Who should be dictating the Rules of Racing - the racing industry or government?

Article by Lissa Oliver

Regular readers of this publication will already be well aware of racing’s social licence and the efforts required to ensure the sport’s popularity with the public and, essentially, the wellbeing of our participants. EU legislation is increasing in strength in addressing equine welfare in general, but in Germany in particular, laws coming down from the government are impacting many racing yards.

The law introduced last year regarding minimum paddock time for all horses is one such notable problem. As Belgian trainer Guy Heymans points out, “Turnout for horses every day is not the same as the requirement for horses to remain in paddocks. If I understand correctly, the demand is not just turnout; they mean that the horses are in a paddock for a certain period of time every day. It’s OK for me, but a trainer with 20 horses or plus in training will probably not have enough paddocks, and it is difficult to keep such a horse in shape. Of course it is a plus for horses to spend a short time in the paddock, but when they demand horses stay permanently in paddocks, it is impossible to bring a horse to top form.”

Not every trainer may agree with that, and some have enjoyed great success ‘training from the field’, but it is a matter of personal choice and methods, as well as having the luxury of such choice. It isn’t so much about making our own decisions on equine welfare in particular, which we would all prefer to embrace as much as we can; but it’s more about the practical ability to do so and the apparent gulf between those setting the rules, and now laws, and those who have to apply them in daily practise.

“There are some countries lagging a bit behind in welfare, and I would be happy to see more legislation coming in,” says Irish trainer Amanda Mooney. “We just have to learn to adapt and work with it. Sweden has a very high standard of welfare and a very good aftercare service. Horses aren’t just sold on and rehomed; they’re put out on loan—the same as the Godolphin Lifetime Care programme. I think more could be done for aftercare.”

Germany has the strictest animal welfare legislation worldwide and is the only country in the EU to have integrated animal welfare into its constitution. German law could be the crystal ball into the rest of European racing’s future. In 2018, horses were no longer allowed to run in a tongue-tie, as a result of animal welfare concerns. Rüdiger Schmanns, director of racing for German Racing, said at the time, "In all other equestrian sports in Germany the use of tongue-ties is banned—racing was the last equine sport which allowed tongue-ties. With growing animal welfare activities, especially in Germany, there was no possibility of allowing the use of tongue-ties to continue."

This year, stricter whip rules were adopted; and any jockey who uses the whip six times in a German horse race could expect an 84-day ban under the new penalty system. The number of strokes of the whip allowed per race has been cut from five down to three, and the length of bans for going more than one over the limit can now be measured in weeks and months, rather than days.

“This looks extreme but will hopefully not occur,” said Rüdiger Schmanns. “The animal health pressure is high in Germany. We would like to have harmonised rules regarding the whip at least in the whole of Europe, but that seems to be a long way off as the differences in England and Ireland compared to France and Germany are still quite big.”

At least those rules are coming down from racing’s governing bodies, assisted by Boards of selected professionals representing all industry stakeholders. In theory, the Rules of Racing should be a suitable compromise agreed by all for the betterment and progression of the sport. But what happens when Rule changes have not involved industry stakeholders? When changes come from government level they may not always be the desired result of consultation with racing’s professionals.

The Rules of Racing have historically been set down by industry participants to govern the sport in a fair manner. The earliest known example is quite literally set in stone and dates to the earliest part of the first century, some 2,000 years old. Professor Hasan Bahar’s 2016 discovery at an ancient Roman racecourse in Turkey—the oldest existing tablet describing the rules of horseracing—illustrates a keen sense of fairness in the sport. Prof. Bahar points out, “It says that if a horse comes in first place in a race, it cannot participate in other races.” A winning owner was also forbidden from entering any other horses into an event’s subsequent races, presumably to give others a chance at glory, Prof Bahar suggests. “This was a beautiful rule, showing that races back then were based on gentlemanly conduct.”

It also highlights the origins of the sport’s governance, replicated in Britain by the next earliest-known Rules of Racing set by The Jockey Club in 1750. The Rules were dictated by racehorse owners to preserve and progress their racing and breeding interests. Even prior to a rule book, in 1664, it was King Charles II who personally wrote The Rules of the Newmarket Town Plate. According to Whyte's History of the English Turf (1840), King Henry VIII passed a number of laws relating to the breeding of horses. Racing was a self-governing institution, more to the point, one governed by racehorse owners.

Nevertheless, governments haven’t always been keen for that arrangement to continue. The British Jockey Club was formed in 1750, specifically to create and apply the Rules of Racing in the wake of a decade of Parliamentary opposition to the sport. There are few racing nations left where the original governance of a Turf Club or Jockey Club hasn’t transitioned into a State-funded corporate body.

Parliamentary opposition to the growth of horse racing in the 1740s focused on the damaging effect of gambling. Three hundred years on, no other sport has entangled itself so constrictively with gambling. Racing’s economy is no longer based on the revenue of racehorse owners, and the sport is answerable to the holders of the purse strings.

While researching a quote from former Member of Parliament Sir Clement Freud, who claimed that “horse racing is organised purely to generate taxes,” the transcript of an interesting House of Lords debate surfaced. Though dated February 1976, the facts, figures, and sentiments quoted could as easily place it in 2023, which makes for a sorry commentary on British racing.

The establishment of a Royal Commission on Gambling led to Sir Clement Freud remarking on the “large number of otherwise non-viable racecourses kept open to ensure sufficient races being run, even as the financial rewards to the owners and trainers declined to the point where most could barely cover their expenses.”

During the House of Lords’ debate on the matter, Lord Newall observed, “The income from betting is believed to reach the optimum level with two meetings every day with staggered starting times. After this, the same money apparently chases after more horses.” And perhaps initiating an argument that continues to this day, Lord Gisborough pointed out, “There has been, and often is, criticism of the value of the Pattern race prizes, but these few races at the top of the pyramid of racing are the necessary incentives to encourage breeding of the best animals, the very capital of the industry. It would not help racing in the long run if the value of the Pattern prizes were to be spread over the rest of racing. They provide the vital opportunity for the best horses of the world to be matched together, without which the best British horses would have to race more abroad to prove their value for breeding purposes.”

Perhaps we digress here, but the relevant points of 40 years ago, 300 years ago and, indeed, 2,000 years ago are summed up by The Lord Trevethin Oaksey, who explained, “What you need is honourable, fair-minded, unbiased men who are answerable to nobody but themselves, and who have as much experience as possible of the problems involved.”

And therein lies the modern problem, with racing dependent upon gambling revenue and accountable to the betting operators and the taxpayer. Self-governance is fast becoming a thing of the past, but the bigger problem is being given the necessary time and finances to adapt.

In our 2021 winter issue, German trainer Dominik Moser warned, “We have so many new rules and many more rules being introduced for next year. All horses must spend a number of hours out in the paddock each day, and they must be assessed by a vet before going into training. I have paddocks for my horses, but I don’t currently have enough for all of them to be out every day, so I have to build more paddocks. My aim is that all of my horses will be able to go out from after they have finished training at 1pm until the evening. The training centres, such as Cologne, will have a big problem, because there is not enough space for the number of paddocks needed.

“These rules are coming directly from government, not from Deutscher Galopp. I like that we think more about the horses; we have recently been thinking more about the people, the jockeys and staff. The horse had stopped being our number one concern. This is the right way, but the rule is not easy to adapt to; we haven’t been given time to prepare.”

Christian von der Recke agrees wholeheartedly with the reasoning behind the legislation and tells us, “From day one, our horses go to the paddock; and I am sure that is part of the success. They enjoy more variety and have less stomach ulcers. More exercise is the key to success.” However, von der Recke has a large private facility at his disposal, with ample paddock space, denied to those trainers based at training centres.

One such centre is Newmarket, where John Berry reasons, “It's clearly preferable to turn one's horses out for part of the day rather than have them confined in their boxes for 23 hours a day or more; but some people prefer not to do so, often because of not having either the time nor the space to do so. Just common sense says it's better for them mentally, and physically too; but each to his own.

“I'd actually regard not gelding horses as a far bigger concern as regards horses' mental well-being than lack of freedom, but that's by the by. Obviously, some colts have to remain colts to ensure the survival of the species, but only a tiny percentage are required for stud duties; and keeping the others as colts rather than gelding them is just nuts. Sexual frustration must be at least as great a cause of anguish for horses as frustration at lack of liberty.

“I'd have thought if a government wanted to do something to increase the sum of equine happiness, addressing this issue might be more appropriate, but obviously it would be hard to frame the laws satisfactorily.

“Obviously in utopia every horse would have access to freedom and to companionship (although the latter isn't always a good idea with colts), but life isn't utopian. Similarly, it would clearly be a good idea if every dog could have a life where he can have a run off the lead every day, every school would have good sports facilities, and every community would have good recreation and leisure facilities. But we can't even manage to achieve that with humans, so I'd be surprised if the government thought that this was a worthwhile way to direct its energies.”

British government’s current distraction is reforming gambling legislation, which is creating anxiety and even panic among the racing community. Once again, it’s social licence and a need to enforce ‘protection’ that attracts government attention, with affordability checks upsetting punters and threatening horse racing's revenue.

In Ireland, that same focus is the driving force behind the Gambling Regulation Bill, which proposes a ban on televised gambling advertising between 5.30am and 9pm, which of course affects a large portion of advertising on live horse racing coverage. As a result, Racing TV and Sky Sports Racing have threatened to pull their racing coverage in Ireland, stating that their service will become "economically unviable.”

This no longer comes down to welfare or integrity within the sport. Do we protect the vulnerable or protect our own interests, even in the knowledge our interests conflict? We may try to excuse our decision, but further down the line, as more attention is put on the sport, will we really be able to defend our corner?

Ryan McElligott, CEO Irish Racehorse Trainers Association, announced in reaction to the bill, "If Racing TV determined it was no longer viable to broadcast in Ireland, then Irish racing disappears off our screens. That would be detrimental to the whole industry.

"There are plenty of owners who don't get to go racing as much as they would like, but it's very easy to watch their horses run should they not make it. If you take that away, I think that would put a huge dent in the sport's appeal and also demand from an owner's point of view. It would put us at a huge disadvantage when compared to other jurisdictions.

"We're talking about subscription channels, and it is a requirement that you are over the age of 18 to buy a subscription to a package like Racing TV. These dedicated racing channels exist behind a paywall, so there is already a safeguard there.

“Every facet of the industry is wholly supportive of gambling regulation which protects vulnerable people. This is not a deliberate move to damage the sport; this would be an unintended consequence. It is hugely concerning for the industry."

In Britain, owners have already very publicly left the game as a result of the Gambling Act Review White Paper financial risk checks. All betting operators have a social responsibility to create a safe environment, and how much money a client can afford to spend on gambling is a key part of the safe environment.

Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, Lucy Frazer KC, described the White Paper as “consumer freedom and choice on the one hand, and protection from harm on the other” while stating in the House of Commons in April: “With the advent of the smartphone, gambling has been transformed: it is positively unrecognisable today, in 2023, from when the Gambling Act was introduced in 2005. Temptation to gamble is now everywhere in society, and while the overwhelming majority is done safely and within people’s means, for some, the ever-present temptation can lead them to a dangerous path. When gambling becomes addiction, it can wreck lives: shattered families; lost jobs; foreclosed homes; jail time; suicide. These are all the most extreme scenarios, but it is important to acknowledge that, for some families, those worst fears for their loved ones have materialised. Today we are bringing our pre-smartphone regulations into the present day with a gambling White Paper for the digital age.”

More and more, we can expect legislation to encroach on the racing industry and force us to face moral dilemmas. Racing jurisdictions are doing their best to be seen by the public to be doing their best for equine welfare. Currently, Ireland has a very basic 28-page “Our Industry, Our Standards” guide to equine welfare; France has a very comprehensive 139-page “Charter for Equine Welfare,” based upon the official EU Paper; Germany has a 44-page “Animal Welfare in Equestrian Sport Guideline”; and Britain has “A Life Well Lived,”—a 130-page welfare strategy. Sweden, renowned throughout other racing nations for its top-class welfare, relies on a website to provide current guidelines and information.

The EU Discussion Paper on Equine Care, adopted so well by France Galop in its charter, has multiple language versions and informative images, making it a simple solution for those countries lagging behind. It is also of visual appeal to those outside of the sport seeking reassurance. We may not consider them to be relevant, but they are proving to be the most important players in rulemaking.

Shared ownership

It has always struck me—as someone with a keen interest in most sports—that the lack of harmonisation around various rules and issues such as interference, jockey’s weights, and doping isn’t helpful as racing remains such a puzzle to most of the world.

This is evident too in the area of shared ownership, of syndicates, racing clubs and the developing area of micro share groups.

Never has it been more important for racing to attract fresh blood, with its core support ageing and the sport barely causing a ripple in mainstream media. Shared ownership is a foolproof mechanism for unearthing new acolytes because emotion and feeling will trump catchy slogans or slick promotional videos every time. If you want converts, having them in the parade ring as part of the inner circle and seeing their horse run and contend or win is your best bet.

Piers Winkworth, racing manager of Kennet Valley Thoroughbreds, summed it up well after Dragon Leader maintained his 100 per cent record from three runs by landing the £147,540 first prize in the Goffs UK Harry Beeby Premier Yearling Stakes at York’s prestigious Ebor meeting in August.

Dragon Leader with Ryan Moore up wins the 2023 Premier Yearling Stakes at York’s prestigious Ebor meeting in August.

“This is what syndicates are all about really—having cracks at these ultra-valuable sales handicaps with modestly bought horses,” Winkworth noted. “Dragon Leader, a £45,000 Donny yearling, goes and wins the big race by some distance under Ryan Moore. It was thrilling for all of our owners. We had about 16 people up at York to see him, and there were great celebrations after the race”.

Johnny Murtagh has participated in many such celebrations, having had a hefty number of syndicates at Fox Covert Stables since he took out a licence to train at the conclusion of a stellar riding career.

The Curragh-based conditioner secured his first Gp. 1 triumph with Fitzwilliam Racing’s Champers Elysees in 2020, and bagged his first Classic the following season when Sonnyboyliston swooped to score in the Comer Group International Irish St Leger for Kildare Racing Club.

This season, Murtagh has had runners for 11 syndicates, saddling winners for six of them. So enamoured is he with shared ownership that he has just launched a new racing club, Racing Revolution, more of which anon.

“There’s nothing better than coming back into the ring and seeing people who never thought they’d ever own a horse so happy”, reports Murtagh.

“We’ve been very lucky with Fitzwilliam. They ended up winning a G.p 1. We now have the likes of the Brunabonne Syndicate—lads from where I grew up. They’ve been so lucky with Mashhoor. He won a couple of big races (including at Gp. 3 level), brought the lads to York and Ascot, and ran on all the big days”.

The idea of the racing club came out of Mashhoor’s Listed triumph on Tattersalls Irish 2000 Guineas day at Curragh Racecourse in May. In particular, it was the reaction of Tommy Dowd, a celebrated former Gaelic footballer who led Meath to All-Ireland glory in 1996, that resonated.

“Tommy Dowd picked up the Sam Maguire as captain of Meath and he said, ‘This is the same feeling as that.’”

Dr Paull Khan, secretary-general of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation summarises the overall situation brilliantly.

“In many countries (in and outside our region), racing is struggling to maintain its popularity and relevance, as societal practices and preferences shift,” notes Khan.

“Broadening the base of racehorse ownership may well prove a key weapon in countering this trend. Quite simply, the more people that have an involvement in owning a racehorse, the more our sport becomes embedded in society.

“For racing authorities, the challenge is not limited to promotion. Appropriate Rules of Racing must underpin such activity, which allow for and define co-ownership options.

“But there is also a potential downside, in that the creation of ownership entities which encompass large groups of individuals brings with it increased risks of incompetent or, yet worse, fraudulent management. Any examples of people suffering bad experiences, which are not satisfactorily dealt with, are likely to gain much publicity and have the effect of putting off future owners. So the final aspect to which racing authorities must give thought is the need for effective regulatory oversight, to minimise this risk”.

What follows is something of a potted overview of the situation in Europe, thanks to a number of different stakeholders from governing bodies to trainers and plenty more in between.

BRITAIN

Establishing a new syndicate isn’t laborious in Britain, and only the manager/syndicator must register as an owner. The members do not have to register, but an updated list of members must be provided to the BHA as well as the percentage share held by each one.

Racing clubs are focussed entirely on the experience of ownership but without having any equity in the horse or share in whatever proceeds it accrues while racing. Members pay an annual fee to enjoy most of the other benefits of ownership, on race day and while in training. Once again, only the person setting up or running the club must register.

Micro share groups are becoming more visible and are a very cheap way to become involved in racing as a tiny percentage of a share, normally a fraction of 1 percent , can be acquired for as little as £40. Like racing clubs, they are primarily experiential, though members are owners and are entitled to the equivalent cut of any money accumulated.

All forms of shared ownership in Britain are subject to a code of conduct that includes specific mandatory clauses in each written contract. Transparency and protection are the key tenets of the code. The BHA has committed to auditing a proportion of syndicate/racing club/micro share contracts to ensure compliance.

George Baker’s ‘Have horse, will travel,’ mantra has always made him attractive to shared ownership groups. The Robins Farm trainer has saddled winners all over the world and is as good a host as he is a trainer.

The Surrey-based conditioner has his own racing club, the George Baker Racing Club, which provides all the perks of an involvement in racehorses, including open house visits, parade ring passes, regular communication, picnics at Royal Ascot and Glorious Goodwood, and even a share in a prize money.

Baker joins Andrew Balding and Harry Eustace as trainers for the MyRacehorse fractional share group, making a big splash on this side of the Atlantic and having initially enjoyed stupendous success when established in America by Michael Behrens.

The relationship with MyRacehorse began with Get It and Watchya racing in Bahrain; and the ambition was rewarded by the former being awarded a victory after the winner on the day was disqualified due to a positive sample.

“The key point here is making racehorse ownership accessible to absolutely everybody in the way that it has been for a few years now and obviously in Australia, where the big syndicates have had massive success”, Baker declares.

“Like our horse (Get It) at Wolverhampton (on September 7) that won the Racing League race—a share in him was £45. The wonderful thing about a share at whatever level [is] the horse becomes your horse, regardless of whether you’ve paid a million pounds or forty pounds.

“We all know it’s the way forward because we’ve just got to get as many people as we can into this game, and of course you hope that some of them become more heavily involved in the sport and that it evolves to a longer association; but the most important thing is showing racing as a viable means of enjoyment”.

A degree of suspicion has lingered around micro share operations, but Baker is happy to go to bat for MyRacehorse.

“I can’t speak for any of the other micro share entities, though obviously I’ve heard rumours of numbers not quite stacking up or that horses worth ‘x’ have been marketed for ‘x + y + z’; but that’s not something I can be quoted on because I haven’t had intimate involvement or knowledge.

“I know from the MyRacehorse perspective, they are wholly transparent and very keen to be treated as you would treat a security in the stock market. They want to create a secondary market so people can trade in and out of their shares.

“People demand absolute transparency and absolute integrity and from my experience, clearly that’s what MyRacehorse have based their brilliant business on in America and Australia; and they’re trying to bring the same criteria here. And that’s absolutely correct. I don’t want to be involved with any organisation or micro share entity where there’s a level of suspicion around the numbers. And that’s why MyRacehorse is creating a niche and an attractive market”.

Baker returns to Get It and Wolverhampton to ram home his point about the impact feeling a winner can have regardless of financial outlay.

“There was one of the guys in the winner’s enclosure who’d won a share that night in a race card competition that MyRacehorse had organised with the Racing League. And there he is in the winner’s enclosure being photographed with (jockey) Paul Mulrennan and the horse. The guy was almost in a state of shock, but he was absolutely loving it”.

IRELAND

Ireland is among the most proactive European jurisdictions for the promotion and growth of multiple ownership. Figures from 2022 indicate that the number of syndicates increased by 24 per cent to 825, comprising 8,030 people.

The number of racing clubs increased by 6 per cent, comprising 1,683 members.

People can join existing syndicates or racing clubs or establish their own. Syndicates in Ireland comprise 3–100 people, while racing clubs can have an unlimited number of members.

The above figure for syndicates also includes the evolving fractional ownership model, with MyRacehorse having horses in training with Joseph O’Brien and Michael O’Callaghan.

“It is a great way to dip your toe in the water and see if it is the pastime for you,” says HRI’s owner development manager, Amber Byrne of shared ownership, who adds that plenty with the means to indulge in sole ownership prefer syndicates as a means of spreading their risk or because they derive more enjoyment from them.

HRI maintains a register of racehorse owners and can void or suspend owner registrations. The onus falls on the agent to ensure the syndicate/club and its members complies with the rules of racing, HRI directives, owner eligibility policy etc. Unlike the BHA, they do not have a specific code of conduct in place but advise that all syndicates and clubs provide them.

Agents must be registered as full owners and provide necessary ID, bank details etc., while a full list of membership including addresses and contact details and shares held must be supplied and continuously updated. Syndicates/clubs must declare if they are selling shares publicly and declare the maximum number of shares available in a particular horse.

Jack Cantillon, founder of the hugely popular Syndicates.Racing, says HRI has it just right in terms of regulation and oversight.

“We recently registered in France, and it took over a month for our application to be successfully processed; so we should be thankful for how quick it has been for us to do so in Ireland”, Cantillon relates. “We also are registered in New York, and they even wanted my fingerprints before we got over the line! Ireland strikes a balance of enough protections while not over burdening with ridiculous red tape.

“Syndicates are the backbone of building the pipeline of ownership of racehorses throughout the world”, he continues. “We’ve had incidents of people taking a €200 share as their first share in a racehorse and progressing to owning horses worth €100,000 on their own. It’s an amazing journey to see in full sight and something that’s incredibly rewarding”.

Syndicates.Racing has enjoyed spectacular success in a short period in both codes, with runners and winners at a host of major meetings and venues, including graded-winning mares Cabaret Queen and Grangee. Their trainers include Willie Mullins, Joseph O’Brien, Henry de Bromhead, Jessica Harrington, Gavin Cromwell, Peter Fahey, John McConnell, Jack Davison and the aforementioned Johnny Murtagh. They also have horses in training in Britain and America.

Grangee with Jack, John and Tom from Syndicates.Racing.

“We have been blessed with over a thousand owners that have gotten involved in Syndicates.Racing since its inception and bringing so many of them to the winner’s enclosure has been a hugely rewarding thing… If you do have a positive experience, there’s very few more rewarding experiences of intimate involvement that you can get in any sport”.

As mentioned earlier, Murtagh is such a believer in the benefits of shared ownership that he has just launched his own racing club.

“You’d love people to have a good experience of racing. They’re going to be racing, but they’re going to see behind the scenes as well—even things like a horse being shod or going through the stalls; the ins and outs of JP Murtagh on a weekly basis with a horse ready to run. You’ll have a morning on the gallops, a few get-togethers. I think there’s going to be a great take-up and plenty of entertainment.

“There’s a bit more work, but I only speak to the racing manager and they keep everyone else informed. You’re going to have to employ somebody to take videos and keep it updated every day. I want people to see what’s going on and to feel part of it.

“You like to promote the game as best you can and show it in a good light and maybe in a way that people with some bit of interest want to see more and you never know what it leads to. One fella might say, ‘I enjoyed that; can you buy me a horse?’ Rather than jumping into it straight away, they get a good feel.

“I think it’ll work. We’ve a good horse, and we’ve a plan for the horse. We have everything in place, ready to go. I think people will like to be part of it.

While there is “a bit involved” in setting Racing Revolution up, “Murtagh found HRI very helpful. Ireland’s governing body is full square behind shared ownership as a means of growing the sport and industry.

“The promotion of shared ownership is central to our domestic marketing strategy”, Byrne emphasises. “Syndicates and clubs are key in introducing the ownership concept. We see it as an affordable entry stage into ownership and a way for those interested in racing to get closer to the action and behind-the-scenes access.

“For the most part our domestic marketing promotion concentrates on highlighting multiple ownership. There is no other sport that allows the kind of access that ownership offers and allows fans to get fully immersed in a sport that they love”.

Cantillon sees one area of potential improvement.

“I think we as an industry should invest in a comprehensive customer relationship management system for our owners. We should take advantage of affordable technology available to improve owner experience tenfold. Send a special deal to owners on their birthday, invite them back to the anniversary of their winner last year, issue tickets digitally so there’s no mix-ups at the gate. It’s simple stuff but makes a huge difference”.

FRANCE

Syndicates are known as ecurie de groupe in France, which translates directly to racing stables but are generally known as racing clubs. They are not to be confused with the experiential model of racing clubs in Britain and Ireland and which do not exist in France.

Neither are there any micro share companies, though there have been some initial discussions with MyRacehorse.

“It is certainly an interesting model, one which is full of potential in France,” outgoing managing director of France Galop, Olivier Delloye tells us.

There are 44 syndicates in operation in France, and that figure—while low and down on the 72 recorded in 2014—will increase “in the coming months” according to France Galop’s marketing and ownership development manager, Raphaël Naquet. Ecurie Team Spirit, Shamrock Racing, Ecurie Vivaldi, Ecurie Brillantissime, and High Heels Racing Stable are among the flourishing factions; and there are links to several syndicates on the France Galop website.

As Jack Cantillon touched on, the process of registering a syndicate is more arduous in France than elsewhere. Irish native Timmy Love, who is a colleague of Naquet’s in the ownership development wing of France Galop, concedes that point but insists that this is due to the law of the land rather than the racing regulator.

“Setting up a racing club is probably slightly more bureaucratically heavy than what it would be in Ireland or in England, but that’s just the nature of the French system”, Love asserts. “It’s not a reflection on France Galop. It’s just in France (by law); there is quite a rigorous administration system. It’s quite demanding, but it’s to protect the people already within the sport or those trying to come into it.

“It’s by no means rocket science to get set up over here. Once you get all your different documentation together, it’s no more difficult than anywhere else. You just need slightly more documents in the first place”.

The syndicates must be registered as a company, and that means articles of association, declarations of the company, certificates of incorporation are required to establish the company’s eligibility. Once that is done, the usual proof of identification for the agent running the syndicate is required.

Every member of an ecurie de groupe has an owner’s card that entitles them to the exact same benefits as a sole owner. These include being allowed to bring four guests to every meeting at all the France Galop racecourses, with no exclusions. Being able to do that on Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe day is a phenomenally attractive perk as a syndicate member.

The provincial tracks are not bound by general rule as regards to how many people are allowed to attend per owner card or runner, but according to Love, they are generally very hospitable.

“For example, I know Middleham Park (Racing) had a winner in Cagnes-Sur-Mer over the winter (Brave Emperor), and the racecourse was very good to the members of that syndicate that travelled over. That is just to give one example, but there are lots of country tracks that look after their owners extremely well”.

France Galop is considering being more proactive in going out into the marketplace to sell the benefits of syndicates as an ownership option.

“We can see more and more shared ownership is more attractive. It makes the sport more accessible, so it’s certainly something we’re considering; and now we have a good base of racing clubs that are well set up and having a bit of success. It’s becoming an easier product to market”,

French trainers are not as enamoured with shared ownership as their British and Irish counterparts, however, as illustrated by Hélène Hatchiguian of the Association des Entraîneurs de Galop, the French trainers’ association.

“We have more and more owner agreements, but mainly for shared ownership, because having a racehorse is a cost. The consequence is that we have less horses in training,” Hatchiguian observes.

“For a trainer, it is easier and better to have one owner per horse, but now we have less of these owners and more shared ownership. It represents more work for the trainer, and more time (to communicate, for invoicing etc.). If trainers do not have time for it, they need to employ someone to do this job.

“When some shared owners do not pay their training fees, we can appeal to France Galop, the horse cannot run, and it is penalising other owners. In the future, it will be necessary to change the rules: if one or more shared owner does not pay, the horse can still run but the money won by the horse is not paid to the owner but to the trainer’s account”.

GERMANY

Christian von der Recke is cut from the same cloth as George Baker. Land and sea borders are no impediment to the multiple-champion jumps trainer travelling and running horses.

He says running a proper syndicate is difficult in Germany and points us in the direction of Lars-Wilhelm Baumgarten. A former sports agent (with Grand Slam winner Angelique Kerber among his clients), now breeder and board member of Deutscher Galopp, Baumgartner founded Liberty Racing with his wife Nadine and realised a lifetime ambition when Fantastic Moon won the Deutsches Derby in Liberty silks.

Members are glorying in the anticipation of a tilt at the Breeders’ Cup and/or the Japan Cup at present – wherever there is good ground - after the Sarah Steinberg-trained son of Sea The Moon recorded a decisive victory in the Qatar Prix Niel. Some hefty offers came in for the German-bred colt after the romp at ParisLongchamp but they have been rejected by shareholders and he will continue to race for Liberty.

“I worked as a sports agent all over the world and was a lot of times in Australia and saw the syndicates there,” Baumgartner explains. “I decided to sell my company and do what I want—horses, poker, real estate, and coaching. I started breeding and was on the board of German Racing, and I saw the problem: less owners, less breeders.

“I started eight years ago with my partnership ownership, only with two or three friends. We had a lot of success together. Then I decided to make my three- or four-people ownership syndicate bigger and started in 2020, to bring all my owner and breeder know-how to bring more people to horses. That was in my mind, but also in my mind was to win bigger, not just to buy handicap horses for people. We wanted to buy stayers with stamina from good German families for the Classic races, the Derby, the Oaks, and the Leger.

“The idea was that new people can dream and be part of the bigger races. That was the main vision for Liberty Racing. Nadine and I started with 12 shareholders and four horses. The next year, we had 22 shareholders in four horses and then 30 in five horses. This year we will buy 10 to 12 horses with 90 or 100 owners.

“It’s not easy with the German tax situation. We have a lot of law restrictions to bring money together. It’s not like in England and America. They have more share culture, but we did it. We created a good contract, and we have the okay from the government to do it, and so we started”.

Deutscher Galopp is very helpful, Baumgartner tells us, not least than when he brought 50 people to shout on Liberty Racing’s two Derby runners.

There are more racing clubs in Germany than syndicates, but Liberty Racing is a poster child for the latter model with its professionalism and specific departments to cater for acquisitions, financials, social media, and so on.

“German racing was a closed shop. We have to open it. At the moment, we have 1,800 horses in training. That’s not good. We have to find 1,000 new shareholders in horses, and then we find 100, 200 horses more for trainers to train”.

ITALY

Former top trainer and now flourishing bloodstock agent, Valfredo Valiani, is looking forward to attending all the major European sales in the coming weeks and months, but he won’t be buying for Italian syndicates.

“Italian people usually don’t like syndicates, and it’s something that never took off in Italy,” Valiani remarks. “When I used to train, I tried myself with a couple of friends to set up a few syndicates for a few horses. We had results with the horses. We went up to six partners. But Italians are pretty individual. We’re not used to doing syndicates in anything and especially in racehorses.

“It’s not that easy to register a syndicate over here. You’re going to need all the papers for every single partner in the syndicate. So it’s really tough. And then, just the representative is allowed to get to the parade ring.

“We need syndicates because Italian racing is not flying, especially in quality; and when you get a few people together, of course you have more money to spend and more power, and you can look for better horses.

“We do have one syndicate, which is named Equos. It’s very public because it belongs to somebody that runs the only racing paper in Italy. But nobody emulated that, so far at least. Italians are proud to be THE owner, and they don’t feel like being ONE of the owners. There are horses in partnership, but it’s not the norm.”

SCANDINAVIA

Norway does have company-regulated syndicates, but there are some operating on a private level.

“The main reason is that Norwegian rules and regulations do not allow ownership of racehorses to be defined as a business,” says Marianne Ek of the Norwegian Jockey Club. “It has to be taxed as private. This means that there are no incentives for companies to offer this service.

“The industry is constantly working towards our politicians to try to change this, but no luck so far.

“This does not mean that we don’t have syndicates and shared ownerships, but they are set up either by the owners themselves or the trainers.”

In Sweden and Denmark, syndicates are allowed to trade as businesses. Also, there are some companies that specialise in putting syndicates together and running them for a fee.

CONCLUSION

As noted at the start, this is by no means a thorough investigation of shared ownership from the perspective of all stakeholders in all regions—lengthy and all as it is.

It is evident though that while some jurisdictions are more open to shared ownership than others, for a variety of reasons, there is a growing acknowledgement that for trainers, and thus the industry, the model has far more upside than any perceived negative once all stakeholders are protected by watertight regulation and rigorous oversight.

Make it as easy as possible, and make it attractive. After that, the smiles will go miles.

What is racing's "Social Licence" and what does this mean?

Paull Khan expands upon a presentation he gave at the

European Parliament to the MEP’s Horse Group on November 30th

As World Horse Welfare recently pointed out in its excellent review of the subject—while social licence or the ongoing acceptance or approval of society may be ‘intangible, implicit and somewhat fluid’—an industry or activity loses this precious conferment at its peril. Examples, all too close to home, can be seen in greyhound racing in Australia and America or jumps racing in Australia.

What is clear is that our industry is acutely aware of the issue – as are our sister disciplines. The forthcoming Asian Racing Conference in Melbourne in February will feature a session examining what is being done to ‘ensure that (our) a sport is meeting society’s rapidly evolving expectations around welfare and integrity’. And back in November, the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) held a General Assembly whose ‘overriding theme’ was ‘that of social licence, and the importance for all stakeholders to understand the pressing needs for our sport to adapt and monitor the opinions of those around us’.

Considered at that meeting were results of a survey, which indicated that two-thirds of the public do not believe horses enjoy being used in sport and have concerns about their use. Those concerns mainly revolve around the welfare and safety of the horses. Intriguingly, a parallel survey of those with an active involvement in equestrian sport revealed that as many as half of this group even did not believe horses enjoyed their sport; and an even higher proportion than the general public—three-quarters—had concerns about their use.

While it is likely true, to an extent at least, that the public tends not to distinguish between equestrian sports, the specific concerns about horse racing are certainly different from those about Olympic equestrian disciplines, which centre on such matters as bits, bridles, spurs and nosebands.

Upon what, then, does our social licence in European horse racing critically depend? What are the major issues about which the public has opinions or worries, and on which the continuance of our social licence may hang? It should be said at the outset that what follows is not based upon scientific evidence (and the research should certainly be undertaken) but merely reflects the belief of the author. But it is suggested with some confidence that the following (in no particular order) are the three issues uppermost in public consciousness. They are:

Use of the whip

Racecourse injuries/fatalities

Aftercare – the fate of retired racehorses

There are, of course, other matters – the misuse of drugs and medications, gambling harms, etc., but the three topics above seem to account for a large proportion of the public’s anxieties about racing. There are likely to be subtle differences in the views of the public between one European country and another. Certainly, it is true that the volume of public disquiet varies very considerably between nations. In Scandinavia and Great Britain, for example, horse welfare and animal welfare more generally are very much front of mind and near the centre of public discourse. It is far less evident in several other countries.

But it is illuminating to look at what racing has been doing in recent years in the three areas listed above, and what the future looks like. A survey was conducted among member countries of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation (EMHF); and it is clear that, while there is much still to be done, there has been significant and sustained progress and good reason to believe that this is likely to continue – and in fact accelerate – over the next few years.

Use of the whip

Let us consider whip use first. At the most recent World Horse Welfare Annual Conference in London in November, straplined ‘When Does Use Become Abuse’, one speaker was called upon to give strategic advice as to how to counter negative perceptions of equestrianism.

What he decided to major on was striking. With the whole breadth of the equine sector from which to draw, he chose to hone in on horseracing and—more specifically yet—on the issue of whip use. It was a salutary further example of how, while the whip may be a tiresome distraction to many, it is front and centre in the minds of many of the public.

Is there any more emotive or divisive issue within racing than the whip? Admittedly, most racing professionals hold that it really is very difficult to hurt a horse with the mandated padded crops, even if one wanted to. And, with veterinary supervision at all tracks, it is impossible to get away with, even if one did. In brief, they don’t consider this a welfare issue, but rather one of public perception.

But it is then that the divisions set in. Some conclude that all that is necessary to do has been done, and that any further restriction on the whip’s use would constitute pandering to an ignorant public. Others argue that, even if it is just a matter of public perception and the horses are not being hurt or abused, the sight of an animal being struck by a human is now anathema to increasingly broad swathes of society—in a similar way to the sight of a child being struck by an adult: a commonplace 50 years ago, but rare today. Therefore, the sport must act to be ahead of the curve of public sentiment in order to preserve its social licence.

How is this argument playing out? Let us look at a key element of the Rules of Racing in 18 European racing nations—the maximum number of strikes allowed in a race is a blunt measure, indeed, and one that takes no account of other variables such as the penalty regime for transgressions, but one that, nonetheless, paints a telling picture.

The first map shows how things stood 20 years ago. The majority of the countries are shown in black, denoting that there was no specified limit to the number of strikes. Just one appears in white – Norway banned the use of the whip as long ago as 1986.

The second paints the picture as it was 10 years ago. Eleven of the 18 countries had, in the intervening decade, changed their rules and applied a lower maximum number of strikes, and are shown in a lighter colour as a result.

Today’s situation is shown in the third map. All but one of the countries (excluding Norway) have tightened up their whip use rules still further over the past decade. None now allows unlimited use, and countries now banning the use of the whip for encouragement, number four.

It can be concluded that all countries across Europe are moving towards more restricted use of the whip. At different speeds and from different starting points, the direction of travel is common.

What will the situation be in another 10 years? Many administrators within EMHF countries, when asked to speculate on this, gave the view that there would be no whip tolerance within ten years and that the Scandinavian approach will have been adopted.

On the other hand, Britain has recently concluded that the biggest public consultation on the subject and the new rules that are being introduced do not include a reduction in the number of strikes, but rather a series of other measures, including the possible disqualification of the horse and importantly, the requirement only to use the whip in the less visually offensive backhand position.

Whether or not we will see a total ban within the next decade, it must be long odds-on that restrictions on whip use, across the continent, will be stricter again than they are today.

Aftercare

Twenty years ago, little thought was given to the subject of aftercare. There were some honourable exceptions: in Greece, the Jockey Club required its owners to declare if they could no longer provide for their horse, in which case it was placed in the care of an Animal Welfare organisation. Portugal had a similar reference in its Code. Most tellingly, in Britain a trail-blazing charity, Retraining of Racehorses (RoR), had been launched, following a review by the former British Horseracing Board.

Ten years ago, RoR had nearly 10,000 horses registered, had developed a national programme of competitions and events in other equestrian disciplines, and was holding parades at race-meeting to showcase the abilities of former racehorses to enter new careers.

Di Arbuthnot, RoR’s chief executive, explains, “In the UK, a programme of activities for thoroughbreds had started to encourage more owner/riders to take on former racehorses. This was supported by regional volunteers arranging educational help with workshops, clinics and camps to help the retraining process. Other countries were looking at this to see if similar ideas would work in Europe and beyond.

“Racing’s regulators had begun to think that this was an area they should be looking to help; retraining operators and charities that specialised in thoroughbreds were becoming recognised and supported; and classes at equestrian events began in some countries. Owner/riders were looking to take on a thoroughbred in place of other breeds to compete or as a pleasure horse; the popularity of the thoroughbred was growing, not just by professional riders to use in equestrian disciplines, but also by amateurs to take on, care for and enjoy the many attributes of former racehorses.

“The aftercare of the thoroughbred was on the move.”

But not a great deal else was different in the European aftercare landscape.

Since then, however, there has been little short of an explosion of aftercare initiatives. In 2016, the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses (IFAR) was born, “to advocate for the lifetime care of retired racehorses, to increase awareness within the international racing community of this important responsibility.” In this endeavour, IFAR is not in any way facing resistance from Racing Authorities – far from it. It is pushing against an open door.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities has, as one of its twelve objectives, the promotion of aftercare standards. And the chair of its Welfare Committee, Jamie Stier, said some years ago that there is ‘now a better understanding and greater recognition that our shared responsibility for the welfare of racehorses extends beyond their career on the racetrack’.

This direction from the top has been picked up and is increasingly being put into active practice. Also in 2016, France launched its own official charity Au Dela des Pistes, (‘beyond the racetrack’), in 2020 Ireland followed suit with Treo Eile (‘another direction’). By 2019, in Britain, remarkably, many more thoroughbreds were taking part in dressage than running in steeplechases!

So now the three main thoroughbred racing nations in Europe all have active and established aftercare programmes; and many other smaller racing nations are moving in that direction. It is not just a matter of repurposing in other equestrian pursuits – many of those horses retiring from racing that are not suited to competitive second careers are simply re-homed in retirement and others find profitable work in areas such as Equine Assisted Therapy.

Arbuthnot (also chair of IFAR) adds: “For racing to continue as we know it, we must assure the general public, those that enjoy racing, that thoroughbreds are not discarded when their racing days are over and that they are looked after and have the chance of a second career. It is up to all of us around the world to show that we care what happens to these horses wherever their racing days end and show respect to the thoroughbred that has given us enjoyment during their racing career, whether successful or not on the racecourse. If we do this, we help ensure that horse racing continues in our lifetime and beyond.”

It is important to publicise and promote the aftercare agenda, and the EMHF gives IFAR a standing platform at its General Assembly meetings. EMHF members have translated the IFAR ‘Tool Kit’—for Racing Authorities keen to adopt best practice—into several different European languages.

Time Down Under and Justine Armstrong-Small: Time Down Under failed to beat a single horse in three starts but following his retirement from racing, he has reinvented himself, including winning the prestigious showing title of Tattersalls Elite Champion at Hickstead in June 2022. Images courtesy of Hannah Cole Photography.

British racing recently established an independently chaired Horse Welfare Board. In 2020, the Board published its strategy ‘A Life Well Lived’, whose recommendations included collective lifetime responsibility for the horse, incorporating traceability across the lifetimes of horses bred for racing.

Traceability will be key to future progress, and initiatives such as the electronic equine passport, which has been deployed among all thoroughbreds in Ireland and Britain, will play a vital part. Thoroughbred Stud Book birth records are impeccable, and we know the exact number of foals registered throughout this continent and beyond. The aim must be to establish the systems that enable us to ascertain, and then quantify the fate of each, at the least until their first port of call after retirement from racing.

Racecourse injuries

There can be nothing more distressing – for racing professionals and casual observers alike – than to see a horse break down. The importance of minimising racecourse injuries—and, worse still, fatalities—is something everyone agrees upon. What is changing, though, it would appear, is the potential for scientific advances to have a significant beneficial effect.

Of course, accidents can and do befall horses anywhere and they can never be eliminated entirely from sport. But doing what we can to mitigate risk is our ethical duty, and effectively publicising what we have done and continue to do may be a requirement for our continued social licence.

There is much that can be said. It is possible to point to a large number of measures that have been taken over recent years, with these amongst them:

Better watering and abandonment of jump racing if ground is hard

Cessation of jump racing on all-weather tracks

Cessation of jump racing on the snow

Safer design, construction and siting of obstacles

By-passing of obstacles in low sunlight

Colouring of obstacles in line with equine sight (orange to white)

Heightened scrutiny of inappropriate use of analgesics

Increased prevalence of pre-race veterinary examinations, with withdrawal of horses if necessary

The outlawing of pin-firing, chemical castration, blistering and blood-letting

Abandonment of racing in extreme hot weather

Many of the above relate to jump racing, and Britain has witnessed a reduction of 20% in jump fatality rates over the past 20 years. But there is more that must be done, and a lot of work is indeed being done in this space around the world.

One of the most exciting recent developments is the design and deployment of ground-breaking fracture support kits which were distributed early in 2022 to every racecourse in Britain.

Compression boots suitable for all forelimb fractures

By common consent, they represent a big step forward – they are foam-lined and made of a rigid glass reinforced plastic shell; they’re easily and securely applied, adjustable for varying sizes of hoof, etc. They reduce pain and anxiety, restrict movement which could do further damage, and allow the horse to be transported by horse ambulance to veterinary facilities.

X-rays can then be taken through these boots, allowing diagnosis and appropriate treatment. These kits have proved their worth already: they were used on 14 occasions between April and December last year, and it would appear that no fewer than four of these horses have not only recovered but are in fine shape to continue their careers. It is easy to envisage these or similar aids being ubiquitous across European racetracks in the near future.

Modular splints suitable for slab fractures of carpal bones

Perhaps of greatest interest and promise are those developments which are predictive in nature, and which seek to identify the propensity for future problems in horses.

Around the world, there are advances in diagnostic testing available to racecourse vets. PET scanners, bone scanners, MRI scanners and CT scanners are available at several tracks In America, genetic testing for sudden death is taking place, as is work to detect horses likely to develop arrhythmias of the heart.

Then there are systems that are minutely examining the stride patterns of horses while galloping to detect abnormalities or deviations from the norm. In America, a great deal of money and time is being spent developing a camera-based system and, in parallel, an Australian-US partnership is using the biometric signal analysis that is widely used in other sports.

The company – StrideSAFE – is a partnership between Australian company StrideMASTER and US company Equine Analysis. They make the point that, while pre-race examinations that involve a vet trotting a horse up and down and looking for signs of lameness, can play a useful role, many issues only become apparent at the gallop.

There are, in any case, limitations to what is discernible to the naked eye, which works at only 60 hertz. StrideMASTER’s three-ounce movement sensors, which fit into the saddlecloth, work at 2,400 hertz, measuring movements in three dimensions – forward and backward, up and down and side to side, and building up a picture of each horse’s ‘stride fingerprint’.

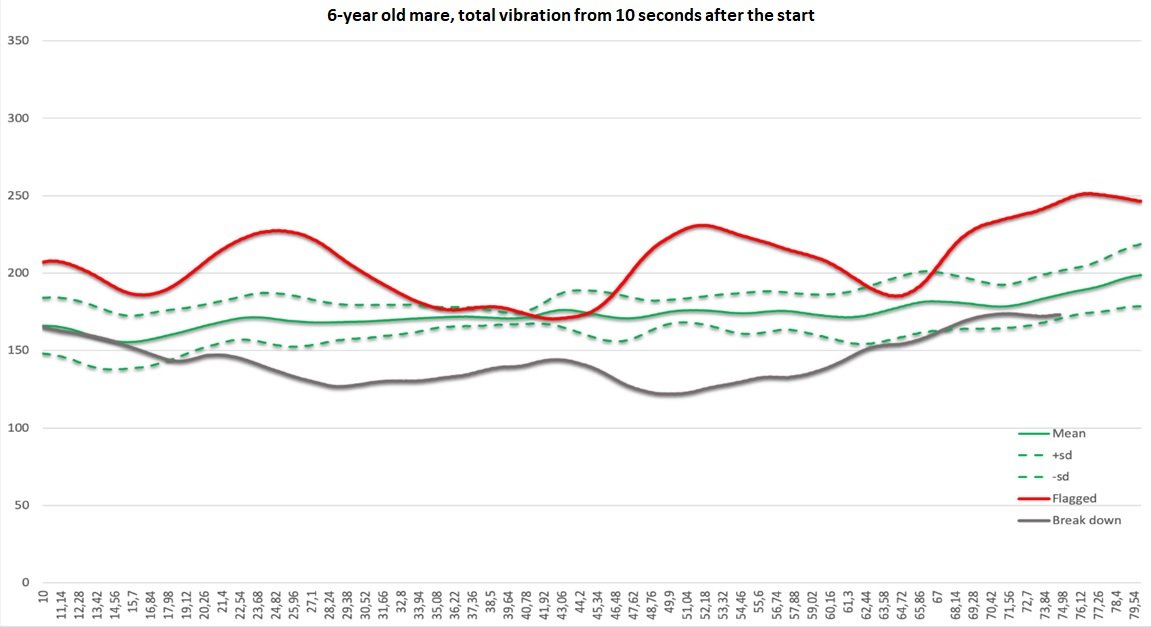

In a blind trial, involving thousands of horses, 27 of which had suffered an injury, this system had generated a warning ‘red-flag’ for no fewer than 25 of them. The green lines in the centre of this diagram are this horse’s normal stride fingerprint; the red line was the deviant pattern that would have flagged up the potential problem, and the grey line was where the horse then sadly injured itself.

The ‘stride fingerprint’ of a racehorse

While the false-positive rate is impressive for such screening tools, another enemy of all predictive technologies is the false positive, and ways need to be found to take action on the findings without imposing potentially unnecessary restrictions on horses’ participation. At present, the StrideMASTER system is typically throwing up three or four red flags for runners at an Australian meeting—more in America.

A study in the spring by the Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council, centering on Churchill Downs, will seek to hone in on true red flags and to develop a protocol for subsequent action. David Hawke, StrideMaster managing director, expands, “Protocols will likely vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, depending on the imaging modalities available. At Churchill Downs, they will have a PET scan, and we will be going straight from red-flag to PET scan.”

There will be other approaches available to regulators involving, for example, discussion with the trainer, a requirement for a clean vet’s certificate, or perhaps for a normal ‘fingerprint’, before racing next.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for continued investment and resource allocation by Racing Authorities. But the will would seem to be there. In Britain, €7M from betting will, over the next three years, fund an extensive array of no fewer than 26 horse welfare projects, covering such matters as education and support for re-homers, analysis of medication data and clinical records, fatalities occurring off the track, ground/going research and obstacle improvement and development. That is a serious statement of intent and an illustration of just how high in importance the welfare of racehorses has now become.

Of course, not all racing nations have the resources to conduct such research. It will be vital, therefore, that the lessons learnt are shared throughout the racing world. In Europe, this is where the EMHF will play a vital role. The federation has always had, as primary aims, education and the adoption of best practice across its membership.

The hope must be that, through all these measures and many others in combination, we can assuage the concerns of the public sufficiently to retain our social licence. But let our ambitions not rest there. We must also strive to shift the debate, to move onto the front foot and invite a focus on the many positive aspects of racing, as an example of the partnership between man and horse that brings rich benefit to both parties.

Elsewhere in this issue, there is a feature on racing in Turkey, and it was the founding father of that country, Kemal Ataturk, who famously said:

“Horseracing is a social need for modern societies.”

We should reinforce at every opportunity the fact that racing provides colour, excitement, entertainment, tax revenues, rural employment, a sense of historical and cultural identity and much more to the human participants. It is also the very purpose of a thoroughbred’s life and rewards it with ‘a life well lived.’

We have a lot more to do, but let’s hope we can turn the tide of public opinion such that people increasingly look at life as did Ataturk.