The work being done on the prevention of serious fractures in the racehorse

Fractures: are they inevitable or preventable?

The incidence of serious fractures in horses racing on the flat is low (around one case every one to two thousand starters); but when fractures occur the consequences are often severe for the horse and, sometimes, the jockey. Both the severity and the dramatic nature of these injuries cause a significant negative impact to everyone connected with the horse, as well as spectators.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA) convened the Global Summit on Equine Safety and Technology at Woodbine Racecourse, Toronto, in June 2024, to focus on how current research into causes of racehorse fatalities on the course, including fractures, can be advanced and translated into action, to better understand the factors leading to fatalities and potentially mitigate them. At the meeting there were two workshops where specialist veterinary clinicians, pathologists and researchers came together to focus on Exercise Associated Sudden Death incidents and fractures.

Why do fractures occur?

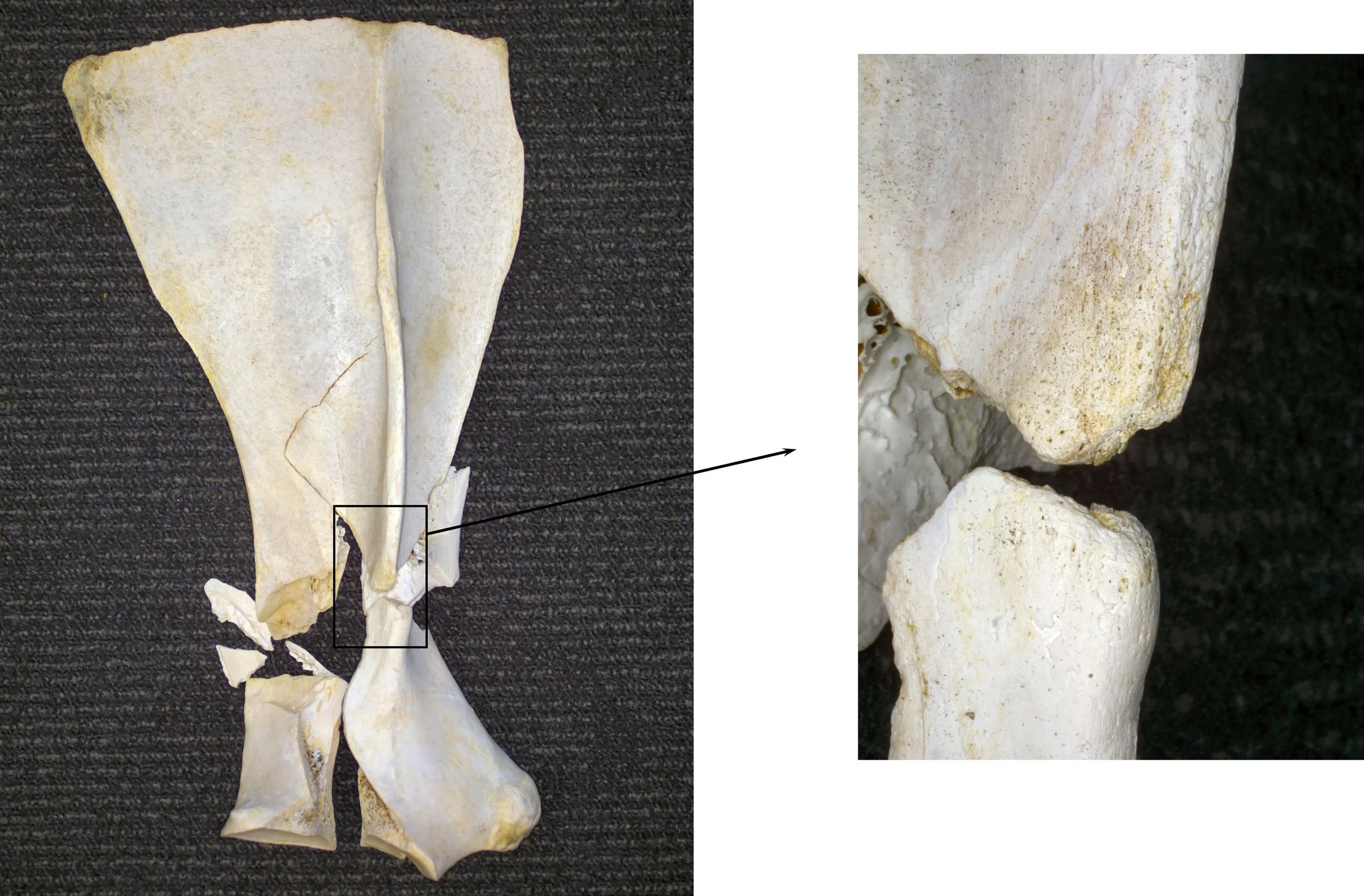

While most fractures that affect racehorses on the flat appear to arise spontaneously, while the horse is racing, and in the absence of any obvious trauma, we now know that the majority are the consequence of structural fatigue, involving a process that started weeks or even months earlier. Just as a paper clip will break if it is repeatedly bent once too often, a bone will fracture if it is loaded recurrently beyond certain limits. Microscopic damage accumulates in the bone tissue until a small fissure develops, which can extend to a severe fracture if it is not detected and the horse continues to race.

The fatigue life of bone decreases exponentially as the magnitude of load on the bone during each loading cycle increases. Loads on the skeleton are directly related to the speed of exercise, work at a fast gallop causes fatigue damage at a rate many orders of magnitude greater than when the horse is exercised at slower speeds. Unfortunately, fatigue damage, and even formation of small fissures in the bone, often proceed without the horse showing any outward signs and so, historically, affected horses have often gone undetected until it is too late.

Are there any natural biological mechanisms that protect against fracture?

An ability to run fast has been of evolutionary benefit to horses by enabling them to escape predators. Humans have refined this characteristic in specific breeds, notably the Thoroughbred, through targeted breeding and training practices. The need for a horse to undertake a fast gallop in the wild is likely to be relatively infrequent and well-within the bounds that are likely to cause fatigue damage. Conversely, society’s expectations of racehorses, and the training imposed on them, place loads on the skeleton that may be excessive.

Some readers may be surprised to learn that bone is a remarkably “smart” tissue. It is so much more than the equivalent of the “concrete structural beam” laid down to support man-made structures. While bone is composed partly of minerals, it is still very much a living tissue, packed with blood vessels, nerves and cells. Furthermore, the cells are all physically interlinked through microscopic projections, and can communicate with each other through their interconnections. This biological network allows bone tissue to detect the effects of loads applied to the bone as whole, and to initiate a cellular response to model the bone structure if those loads change.

For instance, increase in the magnitude of prevailing loads (e.g. through increase in an animal’s weight or the introduction of high-speed work) will cause greater deformation of the bone and this will stimulate a process that results in the formation of additional bone mass and, if beneficial, subtle reshaping of the bone’s geometry. The bone will be stronger as a result and deform less for the given load. Conversely, if the prevailing loads decrease (e.g. during a period of rest) bone deformation is reduced, and bone may be removed through a process of resorption. This overall mechanism of remodelling is called “adaptation”. Bone adaptation facilitates the formation and maintenance of a skeleton that is continually fit for purpose, even as that purpose changes.

Beyond this, there are biological mechanisms that detect when a bone is damaged (e.g. small cracks develop) and will initiate repair. The restoration process involves removal of microscopic packets of bone tissue, including the damaged portion, and its replacement with fresh, healthy material. This process means that fatigue-related damage of bone can be resolved and, theoretically, that a bone can tolerate infinite cycles of load. However, the process of repair has been shown to be inhibited if the bone is still regularly subjected to cycles of high load (i.e. the horse remains in training) and it can also be overwhelmed if the rate of damage accumulation is too high.

Are fractures something that racing just has to live with or can we do something about them?

Applying the knowledge we have gained from research over the past forty years has already had an impact on reducing the risk of fractures in some situations, and there are good reasons for optimism that we will be able to prevent a much greater proportion of racing fractures in the future. For example, epidemiological studies can help to identify certain management practices and design features of racecourses associated with an increased risk of fracture and these can be modified.

The introduction of strict rules governing the validity of sale of a horse in a claiming race in some jurisdictions in the USA, depending on the health status of the horse immediately after the race, has had a significant impact on reducing the incidence of fractures. Over 300 potential risk factors have been examined and those found to have a significant association with fracture, modelled in numerous studies.

Applying the findings to individual racecourses still requires much work and, ultimately, almost half of the variation in risk of fracture appears to be due to factors associated directly with the horse itself. Epidemiology has also been applied to identify characteristics of a horse’s history that may indicate that it is at higher risk of fracture. These studies depend on access to detailed and accurate data and recent work has highlighted the importance of including veterinary records. Access to these records, suitably anonymised to protect confidentiality, will have a profound impact in the development of more accurate models that can be used to predict the risk of fracture.

Studies into the genetics of Thoroughbreds have identified particular genes that are associated with a predisposition to fracture. This is a highly complex field and interaction of the environment and genetics ultimately determines the fracture status of an individual animal. However, genetic screening will help to identify horses that may benefit from closer monitoring. Clearly this is a sensitive topic, especially to breeders, although hopefully stakeholders will make choices that will be in the best interest of Thoroughbreds and racing in the long term.

Wearable technology, carried on the horse to record cardiac and stride data shows promise in being able to identify horses at early stages of skeletal injury. Preliminary results suggest that this is possible by identifying changes in stride characteristics, such as stride length, in individual animals in races leading up to the horse sustaining an injury. There has been a lot of interest and publicity associated with wearable technology and its use to identify horses both at imminent risk of fracture as well as those with irregularities of cardiac rhythm which may lead to exercise associated sudden death, although work still needs to be undertaken to substantiate their use in both these contexts.

These devices are also proving increasingly valuable as tools to record actual workload undertaken by individual horses in training. This is important information that is needed for researchers to accurately model associations between workload and risk of fracture, and for trainers to use to apply such models in the future.

Modern clinical imaging technology, especially that which allows detailed scrutiny of areas of bones in the locations where fractures commonly originate, facilitates identification of bone damage due to fatigue much earlier than was previously possible. The increasing availability of computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) machines that can be used to image the lower limb of the standing horse has made their application more practical in horses that are in active training.

There is potential for this technology to be used to screen horses prior to racing, as is currently undertaken before some race meetings in the state of Victoria, Australia. The enhanced resolution of CT helps to identify subtle fissures in bone that may be overlooked by conventional x-ray procedures and in such cases its value as a screening tool is indisputable. However, work is still ongoing to decipher the importance of even more subtle changes in bone structure. Undertaking imaging studies carries expense, and is not without some risk, and the concept of regularly imaging the relevant anatomical regions of racehorses to screen for risk of fracture clearly has challenges.

A simple blood test for “biomarkers” that could identify animals at an early stage of pre-fracture pathology would be a helpful tool. Even if the accuracy of such a test was insufficient to make important decisions about whether or not to race a horse, it could at least be used to reduce the number of animals that would need to be subjected to imaging studies.

Research into changes in the patterns of arrays of many molecules in the blood (so called “omics” studies) have led to many breakthroughs in screening systems in humans and animals. Preliminary studies give hope that this technology can be used to assist in the detection of horses at increased risk of fracture, although a practical test is still likely to be several years off.

It is important to acknowledge that all screening tests carry some risk: they may falsely identify normal horses to be at increased risk (false positives) and fail to recognise horses that have a problem (false negatives). Careful development and thorough testing of screening systems is therefore essential, and this takes time and money. Furthermore, no test is ever 100% accurate, and the practical application of screening designed to prevent fractures will require racing to strike a balance between stopping some normal horses from running and failing to identify some of those likely to suffer a fracture. This will require informed and engaged discussion between researchers and all relevant industry stakeholders, and strong leadership and clear communication from racing’s regulators.

Perhaps an even greater question is whether we can recommend ways of exercising horses in training that minimise the risk of fatigue damage that leads to fracture in the first place. Research conducted in Melbourne, Australia demonstrated that trainers who worked their horses at high speed in training less frequently than others experienced a lower incidence of fracture.

A very important additional bit of detail was that, excepting the extremes, their racing results and performance outcomes were no different. Recognition that bone is like other tissues, in that it needs time to respond to changes in physical activity and requires a training programme that accounts for this, is important. We are all well aware of the need to develop muscle to improve power and endurance in training, but the concept of training bone is less familiar.

Fortunately, an adaptive response of bone has been shown to occur reasonably quickly to only a few cycles of altered load. Stimulating young, healthy racehorses to increase the strength of their bones requires only a short distance of gallop work. Therefore, introducing a very small amount of fast work at the early stages of a training programme can be sufficient to prepare the bones for more sustained work without the risk of causing substantial fatigue damage. However, if the horse is rested from high-speed work for more than a few days, the process reverses, and bone mass will start to be resorbed (in evolutionary terms, there is no point wasting energy carrying around bones that are bigger and heavier than you need them to be).

So, when a horse is brought back into work after a period of rest, the process of training the skeleton has to be considered all over again. Periods of rest in themselves are also important to allow the bone to repair because even a sensitive training programme will result in some fatigue damage, and the accumulation of this damage may eventually lead to fracture. The innate, biological mechanism of bone repair is switched off (inhibited) while horses remain in active training and a period of rest is required for this process to be reactivated and for repair of fatigue-damaged tissue to take place. Therefore, periodic periods of rest from training are required in order to give the skeleton the best opportunity to heal and “reset” itself.

In summary, a training programme that:

reduces the distance of work (especially high-speed work) that a horse undertakes in its racing career to optimal levels that promote bone health (while racing and training);

stimulates appropriate development of bones through short bursts of fast work early on in a training campaign;

builds periods of rest into a horse’s life span in training;

will all reduce the risk of accumulated fatigue damage that predisposes to fractures developing.

To move forward, the industry needs to invest in research so that metrics can be developed to help trainers to apply these concepts to their own training techniques in a practical way. There will be a range of durations and speeds of work that will reduce the risks of fracture across different populations of Thoroughbreds, and these will only be demonstrated by investing in studies measuring the effects of different training regimes in significant numbers of horses.

Scientists and Racing Working Together

Developing and applying measures that are designed to reduce the risk of fracture will require the commitment of all stakeholders. We also need to be realistic in acknowledging that, due to the athletic nature of racing, the risk of a racehorse sustaining a fracture will never be eliminated and, sadly, for some of these injuries euthanasia will be the only humane option.

When racing authorities communicate to the public that the safety of equine athletes in racing is a priority, their credibility is clearly demonstrated by investing in work to bring the risks of injury, including fractures, down to the lowest possible level.

There will inevitably be an element of “pain” associated with the work and changes required to reduce injury rates. Screening systems will disrupt normal cycles of work, there will be frustration as horses that appear fit are withdrawn from races on the basis of findings of “risks” that we might find difficult to conceptualise, there will be additional financial demands to fund studies, and a sense of exposure as records that are necessary for researchers to do their work are shared, even with promises of confidentiality and anonymity.

At the Toronto meeting, the IFHA has already committed to supporting global scientific research efforts to reduce the incidence of racehorse injuries, including fractures. I look forward to the benefits this co-ordinated approach to research can bring by both reducing injury rates in equine athletes, and at the same time, demonstrating to society the priority racing gives to equine welfare.

Young racehorse development through the lens of biotensegrity and fascia science

The debate surrounding the appropriate age to commence racehorse training remains a contentious topic. Advocates of traditional biomechanical models argue that training at 18 months is premature, as a horse's skeletal system does not reach full maturity for several more years. However, skeletal development alone presents a limited perspective. I would like to introduce another perspective from a rising research field. Through the lens of biotensegrity and fascia science, a more comprehensive approach emerges—one that considers the interconnectedness of a horse’s entire physiological system. Well-structured training at a relatively young age can support the holistic development of the racehorse, fostering both physical and psychological adaptability.

The Influence of gravity and early adaptation

From the moment a foal is born, it must quickly adapt to the force of gravity. Passage through the birth canal initiates its structural alignment, and within hours, the foal is standing and moving independently. Foals are born with predominantly fast muscle fibres (2X). The ability to travel up to seven kilometers daily alongside its dam is a testament to the foal’s inherent adaptability. This early exposure to movement and environmental stimuli plays a crucial role in its physiological and neurological development.

Challenging traditional views on skeletal maturity

This article seeks to introduce an alternative perspective on how the horse interacts with gravity, incorporating the principles of biotensegrity and fascia. It is important to note that most research is done on corpses and the fascia dries out almost directly after the circulation stops. Traditionally, equine skeletal maturation has been the primary concern regarding the timing of racehorse training. However, a singular focus on bone development overlooks the adaptability of connective tissues and the overall structural integrity of the horse. All young horses as an adaptation to their environment are in a critical phase of learning and adaptation—both physically and mentally—which must be accounted for in any training approach.

Veterinary discourse on skeletal maturity presents conflicting perspectives. Veterinarian Chris Rogers asserts that the skeleton of a two-year-old Thoroughbred is sufficiently developed for training, drawing parallels to human child development. Conversely, Dr. Deb Bennett posits that full skeletal maturity does not occur until six to eight years of age regardless of breed. All horses go through almost the same skeletal development phases, although thoroughbreds are extremely adapted through breeding to grow much quicker. While Bennett’s perspective has been widely accepted, Rogers’ viewpoint aligns with the practical realities of racehorse development, supporting the industry’s traditional training timelines.

Flat racehorses typically begin training at around 18 months of age. At this stage, their skeletal and connective tissues are still developing, as research consistently shows. Cartilage, bones, muscles, and ligaments undergo intensive growth and adaptation. Every experience the young horse encounters contributes to its physiological and neurological development, shaping its ability to perform the tasks expected of a racehorse. Training at a young age offers several advantages, as young horses are highly receptive and adaptable. As explored later in this article, their connective tissues develop in response to the challenges they are exposed to, reinforcing their structural integrity over time.

Racehorse training inherently involves a selection process. Horses that do not meet performance expectations within the first few seasons are often retired from racing by the age of three or four, making way for new yearlings. Those that demonstrate both speed and durability may continue competing well into their later years. Those are often geldings. Mares and stallions that show promise may transition into breeding programs. The rest, if their foundational training has been well-structured, can adapt successfully to second careers as riding horses, often becoming ideal partners for young equestrians at the start of their horsemanship journey.

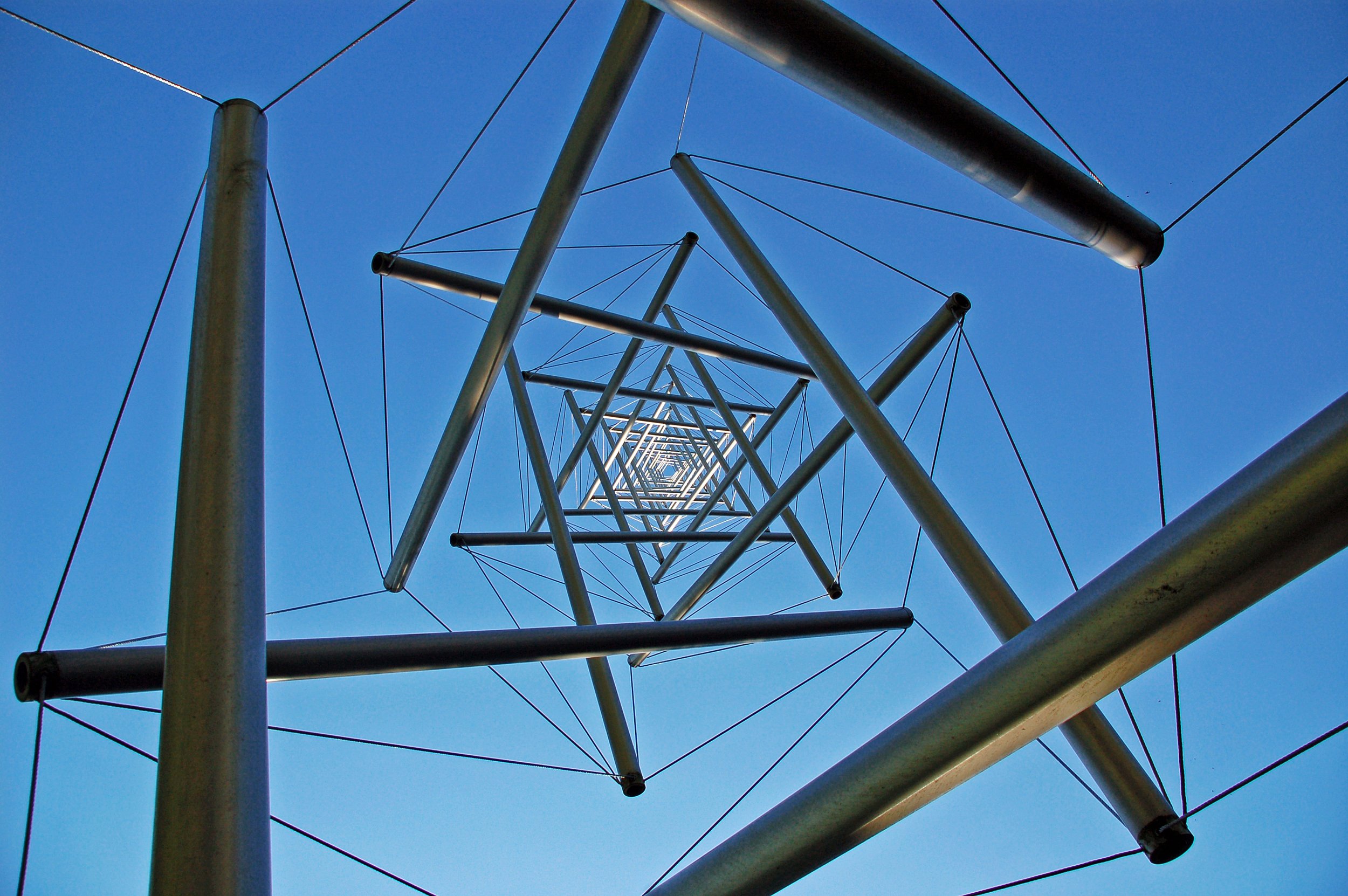

Tensegrity principles

Tensegrity (tensional integrity) is a structural principle that explains how forces of tension and compression interact to create stability in a system. Originally coined by architect and engineer Buckminster Fuller, tensegrity has been widely applied in biological systems, including human and equine anatomy.

The role of fascia and biotensegrity in equine development

A traditional biomechanical view perceives the horse's skeleton like a rigid brick wall—if one part weakens, the entire structure becomes vulnerable to collapse. In contrast, a tensegrity-based perspective views the horse as a dynamic suspension bridge, where forces are distributed across an interconnected network of fascia, tendons, and ligaments. In this model, the skeleton is not a rigid load-bearing framework but rather ‘floats’ within the fascial system, allowing for adaptability, resilience, and efficient force distribution.

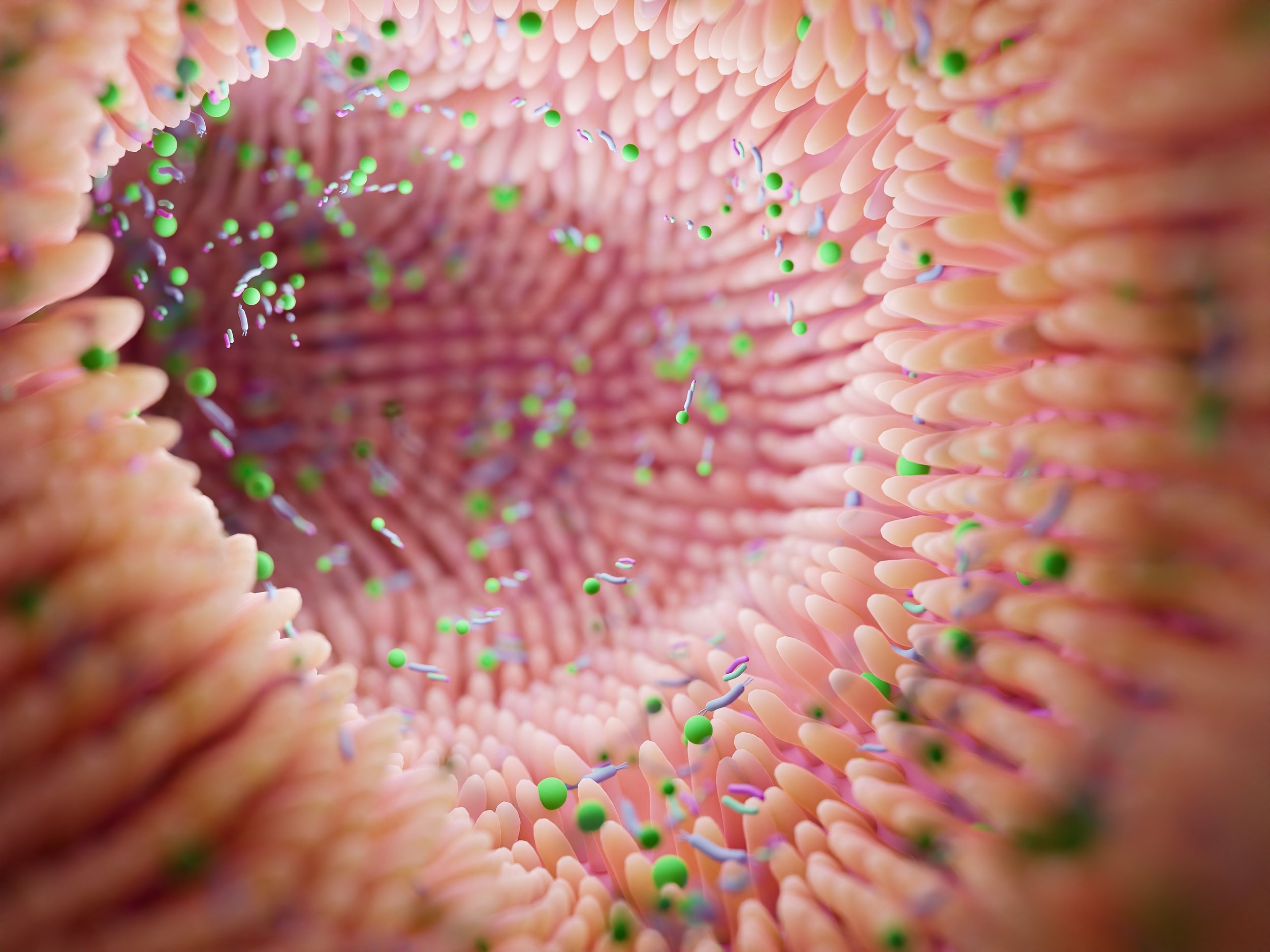

Biotensegrity highlights the balance between tension and compression within the body. In equine anatomy, the skeleton functions as a stabilizing framework, while fascia, tendons, and ligaments manage dynamic forces. Fascia, composed predominantly of collagen, exists in various densities, from loose connective tissue that facilitates muscle glide to the more rigid structures forming tendons and bones. This complex, fluid-filled network plays a crucial role in maintaining stability, distributing forces, and mitigating the impact of training.

Training influences the structural adaptation of connective tissues. Properly executed, it can enhance durability and resilience, reinforcing ligaments and tendons much like steel cables under controlled tension. Understanding the dynamic interplay between muscle, fascia, and skeletal development allows for training methods that optimise long-term soundness and performance.

Fascia

One of the most abundant proteins in the body is collagen, which forms connective tissue in all its various forms—from loose fascia, which separates muscles, to denser collagen structures that align with the direction of force and develop into tendons, ligaments, or bone. One of the key functions of loose fascia is to allow muscles to glide smoothly against one another without friction when one muscle contracts and another stretches.

Loose fascia consists of a collagen network, with its spaces primarily filled with water and hyaluronic acid. It is a highly hydrated structure—young horses are composed of approximately 70% water. Imagine a water-filled balloon, where the skin acts as the boundary between the internal and external environments. During fetal development, collagen structures form first, providing the framework within which the organs develop. Collagen, a semiconductive protein, relies on water to function optimally.

The water-rich environment surrounding fascia transforms it into an extraordinarily intelligent communication network. Its function is highly responsive to the body's pH levels, adapting moment by moment to internal conditions. As the central hub for force transfer and energy recycling, fascia provides immediate balance and support—often operating beyond the constraints of the nervous system.

Fascia's remarkable adaptability is rooted in its multifaceted properties. It is nociceptive, meaning it is capable of detecting pain and harmful stimuli, alerting the body to potential injury or strain. It is also proprioceptive, enabling the body to sense its position and movement in space, which aids in maintaining coordination and balance. Additionally, fascia exhibits thixotropic properties—allowing it to shift between a gel-like state and a fluid-like state depending on movement, which enhances flexibility and responsiveness.

Finally, fascia demonstrates piezoelectric properties, generating electrical charges in response to mechanical stress, playing a crucial role in cellular signaling and tissue remodeling. These combined characteristics enable fascia to dynamically adjust to both mechanical and biochemical stimuli, ensuring optimal function in response to ever-changing internal and external conditions."

Fascia has no clear beginning or end; it distributes pressure and counteracts the force of gravity.

The biotensegrity of equine locomotion and how horses rest while standing

Horses possess a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that allows them to rest while standing, a capability underpinned by the principles of biotensegrity. This structural efficiency is achieved through an intricate network of tendinous and ligamentous locking mechanisms working in harmony with the skeleton.

In the forelimbs, the extensor and flexor tendons engage to stabilise the skeletal structure, minimizing muscular effort. Meanwhile, in the hind limbs, a specialised locking mechanism is activated when the patella (kneecap) is positioned against a flat section on the femur just above the stifle, further contributing to this passive support system.

This adaptation allows horses to conserve energy while remaining poised for rapid movement. In the event of sudden danger, they can instantly transition from rest to flight, ensuring their survival—an essential trait for both wild and athletic performance. The efficiency of this natural support system exemplifies the principles of biotensegrity, where tension and compression forces work in balance to maintain structural integrity with minimal effort.

The head and neck function as critical balancing structures, comprising approximately 10% of the horse's total body weight. The forelimbs bear roughly 60% of the body’s weight, but true structural support originates from above the elbow joint. The spine, a central element of equine biomechanics, acts as a suspension system. The primary function of the equine spine is to support the internal organs, a role that also enables the horse to carry a rider.

This structural foundation ensures both stability and balance, allowing for efficient movement and performance under saddle. The propulsion generated by the hind legs is efficiently transferred to the forehand through the back muscles, which are reinforced with robust connective fascia plates, ensuring optimal movement and stability. This structural complexity underscores the need for a training regimen that respects the developmental timing of multiple interrelated systems beyond just the skeletal framework.

Risks and adaptations in young racehorses

While early training offers advantages in developing resilience in young racehorses ( they have a high percentage muscle fiber 2X), it also presents risks. The spinal column, particularly the lumbar-sacral junction, endures significant forces during high-speed galloping. Without appropriate conditioning, the vulnerability of these structures can lead to pathologies such as kissing spines or pelvic instability. Their growth plates remain open, making them more susceptible to the impact of high-speed forces, compensatory adaptations to early training stress may manifest as different maladaptive adaptations in connective and skeletal tissues, potentially diminishing long-term performance capabilities.

However, when managed correctly, the high adaptability of collagen structures in young horses allows for positive adaptation. Training introduces controlled tensile and compressive forces, fostering the development of strong, functional connective tissues. The challenge lies in striking the right balance between stimulus and recovery to optimise long-term soundness and athletic potential.

The value of tacit knowledge in training practices

Experienced trainers have an intuitive understanding of the complex relationships between tissues and biomechanics, a knowledge that is often honed through years of careful observation and practical experience. This tacit expertise is fundamental in shaping training strategies that take into account the horse’s overall development. A comprehensive training program should not only focus on the maturation of the horse’s bones but also prioritise the adaptive growth of fascia, ligaments, and muscles. By doing so, trainers ensure that young racehorses develop in a way that is aligned with their evolving physiological capabilities, promoting balanced growth and minimizing the risk of injury. This holistic approach allows for the optimal performance and longevity of the racehorse, fostering a more sustainable path toward peak athleticism.

Conclusion: a holistic perspective on racehorse development

The evolution of equine training methodologies has greatly benefited from recent advancements in scientific understanding, offering a more refined approach to racehorse development. By incorporating biotensegrity principles into training programs, a more comprehensive view of the horse’s physical structure and function emerges, shifting the focus from skeletal maturity alone to a broader understanding of the interconnected roles of fascia, connective tissues, and adaptive biomechanics. This shift in perspective allows for the cultivation of healthier, more resilient athletes who can perform at their peak while minimizing the risk of injury.

With equine welfare at the forefront, adopting a holistic approach to racehorse development—one that blends cutting-edge biomechanics, physiological insights, and traditional training wisdom—will pave the way for more sustainable, ethical practices within the industry. Such an approach not only enhances performance in the short term but also ensures the longevity and well-being of racehorses throughout their careers. Ultimately, by embracing this integrated perspective, the racing industry can promote a future where both the performance and welfare of horses are prioritised, leading to a more ethical and effective standard of training.

---

Extra Reading References

- Levin, S. (Biotensegrity: www.biotensegrity.com)

- Clayton, H. M. (1991). *Conditioning Sport Horses*. Sport Horses Publications.

- Adstrup, S. (2021). *The Living Wetsuit*. Indie Experts, P/L Austrasia.

- Schultz, R. M., Due, T., & Elbrond, V. S. (2021). *Equine Myofascial Kinetic Lines*.

- Bennett, D. (2008). *Timing and Rate of Skeletal Maturation in Horses*.

- Rogers, C. W., Gee, E. K., & Dittmer, K. E. (2021). *Growth and Bone Development in Horses*.

- Ruddock, I. (2023). *Equine Anatomy in Layers*.

- Myers, T. W. (2009). *Anatomy Trains (2nd Edition)*. Churchill Livingstone.

- Diehl, M. (2018). *Biotensegrity*.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). *The Structure of Scientific Revolutions*. University of Chicago Press.

- Tami Elkyayam Equine Bodywork

Maximising the stable environment - covering aspects such as ventilation, flooring, bedding, lighting and the use of therapeutic tools for the stabled horse

Article by Adam Jackson

Horses stay in their stables for different durations based on their care, training regime, health status, and seasonal changes. Ensuring your horse's comfort and well-being in their stable is crucial, as inadequately designed facilities can lead to injuries, health issues, and fire hazards. With horse welfare under the spotlight with the focus being on the keeping and protection of animals under the European Union review, there is no better time to look at how we can maximise the stable environment.

Ammonia

Ammonia is a serious irritant that can harm the respiratory tract and cause breathing difficulties. Lower concentrations of ammonia can irritate a horse's upper respiratory tract, while higher levels may skip this area and lead to inflammation and fluid buildup in the lower lungs. Ammonia triggers inflammation, which increases mucus production and disrupts the function of cilia in the respiratory tract, negatively impacting the immune response. When cilia malfunction, dust and dirt can accumulate in a horse's lungs, causing health issues and decreased performance.

Monitoring ammonia levels in stables is crucial, as levels should ideally be below 10 ppm, and an odour of ammonia typically indicates levels are dangerously elevated at 20-30 ppm, which can harm horses' health.

Bedding

Ammonia can be managed effectively through proper stable management in addition to ensuring good ventilation. To improve the absorption of urine and faeces and lower ammonia levels, add extra dry bedding in the areas of the stable where the horse often soils. A recent study has shown that even with regular cleaning, elevated ammonia levels can remain near the floors. Using a combination of highly absorbent bedding materials and an ammonia-neutralising product can help lower ammonia levels.

Bedding made of pine shavings is excellent at controlling the ammonia levels. The pine oil in the shavings tends to inhibit the bacteria that converts urine into ammonia, thus keeping the ammonia levels low. In addition, bedding that has strong shavings provide cushioning rather than compacting together.

Stable floor setups

The type of surface on which a horse stands for extended periods can significantly influence its comfort, movement quality, and overall soundness. Consequently, it is essential to invest time and resources in choosing the appropriate flooring for your stables. Moreover, selecting the right flooring can enhance operational efficiency and lower costs associated with hygiene management and stable cleaning. Finally, conduct routine inspections of your flooring to guarantee safety and avert potential hazards.

There are two main categories of flooring: permeable and impermeable.

Permeable or porous stable flooring can consist of either conventional packed clay or a specially engineered geotextile membrane. In the case of the latter, the membrane layers act as a barrier between the horse and bedding and the underlying base material.

In both scenarios, it is essential to install pervious materials on a foundation of well-graded crushed and compacted stone. There are disadvantages associated with the use of pervious flooring. While packed clay is softer than cement or asphalt, it is prone to becoming uneven when exposed to additional moisture, particularly if deep bedding is not utilised.

Membrane layers can also contribute to urine accumulation, leading to an increase in ammonia levels that negatively impact the respiratory health of horses. Furthermore, this moisture can permeate the underlying base material, resulting in the development of unpleasant odours. Another significant issue with this type of stall construction is the potential for groundwater contamination.

Stable flooring that is impermeable or impervious is specifically engineered to stop urine and moisture from seeping through. To facilitate the elimination of urine and faeces, it is essential to either grant the horse access to an outdoor space or to supply bedding that can absorb moisture and offer cushioning.

It is essential to have a solid foundation beneath for the entire system to function effectively. Stall flooring consists of a base layer and an upper layer of material. If the base is not properly established, the overall performance will be compromised.

Additionally, rubber matting is regarded as an ideal durable choice due to its ability to mitigate hardness, alleviate fatigue in the horse's legs, and simplify the cleaning process. Rubber mats may require a significant initial investment; however, they offer long-term benefits by facilitating consistent cleaning, lowering bedding expenses, and enhancing the health, comfort, and overall wellbeing of horses.

A correctly installed rubber mat should be even and stable while offering a degree of cushioning. The market offers a range of matting options, including custom wall-to-wall installations and interlocking mats. It may be beneficial to explore mats that are thicker and more cushioned to provide insulation against cold floors and to minimise the risk of pain in the hip, stifle, hock, fetlock, and pastern areas.

In certain circumstances, it may be necessary to install a drain in a non-porous stall to facilitate the collection of liquids. A drain is particularly beneficial in veterinary or maternity stalls that require regular washing. Drains should be situated near a wall, and the stall should be graded appropriately. If drains are installed, ensure that cleanout traps are included to capture and eliminate solid waste.

Ventilation

Good ventilation in stables is essential for removing bad odours, improving indoor air quality and humidity, which supports horse health, while also controlling temperature and condensation to extend the building's lifespan.

Horses are obligate nasal-breathers and grazing posture hinder their ability to effectively clear dust and debris from their respiratory systems. Prioritising good ventilation is essential for maintaining horses' health, as it mitigates the risks of respiratory diseases caused by airborne pollutants. Failure to minimise airborne particulate matter like mould, mildew, and dust-borne bacteria can lead to serious respiratory diseases, including asthma, allergic reactions and upper respiratory tract viral infections (i.e. herpes, influenza).

Another source of moisture is the condensation that develops within the barn. Inadequate ventilation, especially from closed doors during cold weather, can lead to increased moisture buildup indoors. The horses themselves are a source of moisture and with the more horses kept in for longer periods, the more condensation that is generated. Therefore, it is vital to refresh the air inside the barn constantly to ensure the health and well-being of the animals.

Natural ventilation offers the most affordable solution with minimal initial investment, zero maintenance expenses, and no energy consumption. However, a combination of natural and mechanical ventilation can enhance air quality and comfort in a stable block.

Installing air inlets low and outlets high in the barn harnesses the natural tendency of warm air to rise, improving ventilation efficiency. To optimise ventilation, high outlet vents should be installed at the roof's ridges, where warm air naturally accumulates.

During winter, the barn doors may remain shut to retain heat, while strategically placed vents ensure adequate airflow, and in summer, windows and stable doors may be left open to promote ventilation and comfort. Using horse body heat to warm a stable leads to very poor interior air quality due to inadequate ventilation and the accumulation of ammonia and other gases. In a well-ventilated, unheated stable with good air quality, the air temperature typically stays within 0-5° C / 5-10° F of the outdoor temperature.

A well-designed mechanically ventilated barn allows for precise regulation of indoor air quality, surpassing the capabilities of a naturally ventilated barn. Power ventilation systems in barns often incorporate exhaust fans and high-volume, low-speed units strategically placed in main aisles, barn ends, or between stables for optimal airflow. Individual fans in stables or aisles primarily serve to disperse particulates and repel insects rather than provide significant cooling.

If you are designing a brand new stable, the steeper the pitch of the roof, the faster the stale air will exhaust through the top ridge vents.

Vents and grates at the bottom of stable partitions help improve air circulation, effectively reducing ammonia fumes from urine. Stabled doors should feature grated panels to ensure both security and proper ventilation.

Water Supply

A steady availability of clean, fresh water is crucial for preventing dehydration and colic. You can provide water in your stable using either buckets or automatic drinking bowls, depending on your setup.

Automatic drinking bowls can be costly and require installation. It's difficult to gauge your horse's water intake, but you can minimise physical labour in the yard and make sure your horse has constant access to fresh, clean water.

Water buckets are an affordable choice and you can track your horse's water intake, but it involves lifting and transporting the buckets to and from the stable.

Lighting

Horses possess an internal timing mechanism known as a circadian rhythm, which regulates various physiological and behavioural functions. This internal clock is controlled by the daily 24-hour cycle of light and darkness and operates in nearly every tissue and organ.

Scientific research supports the use of lighting systems that emit blue light similar to sunlight is advised for daytime use and a soft red light should be utilised during the night. Enhancing stable lighting can optimise the horse's health and wellbeing by supporting its natural circadian rhythm. All elements of their physiology can function more harmoniously and in sync with the environment.

Social interactions

Recent studies indicate that private stables may not promote health and well-being as effectively as communal environments. The results indicated that horses housed in 'parcours' exhibited minimal abnormal behaviours like stereotypies, had the freedom to move throughout most of the day, engaged with other horses, and maintained positive interactions with humans.

Although this may not always be viable within training yards, stable adaptations can be made to increase social interactions. Windows in stables with views to other stables or paddocks allow horses to see and interact, even if they are not in direct contact, stall partitions with bars allow for visual and olfactory contact and individual turnout paddocks or pens allow horses to graze and interact in close proximity.

Feeding and entertainment

Horses should ideally have unrestricted access to hay; however, using slow feeders or automated feeders are also available to provide small portions throughout the day.

Entertainment devices can also help stimulate interaction and engagement, reducing the chances of stress and the emergence of negative habits (vices). Stable toys, mineral licks, stable treats, spreading forage in different locations, visual stimulation such as mirrors and brushes affixed to walls or fences all offer enrichment.

Technology

A range of technology is increasingly accessible to facilitate continuous care around the clock. Technology has the potential to staff, allowing them to redirect their time towards enhancing equine welfare.

The integration of camera-GPS surveillance with specialised software monitors the movements of individuals and determines the typical behaviour patterns for each horse within the herd. This cost-effective technology can alert yard personnel if a horse exhibits unusual behaviour.

There are a range of therapeutic technologies that can be utilised in the stable environment such as massage rugs, leg wraps and boots and handheld complimentary devices; as well as additional training and rehabilitation systems such as spas, treadmills, combi floors and solariums. All of which can be considered for enhancing the horse's well-being.

Conclusion

Ensuring the comfort and well-being of the horse within the stabled environment by adapting structures and utilising enrichment tools can help prevent injuries, health issues and fire risks. By promoting best practice for keeping the competition horse and ensuring natural behaviours are expressed as much as possible within the training regimes, will only benefit the horse thus increasing performance results.

Spring allergies - how to treat spring allergies and the effects they have on the respiratory tract

Article by Becky Windell

Spring allergies – peak season of the year-round battle

As obligate nasal breathers horses are predisposed to inhaling respirable dust, mould, pollen and other irritants from the environment. Whilst they have defence mechanisms to deal with it, the horse can be overloaded with the amount they are exposed to.

Springtime brings an array of newfound pollen from trees, grasses, and crops including the infamous oilseed rape (OSR). This pollen offensive comes in addition to the other allergens in the horse’s environment often surpassing the threshold of irritant load. This can result in respiratory based “spring allergies” with inflammation in the airways leading to allergen based equine asthma. Either subtle signs such as poor performance and reduced stamina will appear and/or more obvious clinical signs such as coughing and nasal discharge. Horses will tire early due to the reduced amount of oxygen being taken up by the blood from the lungs.

Plants are polyploids and show many gene duplications so cross reactivity among species in which different antigens appear similar to the immune system can amplify the horse’s response to pollen and is particularly the case for grass pollens.

Generally intact pollen grains range from 10–100 μm in size, this is bigger than respirable particles which are classified respirable at <5 μm. Therefore, pollen has not generally been implicated in Equine Asthma and tends to be considered more of an irritant than allergen. However, a study by White et al identified an association with pollen in a group of horses with Severe Equine Asthma (SEA) while looking at bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples compared to healthy horses2. The effects of pollen on the horse is an area where more research is needed.

Oilseed rape on the decline

It’s well documented that oilseed rape (OSR) is a concern for trainers with some experiencing underperforming horses while surrounding fields are flowering oilseed rape crops.

Whilst it’s still unclear if there’s truly an allergic component to it, it certainly seems to irritate a lot of horses and vets see pollen in the tracheal washes when OSR is in flower.

A study in people comparing spring allergy symptoms of people living near OSR and those living far away, found small but significant excesses of cough, wheeze, and headaches in spring in the oilseed rape area. Interestingly they also found counts of fungal spores were mostly higher in the rape than the non-rape areas so perhaps pollen is not the culprit but fungal spores on the crop…?

This is worth noting as fungi is proven to cause respiratory problems in horses. A study by Dauvillier et al found horses with fungal elements observed on the tracheal wash (TW) cytology had 2 times greater chance of having equine asthma than horses without fungi. They also found the risk of being diagnosed and likelihood of fungi in TW were higher when horses were bedded on straw or fed dry hay which are key sources of fungi in the horse’s environment.

Practical solutions to OSR have been for trainers to purchase neighbouring fields or pay their neighbouring farmer not to grow the OSR.

From the farmer’s perspective OSR has been an essential part of the arable crop rotation for many years now. It is a crop specially planted to give the cereal crops a ‘break’ from the cycle of weeds, pests and disease that build up in the soil. This helps to improve the yield of the crops that are grown afterwards, such as wheat.

It used to be good for removing grass weeds too but has become less useful for this purpose in recent years due to weed resistance. In fact, a number of previously positive reasons to grow OSR are no longer standing up. A flea beetle which previously could be treated with a neonicitinoid is no longer licenced for this use, soil borne diseases have become a problem, and the crop does not do well in the wetter winters.

Ultimately it is now less profitable. This is good news for trainers with farmers starting to use the crop less often and perhaps grow it every 6th year rather than ever 3rd year in a field. Its use is on the decline in UK/Ire and this can been seen in government figures, in 2023-24 all regions in England saw decreases in the oilseed rape area with the largest proportional decrease seen in the North East and the overall decrease of OSR grown in the UK of 27%. While in Ireland Winter oilseed rape declined by 30% in 20246.

Now the interesting question in time is how much will the incidence of spring allergies reduce with the reduction in oil seed rape?

Global Warming

Dr. Emmanuelle Van Erck Westergren, founder of Equine Sports Medicine Practice in Belgium cautions about the effects of global warming on seasonal allergies. Global warming is altering fungal behaviour and distribution, offering conditions that provide opportunities for fungi such as Apergillus and increases the risk of mycotoxins. In addition the burden of pollen is increased by warming temperatures.

Diagnosing spring allergies

Regular, routine tracheal washes (TW) are useful as a quick and easy “screening” procedure. They help monitor how inflamed the airways are by looking at the neutrophils and macrophage cells. Normal samples are typically of low to moderate numbers of nucleated cells, the nucleated cells being mostly macrophages, with <10% neutrophils. An elevated proportion of neutrophils in the TW is considered to indicate airway inflammation, and cutoff values for neutrophil percentage have been set at 20% for TW.

Ian Beamish partner at Baker McVeigh Lambourn equine practice says he uses the tracheal wash to see “how the army is looking” in terms of number of cells and how many of those cells are dying on the battlefield.

He also warned “Ultimately, it can be a struggle to determine the actual cause of inflammation of the airways. Whilst spring allergies is a strong possibility at this time of year it could be any number of allergens from the environment causing it or simply the addition of more burdening the system. And then it could also be a virus! It’s important to remember racehorses are immune suppressed from being in full training so they are susceptible to low grade viral disease which can present with similar poor performance.”

To establish if the horse is truly allergic or if it is simply an irritation of the airways there is a diagnostic blood test for allergens. Measuring allergen-specific IgE antibodies present in the serum, can help to identify environmental allergens for both allergen avoidance purposes and to select for inclusion in allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT). This can be a helpful aid for diagnosing allergic disease but has been known to give occasional false positives so cannot be relied upon. Establishing the specific allergy is unfortunately very difficult.

Performance Horse Consultant and highly experienced equine vet Peter ‘Spike’ Milligan advises to first and foremost control what you can.

“Reducing contact with pollen can be extremely challenging so first focus on what you can control. Irrespective of the time of year, regularly re-evaluate the stable environment as well as the forage and bedding quality. This includes how they are stored, prepared and used to ensure the allergen and irritant load is as low as possible.”

A useful tool

The pollen count measures the number of pollen grains in a given volume of air and can indicate if it is a day the horse will be exposed to high concentrations of pollen. Pollen count is affected by the season, weather and even the time of day. The largest concentrations of pollen are found on days of high radiation and wind, early in the morning when pollen is first shed when the air is warming and rising and in the evening as the pollen in the air descends to nose level with the afternoon air-cooling.

The pollen count can be checked daily on weather apps. Where possible, it’s advisable to adapt the horses training schedule in line with the pollen count and keep training sessions less strenuous on the days the pollen count is high.

Treating spring allergies

Treatment of horses with allergen-induced equine asthma focuses mainly on decreasing and controlling airway inflammation. The standard and effective cornerstone treatment is to give a systemic or inhaled corticosteroid and if necessary, a bronchodilator can also be used.

The preferred method to administer these tends to be via a nebuliser because inhaled therapy delivers the drug directly to the lungs and helps to loosen mucous. In addition, a lower dose can be used reducing the chance of side effects and shortening the drug withdrawal time required prior to racing.

Recent advances in treatment include a specifically designed inhaler with a different inhaled steroid, ciclesonide, studies have demonstrated improved clinical signs in a group of horses with mild to severe equine asthma.

However, whilst corticosteroids are very effective and efficient at relieving airway obstruction, they have limited residual effect after treatment stops and long‐term administration is usually limited due to the risk of laminitis, immunosuppression, and interactions with endocrine metabolism9. The drug withdrawal period also impacts the racing schedule. So, what treatments can be used which interfere less with their training and racing plan?

Firstly, creating a barrier between the horse’s airways and the pollen with Nostrilvet or similar and/or the use of a nose-net are low-cost options for training that could be worth a try. This could help to reduce the irritant load on non-race days.

If the horse is truly allergic to certain pollens, then de-sensitisation injections can be used with no withdrawl period necessary. Known as allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) it is a safe long-term treatment which has been used successfully for allergen-induced Equine Asthma. The efficacy of the treatment can vary however, studies suggest that approximately 75% of cases treated showed a good response, with either no need or a reduced need for steroids.

Immunotherapy aims to make the horse tolerant to the environmental allergens that have been diagnosed as responsible for their clinical signs by introducing increasing amounts of the allergen to which they are sensitive. These desensitisation vaccines are administered to the horse subcutaneously. The initial treatment lasts for approximately 10 months, with a dosage regime that gradually increases until the maximum tolerated dose is reached. This is then followed by maintenance treatment. The length of time for a response has been reported to vary between individual horses and can be anywhere from 4 and 12 months. Treatment can be ongoing as premature discontinuation may result in the clinical signs recurring.

Developments in orthobiologics has brought a new non-corticosteroid anti-inflammatory alternative for use in affected horses. Alpha-2-macroglobulin (α2M) is a naturally occurring protein within the blood and is the horses natural defence against inflammation. Plasma proteins are filtered from the horse’s own blood, leaving an isolated, concentrated alpha-2-macroglobulin product which can be nebulised using a Flexineb. It’s high-priced and still early days for this product but offers a potential drug-free way to treat. It is also an effective anti-inflammatory in joint disease.

Principally the greatest threat to respiratory health year-round is from environmental sources which you can control – the forage, the bedding and the overall stable hygiene environment, this should never be overlooked.

References

Couetil L, Cardwell J, Garber V, et al. Inflammatory airway disease of horses— Revised consensus statement. J Vet Intern Med 2016;30:503-515

White S, Moore-Colyer M, Marti E, Coüetil L, Hannant D, Richard EA, Alcocer M. Development of a comprehensive protein microarray for immunoglobulin E profiling in horses with severe asthma. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Sep;33(5):2327-2335. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15564. Epub 2019 Aug 20. PMID: 31429513; PMCID: PMC6766494.

Soutar A, Harker C, Seaton A, Brooke M, Marr I. Oilseed rape and seasonal symptoms: epidemiological and environmental studies. Thorax. 1994 Apr;49(4):352-6. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.4.352. PMID: 8202906; PMCID: PMC475369.

Dauvillier J, Ter Woort F, van Erck-Westergren E. Fungi in respiratory samples of horses with inflammatory airway disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Mar;33(2):968-975. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15397. Epub 2018 Dec 21. PMID: 30576012; PMCID: PMC6430897.

Gov.uk website - Accredited official statistics Cereal and oilseed areas in England at 1 June 2024. Updated 29 August 2024 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/cereal-and-oilseed-rape-areas-in-england/cereal-and-oilseed-rape-areas-in-england-at-1-june-2023#:~:text=1.7%20Oilseed%20crops,244%20thousand%20hectares%20in%202024.

Teagasc Crop Report www.teagasccropreport.ie Harvest report 2024. https://teagasccropreport.ie/reports/harvest-report-2024#:~:text=The%20area%20of%20winter%20oilseed,of%2021%2C600%20ha%20in%202023.

Lavoie J, Bullone M, Rodrigues N, et al. Effect of different doses of inhaled ciclesonide on lung function, clinical signs related to airflow limitation and serum cortisol levels in horses with experimentally induced mild to severe airway obstruction. Equine Vet J 2019;51:779-786.

Ciclesonide [prescribing information] Duluth, GA: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc. 2020.

Mainguy-Seers S, Lavoie JP. Glucocorticoid treatment in horses with asthma: A narrative review. J Vet Intern Med. 2021 Jul;35(4):2045-2057. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16189. Epub 2021 Jun 3. PMID: 34085342; PMCID: PMC8295667.

Alpha-2 Macroglobulin for the Management of Equine Asthma Summary Results of a Pilot Study Dan Dreyfuss, DVM

Addressing drug resistance in equine tapeworms

Article by Jacqui Matthews

Tapeworms are important parasites of horses

All horses can be infected with internal parasitic worms, which can cause health issues, including weight loss, diarrhoea, and colic. The most common worms affecting racehorses, and other horses, are the small strongyles (cyathostomins) and the common equine tapeworm, Anoplocephala perfoliata. Horses are infected by ingesting parasites from contaminated grazing, whether it be a field, turn-out paddock or opportunistic grazing on training grounds or racetracks.

Recent reports of dewormer resistance in A. perfoliata are very concerning, especially as there are few available products to treat these parasites and no new drugs are expected to enter the market soon. These relatively large parasites typically reside at the junction of the small and large intestines and can cause colic. The worms attach in clusters to the intestinal wall, which can cause mechanical obstruction and mucosal damage.

Blockages can cause impaction, potentially necessitating surgery. Moreover, the presence of tapeworms may lead to intussusception, where one segment of the intestine telescopes into an adjacent segment, also requiring surgery. Studies indicate that having as little as 20 tapeworms can cause significant damage to the intestinal wall (Pavone et al. 2010). Therefore, it is crucial to prevent such burdens from accumulating in horses.

Tapeworm resistance to deworming products

There are two types of dewormers (anthelmintics) available for treating tapeworms: praziquantel and pyrantel (given at double the dose used for treating roundworms). In the UK and EU, there have been several anecdotal reports of reduced effectiveness of anti-tapeworm drugs. A recent research study on a Thoroughbred farm in the US evaluated the performance of both tapeworm dewormers (Nielsen, 2023).

The results demonstrated treatment failures in foals and broodmares in which tapeworms survived treatment. This was the first formal report of suspected drug resistance in tapeworms. Resistance occurs when parasites survive deworming treatments and pass on reduced sensitivity to the drugs to subsequent generations. Repeated treatments with the same drug can lead to parasite burdens that cannot be cleared and may result in clinical disease.

Given the threat of resistance in this species, it is essential to reduce the overuse of anti-tapeworm medications. Implementing more sustainable control methods is now crucial for the long-term effectiveness of these important dewormers. These control methods must include:

maintaining a clean grazing environment

regularly monitoring parasite burdens

deworming only those horses that truly need treatment.

Use grazing management methods to reduce reliance on dewormers

Tapeworms differ from other common equine worms because they develop inside mite intermediate hosts on paddocks (Fig. 1). Horses become infected when they consume hay or grass that contains tapeworm-infected mites. Mites are infected by eating eggs passed in the dung of infected horses. Where horses have access to grazing paddocks, it is essential to remove dung daily and dispose of it well away from both the grazing area and any water sources. Extra caution should be taken with horses that have grazed away from the yard and newcomers to the yard (see quarantine recommendations below).

Use tests to reduce dewormer treatment frequency

Regular testing is essential for effectively managing tapeworm infections. Faecal egg count (FEC) tests are unsuitable for detecting tapeworms. These detect worm eggs shed in dung, but are not reliable indicators of the overall parasite burden in individuals, particularly since immature worms are not detected. FEC methods are also influenced by the variable release of egg-containing segments from adult tapeworms.

The main purpose of FEC tests in tapeworm control is to assess the effectiveness of deworming treatments. If tapeworm eggs are detected in dung samples taken two weeks after treatment, this is a significant finding. However, the absence of eggs in a FEC does not mean that tapeworms are not present. If resistance is suspected, this should be discussed with a veterinary surgeon.

Tests that measure antibodies to tapeworm provide valuable information about levels of infection and should be used to guide treatment decisions. Antibody tests are available in blood and saliva formats. In the blood test, samples are collected by a veterinary surgeon and sent to the laboratory for analysis.

This test measures levels of tapeworm-specific antibodies in the blood, with results reported back to the veterinary surgeon as "serum scores." These scores are categorised as low, borderline, or moderate/high, and treatment is recommended for horses with results in the borderline or moderate/high categories. The non-invasive saliva test involves taking a sample from the horse’s mouth using a specially developed swab (Fig. 3) and does not require a veterinary surgeon.

The swab containing the saliva sample is mailed to the laboratory in a preservative solution, ensuring stability for at least three weeks. At the laboratory, the saliva sample is assessed using a special three-ELISA system that accurately measures tapeworm-specific antibodies, with the results reported as “saliva scores”. Similar to the blood test, the saliva test categorises results as low, borderline, or moderate/high, with treatment recommended for horses that have results in the second two categories. Because antibodies take time to decrease after effective treatment, horses should not be tested again until 4 months after the last deworming for blood tests or 3 months for saliva tests.

By reliably detecting tapeworm burdens, antibody tests enable treatments to be targeted to only those horses that need treating and therefore reduce the risk of dewormer resistance. Results from tapeworm testing have led to significant reductions in the use of dewormers; from 2015 to 2022, over 164,000 horses in the UK were assessed using the saliva test, with only one-third recommended for treatment (Matthews et al. 2024).

Applying tapeworm testing at racing yards

Tapeworm testing frequency can be determined by conducting a risk assessment. Key risk factors include age and access to contaminated grass, as well as historical test results. These parasites can be long-lived and persist for extended periods, so it is essential to consider each horse’s history during or before training.

While most horses in training are at low risk due to having limited pasture access, yearlings and two-year-olds may have higher burdens, especially if from breeding farms or other premises where there is a high level of infection. However, all ages of horses are susceptible to tapeworms. Regular assessments with a veterinary surgeon will also identify risk factors in yard management practices, including those associated with activities like short daily turnouts. A comprehensive risk assessment will:

1. Identify which tests to perform (FEC tests, small redworm blood tests, tapeworm tests) and the frequency of testing

2. Highlight the need for treatments for high-risk horses when tests do not provide information for treatment decisions

3. Provide information on worm exposure and ways to minimise infection risks.

If significant risks are detected, such as a high level of tapeworm infection indicated by testing or the frequent introduction of new horses, testing should occur every six months. Once a year testing may be appropriate in low-risk situations where previous testing has shown low evidence of tapeworm infection.

Testing identifies infected horses that could spread infection to others, allowing for prompt treatment and reducing the risk of colic. If many horses test positive, it is crucial to identify the source of infection and improve management practices to reduce spread. In a recent case study on a UK training yard, 56 horses were tested for tapeworm antibodies.

The results revealed that only 14% of the horses had tapeworm burdens that required treatment. These horses were turned out in a small paddock for just 30 minutes each day, and because dung was not removed from the area, the paddock was identified as a source of infection. The trainer was advised to remove the dung from the paddock daily and to treat any horses that tested positive for tapeworms.

This testing protocol not only helped reduce the overall deworming frequency, but also provided the trainer with valuable information about horses at risk of colic. It also highlighted potential areas for improving parasite management practices.

Avoiding the introduction of new or resistant worms

Introducing new horses to racing yards requires proper assessment to determine if they have roundworm (small redworm, ascarid) or tapeworm infections. The traditional method of treating all newcomers with a broad-spectrum dewormer is outdated and should be avoided due to increasing drug resistance in all common parasites. Instead, it is recommended to assess new horses using appropriate tests, specifically;

FEC tests to identify if they are shedding eggs such as small redworm and ascarid eggs

Blood tests to detect small redworm stages that may not be detected using FEC tests

Tapeworm tests to identify horses that need specific treatment for this parasite.

If any of these tests return positive results, the appropriate dewormer can be selected to target the parasites present. Furthermore, if a horse tests positive in the initial FEC test, it is advisable to conduct a follow-up FEC test two weeks after treatment to determine whether the dewormer has been effective.

In conclusion

Every horse will encounter parasitic worms at some point in their life, making effective parasite control essential for their health and well-being. While traditional all-group dewormer treatments have been common, rising cases of dewormer resistance reveal that this approach is no longer sustainable, especially as no new anti-tapeworm treatments are expected soon.

Using tapeworm tests to determine if treatment is needed is crucial to maintain the effectiveness of existing dewormers. Many horses in low-risk environments have minimal or no tapeworm infections, making regular treatments unnecessary. Testing helps identify only those horses that truly need treatment, thus promoting the longer-term efficacy of dewormers.

In the racing industry, there is significant overuse of dewormers, with few trainers using evidence-based practices. It is essential that the spread of resistant worms is prevented, especially as racehorses move to various environments (breeding farms, sport horse yards, sanctuaries, leisure horse premises) where more vulnerable horses may reside. For this reason, the industry must adopt management-based and test-led methods to control worm populations effectively.

References

Matthews et al. 2024. In Practice 46:34-41.

Nielsen. 2023. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 22, 96-101.

Pavone et al. 2010. Vet. Res. Commun. 34, S53-6.

Exercise associated sudden death - improvements to equine safety and welfare to reduce incidences

Article by Celia Marr

In racehorses, exercise-associated sudden death – or EASD – is a very rare event but, the miserable events at Cheltenham last November where three horses died on the same day, drew considerable negative attention to the condition and highlight a need for better understanding of why it happens as well as motivating vets, researchers and horsemen to do more to prevent it.

Cheltenham drew a spotlight to the problem but EASD was already the focus of international effort: in June 2024, Woodbine Racecourse, Toronto hosted the International Horseracing Federation’s (IFHA) Global Summit on Equine Safety and Technology where EASD was one of two major workshop topics. This international event was sponsored by Cornell University’s Harry M. Zweig Memorial Fund for Equine Research, The Hong Kong Jockey Club Equine Welfare Research Foundation, and Woodbine Entertainment Group and specialist veterinary clinicians, pathologists and researchers spent two days sharing knowledge and ideas and debating how tangible improvements to equine safety and welfare in racing could be made towards reducing the prevalence of both EASD incidents and severe musculoskeletal conditions.

What is EASD?

The term EASD is used to describe a fatal collapse in a previously healthy horse either during or shortly after exercise. Currently, across the world, different time-windows are used by regulators which makes quantification of the problem challenging. A benchmark definition is needed so that the occurrence rates can be audited and the EASD workshop team advised that an international definition is adopted to define EASD as within approximately one hour after exercise. Figures from the BHA show that in the UK, the 2024 EASD incident rate was 0.04% or 4 horses per 10,000 starts – which with just under 90,000 runners translates to 36 EASD losses for the year which is why the triple Cheltenham deaths were so extraordinary. The UK’s rate is comparable with other nations such as Australia and a little lower than the USA although the different definitions used in different racing jurisdictions make direct comparisons challenging.

Four broad EASD categories

The most authoritative international study looking at causes of EASD was performed with the Horserace Betting Levy Board supported by a group in the University of Edinburgh’s Royal Dick School of Veterinary Studies. This report showed that determination of cause of death is significantly impacted by individual pathologist’s interpretation of findings, however, in broad terms about a quarter of cases EASD have a clear and definitive diagnosis of cardiopulmonary failure and a further 10-15% have necropsy findings which are strongly suspicious of cardiac or pulmonary failure; around 10% of EASD cases are due haemorrhagic shock brought on by rupture of a major blood vessel which is most commonly within the abdomen, while unfortunately around 20% of cases are unexplained despite detailed examination. A range of other rare conditions including brain and spinal problems, often relating to trauma, account for the remainder.

Within the cardiopulmonary failure category, it is generally accepted that the majority relate to cardiac arrest. This means that the cardiac rhythm is disrupted but, in fact it is actually very difficult to prove that a cardiac rhythm disturbance has been the trigger mechanism of death during a post-mortem examination. In the June 2024 IFHA summit, a significant amount of the workshop was dedicated to discussing current knowledge of cardiac rhythm disturbances, why they occur and how they might be detected in future.

Cardiac arrest: a “perfect storm”

Cardiac arrest can be likened to a perfect storm where multiple adverse factors combine with devastating impact. Unlike catastrophic bone fractures or tendon injuries, cardiac arrest does not necessarily relate to an accumulating pathway of built-up microdamage and because of this, it is very difficult to predict cardiac arrest might occur. For a cardiac rhythm disturbance (aka an arrhythmia) to develop three elements are required: a substrate, triggers and, in some cases, one or more modulators. A substrate refers to the structure of the heart, this can be an area of scar tissue but the heart structure does not necessarily need to be pathological and the changes in muscle content which arise as a result of athletic training may also be a substrate.

A trigger reflects a change in the cellular and tissue environment such as alteration in concentrations of different electrolytes or development of low oxygen concentrations in the tissues yet changes in electrolytes and lowering oxygen concentrations occur every time a horse gallops. Modulators are an electrophysiological characteristic of the heart which might be a permanent feature of an individual’s cell make-up or more often might be a transient state such as a variation in the nervous system brought on by excitement, stress or perhaps pain.

The key point is all these independent factors have to combine to precipitate a cardiac arrest – indeed a horse might go through its life uneventfully despite the presence of a particular substrate or it may experience these triggers on a daily basis and come to no harm. It is the coalescing of multiple factors at a given moment that precipitates the rhythm disturbance that leads to cardiac arrest.

EASD at the molecular level

Arguably the biggest challenge we currently face in this arena is lack of knowledge of what is normal in the exercising horse. There is very little understanding of structural and electrical remodelling of the equine heart in response to exercise. We do know that the heart, just like any other muscle, will increase in size in response to training and we also know that in horses competing over longer distances such as steeplechasers, a big heart confers an athletic advantage. Exercise training can also lead to scar-tissue formation but in both human and equine athletes the importance of this pathology is uncertain. There is some evidence that fit horses also have altered cardiac electrical characteristics but again, knowledge in this field is very sparse.

Electrical activity in the heart muscle cells is controlled by ion channels – these are proteins that are sited within the cell membranes which effectively act as gates opening and closing to allow electrolytes such as sodium, potassium and calcium to move in and out of the cell and in doing so the electrolytes carry the electrical current.

Channelopathies – or abnormalities in these ion channels - have an important role in the development of rhythm disturbances but right now, research on equine ion channels has been limited…but that is changing rapidly. Researchers in Surrey, Copenhagen and various US universities are working to understand equine channels and the genetic and acquired factors that determine how they function. As knowledge accumulates it may be possible to include tests for the molecular make -up of an affected individual in post-mortem exams – the so-called “molecular autopsy” which is improving diagnosis rates in human cardiac arrest suffers.

So far equine studies have not found conclusive evidence of genetic mutations associated with EASD. But there is evidence for heritability in the Thoroughbred: observations from Australia which have shown some stallions’ and at least one mare’s progeny have higher rates of EASD associations suggesting that it is likely that there are genetic elements at play in EASD. One of the key recommendations of the IFHA’s EASD workshop was that tissues from both horses impacted by EASD and those dying of other causes should be banked and shared amongst researchers to underpin and promote research studies in this area.

ECG is the cornerstone of arrhythmia diagnosis

Currently vets rely on resting and exercising electrocardiograms (ECG’s) to identify horses with arrhythmias. However, there are a number of limitations to using ECG as a screening and diagnostic tool:

ECGs can be technically difficult to perform during exercise as they are affected by motion artefact; leading to reduced quality of the trace.

ECGs currently must be manually interpreted, which is time consuming and leads to significant intra- and inter-observer variability.

There are no universal guidelines on how to perform the ECG; i.e. exactly where to place the electrodes, which affects the trace produced.

There is no consensus on interpretation of the results of an ECG examination in terms of the clinical significance of any abnormalities detected and whether the clinical presentation impacts criteria for interpretation. Indeed, we need to understand more about what is ‘normal’, before we can identify horses with an ‘abnormal’ trace.

Will wearables change the diagnostic landscape?

Over recent years, increasingly racehorse trainers have been using wearable devices during routine training. Generally, the trainer’s motivation is to collect data on speed and fitness variables in their horses to refine their training programmes but several of these devices also have the capacity to include an ECG trace. The ECG can then be accessed if the horse has a problem during a training session and, usefully, the horse’s past record can also often be interrogated. The large numbers of recordings that are currently being made represents an untapped resource for collecting ECG information from large numbers of horses to better understand cardiac responses during exercise in both healthy and unhealthy individuals.