's back at him.”

For Larry Rivelli, racing is all about family, both blood and chosen, and the trust in each other that brings the successes they have all enjoyed. And he would not have it any other way.

Barry Schwartz

Article by Bill Heller

What is more exciting for an owner and breeder than a two-year-old colt with talent? Former New York Racing Association Chairman of the Board and CEO Barry Schwartz’s New York-bred colt El Grande O certainly gives him reasons to dream. Off a head loss in the Funny Cide Stakes at Saratoga on August 27th, El Grande O dominated five rivals on a sloppy track at Aqueduct September 24, scoring by 8 ¼ lengths as the 3–5 favorite in the $125,000 Bertram F. Bongard Stakes under José Ortiz. Linda Rice trains the son of Take Charge Indy out of Rainbow’s Song by Unbridled’s Song who has two victories, three seconds and one third from his first six starts with earnings of $204,000.

El Grande O is Schwartz’s 26th Thoroughbred to win more than $200,000—a list that includes his top earners Boom Towner, Voodoo Song, The Lumber Guy, Kid Cruz, Princess Violet, Three Ring and Fire King. All of them earned between $700,000 and $1 million.

Now 81, Schwartz and his wife Sheryl still reside at their farm, Stonewall Farm, in northern Westchester County, with a second home on the ocean in California. Schwartz keeps busy playing the markets and running his horse stable.

The Calvin Klein years

It seems like forever since he and his childhood pal Calvin Klein, took Calvin Klein Inc. from a $10,000 initial investment to a global operation, which they sold for $430 million smack in the middle of Schwartz’s four-year reign at NYRA.

Schwartz and Klein, who both lived in the Bronx and had fathers who owned grocery markets in Harlem, went into their first partnership when they were nine, reselling newspapers and collecting bottles. “We’d go to the newsstand when the papers came in early evening,” Schwartz said. “We bought them for a nickel and sold them for a dime. We’d go to all the hotels, especially in the summer. On a good night, we’d make $3 apiece. That was a big deal then.”

When they began Calvin Klein Inc., they rented room 613 in the New York Hotel in Manhattan. The front door was open and faced the elevator. Calvin had the six women’s coats he had manufactured with Barry’s investment.

One morning the elevator stopped on the sixth floor. One passenger walked out while another noticed the coats and got off. That passenger was Don O’Brien, the general manager of Bonwit Teller, one of New York’s most fashionable stores.

Schwartz was home when Klein called him with great news: “You’ll never believe this. I got a $50,000 order from Bonwit Teller!” Schwartz replied, “Who’s Bonwit Teller?”

He figured it out, and Calvin Klein, Inc. went onto incredible success.

The NYRA Years

In the four years Schwartz served as Chairman of the Board and CEO of NYRA from October 2000, to October 2004, racing in New York reached a pinnacle, a shining example of how racing should be operated—when fans and bettors mattered; when the right people in the right positions made the right decisions.

It didn’t last. When Schwartz departed out of utter frustration from battling politicians and their inept decisions, racing in New York was never the same. It was almost like it was a mirage—a wonderful mirage.

But it was real. It was Camelot at Aqueduct, Belmont Park and Saratoga.

That he did this while he continued to operate Calvin Klein, Inc. is remarkable. To do it, he had to commute 30 to 45 minutes through New York traffic every morning. And he did NYRA pro bono.

Why? Because he cared deeply about racing, specifically New York racing. Schwartz’s goal at NYRA was straightforward: “to make New York racing No. 1 in the world.”

Schwartz, who had been a member of the NYRA Board since 1994, was approached by acting CEO and Chairman of the Board Kenny Noe, who had decided to retire in the fall of 2000. “I was excited to be asked,” Schwartz said. “I was flattered. My two biggest supporters were Kenny Noe and Dinny Phipps (head of the Jockey Club). Dinny pushed for it. I was kind of flabbergasted, but I was thrilled. I got really energized. It gave me purpose, something to sink my teeth into. I went gangbusters, all in.”

Klein backed Schwartz’s decision. “The best thing that happened was that there was a long time before I took over,” Schwartz said. “I could work out the schedule I’d have to use. I spoke with Calvin about it. He thought it was a good idea. He always said, `If you’re near a phone, what’s the big deal?’”

So he did both. “At NYRA, my first two years were wonderful,” Schwartz said. “My first two years were a honeymoon. The next two years were just horrible.”

On the first day Schwartz took over NYRA and the three racetracks it operates—Belmont Park, Saratoga and Aqueduct—Schwartz went on NYRA’s new website, which had been designed by his son-in-law Michael, and asked fans and bettors what changes they wanted NYRA to make.

Then he made the changes, empowering fans, bettors and handicappers because he has always been a fan, a bettor and a handicapper.

This was a seismic shift in racetrack management, giving the people who support racing with their hard-earned cash every day a chance to impact the process.

“On the website, we asked fans what they wanted,” Schwartz said. “We did that several times. Everybody loved that. The bettors could participate in the process.”

Bettors had never been asked that.

“It was genuine,” Bill Nader, former NYRA senior vice president, said. “He cared. He knew they cared. They shared the passion. It was a mind-blowing experience. It was exceptional, and I thought it was great that he heard their voice, that he gave them a seat at the table. He listened to what they said. He wanted to grow the business. He wanted to improve the business. Without consulting the customer, how do you do this?”

That initial fan survey on NYRA’s website received more than 4,000 responses. Schwartz responded by immediately making changes. Uniform saddle cloth pads—the 1 horse is red, the 2 horse is blue, etc.— made it easier to follow horses during a race. Claims, when someone purchases a horse that had just raced, were announced to the public. Barry also instituted a shoe board displaying each horse’s shoe type before every race.

A couple months after those changes, Schwartz said, “It really is true: talking to the fans is important. I’m going to continue involving the fans as long as I’m here. Without them, there’s no sport.”

On his first day, he promoted Bill Nader from Simulcast Director to Senior Vice President of Racing and watched Nader become one of the most respected racing officials in the world, serving as director of racing in Hong Kong for 15 years before becoming the president and CEO of the Thoroughbred Owners of California, June 21, 2022.

Schwartz said, “Bill was grossly underpaid. I didn’t want to lose him. When I reviewed the personnel and salaries, this guy was so underpaid; and I wound up signing him to a three-year contract. I wanted to make sure that he stayed. He was really close to me. When I got my people together, Bill was clearly the smartest guy in the room. He was the best guy I had.”

Nader told Schwartz, “Wow, I’m thrilled, but I’m surprised.” Schwartz responded, “No, I’ve been watching.”

Nader’s appreciation of Schwartz’s support and impact hasn’t subsided more than 20 years later. “From day one, he just got behind me. That’s a huge amount of trust. He made me. He was the one person that changed the course of my life, providing me with the opportunity at NYRA. Six years later, the door he opened for me at NYRA led me to Hong Kong. He changed the path of my life, and I will be forever grateful.”

Schwartz didn’t take long to help all his employees in the first year. “NYRA got $13 million from Nassau County because NYRA had been overbilled for taxes,” Schwartz said. “I gave everybody a five-percent raise and a five-percent Christmas bonus. It was a big deal for the employees. They had never gotten a Christmas bonus.”

There was a new vibe at NYRA, and you could feel it. “What differentiated Barry was Barry was a New York guy,” top jockey-turned TV commentator Richie Migliore said. “He created his success through hard work. He was as comfortable shooting pool in the jockey room as he was in the boardroom. I remember him beating Jorge Chavez, who thought he was a really good pool player. Barry smoked him.”

Breeders’ Cup 2001

There were many shining moments during Schwartz’s four years, perhaps none more important than supervising the 2001 Breeders’ Cup at Belmont Park just weeks after the tragedy of 9-11 had left a city and a nation broken.

Like every other person in America, Schwartz remembers vividly the horror of 9-11 unfolding: “I was home in New Rochelle, getting dressed and ready to go to the farm. We were building our house there. It was in the very beginning. I saw the first plane hit. I told Sheryl, some idiot just flew his plane into the Trade Center. A few minutes later, I’m driving to the farm, and we hear about the second plane hitting. We spent the whole day at the farm. It was a safe haven at a very scary time. Sheryl’s brother got my kids out of the city.”

Belmont Park, in Elmont, Long Island—just 12 miles from “ground zero”—had already been selected to host the 2001 Breeders’ Cup on October 27, less than two months later; and no one was quite certain if that was still going to happen. “We had conversations with everybody,” Schwartz said. “I was in the same camp as Dinny. I thought it was very important to show New York was alive and well.”

Breeders’ Cup President D.G. Van Clief Jr. issued a statement saying, “Obviously, on the morning of Sept. 11, the world changed, and it certainly changed our outlook on the 2001 World Thoroughbred Championships. But it is very important for us to stay with our plan. We’d like it to be a celebration and salute to the people of New York.”

Schwartz leaned heavily on Nader to get it done. “It was challenging,” Nader said. “We literally worked 18 hours a day. There was the normal preparation. Then the security side. Nobody minded the extra hours. We wanted to be sure we didn’t miss a thing. It was the most rewarding race day of my career because of what it meant. We were beat up. We were sad. We were down. There was a clumsy period of what to do. What is appropriate? The uncertainty of running the Breeders' Cup at Belmont? For horse racing fans, it meant a lot that they could return to the track and feel good, feel alive. I believe it was the first international event held in New York after 9-11. For me, I’m not sure there has been a better day of racing than that.”

On October 11, Sheikh Mohammed al Maktoum’s private 747 arrived at JFK International Airport from England. On board, were three of Godolphin Stable’s best horses including Arc de Triomphe, Juddmonte International winner Sakhee and major stakes winner Fantastic Light. They were accompanied by two FBI agents, four customs agents and three carloads of Port Authority police. There were no incidents, and the European horses settled in at Belmont Park.

The day broke sunny. There were shooters on the roofs of many Belmont Park buildings carrying AKA assault rifles. “They were very visible,” Schwartz said. “We had sharpshooters on the roof. I went up to the roof, and the guys were just laying down with rifles. It was scary.”

Nader said, “Seeing the snipers on the roof, I thought, how are people going to handle this? Once the races began to flow, it became one of the greatest events I’ve ever been involved in.”

At the opening ceremonies, dozens of jockeys accompanied by members of the New York State Police and Fire Departments lined up on the turf course, each jockey holding the flag of his country. Following a bagpipe rendition of “Amazing Grace,” Carl Dixon of the New York State Police Department sang the national anthem.

Hopes for an all-positive afternoon disappeared before the first Breeders’ Cup race, the Distaff, when Exogenous, who had won the Beldame and Gazelle Stakes, reared and flipped while leaving the tunnel, slamming her head on the ground. The filly was brought back to Hall of Fame trainer Scotty Schulhofer’s barn but died several days later. Her death was only two years after Schwartz lost his brilliant filly Three Ring when she fell and hit her head in the paddock and died in front of Schwartz and Sheryl before her race.

The climax of the day was the $4 million Breeders’ Cup Classic matching the defending champion, Tiznow, against Sakhee, European star Galileo and Albert the Great. In the final sixteenth of a mile, Sakhee took a narrow lead on the outside of Tiznow, who responded by battling back to win the race by a nose. Announcer Tom Durkin captured the moment beautifully, shouting, “Tiznow wins it for America!”

America had won just by running the Breeders’ Cup as planned. That made NYRA, Schwartz Nader, and the rest of their team, winners, too.

Breeders Cup 2022 – the pick-six scandal

A year later, a day after the 2002 Breeders’ Cup Classic at Arlington Park in Chicago, Nader’s quick actions saved racing from further embarrassment when three fraternity brothers from Drexel University were not paid on their identical six winning $2 Pick Six tickets worth a total of more than $3 million.

Nader hadn’t even attended the Breeders’ Cup that Saturday, but he was at Belmont Park the following morning when he noticed something strange about the Pick Six, which had just six winning tickets from a single place, Catskill (New York) Off-Track Betting. “I asked Jim Gallagher to get the configuration of the tickets,” Nader said. “I looked at it, and I said, `Oh, man, this is a real problem. This is a scam.’ Catskill had made up just one-tenth percent of the Pick Six pool. The tickets were the same ticket six times. And the singles were in the first four races with all the horses in the last two.

“Back then, you didn’t get paid until the weekend ended. I called Arlington Park. I begged them not to pay it. The guy said, `Okay, Bill. I won’t pay them until you tell me.’ Then I called the TRPB (Thoroughbred Racing Protective Bureau).”

The tickets had been altered after the fourth race to list only the winning horse. Subsequently, investigators found that the fixers had tested their scam twice before the Breeders’ Cup. Additionally, they also had been successfully cashing counterfeit tickets of uncashed tickets all over the East Coast. The scam had been exposed before the cheaters got paid.

Racing’s image took a big hit from this, but it would have been much worse if Nader hadn’t acted. “It meant a lot,” Schwartz said. “If it came out after it was paid, it would have been disastrous.”

Backing José Santos

Seven months later, Hall of Fame jockey José Santos, who had won the 2002 Breeders’ Cup Classic on 43–1 Volponi for Hall of Fame trainer Phil Johnson, also won the 2003 Kentucky Derby on Funny Cide. A week later, the Miami Herald broke just about every journalism standard there is, alleging that Santos had used a buzzer to win the race from a single phone interview with Santos, whose English was pretty good but not 100 percent; and a single photo the Herald deemed suspicious. This created national and international headlines that Saturday morning, and Santos learned the bad news that morning at Belmont Park, when he was having breakfast with his son, José Jr., at the backside kitchen.

Schwartz responded immediately for NYRA. He got the “suspicious” photo blown up, and it showed conclusively that what looked like an object in Santos’ hand was just the view of the silks of Jerry Bailey riding Empire Maker behind Funny Cide. Besides that, Santos would have needed three hands to carry his whip, the reins and a buzzer.

“NYRA defended me 100 percent as soon as it came out,” Santos said 20 years later. “They did everything to clear my name.”

A hearing in Kentucky two days later confirmed how ludicrous the allegations had been—mistakes the Herald paid for in Santos’ successful lawsuit against the paper.

Schwatz’s legacy

Schwartz’s biggest contribution at NYRA was lowering takeout—the amount of money taken from people’s bets—which, in turn, increases handle, allowing corresponding increases in purse money. Schwartz’s simple logic, which he had used his whole life at Calvin Klein, Inc., dictated that if products aren’t selling, you lower the price. That couldn’t penetrate many of the blockheads in the racing industry who still have failed to grasp this simple concept. When Schwartz left, the takeout was increased and handle declined.

“He came in with a different lens than anyone before him,” Nader said. “He looked at it as a retail business. How do I grow the business? That was retail sales. In our business, it was betting. I think that’s why he really connected. He came in as an owner, breeder and fan. That was the added dimension he brought. That was something we had never seen before. Suddenly, the business was growing.”

The numbers showed that. When bettors get more money returned in payoffs, they bet more—a simple process called churn.

Through intense lobbying, Schwartz got the legislature to reduce the takeout on win bets from 15 percent to 14—one of the lowest in the nation; from 20 to 17.5 percent on two-horse wagers, and the takeout on non-carryover Pick Sixes from 25 percent to 20 and then to 15. “It took a long time to get the bill passed,” Schwartz said. “It passed 211–0. I personally lobbied in Albany to explain how lowering the takeout was good for everybody. Once I convinced them, they endorsed it. It passed both houses, and Governor Pataki signed it. I had a good rapport with him. He’d come to my house at Saratoga every summer. I got along very well with him.”

The impact of lower takeout was immediate. It began at the 2001 Saratoga meet, and handle rose 4.9 percent to a record of $553 million. Attendance at the 36-day meet broke one million for the first time. At the ensuing Belmont Park Fall Meet, handle rose 28 percent. In its first full year with lower takeout in 2002, handle increased at NYRA by $150 million when compared to 2000—the last full year with higher takeout. Schwartz felt it was just a start.

“My goal is for this to be so successful I can keep lowering it,” Schwartz said in a 2001 article by Michael Kaplan in Cigar Aficionado. “With a 10 percent takeout, the size of our handle will become enormous.”

Such thinking was revolutionary to how business had been done at America’s racetracks. “Business got tough, so racetrack operators all over the country raised their takeouts,” Schwartz said in Kaplan’s article. “You don’t do that. Where I come from, you lower your price when business is bad.”

In 2023, Schwartz was asked why racetracks around the country haven’t lowered takeout: “The people who run racetracks just don’t understand the sport.”

Schwartz certainly does.

Irishman Brendan Walsh Strikes Gold in America

Article by Ken Snyder

The expression “luck of the Irish,” strangely, originated in America from the seemingly uncanny ability of Irish and Irish-American miners to strike it rich in the 19th-century California Gold Rush.

Irish trainer Brendan Walsh from County Cork has also “struck gold” on racetracks throughout America and lots of it. His proteges in 2022 earned $8.3 million after 2021 earnings of $7.5 million. Here’s the real motherlode of surprises about those totals: his previous best year was 2019 when his horses earned a relatively paltry $3.8 million.

The soft-spoken trainer modestly dismisses his personal “gold rush” with a simple and ironic “I got lucky.”

Luck and being Irish had nothing to do with it, of course. The reality with Walsh can be summed up, not in a myth, but in an accepted truth: luck is the residue of hard work.

Walsh’s success began not with a promising two-year-old, a typical route to the stratosphere of trainer earnings, but with a $10,000 claimer. There is maybe some luck there, but keen judgment is the “residue” of hard work. It takes a willingness to closely watch Thoroughbreds— another trainer’s horse or horses. And that’s more than just watching race replays. It’s morning workouts surreptitiously watching a prospective claim, getting good looks at conformation in paddocks and stable areas, poring through past performance for strengths and weaknesses of another trainer with a specific type of horse, knowledge of pedigree, and more, all to find a hidden gem.

Cary Street was the prize jewel for Walsh. “I owned half of him for most of his career. He paid a lot of bills, won a couple of stakes, and he got me noticed. No matter how many decent horses I’ve trained since, I probably owe more to him than I do any other.”

That a horse running in a $10,000 claiming race could achieve what this one accomplished demanded extraordinary foresight. Walsh believed that a different direction was all the horse needed to realize potential. “I thought he was an out-and-out two-turn horse, and he was sitting on a win. We just worked on him and gave him a lot of time.”

Walsh missed the two-turn prognosis by one turn. In 2014, Cary Street won the Las Vegas Marathon Stakes at Santa Anita, a mile-and-three-quarter Grade 2 race by a whopping nine-length margin…going three turns. Roughly three months earlier, Cary Street won the Greenwood Cup Stakes, a Gr. 3 mile-and-a-half affair at Parx Racing in Philadelphia after only one win in allowance company. Not surprisingly, he was a 28-to-1 long shot.

Both races were stellar performances—the Philly race earning a 107 Equibase speed figure and a 108 in the Las Vegas stakes race.

“If Cary Street hadn’t come along, who knows?” said Walsh with a shrug. “People that don’t make it, a lot of the time it’s not for their lack of ability. You just have to get the breaks.”

“Breaks'' don't account for spotting what turned out to be an extraordinary route runner who earned $381,515 in purses. One factor in Walsh’s success has been exposure to racing globally. Starting at the National Stud in Kildangan in his native Ireland, racing has taken him to Dubai, the Orient, and Arlington Park with Godolphin; and to England and Newmarket where he got his first assistant trainer’s job under Mark Wallace. (Godolphin was to figure prominently later in Walsh’s career.)

His training career in America began when he met countryman and conditioner Eddie Kenneally while on vacation in the U.S. Kenneally invited him to come back at any time to work for him. Walsh took him up on the offer and spent more than three years with him.

It was at Palm Meadows in Florida where Walsh decided “my time has come. I started with six horses. I had a bridle and saddle. I got six stalls at the track, and away you go,” he said with a laugh.

Not just experience, but the right experience was the best teacher for Walsh. “He [Kenneally] had all kinds of horses—some very good ones—and he dabbled in claiming horses as well. It was a very good education as opposed to going with someone who has a huge barn. You learn about all aspects of training, which was very important to me.”

Oddly, as a native of horse-mad Ireland, American racing always intrigued him. Two summers with Godolphin galloping horses at Arlington Park planted the seed.

“Adjustment-wise, when I came to train in the U.S., it was a whole different ball game. The dirt. The speed. Especially on the dirt, you have to be more aggressive in your preparation, especially young horses starting out, or else you’re going to get buried.

While Ireland is a nation of only 4.9 million, it is surprisingly the largest producer of Thoroughbreds in Europe and third largest behind the U.S. and Australia globally. Another measure of Ireland’s prominence is in Thoroughbred breeding; six out of the current top ten stallions in Europe are Irish-bred, double that of England, the second in the standings for stallions. Despite the wealth of horses, entry into Irish racing is not without obstacles for someone wanting to train, according to Walsh.

“It was very hard for me to have an opportunity to get going in Ireland. There you gotta have a yard. You have to have the backing, and the prize money is not that great.”

The open door with Kenneally opened his eyes to opportunity in this country. “I thought, maybe this is my chance to have a go myself,” he said.

Walsh, who hung his shingle here in the U.S. in 2012, is a repository of insight on both the differences between Irish and American racing and also how similarities have evolved in training methods between the two countries.

Despite repeated success in global events, particularly in the Breeders’ Cup, Walsh believes his countrymen have gone to school on American methods. “When Wesley Ward went over there initially, his horses were hitting the gate so quick and rolling. They were so well prepared. I think it’s actually changed things in Europe a little bit. I think the Europeans may be starting to be a little bit more aggressive with their horses, especially when they have Ascot in mind.”

In Ireland and elsewhere in Europe, many horses no longer get an automatic four-month turnout as has been customary. “That’s changed in Europe now with so many more all-weather tracks,” he said, noting that people are becoming conditioned to year-round racing. “If a horse is sound and he’s doing well, why stop on him for the winter or whatever?”

Still, Ireland has twenty-six racetracks in a country which, in land area, would fit within Texas’ borders twice. Yet, Irish horses won six of the fourteen 2022 Breeders’ Cup races. (U.S.-breds won seven.)

Despite this year’s success of Irish-breds in the Breeders’ Cup and long-standing success with turf races over the years, Walsh sees a change in American horses. “There’s huge improvement with the standard of turf runners compared to ten or twelve years ago. The standard of turf racing in the United States is a lot higher than what it used to be.”

In addition to Ward, Walsh points to trainer Chad Brown as someone producing fantastic turf horses in the last few years. “Bobby Frankel kind of started it,” he added. Brown, perhaps not surprisingly, was an assistant to Frankel before launching out on his own.

As for Irish horses and the Breeders’ Cup, Walsh said, “It’s not a ‘penalty kick’ anymore to bring a horse from Europe,” referencing a high-percentage soccer goal where a single player faces the goalkeeper. In the past,” he added, “a horse bordering on ‘listed class’ in Europe [just below Gp. 1, 2 or 3 races] would win Gr. 2 or 3 races in the U.S.

“It’s not a ‘gimme’ anymore.”

Ireland produces what it does, in part, due to calcium-rich soil much like Kentucky’s—a temperate climate; but perhaps most important, Ireland is a nation where most of the sports focus is on horse racing.

Walsh recalled in his youth that “everybody in Ireland knew somebody who had a horse.” Today, he said, “It’s a little bit like Australia where everybody watches the Grand National. With Cheltenham, everybody has just gone nuts,” said Walsh of the four-day racing festival in southwestern English that pits Irish horses against English-breds and others from continental Europe. “Everybody is in the betting shops during Cheltenham betting on something or other.”

With a smile and probably unable to resist, Walsh observed, regarding Irish versus English horses, “We’ve been wiping the floor with them for a long time.”

Walsh’s exposure to horses came through his father and trips to Cork Racecourse in their home county, engendering in him “from the start” a desire to be a jockey. However, by the time schooling was over, jockeying no longer interested him. Thoroughbred breeding instead became an interest, and he got a spot in Ireland’s National Stud in County Kildare. However, his size and riding background got him started as an exercise rider. “Kildangan used to break and re-train all of Sheikh Mohammed’s and Godolphin Stables’ yearlings and two-year-olds before going on to trainers.”

Walsh was selected in his first year at Kildangan to go to Dubai with Godolphin to gallop the stable’s two-year-old horses. There he got to know Saeed bin Suroor and Tom Albertrani, bin Suroor’s assistant at the time.

“I was lucky enough when I worked for them to travel all over Europe and run horses. I brought horses to Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan. You can’t put a price on that.

“Since Kildangan, you’re probably talking twenty-five years that Godolphin has had an influence on my career.”

Success with Walsh’s horse Plus Que Parfait in the UAE Derby in 2019 was a career changer attracting the attention of the globally prominent Godolphin stable. “They came along when I came back from Dubai that year.”

Did they ever? Included in the first crop of two-year-olds sent to Walsh was Maxfield, winner of eight out of eleven starts including five Gr. 1 wins and purse earnings topping $2 million. A significant part of ’21 earnings was Maxfield contributing approximately $1.5 million to the bottom line.

As an incredible 2021 has been topped by an even better 2022, a question arises: does he envision getting to the heights of Todd Pletcher, Steve Asmussen, et al. “That would be great. It’s nice to be even thought of as being up to that standard. They’re very good trainers, and they have fantastic horses. A lot of it is the stock and managing it.”

As for managing 200 horses at multiple racetracks around the country like the aforementioned trainers, Walsh is ambivalent. “I don’t know that I would. If you’ve got the team and the owners, you can manage it.” He added: “I’ve got a great team right now.”

Despite the resources to possibly return to Ireland and train there, it is not something that is top of mind. “You do miss certain things.

“The world is a small place. I can get on a plane in Boston and be home in six hours. I come from a family of seven. All of them are in Ireland except one of us--a sister who lives in Jersey [the island in the English Channel and not the state].

“No one else in my family is in racing, but they follow it. They’ve gotten hold of Equibase so they’re keeping up with it pretty good. I go home at least once a year. I don’t stay for too long—five or six days—because I get antsy about what’s going on back here.”

Aside from family, Walsh jokes that other Irish “probably look at me as being an American.”

A win in the Breeders’ Cup—an event followed closely by Ireland’s racing fans (and justifiably so considering 2022 success)—would put him in the spotlight back home, he said.

Santin was a prospect for this year’s event after a win in the 2022 Gr. 1 Arlington Million but was saved for the Clark Handicap after a disappointing finish in his next start in the Coolmore Turf Mile.

Walsh has perhaps become “Americanized” when asked which he would prefer between a win in the Breeders’ Cup or Kentucky Derby. “That’s a hard one to call. When you’re in this country long enough, everybody wants to win the Derby.”

Obviously, the training ability is there with Walsh as well as the trust of racing outfits like Godolphin that can provide him with the best Thoroughbreds.

Luck of the Irish? If there really is such a thing, Walsh won’t need it.

Gary Young

By Ed Golden

For a guy whose livelihood is based on calculations measured in milliseconds, Gary Young never seems to be in a hurry.

But he is a quick study with a quicker opinion, remindful of Woody Allen’s quip: “I took a course in speed reading and read War and Peace in 20 minutes.

“It’s about Russia.”

Gary Young’s life is about racing, and consummately longer than 20 minutes. It started when his parents took him to Arlington Park at the age of six, too young to realize it was chapter one of an engrossing biography.

Half a century later, Young is a respected fixture at the apex of his profession as a private clocker and bloodstock agent, providing information for a fee, winning the odd bet with his own dough, and earning sizeable chunks of change as a buyer or seller of young horses at the sales ring.

Sitting in an open box in the last row of the Club House on any given morning, Young has all the tools of a clocker’s trade at hand: binoculars, stop watch, pens, pencils, notepad, recording devices, the obligatory cell phone, snacks, liquid refreshment and other assorted paraphernalia.

He confirms for posterity the horses’ workouts into his recorder with the verbal rat-a-tat-tat of a polished auctioneer, not missing a beat.

His is a specialized sanctum. It has been thus for four decades now.

Born in Joliet, Ill., Gary grew up in nearby Lockport and got his first glimpse of major racing at Arlington Park in Arlington Heights, about 28 miles and a 30-minute ride from Chicago.

“My dad would take me to the paddock and point out certain things, like horses washing out,” Young said, recalling those halcyon days of yesteryear. “We saw horses like Damascus, Dr. Fager and Buckpasser run there. When I was 12 years old, Secretariat came to Arlington after he won the Triple Crown at Belmont in 1973.

“At that time, there was really big-time racing at Arlington Park. It started sliding later that decade, ironically after (owner) Marge Everett got caught bribing the governor to build a freeway from downtown Chicago to Arlington Park.”

It was there he linked his liaison with the Winick family—Arnold, Neal and Randy—Arnold being the most prominent of the trio in the Windy City area.

“Arnold was a really big trainer in Illinois,” Young said. “We’d see each other and I’d say hi to him. My parents (Cliff and Rachel) were weary of the Illinois winters and always talked about moving to Miami where Winick primarily was based.

“He told me if I ever came there to stop by and I could have a job. About 1978, we moved to Florida where I started at the bottom, walking hots and later grooming horses for Neal, who was trainer of the Winick stable there. Randy was training in California.

“As a groom, I became very aware that I was severely allergic to hay. The inside of my arms would burn like they were on fire if I filled up a hay net. Turned out, the Winicks always had someone who would go up in the grandstand and time horses, watch their horses work, watch other horses work, and make recommendations on ones to purchase or claim.

“Neal decided that because of my allergy, I couldn’t groom horses, so he bought me a stopwatch and sent me to the grandstand to time horses. It was in April of 1979 when I was 18. This past April marked 40 years I’ve been a clocker.”

During that span, Young has received testimonials from the game’s biggest players, among them Jerry Bailey and Todd Pletcher. Noted Bailey: “Gary Young has the unique ability to spot good horses at two-year-old-in-training sales after they come to the track to embark on their careers.

“Having watched him grow in racing from the bottom up, his foundation is rock solid and his eye for talent as good as any in the game.”

Added Pletcher: “Gary found Life at Ten for us. His record at auction speaks for itself. He commands respect in many aspects of the racing world.”

Young readily acknowledges he’s made more money buying and selling horses than betting on them, although his maiden triumph as a gambler remains fresh in his memory.

“The first horse I clocked and bet on that won was trained by Stan Hough, who was the dominant trainer in Florida at that time, along with Winick,” Young said. “It was the first horse that Hough bred, and it was named Lawson Isles. He paid $12 or $14.

“I thought to myself, ‘That’s pretty cool.’ Little did I know that I’d still be doing it 40 years down the road.

“I spent a couple years around Florida clocking, and in the fall of 1980, a horse came to our barn named Spence Bay that Arnold had purchased out of the Arc de Triomphe sale.

“He was the meanest horse you’d ever want to be around but also an unbelievable talent. He won a couple stakes in Florida like a really good horse, but Arnold always would cut back his stock there and around April, he sent some to California, including Spence Bay.

“California was California at that time, and I took the opportunity to come there with Spence Bay in April of 1981 and clock horses.

“I stopped working for the Winicks about 1983, but it was amicable, not bitter by any means. They were kind of downsizing a bit then anyway, and I basically went out on my own. I got my last steady paycheck around 1983, before I started clocking.

“Racing was really good in California at that time, and the Pick Six was very popular and appealing. I’d provide my information to Pick Six players for a percentage of the winnings, and I hit a lot of them in the 80s.”

Times have changed, however. “These days, I definitely make more money buying and selling horses than I do gambling,” Young said. “It’s not the same.”

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (PRINT)

$6.95

SUMMER SALES 2019, ISSUE 53 (DIGITAL)

$3.99

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

PRINT & ONLINE SUBSCRIPTION

From $24.95