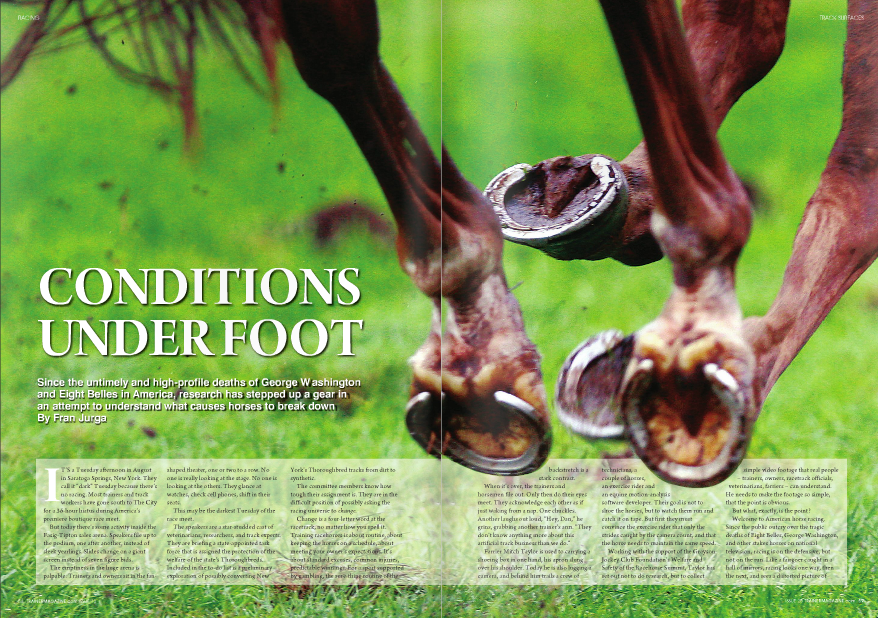

Conditions Under Foot - how different surfaces change the movement of a horse's foot

CLICK ON IMAGE TO READ ARTICLE

Fran Jurga (16 July 2009 - Issue Number: 13)

Hoof Matters - concentrating on the foot rather than the shoe

In 1889, for the fourth edition of his book “The Racehorse in Training with Hints on Racing and Racing Reforms”, the English jockey turned horse trainer William Day added a chapter on shoeing, his preface stating one topic, highly important to all owners of horses, might advantageously be added…the aim to deal with facts and to avoid speculation.

Caton Bredar (01 October 2007 - Issue Number: 5)

By Caton Bredar

In 1889, for the fourth edition of his book “The Racehorse in Training with Hints on Racing and Racing Reforms”, the English jockey turned horse trainer William Day added a chapter on shoeing, his preface stating “…one topic, highly important to all owners of horses, ‘Shoeing’…might advantageously be added…the aim to deal with facts and to avoid speculation.”

Day wraps up by adding that he hopes “it will be found…that the best method of shoeing and of the treatment of the foot has been not only discussed but actually verified… that the prevention which, in the diseases of the feet…is better than cure and has been placed nearer the reach of all.” If only.

Nearly 120 years after Day and his book, the “cure” for many horsemen plagued regularly by a variety of hoof ailments and issues seems as far out of reach as ever. With quarter cracks as common as quarter poles, horsemen particularly in North America continue to play out a modern day version of Cinderella, looking for the shoe that leads to happily ever after, or at the very least, to happy and sound on the racetrack. Among farriers, veterinarians and trainers there appears to be little agreement and much speculation when it comes to the shoeing of Thoroughbreds.

With no “best method” at hand, everyone can, in theory, agree with the familiar adage “no foot, no horse”. But there is great controversy surrounding how to go about improving horse hooves and preventing injury, or even why horses have so many hoof-related problems in the first place. When it comes down to the sole of the matter, at the end of the day, hoof care may well turn out to be the Achilles Heel of the Thoroughbred racing industry.

Most recently, the break-down and subsequent death of Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro brought the topic of equine injuries, and, more specifically, laminitis, to the forefront. Since Barbaro, American racetracks have spent millions installing synthetic surfaces, all espoused to be safer and more cushioned for horses. A record $1.1 million distributed this year by the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation to numerous equine research projects may also be a direct result of the late champion’s demise.

Last autumn, the foundation designated a Hoof Care and Shoeing Task Force, another possible throw-back to Barbaro and the subsequent focus on equine injuries. In the task force’s first official report this past April, prominent owner and breeder Bill Casner outlined one possible cause of injuries in “The Detrimental Effects of Toe Grabs: Thoroughbred Racehorses at Risk”. Endorsed by the Jockey Club, the Grayson Foundation and the Kentucky Horseshoeing School, the report placed the lion’s share of the blame for catastrophic injuries - and hoof-related issues - on the use of toe grabs in horse shoeing. Thoroughbred anatomy plays a role, according to the report: the fact that bone structure and hoof walls aren’t matured in the average racehorse; also the length of pastern or the type of hoof. The report also briefly mentions harder racetrack surfaces. But the overwhelming research revolved around the link between injuries and toe grabs.

Such thinking, according to at least one long-time farrier, may be what’s keeping the industry from finding Cinderella’s shoe. A self-proclaimed maverick, “as far out there as I can be,” North Carolina-based farrier David Richards believes rather than looking at the shoe, researchers should look at the foot.

Richards has been shoeing horses for the last 30 years. When asked what type or breed of horse he specializes in, the farrier replies “lame ones”. According to Richards, around 20 to 30 percent of the horses he works on annually are Thoroughbreds. Seventy to 90 percent of all the lameness problems he sees, according to Richards, are related to the hoof wall.

“We need to look more at hoof wall as a site of failure,” the farrier says, a principal which has become the backbone of “Equicast,” a product Richards has been developing and marketing for nearly 20 years. The cast, a tape-like, fiber-glass blend, covers the hoof, extending up to the hairline at the coronet band, with a shoe attached either on top of, or beneath, the cast. Its creator likens it to a walking cast in humans, with the event that Thoroughbreds are able to exercise while wearing it, although “there’s a big difference between hoof and human bone.”

“The key is managing lateral expansion,” Richards elaborates, “to prevent an overload of the hoof wall, causing hoof problems and pain. The hoof wall is the point of least resistance.” The cast “provides additional support and relieves pressure on the hoof wall,” he says, adding that his product minimizes heat and moisture, factors that also play a role in weakening hoof walls.

“When you adhere a shoe to a foot, you are frequently encapsulating bacterial materials,” the farrier offers. “Also, most apoxies are heat generating, and the hoof wall is already a great conductor of heat.”

Common solutions such as vitamin or feed supplements have a minimal effect at best, according to Richards. “The huge problem with any of that is that horses have very poor circulation to their feet.” Circulation issues cause problems all of their own in terms of growth and healing, but they also minimize the effect of anything ingested making a difference.

Richards believes a host of factors contribute to a general weakening of the structure of the hoof wall, “a complex and sometimes contradictory” situation that covers nearly everything wrong with feet, from quarter cracks to long toe-low heel to medial lateral imbalances and White Line Disease.

“There’s actually no problem in growing feet,” he offers. “The problem is in growing strong feet.

“We definitely see a more volatile foot today,” he concedes, citing feeding programs that cause quicker growth, synthetic surfaces that don’t stress the feet enough, and trends in commercial breeding as just a few of the possible contributing factors.

“One of the things we’re doing wrong, we’re not stressing the feet enough,” he says. “From the day that they’re born we’re coddling the foot.”

“I’ve never heard of a breeder breeding for feet,” Richards adds. “I can think of one really prominent sire that’s a classic example. I have four young horses by the same sire. Four babies right now that already have conformational issues. The sire has a great mind, tremendous ability. But his foals aren’t known for their feet.”

“You can’t knock it,” he continues. “But you have to accept the ramifications.” And figure out how to deal with them.

Richards looks to external factors as much as internal as a source of the problems. “Horses who run almost exclusively on turf don’t have half the problems as horses who run on sand,” he says. “They don’t have the shock factor. It’s unfortunate, but if something doesn’t stimulate feet to get harder, they get softer.”

Another factor Richards feels may contribute to weaker hoof walls is moisture. “Feet problems are something plaguing all horses evenly, from coast to coast,” he says. “Very little else is constant. Feed differs East to West, other things are different. One thing that’s constant, moisture. And variables of moisture.” Richards laments the fact that little has been done to research the effect of moisture on feet, or whether different parts of the hoof, or different types of hooves, absorb water differently. He’s currently doing his own research on white hooves to see how they react to moisture and believes it may lead to some answers for common problems.

“The industry is very grand-fathered in mentality,” he says. “It’s ‘my father did it that way, and his father did it that way.’ There’s a resistance to new products,” he continues. “The diagnostics now have surpassed the treatment. We’re always working with the result of the cause, rather than looking for the cause itself. We’re looking through the answer, for the answer.”

Looking down, rather than up, is another part of the problem according to Richards, “The goal is to balance the horse,” he offers. “It doesn’t matter what the sport, you’re ultimately judged on symmetry. There are times when I’m trying to figure out what’s wrong with a horse’s feet, instead of looking down at the foot, I look up to see which shoulder is higher. I’m one of a very few who are cognizant of the whole foot - not just the heel and the toe,” and just as important, how the whole foot fits with the rest of the horse.

Richards explains that the majority of the horses he looks at have one leg longer than the other, either from birth or wear and tear. He goes on to explain that the average 1,000 lb horse exerts 54 lb’s per square inch on the hoof wall with every stride. When that horse is shod, Richards says, the weight on the hoof wall is nearly doubled, to 95 lb per square inch. A typical racing plate exacerbates the problem even more. “We need to transition out of the conventional shoe,” he says. “We are overloading the coronary band.” “One of my criticisms of the industry,” he continues, “there is a total misunderstanding of what foot issues really are. Feet are no man’s land.” “Shoes haven’t changed much over the years,” he adds. “They’re prettier, but they’re going the wrong way. They mask the problems rather than reverse them. The horse may have a longer life on the track, but not a more productive or sounder one.” “It’s a horrible misnomer to say shoes are corrective,” Richards continues. “They’re not corrective. They are totally protective,” a line of thinking which supports the barefoot practitioners, who believe in eliminating shoes entirely at least part of the time. “I’m a huge proponent of it,” he says. “A horse should be totally comfortable doing his respective sport barefoot. The foot is much better at managing us than we are at managing the foot with conventional methods.” And while at least a few trainers are known to place blame on farriers, Richards holds veterinarians just as accountable, as they are generally the ones who actually diagnose the problems. “They know what’s wrong, but they often don’t know how to treat it,” he says. But in defense of the vets, “there’s a lot of misinformation and a lack of communication.” Perhaps the biggest culprit, from Richards perspective, is a close-mindedness and lack of commitment to the finding the cause of the problem and fixing it.

“There are a lot of things we need to do as an industry,” he says. “As an industry, we need to set a standard. There should be an orthopedic certification program, for example, that’s taught to both vets and to farriers. The vets will have to dummy down a little and the farriers will have to bone up.” “But a lot of this is just common sense. A horse with a foot bothering him is like having a tire with too little air in. You wouldn’t drive a car with less air in one tire, you’d fix the tire. You wouldn’t sit in a chair with one leg shorter than the others.” Richards believes we ask our horses to perform that way all the time. He believes at least some of the money for research should be re-allocated, or new money dedicated specifically to hoof issues. “What we need is to fix a flat.” “How much more does New Bolton really need?” he asks referring to the clinic that treated Barbaro through his final days and has since received hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations for research. “Problems evolve for a reason,” says Richards, who believes the reason almost always rests in the hoof wall. “If we find an effective way to address the problem, it will make a difference that could be revolutionary.” A difference hundreds of years in the making.

Hoof Cracks - a very common problem in racehorses

A keen-eyed racegoer spotted a horse running in the USA last summer with six quarter cracks spread between three of its feet. While this number would be highly unusual in the UK, the problem of the hoof crack is not, and is one, which plagues the trainer, vet and farrier. For the trainer, the words “The apple of your eye has popped a quarter crack, guv’nor,” are not welcome. Some great names have won Group One and other big races carrying hoof cracks, but the onset of a crack will result at minimum in serious problems in the horse’s preparation. Nevertheless, it is quite common for several horses to have cracks of one kind or another in a larger yard at the height of summer.

Tony Lindsell (European Trainer - issue 7 - Spring 2004)

A keen-eyed racegoer spotted a horse running in the USA last summer with six quarter cracks spread between three of its feet. While this number would be highly unusual in the UK, the problem of the hoof crack is not, and is one, which plagues the trainer, vet and farrier.

For the trainer, the words “The apple of your eye has popped a quarter crack, guv’nor,” are not welcome. Some great names have won Group One and other big races carrying hoof cracks, but the onset of a crack will result at minimum in serious problems in the horse’s preparation. Nevertheless, it is quite common for several horses to have cracks of one kind or another in a larger yard at the height of summer. “Some years you might have none, other years you might have two or three,” says Phil Brook, a leading Newmarket racing farrier who works with likes of David Loder, Chris Wall and Cheveley Park Stud.

The key to the treatment of hoof cracks lies in a determination of why they have occurred. This in turn relies on an understanding of the anatomy and dynamics of the hoof. TYPES OF HOOF CRACK Hoof cracks can occur at various locations on the hoof wall, and can be of varying degrees of severity. Cracks are normally defined by their location (toe, quarter or heel) and may also be defined by their type (e.g. sand, grass or horizontal) A grass crack originates at the ground surface and extends up the hoof wall; a sand crack originates at the coronary band, and runs downwards towards the base of the hoof. A horizontal crack runs more or less parallel with the coronary band. Cracks may be ‘superficial’ or ‘deep’. A deep crack can be defined as one, which has penetrated the sensitive laminae.

These are by far the more serious problem being the result of some trauma that has taken, or is taking place inside the hoof capsule. These can bleed during or after exercise and carry the additional risk of infection.

CAUSES OF CRACKS

Standard farriery textbooks will explain that the most likely cause of hoof cracks is either anterior-posterior (front to back) or medio-lateral (side to side) imbalance. Anterior-posterior imbalance may be caused by ‘long toe / low heel’ syndrome, which can result in breakover being forced too far forward through poor foot dressing. The pull of the deep digital flexor tendon conflicts with the point of breakover to cause a tearing of the laminae from the hoof wall and a consequent toe crack.

Likewise, medio-lateral imbalance may also be the result of the failure by the farrier to detect and correct, so far as is within his power, any imbalances. However, in most modern racing yards, good farriery can be taken as a given; and we have to look elsewhere for the causes of these cracks. Medio-lateral imbalance is more usually caused by conformation. Where it has not been possible to correct a limb imbalance when the animal was a foal, then the resultant incorrect loading will inevitably cause stress on other areas of the body, including the hoof. As the horse develops, this creates a potential for quarter-cracks.

A further cause may be injury – an overreach may cause injury to the coronary band, which results in poor hoof growth and a consequent crack in one area of the hoof. Alternatively, simply kicking the walls can open up a weak hoof or an old injury. “Thin-walled hooves with narrow heels can be particularly important causes of quarter-cracks,” says Phil Brook. “Likewise, flat and contracted feet can result in excessive tension at the coronary margin, also resulting in cracks.”

Another contributory factor is the breed itself. Bad feet are often inherited. If the hoof itself is of a weak structure, then it is even more susceptible to the development of cracks, whether through imbalances, conformation or injury. It is significant that cracks tend to appear in the spring and early summer as horses step up to faster work. All-weather surfaces have been cited as one of their root causes, the hard core exploiting any potential weaknesses in the hoof as both speed and concussion increase. Firm going may have the same effect.

TREATMENT OF CRACKS IN RACEHORSES

A hoof crack can never, of course, heal. The two sides of the hoof that have split will never grow together again. But, if the prime cause of the crack can be resolved, then there is usually no reason why good, solid hoof wall should not grow down from the coronary band to replace the area of the crack. The ultimate treatment for a serious hoof crack is of course rest. “Ideally,” says Phil Brook, “ you will want to get 1 – 1 ½ inches of growth from the coronary band before doing any work with the horse.” But for a horse in training, that is not often an option. Farriery techniques that might be used for the same problem on a horse that was not in training are not available to the racing farrier. For instance, lateral extension shoes to correct the weight-bearing through the hoof and limb, are not an optionwhilst the horse is in training, since these shoes will inevitably be lost in work and the problem perhaps exacerbated.

SUPERFICIAL CRACKS

Superficial cracks, which penetrate only the insensitive laminae, can normally be resolved by cleaning out and dressing by the farrier. It is important for the two sides of the crack to be separated so that the edges do not rub together as the hoof naturally expands and contracts with the horse’s action. If this is allowed to happen, then the crack will be perpetuated.

DEEP CRACKS

In the case of deep cracks, two different aspects of treatment are involved. On the one hand, action is required in order to address the original cause of the crack; and, on the other, the split hoof needs to be patched in order to immobilise the two sides, stabilise the hoof capsule and, when possible, allow the horse to continue to work. As Nick Curtis, farrier to Newmarket vets Greenwood Ellis, says, “You can put on any patch you want, but the underlying cause of the crack is what you need to find out. It is a 3-D thing – you have to take everything into consideration. The goal is to get the foot landing level and in line with the skeleton.” Without this double-handed attention, a horse can easily become lame. If, for instance, the two sides of a deep toe crack are pinching the sensitive laminae as the horse puts weight on the hoof, then lameness will follow. In addressing the cause of the hoof crack, the farrier has a number of options open to him. First and foremost, he will ensure that hoof balance is correct and will do whatever he can to correct any limb imbalances. Secondly he will probably use bar shoes to provide more support at the heel. On a racehorse, he is more likely to use ‘straight’ bar shoes than ‘egg’ bars, which can be pulled off in training and certainly in racing. Straight bar shoes are available either in steel or in aluminium versions. The aluminium version can be used for racing or simply as a lightweight therapeutic shoe. A secondary technique sometimes used is to relieve the bar shoe in the area directly beneath the crack in order to reduce the pressure being transmitted to that section of the hoof. This section of the hoof and shoe obviously has to be kept clean so that the effect of the relief is maintained. Thirdly, he may use a shock-absorbent sole packing material such as Vettec’s Equi-Pak. This is a liquid urethane dispensed onto the sole and frog which will ease concussion through the hoof. “Keep him off the all-weather surface for a while” could easily be additional advice from farrier to trainer. A nutritional supplement designed specifically for the hoof might also be recommended if the original problem has been a poor quality or thin-walled hoof.

PATCHING A CRACK

There are a number of ways that may be used to patch a crack, sometimes used on their own or in conjunction with each other. Shallow self-tapping screws may be inserted in the horn to either side of the crack. Wire or strong fibre filament is then wound between them to stabilise the crack. Similarly, a metal plate can be secured with screws on either side Wire can also be sutured directly into the good horn on either side of the crack without the use of screws. Another method, only open to the farrier over the last fifteen years, is the use of acrylic adhesives such as Equilox or Hoof Life and fibreglass cloth. Once the sensitive laminae exposed by the crack have healed sufficiently, a piece of fibreglass large enough to span the crack is impregnated with the adhesive, and is then applied over the surrounding area. Further adhesive is then applied on top To avoid infection, a straw or some form of removeable putty may be used underneath the adhesive, to create a cavity through which the area may be dressed and flushed out regularly. The acrylic or PMMA adhesives, whose main ingredient is Polymethyl Methacrylate, have proven the most effective in imitating hoof horn. Once cured, they can be rasped, and, when used for hoof repair, can be nailed into as if they were normal hoof wall. The Hoof Staple can also be used. This is a product resembling a double-ended fish-hook that spans the crack and is driven in on either side. In the USA, some senior veterinarians have started to use a product called Lacerum, manufactured by BeluMed X of Little Rock, Arkansas, in the treatment of hoof cracks. This is a platelet-rich plasma solution, obtained either from the horse being treated or a donor horse, that is used to promote healing, to accelerate the growth of healthy tissue and to fight off bacterial infection.

Thus, while cracks are, if anything, becoming more prevalent, new products and techniques are becoming available to the farrier as the result of developing technologies that permit him to address the issues in new ways and to find new solutions to the hoof crack problem. For further reading: ‘Farriery – Foal to Racehorse’ by Simon Curtis ‘No Foot, No Horse’ by Gail Williams and Martin Deacon ‘Hickman’s Farriery ‘(2nd Edition) by J. Hickman and Martin Humphrey ‘Principles of Horseshoeing II’ by D. Butler.