The importance of good hoof balance to improve performance

/The equine foot is a unique structure and a remarkable feat of natural engineering that follows the laws of biomechanics in order to efficiently and effectively disperse concussional forces that occur during the locomotion of the horse. Hoof balance has been a term used by veterinarians and farriers to describe the ideal conformation, size and shape of the hoof relative to the limb.

Before horses were domesticated, they evolved and adapted to survive without any human intervention. With respect to their hoof maintenance, excess hoof growth was worn away due to the varied terrain in their habitat. No trimming and shoeing were required as the hoof was kept at a healthy length.

With the domestication of the horse and our continued breeding to achieve satisfactory performance and temperament, the need to manage the horse’s hoof became essential in order to ensure soundness and performance. The horse’s foot has evolved to ensure the health and soundness of the horse; therefore, every structure of the foot has an essential role and purpose. A strong working knowledge of the biology and biomechanics of the horse’s foot is essential for the veterinarian and farrier to implement appropriate farriery. It was soon concluded that a well-balanced foot, which entails symmetry in shape and size, is essential to achieve a sound and healthy horse.

Anatomy and function of the foot

The equine foot is extremely complex and consists of many parts that work simultaneously allowing the horse to be sound and cope with the various terrains and disciplines. Considering the size and weight of the horse relative to the size of the hoof, it is remarkable what nature has engineered. Being a small structure, the hooves can support so much weight and endure a great deal of force. At walk, the horse places ½ of its body weight through its limbs and 2 ½ its weight when galloping. The structure of the equine foot provides protection, weight bearing, traction, and concussional absorption. Well-balanced feet efficiently and effectively use all of the structures of the foot to disperse the forces of locomotion. In order to keep those feet healthy for a sound horse, understanding the anatomy is paramount.

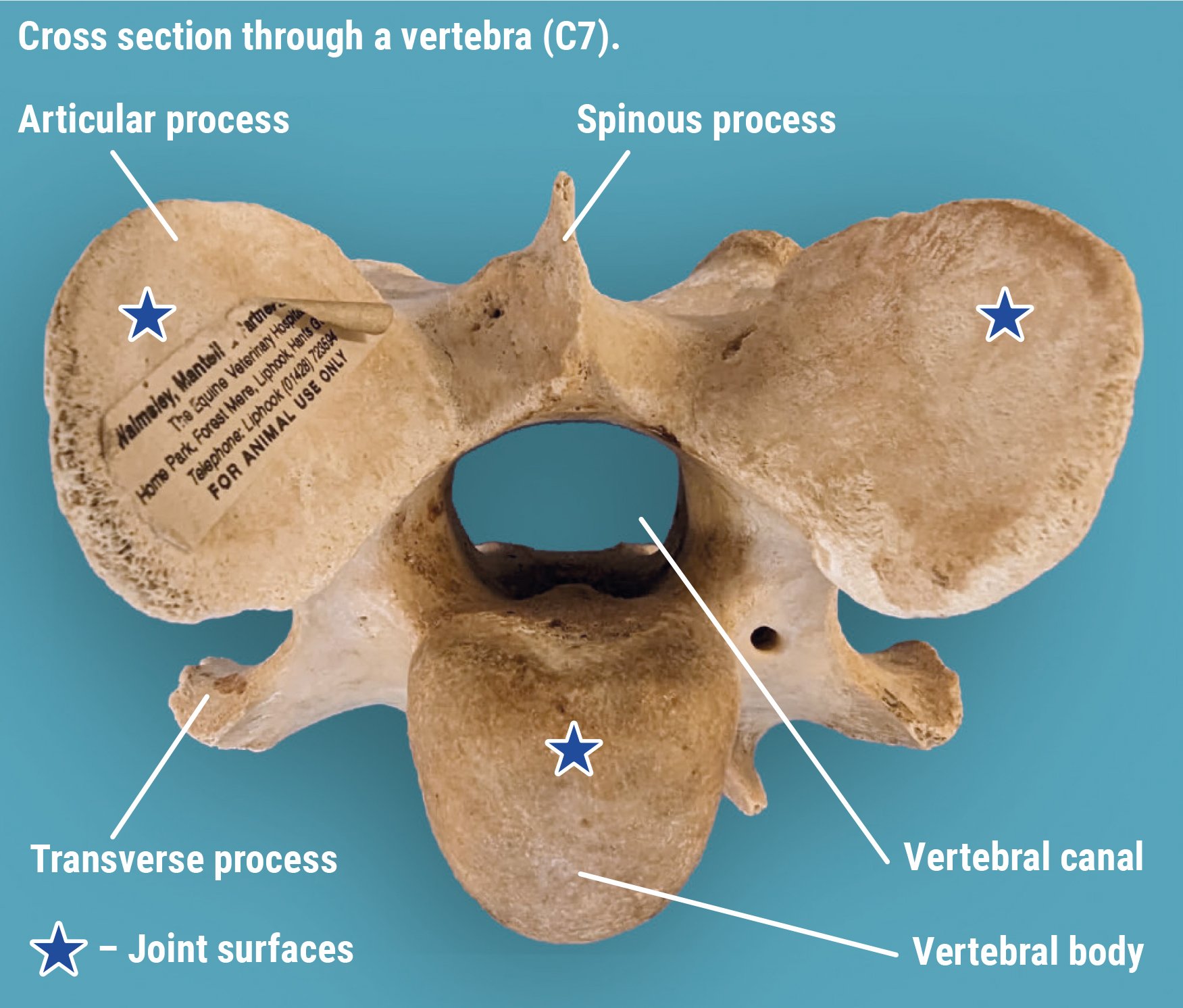

The foot consists of the distal end of the second phalanx (short pastern), the distal phalanx (pedal bone, coffin bone) and the navicular bone. The distal interphalangeal joint (coffin joint) is found between the pedal and short pastern bone and includes the navicular bone with the deep digital flexor tendon supporting this joint. This coffin joint is the centre of articulation over which the entire limb rotates. The navicular bone and bursa sits behind the coffin bone and is stabilised by multiple small ligaments. The navicular bone allows the deep digital flexor tendon to run smoothly and change direction in order to insert into the coffin bone. The navicular bursa is a fluid-filled sac that sits between the navicular bone and the deep digital flexor tendon.

The hoof complex can be divided into the epidermal weight-bearing structures that include the sole, frog, heel, bulbs, bars, and hoof wall and the anti-concussive structures that include the digital cushion, lamina, deep digital flexor tendons, and ungual (lateral) cartilage. The hoof wall encloses the dermal structures with its thickest part at the toe that decreases in thickness as it approaches the heel. The hoof wall is composed of viscoelastic material that allows it to deform and return its shape in order to absorb concussional forces of movement. There is enough deformation to diminish the force from the impact and load of the foot while preventing any damage to the internal structures of the foot and limb. As load is placed on the foot, there is deformation that consists of:

Expansion of the heels

Sinking of the heels

Inward movement of the dorsal wall

Biaxial compression of the dorsal wall

Depression of the coronary band

Flattening of the sole

The hoof wall, bars and their association with the sole form the heel base with the purposes of providing traction, bearing the horse’s weight while allowing the stability and flexibility for the expansion of the hoof capsule that dissipates concussional forces on foot fall. The sole is a highly keratinised structure like the hoof wall but made up of nearly 33% water so it is softer than the hoof wall and should be concave to allow the flattening of the sole on load application. The frog and heel bulbs serve a variety of special functions ranging from traction, protection, coordination, proprioception, shock absorption and the circulation of blood.

When the foot lands on the ground, the elastic, blood-filled frog helps disperse some of the force away from the bones and joints, thus, acting as a shock absorber. The venous plexus above the frog is involved in pumping blood from the foot back to the heart when the foot is loaded. In addition, there is shielding of the deep digital flexor tendon and the sensitive digital cushion (soft tissue beneath the sole that separates the frog and the heel bulb from the underlying tendons and bones). Like the heel bulbs, the frog has many sensory nerve endings allowing the horse to be aware of where his body and feet are and allows the horse to alter landing according to the condition of the ground (proprioception and coordination).

The soft tissue structures comprise and form the palmar/plantar aspect of the foot. The digital cushion lies between the lateral cartilages and above the frog and bars of the horse’s hoof. This structure is composed of collagen, fibrocartilage, adipose tissue and elastic fibre bundles. The digital cushion plays a role in shock absorption when the foot is loaded as well as a blood pumping mechanism. Interestingly, it has been found that the digital cushion composition varies across and within breeds. It is thought the variation of the composition of the digital cushion is partially dictated by a genetic predisposition. In addition, the composition of the digital cushion changes with age. As the horse ages the composition alters from elastic, fat and isolated collagen bundles to a stronger fibrocartilage. Finally, the digital cushion and connective tissue within the foot have the ability to adapt to various external stimuli such as ground contact or body weight. The lateral cartilage is a flexible sheet of fibrocartilage that suspends the pedal bone as well as acting as a spring to store and release energy. The lamina is a highly critical structure for hoof health. The lamina lies between the hoof wall and the coffin bone. There are two types of lamina known as the sensitive (dermal) lamina and insensitive (epidermal) lamina. The insensitive lamina coming in from the hoof wall connects to the sensitive lamina layer that is attached to the coffin bone and these two types of lamina interdigitate with each other to form a bond.

Hoof and Musculoskeletal System

The hoof and the musculoskeletal system are closely linked and this is particularly observed in the posture of the horse when resting or moving. Hoof shape and size and whether they are balanced directly affects the posture of the horse. Ultimately, this posture will also affect the loads placed on the skeletal system, which affects bone remodelling. With an imbalance, bone pathologies of the limbs, spine and pelvis may occur such as osteoarthritis. In addition, foot imbalances result in postural changes that lead to stress to the soft tissue structures that may lead to muscle injuries and/or tendon/ligament injuries.

Conformation and hoof balance

The terms balance and conformation are used frequently and used to describe the shape and size of the limb as a whole as well as the individual components of the limb and the spatial relations between them. Balance is the term often used to describe the foot and can be viewed as a subset of conformation.

Conformation should be considered when describing the static relations within the limb and excludes the foot. Balance should be considered when describing the dynamic and static relationship between the horse’s foot and the ground and limb as well as within the hoof itself.

These distinctions between conformation and balance are important to assess lameness and performance of the horse. Additionally, this allows the veterinarian and farrier to find optimal balance for any given conformation.

The term hoof balance does lack an intrinsic definition. The use of certain principles in order to define hoof balance, which in turn can be extended to have consistent evaluation of hoof balance as well as guide the trimming and shoeing regimens for each individual horse. In addition, these principles can be used to improve hoof capsule distortion, modify hoof conformation and alter landing patterns of the foot. These principles are:

Evaluate hoof-pastern axis

Evaluate centre of articulation

The need for the heels to extend to the base of the frog

Assessing the horse’s foot balance by observing both static (geometric) balance and dynamic balance is vital. Static balance is the balance of the foot as it sits on a level, clean, hard surface. Dynamic balance is assessing the foot balance as the foot is in motion. However, horses normally do not resemble the textbook examples of perfect conformation, which creates challenges for the farriers and veterinary surgeons. The veterinarian should instigate further evaluation of the foot balance and any other ailments, in order to provide information that can be used by the farrier and veterinarian in formulating a strategy to help with the horse’s foot balance. With the farrier and veterinarian working cooperatively, the assessment of the hoof balance and shoeing of the foot should deliver a harmonious relationship between the horse’s limb, the hoof and the shoe.

Dynamic Balance

The horse should be assessed in motion as one can observe the foot landing and placement. A balanced foot when in motion should land symmetrically and flat when moving on a flat surface. When viewed from the side, the heels and toe should land concurrently (flat foot landing) or even a slight heel first landing. It is undesirable to have the toe landing first and often suggests pain localised to the heel region of the foot. When observing the horse from the front and behind, both heel bulbs should land at the same time. Sometimes, horses will land first slightly on the outside or lateral heel bulb of the foot but rarely will a horse land normally on the medial (inside) of the foot. If the horse has no conformational abnormalities or pathologies the static balance will achieve the dynamic balance.

Static Balance

Hoof –pastern axis (HPA)

The hoof pastern axis (HPA) is a helpful guideline in assessing foot balance. With the horse standing square on a hard, level surface, a line drawn through the pastern and hoof should be parallel to the dorsal hoof wall and should be straight (unbroken). The heel and toe angle should be within 5 degrees of each other. An underrun heel has been defined as the angle of the heel being 5 degrees less than the toe angle. The heel wall length should be roughly 1/3 of the dorsal wall. In addition, the cannon (metacarpus/metatarsus) bone is perpendicular to the ground and when observed from the lateral side, the HPA should be a straight line. When assessing the foot from the side, the dorsal hoof wall should be aligned with the pastern. The optimal angle of the dorsal hoof wall is often cited as being 50-54°. The length of the dorsal hoof wall is variable but guidelines have been suggested according to the weight of the horse.

It is not uncommon that the hind feet are more upright compared to the fore feet at approximately 5 degrees. A broken hoof-pastern axis is the most common hoof imbalance. There are two presentations of a broken HPA known as a broken-back HPA and a broken-forward HPA. These changes in HPA are often associated with two common hoof capsule distortions that include low or underrun heels and the upright or clubfoot, respectively.

A broken-back hoof-pastern axis occurs when the angle of the dorsal hoof wall is lower than the angle of the dorsal pastern. This presentation is commonly caused by low or underrun heel foot conformation accompanied with a long toe. This foot imbalance is common and often thought to be normal with one study finding it present in 52% of the horse population. With a low hoof angle, there is an extension of the coffin and pastern joints resulting in a delayed breakover and the heels bearing more of the horse's weight, which ultimately leads to excess stress in the deep digital flexor tendon as well as the structures around the navicular region including the bone itself.

This leads to caudal foot pain so the horse lands toe first causing subsolar bruising. In addition, this foot imbalance can contribute to chronic heel pain (bruising), quarter and heel cracks, coffin joint inflammation and caudal foot pain (navicular syndrome). The cause of underrun heels is multifactorial with a possibility of a genetic predisposition where they may have or may acquire the same foot conformation as the parents. There are also environmental factors such as excessive dryness or moisture that may lead to the imbalance.

A broken-forward hoof-pastern axis occurs at a high hoof angle with the angle of the dorsal hoof wall being higher than the dorsal pastern angle. One can distinguish between a broken-forward HPA and a clubfoot with the use of radiographs. With this foot imbalance, the heels grow long, which causes the bypassing of the soft tissue structures in the palmar/plantar area of the foot and leads to greater concussional forces on the bone. This foot imbalance promotes the landing of the toe first and leads to coffin joint flexion as well as increases heel pressure. The resulting pathologies that may occur are solar bruising, increased strain of the suspensory ligaments near the navicular bone and coffin joint inflammation.

Center of articulation

When the limb is viewed laterally, the centre of articulation is determined with a vertical line drawn from the centre of the lateral condyle of the short pastern to the ground. This line should bisect the middle of the foot at the widest part of the foot and demonstrates the centre of articulation of the coffin joint. The widest part of the foot (colloquially known as “Ducketts Bridge”) is the one point on the sole that remains constant despite the shape and size of the foot. The distance and force on either side of the line drawn through the widest part of the foot should be equal, which provides biomechanical efficiency.

Heels extending to the base of the frog

With respect to hoof balance, another component of the foot to assess is that the heels of the hoof capsule extend to the base of the frog. The hoof capsule consists of the pedal bone occupying two-thirds of the space and one-third of the space is soft tissue structures. This area is involved in dissipating the concussional and loading forces and in order to ensure biomechanical efficiency both the bone and soft-tissue structures need to be enclosed in the hoof capsule in the same plane.

To achieve this goal the hoof wall at the heels must extend to the base of the frog. If the heels are allowed to migrate toward the centre of the foot or left too long then the function of the soft tissue structures have been transferred to the bones, which is undesirable. If there is a limited amount to trim in the heels or a small amount of soft tissue mass is present in the palmar foot then some form of farriery is needed to extend the base of the frog (such as an extension of the branch of a shoe).

Medio-lateral or latero-medial balance

The medio-lateral balance is assessed by viewing the foot from the front and behind as well as from above with the foot raised. To determine if the foot has medio-lateral balance, the hoof should be bisected or a line is drawn down the middle of the pastern down to the point of the toe.

You should be able to visualise the same amount of hoof on both the left and right of that midline. In addition, one should observe the same angle to the side of the hoof wall. It is important to pick up the foot and look at the bottom. Draw a line from the middle quarter (widest part of foot) on one side to the other then draw a line from the middle of the toe to the middle sulcus of the frog.

This provides four quadrants with all quadrants being relatively the same in size (Proportions between 40/60 to 60/40 have been described as acceptable for the barefoot and are dependent on the hoof slope). The frog width should be 50-60% of its length with a wide and shallow central sulcus. The frog should be thick enough to be a part of the bearing surface of the foot. The bars should be straight and not fold to the mid frog. The sole should be concave and the intersection point of both lines should be the area of optimal biomechanical efficiency.

The less concavity means the bone is nearer to the ground, thus, bearing greater concussional force. Finally, assess the lateral and medial heel length. Look down at the heel to determine the balance in the length of both heel bulbs. Each heel bulb should be the same size and height. If there are any irregularities with the heel bulbs then sheared heels may result, which is a painful condition. Medio-lateral foot imbalance results in the uneven loading of the foot that leads to an accumulation of damage to the structures of the foot ultimately causing inflammation, pain, injury and lameness. Soles vary in thickness but a uniform sole depth of 15mm is believed to be the minimum necessary for protection.

Dorso-palmar/plantar (front to back – DP) balance

Refers to the overall hoof angle and the alignment of the hoof angle with the pastern angle when the cannon bone is perpendicular to the ground surface. When assessing the foot from the side, the dorsal hoof wall should be aligned with the pastern. The optimal angle of the dorsal hoof wall is often cited as being 50-54°. The length of the dorsal hoof wall is variable but guidelines have been suggested according to the weight of the horse.

The heel and toe angle should be within 5 degrees of each other. An underrun heel has been defined as the angle of the heel being 5 degrees less than the toe angle. The heel wall length should be roughly 1/3 of the dorsal wall.

A line dropped from the first third of the coronet should bisect the base. A vertical line that bisects the 3rd metacarpal bone should intersect the ground at the palmar aspect of the heels.

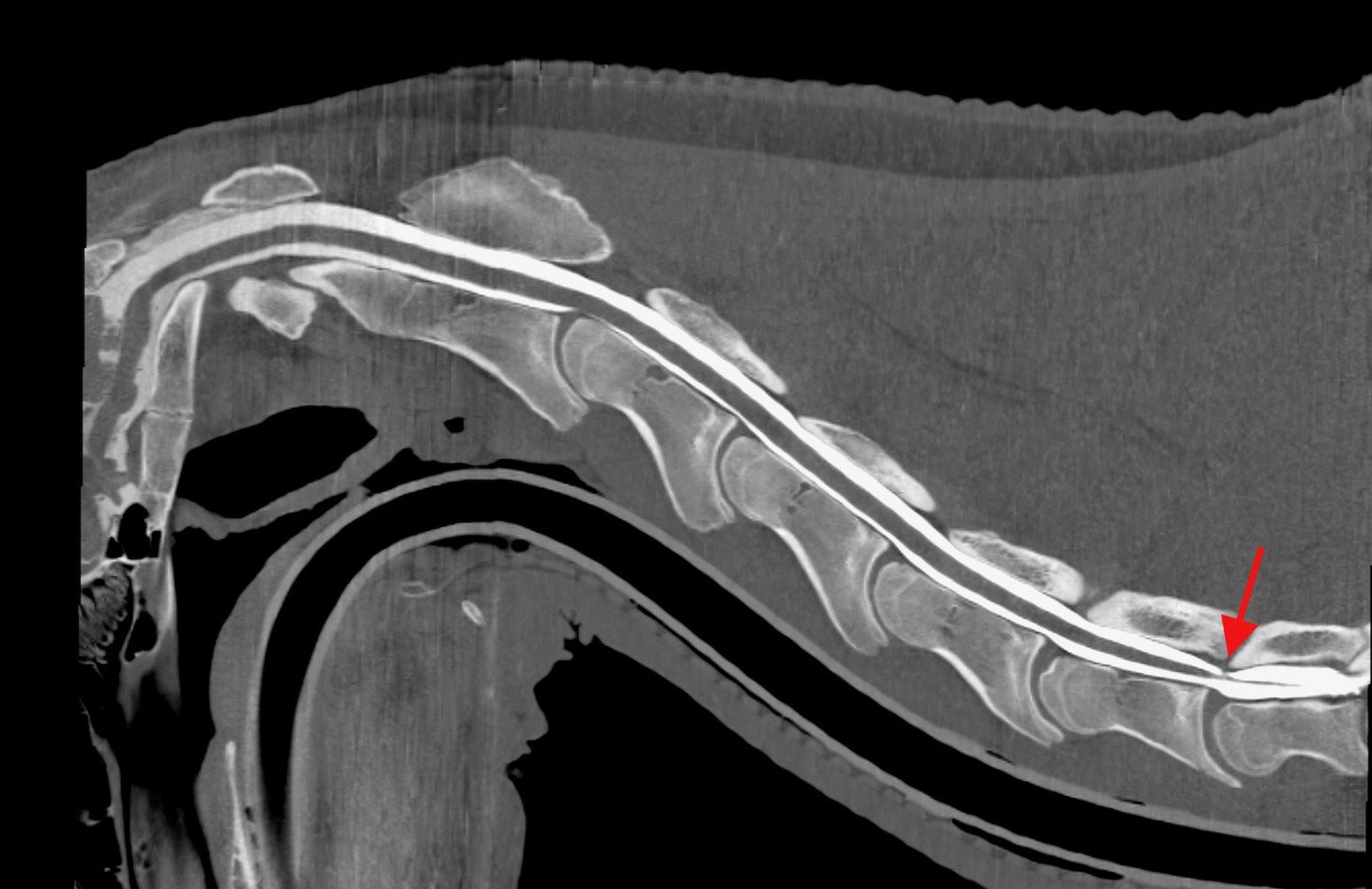

Radiographs

A useful way to assess trimming and foot balance is by having foot x-rays performed. Radiography is the only thorough and conclusive method that allows one to determine if the foot is not balanced and the bony column (HPA) is aligned.

Shoes should be removed and the foot cleaned before radiographs are executed. The horse is often placed on foot blocks to elevate the feet off the ground so that the foot can be centred in the cassette and x-ray beam.

Latero-medial view – The side view of the foot allows one to assess the dorsal and palmar aspects of the pedal bone as well as the navicular bone. The horse should be standing squarely on a flat, level surface. This projection is useful in determining the point of breakover and the hoof pastern axis should be parallel with the hoof wall. The lateral view will demonstrate the length of the toe and the alignment of the dorsal surface of the pedal bone with the hoof wall, which should be parallel. This view also allows one to determine the depth of the sole and inadequate solar depth is usually accompanied with excessive toe length (broken-back HPA). One may observe a clubfoot, broken forward.

One can distinguish between a clubfoot and a broken-forward HPA with radiographs. The broken-forward HPA the hoof angle of the heel is greater than the angle of the dorsal hoof wall. The clubfoot also demonstrates these steep/high hoof angles but additionally the alignment of the coffin, short and long pastern bones are broken forward.

Dorsopalmar/plantar views - this “front to back” view is also performed with the horse standing squarely on 2 positioning blocks. This projection allows the evaluation of medial to lateral balance and conformation of the foot with observation and measurement of the medial and lateral wall length and angle. Horses with satisfactory conformation present with a parallel joint surface of the pedal bone to the ground. The coffin joint should be even across its width. In addition, the lateral and medial coronet and the lateral and medial walls are of equal thickness and the distance from the lateral and medial solar margins to the ground are similar.

With foot imbalance, this author has observed that fore feet may have a higher lateral hoof wall, whereas, the hind feet may have a higher medial hoof wall. It is worth noting that the pelvis, stifle and hocks are adapted to move laterally allowing a slight rotating action as it moves. This action may cause uneven wear or poor trimming and shoeing may cause this limb movement to be out of line.

Trimming

Often, trimming and shoeing are based on empirical experience that includes theoretical assumptions and aesthetic decisions. The goals of trimming and shoeing are to facilitate breakover, ensure solar protection and provide heel support. Trimming is the most important aspect of farriery because it creates the base to which a shoe is fitted. Hoof conformation takes into account the function and shape of the foot in relation to the ground and lower limb both at rest and exercise. Each individual foot should have a conformation that provides protection and strength while maximising biomechanical efficiency often viewed as foot balance.

An important question that initially needs to be addressed is whether the horse requires shoes or not. The answer does depend on what type of work the horse performs, what is the amount of workload, the conformation of the horse (especially the limbs and foot) and are there any previous or current injuries. It must be stressed that the most important aspect, whether the horse is shod or not, is that the trim ensures an appropriately balanced foot for the horse. If there is poor trimming then this may lead to uneven and increased workload on the limb leading to an increased strain of the hoof and soft tissues (i.e. ligaments, tendons) that increase the risk of injury and developing acute and chronic lameness.

The foot can be evaluated, trimmed and/or shod in a consistent, reproducible manner that considers:

Hoof-pastern axis (HPA)

The centre of articulation

Heels extending to the base of the frog

Appropriate trimming and shoeing to ensure the base of the foot is under the lateral cartilage; therefore, maximising the use of the digital cushion, can help in creating a highly effective haemodynamic mechanism. Shoeing must be done that allows full functionality of the foot so that load and concessional forces are dissipated effectively.

To implement appropriate farriery, initially observe the horse standing square on a hard service to confirm that the HPA is parallel. If The HPA is broken forward or backward then these balances should be part of the trimming plan. To determine the location of the centre of rotation, palpate the dorsal and palmar aspect of the short pastern just above the coronary band and a line dropped vertically from the centre of that line should correlate with the widest part of the foot.

Shoeing

When the shoe is placed on the horse, the horse is no longer standing on its feet but on the shoe; therefore, shoeing is an extension of the trim. The shoe must complement the trim and must have the same biomechanical landmarks to ensure good foot balance. It is this author’s view that the shoe should be the lightest and simplest possible. The shoe must be placed central to the widest part of the foot and the distance from the breakover point to the widest part of the foot should be equal to the distance between the widest part of the foot and the heel.

It has been shown that the use of shoes that lift the sole, frog and bars can reduce the efficient workings of the caudal foot and may lead to the prevalence of weak feet. A study by Roepstorff demonstrated there was a reduced expansion and contraction of the shod foot but improved functionality of solar and frog support. With this information, appropriate shoeing should allow increased functionality of the digital cushion, frog and bars of the foot, which improves the morphology and health of the hoof and reduces the risk of exceeding the hoof elasticity.

Disease associated with hoof imbalance

Foot imbalance can lead to multiple ailments and pathologies in the horse. It must be noted that the pathologies that may result are not necessarily exclusive for the foot but may expand to other components to the horse’s musculoskeletal system. In addition, not one but multiple pathologies may result. Diseases that may result from hoof imbalance are:

Conclusion

Foot balance is essential for your horse to lead a healthy and sound life and career. With a strong understanding of the horse anatomy and how foot imbalance can lead to lameness as well as other musculoskeletal ailments, one can work to assess and alter foot balance in order to ensure optimal performance and wellbeing of the horse. It is essential that there is a team approach involving all stakeholders as well as the veterinarian and farrier in order to achieve foot balance. With focus on foot balance, one can make a good horse into a great horse.