2023 Champion Trainer profiles - Peter Schiergen (Germany) / Kadir Baltaci (Turkey) / Claudia Erni (Switzerland)

NATIONAL CHAMPION TRAINERS IN FOCUS

In this issue, we take a look at some more of Europe’s champion national trainers, courtesy of the latest data compiled by Dr Marian Surda, doyen of Slovakian racing.

A notable feature of the tables, when comparing the last two years, is the infrequency of trainers retaining their crowns. Only in 7 of the 18 countries that featured in both years did this happen (France, Jean-Claude Rouget; Ireland, Aidan O’Brien; Spain, Guillermo Arizkorreta; Germany, Peter Schiergen; Norway, Niels Petersen and Greece, Charalambos Charalambus). The baton changed in all other countries, including in Great Britain, the country whose trainer earned the most money, for the second year running. This time, that trainer was the father and son combination of John and Thady Gosden, who wrested the title from Charlie Appleby.

Among the jockeys, Maxim Guyon, in France and William Buick, in Britain headed the table once again. But the dominance of the big three countries – France, Britain and Ireland – was interrupted by an extraordinary performance by Turkey’s Champion, 20-year-old Vedat Abis, who clocked up a remarkable 283 wins – far more than any of his fellow champions.

Our featured trainers this year are Peter Schiergen (Germany / 5th in the table), Kadir Baltaci (Turkey / 6th) and Claudia Erni (Switzerland / 11th).

PETER SCHIERGEN

The name of Peter Schiergen is a familiar one across the European racing scene and beyond, with Group wins in France, Britain, Italy and Dubai as well as his native Germany. At time of writing, that Group race tally stands at 199. Champion Trainer in Germany no fewer than eight times (2002, 2005, 2006, 2013, 2015, 2021, 2022 and 2023), with six German Derby wins to his name (Boreal 2001, Schiaparelli 2006, Kamsin 2008, Lucky Speed 2013, Nutan 2015 and Sammarco 2022), his crowning single achievement remains his Arc win with Danedream in 2011.

But before becoming one of the most successful German trainers of recent generations, Peter had been one of his country’s most successful jockeys. His outstanding record in the saddle encompassed five jockeys’ championships – 1992 to 1996 – and nearly 1500 wins, including a record 271 successes in 1995.

I asked Peter about his journey into racing and what had led to his becoming a jockey at the age of 16. “I always wanted to become a show jumper. My plan was just to do my apprenticeship in racing and after that to go back to show jumping. But it turned out differently and I had quite a bit of success as an apprentice and stayed in the game”.

The transition from jockey to trainer (taking over from fellow legend Heinz Jentzsch in 1998) was made at a younger age – just 33 – than is often the case.

“The opportunity came up to take over from Heinz Jentsch. I knew that this was a huge chance and even though it was quite early I decided to take over. I started in 1998 in Köln and still train there today. In 2009 we built a new stable next to the old one so that’s really the main thing that has changed”.

“I had a great time as a jockey and was five consecutive years champion jockey and broke the European record in 1995. But the owners didn’t give me the chance to ride in the big races abroad such as Lando in the Japan Cup. This is something I don’t want to happen to my stable jockeys and therefore I use them both in Germany and abroad.

What does Schiergen consider the pros and cons of training on the track? “The horses are used to the racetrack. A great benefit is that it’s easier to get staff. Furthermore, the racecourse is in charge of preparing the training facilities. A disadvantage would be that we have certain times at which we must be at the track, as there are many trainers who use the facilities. On a private track you have more peace”.

“The team consists of 25 staff. It gets more and more difficult to get good staff and competent work riders. We have a great team and many people have been staff members for many years. There are plenty of Germans working with us. Other than Germans, most of the staff tend to be from the eastern European countries such as Poland, Czech Republic, Bulgaria etc.”.

When asked which trainer he admires the most, Schiergen replies: “I didn’t have a jockey I admired the most when I was a jockey, and now, as a trainer, neither do I have a trainer I would single out as admiring. I look at many others and try to take the best of each”.

“The state of racing in Germany isn’t great, but there are many ambitious people who are trying to bring the sport back to better times. It’s difficult with social change and especially the animal welfare movement. Racing’s lobby sometimes appears to be too weak to work against these forces. Therefore, we need a change. It’s difficult to compare our racing jurisdiction to other countries. We don’t have training facilities such as Newmarket or Chantilly.”

As well as the 200 Group race milestone, Schiergen has another in his sights. Ending last year on 1,907 wins on the flat and 31 over jumps, it is a real possibility that he could send out his 2,000th winner this year. “Certainly is a milestone and a great achievement. But it is more important to win big races.”

KADIR BALTACI

Kadir Baltaci’s 31 wins last year came at the hooves of just 37 individual starters (his stable currently houses just 30 horses in training). His tally included seven domestic Group races, including three at Group 1.

From Baltaci’s base in Turkey’s capital, Ankara, it is a long haul to the tracks where he does most of his racing: a 5-hour drive north-west takes him to the nation’s racing headquarters, Veliefendi in Istanbul, or a lengthier run yet in the opposite direction finds the track in Adana.

“I was born in Adana”, Baltaci begins. “I lived in Adana until 2010. Adana is my city, my place but Ankara is now ‘my city’ and ‘my place’, where I live with my two sons and my wife. Though I train my horses here, when they are ready to race I mostly prefer to run in Istanbul because of the classic and other big races that are run at Veliefendi racecourse”.

“I began as an Assistant Trainer in 2011. After spending seven seasons as an Assistant, I started training in my own right, in 2017.

“When I was at high school, I was best friends with the son of the owner of the famous Turkish-Arabian horse Nurhat. I often went with my friend to (Adana’s) Yesiloba Racecourse to see the horse. As a child, I loved the horses. I used to watch racing on the television, especially the classic and GAZI races.

“Workwise, I started out working at my father's painting company, but it collapsed. I then worked as a driver for one of my now-owners, Mr Fedai Kahraman. When working as his driver, he often used to send me to the races at Ankara, in order to help his trainer out. After a couple of years, he asked me if I would move to the track to assist the trainer. I said ‘yes’ and that’s how my journey started.

“I don’t have a private training centre. Like all trainers in Turkey, I must be based at one of the Jockey Club racecourses. We chose Ankara for the wintertime: because the racetrack is empty then, I can easily prepare my horses.

“I have 20 people working for me. My staff are all Turkish. We did try employees of other nationalities, but I did not like the way they worked. Most of my crew have been with me since I started training. Because we have been working together for so long, it is a great relief to me that they know exactly what I want. It is hard to find new people to take care of horses. Really hard. I have five exercise riders. You can find exercise riders very easily, but most are not proficient. The Jockey Club of Turkey trains exercise riders. One of mine came from there – he graduated last year. But they are young and need time to learn the job properly. We have also got a broader problem with finding stable staff generally. Not only me, other trainers have the same problem”.

To date, Baltaci has ventured abroad to race but once, sending a runner to Meydan to contest the Grade 2 Cape Verdi and Ballanchine Stakes. “I believe my horses will run more often abroad. My big ambition is to run in - and win - a European Classic.

“We are not well educated about training practices in other countries, so I will not make comparisons. All I would say is that many are lucky to have private training facilities. I think our trainers probably spend more time in nursing horses which have suffered minor injuries back into racing”.

Baltaci places much hope for the future in Serdal Adali, Adana-born President of the Turkish Jockey Club. “Mr Serdal Adali is spending time ensuring a better future for us. I believe he will succeed. Then my countrymen will be more interested in racing outside of Turkey.”

Balaci’s strike rate, particularly at the top level, is impressive indeed, but he is modest when asked to explain the secret of his success. “It’s down to the efforts of everyone, from my horse owner to my team. That's why I can't give any specific reasons for my success. I have 30 in training right now. Thirty different horses, which all act differently, and that is why I train each horse differently”.

CLAUDIA ERNI

Over in Switzerland, there has seen a changing of the guard. After several years of domination by Miro Weiss, there is a new woman in town. Step forward, Claudia Erni. Her yard of 20 horses – ranging from 2yo’s to a 10yo sprinter and stayer, ranks fourth by size within the country, but in 2023 punched above its weight to capture the championship.

“I grew up with horses. My father had a riding school. I took part in some national dressage competitions. My father’s girlfriend was in racing, and this was how I found my way into racing. I rode as an amateur, both on the flat and over jumps, and also held an amateur training license before taking out my professional trainer’s licence in 2006”.

“I am also a physical therapist and still devote two afternoons a week to working in this profession”.

Erni trains from Switzerland’s westernmost racetrack, Avenches, south of Lake Neuchatel. This impressive complex (a good idea of which can be gleaned from www.iena.ch), extends to 140 hectares/350 acres and accommodates multiple equine disciplines. It is important to the finances of Swiss racing, many of its race days being taken by the French betting operator, PMU.

“It is really nice to train here. We have a lot of space. We have two tracks of 1600m and 1800m circumference, with paddocks and a horse-walker. And I am almost alone here! At present, I have four employees, from France, Switzerland and Chechia. I do find it difficult to find good riders. For so many, money is more important than passion - sad, but that’s how it is”.

“My owners have been in the business for a long time. It is difficult to find young owners. But I am fortunate, in that mine came to me – I didn’t have to go looking for them!”

“I often race in France, Germany and Italy, when the owners allow it. I love Longchamp. We are very close to France – for example, it takes just three hours to reach Lyon.”

And what of the outlook for the sport in her country? “As in every country, racing in Switzerland is getting harder. It is harder to find sponsors and new owners, and the number of racehorses is reducing. The Swiss racing authority is trying to find ways to increase the popularity of the sport. Maybe, jockeys will be prevented in future from using the whip?”

What is racing's "Social Licence" and what does this mean?

Paull Khan expands upon a presentation he gave at the

European Parliament to the MEP’s Horse Group on November 30th

As World Horse Welfare recently pointed out in its excellent review of the subject—while social licence or the ongoing acceptance or approval of society may be ‘intangible, implicit and somewhat fluid’—an industry or activity loses this precious conferment at its peril. Examples, all too close to home, can be seen in greyhound racing in Australia and America or jumps racing in Australia.

What is clear is that our industry is acutely aware of the issue – as are our sister disciplines. The forthcoming Asian Racing Conference in Melbourne in February will feature a session examining what is being done to ‘ensure that (our) a sport is meeting society’s rapidly evolving expectations around welfare and integrity’. And back in November, the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) held a General Assembly whose ‘overriding theme’ was ‘that of social licence, and the importance for all stakeholders to understand the pressing needs for our sport to adapt and monitor the opinions of those around us’.

Considered at that meeting were results of a survey, which indicated that two-thirds of the public do not believe horses enjoy being used in sport and have concerns about their use. Those concerns mainly revolve around the welfare and safety of the horses. Intriguingly, a parallel survey of those with an active involvement in equestrian sport revealed that as many as half of this group even did not believe horses enjoyed their sport; and an even higher proportion than the general public—three-quarters—had concerns about their use.

While it is likely true, to an extent at least, that the public tends not to distinguish between equestrian sports, the specific concerns about horse racing are certainly different from those about Olympic equestrian disciplines, which centre on such matters as bits, bridles, spurs and nosebands.

Upon what, then, does our social licence in European horse racing critically depend? What are the major issues about which the public has opinions or worries, and on which the continuance of our social licence may hang? It should be said at the outset that what follows is not based upon scientific evidence (and the research should certainly be undertaken) but merely reflects the belief of the author. But it is suggested with some confidence that the following (in no particular order) are the three issues uppermost in public consciousness. They are:

Use of the whip

Racecourse injuries/fatalities

Aftercare – the fate of retired racehorses

There are, of course, other matters – the misuse of drugs and medications, gambling harms, etc., but the three topics above seem to account for a large proportion of the public’s anxieties about racing. There are likely to be subtle differences in the views of the public between one European country and another. Certainly, it is true that the volume of public disquiet varies very considerably between nations. In Scandinavia and Great Britain, for example, horse welfare and animal welfare more generally are very much front of mind and near the centre of public discourse. It is far less evident in several other countries.

But it is illuminating to look at what racing has been doing in recent years in the three areas listed above, and what the future looks like. A survey was conducted among member countries of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation (EMHF); and it is clear that, while there is much still to be done, there has been significant and sustained progress and good reason to believe that this is likely to continue – and in fact accelerate – over the next few years.

Use of the whip

Let us consider whip use first. At the most recent World Horse Welfare Annual Conference in London in November, straplined ‘When Does Use Become Abuse’, one speaker was called upon to give strategic advice as to how to counter negative perceptions of equestrianism.

What he decided to major on was striking. With the whole breadth of the equine sector from which to draw, he chose to hone in on horseracing and—more specifically yet—on the issue of whip use. It was a salutary further example of how, while the whip may be a tiresome distraction to many, it is front and centre in the minds of many of the public.

Is there any more emotive or divisive issue within racing than the whip? Admittedly, most racing professionals hold that it really is very difficult to hurt a horse with the mandated padded crops, even if one wanted to. And, with veterinary supervision at all tracks, it is impossible to get away with, even if one did. In brief, they don’t consider this a welfare issue, but rather one of public perception.

But it is then that the divisions set in. Some conclude that all that is necessary to do has been done, and that any further restriction on the whip’s use would constitute pandering to an ignorant public. Others argue that, even if it is just a matter of public perception and the horses are not being hurt or abused, the sight of an animal being struck by a human is now anathema to increasingly broad swathes of society—in a similar way to the sight of a child being struck by an adult: a commonplace 50 years ago, but rare today. Therefore, the sport must act to be ahead of the curve of public sentiment in order to preserve its social licence.

How is this argument playing out? Let us look at a key element of the Rules of Racing in 18 European racing nations—the maximum number of strikes allowed in a race is a blunt measure, indeed, and one that takes no account of other variables such as the penalty regime for transgressions, but one that, nonetheless, paints a telling picture.

The first map shows how things stood 20 years ago. The majority of the countries are shown in black, denoting that there was no specified limit to the number of strikes. Just one appears in white – Norway banned the use of the whip as long ago as 1986.

The second paints the picture as it was 10 years ago. Eleven of the 18 countries had, in the intervening decade, changed their rules and applied a lower maximum number of strikes, and are shown in a lighter colour as a result.

Today’s situation is shown in the third map. All but one of the countries (excluding Norway) have tightened up their whip use rules still further over the past decade. None now allows unlimited use, and countries now banning the use of the whip for encouragement, number four.

It can be concluded that all countries across Europe are moving towards more restricted use of the whip. At different speeds and from different starting points, the direction of travel is common.

What will the situation be in another 10 years? Many administrators within EMHF countries, when asked to speculate on this, gave the view that there would be no whip tolerance within ten years and that the Scandinavian approach will have been adopted.

On the other hand, Britain has recently concluded that the biggest public consultation on the subject and the new rules that are being introduced do not include a reduction in the number of strikes, but rather a series of other measures, including the possible disqualification of the horse and importantly, the requirement only to use the whip in the less visually offensive backhand position.

Whether or not we will see a total ban within the next decade, it must be long odds-on that restrictions on whip use, across the continent, will be stricter again than they are today.

Aftercare

Twenty years ago, little thought was given to the subject of aftercare. There were some honourable exceptions: in Greece, the Jockey Club required its owners to declare if they could no longer provide for their horse, in which case it was placed in the care of an Animal Welfare organisation. Portugal had a similar reference in its Code. Most tellingly, in Britain a trail-blazing charity, Retraining of Racehorses (RoR), had been launched, following a review by the former British Horseracing Board.

Ten years ago, RoR had nearly 10,000 horses registered, had developed a national programme of competitions and events in other equestrian disciplines, and was holding parades at race-meeting to showcase the abilities of former racehorses to enter new careers.

Di Arbuthnot, RoR’s chief executive, explains, “In the UK, a programme of activities for thoroughbreds had started to encourage more owner/riders to take on former racehorses. This was supported by regional volunteers arranging educational help with workshops, clinics and camps to help the retraining process. Other countries were looking at this to see if similar ideas would work in Europe and beyond.

“Racing’s regulators had begun to think that this was an area they should be looking to help; retraining operators and charities that specialised in thoroughbreds were becoming recognised and supported; and classes at equestrian events began in some countries. Owner/riders were looking to take on a thoroughbred in place of other breeds to compete or as a pleasure horse; the popularity of the thoroughbred was growing, not just by professional riders to use in equestrian disciplines, but also by amateurs to take on, care for and enjoy the many attributes of former racehorses.

“The aftercare of the thoroughbred was on the move.”

But not a great deal else was different in the European aftercare landscape.

Since then, however, there has been little short of an explosion of aftercare initiatives. In 2016, the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses (IFAR) was born, “to advocate for the lifetime care of retired racehorses, to increase awareness within the international racing community of this important responsibility.” In this endeavour, IFAR is not in any way facing resistance from Racing Authorities – far from it. It is pushing against an open door.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities has, as one of its twelve objectives, the promotion of aftercare standards. And the chair of its Welfare Committee, Jamie Stier, said some years ago that there is ‘now a better understanding and greater recognition that our shared responsibility for the welfare of racehorses extends beyond their career on the racetrack’.

This direction from the top has been picked up and is increasingly being put into active practice. Also in 2016, France launched its own official charity Au Dela des Pistes, (‘beyond the racetrack’), in 2020 Ireland followed suit with Treo Eile (‘another direction’). By 2019, in Britain, remarkably, many more thoroughbreds were taking part in dressage than running in steeplechases!

So now the three main thoroughbred racing nations in Europe all have active and established aftercare programmes; and many other smaller racing nations are moving in that direction. It is not just a matter of repurposing in other equestrian pursuits – many of those horses retiring from racing that are not suited to competitive second careers are simply re-homed in retirement and others find profitable work in areas such as Equine Assisted Therapy.

Arbuthnot (also chair of IFAR) adds: “For racing to continue as we know it, we must assure the general public, those that enjoy racing, that thoroughbreds are not discarded when their racing days are over and that they are looked after and have the chance of a second career. It is up to all of us around the world to show that we care what happens to these horses wherever their racing days end and show respect to the thoroughbred that has given us enjoyment during their racing career, whether successful or not on the racecourse. If we do this, we help ensure that horse racing continues in our lifetime and beyond.”

It is important to publicise and promote the aftercare agenda, and the EMHF gives IFAR a standing platform at its General Assembly meetings. EMHF members have translated the IFAR ‘Tool Kit’—for Racing Authorities keen to adopt best practice—into several different European languages.

Time Down Under and Justine Armstrong-Small: Time Down Under failed to beat a single horse in three starts but following his retirement from racing, he has reinvented himself, including winning the prestigious showing title of Tattersalls Elite Champion at Hickstead in June 2022. Images courtesy of Hannah Cole Photography.

British racing recently established an independently chaired Horse Welfare Board. In 2020, the Board published its strategy ‘A Life Well Lived’, whose recommendations included collective lifetime responsibility for the horse, incorporating traceability across the lifetimes of horses bred for racing.

Traceability will be key to future progress, and initiatives such as the electronic equine passport, which has been deployed among all thoroughbreds in Ireland and Britain, will play a vital part. Thoroughbred Stud Book birth records are impeccable, and we know the exact number of foals registered throughout this continent and beyond. The aim must be to establish the systems that enable us to ascertain, and then quantify the fate of each, at the least until their first port of call after retirement from racing.

Racecourse injuries

There can be nothing more distressing – for racing professionals and casual observers alike – than to see a horse break down. The importance of minimising racecourse injuries—and, worse still, fatalities—is something everyone agrees upon. What is changing, though, it would appear, is the potential for scientific advances to have a significant beneficial effect.

Of course, accidents can and do befall horses anywhere and they can never be eliminated entirely from sport. But doing what we can to mitigate risk is our ethical duty, and effectively publicising what we have done and continue to do may be a requirement for our continued social licence.

There is much that can be said. It is possible to point to a large number of measures that have been taken over recent years, with these amongst them:

Better watering and abandonment of jump racing if ground is hard

Cessation of jump racing on all-weather tracks

Cessation of jump racing on the snow

Safer design, construction and siting of obstacles

By-passing of obstacles in low sunlight

Colouring of obstacles in line with equine sight (orange to white)

Heightened scrutiny of inappropriate use of analgesics

Increased prevalence of pre-race veterinary examinations, with withdrawal of horses if necessary

The outlawing of pin-firing, chemical castration, blistering and blood-letting

Abandonment of racing in extreme hot weather

Many of the above relate to jump racing, and Britain has witnessed a reduction of 20% in jump fatality rates over the past 20 years. But there is more that must be done, and a lot of work is indeed being done in this space around the world.

One of the most exciting recent developments is the design and deployment of ground-breaking fracture support kits which were distributed early in 2022 to every racecourse in Britain.

Compression boots suitable for all forelimb fractures

By common consent, they represent a big step forward – they are foam-lined and made of a rigid glass reinforced plastic shell; they’re easily and securely applied, adjustable for varying sizes of hoof, etc. They reduce pain and anxiety, restrict movement which could do further damage, and allow the horse to be transported by horse ambulance to veterinary facilities.

X-rays can then be taken through these boots, allowing diagnosis and appropriate treatment. These kits have proved their worth already: they were used on 14 occasions between April and December last year, and it would appear that no fewer than four of these horses have not only recovered but are in fine shape to continue their careers. It is easy to envisage these or similar aids being ubiquitous across European racetracks in the near future.

Modular splints suitable for slab fractures of carpal bones

Perhaps of greatest interest and promise are those developments which are predictive in nature, and which seek to identify the propensity for future problems in horses.

Around the world, there are advances in diagnostic testing available to racecourse vets. PET scanners, bone scanners, MRI scanners and CT scanners are available at several tracks In America, genetic testing for sudden death is taking place, as is work to detect horses likely to develop arrhythmias of the heart.

Then there are systems that are minutely examining the stride patterns of horses while galloping to detect abnormalities or deviations from the norm. In America, a great deal of money and time is being spent developing a camera-based system and, in parallel, an Australian-US partnership is using the biometric signal analysis that is widely used in other sports.

The company – StrideSAFE – is a partnership between Australian company StrideMASTER and US company Equine Analysis. They make the point that, while pre-race examinations that involve a vet trotting a horse up and down and looking for signs of lameness, can play a useful role, many issues only become apparent at the gallop.

There are, in any case, limitations to what is discernible to the naked eye, which works at only 60 hertz. StrideMASTER’s three-ounce movement sensors, which fit into the saddlecloth, work at 2,400 hertz, measuring movements in three dimensions – forward and backward, up and down and side to side, and building up a picture of each horse’s ‘stride fingerprint’.

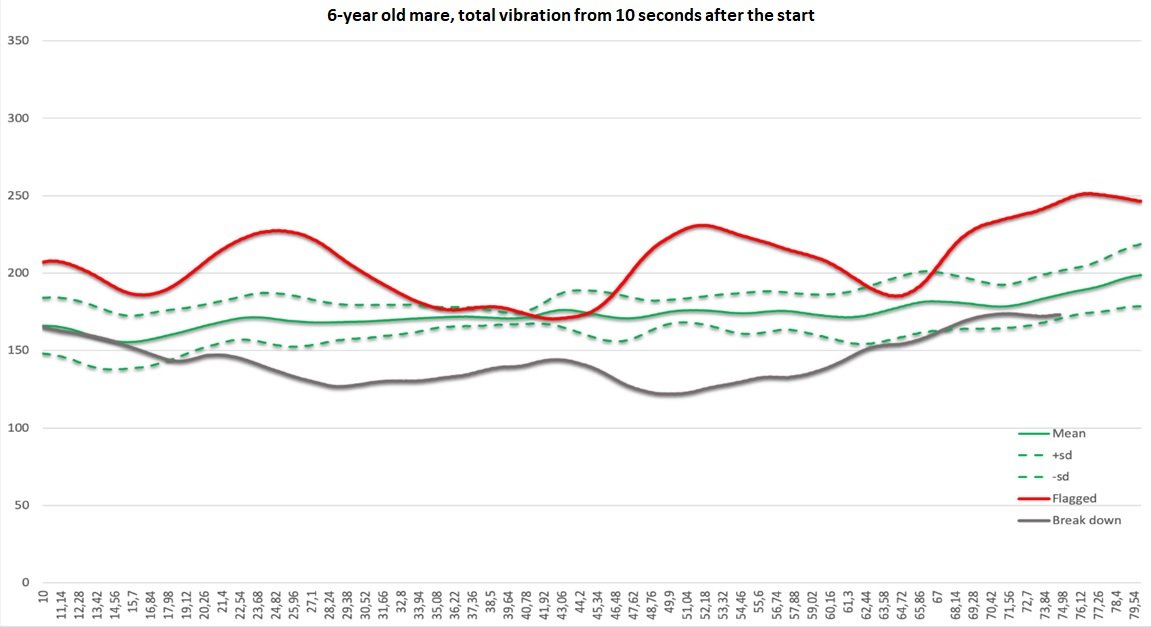

In a blind trial, involving thousands of horses, 27 of which had suffered an injury, this system had generated a warning ‘red-flag’ for no fewer than 25 of them. The green lines in the centre of this diagram are this horse’s normal stride fingerprint; the red line was the deviant pattern that would have flagged up the potential problem, and the grey line was where the horse then sadly injured itself.

The ‘stride fingerprint’ of a racehorse

While the false-positive rate is impressive for such screening tools, another enemy of all predictive technologies is the false positive, and ways need to be found to take action on the findings without imposing potentially unnecessary restrictions on horses’ participation. At present, the StrideMASTER system is typically throwing up three or four red flags for runners at an Australian meeting—more in America.

A study in the spring by the Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council, centering on Churchill Downs, will seek to hone in on true red flags and to develop a protocol for subsequent action. David Hawke, StrideMaster managing director, expands, “Protocols will likely vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, depending on the imaging modalities available. At Churchill Downs, they will have a PET scan, and we will be going straight from red-flag to PET scan.”

There will be other approaches available to regulators involving, for example, discussion with the trainer, a requirement for a clean vet’s certificate, or perhaps for a normal ‘fingerprint’, before racing next.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for continued investment and resource allocation by Racing Authorities. But the will would seem to be there. In Britain, €7M from betting will, over the next three years, fund an extensive array of no fewer than 26 horse welfare projects, covering such matters as education and support for re-homers, analysis of medication data and clinical records, fatalities occurring off the track, ground/going research and obstacle improvement and development. That is a serious statement of intent and an illustration of just how high in importance the welfare of racehorses has now become.

Of course, not all racing nations have the resources to conduct such research. It will be vital, therefore, that the lessons learnt are shared throughout the racing world. In Europe, this is where the EMHF will play a vital role. The federation has always had, as primary aims, education and the adoption of best practice across its membership.

The hope must be that, through all these measures and many others in combination, we can assuage the concerns of the public sufficiently to retain our social licence. But let our ambitions not rest there. We must also strive to shift the debate, to move onto the front foot and invite a focus on the many positive aspects of racing, as an example of the partnership between man and horse that brings rich benefit to both parties.

Elsewhere in this issue, there is a feature on racing in Turkey, and it was the founding father of that country, Kemal Ataturk, who famously said:

“Horseracing is a social need for modern societies.”

We should reinforce at every opportunity the fact that racing provides colour, excitement, entertainment, tax revenues, rural employment, a sense of historical and cultural identity and much more to the human participants. It is also the very purpose of a thoroughbred’s life and rewards it with ‘a life well lived.’

We have a lot more to do, but let’s hope we can turn the tide of public opinion such that people increasingly look at life as did Ataturk.

Racing and breeding in Turkey

Article by Paull Khan

The true scale of the thoroughbred industry in Turkey is surely widely underestimated. Turkey is indeed a big hitter in the racing and breeding world, but much of its activity flies under the international radar. This is perhaps not unsurprising, as Turkish racing is almost completely closed. Of the 3,159 thoroughbred races run in the country annually, all but six are closed to foreign-trained runners. All its races may be broadcast across two television channels, but pictures of Turkish racing are rarely seen abroad; and unless one has a Turkish identity number, one cannot place a bet on those races on the Turkish Jockey Club’s platforms. There are only 10 foreign-based owners in the country, and hardly any of its racehorses were bred anywhere other than in Turkey.

But shine a light on this sunniest and most welcoming of countries, and the vibrancy of the industry is remarkable.

Let’s take breeding first. The latest figures available to the International Stud Book Committee (the 2020 foal crop) show that Turkey is one of the few major thoroughbred breeding nations whose foal numbers have actually grown over the past decade. In 2010, Turkey ranked 15th in the world, in terms of number of foals bred, with 1,500. She now ranks as high as 9th in the world, with 2,103 foals – a 40% increase, no less, at a time when global production is in marked decline. Turkey is, in fact, the fastest-growing major breeding nation in the world. Amongst the top ten, only Ireland’s and Japan’s foal crops have increased over this decade, and both have seen much more modest growth than Turkey’s (15% and 11% respectively). And this Turkish expansion continues: some 2,280 foals were registered in 2022 – a further 8% rise.

Look down a racecard in Turkey, and you would be lucky to see a foreign-bred suffix beside any of the runners’ names. With only 24 out of 3,500+ horses having been foaled outside the country, such a racecard would be something of a collector’s piece. The explanation can be found in a regulation that only allows Thoroughbreds to be imported in the year of their birth. A striking example of the closed nature of Turkish racing, this rule is in place to support local breeders. Another disincentive to buying foreign-breds is that imported horses only receive 75% of the normal prize money.

So, it is domestic production that, almost exclusively, fuels Turkey’s racing product. But that does not mean Turkey is closed to the purchase of foreign bloodstock. Far from it. It has embraced a long-term policy of importing stallions and broodmares strategically to build up the quality of its herd over time. Ten of these stallions are currently owned by the Turkish Jockey Club (TJC) and stand at one or another of their various Stud Farms, which also hosts 47 privately owned stallions. In this way, they are able to offer world-class stallions to their mare owners at knock-down prices.

The most expensive stallion, at least of those whose fees are in the public domain, Luxor, stands at under €8,000.

Current Champion Sire, 1998 Belmont Stakes winner Victory Gallop (CAN), heads the roster of TJC-owned stallions. By the time TJC bought him from America in 2008, he was the sire of multiple-stakes winners. His nomination fee: around €3,000.

2007 Derby hero Authorized (IRE) now stands in Turkey.

A more familiar name to many European Trainer readers among the TJC’s team is 2007 Derby hero Authorized (IRE). Having stood at Dalham Hall, Newmarket and Haras de Logis in France, this sire of six individual Gp1 winners, as well as of Grand National winner Tiger Roll, was acquired by the TJC in 2019, where he stands at some €2,500.

Daredevil (USA), dual Gr1 winner for Todd Pletcher, was purchased by the TJC in 2019.

Daredevil (USA), dual Gr1 winner for Todd Pletcher, was purchased by the TJC in 2019 and stood the 2020 season in Turkey, before returning to his native USA to stand at Lane’s End Farm. However, the TJC have retained ownership of the horse.

Ahmet Ozbelge, General Secretary of TJC, explains the rationale behind this arrangement and the Turkish philosophy on stallion purchases. “After we bought Daredevil, his offspring Shedaresthedevil and Swiss Skydiver performed incredibly well; and we subsequently received many offers from various US stud farms to buy or to stand him. We evaluated all offers and decided not to sell him because of his young age but to stand him at Lane’s End. This is a first for the Turkish breeding sector, and we are glad to be in such a collaboration, to the benefit of the global breeding industry.

“In Turkey, we have very strict criteria for breeding stock purchases from abroad, based on performances of the stallion or the mare in question but also of his/her progeny’s performances. On top of that, we work hard to select the best-suited ones for our country’s specific conditions, including racetrack types, race dıstances, conformation and bloodlines. We also try to build up a good variety in our stallion pool in order to meet the various expectations of our breeders.”

Rising foal numbers are but one example of how Turkey is, in many ways, swimming against the tide. While many countries are seeing a slow decline in their racecourse numbers, Turkey is adding to its roll. Antalya is the latest addition, and it would take a brave punter to bet against further tracks opening their doors in the coming years.

Some €70M will be distributed across Turkey’s national race programme, creating a more than respectable average prize money of €8,200 per race, with owner’s and breeder’s Premiums boosting this to €11,300 per race.

The TJC has no fewer than 2,300 people on its payroll and an outlook that places social engagement higher up the list of priorities than do many racing authorities – perhaps in part to win over the hearts and minds of a populace which tends to be disapproving and to conflate racing and betting. For example, the racecourses offer not only pony and horse rides for the general public but also free equine assisted therapy for the handicapped.

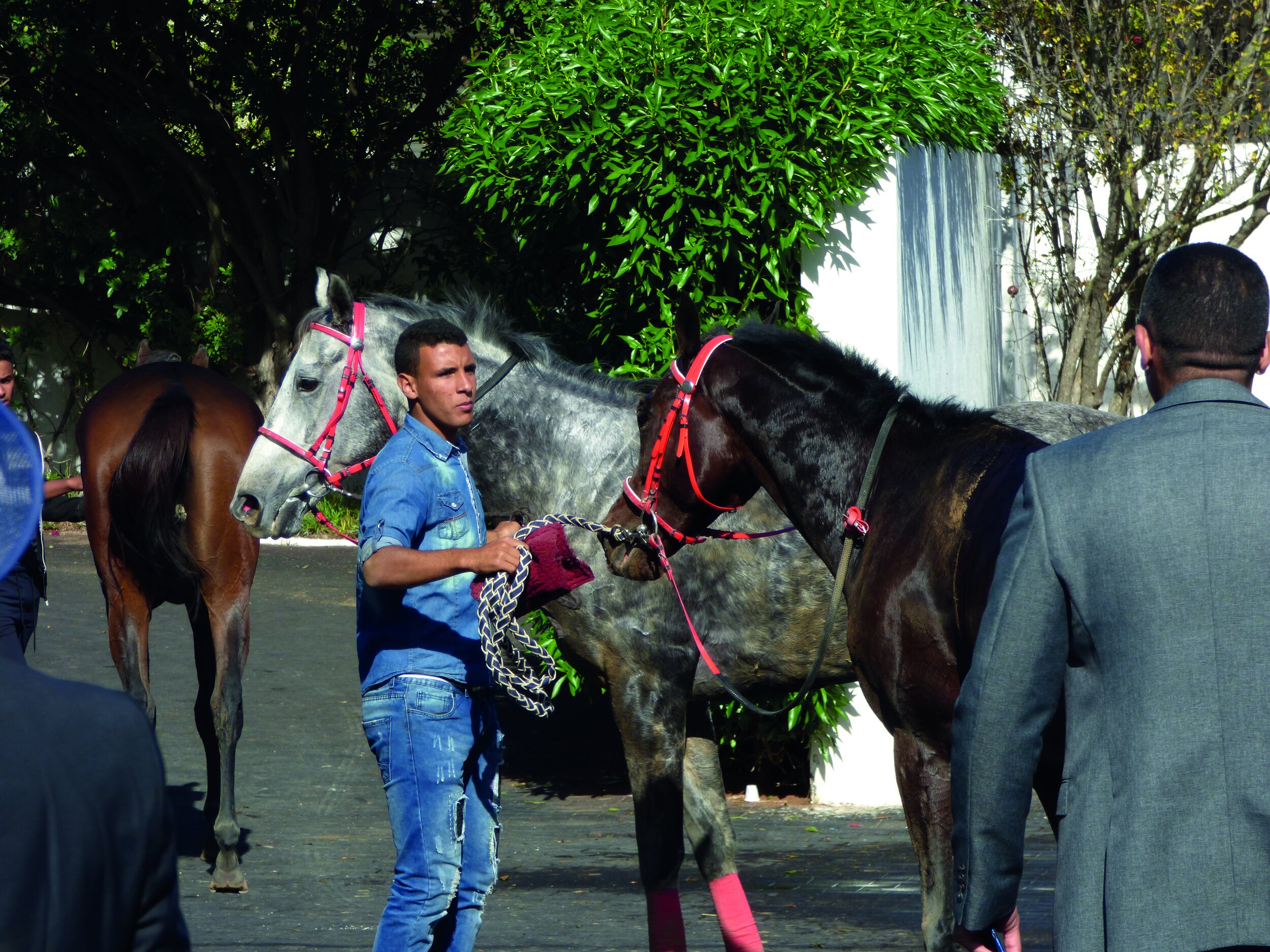

Pony Rides for children and the disabled are routinely offered at Turkish racecourses.

How is an industry of this size sustained? In a word – and unsurprisingly – through betting. Horserace betting has long provided a rich seam of income for the TJC via a formula of which most racing governing bodies can only dream and which is likely to have yielded some €190M in 2022.

By international standards, the Turkish punter gets a raw deal, indeed, with only a 50% return on his stakes. The TJC retains an eye-watering 22% of monies staked, with the remaining 28% slice going to the government. Other income streams for the TJC pale into insignificance: any money from sponsorship, for example, is heavily taxed at a rate of 74%.

Enviable though the TJC’s position may be to many Racing Authorities, it rues the fact that sports betting enjoys yet more favourable treatment. “This is a key point, actually,” explains Ozbelge. “There is a seven-point tax gap between the two sectors in favour of sports betting, which allows them to offer higher payouts. As football is so popular and the most beloved sport in Turkey, we have so many common punters to both racing and football. As a result, they can easily be driven away from the lower payout environment to high payouts.” The paucity of the horseracing return is most evident in single bets, and least apparent in exotics such as the Pick 6 - the Turks’ favourite bet.

To support Ozbelge’s point, sports betting dwarfs horserace betting, accounting for no less than 90% – to racing’s 10% – of legal betting activity. To what extent this is due to the payout differential is difficult to tell. There is also the underlying relative popularity of football which he alludes to; and a further factor may be that, while racing offers pool betting, sports betting is fixed odds. (Exchange betting is outlawed in the country due to integrity concerns).

What is clear is that, with payouts so low, the temptation to bet via the illegal websites is high. “We import race meetings from different countries to prevent Turkish citizens from betting on illegal sites on these races,” continues Ahmet Ozbelge. Even so, it is estimated that the scale of illegal betting at least matches that of legitimate betting.

If European punters and bloodstock agents are likely to find the Turkish landscape somewhat alien, so too might trainers and owners, as the structure is, again, very different.

General Secretary Mr. Ahmet Ozbelge .

There are 795 trainers in the country whose licences allow them to train thoroughbreds or purebred Arabians. There are almost as many Arab races as thoroughbred races, and the prize money is similar. Between the codes, there are over 8,000 horses in training.There is no jump racing nor trotting. A quarter of the race programme is on turf: the majority of races are run on sand with around 10% on a synthetic surface.

To retain their licences, trainers must attend compulsory training sessions, which have heretofore been annual, but are about to be moved onto an ‘as required’ basis. The great majority of trainers train US-style on the racetracks, and each track has plentiful boxes for the local horses-in-training.

But here’s the thing: for the most part, trainers do not charge a fee to their owners, in the manner of those in Western Europe. Their sole remuneration is, rather, a percentage of their horses’ earnings – 5% or 10%. (Some do strike separate agreements with their owners for a fixed salary, but this is not the norm).

The owner, for his or her part, is then responsible for all their horses’ expenses. However, what one might imagine would be a hefty part of those costs – that of the horse’s stable at the racetrack – is again heavily subsidised by the TJC, who charge just €15 to €20 (depending on the racecourse) per annum per box. The owner’s total expenses – including the salary and insurance of the stable staff, feed, bedding, veterinary expenses, etc. – are not far in excess of €1,000 per month. But, lest this information should start a goldrush amongst European owners, salivating at the potential returns on investment, it should be explained that not everyone can become an owner in Turkey. One must have a Turkish residence permit and be able to demonstrate financial sufficiency. This explains why there are only 10 foreign-national owners on the TJC’s books.

Turkey is one of a select few European countries with internationally recognised Group races (the others being France, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, the three Scandinavian countries and Italy). The Gp2 Bosphorus Cup (3yo+, 2,400m/12f) and Gp3 Topkapi Trophy (3yo+, 1,600m/8f) are the richest, worth north of €150,000. The Istanbul Trophy (Gr3), for fillies and mares, makes up its Group-race trio. All are run over the turf course at Istanbul’s impressive Veliefendi racetrack – the main centre and flagship of Turkish racing. They are joined by the International Thrace Trophy (turf) and International France Galop FRBC Anatolia Trophy (dirt), both of which are international Listed Races. The only other open race takes place at the nation’s capital, Ankara, being the Queen Elizabeth II Cup for two-year-old thoroughbreds; but this has never attracted any European runners.

The start of the Gazi Derby.

Richer than all of these is the Gazi Derby, a €330,000 race run over the classic mile and a half in late June.

Veliefendi is not, however, Turkey’s oldest racecourse. That honour goes to Izmir, at which members of the EMHF’s Executive Council spent a most enjoyable day’s racing in September, following this year’s annual meeting.

The window into Turkish racing has for some years been its International Festival, at which all Veliefendi’s international races are run. Its wide – up to 36 metres – turf track and attractive prize money once proved highly popular with foreign trainers, who frequently made the journey to Istanbul in September. The Topkapi Trophy , for example, saw a 10-year unbroken spell of foreign-trained winners, with Michael Jarvis, Mike De Kock, William Haggas, Richard Hannon Snr., Kevin Ryan, Andrew Balding and Sascha Smrczek all making the scoresheet. However, COVID has brought about a sea-change in behaviour, and there has not been a foreign-trained winner of any Turkish Group race for the past five years.

EMHF ExCo members at Izmir Racecourse.

Inevitably, the quality of the race fields has suffered. In 2022, the Topkapi Trophy had to be downgraded from Gp2 as a result, and the pressure on all the Turkish Group races is unlikely to ease unless and until the raiders can be enticed back.

Turkey’s governance structure is also a little unusual. The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry plays a very hands-on role when it comes to regulation – appointing the Stewards and taking responsibility for race day operations and doping control. The Jockey Club itself operates under the provisions of a triad agreement with the Ministry of Agriculture and the Turkish Wealth Fund, which is the holder of the licence for racing and betting in Turkey.

The TJC prides itself on its not-for-profit status and ethos. Ozbelge explains: “Having a centralised governing system of the racing, breeding and betting activities by a nonprofit organisation with a non commercial approach, but rather a ‘horsemen’ one, with a main goal being to develop [the] racing industry by improving the racehorse breed in the country, has many advantages. This system supports the horse owners and breeders by offering them world-class stallions for very reasonable covering fees, offering boarding and veterinary services of high quality for minimum possible costs to them. Also, supplying the industry with well-educated jockeys in its own Apprentice School and delivering live broadcasting of all races through two TV channels and so on.

“But when one thinks about the cost of all of these investments as well as all the facilities that the Club has to operate with its staff of 2,300 experienced people, with betting revenue being its sole income, it’s easy to see that this has many challenges that come with it. But the main challenge is the unfortunate general perception of ‘gambling’ of our beloved sport, which is considered the king of sports and the sport of kings throughout the world. With a little bit of support or at least a ‘fair approach’ in comparison to betting on other sporting activities, Turkey has great potential to be a major player in the world league of horse racing.”

So, what are the prospects of the veil over Turkish racing being lifted?

There is hope of a new media rights deal which promises to bring pictures of Turkish races to an international audience. But those hoping to see Turkey adopt the policy of most of its European neighbours – namely that of having open races – are likely to be disappointed. Ozbelge again: “As Turkey is not in close proximity to major racing countries in Europe, horses cannot travel frequently by road as between central European countries, but only by air in order to participate in international races. As one can imagine, this is quite costly, and in order to attract some horses from abroad, the prize money is the key factor here. So, it all comes down to the economics of the industry and of the country for sure. We do plan and hope to have more international races, but we can realise it only if and when we have the right infrastructure and dynamics for it.”

International racing returns to Morocco

Article by Paull Khan

Casablanca will host the latest of its well-established and handsomely endowed International Thoroughbred Race Days. Entries for the four races, which are run on Saturday the 19th of November, close at the end of October.

Headlining is the €110,200 Grand Prix de la SOREC, one of the international Defi du Galop series of events, run over 2400m/12f for 3yo’s and up. The support card comprises a 1750m/8.75f event for 3yo fillies (€64,300), a race for the 3yo colts over 1900m/9.5f (€55,100) and a 1750m/8.75f for the staying 2yo (€25,700). All races are run on the dirt track. Entry fees are around one percent of the race fund.

SOREC (the Moroccan racing authority) is eager to see the festival get fresh impetus after the sad interruption due to COVID. Keen to encourage international participation, it will be putting on a plane to transport runners from a central European location (exact departure point to be determined), awarding travel allowances of up to €3,000 per horse, meeting the costs of flights and accommodation for the owner, trainer and jockey and hosting a gala dinner. Stable staff will be put up at the nearby training centre, where the visiting horses will be stabled.

“Since 2015,” explains Hicham Debbagh, SOREC’s deputy general manager in charge of horse racing, “our objective was to install the Morocco International Meeting in the international calendar, through attractive prize money and free air transport, in order to guarantee the best reception conditions for horses and professionals. Prior to COVID, things were progressing nicely, and we were attracting good horses from England, France, Libya, Netherlands, Oman, Poland, Qatar, Spain, Syria and UAE. Now that travel has opened up again, we look forward to building our festival back up as an international destination. Welcome to Morocco!”

Anfa Racecourse is an oasis of calm and beauty in the sprawling metropolis that is Casablanca. Trainers might well consider a Moroccan raid. Prize money extends down to fifth place, and the average field size for the four races in (pre-COVID) 2019 was 11. At the same time, it provides connections with the chance to experience racing in a nearby country with a fascinatingly distinct culture, and it will be helping inject the necessary quality of the runners to enable Morocco to achieve its dream of acquiring its first Black Type race.

First European Pony Racing Association meeting in Budapest

Article by Paull Khan

Those in charge of pony racing travelled to Budapest from all over Europe to attend the inaugural annual meeting of the European Pony Racing Association (EPRA) on September 11th. Representatives from Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Great Britain, Hungary, Norway, Slovakia and Sweden had, the previous day, witnessed three pony races that kick-started the quality thoroughbred card at Hungary’s sole track, Kincsem Park. They were universally impressed at the professionalism of the pony racing, the hospitality and the great strides which Kincsem Park has made in recent years. It is a very different racecourse from the one that hosted an early EMHF meeting in 2013 and as striking an example of diversity as one can find. Today, every square metre of the track’s footprint is put to productive use. In addition to the flagship thoroughbred racing, there is greyhound racing, trotting, a training centre, show jumping, four-in-hand driving and more. There is even a rugby pitch inside the greyhound track!

Increased internationalisation of pony racing, with the best young riders having the opportunity to experience race-riding in other countries, is an aim of the EPRA, and it was pleasing to witness history being made. Czech youngster Sophy Bodlakova became the first foreign-based winner of a Hungarian pony race when she scored on her pony Saman!

While for some EPRA member countries, such as France, Sweden and Britain, pony racing is a well-established pursuit; for some, it is a very new endeavour, and for others yet, it is something to be established in the near future. The imparting of knowledge and identification of best practice will therefore be central to the fledgling association.

Slovakia’s experience bears witness to the fact that countries need not wait for long, after setting up a pony racing structure, to see the benefits begin to flow, in the shape of new jockeys. It was only last year that the first pony races took place at Bratislava racetrack, but from the alumni of that first cohort, there are this year no fewer than four amateur riders licence-holders. For those many countries experiencing difficulties in sourcing competent race riders, a pony racing structure is a must-have.

At the EPRA meeting, a minute’s silence was observed in honour of Jack de Bromhead, who tragically lost his life in a pony racing incident in Ireland.

For many delegates, it was the first experience of pony racing outside their own countries. Next year, the EPRA has accepted a kind invitation from France to host.

Botond Kovacs, head of pony racing in this year’s host country, commented: “We have been thrilled to host the first European Pony Racing Association meeting. The rise in profile of pony racing is very refreshing to see. The European Pony Racing community is taking shape and it feels like we’ve been put on the map—a map that the world of racing has a keen eye on.”

Racing in Switzerland - it's not just about racing on snow!

Article by Paull Khan

Think of racing in Switzerland, and the fabulous White Turf meeting on Lake St. Moritz probably comes to mind. This is no surprise, of course. The EMHF was fortunate to hold its General Assembly there in 2015, and for many of our delegates, including your columnist, it remains among the most memorable racing adventures of all. But there is so much more to racing in that country.

Sadly, St Moritz’s little sister track, which provided racing on the frozen lake at Arosa, is no longer with us. Weather conditions in recent years meant that there had become a worse than even-money chance of abandonment—a situation that was just not financially sustainable.

But the full roster of Swiss thoroughbred tracks still extends to seven. (Although one of the tracks, at Fehraltorf, which had upheld a 75-year tradition of racing over the Easter holiday, remains in a state of hiatus following an altercation last year with a neighbour farmer, who took the dramatic and disruptive decision to plough up the racing surface.)

Jump racing is the primary focus at Aarau and Maienfeld, while the flat dominates at Zurich-Dielsdorf, Frauenfeld (home of the Swiss Derby) and at the track that is the financial powerhouse of Swiss racing, Avenches.

This August saw celebrations for the 150th year of the Zurich race club, which coincided with 50 years of its current racecourse, at the small nearby town of Dielsdorf. A two-day festival was crafted, during which the 1500-metre, pancake-flat turf track staged 14 races: nine thoroughbred flat, two trotting and three pony. This left-hand track also boasts a jump course, but this is used infrequently these days.

Interwoven with the races, there was an appearance of the 250-year-old Bernese Dragoons, a mesmeric display from world-renowned Jean-Francois Pignon’s ‘free dressage’ horses, after-racing musical acts and, notably, a parade of former equine stars of Swiss racing showing off their expertise in new-found careers. Aftercare has long been a feature of Swiss racing. Horses tend to stay in training for longer than the norm on the flat, allowing the public to build up the kind of rapport with them normally associated with jump racing. In addition, they tend to race more frequently than in most countries, averaging nearly eight starts annually and this helps to buoy field sizes and makes for attractive, competitive racing generally.

The substantial crowds were engaged and relaxed, and it all made for a wonderfully rewarding racing experience.

When it comes to funding, Swiss racing is swimming against the tide, in many ways akin to the experience in Belgium, described in the last issue of Trainer. This is because, with one principal exception, there is no opportunity for people within or outside the country to place bets on Swiss races unless they are on-track. The twin State-installed institutions (one French-language, the other German), which between them enjoy a betting monopoly, decline to include domestic racing within their product mix. The exception is Avenches, where the bulk of the races has been taken on by the French betting giant PMU, are shown on the Equidia channel, and are available to Swiss and French citizens to bet on, in cafes, bars and kiosks and online. (In 2022, a few PMU races were also held in Frauenfeld and Dielsdorf). The commission from this betting activity is vital to Avenches and also helps support Swiss racing generally, but the other Swiss tracks rely critically on donations and sponsor contributions.

Unsurprisingly, the scale of the industry has suffered a worrying contraction. What had been a slow but steady reduction in the numbers of owners, horses, races and prize money between 2015 and 2019 accelerated dramatically in the COVID year of 2020. Over the past seven years, prize money has halved, and the numbers of horses and owners have reduced by 51 percent and 48 percent, respectively.

The Swiss race programme is heavily weighted towards staying races. While Handicaps are out of bounds to foreign-trained runners, they only constitute a modest proportion of the race programme and all conditions races are open. Average prize money per race remains very respectable, at nearly €10,000. The Grand Prix von St Moritz is, at €100K, clearly the nation’s richest race. Other significant prizes include the Grand Prix d’Avenches (€20k for 3yo+, weight-for-ages, 2400m/12f), Zurich’s Grand Prix Jockey Club (€50k for 3yo+, weight-for-age, 2475m/12f+), and the Swiss Derby (€50K). The country’s main jump race is the €35K Grand Prix of Switzerland, run over (4200m/21f) in beautiful surroundings at Aarau in September with a limited weight range of just 3kgs.

For five years, between 2014 and 2018, both the Grand Prix d’Avenches and the Grand Prix Jockey Club boasted Black Type. Regrettably, neither managed to maintain the strict ratings threshold required of such races in Europe. Fresh hope has been generated by the new scheme, agreed this year, whereby EMHF member countries without a Black Type race can apply for such recognition for a single, flagship event which is allowed a rating 5lbs lower than normal. There is a real desire that one or another of these races can clear this lowered bar but, as is normally the case, this is likely to hinge on their attracting foreign-trained runners rated 95+ on the international scale. And, considering the decent prizes, foreign-trained runners are relatively thin on the ground, accounting for under five percent of starters. British and German raiders are attracted to the snow, Czech runners to some of the jumps races, but foreign runners on the flat have been in single figures over the past two years.

There was, in fact, a third milestone included within the Zurich celebrations: the tenth anniversary of Horse Park Dielsdorf. The Horse Park brings together the racing and equestrian worlds in a way which could surely be gainfully replicated in many more parts of Europe. Alongside the racetrack and training barns housing 150 horses, there are FEI-standard facilities for show jumping and dressage. A recent addition, completed within the past year, is a large stylish building which, in its restaurant configuration, comfortably seats 250 with a fine view of the racing. Various facilities around the complex are available year-round to the general public for hire. In investing some €8M into this project, Race Club President Anton Kraeuliger has demonstrated both a recognition of the importance of sweating the asset that is the racecourse and an enduring belief in Swiss racing. Let us hope that this confidence is well-placed and that racing in this most beautiful of European countries, can look forward to a thriving future.

News from the European Mediterranean Horseracing Federation 2019 General Assembly

By Paull Khan, PhD.

To many, Norway is the land of the midnight sun or that of the Northern Lights. But to the race-fan, these meteorological mysteries are incidental—Norway is, first and foremost, home to that enigma, the Whip-less Race.

This year, the EMHF’s General Assembly ‘roadshow’ returned to Scandinavia, where the Norwegian Jockey Club hosted our meeting at the country’s sole thoroughbred racetrack, Ovrevoll, after which delegates were privileged to experience the joyous and colourful processions of Norway’s Constitution Day and also witness firsthand the running of a full card without crops—of which more later.

Our meeting broke fresh ground in a number of ways. For the first time, the press was represented, and a number of commercial enterprises (Flair - manufacturers of Nasal Strips, RASLAB - international distributors of racing data and rights, and Equine Medirecord, who supply veterinary compliance software) joined the social programme and mingled with the administrators. The number of presentations was also increased, from which it was made apparent to everyone, if we did not know it before, that the range of threats we face as a sport is diverse indeed.

Illegal Betting

Amongst these threats is one which to date has had far greater impact in Asia, but whose tentacles are increasingly taking Europe into their grasp. The enemy is illegal betting, on which Brant Dunshea, Chief Regulatory Officer of British Horseracing Authority, gave a presentation. Recently co-opted to bring a European perspective to a task-force set up by the EMHF’s equivalent in Asia—the Asian Racing Federation—Dunshea was shocked at the sheer size of the problem.

Defining ‘illegal betting’ as including betting which takes place in an unregulated environment, (e.g., an off-shore operation which was contributing nothing to the sport and was under the regulatory control of neither government nor racing authority), he presented figures which showed that illegal betting in six Asian countries—predominantly using the betting exchange model—was vast in scale; was increasing faster than its legal equivalent; was funding criminal activities including through money laundering; attracted disproportionately higher rates of problem gambling; was poorly understood by governments and racing authorities and was presenting new challenges for regulators in relation to dealing with race corruption. A decrease in the number of suspicious betting investigations on British betting exchanges had been experienced. It now seemed likely that some of this activity had simply shifted to the illegal and unregulated markets.

This is an issue that Europe cannot afford to ignore. The British Horseracing Authority has committed to replicate the Asian research which will seek to quantify the scale of betting on British racing across illegal and unregulated platforms; and Dunshea took the opportunity to seek other volunteers from other EMHF countries to join in this effort. The task-force aims to produce a plan of best practice to identify and tackle this problem for the use of racing authorities.

Liv Kristiansen, Racing Director of the Norwegian Jockey Club, has been elected to the EMHF's Executive Council.

Dunshea pointed to the salutary conclusion that increasing regulation and taxation of the legal market was not necessarily the answer to the problem and risked the unintended consequence of causing punters to migrate to illegal markets, with their lower margins and (for many countries) a wider and more attractive range of available betting options. Key in the battle will be to engage governments in this discussion, ensure their understanding of the scale of the problem and the interconnectivity between policies in regard to legal betting and the propensity to bet through illegal channels, and try to find a balanced tax burden, alongside sufficient laws and law enforcement effort, to snuff out this noxious menace.

Gene Doping

Gene doping is no longer something from the realms of science fiction but is practiced today. Simon Cooper, co-chair of the European and African Stud Book Committee explained: “DNA can be inserted, substituted, deleted any number of ways—a bit like cut-and-paste on your computer. Gene editing kits can be bought on the internet”. He gave a salutary example of its potential effects. “Mice normally will run for about 800 metres before they’ve had enough. After some mice were injected, in an experiment in Australia, with the stamina protein PEPCK, and genetically manipulated, they ran six kilometres”. The potential to inflict great damage on the sport of horseracing is obvious, and we should be grateful that the state of vigilance among the international racing and breeding authorities is high, with excellent work particularly being carried out in Japan as well as Australia. There is no evidence of nefarious gene doping of racehorses to date—and indeed no belief that it has—but part of the problem is that we cannot say unequivocally that it has not happened, because there is as yet no test to determine whether or not a horse has been subjected to this technique. This is the main focus of research, which will, if and once successful, be made available to Stud Books, as gatekeepers of the breed and racing authorities around the world. “Once DNA is changed, those changes are passed on”, added Cooper, so the more time that passes before detection, the greater the problem. Prevention, rather than retrospective identification, must therefore be the aim. It is believed that the most likely point at which genetic engineering would be carried out on a horse would be between conception and birth. A takeaway message from Cooper was that the racing world should shout loudly and clearly that its authorities have anticipated, and are prepared for, gene doping. Making those who would seek to cheat aware of this fact should, in and of itself, dissuade them from so doing and thereby reduce the risks of this nightmare ever becoming a reality.

Jockeys’ Mental Health…

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Marketing priorities across European racing

By Dr Paull Khan

MARKETING PRIORITIES ACROSS EUROPEAN RACING

Three issues that were commonly identified as challenges facing horseracing across Europe at the EMHF’s recent Seminar on “Marketing and Educational Initiatives”:

A worrying shortage of jockeys and stable staff

The broad requirement to raise racing’s profile and appeal; to grow the fan-base and drive ownership

A growing need to win over the hearts and minds of the wider community

Essentially, the marketing of our sport is handled often at a local racecourse or at a national level. Examples of international collaboration exist but are very much the exception. Thus, Racing Authorities, particularly in the “smaller” racing nations, are often working in isolation with limited opportunity to bounce ideas off each other or compare notes as to what has worked and what has not.

It was with this in mind that we invited EMHF members to gather together, to outline the current state of the racing industry in their respective countries and to present on one or two recent initiatives they had introduced. SOREC, the Racing Authority of Morocco, had kindly offered to host. At their National Stud in Bouznika in November we received presentations from countries as diverse, in racing terms, as Belgium, Czech Republic, Great Britain, Greece, Ireland, Morocco, Sweden and Turkey. Delegates from Poland and Spain also attended.

22 delegates from 10 countries attend the EMHF's Marketing & Educational Initiatives Seminar

The degree of commonality among the concerns of Racing Authorities big and small proved striking, and it made the various ideas and approaches being adopted to address them all the more fascinating and relevant.

The difficulty in finding jockeys was highlighted in several presentations. We need not look far, of course, for one reason for this: we live in times when the average weight of our species is rising, yet the same is not the case for the thoroughbred—limiting scope simply to increase the weights allotted. But there are doubtless several other factors at play here: a growing dislocation of the populace from the countryside and from animals, as well as a general decline in the profile and appeal of horseracing (among so many other traditional pursuits), etc.

Jockey shortage and development is one of the key issues facing the Belgian Galop Federation (BGF). Belgian racing is operating at a fraction of its scale a century ago: where there were a dozen racecourses then, there are but three today; where racing took place on a daily basis, there is now a fixture per fortnight. There are just 320 thoroughbreds in training and only 24 jockeys, with two apprentices. The BGF has adopted a combination of targeting those with a proven interest in riding, but not necessarily race-riding, with an innovative approach to jockeys’ training. Pupils at Belgium’s Riding and Horse Care School receive lectures on aspects of the jockey’s life and exposure to the mechanical horse. It is evident from many sports that few things encourage the recruitment of youngsters more effectively than having a home-grown star, and the development of Belgium’s riders has been a central concern of the BGF, which does not have the luxury of a jockey school and has struggled with the expense of sending pupils to such a facility abroad. Their solution: to bring the mountain to Mohammed. Arc- and Derby-winning jockey John Reid has been engaged to provide coaching to jockeys of all levels of experience. Over three days, twice a year, these riders gain the benefit of Reid’s experience, with video material and time on the simulator.

The Czech Jockey Club (CJC)—which, by the way, will reach its centenary in March—is an organisation adept at making its money go a long way. Despite the absence of any statutory funding from betting—41% of prize money is self-funded by the owners and 56% provided by sponsors—Czech racing still boasts 11 racecourses and some high-quality horses. Indeed, in recent years, the 1,000 or so horses in training have collectively picked up more money from foreign raids than the total available to them at home. So, when the CJC received a grant from their Ministry of Agriculture for a project to recruit children into the sport and particularly into their jockeys’ ranks, a great deal was done, despite the grant only amounting to less than €5,500. They targeted 8th and 9th grade children, their parents and educational advisors, in a combination of outreach visits and receiving groups of students, either at their racing school or during race meetings. The initiative garnered television coverage, and extensive use was made of social media to publicise it. How successful this project has been will become evident in March—the deadline for applications to the racing school for youngsters leaving school that summer.

Britain’s European Trainers’ Federation representative, Rupert Arnold, broadened the focus to the related issue of stable staff recruitment and retention. The difficulties being faced in Britain currently had been, he explained, a major driver in his introduction, as the chief executive of the National Trainers Federation, of a new Team Champion Award last year. With the aim of rewarding good management in a trainer’s yard—a standard dubbed “The Winning Approach” was devised, covering many aspects of the way a trainer runs their business. To encourage adoption of the standard, an award, (or, more accurately, two awards—one for larger yards and one for those with up to 40 horses) was put up, with the assistance of sponsorship from insurers Lycett’s. Importantly, these awards were—as their name suggests—for the whole team rather than the trainer alone. The amount of £4,000 went to the winning stable, and the yards that entered were asked to say how they would spend their winnings, if successful. So that the benefits are spread wider than the two victorious stables, a star rating system has also been introduced, providing trainers with a promotional tool. It is hoped that these Team Awards will create a virtuous circle, with more yards adopting best practice, thereby creating a better working environment for staff, increasing staff satisfaction and, ultimately, retention.

TO READ MORE —

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

Second careers for racehorses can bring life-changing rewards for the humans who meet them

By Paull Khan

Festival was a horse brave enough to conquer the obstacles and emerge victorious in the fearsome Velka Pardubicka steeplechase. Peopleton Brook was so hardy, he contested 93 races for Grand National-winning jockey-turned-trainer, Brendan Powell, winning nine of them and being placed a further 17 times. What do these hardened racehorses have in common? They have both given valuable service in the young, fascinating and increasingly widespread endeavour of Equine Assisted Activities such as Hippotherapy.

Owners, as well as the public at large, would appear to be ever more concerned with what should become of their racehorses once they have retired from the track. And these activities, which are held to bring profound benefits to people in many different circumstances, could increasingly provide an answer – and one as rewarding for the erstwhile owner as for the clients or patients with which their horse interacts.

What, exactly, are ‘Equine Assisted Activities (EAAs)’? Look, and you will find a myriad of similar terms in use: Equine Facilitated Learning, Equine Assisted Psychotherapy, Therapeutic Riding…the list goes on. Each defined differently – and sometimes conflictingly – by different authors: the hallmark, of course, of an emerging and youthful field.

Hippotherapy, despite the breadth of its literal meaning – ‘treatment with the horse’ – has come to refer to a very specific strand of EAA. In Hippotherapy, the treatment involves the horse being ridden. The Oxford English Living Dictionary defines the term thus: The use of horse riding as a therapeutic or rehabilitative treatment, especially as a means of improving coordination, balance, and strength. The predominant focus is on those with physical disabilities, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, etc..

But many manifestations of EAA are geared primarily to helping with non-physical issues and these typically involve little or no riding. Interaction with the horse can take many forms, including handling, grooming and lungeing. So, too, the methodologies employed. Some are one-to-one and focus on personal issues; most are group-based and look at more general concepts, such as trust, assertiveness, self-confidence and self-esteem. Many involve trained professionals such as psychotherapists.

But all are based on the core belief that, for many reasons which the Counselling Directory sets out well, the horse is especially suited to this type of work. Its very size can initially be daunting, so, for many, to overcome this and establish a relationship of trust and control is a profound achievement. As a prey animal, it is quick to interpret body language and to mirror behaviour, responding positively to a calm, confident approach. As a herd animal, it will frequently want to be led and to create bonds – the bonds between man and horse can be exceptionally powerful.

And the range of claimed benefits and beneficiaries is broad indeed. Prisoners, ex-servicemen and -women with PTSD, those on the autistic spectrum, children with ADHD, those deemed ‘at risk’, schizophrenics and those exhibiting a number of other behavioural and psychiatric disorders.

What is striking is that programmes of one sort or another are going on in many, many countries across Europe and beyond. In Prague, for example, the Czech State Psychiatric Hospital boasts a hippotherapy department called BOHNICE. Milan’s principal Hospital has had a hippotherapy unit for over 30 years.

On occasion, there is some involvement of the racing industry. For example, the Moroccan racing authority, SOREC (Société Royale d'Encouragement du Cheval) co-founded a hippotherapy programme aimed at people with special needs. In Scandinavia, betting companies, through the Swedish-Norwegian Foundation for Equine Research to which they contribute, funded a study of the efficacy of Equine-Assisted Therapy on patients with substance abuse patients.

A most impressive example of racing involvement is from Turkey. Here, Equine-Assisted Therapy Centres can be found, courtesy of the Turkish Jockey Club, at their seven racetracks, each offering entirely free courses to children with physical disabilities or mental and emotional disorders. To date, over 3,500 children have benefitted from the scheme, described as ‘one of the most important social responsibility projects of the Jockey Club of Turkey’.

TO READ MORE EMHF NEWS --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

EMHF - Might technological advance lead to greater international co-operation in racing?

By Dr. Paull Khan

The Asian Racing Conference (ARC) was first staged 58 years ago and attracted less than 70 delegates. These days, it is held biennially, and the 37th ARC returned to Seoul this year – the third time it has been Korean-hosted.

The Racing

Prior to the conference, delegates had the chance to attend Korean Derby Day at Seoul Racecourse Park. Prize money for the 11-race card averaged over €100,000 per race, with the Derby itself – won by 2/1 favourite Ecton Blade, a son of imported Kentucky-bred stallion Ecton Park – worth €640,000.