What tweaks would you make to NH pattern races / calendar?

Article by Daragh Ó Conchúir

Getting consensus in racing is much like finding the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. So the changes to the Cheltenham Festival programme by The Jockey Club were lauded by many but criticised in plenty quarters too.

The press release announcing the six changes, headlined by the relegation of the Turners Chase from a Grade 1 to a Grade 2 novices’ handicap, said that they were made “with a focus on more competitive racing and a better experience and value for all”.

Everyone agrees with the focus. But Cheltenham is one meeting, THE meeting in terms of National Hunt racing. But if there is an issue of lack of competitiveness and entertainment, piecemeal measures don’t cut it.

Speaking at the Asian Racing Conference in Sapporo on August 28, BHA chair, Joe Saumarez Smith said it was time to stop thinking in the short term in a bid to reverse fortunes.

At the same conference, Hong Kong Jockey Club CEO Winfried Englebrecht-Bresges opined that fragmentation was a problem in British racing. It isn’t solely a British problem, given the number of interest groups, but it is made more acute by the lack of central control on a calendar and racing programme.

There is an African proverb that says, ‘If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.’ Unity is required to push past short-term goals in pursuit of the long-term future. Some would argue that given the niche element of national hunt racing, this unity of approach should extend across Ireland, Britain and even France as the three are interlinked in terms of competition and trade.

Some amendments have been made to the NH programmes in Britain and Ireland in the last year or so, in a bid to address the dilution of the value of graded form. Bigwigs from Horse Racing Ireland and the British Horseracing Association met towards the end of September for a think-tank to discuss numerous issues of shared interest. A discussion on working together in relation to the programme was among the topics but a broad chat was all that occurred.

Meanwhile, I spoke to a variety of stakeholders on where jump racing is going, what it needs and what it doesn’t, and got some interesting responses.

Emma Lavelle (Trainer: Britain)

A former president of the National Trainers’ Federation, best known for guiding the spectacular career of 2019 Stayers’ Hurdle winner Paisley Park, Emma Lavelle has been concerned about the dilution of the product offered by British jump racing for a few years now.

Lavelle offers a cogent and clear argument for change. What is remarkable, in her view, is that while there is too much racing, the programme swelled while still not catering for every tier of horse.

“Changes should be about trying to make racing more competitive at every level,” says the boss of Bonita Racing Stables.

“There's no doubt that uncompetitive racing doesn't make for interesting viewing, good betting medians. You will always have the odd uncompetitive race and sometimes, small fields are competitive and exciting, but uncompetitive racing is a turn-off, and it's a turn-off for the practitioners as well as the general public. So I think ultimately, we've got to do something to shake it up.”

Lavelle recounts that watching Frodon win the Ryanair Chase at Cheltenham, about 40 minutes before Paisley Park’s fairytale triumph in the Stayers, was as moving as it was exciting. Shishkin reeling in Energumene late on in a four-runner Clarence House Chase at Ascot three years later was on a similar level. That’s what needs to be encouraged.

Attempting to directly slow the growth and impact of NH’s major yards would be short-sighted she believes, punishing ambition and success.

“It’s just how the cookie crumbles,” as she describes the stunning resources now available to the likes of Willie Mulins. “But it’s why we need to find different ways of making sure that we can all be competitive.

“I do think that our race programme needs to become more aspirational from the bottom up. Finding a race for that 130, 140 rated horse is nigh on impossible. You’ve just got one race here and there. If you've got a horse that's rated 100 you can run it six times a week, and somehow that just doesn't seem right. We need to maybe force or encourage some lower-grade horses to compete in mid-tier races off lower weights as an incentive. Otherwise you’re racing to the bottom.”

The over-provision of lower-tier races applies at graded level in Britain too, apart from in the three-mile division she knows so well, when Paisley Park drew swords with the same opposition in the Long Distance, Long Walk, Cleeve and Stayers’ Hurdles to thrilling effect on an annual basis.

“The pattern of this country has been shaken up this year and a little bit last year to reflect that maybe it had just got a little bit big. Hopefully that will just help them make those races a bit more competitive. I do think that the fine-tuning and the slimming of it is an improvement, and I think that needs to happen in Ireland as well.

“The thing is, where do you send some of these horses if they miss some of the other races? And is it right that we're just turning everything into handicaps? You don’t want to take too many away, because otherwise, what's the point in trying to create a nice horse? So you’re getting the balance right and when you make changes, just seeing how they work.”

Giving alterations time to bed in and to determine their impact is critical, she feels, because there is no one silver bullet. Addressing some clear imbalances should be a starting point, however.

“We always talk about prize money. I If you're lucky enough to get a horse that's good enough to win mid-tier-and-up races. You deserve to be paid for that, and certainly to incentivise ownership, that’s important.

“We're always scared about really shaking up the programme. You look at the French system, a lot of their races are about how much prize money you've won up to a certain period or through a certain period. People are loath to try new things, and then you get a short run at it, because people don't really engage with it, so you don't get the runners, so the racecourses don't want those changes.”

The Wiltshire-based conditioner believes that a co-operative approach between the jurisdictions would benefit but doesn’t believe pursuing a uniform pattern is practical, at this juncture at least, with so much to be addressed on home territory first.

“It would make perfect sense if there was a centralised system of ratings, rather than how it is at the minute, where the Irish will get more weight when they come over here, etc. I think things like that would make sense.

“But the problem is, it's hard enough to get everybody in this country on the same page – and when I say get everyone on the same page, I mean where everybody is coming at it without self-interest, but for the good of the sport. So to think that you're then trying to join up with Ireland or other countries, I just don't know how that could happen. It would be wonderful if it did, but it would take some negotiating.”

If there is one factor, over any other, preventing the level of change Lavelle feels is required in Britain, it is the lack of central control of fixtures and programming.

“It's so frustrating. Sometimes you just feel, ’Why can't people take a step back and take their own interest out of it and look at the bigger picture?’ ”

Peter Molony (Breeder/Trader/Sales Agent/Racing Manager: Ireland)

Peter Molony is involved in the industry from the start of the process as a breeder, right through to the destination point, as racing manager for Kenny Alexander, owner of the history-making four-time Cheltenham Festival victor and dual Champion Hurdle-winning mare, Honeysuckle, and on the flat side, Qatar Racing’s Irish representative.

The Rathmore Stud manager is an ardent supporter of the ramped up NH mares’ programme in Britain and Ireland in the past decade, which has had such a monumentally positive impact on the demand for fillies at sales and their participation in jump racing.

Molony reckons the mares’ programme could be used as a test case for the creation of a broader uniform jump racing pattern in the jurisdictions. And if it worked, you would have a template to implement a programme on a universal level.

“What we have has been a huge improvement, and it's added massively to the overall racing experience, the market, in every way,” says Moloney of the mares’ programme. “But it's kind of grown up in a sort of higgledy, piggledy, sort of way, with a listed race added here, and a listed race added there, and not the greatest natural progression.

“At times you’d be wondering where the next race is if you wanted to stick solely to the fillies’ programme. So, I've suggested many times that the Irish and British authorities should sit down together and hammer out a proper pattern for them. And to be honest, it would make a lot of sense if they did it on a wider scale. But they could start with the fillies and mares, see how that works, and then go from there.”

As a breeder and trader who has produced the likes of former Gold Cup winner Bobs Worth and dual Cheltenham Grade 1 winner Sir Gerhard, and a NH agent with Goffs, the importance of the pattern is not lost on him. Nor is the erosion of the value of the exalted black type.

“If it was set up properly and got established, I think one pattern would add huge value to everything. And if you started with the fillies, it adds value to their form as well as to the overall enjoyment of the racing fan, of the overall racing product.

“You don’t want too many easy options, giving horses the chance to avoid one another all the time. The mares’ programme has been attacked in the past, and this continues to be attacked, that it's taking away from competitiveness. My argument is that it is actually adding competitiveness, because it's adding a whole new group of horses into the pool that wouldn't be racing at all.”

There were three distaff winners of the Cheltenham Champion Hurdle before 2016. Annie Power, Epatante and Honeysuckle have doubled that tally in the blink of an eye.

“Before the mares’ programme, the market didn’t exist. So you’d have none of those French mares. If you had a nicely-bred NH mare in Ireland, you just covered her. The racing mares are an exception. So the programme works but for it to be one programme would help it more.

“And then if that worked, bring it into the entire jump programme. In the flat game, people see progressions from your trials, into your Classics, and then into your later, all-age races with the clashes of the generations. People can see the progression, and that's great. It works well. It's easier to sell. I think if you had that in the national hunt game, it would be wonderful.

Willie Mullins (Trainer: Ireland)

There isn’t a sport in the world where sustained success isn’t at some point presented as a negative for the health of the sport. It must be tough to take even if criticism tends to be of a system rather than the winners’ magnificence.

He was crowned champion trainer in Ireland for a 17th straight year last season and became the first trainer since Vincent O’Brien 70 years previously to secure British honours. For context, Aidan O’Brien is on 26 consecutive native titles at the end of 2024 and a seventh British crown.

Mullins, an ex-chairman of the Irish Racehorse Trainers’ Association, believes that there are plenty of opportunities through the levels in Ireland, pointing to the growth of Gavin Cromwell’s operation as just one sample. He doesn’t see a need for a standardised programme between countries.

“I think people should be very careful when they start messing around with the programme,” says Mullins. “When you do little tweaks with the programme, you don't realise the consequences that will have somewhere else. So that's a great legacy that (former HRI chief executive) Brian Kavanagh and Jason Morris (former director of racing, now director of strategy) gave to Irish racing, and we should cherish it.

“A few of us go to France. The French never come over here. Prize money isn't good enough for them. Our seasons are just slightly different as well. But I think the story about Irish and English jump racing is probably Ireland versus England. And for that to take place, you have to have an English pattern and an Irish pattern. And we're very lucky that we have a race meeting called Cheltenham, where it's nearly, for the want of a better word, a World Championships in our game and all roads lead to there and then to Aintree and to Punchestown.

“I think it's huge, the way it works at the moment. So if you want to break that up, I'm not sure it would be beneficial.

“I also look at how racing has been put together by racing people, and I've seen, especially in Britain, over the last few years, people coming in from other sports, putting their imprint on racing, and they're not racing people. They don't realise how it works. They're in our sport for five years, and then they disappear off somewhere else. Meanwhile, they leave a fractured sport, putting in ideas that just don't take off or don't work.

“Racing is about breeding the best to the best, and hopefully get the best and taking on one another. And that's essentially it. That’s the core of racing.”

He considers the introduction of a team concept such as the Shergar Cup and racing League on the flat as ludicrous and argues that more focus should be on other factors in improving race-day experience for those in attendance than the action.

“When you have 35 minutes between races, it’s too long. I mean in the flat, it’s awful but even in national hunt. If you have a horse running in the first, and don’t have another till the last, it’s a long day. There are only so many cups of tea you can drink as there’s nothing else to do. It has been very boring for the public. They should look at that.

“And when it comes to Cheltenham, it is just too expensive.”

Jonathan Garratt (Kelso MD: Britain)

Jonathan Garratt has overseen the growth of Kelso as a desired destination for jumps racing with an imaginative, ambitious approach to programming and prize money.

Last year, Garratt was scathing in his criticism of the BHA’s premierisation policy which planned to “declutter” Saturday racing in Britain, warning it could destroy the sport’s grassroots. It is a policy, Garratt tells us, that ignores the uniqueness of jump racing.

“Each of the three codes (if I can separate all-weather flat racing from turf) have very different opportunities and different threats,” Garratt declares. “And yet the BHA lumps them all together in the fixture process and has encouraged them to compete for a two-tier funding system which they’ve christened ‘core’ and ‘premier’.

“While it’s fairly easy to see an elite strand of racing on the flat, which exists on a global stage, jump racing is a much more integrated environment, where top-class horses develop over time, frequently competing at a grassroots level on their way to the top. The best horses might compete in point-to-points, or bumpers, or both. Many will take in a handicap or two, some in relatively modest company.

“Even during the recent Willie Mullins domination, we’d be hopeful of spotting a future Cheltenham Festival winner, or a Grand National winner, at a Kelso fixture which has been allocated the ‘core’ label.

“My opinion is that jump racing has a more nuanced and interesting narrative than flat racing and so we don’t need these false labels. We should be encouraging racegoers to follow the action at all tracks, and enjoy the progression as horses move through the developmental races and become seasoned performers – at whatever level they eventually attain.”

The purpose of all-weather racing is to provide a betting product in time slots that are not available to jump racing, Garratt argues. The story of jump racing is far deeper and a key asset he maintains.

“Each code has its own strengths. One of jump racing’s strongest is its unique ability to create fantastic, romantic stories. While it’s flattering that so many people have credited Kelso with developing the jumps’ programme through the changes we made to the Morebattle Hurdle, the truth is that we simply tapped into strengths that already existed in jump racing – we increased the value of a high quality race which was close in proximity to Cheltenham, made it a handicap to give more runners a chance, and added a £100,000 bonus to tie us into the existing Festival narrative. We were very fortunate when The Shunter won it in the first year!”

Garratt doesn’t think a centralised pattern for the chief NH countries would work but never one to knock a suggestion without offering another, he makes a different, radical proposal.

“One idea which I’d throw out there, instead, is a unified trainers’ championship. At the moment, the top British trainers will favour races in Britain over valuable opportunities elsewhere because they want to win their Championship. I assume it’s the same in Ireland and France. I might be wrong, but Willie’s bid for the British Championship appeared to be an afterthought, it came into the reckoning after he’d already enjoyed a great Cheltenham.

“If a European Trainers’ Championship had a really good prize and was supported by the media, trainers might consider running in races throughout all of the countries which were part of it. I’m not saying it would work – but if greater international cooperation was considered beneficial to the sport, this might be one way to move it forward.”

Louisa Carberry (Trainer: France)

Louisa Carberry is a native of England from an eventing background who is based in France ten years, where she met and married Philip Carberry, the Champion Hurdle winning jockey from the famed clan that became the first Irish jockey to win the Grand Steeple-Chase de Paris – the French Gold Cup - in 2006.

She became the first foreign woman to train the winner of the Grande Steepe in 2020. Docteur De Ballon backed up 12 months later and with Louisa saddling Gran Diose to a third victory in five seasons last May, she is now in exalted territory.

The programme and prize money make France the most desired place to train for her.

“We have a lot fewer handicap handicaps over here in jumping,” Carberry explains. “What we do have is very valuable handicaps. There was a 100 grand handicap hurdle yesterday and that happens a couple of times a week, and they’re usually for horses rated from 0-130 and they’re highly competitive races.

“It’s a quite nice way of doing it. It might start off with a race for horses that haven't run three times or been placed twice. And then you might step up to races for horses that haven't picked up €20,000 this year. And then you get a kilo for every five grand you won. So you can sort of just step up and up and up. And then when you hit a bar, you change discipline. You go chasing.

“What I like is it's a very clear pyramid system here. For example, for chasers, five-year-olds and over, there’s one Grade 1 in the spring and one in the autumn. And so I think that's nice so the Grade 1 winner is essentially, hopefully, the best horse.”

With fewer jumps horses in training in France, there isn’t a need for the quantity of racing that exists in Ireland and Britain, but ensuring the best are taking each other on and that Grade 1s are not pieces of work should always be the target.

“Otherwise, it loses its importance, doesn’t it? We should have that stepping stone system, into a listed race if they’re capable and so on. You should be taking in a handicap on the way up unless, of course, the horse is clearly so super-talented that you don’t need to.”

She has little time for complaints about the dominance of Mullins et al.

“Everyone started somewhere. It should be more, ‘How can I compete with them more or, do as well as them?,’ rather than complaining. It’s easy to say that, of course, when I’m not in there. But you find what works. There are trainers that their business is based on selling one or two horses a year and if the horse goes on and runs well, they’re thrilled. Whereas I’d rather win a Gold Cup! But each to their own. I’d also be thrilled if the horse sold well and it went on to run well.”

Does being so prosperous within a French system remove the ambition of aiming for a Cheltenham Gold Cup, for example? Or would a uniform pattern, or at least something similar, bring travelling to one of the other two countries into focus for French trainers?

“Definitely, and we have gone to England and Ireland a couple of times. Happy to do more and are likely to do more. It's got to be worthwhile, that you think there's nothing more valuable over here. So it probably comes down to prize money, but then at the same time, God, I’d love to win a really good race, even if it was worth less than something over here. But over here, we know where we are, we've got our mark, their horse is going to do well, and it's worth a lot of money.

“I wouldn’t be against running in a nice handicap at Cheltenham either, by the way. It doesn't have to be a Grade 1. But you don’t know the horses you’re taking on, you don’t know the track, the racing style and the money isn’t great. So do I stick to what I know?”

Carberry believes more French-based trainers are looking beyond their borders, however. Current King George VI Chase favourite, Il Est Français (Noel George and Amanda Zetterholm) and Gold Tweet (Gabriel Leenders) made a splash in Britain in 2023.

“I think it's important for us to show that we're keen and willing and able and capable of running them, but probably things like the season and the programme, a few little tweaks there might help. But that’s not something that’s going to happen overnight.”

Conclusion

This subheading may mislead. We have no definitive answers here. There is plenty of logic though and a few intriguing proposals – take a bow, Jonathan Garratt with the idea of a European Trainers’ Championship!

Emma Lavelle’s championing of bands of racing for the mid-tier horse, and suggestions around adopting the French method of framing races around prize money, so well-articulated by Louisa Carberry, certainly appears to have a sound basis.

A single rating mechanism seems straightforward. Less so, perhaps, a NH equivalent of the European Pattern Committee that regulates the programme for flat racing, to avoid clashes in different jurisdictions, set conditions and ensure standard control i.e. that low-performing races have their status reduced and those constantly performing have them increased if they are not already Grade 1s.

One British course clerk, speaking off the record, had no doubt about the need for an overhaul of the pattern in some way. Of the circa 140 graded races in the jurisdiction, using three-year parameters, 54 of them are not performing.

The pattern is supposed to be how we accurately measure achievement and status, with a variety of ways of eventually reaching whatever your ceiling. But if it is diluted and Grade 1s are thrown about like confetti, the entire product and system is devalued.

Vin Cox, Yulong representative in Australia has discussed it in terms of a similar debate Down Under, about how the black type is the internationally recognised language but that its integrity is compromised by just adding another one “willy-nilly” i.e. without following a set list of criteria.

Any thriving entity needs cohesion. We shall wait and see.

GVQ-EQ business of racing update

Article by David Sykes

How is technology being used to ensure that the social licence to operate horse racing is maintained?

Social licence is a poignant topic previously covered within the magazine where we have looked at its meaning and why it is so important.

In this issue, David Sykes, the founding Partner of specialist management consultancy GVS EQ, takes a look at the power of technology on social licence and practical steps trainers can take with the help of these technologies.

Social licence is not something that is going to go away and so as an industry, using the modern tools available could prove to be a ground-breaking shift in measuring equine wellbeing and welfare.

So, what are we doing differently to maintain our Social Licence to Operate (SLO) in horseracing?

SLO is based on trust, transparency and an engagement with stakeholders (and non-stakeholders) and is essential for maintaining a positive relationship with the community involved in the horseracing industry and those who are onlookers from afar.

There is not a racing industry in the world that is able to act with full autonomy, including from its jurisdiction’s Government, and nor should there be. Part of the challenge, highlighted at the recent Asian Racing Conference, is that, rightly or wrongly, political decision-makers are legislators increasingly acting in relation to community sentiment, rather than evidence. This makes matters around the sport’s social licence all the more important.

This article leaves aside the direction of travel with regard to betting regulation, and focuses on matters more directly in the sport’s control, and its responsibility to its key participants.

The social licence to operate in horse racing is affected by animal welfare concerns, the public perceptions of the sport, how horses are treated, transparency and accountability of the horseracing industry.

And so how are we going about addressing concerns, perceptions, transparency and accountability?

Well, lots of different things but increasingly we are using technology to help us. Technology, increasingly including Artificial Intelligence (AI), is being used to gather the facts that help tell our story: how well our horses are treated and looked after, to address the concerns that would endanger our SLO.

Technology gives us the real time numbers, the data that supports better research and tells the story to help maintain racing’s social licence and monitor our horses’ wellbeing.

How do you measure happy?

There are lots of steps to assessing horse wellbeing. Historically this has often been subjective. Examples are “he looks happy” and “he’s moving well.” But we know we need to assess those traits in a measurable and repeatable way. Having repeatable objective assessments of wellbeing allows researchers to develop benchmarks against which we can measure how well our horses are doing.

Your horse cannot tell you when they have a fever and sore throat which then turns into a cough and nasal discharge 24 hours later. They cannot tell you about the sensitive tendon the day before the lameness appears and they cannot tell us when they are lonely or bored.

But various technological advances can forewarn us.

Much technology (like the smartphone apps) is widely available to horse enthusiasts and will give you a “leg up” to monitoring the health and wellbeing of your horse.

Additionally, these benchmarks provide feedback that allows for early intervention, prevention of poor outcomes, education and even regulation where wellbeing is assessed as less than optimal, and of course celebration when it is all going well and the result being a better life for your horse.

How can we systematically recognise and measure these behaviours that equate to wellbeing?

This is where these new technologies come into the picture.

Technology helps us by recording various physiological parameters and tracking metabolic status, then looking at this massive amount of data, rapidly analysing the complex information and quickly providing feedback to us.

Here are some examples of current technologies that can help provide objective measures that, as proxy measures, assess welfare and therefore perhaps serve as early indicators of welfare change.

If we can reliably tell a story using these facts – “my horse is performing well because his well-being is high – you can see it here” – then our social licence to operate is better protected.

Here are some advances

Continuous remote body temperature monitoring & temperature variation warning systems

Early and rapid recognition of temperature variations in horses in training is an excellent wellbeing management tool.

Measuring a horse’s temperature once or twice a day is common in many well organised equestrian facilities. It allows for the early detection of a potential disease or health problems. It is an indicator of wellbeing (or disease). Quarantine stables internationally record temperatures twice daily to monitor for infectious diseases.

Recent research suggests that horses who are strenuously exercised whilst having an elevated temperature or virus infection may develop heart rhythm abnormalities later in their careers.

Temperature Monitoring systems not only allow for individual horses to be automatically identified, and temperatures recorded and measured accurately after only 15 seconds but for any variation of more than 0.2 degrees from the running average trigger an alarm. This allows the trainer and staff to make an immediate decision on training, or exercise and put in place protocols within the stable process to assess if this is a minor change or if there is a medical reason for the temperature difference. By having the whole stable recording temperatures many infectious diseases such as respiratory viruses can be monitored and preventative quarantine measures put in place immediately.

There are also temperature recording systems that are associated with implanted Bio Thermal microchips. These chips continuously record body temperatures which are transmitted and evaluated automatically.

Automatic Appetite Monitoring Systems

Technology is now available that automatically records the amount of food not ingested by a horse for each feed. Notification alerts for food left are configurable by the trainer or owner. This feed left data is cross referenced with the temperature data to help figure out and understand any cause for periods of inappetence.

Behaviour and sleep monitoring and pattern analysis systems

Current research is only now beginning to allow us to understand and recognise the needs of our horses when stabled for lengthy periods. Technology has allowed data to be amassed and analysed on sleep patterns and REM sleep. Horses lie down for an average of only 4 hours every day. When they are lying down, they experience REM sleep for about half of that time. REM sleep is as important in the wellbeing of horses as it is for humans. The research from this analysis has shown that stable size and design has a significant impact on the willingness and safety that a horse feels in lying down. Stables need to be large enough for horses to lie down to get their REM sleep.

As they are flight animals, they are more secure and relaxed when they can see surrounding areas when they lie down. Soft deep bedding is important but also the ability to see their neighbours and surroundings is a safety point. Stables built with high solid walls do not meet this social wellbeing requirement, however new stable designs with bars, grills and open areas between adjacent stalls allow for visualisation, direct contact, opportunities to socialise, better ventilation and less stressed healthier horses.

Gait analysis systems

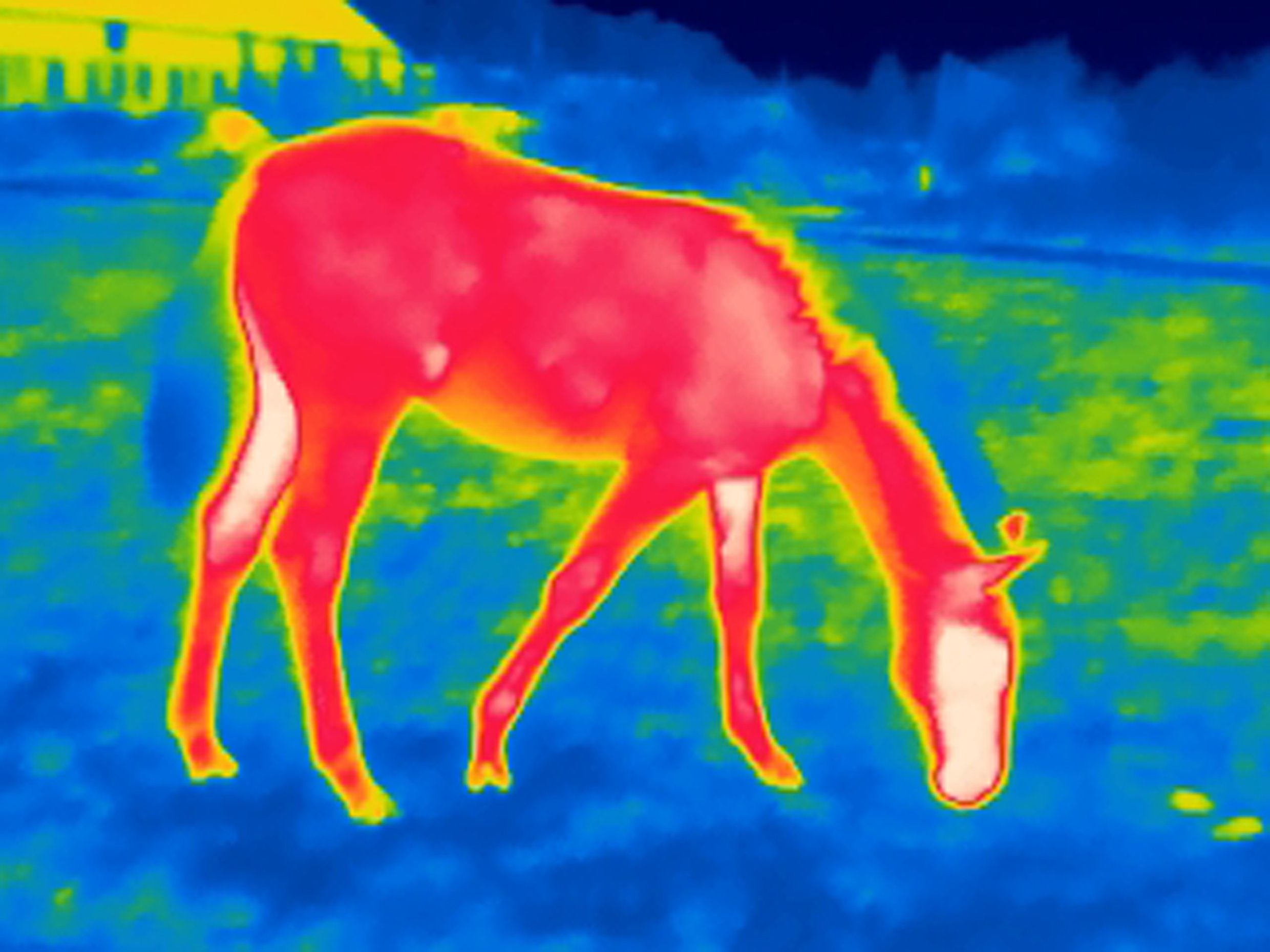

Over the last two years there has been considerable investment into gait analysing software programs to aid veterinarians, trainers and owners. This technology allows the monitoring of gaits of horses consistently and repeatedly. There are several examples of this technology ranging from handheld smart phone recordings to sensors attached to saddle cloths that can record and transmit information instantaneously during exercise.

Gait asymmetry analysis

A gait asymmetry analysis program using AI and a smartphone allows veterinarians and trainers to record and have analysed a repeatable trot up video of their horse. It is non-invasive, builds a history bank of gait symmetry and movement and allows for the recognition of changes in the symmetry of a horse’s gait. It describes exactly “how this horse goes” today, and yesterday and the day before. It analyses phases of steps on each leg analysing push off and landing.

Gait changes can be a proxy measure for pain or discomfort and recorded changes over time can aid owners, trainers and veterinarians to build a picture to inform diagnoses and response to treatments. Recognition of a sudden and significant gait change can allow time for changes in planned training loads and patterns to avoid potentially serious injuries occurring.

Racing stride analysis

This technology allows sensors to analyse the gait of a horse under race conditions to help identify musculoskeletal injuries and /or gait changes that may lead to a significant injury. Reports supplied to trainers and can identify a horse at an increased risk of a significant musculoskeletal injury.

A 100 gram GPS and accelerometer in a saddle cloth is the sensor used and attached before racing or fast work. Data is collected when the horse is galloping at racing speeds. Sensors collect data at 7200 times per second. The data shows that each horse has a unique way of moving at high speed much like a “fingerprint” and it is a change in this fingerprint that is used in a predictive model for injury or unsoundness diagnosis. It is a proactive management program to prevent training and racing catastrophic injuries through early detection.

Race condition speeds, heart rate and ECG and motion analysis

Other compact sensors are capable of live data transmission. Fitting inconspicuously into the riding tack and tracking GPS location, training speeds, Heart Rate, ECG tracing and locomotion analysis during training. They can assess cardiac variability with workloads such as maximum heart rate and rhythm during exercise and recovering heart rates post exercise. They also can be used for the detection of early signs of lameness. Training sessions can be shared worldwide through live tracking.

Gait symmetry apps provide an opportunity to follow a horse’s gait. Gait change is often the earliest indication of current disease or injury (pain and lameness) and combined with veterinary supporting diagnostic techniques can be useful in assisting the prediction or even prevention of future harm.

Advanced Imaging technologies

Computerised Tomography (CT) Imaging

New imaging technologies and equipment have led to the development of CT scanning techniques that are more suitable for horses. Previously horses had to be anaesthetised to have this imaging. The latest development of standing CT scanning systems has revolutionised the speed and safety of acquiring images of horse’s limbs whilst they are standing and sedated.

The complete process takes around 20 minutes from start to finish with the actual scanning activity taking less than 30 seconds. The upside is that this technology allows for superior images and more sensitive details of skeletal structural changes than was previously available.

The images from CT show more lesions than radiographs because of the increased image clarity. The research from this new technology indicates that the skeletal changes seen occur as a response to training workloads. Current research suggests that the horse’s skeletal system is remodelling under training loads to become more resilient, however during this process there are periods of time whilst remodelling occurs, that the horse is at a higher risk of a small lesion developing into a major injury. The early identification and recognition of these small lesions allows for a change in the training workload or a period of rest to allow the bone to catch up, remodel and protect itself from becoming a more serious injury.

This is an example of how technology from human medicine has been refined for horses and allows for the earlier detection of what might become a serious injury and allows changes in training patterns and workloads that might help prevent it.

PET imaging or Positron Emission Technology

This is like CT scanning; however, it gives a dynamic imaging of injury in distal limbs rather than a static view. This nuclear medicine technology involves the injection of a small dose of radioisotope which is taken up by the bone in areas where there is increased active remodelling occurring. These remodelling areas are an indication of the bone attempting to cope with the stress of training and protect itself from further injury. Because of the nuclear medicine this imaging allows for an interpretation of the severity of a lesion depending on the uptake of the isotope.

“Hot lesions” take up more radioactive isotopes and therefore the scan reflects the relative acuteness of the lesion being viewed. Potentially repeat PET scanning allows for accurate interpretation of when lesions are healing and a horse can return to full activity safely. Like CT, PET, allows for the early identification of changes that the horses’ bones are undergoing, assess the severity of them and modify the training regimens and workloads as a preventative measure, potentially avoiding severe injury.

These are just a few examples of the rapidly developing potent tools for health monitoring that may provide a ground-breaking shift in your horses’ healthcare. Hand in hand with good horseman skills and observations, technology and AI are allowing the collection and interpretation of information that can be used to understand and measure equine wellbeing and welfare. This information when collated becomes a benchmark for the industry and allows for transparency, accountability, overcomes poor perception and allows the industry to maintain its Social Licence.

What is racing's "Social Licence" and what does this mean?

Paull Khan expands upon a presentation he gave at the

European Parliament to the MEP’s Horse Group on November 30th

As World Horse Welfare recently pointed out in its excellent review of the subject—while social licence or the ongoing acceptance or approval of society may be ‘intangible, implicit and somewhat fluid’—an industry or activity loses this precious conferment at its peril. Examples, all too close to home, can be seen in greyhound racing in Australia and America or jumps racing in Australia.

What is clear is that our industry is acutely aware of the issue – as are our sister disciplines. The forthcoming Asian Racing Conference in Melbourne in February will feature a session examining what is being done to ‘ensure that (our) a sport is meeting society’s rapidly evolving expectations around welfare and integrity’. And back in November, the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) held a General Assembly whose ‘overriding theme’ was ‘that of social licence, and the importance for all stakeholders to understand the pressing needs for our sport to adapt and monitor the opinions of those around us’.

Considered at that meeting were results of a survey, which indicated that two-thirds of the public do not believe horses enjoy being used in sport and have concerns about their use. Those concerns mainly revolve around the welfare and safety of the horses. Intriguingly, a parallel survey of those with an active involvement in equestrian sport revealed that as many as half of this group even did not believe horses enjoyed their sport; and an even higher proportion than the general public—three-quarters—had concerns about their use.

While it is likely true, to an extent at least, that the public tends not to distinguish between equestrian sports, the specific concerns about horse racing are certainly different from those about Olympic equestrian disciplines, which centre on such matters as bits, bridles, spurs and nosebands.

Upon what, then, does our social licence in European horse racing critically depend? What are the major issues about which the public has opinions or worries, and on which the continuance of our social licence may hang? It should be said at the outset that what follows is not based upon scientific evidence (and the research should certainly be undertaken) but merely reflects the belief of the author. But it is suggested with some confidence that the following (in no particular order) are the three issues uppermost in public consciousness. They are:

Use of the whip

Racecourse injuries/fatalities

Aftercare – the fate of retired racehorses

There are, of course, other matters – the misuse of drugs and medications, gambling harms, etc., but the three topics above seem to account for a large proportion of the public’s anxieties about racing. There are likely to be subtle differences in the views of the public between one European country and another. Certainly, it is true that the volume of public disquiet varies very considerably between nations. In Scandinavia and Great Britain, for example, horse welfare and animal welfare more generally are very much front of mind and near the centre of public discourse. It is far less evident in several other countries.

But it is illuminating to look at what racing has been doing in recent years in the three areas listed above, and what the future looks like. A survey was conducted among member countries of the European and Mediterranean Horseracing Federation (EMHF); and it is clear that, while there is much still to be done, there has been significant and sustained progress and good reason to believe that this is likely to continue – and in fact accelerate – over the next few years.

Use of the whip

Let us consider whip use first. At the most recent World Horse Welfare Annual Conference in London in November, straplined ‘When Does Use Become Abuse’, one speaker was called upon to give strategic advice as to how to counter negative perceptions of equestrianism.

What he decided to major on was striking. With the whole breadth of the equine sector from which to draw, he chose to hone in on horseracing and—more specifically yet—on the issue of whip use. It was a salutary further example of how, while the whip may be a tiresome distraction to many, it is front and centre in the minds of many of the public.

Is there any more emotive or divisive issue within racing than the whip? Admittedly, most racing professionals hold that it really is very difficult to hurt a horse with the mandated padded crops, even if one wanted to. And, with veterinary supervision at all tracks, it is impossible to get away with, even if one did. In brief, they don’t consider this a welfare issue, but rather one of public perception.

But it is then that the divisions set in. Some conclude that all that is necessary to do has been done, and that any further restriction on the whip’s use would constitute pandering to an ignorant public. Others argue that, even if it is just a matter of public perception and the horses are not being hurt or abused, the sight of an animal being struck by a human is now anathema to increasingly broad swathes of society—in a similar way to the sight of a child being struck by an adult: a commonplace 50 years ago, but rare today. Therefore, the sport must act to be ahead of the curve of public sentiment in order to preserve its social licence.

How is this argument playing out? Let us look at a key element of the Rules of Racing in 18 European racing nations—the maximum number of strikes allowed in a race is a blunt measure, indeed, and one that takes no account of other variables such as the penalty regime for transgressions, but one that, nonetheless, paints a telling picture.

The first map shows how things stood 20 years ago. The majority of the countries are shown in black, denoting that there was no specified limit to the number of strikes. Just one appears in white – Norway banned the use of the whip as long ago as 1986.

The second paints the picture as it was 10 years ago. Eleven of the 18 countries had, in the intervening decade, changed their rules and applied a lower maximum number of strikes, and are shown in a lighter colour as a result.

Today’s situation is shown in the third map. All but one of the countries (excluding Norway) have tightened up their whip use rules still further over the past decade. None now allows unlimited use, and countries now banning the use of the whip for encouragement, number four.

It can be concluded that all countries across Europe are moving towards more restricted use of the whip. At different speeds and from different starting points, the direction of travel is common.

What will the situation be in another 10 years? Many administrators within EMHF countries, when asked to speculate on this, gave the view that there would be no whip tolerance within ten years and that the Scandinavian approach will have been adopted.

On the other hand, Britain has recently concluded that the biggest public consultation on the subject and the new rules that are being introduced do not include a reduction in the number of strikes, but rather a series of other measures, including the possible disqualification of the horse and importantly, the requirement only to use the whip in the less visually offensive backhand position.

Whether or not we will see a total ban within the next decade, it must be long odds-on that restrictions on whip use, across the continent, will be stricter again than they are today.

Aftercare

Twenty years ago, little thought was given to the subject of aftercare. There were some honourable exceptions: in Greece, the Jockey Club required its owners to declare if they could no longer provide for their horse, in which case it was placed in the care of an Animal Welfare organisation. Portugal had a similar reference in its Code. Most tellingly, in Britain a trail-blazing charity, Retraining of Racehorses (RoR), had been launched, following a review by the former British Horseracing Board.

Ten years ago, RoR had nearly 10,000 horses registered, had developed a national programme of competitions and events in other equestrian disciplines, and was holding parades at race-meeting to showcase the abilities of former racehorses to enter new careers.

Di Arbuthnot, RoR’s chief executive, explains, “In the UK, a programme of activities for thoroughbreds had started to encourage more owner/riders to take on former racehorses. This was supported by regional volunteers arranging educational help with workshops, clinics and camps to help the retraining process. Other countries were looking at this to see if similar ideas would work in Europe and beyond.

“Racing’s regulators had begun to think that this was an area they should be looking to help; retraining operators and charities that specialised in thoroughbreds were becoming recognised and supported; and classes at equestrian events began in some countries. Owner/riders were looking to take on a thoroughbred in place of other breeds to compete or as a pleasure horse; the popularity of the thoroughbred was growing, not just by professional riders to use in equestrian disciplines, but also by amateurs to take on, care for and enjoy the many attributes of former racehorses.

“The aftercare of the thoroughbred was on the move.”

But not a great deal else was different in the European aftercare landscape.

Since then, however, there has been little short of an explosion of aftercare initiatives. In 2016, the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses (IFAR) was born, “to advocate for the lifetime care of retired racehorses, to increase awareness within the international racing community of this important responsibility.” In this endeavour, IFAR is not in any way facing resistance from Racing Authorities – far from it. It is pushing against an open door.

The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities has, as one of its twelve objectives, the promotion of aftercare standards. And the chair of its Welfare Committee, Jamie Stier, said some years ago that there is ‘now a better understanding and greater recognition that our shared responsibility for the welfare of racehorses extends beyond their career on the racetrack’.

This direction from the top has been picked up and is increasingly being put into active practice. Also in 2016, France launched its own official charity Au Dela des Pistes, (‘beyond the racetrack’), in 2020 Ireland followed suit with Treo Eile (‘another direction’). By 2019, in Britain, remarkably, many more thoroughbreds were taking part in dressage than running in steeplechases!

So now the three main thoroughbred racing nations in Europe all have active and established aftercare programmes; and many other smaller racing nations are moving in that direction. It is not just a matter of repurposing in other equestrian pursuits – many of those horses retiring from racing that are not suited to competitive second careers are simply re-homed in retirement and others find profitable work in areas such as Equine Assisted Therapy.

Arbuthnot (also chair of IFAR) adds: “For racing to continue as we know it, we must assure the general public, those that enjoy racing, that thoroughbreds are not discarded when their racing days are over and that they are looked after and have the chance of a second career. It is up to all of us around the world to show that we care what happens to these horses wherever their racing days end and show respect to the thoroughbred that has given us enjoyment during their racing career, whether successful or not on the racecourse. If we do this, we help ensure that horse racing continues in our lifetime and beyond.”

It is important to publicise and promote the aftercare agenda, and the EMHF gives IFAR a standing platform at its General Assembly meetings. EMHF members have translated the IFAR ‘Tool Kit’—for Racing Authorities keen to adopt best practice—into several different European languages.

Time Down Under and Justine Armstrong-Small: Time Down Under failed to beat a single horse in three starts but following his retirement from racing, he has reinvented himself, including winning the prestigious showing title of Tattersalls Elite Champion at Hickstead in June 2022. Images courtesy of Hannah Cole Photography.

British racing recently established an independently chaired Horse Welfare Board. In 2020, the Board published its strategy ‘A Life Well Lived’, whose recommendations included collective lifetime responsibility for the horse, incorporating traceability across the lifetimes of horses bred for racing.

Traceability will be key to future progress, and initiatives such as the electronic equine passport, which has been deployed among all thoroughbreds in Ireland and Britain, will play a vital part. Thoroughbred Stud Book birth records are impeccable, and we know the exact number of foals registered throughout this continent and beyond. The aim must be to establish the systems that enable us to ascertain, and then quantify the fate of each, at the least until their first port of call after retirement from racing.

Racecourse injuries

There can be nothing more distressing – for racing professionals and casual observers alike – than to see a horse break down. The importance of minimising racecourse injuries—and, worse still, fatalities—is something everyone agrees upon. What is changing, though, it would appear, is the potential for scientific advances to have a significant beneficial effect.

Of course, accidents can and do befall horses anywhere and they can never be eliminated entirely from sport. But doing what we can to mitigate risk is our ethical duty, and effectively publicising what we have done and continue to do may be a requirement for our continued social licence.

There is much that can be said. It is possible to point to a large number of measures that have been taken over recent years, with these amongst them:

Better watering and abandonment of jump racing if ground is hard

Cessation of jump racing on all-weather tracks

Cessation of jump racing on the snow

Safer design, construction and siting of obstacles

By-passing of obstacles in low sunlight

Colouring of obstacles in line with equine sight (orange to white)

Heightened scrutiny of inappropriate use of analgesics

Increased prevalence of pre-race veterinary examinations, with withdrawal of horses if necessary

The outlawing of pin-firing, chemical castration, blistering and blood-letting

Abandonment of racing in extreme hot weather

Many of the above relate to jump racing, and Britain has witnessed a reduction of 20% in jump fatality rates over the past 20 years. But there is more that must be done, and a lot of work is indeed being done in this space around the world.

One of the most exciting recent developments is the design and deployment of ground-breaking fracture support kits which were distributed early in 2022 to every racecourse in Britain.

Compression boots suitable for all forelimb fractures

By common consent, they represent a big step forward – they are foam-lined and made of a rigid glass reinforced plastic shell; they’re easily and securely applied, adjustable for varying sizes of hoof, etc. They reduce pain and anxiety, restrict movement which could do further damage, and allow the horse to be transported by horse ambulance to veterinary facilities.

X-rays can then be taken through these boots, allowing diagnosis and appropriate treatment. These kits have proved their worth already: they were used on 14 occasions between April and December last year, and it would appear that no fewer than four of these horses have not only recovered but are in fine shape to continue their careers. It is easy to envisage these or similar aids being ubiquitous across European racetracks in the near future.

Modular splints suitable for slab fractures of carpal bones

Perhaps of greatest interest and promise are those developments which are predictive in nature, and which seek to identify the propensity for future problems in horses.

Around the world, there are advances in diagnostic testing available to racecourse vets. PET scanners, bone scanners, MRI scanners and CT scanners are available at several tracks In America, genetic testing for sudden death is taking place, as is work to detect horses likely to develop arrhythmias of the heart.

Then there are systems that are minutely examining the stride patterns of horses while galloping to detect abnormalities or deviations from the norm. In America, a great deal of money and time is being spent developing a camera-based system and, in parallel, an Australian-US partnership is using the biometric signal analysis that is widely used in other sports.

The company – StrideSAFE – is a partnership between Australian company StrideMASTER and US company Equine Analysis. They make the point that, while pre-race examinations that involve a vet trotting a horse up and down and looking for signs of lameness, can play a useful role, many issues only become apparent at the gallop.

There are, in any case, limitations to what is discernible to the naked eye, which works at only 60 hertz. StrideMASTER’s three-ounce movement sensors, which fit into the saddlecloth, work at 2,400 hertz, measuring movements in three dimensions – forward and backward, up and down and side to side, and building up a picture of each horse’s ‘stride fingerprint’.

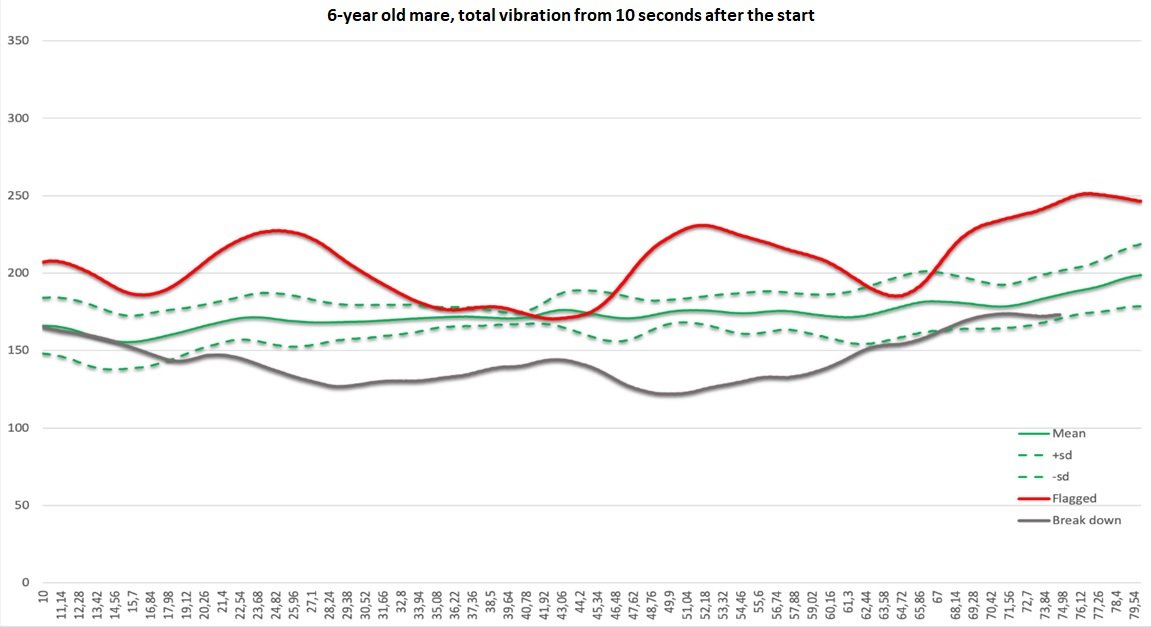

In a blind trial, involving thousands of horses, 27 of which had suffered an injury, this system had generated a warning ‘red-flag’ for no fewer than 25 of them. The green lines in the centre of this diagram are this horse’s normal stride fingerprint; the red line was the deviant pattern that would have flagged up the potential problem, and the grey line was where the horse then sadly injured itself.

The ‘stride fingerprint’ of a racehorse

While the false-positive rate is impressive for such screening tools, another enemy of all predictive technologies is the false positive, and ways need to be found to take action on the findings without imposing potentially unnecessary restrictions on horses’ participation. At present, the StrideMASTER system is typically throwing up three or four red flags for runners at an Australian meeting—more in America.

A study in the spring by the Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council, centering on Churchill Downs, will seek to hone in on true red flags and to develop a protocol for subsequent action. David Hawke, StrideMaster managing director, expands, “Protocols will likely vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, depending on the imaging modalities available. At Churchill Downs, they will have a PET scan, and we will be going straight from red-flag to PET scan.”

There will be other approaches available to regulators involving, for example, discussion with the trainer, a requirement for a clean vet’s certificate, or perhaps for a normal ‘fingerprint’, before racing next.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a need for continued investment and resource allocation by Racing Authorities. But the will would seem to be there. In Britain, €7M from betting will, over the next three years, fund an extensive array of no fewer than 26 horse welfare projects, covering such matters as education and support for re-homers, analysis of medication data and clinical records, fatalities occurring off the track, ground/going research and obstacle improvement and development. That is a serious statement of intent and an illustration of just how high in importance the welfare of racehorses has now become.

Of course, not all racing nations have the resources to conduct such research. It will be vital, therefore, that the lessons learnt are shared throughout the racing world. In Europe, this is where the EMHF will play a vital role. The federation has always had, as primary aims, education and the adoption of best practice across its membership.

The hope must be that, through all these measures and many others in combination, we can assuage the concerns of the public sufficiently to retain our social licence. But let our ambitions not rest there. We must also strive to shift the debate, to move onto the front foot and invite a focus on the many positive aspects of racing, as an example of the partnership between man and horse that brings rich benefit to both parties.

Elsewhere in this issue, there is a feature on racing in Turkey, and it was the founding father of that country, Kemal Ataturk, who famously said:

“Horseracing is a social need for modern societies.”

We should reinforce at every opportunity the fact that racing provides colour, excitement, entertainment, tax revenues, rural employment, a sense of historical and cultural identity and much more to the human participants. It is also the very purpose of a thoroughbred’s life and rewards it with ‘a life well lived.’

We have a lot more to do, but let’s hope we can turn the tide of public opinion such that people increasingly look at life as did Ataturk.

EMHF UPDATE - Dr. Paull Khan reports on the Asian Racing conference, Cape Town, stewarding from a remote 'bunker' and the 'Saudi Cup'.

By Dr. Paull Khan

ASIAN RACING CONFERENCE, CAPE TOWN

The Asian Racing Conference (ARC) is the most venerable institution in our sport. It may seem strange, but the Asian Racing Federation (ARF) is older than its parent body, the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities (IFHA). Its conferences, while only biennial compared with the IFHA’s annual get together in Paris after the ARC, go back further—60 years in fact. And, because of the liberal definition of ‘Asia’ employed by the ARF, the conference found itself this year in Cape Town, South Africa, just as it had done once before, in 1997.

What might one glean from conferences such as this about the state of racing globally?

Well, attendance at the Cape Town event could be taken as evidence of an industry in reasonable health. The gathering attracted around 500 delegates from some 30 countries, but despite the Coronavirus effect, a large contingent of intended delegates from Hong Kong and smaller numbers from mainland China were unable to travel. Ten years ago, when the conference was hosted in Sydney, 550 attended from 36 countries. So, attendance has held up well over the past decade.

But the content of the conference perhaps tells a different story. Back in 2010, the ‘big debate’ centred on the funding of racing, and the relationship between betting and racing in this regard. What struck me about the subject matter in 2020 is that it was less about maximising income, more about the long-term survival of the sport. By way of evidence of this, there were sessions on the battle against the scourge of the rapid expansion of illegal betting, the threats to horse racing’s social licence in the wake of growing global concern of animal welfare and the mere use of animals by humans, and the urgent need to engage governments to retain their support for our industry.

That is not to say that it was all doom and gloom. Far from it. The conference opened with a stirring discussion of the potential benefits of 5G technology and closed with a session explaining why there is now real optimism that, after years of isolation, South African thoroughbreds will soon be able to travel freely to race and breed.

The 5G (fifth generation) standard for mobile internet connectivity is 1,000 times faster than its predecessor, can support 100 times the number of devices and enables full-length films to be downloaded in just two seconds. While the technology is already here, coverage is limited to date but is predicted to expand with searing rapidity over coming months. The implications of this are manifold for all of us. Indeed, it was said that the opportunities it presents will be like ‘a fire hose coming at you’. Potential benefits that speakers identified for all aspects of horse racing came thick and fast. These benefits include:

Real-time horse tracking, enabling punters watching a race to identify ‘their’ horse.

The ability to provide more immersive customer experiences—you will be able to ‘be’ the jockey of your choice and experience the race virtually from his or her perspective.

Hologram technology is already creating ways for music fans to experience gigs from around the world—why not horse racing as well?

Through the internet, the physical world is being ‘datafied’—great advances will flow from this in the shape of; e.g., the monitoring, through sensors, of such things as horses’ heart rates.

Facial recognition at racecourses will (privacy laws permitting) enable the racecourse to know its crowd much better.

Using heat-mapping and apps on racegoers’ mobiles, congestion control will be aided, and individual racegoers encouraged to go to tailored outlets.

The problem, of course, is that 5G’s benefits will be available for all sports and competing leisure and betting activities. In order to retain market share, racing will need to match others’ use of these new technologies. Each race is fast—it’s over in a matter of minutes. And understandably, while racing has some traits that work in its favour in the mobile age, in other respects, it is not well placed. Racing is fragmented, with no overarching governing body and many internal stakeholders bickering over intellectual property rights. For Greg Nichols, Chair of Racing Australia, “There’s an urgency in contemporising our sport”.

On illegal betting, the message for Europe from Tom Chignell, a member of the Asian Racing Federation’s Anti-Illegal Betting Task Force, and formerly of the British Horseracing Authority, was stark: illegal exchanges are already betting widely on European races. Pictures of those races are being sourced and made available through their websites. The potential for race-fixing is obvious.

Policing the regulated betting market and the identification of race-fixing are difficult enough. It becomes significantly more so in the illegal market, since operators are under no obligation to divulge suspicious betting activity and are unlikely anyway to know who their customers actually are.

BHA Chair Annamarie Phelps speaks on the ARC Welfare Panel

It was acknowledged that illegal betting, which is growing faster than legal betting, is already so big—so international that sport alone cannot tackle it. What is needed is multi-agency cooperation, which must include national governments. Indeed, the new Chair of the British Horseracing Authority, Annamarie Phelps, believed these efforts needed to be global to be effective: “if we start to close it down country by country, we’re just pushing people to another jurisdiction; if we act globally, we can push it out to other sports”, she argued.

The critical importance of horse welfare, and the general public’s attitude thereto, was underlined. Louis Romanet, Chair of the IFHA, said: “This is a turning point for our industry—much good has already been done, but there is more to do and dire consequences unless this happens.”

As an indicator of what has already been done, it is noticeable how, in recent years, a much higher proportion of the changes introduced to the IFHA’s International Agreement on Breeding, Racing and Wagering have been horse welfare focussed. For example, this year saw the banning of bloodletting and chemical castration practices—hot on the heels of last year’s outlawing of blistering and firing. Spurs have been banned this year, and it has become mandatory to use the padded whip not only in races but also during training.

For those outside the racing bubble, there would seem to be three core concerns: racing-related fatalities, use of the whip and aftercare. Much space was given over at the conference to the last of these, including a special session organised by the International Forum for the Aftercare of Racehorses, and in this area great strides have certainly been made in several countries. But presentations from Australia demonstrated just how necessary such efforts are. Work on a number of fronts in the interest of the welfare of thoroughbreds has vastly been ramped up in the wake of a number of body-blow welfare scandals, none more powerful than the sickening image of horses being violently maltreated in an abattoir. No longer will the public accept that racing’s responsibility ends when the horse leaves training. Even if it is many years and several changes of ownership after it retires from racing, if it should meet a gruesome end, the world will still point an accusatory finger at us. In the public’s eye, once a racehorse, always a racehorse. It was a fitting coincidence that, just as these presentations were being made in South Africa, across the world, Britain’s Horse Welfare Board was unveiling its major review of horse welfare—a key message that there must be whole-of-life scrutiny.

There is one very troubling aspect of all of this. Having been identified as necessary for racing’s very survival, any of these tasks—exploiting new technology, tackling illegal betting or establishing systems to trace thoroughbreds from cradle to grave—will be costly and resource-hungry to put into effect. The disparity in resources and influence of racing authorities is enormous. At one end of the spectrum, the size and national significance of the Hong Kong Jockey Club is hard to grasp: it employs over 20,000 people and last year paid €3.4bn in taxes and lottery and charitable contributions. In Victoria, and other Australian states, there is a racing minister. New Zealand has been able to boast such a post since 1990, and the current incumbent is also its deputy prime minister, no less.

At the other end, many racing authorities have but one track in their jurisdiction, exist through voluntary labour and are, unsurprisingly, not even on their government’s radar.

It would seem inevitable, without specific countermeasures, that the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ will only widen with the risk of smaller racing nations going under. It is surely desirable for our sport as a whole globally that racing exists and thrives in as many parts of the world as possible. Ensuring this is going to take much thought, will and effort.

STEWARDING FROM A REMOTE ‘BUNKER’

An oft-discussed topic in Europe over recent years is what might best be termed ‘remote stewarding’: where stewards officiate on distant race-meetings from a central location with the aid of audio and visual communications links. But it is outside our continent where you will find the pioneers of this concept. At Turffontein racecourse, Johannesburg, within the National Horseracing Authority of Southern Africa’s (NHRA’s) Headquarters, is a room from which ‘stipes’ have for some time now been linking with other racecourses across the country and sharing the stewarding duties.

South Africa has no volunteer stewards—all are salaried, stipendiary stewards and referred to universally as ‘stipes’.

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD —

WHY NOT SUBSCRIBE?

DON'T MISS OUT AND SUBSCRIBE TO RECEIVE THE NEXT FOUR ISSUES!

EMHF - Might technological advance lead to greater international co-operation in racing?

By Dr. Paull Khan

The Asian Racing Conference (ARC) was first staged 58 years ago and attracted less than 70 delegates. These days, it is held biennially, and the 37th ARC returned to Seoul this year – the third time it has been Korean-hosted.

The Racing

Prior to the conference, delegates had the chance to attend Korean Derby Day at Seoul Racecourse Park. Prize money for the 11-race card averaged over €100,000 per race, with the Derby itself – won by 2/1 favourite Ecton Blade, a son of imported Kentucky-bred stallion Ecton Park – worth €640,000.

The grandstands at Seoul are enormous structures, stretching far along the finishing straight and reminiscent of those at Tokyo racecourse. For many of the 80,000 racegoers who can be accommodated, there is the option of an individually numbered seat, not with any vantage point affording a view of the track, but rather deep in the bowels of one or another of five identical and cavernous floors. Each of these floors was packed this Derby Day with studious race fans, mostly deeply absorbed in their form guides, checking betting monitors, and scribbling notes, doubtless plotting betting combinations of fiendish complexity. The bias towards exotic bets is extreme in Korea, with just one percent of the handle directed at win bets.

By the time of each race, the crowds migrated to the viewing areas of the stands, looking out at the biggest big-screen in the racing world – which, despite its 150m width, is every bit as picture-crisp as one would expect from Korean technology.

Racing is an immensely popular spectator sport in the country. Annual attendances of 15 million from a population of just 50 million put European countries to shame. (For example, in Britain, where racing is the second most popular spectator sport, the 65 million population only make 6 million racecourse visits, and even on the island of Ireland, the ratio is not as impressive as in Korea: 1.3 million turnstile clicks from a population of 6.6 million). One might imagine that this results from a monopoly that racing enjoys when it comes to the gambling options available to Korean citizens. To some extent, this is true: there is but one casino in the whole of the country which Koreans may enter, and there is no domestic online betting offering. But betting – albeit to limited stakes – is allowed on a variety of other sports, a curious selection, including cycling and ssirum (Korea’s answer to sumo wrestling). And illegal online betting is widespread.

So the numbers can be seen as a great advertisement for the sport. And the crowds were fully engaged in the day’s activities: noisy and every bit as animated as one would find at Ascot or Flemington. But there is one striking feature of the scene at Seoul racecourse that sets it apart from virtually every other, outside the Middle East. It slowly dawns on one that these tens of thousands of committed racegoers are enjoying their long day’s racing…..with not an alcoholic outlet in sight! Proof that racing can thrive without an alcoholic crutch: further evidence of just how our sport, in all its diversity around the world, maintains its ability to surprise us and challenge our stereotypes.

The Conference

Those whose business is horseracing descended on Korea from Asia, Europe, and beyond. While the total of 600 or so delegates was some way short of the record numbers attracted to Hong Kong four years ago (tensions in Korea were particularly high at the time people were asked to commit to paying their USD $1,300 attendance fees, which could not have helped), to my mind, this ARC scaled new heights, in terms of the interest and relevance of the topics covered and the professionalism of the presenters.

Sweeping a bright but focussed spotlight across a broad range of issues of real moment to our sport worldwide, it illuminated such things as the frightening increase in illegal betting, the (to many) puzzling speed of growth of eSports, and the growing menace of gene doping.

The standout ‘takeaway’ from the conference for me was a talk on broadcasting technology trends by Hong Kong Jockey Club senior consultant Oonagh Chan. While this fell within a session entitled “Reaching and Expanding Racing’s Fan Base” and focussed on technology advances in areas such as picture resolution and clarity, and how 360° video might attract new followers of horseracing, I was left pondering how dramatically they might also have an impact on stewards’ rooms around the world...

TO READ MORE --

BUY THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DOWNLOAD -

Why not subscribe?

Don't miss out and subscribe to receive the next four issues!

The Asian Racing Conference – from a trainer’s perspective

Attending industry conferences and seminars, especially those staged overseas, as a media reporter can be hard work – honestly! – but when you come across speakers at the top of their game, who can put over concise points in layman’s language, the tedium of long days, and sometimes even longer nights, wafts away on a breeze of simple understanding.

Howard Wright(19 May 2007 - Issue Number: 3)

By Howard Wright

Attending industry conferences and seminars, especially those staged overseas, as a media reporter can be hard work – honestly! – but when you come across speakers at the top of their game, who can put over concise points in layman’s language, the tedium of long days, and sometimes even longer nights, wafts away on a breeze of simple understanding.

Derrmot Weld was invited to address the Asian Racing Conference, held in Dubai in January, in order to bring a horseman’s perspective to the session headed ‘Global series – what have we learnt and where to now?’ In ten minutes, he did far more than that. He gave an audience of 400-plus delegates – only a single handful who were or had been trainers - a master class in travelling horses around the world, and how to be successful along the way.

No better presenter could have been found. From his base at the heart of Irish racing on The Curragh, Weld has created a unique record. He is the first overseas trainer to have annexed two Melbourne Cups, which alone would make the description fit, but he is also the only European trainer to have logged a winning run in a leg of the US Triple Crown.

What lies behind the success of this thoughtful, serious man, whose few words make more sense than some who have written whole chapters on their specialist subject? There is no single factor, he said. Rather there are nine aspects that he considers when assessing whether, and how, to travel a horse abroad. They are:

* Horse – “He has to have the ability to compete at the top level; he must be adaptable to ground and have the right temperament, and he has to be sound. It’s no good if you take an unsound horse, hoping it comes right on the day. In my experience, it rarely does.”

*Jockey – “Bring your own if he’s top class, or get the best locally.”

*Food – “Bring your own if at all possible.”

*Water – “Dehydration is the single biggest negative factor in travelling. Make sure you get it right.”

*Staff – “You need trained, experienced travellers, good work riders, and staff with the confidence and knowledge to report to you accurately.”

*Farrier – “Very important. Around the world there are some good farriers, but one false move can undo everything.”

*Veterinarian – “This is where dehydration will be reported, and he will watch all the tests and look at the blood picture. Make a mistake, and you pay for it.”

*Medication – “I agree with strict rules, but it’s important for the trainer to be aware of the rules from country to country, even from state to state in the US.”

*Quarantine – “Dubai has an excellent facility and is more straightforward than most. Australia has improved, but effectively it still takes nearly a month and could be brought forward. The US is a worry, and facilities at many tracks need to be improved.”

There, in handy-sized bites, is the check-list of a qualified equine vet who has climbed to top of the trainers’ ladder. There was, however, a bonus to the presentation, a bone of contention dug up when Weld was asked to nominate the single biggest improvement that would foster greater international competition.

“We’ve got to standardise the quarantine rules, which differ between Europe, the US, Asia and Australia,” he said. “With modern technology, it can be done, because blood testing for infectious diseases is far more efficient than in the past.”

In a moment, the theme was set, at least from the perspective of the go-ahead trainer with aspirations on the world stage.

The conference wended its fascinating way, discussing a myriad of topics of general concern to racing and betting administrators, from co-mingling bets in overseas pools and designing new racecourses, to standardising rules on stewarding and identifying the main threats to the success of horseracing in the future.

Virtually all impinged on the business of training to some degree, but none seemed to have the immediate significance of the quarantine issue, which came up again, and again.

Adrian Beaumont, director of racecourse services for the Newmarket-based International Racing Bureau, named “a shortening of the quarantine period for racing in Australia” among his three wishes to make life easier for horsemen tackling the global calendar.