An Introduction to the Functional Aspects of Conformation

By Judy Wardrope

Why is one horse a sprinter and another a stayer? Why is one sibling a star and another a disappointment? Why does one horse stay sound and another does not? Over the course of the next few issues, we will delve into the mechanics of the racehorse to discern the answer to these questions and others. We will be learning by example, and we will be using objective terminology as well as repeatable measures. This knowledge can be applied to the selection of racing prospects, to the consideration of distance or surface preferences and, of course, to mating choices.

Introducing a different way of looking at things requires some forethought. Questions need to be addressed in order to provide educational value for the audience. How does one organise the information, and how does one back up the information? In the case of equine functionality in racing, which horses will provide the best corroborative visuals?

After considerable thought, these three horses were selected: Tiznow (Horse #1) twice won the Breeders’ Cup Classic (1¼ miles) ; Lady Eli (Horse #2) won the Juvenile Fillies Turf and was twice second in the Filly and Mare Turf (13/8 miles); while our third example (Horse #3) did not earn enough to pay his way on the track. Let’s see if we can explain the commonalities and the differences so that we can apply that knowledge in the future.

Factors for Athleticism

If we consider the horse’s hindquarters to be the motor, then we should consider the connection between hindquarters and body to be the horse’s transmission. Like in a vehicle, if the motor is strong, but the transmission is weak, the horse will either have to protect the transmission or damage it.

According to Dr. Hilary M. Clayton (BVMS, PhD, MRCVS), the hind limb rotates around the hip joint in the walk and trot and around the lumbosacral joint in the canter and gallop. “The lumbosacral joint is the only part of the vertebral column between the base of the neck and the tail that allows a significant amount of flexion [rounding] and extension [hollowing] of the back. At all the other vertebral joints, the amount of motion is much smaller. Moving the point of rotation from the hip joint to the lumbosacral joint increases the effective length of the hind limbs and, therefore, increases stride length.” From a functional perspective, that explains why a canter or gallop is loftier in the forehand than the walk or the trot.

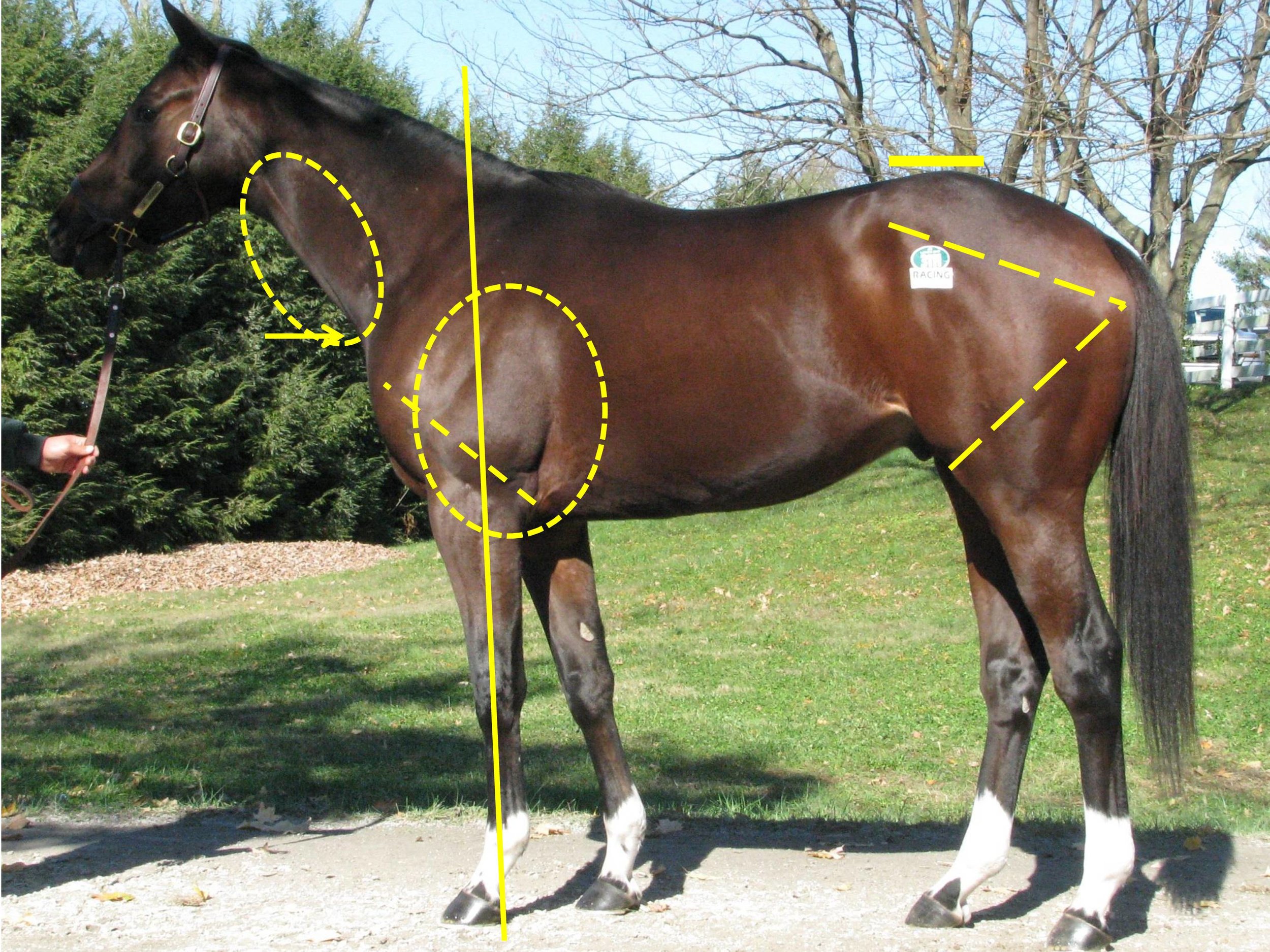

In order to establish an objective measure, I use the lumbosacral (LS) gap, which is located just in front of the high point of the croup. This is where the articulation of the spine changes just in front of the sacrum, and it is where the majority of the up and down motion along the spine occurs. The closer a line drawn from the top point of one hip to the top point of the other hip comes to bisecting this palpable gap, the stronger the horse’s transmission. In other words, the stronger the horse’s coupling.

We can see that the first two horses have an LS gap (just in front of the high point of the croup as indicated) that is essentially in line with a line drawn from the top of one hip to the top of the opposing hip. This gives them the ability to transfer their power both upward (lifting of the forehand) and forward (allowing for full extension of the forehand and the hindquarters). Horse #3 shows an LS gap considerably rearward of the top of his hip, making him less able to transfer his power and setting him up for a sore back.

You may also notice that all three of these sample horses display an ilium side (point of hip to point of buttock), which is the same length as the femur side (point of buttock to stifle protrusion)—meaning that they produce similar types of power from the rear spring as it coils and releases when in stride. We can examine the variances in these measures in more detail in future articles, when we start to delve into various ranges of motion as well as other factors for soundness or injury.

Factors for Distance Preferences…