BACK ON TRACK - THE LENGTHS RACETRACKS ARE GOING TO IN ORDER TO ENHANCE THE LIVE, IN-PERSON RACETRACK EXPERIENCE

WORDS - JENNIFER KELLYAs racetracks like Oaklawn Park, Del Mar, and others have seen an uptick in their on-track attendance, taking a look at the practices that have brought both new and core fans back for more reveals potential strategies for growing turnout everywhere.

From its height in the 1950s and 1960s-on-track attendance peaked at 42,839,379 in 1969-racing has seen its share of trackside fans shrink. Competition from other sports, available via television and other access points, as well as the growth in alternate forms of gambling like casinos and lotteries, and the advent of off- track betting via simulcasting and advanced deposit wagering services (ADWs) have diverted people and their discretionary income away from the ovals. By 2019, on-track numbers for the sport's big days, like the Kentucky Derby, which averages around 150,000 annually, remained strong, but attendance overall had dropped to 8-10 million. Yet wagering handle has stayed steady, with off-track betting at simulcasting locations and via ADWS bringing in the majority of the sport's income.

However, for racetracks, encouraging fans to attend (and wager) in person is more profitable overall than other sources. "Every dollar bet at the track is way more valuable to the track than anything away from the track. In fact, the further away you get from the track, the less productive it is for the track," said Alan Balch, Executive Director of California Thoroughbred Trainers and former Senior Vice President of Marketing at Santa Anita Park.

"With on-track betting, the wagered dollar does not have to be shared with so many other constituencies. The further you get away from the track, the more people are taking their cut along the way."

Thus, racetracks needed to prioritize attracting fans for a day at the races, but also those who wanted to wager off-track, while also competing with growing options for spending both free time and discretionary income. It was an across-the-board conundrum for all forms of entertainment, not just horse racing. Then 2020 happened.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique challenge for racetracks everywhere: a sport already experiencing a decline in attendance had to adapt to a period where that element of their business was not an option. Would this be temporary, lasting only days or weeks, or would this stretch on for months and potentially have long-term deleterious effects?

With even its core supporters unable to be on track, the emphasis shifted even more to the convenience of wagering at home. While teaching fans, from the casual to the committed, to bet on their phones or their computers sustained them through the uncertainties of the pandemic, that shift also presented another set of challenges when the world was able to welcome fans back to the in-person experience once again: how to bring back the social experience of a day at the races in a post-COVID economy, where previous methods of outreach have given way to new ones as people shift how they prioritize and consume entertainment.

Not only is racing competing with the National Football League, Major League Baseball, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, Major League Soccer, and their offshoots for in-person attendance, but also for media time. Fans can watch most of those sports on broadcast television on a regular basis, especially if professional sports teams are local to them, but their exposure to racing on major networks is limited to the three Triple Crown races and the Breeders' Cup.

Santa Anita

With cable or other paid services, fans can see racing via Fox Sports or Fan Duel. Streaming services increase access even more, but they also require a recurring subscription. Social media can play a role in attracting viewers, but a user's algorithm is going to target their interests, making it more challenging for racetracks to reach newer customers if they have not already indicated interest in racing. For racing to compete, it requires racetracks to buy in to what fans expect to a degree they may not have in previous eras.

"If you're going to try to motivate people to attend something, you have to have all the cylinders in the marketing engine working together. And that requires real investment, money investment, people investment, and experience investment," Balch observed.

"Any place where there's racing is a very competitive environment because there's a lot of entities competing for attention. And you can't compete for attention if you don't invest in it."

For Churchill Downs, which has properties in both major metropolitan areas and more rural settings, the competition for network time requires flexibility in a cutthroat sports media landscape. "Quite honestly, it's difficult to make inroads with some of the major sports franchises from my experience. In America, football is king and we have to figure out ways to work around their scheduling," said Gary Palmisano, Vice President of Racing. "It's up to the track to find ways to fit events around games."

With competition for both fans' attention and dollars evolving, racetracks must stay on top of what works now rather than falling back on past successes. The recent growth at tracks like Oaklawn and Del Mar offers the sport a blueprint for reviving the on-track experience for the sport's core and bringing in new faces everywhere.

Peruse a sports bucket list and you will find the signature big days of any sport: the Super Bowl, World Series, tennis's Grand Slams, The Masters, and the Kentucky Derby. Racing has cultivated an enduring audience for the Run for the Roses, but that singular day is built on the hundreds of race cards in between those big days.

Because the on-track experience yields more money for racetracks, both from wagering and from admission, food and beverage, and more, refocusing on the day at the races experience is a necessity for the sport's long-term health. "I'm a big believer in the live racing experience. ADW and simulcasting are where the super majority of the handle comes from, but if we don't have live racing, how are we going to create the future fans to do simulcast and ADW and come to our big days?" said Damon Thayer, former Kentucky state senator and senior advisor to the Thoroughbred Racing Initiative.

As the sport's most recognizable brand, Churchill Downs emphasizes investment in its properties, whether in metro areas like Louisville or New Orleans or more rural locations like New Kent, Virginia, and Florence, Kentucky, as one way to bring fans back for a day at the races. "We work very hard at all of our properties to improve the overall racing experience for fans and the horsemen," Palmisano shared. "Whether that be from capital projects enhancing the physical plant or strategic initiatives to better the racing product on the track itself. We are constantly innovating and trying to create new experiences whenever we can."

Colonial Downs

To do that, Churchill Downs Incorporated, the parent company behind its various Standardbred and Thoroughbred properties, will add new events to its traditional calendar in order to extend the opportunities to attract new and core fans: "In 2025 we created a brand-new Kentucky Derby prep race in March at Colonial Downs. Colonial's racing season is traditionally in July and August, so we had to create an experience from scratch. Over 8,000 people attended and we're nearly sold out again in 2026.

That's just one example of our efforts to think outside the box and push ourselves to improve." On top of looking for opportunities to add new must-see events, cultivating the experience of a weekday at the races is about "selling the sport of horse racing. It's not to gouge them with an expensive soda or hot dog," said Louis Cella, President of Oaklawn Racing and Casino, "It's the experiential part of the sport, which is so great. And if you can get them with that, they'll go all day long."

In areas like Los Angeles, where the options for entertainment include multiple sports teams, museums, the film and television industry, and more, Santa Anita Park works to hold its own with both its core fans and those new to the sport. "One way we do this is by cultivating and rewarding our core, by rewarding them with gifts, or free play, or special offers for free admission," said Andrew Arthur, the track's Senior Director of Marketing. "Our other attraction strategy is to bring new fans into racing, which I'm sure is something that you're more interested in. And how we do that is we add extra experiences."

The classic racetrack incorporates a wide- ranging calendar of events, including corgi races, special food and beverage vendors, and on-track attractions like its annual calendar giveaway on opening day, traditionally the day after Christmas. Additionally, they have wagering ambassadors who interact with newer fans one-on-one, taking them on tours of the track and teaching them about how racing and wagering work.

"We focus our marketing around our big days and then have a steady flow of marketing to promote those other smaller events that I talked about. And then our on-track experience, the wager investors, try to convert them into longer fans." Arthur added. "Once we get those customers, then we start getting them into our email funnels and our texting funnels and doing our best to make an offer to them to come back."

Located in San Diego, the Pacific Ocean a hop and a skip away, Del Mar faces similar challenges and yet has seen a similar increase in on-track attendance. "There's so much to do. We have a ton of competition in the area, especially during the summer," said Erin Bailey, the track's Vice President of Marketing. "You've got the beaches, the Padres, and more. So we firmly believe that we have to have a reason for people to choose us over all those other things."

Del Mar Racetrack

To do that, Del Mar emphasizes affordability and familiarity. "You can get in for $8, and you can bring a picnic, and you don't even have to buy our food and beverage," Bailey said. "You can bring in your own food, and you can just post up trackside on the apron or wherever you might want to land. If you want to have a very financially efficient day, you absolutely can."

Additionally, "we [at Del Mar] really work hard to find these familiar things to bring people to. So on Saturdays, for example, we will have a lifestyle event like a food or wine festival or a trackside bourbon tasting while also watching world-class racing. We use a lot of those types of experiences to bring people out, to get them with something that they already are doing and are used to."

While Oaklawn Park may not face the same competition for fans, its location inside a national park an hour outside of Little Rock, Arkansas, may not seem like a natural racing destination, but the Cella family's emphasis on customer service has helped make this century-old racetrack a destination for fans from all over the region. "There is a reason we average over 10,000 people a day, over a 65- day meet. And that is because we appreciate and we do everything in our power to help the fan," said Cella, who is the fourth generation of his family to helm Oaklawn. "The reason that's so important is you sell them the product of horse racing, and that's our business, selling the sport of horse racing, not gambling."

"And when we're successful at that, guess what? They're going to come back, they're going to place two bucks to show on the favorite, they're going to buy a hot dog, and all the other areas will start being successful."

Oaklawn does that through incentives like free admission, inexpensive programs, and on-track wagering benefits like their Show Bet Bonus, which rewards fans who place wagers at Oaklawn rather than through an ADW or off- track betting service. Like Santa Anita, the track also has ambassadors that wander through each day's crowd, offering answers to any questions fans may have and engaging with the public directly, reinforcing the track's emphasis on customer service. Additionally, Oaklawn's approach to concessions underscores its commitment to making the on-track experience an affordable one.

"Fans will never have to buy a $12 beer at Oaklawn. We are proud that it is affordable for families to bring the kids. We own our food and beverage vendors across the entire plant. And because we own it, we do not view food and beverage as a profit center. We view it as breaking even," Cella said. "If we break even, we can pass those savings on to our fans. So they come over and over and over because they know they're not going to be nickel and dimed at the concession stand. It's a very different view of a racetrack, especially on track."

That affordability is key to bringing fans back for the on-track experience as Nick Tammaro, Sam Houston’s Player Development Manager and track announcer, emphasizes: “One thing that I think we’re trying to capitalize on, that we could do better, everybody could do better, is that the entertainment dollar right now in this country is spread so thin because everything is so expensive. If we’re able to get people to understand that you could come out and bring your family of four and watch live racing and get a decent seat to do so and feed them for 60 bucks, in an area like Houston, that’s a good deal.”

Compare that cost to other major sports and racing’s advantage as an affordable sporting and social experience stands out. For the same family of four to attend an NFL game, including tickets, parking, and concessions, can cost from $600 to over $2,000. An MLB game could run $150-$300, while an NBA game might cost upwards of $1,000, and an NHL game hovers around $400-$500 on average. Those prices make a day at the races a much more affordable option, but as Balch points out, tracks have to invest in the marketing necessary to share that advantage.

“My opinion, number one, is that the most important thing is for track management and ownership to view marketing as an investment and not an expense. That is the critical component of getting people to come to the track,” he said.

Alongside marketing must come hospitality, including food, beverage, and facilities, the tangibles that help people create the social experience of a day at the races.

“The thing is, the consumer who spends discretionary money on sports and entertainment, they expect a certain level of hospitality when it comes to food and drink and seats and the overall experience,” Thayer observed. “That’s something racetracks are going to have to be cognizant of moving forward, especially if you’re trying to get 20-somethings and 30-somethings to come to the races. Those kinds of fans have high expectations.”

“The biggest salespeople for any entity, including a racetrack, are satisfied customers,”

Balch echoed. “People who go home from a day at the races and tell their neighbors, ‘We just went to the races today. We had a great time out there. God, it’s the most beautiful place. Oh, you’ve never been? Oh, really? Yeah. Let’s go together. I mean, that’s when you get your existing customers to be your sales force.’”

With that in mind, what can racetracks do in the 21st century to bring both new and core fans back for a day at the races?

“I fully subscribe to the idea that if you give people something known, something comfortable, something that they’re used to, and if you put that experience trackside, they want to stay. They want to experience what you have to offer in a day at the races,” Del Mar’s

Bailey said. Bring what fans enjoy about their social experiences—good food, comfortable settings, the sports and entertainment they seek out—and then put all of that within the setting of a racetrack, and a day at the races becomes a viable part of a fan’s sporting life. How a particular location can do that will depend on how much their operators are willing to invest in their individual communities. Though racing may be as simple as several horses competing over dirt or grass, a universal pursuit that transcends location and language, getting fans in the door means understanding what works locally and that takes investment.

“I firmly believe that you can’t create a new fan without them experiencing the actual life at the racetrack,” Tammaro said. “I will die on the hill that I’ve never taken anybody to the racetrack, and they haven’t had a good time.”

“Racetracks are fan incubator sites, and not only is it important to attract fans for today and that they have a good time, but also to create the fans of tomorrow,” Thayer observed.

“We’re also developing profits for the track operator and building purse money for the horsemen,” both important parts of keeping the sport going.

“We have to admit that most people are not walking out of there having won a bundle of money. But if they’ve had fun, that’s the thing. That’s what we’re selling. We’re selling fun, we’re selling entertainment, we’re selling a social experience that people at all different levels have,” Balch said. “And that’s, again, that’s another great aspect of the racetrack. Going to the races is fun.”

To do that means putting fans, both potential and existing, first. “If you build it, [they] will come,” the voice says in the movie Field of Dreams, and indeed the main character’s efforts are rewarded with a transformative experience, one that endures long past the film’s end. It is a lesson that racing can embrace not simply in the short term, but for years to come, no matter how much the cultural landscape changes: build a familiar and welcoming space, one where people want to congregate, with the elements that make them feel at home, and they will come back again and again.

How each racetrack will achieve that is a conversation the sport must continue to have with not only fans, but also with each other. The question is, how much is the industry willing to do to make that happen?

CULTURE CONFLICT? - The Alan Balch Column

WORDS - ALAN BALCHWe've all been hearing about "culture" for the last ten years or more - "culture wars" politically, for example. But I pricked up my ears when I heard the leaders of the California Horse Racing Board refer to changing the "backstretch culture" at their last meeting.

To begin with, that word originated around "cultivation," in the agricultural sense. Growing and nurturing. Over the centuries, obviously, it took on many nuances. I remember when "cultured" people were those who appreciated fine art or attended the philharmonic orchestra, or had advanced, sophisticated education. They had been or were "cultivated," I suppose, with some worthwhile objectives in mind, I venture to guess. Aristocratic? And then there are cults, but let's not go there. Please. Even though all those related words come from the same origins. My own professional lifespan in racing management and observation is now over half a century. Plenty of time to develop opinions, many fervently held before changing, or evolving, or changing back again. Age supposedly brings wisdom. Artificial Intelligence claims Ernest Hemingway "famously" observed, "The wisdom of old men. They do not grow wise. They grow careful." So famously that I couldn't find where he said it. But it seems true to me. In what follows, however, this old man is throwing that out the window.

Our California regulator was taking up the issue, for the zillionth time, of racetrack safety, and the ways and means of protecting our horses. That's as it should be, because nothing is more important. If only laws and rules and regulations could do the whole job! Nobody doubts that they can help... but many doubt their overall efficacy. Why else do we keep returning endlessly to their additions and refinements?

It was in this context that we were publicly advised that the training and veterinary culture on the backstretch must continue to change: from treatment to a preference for diagnostics before treatment. Personally, I thought it had always been that way. So, what that really means, I think, is that diagnostic methods have improved magnificently (and expensively) from what they once were, and must all be employed. Before treatment. Any treatment?

I was taught, beginning about 70 years back, that no individual mammal (including horses and humans) is 100% healthy. Mother Nature just doesn't make them that way. And they're all at risk of injury. Or worse. Thus, preventive care is born. And so is animal husbandry. Along with veterinary medicine. Checking the feed tub and temperature, and jogging a horse for soundness, start the diagnosis. But in racing, and other equestrian sport, sadly, even a relatively sound horse might perform better if he just feels better! And so were born the infinite variety of lotions and potions, pills and injections. Human health "enhancement" mirrors the equine evolution, does it not? And almost certainly preceded the use of all kinds of "enhancing" in the equine world. After all, we humans are responsible for what we receive or ingest. Our horses are not. They rely on our integrity. That awareness and commitment, I believe, is what has been changing, and what must backstretch and training and veterinary culture.

The fundamental culture of American breeding must change, too. That's even more important, because that's where horsemanship begins. And it will be enormously difficult, probably far more difficult than changing the behavior of a relative few in the backstretch community who have brought ill repute to their peers. Breeding more sound, substantial racehorses, it seems to me, rather than breeding for ever more expensive breeding stock, as the circular end in itself, must somehow be incentivized. That's exceptionally difficult in our increasingly libertarian capitalistic America. The short-term goals of astronomically high prices in the auction ring and for syndicating retiring three-year-olds is, to put it politely, inconsistent with developing both greater substance in our racehorses and drawing greater public interest in our most important races. Racing success was heretofore supposed to be the proof of breeding.

In the 1970s, the late Frank E. "Jimmy" Kilroe, a Pillar of the Turf, widely admired throughout racing, was telling everyone who would listen what was coming. What we have now. And reminding us all of the importance of box office, which relied on racing's great equine stars, so many of which he knew firsthand, and which by and large were geldings! According to The Blood-Horse, these were the top: Kelso, Forego, John Henry, Armed, Roman Brother, Fort Marcy, Best Pal, Native Diver, Lava Man, and Ancient Title. Six of the ten were largely responsible for massive crowds attending the Santa Anita Handicap, beginning with Armed in 1947.

I got to thinking about all this again when thrilling to the Breeders' Cup Turf just run at Del Mar (pictured). Amazing, exciting race and look at the result. A parade of great international geldings: Ethical Diamond, Rebel's Romance, El Cordobes, Amiloc, Californian Gold Phoenix, the filly Minnie Hauk, Redistricting, before we got to the first entire horse, Rebel Red. All Irish or British-bred. In fact, only two of the fourteen starters were bred in the USA. Yes, let's change the culture ... and breed for racing. Not breeding.

Alan Balch - Turning Point

Article by Alan Balch

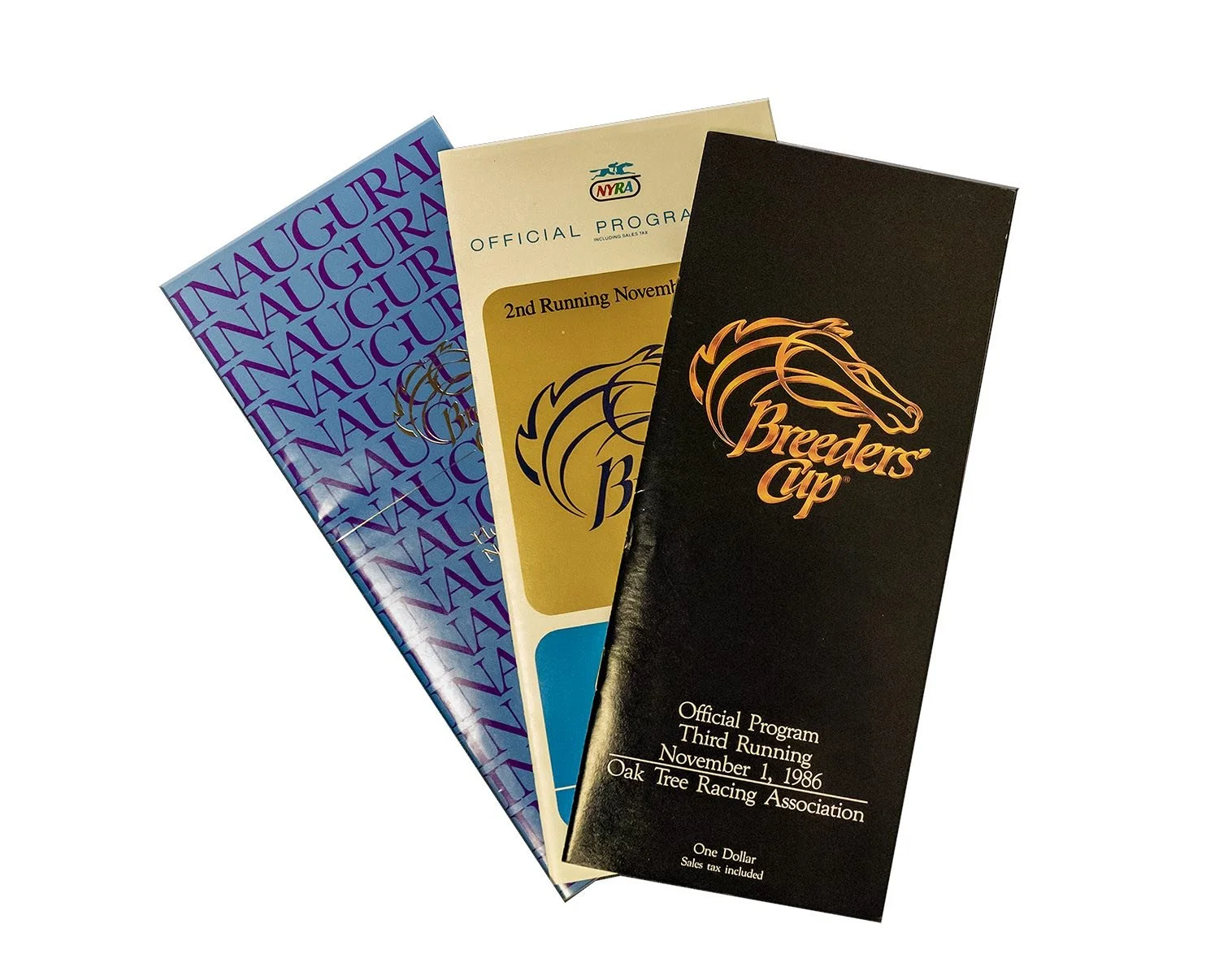

November 1, 1986, is the date the Breeders’ Cup was assured of a viable future. The first one at Santa Anita. This year at Del Mar will be the 42nd edition.

Its founding visionary, John R. Gaines, had repeatedly emphasized the importance and potential of the Breeders’ Cup for marketing racing: to stimulate its massively increased sporting awareness through the televised spectacle of our championships.

Yet, mysteriously, its early leaders had chosen two of the least telegenic tracks in America for the first editions: Hollywood Park and Aqueduct.

I’m one of the few still left in racing (or even alive) who was in the midst of that mystery at the time. In fact, it was my responsibility at Oak Tree Racing Association and Santa Anita to prepare and lead the presentations of our proposals for the site selectors, prior to 1984, and again for 1986.

That committee (which included several Thoroughbred paragons including Nelson Bunker Hunt and John Nerud) had locations across the entire nation to consider. But California tracks in those days were perennial leaders in attendance and handle and – most important – reliably nice November weather. Most everyone thought the inaugural choice came down to the southland rivals, Hollywood Park and Santa Anita.

So, in 1982 and early 1983, Oak Tree emphasized both our statistical superiority and Santa Anita’s pending hosting of the 1984 Olympic Games Equestrian Sport: the potential worldwide double of exceptional excellence for that year which would be provided for its launch. And I vividly remember Oak Tree President Clement Hirsch proclaiming to the selectors, “it has never rained on that weekend at Santa Anita,” which was true, but tempted fate. It did rain that weekend, in 1983, the year before the first one. (It has at least once since then, too.)

Hollywood Park emphasized . . . well, Hollywood . . . with Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant, and their fellow stars, along with the 20th Century movie lot. Plus, a pile of cash in earnest to assist the fledgling effort. It was chosen for the premier.

Naturally, we the losers were chagrined. Even angry. Oak Tree’s brass at the time privately suggested “never again.” Personally, and not for the last time, through the cloudy experience of bitter disappointment, I dimly saw some advantages of not being “first” at such an undertaking. Those few of us still around who witnessed that day at Hollywood Park will remember what I mean, particularly in terms of “operational challenges,” to put it much more politely than deserved.

Ultimately, and with far more reluctance than anyone would now admit, Oak Tree’s leadership decided to try again in 1985, to receive “the honor” of hosting in 1986. Breeders’ Cup administration in those days was nothing like the independent behemoth it has grown to become. Then, it relied very heavily on existing host track management, the track’s own marketing, operations, and racing expertise. It had no choice but so to do. But with that reliance came plenty of tension, most of it healthy, as the host track not only wanted to protect its own prerogatives, but also the interests of local fans, owners, and trainers. Breeders’ Cup, quite rightly, insisted on proper accommodations and recognition of all those who put up the multi-million-dollar purses – the breeders and their constituencies.

As part of our effort to win that year, Oak Tree sent me to meet with Mr. Hunt at his Texas spread, the famous Circle T, not far from DFW airport. That was an early morning I’ll never forget. “Bunker” arrived by himself to pick me up at the airport curb, driving his (old) Cadillac. “Son, I hope you’re not hungry, because we’re going to the farm first to see my horses.” He wasn’t exactly lithe, you know, but he gave me my own workout that day: we walked back and forth with each set, he describing their individual quirks and pedigrees in detail, watching them gallop or work. It was all in his head, without pause: he loved the game, he loved those horses, and knew both deeply. I was a “suit” in those days, but I saw the essence of racing in a new way. At the elbow of one of its greatest advocates. I learned way, way more than I had ever expected.

Then, onto the local greasy spoon for grits and whatever, with Bunker and his local mates yucking it up . . . that was the atmosphere for my pitch.

I can’t remember now if we had any real competition . . . we were coming off not just a highly successful Olympic Games effort, but also our Fiftieth Anniversary season where we drew our single-day record crowd of over 85,000, averaging nearly 33,000 per racing day.

If you look back now at the videos of the races that first Santa Anita Breeders’ Cup Day [https://breederscup.com/results/1986?tab=results], you can see what those truly mammoth crowds looked like. Official attendance was just under 70,000, easily a new record, as was the handle. Unlike today, however, official crowd numbers significantly understated attendance . . . since only those passing through a turnstile were counted, leaving out large numbers of backstretch personnel, as well as all the kids. The television spectacle that only Santa Anita can offer was in full, crystal-clear view.

The financial future of Breeders’ Cup was finally assured.

The Alan Balch Column - Artists of the air

There are ever fewer of us around who can clearly remember the world before the advent of television. And the Internet.

But as I thought about the retirement of Trevor Denman, and all his illustrious contributions to American racing, nostalgia overtook me. As it does quite often these troubling days.

Those of us who have been around for eight decades or more remember when sports were largely heard, not seen. If you couldn’t get yourself to a ballpark, or college football stadium, or race track (there really weren’t that many of them, considering the size of the United States, or any country) in the 1940s, or earlier, you followed sports on the radio.

Baseball games were often, even mostly, recreated, with appropriate sound effects. Believe it or not. I was just a kid when I realized that the pop of the ball into the glove was phony, because it was the same for each pitch. Same thing for the sound of a batted ball! The crowd effects were ridiculously similar from inning to inning and park to park. The telegraph wires provided the “facts,” and the announcers re-created the action. Someone named Ronald Reagan began his career doing that kind of sports announcing.

Then there were the movie theater newsreels, which almost always had the leading sports. You could “thrill” to Clem McCarthy calling a race, whether it was the first Santa Anita Handicap in giant clouds of dust, or Seabiscuit beating War Admiral at Pimlico, and actually see them. After having heard them on the radio when the races were run.

So, the radio was how racing first came into my life. And into millions of other lives. Joe Hernandez was the original Voice of Santa Anita. He called its first 15,587 consecutive races, never missing one at the winter meeting, from Christmas Day 1934 until he fainted at the microphone in January 1972, and died several days later from the effects of being kicked on the backstretch at Hollywood Park during morning training. That iron-man streak was one of the most remarkable achievements in sport, in its own way, ranking up there with Lou Gehrig’s.

Countless of us, particularly throughout California, only knew racing through Joe’s lilting, accented radio calls, all beginning with his booming, “There they go!” -- whether from Santa Anita or Del Mar or tracks in the north. “From the foot of the majestic San Gabriel mountains, this is your announcer Joe Hernandez at spectacular Santa Anita,” he would intone, and your imagination took over. Just like it did in other sports on radio, when the artist was . . . well, an artist!

Hearing him from childhood, live and also re-creating the day’s races, hawking “Turf Craft winners” for a sponsor, I couldn’t believe my good fortune meeting him when I was first employed at Santa Anita. We immediately started using his artistry in commercials, and he gifted me with all his old recordings, which he had meticulously kept since 1934. I pestered him constantly, and he was an unsurpassed raconteur. He unhesitatingly told me the greatest race he called was the Noor (117 pounds, Longden) and Citation (130, Brooks) battle in the 1950 San Juan Capistrano. They hooked each other for almost the entire mile and three-quarters on the main track. Noor won by a nose. Let your own imagination take over: “the two raced head and head for five-sixteenths, the lead see-sawing back and forth, in the most protracted drive,” said Evan Shipman in the American Racing Manual. “They were to continue locked right down to the wire, where, with the luck of the nod, the camera caught Noor’s nose in front.” Broken down by quarters, the race reads: 24, 23.4, 24.3, 25.3, 24.3, 24.3, 25.3! Citation led at the mile and a half mark, two-fifths faster than the American record at the time; the two set a new track record by almost six full seconds, and a new American record.

His 1940 call of Seabiscuit becoming “a new world’s champion” in the Santa Anita Handicap still rings in my ears, from the souvenir we produced, “70,000 fans going absolutely crazy, including your announcer, and he broke the track record, it’s up there.”

Is it any wonder that a bust of Hernandez graces the Paddock Gardens at Santa Anita? Perhaps the only such recognition for a race caller in the world?

As Joe’s most luminous and artistic successor, Trevor has long-since joined the pantheon of the world’s great artists of the air waves, but in an entirely different era. With the advent of racing being televised lived, he couldn’t have gotten away with any of Joe’s famous antics: he once sat down after calling the horses through the stretch to the wire off the hillside grass course, when they still had another mile to run. Waking up to what had happened as the horses turned into the backstretch, with his customary aplomb he simply blew into the mike and tapped it twice, then proclaimed, “TESTING, TESTING,” and continued as though there had been a power outage.

Having once yearned to be a jockey, Trevor’s viewpoint has always been unique. He asked permission to walk the courses at Santa Anita his first day. Asked why, he said to me, “I have to see everything from the riders’ perspectives.” He was the first American caller seamlessly to integrate the riders’ names and styles in his pictures, as he painted the race. He also seemed to know instinctively just how much horse each jock had at all times. If you listened carefully to his tenor, many were the times when you knew who the winner would be at the half-mile post.

Still, all the tributes to him can be summed up very simply: he has been, in short, “UN-BE-LIEVE-ABLE.”

What would you do to make California racing great again? We canvas a cross section of opinions from those involved in racing and breeding in the Golden State

Words - John Cherwa

There is no doubt that horse racing in California is at a crossroads.

The closure of Golden Gate Fields in June signaled the possible end of full-time racing in the Northern part of the state. There is a long-shot plan to keep it alive at Pleasanton, but not everyone in the business is routing for success.

In the South, Santa Anita is still only racing three days a week and field sizes are not always impressive. Purses are not competitive with the rest of the country. The track sits on a piece of land in Arcadia that is worth at least $1 billion, so does it really make sense to run a few days a week for half the year?

So, what are the views of those deeply involved in California racing on a day-to-day basis as a way forward?

What follows is a question and answer session with prominent executives, trainers, owners and breeders. There are disagreements and obvious animosity. Although everyone interviewed has the same goal, keep racing in California alive. The solution to problems facing the most populous state in the country, might just be in here.

The answers to the questions we posed have been edited for clarity, brevity and to avoid too much repetition.

Can a one-circuit system (in the South) work?

Aidan Butler, chief executive 1ST/ Racing and Gaming: Absolutely. California is a huge betting state and it’s not just the horse population or purse disparities that separate us from other states that get additional revenue. There is a huge cost of running an operation that is an obstacle. So, putting all of the resources and effort into one area is the only way to go.

Alan Balch, executive director California Thoroughbred Trainers: It's highly doubtful, given that California is now more an "island" than at any time in at least 50 years. There's very little chance of alternate circuits (Arizona, Washington) serving as viable or sustainable racing destinations for California breeders. Successful Northern California racing was an integral and vital, if unsung, component of world-class California racing from the 1960s onward.

Bing Bush, equine attorney and owner: That’s to be determined but it’s difficult to envision that. I happened to be at Golden Gate Fields on the last day, I saw a lot of horsemen walking around in a very full grandstand, all thinking the same thing: “I wish all of these people were here during our days and then we wouldn’t be closing down.” I don’t see how Santa Anita hopes to fill that gap. It’s going to be a real challenge I hope we can meet. I’m hopeful but very concerned.

Phil D’Amato, a leading trainer at Santa Anita: I definitely think so. For me, we have the horses, we have the population. I just think we need to improve our purse infrastructure. When you get more money, people will come and owners will be more willing to put horses in the California racing system.

Greg Ferraro, chairman California Horse Racing Board: Yes, I think it can. The problem is we don’t have enough horses, plain and simple. We’ll see how they do in Northern California with the dates we awarded them. I’m hopeful for them but I’m not optimistic. I’m worried that we don’t have enough horses for two circuits. Consolidating everything in Southern California may be the only way we can survive.

Eoin Harty, trainer and president of California Thoroughbred Trainers: If certain powers have their way, we’re going to find out. Personally, I don’t think so. The whole business hinges on breeding. The largest part of the horse population in California is Cal-breds and they don’t all belong in Southern California. If they don’t have a venue to run at, what’s the point in breeding them? And if you don’t start breeding them, where does the horse population come from? The economic impact on the state is huge. If we lose that, the fall is catastrophic.

Justin Oldfield, owner/breeder and chairperson of the California Thoroughbred Breeders Assn.: I think there was a misinterpretation of what a one-circuit system means. A one-circuit system is not defined by fulltime racing in the South and summer fair racing in the North. That is not the definition of a one-circuit system. I think what people mean is a one-circuit system that includes Los Al, Santa Anita and Del Mar and does not include the fairs. The fairs garner a lot more representation from the Legislature and the fan base across the North. I don’t think there is anyone who is saying we should end racing at the Fairs. I think no one would be in favor of a one-circuit system if it means only racing at one track at any one time.

Bill Nader, president and chief executive of Thoroughbred Owners of California: A one circuit system in California would allow the resources that are generated across the whole state be targeted into one single circuit which would effectively make better use of that money and funding. The problem with a two-circuit state like we have now is that if one circuit isn’t carrying its weight, like it is now, it takes its toll on the other region.

Doug O’Neill, a mainstay trainer in California and two-time Kentucky Derby winning trainer: No. The track surface needs a breather throughout the year. I think with training and racing it needs some maintenance to bounce back. I think it’s really important to have some time between meets and that’s where it helps to be racing at a different circuit or track.

Josh Rubinstein, president and chief operating officer at Del Mar: Yes. Nationally the foal crop is about half of what it was 30 years ago so that has affected every state. California simply doesn’t have the horse population to operate two year-round circuits.

Is contraction the best way to stabilize the market?

Butler: We believe contraction is the best way to stabilize the market. There is only a certain amount of purse money and a certain amount of population. Despite the hardship of the people at Golden Gate, concentrating all our efforts in the South is the only way to keep the state going.

Balch: The unplanned and devastating contraction announced by Santa Anita ownership, without consultation or notice to any of its interdependent partners in California racing, is the single most destabilizing event in California racing history since World War II. Given the contraction of the North American foal crop, particularly since 2008, all track owners and horsemen working together with the regulator and Legislature might have been able to develop a model where it could have been a stabilizing influence.

Bush: I think it will turn it into chaos unless we can turn it into something more attractive than it is today. If we can’t make California racing more attractive, I don’t see how contracting can help it.

D’Amato: As it stands now, it’s looking to be inevitable unless we find another revenue source. You would like to have two circuits. It definitely gives owners more options for varying caliber of horses. But if it has to be, it has to be. We need just one additional revenue source to help get these purses up and allow California to sustain. If we don’t get that, consolidating into one racing circuit is probably the only option that we would still have.

Ferraro: The best way to stabilize the market here is to increase the purses. That’s our problem and the reason we are short of horses is because we can’t compete purse-wise. We don’t have any way of supplementing purses like Kentucky does with Historical Horse Racing. If we had purses that were more competitive with the rest of the country, most of our horse shortage problems would go away.

Harty: I don’t believe so. I believe expansion is the way to save the market. You’ve seen what happened through contraction, small field sizes, people aren’t betting on us, which hurts our handle which just compounds the problem. We need to expand and plan to expand. Hopefully it’s not too late, but without some sort of addition to our purse fund where we can make it more lucrative for people to come to California, we’ve got nothing.

Oldfield: No. Contraction assumes there is a consolidation of not only the tracks but a consolidation of the horsemen and trainers and the employees. The assumption that trainers and owners would go South was probably false and unwisely made. Look at the trainers who have moved South, it hasn’t been a resounding success. To assume that if you close the North that it means a shift to the South is a pretty naive thing to consider.

Nader: It might be the only way to stabilize the market. Now if the North is able to hit its targets and meet the criteria we’ve agreed to then there is no need for contraction. If the North can’t hit their targets, I don’t think we’ll have any recourse but to contract to stabilize the market and secure Southern California and make sure the state of California is still relevant, healthy and has a future.

O’Neill: For us to grow, we need to build on what we have and not shrink what we had. I think the whole industry has done a really good job of being a safer, more transparent sport. And to see tracks closing is not what the whole plan was, or at least I hope it wasn’t. I think the way the sport is going, we should be growing and building and not closing and shrinking.

How do you compete with no supplemental revenue streams?

Butler: You just have to try and be innovative, offer a product that people still want to bet, and continue to try and concentrate on a single circuit and there should be enough wagering dollars in state to keep the product moving forward.

Balch: Clearly, you don't, unless you develop alternate sources of supplementing purses, for example major corporate sponsorship, or otherwise. You need sources that could only be developed by all track owners and horsemen working together with regulators and legislators in serious strategic planning. Fifty percent of track revenues formerly came from non-wagering sources at the track. The nearly complete abandonment of marketing efforts for on-track business has cost all tracks in terms of profit and compromised California racing's future.

Harty: We can’t. I don’t see how it’s sustainable. It’s hard enough to attract horses to California in the first place. The level of racing is very competitive. There is a lot more bang for your buck somewhere else.

Nader: We need to find ancillary revenue so we are more competitive with other states that enjoy that advantage. That’s where California needs to be applauded for what it has achieved over the past 10 years without the benefit of a secondary income stream and still remains relevant on a national stage.

Oldfield: I couldn’t agree more that we need other revenue streams for the funding of purses. For horse racing to survive long term, both in the North and the South, we need outside sources of income, whether that’s Historical Horse Racing machines or some other mechanism. If the North were to go, it slows the bleeding but doesn’t stop it. I think the North is in a better position to survive without outside sources of income because of what it costs to raise a horse and race a horse in the North because we’re really not that far off the purse structure we have for the fair meets. Those machines are the lifeblood, not just to purses, but to keep racing in California alive.

O’Neill: It’s a little tricky with the Stronach business model because they own the ADW and the race track. In an ideal world there would be separation there and you would have the people or company that owns the race track try and do everything they can to get people to come out and have a great time, Concessions would be booming and ideally you would build on getting some on-track betting.

Rubinstein: We have to close the purse gap that is widening from states that have subsidies that are supporting the purses. That is the one thing we can do here, increase purses, that would give California a shot in the arm.

What one thing can be done that would make a difference?

Butler: Obviously, getting another source of gaming revenue would make a huge difference in the state. For quite a while we were competitive from a purse perspective, but it’s become more and more difficult to find another source of gaming revenue.

Balch: Immediately convene the leadership of all tracks, labor, agriculture, owners, and trainers’ groups, for no-holds-barred strategic planning, to include ways and means of communicating with California's legislative leadership, to understand and save the massive economic impact on this industry in California. It almost certainly cannot be saved without government assistance and stimulus.

D’Amato: We’ve got the weather and great training facilities. Santa Anita just added a synthetic training track to handle all weather situations. Del Mar is perennially a great racing circuit. So, to me, we just need bigger purses. We’re pretty much the model for what HISA based its safety structure on. California to me is on the forefront of all those things with the exception of bigger purses. If we get money, people will come.

Ferraro: If we can come up with something like Historical Horse Racing our worries would not be over but would be decreased.

Oldfield: I don’t think there is a single person I’ve talked to, North or South, who doesn’t agree those machines are absolutely necessary. I think that should be a rallying cry from every stakeholder in the North to every stakeholder in the South, from the horsemen to the trainers, we need to get behind. Why aren't we rallying around this instead of sitting in CHRB (California Horse Racing Board) meetings arguing about dates? Why are we not working collectively on a strategy to get these machines? If there is one thing this industry needs right now is unity and the industry needs to unify behind that.

O’Neill: We need to rebrand to really celebrate the men and women who work alongside horses for a living. It’s just so important to get that mindset back that people are actually working and it’s not computers and gadgets that are doing all the work and that humans are actually getting their hands dirty. These are really a bunch of amazing men and women who have chosen to work alongside horses for a living and hopefully we never lose the hands-on approach that is so important. Our sport provides a lot of jobs and housing for thousands of people and that’s really important.

What is California racing doing better than anyone else?

Butler: If you look at the safety record for one and the operational performance without supplemental revenue we can be pretty proud of ourselves to where we are now. California has shown it can operate on a globally high level of safety and quality without having lots of cash coming in to help things. We should be pretty proud of that.

Balch: Very little if anything beyond what it's not responsible for: enormous potential markets, great weather year-around, and unrivaled facilities, mainly Del Mar, given the deterioration of Santa Anita and the demise of Golden Gate.

D’Amato: I think in terms of how Santa Anita and Del Mar take care of their owners, I think they go above and beyond in our racing jurisdiction. I think it’s a little bit tougher in other states. For what we have to offer, we try to roll out the red carpet for our owners and offer a really nice place to run your horses.

Ferraro: The quality of the racing surface and our effort for safety and soundness. HISA basically copied our rules. So our health and safety rules are better than anyone.

Harty: I think we have better venues than anyone else. There is not a prettier race track than Santa Anita. Del Mar offers the summer vacation package.

Oldfield: The one thing I can say about California racing is we’ve got a great fan base. California as a whole is an agricultural state, the largest in the country. The economic driver of the equine industry in California is largely horse racing. People tend to forget about the agricultural component to that, it’s huge. We would be dead without our Cal-breds, which also produces jobs and livelihoods for many people and in many cases provides an economy for smaller communities in California.

O’Neill: We are so blessed we can train day in and day out throughout the year and I think you have a lot fitter horse that comes from California than a lot of the country. That’s the one thing that no company or no family can screw up. We have the best weather in the world.

Is this too far down the road to fix?

Butler: We don’t think so. If we can find additional sources of revenue that’s going to really, really help. You get the purses, you have a far better chance of getting the horses. There is much more to the ecosystem when you’ve got the purses. We, as a company, want to make it as good as we can for trainers. We think of them as our customers and we want them to be successful. We’ve just got to try.

Balch: If you say you can't, you're already done. If you say you'll try, you've at least begun. No one person or one entity can do anything of true impact alone. It takes the entire interdependent industry together.

Ferraro: I hope not. I think the next year will tell. We’ll see how Northern California does. If they succeed that will be a positive thing. If not, then we will have some worries. If Santa Anita and Del Mar can keep a decent racing program going that would help. If we end up with six-horse fields and two days or racing instead of three, that’s going to be a terrible turn.

Oldfield: Absolutely not. You go to the fairs and they are packed. There is an appetite for horse racing in California. We’ve just got to do a better job of figuring out how to market that. You can’t determine whether what happened at Golden Gate over the last couple of years or 10 years is indicative because they did not market the place. They had a tree that covered up their sign and it wasn't until it was in the press that the racetrack was closing down that people started to show up. You can’t use that standard to see if there can be success because what was done wasn’t that good. There is an absolute appetite in California for horse racing and we need to tap into that. If the machines were to come in tomorrow, we wouldn’t be talking about if the sport will survive but what are we going to do with all this money we are bringing in.

Nader: The jury is still out. We’ve established the metrics that CARF (California Authority of Racing Fairs) and the CHRB have agreed to and it’s too early to tell because we don’t have any data to pass judgment. It’s on the brink. As the North has stated on many occasions, “Give us a chance.” But I do think the chance comes with the obligation that the industry has to come together and make the call. It can’t be something like the North would be able to go forward with proving its worth in the final quarter of 2024 because the balance is too delicate with no secondary income in the state and the fact that both circuits are linked to each other to create a sustainable future.

O’Neill: Absolutely, not. I think it can be reversed in a positive way very quickly. I would love to see us turn someplace like Santa Anita into an equestrian center. If you could bring in that equestrian label, I think it has a better brand and reputation. And you would have a bigger pool of horse lovers and I think we have plenty of room here to do just that. If I hit the lottery and was president of Santa Anita for a couple years, my approach would be to focus on jobs and housing. I’d put new dormitories here, which gives you a bigger pool of horse lovers here who would work alongside horses for a living. I’d turn the back parking lot into an equestrian center or at least a mini-version of one.

Rubinstein: Absolutely not. California is a state with over 40 million people. We have loyal fans and a rich history of thoroughbred racing at the highest level. We have California people betting on the races, we have California owners at the sales. I talk to many high-level people and they all agree that California is essential to the long-term success of the industry.

How much time is left?

Butler: We’re not really looking at it in that way. We’re just looking to see what we can do at the moment to improve racing and the ecosystem around the track that involves the trainers and owners. We need to find that fine line where we can get everything we need to be done here.

Balch: Absent serious strategic brainstorming, less every day.

Bush: The question hinges on the success of Santa Anita. I think that question could best be answered by Belinda Stronach.

Ferraro: Sometimes it feels like we have a couple of days. I think we’ll know by the end of this year how bad a shape we’re in.

Oldfield: I think we still have time because we have the ability to do something we haven’t had in years and that’s chart a new course in the North. The North is not going to be the savior of the South but we have the ability to demonstrate that things can work and we can do things better and we can set those examples for other parts of the state. The future of racing is publicly held companies. What does that mean for Santa Anita? I don’t know. As a horseman in California, I absolutely want to see Santa Anita flourish, but I don’t know how that intersection of public and private could work to keep Santa Anita alive.

Nader: It would be advantageous if you could start with a clean slate and start over, but that’s not going to happen because of the complexities in the state and the way things are done. The key would be to get the secondary income stream and then chip away at the building blocks underneath to create a better structure. But you need that big change at the top.

Rubinstein: We have time and we’re focused on what we need to stay competitive with purses. I do think it’s important for us to stop and take a breath and look at the new dynamic without Golden Gate Fields. Losing Golden Gate changed the dynamic significantly.

What are the optimistic signs you see out there?

Butler: We’ve had numerous conversations with the TOC (Thoroughbred Owners of California) and they seem extremely supportive and seem to understand exactly what needs to be done in California. We are a little bit disappointed in the organizations that really don’t seem to grasp the amount of investment we continue to make to operate racing in California.

Balch: There simply aren't any. Even Santa Anita's decision to make a multi-million dollar “investment” in a synthetic training track was made in a vacuum, without considering other potentially more important and lasting changes. Other commitments made at the time for California breeding stimulus and major backstretch improvements, have been ignored.

D’Amato: I see my owners continue to buy horses from all over, not only inside the country but outside of the country, and continue to funnel them into California. We still have that going for us despite the disparity of purse money with Kentucky, Arkansas and New York. But as things start to go in opposite directions that window could change.

Ferraro: The loyalty of the horsemen here, and that Kentucky and the others are beginning to realize that they need California for them to be successful as well. Enthusiasm from trainers who want to make it work, that’s the best thing we have going for us.

Harty: The only optimistic signs are rumblings and rumors that the attorney general is looking into and searching for ways we can shore up our purse accounts. I was optimistic seeing the CHRB offering Northern California a lifeline. They are very, very small victories. We’re in a huge urban market. If Southern California can’t make a go of it, who can?

Oldfield: The one thing that is very optimistic is when Golden Gate announced it was going to close, there was this idea that everyone would scatter to the wind. But ultimately the horsemen in Northern California united more and better than I’ve ever seen. That alone was very optimistic and heartwarming. That gave me a level of hope about this industry.

Nader: It’s a huge state with so much importance nationally. We’ve got tremendous bandwidth as far as our buying power and our betting power not just in California but across the country. We’re over 20% of the national handle. The race tracks are so beautiful, the climate is great. The number of races that are carded on the turf that can actually run on the turf is high. It’s very conducive to horse players because of its reliability.

O’Neill: Closing day at Santa Anita you had 11 races on Saturday and 12 on Sunday. That’s optimistic. There was a record handle this year at the Kentucky Derby. That’s an optimistic sign.

Rubinstein: The progress of safety and that the Breeders’ Cup will be in California three straight years. The community, here at Del Mar, supports racing and the business leaders know how important racing is to the local community. On the racing side, Del Mar’s product has been as good as anyone’s over the last two years.

Can breeding in the state be sustainable with fewer Cal-bred races?

Butler: The breeders have been absolutely brilliant considering the circumstances. We’ve got to continue to offer a wide variety of Cal-bred races so we can give them a reason to continue their operations. The breeders have been working with us and understand what needs to be done and to try and get this fixed.

Balch: The issue is incentivizing breeding in California, wherever the Cal-breds run, whether in restricted or open company. California-bred thoroughbreds comprise the critical population of horses running at all California tracks, in all races except unrestricted graded stakes. California racing simply cannot be sustained without those horses filling races, especially overnights, since handle on overnights is what funds stakes purses.

D’Amato: Near the end of the Santa Anita meeting, there were 20 horses entered in both the 2-year-old Cal-bred girl and boy races. That’s a really good sign the California breeding industry is still going in the right direction. I don’t think we can survive as a circuit in California without a very strong Cal-bred program.

Ferraro: No, it can’t be. They have to be able to produce a certain number of horses to be viable. If there is not enough racing, there is not enough calling for those horses. Otherwise, you can’t sustain the breeding industry.

Oldfield: The awarding of dates by the CHRB, stabilized the breeding industry. A lot of people didn’t know if they were going to breed at all in California. When those dates were awarded it gave people hope to continue and breed. I don’t think racing in the state can be sustainable without Cal-breds. Most of the horses that run in the North are Cal-breds. If you look at the races that card the most horses, those are Cal-bred races. If Cal-bred races were to go away, it would have a devastating impact on racing and the horse population.

Nader: Yeah, I think it just has to be managed well. You just have to be smart and understand. The number of foals in California was 3,800 in 2003 as there are 1,300 today. There has been plenty of contraction and if there would be more it would be unfortunate. But in the end, if it’s managed correctly while still maintaining the quality of Cal-breds, I think we would be OK.

O’Neill: No. That part of California racing needs to be tweaked and fixed . I don’t know where they come up with the money to invest in the programs. It’s working on the negative as it is. If I had a genie and one wish it would be to have a guy like Paul Reddam to run the track. You would see an instant turnaround. He has that kind of business mindset that people would be tripping over each other to get into the track. There are people like that who just don’t fail. The Rick Carusos of the world, and if they do, they don’t fail long. I would love for a guy like Paul Reddam to own a track like this for a year or two and see what would happen.

What is the most important issue to address?

Butler: It’s really improving the purses which will allow us to improve the inventory, which improves the betting.

Balch: Saving, incentivizing, and stimulating California breeding. All you have to do is compare the behavior and commitment from New York, New Jersey, and Kentucky to racing. It demonstrates the critical importance of governmental action in a state-regulated industry like ours. Sadly, that regulatory/legislative constituency in California, which was once the hallmark of attention and education by California tracks, owners/trainers, labor, farms, agriculture, etc., was largely and effectively abandoned once California track ownership began evolving in the late 1990s.

Bush: Purses, perspective and the image of horse racing with our younger generation. We need to figure out how to get influencers involved. And get them to understand how much love goes into the care of these horses by people who have a passion and a bond with those animals.

Ferraro: The size of our purses. All of our problems stem from that one thing. The purses aren’t high enough so we don’t have enough horses, so we can’t run enough races. The public recognizes when you have a good race card, they come out. But when you have a lot of ordinary race cards, like we’ve suffered this year, they just won’t show.

Harty: The purses and the breeding. If better minds than I, like the California breeding industry, can get together with other Western states, so instead of it just being Cal-breds, New Mexico-breds, Arizona-breds, Washington-breds, Oregon-breds. They do that in other states, so it’s not a new idea, but it would help incentivize racing in California.

Oldfield: Most important issue is an outside source of income to address the purses. It’s something that everyone can unite behind . Not a single stakeholder would disagree with that. It would put California on a level playing field with other states.

Nader: I’ll speak on behalf of the horse player who looks to California racing and recognizes what it brings to the betting population. We have to make sure the product hits the brand and reputation from the expectation of horse players, the competitiveness, the field sizes and meet the expectations of horse players. We have to maintain our standards and make sure our purses and field sizes respect the great reputation of California.

O’Neill: The horseman moral is just about as low as I’ve seen it. I think we need to boost that up and what would boost it up is knowing that something is in the works that indicates we’re trying to build on-track business and on-track handle.

Rubinstein: We’ve obviously been on a very good run with safety and we can never be complacent with that. Business side we need to secure supplemental revenue sources.

Alan Balch - Fiefdoms redux?

I’m reminded of racing’s counterproductive fiefdoms by a 2008 writing in these pages of the late Arnold Kirkpatrick, my much-revered colleague and friend. Back then, it seemed to him, there were way too many fiefs in the way of industry-wide accomplishments.

To Arthur Hancock’s suggestion that our problems were caused by a lack of leadership, Arnold was “unalterably convinced that our problem is not a lack of leadership but too much leadership.” He counted 183 separate organizations in Thoroughbred racing alone, each with their own agendas and jealousies. “With 183 rudders all pointed in different directions, we have two possible outcomes – at best, we’ll be dead in the water; at worst, we’ll be breaking apart on the rocks.”

In 2024, can it be said, without irony, that this is the best of times, and the worst of times?

In North America, and California in particular, an historic sport and industry contraction is well underway, by every possible indicator – led by the declining foal crop. One might think there has been a corresponding contraction in the list of racing’s organizations; somehow, I doubt that’s true. Nevertheless, in the “Golden State,” once a perennial leader of American racing, we have lost a critical mass of tracks since 2008: Bay Meadows, Hollywood Park, fair racing at Vallejo, San Mateo, Stockton, and Pomona, and Golden Gate Fields this year.

Is it simply a coincidence that this all happened while one racing operator – the Stronach Group -- increasingly dominated and controlled the sport in California, as no track owner ever before was permitted to do?

Arnold’s word “fiefdom” . . . comes back to mind, but now from a different perspective. In European feudal times, as we learned in school, the fief was a landed estate given by a lord to a vassal in return for the vassal's service to the lord. There are a great many California owners, trainers, breeders, jockeys, vendors, fans, and even regulators, who have been wondering how the vassals ever turned the tables.

In a Los Angeles Times interview published on April 5, Aidan Butler, the chief executive officer of 1/ST Racing and Gaming, the Stronach operator, used the term “imbeciles” to describe those who would question the company’s intentions, and perhaps its motives, in sending what was widely perceived as a blatantly threatening letter to the California Horse Racing Board.

Instead, he termed the letter “transparent.” And then stated, “if nothing else, people have been forewarned.” Seconds before, he had claimed that the amount of money Stronach had invested in Santa Anita proved its good intentions. This is the same executive who months earlier had suddenly announced, giving stakeholders notice of only hours, that Golden Gate Fields would be closed within weeks, before changing his mind under pressure from the rest of the industry.

Confused?

Stronach’s track management may be described many ways; truthfully “transparent” is certainly not one of them, despite constant assertions to the contrary. As a private family company, even in a regulated industry, its leaders can claim whatever they want with impunity. After all, the exceptionally valuable real estate on which most (all?) of their track holdings reside appears to make them immune from audit or inspection: they rarely, if ever, are reluctant to tell their racing fraternity vassals that it’s their way or no way. The damage resulting from that attitude is staggering.

Edward J. DeBartolo, Sr., was a predecessor billionaire owner of multiple American tracks. Perhaps, however, because of his ownership of great and successful team sports franchises, among other interests such as construction, retail, and shopping center development, not to mention education and philanthropy, he knew what he didn’t know. He realized he always needed teammates. He delighted in saying to his fellow track owners that managing race tracks was by far the most difficult of all his enterprises, due to the elaborate interdependent structure of racing, and its nearly infinite number of critical component interests, each with different expertise. More complicated than any of his other pursuits, he said! To succeed in racing challenged him to learn, and his success resided in hiring, consulting with, and relying on people who knew more than he did. As it did in all his businesses.

Even to the most oblivious, it can’t have been hidden to the Stronach leadership that entering the heavily-regulated California racing market in the late 1990s would present serious challenges, at least as enormous as the opportunities. Acquiring the two glorious racing properties of Santa Anita and Golden Gate (with a relatively short leasehold at a third, Bay Meadows) had to have been exciting. To someone with the DeBartolo outlook on interdependent management, rather than the inverse, it could have been invigorating and boundlessly successful.

That the opposite has resulted is an enormous tragedy for the sport worldwide, not just in California. After all, the State of California’s economy (as measured by its own Gross State Product) is among the top five in the world, outranking even the United Kingdom’s. How could this happen?

Had Stronach leadership begun, at the outset, consulting and cooperating in good faith with its California partners (including regulators, legislators, and local communities, not to mention fellow racing organizations, the owners, trainers, breeders, and other tracks), learning from them as teammates rather than dictating to them, California racing would look far different now than it does. Its imperious and constantly changing management leadership compounded perennial problems and threats, not to mention complicating the industry’s politics and standing in California sports. Obvious failures to understand California markets and invest in sophisticated communications and marketing also have been apparent, despite continual assertions to the contrary.

Is there still hope for California racing? Yes . . . but if and only if honest humility suddenly appears from Stronach leaders, and immediate, sincere engagement occurs with all the rest of the interdependent entities upon whose lives and success the racing industry depends.

Alan Balch - What, me worry?

Article by Alan F. Balch

If you’re of a certain age, you can’t help but remember Alfred E. Neuman, the perennial cover creature of MAD magazine. I sure do, and not mainly because of the magazine’s content . . . I was a dead ringer for him. Skinny, gap-toothed, freckle-faced, red-haired, with crazy big ears. So my laughing “friends” said, anyway.

Kids can be so mean to each other.

Obviously, the teasing stuck with me. For a lifetime. But back then, I shared another trait with him: nothing worried me. Everything seemed like a joke. Like everyone else, I just yearned to grow up so I could be free. Free of school, free to live all day, every day, with horses in a stable, if I wanted. Which I did.

By college, though, I was an inveterate worrier, and still am. My best friend once said, “Alan, if you didn’t have anything to worry about, you’d be worried about that!”

We in racing, and in California particularly, have an overabundance of worries these days. How the hell did it all happen? From leading the world in attendance and handle a few short decades back, not to mention great weather, we have (not suddenly) come to . . . this.

In an interdependent sport, business, industry, such as ours, everything one part does affects all the others. No part can succeed without the others; if one fails, all fail. Unfortunately, there have been many failures to observe amongst all of us.

Ironically – but not entirely unexpectedly – I believe California racing’s historical prowess started to unravel in the best of times: the early 1980s. Our California Horse Racing Board regulators no doubt believed the industry was so strong that it could easily withstand disobeying a statutory command, which “disobedience” some of us believed could lead to disaster.

Hollywood Park sought to purchase and operate Los Alamitos, despite a clear prohibition in the law forbidding one such entity to own another in the state, “unless the Board finds the purpose of [the law] will be better served thereby.” Santa Anita’s management at the time objected strenuously, including in unsuccessful litigation, providing a “list of horrors” that might ensue if the delicate balance among track ownerships in the state were disturbed.

Among those horrors was the prediction that a precedent was being set for the future, where one enterprise might not only become significantly more influential than others, it could even become more authoritative and powerful than the regulator itself.

We at Santa Anita, whose management I was in at the time, were deeply concerned about our own influence and competitive position . . . and our reservations and predictions were largely ignored, undoubtedly for that very reason. At everyone else’s peril, as it has ultimately turned out.

That Hollywood Park acquisition move turned out to be ruinous. For Hollywood Park! And the cascade of repercussions that followed, including changes of control at that track, led to another fateful regulatory change in the early 1990s: the splitting of the backstretch community’s representation into separate and sometimes rival organizations of owners and trainers, which in every other state in the Union are joined as one. Before his death, the author of that idea (Hollywood’s R.D. Hubbard) said, “That was the worst mistake I ever made.”

Consider that in the first half-century of California racing, interests of the various track owners, as well as owners and trainers in one organization, were carefully balanced. No one track interest ruled, because the numbers of racing weeks were carefully allotted in the law by region.

Unilateral demands of horsemen went nowhere. Practically speaking, the Racing Law couldn’t be changed in any important way without all the track ownerships agreeing, with the (single) horsemen’s organization. In turn, that meant there were regular meetings of all the tracks together, often with the horsemen, or at their request, to address the multitude of compelling issues that constantly arose.

But when that balance was disrupted, even destroyed, is it any surprise that for the last three decades the full industry-wide discussions that were commonplace through the 1980s are now so rare that track operators can’t remember when the last meaningful one even took place?

Thoroughbred owners have meetings of their Board not even open to their own members, and never with the trainers’ organization. The Federation of California Racing Associations (the tracks) apparently still exists, but hasn’t even met since 2015. The Racing Board meets publicly, airing our laundry worldwide on the Internet, showcasing our common dysfunction and lack of internal coherence to anyone who might be tempted to race on the West Coast.

Not to mention those extremists who cry out constantly to “Kill Racing.” And one private company, which also owns the totalizator and has vast ADW and other gaming holdings, not to mention all the racing in Maryland and much of it in Florida, answerable to nobody, controls most of the Thoroughbred racing weeks in both northern and southern California.

Our current regulators didn’t make the long-ago decisions that set all this in motion, and may not even be aware of them. In addition, the original, elaborate regulatory and legal framework that was intended in 1932 to provide fairness and balance in a growing industry is unlikely to be effective in the opposite environment. And the State Legislature? All the stakeholders originally and for decades after believed nothing was more important than keeping the government persuasively informed, in detail, of the economic and agricultural importance of racing to the State. Tragically, that hasn’t been a priority for anyone in recent history.

Just to top it off: as an old marketer of racing and tracks myself, I believe in strong, expensive advertising and promotion as vital investments. For the present and future. I once proved they succeed when properly funded and managed; but I’m a voice in the wilderness now, to be certain, when betting on the races doesn’t even seem to be on the public’s menu.

What? Me worry?!

Alan Balch - Federalism Redux

As if we in American racing weren’t already facing serious threats to our very existence as a major sport, and an exceptionally elaborate interdependent business, now we’re also an example of the present national political dysfunction and irrationality. Just one more sharp dagger.

Over a half-century ago, I spent a previous lifetime in academia—studying government and political philosophy, with an emphasis on American political enterprise and evolution. When I joined Santa Anita, I never thought that I would one day witness at the racetrack the fundamental contradictions of the American founding!

But here we are, courtesy of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA). As you are probably aware, this addition of national government oversight to Thoroughbred racing, which had previously been the province of state-by-state regulation, came by way of its sudden inclusion in a must-pass federal budget bill in the waning days of the Trump presidency. Courtesy of Republican Party Leader Senator McConnell, of Kentucky—whose patrons The Jockey Club and Churchill Downs advocated for it.