Stem Cell Therapy - the improved diagnostics available to treat lameness

/Article by Jackie Zions (interviewing Dr. Koenig)

Prevention is the ideal when it comes to lameness, but practically everyone who has owned horses has dealt with a lay-up due to an unforeseen injury at some point. The following article will provide tools to sharpen your eye for detecting lameness, review prevention tips and discuss the importance of early intervention. It will also begin with a glimpse into current research endeavouring to heal tendon injuries faster, which has obvious horse welfare benefits and supports horse owners eager to return to their training programs. Dr. Judith Koenig of Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) spends half of her time as a surgeon and teacher with a strong interest in equine sports medicine and rehabilitation, and the other half as a researcher at the OVC.

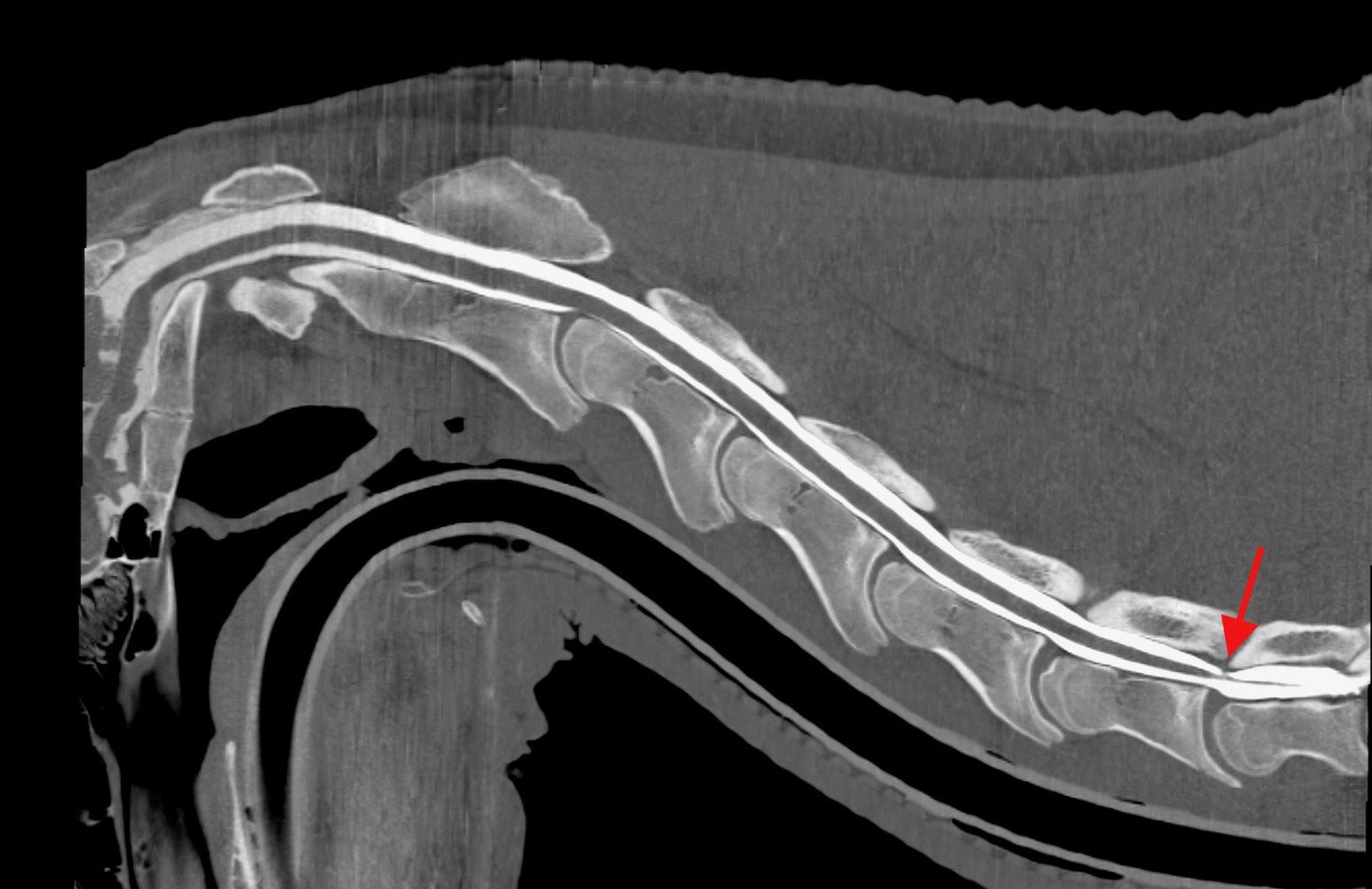

Lameness is a huge focus for Koenig, whose main interest is in tissue healing. “I think over the past 20 or 30 years we have become very, very good at diagnosing the cause of lameness,” says Koenig. “In the past, we had only radiographs and ultrasound as a diagnostic tool, but by now most referral centres also have MRI available; and that allows us to diagnose joint disease or tendon disease even more. We are much better now [at] finding causes that previously may have been missed with ultrasound.”

Improvements in diagnostics have resulted in increased ability to target treatment plans. With all the different biologics on the market today, Koenig sees a shift in the management of joint disease with more people getting away from steroids as a treatment.

The following list is excerpted from Equine Guelph’s short course on lameness offered on TheHorsePortal.ca. It outlines the different diagnostics available:

When asked for the latest news on research she has been involved in, Koenig proclaims, “I'm most excited about the fact that horses are responding well to stem cell treatment—better than I have seen any response to any other drug we have tried so far!”

Koenig has investigated the use of many different modalities to see if they accelerate tissue healing and has studied which cellular pathways are affected. Two recent collaborative studies have produced very exciting findings, revealing future promise for treating equine osteoarthritis with stem cell therapy.

In a safety study, Koenig and her team at the Ontario Veterinary College have shown equine pooled cryopreserved umbilical cord blood, (eCB) MSC, to be safe and effective in treatment of osteoarthritis.

“These cells are the ones harvested from umbilical cord blood at the time of foaling and then that blood is taken to the lab and the stem cells are isolated out of it,” explains Koenig. The stem cells are then put through a variety of tests to make sure they are free of infectious diseases. Once given a clean bill of health, they are expanded and frozen.

The stem cells harvested from multiple donors of equine umbilical cord blood [eCB, (kindly provided by eQcell), MSC] were compared to saline injections in research horses. “This type of cells is much more practical if you have a cell bank,” says Koenig. “You can treat more horses with it, and it’s off the shelf.” There were no systemic reactions in the safety study. Research has also shown no different reactions from sourcing from one donor or multiple donors.

In the second study, 10 million stem cells per vial were frozen for use in healing OA from fetlock chips in horses that were previously conditioned to be fit. After the fetlock chip was created, exercise commenced for six more weeks, and then osteoarthritis was evaluated by MRI for a baseline. Half the horses were treated with the pooled MSC stem cells, and the control group received saline before another month of exercise. Then MRI and lameness exams were repeated, and arthroscopy was repeated to score the cartilage and remove the chip.

Lameness was decreased and cartilage scores were improved in the group that received stem cell therapy at the time of the second look with arthroscopy.

Many diagnostics were utilised during this study. MRIs, X-rays, ultrasounds and weekly lameness evaluations all revealed signs of osteoarthritis in fetlock joints improved in the group treated with (eCB) MSCs. After six weeks of treatment, the arthroscopic score was significantly lower (better cartilage) in the MSC group compared to the control group.

“Using the MRI, we can also see a difference that the horses treated with stem cells had less progression of osteoarthritis, which I think is awesome,” says Koenig. “They were less lame when exercised after the stem cell therapy than the horses that received saline.”

This research group also just completed a clinical trial in client-owned horses diagnosed with fetlock injuries with mild to moderate osteoarthritis changes. The horses were given either 10 million or 20 million stem cells and rechecked three weeks and six weeks after the treatment. Upon re-evaluation, the grade of lameness improved in all the horses by at least one. Only two horses presented a mild transient reaction, which dissipated after 48 hours without any need for antibiotics. The horse’s joints looked normal, with any filling in the joint reduced.

There was no difference in the 18 horses, with nine given 10 million stem cells and the other nine 20 million stem cells; so in the next clinical trial, 10 million stem cells will be used.

The research team is very happy with the results of this first-of-its-kind trial, proving that umbilical cord blood stem cells stopped the progression of osteoarthritis and that the cartilage looked better in the horses that received treatment. The future of stem cell therapy is quite promising!

Rehabilitation

Research has shown adhering to a veterinary-prescribed rehabilitation protocol results in a far better outcome than paddock turn out alone. It is beneficial for tendon healing to have a certain amount of controlled stimulation. “These horses have a much better outcome than the horses that are treated with just being turned out in a paddock for half a year,” emphasises Koenig. “They do much better if they follow an exercise program. Of course, it is important not to overdo it.”

For example, Koenig cautions against skipping hand-walking if it has been advised. It can be so integral to stimulating healing, as proven in recent clinical trials. “The people that followed the rehab instructions together with the stem cell treatment in our last study—those horses all returned to racing,” said Koenig.

“It is super important to follow the rehab instructions when it comes to how long to rest and not to start back too early.”

Another concern when rehabilitating an injured horse would be administering any home remedies that you haven't discussed with your veterinarian. Examples included blistering an area that is actively healing or applying shockwave to mask pain and then commence exercise.

Prevention and Training Tips

While stating there are many methods and opinions when it comes to training horses, Koenig offered a few common subjects backed by research. The first being the importance of daily turnout for young developing horses.

Turnout and exercise

Many studies have looked at the quality of cartilage in young horses with ample access to turn out versus those without. It has been determined that young horses that lack exercise and are kept in a stall have very poor quality cartilage.

Horses that are started early with light exercise (like trotting short distances and a bit of hill work) and that have access to daily paddock turnout, had much better quality of cartilage. Koenig cited research from Dr. Pieter Brama and similar research groups.

Another study shows that muscle and tendon development depend greatly on low grade exercise in young horses. Evaluations at 18 months of age found that the group that had paddock turnout and a little bit of exercise such as running up and down hills had better quality cartilage, tendon and muscle.

Koenig provides a human comparison, with the example of people that recover quicker from injury when they have been active as teenagers and undergone some beneficial conditioning. The inference can be made that horses developing cardiovascular fitness at a young age stand to benefit their whole lives from the early muscle development.

Koenig says it takes six weeks to regain muscle strength after injury, but anywhere from four to six months for bone to develop strength. It needs to be repeatedly loaded, but one should not do anything too crazy! Gradual introduction of exercise is the rule of thumb.

Rest and Recovery

“Ideally they have two rest days a week, but one rest day a week as a minimum,” says Koenig. “I cannot stress enough the importance of periods of rest after strenuous work, and if you notice any type of filling in the joints after workout, you should definitely rest the horse for a couple of days and apply ice to any structures that are filled or tendons or muscles that are hard.”

Not purporting to be a trainer, Koenig does state that two speed workouts a week would be a maximum to allow for proper recovery. You will also want to make sure they have enough access to salt/electrolytes and water after training.

During a post-Covid interview, Koenig imparted important advice for bringing horses back into work methodically when they have experienced significant time off.

“You need to allow at least a six-week training period for the athletes to be slowly brought back and build up muscle mass and cardiovascular fitness,” says Koenig. “Both stamina and muscle mass need to be retrained.”

Watch video: “Lameness research - What precautions do you take to start training after time off?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNHba_nXi2k

The importance was stressed to check the horse’s legs for heat and swelling before and after every ride and to always pick out the feet. A good period of walking is required in the warmup and cool down; and riders need to pay attention to soundness in the walk before commencing their work out.

Footing and Cross Training

With a European background, Koenig is no stranger to the varying track surfaces used in their training programs. Statistics suggest fewer injuries with horses that are running on turf.

Working on hard track surfaces has been known to increase the chance of injury, but delving into footing is beyond the scope of this article.

“Cross training is very important,” says Koenig. “It is critical for the mental and proper musculoskeletal development of the athlete to have for every three training days a day off, or even better provide cross-training like trail riding on these days."

Cross-training can mitigate overtraining, giving the body and mind a mental break from intense training. It can increase motivation and also musculoskeletal strength. Varied loading from training on different terrain at different gaits means bone and muscle will be loaded differently, therefore reducing repetitive strain that can cause lameness.

Hoof care

Whether it is a horse coming back from injury, or a young horse beginning training, a proficient farrier is indispensable to ensure proper balance when trimming the feet. In fact, balancing the hoof right from the start is paramount because if they have some conformational abnormalities, like abnormal angles, they tend to load one side of their joint or bone more than the other. This predisposes them to potentially losing bone elasticity on the side they load more because the bone will lay down more calcium on that side, trying to make it stronger; but it actually makes the bone plate under the cartilage brittle.

Koenig could not overstate the importance of excellent hoof care when it comes to joint health and advises strongly to invest in a good blacksmith. Many conformational issues can be averted by having a skilled farrier right from the time they are foals. Of course, it would be remiss not to mention that prevention truly begins with nutrition. “It starts with how the broodmare is fed to prevent development of orthopaedic disease,” says Koenig. Consulting with an equine nutritionist certainly plays a role in healthy bone development and keeping horses sound.