Training - 'horses with attitude'

By Ken Synder

“One refuses to run. One can’t run. One gets hurt. One’s a nice horse you have a little bit of fun with. And one’s a really nice horse that helps you forget the first four,” said trainer Kenny McPeek with a laugh, as he categorized new Thoroughbreds coming into his barn annually.

In some cases, that first one—the horse that refuses to run—really is forgotten, falling through the proverbial cracks of large stables with plenty of “really nice horses.”

“There’s very few of them we can’t figure out,” he said, “but sometimes we can’t.”

That’s where people like 71-year-old horseman Frank Barnett of Fieldstone Farm in Williston, Florida, (near Ocala) get involved. “I wish you could get to it by skirting the ‘issues,’ but you can’t,” he said. “That’s how they got to me.” Those issues are not loading into a trailer or starting gate, balking at workouts, throwing riders and—bottom line—acting as if they don’t want to become racehorses.

The principal issue underlying all the others, according to Barnett and Dr. Stephen Peters, co-author with Martin Black of the book Evidence-Based Horsemanship, is forgetting that horses are prey and not predatory animals. “Your horse is constantly asking, ‘Am I safe?’” said Peters.

The question supersedes everything else in a horse’s brain and, unfortunately, isn’t part of most Thoroughbred trainers’ knowledge of how psychologically a horse functions, according to Peters—a neuroscientist and horse-brain researcher. “One of our big problems is the only brain that we have to compare to the horse’s brain is our own, so we develop ideas like respect and disrespect.

“Horses don’t have a big frontal lobe. They can’t abstract things.

“Would you beat a child who couldn’t figure out a math problem? Of course, you wouldn’t. Punishment in a horse’s environment is a predatory threat,” Peters added.

The collaboration between Peters and Black, an Idaho-based horseman who teaches horsemanship, began when the former observed Black allowing a horse to rest after a training task, waiting and watching for the horse to drop its head, and then waiting for it to lick its lips. Then he would repeat the task or move to a new one. Peters, a neuroscientist and horse brain researcher, immediately knew Black was giving the horse “dwell-time.” In the simplest terms, that is the time between adrenaline subsiding in the horse’s brain from the stress of something like a training task before a “dopamine hit”—relief and, most critically, a feeling of safety. Stress to any degree causes a horse’s mouth to dry. Licking the lips after the stress signals a dopamine hit. The stress is over. I’m safe. Black instinctively knew he needed to wait on the horse.

“It’s almost an art in creating a neurochemical cocktail for your horse,” said Peters.

Black added, “Instead of drilling for 30 minutes, I would do an exercise taking maybe not even a minute.

“I will stress the horse--get the adrenaline going and then let it get the cocktail. They lick their lips and then they think about it, then they lick their lips again and the next time I ask them for it, it’s like we have been practicing it for a month.”

In their book, Peters and Black posit that dwell-time enables the horse to replay what it has just been through. Scans have shown brain areas used during something like a learning activity are still active while resting. Testing has also shown that subjects given dwell-time between a task learn faster than subjects not given space between learning exercises.

Black, who grew up working cattle on horseback and who also has a deep background with Thoroughbreds, recognized that “Peters had the science but didn’t have the experience. I had the experience but not the science.”

Peters explained, in part, the science: “What we do is introduce something to the horse, and we have to pause. We have to allow the horse a chance to assimilate the information. If not, the horse will get sympathetically aroused [experience increased heart rate, blood pressure, adrenaline activation and increased sweating] or tune you out. They disassociate. They put themselves somewhere else and they go through the motions. But that doesn’t mean they’ve learned what you have tried to teach them.

“Sometimes you’ll create a trauma, and now you have to take 100 good things to overcome that one bad thing because, as prey animals, they’re going to remember, ‘I was not safe.’”

In practical terms, a horse who was whipped to enter a trailer, for example, will always be difficult when asked to load. McPeek believes horses not only remember abuse but remember who it came from. “They do it on smell,” he said.

Peters’ and Martin’s book bridges the brain chemistry of horses and horse behavior and “language.”

Barnett is a Peters-Martin disciple whose training of horses spans experience watching horses and neural explanations for horse behavior provided by people like Peters. He provides another huge key in understanding why horses do what they do from his work: Horses will get a neurochemical release or dopamine hit from bad behavior as well as good. Punishing a horse, like in the example of whipping a horse for balking at trailer loading, will reinforce undesired behavior. Barnett, who works with dressage and eventing horses, said, “A horse stopping at a hurdle gets a dopamine release—stopping is a good thing in the horse’s mind. A good horse who hurdles gets the same kind of neurochemical release in its brain: dopamine endorphins.”

Barnett provides another example closer to Thoroughbred racing: A horse who fights or dumps an exercise rider in training is, in all likelihood, hurting. “If he’s hurting bad enough, he dumps somebody and then just stands there and stops. That’s going to tell you he’s not a bad horse. He’s just hurting.”

The problem is not the rider but what the rider is doing, according to Black. For a horse who stops going forward or tries to throw a rider, he would push the horse from behind with the rider still mounted but with the bridle removed. The typical response from an exercise rider will be, “’I need to hang on,’” said Black. “That’s the problem: you’re hanging on to him.

“Riders ride real tight, and horses get sore in their mouths. They might have abscesses. People don’t listen to the horse.”

Loading into a horse trailer is typically a difficult task for Thoroughbred trainers, particularly for young horses. In their brain, the horse is asking, “Am I safe?” Practically every horse, at least the first time, will balk. It’s a strange new environment. In the horse’s mind, according to Black, he or she might think they’re getting a big shove “off a cliff or into a black hole.” They don’t know if it is safe.

The remedy is calculated minor stress followed by quiet. “You bring the horse up to the trailer and give him a nudge. He backs out of there. ‘Nope. I’m not going.’ So he leaves. You go with him, and as soon as he turns around to leave the trailer, I get him bothered. I’ll walk him in circles. I’ll cause him some confusion and discomfort. His mind is racing, and he can’t figure out where comfort is.

“I’m not talking about twitching his ear or inflicting pain but making it so he can’t find relief or peace any place since leaving the trailer.

“Then I guide him back to the trailer. The closer he gets to it, the quieter I get. It’s like he’s escaping from all the chaos by going to the trailer. He’ll get on.”

The obvious question is how long might this take with a horse. “Might be one minute...might be 15 minutes,” said Black.

“Why does a horse do anything?” asked Peters, “because they’ve created a brain pattern or pathway. How are those pathways made? They’re dopamine reinforced. If I take my horse onto the trailer and he backs off and gets away and runs to a field, I’ve got to rewire its brain. If the horse gets punished for this, I’m creating a problem on top of a problem.

“Our job is to get dopamine hits set up.”

Black started (the term he uses rather than “broke”) Thoroughbreds for Calumet Farm for 10 years from 1995 to 2005 and believes much of bad Thoroughbred behavior is taught. “They get so many traumatic experiences on the racetrack.”

He is also doubtful training methods will ever change in the Thoroughbred industry. “They’re not going to change because they can get one in a hundred to win something. So why change?

“I heard this all the time: ‘You don’t understand; these are Thoroughbreds.’ Ok, so your horse won a million dollars. With your program, you have one horse that won a million dollars. You’ve got a hundred of them that dropped out of kindergarten. Every one of mine graduated, so whose program is better?”

Among the thousand-plus horses that Black estimates he started for Calumet, was Pleasantly Perfect, winner of $7.7 million and the Breeders’ Cup Classic in 2003.

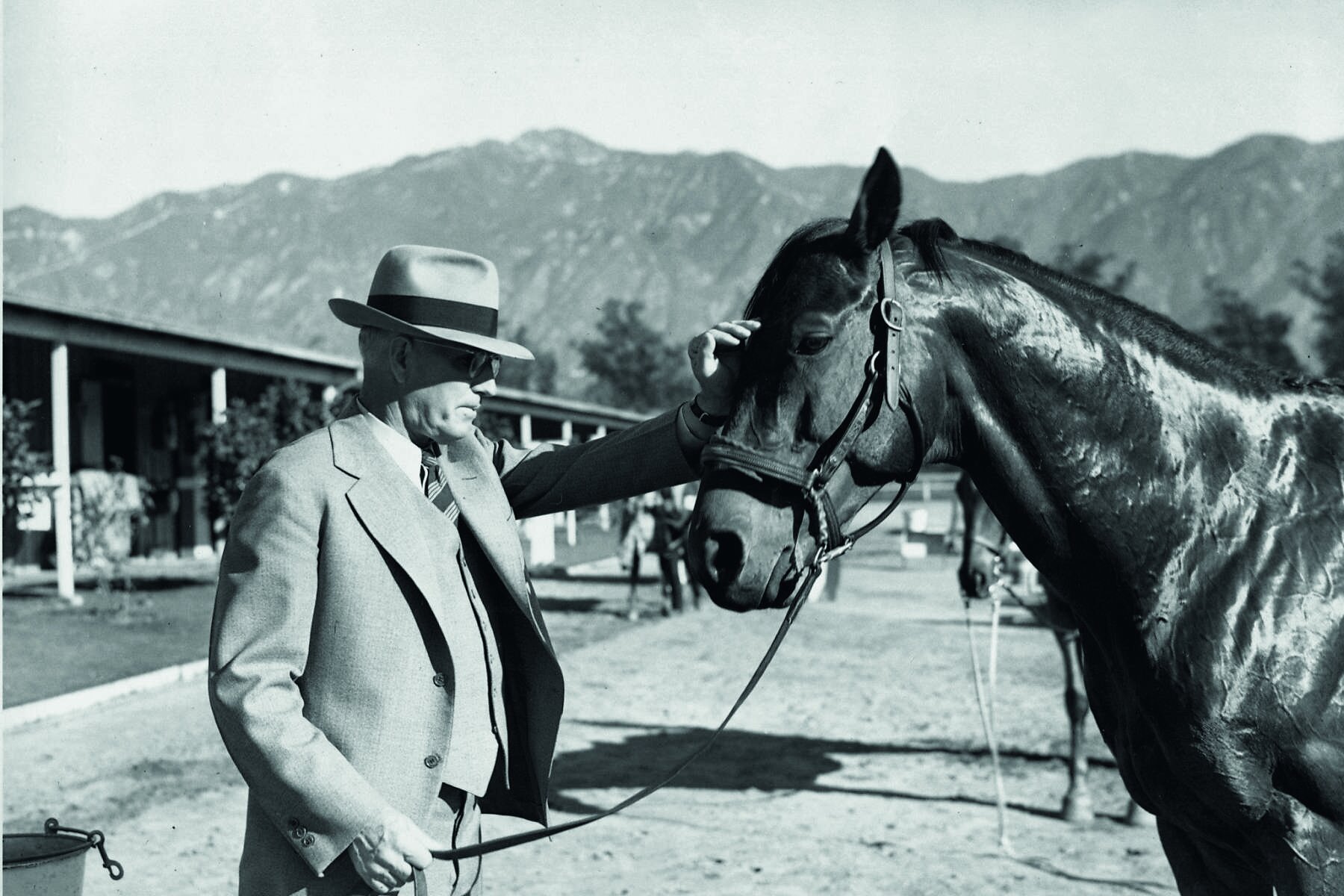

Akin to the example of a horse refusing to work out, there is the story of Seabiscuit, who ran 17 times before breaking his maiden. He didn’t want to run for legendary trainer “Sunny Jim” Fitzsimmons. He got moved to trainer Tom Smith’s barn. Tom was a Western cowboy with experience working with wild Mustangs. Seabiscuit’s behavior continued...for the first four workouts. Smith was known to sit in the stall for hours with a new horse he had gotten to somehow commune with and get an instinctual feel for that horse. He told an exercise rider with his hands full on the fifth day to drop the reins and let the horse do what he wanted to do. With that, the horse took off—apparently discovering the joy of running and then earned a carrot on the return to the barn, which became a standard reward. The rest is history.

Are methods like that espoused by Peters, Black and Barnett fool-proof? Peters simply said, “Horses are just like humans. Not every human being can play every sport.”

Sometimes, too, the “rehab trainer” like Barnett can only do so much. He recalled a promising horse sent to him by the old Waldemar Farm who wouldn’t load in the starting gate. Barnett got the horse past this fear. “The horse was doing scorching works, and everybody flew in to watch the first start at Gulfstream.

“I got a message on the answering machine after the race asking if, for the same money, I could teach the sonofabitch how to run. Ran last and never won a race.”

That would be McPeek’s category number two.

Acting up - the psychology of why horses can act up before a race

CLICK ON THE IMAGE ABOVE TO READ ONLINE

First published in European Trainer issue 56 - January '17 - March '17