Ulcer medication: are the products to treat that different?

By Celia Marr

Stomach ulcers are not all the same

Racehorse trainers and their vets first began to be aware of stomach ulcers over 20 years ago. The reasons why we became aware of ulcers are related to technological advances, which produced endoscopes long enough to get into the equine stomach. At that time, scopes were typically about 2.5m long and were most effective in examining the upper area of the stomach, which is called the squamous portion. Once this technology became available, it was quickly appreciated that it is very common for racehorses to have ulcers in the squamous portion of the stomach.

Fig 1. The equine stomach has two regions: the upper region is the squamous portion and the lower region is the glandular portion. The squamous portion is lined by pale pink tissue which is susceptible to acid damage. The glandular portion is lined by darker purple tissue. Acid is produced in this region. In this horse, the stomach lining is healthy and unblemished. The froth is due to saliva which is continuously swallowed.

The equine stomach has two main areas: the squamous portion and the glandular portion. The stomach sits more or less in the middle of the horse, immediately behind the diaphragm and in front of and above the large colon. Imagine the stomach as a large balloon with the oesophagus—the gullet—entering halfway up the front side and slightly to the left of the balloon-shaped stomach and the exit point also coming out the front side but slightly lower and to the right side. The tissue around the exit—the pylorus—and the lower one-third, the glandular portion, has a completely different lining to the top two-thirds, the squamous portion.

The stomach produces acid to start the digestive process. Ulceration of the squamous portion is caused by this acid. Like the human oesophagus, the lining of the squamous portion has very limited defences against acid. But, the acid is actually produced in the lower, glandular portion. The position of the stomach is between the diaphragm, which moves backwards as the horse breathes in and the heavy large intestine which tends to push forwards as the horse moves. During exercise, liquid acid produced at the bottom of the stomach is squeezed upwards onto the vulnerable squamous lining. It makes sense then that the medications used to treat squamous ulcers are aimed at blocking acid production.

Lesions in the glandular portion of the stomach are less common than squamous ulcers. The acid-producing glandular portion has natural defences against acid damage including a layer of mucus and local production of buffering compounds. At this point, we actually know relatively little about the causes of glandular disease, but it is becoming increasingly obvious that disease in the glandular portion is very different from squamous disease. Often, it is more difficult to treat.

Fig 2. This horse shows signs of discomfort. She carries her head low, her ears are back a little, and the muscles of the face are clenched, affecting the shape of the nostrils and eye.

Stomach ulcers can cause a wide range of clinical signs. Some horses seem relatively unaffected by fairly severe ulcers, but other horses will often been off their feed, lose weight, and have poor coat quality. Some will show signs of abdominal discomfort, particularly shortly after eating. Other horses may be irritable—they can grind their teeth or they may resent being girthed. Additional signs of pain include an anxious facial expression, with ears back and clenching of the jaw and facial muscles and a tendency to stand with their head carried a little low.

Assessing ulcers

Ulcers can only be diagnosed with endoscopy. A grading system has been established for squamous ulcers, which is useful in making an initial assessment and in documenting response to treatment.

Grade 0 = normal intact squamous lining

Grade 1 = mild patches of reddening

Grade 2 = small single or multiple ulcers

Grade 3 = large single or multiple ulcers

Grade 4 = extensive, often merging with areas of deep ulceration

Fig 3. Grade 1 squamous ulcers which are mild patches of reddening.

Fig 4. Grade 2 squamous ulcers—there are several of these, but they are all small.

Fig 5. Grade 3 squamous ulcers—these are larger, and there are several.

Fig 6. Grade 4 squamous ulcers—there are extensive deep ulcers with active haemorrhage.

Although it is used for research purposes, this grading system does not translate very well to glandular ulcers where typically, lesions are described in terms of their severity (mild, moderate or severe), distribution (focal, multifocal or diffuse), thickness (flat, depressed, raised or nodular) and appearance (reddening, haemorrhagic or fibrinosuppurative). Fibrinosuppurative suggests that inflammatory cells or pus has formed in the area. Focal reddening can be quite common in the absence of any clinical signs. Nodular and fibrinosuppurative lesions may be more difficult to treat than flat or reddened lesions. Where the significance of lesions is questionable, it can be helpful to treat the ulcers and repeat the endoscopic examination to determine whether the clinical signs resolve along with the ulcers.

Fig 7. The glandular tissue around the pylorus (or exit point) has reddened patches. This is of questionable clinical relevance, and many horses will show no signs associated with these lesions.

Fig 8. There are dark red patches of haemorrhage in the glandular tissue of the antrum—the region adjacent to the pylorus—which is the dark hole toward the bottom of this image.

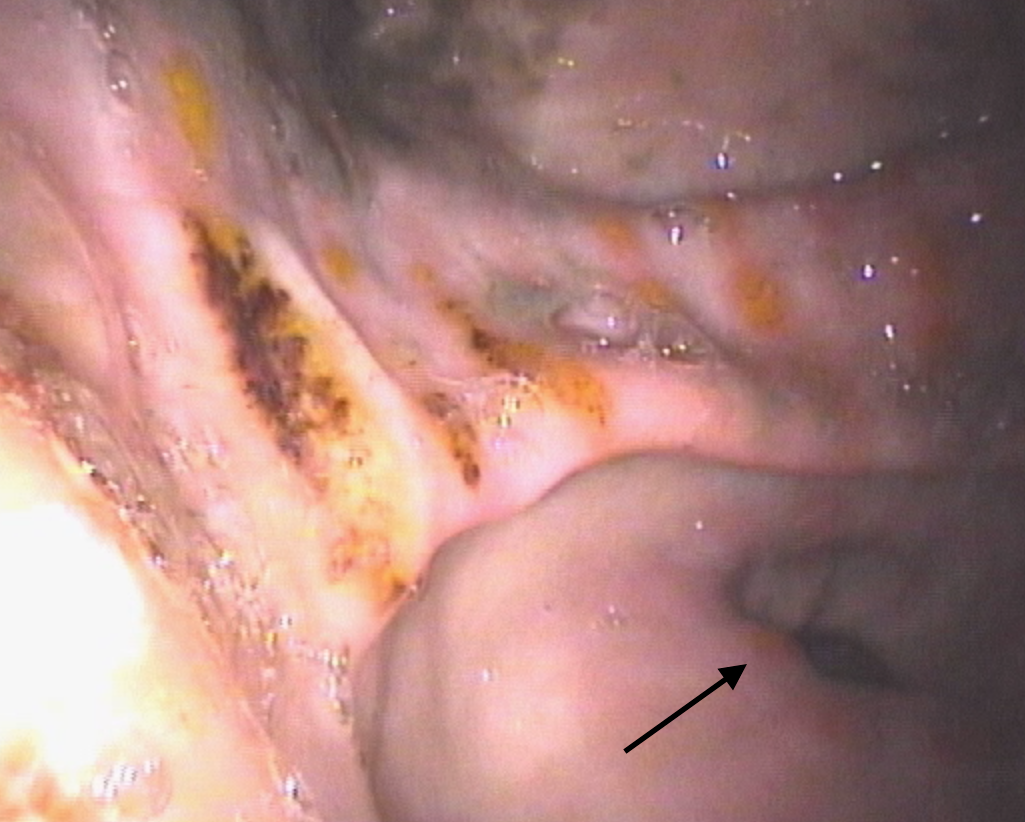

Fig 9.This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. There are depressed suppurative (yellow) areas several of which also have haemorrhage. Nearer to the pylorus there is reddening and raised, swollen areas (arrow).

Fig 10. This horse has moderate to severe glandular disease. The majority of lesions are depressed and haemorrhagic.

Medications for squamous ulcers

Because of the prevalence and importance of gastric ulcers, Equine Veterinary Journal publishes numerous research articles seeking to optimise treatment. The most commonly used drug for treatment of squamous ulcers is omeprazole. A key feature of products for horses is that the drug must be buffered in order to reach the small intestine, from where it is absorbed into the bloodstream in order to be effective. Until recently only one brand was available, but there are now several preparations on the market and researchers have been seeking to show whether new medicines are as effective as the original brand. There is limited information comparing the new products, and this information is essential to determine whether the new, and often cheaper, products should be used.

A team of researchers formed from Charles Sturt University in Australia and Louisiana State University in the US has compared two omeprazole products given orally. A study reported by Dr Raidal and her colleagues, showed that not only were plasma concentrations of omeprazole similar with both products, but importantly, the research also showed that gastric pH was similar with both products and both products reduced summed squamous ulcer scores. Both the products tested in this trial are available in Australia and, although products on the market in UK have been shown to achieve similar plasma concentrations and it is therefore reasonable to assume that they will be beneficial, as yet, not all of them have been tested to show whether products are equally effective in reducing ulcer scores in large-scale clinical trials. Trainers should discuss this issue with their vets when deciding which specific ulcer product they plan to use in their horses.

Avoiding drugs altogether and replacing this with a natural remedy is appealing. There is a plethora of nutraceuticals around and anecdotally, horse owners believe they may be effective. One such option is aloe vera that has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and mucus stimulatory effects which might be beneficial in a horse’s stomach. Another research group from Australia, this time based in Adelaide, has looked at the effectiveness of aloe vera in treating squamous ulcers and found that, although 56% of horses treated with aloe vera improved and 17% resolved after 28 days, this compared to 85% improvement and 75% resolution in horses given omeprazole. Therefore, Dr Bush and her colleagues from Adelaide concluded treatment with aloe vera was inferior to treatment with omeprazole.

Medications for glandular ulcers….